Abstract

Connector enhancer of Ksr (CNK) is a conserved multidomain protein essential for Ras signaling in Drosophila melanogaster and thought to be involved in Raf kinase activation. However, the precise role of CNK in Ras signaling is not known, and mammalian CNKs are proposed to have distinct functions. Caenorhabditis elegans has a single CNK homologue, cnk-1. Here, we describe the role of cnk-1 in C. elegans Ras signaling and its requirements for LIN-45 Raf activation. We find that cnk-1 positively regulates multiple Ras signaling events during development, but, unlike Drosophila CNK, cnk-1 does not appear to be essential for signaling. cnk-1 mutants appear to be normal but show cell-type-specific genetic interactions with mutations in two other Ras pathway scaffolds/adaptors ksr-1 and sur-8. Genetic epistasis using various activated LIN-45 Raf transgenes shows that CNK-1 promotes LIN-45 Raf activation at a step between the dephosphorylation of inhibitory sites in the regulatory domain and activating phosphorylation in the kinase domain. Our data are consistent with a model in which CNK promotes Raf phosphorylation/activation through membrane localization, oligomerization, or association with an activating kinase.

Keywords: scaffold, vulva, lin-45

Ras signaling through the Raf/mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) kinase cascade is highly conserved and is required repeatedly during development. Aberrant signaling can lead to cancer, and mutations in Ras and B-Raf are commonly found in human tumors (1, 2). The Ras GTPase is a peripheral membrane protein that, when active (GTP bound), recruits the Raf kinase to the membrane, where they can physically interact, resulting in Raf activation (3, 4). In the absence of signal, Raf kinase is held in an inactive state in the cytoplasm. It is known that Raf requires membrane localization, Ras binding, and changes in phosphorylation and oligomerization to become active (3–5). However, it is not known how Ras activation leads to the recruitment of Raf or how Raf phosphorylation and activation occurs.

Genetic screens in Drosophila and Caenorhabditis elegans have identified a number of genes that act genetically between Ras and Raf and may play a role in Raf activation. Drosophila kinase suppressor of Ras (KSR) and C. elegans ksr-1 and ksr-2 encode Raf-related proteins that act as scaffolds for Raf, MEK, and ERK (6–9). KSR constitutively associates with MEK and appears to transiently associate with Raf and ERK upon signaling (10). KSR links Raf to its substrate MEK but could play an additional role in Raf activation (11–14). C. elegans sur-6 encodes a B-regulatory subunit of the protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) holoenzyme, thought to function with KSR (15–17), and sur-8 encodes a leucine-rich repeat protein that binds Ras and may facilitate interactions between Ras and Raf (18–20). KSR is essential for Ras signaling in both C. elegans and Drosophila, whereas SUR-6 and SUR-8 are accessory proteins that facilitate, but are not absolutely essential for, signaling.

Drosophila connector enhancer of Ksr (CNK) acts genetically between Ras and Raf and is required for Raf activation in Drosophila S2 cells (14, 21). cnk-null mutants are cell-lethal, suggesting that CNK is essential for Ras signaling in vivo but precluding a detailed assessment of its requirements (21). Based on its multidomain structure, CNK is proposed to function as an adaptor or scaffold. CNK is membrane-localized, binds Raf, and may promote Raf membrane localization (14, 21). However, Drosophila CNK can promote signaling independently of its Raf interaction domain, and the Raf interaction domain may serve to inhibit Raf activation in the absence of signal (22). Thus, the mechanism by which CNK promotes Raf activity is unclear. Overexpression studies of mammalian CNK1 and CNK2 suggest that CNK may have a more widespread role in signal transduction, including roles in the Rho and Ral GTPase signaling pathways (23–28).

Here, we describe a genetic analysis of the single CNK orthologue in C. elegans. Our studies show that CNK-1 promotes Raf activation at a step before Raf-activation-loop phosphorylation. Surprisingly, CNK-1 is not absolutely needed for Ras signaling but functions as an accessory factor similar to SUR-6 or SUR-8.

Materials and Methods

Molecular Analysis of cnk-1 and Isolation of the cnk-1(sv39) Deletion Allele. The cnk-1 genomic structure was determined by sequencing cDNA clone yk1166a09 and RT-PCR products amplified from a cDNA library by using primers predicted from genomic DNA sequence. Our results differ from the WormBase (www.wormbase.org) prediction for R01H10.8 in several ways: (i) We find no evidence for the predicted exon between our exons 3 and 4, (ii) we identified an extra exon (exon 10), and (iii) we identified an in-frame ATG 15 nucleotide upstream of that predicted by WormBase (see GenBank Accession no. DQ104391). The cnk-1(sv39) allele was isolated by using PCR to screen a deletion library of mutagenized N2 worms, as described in ref. 16, by using PCR primers CRo110/CNK-1.FOR2 (5′-CCA AAC TAG CAT AAT GTT GT-3′) and CRo111/CNK-1.REV.INNRE (5′-CCC AAT CAT CTT CAT CAT CT-3′). The cnk-1(ok836) allele was obtained from the C. elegans Gene Knockout Consortium. sv39 is a 1,983-bp deletion that removes three exons. However, the deleted region was detected by PCR and Southern blot of sv39, suggesting that part of the deleted region is present elsewhere in the genome (data not shown). An in-frame start codon is present downstream of the deletion breakpoint, at the beginning of exon 5. ok836 is a 2,143-bp deletion. PCR using primers internal to the deletions was used to confirm that the deleted region was, indeed, absent in the ok836 strain. RT-PCR analysis indicated that ok836 produces an mRNA that preserves the ORF. Both cnk-1 deletion alleles were outcrossed a minimum of six times against the wild-type N2 Bristol strain before analysis.

Genetics, Phenotype Analysis, and RNA Interference (RNAi). General methods for the handling and culturing of C. elegans were as described in ref. 29. Experiments were performed at 20°C, unless otherwise noted. Vulval, lethal, and 2 P11.p phenotypes were scored, as described in ref. 30. Multivulva (Muv) phenotypes were scored in L4 larvae by differential interference contrast optics. Animals with >3 vulval precursor cells (VPCs) induced were scored as Muv. RNAi was performed as described in ref. 31. Double-stranded RNA was prepared by in vitro transcription with T7 and T3 polymerases by using a PCR-derived cnk-1 genomic template with primers oMS89 (5′-AAT TAA CCC TCA CTA AAG GGA TGG GAT TTC CGT CGA C-3′) and oMS90 (5′-GTA ATA CGA CTC ACT ATA GGG CCT AAC AAT TTG ACT-3′).

Generation of Transgenic Animals. Extrachromosomal array csEx63 was used as a source of hsp16–41-torso4021-Draf (Drosophila Raf) (G. Kao and M.S., unpublished data) and behaves identically to csEx64 (16). hsp16–41-lin-45ED plasmid pCR33.1 was generated by cloning a PCR product amplified from plasmid lin-45ED (32) with primers CRo181 (5′-TTC ATG GCT AGC ACC ATG AGT CGG ATT AAT TTC AAA AAG TC-3′) and CRo182 (5′-TTC ATG CCA TGG CTA AAT GAG ACC ATA GAC ATT G-3′) into the NheI and NcoI sites of heat-shock vector pPD49.83. pCR33.1 was injected into N2 animals at 20 ng/μl with pTG_96 (sur-5::gfp) (33) at 30 ng/μl and pBluescript at 50 ng/μl to yield transgenic strain csEx72.

Results

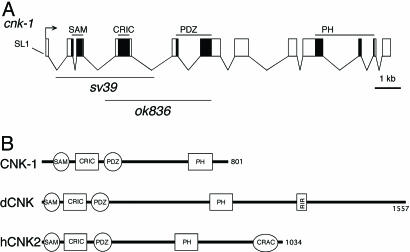

C. elegans has a single CNK orthologue, cnk-1 (Fig. 1). We determined the coding sequence of cnk-1, predicted gene R01H10.8, and found that it differs from the WormBase prediction (see Materials and Methods). cnk-1 is predicted to encode an 801-aa protein containing sterile alpha motif (SAM), a conserved region in Cnk (CRIC), PSD-90/Dlg/ZO-1 (PDZ), and Pleckstrin homology (PH) domains shared among other members of the CNK family of proteins. CNK-1 does not appear to have a Raf inhibitory region (RIR) domain specific to Drosophila, and we cannot detect direct physical interactions between CNK-1 and LIN-45 RAF in the yeast two-hybrid system (data not shown). CNK-1 also lacks a conserved-region-among-chordate (CRAC) domain specific to mammalian CNK proteins (22).

Fig. 1.

Structure of the cnk-1 gene and domains of the CNK-1 protein. (A) cnk-1 genomic structure and location of deletion mutations. The exons are depicted as boxes and the introns as connecting lines. The black boxes depict regions encoding the sterile alpha motif (SAM), conserved region in Cnk (CRIC), PSD-90/Dlg/ZO-1 (PDZ), and Pleckstrin homology (PH) protein domains. The sv39 and ok836 deletions are represented as a line below the genomic structure (see Materials and Methods). (B) Schematic representation of CNK-1, Drosophila CNK, and human CNK2A proteins. RIR, Raf inhibitory region; CRAC, conserved region among chordates. CNK2A is the most closely related of the three mammalian CNK proteins to CNK-1 and also the only one so far implicated in Ras/Raf signaling (24, 26).

To determine whether cnk-1 is required for Ras signaling, we screened a C. elegans deletion library by PCR and isolated a single deletion allele sv39. In addition, we obtained a second deletion allele ok836 from the C. elegans Gene Knockout Consortium. Both deletions remove the most highly conserved regions of cnk-1, including the CRIC domain that has been shown to be essential for CNK function in Drosophila (21) (Fig. 1).

In C. elegans, Ras signaling is required for a number of developmental processes, including specification of vulval cell fates, the excretory duct cell, and the P12 cell (34). During vulval development, Ras signaling is required to induce three of six VPCs to undergo three rounds of division to produce the 22 cells that will form the vulva. Loss-of-function mutations in the Ras pathway result in a failure of the VPCs to be induced, causing a vulvaless (Vul) phenotype. Ras signaling is required in the excretory duct cell for viability (35). Loss-of-function mutations in the Ras pathway cause a loss of the excretory duct cell fate, resulting in animals filling with fluid and dying in the first larval stage with a distinct “rod-like” appearance. Ras signaling is required for the P12 blast cell fate. Loss-of-function mutations in the Ras pathway cause P12 to adopt a fate similar to its neighbor P11, resulting in a loss of the P12.pa cell and duplication of P11.p. Animals homozygous for either cnk-1 deletion allele appear to be essentially wild-type and display little or no discernible Ras phenotypes (Fig. 2 A, C, and E and Table 1). We believe that both cnk-1 deletions are strong loss-of-function alleles. Although they could potentially produce partial protein products (see Materials and Methods), each would lack multiple conserved domains (Fig. 1). Furthermore, cnk-1(RNAi) is similar to, and no more severe than, either deletion allele, and we find no phenotype enhancement when sv39 is placed in trans to a deficiency that removes cnk-1, and cnk-1 is a recessive modifier of other Ras pathway mutants (Table 1 and see below). Thus, cnk-1 does not appear to be essential for Ras signaling in C. elegans.

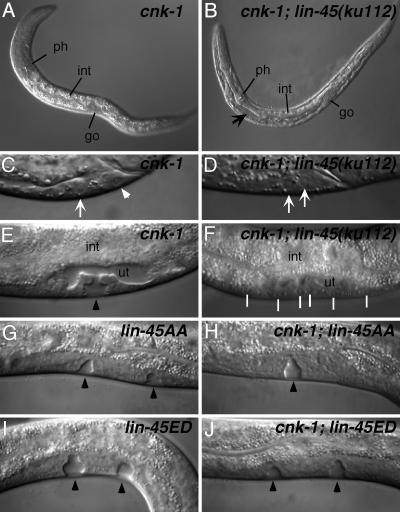

Fig. 2.

cnk-1 phenotypes in lin-45 raf mutant backgrounds. cnk-1(sv39) (A, C, and E) and lin-45(ku112) (30) mutants appear to be phenotypically normal, but cnk-1(sv39); lin-45(ku112) double mutants (B, D, and F) display strong Ras-like phenotypes. Differential interference contrast images of normal L1 larva (A) (ph, pharynx; int, intestine; go, gonad), rod-like lethal larva (B) (arrow marks fluid accumulation, which compresses the internal organs), normal P11.p (arrow), and P12.pa (arrowhead) cells (C), 2 P11.p (arrows) cells (D), normal L4 vulva (black arrowhead) (E), and vulvaless animal (F) (white lines mark uninduced cells). ut, uterus. cnk-1(ok836) suppresses hs-lin-45AA (G and H) but not hs-lin-45ED (I and J) Muv defects.

Table 1. cnk-1 displays synthetic phenotypes with lin-45, ksr-1, and sur-8.

| Genotype | Vul, % | Average no. of VPCs induced, (n) | Rod-like lethal, % (n) | 2 P11.p, % (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cnk-1 (RNAi) | 0 | 3.0 (100) | 0 (> 1,000) | 0 (100) |

| cnk-1 (sv39) | 0 | 3.02 (45)* | 0 (494) | 2 (45) |

| cnk-1 (ok836) | 0 | 3.00 (35) | 0 (554) | 0 (39) |

| cnk-1 (sv39)/nDf40† | 0 | 3.00 (18) | 0 (486) | 0 (18) |

| lin-45 (ku112) | 4 | 2.98 (24) | <1 (452) | 0 (21) |

| cnk-1 (RNAi); lin-45 (ku112) | 3 | 2.98 (61) | 39 (1,413)‡ | 19 (62) |

| cnk-1 (sv39); lin-45 (ku112) | 59‡ | 1.59 (58) | 74 (712)‡ | 47 (59)‡ |

| cnk-1 (sv39); lin-45 (ku112)† 25°C | 25 | 2.56 (16) | ND | 6 (16) |

| cnk-1 (sv39)/nDf40; lin-45 (ku112)† 25°C | 21 | 2.47 (43) | ND | 8 (36) |

| cnk-1 (ok836); lin-45 (ku112) | 33§ | 2.49 (66) | 89 (984)‡ | 24 (64)§ |

| ksr-1 (n2526) | 0 | 3.00 (26) | 1 (180) | 0 (24) |

| cnk-1 (RNAi); ksr-1 (n2526) | 0 | 3.00 (71) | 63 (1,146)‡ | 0 (71) |

| cnk-1 (sv39); ksr-1 (n2526) | 0 | 3.00 (12) | 95 (491)‡ | 6 (16) |

| cnk-1 (sv39)/+; ksr-1 (n2526)¶ | ND | ND | 3 (311) | ND |

| cnk-1 (ok836); ksr-1 (n2526) | 0 | 3.00 (28) | 98 (372)‡ | 4 (28) |

| sur-6(cs24) | 2|| | 2.97 (40)|| | 0 (195)|| | 0 (21)|| |

| sur-6(cs24); cnk-1 (sv39) | 10 | 2.95 (20) | 0 (110) | 0 (20) |

| sur-8(ku167) | 0 | 3.00 (25) | 0 (328) | 0 (24) |

| cnk-1 (RNAi); sur-8(ku167) | 9 | 2.91 (69) | 0 (942) | 1 (69) |

| cnk-1 (sv39); sur-8(ku167) | 28§ | 2.60 (25) | 0 (343) | 0 (25) |

| cnk-1 (ok836); sur-8(ku167) | 14 | 2.93 (22) | 3 (292)§ | 17 (23)§ |

Statistical analysis was performed by using Fisher's exact test (GraphPad). Statistical comparisons are made with the top genotype of each section. lin-45 (ku112) is a weak hypomorphic allele and is somewhat cold-sensitive (30), ksr-1 (n2526) is a putative null allele (6), sur-8(ku167) is a strong hypomorphic allele (18), and sur-6(cs-24) is a hypomorphic allele (17). n, number of animals scored. ND, no data.

1 animal had a shifted vulva resulting in >3 VPCs being induced

cnk-1 (sv39) is linked to unc-119(e2498) and deficiency nDf40 is linked to dpy-18(e364); described in ref. 48 and www.wormbase.org. lin-45 (ku112) is linked to dpy-20(e1282). Experiments with nDf40 in the lin-45 (ku112) background (and non-Df sibling controls) were performed at 25°C as indicated

P < 0.001

P < 0.05

Progeny from cnk-1 (sv39); ksr-1(n2526) hermaphrodites mated with cnk-1(+): ksr-1 (n2526) males

Several previously described positive regulators of C. elegans Ras signaling, such as ksr-1, sur-6, and sur-8 have little or no Ras mutant phenotypes alone, but display strong Ras phenotypes in a genetically sensitized background (6, 7, 17, 18). For example, some hypomorphic alleles of lin-45 raf do not display overt Ras phenotypes but are strongly enhanced by the removal of ksr-1 or sur-6 (7, 17, 30). We find that both cnk-1 alleles strongly synergize with the hypomorphic allele lin-45(ku112). cnk-1; lin-45(ku112) animals display strong Ras phenotypes, including rod-like larval lethality, Vul, and 2 P11.p cell phenotypes (Fig. 2 B, D, and F and Table 1). Therefore, cnk-1 is a positive regulator of Ras signaling similar to ksr-1, sur-6, and sur-8.

We tested for genetic interactions between cnk-1 and sur-6 PP2A-B and the scaffolds/adaptors ksr-1, ksr-2, and sur-8. cnk-1 deletions show strong synergistic phenotypes with both ksr-1 and sur-8 but not ksr-2 or sur-6 (Table 1 and data not shown). Interestingly, the cnk-1; ksr-1 doubles have a very highly penetrant rod-like larval lethal phenotype, but escapers have normal P12 and vulval fates. In contrast, cnk-1; sur-8 animals display mild Vul and 2 P11.p phenotypes but little or no rod-like lethality. Thus there appear to be different requirements for these scaffolds/adaptors in different tissues.

During vulval development, only three of six VPCs are induced to make vulval tissue, but when Ras signaling is inappropriately activated in the VPCs, >3 VPCs can be induced, resulting in a Muv phenotype (34). To determine where in the Ras pathway cnk-1 functions, we performed genetic epistasis, testing the ability of the cnk-1 deletions to suppress the Muv phenotype of different activated components of the Ras pathway. A gain-of-function allele of let-60 ras analogous to the oncogenic form of human Ras G13E induces a Muv phenotype (36, 37). We find that cnk-1 significantly suppresses the Muv phenotype of let-60 ras gain-of-function, suggesting that cnk-1 is required downstream of let-60 ras (Table 2). To determine where cnk-1 acts with respect to Raf, we tested the ability of cnk-1 to suppress the Muv phenotype caused by an activated DRaf chimera, Torso4021-DRaf. A transgene expressing activated torso4021-Draf under the control of the heat-shock promoter hsp16–41 induces a Muv phenotype (18). cnk-1 fails to suppress the Muv phenotype of hs-torso4021-Draf, consistent with cnk-1 acting upstream or in parallel to Raf (Table 2). An integrated transgene, gaIs36, expressing both an activated version of Drosophila MEK and C. elegans mpk-1 ERK induces a potent Muv phenotype when grown at 25° (38). cnk-1 fails to strongly suppress the Muv phenotype of gaIs36 (Table 2). lin-1 encodes an ETS domain protein that acts downstream of the pathway to negatively regulate vulval induction (39). We find that neither cnk-1 allele can suppress the Muv phenotype of a lin-1 loss-of-function mutant (Table 2). These data are consistent with CNK epistasis in Drosophila and place cnk-1 genetically between Ras and Raf.

Table 2. Epistasis with Muv strains.

| Genotype | Muv, % | Average no. of VPCs induced, (n) |

|---|---|---|

| let-60(n1046gf) | 56 | 3.48 (27) |

| cnk-1 (sv39); let-60(n1046gf) | 0* | 3.00 (33) |

| cnk-1 (ok836)/hT2; let-60(n1046gf) | 67 | 3.56 (24) |

| cnk-1 (ok836); let-60(n1046gf) | 16* | 3.11 (32) |

| hs-torso4021-Draf | 13 | 3.13 (106) |

| cnk-1 (sv39); hs-torso4021-Draf | 31† | 3.38 (45) |

| cnk-1 (ok836); hs-torso4021-Draf | 21 | 3.19 (39) |

| gals36 | 87 | 5.02 (46) |

| cnk-1 (sv39); gals36 | 95 | 5.10 (19) |

| cnk-1 (ok836); gals36 | 61† | 4.40 (36) |

| lin-45 (sy96); gals36 | 75 | 3.40 (12) |

| lin-1 (n304) | 100 | 5.53 (17) |

| cnk-1 (ok836); lin-1 (n304) | 100 | 5.78 (16) |

Statistical analysis is the same as that described in Table 1. For epistasis with cnk-1(sv39), csEx63 (hsp16-41-torso4021-Draf) larvae were heat-shocked at 38.5°C for 45 min, 48–50 h after egg-lay. For epistasis with cnk-1(ok836), csEx63 larvae were heat-shocked 30–34 h after plating synchronized L1 larvae. The integrated transgene gals36 (E1F-D-mek, hs-mpk-1) was linked to him-5(e1490) (38, 48). gals36-bearing animals were shifted from 20°C to 25°C, and progeny were scored for the Muv phenotype. gals36 may be sensitive to mutations upstream in the pathway because it is mildly suppressed by cnk-1(ok836) and lin-45(sy96). let-60(n1046) is a gain-of-function allele (36, 37), line-I(n304) is null allele (39), line-45(sy96) is a strong hypomorphic allele (49), and hT2[qls48] (50) balances the cnk-1 locus. n, number of animals scored

P < 0.001

P < 0.05

Raf kinase activation is a complex multistep process requiring relief of autoinhibition by the Raf N terminus and changes in phosphorylation, membrane localization, Ras binding, and oligomerization (3–5). The Torso4021-DRaf chimera typically used for epistasis experiments in both Drosophila and C. elegans likely bypasses most of these steps (40, 41). This chimera consists of the extracellular and membrane-spanning domains of a constitutively dimerizing Torso receptor tyrosine kinase fused to a truncated DRaf missing the N-terminal Ras binding domain. The remaining C-terminal portion of Draf (containing the kinase domain) may escape autoinhibition and is predicted to be constitutively membrane-localized and oligomerized. Torso4021-Draf can signal independently of the SUR-6 PP2A subunit and the SUR-8, KSR-1, and CNK-1 scaffolds (8, 17, 18, 21).

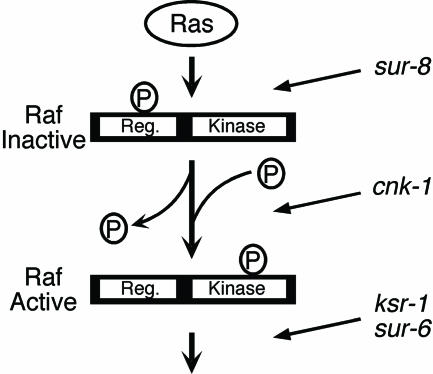

To better understand the proposed role of CNK in Raf activation, we used two more specific forms of activated C. elegans LIN-45 Raf. The first form, LIN-45(AA), lacks inhibitory phosphorylation sites in the N-terminal regulatory domain (32) (Fig. 3). The analogous residues in mammalian Raf proteins serve as docking sites for the 14-3-3 chaperone, which inhibits translocation of Raf to the membrane (42). Dephosphorylation of these inhibitory sites by PP2A is thought to be an early step in Raf activation (43). The second form of activated LIN-45 Raf, LIN-45(ED), contains negatively charged residues that mimic activating phosphorylation within the activation loop of the kinase domain (32) (Fig. 3). Phosphorylation of these activating sites by an unknown, membrane-localized kinase is thought to be a late step in Raf activation (43). Both LIN-45(AA) and LIN-45(ED) mutants can induce a Muv phenotype, when expressed as a transgene (32). We tested whether cnk-1 mutants could suppress the Muv phenotype of these differentially activated LIN-45 Raf constructs.

Fig. 3.

Genetic epistasis data indicate that cnk-1 promotes Ras signaling at a step of Raf activation after dephosphorylation of inhibitory sites in the regulatory domain (Reg.) and before activating phosphorylation in the kinase domain. This placement is distinct from sur-8, which is required upstream of the dephosphorylation event (45) and ksr-1 and sur-6, which are required downstream of activating phosphorylation in the kinase domain. ksr-1 and sur-6 could also have additional, upstream requirements. Circled P, phosphate group.

Whereas cnk-1 deletions were unable to suppress the Muv phenotype of hs-torso4021-Draf, both deletions readily suppress the Muv phenotype of hs-lin-45AA (Fig. 2 G and H and Table 3). This finding suggests that either CNK-1 is required downstream of LIN-45 Raf AA or, alternatively, that LIN-45 AA activity depends on upstream signaling components. We do not believe that LIN-45 AA depends on upstream signal, because a strong mutation in the let-23 receptor and a dominant-negative allele of let-60 ras (which are 85% and 100% Vul, respectively) fail to suppress the Muv phenotype of hs-lin-45AA (Table 3). Because LIN-45AA still requires CNK-1 to elicit a Muv phenotype, it is unlikely that CNK-1 plays a role in dephosphorylation of the Raf regulatory domain.

Table 3. Epistasis with lin-45 gain-of-function strains.

| Genotype | Muv, % (n) | Average no. of VPCs induced, (n) |

|---|---|---|

| hs-lin-45AA | 91 (32) | 4.75 (32) |

| cnk-1 (ok836); hs-lin-45AA | 38 (34)* | 3.40 (34) |

| hs-lin-45AA | 50 (26) | 3.81 (26) |

| cnk-1 (sv39); hs-lin-45AA | 0 (30)* | 3.00 (30) |

| hs-lin-45AA | 76 (45) | 4.68 (25) |

| let-23 (sy1); hs-lin-45AA | 83 (47) | 4.08 (25) |

| let-23 (sy1) | 0 (27)† | 0.80 (27) |

| dpy-20; hs-lin-45AA | 88 (17) | 4.62 (17) |

| let-60(sy94) / dpy-20; hs-lin-45AA | 95 (19) | 5.42 (19) |

| let-60(sy94) / dpy-20 | 0 (14)† | 0.04 (14) |

| hs-lin-45ED | 37 (30) | 3.37 (30) |

| cnk-1 (ok836); hs-lin-45ED | 48 (29) | 3.84 (29) |

| sur-6(cs24); hs-lin-45ED | 0 (28)* | 3.00 (28) |

| ksr-1 (n2526); hs-lin-45ED | 3 (29)‡ | 3.02 (29) |

Statictical analysis is the same as that described in Table 1. Extrachromosomal array csEx52 was used as a source of hsp16-41-lin-45AA (16). For epistasis with cnk-1(sv39), csEx52 larvae were heat-shocked at 37°C for 45 min 40.5–43.5 h after egg-lay. For others, csEx52 larvae were heat-shocked at 39°C for 45 min 28 h (30 with let-23) after plating synchronized L1 larvae. csEx72 (hsp16-41-lin-45ED) larvae were heat-shocked at 38.5°C for 45 min 31 h after plating synchronized L1 larvae. let-23(syl) is a strong hypomorphic allele, let-60(sy94) is a dominant negative allele, and dpy-20(e1282) was used to balance let-60 (48, 51). n, number of animals scored.

P < 0.001

Animals are Vul (see text)

P < 0.05

LIN-45 ED replaces activating phosphorylation sites Thr 626 and Thr 629 with glutamic acid and aspartic acid, respectively, to mimic constitutive phosphorylation. LIN-45 ED likely functions analogously to the most common oncogenic B-Raf mutation V599E, which would correspond to Val 627 in LIN-45 Raf (2, 44). We find that the cnk-1 deletions cannot suppress the Muv phenotype of hs-lin-45ED (Fig. 2 I and J and Table 3). Thus, CNK-1 is not required after activating phosphorylation in the kinase domain. Together, these data suggest that CNK-1 promotes the activation of LIN-45 Raf after dephosphorylation of the inhibitory sites in the regulatory domain and before activating phosphorylation in the kinase domain (Fig. 3). For example, CNK-1 could promote Raf membrane translocation, oligomerization, or association with the activating kinase.

LIN-45 AA has been used for epistasis analysis with ksr-1, sur-6, and sur-8 (16, 45). Like cnk-1, ksr-1 and sur-6 mutations strongly suppress the Muv phenotype of hs-lin-45AA; however, a sur-8 mutant is unable to suppress LIN-45 AA. Thus, cnk-1, ksr-1, and sur-6 function at a distinct step of the pathway from sur-8. We tested whether ksr-1 and sur-6 can suppress the Muv phenotype of LIN-45 ED. Whereas cnk-1 mutations cannot suppress the Muv phenotype of LIN-45 ED, both ksr-1 and sur-6 can suppress LIN-45 ED (Table 3). These data are consistent with the model in which KSR-1 and SUR-6 promote the ability of active Raf to access its substrate MEK but cannot exclude the possibility that these gene products have additional, earlier functions. Overall, our data suggest that CNK-1 and SUR-8 promote distinct steps of Raf activation and are not required for a later, KSR-1- and SUR-6-dependent step of signaling (Fig. 3).

Discussion

We have shown that C. elegans cnk-1 promotes Ras signaling in several different tissues during development. However, C. elegans cnk-1 does not appear to be an essential component of the Ras pathway. Our findings differ from those in Drosophila, where cnk appears to be essential for Ras signaling (14, 21). Because there is only one CNK gene in C. elegans, this difference may be due to redundancy with a nonhomologous protein or reflect a difference in how Raf is activated in C. elegans versus Drosophila. Alternatively, the lethality of cnk-null cells may be masking significant nonrequirements for cnk in Drosophila. Knockouts of the three mammalian CNK genes have not yet been described and whether their requirements will resemble those of Drosophila or C. elegans remains to be determined.

In Drosophila, CNK has both positive and negative regulatory roles in Ras signaling (22). Our genetic studies indicate that the primary role of C. elegans CNK-1 is to positively regulate Ras signaling. However, a potential negative role of CNK-1 is suggested by the observation that cnk-1 mutations somewhat enhance the Torso4021-DRaf Muv phenotype (Table 2). If CNK-1 were to play both positive and negative roles in Ras signaling, that dual function might help explain the mild phenotype caused by cnk-1 mutations.

We find no evidence to suggest that C. elegans cnk-1 functions outside of Ras signaling. In particular, we do not observe embryonic-lethality or cell-migration defects indicative of defects in rho-1 signaling (46, 47). It is possible that alternative roles for cnk-1 may be detectable only in the right genetically sensitized background. Notably, however, both Drosophila and C. elegans CNK proteins are most similar to mammalian CNK2, which has been found to affect Ras signaling (24, 26) and less similar to mammalian CNK1, which has been found to affect Rho signaling (25, 27, 28). It is possible that the multiple mammalian CNK proteins have evolved to serve different GTPase signaling pathways.

Interestingly, cnk-1 shows cell-type-specific genetic interactions with ksr-1 and sur-8. These genetic interactions may reflect differences in how signals are transmitted in different cell types and suggest that contributions of different scaffolds and adaptors might be one mechanism by which signaling specificity is achieved. The cnk-1 epistasis analysis with LIN-45 Raf AA and LIN-45 Raf ED shows that the role of cnk-1 is distinct from that of ksr-1, sur-6, and sur-8 and further narrows down the possible mechanisms by which CNK functions to regulate Raf activation. Our data argue against a role for CNK in Raf regulatory domain dephosphorylation but are consistent with models in which CNK promotes Raf membrane localization, oligomerization, or association with an activating kinase.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yelena Bernstein for technical assistance; K. Guan (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor), A. Fire (Stanford University, Stanford, CA), P. Okkema (University of Illinois, Chicago), and Y. Kohara (National Institute of Genetics, Shizuoka, Japan) for reagents; and G. Kao (Umeå University), the C. elegans Gene Knockout Consortium, and the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center for strains. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants GM58540 and CA87512 (to M.V.S.), grants from Cancerfonden and the Wallenberg Foundation (to S.T.), and a Developmental Biology Training grant (to C.E.R.). C.E.R. was a postdoctoral fellow of the Jane Coffin-Childs Memorial Fund for Medical Research.

Author contributions: C.E.R. and M.V.S. designed research; C.E.R. and M.V.S. performed research; A.R. and S.T. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; C.E.R. and M.V.S. analyzed data; and C.E.R. and M.V.S. wrote the paper.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: CNK, connector enhancer of KSR; DRaf, Drosophila Raf; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; KSR, kinase suppressor of Ras; MEK, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase; Muv, multivulva; RNAi, RNA interference; VPC, vulval precursor cell; Vul, vulvaless.

Data Deposition: The sequence reported in this paper has been deposited in the GenBank database (accession no. DQ104391).

References

- 1.Bos, J. L. (1989) Cancer Res. 49, 4682-4689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davies, H., Bignell, G. R., Cox, C., Stephens, P., Edkins, S., Clegg, S., Teague, J., Woffendin, H., Garnett, M. J., Bottomley, W., et al. (2002) Nature 417, 949-954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chong, H., Vikis, H. G. & Guan, K. L. (2003) Cell. Signalling 15, 463-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dhillon, A. S. & Kolch, W. (2002) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 404, 3-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morrison, D. K. & Cutler, R. E. (1997) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 9, 174-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kornfeld, K., Hom, D. B. & Horvitz, H. R. (1995) Cell 83, 903-913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sundaram, M. & Han, M. (1995) Cell 83, 889-901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Therrien, M., Chang, H. C., Solomon, N. M., Karim, F. D., Wassarman, D. A. & Rubin, G. M. (1995) Cell 83, 879-888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohmachi, M., Rocheleau, C. E., Church, D., Lambie, E., Schedl, T. & Sundaram, M. V. (2002) Curr. Biol. 12, 427-433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morrison, D. K. (2001) J. Cell Sci. 114, 1609-1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Michaud, N. R., Therrien, M., Cacace, A., Edsall, L. C., Spiegel, S., Rubin, G. M. & Morrison, D. K. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 12792-12796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang, Y., Yao, B., Delikat, S., Bayoumy, S., Lin, X. H., Basu, S., McGinley, M., Chan-Hui, P. Y., Lichenstein, H. & Kolesnick, R. (1997) Cell 89, 63-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roy, F., Laberge, G., Douziech, M., Ferland-McCollough, D. & Therrien, M. (2002) Genes Dev. 16, 427-438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anselmo, A. N., Bumeister, R., Thomas, J. M. & White, M. A. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 5940-5943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ory, S., Zhou, M., Conrads, T. P., Veenstra, T. D. & Morrison, D. K. (2003) Curr. Biol. 13, 1356-1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kao, G., Tuck, S., Baillie, D. & Sundaram, M. V. (2004) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 131, 755-765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sieburth, D. S., Sundaram, M., Howard, R. M. & Han, M. (1999) Genes Dev. 13, 2562-2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sieburth, D. S., Sun, Q. & Han, M. (1998) Cell 94, 119-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li, W., Han, M. & Guan, K. L. (2000) Genes Dev. 14, 895-900. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Selfors, L. M., Schutzman, J. L., Borland, C. Z. & Stern, M. J. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 6903-6908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Therrien, M., Wong, A. M. & Rubin, G. M. (1998) Cell 95, 343-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Douziech, M., Roy, F., Laberge, G., Lefrancois, M., Armengod, A. V. & Therrien, M. (2003) EMBO J. 22, 5068-5078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rabizadeh, S., Xavier, R. J., Ishiguro, K., Bernabeortiz, J., Lopez-Ilasaca, M., Khokhlatchev, A., Mollahan, P., Pfeifer, G. P., Avruch, J. & Seed, B. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 29247-29254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bumeister, R., Rosse, C., Anselmo, A., Camonis, J. & White, M. A. (2004) Curr. Biol. 14, 439-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lopez-Ilasaca, M. A., Bernabe-Ortiz, J. C., Na, S. Y., Dzau, V. J. & Xavier, R. J. (2005) FEBS Lett. 579, 648-654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lanigan, T. M., Liu, A., Huang, Y. Z., Mei, L., Margolis, B. & Guan, K. L. (2003) FASEB J. 17, 2048-2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jaffe, A. B., Aspenstrom, P. & Hall, A. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 1736-1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jaffe, A. B., Hall, A. & Schmidt, A. (2005) Curr. Biol. 15, 405-412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brenner, S. (1974) Genetics 77, 71-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rocheleau, C. E., Howard, R. M., Goldman, A. P., Volk, M. L., Girard, L. J. & Sundaram, M. V. (2002) Genetics 161, 121-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fire, A., Xu, S., Montgomery, M. K., Kostas, S. A., Driver, S. E. & Mello, C. C. (1998) Nature 391, 806-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chong, H., Lee, J. & Guan, K. L. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 3716-3727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yochem, J., Gu, T. & Han, M. (1998) Genetics 149, 1323-1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sternberg, P. W. & Han, M. (1998) Trends Genet. 14, 466-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yochem, J., Sundaram, M. & Han, M. (1997) Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 2716-2722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beitel, G. J., Clark, S. G. & Horvitz, H. R. (1990) Nature 348, 503-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Han, M. & Sternberg, P. W. (1990) Cell 63, 921-931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lackner, M. R. & Kim, S. K. (1998) Genetics 150, 103-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beitel, G. J., Tuck, S., Greenwald, I. & Horvitz, H. R. (1995) Genes Dev. 9, 3149-3162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dickson, B., Sprenger, F., Morrison, D. & Hafen, E. (1992) Nature 360, 600-603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baek, K. H., Fabian, J. R., Sprenger, F., Morrison, D. K. & Ambrosio, L. (1996) Dev. Biol. 175, 191-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jaumot, M. & Hancock, J. F. (2001) Oncogene 20, 3949-3958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chong, H. & Guan, K. L. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 36269-36276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wan, P. T., Garnett, M. J., Roe, S. M., Lee, S., Niculescu-Duvaz, D., Good, V. M., Jones, C. M., Marshall, C. J., Springer, C. J., Barford, D. & Marais, R. (2004) Cell 116, 855-867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoder, J. H., Chong, H., Guan, K. L. & Han, M. (2003) EMBO J. 23, 111-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spencer, A. G., Orita, S., Malone, C. J. & Han, M. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 13132-13137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jantsch-Plunger, V., Gonczy, P., Romano, A., Schnabel, H., Hamill, D., Schnabel, R., Hyman, A. A. & Glotzer, M. (2000) J. Cell. Biol. 149, 1391-1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Riddle, D. L., Blumenthal, T., Meyer, B. J. & Priess, J. R. (1997) C. elegans II (Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY), pp. 902-1047.

- 49.Han, M., Golden, A., Han, Y. & Sternberg, P. W. (1993) Nature 363, 133-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang, S. & Kimble, J. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 1363-1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Han, M. & Sternberg, P. W. (1991) Genes Dev. 5, 2188-2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]