Abstract

Bone-marrow-derived cells can contribute nuclei to skeletal muscle fibers. However, serial sectioning of muscle in mdx mice implanted with GFP-labeled bone marrow reveals that only 20% of the donor nuclei chronically incorporated in muscle fibers show dystrophin (or GFP) expression, which is still higher than the expected frequency of “revertant” fibers, but there is no overall increase above controls over time. Obviously, the vast majority of incorporated nuclei either never or only temporarily turn on myogenic genes; also, incorporated nuclei eventually loose the activation of the β-actin::GFP transgene. Consequently, we attempted to enhance the expression of dystrophin. In vivo application of the chromatin-modifying agents 5-azadeoxycytidine and phenylbutyrate as well as local damage by cardiotoxin injections caused a small increase in dystrophin-positive fibers without abolishing the appearance of “silent” nuclei. The results thus confirm that endogenous repair processes and epigenetic modifications on a small-scale lead to dystrophin expression from donor nuclei. Both effects, however, remain below functionally significant levels.

Keywords: bone marrow transplantation, dystrophin, chromatin-modifying agents

Bone-marrow-derived blood cells have repeatedly been shown to incorporate into the myogenic compartment (1–6). Muscle regeneration from blood-borne cells would bear considerable therapeutic potential in genetically determined muscle diseases like Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD). It has been shown previously that myogenic precursor cells directly injected into muscles form new muscle fibers that become innervated and contribute to contractile tension (7, 8). Such cell-based interventions allow complete replacement of single muscles (8) or new muscle formation, even in ectopic sites like the s.c. compartment (9). In contrast, systemic application of wild-type or genetically engineered muscle-derived cells has led to seeding of only marginal numbers of donor cells (5, 10, 11). Local application of bone-marrow-derived cells to damaged muscle tissue has been much less effective and the contribution of circulating blood cells has been little (4, 5, 12, 13). Commonly, during the study of these phenomena, transfer of the GFP transgene to muscle fibers (and other cells) has been used as a marker without consistently looking into donor-specific proteins (14, 15). Obviously, the sole appearance of GFP in adult muscle fibers does not also prove that the myogenic transcription program has been turned on. In that case, the incorporated donor nuclei ought to provide the intact dystrophin transcript to the muscle fiber. In muscle of mdx mice, this question cannot readily be answered because spontaneous development of dystrophin-carrying fibers, the “revertant fibers,” takes place, and there has been evidence for an increase with age (refs. 14 and 15 and this paper). Nevertheless, donor nuclei found in dystrophin-positive parts of muscle fibers were taken as sufficient evidence for a causal relation, but no significant “repair” with strong increase in dystrophin-carrying fibers above the level of the revertant fibers has ever been described (12, 16). Our finding that most incorporated nuclei do not acquire transcription of the myogenic program offers an explanation of this discrepancy.

Materials and Methods

Irradiation. Newborn dystrophin-mutant mdx mice (aged 1–7 days) were sublethally irradiated with 3.5 or 5 Gy with an x-ray device (MG 420, Philips). A voltage of 200 kV and a current of 140 mA with a 0.5-mm Cu filter were chosen. The beam had a conical shape with a final diameter of 16 cm at the source-skin-distance plane of 35 cm. The beam divergence is ≈13°. The area for the localizations of the mice is 200 cm2. This size assures without sedation a simultaneous and homogeneous irradiation of newborn mice in vivo in their standard cage. The overall accuracy of the delivery of an energy dose of 5 Gy was >10%, including an uncertainty of the chosen voltage and current. The irradiation took 3 min and 33 s and had a dose rate of 1.41 Gy/min.

Implantation. Whole bone marrow was harvested from 1- to 6-month-old normal or transgenic male mice constitutively expressing the enhanced GFP under the control of the β-actin promoter (The Jackson Laboratory) (17). Bone marrow cells were flushed from the femur and tibia with Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (GIBCO) supplemented with a 10% FCS/1% penicillin–streptomycin solution (100 units and 0.1 mg/ml, respectively; PAA, Linz, Austria). The cells were dissociated with a 26-gauge needle and washed in Hanks' balanced salt solution (GIBCO), and a single-cell suspension was obtained by filtration through a 30-μm separation filter (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). After centrifugation at 250 × g at 4°C for 10 min, the pellet was finally resuspended in Hanks' balanced salt solution such that a volume of 50–80 μl per animal could be injected. Approximately 5 h after irradiation, newborn mdx mice were injected i.p. with 2 × 106 to 15 × 106 nucleated GFP cells from male whole bone marrow. Hematopoietic reconstitution was evaluated in peripheral blood and bone marrow by FACS (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) at the time point that mice were killed.

Drug Applications. Untreated, control mdx mice and irradiated and implanted mdx mice were treated with 4 g/liter (low dose) or 8 g/liter (high dose) 4-phenylbutyrate, pH 7.3 (Sigma–Aldrich), supplied orally with sterile water ad libitum starting from 6–7 weeks of age for a period of 6 weeks. Three weeks after the onset of phenylbutyrate treatment, mice received i.p. injections of 5-aza-2-deoxycytidine at 0.5 μg per g of body weight (low dose) or 1 μg per g of body weight (high dose) for 3 days per week (Monday, Wednesday, and Friday) for 3 weeks. A reversible drop in body weight developed during the third week of 5-aza-2-deoxycytidine treatment in some animals. Muscles were removed 2–4 days after the last i.p. injection. Right tibialis anterior (TA) muscles of normal control mdx mice and irradiated and implanted mdx mice were injected with 20 μl of cardiotoxin [1 μg/μl Naja mossambica (Sigma)] at 9 weeks of age, and this treatment was repeated three more times every 2 weeks. Skeletal muscles were removed at ≈21 weeks after initial bone marrow transplantation and 6 weeks after the last cardiotoxin injury.

Male-Specific Quantitative Real-Time PCR. DNA was extracted from blood, bone marrow cells, or muscle pieces remaining after sectioning with a GenElute mammalian genomic DNA purification kit (Sigma–Aldrich) according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA was quantified with the PicoGreen dsDNA Quantitation kit (Molecular Probes) on a TECAN Ultra 384 fluorescence reader, which allows a highly sensitive and specific quantification of dsDNA (18) Concentrations of all DNA used in real-time PCR assays were adjusted to 5 ng/μl. Male DNA in engrafted muscles was quantified by real-time PCR according to the hybridization probe format. The following primers and probes for the amplification of a 149-bp fragment from the murine SMCY gene (National Center for Biotechnology Information GI no. 5823128) (19) were used: forward primer, 5′-GCCAGTCATACCTCATCTCA-3′; reverse primer, 5′-CTCAGGTAGCCTTACAGACA-3′; fluorescent probes, 5′-CGTCCACGCCTGGAGACCATCT-fluorescein-3′ and 5′-LC Red640-GTCATTGCTGGTAGGACTACAGAGACTG-3′ (TIB MOLBIOL, Berlin). Specificity of the assay was tested with DNA from female mice as template. Mixtures of male and female mouse DNA were prepared as standards, ranging from 100% to 0.16% male DNA such that a total amount of 50 ng of genomic DNA per well corresponded to 50 ng to 80 pg of male DNA per well. PCR was run on an LightCycler instrument using LightCycler DNA master hybridization probes (Roche Diagnostics). Linear relationship (r = 0.98–0.99) between threshold cycle (Ct value) and log(amount of male DNA) was observed over the whole range of standards.

In Situ Hybridization. In situ hybridization of cryostat sections with a Y-specific probe was performed with nonradioactive DIG system as described in detail in ref. 20. As template for labeling of the probe, a fragment of the 5′ flanking region of Y1 (21) was used. For FISH, the signal was amplified with the tyramide-system (Perkin–Elmer) as described by ref. 22.

Immunostaining. Ten to 46 weeks after bone marrow transplantation, mice were either killed by cervical dislocation or transcardially perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde for GFP fixation in situ. Hindlimb muscles [soleus (SOL), extensor digitorum longus (EDL), and TA] were removed from the animals and snap-frozen or postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 3 h, washed in PBS for 24 h, and then soaked in 10% sucrose in PBS for 16–20 h at 4°C. Serial transverse cryosections 6 μm thick were fixed for 5 min in acetone, air dried, and blocked with 20% normal goat serum (Dianova, Hamburg, Germany) in PBS at room temperature for 30 min. The following primary antibodies diluted in PBS containing 0.5% (wt/vol) carageenan (carageenan-λ, Sigma–Aldrich) and 0.02% (wt/vol) sodium azide were used for overnight incubation at 4°C: rabbit anti-GFP at a 1:50 ratio (Molecular Probes), rat anti-macrophage at a 1:1 ratio (hybridoma supernatant TIB128, American Type Culture Collection), mouse anti-dystrophin at 1:20 (NCL-Dys2, NovoCastra), rabbit anti-M-cadherin at a 1:50 ratio (affinity-purified and produced in our laboratory according to ref. 23). Rat anti-Sca-1 direct conjugated with FITC at a 1:50 ratio (Ly-6A/E, BD Biosciences) was incubated for 1 h at 37°C. As secondary antibodies, Alexa Fluor 546-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG at a 1:200 ratio (Molecular Probes) or rhodamin red-X-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG or anti-rat IgG at 1:200 ratios (Jackson ImmunoResearch) were used. Nuclei were counterstained with 1 μg/ml bis-benzimide (Hoechst 33342, Sigma), and the sections were embedded in Fluoromont G (Paesel+Lorei, Hanau, Germany).

Results and Discussion

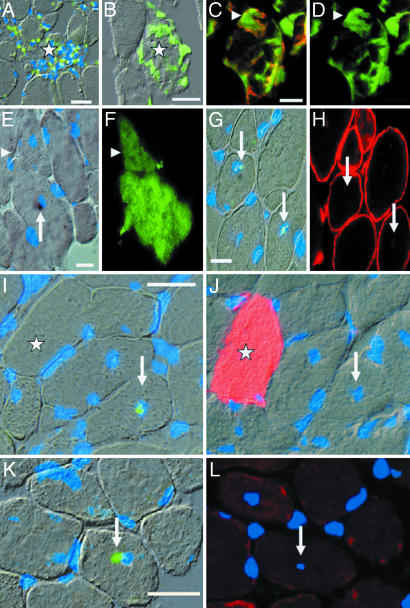

Bone Marrow-Derived Cells Incorporate into Muscle Fibers in mdx Mice and Silence the GFP Transgene. To trace bone marrow cells with an intact dystrophin gene in muscles of mdx mice, we transplanted whole bone marrow from adult male β-actin::GFP transgenic mice into sublethaly irradiated newborn recipients. GFP fluorescence (Fig. 1 B–D), GFP immunohistochemistry (Fig. 1J), and FISH with a Y chromosome-specific probe (Fig. 1 A) revealed that donor-derived cells most readily invade muscle fibers at sites of acute focal damage. Many of these cells express the macrophage marker Mac1 (Fig. 1 C and D), but ScaI-positive cells have also been identified (data not shown; see also refs. 1 and 24). Initially, the invading cells maintain their cellular entities and are detectable as circumscribed GFP accumulations, leaving the remaining cytoplasm of the invaded muscle fiber GFP negative (Fig. 1 B–D). Only after cell fusion and incorporation of donor nuclei into the muscle fiber can the spread of GFP occur within the fiber (Fig. 1 F and J), resulting in the presence of 1–4% GFP-positive fibers in SOL, EDL, and TA muscles in animals killed between 10 and 46 weeks after transplantation (Fig. 7A, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

Fig. 1.

Donor cells invade acutely damaged muscle fibers and persist in chronically repaired mdx muscle. (A) Y-FISH (green overlay) plus nuclear stain (bis-benzimide, blue overlay) reveals a dense infiltration of a damaged muscle fiber (star) by male donor cells. (B–D) Natively labeled GFP cells (green) are clearly recognizable as individual cells, indicating that fusion has not occurred. (C and D) An invaded donor cell (arrowheads) is identified as macrophage by Mac1 labeling (red in C; GFP fluorescence is green). (E–H) Donor nuclei (arrows in E and G) in muscle fibers expressing GFP (F) or dystrophin (H) demonstrated in adjacent sections. (E and G) Y-FISH (green in G) and permanent Y-in situ hybridization (black in E). (E and F) Arrowheads point at a separate fiber profile carrying GFP. (I–L) Silent donor nuclei (green) determined by Y-FISH in I and K (arrows) are not associated with GFP (star; red in J) or dystrophin (red in L) in adjacent sections. Note the normal appearance of muscle fibers. Blue overlay indicates bis-benzimide. (A, E, G, I, J, and K) Interference contrast light micrographs with fluorescence micrographs as overlays. (Bars: 20 μm.)

Nuclear staining revealed that, during fiber regeneration and local repair, the number of nuclei per muscle fiber profile on a 6-μm-thick section ranges from 0–5 nuclei. We wanted to exclude from our counts acutely damaged muscle fibers in which nuclei might not have been reprogrammed yet. We therefore counted only “repaired” myofibers defined as structurally intact profiles containing two or fewer nuclei including a centrally located donor nucleus. We tested the validity of this definition by employing NCAM, which is absent in normal muscle fibers but up-regulated in regenerating and denervated muscle fibers (25). Indeed, from 11 repaired profiles with Y chromosome-carrying donor nuclei, all were NCAM-negative, whereas 22 of 27 donor nuclei-carrying profiles with more than two nuclei in toto were associated with NCAM. Clearly, then, the donor nuclei that were selected were contained in matured sites of the muscle fiber lacking signs of regeneration apart from the central location of the donor nucleus.

Strikingly, only two of 36 such “chronically” incorporated donor nuclei were located in GFP-positive fibers (Table 1 and Fig. 1 E and F). For the vast majority, GFP immunofluorescence in serial sections adjacent to those containing donor nuclei was lacking (Fig. 1 I and J, arrows). In addition, no perinuclear GFP accumulation was detectable (Fig. 1J), indicating fusion but complete loss of transgene activity. At the same time, 60–90% of all nucleated blood cells were GFP-positive (Fig. 7A), which suggests that the transgene is silenced in the new cytoplasmic environment of the muscle fiber. Somewhat similar observations were reported on silencing of the β-galactosidase gene (26).

Table 1. Y-chromosome-positive nuclei in repaired muscle fibers of female mdx mice 16–46 weeks after transplantation of male bone marrow.

| Animal | Weeks implanted | Muscle | Fibers | Y+ | Y– | Sections Y-FISH | Profiles without Dys (with Dys) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dystrophin expression | |||||||

| 1 | 21 | TA R | 2,750 (111) | 0 | 3 | 1 | |

| TA L | 2,486 (44) | 0 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 2* | 28 | EDL R | 618 (9) | 0 | 5 | 5 | 3,068 (23) |

| EDL L | 711 (55) | 1 | 6 | 6 | 4,041 (287) | ||

| 3 | 28 | EDL L | 652 (18) | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| 4 | 28 | EDL L | 1,138 (15) | 1 | 5 | 1 | |

| 5 | 46 | EDL R | 850 (30) | 1 | 3 | 5 | 4,100 (100) |

| EDL L | 918 (31) | 1 | 6 | 5 | 4,335 (107) | ||

| Total | 9,833 (311) | 6 | 31 | 25 | 22,382 (705) | ||

| GFP expression | |||||||

| 6 | 16 | EDL R | 365 (5) | 1 | 0 | 1 | – |

| EDL L | 184 (3) | 0 | 1 | 1 | |||

| SOL L | 439 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||

| 7 | 19 | EDL R | 1,054 (7) | 0 | 9 | 1 | – |

| EDL L | 663 (3) | 0 | 1 | 1 | |||

| SOL R | 183 (1) | 0 | 1 | 1 | |||

| SOL L | 585 (7) | 0 | 4 | 1 | |||

| 8 | 19 | EDL R | 744 (7) | 0 | 6 | 1 | – |

| EDL L | 741 (11) | 0 | 4 | 1 | |||

| SOL L | 977 (19) | 0 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 9 | 19 | SOL L | 329 (4) | 0 | 0 | 1 | – |

| 10 | 19 | SOL L | 660 (32) | 0 | 3 | 1 | – |

| 11 | 19 | SOL R | 115 (2) | 0 | 2 | 1 | – |

| SOL L | 683 (16) | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||

| Total | 7,722 (102) | 2 | 34 | 14 |

Each of the 3–12 serial sections were alternately stained for dystrophin/GFP or processed for Y-FISH. Fibers indicates the total number of fibers on a complete cross-section. Each value in parentheses is the number of dystrophin/GFP-positive fibers observed in that muscle. Y+ indicates fiber profiles with donor nucleus surrounded by sections containing dystrophin or GFP. Y– indicates donor nuclei not associated with dystrophin or GFP in adjacent sections. Sections Y-FISH indicates the number of sections processed for Y-FISH. Profiles without Dys (with Dys) provides the summed numbers (from all sections processed for FISH) of muscle fiber profiles without or with dystrophin in both adjacent sections. R, right; L, left; –, not applicable.

Animal 2 was treated with 5-azadeoxycytidine and phenylbutyrate

Most Incorporated Donor Nuclei Fail to Induce a Permanent Myogenic Program. Next, we sought to determine whether donor nuclei integrated in chronically repaired muscle fibers induce the expression of muscle genes. To that end, we alternately detected either the donor nuclei with a Y chromosome-specific DNA probe or dystrophin on serial sections (illustrated in Figs. 2 and 3). Similarly to GFP expression, although the two marker genes would not be expected to be subject to the same sorts of silencing mechanisms, the majority of donor nuclei chronically incorporated in muscle fibers is not associated with dystrophin: Only six of 37 donor nuclei were located within dystrophin-carrying parts of fibers (Table 1; see also Fig. 1 G and H for a positive example and Fig. 1 K and L for a negative example). In contrast, we did find a small but significant enrichment of Y-positive nuclei in dystrophin-positive fiber profiles [six of 705 (0.85%) dystrophin-positive fiber profiles versus 31 of 22,382 (0.14%) dystrophin-negative fiber profiles (calculated from Table 1; P < 0.0001, Fischer's exact test)]. These results suggest that a small fraction of incorporated donor nuclei might indeed express dystrophin but clearly demonstrate that >84% are silent. Supporting our finding, Lapidos et al. described very recently that transplanted wild-type bone marrow cells failed to express sarcoglycan in δ-sarcoglycan-deficient muscle (27). Surprisingly, even after local implantation of human myogenic cell preparations in DMD patients, donor nuclei incorporated in muscle fibers were found that were not associated with dystrophin expression (28).

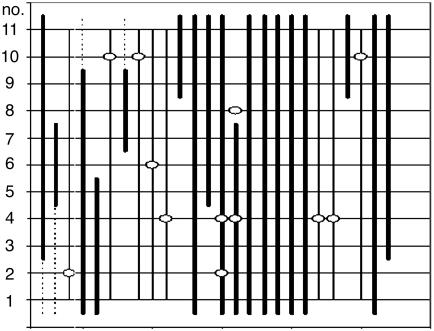

Fig. 2.

Schematic reconstruction of 11 serial sections through a TA muscle of a female mdx mouse 46 weeks after transplantation with whole bone marrow from a male β-actin::GFP mouse. Shown are the 26 muscle fibers that contain a donor nucleus (Y-FISH, dots) and/or dystrophin (thick lines). Stippled lines indicate that the staining for dystrophin was uncertain. Three donor nuclei are located inside dystrophin-positive muscle fibers (open rings on thick lines), and nine donor nuclei are located outside dystrophin-positive muscle fibers.

Fig. 3.

Distribution of muscle fibers containing dystrophin (black) or donor nuclei (white) in a complete cross-section of SOL muscle of a 28-week-old bone-marrow-transplanted mdx mouse. Twelve sections alternately stained for Y-FISH or dystrophin were evaluated and projected onto one plane. Note that not a single donor nucleus is associated with dystrophin.

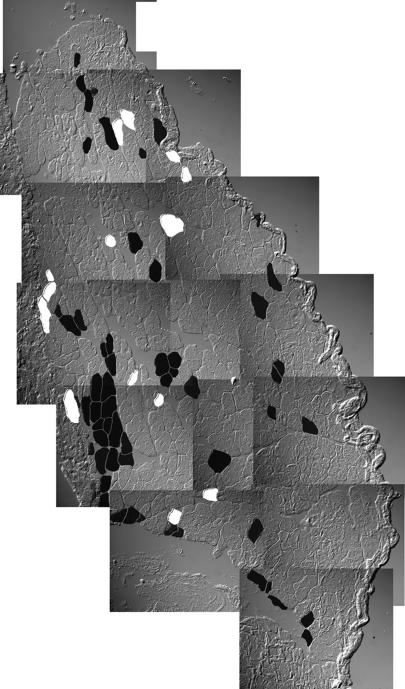

The mere presence of dystrophin-positive fibers in mdx mice can only provide circumstantial evidence for de novo expression from donor nuclei because of the well known phenomena of revertant fibers. Revertant fibers are functionally intact segments of muscle fibers with strong dystrophin expression caused by spontaneous alternative splicing, compared with the majority of muscle fibers, which lack the protein (14, 29). We reasoned that, because of recurrent focal damage and subsequent chronic repair processes, an increase in dystrophin-positive fibers over time has to be expected in muscles of mdx mice if the incorporated donor nuclei express the wild-type dystrophin gene. Therefore, we determined the number of dystrophin-positive fibers in irradiated, bone-marrow-transplanted mdx mice and in age-matched control mdx mice over long time periods. In both groups we observed a distinct increase in dystrophin-carrying fibers with age (Fig. 4). On average, the frequency of dystrophin-labeled fibers was not higher in experimental muscles from transplanted mice up to 46 weeks after implantation (Fig. 4, filled circles; n = 25) compared with control mice (Fig. 4, open circles; n = 41). In fact, presumably because of radiation-induced arrest of clonal expansion of revertant satellite cells, the frequency of revertant fibers is somewhat lower in transplanted mice (Fig. 4, regression lines). In accordance with our interpretation, we found this depression of dystrophin expression to be dose-dependent (Fig. 8, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). In addition, the body weight of irradiated mice was decreased in a dose-dependent manner and permanently reduced by ≈30% when irradiated with 5 Gy (Fig. 9, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Thus, the potential dystrophin contribution from donor nuclei cannot nearly compensate the impairment of endogenous satellite cells inflicted by a single, early postnatal hit of irradiation in mdx mice.

Fig. 4.

Frequency of muscle fibers containing dystrophin in muscles of mdx mice. ○, Untreated mdx mice showing revertant fibers (n = 38 muscles). •, Bone-marrow-transplanted and 5-Gy-irradiated mdx mice (n = 41 muscles). Also shown are linear regression lines.

Taken together, our results are consistent with the hypothesis that a small fraction of bone marrow-derived cells incorporated in muscle fibers express dystrophin either temporarily or to a very small extent but fail to significantly maintain expression over time.

Systemically Transplanted Cells Do Not Give Rise to Satellite Cells. Currently it is controversial whether bone marrow-derived cells have the ability to give rise to satellite cells (1, 2, 30). M-cadherin has been shown to be a reliable satellite cell marker in conjunction with the typical morphological localization within the basal lamina (23). Of 580 cells labeled with M-cadherin, we could not detect a single GFP-positive satellite cell in muscles from implanted mdx mice. This finding strongly suggests that circulating bone marrow-derived cells do not contribute to satellite cells even when taking into account a possible silencing of the transgene at a high rate similar to that in muscle fibers.

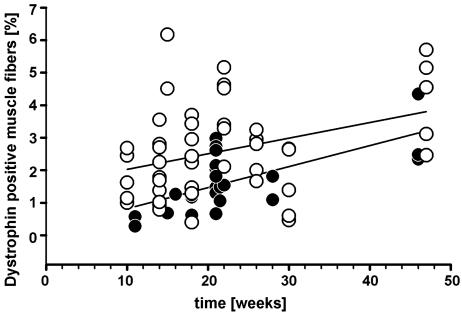

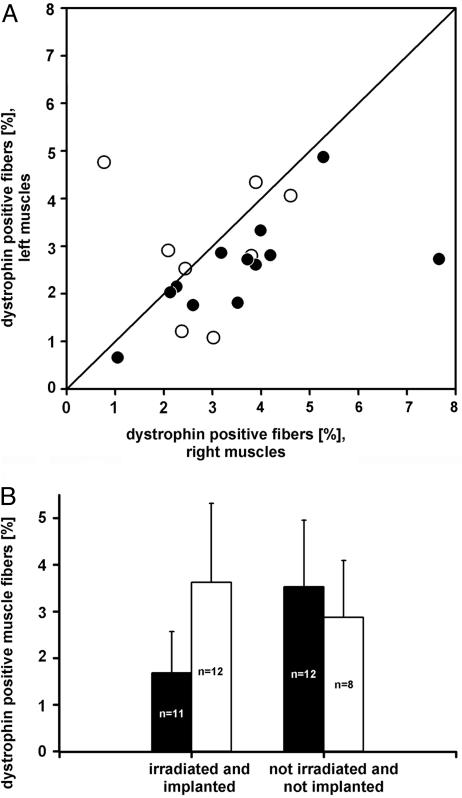

Acute Damage of mdx Muscles Leads to Increased Dystrophin-Expressing Fibers. It has been shown that repeated damage of wild-type muscle tissue results in an increase in GFP-positive muscle fibers in GFP bone marrow-chimeric animals (1, 3, 31). We therefore asked whether acute muscle damage in mdx mice enhances dystrophin expression. Indeed, 6 weeks after the last of four intramuscular cardiotoxin injections, the treated muscles displayed more dystrophin-positive fiber profiles than the untreated contralateral muscles (Fig. 5A, filled circles; P < 0.001, Wilcoxon signed-rank test) and muscles from age-matched, bone marrow-chimeric mdx mice (Fig. 5B, left histogram; 3.6 ± 1.7 versus 1.7 ± 0.88 SD; P = 0.025, t test). Importantly, cardiotoxin application to otherwise untreated (not irradiated, not bone-marrow-transplanted), age-matched control mdx mice caused no overall increase over untreated, mdx control mice (Fig. 5B, right histogram), and the direct comparison of treated and untreated contralateral muscles showed no difference (Fig. 5A, open circles; P value not significant, Wilcoxon ranked-sign test). These data clearly argue against the possibility that a higher resistance of revertant fibers against cardiotoxin is the cause for the relative increase in the bone-marrow-transplanted mice. Thus, after acute damage, an additional small fraction of blood-borne donor cells that enter damaged muscle fibers presumably become reprogrammed to contribute muscle proteins, yet the majority of donor nuclei still remains silent.

Fig. 5.

Effect of cardiotoxin on dystrophin expression. (A) Higher frequency of dystrophin-positive muscle fibers in cardiotoxin-treated (right) versus untreated contralateral TA and EDL muscles in bone-marrow-transplanted (•; n = 12; P < 0.001, Wilcoxon signed-rank test) mdx mice. No difference was observed in cardiotoxin-treated control mdx mice (○; P > 0.05, paired t test). (B) Cardiotoxin treatment of EDL and TA muscles in irradiated and bone-marrow-transplanted mdx mice (open bar in left histogram) causes a significant increase in the frequency of dystrophin-positive fiber profiles in comparison to irradiated and transplanted controls not treated with the toxin (black bars). In contrast, cardiotoxin is ineffective in otherwise untreated mdx muscles (right histogram). Data are expressed as means ± SD; n, number of muscles.

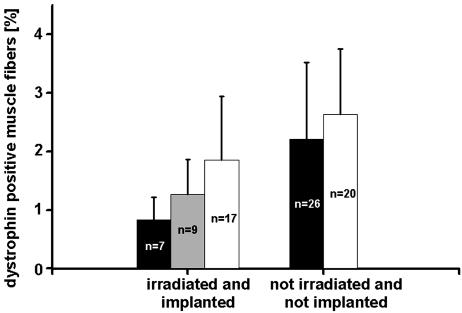

Chromatin-Modifying Agents Increase the Number of Dystrophin-Positive Fibers in Transplanted mdx Mice. Epigenetic alterations, such as histone modifications and DNA methylation, are considered regulators of genome-wide gene expression (32, 33). Furthermore, such alterations are assumed to play an important role in nuclear reprogramming (34, 35). It seems reasonable, therefore, that histone deacetylase inhibitors and DNA-demethylating agents could cause reprogramming, e.g., of bone marrow cells to allow later differentiation into the myogenic lineage. To test this hypothesis, we systemically applied a combination of phenylbutyrate and 5-azadeoxycytidine to 5-Gy-irradiated mdx mice transplanted with bone marrow from wild-type or β-actin::GFP transgenic animals (see Materials and Methods for details of drug application). After 6 weeks of drug treatment, we observed a 2-fold increase in dystrophin-positive fibers above bone-marrow-transplanted and irradiated controls (1.9 ± 1.1 SD versus 0.88 ± 0.39 SD; P < 0.005, t test) (Fig. 6, left histogram). A similar trend was detectable with half the drug dose (Fig. 6, gray bars). Incidentally, silent nuclei were still detectable after drug application (Table 1). Drug application to otherwise untreated mdx mice had no effect on the numbers of revertant fibers (Fig. 6, right histogram; P value not significant, t test). We observed a small drop in the total number of muscle fibers (by 10% and 17%) in drug-treated nonirradiated and irradiated mice, respectively), which resembles the normal difference in the number of muscle fibers during the early life of mdx mice as compared with wild-type mice (36).

Fig. 6.

Treatment with 5-azadeoxycytidine and phenylbutyrate (white bars, high drug dose) nearly doubles the frequency of dystrophin-positive fiber profiles normally present in irradiated and bone-marrow-transplanted (black bar in left histogram; P < 0.05) but not in untreated mdx mice (right histogram). Gray bar indicates that the low drug dose is less effective (P value not significant). Data are expressed as means ± SD; n, number of muscles.

Although our data do not ultimately prove that combined phenylbutyrate and 5-azadeoxycytidine treatment leads to myogenic reprogramming on the cellular level, the lack of significant muscle damage makes it the most likely explanation for the increase in dystrophin expression. In contrast, cardiotoxin injections result in acute muscle damage followed by endogenous regeneration, which presumably leads to an overall increased incorporation of blood-derived cells into mdx muscle fibers.

Bone Marrow Transplantation in DMD. The observation that bone-marrow-derived cells can contribute to nonhematopoietic organ systems has raised hopes for new therapeutic approaches in degenerative disorders like DMD (3, 5, 24). To achieve a substantial clinical repair, the cellular contribution to muscle fibers needs to be stable over long time periods, the bone-marrow-derived cells have to integrate in sufficient numbers, and they must efficiently initiate muscle gene expression. Importantly, in this study we can demonstrate a chronic engraftment of donor nuclei in muscle fibers of dystrophin-deficient mice beyond the period of acute fiber damage. Also, the total amount of previously incorporated donor nuclei in a whole muscle might not be negligible at all: Extrapolating from the number of such donor nuclei observed, there are on average 3.9 donor nuclei to be expected per centimeter of fiber length. [Thirty-seven plus 36 donor nuclei in 23,212 plus 7,722 donor nuclei; i.e., 30,934 fiber cross-sections, each with a thickness of 6 μm, would give a total of 185.6 mm of single fiber length (see Table 1).] In the best case, if we learned to activate all incorporated donor nuclei to transcribe dystrophin, that many patches of intact membrane (four per centimeter) would be added onto the muscle fiber, their size depending on the unknown size of the nuclear domain for dystrophin. However, our results clearly show that the vast majority of these bone-marrow-derived nuclei does not initiate long-term dystrophin expression in mdx muscle. The increase of dystrophin-positive fibers induced by DNA methylation and histone acetylation-modifying agents at the best provides proof of principle of reprogrammability, as does acute muscle damage after cardiotoxin treatment, yet the fraction of dystrophin-producing donor cells remains far below functional significance. Therefore, our results do not warrant clinical application in DMD at the present time. Given the relatively high frequency of silent nuclei, it might be worth, however, to reveal whether muscle gene expression can be induced in those “sleeping beauties.”

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Elke Franke, Dorit Glass, Silke Schöneborn, and Florian Küpper for outstanding technical assistance. This work was supported by Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung Grant FKZ 01 GN 0122 (to A.W.).

Author contributions: T.F., M.W., and A.W. designed research; G.W., V.J., R.S., M.Z., U.K., O.H., R.R.M., S.G., and S.S. performed research; G.W., R.S., and A.W. analyzed data; and G.W., M.W., and A.W. wrote the paper.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: DMD, Duchenne muscular dystrophy; TA, tibialis anterior; EDL, extensor digitorum longus; SOL, soleus.

References

- 1.Camargo, F. D., Green, R., Capetanaki, Y., Jackson, K. A. & Goodell, M. A. (2003) Nat. Med. 9, 1520-1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.LaBarge, M. A. & Blau, H. M. (2002) Cell 111, 589-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corbel, S. Y., Lee, A., Yi, L., Duenas, J., Brazelton, T. R., Blau, H. M. & Rossi, F. M. (2003) Nat. Med. 9, 1528-1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferrari, G., Cusella-De Angelis, G., Coletta, M., Paolucci, E., Stornaiuolo, A., Cossu, G. & Mavilio, F. (1998) Science 279, 1528-1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gussoni, E., Soneoka, Y., Strickland, C. D., Buzney, E. A., Khan, M. K., Flint, A. F., Kunkel, L. M. & Mulligan, R. C. (1999) Nature 401, 390-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bittner, R. E., Schofer, C., Weipoltshammer, K., Ivanova, S., Streubel, B., Hauser, E., Freilinger, M., Hoger, H., Elbe-Burger, A. & Wachtler, F. (1999) Anat. Embryol. 199, 391-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wernig, A., Irintchev, A., Hartling, A., Stephan, G., Zimmermann, K. & Starzinski-Powitz, A. (1991) J. Neurocytol. 20, 982-997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wernig, A., Zweyer, M. & Irintchev, A. (2000) J. Physiol. 522, 333-345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Irintchev, A., Rosenblatt, J. D., Cullen, M. J., Zweyer, M. & Wernig, A. (1998) J. Cell Sci. 111, 3287-3297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson, K. A., Mi, T. & Goodell, M. A. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 14482-14486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bachrach, E., Li, S., Perez, A. L., Schienda, J., Liadaki, K., Volinski, J., Flint, A., Chamberlain, J. & Kunkel, L. M. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 3581-3586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrari, G., Stornaiuolo, A. & Mavilio, F. (2001) Nature 411, 1014-1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grounds, M. D. (1983) Cell Tissue Res. 234, 713-722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu, Q. L., Morris, G. E., Wilton, S. D., Ly, T., Artem'yeva, O. V., Strong, P. & Partridge, T. A. (2000) J. Cell Biol. 148, 985-996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Danko, I., Chapman, V. & Wolff, J. A. (1992) Pediatr. Res. 32, 128-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dell'Agnola, C., Wang, Z., Storb, R., Tapscott, S. J., Kuhr, C. S., Hauschka, S. D., Lee, R. S., Sale, G. E., Zellmer, E., Gisburne, S., Bogan, J., et al. (2004) Blood 104, 4311-4318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okabe, M., Ikawa, M., Kominami, K., Nakanishi, T. & Nishimune, Y. (1997) FEBS Lett. 407, 313-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cosa, G., Focsaneanu, K. S., McLean, J. R., McNamee, J. P. & Scaiano, J. C. (2001) Photochem. Photobiol. 73, 585-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agulnik, A. I., Longepied, G., Ty, M. T., Bishop, C. E. & Mitchell, M. (1999) Mamm. Genome 10, 926-929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Irintchev, A., Langer, M., Zweyer, M., Theisen, R. & Wernig, A. (1997) J. Physiol. (London) 500, 775-785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Biddle, F. G., Eales, B. A. & Nishioka, Y. (1991) Genome 34, 96-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mezey, E., Chandross, K. J., Harta, G., Maki, R. A. & McKercher, S. R. (2000) Science 290, 1779-1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Irintchev, A., Zeschnigk, M., Starzinski-Powitz, A. & Wernig, A. (1994) Dev. Dyn. 199, 326-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doyonnas, R., LaBarge, M. A., Sacco, A., Charlton, C. & Blau, H. M. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 13507-13512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schäfer, R. & Wernig, A. (1998) J. Neurocytol. 27, 615-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blaveri, K., Heslop, L., Yu, D. S., Rosenblatt, J. D., Gross, J. G., Partridge, T. A. & Morgan, J. E. (1999) Dev. Dyn. 216, 244-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lapidos, K. A., Chen, Y. E., Earley, J. U., Heydemann, A., Huber, J. M., Chien, M., Ma, A. & McNally, E. M. (2004) J. Clin. Invest. 114, 1577-1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gussoni, E., Blau, H. M. & Kunkel, L. M. (1997) Nat. Med. 3, 970-977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thanh, L. T., Nguyen, T. M., Helliwell, T. R. & Morris, G. E. (1995) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 56, 725-731. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sherwood, R. I., Christensen, J. L., Conboy, I. M., Conboy, M. J., Rando, T. A., Weissman, I. L. & Wagers, A. J. (2004) Cell 119, 543-554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fukada, S., Miyagoe-Suzuki, Y., Tsukihara, H., Yuasa, K., Higuchi, S., Ono, S., Tsujikawa, K., Takeda, S. & Yamamoto, H. (2002) J. Cell Sci. 115, 1285-1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jenuwein, T. & Allis, C. D. (2001) Science 293, 1074-1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jaenisch, R. & Bird, A. (2003) Nat. Genet. 33, Suppl., 245-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li, E. (2002) Nat. Rev. Genet. 3, 662-673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rideout, W. M., III, Eggan, K. & Jaenisch, R. (2001) Science 293, 1093-1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schäfer, R., Zweyer, M., Knauf, U., Mundegar, R. R. & Wernig, A. (2005) Neuromuscular Disord. 15, 57-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.