Abstract

Background

Cervical degenerative disc disease (DDD) significantly affects the quality of life in labor-intensive careers. When conservative measures fail, either anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) or cervical disc arthroplasty (CDA) may be indicated. Although ACDF is the gold standard, it can limit motion, whereas CDA preserves motion and may reduce adjacent segment disease (ASD). Few studies compare these surgeries in physically demanding populations, and the influence of workers’ compensation (WC) on outcomes is unclear. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to compare the outcomes of CDA versus ACDF in patients with labor-intensive jobs and to assess how workers' compensation (WC) status influences these outcomes.

Methods

In this prospective cohort study, 300 (CDA: 150, ACDF: 150) patients with 1- or 2-level cervical DDD with labor-intensive jobs were enrolled, including a subgroup of 60 WC patients (CDA: 30, ACDF: 30). Participants were followed for a minimum of 2 years. Data collected included demographic details, perioperative events, and complication rates. Functional outcomes were measured using the Visual Analog Scale for neck and arm pain (VAS-neck, VAS-arm) and the Neck Disability Index (NDI), with attention to timelines for returning to full-time work.

Results

CDA patients returned to full-time work faster (4.3 vs 6.7 months, p=.025). More CDA patients resumed work by 6 weeks (p=.018) and 3 months (p=.022), though these differences waned by 6 months. WC patients had slower returns overall (CDA WC: 7.5 vs 5.0 weeks for non-WC, p=.015). CDA showed greater NDI improvement at all time points and significantly lower ASD incidence (1.3% vs. 26.7%, p<.001). Complications were comparable.

Conclusion

CDA may facilitate faster work return, better recovery, and lower ASD risk in labor-intensive patients. WC status correlates with delayed recovery, suggesting a need for tailored approaches. Further research is necessary to confirm these findings and refine patient selection.

Keywords: Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion, Cervical disc arthroplasty, Cervical disc replacement, Complications, Patient-reported outcome measures, Workers’ compensation

Introduction

Cervical degenerative disc disease (DDD) is a common condition that affects millions of individuals worldwide, presenting with a range of symptoms from axial neck pain to cervical radiculopathy and myelopathy [1,2]. These pathologies, particularly in individuals with physically demanding careers or active lifestyles, can significantly impair daily function and quality of life. When conservative treatments fail to alleviate symptoms, surgical intervention becomes necessary. Two primary surgical options for managing cervical DDD are anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) and cervical disc arthroplasty (CDA). Traditionally, ACDF has been considered the gold standard, offering reliable symptom relief and spinal stability through fusion [3]. However, CDA has emerged as a viable alternative, preserving motion at the treated level and potentially reducing the risk of adjacent segment disease (ASD) [4,5].

While CDA has gained popularity, particularly in younger and physically active patients, the literature remains conflicted regarding its superiority over ACDF. Several studies suggest that CDA may enable an earlier return to activity due to the preservation of motion and a lower incidence of ASD, making it an attractive option for those with physically demanding careers [6]. On the other hand, some research argues that ACDF provides greater long-term stability, particularly in patients with advanced spondylotic changes, and is associated with lower reoperation rates and complications [7]. These varying outcomes raise questions about which procedure—CDA or ACDF—delivers better functional results, faster return to work, and fewer complications, especially for individuals whose careers place high mechanical stress on their cervical spine.

Despite extensive literature comparing CDA and ACDF, limited research has focused on labor-intensive populations, where the physical demands of employment create unique challenges for postoperative recovery [8,9]. Additionally, the influence of workers’ compensation (WC) status on surgical outcomes in this group remains poorly understood despite evidence linking WC to poorer surgical outcomes due to factors such as delayed recovery, psychosocial stress, and administrative barriers [10]. Labor-intensive workers often require strength, endurance, and a swift return to full physical capability, underscoring the need for targeted studies in this population. This study addresses this gap by directly comparing the outcomes of CDA and ACDF in labor-intensive occupations, focusing on postoperative function, complication rates, and return to full-time work while also evaluating the impact of WC status on these outcomes.

Methods

Study design

Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was granted for this study (PR# 22-006). All participants provided written informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study. This prospective cohort study included data collected from all patients who underwent 1- or 2-level ACDF or CDA at a single institution between 2012 and 2022. This study was not randomized; the choice of surgical method was determined by the treating surgeon based on patient-specific factors, including age, degree of cervical disc degeneration, and surgeon-patient discussions regarding the potential benefits and risks of each procedure.

Patients were followed for a minimum of 2 years, and those lost to follow-up before this time point were excluded to ensure consistent data collection and accurate capture of complications. Patients were grouped based on the procedure performed for comparative analysis, with an additional sub-analysis stratifying patient by WC status to evaluate its impact on outcomes. Fig. 1 illustrates the patient selection process, including those patients screened, excluded (with reasons), and those included in the final analysis.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of patient screening, exclusion, and final inclusion for study analysis. ACDF, anterior cervical discectomy and fusion; CDA, cervical disc arthroplasty.

To minimize variability in cervical degeneration, inclusion criteria required all patients to have cervical DDD with similar degrees of degeneration, limited explicitly to mild to moderate degenerative changes (Fig. 2). Severe degeneration, such as multilevel spondylotic myelopathy or advanced kyphotic deformities, was excluded to standardize preoperative spinal balance and degenerative status across cohorts. Spinal balance was maintained by ensuring that all patients had preoperative cervical sagittal vertical axis (SVA) within normal parameters (<40mm), as deviations from normal SVA have been linked to poorer surgical outcomes [11] (Fig. 3). Two fellowship-trained orthopedic spine surgeons assessed these radiographic determinants.

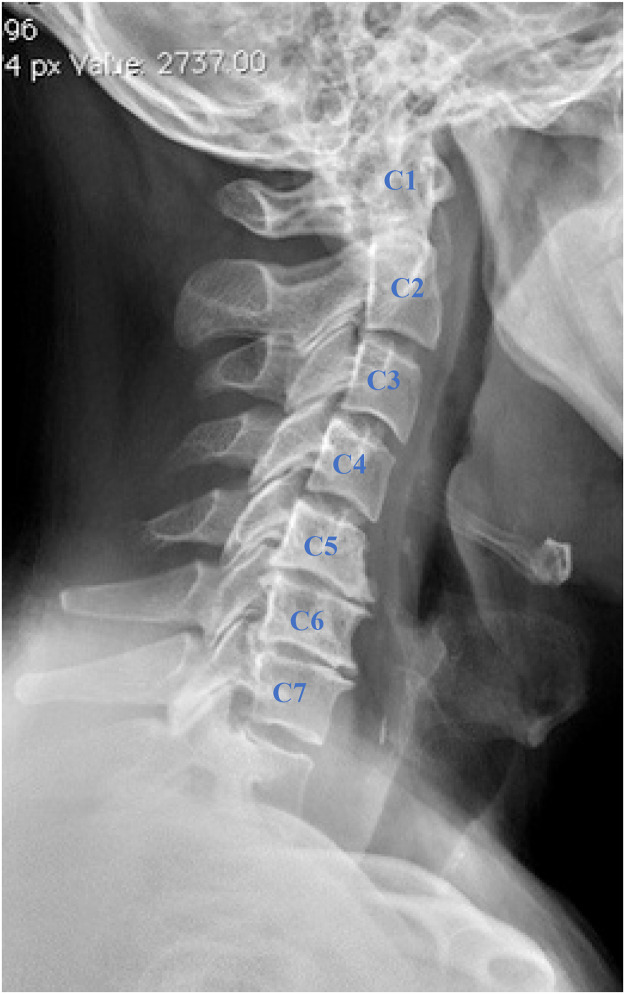

Fig. 2.

Lateral cervical spine x-ray of a patient with mild to moderate cervical degenerative disc disease illustrating disc space narrowing at C5-C6 and C6-C7 levels and the formation of anterior osteophytes.

Fig. 3.

C2-7 sagittal vertical axis (SVA) is calculated by measuring the horizontal distance between the posterosuperior corner of the C7 vertebral body and a plumb line drawn from the centroid of C2. Patients with a preoperative SVA ≥40mm were excluded from our study.

Workers' compensation sub-analysis

WC status was documented for all patients based on medical records and self-reports. WC claimants were defined as those receiving benefits for work-related injuries associated with cervical DDD. Of the 300 patients, 60 (20%) were WC claimants, 30 were in the CDA group, and 30 were in the ACDF group (Table 1). WC status was included as a variable to assess its impact on return-to-work timelines and patient-reported outcomes. Subgroup analyses comparing WC and non-WC patients were performed to identify any significant differences in recovery trajectories and outcomes.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and operative characteristics by surgical group.

| CDA | ACDF | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 150 | 150 | - |

| Age (years) | 47.6 (6.3) | 46.8 (7.0) | .412 |

| Workers’ compensation | 30 (20.0%) | 30 (20.0%) | 1.00 |

| Non-Workers’ compensation | 120 (80.0%) | 120 (80.0%) | 1.00 |

| Male (%) | 92 (61.3%) | 88 (58.7%) | .673 |

| Female (%) | 58 (38.7%) | 62 (41.3%) | .673 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.5 (4.8) | 30.6 (5.0) | .842 |

| Tobacco use (%) | 15 (10.0%) | 7 (4.7%) | .08 |

| Alcohol use (%) | 18 (12.0%) | 15 (10.0%) | .621 |

| 1-Level (%) | 70 (46.7%) | 68 (45.3%) | .781 |

| 2-Level (%) | 80 (53.3%) | 82 (54.7%) | .781 |

ACDF, anterior cervical discectomy and fusion; BMI, body mass index; CDA, cervical disc arthroplasty. Values represent the number of patients (%) or mean (standard deviation).

Patient selection

Inclusion criteria included adult patients (≥18 years of age) with mild to moderate cervical DDD as the operative indication, 1- or 2-level cervical procedures between C3-C7, patients performing labor-intensive occupations, and the availability of complete medical records. Diagnoses included myeloradiculopathy, axial neck pain, cervical disc degeneration, and spinal stenosis. Labor-intensive occupations were defined as those involving regular physical exertion, such as heavy lifting, repetitive motion, prolonged standing, bending, or twisting. Occupations were selected based on established evidence of cervical spine loading, including non-neutral postures and repetitive or forceful neck movements [12,13]. For example, construction workers experience an increased risk for cervical spondylosis due to prolonged static postures and high upper extremity loads [12], while head-loading tasks in manual laborers have been shown to reduce cervical lordosis and exacerbate degenerative changes significantly [13]. The detailed list of patient occupations in our study is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of occupations between CDA and ACDF cohorts.

| Occupation | CDA (n=150) | ACDF (n=150) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Construction workers | 18 | 20 | .714 |

| Electrician | 11 | 12 | .832 |

| Agricultural worker | 9 | 8 | .774 |

| Roofer | 7 | 9 | .653 |

| Carpenter | 13 | 14 | .841 |

| Plumber | 9 | 10 | .814 |

| Mason/Bricklayer | 7 | 6 | .752 |

| Heating, ventilation, and air conditioning technician | 5 | 6 | .752 |

| Long-haul truck driver | 14 | 13 | .821 |

| Healthcare worker | 6 | 5 | .832 |

| Warehouse forklift operator | 7 | 6 | .774 |

| Landscaper/Gardener | 6 | 5 | .752 |

| Athlete | 5 | 4 | .684 |

| Firefighter | 5 | 6 | .752 |

| Overhead crane operator | 7 | 5 | .774 |

| Lineman | 4 | 4 | .652 |

| Drywall installer | 5 | 4 | .684 |

| Active military personnel | 3 | 4 | .752 |

| Cleaner/Janitor | 9 | 9 | .832 |

ACDF, anterior cervical discectomy and fusion; CDA, cervical disc arthroplasty.

Exclusion criteria included pediatric patients (<18 years of age), prior cervical spine surgery, corticosteroid use, morbid obesity (BMI ≥ 40), pregnancy, hybrid constructs (eg, 1-level ACDF and 1-level CDA), missing data, and surgery related to trauma, malignancy, or infection. Patients with metabolic bone disease, spondyloarthropathies (eg, ankylosing spondylitis, rheumatoid arthritis), segmental instability (>3.5mm translation or >20° angular motion), nonmobile segmental arthrodesis (<2° range of motion on flexion/extension radiographs), severe facet joint arthropathy, ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament, or kyphotic deformity at the index level were also excluded. Two fellowship-trained orthopedic spine surgeons assessed these radiographic determinants.

Complete medical records were reviewed, including history, imaging, progress notes, operative reports, discharge summaries, office visit notes, and functional outcome questionnaires. Demographic data, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), and medical history (eg, diabetes, tobacco use, alcohol use), were collected. Operative details such as the number of levels, estimated blood loss (EBL), operative time, length of stay, and perioperative complications (eg, dysphagia, dysphonia, infection, heterotopic ossification [HO], revisions, adjacent segment disease [ASD]) were also collected.

HO was assessed using the method described by McAfee et al.[14]. ASD was defined by clinical symptoms (radiculopathy or myelopathy) correlating to a motion segment adjacent to the construct, combined with radiographic evidence of degeneration at the corresponding level. Radiographic evidence of ASD was evaluated by 2 board-certified orthopedic spine surgeons using the classification system by Goffin et al.[15], which included changes in disc height and anterior osteophyte formation. Discrepancies in interpretation were resolved through consensus.

Operative procedure

All procedures were performed by 4 fellowship-trained orthopedic spine surgeons, always utilizing the same technique. A standard anterior approach to the cervical spine was employed. For ACDF procedures, Caspar pin distraction, radical discectomy, and decortication were employed before the placement of plates and locking, self-tapping, and self-drilling screws.

For CDA procedures, decompression and uniform interspace distraction were achieved, and trials were placed within the disc space. Upon selecting the appropriate-sized implant, the corresponding Mobi-C (ZimVie, Westminster, Colorado, USA) or ProDisc-C (Centinel Spine, West Chester, Pennsylvania, USA) device was impacted within the intervertebral disc space under x-ray guidance. In this study, 76 patients received the Mobi-C implant, and 74 received the ProDisc-C implant. The choice of implant was based on surgeon preference at the time of surgery and patient-specific anatomical considerations. No surgeon switched implant choice during the study due to complications.

For both procedures, once adequate hemostasis was achieved, the wound was thoroughly irrigated, and a deep drain was placed. The fascia was closed with absorbable vicryl suture, and the skin was closed with a running subcuticular absorbable monocryl suture. No corticosteroids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications were routinely given to the patients following either procedure during the perioperative or postoperative periods.

Postoperative care protocol

The postoperative care protocol for ACDF and CDA patients adhered to standardized guidelines to promote optimal recovery and safe return to work. Cervical collars were used at the surgeon's discretion for ACDF patients, particularly in cases of poor bone quality, smoking history, or osteoporosis, and were typically discontinued within 6–12 weeks. For CDA patients, collars were less commonly recommended, consistent with motion-preserving principles. Gentle neck movements were encouraged postoperatively unless contraindicated by intraoperative findings.

Physical therapy (PT) began 4–6 weeks postoperatively for ACDF patients and 1–6 weeks for CDA patients. Early PT objectives focused on pain control, mobility restoration, and progressive strength and endurance. Interventions included walking programs, cervical and scapulothoracic stabilization exercises, and aerobic conditioning using treadmills or recumbent bikes.

For both groups, initial lifting restrictions were set at 5–10 pounds for the first 6 weeks, increasing incrementally by 5 pounds every 2 weeks. Overhead lifting was restricted until 8 weeks. Given the labor-intensive occupations of all patients, a phased return-to-work protocol was implemented:

-

•

Weeks 6–12: Moderate duties with lifting limits ≤20 pounds.

-

•

Weeks 12–24: Full-duty activities with lifting limits ≥40 pounds as tolerated.

Running, jogging, and contact sports were restricted until 6 months postoperatively. By 3 months, patients were expected to achieve functional cervical and shoulder range of motion (ROM) and independence with a home exercise program. Discharge goals included minimal or no activity-related pain, normalized cervical ROM, and achievement of patient-specific functional outcomes, as assessed by the Visual Analog Scale for neck (VAS-neck) and arm (VAS-arm) and Neck Disability Index (NDI).

Patient assessment

Patients were assessed preoperatively and followed postoperatively at 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years. Patient-reported outcome measures (NDI, VAS-neck, VAS-arm pain) and full-time work status were collected at the preoperative and each postoperative office visit. At each postoperative office visit, we asked patients if they had returned to work and, if so, whether they were working part-time or full-time. Full-time work status was validated with work records.

Statistical analysis

All data were de-identified and tabulated into an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA) for analysis. Univariate analysis was conducted to compare demographics, mean VAS-neck and VAS-arm scores, revision rates, complication rates, radiographic outcomes, and perioperative data between the ACDF and CDA cohorts. Subgroup analysis was performed to evaluate differences between WC and non-WC patients, focusing on return-to-work timelines and patient-reported outcomes.

Given the unequal sample sizes between WC and non-WC groups, standardized mean differences (SMDs) were calculated in addition to p-values to assess effect size for comparisons involving categorical or dichotomous variables. For categorical variables, chi-squared tests or Fisher's exact tests (when cell counts were <5) were performed with appropriate adjustments. Continuity correction or Monte Carlo simulations were applied to further account for small cell counts where necessary.

For the NDI outcome score, an ordinal variable, the Mann-Whitney U test was used to assess whether statistically significant differences existed. For continuous variables with unequal sample sizes, Welch's t-test was used to account for unequal variances. Multivariable regression models were employed to adjust for potential confounders, including age, BMI, smoking status, and preoperative NDI scores, with WC status included as an independent variable. Interaction terms were tested to determine whether WC status modified the effect of surgical procedures on outcomes.

To ensure robustness, sensitivity analyses were conducted to confirm findings under different assumptions, including bootstrapping techniques for nonparametric variables. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 24.0 (IBM Corp., Amonk, NY, USA), and p-values <.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient sample

Patient demographic data are shown in Table 1. Three hundred patients met the inclusion criteria and were included in our study: 150 underwent CDA, and 150 underwent ACDF. Of these, 60 (20%) were WC claimants, with 30 patients in each surgical cohort. No significant differences were observed in age (p=.412), workers’ compensation status (p=1.00), sex (p=.673), BMI (p=.842), the proportion of tobacco users (p=.08), or the proportion of alcohol users (p=.621). No significant differences were observed in the number of operative levels between the 2 groups. For 1-level procedures, 70 patients underwent CDA, and 68 underwent ACDF (p=.781), while for 2-level procedures, 80 patients underwent CDA, and 82 underwent ACDF (p=.781).

Across all occupations evaluated, no statistically significant differences were observed between the CDA and ACDF groups (Table 2). Construction workers, long-haul truck drivers, and carpenters were the most common occupations in both groups (Table 2).

Perioperative outcomes

Table 3 shows perioperative data between the 2 cohorts. EBL (p=.284), operative times (p=.462), and length of hospital stay (p=.347) were similar between the CDA and ACDF groups.

Table 3.

Perioperative data by surgical group.

| CDA (n=150) | ACDF (n=150) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| EBL (mL) | 17.0 (3.0) | 15.8 (3.5) | .284 |

| Operative time (min) | 106.5 (5.1) | 104.3 (5.4) | .462 |

| Length of stay (days) | 2.1 (0.8) | 2.0 (0.7) | .347 |

ACDF, anterior cervical discectomy and fusion; CDA, cervical disc arthroplasty; EBL, estimated blood loss. Values represent the mean (standard deviation).

Return to full-time work

Table 4 compares return-to-full-time-work data between the ACDF and CDA cohorts. Preoperatively, all patients in our study were full-time employees in a labor-intensive occupation. By 6 weeks (p=.018) and 3 months (p=.022), postoperatively, significantly more patients in the CDA group had returned to full-time work compared to those in the ACDF group. However, by 6 months postoperatively and continuing through 2 years, there were no significant differences in the number of patients returning to full-time work between the 2 groups (6 months: p=.072; 1 year: p=.091). At the 2-year final follow-up, there were no significant differences in the number of patients returning to full-time work between patients undergoing CDA and ACDF (p=.058).

Table 4.

Return to full-time work proportions by surgical group.

| Timepoint | Total CDA (n=150) | Total ACDF (n=150) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative (%) | 150 (100%) | 150 (100%) | 1.00 |

| 6 weeks postop (%) | 70 (46.7%) | 50 (33.3%) | .018 |

| 3 months postop (%) | 105 (70.0%) | 85 (56.7%) | .022 |

| 6 months postop (%) | 125 (83.3%) | 110 (73.3%) | .072 |

| 1-year postop (%) | 140 (93.3%) | 128 (85.3%) | .091 |

| 2-year postop (%) | 145 (96.7%) | 135 (90.0%) | .058 |

ACDF, anterior cervical discectomy and fusion; CDA, cervical disc arthroplasty; WC, workers’ compensation. Bolded values indicate significance at a 95% confidence level.

Our sub-analysis revealed that WC patients consistently had lower rates of return to full-time work compared to non-WC patients following both CDA and ACDF (Table 5). At 6 weeks postoperatively, return-to-work rates were significantly lower in WC patients for CDA (33.3% vs 60.0%, p=.014) and ACDF (26.7% vs 41.7%, p=.021). This trend persisted across all postoperative timepoints, with WC patients showing reduced return-to-work rates at 3 months, 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years postoperatively. By 2 years, 86.7% of CDA WC patients returned to work compared to 95.8% of non-WC patients (p=.037), and 80.0% of ACDF WC patients returned compared to 90.0% of non-WC patients (p=.041).

Table 5.

Sub-analysis evaluating return to full-time work proportions by workers’ compensation status.

| Timepoint | CDA WC (n=30) | CDA non-WC (n=120) | *p-value (CDA WC vs. non-WC) | ACDF WC (n=30) | ACDF non-WC (n=120) | *p-value (ACDF WC vs. non-WC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative (%) | 30 (100%) | 120 (100%) | 1.00 | 30 (100%) | 120 (100%) | 1.00 |

| 6 weeks postop (%) | 10 (33.3%) | 72 (60.0%) | .014 | 8 (26.7%) | 50 (41.7%) | .021 |

| 3 months postop (%) | 15 (50.0%) | 95 (79.2%) | .008 | 12 (40.0%) | 70 (58.3%) | .019 |

| 6 months postop (%) | 18 (60.0%) | 100 (83.3%) | .026 | 16 (53.3%) | 85 (70.8%) | .039 |

| 1-year postop (%) | 22 (73.3%) | 108 (90.0%) | .031 | 20 (66.7%) | 98 (81.7%) | .045 |

| 2-year postop (%) | 26 (86.7%) | 115 (95.8%) | .037 | 24 (80.0%) | 108 (90.0%) | .041 |

ACDF, anterior cervical discectomy and fusion; CDA, cervical disc arthroplasty; WC, workers’ compensation. Bolded values indicate significance at a 95% confidence level. *To address the differences in sample size and reduce the risk of Type I error due to multiple comparisons, Bonferroni-adjusted p-values were applied to the p-values for group comparisons between WC and non-WC cohorts within CDA and ACDF groups.

The time to return to full-time work was significantly shorter in the CDA group, with patients returning at an average of 4.3 months compared to 6.7 months in the ACDF group (p=.025) (Table 6). Our sub-analysis of time to return to full-time work revealed that WC patients experienced significantly longer return-to-work times than non-WC patients for CDA and ACDF cohorts (Table 7). WC patients undergoing CDA returned to full-time work in an average of 7.5 weeks versus 5.0 weeks for non-WC patients (p=.015). Similarly, WC patients treated with ACDF returned to full-time work in 8.2 weeks compared to 6.1 weeks for non-WC patients (p=.010).

Table 6.

Time to return to full-time work by surgical group.

| Timepoint | CDA (n=150) | ACDF (n=150) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean time to return to full-time work (months) | 4.3 (1.3) | 6.7 (1.7) | .025 |

ACDF, anterior cervical discectomy and fusion; CDA, cervical disc arthroplasty. Values represent the mean (standard deviation). Bolded values indicate significance at a 95% confidence level.

Table 7.

Sub-analysis evaluating time to return to full-time work (week) by workers’ compensation status.

| Group | Workers’ Compensation (n=60) | Non-workers Compensation (n=240) | *p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CDA | 7.5 (2.3) | 5.0 (1.7) | .015 |

| ACDF | 8.2 (2.1) | 6.1 (1.8) | .010 |

ACDF, anterior cervical discectomy and fusion; CDA, cervical disc arthroplasty. Values represent the mean (standard deviation). Bolded values indicate significance at a 95% confidence level. *To address the differences in sample size and reduce the risk of Type I error due to multiple comparisons, Bonferroni-adjusted p-values were applied to the p-values for group comparisons between WC and non-WC cohorts within CDA and ACDF groups.

Patient-reported outcome measures

Median NDI and mean VAS scores are recorded and compared between CDA and ACDF cohorts in Table 8. Mean preoperative VAS-neck (p=.731) and VAS-arm (p=.836) and median preoperative NDI scores (p=.412) were comparable between the 2 groups. Statistically significant improvements in median NDI scores were observed in the CDA cohort at 6 weeks (p=.002), 3 months (p=.032), 6 months (p=.031), 1 year (p=.044), and 2 years (p=.026) postoperatively. The CDA group also demonstrated a greater mean overall improvement in NDI scores (CDA: 28.0 vs ACDF: 29.0, p=.038). However, no statistically significant differences were observed between the groups regarding VAS-neck or VAS-arm scores at any postoperative time point.

Table 8.

Patient-reported outcome measures among surgical groups.

| Patient reported outcome measure | Timepoint | Total CDA (n=150) | Total ACDF (n=150) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean VAS-neck | Preoperative | 7.2 | 7.3 | .731 |

| 6 weeks postop | 6.5 | 6.4 | .213 | |

| 3 months postop | 5.6 | 5.5 | .178 | |

| 6 months postop | 4.8 | 4.9 | .193 | |

| 1-year postop | 4.3 | 4.5 | .172 | |

| 2-year postop | 3.8 | 3.9 | .180 | |

| Mean Improvement | 3.3 | 3.6 | .293 | |

| Mean VAS-arm | Preoperative | 7.0 | 7.2 | .836 |

| 6 weeks postop | 6.3 | 6.2 | .335 | |

| 3 months postop | 5.2 | 5.4 | .287 | |

| 6 months postop | 4.5 | 47 | .361 | |

| 1-year postop | 4.0 | 4.3 | .344 | |

| 2-year postop | 3.7 | 3.8 | .389 | |

| Mean Improvement | 3.7 | 3.9 | .433 | |

| Median NDI | Preoperative | 39 | 40 | .412 |

| 6 weeks postop | 34 | 38 | .002 | |

| 3 months postop | 28 | 30 | .032 | |

| 6 months postop | 24 | 25 | .031 | |

| 1-year postop | 20 | 22 | .044 | |

| 2-year postop | 12 | 14 | .026 | |

| Mean Improvement | 27 | 26 | .038 |

ACDF, anterior cervical discectomy and fusion; CDA, cervical disc arthroplasty; NDI, Neck Disability Index; VAS, Visual Analog Scale. Values represent the mean (standard deviation). Bolded values indicate significance at a 95% confidence level. Bolded values indicate significance at a 95% confidence level.

WC patients showed slower improvement in NDI scores compared to non-WC patients, with significant differences at all postoperative time points (Table 9). However, no statistically significant differences were observed between WC and non-WC patients regarding VAS-neck or VAS-arm scores at any postoperative time.

Table 9.

Sub-analysis evaluating patient-reported outcome measures by workers’ compensation status.

| Patient Reported Outcome Measure | Timepoint | CDA WC (n=30) | CDA non-WC (n=120) | *p-value (CDA WC vs non-WC) | ACDF WC (n=30) | ACDF non-WC (n=120) | *p-value (ACDF WC vs non-WC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean VAS-neck | Preoperative | 7.3 | 7.1 | .827 | 7.3 | 7.2 | .796 |

| 6 weeks postop | 6.6 | 6.4 | .285 | 6.5 | 6.3 | .278 | |

| 3 months postop | 5.7 | 5.5 | .317 | 5.8 | 5.6 | .324 | |

| 6 months postop | 4.9 | 4.8 | .341 | 5.0 | 4.9 | .374 | |

| 1-year postop | 4.4 | 4.3 | .412 | 4.6 | 4.5 | .419 | |

| 2-year postop | 4.0 | 3.9 | .378 | 4.1 | 4.0 | .393 | |

| Mean Improvement | 3.3 | 3.2 | .283 | 3.2 | 3.2 | .289 | |

| Mean VAS-arm | Preoperative | 7.1 | 7.0 | .796 | 7.2 | 7.1 | .796 |

| 6 weeks postop | 6.2 | 6.1 | .312 | 6.3 | 6.2 | .312 | |

| 3 months postop | 5.3 | 5.2 | .346 | 5.4 | 5.3 | .346 | |

| 6 months postop | 4.6 | 4.5 | .398 | 4.7 | 4.5 | .398 | |

| 1-year postop | 4.1 | 4.0 | .421 | 4.2 | 4.1 | .421 | |

| 2-year postop | 3.8 | 3.7 | .405 | 3.7 | 3.9 | .405 | |

| Mean Improvement | 3.3 | 3.3 | .287 | 3.5 | 3.2 | .292 | |

| Median NDI | Preoperative | 39 | 38 | .412 | 40 | 39 | .412 |

| 6 weeks postop | 36 | 34 | .048 | 38 | 35 | .041 | |

| 3 months postop | 30 | 28 | .032 | 30 | 28 | .031 | |

| 6 months postop | 25 | 23 | .031 | 25 | 23 | .042 | |

| 1-year postop | 21 | 20 | .044 | 22 | 20 | .048 | |

| 2-year postop | 14 | 12 | .026 | 14 | 12 | .039 | |

| Mean Improvement | 25 | 26 | .039 | 26 | 27 | .038 |

ACDF, anterior cervical discectomy and fusion; CDA, cervical disc arthroplasty; VAS, Visual Analog Scale; NDI, Neck Disability Index. Values represent the mean (standard deviation). Bolded values indicate significance at a 95% confidence level. *To address the differences in sample size and reduce the risk of Type I error due to multiple comparisons, Bonferroni-adjusted p-values were applied to the p-values for group comparisons between WC and non-WC cohorts within CDA and ACDF groups.

Postoperative complications

Postoperative complications are summarized in Table 10, with no significant differences observed in the rates of dysphagia (p=.812), dysphonia (p=.543), infection (p=.421), HO (p=.738), or revisions (p=.712) between the ACDF and CDA groups. ASD was reported in 40 (26.7%) of ACDF patients, while 2 (1.3%) cases were noted in the CDA group (p<.001).

Table 10.

Postoperative complications by surgical group.

| Complications | CDA (n=150) | ACDF (n=150) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dysphagia (%) | 15 (10.0%) | 14 (9.3%) | .812 |

| Dysphonia (%) | 7 (4.7%) | 5 (3.3%) | .543 |

| Infection (%) | 2 (1.3%) | 4 (2.7%) | .421 |

| HO (%) | 24 (16.0%) | 22 (14.7%) | .738 |

| ASD (%) | 2 (1.3%) | 40 (26.7%) | <.001 |

| Revisions (%) | 3 (2.0%) | 4 (2.7%) | .712 |

ASD, adjacent segment disease; ACDF, anterior cervical discectomy and fusion; CDA, cervical disc arthroplasty; HO, heterotopic ossification. Values represent the number of patients (%). Bolded values indicate significance at a 95% confidence level.

Discussion

Cervical DDD frequently requires surgical intervention when conservative treatments fail, particularly in patients engaged in physically demanding occupations. Two primary surgical options, ACDF and CDA, are commonly utilized. ACDF has long been the gold standard for addressing cervical DDD due to its efficacy in stabilizing the spine through fusion [3]. However, CDA offers the potential advantage of motion preservation at the operative level, reducing the risk of ASD [4,5]. Despite the growing popularity of CDA, the optimal surgical approach for patients with physically demanding occupations remains unclear. Thus, we sought to compare CDA and ACDF regarding functional outcomes, complication rates, and return to full-time work in labor-intensive occupations. In addition, we performed a sub-analysis to evaluate the impact of WC status on these outcomes.

We found that patients undergoing CDA returned to full-time work sooner, had superior improvements in NDI scores, and experienced lower rates of ASD compared to ACDF. Importantly, our sub-analysis revealed that WC patients returned to work more slowly and had delayed improvement in NDI scores regardless of the surgical procedure performed.

Patients who underwent CDA returned to work sooner after surgery, consistent with previous studies. Traynelis et al. [16] systematically reviewed return-to-work rates and activity profiles in patients undergoing CDA and ACDF and found that CDA patients tended to return to work more quickly. This may be attributed to the early mobility and motion preservation provided by CDA, facilitating quicker functional recovery. The lack of postoperative immobilization and fusion-related complications, such as nonunion or pseudarthrosis, further supports CDA's role in enabling a faster return to work compared to ACDF [[4], [5], [6]]. However, by 2 years postoperatively, there was no significant difference in return-to-work rates between the CDA and ACDF cohorts, indicating that both procedures may be effective for cervical DDD, with most patients eventually resuming normal productivity.

Our study found that WC patients experienced significant delays in returning to work compared to non-WC patients, regardless of the surgical procedure performed. WC patients also reported slower improvements in NDI scores, which may be influenced by administrative delays, psychosocial stressors, or lower intrinsic motivation. These findings align with prior research highlighting the negative influence of WC on surgical outcomes, particularly in physically demanding populations [10].

Regarding functional outcomes, CDA patients showed greater improvements in NDI scores compared to those who underwent ACDF. This aligns with a meta-analysis by Muheremu et al. [17], which reported that CDA patients achieved better NDI scores postoperatively. These results suggest that CDA may provide a more robust recovery trajectory for patients with high physical demands who benefit from preserving motion at the operative level.

ASD rates were significantly lower in the CDA cohort, consistent with literature demonstrating that motion preservation reduces mechanical stress on adjacent segments. Prior research supports this finding, reaffirming CDA's advantage in reducing the risk of ASD compared to ACDF, where fusion creates additional stress on adjacent levels, potentially leading to degeneration [4,5].

Complication rates, including dysphagia, dysphonia, and infection, were comparable between CDA and ACDF groups in our study, echoing findings from previous long-term follow-up studies. Loidolt et al.[18] found no significant differences in complication rates between the 2 procedures.

Despite these valuable insights, our study has several limitations. First, the 2-year follow-up may not capture long-term complications such as ASD or HO, which often manifest years after surgery [19,20]. Second, the single-institution setting may introduce bias and limit generalizability. Third, the lack of randomization between ACDF and CDA patients raises the potential for confounding variables. Fourth, our reliance on patient-reported outcomes, though valuable, may be influenced by individual expectations and subjective factors. Fifth, our study used specific CDA implant types, which may limit generalizability to other implants. Lastly, we used a simplified definition of labor-intensive occupations based on general physical demands such as heavy lifting and repetitive motion. This classification may not fully capture the range of occupational demands, potentially introducing variability in the applicability of our findings.

Despite these limitations, our study offers meaningful insights into cervical spine surgery, particularly the advantages of CDA in labor-intensive populations. The sub-analysis of WC patients highlights the unique challenges faced by this subgroup, emphasizing the need for tailored perioperative strategies to optimize recovery outcomes.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that CDA may enable a faster return to full-time work, better functional recovery, and potentially lower risk of ASD compared to ACDF in patients with physically demanding occupations. We found that WC status may contribute to delayed recovery and return to full-time work rates, emphasizing the challenges faced by this subgroup. These findings highlight the potential benefits of CDA in labor-intensive populations and underscore the importance of developing tailored strategies to optimize outcomes for WC patients. Further long-term and multicenter studies are needed to confirm these observations and refine patient selection criteria.

Declaration of competing interest

Arash Emami, MD receives research support from NuVasive Spine. Ki Hwang, MD receives consulting fees from Stryker Spine. Nikhil Sahai, MD receives consulting fees from Stryker Spine. Dollar amounts specified in ICMJE disclosures provided. No relevant disclosures for any others pertaining to the present study. The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Funding

Authors received no grants, technical support or corporate support.

Footnotes

FDA device/drug status: Not applicable.

Author disclosures: HU: GA: Nothing to disclose. NP: Nothing to disclose. DC: Nothing to disclose. SC: Nothing to disclose. NS: receives consulting fees from Stryker Spine (Level A-$100-$1,000). KS: Nothing to disclose. KH: receives consulting fees from Stryker Spine (Level A-$100-$1,000). AE: receives research support from NuVasive Spine (Level A-$100-$1,000).

Presentations: Society for Minimally Invasive Spine Surgery (SMISS) Annual Forum 2024, American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) Annual Meeting 2025.

Copyrighted Materials: The authors provide full permission to reproduce copyrighted material presented in the title page, structured abstract, key points, mini abstract, manuscript text, tables, and figures.

IRB Approval/Research Ethics Committee: The authors were granted IRB approval (PR#22-006) by the IRB board at St. Joseph's University Medical Center, Paterson, NJ 07503.

References

- 1.Waldman S.D. In: Atlas of Common Pain Syndromes. 5th ed. Waldman SD, editor. Elsevier; Kansas City, MO: 2024. Cervical radiculopathy; pp. 72–76. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saunders L.M., Sandhu H.S., McBride L., et al. Degenerative cervical myelopathy: an overview. Cureus. 2023;15(12):e50387. doi: 10.7759/cureus.50387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jason C., Eck S.C., Humphreys S.D., Hodges L.P. A comparison of outcomes of anterior cervical discectomy and fusion in patients with and without radicular symptoms. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2005;15(1):24–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhong Z.M., Li M., Han Z.M., et al. Does cervical disc arthroplasty have lower incidence of dysphagia than anterior cervical discectomy and fusion? A meta-analysis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2016;146:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Y., Liang C., Tao Y., et al. Cervical total disc replacement is superior to anterior cervical decompression and fusion: a meta-analysis of prospective randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steinmetz M.P., Patel R., Traynelis V., Resnick D.K., Anderson P.A. Cervical disc arthroplasty compared with fusion in a workers' compensation population. Neurosurgery. 2008;63(4):741–747. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000325495.79104.DB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caruso R., Pesce A., Marrocco L., Wierzbicki V. Anterior approach to the cervical spine for treatment of spondylosis or disc herniation: long-term results. Comparison between ACD, ACDF, TDR. Clin Ter. 2014;165(4):e263–e270. doi: 10.7417/CT.2014.1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bohlman H.H., Emery S.E., Goodfellow D.B., et al. Robinson anterior cervical discectomy and arthrodesis for cervical radiculopathy. Long-term follow-up of one hundred and twenty-two patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:1298–1307. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199309000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murrey D., Janssen M., Delamarter R., et al. Results of the prospective, randomized, controlled multicenter Food and Drug Administration investigational device exemption study of the ProDisc-C total disc replacement versus anterior discectomy and fusion for the treatment of 1-level symptomatic cervical disc disease. Spine J. 2009;9:275–286. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris I., Mulford J., Solomon M., van Gelder J.M., Young J. Association between compensation status and outcome after surgery: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2005;293(13):1644–1652. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.13.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scheer J.K., Tang J.A., Smith J.S., et al. Cervical spine alignment, sagittal deformity, and clinical implications: a review. J Neurosurg: Spine SPI. 2013;19(2):141–159. doi: 10.3171/2013.4.SPINE12838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jackson J.A., Liv P., Sayed-Noor A.S., Punnett L., Wahlström J. Risk factors for surgically treated cervical spondylosis in male construction workers: a 20-year prospective study. Spine J. 2023;23(1):136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2022.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dave B.R., Krishnan A., Rai R.R., Degulmadi D., Mayi S. The effect of head loading on cervical spine in manual laborers. Asian Spine J. 2021;15(1):17–22. doi: 10.31616/asj.2019.0221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McAfee P.C., Cunningham B.W., Devine J., Williams E., Yu-Yahiro J. Classification of heterotopic ossification (HO) in artificial disk replacement. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2003;16(4):384–389. doi: 10.1097/00024720-200308000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goffin J., Geusens E., Vantomme N., et al. Long-term follow-up after interbody fusion of the cervical spine. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2004;17(2):79–85. doi: 10.1097/00024720-200404000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Traynelis V.C., Leigh B.C., Skelly A.C. Return to work rates and activity profiles: are there differences between those receiving C-ADR and ACDF? Evid Based Spine Care J. 2012;3(Suppl 1):47–52. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1298608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muheremu A., Niu X., Wu Z., Muhanmode Y., Tian W. Comparison of the short- and long-term treatment effect of cervical disk replacement and anterior cervical disk fusion: a meta-analysis. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2015;25(Suppl 1):S87–100. doi: 10.1007/s00590-014-1469-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loidolt T., Kurra S., Riew K.D., et al. Comparison of adverse events between cervical disc arthroplasty and anterior cervical discectomy and fusion: a 10-year follow-up. Spine J. 2021;21(2):253–264. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2020.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hilibrand A.S., Carlson G.D., Palumbo M.A., Jones P.K., Bohlman H.H. Radiculopathy and myelopathy at segments adjacent to the site of a previous anterior cervical arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81(4):519–528. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199904000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsu C.H., Kuo Y.H., Kuo C.H., Ko C.C., Wu J.C., Huang W.C. Late complication of cervical disc arthroplasty: heterotopic ossification causing myelopathy after 10 years. Illustrative case. J Neurosurg Case Lessons. 2021;2(8):CASE21351. doi: 10.3171/CASE21351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]