Abstract

Background

Embarking on a university education is a significant milestone in a person’s life. However, evidence shows that many students face poor sleep quality and academic self-doubt during this period. This study aimed to determine the effect of Orem self-care interventions on sleep quality and the academic self-efficacy of nursing students.

Methods

This quasi-experimental study employed a pre-test and post-test control group design to evaluate the intervention’s effects. The study was conducted between October 23 and November 10, 2023, and included 84 nursing students. The participants were randomly divided into two groups: an intervention group and a control group. The tools used were a demographic questionnaire, an Orem self-care model survey and recognition form, the Zajacova Academic Self-Efficacy Beliefs Questionnaire, and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. The experimental group’s intervention, grounded in Orem’s self-care model, included four sessions, each lasting 30 to 45 min. These sessions addressed self-care principles, techniques related to universal needs (like air, water, food, and excretory processes), and strategies for risk prevention while ensuring a balance between activity and rest. There were no follow-up interventions after the initial training sessions. At the end of the intervention, all students in both groups had completed the study instruments. The data was analyzed using SPSS version 26 software, which included the chi-square test, Independent-samples t-test, Mann-Whitney U test, Paired-samples t-test, and Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Results

The results showed that before the intervention, there was no statistically significant difference in the average total sleep quality score (7.64 ± 2.48 in the experimental group versus 7.42 ± 2.74 in the control group) or academic self-efficacy (148.38 ± 12.10 in the experimental group versus 144.66 ± 10 in the control group) between the two groups. However, after the intervention, there were significant changes in the experimental group’s total sleep quality score (3.80 ± 1.56) and academic self-efficacy score (170.71 ± 10.58) compared to the control group’s total sleep quality score (7.80 ± 2.81) and academic self-efficacy score (149.42 ± 11).

Conclusion

In other words, interventions based on Orem’s self-care positively affect students’ sleep quality and academic self-efficacy. Based on the results, a self-care program based on the Orem model for nursing students can improve their sleep quality and academic self-efficacy. Therefore, it is recommended that this model be used for students in educational environments.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12912-025-02886-4.

Keywords: Orem’s self-care model, Academic self-efficacy, Sleep quality, Nursing students

Introduction

Starting university is a significant milestone in one’s life [1]. However, research indicates that many students struggle to maintain healthy lifestyle habits during this transition. The rigorous demands of academic life can disrupt daily routines, leading to poor lifestyle choices [2]. Student life often comes with increased freedom and less supervision, which can result in lower physical activity and the adoption of unhealthy habits like smoking and drinking, all while juggling numerous leisure activities [3, 4].

Poor sleep quality is prevalent for students as they adapt to the academic environment [4]. Despite sleep’s critical role in academic success and overall well-being, many students prioritize studying and completing assignments over getting enough rest [5]. This neglect often results in sleep disturbances, which can lead to symptoms of anxiety and depression, diminish the quality of life, foster negative views of the educational experience, and increase the risk of burnout syndrome [6].

Nursing students, in particular, experience sleep disturbances due to academic pressures, long study hours, and stressful clinical situations [7]. Research indicates that these disruptions negatively affect their daily behaviors and quality of learning [8]. Insufficient and poor-quality sleep can lead to decreased concentration, memory issues, and reduced problem-solving abilities [9]. Additionally, lack of sleep contributes to increased anxiety, depression [7], and decreased motivation [10], which can have long-term negative consequences on mental and physical health. Various studies have shown that self-care intervention programs can help improve sleep quality [3, 11, 12] and reduce stress [13–15] in university students, including nursing students.

Self-efficacy beliefs, as introduced by Bandura, play a vital role in influencing students’ quality of life and academic performance [16]. Essentially, self-efficacy refers to an individual’s confidence in their ability to succeed in specific tasks [17]. In an academic context, academic self-efficacy pertains to a student’s belief in their capacity to learn, solve problems, and achieve success [18]. This belief serves as a strong motivator, encouraging students to perform at their best and pursue positive outcomes [19]. Higher levels of academic self-efficacy are associated with improved academic performance and greater resilience, often referred to as academic buoyancy [20].

Despite the motivating influence of academic self-efficacy, nursing students face significant hurdles in cultivating this essential belief, particularly in balancing the academic pressures and emotional demands of clinical training [21, 22]. The intense workload, combined with high expectations in clinical settings, often leaves little room for students to practice self-care or effectively manage their well-being. Insufficient support [23] and the struggle to maintain a balance between academic responsibilities and personal health can contribute to low self-efficacy among nursing students [24, 25]. Additionally, the fear of making mistakes in clinical settings can undermine their confidence, leading to anxiety that hinders performance and overall learning [26].

Self-care is a successful method for increasing sleep quality and self-efficacy [27, 28]. However, many students struggle to maintain healthy behaviors such as physical activity, nutrition, and sleep [29, 30]. The Orem Self-Care Model offers a structured framework for addressing these concerns [31], emphasizing the need to educate people about self-care activities, developing tailored care plans, and cultivating supportive relationships [32]. Interventions based on Orem’s approach have been proven to help people manage stress, reduce anxiety and exhaustion, and improve sleep quality [27, 29–33].

This study looks at how a structured nursing intervention based on the Orem Self-Care Model affects nursing students’ sleep quality and academic self-efficacy. It covers both the physical and psychological elements that affect their overall health.

Methods

Design

This quasi-experimental study, which ran from October to November 2023, used a pretest-posttest design with a control group. The intervention was divided into four sessions, each focused on a distinct aspect of self-care.

Participants

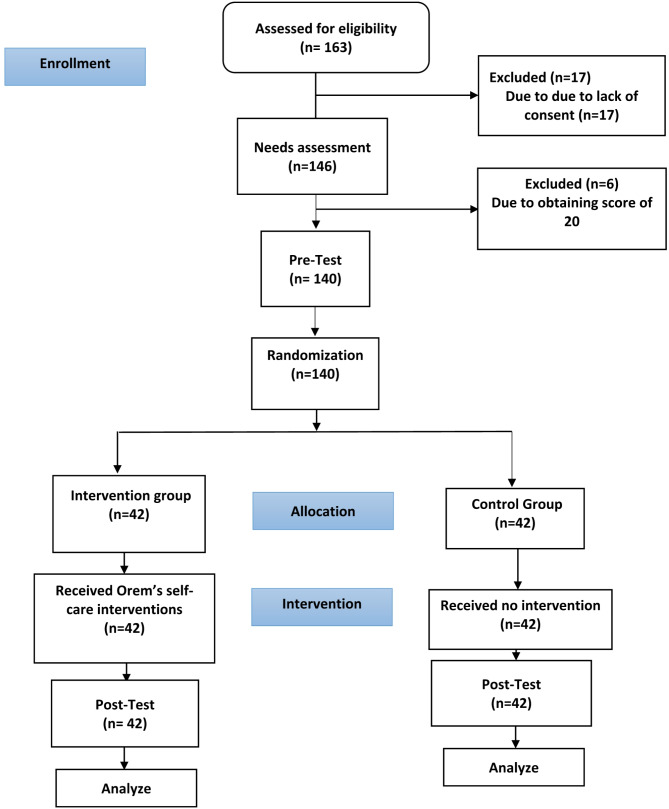

This study included all eligible nursing students at Zanjan University of Medical Sciences aged 18 to 40 years. Participants were chosen through a convenience sampling method, wherein individuals who met the criteria provided informed written consent. The inclusion criteria were no use of drugs or medications that could affect sleep quality or performance, no prior participation in similar training, no self-reported psychiatric issues, and consent to participate. The exclusion criteria included failure to attend training sessions, non-compliance during the intervention, or achieving a perfect baseline score (20 out of 20) to prevent ceiling effects. To ensure a balanced distribution, individuals were randomly allocated to either the intervention or the control group via block randomization. The CONSORT flow chart (Fig. 1) depicts the study flow, including recruiting, allocation, intervention, and data collecting procedures.

Fig. 1.

The study process based on the CONSORT flow diagram

Data collection

The data for this study was collected between October and November 2023. Out of the 163 individuals who met the study’s conditions, 17 were excluded due to lack of consent, and 6 out of the remaining 146 were excluded as they scored a perfect 20 out of 20. The remaining participants were randomly assigned to either the test group (n = 42) or the control group (n = 42).

Intervention

The study involved 84 nursing students who completed initial questionnaires on Orem’s Self-Care Model needs assessment, demographic information, academic self-efficacy, and sleep quality. The intervention group participated in four training sessions over two weeks, each lasting 30 to 45 min and held twice a week.

The topics covered in the sessions were as follows: Session 1 focused on basic needs such as air, water, and nutrition; Session 2 addressed excretory processes and practical strategies for preventing life risks to maintain well-being; Session 3 emphasized the importance of balancing activity and rest, stress management, and creating an optimal sleeping environment; and Session 4 included techniques for balancing social interaction and isolation, along with developmental needs aimed at promoting life processes and preventing harmful conditions. The researcher provided the training in person, thus it is directly applicable to your work (Table 1).

Table 1.

Time table and content of training based on Orem’s self-care model

| Self-care needs | The duration of training | |

|---|---|---|

| Universal self-care needs | Air | 5 min |

| Water | 5 min | |

| Food | 10 min | |

| Care related to excretory processes | 5 min | |

| Prevention of risks related to human life, performance, and well-being | 10 min | |

| Improving growth performance in accordance with genetic and structural characteristics and individual talent within the framework of social and cultural norms | 15 min | |

| Establishing a balance between activity and rest | 45 min | |

| Establishing a balance between seclusion and social interaction | 15 min | |

| Developmental self-care needs | Establishing and maintaining conditions that support life processes and promote evolutionary processes that lead to the promotion and development of humans to higher levels of human structure and maturity | 35 min |

| Health self-care needs | Anticipating and providing care to prevent the occurrence of complications and destructive and harmful conditions that are effective for human development or to overcome and eliminate these complications according to different circumstances | 20 min |

At the conclusion of the intervention, both the intervention and control groups were given the academic self-efficacy and sleep quality questionnaires again. To reduce the risk of contamination, sessions were scheduled at separate times and locations, and unintentional contacts were monitored to assure the study’s integrity.

Instruments

In this study, we used a needs assessment form created to evaluate nursing students’ self-care needs, focusing on universal, developmental, and health-related components as stated by Orem’s self-care model. The form asked questions about vital signs, hydration consumption, diet, oral and dental care, sleep quality, exercise level, elimination status, self-awareness, self-confidence, body image, social interaction, employment, and housing conditions. The form was designed using scientific literature and Orem’s self-care model ideas in mind [34]. To assure its content validity, ten academic members from Zanjan University of Medical Sciences reviewed the form and confirmed its relevancy and comprehensiveness. The form’s dependability was thoroughly assessed using the test-retest method, with 30 nursing students completing the form twice over a two-week period, yielding a high correlation coefficient of 0.86, indicating good consistency.

The form’s total score ranged from 0 to 20, with higher scores reflecting better self-care behaviors and fewer self-care needs. Each area was assigned a specific maximum score: Air (3), Water (2), Food (3), Excretory Processes (3), Activity Level and Exercise (2), Sleep Quality (3), Communication and Social Engagement (2), and Mental Health and Emotional Well-being (2). The total score was divided into five categories to indicate self-care needs: a score of 0–4 signifies a very high need requiring immediate intervention, 5–8 reflects a high need that requires comprehensive strategies, 9–12 indicates a moderate need that calls for targeted interventions, 13–16 suggests a low need where minor improvements could be beneficial, and a score of 17–20 denotes a very low need, indicating excellent self-care with minimal intervention required.

The academic self-efficacy questionnaire used in this study was developed by Zajacova and colleagues [35]. The questionnaire consists of 27 items and measures a student’s confidence in various academic tasks, such as notetaking, asking questions, paying attention in class, computer usage, etc. It is scored using a five-point Likert scale (ranging from “very little” to “very much”), with each item having a value between 0 and 10. The minimum possible score is 0, and the maximum is 270. This scale does not have a cut-off point; a higher score means more self-efficacy. The questionnaire has four subscales: confidence in academic performance in class (items 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13, 16, 18, and 22); confidence in academic performance outside of class (items 1, 3, 4, 5, 15, 17, 25, and 27); confidence in one’s ability to interact with others at the university (items 2, 7, 20, 21, 23, and 26); and confidence in one’s ability to interact with others outside the university (items 12, 14, 19, and 24). In 2011, Shokri and his colleagues established the questionnaire standard in Iran. They used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to confirm the four factors. The authors reported reliability coefficients using Cronbach’s alpha: confidence in academic performance in class (α = 0.88); confidence in academic performance outside of class (α = 0.85); confidence in the ability to interact with others at university (α = 0.83); and confidence in the ability to balance work, family, and university (α = 0.72) [36]. In this study, the tool’s reliability was calculated using Cronbach’s alpha method and was found to be (α = 0.73).

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Questionnaire was developed by Buysse et al. to measure sleep quality and patterns in adults. This questionnaire assesses both good and poor sleep quality. The original questionnaire consists of 9 items, but since question 5 contains 10 subitems, the whole questionnaire has 19 items. Participants are asked to rate each item on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3. The questionnaire included: items that assess the subjective quality of sleep, delay in falling asleep, length of useful sleep duration, sleep sufficiency (the ratio of useful sleep duration to the time spent in bed); sleep disorders (waking up at night), amount of sleep medication consumed, and daily functioning disorders (problems caused by insomnia during the day). A score more than 5 indicates poor sleep quality and severe problems in at least two areas or moderate problems in more than one area. The higher the score is, the poorer the sleep quality. The worst possible score is 23, while the best score is 0. The internal consistency of the questionnaire was obtained through Cronbach’s alpha and was found to be (α = 0.81) [23, 37]. Chehri et al. also standardized the questionnaire in Iran. The authors used confirmatory factor analysis and Cronbach’s alpha to report the following reliability coefficients: mental sleep quality (α = 0.77), sleep delay (α = 0.71), sleep duration (α = 0.69), sleep efficiency (α = 0.79), sleep disturbance (α = 0.79), use of sleeping pills (α = 0.77), and daily functioning (α = 0.07) [38]. In this study, the tool’s reliability was calculated using Cronbach’s alpha method and was found to be (α = 0.81).

Data analyzes

The questionnaire data collected before and after the intervention were entered into SPSS 26 statistical software and analyzed. The normality of the data was checked using the Shapiro‒Wilk test. To compare the homogeneity of the two groups based on quantitative variables, an independent-sample t-test and a paired-sample t-test were used if the data were normally distributed. The Mann‒Whitney U and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used if the data were not normally distributed. The chi-square test and Fisher exact test were used to compare the homogeneity of the two groups based on qualitative variables before the intervention.

Results

Participants’ characteristics

The participants had an average age of 22.39 ± 1.99 years. Of the 84 participants, 45 (53.6%) were male, 78 (92.9%) were single, and 23 (27.4%) were in their 3rd semester of nursing. Additionally, 52 (61.9%) participants were living in a dormitory. The mean and standard deviation of the GPA of the participants were 18.24 ± 0.76. Thirty-five (41.7%) participants had an average economic status, and 24 (28.6%) had an average interest in the field of study. The results of the chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test showed that there was no significant difference between the individual characteristics of the intervention and control groups (P > 0.05, Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of the participants in the intervention and control groups

| Demographic Characteristics |

Intervention Group | Control Group | Sig | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||||

| Gender | Male | 23 (54.74) | 22 (52.39) |

x2 = 0.048 p = 0.827 |

|

| Female | 19 (45.24) | 20 (47.61) | |||

| Semester | 3rd semester | 10 (23.80) | 13 (30.93) |

FET = 1.227 p = 0.890 |

|

| 4th semester | 5 (11.90) | 3 (7.14) | |||

| 5th semester | 11 (26.20) | 9 (21.43) | |||

| 7th semester | 10 (23.80) | 11 (26.20) | |||

| 8th semester | 6 (14.30) | 6 (14.30) | |||

| Marriage status | Single | 38 (92.86) | 40 (95.24) |

FET = 0.718 p = 0.676 |

|

| Married | 4 (7.14) | 2 (4.76) | |||

| Residential status in the dormitory | Resident | 25 (59.52) | 27 (64.29) |

x2 = 0.202 p = 0.653 |

|

| Non-resident | 17 (40.48) | 15 (35.71) | |||

| Financial condition | Poor | 10 (23.81) | 13 (30.95) |

x2 = 0.574 p = 0.751 |

|

| Moderate | 18 (42.86) | 17 (40.48) | |||

| Good | 14 (33.33) | 12 (28.57) | |||

| Level of interest in the academic major | None | 6 (14.29) | 10 (23.80) |

x2 = 1.773 p = 0.777 |

|

| Few | 10 (23.80) | 7 (16.67) | |||

| Moderate | 13 (30.95) | 11 (26.19) | |||

| A significant number | 6 (14.29) | 7 (16.67) | |||

| A large number | 7 (16.67) | 7 (16.67) | |||

| Age | Mean | 22.42 | 22.35 |

t = 0.163 p = 0.871 |

|

| SD | 2.01 | 1.99 | |||

| GPA | Mean | 18.25 | 18.23 |

t = 0.116 p = 0.908 |

|

| SD | 0.75 | 0.77 | |||

Note: Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests was employed to compare participants based on qualitative variables. The Independent t-test was used to examine the difference between two independent groups in the variables Age and GPA

Abbreviations: n, number of participants; SD, standard deviation; GPA, grade point average; X2, Chi-square test; FET, Fisher Exact test; t, test statistic; Sig, statistical significance; p, probability-value

Sleep quality

Before the intervention, the intervention group had identical mean sleep quality scores (7.64 ± 2.48) to the control group (7.42 ± 2.74), with no significant change (p = 0.705). Following the intervention, the intervention group showed significant improvement in sleep quality, with the mean score lowering to 3.80 ± 1.56 (p < 0.001). The control group did not exhibit a significant difference, with their mean score marginally increasing to 7.80 ± 2.81 (p = 0.074). The significant difference in post-intervention scores across the groups suggests that self-care training improved sleep quality in the intervention group (Table 3; Fig. 2).

Table 3.

Comparison of sleep quality in the intervention and control groups before and after the intervention

| Group | Before Intervention | After Intervention | Sig | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Intervention Group (n = 42) | 7.64 | 2.48 | 3.80 | 1.56 |

W= -5.283 p > 0.001 |

| Control Group (n = 42) | 7.42 | 2.74 | 7.80 | 2.81 |

W= -1.778 p = 0.074 |

| Sig |

U = 840.000 p = 0.705 |

U = 186.500 p > 0.001 |

|||

Note The Mann-Whitney U test was employed to examine the difference between two groups in the variable sleep quality. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to assess the significant difference between the two groups in the variable sleep quality

Abbreviations: n, number of participants; SD, standard deviation; W, Wilcoxon signed-rank test; U, Mann-Whitney U test; Sig, statistical significance; p, probability-value

Fig. 2.

Changes in total score of sleep quality in two groups before and after the intervention

Academic self-efficacy

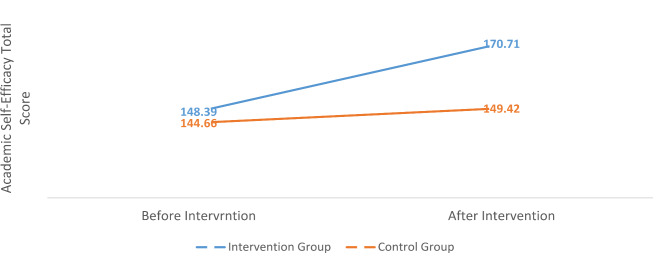

Prior to the intervention, both groups had equal academic self-efficacy scores: the intervention group scored 148.38 ± 12.10 and the control group scored 144.66 ± 10.95 (p = 0.144). Following the session, the intervention group showed a significant increase in self-efficacy scores, reaching 170.71 ± 10.58 (p < 0.001). The control group’s score did not significantly improve, rising to 149.42 ± 11.99, significantly lower than the intervention group’s score (p = 0.078). These data imply that self-care training significantly increased students’ academic self-efficacy in the intervention group, which contrasts with the results of the control group (Table 4; Fig. 3).

Table 4.

Comparison of academic self-efficacy in the intervention and control groups before and after the intervention

| Group | Before Intervention | After Intervention | Sig | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Intervention Group (n = 42) | 148.38 | 12.10 | 170.71 | 10.58 |

p > 0.001 |

| Control Group (n = 42) | 144.66 | 10.95 | 149.42 | 11.99 |

p = 0.078 |

| Sig |

t$= 1.474 p = 0.144 |

t$= 8.625 p > 0.001 |

|||

Note: The independent t-test was used to examine the difference between two independent groups in the variable academic self-efficacy. The paired t-test was employed to assess the significant difference within paired or matched samples in the variable academic self-efficacy

Abbreviations: n, number of participants; SD, standard deviation;  , represents the Paired-Sample test statistic; t$, represents the Independent-Sample test statistic; Sig, statistical significance; p, probability-value

, represents the Paired-Sample test statistic; t$, represents the Independent-Sample test statistic; Sig, statistical significance; p, probability-value

Fig. 3.

Changes in the total score of academic self-efficacy in two groups before and after the intervention

Additional analyses based on age, gender, and semester revealed that younger students (aged 20–22) and those in earlier semesters (third and fourth) showed more significant increases in sleep quality and self-efficacy following the intervention than other subgroups.

Discussion

This study revealed that the average sleep quality score in both the control and test groups was greater than 5, indicating poor sleep quality. These findings are consistent with previous studies that have reported unfavorable sleep quality among students in Iran [39, 40] and outside Iran [41, 42]. For example, a study by Ali Mirzaei et al. revealed that 71% of nursing students had poor sleep quality [39].

The average academic self-efficacy score in the test group before the intervention was average. Previous studies conducted in Iran [43–45] and outside Iran [18, 46] have also reported that academic self-efficacy among students is average. For instance, a study by Farghedani et al. reported that 57.4% of medical students had moderate academic self-efficacy [44].

The results of this study suggest that teaching self-care activities based on the Orem model to nursing students can significantly improve sleep quality. While no studies have precisely measured the effect of Orem’s self-care model on the sleep quality of healthy individuals, studies on the effect of self-care on the sleep quality of sick individuals have shown promising results. For instance, Dahmardeh et al. reported that self-care interventions based on Orem’s model improved sleep quality in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) [47]. Similarly, Aliakbari et al. reported that an intervention based on Orem’s self-care model improved the sleep quality of patients with MS [39]. Furthermore, Benedetto et al.‘s study showed that individuals with better self-care behaviors had better sleep quality [3].

Although studies using educational interventions based on different approaches have shown the ability of such interventions to improve sleep quality, self-care training can be instrumental in improving the hours and quality of sleep by facilitating the planning of daily activity schedules, providing a suitable sleeping environment, and managing stress. This study’s “balance between activity and rest” dimension included instructions for creating a suitable sleeping environment. Li M. et al.‘s study showed that interventions targeting the dormitory environment can improve students’ sleep quality [5]. Additionally, Hershner and O’Brien’s study revealed that a sleep training program significantly improved sleep quality in students [48].

This research indicates that teaching nursing students’ self-care activities based on the Orem model can significantly improve their academic self-efficacy, as observed in other studies. Although researchers have not found a study that measured the effect of Orem’s self-care model on sleep quality and academic self-efficacy, other studies have demonstrated the positive impact of Orem’s self-care model on self-esteem and self-efficacy in various populations. For example, Hashemlo et al. [49] showed that the implementation of Orem’s self-care program improved the self-esteem of older adults living in nursing homes, while Masoudi et al. found that using a self-care program designed based on Orem’s self-care model improved the self-esteem of patients with MS [50]. Additionally, Bozoergzadeh et al. found that using the Orem self-care model improved the self-efficacy of hemodialysis patients [28]. Although different educational interventions, such as group training and short-term educational interventions, have also been shown to improve academic self-efficacy, studies have linked high-stress levels to low academic self-efficacy. Self-care training can help improve academic self-efficacy through the planning of stress management programs. In this study, students were taught ways to reduce stress in the form of developmental needs, such as by “predicting and providing care in order to prevent the occurrence of complications and destructive and harmful conditions that are effective in human development, or by overcoming and eliminating these complications according to different circumstances.” Like this study, Şenocak et al. found that teaching problem-solving solutions to nursing students increases their academic self-efficacy [30]. The study also highlighted solutions related to time management and educational planning in the dimension of “establishing and maintaining conditions that support life processes and promote evolutionary processes that lead to the promotion and advancement of humans to higher levels of human structure.” Additionally, Wernersbach et al. showed that implementing a study skills course increases students’ academic self-efficacy [51].

Additional subgroup analyses by age, gender, and semester were carried out to acquire a better understanding of the intervention’s impact. The data revealed that younger students (ages 20–22) and those in earlier semesters (third and fourth) benefited more significantly from the intervention, notably in terms of improved sleep quality. This means that these groups are more receptive to self-care education because they are more adaptable and open to behavioral change. These findings are consistent with prior research, which found that younger students are more open to lifestyle changes [52, 53].

In comparison to similar research, the outcomes of this intervention are consistent with prior findings that highlight the usefulness of structured self-care programs in improving sleep quality and self-efficacy. For example, Hershner and O’Brien found that focused treatments meant to establish a favorable sleep environment resulted in considerable improvements in student sleep quality [48]. Similarly, Şenocak and Demirkıran found that developing problem-solving abilities among nursing students improved academic self-efficacy, which aligns with our study’s self-care practices [30].

Limitations

This study has several limitations that warrant consideration. First, relying on self-report data could have introduced response bias, as participants may not accurately describe their activities or experiences. Second, while efforts were made to reduce contamination between the intervention and control groups by scheduling sessions in separate locations, there was still a possibility of unintended information transfer among participants. Another significant limitation is the lack of long-term follow-up data to assess the sustainability of improvements in sleep quality and academic self-efficacy.

Despite these limitations, the study retains its validity, particularly through the use of random assignment, which helped control for confounding variables, and efforts to isolate participants, reducing the likelihood of information transfer.

Conclusion

This study showed that training based on the Orem self-care model had significant positive effects on sleep quality and academic self-efficacy of nursing students. After the intervention, the experimental group exhibited significant improvements in sleep quality and academic self-efficacy scores, confirming the effectiveness of the intervention. These changes may be attributed to the students’ heightened awareness of self-care principles and the cultivation of healthy habits related to rest and activity, which ultimately resulted in better sleep quality and increased academic self-confidence. The study clearly demonstrated that self-care training can serve as an effective tool for enhancing students’ mental health and academic performance. These findings emphasize the importance of including self-care training in nursing education programs and suggest that this type of training be offered more widely in different academic courses.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This paper is part of an approved research project by Zanjan University of Medical Sciences (ID: A-11-86-27). We are grateful to the research administration of Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, Zanjan, Iran, who financially supported the study. Moreover, we thank all participants of the study.

Abbreviations

- GPA

Grade Point Average

- MS

Multiple Sclerosis

Author contributions

Kourosh Amini: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision; Mir Amir Hossein Seyed Nazari: Data curation, Writing-Original draft preparation; Farhad Ramezanibadr: Software, Validation; Abdolah Khorami Markani: Reviewing and Editing.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research and Technology Deputy of Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, Zanjan, Iran [grant number A-11-86-27].

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This randomized trial was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zanjan University of Medical Sciences (Approval Code: IR.ZUMS.REC.1402.172). We confirm that all experiments involving human participants were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all nursing student participants prior to their involvement in the study. Participants were assured that their information would remain confidential, and the principle of anonymity was strictly upheld throughout the trial. Participation in the surveys was voluntary, and no compensation was provided. Additionally, the participants’ academic standing was not affected by their decision to participate or not in the study. There were no direct impacts on any individuals resulting from the trial and its surveys.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Woi PJ, Lu JY, Hairol MI, Ibrahim WN. Comparison of vergence mechanisms between university students with good and poor sleep quality. Int J Ophthalmol. 2024;17(2):353. 10.18240/ijo.2024.02.19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Espínola LR, Serra PR, Bennasar MÀ, Toro MG, Simsic VC, Garcia AC, Ventura GN, Vilagut G, Alayo I, Coma LB, Blasco MJ. Depression and lifestyle among university students: a one-year follow-up study. Eur J Psychiatry. 2024;38(3):2. 10.1016/j.ejpsy.2024.100250 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Di Benedetto M, Towt CJ, Jackson ML. A cluster analysis of sleep quality, self-care behaviors, and mental health risk in Australian university students. Behav Sleep Med. 2020;18(3):309–20. 10.1080/15402002.2019.1580194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marquardt M, Pontis S. 0678 consequences of following the herd: perceptions drive a vicious cycle of poor student sleep habits at an elite university. Sleep. 2023 46(Supplement_1), A298-A298. 10.1093/sleep/zsad077.0678

- 5.Li M, Han Q, Pan Z, Wang K, Xie J, Zheng B, Lv J. Effectiveness of multidomain dormitory environment and roommate intervention for improving sleep quality of medical college students: A cluster randomised controlled trial in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(22):15337. 10.3390/ijerph192215337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perotta B, Arantes-Costa FM, Enns SC, Figueiro-Filho EA, Paro H, Santos IS, Lorenzi-Filho G, Martins MA, Tempski PZ. Sleepiness, sleep deprivation, quality of life, mental symptoms and perception of academic environment in medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21:1–3. 10.1186/s12909-021-02544-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Billingsley SK, Collins AM, Miller M, Healthy Student. Healthy nurse: A stress management workshop. Nurse Educ. 2007;32(2):49–51. 10.1097/01.NNE.0000264333.42577.c6 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Menon B, Karishma HP, Mamatha IV. Sleep quality and health complaints among nursing students. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2015;18(3):363–4. 10.4103/0972-2327.157252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baranwal N, Yu PK, Siegel NS. Sleep physiology, pathophysiology, and sleep hygiene. progress in cardiovascular diseases, progress in cardiovascular diseases. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2023;77:59–69. 10.1016/j.pcad.2023.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sutarti T, Wati DR, Abdul M, Anwar M. Relationship of sleep quality with student learning motivation in nursing academy 17 of Karanganyar. Indian J Public Health Res Dev. 2018;9(12):1410–3. 10.5958/0976-5506.2018.02051.X [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brubaker JR, Swan A, Beverly EA. A brief intervention to reduce burnout and improve sleep quality in medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):345. 10.1186/s12909-020-02263-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drew BL, Motter T, Ross R, Goliat LM, Sharpnack PA, Govoni AL, et al. Care for the caregiver: evaluation of mind-body self-care for accelerated nursing students. Holist Nurs Pract. 2016;30(3):148–54. 10.1097/hnp.0000000000000140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kramer D. Energetic modalities as a self-care technique to reduce stress in nursing students. Holist Nurs Pract. 2018;36(4):366–73. 10.1177/0898010117745436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Younas A. Self-care behaviors and practices of nursing students: review of literature. J J Health Sci. 2017;7(3):137–45. 10.17532/jhsci.2017.420 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slemon A, Jenkins EK, Bailey E. Enhancing conceptual clarity of self-care for nursing students: A scoping review. Nurse Educ Pract. 2021;55:103178. 10.1016/j.nepr.2021.103178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hitches E, Woodcock S, Ehrich J. Building self-efficacy without letting stress knock it down: stress and academic self-efficacy of university students. Int Open J Educ Res. 2022;3:100124. 10.1016/j.ijedro.2022.100124 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foulstone AR, Kelly A. Enhancing academic self-efficacy and performance among fourth year psychology students: findings from a short educational intervention. IJ-SoTL. 2019;13(2):9. 10.20429/ijsotl.2019.130209 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Supriatna E, Manuardi AR. Studi deskripsi Efikasi Diri akademik Pada Siswa Mts Al-Badar. FOKUS (Kajian Bimbingan &. Konseling Dalam Pendidikan). 2022;5(2):162–71. 10.22460/fokus.v5i2.7989 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Permana H, Suwarjo S. Psychodrama techniques to improve academic self-efficacy in madrasah aliyah students. Al-Ishlah: Jurnal Pendidikan. 2022;14(4):6773–82. 10.35445/alishlah.v14i4.2288 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vayskarami H, Mir Darikvand F, Ghara Veysi S, Solaymani M. On the relationship of academic self-efficacy with academic buoyancy: the mediating role of basic psychological needs. J Instruction Evaluation. 2019;12(47):141–58. 10.30495/jinev.2019.670579 [Google Scholar]

- 21.George TP, DeCristofaro C, Murphy PF. Self-efficacy and concerns of nursing students regarding clinical experiences. Nurse Educ Today. 2020;90:104401. 10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han S, Eum K, Kang HS, Karsten K. Factors influencing academic self-efficacy among nursing students during COVID-19: a path analysis. J Transcult Nurs. 2022;33(2):239–45. 10.1177/10436596211061683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahlam M, Shrief WI. Effect of faculty support, and nursing students’ self efficacy, and affective commitment on their academic achievements. Life Sci J. 2013;10:2707–16. [Google Scholar]

- 24.El-Sayed, Mona MM, Marwa A, Abd-Elhami EA, Academic, Motivation. Academic self-efficacy and perceived social support among undergraduate nursing students. Assiut Sci Nurs J. 2021;1(9):76–86. 10.21608/asnj.2021.60460.1112

- 25.Farokhzadian J, Karami A, Forouzi MA. Health-promoting behaviors in nursing students: is it related to self-efficacy for health practices and academic achievement? Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2020;32(3). 10.1515/ijamh-2017-0148 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Chesser-Smyth PA, Long T. Understanding the influences on self-confidence among first-year undergraduate nursing students in Ireland. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69(1):145–57. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06001.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aliakbari F, Moosaviean Z, Masoudi R, Kheiri S. The effect of Orem self-care program on sleep quality, daily activities, and lower extremity edema in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Adv Biomed Res. 2021;10:29. 10.4103/abr.abr_54_20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bozoergzadeh M, Paryad E, Baghaei M, Ehsan Kazemkezhad Leili E. The effect of applying the Orem self-care model on self-efficacy of hemodialysis patients: a clinical trial study. S J Nurs Midwifery Paramedical Fac. 2022;8(1):15–34. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Franz T, Cailor S, Chen AMH, Thornton P, Norfolk M. Improvement of student confidence and competence through a self-care skills multi-course integration. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2020;12(4):378–87. 10.1016/j.cptl.2019.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Şenocak S, Demirkıran F. Effects of problem-solving skills development training on resilience, perceived stress, and self-efficacy in nursing students: a randomised controlled trial. Nurse Educ Pract. 2023;72:103795. 10.1016/j.nepr.2023.103795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li X, Zhang K, Xu D, Xu Y. The effect of Orem’s nursing theory on the pain levels, self-care abilities, psychological statuses, and quality of life of bone cancer patients. Am J Transl Res. 2023;15(2):1438. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Isik E, Fredland NM. Orem’s self-care deficit nursing theory to improve children’s self-care: an integrative review. J Sch Nurs. 2023;39(1):6–17. 10.1177/10598405211050062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fereidooni GJ, Ghofranipour F, Zarei F. Interplay of self-care, self-efficacy, and health deviation self-care requisites: a study on type 2 diabetes patients through the lens of Orem’s self-care theory. BMC Prim Care. 2024;148. 10.1186/s12875-024-02276-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Matarese M, Lommi M, De Marinis MG. Systematic review of measurement properties of self-reported instruments for evaluating self‐care in adults. J Adv Nurs. 2017;73(6):1272–87. 10.1111/jan.13204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zajacova A, Lynch SM, Espenshade TJ. Self-efficacy, stress, and academic success in college. Res High Educ. 2005;46(6):677–706. 10.1007/s11162-004-4139-z [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shokri O, Toulabi S, Ghanaei Z, Taghvaeinia A, Kakabaraei K, Fouladvand K. A psychometric study of the academic self-efficacy beliefs questionnaire. Stud Learn Instruction. 2012;3(2):11–6. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF III, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213. 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chehri A, Brand S, Goldaste N, Eskandari S, Brühl A, Sadeghi Bahmani D, Khazaie H. Psychometric properties of the Persian Pittsburgh sleep quality index for adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(19). 10.3390/ijerph17197095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Alimirzaei R, Azizzadeh FM, Abazari F, Mohammadalizadeh S, Haghdoost A. Sleep quality and some associated factors in Kerman students of nursing and midwifery. Health Dev J. 2015;4(2):146–57. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shamsikhani S, Hekmat PD, Sajadi Hezaveh M, Shamsikhani S, Khorasani S, Behzadi F. Effect of aromatherapy with lavender on quality of sleep of nursing students. J Complement Med. 2014;4(3):904–12. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Almojali AI, Almalki SA, Alothman AS, Masuadi EM, Alaqeel MK. The prevalence and association of stress with sleep quality among medical students. J Glob Health. 2017;7(3):169–74. 10.1016/j.jegh.2017.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sawah MA, Ruffin N, Rimawi M, Concerto C, Aguglia E, Chusid E, Infortuna C, Battaglia F. Perceived stress and coffee and energy drink consumption predict poor sleep quality in podiatric medical students a cross-sectional study. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2015;105(5):429–34. 10.7547/14-082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abusalehi A, Bayat B, Tori NA, Salehiniya H. Assessing condition academic self-efficacy and related factors among medical students. Adv Hum Biol. 2019;9(2):143–6. 10.4103/AIHB.AIHB_90_18 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Farghedani Z, Ghajari H, Barati A, Hayati M, Adeli SH, Mohebi S. Assessment of academic self - efficacy of students of Qom university of medical sciences in 2017–2018. Bimon Educ Strategies Med Sci. 2019;12(3):45–52. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saadat S, Asghari F, Jazayeri R. The relationship between academic self-efficacy with perceived stress, coping strategies and perceived social support among students of university of Guilan. Iran J Med Educ. 2015;15(0):67–78. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Putra AP, Indri HS, Tri S. Hubungan academic self efficacy Dengan Kejadian academic burnout Pada Mahasiswa program studi Farmasi program Sarjana Fakultas Kesehatan Di universitas Harapan Bangs. Community Publishing Nurs. 2022;10(6):598–606. 10.24843/coping.2022.v10.i06.p03 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dahmardeh H, Vagharseyyedin SA, Rahimi H, Amirifard H, Akbari O, Sharifzadeh G. Effect of a program based on the Orem self-care model on sleep quality of patients with multiple sclerosis. Jundishapur J Chronic Disease Care. 2016;5(3):e36764. 10.17795/jjcdc-36764 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hershner S, O’Brien LM. The impact of a randomized sleep education intervention for college students. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14(3):337–47. 10.5664/jcsm.6974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hashemlo L, Hemmati Maslakpak M, Khalkhali HR. The effect of Orem self-care program performance on the self- care ability in elderly. J Urmia Nurs Midwifery Fac. 2013;11(2).

- 50.Masoodi R, Khayeri F, Safdari A. Effect of self-care program based on the Orem frame work on self concept in multiple sclerosis patients. J Gorgan Univ Med Sci. 2010;12(3):37–44. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wernersbach BM, Crowley SL, Bates SC, Rosenthal C. Study skills course impact on academic self-efficacy. J Dev Educ. 2014;13(3):14–33. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Choi J, Health P. A pilot study on RTE food purchasing and food-related behaviors of college students in an urbanized area. Int J Environ Res. 2022;19(6):3322. 10.3390/ijerph19063322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ghali H, Ghammem R, Baccouche I, Hamrouni M, Jedidi N, Smaali H, Earbi S, Hajji B, Kastalli A, Khalifa H, Maagli K, Romdhani R, Halleb H, Jdidi F. Association between lifestyle choices and mental health among medical students during the COVID-19: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(10):e0274525. 10.1371/journal.pone.0274525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.