Abstract

Chondroitin sulfate (CS), which is known to be a neurite-preventing molecule, is a major component of the extracellular matrix (ECM) in the central nervous system (CNS). The CS expression is upregulated around damaged areas. Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress causes neuronal cell death in numerous neurodegenerative diseases. However, the effects of ER stress on glial cells remain to be clarified. The present study examined whether direct ER stress to glial cells can upregulate CS expression in C6 glioma cells and primary cultured mouse astrocytes, and also whether the expression of CS prevents neurite extension. ER stressors tunicamycin (TM) and thapsigargin (TG) significantly increased CS expression in both C6 cells and primary cultured astrocytes, while NO donor sodium nitroprusside (SNP) did not significantly alter the CS expression. The dosage of TM and TG treatment used in this study did not significantly induce cell death but upregulated the ER chaperone molecule Grp78 in C6 glioma cells and primary astrocytes. The ECM of glial cells exposed to ER stress prevented neurite extension in primary cultured mouse cortical neurons, and chondroitinase ABC (ChABC) treatment diminished the inhibitory effect on neurite extension. These findings suggest that direct ER stress to glial cells increases the CS expression, which thus prevents neurite extension.

Keywords: ER stress, Chondroitin sulfate, Astrocytes, Extracellular matrix

Introduction

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is the organelle in which glycosylation and protein folding occur. Some stress conditions lead the accumulation of unfolded and misfolded proteins in the ER lumen, namely ER stress. Such accumulation triggers the unfolded protein response (UPR), including the upregulation of chaperone proteins, such as Bip/Grp78 (Yoshida 2007). When the functions of the ER are severely impaired, then cell death signals including CHOP expression thus occurred (Oyadomari et al. 2004). ER stress has been implicated in some neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease (Katayama et al. 2004; Hoozemans et al. 2005), Parkinson disease (Ryu et al. 2002; Lindholm et al. 2006), and Huntington disease (Momoi et al. 2006). Spinal cord injury has also been reported to induce ER stress signals (Penas et al. 2007). Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by the formation of amyloid plaques, which are extracellular deposit of Amyloid β peptide (Aβ), and Aβ has been reported to induce ER stress-dependent neuronal cell death (Ferreiro et al. 2006). Since Aβ deposition is observed in the extracellular space, glial cells may also be exposed to ER stress condition during neurodegeneration. However, the effects of ER stress on glial cells have not yet been addressed in comparison to the neurons.

Chondroitin sulfate glycosaminoglycans (CS-GAGs) are long linear sugar chains constructed with repeating disaccharide units of glucronic acid and N-acetylgalactosamine (-4 GlcAβ 1-3 GalNAcβ 1-) with or without sulfation. The sulfation patterns define the type of CS, such as CS-A, -C, -D, and -E (Sugahara et al. 2003). These sulfation patterns are thought to correlate with the functions of CS chains (Oohira et al. 2000). CS glycosaminoglycan chains bind to core proteins, thereby producing, chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs), which are the major component of the extracellular matrix (ECM). The ECM of the central nervous system (CNS) is composed of relatively small amounts of fibrous proteins and high amounts of GAGs (Galtrey et al. 2007; Novak et al. 2000). Certain neurons are associated with specialized ECM called perineuronal nets (PNNs), which are mainly organized with CSPGs (Hagihara et al. 1999; Matsui et al. 1998; Bignami et al. 1993; Carulli et al. 2006; Haunso et al. 1999). PNNs are reported to protect neurons from some types of stress (Miyata et al. 2007). The CSPGs are synthesized by both neurons and glial cells.

CS is generally known to inhibit axonal growth (Busch et al. 2007; Silver et al. 2004). Glial synthesis of CSPGs has been reported to increase after injury (Thon et al. 2000; Asher et al. 2000) in the CNS. The removal of the CS-GAGs using ChABC has been reported to promote axonal regeneration and functional recovery after spinal cord injury (Moon et al. 2001; Bradbury et al. 2002; Caggiano et al. 2005; Barritt et al. 2006). However, a few groups have reported that specific CSs including CS-D and -E have a neurite sprouting activity (Clement et al. 1998, 1999), and CS-GAGs contribute to neuronal stem cell proliferation and differentiation (Siruko et al. 2007). These reports suggest that the total digestion of CS-GAGs may diminish neuronal regeneration in some situations. Therefore, the structure- and region-specific regulation of glial CS expression might thus be crucial for curing neuronal injury. However, the mechanisms of CS-GAG expressions in glial cells remain to be clarified.

The present study investigated whether ER stress associated with neuronal cell death directly stimulates glial CS expression, and also whether ER stress-induced glial CS acts as an inhibitory molecule for neurite extension or axonal regeneration. We demonstrated that tunicamycin (TM) and thapsigargin (TG), well-known ER stressors, upregulate CS synthesis in C6 glioma cells and primary cultured astrocytes, and that these glia-derived CS prevent neurite extension or axonal regeneration in cultured cortical neurons.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

C6 glioma cells, obtained from Cell Resource Center for Biomedical Research, Tohoku University (Japan), and Neuro2a cells, obtained from Health Science Research Resources Bank (Japan), were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (D-MEM, Sigma, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Sigma, USA) at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. Primary cultured mouse astrocytes were prepared from the cortex of embryonic day 18 C57BL/6 mice. The cells were cultured in D-MEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. After 1 week of being cultured in this medium, the cells were passaged, and used as cultured astrocytes. We observed that more than 90% of the cells expressed glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in our culture condition (data not shown). Primary cultured cortical neurons from embryonic day 18 C57BL/6 mice brains were cultured in Neurobasal medium (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 1% B27 supplement (Gibco, USA), 2 mM l-glutamine (Gibco, USA), 100 U/ml Penicillin, and 100 μg/ml Streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. All animal experiments were approved by the University of Yamanashi Animal Care and Use Committee.

Quantitation of CS Expression

CS expression was analyzed by dot blotting. C6 glioma cells and primary astrocytes were treated with TM or TG in D-MEM without serum. After the treatment, the cells were collected and lysed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) with 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (Nacalai, Japan). The protein in the samples was quantified with a protein quantification kit (Dojindo, Japan). The samples (2.5 μg total protein) were spotted onto a Hybond N+, positively charged nylon transfer membrane (Amersham, USA) setting on a dot blotting apparatus (BioRad, USA). The membrane was blocked with 1% BSA in PBS at room temperature (RT) for 30 min. The membranes were incubated with the primary antibodies mouse anti-CS (CS56) antibody (Seikagaku, Japan) or mouse anti-β-actin antibody (Abcam, USA) in PBS for 2 h at RT. After washing, they were then incubated with biotin-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG + IgM (Pierce, USA) for 30 min at RT. The membrane was subsequently treated with streptavidin biotin complex peroxidase kit according to the manufacture’s instruction (Nacalai, Japan). The specific immunoreactivity was developed with an ECL kit (Amersham, USA) and quantified using the computerized imaging program Quantity One (Bio-Rad, USA).

Cell Viability Assay

C6 glioma cells and primary astrocytes were treated with TM or TG. After treatment, the ratio of live/dead cells was analyzed by using the calcein-AM and propidium iodide (PI) staining kit (Dojindo, Japan). The stained cells were observed under fluorescent microscopy.

Western Blotting

The cells were lysed in PBS containing 1% SDS and 1% protease inhibitor cocktail. The protein concentration was quantified by a protein quantification kit (Dojindo). The samples of the control and the treated cells were separated by 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, followed by transfer to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane. The membranes were blocked with 1% skimmed milk in PBS and incubated at 4°C overnight with anti-Grp78 (Santa Cruz, USA), anti-gadd153/CHOP (Santa Cruz, USA), or anti-β-actin (Abcam, USA). After washing, the membranes were incubated with biotin-conjugated secondary antibody (Nacalai, Japan), followed by incubation with a streptavidin biotin complex peroxidase kit (Nacalai). The immunoreactivity was visualized using a peroxidase detection kit (Nacalai) or Western blotting detection ECL reagents (Amersham, USA) and then were quantified using the computerized imaging program Quantity One (Bio-Rad, USA).

Neurite Extension Analysis

C6 glioma cells or primary astrocytes were cultured on the cover slips and treated with 0.5 μg/ml of TM for 24 h. The treated cells and the ECM were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min. The cover slips were incubated with or without 0.1 unit/ml ChABC (Seikagaku, Japan) for digesting CS-GAGs. Primary cultured mouse cortical neurons were seeded onto the cover slips and cultured for 2 days. The neurons were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS. The neurons were stained with mouse anti-β-tubulin-III antibody (Sigma, USA) followed by Alexa fluor 594-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (Molecular Probes, USA). The stained neurons were observed under fluorescent microscopy, and the degree of neurite extension was analyzed with a Kurabo Neurocyte Image Analyzer (Kurabo, Japan). The photographs were taken from three randomly selected fields per cover slip and all experiments were repeated three times.

Sulfation Pattern Analysis of CS Disaccharides

C6 glioma cells were collected and lyophilized. Approximately 2 mg of lyophilized sample was then homogenized in 0.1 ml of acetone, and then the pellet was extracted with 0.1 ml of 0.5% SDS, 0.1 M NaOH, 0.8% NaBH4 for 16 h at RT. Twenty microliters of 1.0 M sodium acetate and 30 μl of 1 M HCl were then added. The solution was filtered, and 20 μl of 1 M HCl was then added to the filtrate. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 8,000g for 10 min at 4°C. Seven hundred microliters of ethanol was added to the supernatant and chilled for 2 h at 0°C, and the crude glycosaminoglycan was collected by centrifugation at 10,000g for 10 min at 4°C. The resulting precipitate was dissolved in 30 μl of 20 mM Tris-acetate buffer (pH 8.0) and digested thoroughly with ChABC (7 unit/ml) at 37°C overnight. The reaction mixtures were dried and derivatized with a fluorophore, 2-aminobenzamide (2AB) by reductive amination. After the excess 2AB reagent was removed by paper chromatography with acetonitrile, the labeled sugars were then extracted with water and dried. Each 2AB-derivatized sample was analyzed by reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) (Shimadzu, Japan) with an Inertsil ODS-3 column (4.6 × 150 mm; GL Science, Japan) The labeled disaccharides were detected and quantified by UV-VIS detection at absorbance 232 nm. The flow rate was 1.0 ml/min, and the analytical temperature was 55°C. The eluents used were A, 1.2 mM tetra-n-butylammonium hydrogen sulfate (TBA); B, 0.2 M sodium chloride and 1.2 mM TBA; C, 100% acetonitrile. The gradient program was 0–20 min, 1% B; 20–25 min, a liner gradient up to 4% B; 25–26 min, a liner gradient up to 10% B; 26–35 min, a liner gradient up to 20% B; 35–37 min, a liner gradient up to 60% B; 37–48 min, 60% B. 0–15 min, 4% C; 15–20 min, a liner gradient up to 12% C; 20–45 min, 12% C; 45–46 min, a liner gradient up to 15% C; 45–55 min, 15% C in A. The total analytical time was 55 min.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was performed by two-way ANOVA followed by either Dunnett’s test or Student–Newman–Keuls test. The differences between means were considered to be significant when P-values were less than 0.05.

Results

ER Stress Increase Glial CS Expression

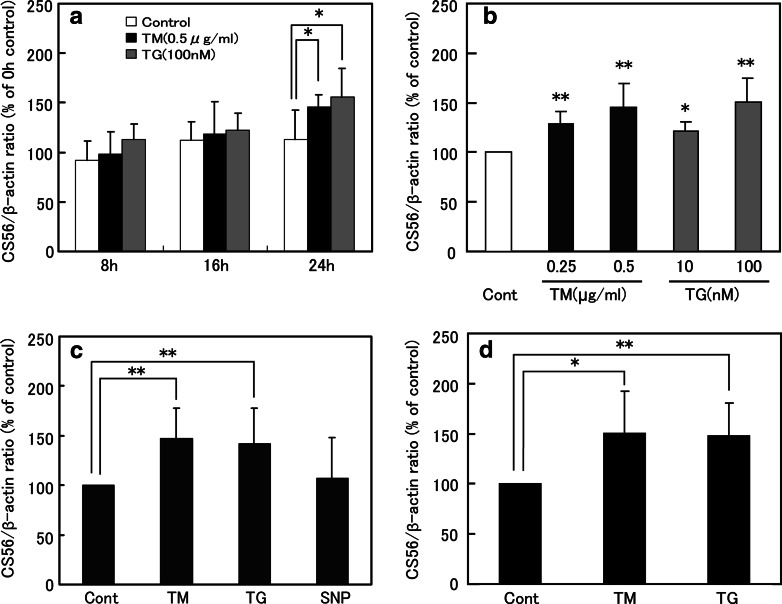

Firstly, the effects of ER stressors TM and TG treatment on glial CS synthesis were analyzed. C6 glioma cells and primary astrocytes were treated with 0.5 μg/ml of TM or 100 nM TG for an appropriate period, and the cell lysates were subjected to dot blot analysis of CS. The relative CS expression levels in 8, 16, and 24 h after TM- or TG-treated C6 glioma cells and untreated control C6 glioma cells in comparison with the untreated control cells at 0 h were (mean ± SD): Control, 92.4 ± 19.7%, 112.5 ± 18.5%, and 113.2 ± 29.3%; TM, 98.3 ± 22.8%, 118.3 ± 33.0%, and 145.7 ± 12.3%; TG, 113.5 ± 15.8%, 121.8 ± 17.1%, and 155.8 ± 28.8% (Fig. 1a). At 24 h, TM or TG significantly increased CS expression in C6 glioma cells (*P < 0.05). The relative CS expression levels in C6 glioma cells treated with 0.25 and 0.5 μg/ml of TM or 10 and 100 nM TG for 24 h were 128.5 ± 12.3%, 145.7 ± 24.0%, 121.0 ± 9.6%, and 150.1 ± 24.3% (mean ± SD) in comparison to the untreated control, respectively (Fig. 1b). These data indicate that TM and TG increased CS expression levels in a dose-dependent manner. To evaluate the effect of oxidative stress on CS expression, C6 cells were treated with a nitric oxide (NO) donor, sodium nitroprusside (SNP). The relative CS expression levels in 0.5 μg/ml of TM, 100 nM TG, or 1 mM SNP for 24 h treated C6 cells were 147.4 ± 30.3%, 141.7 ± 36.0% and 107.2 ± 41.0% (mean ± SD) in comparison with the untreated control, respectively (Fig. 1c). SNP did not significantly alter the CS expression. TM (0.5 μg/ml) and TG (100 nM) also significantly increased CS expression in primary cultured astrocytes, and the relative CS levels were (24 h after treatment); TM, 150.5 ± 42.2%; TG, 148.4 ± 32.3% (mean ± SD) in comparison with the untreated control cells (Fig. 1d). This indicates that ER stressors TM and TG increase CS expression even in primary cultured astrocytes.

Fig. 1.

Effects of ER stress on CS expression in C6 glioma cells and primary cultured astrocytes. CS levels from TM or TG treated cells were quantified by using dot-blotting immunostained with the CS56 antibody. (a) Time course of ER stress-induced CS expression in C6 cells. (b) Dose dependency of TM and TG on the CS expression in C6 cells. (c) Effect of SNP-induced oxidative stress on the CS expression in C6 cells. (d) Effects of TM and TG on the CS expression in primary astrocytes. The results were normalized to β-actin expression. The values are represented as the mean ± SD of the relative percentage of CS expression in comparison to that of the control cells. At least, three independent experiments were performed. **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, ANOVA

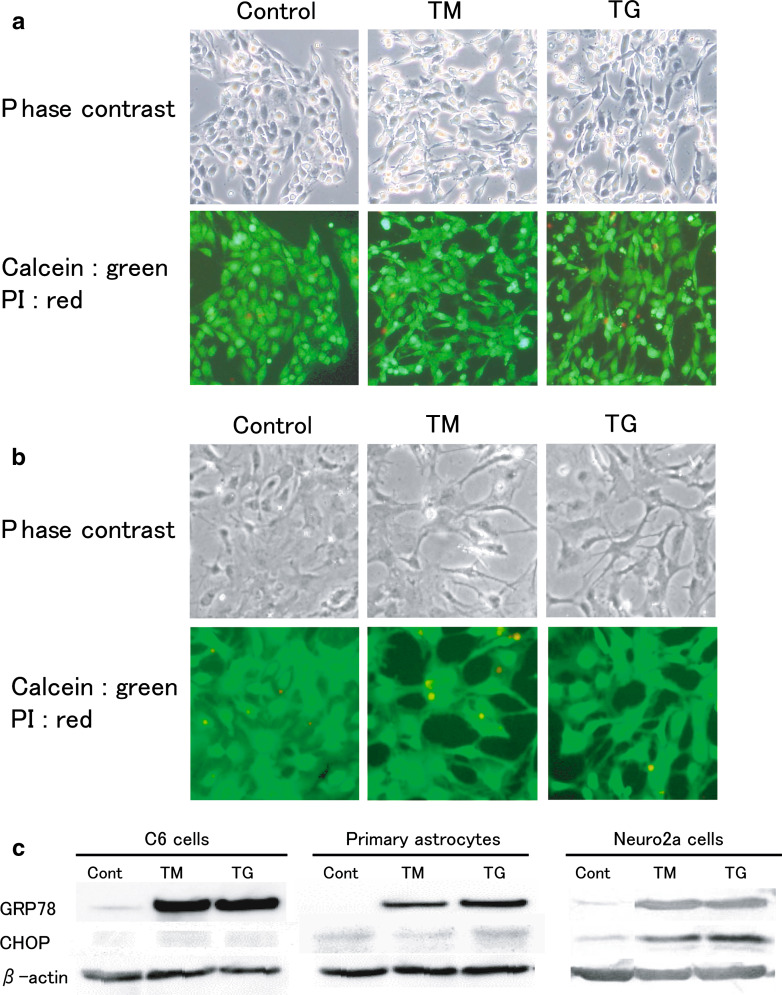

Effect of TM and TG on the Cell Viability and ER Stress Signals

After treatment with TM or TG, the C6 cells and primary astrocytes were stained with calcein-AM and PI. Although stellation like morphological changes were observed, PI stained dead cells were rarely observed (<5%) in both TM- and TG-treated C6 cells (Fig. 2a) and primary astrocytes (Fig. 2b). TM and TG significantly upregulated an ER chaperone protein Grp78 which is a well-known protective molecule expressed during ER stress, while these treatments did not induce the CHOP expression which is reported to be associated with apoptotic signals (1, 2) (Fig. 2c). On the contrary, in mouse neuroblastoma Neuro2a cells, the similar TM- or TG-treatment resulted in both Grp78 and CHOP expressions (Fig. 2c), and caused cell death (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Effects of ER stress on the viability and stress response in C6 glioma cells and primary cultured astrocytes. (a and b) Live/death cell staining by using Calcein-AM (green) and propidium iodide (red) in TM or TG treated C6 cells (a) and primary cultured astrocytes (b). Upper panels show cell morphological observation under phase contrast microscopy, and lower panels show stained cells under fluorescent microscopy. (c) A western blot analysis of Grp78 and CHOP expressions in TM or TG treated C6 cells, primary astrocytes, and Neuro2a cells

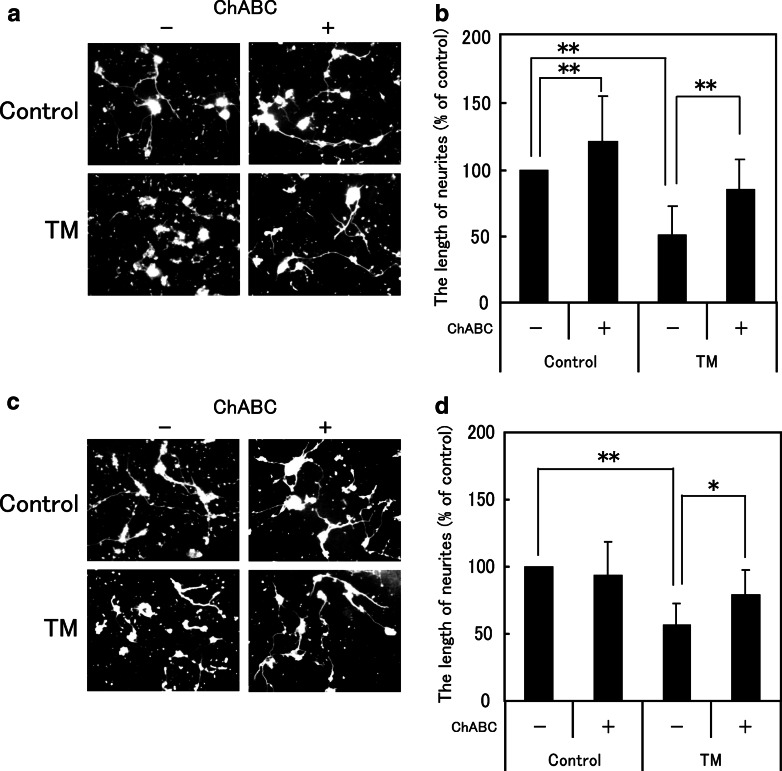

Effects of ER Stress-induced Glial CS on Neurite Extension

The next experiments were designed to determine whether ER stress-induced glial CS has an inhibitory activity on neurite extension. Primary cultured cortical neurons were placed on glial ECM treated with and without (control) TM for 48 h. As shown in Fig. 3a, c, ECM induced by TM-treatment in C6 glioma cells (Fig. 3a) and astrocytes (Fig. 3c) apparently inhibited neurite extension. These inhibitory effects were restored when glial ECMs were treated with ChABC that digests CS molecules. The effects of TM treated glial ECM on neurite extension were quantitatively analyzed, and effects of ChABC on them are shown in Fig. 3b, d. ECM derived from TM-treated glial cells significantly inhibited the neurite extension, which was significantly restored by ChABC, i.e., TM-treated and TM- + ChABC-treated ECM in C6 glioma cells, 50.8 ± 22.0 and 85.0 ± 22.6, respectively, % of the neurons cultured on the ECM of non-treated control C6 cells (Fig. 3b); TM-treated and TM- + ChABC-treated ECM in astrocytes, 56.6 ± 16.1% and 78.6 ± 18.6%, respectively, % of the neurons cultured on the ECM of primary astrocytes (Fig. 3d). The ECM of both C6 cells and primary astrocytes treated with TM significantly reduced the length of neurites, and ChABC digestion significantly diminished the inhibitory effects of the ECM. ChABC treated to untreated glial ECM significantly stimulated neurite extension in C6 cells (120.9 ± 35.0%) but not in primary astrocytes (93.2 ± 25.2%).

Fig. 3.

Effects of ER stress increased CS from C6 glioma cells and primary cultured astrocytes on neurite extension of primary cultured cortical neurons. Neurons were cultured on the ECM from TM treated C6 cells and primary cultured astrocytes with or without ChABC treatment. The neurons were stained with anti-β-tubulin-III antibody, and the length of neurite was analyzed. (a and c) Typical morphology of the neurons cultured on the TM treated C6 cells (a) and primary cultured astrocytes (c). (b and d) An analysis of neurite length of cortical neurons cultured on the ECM of C6 cells (b) and primary cultured astrocytes (d) for 48 h. The relative values of neurite lengths are represented as the mean ± SD compared to the control. At least 150 neurons from three independent experiments were analyzed. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ANOVA

Analysis of the Sulfation Pattern CS from ER Stress Exposed C6 Cells

The effects ER stressors on the CS sulfation pattern in C6 glioma cells were next analyzed. The cells were treated with and without 0.5 μg/ml of TM or 100 nM TG for 24 h. After preparation of CS-GAG, the compositions of the unsaturated disaccharide units were analyzed. The most abundant unit was CS-A both in the presence and absence of ER stress, and other sulfation units were not dramatically altered (Table 1). These data indicate that ER stress does not dramatically alter the sulfation pattern of CS.

Table 1.

Composition of CS disaccharide sulfation pattern derived from control and ER stress exposed C6 glioma cells

| Di-0S | Di-4S (A) | Di-6S (C) | Di-diSD (D) | Di-diSE (E) | Di-triS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 2.0 ± 1.2 | 83.3 ± 1.4 | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 0.3 ± 0.3 | 12.2 ± 1.0 | 0.1 ± 0.3 |

| TM | 6.8 ± 3.1 | 75.9 ± 3.0 | 3.8 ± 0.4 | 0.2 ± 0.4 | 13.3 ± 3.0 | Not detected |

| TG | 6.5 ± 1.9 | 73.3 ± 3.2 | 0.5 ± 0.8 | Not detected | 19.3 ± 4.7 | 0.4 ± 0.6 |

The values are represented as the mean ± SD (%)

Discussion

The present study investigated whether direct ER stress in glial cells increased neurite-preventing CS expression. CSPGs are known to be increased in glial cells after brain injury (Thon et al. 2000; Asher et al. 2000). This includes two possible mechanisms, i.e., CS upregulation via (1) direct ER stress signal in glial cells and (2) indirect inflammatory reactions caused by neuronal cell death. Although there is an extensive literature that brain injury causes astrocytic CS production, little is known about whether ER stress itself directly stimulates CS synthesis in astrocytes or glial cells. To address this, we investigated the effects of TM and TG, which were extensively used ER stressors, on CS expression in C6 cells and primary astrocytes, in parallel with their effects on neurite extension or axonal outgrowth of cortical neurons.

As shown in Fig. 1, both TM and TG increased CS production in C6 glioma cells and cultured astrocytes, suggesting that glial cells possess mechanisms by which ER stress itself upregulates CS expression. With regard to the indirect reactions, cytokines such as transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) could be a key molecule that secondarily upregulates astrocytic CS expression after neuronal death, because (i) TGF-β is upregulated in neurodegenerative diseases (Flanders et al. 1998; Vawter et al. 1996) and (ii) TGF-β1 increases the expression of CSPG in astrocytes (Smith et al. 2005). TGF-β is also expressed in subpopulations of reactive astrocytes around Aβ plaques (Apelt et al. 2001; Cacquevel et al. 2004), thus suggesting that TGF-β also functions as an autocrine signal that induces CS in astrocytes around the injured area. In the present study, however, we did not detect any upregulation of TGF-β1 in glial cells when treated with either TM or TG (data not shown). Instead, TM and TG increased the typical ER stress chaperone molecule Grp78 in glial cells without affecting the cell viability. In addition, oxidative stress induced by NO did not affect CS expression in the glial cells (Fig. 1c). These results strongly suggest that ER stress itself could upregulate glial CS expression in the neurodegenerative or insulted brains. In Alzheimer’s disease, CS upregulation occurs mainly in reactive astrocytes where Aβ plaques are present (Dewitt et al. 1996; Nagele et al. 2004). This raises the possibility that Aβ directly acting on and causing ER stress in astrocytes, might cause CS upregulation independent of Aβ-induced neuronal degeneration (Ferreiro et al. 2006; Kosuge et al. 2006), although we must await further study whether Aβ alone could induce ER stress in astrocytes as well as in neurons.

Glial activation was reported to involve morphological changes, such as the formation of more spherical cell soma and the appearance of extensive cellular processes (Reilly et al. 1998), and Aβ was reported to alter the morphology of primary cultured astrocytes to such reactive shapes (Salinero et al. 1997; Hu et al. 1998). As shown in Fig. 2, treatment with TM and TG induced these morphological changes in both C6 and primary glial cells thus suggesting that ER stress signaling in glial cells is involved in the glial activation including morphological change, and the activation of glial cells contributes to the CS expression. However, specific ER stress signaling which contributes to CS upregulation remains to be clarified.

In the spinal cord injury model, ChABC treatment was reported to promote axonal regeneration and functional recovery (Moon et al. 2001; Bradbury et al. 2002; Caggiano et al. 2005; Barritt et al. 2006), thus indicating that the regulation of CS synthesis plays a crucial role in either neuronal regeneration or the treatment of spinal cord injury. It was recently reported that spinal cord injury induced ER stress and the ER stress responses were cell-type dependent (Penas et al. 2007). The current study demonstrated that ER stress conditions that induce Grp78 and CHOP expressions in neuronal cell line Neuro2a cells, did not increase the CHOP expression in C6 cells and astrocytes (Fig. 2). These observations suggest that the astrocyte-specific ER stress responses contribute to the astrocytic CS upregulation, and the data in this study support this possibility. Although as for an astrocyte-specific ER stress-associated molecule, OASIS has been reported (Saito et al. 2007), and this might be involved in the CS upregulation, we must await further studies to conclude this hypothesis.

Although CS is mainly known to be a molecule that inhibits neurite extension, a few groups reported that it rather stimulates neurite sprouting and extension. For such responses, the involvement of D and E motifs in CS chains is thought to be crucial (Clement et al. 1998, 1999). The variety of CS functions is correlated with its sulfation pattern, and a few sequence motifs have been reported (Sugahara et al. 2003; Oohira et al. 2000). Very recently, CS-E tetrasaccharide was reported to promote neurite outgrowth in dopaminergic neurons (Sotogaku et al. 2007). In the C6 cells and primary astrocytes used in the current study, the sulfation pattern of CS was mainly CS-A unit which is the neurite inhibitory motif (Clement et al. 1998, 1999; Properzi et al. 2005), and ER stress did not cause a dramatic increase in the fraction of CS-D or -E units, both of which are neurite promoting motifs (Clement et al. 1998, 1999; Table 1). This is consistent with our present finding that ER stress-induced CS inhibits but not stimulates neurite extension (Fig. 3).

The involvement of CS in neurodegenerative disease has been reported. CS is known to be present in the amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s disease, and CS was reported to interact directly with Aβ peptide (McLaurin et al. 2000) and protect it from proteolysis (Gupta-Bansal et al. 1995). In addition, CS was reported to protect neuronal cells from neurotoxic prion peptide (Pérez et al. 1998) and Aβ peptide (Woods et al. 1995). PNN, which is a neuronal ECM mainly organized with CS, has also been reported to attenuate Aβ toxicity (Miyata et al. 2007), and CS content in PNN was reported to be reduced in the brain of patients with Alzheimer’s disease (Baig et al. 2005). PNN and CS were also reported to protect neurons from oxidative stress and excitotoxicity (Okamoto et al. 1994a, b; Morawski et al. 2004; Canas et al. 2007). Therefore, glial CS may be upregulated in order to protect the neurons.

This study demonstrated that direct ER stress to C6 cells and primary astrocytes-induced upregulation of CS and reactive morphological changes, and the increased CS inhibited neurite extension. Although the detailed molecular mechanisms remain to be clarified, these data suggest that the regulation of ER stress signaling can control the CS expression in glial cells, and therefore this phenomenon may be applicable for the treatment of neuronal injury.

References

- Apelt J, Schliebs R (2001) β-Amyloid-induced glial expression of both pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in cerebral cortex of aged transgenic Tg2576 mice with Alzheimer plaque pathology. Brain Res 894:21–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asher RA, Morgenstern DA, Fidler PS, Adcock KH, Oohira A, Braistead JE, Levine J M, Margolis RU, Rogers JH, Fawcett JW (2000) Neurocan is upregulated in injured brain and in cytokine-treated astrocytes. J Neurosci 20:2427–2438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baig S, Wilcock GK, Love S (2005) Loss of perineuronal net N-acetylgalactosamine in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol 110:393–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barritt AW, Davies M, Marchand F, Hartley R, Grist J, Yip P, McMahon SB, Bradbury EJ (2006) Chondroitinase ABC promotes sprouting of intact and injured spinal systems after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci 26:10856–10867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bignami A, Perides G, Rahemtulla F (1993) Versican, a hyaluronate-binding proteoglycan of embryonal precartilaginous mesenchyma, is mainly expressed postnatally in rat brain. J Neurosci Res 34:97–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury EJ, Moon LD, Popat RJ, King VR, Bennett GS, Patel PN, Fawcett JW, McMahon SB (2002) Chondroitinase ABC promotes functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Nature 416:636–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch SA, Silver J (2007) The role of extracellular matrix in CNS regeneration. Curr Opin Neurobiol 17:120–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacquevel M, Lebeurrier N, Chéenne S, Vivien D (2004) Cytokines in neuroinflammation and Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Drug Targets 5:529–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caggiano AO, Zimber MP, Ganguly A, Blight AR, Gruskin EA (2005) Chondroitinase ABCI improves locomotion and bladder function following contusion injury of the rat spinal cord. J Neurotrauma 22:226–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canas N, Valero T, Villarroya M, Montell L, Verges J, Garcia AG, Lopez MG (2007) Chondroitin sulphate protects SH-SY5Y cells from oxidative stress by inducing Heme Oxygenase-1 via PI3K/Akt. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 323:946–953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carulli D, Rhodes KE, Brown DJ, Bonnert TP, Pollack SJ, Oliver K, Strata P, Fawcett JW (2006) Composition of perineuronal nets in the adult rat cerebellum and the cellular origin of their components. J Comp Neurol 494:559–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement AM, Sugahara K, Faissner A (1999) Chondroitin sulfate E promotes neurite outgrowth of rat embryonic day 18 hippocampal neurons. Neurosci Lett 269:125–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement AM, Nadanaka S, Masayama K, Mandl C, Sugahara K, Faissner A (1998) The DSD-1 carbohydrate epitope depends on sulfation, correlates with chondroitin sulfate D motifs, and is sufficient to promote neurite outgrowth. J Biol Chem 273:28444–28453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewitt DA, Silver J (1996) Regenerative failure: a potential mechanism for neuritic dystrophy in Alzheimer’s disease. Exp Neurol 142:103–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreiro E, Resende R, Costa R, Oliveira CR, Pereira CM (2006) An endoplasmic-reticulum-specific apoptotic pathway is involved in prion and amyloid-beta peptides neurotoxicity. Neurobiol Dis 23:669–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanders KC, Ren RF, Lippa CF (1998) Transforming growth factor-betas in neurodegenerative disease. Prog Neurobiol 54:71–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galtrey CM, Fawcett JW (2007) The role of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans in regeneration and plasticity in the central nervous system. Brain Res Rev 54:1–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta-Bansal R, Frederickson RC, Brunden KR (1995) Proteoglycan-mediated inhibition of A beta proteolysis. A potential cause of senile plaque accumulation. J Biol Chem 270:18666–186671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagihara K, Miura R, Kosaki R, Berglund E, Ranscht B, Yamaguchi Y (1999) Immunohistochemical evidence for the brevican-tenascin-R interaction: colocalization in perineuronal nets suggests a physiological role for the interaction in the adult rat brain. J Comp Neurol 410:256–264 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haunso A, Celio MR, Margolis RK, Menoud PA (1999) Phosphacan immunoreactivity is associated with perineuronal nets around parvalbumin-expressing neurons. Brain Res 834:219–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoozemans JJ, Veerhuis R, Van Haastert ES, Rozemuller JM, Baas F, Eikelenboom P, Scheper W (2005) The unfolded protein response is activated in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 110:165–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Akama KT, Krafft GA, Chromy BA, Van Eldik LJ (1998) Amyloid-beta peptide activates cultured astrocytes: morphological alterations, cytokine induction and nitric oxide release. Brain Res 785:195–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katayama T, Imaizumi K, Manabe T, Hitomi J, Kudo T, Tohyama M (2004) Induction of neuronal death by ER stress in Alzheimer’s disease. J Chem Neuroanat 28:67–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosuge Y, Sakikubo T., Ishige K, Ito Y (2006) Comparative study of endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced neuronal death in rat cultured hippocampal and cerebellar granule neurons. Neurochem Int 49:285–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindholm D, Wootz H, Korhonen L (2006) ER stress and neurodegenerative diseases. Cell Death Differ 13:385–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui F, Nishizuka M, Yasuda Y, Aono S, Watanabe E, Oohira A (1998) Occurrence of a N-terminal proteolytic fragment of neurocan, not a C-terminal half, in a perineuronal net in the adult rat cerebrum. Brain Res 790:45–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaurin J, Fraser PE (2000) Effect of amino-acid substitutions on Alzheimer’s amyloid-β peptide-glycosaminoglycan interactions. Eur J Biochem 267:6353–6361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata S, Nishimura Y, Nakashima T (2007) Perineuronal nets protect against amyloid β-protein neurotoxicity in cultured cortical neurons. Brain Res 1150:200–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momoi T (2006) Conformational diseases and ER stress-mediated cell death: apoptotic cell death and autophagic cell death. Curr Mol Med 6:111–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon LD, Asher RA, Rhodes KE, Fawcett JW (2001) Regeneration of CNS axons back to their target following treatment of adult rat brain with chondroitinase ABC. Nat Neurosci 4:465–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morawski M, Bruckner MK, Riederer P, Bruckner G, Arendt T (2004) Perineuronal nets potentially protect against oxidative stress. Exp Neurol 188:309–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagele RG, Wegiel J, Venkataraman V, Imaki H, Wang KC, Wegiel J (2004) Contribution of glial cells to the development of amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 25:663–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak U, Kaye AH (2000) Extracellular matrix and the brain: components and function. J Clin Neurosci 7:280–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto M, Mori S, Endo H (1994a) A protective action of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans against neuronal cell death induced by glutamate. Brain Res 637:57–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto M, Mori S, Ichimura M, Endo H (1994b) Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans protect cultured rat’s cortical and hippocampal neurons from delayed cell death induced by excitatory amino acids. Neurosci Lett 172:51–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oohira A, Matsui F, Tokita Y, Yamauchi S, Aono S (2000) Molecular interactions of neural chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans in the brain development. Arch Biochem Biophys 374:24–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyadomari S, Mori M (2004) Roles of CHOP/GADD153 in endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Death Differ 11:381–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penas C, Guzman MS, Verdu E, Fores J, Navarro X, Casas C (2007) Spinal cord injury induces endoplasmic reticulum stress with different cell-type dependent response. J Neurochem 102:1242–1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez M, Wandosell F, Colaco C, Avila J (1998) Sulphated glycosaminoglycans prevent the neurotoxicity of a human prion protein fragment. Biochem J 335:369–374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Properzi F, Carulli D, Asher RA, Muir E, Camargo LM, van Kuppevelt TH, ten Dam GB, Furukawa Y, Mikami T, Sugahara K, Toida T, Geller HM, Fawcett JW (2005) Chondroitin 6-sulphate synthesis is up-regulated in injured CNS, induced by injury-related cytokines and enhanced in axon-growth inhibitory glia. Eur J Neurosci 21:378–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly JF, Maher PA, Kumari VG (1998) Regulation of astrocyte GFAP expression by TGF-beta1 and FGF-2. Glia 22:202–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu EJ, Harding HP, Angelastro JM, Vitolo OV, Ron D, Greene LA (2002) Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the unfolded protein response in cellular models of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci 22:10690–10698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito A, Hino S, Murakami T, Kondo S, Imaizumi K (2007) A novel ER stress transducer, OASIS, expressed in astrocytes. Antioxid Redox Signal 9:563–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salinero O, Moreno-Flores MT, Ceballos ML, Wandosell F (1997) β-Amyloid peptide induced cytoskeletal reorganization in cultured astrocytes. J Neurosci Res 47:216–223 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver J, Miller JH (2004) Regeneration beyond the glial scar. Nat Rev Neurosci 5:146–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirko S, von Holst A, Wizenmann A, Gotz M, Faissner A (2007) Chondroitin sulfate glycosaminoglycans control proliferation, radial glia cell differentiation and neurogenesis in neural stem/progenitor cells. Development 134:2727–2738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GM, Strunz C (2005) Growth factor and cytokine regulation of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans by astrocytes. Glia 52:209–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotogaku N, Tully SE, Gama CI, Higashi H, Tanaka M, Hsieh-Wilson LC, Nishi A (2007) Activation of phospholipase C pathways by a synthetic chondroitin sulfate-E tetrasaccharide promotes neurite outgrowth of dopaminergic neurons. J Neurochem 103:749–760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugahara K, Mikami T, Uyama T, Mizuguchi S, Nomura K, Kitagawa H (2003) Recent advances in the structural biology of chondroitin sulfate and dermatan sulfate. Curr Opin Struct Biol 13:612–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thon N, Haas CA, Rauch U, Merten T, Fassler R, Frotscher M, Deller T (2000) The chondroitin sulphate proteoglycan brevican is upregulated by astrocytes after entorhinal cortex lesions in adult rats. Eur J Neurosci 12:2547–2558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vawter MP, Dillon-Carter O, Tourtellotte WW, Carvey P, Freed WJ (1996) TGFbeta1 and TGFbeta2 concentrations are elevated in Parkinson’s disease in ventricular cerebrospinal fluid. Exp Neurol 142:313–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods AG, Cribbs DH, Whittemore ER, Cotman CW (1995) Heparan sulfate and chondroitin sulfate glycosaminoglycan attenuate beta-amyloid(25–35) induced neurodegeneration in cultured hippocampal neurons. Brain Res 697:53–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida H (2007) ER stress and disease. FEBS J 274:630–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]