Abstract

Abstract

Fucoxanthin, a bioactive carotenoid derived from algae, has attracted considerable attention for its applications in health, cosmetics, and nutrition. Advances in metabolic engineering, such as the overexpression of pathway-specific enzymes and enhancement of precursor availability, have shown promising results in improving production efficiency. However, despite its high value, the biosynthetic pathway of fucoxanthin remains only partially elucidated, posing significant challenges for metabolic engineering efforts. Recent studies have identified previously unknown enzymes and regulatory elements within the pathway, providing opportunities for further productivity enhancements through targeted metabolic modifications. Additionally, adaptive evolution, mutagenesis-driven strain development, and optimized cultivation conditions have demonstrated significant potential to boost fucoxanthin yields. This review consolidates the latest insights into the biosynthetic pathway of fucoxanthin and highlights metabolic engineering strategies aimed at enhancing the production of fucoxanthin and related carotenoids, offering approaches to design high-yielding strains. Furthermore, recent advancements in random mutagenesis and cultivation technology are discussed. By integrating these developments, more economically viable and environmentally sustainable fucoxanthin production systems can be achieved.

Key Points

• Insights into fucoxanthin biosynthesis enable targeted metabolic engineering.

• ALE and cultivation strategies complement metabolic engineering efforts.

• Balanced push–pull-block strategies improve fucoxanthin production efficiency.

Keywords: Fucoxanthin, Metabolic engineering, Carotenoid biosynthesis, Cultivation optimization

Introduction

Fucoxanthin is a carotenoid pigment predominantly found in algae, particularly in brown macroalgae and certain microalgae. It plays a critical role in facilitating efficient absorption of blue-green light (500 to 580 nm) for photoprotection and light harvesting (Bertrand 2010; Takaichi 2011; Anjana and Arunkumar 2024). Owing to its diverse bioactivities, including antioxidant, anti-obesity, anti-cancer, and anti-diabetic properties, fucoxanthin has garnered substantial interest in the cosmetic, nutraceutical, and pharmaceutical industries (Peng et al. 2011; Christaki et al. 2013; Galasso et al. 2017). Fucoxanthin is predominantly produced from natural sources, as its chemical synthesis has not yet been realized, making its extraction and purification highly resource intensive. Typical methods include harvesting fucoxanthin from brown macroalgae such as Laminaria spp. and Undaria pinnatifida, as well as microalgae like Phaeodactylum tricornutum. These processes often involve energy-intensive cultivation, advanced extraction techniques, and rigorous purification steps. All of them contribute to the high market price of fucoxanthin, underscoring the need for enhanced production efficiency (Pang et al. 2024).

To date, numerous studies have focused on enhancing productivity through cultivation engineering approaches (Wang et al. 2021; Khaw et al. 2022). In biomanufacturing, rational strain engineering using genetic modifications is generally considered effective for increasing productivity (Vavricka et al. 2020; Kato et al. 2022; Tanaka et al. 2024). Nevertheless, gaps remain in the elucidation of fucoxanthin biosynthetic pathways, leaving significant room for improvement in productivity through metabolic engineering approaches. Recent advances have identified fucoxanthin biosynthetic genes in Phaeodactylum tricornutum (Dautermann et al. 2020; Bai et al. 2022; Cao et al. 2023). These findings are expected to accelerate the application of metabolic engineering strategies for fucoxanthin production.

This review presents an overview of the current understanding of fucoxanthin biosynthetic pathways and highlights key metabolic engineering strategies that could play a crucial role in enhancing fucoxanthin production (Fig. 1). Additionally, recent advancements in mutation breeding and optimization of cultivation conditions are discussed as complementary approaches to metabolic engineering for improving fucoxanthin yields. Insights gained from omics analyses of mutant strains and various cultivation conditions may further lead to the discovery of novel strategies for metabolic engineering.

Fig. 1.

“Push–pull-block” metabolic engineering strategy for developing a fucoxanthin-producing strain. Random mutagenesis, adaptive laboratory evolution, and optimization of culture condition are complementary approaches for fucoxanthin production

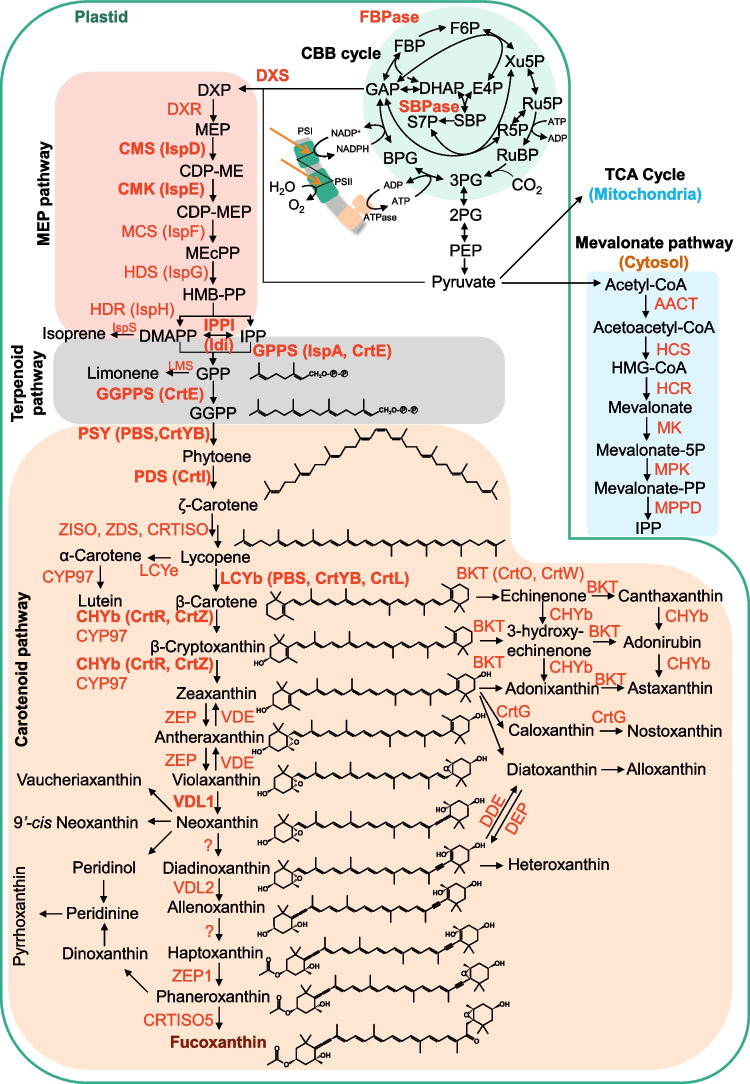

Biosynthetic pathway of fucoxanthin

The biosynthetic pathway of fucoxanthin, a carotenoid, has not been fully elucidated. To date, candidate genes corresponding to known carotenoid biosynthetic enzymes have been identified through genomic analyses of diatoms, particularly P. tricornutum (Bertrand 2010; Dambek et al. 2012). Carotenoid biosynthesis begins with the methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway, which produces dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP) and isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) (Fig. 2). These precursors are converted to β-carotene through the sequential actions of phytoene synthase (PSY), phytoene desaturase (PDS), ζ-carotene desaturase (ZDS), and lycopene β-cyclase (LCYb) (Dambek et al. 2012). β-Carotene is subsequently converted to zeaxanthin by β-carotene hydroxylase (CHYb). Zeaxanthin undergoes two epoxidation steps catalyzed by zeaxanthin epoxidase (ZEP) to violaxanthin. Violaxanthin is converted back to zeaxanthin by violaxanthin de-epoxidase (VDE), which is activated by acidification of the thylakoid lumen under high-light conditions in land plants, green algae, and some groups of chromalveolate algae. Together, these reactions constitute the violaxanthin cycle for photoprotective defense (Goss and Jakob 2010). In P. tricornutum, the conversion of β-carotene to zeaxanthin is catalyzed by cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYP97) rather than the CHYb (Cui et al. 2019). Among three ZEP genes in P. tricornutum, zep2 likely mediates the conversion of zeaxanthin to violaxanthin (Eilers et al. 2016a; Græsholt et al. 2024).

Fig. 2.

General metabolic pathway of fucoxanthin biosynthesis. Abbreviations: AACT, acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase; BKT, beta-carotenoid ketolase; BPG, 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate; CBB, Calvin–Benson–Bassham; CDP-ME, 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methylerythritol; CDP-MEP, 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 2-phosphate; CHYb, beta-carotenoid hydroxylase; CMK, 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methyl-d-erythritol kinase; CMS, 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 4-phosphate cytidylyltransferase; CRTISO, carotenoid isomerase; CYP97, cytochrome P450 hydroxylase; DDE, diadinoxanthin de-epoxidase; DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate; DEP, diatoxanthin epoxidase; DMAPP, dimethylallyl pyrophosphate; DXR, 1-deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase; DXP, 1-deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate; DXS, 1-deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate synthase; E4P, erythrose 4-phosphate; FBP, fructose 1,6-bisphosphate; F6P, fructose 6-phosphate; GAP, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate; GGPP, geranylgeranyl diphosphate; GGPPS, geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase; GPP, geranyl diphosphate; GPPS, geranyl diphosphate synthase; HCR, HMG-CoA reductase; HCS, hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA synthase; HDR, 4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl diphosphate reductase; HDS, 4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl diphosphate synthase; HGM-CoA, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA; HMB-PP, (E)−4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-enyl pyrophosphate; IPP, isopentenyl pyrophosphate; IPPI, isopentenyl-diphosphate isomerase; IspS, isoprene synthase; LCYb, lycopene beta cyclase; LCYe, lycopene epsilon cyclase; MCS, 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase; LMS, limonene synthase; MEcPP, 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate; MEP, 2-C-methylerythritol 4-phosphate; MK, mevalonate-5-kinase; MPK, phosphomevalonate kinase; MPPD, mevalonate-5-pyrophosphate decarboxylase; NXS, neoxanthin synthase; PDS, phytoene desaturase; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; PSI, photosystem I; PSII, photosystem II; PSY, phytoene synthase; 2PG, 2-phosphoglycerate; 3PG, 3-phosphoglycerate; RuBP, ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate; R5P, ribose 5-phosphate; Ru5P, ribulose 5-phosphate; SBP, sedoheptulose 1,7-bisphosphate; S7P, sedoheptulose 7-phosphate; TCA, tricarboxylic acid; VDE, violaxanthin de-epoxidase; VDL, violaxanthin de-epoxidase-like; Xu5P, xylulose 5-phosphate; ZDS, zeta-carotene desaturase; ZEP, zeaxanthin epoxidase; ZISO, zeta-carotene isomerase

Fucoxanthin biosynthesis proceeds through neoxanthin, which is derived from violaxanthin (Fig. 2). The enzyme violaxanthin de-epoxidase-like 1 (VDL1), responsible for converting violaxanthin to neoxanthin, was identified in Nannochloropsis oceanica using a random insertional mutagenesis screening approach (Dautermann et al. 2020). In P. tricornutum, two additional enzymes involved in downstream steps of the pathway have been identified: VDL2, which converts diadinoxanthin to alloxanthin, and ZEP1, which converts haptaxanthin to phaneroxanthin (Bai et al. 2022). In diatoms and haptophytes, including P. tricornutum, diadinoxanthin is de-epoxidized to diatoxanthin under high light conditions, where it dissipates excess energy through non-photochemical quenching. Diatoxanthin is epoxidized back into diadinoxanthin under low light conditions, forming diadinoxanthin cycle (Goss et al. 2006). In P. tricornutum, diadinoxanthin is de-epoxidized to diatoxanthin by VDE (Lavaud et al. 2012), while diatoxanthin is suggested to be epoxidized back to diadinoxanthin by ZEP3 (Græsholt et al. 2024).

A novel enzyme responsible for the final step of fucoxanthin biosynthesis, CRTISO5, was recently identified. CRTISO5 converts phaneroxanthin to fucoxanthin and, while structurally similar to conventional carotenoid cis–trans isomerases (CRTISO), exhibits a distinct enzymatic function. Specifically, CRTISO5 catalyzes a hydration reaction at the carbon–carbon triple bond of phaneroxanthin, leading to fucoxanthin production (Cao et al. 2023). In P. tricornutum mutants lacking CRTISO5, fucoxanthin synthesis was completely inhibited, and phaneroxanthin accumulated instead, demonstrating the essential role of CRTISO5 in fucoxanthin biosynthesis.

Despite these advancements, the enzymes responsible for the conversion of neoxanthin to diadinoxanthin and alloxanthin to haptaxanthin remain unidentified. Furthermore, fucoxanthin-producing algae, including brown algae (Phaeophytes), golden-brown algae (Chrysophytes), and raphidophyte algae, lack orthologs of CRTISO5 and P. tricornutum ZEP1, indicating that they may utilize alternative pathways for fucoxanthin biosynthesis (Bai et al. 2022; Cao et al. 2023).

Metabolic engineering strategies for fucoxanthin production

Metabolic engineering approaches for efficient fucoxanthin production rely on a detailed understanding of its biosynthetic pathway. Although the complete biosynthetic pathway of fucoxanthin has yet to be fully elucidated, enhancing precursor supply pathways has been suggested as an effective strategy (Table 1). Conversely, substantial progress has been achieved in the metabolic engineering of carotenoids with well-characterized biosynthetic pathways, such as carotenes and astaxanthin, using various genetic engineering techniques (Srivastava et al. 2022; Yu et al. 2024).

Table 1.

Strain development for carotenoid production using metabolic engineering strategies

| Pigment | Species | Strategy | Effect | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fucoxanthin | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | Introduction of PSY | 1.45-fold increased production | Kadono et al. 2015 |

| Fucoxanthin | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | Expression of DXS or PSY | 24.2 mg/g DCW (DXS), 18.4 mg/g DCW (PSY) | Eilers et al. 2016a, b |

| Fucoxanthin | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | Vdr/Vde/Zep3 triple overexpression | fourfold increased production | Manfellotto et al. 2020 |

| Fucoxanthin | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | Overexpression of CMK or CMS | 1.83-fold (CMK), 1.82-fold (CMS) enhanced production | Hao et al. 2021 |

| Fucoxanthin | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | Overexpression of HSF1 | 6.2 mg/g DCW | Song et al. 2023 |

| Fucoxanthin | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | Dual overexpression of DXS and LYCB | 6.53 mg/g DCW | Cen et al. 2022 |

| Fucoxanthin | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | Overexpression of VDL1 | Significant increases by 8.2 to 41.7% in fucoxanthin content | Li et al. 2024 |

| Limonene | Synechocystis PCC 6803 | Expression of limonene synthase, dxs, crtE, and ipi | 19 μg/L/day | Kiyota et al. 2014 |

| Isoprene | Synechocystis PCC 6803 | Expression of Dxs and Ipi | 2.8 mg/g DCW | Englund et al. 2018 |

| β-Carotene | Chlamydomonas reinhardtii | Expression of crtB gene from Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous | 38% enhancement in β-carotene | Rathod et al. 2020 |

| Zeaxanthin | Synechococcus elongatus PCC7942 | Overexpression of crtR gene | 1.36-fold increase in yield (mg/g DCW) | Sarnaik et al. 2018 |

| Zeaxanthin | Chromochloris zofingiensis | Insertion or substitution in β-carotene ketolase (BKT) gene 1 | 7–11-fold increase (compared to wild type) | Ye and Huang 2019 |

| Canthaxanthin | Chlamydomonas reinhardtii | Overexpression of Cr-bkt gene | 2.34-fold increase in the canthaxanthin | Tran and Kaldenhoff 2020 |

| Astaxanthin | Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous | Introduction of multiple copies of crtYB | 191% increase compared wild type | Ledetzky et al. 2014 |

| Astaxanthin and canthaxanthin | Dunaliella salina | Introduction of bkt gene from Haematococcus pluvialis | Astaxanthin and canthaxanthin with maximum content of 3.5 and 1.9 μg/g | Anila et al. 2016 |

| Astaxanthin | Haematococcus pluvialis | Overexpression of pds gene | 67% higher astaxanthin content than the wild type | Galarza et al. 2018 |

| Astaxanthin | Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 | Expression of crtW and crtZ | 50% increase in astaxanthin accumulation (compared to wild type) | Menin et al. 2019 |

| Astaxanthin | Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 | Insertion and expression of bkt and crtR-B from H. pluvialis | 4.81 mg/g DCW | Liu et al. 2019 |

| Astaxanthin | Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002 | Expression of crtW and crtZ | 3 mg/g DCW | Hasunuma et al. 2019 |

| Astaxanthin | Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 | Expression of crtW, crtZ, F/SBPase, dxs, ispA | 29.6 mg/g DCW | Diao et al. 2020 |

| Astaxanthin | Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 | Expression of crtW, crtZ, dxs, pds | 1 μg/mL/OD730 | Shimada et al. 2020 |

| Astaxanthin | Chlamydomonas reinhardtii | CrBKT overexpression | 4.3 mg/L/day | Perozeni et al. 2020 |

Several steps of the carotenoid biosynthetic pathways overlap with those involved in fucoxanthin synthesis (Fig. 2). Consequently, the metabolic engineering strategies established for these carotenoids could be adapted for engineering strains to enhance fucoxanthin production. A fundamental approach in metabolic engineering is the push–pull-block strategy (Fig. 1). In the context of fucoxanthin production, the push strategy aims to increasing precursor availability by enhancing the methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway, while the pull strategy focuses on upregulating downstream pathways involved in carotenoid biosynthesis. The block strategy involves knocking out or downregulating competing pathways, such as those involved in the synthesis of other isoprenoids. Employing a balanced combination of these strategies can lead to substantial improvements in carotenoid production yields (Lyu et al. 2022). The enzymes involved in the fucoxanthin biosynthetic pathway in P. tricornutum, as well as the enzymes introduced through metabolic engineering approaches, are summarized in Table 2. The following sections outline specific strategies organized by each segment of the pathway.

Table 2.

List of enzymes related to fucoxanthin biosynthesis in Phaeodactylum tricornutum and/or utilized in metabolic engineering for fucoxanthin production

| Enzyme name | Symbol | Organism | UniProt or GenBank | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fructose-1,6-/sedoheptulose 1,7-bisphosphatase | FBP/SBPase | Synechococcus sp. PCC7002 | B1XLK5 | FBP > F6P, SBP > S7P | Diao et al. 2020 |

| 1-Deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate synthase | DXS | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | B7S452 | GAP + Pyr > DXP | Eilers et al. 2016a, b, Diao et al. 2020 |

| 1-Deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate synthase | DXS | Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 | sll1945 | GAP + Pyr > DXP | Kiyota et al. 2014 |

| 1-Deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate reductoisomerase | DXR | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | B7FQZ5 | DXP > MEP | |

| 2-C-Methyl-d-erythritol 4-phosphate cytidylyltransferase | CMS (IspD) | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | B7G4H5 | MEP > CDP-ME | |

| 4-(Cytidine 5′-diphospho)−2-C-methyl-d-erythritol kinase | CMK (IspE) | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | B7FUR0 | CDP-ME > CDP-MEP | Hao et al. 2021 |

| 2-C-Methyl-d-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase | MCS (IspF) | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | B7FYU1, B7FYU2 | CDP-MEP > MEcPP | Hao et al. 2021 |

| 1-Hydroxy-2-methyl-2-(E)-butenyl-4-diphosphate synthase | HDS (IspG) | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | B7FV10 | MEcPP > HMB-PP | |

| 4-Hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-enyl diphosphate reductase | HDR (IspH) | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | B7FUL0 | HMB-PP > DMAPP, HMB-PP > IPP | |

| Isopentenyl pyrophosphate isomerase | Ipi | Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 | P74287 | DMAPP = IPP | Kiyota et al. 2014, Englund et al. 2018 |

| Farnesyl diphosphate synthase | FPPS | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | B7GA81 | GPP + IPP > FPP | |

| Farnesyl diphosphate synthase | IspA | Escherichia coli | P22939 | GPP + IPP > FPP | Diao et al. 2020 |

| Geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase | CrtE | Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 | P72683 | DMAPP + IPP > GPP, GPP + IPP > FPP, FPP + IPP > GGPP | Kiyota et al. 2014, Satta et al. 2022 |

| Geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase | GGPPS | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | B7G3T2, B7FU89 | FPP + IPP > GGPP | |

| 15-cis-Phytoene synthase | PSY (PBS) | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | B7FVW3 | GGPP > phytoene | Kadono et al. 2015, Eilers et al. 2016a, b |

| Bifunctional lycopene cyclase/phytoene synthase | CrtYB | Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous | Q7Z859 | GGPP > phytoene, lycopene > β-carotene | Ledetzky et al. 2014, Rathod et al. 2020 |

| Phytoene desaturase | PDS (CrtI) | Haematococcus pluvialis | O65813 | Phytoene > ζ-carotene | Galarza et al. 2018 |

| Phytoene desaturase | PDS (CrtI) | Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 | P29273 | Phytoene > ζ-carotene | Shimada et al. 2020 |

| Phytoene desaturase | PDS (CrtI) | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | B5Y4Q5 | Phytoene > ζ-carotene | Dambek et al. 2012 |

| ζ-Carotene desaturase | ZDS | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | B7FPC4 | ζ-Carotene > prolycopene | |

| Carotenoid isomerase | CRTISO1 | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | B7FXV4 | ||

| Carotenoid isomerase | CRTISO2 | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | B7G5L7 | ||

| Carotenoid isomerase | CRTISO3 | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | B7G5U6 | ||

| Carotenoid isomerase | CRTISO4 | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | B7FWY8 | Prolycopene > lycopene | Sun et al. 2022 |

| Carotenoid isomerase | CRTISO5 | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | B7FQF7 | Phaneroxanthin > fucoxanthin | Cao et al. 2023 |

| Lycopene beta-cyclase | LCYB | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | B7FNX5 | Lycopene > β-carotene | |

| Cytochrome P450 beta hydroxylase | CYP97A | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | A0A3S7L8P2 | β-Carotene > zeaxanthin | Cui et al. 2019 |

| β-Carotene oxygenase | CrtR | Synechococcus PCC 7002 | B1XIX7 | β-Carotene > zeaxanthin | Sarnaik et al. 2018 |

| Carotenoid hydroxylase | crtR-B | Haematococcus pluvialis | AF162276.1 | β-Carotene > zeaxanthin | Liu et al. 2019 |

| β-Carotene hydroxylase | CrtZ | Brevundimonas sp. SD-212 | MK214313 | β-Carotene > zeaxanthin | Menin et al. 2019 |

| 4,4′β-Carotene oxygenase | CrtW | Brevundimonas sp. SD-212 | MK214312 | Zeaxanthin > astaxanthin | Menin et al. 2019 |

| β-Carotene ketolase | BKT | Haematococcus pluvialis | AY603347.1 | Zeaxanthin > astaxanthin | Liu et al. 2019 |

| β-Carotene ketolase | BKT | Chlamydomonas reinhardtii | Q4VKB4 | Zeaxanthin > astaxanthin | Perozeni et al. 2020, Tran and Kaldenhoff 2020 |

| Zeaxanthin epoxidase | ZEP1 | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | B7FYW4 | Haptoxanthin > phaneroxanthin | Bai et al. 2022 |

| Zeaxanthin epoxidase | ZEP2 | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | B7FQV6 | Zeaxanthin > violaxanthin | Eilers et al. 2016a, Græsholt et al. 2024 |

| Zeaxanthin epoxidase | ZEP3 | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | B7FUR7 | Diatoxanthin > diadinoxanthin | Manfellotto et al. 2020, Græsholt et al. 2024 |

| Violaxanthin de-epoxidase | VDE | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | B7FUR6 | Violaxanthin > zeaxanthin | Manfellotto et al. 2020 |

| Violaxanthin de-epoxidase-like | VDL1 | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | B7G087 | Violaxanthin > neoxanthin | Dautermann et al. 2020, Li et al. 2024 |

| Violaxanthin de-epoxidase-like | VDL2 | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | B7FYW5 | Diadinoxanthin > allenoxanthin | Bai et al. 2022 |

| Violaxanthin de-epoxidase-related | VDR | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | B7FR37 | Manfellotto et al. 2020 |

Enhancement of the MEP pathway

Enhancing the MEP pathway, which produces IPP, a common precursor of carotenoids, has been demonstrated to be effective for increasing the production of many carotenoids, including fucoxanthin. In P. tricornutum, overexpression of the gene encoding 1-deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate synthase (DXS), which catalyzes the first step of the MEP pathway, resulted in a 2.4-fold increase in fucoxanthin content compared to the wild-type strain (Eilers et al. 2016b). In addition to DXS, the overexpression of LCYB achieved production levels of 6.53 and 4.34 mg/g DCW for fucoxanthin and β-carotene, respectively (Cen et al. 2022). Overexpression of DXS has been widely employed to enhance the production of various terpenoids and carotenoids, such as limonene, isoprene, and astaxanthin, with its efficacy well documented (Kiyota et al. 2014; Englund et al. 2018; Diao et al. 2020; Shimada et al. 2020). Furthermore, overexpression of 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methyl-d-erythritol kinase (CMK) and 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 4-phosphate cytidylyltransferase (CMS) genes in P. tricornutum, which participate in subsequent steps of the MEP pathway, has also been shown to increase fucoxanthin accumulation by 83 and 82%, respectively (Hao et al. 2021).

Enhancement of the terpenoid biosynthetic pathway

Terpenoid biosynthesis begins with IPP and DMAPP derived from the MEP pathway (Fig. 1). Overexpression of ipi (isopentenyl pyrophosphate isomerase) and crtE (geranyl pyrophosphate synthase) has been shown to effectively increase the production of isoprenoids. Overexpression of crtE and ipi together with dxs in the limonene-producing strain resulted in a 37% increase in limonene titer in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (Kiyota et al. 2014). Overexpressing ipi in Synechocystis also gave 1.9-fold increase in isoprene production (Englund et al. 2018). Additionally, ispA (farnesyl diphosphate synthase) overexpression has been reported to enhance astaxanthin production (Diao et al. 2020). Given these findings, it is plausible that enhancing gene expression of terpenoid synthesis could also contribute to increased production of fucoxanthin as well as other carotenoids.

Enhancement of the carotenoid biosynthetic pathway

Carotenoid biosynthesis begins with the conversion of geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP) into phytoene by PSY, followed by the production of ζ-carotene from phytoene by PDS. Overexpression of these key enzymes in the carotenoid biosynthetic pathway has been shown to enhance fucoxanthin production in P. tricornutum. Specifically, introducing PYS under the control of fcpA promoter increased fucoxanthin content 1.45-fold compared to the levels in the wild-type strain (Kadono et al. 2015). Similarly, PSY introduction resulted in a 1.8-fold higher fucoxanthin content relative to wild type (Eilers et al. 2016b). Overexpression of PDS in the chloroplast of Haematococcus pluvialis showed a 67% increase in astaxanthin content compared to the wild type (Galarza et al. 2018). The effectiveness of PDS overexpression has also been demonstrated in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 for astaxanthin production (Shimada et al. 2020), highlighting its potential utility as a target for pathway enhancement across various host systems.

Lycopene, a critical intermediate in the carotenoid biosynthetic pathway, serves as a precursor for several downstream carotenoids. Lycopene is converted into α-carotene by lycopene epsilon cyclase (LCYe) and into β-carotene by LCYb. Since β-carotene is the precursor for both astaxanthin and fucoxanthin, enhancing LCYb activity is crucial for boosting their production. The crtYB gene, which encodes a bifunctional enzyme with PSY and LCYb activities, has been identified as a key target for pathway optimization (Verdoes et al. 2003). Introducing crtYB in Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous resulted in a 191% increase in astaxanthin content compared to the wild-type strain (Ledetzky et al. 2014).

The introduction of β-carotene hydroxylase genes, such as crtR or crtZ, has been shown to enhance carotenoid production. For example, introducing crtR from Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002 into Synechococcus sp. PCC 7942 increased zeaxanthin yield by 1.36-fold compared to the wild-type strain (Sarnaik et al., 2017). Similarly, crtZ has been reported to contribute to increased carotenoid productivity in other host systems (Liu et al. 2019). In the fucoxanthin biosynthetic pathway after violaxanthin, overexpression of VDL1 increased fucoxanthin content by 8.2 to 41.7% without negatively affecting growth (Li et al. 2024). Future studies are needed to elucidate the effects of overexpressing other enzymes, such as VDL2, ZEP1, and CRTISO5, on fucoxanthin production.

Other engineering targets

Productivity can also be improved by modifying enzymes or regulatory factors of the Calvin cycle. Overexpression of fructose-1,6/sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase (F/SBPase) gene, a key rate-limiting enzyme in the Calvin cycle, has been reported to enhance astaxanthin content by 27% (Diao et al. 2020). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (GAP) and pyruvate, which are the initial substrates of the methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway, can be generated through the Entner–Doudoroff (ED) pathway. Supplying pyruvate and GAP via the ED pathway has been reported to effectively enhance the production of MEP pathway–derived compounds (Liu et al. 2013, 2014; Li et al. 2015). In P. tricornutum, overexpression of HSF1, a heat shock transcription factor that responds to various stresses such as nutrient deprivation, resulted in an increase in fucoxanthin content by 64 to 99% (Song et al. 2023). HSF1 has been suggested to positively regulate DXS, a key enzyme in the MEP pathway.

Random mutagenesis and adaptive laboratory evolution

Random mutagenesis using appropriate mutagens or adaptive laboratory evolution (ALE) can effectively enhance carotenoid production, including fucoxanthin (Bleisch et al. 2022; Trovao et al. 2022). Yi et al. combined UV-C mutagenesis with adaptive evolution in P. tricornutum, leading to improved fucoxanthin productivity (Yi et al. 2015). Following UV treatment, mutant strains with 1.7-fold higher fucoxanthin content compared to the wild type were obtained. Adaptive evolution further enhanced tolerance to photooxidative stress and improved light-harvesting efficiency. In subsequent studies, the same group employed chemical mutagens such as ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS) and N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (NTG) combined with fluorescence-based high-throughput screening to select P. tricornutum mutants (Yi et al. 2018). This approach yielded mutant strains with up to 69.3% higher fucoxanthin content. Wang et al. (2023a, b) developed a mixotrophic Nitzschia closterium strain using glucose as a carbon source through ALE. This strain exhibited enhanced carbon metabolism, resulting in a 79.2% increase in fucoxanthin productivity (Wang et al. 2023a, b). In the resulting strain, carbon flux toward the TCA cycle and the levels of sugar phosphates were enhanced, providing sufficient ATP and NADPH. However, identifying specific causal genes through random mutagenesis and ALE remains challenging. To further understand the genetic basis, whole-genome sequencing of the evolved strain would be required.

Culture conditions for fucoxanthin production and adaptation mechanisms

Besides metabolic engineering strategy, optimizing culture conditions is a critical strategy for significantly enhancing fucoxanthin production efficiency. Numerous studies have reported the effects of various culture parameters on fucoxanthin production, which have been summarized in several reviews (Wang et al. 2021; Khaw et al. 2022).

Among model organisms, P. tricornutum has been extensively studied for its capability to produce fucoxanthin (Pang et al. 2024). Under high light conditions (300 μmol photons m−2 s−1), the expression of many carotenoid biosynthetic genes is downregulated, and fucoxanthin content decreases significantly (Ding et al. 2023). When shifted to low light conditions (50 μmol photons m−2 s−1), the expression of some genes recovers including genes encoding light-harvesting complexes, and fucoxanthin content returns to its original level (Ding et al. 2023). Among the recovered genes, GGPPS, a key enzyme in carotenoid biosynthesis, is likely to contribute to the fucoxanthin recovery. Similarly, in Isochrysis galbana, high light conditions (300 μmol photons m−2 s−1) lead to reduced fucoxanthin content and productivity (Li et al. 2022). This reduction is believed to be caused by the downregulation of MEP pathway genes. In addition to light intensity, the wavelength of light also influences fucoxanthin production. In I. galbana, green light has been shown to activate genes related to photosynthetic antenna proteins and carotenoid biosynthesis likely via MYB family transcription factors, thereby increasing fucoxanthin production (Chen et al. 2023).

Recently, the haptophyte Pavlova sp. has garnered attention as a promising strain for commercial production due to its lack of a cell wall, which facilitates easier extraction of fucoxanthin. Compared to other brown marine microalgae such as Skeletonema costatum and Chaetoceros gracilis, Pavlova sp. exhibits a higher capacity for fucoxanthin production (Chen et al. 2023). Kanamoto et al. conducted a series of developments, including strain selection, optimization of culture conditions, and scale-up studies for Pavlova sp. They achieved a fucoxanthin productivity of 4.88 mg/L/day under outdoor cultivation using the Pavlova sp. OPMS 30543 strain in an acrylic pipe photobioreactor with 60-mm diameter (Kanamoto et al. 2021). Their finding revealed that fucoxanthin production was higher when 400 mg/L NaNO3 was used as the nitrogen source compared to NH4Cl. Metabolomic analysis further demonstrated that the presence of NaNO3 increased the levels of intermediate metabolites related to fucoxanthin biosynthesis, such as 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate (MEcPP), β-carotene, and diadinoxanthin (Yoshida et al. 2023). In Pavlova sp. and other algae, mixotrophic cultivation using organic carbon sources such as glycerol has proven effective, enhancing metabolic activity and increasing fucoxanthin productivity. In the Pavlova gyrans OPMS 30543X strain, the highest fucoxanthin production was achieved under mixotrophic conditions with 10 mM glycerol and a light intensity of 100 μmol photons m−2 s−1 (Yoshida et al. 2024). In Cylindrotheca sp., the addition of glycerol (2 g/L) was reported to increase fucoxanthin production by 29% (Wang et al. 2023a, b). Glycerol is converted into GAP, one of the starting substrates of the MEP pathway, through the actions of glycerol kinase, glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, and triose-phosphate isomerase. Therefore, it may be effective for enhancing the production of carotenoids, including fucoxanthin. Conversely, glucose supplementation (5 g/L) in Nitzschia laevis enhances the yield of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), while simultaneously decreasing fucoxanthin content, suggesting a shift in metabolic priorities (Mao et al. 2021). The reduction in fucoxanthin production is likely associated with the decreased gene expression of key enzymes in the carotenoid biosynthetic pathway, specifically PDS and ZISO.

Challenges and future prospects in metabolic engineering for fucoxanthin production

The biosynthetic pathway of fucoxanthin involves numerous enzymatic reactions, yet the identification of rate-limiting steps (bottlenecks) remains incomplete. Metabolomics has been proposed as an effective tool for identifying such bottlenecks (Vavricka et al. 2020; Kato et al. 2022). Additionally, integrating machine learning with metabolomics facilitates the identification of key gene targets (Tanaka et al. 2024). In pathways characterized by complex regulatory mechanisms, such as the MEP pathway, a thorough understanding of these regulatory processes is crucial (Volke et al. 2019). For instance, in P. tricornutum, the DXS enzyme is regulated at the transcriptional level by the heat shock transcription factor HSF1 (Song et al. 2023). Carotenoid biosynthetic genes are also significantly influenced by light intensity and wavelength through transcription factors such as those of the MYB family proteins (Li et al. 2022; Chen et al. 2023). Modulating the expression levels of these transcription factors could broadly impact the expression of carotenoid biosynthetic genes, leading to significant improvements in fucoxanthin production. These gene expression changes have been revealed through transcriptome analysis, demonstrating that analyzing the effects of different cultivation conditions on fucoxanthin production could facilitate the development of novel metabolic engineering approaches (Fig. 1).

The introduction of engineered enzymes is an effective strategy for enhancing carotenoid production. For example, CrtZ variants engineered to improve astaxanthin production may also be applicable to fucoxanthin biosynthesis. In Escherichia coli, the fusion of Pantoea agglomerans CrtZ with the glycerol channel protein GlpF for membrane localization enhanced astaxanthin production (Ye et al. 2018). Similarly, CrtZ from Brevundimonas sp. SD212, fused via a hydrophilic linker, increased astaxanthin production by 1.4-fold in E. coli (Nogueira et al. 2019). Lycopene production has also been enhanced through the directed evolution of Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous CrtE and P. agglomerans CrtB (Hong et al. 2019). The activity of PSY, a key rate-limiting enzyme in carotenoid biosynthesis, is highly sensitive to even slight modifications in its amino acid sequence (Zhou et al. 2022). Since the effectiveness of enzyme engineering for fucoxanthin production has not yet been demonstrated, this approach holds great potential for improving fucoxanthin productivity.

Heterologous hosts such as E. coli, S. cerevisiae, and cyanobacteria are fast growing, genetically tractable, and suitable for fermentation-based production. However, successful fucoxanthin production in these systems requires the complete elucidation of its biosynthetic pathway. For carotenoids with well-characterized pathways, such as astaxanthin, metabolic engineering has been extensively applied in Yarrowia lipolytica and S. cerevisiae (Yu et al. 2024). Violaxanthin, a precursor of fucoxanthin, can be produced in S. cerevisiae (Cataldo et al. 2020). In these organisms, IPP is supplied through the mevalonate (MVA) pathway, where engineering efforts have focused on strengthening acetyl-CoA supply and overexpressing MVA pathway genes, such as 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme-A (HMG-CoA) reductase. In the case of yeast carotenoid production, the knockout of the ergosterol biosynthetic gene CYP61 increased astaxanthin titer, indicating that the “block” strategy is also effective for carotenoid production (Yamamoto et al. 2016). Resolving the missing links in the fucoxanthin biosynthetic pathway will likely enable high-level production in heterologous hosts, paving the way for industrial-scale applications in the future.

Author contribution

K.T. conducted the literature review and prepared the figures, the tables, and the manuscript. J.C-W.L. and T.H. revised the manuscript. A.K. supervised the project.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Kobe University. This work was supported by GteX Program Japan Grant Number JPMJGX23B4 and the Program for Forming Japan’s Peak Research Universities (J-PEAKS) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS). This work was also supported by Kobe University Strategic International Collaborative Research Grant (Type B Fostering Joint Research).

Data Availability

All data included in this study are available upon request by contact with the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Anila N, Simon DP, Chandrashekar A, Ravishankar GA, Sarada R (2016) Metabolic engineering of Dunaliella salina for production of ketocarotenoids. Photosynth Res 127(3):321–333. 10.1007/s11120-015-0188-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anjana K, Arunkumar K (2024) Brown algae biomass for fucoxanthin, fucoidan and alginate; update review on structure, biosynthesis, biological activities and extraction valorisation. Int J Biol Macromol 280(Pt 2):135632. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.135632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y, Cao T, Dautermann O, Buschbeck P, Cantrell MB, Chen Y, Lein CD, Shi X, Ware MA, Yang F, Zhang H, Zhang L, Peers G, Li X, Lohr M (2022) Green diatom mutants reveal an intricate biosynthetic pathway of fucoxanthin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 119(38). 10.1073/pnas.2203708119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bertrand M (2010) Carotenoid biosynthesis in diatoms. Photosynth Res 106(1–2):89–102. 10.1007/s11120-010-9589-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleisch R, Freitag L, Ihadjadene Y, Sprenger U, Steingröwer J, Walther T, Krujatz F (2022) Strain development in microalgal biotechnology—random mutagenesis techniques. Life (Basel) 12(7):961. 10.3390/life12070961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao T, Bai Y, Buschbeck P, Tan Q, Cantrell MB, Chen Y, Jiang Y, Liu RZ, Ries NK, Shi X, Sun Y, Ware MA, Yang F, Zhang H, Han J, Zhang L, Huang J, Lohr M, Peers G, Li X (2023) An unexpected hydratase synthesizes the green light-absorbing pigment fucoxanthin. Plant Cell 35(8):3053–3072. 10.1093/plcell/koad116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo VF, Arenas N, Salgado V, Camilo C, Ibáñez F, Agosin E (2020) Heterologous production of the epoxycarotenoid violaxanthin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Metab Eng 59:53–63. 10.1016/j.ymben.2020.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cen SY, Li DW, Huang XL, Huang D, Balamurugan S, Liu WJ, Zheng JW, Yang WD, Li HY (2022) Crucial carotenogenic genes elevate hyperaccumulation of both fucoxanthin and β-carotene in Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Algal Res. 64:102691. 10.1016/j.algal.2022.102691

- Chen D, Li H, Chen J, Han Y, Zheng X, Xiao Y, Chen X, Chen T, Chen J, Chen Y, Xue T (2023) Combined analysis of chromatin accessibility and gene expression profiles provide insight into fucoxanthin biosynthesis in Isochrysis galbana under green light. Front Microbiol 14:1101681. 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1101681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christaki E, Bonos E, Giannenas I, Florou-Paneri P (2013) Functional properties of carotenoids originating from algae. J Sci Food Agric 93(1):5–11. 10.1002/jsfa.5902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui H, Ma H, Cui Y, Zhu X, Qin S, Li R (2019) Cloning, identification and functional characterization of two cytochrome P450 carotenoid hydroxylases from the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. J Biosci Bioeng 128(6):755–765. 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2019.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dambek M, Eilers U, Breitenbach J, Steiger S, Büchel C, Sandmann G (2012) Biosynthesis of fucoxanthin and diadinoxanthin and function of initial pathway genes in Phaeodactylum tricornutum. J Exp Bot 63(15):5607–5612. 10.1093/jxb/ers211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dautermann O, Lyska D, Andersen-Ranberg J, Becker M, Fröhlich-Nowoisky J, Gartmann H, Krämer LC, Mayr K, Pieper D, Rij LM, Wipf HM, Niyogi KK, Lohr M (2020) An algal enzyme required for biosynthesis of the most abundant marine carotenoids. Sci Adv 6(10). 10.1126/sciadv.aaw9183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Diao J, Song X, Zhang L, Cui J, Chen L, Zhang W (2020) Tailoring cyanobacteria as a new platform for highly efficient synthesis of astaxanthin. Metab Eng 61:275–287. 10.1016/j.ymben.2020.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding W, Ye Y, Yu L, Liu M, Liu J (2023) Physiochemical and molecular responses of the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum to illumination transitions. Biotechnol Biofuels Bioprod 16(1):103. 10.1186/s13068-023-02352-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eilers U, Dietzel L, Breitenbach J, Büchel C, Sandmann G (2016a) Identification of genes coding for functional zeaxanthin epoxidases in the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. J Plant Physiol 192:64–70. 10.1016/j.jplph.2016.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eilers U, Bikoulis A, Breitenbach J, Büchel C, Sandmann G (2016b) Limitations in the biosynthesis of fucoxanthin as targets for genetic engineering in Phaeodactylum tricornutum. J Appl Phycol 28:123–129. 10.1007/s10811-015-0583-8 [Google Scholar]

- Englund E, Shabestary K, Hudson EP, Lindberg P (2018) Systematic overexpression study to find target enzymes enhancing production of terpenes in Synechocystis PCC 6803, using isoprene as a model compound. Metab Eng 49:164–177. 10.1016/j.ymben.2018.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galarza JI, Gimpel JA, Rojas V, Arredondo-Vega BO, Henríquez V (2018) Over-accumulation of astaxanthin in Haematococcus pluvialis through chloroplast genetic engineering. Algal Res 31:291–297. 10.1016/j.algal.2018.02.024 [Google Scholar]

- Galasso C, Corinaldesi C, Sansone C (2017) Carotenoids from marine organisms: biological functions and industrial applications. Antioxidants (Basel) 6(4):96. 10.3390/antiox6040096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goss R, Jakob T (2010) Regulation and function of xanthophyll cycle-dependent photoprotection in algae. Photosynth Res 106(1–2):103–122. 10.1007/s11120-010-9536-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goss R, Ann Pinto E, Wilhelm C, Richter M (2006) The importance of a highly active and ΔpH-regulated diatoxanthin epoxidase for the regulation of the PS II antenna function in diadinoxanthin cycle containing algae. J Plant Physiol 163(10):1008–1021. 10.1016/j.jplph.2005.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Græsholt C, Brembu T, Volpe C, Bartosova Z, Serif M, Winge P, Nymark M (2024) Zeaxanthin epoxidase 3 knockout mutants of the model diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum enable commercial production of the bioactive carotenoid diatoxanthin. Mar Drugs 22(4):185. 10.3390/md22040185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao TB, Lu Y, Zhang ZH, Liu SF, Wang X, Yang WD, Balamurugan S, Li HY (2021) Hyperaccumulation of fucoxanthin by enhancing methylerythritol phosphate pathway in Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 105(23):8783–8793. 10.1007/s00253-021-11660-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasunuma T, Takaki A, Matsuda M, Kato Y, Vavricka CJ, Kondo A (2019) Single-stage astaxanthin production enhances the nonmevalonate pathway and photosynthetic central metabolism in Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002. ACS Synth Biol 8(12):2701–2709. 10.1021/acssynbio.9b00280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong J, Park SH, Kim S, Kim SW, Hahn JS (2019) Efficient production of lycopene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by enzyme engineering and increasing membrane flexibility and NADPH production. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 103(1):211–223. 10.1007/s00253-018-9449-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadono T, Kira N, Suzuki K, Iwata O, Ohama T, Okada S, Nishimura T, Akakabe M, Tsuda M, Adachi M (2015) Effect of an introduced phytoene synthase gene expression on carotenoid biosynthesis in the marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Mar Drugs 13(8):5334–5357. 10.3390/md13085334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanamoto A, Kato Y, Yoshida E, Hasunuma T, Kondo A (2021) Development of a method for fucoxanthin production using the haptophyte marine microalga Pavlova sp. OPMS 30543. Mar Biotechnol (NY) 23(2):331–341. 10.1007/s10126-021-10028-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato Y, Inabe K, Hidese R, Kondo A, Hasunuma T (2022) Metabolomics-based engineering for biofuel and bio-based chemical production in microalgae and cyanobacteria: a review. Bioresour Technol 344(Pt A):126196. 10.1016/j.biortech.2021.126196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaw YS, Yusoff FM, Tan HT, Noor Mazli NAI, Nazarudin MF, Shaharuddin NA, Omar AR, Takahashi K (2022) Fucoxanthin production of microalgae under different culture factors: a systematic review. Mar Drugs 20(10):592. 10.3390/md20100592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyota H, Okuda Y, Ito M, Hirai MY, Ikeuchi M (2014) Engineering of cyanobacteria for the photosynthetic production of limonene from CO2. J Biotechnol 185:1–7. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.05.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavaud J, Materna AC, Sturm S, Vugrinec S, Kroth PG (2012) Silencing of the violaxanthin de-epoxidase gene in the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum reduces diatoxanthin synthesis and non-photochemical quenching. PLoS One 7(5):e36806. 10.1371/journal.pone.0036806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ledetzky N, Osawa A, Iki K, Pollmann H, Gassel S, Breitenbach J, Shindo K, Sandmann G (2014) Multiple transformation with the crtYB gene of the limiting enzyme increased carotenoid synthesis and generated novel derivatives in Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous. Arch Biochem Biophys 545:141–147. 10.1016/j.abb.2014.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Li C, Ying LQ, Zhang SS, Chen N, Liu WF, Tao Y (2015) Modification of targets related to the Entner-Doudoroff/pentose phosphate pathway route for methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate-dependent carotenoid biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. Microb Cell Fact 14:117. 10.1186/s12934-015-0301-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Sun H, Wang Y, Yang S, Wang J, Wu T, Lu X, Chu Y, Chen F (2022) Integrated metabolic tools reveal carbon alternative in Isochrysis zhangjiangensis for fucoxanthin improvement. Bioresour Technol 347:126401. 10.1016/j.biortech.2021.126401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Pan Y, Yin W, Liu J, Hu H (2024) A key gene, violaxanthin de-epoxidase-like 1, enhances fucoxanthin accumulation in Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Biotechnol Biofuels Bioprod 17(1):49. 10.1186/s13068-024-02496-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Sun Y, Ramos KR, Nisola GM, Valdehuesa KN, Lee WK, Park SJ, Chung WJ (2013) Combination of Entner-Doudoroff pathway with MEP increases isoprene production in engineered Escherichia coli. PLoS ONE 8(12):e83290. 10.1371/journal.pone.0083290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Wang Y, Tang Q, Kong W, Chung WJ, Lu T (2014) MEP pathway-mediated isopentenol production in metabolically engineered Escherichia coli. Microb Cell Fact 13:135. 10.1186/s12934-014-0135-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Cui Y, Chen J, Qin S, Chen G (2019) Metabolic engineering of Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 to produce astaxanthin. Algal Res 44:101679. 10.1016/j.algal.2019.101679 [Google Scholar]

- Lyu X, Lyu Y, Yu H, Chen W, Ye L, Yang R (2022) Biotechnological advances for improving natural pigment production: a state-of-the-art review. Bioresour Bioprocess 9(1):8. 10.1186/s40643-022-00497-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manfellotto F, Stella GR, Falciatore A, Brunet C, Ferrante MI (2020) Engineering the unicellular alga Phaeodactylum tricornutum for enhancing carotenoid production. Antioxidants (Basel) 9(8):757. 10.3390/antiox9080757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao X, Ge M, Wang X, Yu J, Li X, Liu B, Chen F (2021) Transcriptomics and metabolomics analyses provide novel insights into glucose-induced trophic transition of the marine diatom Nitzschia laevis. Mar Drugs 19(8):426. 10.3390/md19080426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menin B, Lami A, Musazzi S, Petrova AA, Santabarbara S, Casazza AP (2019) A comparison of constitutive and inducible non-endogenous keto-carotenoid biosynthesis in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Microorganisms 7(11):501. 10.3390/microorganisms7110501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nogueira M, Enfissi EMA, Welsch R, Beyer P, Zurbriggen MD, Fraser PD (2019) Construction of a fusion enzyme for astaxanthin formation and its characterization in microbial and plant hosts: a new tool for engineering ketocarotenoids. Metab Eng 52:243–252. 10.1016/j.ymben.2018.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang Y, Duan L, Song B, Cui Y, Liu X, Wang T (2024) A review of fucoxanthin biomanufacturing from Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng 47(12):1951–1972. 10.1007/s00449-024-03039-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J, Yuan JP, Wu CF, Wang JH (2011) Fucoxanthin, a marine carotenoid present in brown seaweeds and diatoms: metabolism and bioactivities relevant to human health. Mar Drugs 9(10):1806–1828. 10.3390/md9101806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perozeni F, Cazzaniga S, Baier T, Zanoni F, Zoccatelli G, Lauersen KJ, Wobbe L, Ballottari M (2020) Turning a green alga red: engineering astaxanthin biosynthesis by intragenic pseudogene revival in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Biotechnol J 18(10):2053–2067. 10.1111/pbi.13364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathod JP, Vira C, Lali AM, Prakash G (2020) Metabolic engineering of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii for enhanced β-carotene and lutein production. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 190(4):1457–1469. 10.1007/s12010-019-03194-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarnaik A, Nambissan V, Pandit R, Lali A (2018) Recombinant Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942 for improved zeaxanthin production under natural light conditions. Algal Res 36:139–151. 10.1016/j.algal.2018.10.021 [Google Scholar]

- Satta A, Esquirol L, Ebert BE, Newman J, Peat TS, Plan M, Schenk G, Vickers CE (2022) Molecular characterization of cyanobacterial short-chain prenyltransferases and discovery of a novel GGPP phosphatase. FEBS J 289(21):6672–6693. 10.1111/febs.16556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada N, Okuda Y, Maeda K, Umeno D, Takaichi S, Ikeuchi M (2020) Astaxanthin production in a model cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 66(2):116–120. 10.2323/jgam.2020.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J, Zhao H, Zhang L, Li Z, Han J, Zhou C, Xu J, Li X, Yan X (2023) The heat shock transcription factor PtHSF1 mediates triacylglycerol and fucoxanthin synthesis by regulating the expression of GPAT3 and DXS in Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Plant Cell Physiol 64(6):622–636. 10.1093/pcp/pcad023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava A, Kalwani M, Chakdar H, Pabbi S, Shukla P (2022) Biosynthesis and biotechnological interventions for commercial production of microalgal pigments: a review. Bioresour Technol 352:127071. 10.1016/j.biortech.2022.127071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Xin Y, Zhang L, Wang Y, Liu R, Li X, Zhou C, Zhang L, Han J (2022) Enhancement of violaxanthin accumulation in Nannochloropsis oceanica by overexpressing a carotenoid isomerase gene from Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Front Microbiol 13:942883. 10.3389/fmicb.2022.942883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Takaichi S (2011) Carotenoids in algae: distributions, biosyntheses and functions. Mar Drugs 9(6):1101–1118. 10.3390/md9061101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K, Bamba T, Kondo A, Hasunuma T (2024) Metabolomics-based development of bioproduction processes toward industrial-scale production. Curr Opin Biotechnol 85:103057. 10.1016/j.copbio.2023.103057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran NT, Kaldenhoff R (2020) Metabolic engineering of ketocarotenoids biosynthetic pathway in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii strain CC-4102. Sci Rep 10(1):10688. 10.1038/s41598-020-67756-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trovão M, Schüler LM, Machado A, Bombo G, Navalho S, Barros A, Pereira H, Silva J, Freitas F, Varela J (2022) Random mutagenesis as a promising tool for microalgal strain improvement towards industrial production. Mar Drugs 20(7):440. 10.3390/md20070440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vavricka CJ, Hasunuma T, Kondo A (2020) Dynamic metabolomics for engineering biology: accelerating learning cycles for bioproduction. Trends Biotechnol 38(1):68–82. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2019.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdoes JC, Sandmann G, Visser H, Diaz M, van Mossel M, van Ooyen AJ (2003) Metabolic engineering of the carotenoid biosynthetic pathway in the yeast Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous (Phaffia rhodozyma). Appl Environ Microbiol 69(7):3728–3738. 10.1128/AEM.69.7.3728-3738.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volke DC, Rohwer J, Fischer R, Jennewein S (2019) Investigation of the methylerythritol 4-phosphate pathway for microbial terpenoid production through metabolic control analysis. Microb Cell Fact 18(1):192. 10.1186/s12934-019-1235-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Wu S, Yang G, Pan K, Wang L, Hu Z (2021) A review on the progress, challenges and prospects in commercializing microalgal fucoxanthin. Biotechnol Adv 53:107865. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2021.107865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Zhou X, Wu S, Zhao M, Hu Z (2023) Transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses revealed regulation mechanism of mixotrophic Cylindrotheca sp. glycerol utilization and biomass promotion. Biotechnol Biofuels Bioprod 16(1):84. 10.1186/s13068-023-02338-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Wang J, Gu Z, Yang S, He Y, Mou H, Sun H (2023b) Altering autotrophic carbon metabolism of Nitzschia closterium to mixotrophic mode for high-value product improvement. Bioresour Technol 371:128596. 10.1016/j.biortech.2023.128596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K, Hara KY, Morita T, Nishimura A, Sasaki D, Ishii J, Ogino C, Kizaki N, Kondo A (2016) Enhancement of astaxanthin production in Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous by efficient method for the complete deletion of genes. Microb Cell Fact 15(1):155. 10.1186/s12934-016-0556-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y, Huang JC (2019) Defining the biosynthesis of ketocarotenoids in Chromochloris zofingiensis. Plant Divers 42(1):61–66. 10.1016/j.pld.2019.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye L, Zhu X, Wu T, Wang W, Zhao D, Bi C, Zhang X (2018) Optimizing the localization of astaxanthin enzymes for improved productivity. Biotechnol Biofuels 11:278. 10.1186/s13068-018-1270-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi Z, Xu M, Magnusdottir M, Zhang Y, Brynjolfsson S, Fu W (2015) Photo-oxidative stress-driven mutagenesis and adaptive evolution on the marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum for enhanced carotenoid accumulation. Mar Drugs 13(10):6138–6151. 10.3390/md13106138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi Z, Su Y, Xu M, Bergmann A, Ingthorsson S, Rolfsson O, Salehi-Ashtiani K, Brynjolfsson S, Fu W (2018) Chemical mutagenesis and fluorescence-based high-throughput screening for enhanced accumulation of carotenoids in a model marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Mar Drugs 16(8):272. 10.3390/md16080272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida E, Kato Y, Kanamoto A, Kondo A, Hasunuma T (2023) Metabolomic analysis of the effect of nitrogen on fucoxanthin synthesis by the haptophyte Pavlova gyrans. Algal Res 72:103144. 10.1016/j.algal.2023.103144 [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida E, Kato Y, Kanamoto A, Kondo A, Hasunuma T (2024) Mixotrophic culture enhances fucoxanthin production in the haptophyte Pavlova gyrans. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 108(1):352. 10.1007/s00253-024-13199-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu B, Ma T, Nawaz M, Chen H, Zheng H (2024) Advances in metabolic engineering for the accumulation of astaxanthin biosynthesis. Mol Biotechnol. 10.1007/s12033-024-01289-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Rao S, Wrightstone E, Sun T, Lui ACW, Welsch R, Li L (2022) Phytoene synthase: the key rate-limiting enzyme of carotenoid biosynthesis in plants. Front Plant Sci 13:884720. 10.3389/fpls.2022.884720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data included in this study are available upon request by contact with the corresponding author.