ABSTRACT

Salmonella is a foodborne pathogen that poses a significant threat to global public health. It affects several animal species, including horses. Salmonella infections in horses can be either asymptomatic or cause severe clinical illness. Infections caused by Salmonella are presently controlled with antibiotics. Due to the formation of biofilms and the emergence of antimicrobial resistance, the treatment has become more complicated. Our study focused on investigating the prevalence of Salmonella enterica in necropsied horses, assessing the capability for biofilm formation, and motility, determining the phenotypic and genotypic profiles of antibiotic resistance, and detecting virulence genes. A total of 2,182 necropsied horses were tested for the presence of Salmonella. Intestinal samples were enriched in selenite broth and cultured on hektoen and eosin methylene blue agar plates, whereas other samples were directly cultured on aforementioned plates. Confirmation of the serotypes was performed according to the Kauffmann–White–Le Minor Scheme followed by biofilm formation screening using crystal violet assay. The resistance profile of the isolates was determined by broth microdilution assay using the Sensititre️ Vet (Equine EQUIN2F). The genotypic antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and virulence profiles were detected using polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The overall prevalence of Salmonella was 1.19% (26/2182), with 11 different serotypes identified. Salmonella Typhimurium was the most prevalent serotype with 19.2% prevalence. All of the isolates were identified as biofilm producers and motile. Virulence genes related to invasion (invA, hilA, mgtC, and spiA), biofilm formation (csgA and csgB), and motility (filA, motA, flgG, figG, flgH, fimC, fimD, and fimH) of Salmonella were detected among 100% of the isolates. An overall 11.4% of the isolates were identified as multidrug-resistant (MDR), with resistance to gentamicin, amikacin, ampicillin, ceftazidime, ceftiofur, chloramphenicol, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. We found that beta-lactamase-producing genes blaTEM, blaCTXM, and blaSHV2 were identified in 11.5% of the isolates, while only 3.8% carried the blaOXA-9 gene. The presence of MDR pathogenic Salmonella in horses is alarming for human and animal health, especially when they have a high affinity for forming biofilm. Our study found horses as potential sources of pathogenic Salmonella transmission to humans. Thus, it is important to perform continuous monitoring and surveillance studies to track the source of infection and develop preventive measures.

IMPORTANCE

This study focuses on understanding how Salmonella, specifically isolated from horses, can resist antibiotics and cause disease. Salmonella is a well-known foodborne pathogen that can pose risks not only to animals but also to humans. By studying the bacteria from necropsied horses, the research aims to uncover how certain Salmonella strains develop resistance to antibiotics and which genetic factors make them more dangerous. In addition to antibiotic resistance, the research explores the biofilm-forming ability of these strains, which enhances their survival in harsh environments. The study also investigates their motility, a factor that contributes to the spread of infection. The findings can improve treatment strategies for horses and help prevent the transmission of resistant bacteria to other animals as well as humans. Ultimately, the research could contribute to better management of antibiotic resistance in both veterinary and public health contexts, helping to safeguard animal welfare and public health.

KEYWORDS: Salmonella, biofilm , antimicrobial resistance, MDR, resistance genes, horses, motility

INTRODUCTION

Salmonella enterica is a Gram-negative bacterium within the Enterobacteriaceae family and is one of the four primary contributors to diarrheal diseases worldwide (1). It is a prominent foodborne pathogen that can affect a wide range of hosts, including equines, and is also listed as a significant cause of illness and death by the World Health Organization (WHO) (2, 3). To date, more than 2600 Salmonella serotypes have been identified, all of which have the potential to cause cross-infections between animals and humans (3, 4) and most of them have been reported as the cause of significant economic losses globally (5).

Salmonellosis in equines is mainly associated with nosocomial infections along with on-farm contamination (6). Although subclinical infection and shedding of Salmonella are more common in horses, clinical infections can cause enterocolitis with acute severe diarrhea and protein-losing enteropathy (7). It was reported that the prevalence of subclinical Salmonella ranges between 1% and 2% in healthy horses (8–10); however, this number can increase up to 9%–13% in hospitalized horses suffering from colic or gastrointestinal symptoms (11). In addition, a significantly high mortality rate in equine veterinary hospitals (38%–44%) was associated with Salmonella infections (2). The most commonly isolated Salmonella serotypes in horses include S. enterica serovars Typhimurium, Newport, Javiana, Braenderup, Anatum, Infantis, Muenchen, and Mbandaka (5, 12–14). The presence of these human-associated serotypes in horses indicates that equines may act as a potential source of infection for other hosts, including humans (15, 16).

Salmonella transmission in horses primarily occurs via the fecal–oral route, either from contaminated food and environments or direct contact with other infected horses (5). Fecal shedding of Salmonella from horses contaminates the surrounding environment, and its ability to survive in damp environments poses a potential threat to a wide range of hosts, including humans (7, 17–19). The role of horses as working animals, livestock, and pets increases the chance of Salmonella transmission to humans (20–22). According to the CDC, Salmonella infections in humans contribute to around 1.35 million illnesses, 26,500 hospitalizations, and 420 fatalities each year in the US alone (1). Infections in humans cause self-limiting gastroenteritis. However, persistent non-treated infections may lead to both gallbladder and colon cancer (23).

The pathogenicity of Salmonella depends on several virulence factors that can lead to serious infections in the host (5, 24). The pathogenesis of Salmonella begins with the invasion of host intestinal epithelial cells and alteration of the host cellular mechanism (25). In addition, biofilms, the aggregation of bacterial cells surrounded by extracellular polysaccharide matrix, along with flagellar and fimbrial motility, function as critical virulence factors that facilitate the spread of infection between the hosts and their surrounding environment (26). Salmonella can adhere to various abiotic surfaces, such as water or feed buckets in horse stalls, where it forms biofilms that act as potential sources of contamination (7). The extracellular matrix of Salmonella biofilms increases the bacterial resistance to antibiotics, disinfectants, and the host immune system, making decontamination or treatment significantly more challenging (27, 28). On the other hand, swimming and swarming motility have been detected in Salmonella and reported as one of the major virulence factors (29). Motility enhances its ability to colonize, infect, and survive in diverse environments, contributing to the persistence of its pathogenicity (30).

Although most Salmonella infections are self-limiting, severe illness or systemic involvement necessitates antimicrobial therapy (31). The commonly used antibiotics for treating Salmonella infections in horses are ceftiofur, enrofloxacin, and gentamicin (32). However, the emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) Salmonella strains represents a primary factor contributing to the rising frequency of salmonellosis outbreaks (33–35). The resistance of Salmonella to these antibiotics in horses was reported in several studies (32, 36). For example, 10.2% of MDR Salmonella isolates with 20 different resistance patterns were observed among equines in the United States (32). Another study from the Netherlands reported 13% MDR Salmonella from horses where most of them were resistant to tetracycline (53%), ampicillin (34%), trimethoprim/sulfonamide (21%), and gentamicin (6%) (37). The precise time and manner in which MDR Salmonella emerged remain uncertain; however, the non-therapeutic use of antibiotics is considered a prime contributing factor (38). These resistant bacteria have the potential to cause subclinical or clinical infections in equines (39). However, these MDR Salmonella strains can pose a significant contamination risk, and their presence in necropsied horse samples may increase the potential for transmission. It is crucial to evaluate the risk factors and thoroughly characterize these Salmonella strains from necropsied horse samples. The aim of this study is to investigate the occurrence of Salmonella in clinical samples from horses, including a detection of serotype variations, biofilm formation, motility, antibiotic resistance pattern, and genotypic characterization of virulence and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Samples collection, Salmonella detection and confirmation, and serotyping

A total of 2,182 horses were submitted for necropsy to the Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory at the University of Kentucky between January 2022 and December 2023. The majority of the horses exhibited symptoms related to the gastrointestinal tract, with some testing positive for Salmonella before necropsy. Samples were collected from different organs, including the intestine, lung, liver, kidney, colon, and feces of both hospitalized and non-hospitalized horses (Table S1). Following searing the surface of the organs with sterile blades, swab samples were obtained and plated on blood agar (BA) (Hardy Diagnostics, Santa Maria, CA, USA), hektoen (Hardy Diagnostics, Santa Maria, CA, USA), and eosin methylene blue (EMB) (Hardy Diagnostics, Santa Maria, CA, USA) plates. Fecal swabs were enriched in selenite broth, in addition to direct inoculation onto BA, hektoen, and EMB, and incubated at 37°C for 18–24 h. Enriched samples were further subcultured on hektoen and EMB agar plates and incubated at 37°C for 48 h. Black (in hektoen) and white (in EMB) colonies were selected for further studies as described before (40). Briefly, suspected colonies were selected, subcultured, and identified by matrix-assisted laser desorption–ionization time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF) using the direct transfer method and a minimum score of 1.7 for genus identification using the Biotyper software (version 4.0; Bruker Scientific Corp., San Jose, CA, USA). Genomic DNA was extracted from the positive isolates using the boiling method as described before (41), and quality was checked using Thermo Scientific NanoDrop (Thermofisher, Lexington, KY, USA). Pure bacterial colonies were added to 100 µL distilled water, heated at 95°C for 10 min, and then cooled at 4°C for 10 min in the BioRad thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Centrifugation was performed at 14,000 rpm for 10 min. Then, 50 µL supernatants were collected and used as DNA template. To confirm the positive isolates, a PCR targeting the invA gene was performed using oligonucleotide primers listed in Table S2 (42). The amplification was performed in a 12.5 µL reaction volume. Each reaction consisted of 6.25 µL of 2× Green master mix (1 U i-Taq DNA polymerase, 2× PCR buffer, 3 mM MgCl2, and 0.4 mM dNTPs; Promega, Madison, WI, USA), 0.5 µL each of forward and reverse primers (10 µM), 1 µL DNA template, and 4.25 µL of PCR water. PCR was performed using the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min, denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec, annealing at 60°C for 30 sec, extension at 72°C for 30 sec, repeated for 35 cycles, and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. Serotyping was performed in the National Veterinary Services Laboratory (NVSL) following the Kauffmann–White–Le Minor Scheme (43). A conventional agglutination test employing anti-O and anti-H antisera was performed. The combination of O- and H-antigen results detected from the agglutination test was for the specific Salmonella serotype identification.

Biofilm formation assay

Biofilm formation is one of the major virulence properties of Salmonella. To quantify the biofilm formation of isolated Salmonella spp., the experiment was conducted as described previously (44). Briefly, Salmonella isolates were inoculated in Luria–Bertani (LB) broth (BD Difco, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and incubated at 37°C for 12 h. The bacterial culture was then diluted 1:100 in fresh LB medium and grown at logarithmic phase at 37°C for 6 h. A total of 100 µL of each diluted culture (OD600 = 0.05) was transferred to a 96-well plate. The plates were then incubated for 24 h at 37°C without shaking. After incubation, the plates were washed three times using 200 µL distilled water and allowed to dry. Subsequently, 125 µL of 0.01% crystal violet (CV) solution was added to all the wells containing the dried biofilms. The plates were then washed twice with sterile water and allowed to dry. The CV was dissolved using 30% acetic acid, and the absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 540 nm using Sunrise microplate reader (Tecan, Morrisville, NC, USA). Four replicate wells of each isolate were used. LB broth was used as a blank control (45).

The optical density (ODsample, ODs) could reflect the adhesion ability of biofilm, which was differentiated by the critical OD (ODcontrol, ODc). The ODc was calculated from the arithmetic mean of the absorbance of negative controls with the addition of three times the standard deviation (SD, ODc = mean absorbance of NC + 3(SD)). The following classification was applied for the categorization of biofilm formation level: no biofilm production (OD ≤ ODc), weak biofilm production (WBP; ODc ≤ OD ≤ 2 ODc), moderate biofilm production (MBP; 2ODc ≤ OD ≤ 4 ODc), and strong biofilm production (SBP; 4ODc ≤ OD) (45).

Motility assay of Salmonella isolates

To assess the motility of our isolates, swarming and swimming motility assays were performed as described previously (46). The assays were conducted in 12-well plates (2.26 cm in diameter). Swarming motility was tested on plates containing Nutrient Broth (NB) (BD Difco, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), 0.5% glucose (w/v), and 0.5% bacteriological agar, while swimming motility was tested on plates with NB, 0.5% glucose, and 0.25% bacteriological agar (BD Difco, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Using a sterile tip, an overnight Salmonella culture (OD600: 0.05) was lightly touched and gently spotted in the center of both swarming and swimming plates, followed by incubation at 37°C for 24 h. Turbid zone formation rates (in millimeters) were recorded at 5 h for swimming plates, and diameters of swarming Salmonella were measured at 12 h. Salmonella Typhimurium ATCC 14028 served as the positive control. Motility diameters were recorded in millimeters. Results included at least three independent assay observations.

Molecular detection of virulence genes

To determine the virulence profile of the positive isolates, virulence genes were tested using PCR. DNA extraction was performed using the boiling method as described above (41). The targeted virulence genes of Salmonella enterica include structure and cell invasion genes (invA and sopB), regulatory protein genes (hilA, hilC, and hilD), fimbrial genes related to biofilm formation (csgA and csgB), effector protein genes (sopB and avrA), pathogenicity island genes (spiA and spiC), immune system evasion-related genes (spvC), oxidative stress survival-related genes (sodC1), magnesium homeostasis (mgtC), superoxide peroxidase-producing genes (sodC1), flagellar genes related to motility (fliC, flhD, flgM, fliA, and motA), and secretion system-related genes (siiD and spvC). Primers used in this study are listed in Table S2. PCR amplifications were performed in a final volume of 10 µL containing DNA template (1 µL), ×2 PCR Green Master mix (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) (5 µL), 10 pmol/µL of each primer (Thermofisher, Lexington, KY, USA) (0.5 µL), and 3 µL nuclease-free water. PCR amplifications using primers in this study were conducted at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min; the corresponding temperatures for annealing (TA) are listed in Table S1 for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min, and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. All PCR amplifications were carried out in a BioRad thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The amplified DNA products were visualized using 1% (w/v) agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide and photographed using a gel documentation system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Antibiotic susceptibility test (AST)

To assess the susceptibility profile of the positive isolates to antibiotics, the broth microdilution method was conducted using Thermo Scientific Sensititre Equine EQUIN2F (Thermofisher, Lexington, KY, USA) AST plate. Each plate includes 10 antimicrobial agents, such as amikacin (AK; 4–32 μg/mL), ampicillin (AMP; 0.25–32 μg/mL), ceftazidime (CAZ; 0.5–64 μg/mL), ceftiofur (XNL; 0.5–64 μg/mL), chloramphenicol (CL; 4–32 μg/mL), doxycycline (DOX; 2–16 μg/mL), imipenem (IMP; 1–8 μg/mL), tetracycline (TE; 2–8 μg/mL), trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (COT; 0.5/9.5-4/76 µg/mL), and gentamicin (GEN; 1–8 μg/mL) (Table S3). All isolates were grown on Columbia agar plates with 5% sheep blood (Becton Dickinson, NJ, USA) and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. The AST was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, a 0.5 McFarland suspension (OD600 = 0.08–0.1) of the strain was prepared in distilled water, using a spectrophotometer, and then 10 µL of this suspension was mixed into the Sensititre Mueller Hinton broth. Each of the 96 wells was inoculated with 50 µL of the mixed suspension. The plate was incubated at 37°C, and the minimum inhibitory concentration (MICs) reading was taken after 18 h using the Thermo Scientific Sensititre OptiRead Automated Fluorometric Plate Reading System. The breakpoints for each antibiotic were determined according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines (CLSI 2024) (Table S3).

Molecular detection of antibiotic resistance genes

To detect the antibiotic resistance genes among the isolates, PCR was conducted targeting specific genes. Genes that are responsible for the phenotypic aminoglycoside resistance (aacA [3]), beta-lactamase resistance (blaTEM, blaCTX-M, blaSHV2, and blaOXA-9), tetracycline resistance (tetB), amphenicol (floR), streptomycin resistance (strA), sulfonamide resistance (sul2), macrolides (ermB2), and quinolone resistance (qnrB2) were targeted for this genotypic resistance screening (Table S4). PCR amplifications were performed in a final volume of 10 µL containing DNA template (1 µL), ×2 PCR Green Mastermix (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) (5 µL), 10 pmol/µL of each primer (Thermofisher, Lexington, KY, USA) (0.5 µL), and 3 µL nuclease-free water. PCR amplifications using primers in this study were conducted at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min; the corresponding temperatures for annealing (TA) are listed in Table S3 for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min, and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. All PCR amplifications were carried out in a BioRad thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The amplified DNA products were visualized using 1% (w/v) agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide and photographed using a gel documentation system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

Association between sample type and Salmonella prevalence was determined using Fisher’s Exact Test and descriptive statistics was performed to find out the 95% CI level. These analyses were performed in R using the stats package. A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to assess the impact of two independent factors on the categorical outcome of biofilm formation and motility assays. The Complex Heatmap package in R was used to generate the hierarchical clustering heatmap (47). The correlation between AMR and virulence genes was calculated using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. The corrplot package was utilized to visualize the correlation matrix, providing an intuitive graphical representation of the correlations between variables (48). All the results were deemed significant if the P-value was less than 0.05.

RESULTS

Prevalence and serotyping of Salmonella

Out of 2,182 samples collected, Salmonella was recovered from 26 samples with an overall prevalence of 1.2%. These Salmonella were isolated from 26 individual horses. A significantly higher prevalence of 57.7% (15/26, 95% CI: 38.9%–74.5%, P < 0.0001) of Salmonella was observed in intestine samples of horses (Table 1). Significantly higher prevalence was observed in foals (61.5%) and female horses (76.9%) (Table 1). Additionally, 10 different Salmonella serotypes were detected within the positive isolates. The most prevalent serotype observed in this study was Salmonella Typhimurium (34.6% (9/26); 95% CI: 16.4%–52.8%), followed by Salmonella Thompson (7.7%; 2/26, 95% CI: 2.1%–24.2%). Other serotypes observed were Salmonella Hartford, Salmonella Anatum, Salmonella 4,(5), ,12:b:-, Salmonella 4,(5), 12:i:-, Salmonella Agbeni, Salmonella Bovismorbificans, Salmonella Enteritidis and Salmonella Mbandaka (Table 2)

TABLE 1.

The distribution of Salmonella prevalence across various organs, age groups, and sexes of necropsied horses

| Variables | Site isolated | No. of the positive isolates (Total = 26) | Prevalence (%) | Lower CI (%) | Upper CI (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolated site | Colon | 7 | 26.92 | 13.70 | 46.08 | <0.0001 |

| Feces | 2 | 7.69 | 2.14 | 24.14 | ||

| Kidney | 1 | 3.85 | 0.68 | 18.89 | ||

| Liver | 1 | 3.85 | 0.68 | 18.89 | ||

| Small intestine | 15 | 57.69 | 38.95 | 74.46 | ||

| Age | Foal (0–1 year) | 16 | 61.54 | 37.88 | 85.19 | <0.05 |

| Yearling (>1–2 years) | 2 | 7.69 | 4.73 | 10.64 | ||

| Young (>2–4 years) | 1 | 3.85 | 2.37 | 5.32 | ||

| Adult (>4–15 years) | 7 | 26.92 | 16.57 | 37.27 | ||

| Sex | Female | 20 | 76.92 | 57.95 | 88.97 | <0.05 |

| Male | 6 | 23.08 | 11.03 | 42.05 |

TABLE 2.

Serotype prevalence of Salmonella spp

| Salmonella serotypes | Isolate no. (Total= 26) | Prevalence (%) | Lower CI (%) | Upper CI (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4,(5), 12:b:- | 2 | 7.69 | 2.14 | 24.14 |

| 4,(5), 12:i:- | 2 | 7.69 | 2.14 | 24.14 |

| Agbeni | 1 | 3.85 | 0.68 | 18.89 |

| Anatum | 3 | 11.54 | 4.00 | 28.98 |

| Bovismorbificans | 1 | 3.85 | 0.68 | 18.89 |

| Hartford | 3 | 11.54 | 4.00 | 28.98 |

| Enteritidis | 1 | 3.85 | 0.68 | 18.89 |

| Mbandaka | 2 | 7.69 | 2.14 | 24.14 |

| Thompson | 2 | 7.69 | 2.14 | 24.14 |

| Typhimurium | 9 | 34.62 | 16.4 | 52.8 |

Biofilm formation

To track the biofilm formation ability of the isolated Salmonella serotypes, all 26 isolates were subjected to CV assay. All the isolates were found to be biofilm producers, and among them, 7.7% (2/26, 95% CI: 2.1%–24.1%) were strong biofilm producers, 38.5% (10/26, 95% CI: 22.4%–57.5%) were moderate biofilm producers, and 53.8% (14/26, 95% CI: 35.4%–71.2%) were weak biofilm producers (Table 3; Table S5). Significant differences in biofilm production were observed among the isolates categorized as weak biofilm producers (WBP), moderate biofilm producers (MBP), and strong biofilm producers (SBP) (P < 0.01) (Fig. 1). All SBP isolates (E25 and E26) belonging to Salmonella Mbandaka serotype. Isolates belonging to Salmonella Thompson, S. Bovismorbificans, and Salmonella Enteritidis were MBP. In addition, 100% of Salmonella Agbeni and 77.8% of Salmonella Typhimurium serotypes were WBP (Table 4; Table S5).

TABLE 3.

Prevalence of biofilm formationa

| Category | No. of isolates | Prevalence (%) | Lower CI (%) | Upper CI (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MBP | 10 | 38.46 | 22.43 | 57.47 |

| SBP | 2 | 7.69 | 2.14 | 24.14 |

| WBP | 14 | 53.85 | 35.46 | 71.24 |

MBP, moderate biofilm producers; SBP, strong biofilm producers; WBP, weak biofilm producers.

Fig 1.

Biofilm production in Salmonella isolates. The figure shows a boxplot representing the absorbance (OD = 550) values across three categories of biofilm production in Salmonella isolates: moderate biofilm producers (MBP), strong biofilm producers (SBP), and weak biofilm producers (WBP). The absorbance values are indicative of the extent of biofilm formation, with higher absorbance reflecting stronger biofilm production. Results suggest that statistically significant differences are visible among all the categories of biofilm producers. SBP strains produces significantly higher amount of biofilm than MBP and WBP. P-value annotation legend: ns: non-significant; ****P < 0.0001.

TABLE 4.

Prevalence of biofilm formation in different Salmonella serotypesa

| Serotype | MBP % (n= 9) | SBP % (n= 2) | WBP % (n=15) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4,(5), 12:b:- | 50 | 0 | 50 |

| 4,(5), 12:i:- | 50 | 0 | 50 |

| Agbeni | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| Anatum | 33.33 | 0 | 66.67 |

| Bovismorbificans | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Enteritidiis | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Hartford | 66.67 | 0 | 33.33 |

| Mbandaka | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| Thompson | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Typhimurium | 22.22 | 0 | 77.78 |

MBP, moderate biofilm producers; SBP, strong biofilm producers; WBP, weak biofilm producers.

Motility determination of Salmonella isolates

The isolates were tested for their ability to move across both swarming and swimming plates. All isolates exhibited swarming behavior, forming smooth, featureless colonies, with motility measurements averaging more than 2.6 ± 0.5 mm. The highest swarming motility was recorded in isolates belonging to Salmonella Typhimurium (E14) and Salmonella Hartford (E21), with 3.5 ± 0.5 and 3.6 ± 0.5 mm diameters, respectively (Table S6; Fig. S1). Additionally, swimming motility was observed across all the isolates with an average of 4.0 ± 0.9 mm diameter. The highest swimming motility was observed in isolates belonging to Salmonella Typhimurium (E12 and E17) with a 6 mm diameter each (Table S5; Fig. S1B).

Virulence genes detection within Salmonella isolates

Overall, 26 virulence genes were screened among the Salmonella isolates. Our results showed that 100% of the isolates contained invA, hilA, mgtC, spiA, filA, motA, figG, figH, figC, fimC, fimD, fimF, fimH csgA, and csgB genes. These genes are responsible for several virulence factors, including invasion, intracellular survival, motility, biofilm formation, and regulatory genes (Table 5). Additionally, the type III secretion system (T3SS) effector protein genes, such as avrA and siiD possessed the second highest prevalence (96.1%) among the isolates. Other gene predispositions included flagellar protein gene fliC and superoxide dismutase producing gene sodC1 (46.2%), regulatory protein gene hilC and invasion gene sipD (88.5%), and pathogenicity island gene spiC (73.1%) were also detected. Only 30.8% of spvC genes were detected (Table 5; Fig. S2).

TABLE 5.

Prevalence of virulence genes within the isolated bacteria

| Group | Function | Gene | Number of the positive isolates | Prevalence % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Invasion related gene | T3SS component | invA | 26 | 100 |

| T3SS component | sipD | 23 | 88.5 | |

| T3SS component | spiC | 19 | 73.1 | |

| T3SS component | spiA | 26 | 100 | |

| Immunity | Invade host immunity | avrA | 25 | 96.2 |

| Invade host immunity | sopB | 23 | 88.5 | |

| Suppress host immune response | spvC | 8 | 30.8 | |

| Defense against oxidative stress | sodC1 | 12 | 46.2 | |

| Survival | Survival inside macrophage | mgtC | 26 | 100 |

| Colonization inside host | siiD | 25 | 96.2 | |

| Motility | Flagellar component | fliC | 12 | 46.2 |

| Flagellar component | figC | 26 | 100 | |

| Flagellar component | figH | 26 | 100 | |

| Flagellar component | filA | 26 | 100 | |

| Fimbrial assembly chaperone | fimC | 26 | 100 | |

| Type one fimbriae usher | fimD | 26 | 100 | |

| Structural fimbrial subunit | fimF | 26 | 100 | |

| Fimbrial tip adhesin | fimH | 26 | 100 | |

| Flagellar motor component | motA | 26 | 100 | |

| Biofilm | Biofilm formation | csgA | 26 | 100 |

| Biofilm Formation | csgB | 26 | 100 | |

| Regulatory gene | Transcriptional regulation of SPI-1 | hilA | 26 | 100 |

| Transcriptional regulation of SPI-1 | hilC | 17 | 65.4 | |

| Transcriptional regulation of SPI-1 | hilD | 17 | 65.4 |

Antimicrobial susceptibility test

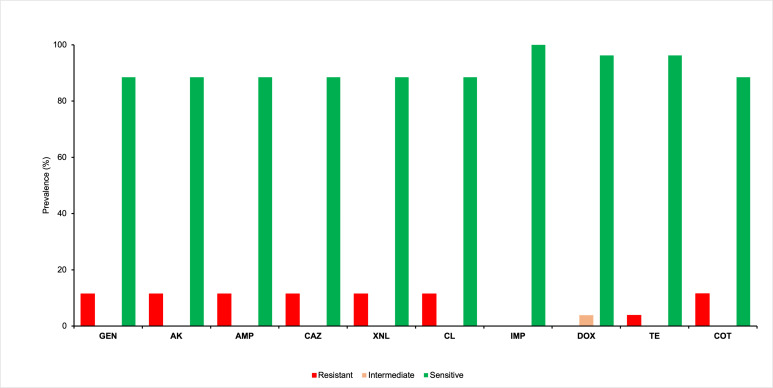

Antimicrobial susceptibility test was performed using broth microdilution for 26 Salmonella isolates. Three isolates (11.5%) were found resistant to aminoglycosides (gentamicin and amikacin), penicillin (ampicillin), cephalosporins (ceftazidime and ceftiofur), chloramphenicol, and sulfonamides (trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole). Besides, 3.9% of the isolates possessed resistance to tetracycline. Imipenem (100%) was found to be the most effective against these isolates, followed by doxycycline (96.2%) (Table S7; Fig. 2). Among the 26 isolates, three (11.5%) exhibited MDR. The MDR isolates exhibited two distinct resistance patterns, showing resistance to five and six antibiotic groups, as presented in Table 6. Multidrug resistant Salmonella serotypes were Salmonella Typhimurium and Salmonella Mbandaka. Both S. Mbandaka (2/2, 100%) detected in this study exhibited resistance to the same group of antibiotics, including amikacin, ampicillin, ceftazidime, ceftiofur, chloramphenicol, gentamicin, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. In contrast, 33.4% (1/3) S. Typhimurium showed resistance to tetracycline in addition to the aforementioned antibiotics (Table 6).

Fig 2.

Antibiotic resistance profiles of Salmonella enterica isolates. Amikacin (AK), ampicillin (AMP), ceftazidime (CAZ), ceftiofur (XNL), chloramphenicol (CL), doxycycline (DOX), imipenem (IMP), tetracycline (TE), trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (COT), and gentamicin (GEN). Approximately 11.5% of the isolates were resistant to XNL, GEN, COT, CL, CAZ, AMP, and AK, while 3.9% of the isolates showed resistance to TE.

TABLE 6.

Multidrug resistance profile of the Salmonella isolatesa

| MDR phenotypes | No. of antibiotics group | Name of the groups | No. of isolates (%) | Serotypes | MDR prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AK, AMP, CAZ, XNL, CL, GEN, COT | 5 | Aminoglycosides, penicillins, cephalosporins, phenicol, sulfonamides | 2 (7.69) | S. Mbandaka | 11.53% |

| AK, AMP, CAZ, XNL, CL, GEN, TE, COT | 6 | Aminoglycosides, penicillins, cephalosporins, phenicol, tetracyclines, sulfonamides | 1 (3.85) | S. Typhimurium |

AK, amikacin; AMP, ampicillin; CAZ, ceftazidime; XNL, ceftiofur; CL, chloramphenicol; DOX, doxycycline; GEN, gentamicin; IMP, imipenem; TE, tetracycline; COT, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.

Prevalence of antibiotic resistance genes

Antibiotic resistance genes were detected by PCR among these Salmonella isolates. It was observed that the sulfonamide-resistance gene (sul2) was identified as the most prevalent (19.2%) gene among the isolates. (Fig. 3). Beta-lactamase-producing genes, including blaTEM, blaCTX-M, and blaSHV-2, were identified in 11.5% of the isolates, while 3.8% of the isolates contain blaOXA-9 genes. The aminoglycoside-resistance gene (aacA) was identified in 11.5% of the isolates, while the amphenicol resistance gene (floR) and tetracycline resistance gene (tetB) were detected in 11.5% of the isolates. Furthermore, it was observed that 15.4% of the isolates contained streptomycin resistance gene (strA), while only 3.8% contained the deduced macrolide (ermB2) and quinolone (qnrB2) resistance genes. The prevalence of all antibiotic resistant genes are shown in Table S8.

Fig 3.

Prevalence of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genes by function category. Our results showed that sulfonamide-resistance gene (sul2) was 19.2% prevalent among the isolates.

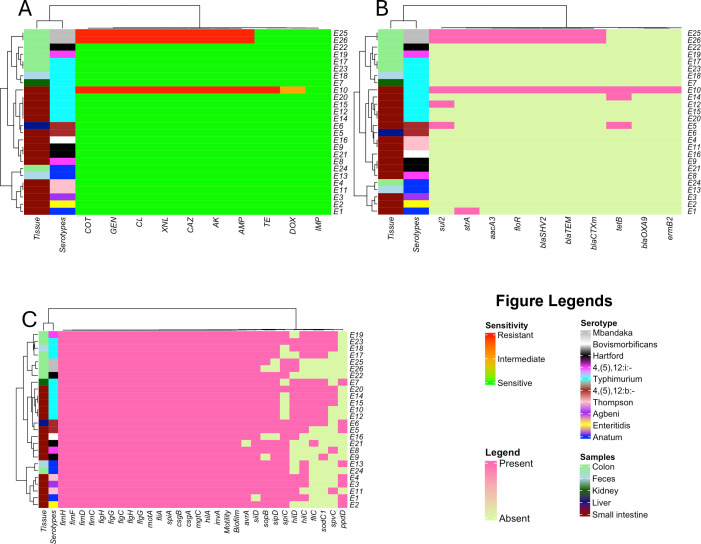

Correlation between phenotypic and genotypic resistance of Salmonella isolates

Hierarchical clustering heatmaps were generated to identify patterns and group similarities among the isolates based on their isolation site, serotype, phenotypic and genotypic AMR characteristics, as well as their virulence. The isolates, organized by serotype and isolation site, demonstrated distinct clustering in Fig. 4. A higher prevalence of S. Typhimurium was observed across various sample types, including the small intestine, kidney, feces, and colon. S. Anatum was isolated from different locations including the small intestine, feces, and colon, while Salmonella Mbandaka exclusively recovered from colon tissue. In contrast, S. Hartford and S. Enteritidis were solely isolated from the small intestine (Fig. 4).

Fig 4.

Heatmaps showing phenotypic and genotypic resistance profiles with clustering as a dendrogram. The clustering of isolates is based on their (A) phenotypic resistance pattern. Amikacin (AK), ampicillin (AMP), ceftazidime (CAZ), ceftiofur (XNL), chloramphenicol (CL), doxycycline (DOX), imipenem (IMP), tetracycline (TE), trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (COT), gentamicin (GEN). (B) Presence and absence of AMR genes. (C) presence and absence of virulence genes.

The heatmap generated from the phenotypic AMR profiles revealed that isolates E25 and E26 isolated from the colon, which belonged to Salmonella Mbandaka serotype clustered together, exhibiting resistance to AK, AMP, CL, CAZ, XNL, GEN, and COT. Additionally, MDR Salmonella Typhimurium isolate (E10) clustered with other Salmonella Typhimurium isolates recovered from the small intestine that showed resistance to AK, AMP, CL, CAZ, XNL, GEN, TE, and COT. In contrast, rest of the isolates displayed complete sensitivity to all the antibiotics tested in this study (Fig. 4A).

A similar clustering pattern was observed for isolates E10, E25, and E26 in the heatmap based on their AMR genes, where these isolates contained sul2, strA, aacA (3), floR, blaSHV-2, blaTEM, and blaCTX-m genes (Fig. 4B). Additionally, E14 and E5 have the tetB gene, and the sul2 gene was found to be common between isolates E5 and E12.

The heatmap generated based on the virulence profiles revealed different clustering than AMR heatmap (Fig. 4C). The majority of the virulence genes were present among the isolates. Clustering of isolates E17, E18, E19, and E23 was observed in first clade, where E17, E18, and E23 belonged to Salmonella Typhimurium and E19 belonged to Salmonella 4,(5), 12:i:- serotype. Isolate E23 had all the virulence genes present, except ppdD, and E19 lacked hilD and ppdD. Interestingly, isolates E25 and E26 also clustered together; however, the sopB gene responsible for invading host cell immunity was present in E25 but absent in E26 (Fig. 4C).

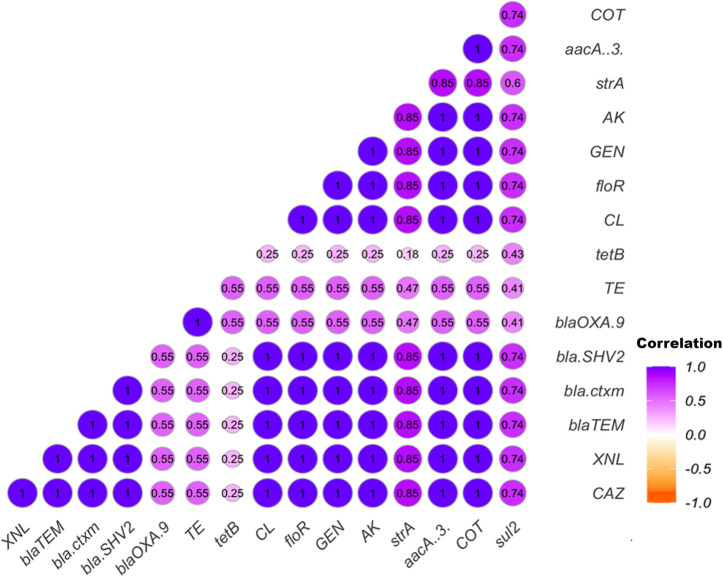

Pearson’s correlation coefficient analysis was conducted to assess the correlation between phenotypic and genotypic antimicrobial resistance, along with the significance levels. All antibiotics showed significant positive correlations (P ≤ 0.05) with each other (Fig. 5). Additionally, the correlation matrix of AMR genes revealed a strong positive relationship between floR and aacA (3) (r = 1; P < 0.001) and among the beta-lactamase-producing genes blaTEM, blaSHV-2, and blaCTX-m (r = 1; P < 0.001). A similar trend was observed between the aacA (3) gene and the beta-lactamase-producing genes, except for blaOXA-9. Further details are provided in Fig. 5.

Fig 5.

Pearson’s correlation coefficient indicating the relationship between phenotypic and genotypic antibiotic resistance, with associated significance levels. Correlation matrix shows correlation between phenotypic antimicrobial resistance and antimicrobial resistance genes. Amikacin (AK), ampicillin (AMP), ceftazidime (CAZ), ceftiofur (XNL), chloramphenicol (CL), doxycycline (DOX), imipenem (IMP), tetracycline (TE), trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (COT), gentamicin (GEN).

DISCUSSION

The equine industry has a significant economic impact on the United States, contributing approximately $177 billion per year (49). The equine sector is associated with an estimated 2.2 million jobs, counting both direct and indirect employment (49). The presence of Salmonella in horses can pose a risk to both the equine farms and their associated personnel, as there is a high potential for Salmonella infections to be transferred between different hosts. Therefore, it is crucial to conduct monitoring to detect the presence of Salmonella to prevent its epidemic in both animals and humans. Our study investigates the presence of various Salmonella serotypes in clinical samples submitted to a veterinary diagnostic laboratory. The study also explored their antimicrobial resistance profiles and virulence factors, including biofilm formation, motility, as well as AMR, and virulence associated genes.

In this study, Salmonella was identified in samples collected from necropsied horses, with a prevalence of 1.2%. This prevalence is lower than previous findings obtained from fecal laboratory testing conducted as part of the National Animal Health Monitoring System (NAHMS) Equine 2015–16 in the USA (2.0%) and from hospitalized horse feces in Chile (3.85%) (11, 50). However, some studies reported higher Salmonella shedding in colic-affected horses (51). One of the studies in South Africa showed that the prevalence of Salmonella in necropsied horses with a history of colic was 59% (52). The presence of Salmonella infections in clinical samples of necropsied horses is a public health and biosurity concern. Fecal shedding of Salmonella occurred in hospitalized horses posing a potential risk of transmission to humans, especially the horse owners and farmers, as well as other hospitalized animals. Previous studies reported that diseased animals are more susceptible to fecal shedding of Salmonella than healthy animals (5).

Our study has found a higher prevalence of Salmonella in the intestinal samples (57.7%). The intestinal samples had a higher prevalence because the bacteria invade the intestinal epithelial cells by inducing membrane ruffling in intestinal cells, which causes them to intake the bacteria (53). Although the cecum is recognized as a major predilection site for Salmonella, this study did not include cecum samples. This was due to the sampling process being conducted through the diagnostic laboratory, where testing was performed at the discretion of veterinarian or pathologists, which did not include cecal samples. The most common serotype reported in horses was Salmonella Typhimurium; however, other serotypes including Salmonella Enteritidis, Salmonella Abortusequi, Salmonella Heidelberg, Salmonella Newport, Salmonella Agona, Salmonella Anatum, and other “atypical” serotypes were also found (32, 54). In this study, Salmonella Typhimurium was the most prevalent, and this result aligns with the previous studies (11, 37). Salmonella Typhimurium is the predominant serotype responsible for foodborne illnesses globally. Its increased prevalence in horses poses a significant public health risk within the equine industry. However, other serotypes are equally important reported in horses previously (5, 12–14).

Biofilms are complex microbial communities that attach to surfaces and are embedded in a self-produced extracellular matrix. The extracellular matrix impedes the activity of antibiotics by preventing their penetration into bacterial cells, thus preventing the antibiotics from reaching their intended target receptors (55). Our results showed that all the isolates were biofilm producers, whereas 7.7% were strong biofilm producers. Salmonella Typhimurium and Salmonella Thompson serotypes were among moderate biofilm producers and Salmonella Mbandaka were among strong biofilm producers. Our findings were in accordance with previous studies (56, 57). The cell surface attachment and biofilm formation of Salmonella are mediated by amyloid-like cell-surface proteins that are highly aggregative and non-branching, and encoded by the Curli protein (csg) operon (58). Our results revealed that all our isolates contain the csgA and csgB genes, which align with the observed phenotypic outcome of biofilm formation (Fig. 5C). In addition to biofilm, all the isolates found motile where they showed both swimming and swarming motility. Strong swarming and swimming motility were observed among 19.2% and 30.8% isolates, respectively. Salmonella Typhimurium was found highly motile in both types of motility (swimming and swarming), which has been reported in the previous studies (59). All the isolates in this study were found to carry the flagellar and fimbrial genes, including fliA, motA, flgG, flgH, fimC, fimD, fimF, fimH, figC, and figG. The presence of such genes can be responsible for their motility as described previously (30, 60). This result aligns with the phenotypic result of the motility test where all the isolates were found to be motile (Fig. 5C).

The ability of Salmonella to invade host cells is a pivotal stage in its pathogenesis, facilitating bacterial survival, spread, and infectivity (61). The presence of genes associated with invasion and intracellular survival enables Salmonella to efficiently invade the host’s intestinal epithelial cells and persist within Salmonella-containing vacuoles. These genes also play a role in modulating the immune system, contributing to the pathogen’s virulence (27). The Salmonella pathogenicity island encodes the majority of these virulence-related genes, which are also exceptionally conserved across serotypes (62). Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 (SPI-1) contains the invasion-related genes invA and hilA, from which hilA is a key regulator for invA gene (63). These genes were identified in all the isolates in this study. They have been also reported in a similar study in samples collected from poultry. Genes related to type III secretion system (T3SS) formation were also detected including spiA (100%) and sipD (88.5%), as reported in previous studies (64, 65). Additionally, Salmonella plasmid virulence (spv) genes are plasmid-dependent and are serotype-specific in Salmonella. Our study detected spvC gene among 30.8% of the isolates, and the highest prevalence was observed among Salmonella Typhimurium serotypes and has also been reported in Salmonella from poultry in a previous study (66).

Though Salmonellosis causes self-limiting gastroenteritis in humans, antimicrobial treatments are necessary for the complete removal of this bacteria. However, AMR is developing in an upward manner, and AMR in Salmonella has become a threat to public and animal health. The prevalence of MDR Salmonella isolates is steadily increasing in horses. Between 2001 and 2013, Salmonella isolated from hospitalized horses at Cornell University showed resistance to multiple antibiotics, including amoxicillin–clavulanic acid (29%), ampicillin (45.5%), cefazolin (42.2%), cefoxitin (27.5%), ceftiofur (37.3%), chloramphenicol (45.2%), and tetracycline (46.1%). In this study, 11.5% of isolates were MDR, and the AMR pattern includes gentamicin (11.5%), amikacin (11.5%), ampicillin (11.5%), ceftazidime (11.5%), ceftiofur, chloramphenicol (11.5%), tetracycline (3.9%), and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (11.5%). Similarly, a previous study has been reported MDR prevalence (10.2%) within the Salmonella isolates from horses (32). In comparison, another study reported a higher prevalence of MDR Salmonella (57%) in horses (36). The wide range of sampling locations across the USA along with large number of samples, and the extended 13-year duration of the study may have contributed to the variation in these results. Additionally, they evaluated different antimicrobial regimens, which is an additional cause of MDR strains with a high affinity (41). However, our study found imipenem to be the most efficacious drug against Salmonella, consistent with the previous studies conducted on equines in the USA (36). A possible explanation is that imipenem is less common in veterinary practice and restricted to human use only (67).

To confirm the agreement between phenotypic and genotypic antimicrobial resistance of the isolates, PCR detection of AMR genes was performed. Beta-lactamase-producing genes blaTEM, blaCTXM, and blaSHV2 were detected in three isolates (11.5%), and these isolates were resistant to extended-spectrum cephalosporins. Multiple beta-lactamase-producing genes were reported previously in several studies in Salmonella isolated from horses (68, 69). Our study identified a Salmonella isolate carrying the blaOXA-9 gene, which is also associated with cephalosporins resistance. Tetracycline resistance gene tetB was detected among three isolates; however, only one isolate was resistant to tetracycline. Because of their evolutionary limit, the other two might downregulate the tetB gene expression (70). The study highlights the critical role of monitoring Salmonella in horses, given its potential impact on public health, biosecurity, and the equine industry. Despite the relatively low prevalence of Salmonella in clinical samples compared with previous studies, the detection of various virulence factors and AMR genes, including those associated with biofilm formation and motility, raises concerns about the persistence and spread of these pathogens. These findings highlight the challenges in managing Salmonella infections within equine populations, emphasizing the critical need for continuous, comprehensive surveillance to minimize transmission risks to humans, other animals, and the environment.

Conclusion

Our study highlights the pressing concern of AMR in S. enterica isolates from horses, along with significant virulence potential and biofilm formation capability. The presence of MDR and virulent Salmonella serotypes in horses poses a potential threat to the equine industry. Salmonella Typhimurium was the predominant serotype detected in this study, alongside nine other serotypes. Swarming and swimming motility were observed in all isolates, along with biofilm production. Three isolates were identified as MDR with the presence of AMR genes. A significant number of isolates also harbored virulence genes. The detection of such isolates demonstrates the threat of pathogenic Salmonella outbreaks in horses, as well as the potential risk to human health, especially the horse owners and farmers. Fecal shedding of Salmonella can lead to nosocomial transmission, and spreading the infection to uninfected horses within hospital settings. The characterization of these isolates provides an accurate profile of Salmonella, highlighting the emerging threat posed by these pathogens. These findings underscore the need for comprehensive surveillance and innovative approaches to manage and mitigate the impact of these pathogens on equine health and beyond. Comprehensive analysis using whole genome sequencing is essential to fully characterize the AMR and virulence gene profiles. Furthermore, studies on transmission dynamics employing whole genome sequencing are crucial to identify the source of Salmonella infections in equine populations and to understand its potential dissemination to the environment. These studies will assist hospitals and other authorities in identifying the source of contamination and implementing necessary biosecurity measures to prevent Salmonella transmission.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the Center of Biomedical Research Excellence (COBRE) for Translational Chemical Biology (CTCB, NIH P20 GM130456), the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (grant number KL2TR001996), and the University of Kentucky Igniting Research Collaborations program.

Contributor Information

Yosra A. Helmy, Email: yosra.helmy@uky.edu.

Aude A. Ferran, Innovations Therapeutiques et Resistances, Toulouse, France

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/spectrum.02501-24.

Swarming and swimming motility of Salmonella isolates.

Prevalence of virulence genes by their function category.

Legends for supplemental figures.

Tables S1 to S8.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. CDC . 2024. Salmonella, on centers for disease control and prevention. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/index.html

- 2. Schott II HC, Ewart SL, Walker RD, Dwyer RM, Dietrich S, Eberhart SW, Kusey J, Stick JA, Derksen FJ. 2001. An outbreak of salmonellosis among horses at a veterinary teaching hospital. javma 218:1152–1159. doi: 10.2460/javma.2001.218.1152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. WHO . 2018. Salmonella (non-typhoidal), on World Health Organization. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/salmonella-(non-typhoidal)#:~:text=Key%20facts%201%20Salmonella%20is%201%20of%204,have%20emerged%2C%20affecting%20the%20food%20chain.%20More%20items

- 4. Zhang S, Yin Y, Jones MB, Zhang Z, Deatherage Kaiser BL, Dinsmore BA, Fitzgerald C, Fields PI, Deng X. 2015. Salmonella serotype determination utilizing high-throughput genome sequencing data. J Clin Microbiol 53:1685–1692. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00323-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lamichhane B, Mawad AMM, Saleh M, Kelley WG, Harrington PJ 2nd, Lovestad CW, Amezcua J, Sarhan MM, El Zowalaty ME, Ramadan H, Morgan M, Helmy YA. 2024. Salmonellosis: an overview of epidemiology, pathogenesis, and innovative approaches to mitigate the antimicrobial resistant infections. Antibiotics (Basel) 13:76. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics13010076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Javed R, Taku AK, Gangil R, Sharma RK. 2016. Molecular characterization of virulence genes of Streptococcus equi subsp. equi and Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus in equines. Vet World 9:875–881. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2016.875-881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Burgess BA. 2023. Salmonella in horses. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract 39:25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cveq.2022.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ernst NS, Hernandez JA, MacKay RJ, Brown MP, Gaskin JM, Nguyen AD, Giguere S, Colahan PT, Troedsson MR, Haines GR, Addison IR, Miller BJ. 2004. Risk factors associated with fecal Salmonella shedding among hospitalized horses with signs of gastrointestinal tract disease. J Am Vet Med Assoc 225:275–281. doi: 10.2460/javma.2004.225.275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kim LM, Morley PS, Traub-Dargatz JL, Salman MD, Gentry-Weeks C. 2001. Factors associated with Salmonella shedding among equine colic patients at a veterinary teaching hospital. J Am Vet Med Assoc 218:740–748. doi: 10.2460/javma.2001.218.740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dargatz DA, Traub-Dargatz JL. 2004. Multidrug-resistant Salmonella and nosocomial infections. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract 20:587–600. doi: 10.1016/j.cveq.2004.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Soza-Ossandón P, Rivera D, Tardone R, Riquelme-Neira R, García P, Hamilton-West C, Adell AD, González-Rocha G, Moreno-Switt AI. 2020. Widespread environmental presence of multidrug-resistant Salmonella in an equine veterinary hospital that received local and international horses. Front Vet Sci 7:346. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2020.00346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rothers KL, Hackett ES, Mason GL, Nelson BB. 2020. Atypical Salmonellosis in a horse: implications for hospital safety. Case Rep Vet Med 2020:7062408. doi: 10.1155/2020/7062408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ward MP, Brady TH, Couëtil LL, Liljebjelke K, Maurer JJ, Wu CC. 2005. Investigation and control of an outbreak of salmonellosis caused by multidrug-resistant Salmonella typhimurium in a population of hospitalized horses. Vet Microbiol 107:233–240. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Grandolfo E, Parisi A, Ricci A, Lorusso E, Siena R, Trotta A, Buonavoglia D, Martella V, Corrente M. 2018. High mortality in foals associated with Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica Abortusequi infection in Italy. J Vet Diagn Invest 30:483–485. doi: 10.1177/1040638717753965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McCain CS, Powell KC. 1990. Asymptomatic salmonellosis in healthy adult horses. J Vet Diagn Invest 2:236–237. doi: 10.1177/104063879000200318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Helmy YA, Kabir A, Saleh M, Kennedy LA, Burns L, Johnson B. 2024. Draft genome sequence analysis of multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Mbandaka harboring colistin resistance gene mcr-9.1 isolated from foals in Kentucky, USA. Microbiol Resour Announc 13:e00737–24. doi: 10.1128/mra.00737-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Helmy YA, Taha-Abdelaziz K, Hawwas H-H, Ghosh S, AlKafaas SS, Moawad MMM, Saied EM, Kassem II, Mawad AMM. 2023. Antimicrobial resistance and recent alternatives to antibiotics for the control of bacterial pathogens with an emphasis on foodborne pathogens. Antibiotics (Basel) 12:274. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics12020274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. House JK, Smith BP. 2000. Salmonella in horses.

- 19. Abebe E, Gugsa G, Ahmed M. 2020. Review on major food-borne zoonotic bacterial pathogens. J Trop Med 2020:4674235. doi: 10.1155/2020/4674235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kabir A, Lamichhane B, Habib T, Adams A, El-Sheikh Ali H, Slovis NM, Troedsson MHT, Helmy YA. 2024. Antimicrobial resistance in equines: a growing threat to horse health and beyond-a comprehensive review. Antibiotics (Basel) 13:713. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics13080713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bhandari M, Poelstra JW, Kauffman M, Varghese B, Helmy YA, Scaria J, Rajashekara G. 2023. Genomic diversity, antimicrobial resistance, plasmidome, and virulence profiles of Salmonella isolated from small specialty crop farms revealed by whole-genome sequencing. Antibiotics (Basel) 12:1637. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics12111637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rahman MM, Hossain H, Chowdhury MSR, Hossain MM, Saleh A, Binsuwaidan R, Noreddin A, Helmy YA, El Zowalaty ME. 2024. Molecular characterization of multidrug-resistant and extended-spectrum β-lactamases-producing Salmonella enterica serovars Enteritidis and Typhimurium isolated from raw meat in retail markets. Antibiotics (Basel) 13:586. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics13070586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zha L, Garrett S, Sun J. 2019. Salmonella infection in chronic inflammation and gastrointestinal cancer. Diseases 7:28. doi: 10.3390/diseases7010028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Helmy YA, El-Adawy H, Abdelwhab EM. 2017. A comprehensive review of common bacterial, parasitic and viral zoonoses at the human-animal interface in Egypt. Pathogens 6:33. doi: 10.3390/pathogens6030033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dougnon TV, Legba B, Deguenon E, Hounmanou G, Agbankpe J, Amadou A, Fabiyi K, Assogba P, Hounsa E, Aniambossou A, De SOUZA M, Bankole HS, Baba-moussa L, Dougnon TJ. 2017. Pathogenicity, epidemiology and virulence factors of Salmonella species: a review. N Sci Biol 9:460–466. doi: 10.15835/nsb9410125 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Simm R, Ahmad I, Rhen M, Le Guyon S, Römling U. 2014. Regulation of biofilm formation in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Future Microbiol 9:1261–1282. doi: 10.2217/fmb.14.88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stepanovic S, Cirkovic I, Ranin L, Svabic-Vlahovic M. 2004. Biofilm formation by Salmonella spp. and Listeria monocytogenes on plastic surface. Lett Appl Microbiol 38:428–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2004.01513.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ibarra JA, Steele-Mortimer O. 2009. Salmonella--the ultimate insider. Salmonella virulence factors that modulate intracellular survival. Cell Microbiol 11:1579–1586. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01368.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kalai Chelvam K, Chai LC, Thong KL. 2014. Variations in motility and biofilm formation of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi. Gut Pathog 6:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1757-4749-6-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bogomolnaya LM, Aldrich L, Ragoza Y, Talamantes M, Andrews KD, McClelland M, Andrews-Polymenis HL. 2014. Identification of novel factors involved in modulating motility of Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium. PLoS One 9:e111513. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mughini-Gras L, Pijnacker R, Duijster J, Heck M, Wit B, Veldman K, Franz E. 2020. Changing epidemiology of invasive non-typhoid Salmonella infection: a nationwide population-based registry study. Clin Microbiol Infect 26:941. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Leon IM, Lawhon SD, Norman KN, Threadgill DS, Ohta N, Vinasco J, Scott HM. 2018. Serotype diversity and antimicrobial resistance among Salmonella enterica isolates from patients at an equine referral hospital. Appl Environ Microbiol 84:e02829-17. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02829-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Xiang Y, Li F, Dong N, Tian S, Zhang H, Du X, Zhou X, Xu X, Yang H, Xie J, Yang C, Liu H, Qiu S, Song H, Sun Y. 2020. Investigation of a Salmonellosis outbreak caused by multidrug resistant Salmonella typhimurium in China. Front Microbiol 11:801. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jajere SM. 2019. A review of Salmonella enterica with particular focus on the pathogenicity and virulence factors, host specificity and antimicrobial resistance including multidrug resistance. Vet World 12:504–521. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2019.504-521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wu S, Hulme JP. 2021. Recent advances in the detection of antibiotic and multi-drug resistant Salmonella: an update. IJMS 22:3499. doi: 10.3390/ijms22073499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cummings KJ, Perkins GA, Khatibzadeh SM, Warnick LD, Aprea VA, Altier C. 2016. Antimicrobial resistance trends among Salmonella isolates obtained from horses in the northeastern United States (2001-2013). Am J Vet Res 77:505–513. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.77.5.505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. van Duijkeren E, Wannet WJB, Heck MEOC, van Pelt W, Sloet van Oldruitenborgh-Oosterbaan MM, Smit JAH, Houwers DJ. 2002. Sero types, phage types and antibiotic susceptibilities of Salmonella strains isolated from horses in the Netherlands from 1993 to 2000. Vet Microbiol 86:203–212. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(02)00007-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Center AHD . 2019. Multi-drug resistant Salmonella in horses. Available from: https://www.vet.cornell.edu/animal-health-diagnostic-center/news/multi-drug-resistant-salmonella-horses

- 39. Popa GL, Papa MI. 2021. Salmonella spp. infection - a continuous threat worldwide. Germs 11:88–96. doi: 10.18683/germs.2021.1244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Goni JI, Hendrix K, Kritchevsky J. 2023. Recovery of Salmonella bacterial isolates from pooled fecal samples from horses. J Vet Intern Med 37:323–327. doi: 10.1111/jvim.16586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hailu W, Helmy YA, Carney-Knisely G, Kauffman M, Fraga D, Rajashekara G. 2021. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance profiles of foodborne pathogens isolated from dairy cattle and poultry manure amended farms in Northeastern Ohio, the United States. Antibiotics (Basel) 10:1450. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10121450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Santos PDM, Widmer KW, Rivera WL. 2020. PCR-based detection and serovar identification of Salmonella in retail meat collected from wet markets in Metro Manila, Philippines. PLoS One 15:e0239457. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pulido-Landínez M, Sánchez-Ingunza R, Guard J, Pinheiro do Nascimento V. 2013. Assignment of serotype to Salmonella enterica isolates obtained from poultry and their environment in southern Brazil. Lett Appl Microbiol 57:288–294. doi: 10.1111/lam.12110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. O’Toole GA, Kolter R. 1998. Initiation of biofilm formation in Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS365 proceeds via multiple, convergent signalling pathways: a genetic analysis. Mol Microbiol 28:449–461. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00797.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Xu Z, Liang Y, Lin S, Chen D, Li B, Li L, Deng Y. 2016. Crystal violet and XTT assays on Staphylococcus aureus biofilm quantification. Curr Microbiol 73:474–482. doi: 10.1007/s00284-016-1081-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Brunelle BW, Bearson BL, Bearson SMD, Casey TA. 2017. Multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium isolates are resistant to antibiotics that influence their swimming and swarming motility. mSphere 2:00306–00317. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00306-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gu Z, Hübschmann D. 2022. Make interactive complex heatmaps in R. Bioinformatics 38:1460–1462. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btab806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wei T, Simko V, Levy M, Xie Y, Jin Y, Zemla J, et al. 2017. Package ‘corrplot’. 56 Statistician. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Council TAH . 2023. Results from the 2023 national equine economic impact study released. Available from: https://horsecouncil.org/press-releases/results-from-the-2023-national-equine-economic-impact-study-released. Retrieved 5 Aug 2024.

- 50. Kohnen AB, Wiedenheft AM, Traub-Dargatz JL, Short DM, Cook KL, Lantz K, Morningstar-Shaw B, Lawrence JP, House S, Marshall KL, Rao S. 2023. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Salmonella and Escherichia coli from equids sampled in the NAHMS 2015-16 equine study and association of management factors with resistance. Prev Vet Med 213:105857. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2023.105857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kilcoyne I, Magdesian KG, Guerra M, Dechant JE, Spier SJ, Kass PH. 2023. Prevalence of and risk factors associated with Salmonella shedding among equids presented to a veterinary teaching hospital for colic (2013-2018). Equine Vet J 55:446–455. doi: 10.1111/evj.13864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. van Rensburg IB, Jardine JE, Carstens JH, van der Walt ML. 1995. The prevalence of intestinal Salmonella infection in horses submitted for necropsy. Onderstepoort J Vet Res 62:65–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Li Q. 2022. Mechanisms for the invasion and dissemination of Salmonella. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2022:1–12. doi: 10.1155/2022/2655801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Astorga R, Arenas A, Tarradas C, Mozos E, Zafra R, Pérez J. 2004. Outbreak of peracute septicaemic salmonellosis in horses associated with concurrent Salmonella enteritidis and Mucor species infection. Vet Rec 155:240–242. doi: 10.1136/vr.155.8.240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Balducci E, Papi F, Capialbi DE, Del Bino L. 2023. Polysaccharides’ structures and functions in biofilm architecture of antimicrobial-resistant (AMR) pathogens. Int J Mol Sci 24:4030. doi: 10.3390/ijms24044030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Petrin S, Mancin M, Losasso C, Deotto S, Olsen JE, Barco L. 2022. Effect of pH and salinity on the ability of Salmonella serotypes to form biofilm. Front Microbiol 13:821679. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.821679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Dimakopoulou-Papazoglou D, Lianou A, Koutsoumanis KP. 2016. Modelling biofilm formation of Salmonella enterica ser. Newport as a function of pH and water activity. Food Microbiol 53:76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2015.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Steenackers H, Hermans K, Vanderleyden J, De Keersmaecker SCJ. 2012. Salmonella biofilms: an overview on occurrence, structure, regulation and eradication. Food Res Int 45:502–531. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2011.01.038 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Mahadwar G, Chauhan KR, Bhagavathy GV, Murphy C, Smith AD, Bhagwat AA. 2015. Swarm motility of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium is inhibited by compounds from fruit peel extracts. Lett Appl Microbiol 60:334–340. doi: 10.1111/lam.12364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wang Q, Frye JG, McClelland M, Harshey RM. 2004. Gene expression patterns during swarming in Salmonella typhimurium: genes specific to surface growth and putative new motility and pathogenicity genes. Mol Microbiol 52:169–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2003.03977.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Mirold S, Ehrbar K, Weissmüller A, Prager R, Tschäpe H, Rüssmann H, Hardt WD. 2001. Salmonella host cell invasion emerged by acquisition of a mosaic of separate genetic elements, including Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 (SPI1), SPI5, and sopE2. J Bacteriol 183:2348–2358. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.7.2348-2358.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bertelloni F, Tosi G, Massi P, Fiorentini L, Parigi M, Cerri D, Ebani VV. 2017. Some pathogenic characters of paratyphoid Salmonella enterica strains isolated from poultry. Asian Pac J Trop Med 10:1161–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.apjtm.2017.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Bajaj V, Hwang C, Lee CA. 1995. hilA is a novel ompR/toxR family member that activates the expression of Salmonella typhimurium invasion genes. Mol Microbiol 18:715–727. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18040715.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Gong H, Vu G-P, Bai Y, Yang E, Liu F, Lu S. 2010. Differential expression of Salmonella type III secretion system factors InvJ, PrgJ, SipC, SipD, SopA and SopB in cultures and in mice. Microbiology (Reading) 156:116–127. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.032318-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Giacomodonato MN, Uzzau S, Bacciu D, Caccuri R, Sarnacki SH, Rubino S, Cerquetti MC. 2007. SipA, SopA, SopB, SopD and SopE2 effector proteins of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium are synthesized at late stages of infection in mice. Microbiology (Reading) 153:1221–1228. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2006/002758-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Pal S, Dey S, Batabyal K, Banerjee A, Joardar SN, Samanta I, Isore DP. 2017. Characterization of Salmonella gallinarum isolates from backyard poultry by polymerase chain reaction detection of invasion (invA) and Salmonella plasmid virulence (spvC) genes. Vet World 10:814–817. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2017.814-817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Knych HK, Magdesian KG. 2021. Equine antimicrobial therapy: current and past issues facing practitioners. J Vet Pharmacol Ther 44:270–279. doi: 10.1111/jvp.12964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Primeau CA, Bharat A, Janecko N, Carson CA, Mulvey M, Reid-Smith R, McEwen S, McWhirter JE, Parmley EJ. 2023. Integrated surveillance of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Salmonella and Escherichia coli from humans and animal species raised for human consumption in Canada from 2012 to 2017 . Epidemiol Infect 151:e14. doi: 10.1017/S0950268822001509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Srednik ME, Morningstar-Shaw BR, Hicks JA, Tong C, Mackie TA, Schlater LK. 2023. Whole-genome sequencing and phylogenetic analysis capture the emergence of a multi-drug resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Infantis clone from diagnostic animal samples in the United States. Front Microbiol 14:1166908. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1166908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Salipante SJ, Hall BG. 2003. Determining the limits of the evolutionary potential of an antibiotic resistance gene. Mol Biol Evol 20:653–659. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Swarming and swimming motility of Salmonella isolates.

Prevalence of virulence genes by their function category.

Legends for supplemental figures.

Tables S1 to S8.