Abstract

Oxidative stress has been implicated in a large number of human degenerative diseases, including epilepsy. Levetiracetam (LEV) is a new antiepileptic agent with broad-spectrum effects on seizures and animal models of epilepsy. Recently, it was demonstrated that the mechanism of LEV differs from that of conventional antiepileptic drugs. Objectifying to investigate if LEV mechanism of action involves antioxidant properties, lipid peroxidation levels, nitrite–nitrate formation, catalase activity, and glutathione (GSH) content were measured in adult mice brain. The neurochemical analyses were carried out in hippocampus of animals pretreated with LEV (200 mg/kg, i.p.) 60 min before pilocarpine-induced seizures (400 mg/kg, s.c.). The administration of alone pilocarpine, 400 mg/kg, s.c. (P400) produced a significant increase of lipid peroxidation level in hippocampus. LEV pretreatment was able to counteract this increase, preserving the lipid peroxidation level in normal value. P400 administration also produced increase in the nitrite–nitrate formation and catalase activity in hippocampus, beyond a decrease in GSH levels. LEV administration before P400 prevented the P400-induced alteration in nitrite–nitrate levels and preserved normal values of catalase activity in hippocampus. Moreover, LEV administration prevented the P400-induced loss of GSH in this cerebral area. The present data suggest that the protective effects of LEV against pilocarpine-induced seizures can be mediated, at least in part, by reduction of lipid peroxidation and hippocampal oxidative stress.

KEY WORDS: levetiracetam, pilocarpine, lipid peroxidation, nitrite, nitrate, catalase, glutathione, hippocampus

INTRODUCTION

The epilepsies are a group of clinical syndromes affecting more than 50 million people worldwide (Patel, 2004). The pilocarpine model is a useful animal model to investigate the development of neuropathology of seizures and temporal lobe epilepsy (Cavalheiro et al., 1994; Freitas et al., 2003). In this model, the initial precipitating injury is characterized by a prolonged status epilepticus (SE), which causes neuronal loss and mossy fiber sprouting in hippocampus and spontaneous recurrent seizures (Cavalheiro et al., 1991; Bonan et al., 2000).

Although the mechanism of pilocarpine-induced seizures and SE is not completely understood, it is known that it depends on muscarinic activation and also on enzymatic alterations in several systems (Naffah-Mazzacoratti et al., 2001; Liu et al., 2002). Following the toxicity induced by an initial cholinergic phase, a distinct noncholinergic phase occurs, in which excessive glutamate and aspartate release induces SE in this epilepsy model (McDonough and Shih, 1997).

Oxidative stress is classically defined as a redox unbalance with an excess of oxidants or a defect in antioxidants (Sies, 1985). It has been implicated in a large number of human degenerative diseases, affecting a wild variety of physiological functions such as inflammatory diseases, cancer, and neurological diseases, including epilepsy (Patel, 2004). Reactive oxygen species are normally produced in the brain, such as superoxide, hydroxyl radical, and the hydrogen peroxide (Dugan and Choi, 1999). When produced in excess, reactive oxygen species can cause tissue injury, including lipid peroxidation, DNA damage, and enzyme inactivation (Halliwell and Gutteridge, 1999).

Lipid peroxidation can be induced by many chemicals and in many tissue injuries, and has been suggested as a possible mechanism for the neurotoxic effects of convulsive process (Sawas and Gilbert, 1985; Waltz et al., 2000). Animal studies suggest that epileptic seizures result in free radical production and oxidative damage to cellular proteins, lipids, and DNA (Patel, 2004). Previous reports show that pilocarpine-induced seizures produce several changes in parameters related to generation and elimination of oxygen free radicals (Freitas et al., 2004a,b).

Another important point to discuss is that the role of nitric oxide (NO) in seizures remains controversial since both pro- and anticonvulsant properties are attributed to the molecule depending on the used experimental model (Kirkby et al., 1996). However, several lines of evidence suggest that NO produced by the activation of neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) triggers seizures (Murashima et al., 2002; Rajasekaran et al., 2003).

The insufficient efficacy of modern anticonvulsive drugs used in clinical practice, as well as wide global distribution of epilepsy, makes the design of novel compounds and study of its mechanisms of action very important (Brunbech and Sabers, 2002). Levetiracetam (Keppra®, LEV), the S-enantiomer of a-ethyl-2-oxo-1-pyrrolidine acetamide, is a new antiepileptic agent that has broad-spectrum effects on partial and generalized seizures in several animal models of epilepsy (Löscher and Hönack, 1993; Gower et al., 1995; Klitgaard et al., 1998). Currently, many investigations have been carried out in order to clarify the mechanism of action of this drug.

The clinical effectiveness of LEV has been reported in patients with partial refractory epilepsy (Cereghino et al., 2000; Dooley and Plosker, 2000). Although its mechanism of action remains to be further characterized, it seems unrelated to any modulation of neuronal voltage-gated Na+ or low-voltage-activated Ca2+ (T-type) channels (Zona et al., 2001). However, experimental evidence, both in vitro and in vivo, suggests a role of both calcium channels N-type (Lukyanetz et al., 2002) and GABAergic activity in LEV effects (Poulain and Margineanu, 2002; Rigo et al., 2002). Other investigations show that LEV delays rectifier K+ currents in hippocampal neurons (Madeja et al., 2003) and also it is able to bind to SV2A protein, a synaptic vesicle protein that is an essential protein implicated in the control of exocytosis (Lynch et al., 2004). Klitgaard et al. (2003) demonstrated that LEV is able to counteract seizure-induced alterations in amino acid concentrations and to suppress the synchronization of neuronal spike and burst firing in hippocampus of rats without affecting normal neuronal excitability. Our group has postulated a modulation of the muscarinic cholinergic system by LEV in mice hippocampus on pilocarpine-induced model (Oliveira et al., 2005). These results support a novel mechanism of action for LEV, encouraging study of the drug to try to characterize its antiepileptic properties further.

The present work proposes to investigate whether LEV may alter pilocarpine-induced changes in antioxidant enzymes (catalase and reduced glutathione), in lipid peroxidation level, and nitrite–nitrate formation in mice hippocampus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and Experimental Protocol

Experimentally naive, male Swiss mice, from the Animal House of the Federal University of Ceará, weighing 25–30 g, housed in home cages in a light/dark cycle and with water and food ad libitum, were used. The experiments were performed according to the Guide for the care and use of laboratory, the US Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC (1985).

Experiments were conducted between 8:00 and 10:00 a.m. Animals were acutely injected with LEV 200 mg/kg, i.p., or 0.9% NaCl, the vehicle of dissolution of all used drugs, and, 60 min later, they received pilocarpine hydrochloride, 400 mg/kg, s.c. (P400). Other two groups received only LEV (LEV200, 200 mg/kg, i.p.) or 0.9% NaCl (Control group).

Animals were closely observed for behavioral changes (appearance of peripheral cholinergic signs, such as miosis, piloerection, chromodacryorrhea, diarrhea, masticatory and stereotyped movements), latency to the appearance of the first seizure, SE, and death, for 1 h after the pilocarpine injection. In P400 group, brains were taken just after death; in LEV200 + P400 group, the survivors were killed by decapitation and brains were immediately removed. In control and LEV200 groups, animals were killed 1 h after injections and brains were immediately removed. The brains of all tested groups were dissected on ice to remove hippocampus for neurochemistry assays.

Our results of the observed behavioral alterations were previously shown in Oliveira et al. (2005), when we described that all animals treated with P400 presented peripheral cholinergic signs (miosis, piloerection, chromodacriorrhea, diarrhea, masticatory) and stereotyped movements (continuous sniffing, paw licking, and rearing), followed by motor limbic seizures in 100% (40/40) of the tested animals. The convulsive process persisted and built up to a SE in 90% (36/40) of these mice, leading to death of all animals. LEV200 administration, 60 min before P400, increased the latency to the onset of the first seizure, protected 53% (20/38) of the animals from seizures; reduced the occurrence of SE in 58% (22/38); increased the death's latency by 116%, and protected 61% (23/38) from death as compared to P400. No peripheral cholinergic signs and stereotyped movements were observed as compared to P400. Animals that received injections of 0.9% saline (Control) or LEV200 alone showed no seizure activity.

Enzymatic Assays

Immediately after decapitation, hippocampus was dissected for preparation of homogenates 10% (w/v) in 0.05 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 or EDTA 0.02M (GSH measurements) for the enzymatic assays. The protein concentration was measured according to the method described by Lowry et al. (1951).

Measurements of Lipid Peroxidation

Lipid peroxides formation was analyzed by measuring the thiobarbituric-acid-reacting substances (TBARS) in the homogenates, as previously described by Huong et al. (1998). The samples were briefly mixed with 50 mM potassium phosphate monobasic buffer pH 7.4 and catalytic system of formation of free radicals (FeSO4 0.01 mM and ascorbic acid 0.1 mM), and then incubated at 37°C for 30 min. The reaction was stopped with 0.5 mL of trichloroacetic acid 10%, then the samples were centrifuged (3000 rpm/15 min), the supernatants were retrieved and mixed with 0.5 mL of thiobarbituric acid 0.8%, then heated in a boiling water bath for 15 min and after this period, immediately kept cold in a bath of ice. Lipid peroxidation was determined by the absorbance at 532 nm and was expressed as μmol of malondialdehyde (MDA)/mg of protein.

Nitrite–Nitrate Determination

In order to assess the effects of treatments with respective drugs on nitric oxide (NO) production, nitrite–nitrate levels were determined in the mouse brain homogenates immediately after decapitation in all groups. After centrifugation (800 × g/10 min), the supernatant of homogenate was collected and the production of NO was determined based on Griess reaction (Green et al., 1981; Radenovic and Selakovic, 2005). Briefly, 100 μL of supernatant was incubated with 100 μL of Griess reagent (sulfanilamine in 1% H3PO4/0.1% N-(1-naphthyl)-ethylenediamine dihydrochloride/1% H3PO4/distilled water, 1:1:1:1) at room temperature for 10 min. The absorbance was measured at 550 nm via a microplate reader. The standard curve was prepared with several concentrations of NaNO2 (ranging from 0.75 to 100 μM) and was expressed as μM.

Evaluation of Catalase Activity

Catalase activity was measured by the method that employs hydrogen peroxide to generate H2O and O2 (Maehly and Chance, 1954). The activity was measured by degree of this reaction. The standard assay substrate mixture contained 0.30 mL of hydrogen peroxide in 50 mL of 0.05 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.0. The sample aliquot (20 μL) was added to 980 μL of substrate mixture. After 1 min, initial absorbance was recorded and final absorbance was read after 6 min. The reaction was followed at 230 nm. A standard curve was established using purified catalase (Sigma, MO, USA) under identical conditions. All samples were diluted with 0.1 mmol/ L phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) to provoke an inhibition 50% of diluent rate (i.e., the uninhibited reaction) and results were expressed as μM/min/μg protein.

Measurements of Glutathione (GSH) Levels

GSH levels were evaluated to estimate endogenous defenses against oxidative stress. The method was based on Ellman's reagent (DTNB) reaction with free thiol groups. Hippocampus homogenates 10% (w/v) in EDTA 0.02 M were added to a 50% trichloroacetic acid solution. After centrifugation (3000 rpm/15 min), the supernatant of homogenate was collected and the production levels of GSH were determined as described by Sedlak and Lindsay (1998). Briefly, the samples were mixed with 0.4 M Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.9 and 0.01 M DTNB. GSH level was determined by the absorbance at 412 nm and was expressed as ng of GSH/g wet tissue.

Drugs

Levetiracetam (Keppra®) was obtained from UCB Pharmaceutical Sector (Chemin du Foriest, Belgium). Pilocarpine HCl was purchased from ICN (CA, USA). All other chemicals were of analytical grade.

Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. ANOVA was used for the statistical analysis followed by Student–Newman–Keuls test to identify differences between experimental groups. Values of p < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

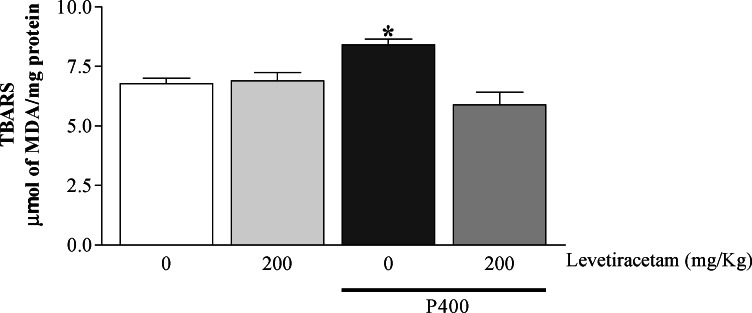

The treatment of the animals only with P400 resulted in high levels of MDA in hippocampus when compared with the control group (only saline 0.9%). However, the treatment with LEV before P400 induced a decrease in the levels of lipid peroxidation as compared to the P400 group. The animals that had received only LEV had not shown alterations in the MDA levels when compared with the controls (Control: 6.79 ± 0.22; P400: 8.41 ± 0.24; LEV200: 6.90 ± 0.34; LEV200 + P400: 5.89 ± 0.54—results were expressed in μmol of malondialdehyde (MDA)/mg of protein) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Levels of TBARS (lipid peroxidation level) in hippocampus of adult mice treated or not with levetiracetam (200 mg/kg, i.p.) and administered or not with P400 (pilocarpine, 400 mg/kg, s.c.). Each bar represents the mean ± SEM, n = 7–10 mice/group. * p < 0.01 as compared to the other groups by ANOVA followed by Student–Newman–Keuls test. Abbreviation: TBARS, tiobarbituric-acid-reacting substances.

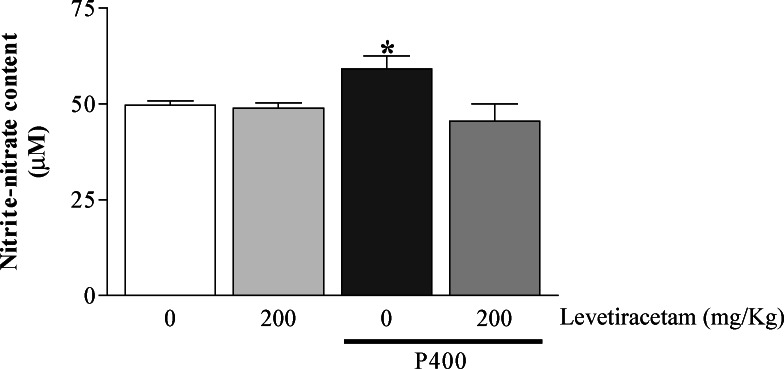

The administration of P400 alone resulted in high levels of nitrite–nitrate in hippocampus when compared to controls. However, when the mice had been managed with LEV before P400, a reduction in the nitrite–nitrate formation was observed when compared to the P400 group. The animals that had received only LEV did not have alteration in the hipocampal levels of nitrite–nitrate when compared with the control group (Control: 49.73 ± 1.04; P400: 59.18 ± 3.42; LEV200: 48.88 ± 1.41; LEV200 + P400: 45.53 ± 4.48—results were expressed in μM) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Content of nitrite–nitrate in hippocampus of adult mice treated or not with levetiracetam (200 mg/kg, i.p.) and administered or not with P400 (pilocarpine, 400 mg/kg, s.c.). Each bar represents the mean ± SEM, n = 5–6 mice/group. * p < 0.05 as compared to the other groups by ANOVA followed by Student–Newman–Keuls test.

In the P400 group, a significant increase of the activity of catalase in hippocampus was observed as compared to the control group. The values of treated animals only with LEV were similar to that observed in the control. The group treated with LEV before P400 had the catalase activity reduced in relation to the alone P400 group, showing that LEV pretreatment was capable to keep catalase activity to normal levels (Control: 37.56±3.26; P400: 59.62±5.46; LEV200: 37.10±3.05; LEV200+P400: 37.88±3.63—results were expressed in μM/min/μg protein) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Catalase activity in hippocampus of adult mice treated or not with levetiracetam (200 mg/kg, i.p.) and administered or not with P400 (pilocarpine, 400 mg/kg, s.c.). Each bar represents the mean ± SEM, n = 17–19 mice/group. * p < 0.01 as compared to the other groups by ANOVA followed by Student–Newman–Keuls test.

The treatment of the mice with P400 resulted in decreased levels of GSH in hippocampus when compared to control groups. LEV administration before P400 prevented the loss of GSH in this cerebral area. Animals treated with LEV alone did not show altered GSH levels when compared to control groups (Control: 1104.00 ± 81.42; P400: 850.80 ± 34.26; LEV200: 1063.01 ± 56.65; LEV200 + P400: 1020.00 ± 57.86—results were expressed in ng/g wet tissue) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Glutathione (GSH) levels in hippocampus of adult mice treated or not with levetiracetam (200 mg/kg, i.p.) and administered or not with P400 (pilocarpine, 400 mg/kg, s.c.). Each bar represents the mean ± SEM, n = 7–10 mice/group. * p < 0.05 as compared to the other groups by ANOVA followed by Student–Newman–Keuls test.

DISCUSSION

Membrane lipid derangements, including lipid peroxidation, have been reported to contribute significantly to paroxysmal membrane malfunction during epileptogenesis. Data in the literature have demonstrated that the enhanced free radical production and oxidative lipid damage occur during seizures and seizure-mediated neuronal injury (Frantseva et al., 2000b; Patel et al., 2001). Although the exact pathophysiological mechanism still needs to be clarified, the whole process can be related to the elevated intracellular concentration of Ca2+. A variety of biochemical processes, including the activation of membrane phospholipases, proteases, and nucleases that cause degradation of membrane phospholipids, proteolysis of cytoskeletone proteins, and protein phosphorylation (Dugan and Choi, 1994) are triggered during seizures. It also is now well established that SE is associated with neuronal damage, particularly in the hippocampus (Costa et al., 2004).

The results of the present study show that P400-induced (pilocarpine, 400 mg/kg, i.p) seizures lead to the increase of the lipid peroxidation in hippocampus of mice. Tejada et al. (2006) showed induced lipid peroxidation by pilocarpine in cortex and hippocampus of rats. In accordance with Freitas et al. (2004b), lipid peroxidation levels and nitrite content are increased during the acute period of P400-induced seizures in adult rats' hippocampus, striatum, and frontal cortex. In the current study, a rise in MDA levels was observed indicating the existence of lipid injury in the hippocampal region, in agreement with previous works (Dal-Pizzol et al., 2000; Frantseva et al., 2000a). These results show a direct evidence of lipid peroxidation during seizure activity that could be responsible for neuronal damage in the hippocampus of rats, during the establishment of P400 model of seizures.

The relationship between SE and oxygen reactive species is well known as the epileptiform activity causing excessive free radical production of reactive oxygen species, a factor believed to be involved in the mechanism leading to cell death and neurodegeneration (Frantseva et al., 2000b; Bellissimo et al., 2001; Freitas et al., 2004a). Our work shows a significant increase in nitrite–nitrate levels in hippocampus after P400 administration. The interaction between NO and free radicals produced during seizures could have potential consequences on the outcome of seizure-induced neuronal injury, since NO may cause neuronal damage in cooperation with other reactive oxygen species (Sah et al., 2002; Rajasekaran, 2005).

Seizures followed by a substantial increase in lipid peroxidation in brain tissue might be diminished by substances with antioxidant properties (Yamamoto and Tang, 1996; Gupta et al., 2001). Previous studies revealed that LEV has a novel spectrum of activity in experimental seizures models (Löscher and Hönack, 1993; Gower et al., 1995; Sharief et al., 1996). The mechanisms underlying the neuroprotective effect of LEV are not well understood. Considering its ability to block Ca2+ influx into the cells (Lukyanetz et al., 2002), it is possible to speculate an activity against the oxidative stress.

Marini et al. (2004) showed that LEV pretreatment was able to blunt brain MDA both in cortex and diencephalon of rats on kainic acid-induced seizures model. Our findings showed that LEV pretreatment before P400 administration was able to reduce lipid peroxidation and nitrite–nitrate levels in hippocampus, which could indicate antioxidant effects of LEV against pilocarpine-induced oxidative stress.

The conversion of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) to H2O can be made by catalase and glutathione peroxidase (that involves the reduced glutathione, a cofactor of this enzyme) (Simonié et al., 2000). An elevation in free radical formation can be accompanied by an immediate compensatory increase in the activities of the free radical scavenging enzyme and such increase can be related to compensatory mechanisms. The SE activates the oxygen reactive species scavenging enzymes, such as superoxide dismutase and catalase, indicating a cellular response to increased oxygen reactive species formation (Ferrer et al., 2000). GSH is an essential tripeptide, and endogenous antioxidant found in all animal cells. It reacts with the free radicals and can protect from singlet oxygen, hydroxide radicals, and superoxide radical damage (Shi et al., 1994).

Our data show enhanced catalase activity and reduced levels of reduced GSH in hippocampus after P400-induced seizures, demonstrating an alteration in antioxidative brain defenses. Freitas et al. (2004a) demonstrated that the P400-induced SE increases catalase activity in the frontal cortex, striatum, and hippocampus of rat's brain. Nascimento et al. (2005) showed an increase in activity of catalase in striatum of young rats, 1 h after P400-induced seizures. Similarly, Tejada et al. (2006) demonstrated an increase in the activity of catalase and other antioxidant enzymes involved in free radical scavenging in rat brain 2 h after pilocarpine treatment. Recently, Gibbs et al. (2006) reported, in an electrical stimulation model of SE, a specific pattern of biochemical change after SE. These data are consistent with the occurrence of oxidative stress and free radical production, including reductions in cellular levels of GSH and reduced activities of enzymes susceptible to oxidative stress within the tricarboxylic acid cycle.

Interestingly, LEV pretreatment preserved catalase activity in normal levels and prevented the loss of reduced GSH in hippocampus. Marini et al. (2004) showed that LEV pretreatment was able to prevent the loss of reduced GSH both in cortex and diencephalon of rats on kainic acid-induced seizures model. These results suggest that LEV could help the brain cells to counteract the pilocarpine-induced reactive oxygen species overproduction and the oxidative damage.

Thus, the results of our present study suggest that lipid peroxidation, nitrite–nitrate formation, and changes in antioxidant brain enzymes are involved in the pathophysiology of pilocarpine-induced seizures and SE. Our data showed that LEV displays activity against pilocarpine-induced oxidative stress in hippocampus, which might contribute to the drug ability to behave as a possible neuroprotective agent. However, LEV could prevent pilocarpine epilepsy by different mechanisms, even if it does not act directly on oxidative stress, since the protection against seizures per se is related to a reasonable decrease of oxidative stress. Further studies may be done to clarify the possible direct antioxidant effects of LEV.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are thankful for the kind donation of levetiracetam from UCB Pharmaceutical Sector. The useful comments of Dr. Alain Matagne and UCB reviewers are also gratefully acknowledged. This work was supported by research grants from the Brazilian National Research Council (CNPq). A.A.O., R.M.F., and L.M.V.A are Fellows from CNPq.

REFERENCES

- Bellissimo, M. I., Amado, D., Abdalla, D. S., Ferreira, E. C., Cavalheiro, E. A., and Naffah-Mazzacoratti, M. G. (2001). Superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase activities and the hydroperoxide concentration are modified in the hippocampus of epileptic rats. Epilepsy Res.46:121–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonan, C. D., Walz, R., Pereira, G. S., Worm, P. V., Battastini, A. M. O., Cavalheiro, E. A., Izquierdo, I., and Sarkis, J. J. F. (2000). Changes in synaptosomal ectonucleotidase activities after status epilepticus induced by pilocarpine and kainic acid. Epilepsy Res.39:229–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunbech, L., and Sabers, A. (2002). Effect of antiepileptic drugs on cognitive function in individuals with epilepsy: A comparative review of newer versus older agents. Drugs62:593–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalheiro, E. A., Fernandes, M. J., Turski, L., and Naffah-Mazzacoratti, M. G. (1994). Spontaneous recurrent seizures in rats: Amino acid and monoamine determination in the hippocampus. Epilepsia35:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalheiro, E. A., Leite, J. P., Bortolotto, Z. A., Turski, W. A., Ikonomidou, C., and Turski, L. (1991). Long-term effects of pilocarpine in rats: Structural damage of the brain triggers kindling and spontaneous recurrent seizures. Epilepsia32:778–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cereghino, J., Biton, V., Abou-Khalil, B., Dreifuss, F., Gauer, L. J., and Leppik, I. (2000). Levetiracetam for partial seizures: Results of a double-blind randomized clinical trial. Neurology55:236–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa, M. S., Rocha, J. B., Perosa, S. R., Cavalheiro, E. A., and Naffah-Mazzacoratti Mda, G. (2004). Pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus increases glutamate release in rat hippocampal synaptosomes. Neurosci. Lett.356:41–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal-Pizzol, F., Klamt, F., Vianna, M. M., Schroder, N., Quevedo, J., Benfato, M. S., Moreira, J. C., and Walz, R. (2000). Lipid peroxidation in hippocampus early and late after status epilepticus induced by pilocarpine or kainic acid in Wistar rats. Neurosci. Lett.291:179–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooley, M., and Plosker, G. L. (2000). Levetiracetam: A review of its adjunctive use in the management of partial onset seizures. Drugs60:871–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugan, L. L., and Choi, D. W. (1994). Excitotoxicity, free radicals, and cell membrane changes. Ann. Neurol.35:17–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugan, L. L., and Choi, D. W. (1999). Hypoxic–ischemic brain injury and oxidative stress. In Siegel, G. J., Agranoff, B. W., Albers, E. W., Fisher, S. K., and Uhler, M. D. (eds.), Basic Neurochemistry: Molecular, Cellular and Medical Aspects, 6th edn, Williams & Wilkins, Lippincott, Baltimore, pp. 722–723. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer, I., Lopez, E., Blanco, R., Rivera, R., Krupinski, J., and Marti, E. (2000). Differential c-Fos and caspase expression following kainic acid excitotoxicity. Acta Neuropathol.99:245–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frantseva, M. V., Perez Velazquez, J. L., Tsoraklidis, G., Mendonca, A. J., Adamchik, Y., Mills, L. R., Carlen, P. L., and Burnham, M. W. (2000a). Oxidative stress is involved in seizure-induced neurodegeneration in the kindling model of epilepsy. Neuroscience97:431–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frantseva, M. V., Velazquez, J. L., Hwang, P. A., and Carlen, P. L. (2000b). Free radical production correlates with cell death in an in vitro model of epilepsy. Eur. J. Neurosci.12:1431–1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas, R. M., Felipe, C. F. B., Nascimento, V. S., Oliveira, A. A., Viana, G. S. B., and Fonteles, M. M. F. (2003). Pilocarpine-induced seizures in adult rats: Monoamine content and muscarinic and dopaminergic receptor changes in the striatum. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Pharmacol. Toxicol. Endocrinol.136:103–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas, R. M., Nascimento, V. S., Vasconcelos, S. M. M., Sousa, F. C. F., Viana, G. S. B., and Fonteles, M. M. F. (2004a). Catalase activity in cerebellum, hippocampus, frontal cortex and striatum after status epilepticus induced by pilocarpine in Wistar rats. Neurosci. Lett.365:102–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas, R. M., Sousa, F. C. F., Vasconcelos, S. M. M., Viana, G. S. B., and Fonteles, M. M. F. (2004b). Pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus in rats: Lipid peroxidation level, nitrite formation, GABAergic and glutamatergic receptor alterations in the hippocampus, striatum and frontal cortex. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav.78:327–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, J. E., Walker, M. C., and Cock, H. R. (2006). Levetiracetam: Antiepileptic properties and protective effects on mitochondrial dysfunction in experimental status epilepticus. Epilepsia47(3):469–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gower, A. J., Hirsch, E., Boehrer, A., Noyer, M., and Marescaux, C. (1995). Effects of levetiracetam, a novel antiepileptic drug, on convulsant activity in two genetic rat models of epilepsy. Epilepsy Res.22:207–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, L. C., Tannenbaum, S. R., and Goldman, P. (1981). Nitrate synthesis in the germfree and conventional rat. Science212:56–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, Y. K., Chaudhary, G., Sinha, K., and Srivastava, A. K. (2001). Protective effect of resveratrol against intracortical FeCl3-induced model of posttraumatic seizures in rats. Methods Find. Exp. Clin. Pharmacol.23:241–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell, B., and Gutteridge, J. M. C. (1999). Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine, Oxford Sci., London. [Google Scholar]

- Huong, N. T., Matsumoto, K., Kasai, R., Yamasaki, K., and Watanabe, H. (1998). In vitro antioxidant activity of Vietnamese ginseng saponin and its components. Biol. Pharm. Bull.21:978–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkby, R. D., Carroll, D. M., Grossman, A. B., and Subramaniam, S. (1996). Factors determining proconvulsant and anticonvulsant effects of inhibitors of nitric oxide synthase in rodents. Epilepsy Res.24:91–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klitgaard, H., Matagne, A., Gobert, J., and Wülfert, E. (1998). Evidence for a unique profile of levetiracetam in rodent models of seizures and epilepsy. Eur. J. Pharmacol.353:191–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klitgaard, H., Matagne, A., Grimee, R., Vanneste-Goemaere, J., and Margineanu, D. (2003). Eletrophysiological, neurochemical, and regional effects of levetiracetam in the rat pilocarpine model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Seizure12:92–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K. J., Liu, S., Morrow, D., and Peterson, S. L. (2002). Hydroethidine detection of superoxide production during the lithium-pilocarpine model of status epilepticus. Epilepsy Res.49:226–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löscher, W., and Hönack, D. (1993). Profile of ucb L059, a novel anticonvulsant drug, in models of partial and generalized epilepsy in mice and rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol.232:147–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry, H., Rosebrough, N. J., Farr, A. L., and Randall, R. J. (1951). Protein measurements with the follin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem.193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukyanetz, E. A., Shkryl, V. M., and Kostyuk, P. G. (2002). Selective blocked of N-type calcium channels by Levetiracetam. Epilepsia43(1):9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, B., Lambeng, N., Nocka, K., Kensel-Hammes, P., Bajjellieh, S. M., Matagne, A., and Fucks, B. (2004). The synaptic vesicle protein SV2A is the binding site for the antiepileptic drug levetiracetam. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.101:9861–9866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madeja, M., Margineanu, D.-G., Gorji, A., Siep, E., Boerrigter, P., Kligaad, H., and Speckmann, E.-J. (2003). Reduction of voltage-operated potassium currents by levetiracetam: A novel antiepileptic mechanism of action? Neuropharmacology45:661–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maehly, A. C., and Chance, B. (1954). The assay catalases and peroxidases. Methods Biochem. Anal.1:357–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marini, H., Costa, C., Passaniti, M., Esposito, M., Campo, G. M., Ientile, R., Adamo, E. B., Marini, R., Calabresi, P., Altavilla, D., Minutoli, L., Pisani, F., and Squadrito, F. (2004). Levetiracetam protects against kainic acid-induced toxicity. Life Sci.74:1253–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonough, S. H., and Shih, T. M. (1997). Neuropharmacological mechanisms of nerve agent induced seizure and neuropathology. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev.21:559–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashima, Y. L., Yoshii, M., and Suzuki, J. (2002). Ictogenesis and epileptogenesis in EL mice. Epilepsia43:130–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naffah-Mazzacoratti, M. G., Cavalheiro, E. A., Ferreira, E. C., Abdalla, D. S. P., Amado, D., and Bellissimo, M. I. (2001). Superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase activities and the hydroperoxide concentration are modified in the hippocampus of epileptic rats. Epilepsy Res.46:121–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento, V. S., D’alva, M. S., Oliveira, A. A., Freitas, R. M., Vasconcelos, S. M. M., Sousa, F. C. F., and Viana, M. M. F. (2005). Antioxidant effect of nimodipine in young rats after pilocarpine-induced seizures. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav.82:11–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, A. A., Nogueira, C. R. A., Nascimento, V. S., Aguiar, L. M. V., Freitas, R. M., Sousa, F. C. F., Viana, G. S. B., and Fonteles, M. M. F. (2005). Evaluation of levetiracetam effects on pilocarpine-induced seizures: Cholinergic muscarinic system involvement. Neurosci. Lett.385:184–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel, M., Liang, L. P., and Roberts, L. J. II. (2001). Enhanced hippocampal F2-isoprostane formation following kainate-induced seizures. J. Neurochem.79:1065–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel, M. (2004). Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress: Cause and consequence of epileptic seizures. Free Radic. Biol. Med.37(12):1951–1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulain, P., and Margineanu, D. G. (2002). Levetiracetam opposes the action of GABAA antagonists in hypothalamic neurons. Neuropharmacology42:346–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radenovic, L., and Selakovic, V. (2005). Differential effects of NMDA and AMPA/kainate receptor antagonists on nitric oxide production in rat brain following intrahippocampal injection. Brain Res. Bull.67:133–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajasekaran, K., Jayakumar, R., and Kaliyamurthy, V. (2003). Increased neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) activity triggers picrotoxin-induced seizures in rats and evidence for participation of nNOS mechanism in the action of antiepileptic drugs. Brain Res.979:85–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajasekaran, K. (2005). Seizure-induced oxidative stress in rat brain regions: Blockade by nNOS inhibition. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav.80:263–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigo, J. M., Hans, G., Nguyen, L., Rocher, V., Belachew, S., Malgrange, B., Leprince, P., Moonen, G., Selak, I., Matagne, A., and Klitgaard, H. (2002). The anti-epileptic drug levetiracetam reverses the inhibition by negative allosteric modulators of neuronal GABA- and glycine-gated currents. Br. J. Pharmacol.136:659–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sah, R., Galeffi, F., Ahrens, R., Jordan, G., and Schwartz-Bloom, R. D. (2002). Modulation of the GABAA gated chloride channel by reactive oxygen species. J. Neurochem. 80:383–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawas, A. H., and Gilbert, J. C. (1985). Lipid peroxidation as a possible mechanism for the neurotoxic and nephrotoxic effects of a combination of lithium carbonate and haloperidol. Arch. Int. Pharmacodyn.12:276–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedlak, J., and Lindsay, R. H. (1998). Estimation of total protein bound and nonprotein sulfhydril groups in tissues with Ellman reagents. Anal. Biochem.25:192–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharief, M. K., Singh, P., Sander, J. W. A. S., Patsalos, P. N., and Shorvon, S. D. (1996). Efficacy and tolerability study of ucb L059 in patients with refractory epilepsy. J. Epilepsy9:106–112. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, M. M., Kugelman, A., Iwamoto, T., Tian, L., and Forman, H. J. (1994). Quinone induced oxidative stress elevates glutathione and induces glutamylcysteine synthetase activity in rat lung epithelial L2 cells. J. Biol. Chem.269:26512–26517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sies, H. (1985). Oxidative stress: Introductory remarks. In Sies, H. (ed.), Oxidative Stress. Academic, New York, pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Simonié, A., Laginja, J., Varljen, J., Zupan, G., and Erakovié, V. (2000). Lithium plus pilocarpine induced status epilepticus-biochemical changes. Neurosci. Res.36:157–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tejada, S., Roca, C., Sureda, A., Rial, R. V., Gamundí, A., and Esteban, S. (2006). Antioxidant response analysis in the brain after pilocarpine treatments. Brain Res.69:587–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waltz, R., Moreira, J. C. F., Benfato, M. S., Quevedo, J., Schorer, N., Vianna, M. M. R., Klamt, F., and Dal-Pizzol, F. (2000). Lipid peroxidation in hippocampus early and late after status epilepticus induced by pilocarpine and kainic acid in Wistar rats. Neurosci. Lett.291:179–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, H., and Tang, H. (1996). Melatonin attenuates l-cysteine-induced seizures and lipid peroxidation in the brain of mice. J. Pineal Res.21:108–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zona, C., Niespodziany, I., Marchetti, C., Klitgaard, H., Bernardi, G., and Margineanu, D. G. (2001). Levetiracetam does not modulate neuronal voltage-gated Na+ and T-type Ca2+currents. Seizure10:279–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]