Abstract

A neutron resonance absorption imaging technique to visualize two-dimensional distributions with element discrimination has been developed at the Materials and Life Science Experimental Facility of the Japan Proton Accelerator Research Complex. We measured neutron transmission spectra from 1 eV to 100 keV while rotating a sample containing iron, zirconium, nickel, molybdenum, and aluminum rods. The distributions of hafnium (impurity of zirconium) and molybdenum were clearly obtained by a straightforward analysis using the most prominent resonances. Then an analysis using multiple resonances of each element simultaneously was performed finding that the accuracy of elemental identification was improved, and iron and nickel distributions became clearer. However, these analysis methods sometimes have difficulties in the case of overlapping materials since a resonance shape can be deteriorated by those of other materials. Such an example was demonstrated with the case of iron and nickel. To overcome the issue and aiming for further improvement, we proposed a method to fit the transmission spectrum in a wide range assuming the existence of possible elements, successfully visualizing both the distributions of the sample metals and those of hafnium and manganese (impurities of zirconium and iron). The newly introduced analysis technique will contribute to the establishment of a standard analytical procedure for general users of the facility.

Keywords: Neutron imaging, Resonance imaging

Subject terms: Mechanical engineering, Imaging techniques

Introduction

In recent years, accelerator-driven neutron facilities have begun implementing energy-resolved neutron imaging using pulsed neutron beam. Although this method is more complex than traditional radiography with white neutron beams, the energy spectrum provides fruitful information. For example, Bragg edge imaging1, which visualizes the spatial distribution of crystal information such as crystal structure and internal strain, has become a fundamental technique in cutting-edge research2. The neutron transmission spectra below several tens meV (longer than several angstroms) are analyzed in Bragg edge imaging, while the spectra above several eV provide information on elemental composition of a sample, especially at resonance energies. Resonance absorption imaging visualizes an element’s spatial distribution, only analyzing the transmission spectrum (dip) around its resonance energy3–10. Although high sensitivity is brought about at resonance energies, measurements take a long time to obtain statistical accuracy due to the narrow energy width of resonances. In addition, visualization becomes difficult with increasing resonance energy since higher time resolution in the time-of-flight measurement is required to resolve the resonance coupled with decreasing detection efficiency. Therefore, the maximum available energy for observable resonances is currently limited up to several keV. Under these limitations, we have worked to increase the variety of available elements and reduce measurement times to broaden the usability of resonance imaging technology. This paper proposes a new analysis method which fits the neutron transmission spectra in a wide range, including the non-resonance regions. We expect this to improve statistical accuracy and increase the number of available elements since the overall neutron energy dependence is also specified by element despite being less prominent than resonance reactions. We set the visualization of iron as the touchstone for the usefulness of the new technique. Although iron is a common element in industrial products and other imaging targets, it is unable to be identified in practice because its most prominent resonance peak is at a very high energy of 28 keV.

For the present study, we measured a test sample composed of iron and various metals at the RADEN11 beamline in the Materials and Life Science Experimental Facility (MLF)12 of the Japan Proton Accelerator Research Complex (J-PARC)13 by PIC-based gas neutron imaging detector, NID11,14,15, a typical detector used in RADEN.

Results

To evaluate the performance of resonance imaging with wide-range fitting up to 100 keV, elemental extraction demonstrations were performed on various metals. A zirconium rod with a diameter of 8 mm was placed at the center of an aluminum pipe (the outer diameter of 30 mm and the wall thickness of 1 mm). An additional five metal rods (10 mm in diameter) of iron, zirconium, nickel, molybdenum, and aluminum were arranged around the zirconium rod, positioned adjacent to each other as shown in Fig. 1 (left). The details of the metal rods are shown in Table 1. The neutron radiography results at and are shown in the center and right of Fig. 1, respectively. The measurement time of the resonance imaging at each angle was one hour.

Fig. 1.

A schematic view of the sample (at the rotation angle of ) and detector arrangement (left), and radiographs with the sample angles of (center) and (right). The colored rectangles represent regions where transmission will be calculated later (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Properties of the 5 cm long metal rods used for the measurements.

| Sample | Fe | Mo | Ni | Al | Zr-1 | Zr-2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter [mm] | 9.613 (5) | 10.017 (5) | 9.983 (5) | 9.993 (5) | 8.073 (5) | 10.100 (8) |

| Density [g/cm] | 7.85 (1) | 10.19 (1) | 8.86 (1) | 2.69 (0) | 6.55 (1) | 6.52 (1) |

| Nominal purity | 98% | 99.95% | 99% | 99% | 99.2% | 99.2% |

Elemental imaging with fitting of resonance dips

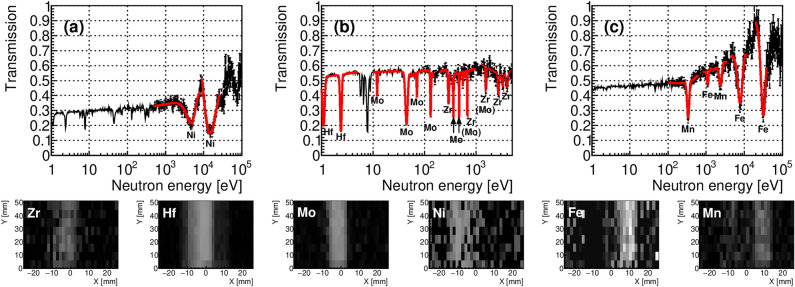

Figure 2 shows the transmission distribution measured by the NID. The XY-plane of Fig. 1 (center and right) is divided into three regions roughly the size of a rod (1050 mm), and the transmission distribution as a function of neutron energy obtained in each region is also shown in Fig. 2b and c, respectively. Calculated transmission spectra of five metals and possible impurities based on the total cross section in the Japanese evaluated nuclear data library JENDL-4.016 are also drawn in Fig. 2a for comparison. These curves were produced with the CRECTJ program17, which adjusts the energy bins of the curves to match the actual measured spectrum and the quantity of each element was assumed so that the magnitude of each resonance dip is suitable for comparison. Figure 2 shows many resonance dips between 1 eV and 100 keV in the measured and calculated curves. In the measured transmission spectra of the left part (green region in Fig. 1 center), sharp resonance dips of hafnium (an impurity of zirconium) at 1.1 eV, 2.4 eV and 7.8 eV and molybdenum at 44 eV and 0.13 keV are found. Also, broad dips from nickel at about 4.5 keV and 14 keV are recognized. In the central part (red region in Fig. 1 center), more prominent dips from hafnium and molybdenum and dips from zirconium at 0.29 keV are shown. In the right part (blue region of Fig. 1 center), broad dips from iron at 7.9 keV and 28 keV are confirmed. The three dips from manganese (a possible impurity of iron) at 0.34 keV, 1.1 keV and 2.4 keV are also identified. Although aluminum has three resonances at 5.9 keV, 35 keV and 88 keV, they are not recognized in the measured spectrum since the lower two and higher one are overlapped by broad resonances and fine resonances of iron, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Neutron transmission as a function of neutron energy; (a) calculated curves using JENDL16 nuclear data and CRECTJ17 program, (b) measured spectra obtained at sample angle of , and (c) same as (b) but sample angle is . For (b) and (c), the three measured spectra are obtained from the three colored regions in Fig. 1, respectively.

A closer examination of Fig. 2 reveals that many resonance dips, particularly in higher energy regions, overlap or merge, obscuring the signals of elements with small cross-sections. To extract individual elemental signals from these congested spectra, several approaches were tested. As shown in Fig. 2, the actual measured resonance dips are deformed from the calculated one. Possible reasons for this deformation include the effects of the detector resolution, the pulse function which means the uncertainty of the measured energy due to the event that neutrons of a certain energy arrive at the detector spread out in time rather than at exactly the same time, background shapes, and the ambiguity of resonance parameters in the nuclear data library. The ideal process is to unravel the effects of these factors one by one and incorporate them into a realistic resonance spectrum. However, this process requires tremendous effort, and the necessary technology is not yet fully developed. A more practical approach is to determine the empirical shapes directly from the measured spectrum. Therefore, the centroid and width of the resonance were derived beforehand from the spectrum in which each peak of interest was most enhanced using high-statistics data obtained by summing the spectra of pixels in the colored region in Fig. 1. Typical fitting curves are shown in Fig. 3a–c.

Fig. 3.

Gaussian fitting to determine the shape of the resonance (upper row) and a standard resonance imaging by using the parameters obtained from the fitting (bottom row).

Resonance imaging analysis of zirconium is particularly challenging owing to the narrow widths and small cross-sections of its prominent resonances at 0.29 keV and 3.8 keV. In such cases, natural impurities can be useful. Hafnium, which is present in most natural zirconium ores, often accompanies zirconium. Despite a small content, hafnium can behave as an excellent tracer for zirconium due to its many significant resonances in the eV-order energy region. Therefore, in this study, resonance imaging included identification of impurities, such as hafnium and manganese, in addition to the planned metals. Figure 3 bottom also shows the two-dimensional distributions for each element obtained from the standard resonance imaging using the transmission shape of the most prominent resonance of each element, as mentioned above. It can be seen that some elements are well reconstructed. In particular, hafnium and molybdenum, which have large and isolated resonance dips, show two-dimensional distributions with good signal-to-noise ratios. On the other hand, iron and nickel, which have resonances at high energies, and zirconium, which has only small resonance dips, did not produce clear two-dimensional images.

To improve element identification performance, it is beneficial to fit multiple dips simultaneously rather than fitting a single dip. Figure 4a–d shows the two-dimensional distributions of iron identified using single dip fitting at 1.2 keV, 7.9 keV and 28 keV, as well as multi-dip fitting. The image obtained by the 7.9 keV resonance is the clearest among the singe-dip fitting. Further improved discrimination performance is achieved by the multi-dip fitting. While this approach is effective, it would not be beneficial for elements with small resonances like zirconium. In such cases, an alternative approach, discussed below, is expected to have the potential to yield better results.

Fig. 4.

Extracted iron distribution by single dip fitting (a)–(c), multi-dip fitting (d), and wide-range fitting (e) which is described in text. The panels in bottom row show the x axis projection of the corresponding upper panel.

Elemental imaging with wide energy-range fitting

We demonstrated a new technique which fits neutron transmission spectra in a wide range, including the non-resonance regions, to improve the element distribution imaging. This method is expected to become a quantitative evaluation tool for two-dimensional distribution analysis and may also help visualize elements that are difficult using only resonances. This method is particularly beneficial for elements such as boron, which has a considerable cross-section but no characteristic resonance peak. In the spectrum fitting, the total cross-section in JENDL-4 is convolved with a pulse function reflecting the time distribution of the neutron pulse18 and is further smoothed according to the time resolution of the detector. This produces a template cross-section to approximate the measured transmission spectrum, which is then fitted with the elemental abundances as free parameters. To avoid the effects of neutron diffraction, being used in Bragg edge imaging, we performed the fitting above 1 eV. Figure 5a and b compares the nickel distribution obtained by the multi-dip (around 4.5 keV and 14 keV) fitting and this wide-range fitting, respectively. The signal-to-noise ratio is clearly improved. Such improvement was also observed in the iron distribution. The distribution obtained by wide range fitting is shown in Fig. 4e, and a comparison with Fig. 4d also confirms the obvious de-noising effect in the void region. However, it can also be seen that iron is reconstructed in the left part shown in Fig. 1 center where only nickel is present. We consider this artifact is caused by reproduction of the template cross section. Minor discrepancies between the measured and approximated transmission spectra may have led to the erroneous assignment of iron, which has resonances in an energy range nearby that of nickel. A detailed study of pulse structures with a simple sample would contribute to minimizing this issue.

Fig. 5.

Extracted nickel distribution by multi-dip fitting (a) and wide-range fitting (b). The panels in bottom row show the x axis projection of the corresponding upper panel.

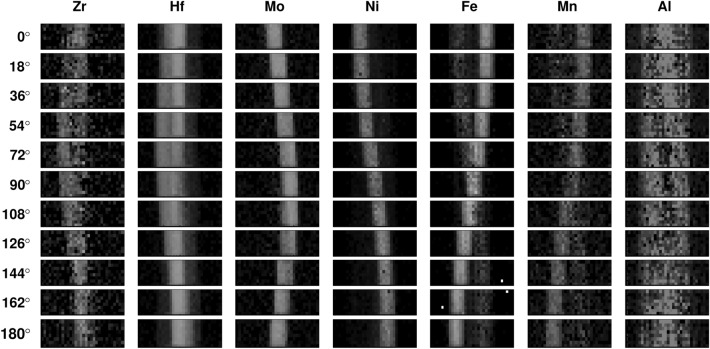

Figure 6 shows the two-dimensional distribution of each element obtained by the wide-range fitting. The position of each element, except aluminum, correctly moved with the rotation of the sample. The two-dimensional distribution of hafnium, acting as a good tracer of zirconium, is highly visible with a good signal-to-noise ratio. That of zirconium is also visualized although rather noisy due to the small neutron-cross section. As the sample is rotated, the initially overlapping zirconium rods become separated, which is particularly visible in the hafnium distribution. The distribution of manganese, identified as an impurity of iron, shows synchronous trajectory with iron. Unlike other elements, aluminum is visualized to be distributed thinly over a width of about 30 mm, the diameter of aluminum pipe of the sample. Although there appears to be a minor rod-like enhancement near the center of the view, it is unclear due to the poor signal-to-noise ratio. The enhancement disappeared at other angles indicating the effects of overlapping with other metal rods. The possibility of aluminum visualization, shown in this result, should be investigated with a simpler arrangement.

Fig. 6.

Two-dimensional spatial distributions for each extracted element. The field of view for each panel is 50 mm square (panels are vertically compressed). Rows represent different sample rotation angles, and columns represent different element types. The corresponding elements are indicated at the top of each column.

Discussion

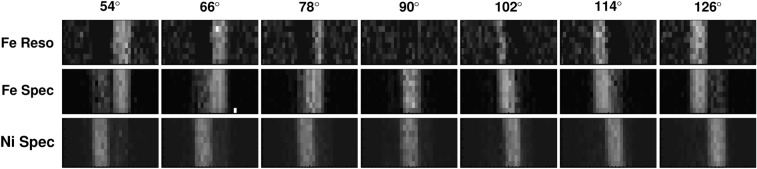

The wide-range fitting method effectively improves the neutron imaging of elemental distribution when the resonance-dip fitting is insufficient. Especially it exhibits an advantage for a realistic sample with overlapping elements having resonances close in energy. A notable example involves iron and nickel. Iron has significant resonances at 7.9 keV and 28 keV, and nickel has broad resonances at 4.5 keV and 15 keV; these resonances are combined under certain conditions due to the broadening by the neutron pulse structure. The blue curve in Fig. 2b, corresponding to the transmission spectra of iron and aluminum, shows sharp dips at resonance energies of iron. These dips are much shallower in the red curve of Fig. 2c, which shows the transmission spectrum of iron, zirconium and nickel. The nickel resonances obviously deteriorate the shape of the iron resonances, suggesting that the iron thickness is underestimated in elemental imaging with single or multi-dip fitting. Figure 7 describes this effect, showing iron distributions obtained by the multi-dip fitting (upper row). The distributions of iron and nickel by the wide-range fitting are also shown in the middle and bottom rows, respectively. In the multi-dip fitting case, the iron distribution almost disappears around where nickel overlaps but remains visible in the wide-range fitting case. This indicates that the wide-range fitting is essential to avoid the influence of other materials especially having significant resonances next to each other. Although the example with iron and nickel is a rather challenging case, similar issues may arise with practical samples containing many materials. While broad resonances have the advantage for neutron resonance imaging, they sometimes affect relatively small resonances attributed to other elements, making their quantification difficult. From this perspective, the wide-range fitting has the potential to solve this difficulty, as demonstrated in the nickel case. Moreover, this approach is expected to address the statistical limitations of resonance imaging. For example, the 28 keV resonance of iron, as seen in Fig. 2, has a width of only about 3 s in flight time, which is very short compared to the pulse interval of 40 ms. The wide-range fitting extends the time range by 2 or 3 orders of magnitude and improves statistical accuracy. It suggests that this analysis method is promising for element-specific quantitative imaging. However, a concern is that using a variety of elemental spectra may cause artifacts because it increases the degrees of freedom needed to reproduce the measured transmission spectrum.

Fig. 7.

Reconstructed iron distribution with the multi-dip fitting (upper row) and two-dimensional maps of iron (middle row) and nickel (bottom row) derived by wide-range fitting. Columns represent different sample rotation angles. The field of view for each panel is 50 mm square (panels are vertically compressed).

Conclusion and Outlook

The short-pulse neutron beam and a state-of-the-art time-resolved two-dimensional detector at MLF enabled us to successfully visualize distributions of various metals by analyzing transmission spectra up to 100 keV. The straightforward analysis using a single resonance was found to be advanced by including multiple resonances in the analysis (the multi-dip fitting). As an example, the obtained distributions of iron were discussed. Furthermore, it was found that fitting not only resonances but also the gradual energy dependencies in a wide range improves the signal-to-noise ratio, enhances statistics, and accurately extracts elemental distributions even if resonances are obscured in the transmission spectrum. Using the wide-range fitting method introduced in this paper, resonance imaging has overcome the limitations of conventional analysis and evolved into a practical measurement technique.

The extension of the available energy range will make it possible to identify other elements besides iron and nickel, such as fluorine, silicon, magnesium, and so on, for which resonance imaging has yet to be practical. Although the two-dimensional distribution obtained by standard resonance imaging containing some non-negligible noise due to the characteristic wide resonance width of the above elements, the signal-to-noise ratio was further improved by analyzing the spectrum with a wide energy range. This result suggests that we can overcome the statistical weakness of conventional resonance imaging, where only a part of the measured spectrum around the resonance is used. It motivates us to evaluate the neutron beam pulse structure, detector time resolution, instrument background, neutron energy calibration with high precision, and so on, in more detail for further improvement. A proper understanding of the background and time spread of mono-energetic neutrons are also critical factors in quantitative analysis. These programs are already underway at MLF, and another imaging technique possessing next-generation quantitative evaluation performance will be realized in the future. These efforts will also mitigate such artifacts as shown in the case of iron overlapping nickel. Furthermore, the practical application of quantitative analysis is also expected to enable isotope abundance ratio measurements using neutron resonance absorption reactions.

This newly introduced analysis needs a list of elements in the sample in advance for spectrum fitting. In this regard, analyzing single or multiple resonances play an important role, and combining it with other methods, such as prompt gamma-ray activation analysis, is expected to make even better measurements to reduce the number of free parameters (possible elements) as much as possible. We will continue efforts to establish a standard analytical procedure for general users of MLF to visualize two-dimensional distributions of various elements using neutrons in the resonance and higher energy region. Such efforts include not only the detailed evaluation of the neutron parameters but also combinations of other methods essential for the analysis.

Methods

The measurements were performed at the J-PARC/MLF BL22 RADEN beamline using a neutron beam produced by a 600-kW proton beam, with the L/D value of 2000 set using a rotary collimator equipped in RADEN. A collimator made of iron and boron-loaded polyethylene blocks was temporarily placed upstream of the sample and NID. The thickness of both the iron and polyethylene collimators was 20 cm. The aperture of the collimator was set 50 mm wide and 100 mm height so that the beam shape was roughly matched to the aluminum pipe which located at 10 cm from NID. The collimator served to prevent gamma-rays and neutrons from hitting the readout board of the detector and to collect data efficiently by irradiating neutrons only in the region of interest. The NID was placed about 24 m from the moderator and calibrated to energy from the measured time-of-flight (TOF) based on the equation: , where is the neutron energy, is the neutron mass, L is the flight length, and is the delay of start signal supplied by the facility. We obtained m and s by using the resonances of gold, silver, copper, tungsten, cadmium, and tantalum. A 50 mm thick lead filter was placed on the beam course to adjust the detector counting rate and to block gamma-rays from the moderator.

For resonance imaging, first, the ratio of the spectra obtained with and without sample was taken to obtain the transmittance distribution as a function of energy for each pixel. The two spectra were normalized by the number of pulsed neutrons. The pixel size was 1.6 mm6.4 mm, which represents the effective spatial resolution of this analysis. the single and multi-dip fit were performed by

| 1 |

where is the centroid, is the width, is the peak height of i-th resonance dip, and is the coefficient of the third-order polynomial. The and are fixed values determined beforehand for each element and resonance using highly statistical data. In the multi-dip fit, the energy range including resonances of other elements were excluded from the fit.

The wide-range fitting was performed using the abundances of all possible elements as free parameters in

| 2 |

where is the macroscopic total cross section and is the thickness of the i-th element. The energy bins of cross section data from JENDL-4 were aligned with the measured data by using the CRECTJ17 program. In the wide-range fitting, the uncertainty of the background distribution estimated beforehand by the black resonance method which estimates background using saturated resonances, was too large, particularly in the region above 1 keV. This method also estimate the background was less than 1% in the region below 100 eV by resonances of cadmium and indium. Therefore, in this analysis, the background term was neglected in the fitting. As a result, it is inferred that the distribution of aluminum with close transmission shapes is affected by the background. All fitting in this analysis were performed with a chi-square test, and the fitting range was from 1 eV to 100 keV.

Acknowledgements

The experiments at J-PARC/MLF were carried out under MLF Project Use Proposal No. 2020P0702 and CROSS Development Use Proposal No. 2020C0006. The authors are very grateful to Mr. Keiichi Inoue for sample preparation.

Author contributions

Y.T. and T.K. conceived the experiment(s), Y.T., T.K., J.D.P., and Y.M. conducted the experiment(s), Y.T. and J.D.P. analysed the results, Y.T., T.K. and T.S. discussed the results. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Y. T.

Declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sato, H., Miyoshi, M., Ramadhan, R. S., Kockelmann, W. & Kamiyama, T. A new thermography using inelastic scattering analysis of wavelength-resolved neutron transmission imaging. Sci. Rep.13, 688. 10.1038/s41598-023-27857-0 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Su, Y. et al. Neutron Bragg-edge transmission imaging for microstructure and residual strain in induction hardened gears. Sci. Rep.11, 4155. 10.1038/s41598-021-83555-9 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tremsin, A. S. et al. Non-destructive study of bulk crystallinity and elemental composition of natural gold single crystal samples by energy resolved neutron imaging. Sci. Rep.7, 40759. 10.1038/srep40759 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Losko, A. S. & Vogel, S. C. 3D isotope density measurements by energy-resolved neutron imaging. Sci. Rep.12, 6648. 10.1038/s41598-022-10085-3 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ito, D. et al. Pulsed Neutron Imaging for Non-destructive Testing using Simulated Nuclear Fuel Samples. Phys. Procedia88, 89–94. 10.1016/j.phpro.2017.06.011 (2017). Neutron Imaging for Applications in Industry and Science Proceedings of the 8th International Topical Meeting on Neutron Radiography (ITMNR-8) Beijing, China, September 4-8 (2016).

-

6.Miyazaki, Y. et al. Observation of Eu adsorption band in the CMPO/SiO

-P column by neutron resonance absorption imaging. JPS Conf. Proc.33, 1–011073. 10.7566/JPSCP.33.011073 (2021). [Google Scholar]

-P column by neutron resonance absorption imaging. JPS Conf. Proc.33, 1–011073. 10.7566/JPSCP.33.011073 (2021). [Google Scholar] - 7.Ooi, M. et al. Neutron Resonance Imaging of a Au-In-Cd Alloy for the JSNS. The 7th International Topical Meeting on Neutron Radiography (ITMNR-7). Phys. Procedia43, 337–342, 10.1016/j.phpro.2013.03.040 (2013).

- 8.Oba, Y. et al. Neutron resonance absorption imaging of simulated high-level radioactive waste in borosilicate glass. Sci. Rep.13, 10071. 10.1038/s41598-023-37157-2 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tremsin, A. S. et al. Neutron resonance transmission spectroscopy with high spatial and energy resolution at the J-PARC pulsed neutron source. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A746, 47–58. 10.1016/j.nima.2014.01.058 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marcucci, G. et al. Mapping the elemental distribution in archaeological findings through advanced Neutron Resonance Transmission Imaging. Eur. Phys. J. Plus139, 475. 10.1140/epjp/s13360-024-05222-y (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shinohara, T. et al. The energy-resolved neutron imaging system. RADEN. Rev. Sci. Instrum.91, 043302. 10.1063/1.5136034 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakajima, K. et al. Materials and life science experimental facility (MLF) at the Japan proton accelerator research complex II: neutron scattering instruments. Quant. Beam Sci.1, 10.3390/qubs1030009 (2017).

- 13.Nagamiya, S. JAERI-KEK Joint Project on High Intensity Proton Accelerators. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol.37, 40–48. 10.1080/00223131.2000.10874843 (2000). [Google Scholar]

-

14.Parker, J. D. et al. Spatial resolution of a

PIC-based neutron imaging detector. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A726, 155–161. 10.1016/j.nima.2013.06.001 (2013). [Google Scholar]

PIC-based neutron imaging detector. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A726, 155–161. 10.1016/j.nima.2013.06.001 (2013). [Google Scholar] - 15.Parker, J. D. et al. Development of energy-resolved neutron imaging detectors at RADEN. Proceedings of the International Conference on Neutron Optics (NOP2017)10.7566/JPSCP.22.011022 (2018).

- 16.Shibata, K. et al. JENDL-4.0: A new library for nuclear science and sngineering. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol.48, 1, 10.1080/18811248.2011.9711675 (2010).

- 17.Nakagawa, T. CRECTJ: A computer program for compilation of evaluated nuclear data,. Tech. Rep., JAERI-Data/Code 99-041 (1999). 10.11484/jaeri-data-code-99-041.

- 18.Hasemi, H. et al. Evaluation of nuclide density by neutron resonance transmission at the NOBORU instrument in J-PARC/MLF. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A773, 137–149. 10.1016/j.nima.2014.11.036 (2015). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Y. T.