Short abstract

Accusations of malpractice often end in the courts, damaging the doctor-patient relationship and encouraging defensive practice. In Mexico, an alternative system based on arbitration and conciliation has been effective

The growing number of lawsuits against doctors seems to be related to poor personal communication, unrealistic expectations of performance, the high costs of medical attention, and better informed and more critical patients.1,2 A lucrative industry has developed around this phenomenon. In response, doctors buy expensive insurance, which seriously affects their medical practice, summarised in the concept of “defensive medicine.”3 The practice of defensive medicine includes ordering excessive diagnostic procedures and consultations to minimise the risks of being sued.4 Consequently, the cost of medical care increases, promoting resentment in patients, which in turn favours lawsuits, creating a vicious circle.5

Fear of being sued drives some doctors to additional detrimental actions, such as abandoning risky specialties; refusing to treat seriously ill patients; and using clinical records and informed consent forms as means of legal protection, rather than as medical tools.6-8 Differentiation between complications (an unintentional or adverse reaction that aggravates the original disease) and negligence (failure to exercise a reasonable degree of care) is not always simple and may be interpreted differently by the doctor and the patient or their legal adviser.9

In lawsuits, the legal counsel is confidential, and medical opinion is in some cases given by professionals whose academic background, fairness, and expertise are inadequate.10-12 Accusations are submitted through a penal court, because the sole requirement is the presumption, on the side of the claimant, that a misdeed might have been committed. Cases presented in court may take years to resolve; lawyers are hired for a long time with cumbersome financial investment for the patient and the doctor. Deplorably, in the judicial process the doctor-patient relationship shifts to that of provider-complainer, rendering them irreconcilable enemies.

Mediation and arbitration hastens the resolution of conflicts, are less expensive, and the arbiter might be more knowledgeable about medical issues than a lawyer. Arbitration discourages trivial lawsuits and substantially reduces costs. With arbitration, although the total amount awarded is usually less than that awarded by a judicial court, lawyer contingency fees and court costs are avoided.

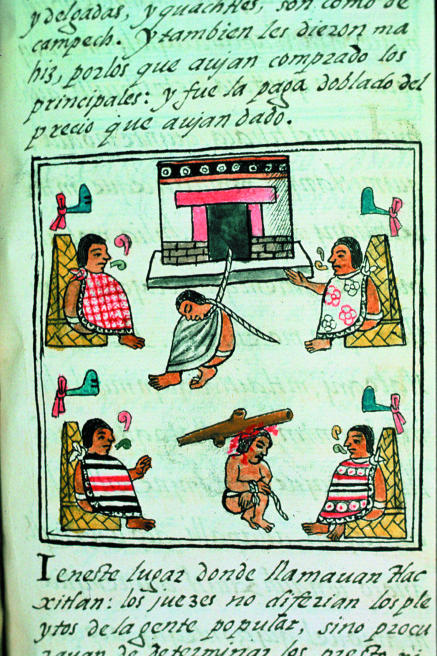

Figure 1.

Aztec codex showing judgment and punishment

Credit: BIBLIOTECA MEDICEA-LAURENZIANA, FLORENCE/BAL

Mexican model of medical arbitration

In June 1996, the Mexican government decided to create, by a presidential decree, a functionally independent national institution attached to the Ministry of Health to arbitrate in cases of medical malpractice. All the staff and reviewers are entirely paid by the government. The main goal of this institution is the specialised attention to conflicts between doctors and patients using alternative forms of resolution of controversies. The words conciliation and arbitration were used as paradigms that equally combine legal and medical expertise; it is called the Comisión Nacional de Arbitraje Medico (Conamed) [National Commission of Medical Arbitration].13

Box 1: Results of Conamed interventions (2001-3)

14 968 dissents admitted

10 999 (73%) solved within 48 hours through specialised consultancy or immediate intervention

3969 (27%) had conciliation-arbitration

2118 (53%) were solved, 2037 at conciliation and 81 at arbitration

1851 (47%) did not reach reconciliation; 562 (14%) left the process, and many of the remaining 1289 (33%) probably went to court

According to the presidential decree, Conamed has jurisdiction to offer advice and information on the rights and obligations of users and to receive, investigate, and oversee complaints concerning potential irregularities of medical care. When the causal link is shown and the doctor is found responsible,13 he or she is obliged to make reparations for the damage caused (by negligence, inexperience, or deceit). In addition, Conamed, as an official institution sponsored entirely by the government, has credibility in the judicial system for expert opinion and can act as a referee and pronounce verdicts or medical opinions requested by judges.13

To resolve a conflict through either conciliation or arbitration requires the will of both participants, that the case not be in judicial process, and that the purpose not be exclusively the legal punishment of the doctor. Conamed is not a judicial authority; it cannot sanction penalty as it only promotes damage reparations in the civil environment.13 Agreements are reached without recourse to the judicial authority. Withdrawal of the patient from the process is possible at any time. The procedure is confidential and impartial.

When a complaint is filed, a quick initial analysis is made to identify whether it should be admitted formally. If the complaint is not because of malpractice, but because of refusal of medical attention or administrative inefficiencies, specialised advice is offered.13 After technical and medical analysis, which include the opinion of the accused doctor, the contenders are invited to the first part of the process—the conciliatory stage. If successful, a conciliatory agreement formalising the arrangement is signed. If conciliation is unsuccessful, the case is passed to the arbitration area.13 Arbitration ends when a sentence is issued that has the effect of matter adjudged.14-16 Conciliation is not a judicial substitute but an alternative. Conamed is aware of the expiration times for judicial action imposed by the law, and the patient is informed so that he or she can start judicial proceedings. Once the arbitrational contract is signed by both sides, however, it is considered a judicial substitute, and the case cannot be taken to a tribunal. This guarantees the arbitral procedure. The documents produced by Conamed can be taken to further court procedures. Conamed has gained prestige among the judiciary, and its opinions and conclusions are widely respected. Mexico's supreme court recently ruled, however, that Conamed has independency of jurisdiction in the resolution of cases but the possibility of legal protection against any resolution was granted.

Arbitration is done by exhaustive evaluation by doctors and lawyers who specialise in medical arbitration, supported by an independent consultancy of professionals contracted for each case through peer review. Lay people do not participate in the process. Referees are academics from medical institutions and universities selected by the academic board of Conamed by considering their expertise, academic background, impartiality in the specific case, and up to date knowledge in the particular branch of the medical specialty involved.13

When evidence of malpractice is found, either because of negligence or inexperience,13 damages are monetary, in accordance with Mexican employment law.17 Other associated damages and expenses are also covered. Financial payments can be compensation, payment of expenses, or debt cancellation.13,17

Apart from resolution of conflicts, Conamed has gained experience to make recommendations to the academic boards and medical institutions on the frequency and characteristics of complaints to encourage preventive measures.18,19

Conamed promotes wide social information about its mission through public broadcasting on radio and television. It also regularly participates in seminars and workshops in undergraduate and postgraduate educational programmes as well as in university courses for continuing medical education.

Objectivity of the model

In 2001-3, almost 15 000 conflicts were submitted to Conamed (box 1).13 Three quarters of them (73%) were solved within two days via immediate intervention by a specialised consultant or personal contact with the medical institution or with the professional responsible for the patient. A quarter of conflicts (27%) had conciliation-arbitration. Of all cases admitted, 51% were resolved in conciliation, and only 2% went on to arbitration. The remaining cases (47%) were not reconciled; of them, 14% willingly left the process. Many of the remaining unresolved cases probably went to court; but because of the nature of Conamed, the precise figures could not be obtained. Most cases (80%) proceeded from public health services, and a fifth were from private medical care.

Box 2: A case resolved through conciliation

Case

A middle aged patient complained of diffuse moderate abdominal pain and distension for a week. On the day of admission to the hospital the patient presented with vomiting and diaphoresis. Haematic biometry showed leucocytosis; abdominal radiography showed diffuse intestinal distension. On physical examination, abdominal pain was more apparent at palpation of the right upper quadrant. Gastric endoscopy and ultrasonography of the gallbladder were normal; the latter found dubious evidence of microliliasis. Diagnosis of acute cholecystitis was made on clinical grounds and cholecystectomy was done the same day. Histopathological study showed chronic cholecystitis. There were no complications after surgery.

Complaint to Conamed

The surgeon did unnecessary surgery, as histological examination of the specimen showed no signs of acute disease. Another doctor diagnosed the patient as having hiatal hernia and gastric reflux; with this doctor's treatment, the patient's symptoms improved.

Conamed intervention

Both sides met with medical specialists and lawyers from Conamed. The patient's complaint was heard and the surgeon gave an informal explanation of his performance, supported by medical references. The professionals from Conamed concluded that there were no sufficient elements to find malpractice because, despite the absence of evidence of acute exacerbation of the inflammatory disease, there were clear findings of chronicity that supported surgery. Thus, operating offered a preventive benefit. It is important to stress the fact that, at this stage, the arguments are mostly conciliatory. The patient accepted the technical explanations, and Conamed, with the consent of both sides, ended the procedure as “conciliated”; they signed an agreement that had the character of adjudged matter.

Of 2118 disputes resolved by either conciliation or sentence, 1519 (72%) were resolved by assuming commitment for continuing medical treatment or by broadening the stages of medical care. For the remaining 599 (28%) complaints, the resolution was through financial payment, in total $2.9m (£1.9m; €2.3m). From all complaints solved through conciliation agreement or by sentence, no medical malpractice was found in 1398 cases (66%). Evidence of malpractice was found in the other 720 cases (35%). Arbitration took on average three to six months for conciliation and 15 months for sentencing. The length of the process depended on mutual agreement with the terms of the final document.

In many cases complaints are simple, but they may escalate if not promptly resolved. An example of this was a patient who came to Conamed because his doctor asked for a computed tomography scan. At the hospital, the appointment was given two months later, the patient felt that the disease (possibly a tumour) may progress. Staff from Conamed intervened, and the complaint was resolved the same day. The service has encouraged some patients who might not normally complain to do so, however. But that might be a good thing for improving medical institutions.

Summary points

Methods for resolving complaints of medical negligence without recourse to the courts are important

In Mexico about two thirds of cases are resolved outside the courts

Most patients and doctors who have participated in the process were satisfied

The system is faster, less expensive, and less damaging than using the courts

The system helps to maintain mutual trust between patients and doctors and might diminish the practice of defensive medicine

In 2002-3, 5572 patients and doctors were voluntarily and anonymously surveyed to investigate user satisfaction with Conamed. The interviewees responded at different stages of the process, evaluating waiting time, impartiality, and personal attention. Overall, 97% rated the quality of service as good or excellent.13

Discussion

Alternative methods for resolution of controversies, which do not imply the compulsory intervention of the judicial authority, have been included in the Mexican legislation.13 These alternative means have been recommended by different authors.10-12,20 For the medical profession, Conamed encourages tolerance and conciliation and provides a beneficial alternative to judicial procedures, which inhibit defensive medicine and the growth of the litigious industry (table).2,21 The procedures have flexibility for reaching solution of differences, which are usually negotiated, and the motivation of one of the parts is not used as prejudice against the other. The good faith principle is enough in many cases for reaching conciliation. The lack of formality results in faster resolution than in most judicial cases.

Table 1.

Judicial process and conciliation-arbitration for resolving medical malpractice

| Characteristic | Judicial process | Conciliation-arbitration |

|---|---|---|

| Willingness of both sides | No | Yes |

| Financial costs | High | Low |

| Time of resolution | Years | Months |

| Impartiality | Fair | Yes |

| Confidentiality | No | Yes |

| Feuds | Yes | No |

| Peer reviewed | No | Yes |

| Generates defensive medicine | Yes | No |

| Solves as adjudged matter | Yes | Yes |

| Judicial procedure | Heterocompositive | Autocompositive |

Because Conamed is a government supported institution, with no commercial interests of any kind and with total autonomy, the procedures are complementary and easy.13 A wide campaign of promotion, through the media, has given lay people awareness of its existence and reduced the number of people taking cases to the courts.

Different methods for resolving conflicts have been investigated in New Zealand, England, the United States, Italy, and Ireland.22-25 In Mexico, Conamed has worked uninterruptedly since 1996; the experience obtained has allowed constant improvements in procedures and performance of the medical and legal staff to attain a mature operative outline and promote efficiency.

Before the creation of Conamed, no systematic review of the annual trends of medical complaints and litigation in Mexico had been reported. One additional advantage of Conamed is the systematic analysis of these trends. The model has led to the creation of state commissions, analogous to Conamed, in 24 of 31 Mexican states. A council was recently created with the participation of the directors from all commissions. A long term goal would be that the local commissions work mostly on the conciliatory stage and Conamed on the arbitration. Other countries could benefit from the Mexican experience.13

Contributors and sources: Both authors wrote the article. CT-T provided the numerical data, table, boxes, and case study. JS corrected the manuscript. CT-T has been appointed by the health authorities as national commissioner for more than four years. JS participated as adviser to the board during his term as president of the National Academy of Medicine. This article arose from mutual discussions. Both authors are guarantors.

Funding: Comision Nacional de Arbitraje Medico and the Instituto Nacional de Neurología y Neurocirugía.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Mohr JC. American medical malpractice litigation in historical perspective. JAMA 2000;283: 1731-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cockburn J, Pit S. Prescribing behaviour in clinical practice: patients' expectations and doctors' perceptions of patients' expectations: a questionnaire study. BMJ 1997;315: 520-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weingart SN, Wilson RM, Gibberd RW, Harrison B. Epidemiology of medical error. BMJ 2000;320: 774-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Studdert DM, Mello MM, Sage WM, DesRoches CM, Peugh J, Zapert K, et al. Defensive medicine among high-risk specialist physicians in a volatile malpractice environment. JAMA 2005;293: 2609-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tracy TF Jr, Crawford LS, Krizek TJ, Kern KA. When medical error becomes medical malpractice: the victims and the circumstances. Arch Surg 2003;138: 447-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mello MM, Studdert DM, Brennan TA. The new medical malpractice crisis. N Engl J Med 2003;348: 2281-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palmisano DJ. Health care in crisis. Circulation 2004;109: 2933-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walsh P. We must accept that health care is a risky business. BMJ 2003;326: 1333-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joint Economic Committee, United States Congress. Liability for medical malpractice: issues and evidence. Washington, DC: JEC, 2003. www.house.gov/jec/tort/05-06-03.pdf (accessed 27 May 2005). [PubMed]

- 10.Picker BG. Mediation practice guide: a handbook for resolving business disputes. Chicago: American Bar Association Publishing, 1998.

- 11.Ladimer I. Alternative dispute resolution in health care. In: Sanbar SS, Gibofsky A, Fireston MH, Le Blang TR, eds. Legal medicine. 3rd ed. London: Mosby, 1995: 25-40.

- 12.Metzloff TB. The unrealized potential of malpractice arbitration. Spec Law Dig Health Care Law 1997;215: 9-36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Comisión Nacional de Arbitraje Médico. www.conamed.gob.mx (accessed 16 June 2005). (In Spanish.)

- 14.Schmidt MD. No fault is the way to go. Med Econ 2003;80: 71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romano M. Trial and error: medical courts, arbitration systems are among the ideas gaining attention as answers to the malpractice liability crisis. Mod Healthc 2003;33: 26-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fraser JJ Jr, Committee on Medical Liability, American Academy of Pediatrics. Technical report: alternative dispute resolution in medical malpractice. Pediatrics 2001;107: 602-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.México: Ley Federal del Trabajo. www.cddhcu.gob.mx/leyinfo/pdf/125.pdf (accessed 16 Jun 2005). (In Spanish.)

- 18.Tena C, Ruelas E, Sánchez JM, Rivera AE, Moctezuma G, Manuell RG, et al. Derechos de los pacientes en México. Rev Med IMSS (Mex) 2002;40: 523-9. (In Spanish.) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tena C, Ruelas E, Sánchez JM, Rivera AE, Manuell R, Moctezuma G, et al. Derechos de los medicos: experiencia Mexicana para su determinación y difusión. Rev Med IMSS (Mex) 2003;41: 503-8. (In Spanish.) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kinney ED. Malpractice reform in the 1990s: past disappointments, future success? J Health-Politics Policy Law 1995;20: 99-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levinson W, Roter DL, Mullooly JP, Dull VT, Frankel RM. Physician-patient communication: the relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. JAMA 1997;277: 553-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.New Zealand Government. www.moh.govt.nz (accessed 27 May 2005).

- 23.UK Department of Health. www.doh.gov.uk/dhhome.htm (accessed 16 Jun 2004).

- 24.American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Medical Liability. Professional liability coverage for residents and fellows. Pediatrics 2000;106: 605-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jourdan S, Rossi ML, Goulding J. Italy: medical negligent as a crime. Lancet 2000;356: 1268-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]