Abstract

Background

Sport climbing, officially added to the 2020 Summer Olympics, has grown rapidly, with U.S. climbing gyms increasing from 310 in 2013 to 591 in 2021. Over the past decade, European research has identified bouldering as a potential psychotherapeutic treatment for anxiety and depression. Randomized controlled trials have compared bouldering psychotherapy (BPT) to cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), showing that BPT produces comparable results and positively impacts mental health.

Purpose

There have been very few studies dedicated to the use of rock climbing as a therapy in the United States; further, there are few surveys that investigate whether American climbers would even consider climbing as beneficial towards mental health or not. With the ever-growing prevalence of mental health disorders and as climbing gains more traction, it is important to explore the potential of climbing as a therapeutic modality. It is hypothesized that rock climbing will be viewed as beneficial towards mental health amongst the population surveyed.

Methods

A prospective survey was conducted to assess rock climbing’s impact on mental health, focusing on participants' climbing habits and perceptions of its therapeutic benefits. The protocol was approved by the Rowan-Virtua IRB (Reference #: PRO-2022–353) in accordance with the latest guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Participants were recruited using flyers and posters at climbing gyms, an online climbing forum, and social media. The survey included individuals aged 18 years and older who engage in rock climbing at least once per week. No specific exclusion criteria was set in place, though participants were given the option to omit the mental health portion. The survey included questions on climbing frequency, mental health impact, and demographics. The survey was distributed online via Qualtrics Forms between February 2023 to June 2023, with informed consent obtained from participants, explaining both risks and data safeguards in place. Univariate graphs and bivariate analyses via chi square analysis were done using R Studio.

Results

A total of 748 survey responses were received, with 50.4% of participants aged 26–40 years. Most were White Non-Hispanic (59.7%) and resided in the Mid-Atlantic/Tri-State Area. Climbing preferences showed indoor bouldering (24.9%) as the most popular, followed by indoor top rope (16.4%) and indoor lead climbing (12.4%). Outdoor climbing activities were less common, with traditional climbing at 10.1% and speed climbing at 0.2%. Significant associations were found between climbing frequency and age (p = 0.0045), session length and age (p = 8.2e-10), and climbing frequency by gender (p = 0.0024). Regarding social behavior, 46.8% identified as introverts and 37.1% as ambiverts. Mental health data revealed that 73.1% of climbers felt rock climbing positively impacted their mental health. Depression and anxiety were the most reported conditions. When compared to therapy and medications, 73.3% of participants found rock climbing more beneficial than medications, and 64.8% found it more beneficial than therapy. Gender and race were significantly associated with perceptions of climbing's mental health benefits (p = 0.0448 and p = 0.0422, respectively).

Conclusion

Survey results offered future focal points of interest and affirmed that BPT would be received well as a therapeutic modality in the United States. Further, survey participation of 748 completed responses illustrates the community’s support and open communication regarding mental health, creating a promising field to continue exploring. Overall, rock climbing holds potential as a treatment modality for mental health disorders, further bridging the gap between physical and mental health.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s44192-025-00154-0.

Keywords: Rock climbing, Mental health, Prospective survey

Introduction

What was once thought to be a niche hobby has grown exponentially popular in recent years. In 2016, sport climbing was incorporated in the 2020 Summer Olympics. In just seven years, the number of climbing facilities in the United States nearly doubled from 310 climbing gyms at the end of 2013 to 591 gyms by the end of 2021. In 2021, it was estimated that over 10.3 million people in the United States participated in some form of indoor, sport/boulder, and traditional/ice/mountaineering climbing [1].

Rock climbing can be considered a unique and multifaceted sport due to its combination of physical, mental, and social challenges. Physically, it demands strength, endurance, and flexibility. Mentally, it requires problem-solving skills and strategic thinking, as climbers must plan their routes and adapt to changing conditions. Socially, it fosters a sense of community and mutual support, as climbers often rely on each other for safety and encouragement [2].

The four general categories of climbing include traditional, sport, speed, and bouldering. Indoor climbing, often consisting of bouldering or top-rope climbing, provides a controlled and social environment that fosters focus and collaboration, potentially reducing stress and improving mood through accessible, structured challenges. In contrast, outdoor climbing, such as sport climbing or traditional climbing, combines physical exertion with exposure to nature, which can amplify mental health benefits by reducing anxiety and boosting feelings of connection to the environment. Shorter, intense climbs might provide quick mental boosts, while longer, more strenuous climbs can foster endurance, patience, and a deep sense of accomplishment. Each type offers distinct therapeutic effects, appealing to individuals based on their specific mental health needs and preferences [3, 4].

Rock climbing, in its diverse forms, provides a compelling lens through which we can explore the intricate relationship between physical and mental health. Traditional climbing, with its unpredictability and the possibility of taking a daunting "whipper" fall, in which the climber may fall, on rope, from a significant height above the last piece of safety gear they placed, underscores the demand for not only physical strength but also mental resilience. It is a sport where climbers must manage risks, make quick decisions, and confront their fears, echoing the challenges of life itself and the need for emotional fortitude [3].

To further address rock climbing’s effect on intrapersonal psychological health, it also plays a major role in improving interpersonal psychological health through emphasizing peer relationships. Climbing, whether it be lead rope, top rope, or bouldering, underscores the importance of trust and collaboration. Top rope climbers must trust in their belayers, who are responsible for managing the climbing rope and ensuring their safety. In contrast, bouldering is a form of climbing in which the harness and rope are left behind. Instead, the climber attempts climbs, also known colloquially as ‘problems’ or ‘routes,’ that are typically shorter than those on ropes over safety mats, going up to 20 feet high. It showcases how physical activity can promote mindfulness and self-awareness, thus nurturing mental health. Bouldering places more emphasis on strength, creativity, and technique to navigate tricky problems as compared to rope climbing, which focuses on endurance, strategy, and trust in a partner. While they both have different approaches, both bouldering and rope climbing foster skills in which solving a problem encourages teamwork to come to a resolution that brings a sense of accomplishment [5, 6].

The purpose of this survey is to understand a general opinion of how climbing impacts mental health to assess the viability of introducing climbing as a therapeutic modality, such as bouldering psychotherapy (BPT), in America [7]. Based on existing literature, it was hypothesized that rock climbing would be regarded as beneficial towards mental health by the population surveyed. Further, it was hypothesized that gender and race would affect the perception of the benefits of climbing and of therapy as compared to climbing for mental health.

By investigating the outlook of climbers, the introduction of climbing therapy in the United States becomes much more tangible. Since studies have mainly been done in Europe, the importance of surveying Americans about whether they believe in the efficacy of rock climbing as a therapy would guide the implementation of climbing therapy in America. With the evolving nature of psychiatric care and bursting interest in rock climbing, climbing therapy has the potential to help coalesce physical and mental well-being as an emerging form of therapy.

Methods

Survey

For this study, an online Qualtrics survey was open for four months between February 2023 to June 2023 to a general population of rock climbers. The participants were recruited using flyers and posters that were distributed at climbing gyms, Gravity Vault in Voorhees, NJ and Method Climbing and Fitness in Newark, NJ. Additionally, social media groups and websites dedicated to rock climbing were approached as well. These sites included Facebook, moutainproject.com, which is an online climbing forum, and Instagram. No incentive was provided for participating in the survey. The participants were reassured that their participation was voluntary and that if they chose to participate, their responses would be anonymous and protected. Further, they were not at any risk of physical harm by participating in this survey. As psychiatric diagnoses, amongst other data obtained, may be sensitive information, strict data handling protocols, including encryption and restricted access, were in place. The survey has three parts: the first being demographic information, the second involving physical health, and the last related to mental health. The protocol was approved by the Rowan-Virtua IRB (Reference #: PRO-2022-353) in accordance with the latest guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

The survey consisted of a total of 20 questions and took less than five minutes to complete. The demographic portion of the survey asked age, identified gender, race, climbing gym location, duration of climbing experience, type of climbing, and level of climbing. The physical health portion focused on types of injuries received through climbing, treatment modalities employed for said injuries, frequency of climbing per week, climbing session duration, and warm-up times before climbing. Finally, the mental health aspect asked questions regarding psychological diagnoses and overall opinions of how rock climbing affects mental health. For full survey content, see supplementary materials [Supplementary File 1].

Participants

The target population was rock climbers. All climbers aged 18 and above, of all genders and ethnic backgrounds were included. Though specific exclusion parameters were not set in place, participants were given the option to respond “not applicable” to questions regarding mental health. Background information, such as the location of their main gym and grade level that they climb, was asked to better understand the demographic. The overall goal of this study was to gather a comprehensive response from a public climbing community.

Interventions

The nature of this study as a survey did not require any physical intervention, medical procedures, or exposure to any experimental methods. Participants were solely asked to respond to a series of questions, either online or via paper, regarding their personal experiences, behaviors, or perceptions related to the topic of interest. The study was observational, meaning it did not require any manipulation of variables or participant exposure to treatments, drugs, or devices.

Because the study relied on self-reported data through a questionnaire, there was no direct interaction with participants beyond the completion of the survey. No diagnostic tests, therapeutic interventions, or physical assessments were conducted during the course of the study. Furthermore, as no experimental conditions were applied, the risk of adverse effects or complications was minimal.

Outcome measures

Dependent variables in this survey included responses to survey questions, such as the perception of the effect of climbing towards mental health as compared to medication or therapy. Frequency and length of climbing also represented dependent variables. Independent variables included age, race, and gender.

Data extraction

The survey responses from the participants were assigned numerical values and data was extracted in that fashion. For example, one of the questions asked was: “Compared to medication, rock climbing is more beneficial in regards to my mental health.” The answer options for this question were modeled after a Likert scale as follows: “strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, strongly agree.” In this case, these choices were assigned a number ranging from 1 to 5, with 5 being “strongly agree.” Two other options were included as well to cover participants who may not be taking medications or have no psychiatric diagnosis. These options equated to 0. With numerical values given to these qualitative answers, the data was extracted more efficiently.

Data analysis

Summary results are presented as absolute frequencies and percentages for all variables studied. Groups were compared using the chi-squared test and differences were deemed significant at alpha = 0.05. All analyses were performed using software R version 4.4 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Demographic

As shown in Table 1, a total of 748 climbers participated in the survey. The majority of participants were between the ages of 26 and 40 years old (50.4%), followed by those aged 18 to 25 years (33%). A smaller percentage were aged 41 to 65 years (14.3%) and 2.3% were over 65 years old. Gender distribution was nearly equal, with 48% identifying as male and 48.6% identifying as female. A smaller portion identified as non-binary (2.4%), and 1% preferred not to disclose their gender.

Table 1.

Participant demographics. The subset listed as “Other,” represents a free text option for participants

| Demographic Category | Number of Climbers | Percent of Climbers |

|---|---|---|

| Gender Identity | ||

| Male | 338 | 48 |

| Female | 342 | 48.6 |

| Non-Binary | 17 | 2.4 |

| Prefer not to say | 7 | 1 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Asian/Asian American | 166 | 23.6 |

| Black/African American | 7 | 1 |

| LatinX | 53 | 7.5 |

| Native American | 3 | 0.4 |

| Pacific Islander | 4 | 0.6 |

| White/Caucasian | 447 | 63.5 |

| Other | 24 | 3.4 |

| Age | ||

| 18–25 | 232 | 33 |

| 26–40 | 355 | 50.4 |

| 41–65 | 101 | 14.3 |

| > 65 | 16 | 2.3 |

| Area | ||

| New England, USA | 54 | 7.7 |

| Tri-state Area, USA | 161 | 22.9 |

| Southeast, USA | 44 | 6.2 |

| Midwest, USA | 52 | 7.4 |

| Great Plains, USA | 5 | 0.7 |

| Rocky Mountains, USA | 87 | 12.4 |

| Southwest, USA | 39 | 5.5 |

| West Coast, USA | 135 | 19.2 |

| Alaska and Hawaii, USA | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 127 | 18 |

In terms of race and ethnicity, the majority of participants were White/Caucasian (63.5%), followed by Asian/Asian American (23.6%), LatinX (7.5%), and other groups including Black/African American (1%), Native American (0.4%), and Pacific Islander (0.6%). The “Other” category, which included responses from free-text entries, accounted for 3.4% of participants.

Geographically, climbers were predominantly located in the Tri-State Area (22.9%) and the West Coast (19.2%), with smaller percentages from the Rocky Mountains (12.4%), New England (7.7%), Southeast (6.2%), and Midwest (7.4%) regions. A significant portion (18%) of participants reported residing in locations outside the United States. This diverse sample of climbers provides a broad representation of both demographic and geographic characteristics within the climbing community.

Climbing background

Table 2 presents climbing demographics. Indoor bouldering surpassed other types of climbing in popularity at 24.9% (533 responses). Of note, participants were given the option to select multiple options for the question regarding climbing setting. The category following closely behind presented indoor top rope at 16.4% (351 responses). Indoor lead climbing received 266 responses, at 12.4%. Outdoor bouldering, top roping, and lead climbing followed their indoor counterparts at 10.3%, 9.1%, and 15% respectively. Traditional climbing represented 10.1% (216 responses and speed climbing at 0.2% (5 responses). “Other” was left as a free text option, which mainly resulted in ice climbing at 1.7% (37 responses).

Table 2.

Climbing background information

| Question | Number of Responses | Percent of Responses |

|---|---|---|

| Q1. What type of climbing do you do the most? | ||

| Bouldering (Indoors) | 533 | 24.9 |

| Bouldering (Outdoors) | 220 | 10.3 |

| Top Rope (Indoors) | 351 | 16.4 |

| Top Rope (Outdoors) | 194 | 9.1 |

| Lead Climbing (Indoors) | 266 | 12.4 |

| Lead Climbing (Outdoors) | 321 | 15 |

| Traditional Climbing | 216 | 10.1 |

| Speed Climbing | 5 | 0.2 |

| Other | 37 | 1.7 |

| Q2. How long is your average climbing session? | ||

| < 1 h | 166 | 23.6 |

| 1–2 h | 7 | 1 |

| 2–3 h | 53 | 7.5 |

| 3–4 h | 3 | 0.4 |

| > 4 h | 4 | 0.6 |

| Q3. How often do you climb? | ||

| < 1 day per week | 31 | 4.5 |

| 1 day per week | 63 | 9.1 |

| 2 days per week | 171 | 24.8 |

| 3 days per week | 294 | 42.6 |

| 4 days per week | 98 | 14.2 |

| > 4 days per week | 33 | 4.8 |

The subset listed as “Other,” represents a free text option for participants

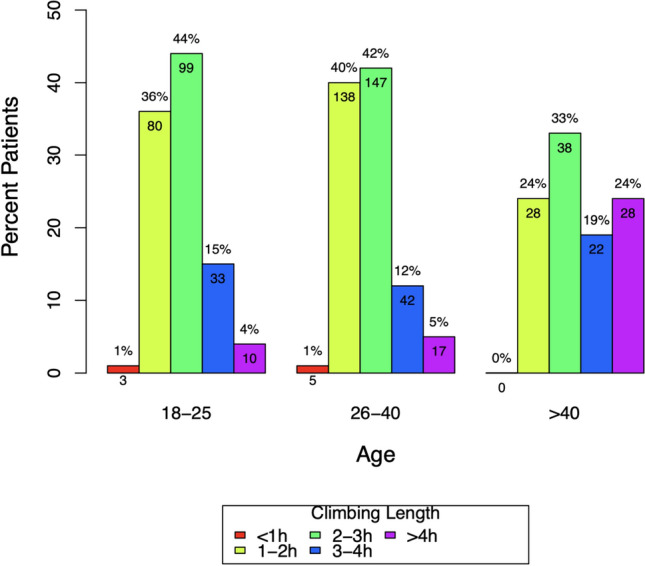

Figure 1 illustrated a bivariate analysis graph representing participant responses to climbing frequency as compared to reported age (p = 0.0045), which demonstrated participants in the age categories of 18–25 and 26–40 tended to climb more frequently in the week than those aged > 40. About 53% of the older climbers climb less than 3 days per week as opposed to 32% and 38% of those between the ages 18–25 and 26–40, respectively. Figure 2 demonstrated a bivariate analysis graph of climbing session length as compared to age (p = 8.2e-10), illustrating a clear relationship between age and climbing frequency, with older climbers (> 40) tending to climb for longer times than the younger ones (p = 8.2e-10). About 43% of the older climbers climb for at least 3 h as opposed to 19% and 17% of those between the ages 18–25 and 26–40, respectively. Figure 3 examines the link between gender and climbing frequency (p = 0.0024), demonstrating an increased frequency with male climbers relative to female climbers. As the data shows, 45% of females climb less than 3 days per week compared to 30% of males.

Fig. 1.

Bivariate analysis graph of climbing frequency by age, with “days per week” abbreviated to “DpW” in the legend (p-value = 0.0045)

Fig. 2.

Bivariate analysis graph of climbing session length by age, with “hours” abbreviated to “h” in the legend (p-value = 8.2e-10)

Fig. 3.

Bivariate analysis graph of climbing frequency by gender, with “days per week” abbreviated to “DpW” in the legend (p-value = 0.0024)

Social nature

As shown in Fig. 4, 46.8% self-reported as introvert, 37.1% as ambiverts, and 16% as extroverts. 74.1%, which incorporated stronger than “neutral” responses, reported engaging in social behavior. Figure 5 represented a bivariate analysis graph of interaction by gender (p = 0.0023). In Fig. 5, there is a clear relationship between social behavior and gender, with females tending to be more social than males. In fact, 81% of the female population “agreeing” and “strongly agreeing” with a statement saying they interacted with their climbing peers compared to the male population with only 69% “agreeing” and “strongly agreeing” to the same statement.

Fig. 4.

Bar graphs illustrating climbers’ responses for self-perceived personality category (introvert, extrovert, ambivert) on the top and responses towards the statement “During my climbing sessions, I always interact with (ex. Talk to, climb with) other people,” on the bottom. For the latter, the X axis was abbreviated from left to right as follows: “Strongly disagree,” “Disagree,” “Neutral,” “Agree,” and, “strongly agree”

Fig. 5.

Bivariate analysis graph of interaction by gender, with abbreviations as follows: “Strongly disagree,” “Disagree,” “Neutral,” “Agree,” “strongly agree” (p-value = 0.0023)

Mental health

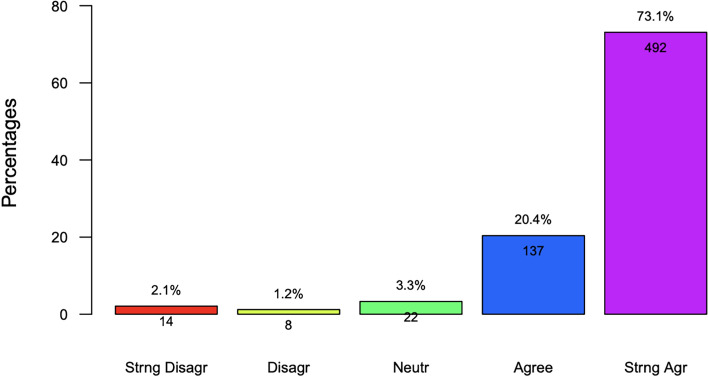

Figure 6 illustrated the breakdown of mental health disorders surveyed. Of note, participants were given the option to select multiple options or “not applicable,” if applicable. 73.1% of respondents agreed that rock climbing had a positive effect on mental health amongst climbers, as represented in Fig. 7.

Fig. 6.

Breakdown of mental health disorders including anxiety, depression, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), bipolar disorder (BP), none, and ‘other’ as a free text option

Fig. 7.

Bar graph illustrating climbers’ responses towards the statement, “I believe that rock climbing improves my mental health.” The X axis was abbreviated from left to right as follows: “Strongly disagree,” “Disagree,” “Neutral,” “Agree,” “strongly agree”

When discussing mental health, rock climbers primarily reported having a history of depression and/or anxiety. Individual questions also inquired about the benefits of rock climbing versus therapy or versus medications shown in Figs. 8 and 9. Reports showed that therapy and medications had “Neutral” beneficence, 40.8% and 31.9%, respectively. Compared to medications, 73.3% of individuals reported a stronger than “Neutral” beneficial response from rock climbing. Similarly, 64.8% of individuals reported a stronger response to rock climbing over therapy.

Fig. 8.

Bar graphs illustrating climbers’ responses towards the statements “Therapy is very effective for me,” on the left and “Rock climbing is more beneficial for me compared to therapy,” on the right. The X axis was abbreviated for both from left to right as follows: “Strongly disagree,” “Somewhat disagree,” “neither,” “somewhat agree,” and, “strongly agree”

Fig. 9.

Bar graph illustrating climbers’ responses towards the statement “Psychiatry medications are very effective for me,” on the top, with the X-axis labels abbreviated from left to right as follows: “Not at all,” “Slightly,” “Moderately,” “Very,” and “Extremely.” The graph on the bottom illustrates responses towards the statement “Rock climbing is more beneficial for me compared to medications,” on the right, with the X-axis abbreviated from left to right as follows: “Strongly disagree,” “Somewhat disagree,” “neither,” “somewhat agree,” and, “strongly agree”

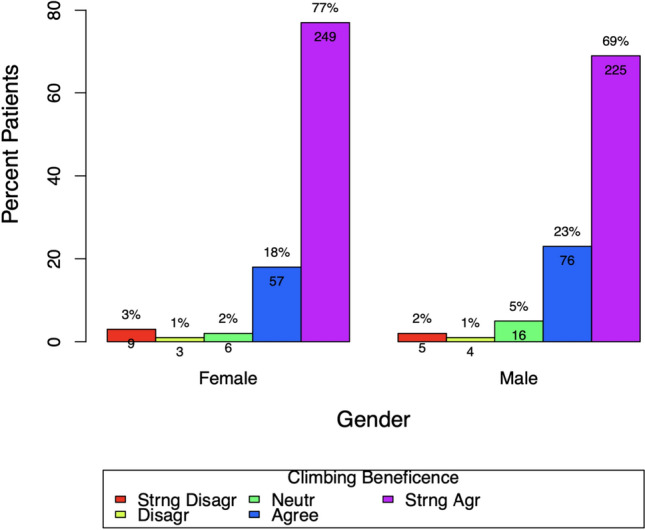

Figure 10 demonstrated an association between gender and perceived benefit of climbing towards mental health with 77% of females reporting that they strongly agreed with the statement as compared to 69% of males reporting the same (p = 0.0448). Figure 11 demonstrated a clear relationship between race and the perception of therapy as compared to climbing towards mental health with those identifying as ‘White’ and ‘Hispanic’ tended to strongly agree that climbing was more beneficial towards their mental health than therapy at 38% and 37% respectively, while the majority of those who identified as ‘Asian’ at 38% reported a neutral answer (p = 0.0422).

Fig. 10.

Bivariate analysis graph of climbing beneficence by gender, with abbreviations as follows: “Strongly disagree,” “Disagree,” “Neutral,” “Agree,” “strongly agree” (p-value = 0.0448)

Fig. 11.

Bivariate analysis graph of perception of therapy vs. climbing by race, with abbreviations as follows: “Strongly disagree,” “Somewhat disagree,” “Neither,” “Somewhat agree,” “Strongly agree” (p-value = 0.0422)

Discussion

Physical activity and exercise are important factors in maintaining a healthy lifestyle. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) recommend physical activity in the treatment and prevention of physical and mental diseases [8]. This acts as a basis for many studies investigating the link between physical activity and mental health, including this survey.

As hypothesized, 73.1% of survey participants agreed that rock climbing has a positive effect on mental health, with 73.3% of individuals reporting a stronger than “Neutral” response from rock climbing and 64.8% of individuals reporting a stronger than “Neutral” response from rock climbing over therapy. Figure 5 illustrated a potential association between gender and social interaction (p = 0.0023), while Fig. 10 demonstrated an association between gender and perceived benefit of climbing towards mental health (p = 0.0448). Figure 11 demonstrated a link between race and the perception of therapy as compared to climbing towards mental health (p = 0.0422). Thus, providing initial support for the study hypotheses.

Though the association between variables was not clear due to lack of controls and other limitations, the results provide insight in the potential to further individualize climbing therapy to participants in the future. For example, Fig. 1 demonstrated that participants aged 18–25 are associated with climbing 3 days per week (p = 0.0045), while Fig. 2 demonstrated that those aged > 40 were associated with longer climbing sessions (p = 8.2e-10). These results may inform future trials in structuring climbing therapy sessions accordingly for the age groups as mentioned.

Demographic data also offered valuable knowledge in the distribution of climbing type, average climbing session length, and session frequency. With 24.9% of participants reporting indoor bouldering as a type of climbing they engage in the most, climbing therapy, specifically BPT, may be a promising prospect in the United States. Though the majority of climbing therapy has been centralized around bouldering, this survey showed that future studies should center around accommodating other types of climbing into therapy treatments and how certain climbing therapies may be better adapted for specific mental health disorders. Multiple research studies were done in Europe regarding the efficacy of therapeutic climbing, or bouldering psychotherapy (BPT). These groups performed randomized controlled trials to compare the effects of BPT, CBT, and exercise on depression alone, concluding that BPT was more effective than physical exercise alone for the treatment of depression [7, 9–14].

This may be due to the camaraderie, mutual support, and shared goals in the climbing community contributing to an individual's overall well-being and improved mental health. Some may argue that any sport could foster a social environment, but Dorscht et al. (2019) has shown that bouldering has both the community and structure to complement and enhance group therapy [7].

A study examining the performance of introverts and extroverts in high anxiety or arousal states has contributed to understanding how personality traits, such as introversion and extraversion, may be related to self-efficacy. This study concluded that introverts may be more sensitive to high arousal states, negatively impacting their performance [15].

As per survey results, 46.8% self-reported as introverts, though 74.1% of participants reported engaging in social behavior during climbing sessions. This data suggested that the nature of rock climbing gyms may foster environments that enhance the social nature of introverts. Overall, the social nature of climbing, along with its association with self-efficacy, is understudied and should be an area of focus as well.

Understanding the concept of self-efficacy helps us understand how climbing, specifically bouldering, can act as a positive influence. As shown by Kratzer et al. (2021), bouldering addresses an individual’s perceived self-efficacy quickly because of the initial learning curve of the sport itself. In a multicenter, randomized controlled trial, they saw that progress can be made at exponential levels in the beginning and climbers can typically progress through multiple grade levels in a short period of time. Different types of success can be achieved in the sport as well, whether it be related to technique, gaining strength, grade level, etc. Further, climbing in a group setting allows for the direct observation of others and how they cope with their climbing projects [14, 16].

The high response rate and engagement with this survey within the climbing community is an important take-away of this study, as it illustrates the excitement around participation in mental health research among climbers. This study suggests that the climbing community may be a good potential population for continued research at the intersection of mental health and physical activity.

Future directions

Future trials for conducting bouldering psychotherapy can be initiated in the United States as our survey has demonstrated adequate interest and positive feedback. The sessions should be focused on the problem-solving and social nature that the sport offers. Emphasizing the importance of self-efficacy and self-esteem should also be a priority in these trials to ensure beneficence for the participants. Further development and studies of climbing therapy with rope and outdoor climbing is also an enticing topic to explore as even fewer studies about it exist. Another topic of study could identify certain climbing therapies that can be better adapted for specific mental health disorders. The social nature of climbing, along with its association with self-efficacy, is understudied as well. Rock climbing in general holds immense potential as a gateway sport to bridging the gap between physical and mental health.

Limitations

This study, despite its valuable insights, has several limitations that warrant consideration. Firstly, the survey respondents were primarily individuals actively engaged in rock climbing, potentially introducing a sample bias. This means that the findings may not be representative of those who do not participate in rock climbing, and their perspectives on its mental health benefits may differ. Secondly, the data collected in this research relied on self-reported information. Self-reporting is susceptible to social desirability bias, where respondents may provide answers they believe are more socially acceptable, potentially influencing the accuracy of their responses. Thirdly, the generalizability of the findings may be restricted due to the specific demographics of the study's sample. Thus, generalizing the results to a broader population or to other geographic areas may not be ideal. Additionally, the study adopted a cross-sectional survey design, which captured a snapshot of participants' perspectives at a single point in time. A longitudinal study could provide a more comprehensive understanding of how the mental health benefits of rock climbing evolve over time. Furthermore, this research did not include a control group for comparison, such as individuals who do not engage in rock climbing. A control group would have enabled a more robust assessment of the unique therapeutic effects of rock climbing. Lastly, it is important to acknowledge the subjective nature of mental health. Individual experiences and needs in the realm of mental health are highly variable. The study focused on specific mental health diagnoses, and other conditions or individual factors may play a role in the relationship between rock climbing and mental health. Therefore, the results should be interpreted with a degree of caution, recognizing the complexity of mental health as a personal and multifaceted matter.

Recommendations for healthcare professionals

Based on the findings and limitations of this study, healthcare professionals can consider the following recommendations:

Incorporate Rock Climbing into Therapeutic Options: Healthcare professionals should be open to exploring alternative therapeutic options, such as bouldering psychotherapy, for individuals with mental health challenges.

Assessment of Individual Needs: Recognize that mental health treatment is not one-size-fits-all. Healthcare professionals should assess an individual's specific needs and preferences when considering therapeutic interventions, including whether they have an interest in physical activities like rock climbing.

Promote Physical Activity: Encourage physical activity as part of a holistic approach to mental health. While not all individuals may choose rock climbing, engaging in regular physical activity has been linked to improved mental well-being.

Consider Social Aspects: The study highlights the social aspects of rock climbing. Healthcare professionals should consider the importance of social connections and community support in the treatment of mental health disorders. Encouraging participation in group activities or finding ways to connect patients with like-minded individuals can be beneficial.

Collaboration with Climbing Facilities: Collaborate with local climbing facilities to create programs or resources that integrate mental health support with climbing activities. This partnership could help individuals access the benefits of rock climbing more easily and safely.

Education and Awareness: Healthcare professionals should educate themselves about the potential therapeutic benefits of activities like rock climbing and raise awareness among their colleagues and patients. This can contribute to a more comprehensive approach to mental health treatment.

Conclusion

As rock climbing has witnessed exponential growth and recognition, this survey supports that climbing therapy would be a viable option to treat mental health amongst climbers in the United States. This research fills a significant gap in the body of knowledge by focusing on American climbers and their perspective on the sport's potential to influence mental health. Results also included data about climbing background, social nature, and mental health. The social aspect of climbing is a topic of interest as a majority of participants reported as “introvert,” but also reported that they engage in social interaction whilst climbing. This may be due to the relation between personality traits and self-efficacy, but this has not been studied thoroughly. With a high response rate despite lack of incentive, this study suggests that the climbing community may be a good potential population for continued research at the intersection of mental health and physical activity. As mental health continues to be a pressing concern, this study paves the way for further research and exploration in this field.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

K.C. initiated the project, conducted the survey, prepared figures, and drafted and revised the main manuscript text. S.S. contributed to the draft and revision of the text. D.L. and A.G. revised manuscript text. C.P. was responsible for the interpretation and visualization of data. A.R. was the mentor for the project, and substantially revised the text. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for this study/paper.

Data availability

The dataset used and analyzed during the current study is available by request from the corresponding author. The dataset is available by request as the survey responses are not publicly published due to the vast amount of responses received during the data collection period.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Climbing Business Journal. Gyms and trends 2021. Climbing Business Journal. https://www.climbingbusinessjournal.com/gyms-and-trends-2021/. Published February 15, 2022. Accessed 26 Oct 2022.

- 2.Thaller L, Frühauf A, Heimbeck A, Voderholzer U, Kopp M. A comparison of acute effects of climbing therapy with nordic walking for inpatient adults with mental health disorder: a clinical pilot trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(11):6767. 10.3390/ijerph19116767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langer K, Simon C, Wiemeyer J. Strength training in climbing: a systematic review. J Strength Conditioning Res. 2022;37:751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mangan K, Andrews K, Miles B, Draper N. The psychology of rock climbing: a systematic review. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2025;76:102763. 10.1016/j.psychsport.2024.102763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giles LV, Rhodes EC, Taunton JE. The physiology of rock climbing. Sports Med. 2006;36(6):529–45. 10.2165/00007256-200636060-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Villavicencio P, Bravo C, Ibarz A, Solé S. Effects of acute psychological and physiological stress on rock climbers. J Clin Med. 2021;10(21):5013. 10.3390/jcm10215013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dorscht L, Karg N, Book S, Graessel E, Kornhuber J, Luttenberger K. A German climbing study on depression: a bouldering psychotherapeutic group intervention in outpatients compared with state-of-the-art cognitive behavioural group therapy and physical activation - study protocol for a multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):154. 10.1186/s12888-019-2140-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peluso MA, de Guerra Andrade LH. Physical activity and mental health: the association between exercise and mood. Clinics. 2005;60(1):61–70. 10.1590/s1807-59322005000100012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luttenberger K, Stelzer EM, Först S, Schopper M, Kornhuber J, Book S. Indoor rock climbing (bouldering) as a new treatment for depression: study design of a waitlist-controlled randomized group pilot study and the first results. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:201. 10.1186/s12888-015-0585-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bichler CS, Niedermeier M, Hüfner K, et al. Climbing as an add-on treatment option for patients with severe anxiety disorders and PTSD: feasibility analysis and first results of a randomized controlled longitudinal clinical pilot trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(18):11622. 10.3390/ijerph191811622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karg N, Dorscht L, Kornhuber J, Luttenberger K. Bouldering psychotherapy is more effective in the treatment of depression than physical exercise alone: results of a multicentre randomised controlled intervention study. BMC Psychiatry. 2020. 10.1186/s12888-020-02518-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luttenberger K, Karg-Hefner N, Berking M, et al. Bouldering psychotherapy is not inferior to cognitive behavioural therapy in the group treatment of depression: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Clin Psychol. 2022;61(2):465–93. 10.1111/bjc.12347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu S, Gong X, Li H, Li Y. The origin, application and mechanism of therapeutic climbing: a narrative review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(15):9696. 10.3390/ijerph19159696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kratzer A, Luttenberger K, Karg-Hefner N, Weiss M, Dorscht L. Bouldering psychotherapy is effective in enhancing perceived self-efficacy in people with depression: results from a multicenter randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychol. 2021;9(1):126. 10.1186/s40359-021-00627-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson RF, Perlini AH. Feedback and self-efficacy, arousal, and performance of introverts and extraverts. Psychol Rep. 1998;82(3 Pt 1):707–16. 10.2466/pr0.1998.82.3.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwarzer R, Warner LM. Perceived Self-Efficacy and its Relationship to Resilience. In: Prince-Embury S, Saklofske DH, editors. Assessing Emotional Intelligence. New York: Springer; 2013. p. 139–50. 10.1007/978-1-4614-4939-3_10. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used and analyzed during the current study is available by request from the corresponding author. The dataset is available by request as the survey responses are not publicly published due to the vast amount of responses received during the data collection period.