Abstract

Chlorinated phthalocyanines—TiPcCl₂, MnPcCl, InPcCl, and AlPcCl—were studied as organic semiconductors and, in this framework, their behavior as a buffer layer. Initially, these metallophthalocyanines were characterized in solution using UV–visible spectroscopy to determine their optical band gaps, with results compared to density functional theory (DFT) calculations. The phthalocyanines were subsequently deposited as films via high-vacuum sublimation, and optically characterized to assess their reflectance and band gaps using the Kubelka-Munk function, with the lowest band gap for MnPcCl of 1.67 eV. Morphological and mechanical characterization revealed the Knoop hardness in the range of 10–15 HK for all films, and a tensile strength highest for the InPcCl film, of 9.3x10−3 Pa. Fluorescence analysis revealed peak emission around 438 nm, corresponding to blue light. Among the compounds, InPcCl exhibited the highest emission intensity, followed by TiPcCl₂, AlPcCl, and MnPcCl. The metal at the center of chlorinated phthalocyanines was found to exert a determining effect on the properties of semiconductor films. Finally, single-layer devices were fabricated and examined under various illumination conditions to analyze their current-voltage (I-V) and power-voltage (P-V) characteristics and their electrical conductivity across different temperatures. The highest power obtained in the devices was 2.78 mW, while the highest electrical conductivity was 6.6x10−2 S/cm, which suggests the potential employment of these films for use in organic optoelectronics as semiconductors and buffer layers.

Keywords: Chloro metal phthalocyanine, DFT calculations, Organic semiconductor, Buffer layer, Optical properties, Electrical properties

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Chlorinated phthalocyanines were studied for applications in organic optoelectronic.

-

•

These phthalocyanines have organic semiconductor behavior in the solid-state.

-

•

Chlorinated phthalocyanines films have band gap between 2.12 and 3.61 eV.

-

•

The maximum current in electronic devices made with phthalocyanines is 3x10−3 A.

1. Introduction

Organic Light Emitting Diodes (OLEDs) have recently garnered attention due to their ultrathin, flexible structures, exceptional contrast ratio [1], their capacity to emit no light in the “off” state thus displaying true black [2], and providing reduced power consumption [3]. Despite their start as simple light sources [4], OLED technology has evolved to enhance visual performance in televisions and monitors by delivering vivid, high-contrast colors [5]. OLEDs generate artificial light through organic molecules, allowing each pixel to operate and produce light independently [2]. These semiconductor devices are typically composed of six layers. The top and bottom layers provide protection, often with a transparent sealing top layer and a glass substrate at the bottom to insulate the system. Below the top layer lies the cathode, followed by the emissive and conductive layers, both of which contain organic semiconducting molecules, and finally, the anode hole contact layer [3]. OLED operation relies on the conductive layer, which transports positive charges from the anode, and the emissive layer, which carries electrons from the cathode to generate light. The anode injects holes by removing electrons, while the cathode supplies electrons, creating an electric current within the device [2]. Encapsulated by insulating layers, this current enables electron-hole recombination in the emissive layer, producing electromagnetic radiation visible through the transparent substrate as electroluminescent light [4]. Injection efficiency is a critical parameter in such devices, dependent on the electrode's work function, which is highly sensitive to the state of a surface [6]. Recent years have brought special attention to the engineering of charge injecting contacts, where an important enhancement in OLED stability and performance has been achieved by deposition of a copper phthalocyanine buffer layer in between the transparent anode and the hole-transport layer (HTL) [6]. However, to our knowledge, very little has been studied about other phthalocyanines as buffer layers in OLEDs.

Incorporating metallophthalocyanines (MPcs) further improves OLED technology as MPcs are organic charge carriers with notable properties, including optical absorption, robust orbital conjugation [7], high chemical and thermal stabilities [8], structural versatility [9], non-toxicity, ease of processing [10], and low production costs [11]. Furthermore, one of the greatest advantages of MPcs is their ability to modify their optoelectronic behavior by means of a chloride coordination to their metallic center, and therefore, forming chloro-metallophthalocyanines (ClMPcs) [[12], [13], [14], [15]]. The chloride radical acts as an electron donor, and as ligand, facilitating charge transport along the phthalocyanine structure, through the formation of conduction channels. This is of speculative importance for the use of ClMPcs as buffer layers in organic devices such as OLEDs. ClMPcs are chemically stable and allow for gas-phase transition, making Physical Vapor Deposition (PVD) possible to obtain thin film structures without decomposition [16]. This capability significantly enhances production efficiency for low-cost semiconducting and optoelectronic technology.

Therefore, this work further explores the semiconductor properties for applications as buffer layers of titanium(IV) phthalocyanine dichloride (TiPcCl2), manganese(III) phthalocyanine chloride, (MnPcCl), indium(III) phthalocyanine chloride (InPcCl), and aluminum phthalocyanine chloride (AlPcCl). While research on these ClMPcs remains limited, TiPcCl2 is known for its stability, efficient near-infrared optical absorption spectrum, and p-type mobilities [17]. MnPcCl has been found to exhibit enhanced electrical characteristics due to interactions with oxygen [18]. Studies on InPcCl suggest that an increase in annealing temperature leads to a decrease in the energy gap, while the thermal activation energy of the electrical conductivity remains unaffected by annealing [19]. Furthermore, although AlPcCl has been primarily researched for medical applications, its high light absorption capabilities, large molar absorption coefficient, and fluorescence emissions have attracted attention to OLED technological development [20] and semiconductor behavior [21]. Reported herein is the semiconductor behavior of ClMPcs, both in solution and in thin films, presenting a novel comparison between the optical, fluorescent, and electrical properties, with variations in lighting and temperature conditions. The band gap was evaluated in solution by UV spectroscopy and the experimental data was compared with the results obtained by density functional theory (DFT) and the Kubelka-Munk function in solid-state. Additionally, the ClMPc films were topographically and mechanically characterized, including roughness, tensile strength, and Knoop hardness.

2. Materials and methods

Ti(IV)PcCl2, Mn(III)PcCl, In(III)PcCl, and Al(III)PcCl, were purchased from commercial suppliers (Sigma-Aldrich) and employed as received. Optical absorbance analysis was performed in chloroform solution 1x10−3 M, on a Genesys 10S UV–Vis Thermo Scientific spectrophotometer. Allowed by the ClMPcs’ high chemical and thermal stability, they were deposited as thin films by the physical high-vacuum sublimation method, which does not involve high-reduction or -oxidization atmospheres, or high temperatures that could affect the phthalocyanines or the substrates. Thin films were deposited onto three substrates each: high-resistivity monocrystalline n-type silicon wafer (n-Si), Corning glass slide, and fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) coated glass, acquired directly from commercial sources (Sigma-Aldrich). To ensure greater film adherence and performance, Si substrates were cleaned using a solution of 10 mL HF, 15 mL HNO3, and 300 mL H2O. Corning glass slides and FTO-coated glass were cleaned through sequential ultrasonic processing with chloroform, methanol, and acetone solvents, followed by vacuum drying. Sublimation was conducted within a high-vacuum chamber, initially vacuumed to 10−3 Torr using a mechanical pump, and subsequently to 10−6 Torr using a turbo-molecular pump for the final vacuum. Phthalocyanines as powders were individually placed in a molybdenum crucible inside the chamber and heated to 200 °C to induce a phase change to the gaseous state, allowing deposition upon contact with the room-temperature substrate slides. Deposition rates were 2.6, 1.0, 20.1, and 3.3, Å/s for TiPcCl2, MnPcCl, InPcCl, and AlPcCl, respectively. To confirm the absence of chemical degradation during the sublimation process, the ClMPcs as KBr pellets and as films on n-Si substrate were evaluated by IR spectroscopy in a Nicolet iS5-FT spectrometer, within a wavelength range of 4000 to 500 cm−1. Atomic force microscope (AFM) topographic measurements of the films on n-Si substrates were conducted in contact mode with a static probe and with a Nanosurf Naio microscope, using the Gwyddion 2.66 software. UV–vis spectroscopy of the films on glass was conducted on a UV–Vis 300 Unicam spectrophotometer. The fluorescence of the films on glass was evaluated on an FP-8550 Jasco spectrofluorometer. Current-voltage measurements were registered in single-layer devices with FTO as anode and Ag contacts as cathode using the four collinear-probe method on a Keithley 4200-SCS-PK1 voltage source with an auto-ranging pico-ammeter, under controlled lighting and temperature conditions. The lighting conditions were provided in a carousel-type lighting device made up of LEDs with the following wavelength: UV (2.70 eV), blue (2.64 eV), green (2.34 eV), yellow (2.14 eV), orange (2.0 eV), red (1.77 eV) and white in a range of −1.5 to 1.5 V at room temperature. The electrical behavior of the prepared devices was analyzed while increasing the temperature in a controlled heating device. Measurements were taken starting at room temperature, followed by increments of 10 °C, up to 100 °C. This temperature is below the decomposition temperature of all these ClMPcs and FTO. The external quantum efficiency (EQE) of the devices was obtained using a QUESA-1200 system with a LED light source from TFSC Instrument Inc., under a white light irradiation of 100 mW/cm2 from an AM1.5 solar simulator.

3. Computational calculations

DFT computational studies were performed using the M06 [22,23] method as implemented in Gaussian 16, supplemented with Grimme's dispersion correction D3 [24] employing the 6-31G(d) basis set for organic components and SDD (Stuttgart/Dresden Effective-Core Potentials) for chlorine and metallic substituents [25]. The geometries were fully optimized in chloroform using the continuum SMD (Solvent Model Density) mode. Frequency calculations were performed to ensure energy minima, which were verified to contain no negative frequencies.

4. Results and discussion

From an application perspective, the spectroscopic properties of organic semiconductors, such as phthalocyanines, are critical for their role in optoelectronic devices, where absorption drives their operation. Fig. 1(a–d) presents the absorbance spectra of ClMPcs in solution, the highest absorbance is shown by TiPcCl2 (Fig. 1a) and the lowest, with values close to zero, is shown by AlPcCl (Fig. 1d). On the other hand, in the spectra of TiPcCl2, MnPcCl (Fig. 1b) and InPcCl (Fig. 1c) it is clearly observed that, the broad spectral configuration reflects a defined vibrational structure, with Q and B bands corresponding to various π-π∗ transitions among the 18 conjugated π electrons in the phthalocyanine structure [26]. The spectra of TiPcCl2, MnPcCl and InPcCl display these two bands, the Q band in the visible range (600 nm–750 nm), and the B band in the UV range (300 nm–450 nm) [26]. The Q band is typical of ClMPcs and originates primarly from π-π∗ transitions between the π-HOMO (Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital) to the π∗-LUMO (Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital), corresponding to the transitions from the (a1u) orbital to the LUMO (eg) orbital in the phthalocyanine core [27,28]. On the other hand, the shoulder is associated with the presence of aggregated species in the solution [28]. The maximum Q-band in the spectrum of TiPcCl2 is observed at 691 nm, for MnPcCl is observed at 721 nm and for InPcCl at 690 nm, while the shoulder in the Q band occurs at 623 nm in the spectrum of TiPcCl2, at 657 nm for MnPcCl and at 620 nm for InPcCl. The presence of this low-intensity band is due to the solvent, to the chloride ions, and probably dimers are present in the phthalocyanine solutions [[29], [30], [31], [32]]. For its part, the B band results from π-π∗ electronic transitions, from the a2u and b2u orbitals to the LUMO (eg) [27]. All the spectra show the B band between 282 and 425 nm, although again the absorbance in AlPcCl is very low. In TiPcCl2, MnPcCl and InPcCl spectra, the Q band is more intense than the B band, because to the energy difference between the a1u and a2u orbitals [27].

Fig. 1.

Absorbance spectra of (a) TiPcCl2, (b) MnPcCl, (c) InPcCl and (d) AlPcCl in chloroform solution.

The optical band gap, Eopt, can be assessed from the first electronic transition from the ground state to the excited state corresponding to the promotion of 1e− from the HOMO to the LUMO of the semiconductor molecules. The Eopt was evaluated from the absorbance UV spectra, by extrapolation of the linear section of the lower energy band skirt of the spectra in Fig. 1(a–d) up to the intersection at the abscissa axis resulting in the value λ. The Eopt is then obtained from equation (1):

| (1) |

where h is the Planck constant, and c is the speed of light in vacuum. The Eopt values estimated using the data from the edge of the highest wavelength peak are presented in Table 1, and the MnPcCl shows lower Eopt in comparison to the bigger Eopt on the AlPcCl film. The change in photoactive properties of these ClMPcs could be further modified through the change of the metallic atom in the macrocycle. Meanwhile, MnPcCl exhibits the best performance as an organic semiconductor, because it has the lowest band gap and therefore, the greatest ease of charge transport.

Table 1.

Band gap, HOMO, and LUMO for ClMPcs.

| Eopt (eV) | Ecalculated (eV) | HOMOcalc (eV) | LUMOcalc (eV) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiPcCl2 | 1.74 | 1.83 | −5.3906 | −3.5647eV |

| MnPcCl | 1.60 | 1.49 | −5.2257 | −3.7394 eV |

| InPcCl | 1.75 | 2.31 | −5.3117 | −3.0022 eV |

| AlPcCl | 2.20 | 2.29 | −5.2899 | −2.996eV |

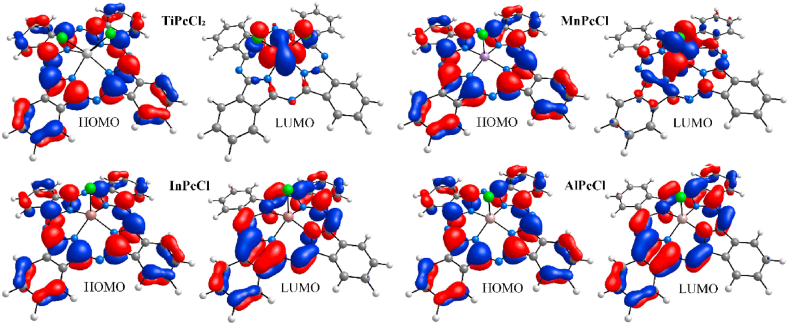

To complement the previous results, the band gap was determined theoretically, using DFT calculations. Table 1 presents both the band gap value for each chlorinated phthalocyanine, as well as its HOMO and LUMO values. MnPcCl continues to present the lowest band gap owing to different factors, such as the coordination state for Mn atom with respect to the coordination state in Ti, In, and Al atoms, the electronic configuration of Mn, and its excellent capacity to interact with the π system of the phthalocyanine ligand. Furthermore, due to the ease with which Mn participates in charge transfer, the chlorine atom can generate a more pronounced inductive effect, which affects the electron density of the conjugated phthalocyanine system. Fig. 2 shows the structures of the ClMPcs with their HOMO and LUMO molecular orbitals as calculated by DFT. The metal atoms in the ClMPcs are located outside the plane of the four nitrogen atoms, due to the displacement from the central cavity of the ligand towards the direction of the axially coordinated chlorine atom. On all four ClMPcs, the HOMO concentrates around the aromatic system, on the four peripheral isoindole units. For TiPcCl2 and MnPcCl, the LUMO is mainly condensed around the central metallic atom and chlorides, whereas for InPcCl and AlPcCl, the LUMO spreads onto the aromatic system on two opposing isoindole units.

Fig. 2.

HOMO and LUMO orbitals for the different ClMPcs.

Additionally, the electron density isosurface of the HOMO and LUMO for all the complexes was analyzed to assess polarization and charge transfer contributions through electron density movements (see Fig. 3). For TiPcCl₂, a homogeneous distribution is observed in the HOMO, with a negative orbital phase on the aromatic ring and a positive phase on the four benzene rings. In the LUMO plot, electron density increases substantially along the aromatic ring and metallic nucleus, while the benzene rings show minimal density. This suggests anisotropy in TiPcCl₂, with preferential charge transport directions predominantly through the metallic nucleus and aromatic ligand. As expected from the presence of the two chlorides coordinated to the metal in TiPcCl2, the orbital distribution differs significantly from the rest of the ClMPcs. In the HOMO plots for MnPcCl, InPcCl, and AlPcCl, orbital density is similarly distributed across the phthalocyanine ligand and the four condensed benzene rings. Significant differences emerge in the LUMO plots: MnPcCl shows uniform charge transport across the Mn atom, phthalocyanine ligand, and benzene rings; for InPcCl, benzene rings exhibit minimal density; and in AlPcCl, density is concentrated on the ligand. These findings indicate that the ClMPcs exhibit strong charge transport potential, making them promising candidates as organic semiconductors for optoelectronic devices, a prospect that requires experimental validation.

Fig. 3.

HOMO and LUMO contour plots on density isosurface at 0.04 e/Å3 for ClMPcs. Atoms are color-coded according to the Corey–Pauling–Koltun convention, with orbitals in red and blue for positive and negative phases respectively.

To evaluate the suitability as organic semiconductors and therefore, their behavior as a buffer layer, thin films of each ClMPc were deposited by high-vacuum sublimation. Topographic analysis was performed by AFM which produced the 3D surface images shown in Fig. 4. The difference in topography between each of the films is evident, considering the deposition under the same vacuum, temperature, and type of substrate conditions. This suggests that the molecular structure of each phthalocyanine influences film formation. The TiPcCl2 film is homogeneous without voids and surface imperfections, whereas the MnPcCl film displays valleys and small ridges. The AlPcCl film has prominent ridges giving it a heterogeneous appearance, with even greater heterogeneity exhibited by the InPcCl film. ClMPc molecules tend to arrange themselves by stacking aromatic rings. Attractive forces between aromatic rings such as π-π interactions and hydrogen bonds facilitate the obtaining of diverse types of structures, which depend largely on the substituents in the macrocycle, the orientation, and the dispersion of the molecules, relative to each other [33]. In these cases, structural differences are attributable to the presence of the metallic atom in the macrocycle, as well as the chloride ions coordinated to the metallic atom. On the other hand, studies of roughness and mechanical properties of Tensile Strength and Knoop Hardness were also carried out, with results presented in Table 2. The MnPcCl film presents the lowest Root Mean Square (RMS) and Roughness Average (Ra) followed by the TiPcCl2 film and then the AlPcCl and InPcCl films. These low roughnesses are expected to favor the transport of charges through these films, and their buffer layer behavior can be enhanced. Regarding the hardness, it is similar in all the films, and Tensile Strength (σ) is the largest for the InPcCl film, whereas for the rest of the films is essentially equivalent. These parameters indicate the adequate resistance and flexibility of the films, which is an advantage under service conditions when compared to the rigid silicon-based semiconductors currently used in the manufacture of devices such as LEDs.

Fig. 4.

3D AFM images for TiPcCl2, MnPcCl, InPcCl, and AlPcCl films.

Table 2.

RMS and Ra roughness, maximum Tensile Strength, and Knoop Hardness of ClMPc films.

| Film | RMS (nm) | Ra (nm) | σmax (Pa) | HK |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiPcCl2 | 8.352 | 6.68 | 1.8x10−4 | 15.02 |

| MnPcCl | 5.694 | 4.3 | 1.5x10−4 | 14.95 |

| InPcCl | 77.39 | 61.43 | 9.3x10−3 | 10.76 |

| AlPcCl | 14.38 | 8.83 | 1.5x10−4 | 15.19 |

In the IR spectra presented in Fig. 5a, the characteristic signals of MnPcCl can be seen both in the KBr pellet and in n-Si substrate thin films, with similar observations for the rest of the ClMPcs, summarized in Table 3. The slight changes in wavenumber among the ClMPcs correspond to differences in the cavity size of the phthalocyanine macrocycle [11], which depends on the central metal atom. Additionally, the spectra in Fig. 5a show a slight shift due to residual stresses generated during the deposition of the thin film. During high-vacuum sublimation, the ClMPcs undergo phase changes that generate internal stresses in the molecular structure, leading to minor IR signal shifts such as this. Nonetheless, vibrations due to asymmetric C–H stretching in the aromatic ring (3054–3059 cm⁻1), the aromatic C-C stretching vibration (∼1654 cm⁻1), and in-plane C–H bending (720-780 cm−1) [27,[34], [35], [36]] are preserved. The band between 3440 and 3480 cm−1 corresponds to the O-H stretching vibration, indicating that the sample absorbs atmospheric water [36]. Other observed vibrations include those at 1602 cm⁻1 for C=C stretching in isoindole units, 1461 cm⁻1 for C=N stretching in isoindole, and additional characteristic vibrations listed in sources [27,[32], [33], [34]] which can be seen in Table 3. On the other hand, there are two polymorphic forms of phthalocyanines due to the different π→π∗ electronic interactions between neighboring molecules with α-metastable and β-stable forms discernible by their C–H out-of-plane bending vibrations below 800 cm⁻1. The β-form has vibrations between 729 and 732 cm⁻1, while the α-form vibrates at ∼725 cm⁻1. According to the spectra in Fig. 5b, in all cases, polymorphic forms are preserved between pellets and thin films, with β-form for TiPcCl₂, MnPcCl, and AlPcCl, whereas InPcCl displays the α-form. This α-form and its stacking arrangement are responsible for the high roughness of the film, but also for its high tensile strength, compared to the rest of the ClMPcs.

Fig. 5.

(a) IR spectra and (b) IR spectrum region between 700 and 770 cm−1 for MnPcCl in pellet and thin film.

Table 3.

IR spectrum signals for ClMPcs in KBr pellet and film on n-type Si.

| Sample | C-H | C-C | OH | C=C | C=N | C-N | α-form | β-form |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiPcCl2 KBr pellet | 3055, 1424, 1121, 907, 780-720 | 1647, 1330, 1162 | 3428 | 1610 | 1465 | 1288, 1069 | – | 732 |

| TiPcCl2 film | 3053, 1423, 1121, 907, 789-700 | 1647, 1335, 1167 | 3465 | 1610 | 1470 | 1288, 1069 | – | 730 |

| MnPcCl KBr pellet |

3054, 1418, 1118, 907, 789-700 | 1647, 1336, 1168 | 3480–3440 | 1606 | 1461 | 1287, 1076 | – | 729 |

| MnPcCl film | 3059, 1422, 1118, 907, 780-720 | 1658, 1336, 1168 | 348 | 1602 | 1461 | 1287, 1061 | – | 727 |

| InPcCl KBr pellet | 3049, 1421, 1113, 896, 782-710 | 1651, 1334, 1161 | – | 1606 | 1466 | 1285, 1060 | 725 | – |

| InPcCl film | 3049, 1421, 1113, 887, 790-700 | 1651, 1338, 1160 | – | 1607 | 1466 | 1280, 1062 | 722 | – |

| AlPcCl KBr pellet | 3053, 1422, 1118, 901, 782-702 | 1651, 1333, 1166 | 3441 | 1604 | 1466 | 1289, 1062 | – | 728 |

| AlPcCl film | 3049, 1426, 1118, 901, 777-711 | 1647, 1343, 1166 | – | 1612 | 1466 | 1286, 1062 | – | 731 |

To study the performance of ClMPcs as semiconductor thin films, diffused reflectance (R) studies were performed as presented in Fig. 6a. The R spectra of ClMPcs are a result of their conjugated π-electron systems, the overlapping orbitals of the central metal, their axial chloride substituents, and the effects of film molecular packing [12]. In Fig. 6a, all the spectra exhibit similar behavior, with two prominent bands between 210–450 nm and 650–780 nm, the latter showing the highest R of ∼46 %. The band in the UV region is referred to as the B band while the band in the visible region is the Q band [12]. The B band has three peaks, R spectra differences between ClMPcs are likely due to orbital overlapping between the phthalocyanine rings and their central metal atom. The low energy high-intensity peak of the B band region observed in ClMPcs suggests d-band association with the central metal, leading to π-d transitions due to the partially filled d-orbitals of the metal in the ClMPcs. Changes in the higher energy region of the B band may be a result of d-π∗ transitions [12]. In contrast, the Q band region displays a single peak, interpreted as a π-π∗ excitation between bonding and anti-bonding molecular orbitals [12]. Notably a very low R is also observed for the MnPcCl film, with a maximum R of 20 % at λ = 215 nm. For other ClMPcs, the highest R is seen at λ > 600 nm, with InPcCl and AlPcCl films reaching R values around 38 %, while the TiPcCl2 film exhibits the highest R at 46 %. These results indicate that the MnPcCl film, which also has the lowest roughness, is likely to have minimum reflection losses. This correlates with its lower theoretical band gap (see Table 1), suggesting that the MnPcCl film enables optimal electronic transitions between HOMO and LUMO orbitals.

Fig. 6.

(a) Diffuse Reflectance spectra, (b) Kubelka-Munk plot and (c) Fluorescence intensity of ClMPc films.

To determine the solid-state band gap energy, the Kubelka-Munk function F(KM) was used [37]. This function was obtained from the R spectrum, and the value of the band gap can be estimated from the Tauc equation (2) as follows [38,39]:

| (2) |

where α is the absorption coefficient, h is the Planck constant, ν is the frequency ν = 1/λ, Eg is the forbidden energy band, A is a proportionality constant, and the exponent n depends on the band structure of the semiconductor. The exponent n = 2 for indirect allowed optical transition is used, due to the amorphous nature of the films generated by the high-vacuum sublimation [37,40]. This procedure causes the films to have an amorphous structure and for amorphous systems, the density of states inside the band gap is non-zero, with disorder-induced band tails. Therefore, the band gap width is not well defined. Band tail states are electronic states present just above the valence band or right below the conduction band. In general, these states originate from structural, impurity, and/or compositional disorder [41]. Based on the above, the coefficient α is directly proportional to F(KM), and the Tauc's relation can be rewritten in terms of the Kubelka-Munk function, according to equation (3) [40]:

| (3) |

The Eg of ClMPcs can be detected via extrapolating the straight-line parts of the curves of (hνF(KM))1/2 vs. photon energy (hν) plots as shown in Fig. 6b and recorded in Table 4. According to the optical gap previously obtained in solution and for DFT method (see Table 1), the results show the lowest band gap for MnPcCl. Mn has a greater capacity to interact with the π orbitals of the phthalocyanine ligand, due to its electronic configuration, which can further stabilize the LUMO or destabilize the HOMO, decreasing the band gap. When compared to the band gaps reported in the literature, for the MnPcCl thin film it is observed that the band gap is in the same order of magnitude as previously reported [15,42], for TiPcCl2 band gap, also within previously reported values [43], as well as AlPcCl [13,34] and as InPcCl [44]. Also worth mentioning is the fact that Kubelka-Munk function obtained band gaps are of the same order of magnitude as optical band gaps obtained in solution and by DFT calculation; both within values that organic semiconductors exhibit.

Table 4.

Onset gap, Kubelka-Munk gap, Stokes shift of ClMPc films.

| Film | EKubelka-Munk (eV) | Stokes shift ΔStokes (nm) |

|---|---|---|

| TiPcCl2 | 1.94 | 75 |

| MnPcCl | 1.67 | 71 |

| InPcCl | 2.00 | 71 |

| AlPcCl | 1.98 | 77 |

ClMPcs films are photoactive, contrary to chloride-free metallophthalocyanines that do not fluoresce in the solid state due to delocalized excitons leading to enhanced non-radiative deactivation [45]. Emission spectra in Fig. 6c and Stokes shifts (ΔStokes) registered in Table 4 were obtained for ClMPc films at 364 nm excitation. The spectra exhibit a bathochromic shift between them due to the metallic nucleus and its coordination in the phthalocyanine structure. Nevertheless, all maximum emissions are found at a close range of wavelengths: 435 nm for MnPcCl, 441 nm for AlPcCl, and 439 nm for both TiPcCl2 and InPcCl, which all correspond to blue light wavelengths. The maximum emission values are congruent with those obtained by Lin Pan et al. [46], in their studies on films of different phthalocyanine derivatives. The maximum emission intensity is exhibited by InPcCl, followed by TiPcCl2, then AlPcCl, and finally MnPcCl. It is necessary to note that even if MnPcCl shows the highest charge transport capacity compared to the rest of the ClMPcs, due to its low band gap, its fluorescent behavior is lower. The type of metallic atom, its oxidation state, and its coordination play a significant role in the location and intensity of the fluorescent emission peak. Based on these results, it was conjectured that ClMPcs films could find potential applications in optoelectronic devices such as OLEDs. However, these results must be complemented by the study of the electrical behavior of the ClMPc films.

To study the electrical behavior of ClMPc films, simple devices with glass-FTO/ClMPc/Ag architecture were fabricated. In these devices, the phthalocyanine film is placed between the electrodes, with the FTO anode being transparent, to allow the light to traverse. Holes are injected through the anode and electrons are injected through the Ag cathode, reaching the ClMPc emissive film where the recombination of both types of charge carriers will occur. Fig. 7 shows the current-voltage (I-V) relationship graphs for the four devices in forward and reverse bias directions at room temperature, and under different lighting conditions. Each device has a distinct behavior. The device integrated by the TiPcCl2 film presents ambipolarity with a direct relationship between the voltage and the transported current, not affected by the changes in the illumination experienced by the device, except for UV. On the other hand, on the MnPcCl device, there exists current leakage in reverse bias. The barrier at the interface restricts forward and reverse carriers from flowing across the junction, where the built-in potential could be developed [45]. Furthermore, the charge transport on this device is not influenced by lighting conditions. The InPcCl film device shows a vastly different behavior than the other devices. The asymmetrical I-V characteristics exhibit rectifying behavior that verifies the formation of a non-ohmic junction [46]. In forward bias, an exponential behavior of I-V curves is observed with a slight effect of the lighting conditions, especially under white and blue lighting. Finally, in the AlPcCl film device, a small effect of the lighting conditions is also observed, especially under UV lighting. In addition, this and the TiPcCl2 film devices generate the highest transported current, and their behavior in both forward and reverse bias directions at room temperature is fundamentally ohmic. Regarding the maximum transported current, the TiPcCl2 device presents I maximum of 3x10−3 A, within the range previously reported for the PET/ITO/TiPcCl2/Ag device [43], 7x10−5 A for the InPcCl device, within the range obtained by Zeyada et al. [14], whereas maximum for AlPcCl is of 1.7x10−3 A, similar to that obtained by Soliman et al. [47], and finally 1.5x10−5 A for the MnPcCl device, two orders of magnitude higher than reported by Madhuri et al. [48] for iodine-doped MnPc. It is important to consider that the higher value of electric current recorded in TiPcCl2, may be indicative of a more efficient charge injection, because of a higher contact ohmicity. This effect would be related to the lower injection barrier between the film of the ClMPc and the anode (φ). The values of φ, estimated as the difference between the work function of the anode (Φ = 4.7 eV) and the HOMO energy of the material, are presented in Table 5. According to this, the trend observed in the injection barriers is φ (MnPcCl) < φ (AlPcCl) < φ (InPcCl) < φ (TiPcCl2). However, comparing these values to the magnitude of the maximum current transported, it seems evident that this is not the only aspect to consider as a condition in the total amount of current flow through the device. The structural differences between ClMPcs are a decisive factor that induces different morphological, optical, fluorescent, and electrical properties of the film. Although the band gaps of TiPcCl2 and AlPcCl films are not the smallest, in terms of electrical behavior their devices present the best electrical characteristics both for their ambipolarity and their maximum I values, due to their electronic and structural properties that affect the charge carrier mobility. These phthalocyanines have a more favorable structure for electronic delocalization, compared to MnPcCl and InPcCl.

Fig. 7.

I-V Characteristics of glass/FTO/ClMPc/Ag at different illumination conditions in both forward and reverse bias directions.

Table 5.

Injection Barrier (φ), Power (P) and Electrical Conductivity (σ) of ClMPc devices.

| Film | Φcalc (eV) | P (mW) | σ (Scm) at 50 °C | σ (Scm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiPcCl2 | 0.6906 | 2.78 | 8.08x10−3 | 2.6x10−2 at 60 °C |

| MnPcCl | 0.5257 | 1.11 | 6.6x10−2 | 6.6x10−2 at 50 °C |

| InPcCl | 0.6117 | 0.0021 | 6.3x10−5 | 6.3x10−5 at 25 °C |

| AlPcCl | 0.5899 | 2.33 | 5.6x10−3 | 1.5x10−2 at 80 °C |

The power (P) was evaluated under white illumination conditions for each of the four devices. Each behavior with voltage can be observed in Fig. 8 and the maximum power at 1.1 V is presented in Table 5. The curve in the TiPcCl2 film device film shows exponential behavior up to a voltage of 1.08 V from which, the power increases up to 2.7x10−3 W without the voltage changing. Regarding the curve of the MnPcCl device, a completely exponential behavior between the P-V is observed. In the device with the InPcCl film, the behavior, although exponential, suffers continuous interference, probably owing to the nearly insulating behavior in the forward direction (see Fig. 7), and as expected, the P in this device is the lowest compared to the rest of the devices. Finally, the AlPcCl film device also exhibits exponential behavior, with a slight saturation at 0.93 V that is eliminated by increasing the voltage which reaches a maximum. According to the results recorded in Table 5, the highest P is presented in the following order: TiPcCl2>AlPcCl > MnPcCl > InPcCl. These results are consistent with those obtained in the I-V behavior and are complemented by the results of the electrical conductivity (σ) at 1 V. Except for the InPcCl device, the rest of the devices present their maximum current at different temperatures, the TiPcCl2 device at 60 °C, the MnPcCl device at 50 °C, and the AlPcCl device at 80 °C. At a selected 50 °C control temperature, the highest current occurs according to the following order: MnPcCl > TiPcCl2>AlPcCl > InPcCl, as recorded in Table 5. It is important to consider that although at room temperature, the maximum I is higher for the TiPcCl2 and AlPcCl devices, as the temperature increases, the highest conductivity is presented in the MnPcCl film device. This can be attributed to its lower band gap, which allows the charges to jump with more ease from the HOMO up to the LUMO when heated. On the other hand, considering that all the devices were manufactured under the same methodology and evaluated under the same conditions, it is evident that the specific type of phthalocyanine and specifically, the particular metallic atom and coordination in the macrocycle center, are responsible for their electrical behavior. Finally, it is important to consider that the overall electrical conductivity of the ClMPc films may be affected by defects in the FTO anode layer, such as oxygen vacancies and the fluor-oxide interactions. Nevertheless, this effect is mainly dependent on the fluor concentration in FTO [49,50], which is not a variable in the experimental conditions of the present study. The present work discloses a comparative study between the behavior of different ClMPcs, prepared and evaluated under the same experimental conditions. Additionally, none of the thermal processes carried out (200 °C for deposition and up to 100 °C for electrical characterization) are of sufficient significance to affect the crystalline structure of the FTO and promote the generation of vacancies. Nor is such an effect induced by the interaction with the ClMPcs, owing to the presence of coordinated chlorides, which confer high thermal and chemical stability. In spite of this, it would be worthwhile to study the effects of different types of anode layers in future works.

Fig. 8.

Power Characteristics of glass/FTO/ClMPc/Al at white illumination condition in the forward direction.

To complement the characterization of the ClMPc devices, measurements of the external quantum efficiency (EQE) were performed. The EQE refers to the number of photons emitted by the device, concerning the number of injected charges. The EQE measured from 375 to 1150 nm exhibited an average maximum value of 0.55 % for TiPcCl2, 0.47 % for MnPcCl, and 0.57 % for InPcCl and AlPcCl. In spite of the differences between each of the four devices, the EQE values are in the same order of magnitude. However, they are far below the 3 % obtained for other MPcs [51]. The short circuit density (JSC) was also evaluated, which represents the maximum density of current flow through an optoelectronic device when the voltage across it is zero. JSC provides information on the ability of the glass/FTO/ClMPc/Ag devices, to capture and use the AM1.5 spectrum. The obtained values are between 3.3x10−3 and 4x10−3 mA/cm2 and vary depending on the ClMPc present in the device. When comparing this parameter with that reported for other phthalocyanines [51], an agreement is observed in the order of magnitude. While the EQE and JSC are still low, they can be increased in future works, by the addition of interfacial layers between the ClMPc film and the electrodes.

5. Conclusions

Chlorinated phthalocyanines TiPcCl2, MnPcCl, InPcCl, and AlPcCl were studied in their semiconductor and buffer layer role for applications in organic optoelectronics. Initially, these metallophthalocyanines were analyzed in solution by UV–visible spectroscopy and subsequently, they were later deposited as films. AlPcCl has low optical properties in solution, however, the absorbance spectra of TiPcCl2, MnPcCl and InPcCl present the Q and B bands assigned to the different π-π∗ transitions, and an optical band gap between 1.74 and 2.20 eV. This band gap is in the same order of magnitude as that obtained in thin films, using the Kubelka-Munk function and theoretically, calculated by DFT. Films deposited by high-vacuum sublimation are homogeneous with very low roughness for TiPcCl2, MnPcCl, and AlPcCl. All ClMPc films have properties that allow them to be used as organic semiconductors, such as their solid-state band gaps between 2.12 and 3.61 eV, maximum current transported of 3x10−3 A, or electrical conductivity of 6.6 x 10−2 S/cm. The trend observed in the injection barriers is MnPcCl < AlPcCl < InPcCl < TiPcCl2, where the latter film exhibited the greatest load carrying capacity. The mechanical, optical, and fluorescent properties in the ClMPc films depend on the metal atom housed in the phthalocyanine ring cavity, which is a decisive factor in the semiconductor behavior and, therefore, the behavior of the ClMPcs as a buffer layer.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

María Elena Sánchez Vergara: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Mariana Gonzalez Vargas: Writing – original draft, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Emilio I. Sandoval Plata: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Alejandro Flores Huerta: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Investigation, Conceptualization.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request. For requesting data, please write to the corresponding author.

Funding

María Elena Sánchez Vergara acknowledges the financial support from the Anahuac México University, project number PI0000068.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the technical support of Professor Miguel Angel Sierra.

References

- 1.Huang Y., Hsiang E.-L., Deng M.-Y., Wu S.-T. Mini-LED, Micro-LED and OLED displays: present status and future perspectives. Light Sci. Appl. 2020;9:1–2. doi: 10.1038/s41377-020-0341-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hong Q. The working principle, application and comparative analysis of OLED and OPV. HSET. 2022;23:34–35. doi: 10.54097/hset.v23i.3124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Younas R., Younas A. Structural analysis of enhanced performance organic light emitting Diodes (OLEDs) Int. J. Netw. Commun. Secur. 2020;8:80–81. E-ISSN 2308-9830. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avici A.N., Akbay S. A review based on OLED lighting conditions and human circadian system. Color Cult. Sci. J. 2023;15:8. doi: 10.23738/CCSJ.150101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar A., Meunier-Prest R., Bouvet M. Organic heterojunction devices based on phthalocyanines: a new approach to gas chemosensing. Sensors. 2020;20:1–3. doi: 10.3390/s20174700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tadayyon S.M., Grandin H.M., Griffiths K., Norton P.R., Aziz H., Popovic Z.D. CuPc buffer layer role in OLED performance: a study of the interfacial band energies. Org. Electron. 2004;5:157–166. doi: 10.1016/j.orgel.2003.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hwanga H.U., Yanga S., Kim J.W. Interface charge transfer between metal phthalocyanine and fluorinated hexaazatrinaphthylene molecules. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2020;20:841. doi: 10.1016/j.cap.2020.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anuar A., Roslan N.A., Abdullah S.M., Bawazeer T.M., Alsoufi M.S., Alsenany N., Supangat A. Improving the photo-current of poly(3-hexylthiophene): [6,6]-phenyl C71 T butyric acid methyl-ester photodetector by incorporating the small molecules. Thin Solid Films. 2020;703:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.tsf.2020.137976. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sukhikh A., Klyamer D., Bonegardt D., Basaova T.V. Octafluoro-substituted phthalocyanines of zinc, cobalt, and vanadyl: single crystal structure, spectral study and oriented thin films. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023;24:1–2. doi: 10.3390/ijms24032034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sekhar K.C., Kiran M.R., Ulla H., Urs R.G., Shekar G.L. Exploring the temperature-dependent hole-transport in vanadyl-phthalocyanine thin films. Physica B. 2021;608:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.physb.2021.412895. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alosabi A.Q., Al-Muntaser A.A., El-Nahass M.M., Oraby A.H. Electrical conduction mechanism and dielectric relaxation of bulk disodium phthalocyanine. Phys. Scripta. 2022;97:1–2. doi: 10.1088/1402-4896/ac5ff8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cranston R.R., Lessard B.H. Metal phthalocyanines: thin- film formation, microstructure, and physical properties. RSC Adv. 2021;11:21716–21717. doi: 10.1039/D1RA03853B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azim-Araghi M.E., Krier A. Optical characterization of chloroaluminium phthalocyanine (ClAlPc) thin films. Pure Appl Opt. 1997;6:443–453. doi: 10.1088/0963-9659/6/4/007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeyada H.M., El-Nahass M.M., El-Menyawy E.M., El-Sawah A.S. Electrical and photovoltaic characteristics of indium phthalocyanine chloride/p-Si solar cell. Synth. Met. 2015:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.synthmet.2015.06.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El-Zaidia E.F.M. Studies structure, surface morphology, linear and nonlinear optical properties of nanocrystalline thin films of manganese (III) phthalocyanine chloride for photodetectors application. Sensor. Actuator. 2021;330 doi: 10.1016/j.sna.2021.112828. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klyamer D.D., Basova T.V. Effect of the structural features of metal phthalocyanine films on their electrophysical properties. J. Struct. Chem. 2022;63:997–998. doi: 10.1134/S0022476622070010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abdelhamid S.M., Dongol M., Elhady A.F., Abuelwafa A.A. Impact of transparent conducting substrates on structural and optical of Titanium(IV) phthalocyanine dichloride (TiPcCl2) thin flms. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2023;6:1–2. doi: 10.1007/s42452-024-05638-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Darwish A.A.A., Helali S., Qashou S.I., Yahia I.S., El-Zaidia E.F.M. Studying the surface morphology, linear and nonlinear optical properties of manganese (III) phthalocyanine chloride/FTO films. Physica B. 2021;622:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.physb.2021.413355. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alghamdi S.A., Darwish A.A.A., Yahia I.S., El-Zaidia E.F.M. Structural characterization and optical properties of nanostructured indium (III) phthalocyanine chloride/FTO thin films for photoelectric applications. Optik. 2021;239:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.ijleo.2021.166780. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simões M.M., Paiva K.L., de Souza I.F., Mello V.C., Martins da Silva I.G., Souza P.E.N., Muehlmann L.A., Báo S.N. The potential of photodynamic therapy using solid lipid nanoparticles with aluminum phthalocyanine chloride as a nanocarrier for modulating immunogenic cell death in murine melanoma in vitro. Pharmaceutics. 2024;16:1–2. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics16070941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sánchez-Vergara M.E., Rivera M. Investigation of optical properties of annealed aluminum phthalocyanine derivatives thin films. J. Phys. Chem. Solid. 2014;75:599–605. doi: 10.1016/j.jpcs.2014.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao Y., Truhlar D.G. A new local density functional for main-group thermochemistry, transition metal bonding, thermochemical kinetics, and noncovalent interactions. J. Chem. Phys. 2006;125 doi: 10.1063/1.2370993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raju R.K., Bengali A.A., Brothers E.N. A unified set of experimental organometallic data used to evaluate modern theoretical methods. Dalton Trans. 2016;45:13766–13778. doi: 10.1039/C6DT02763F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grimme S., Antony J., Ehrlich S., Krieg H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010;132 doi: 10.1063/1.3382344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hättig C., Schmitz G., Koßmann J. Auxiliary basis sets for density-fitted correlated wavefunction calculations: weighted core-valence and ECP basis sets for post-d elements. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012;14:6549–6555. doi: 10.1039/C2CP40400A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gottfried J. Surface chemistry of porphyrins and phthalocyanines. Surf. Sci. Rep. 2015;70:259–379. doi: 10.1016/j.surfrep.2015.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Basova T., Kiselev V., Plyashkevich V., Cheblakov P., Latteyer F., Peisert H., Chassè T. Orientation and morphology of chloroaluminum phthalocyanine films grown by vapor deposition: electrical field-induced molecular alignment. Chem. Phys. 2011;380:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphys.2010.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Basova T., Kiselev V., Klyamer D.D., Hassan A. Thin films of chlorosubstituted vanadyl phthalocyanine: charge transport properties and optical spectroscopy study of structure. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 2018;29:16791–16798. doi: 10.1007/s10854-018-9773-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu k., Wang Y., Yao J., Luo Y. Origin of the Q-band splitting in the absorption spectra of aluminum phthalocyanine chloride. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2007;438:36–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cplett.2007.02.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kobayashi N., Muranaka A., Ishii K. Symmetry-lowering of the phthalocyanine chromophore by a C2 type axial ligand. Inorg. Chem. 2000;39:2256–2257. doi: 10.1021/ic9914950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hongbing Z., Wenzhe C., Guanghui L., Minquan W. Dimerization of metallophthalocyanines in inorganic matrix. Mater. Sci. Eng. B. 2003;100:113–118. doi: 10.1016/S0921-5107(03)00083-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jayme C.C., Calori I.R., Tedesco A.C. Spectroscopic analysis of aluminum chloride phthalocyanine in binary water/ethanol systems for the design of a new drug delivery system for photodynamic therapy cancer treatment. Spectrochim. Acta Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2016;153:178–183. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2015.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gregory P. Industrial applications of phthalocyanines. J.Porphyrins Phthalocyanines. 2000;4:432–437. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1409(200006/07)4:4<432::AID-JPP254>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.El-Nahass M.M., Soliman H.S., Khalifa B.A., Soliman I.M. Structural and optical properties of nanocrystalline aluminum phthalocyanine chloride thin films. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2015;38:177–183. doi: 10.1016/j.mssp.2015.04.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahmad A., Collins R.A. FTIR characterization of triclinic phthalocyanine. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 1991;24:1894–1897. doi: 10.1088/0022-3727/24/10/029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soliman I.M., El-Nahass M.M., Eid K.M., Ammar H.Y. Vibrational spectroscopic analysis of aluminum phthalocyanine chloride. experimental and DFT study. Physica B. 2016;491:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.physb.2016.03.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Landi Jr S., Segundo I.R., Freitas E., Vasilevskiy M., Carneiro J., Tavares C.J. Use and misuse of the Kubelka-Munk function to obtain the band gap energy from diffuse reflectance measurements. Solid State Commun. 2022;341:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ssc.2021.114573. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tauc J. Optical properties and electronic structure of amorphous Ge and Si. Mater. Res. Bull. 1968;3:37–46. doi: 10.1016/0025-5408(68)90023-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tauc J., Menth A. States in the gap. J. Non-Cryst. Solids. 1972;8:569–585. doi: 10.1016/0022-3093(72)90194-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sharmoukh W., Hameed T.A., Yakouta S.M. New nonmagnetic aliovalent dopants (Li+, Cu2+, In3+ and Ti4+): optical and strong intrinsic room temperature ferromagnetism of perovskite BaSnO3. J. Alloys Compd. 2022;925 doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2022.166702. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wager J.F. Real- and reciprocal-space attributes of band tail states. AIP Adv. 2017;7:1–10. doi: 10.1063/1.5008521. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.El-Zaidia E.F.M., Darwish A.A.A., Elroby S.A., Hassanien A.M. Gamma irradiation effect on the structural and optical properties of manganese (III) phthalocyanine chloride films: experimental and theoretical approach for optoelectronics applications. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. B. 2024;557 doi: 10.1016/j.nimb.2024.165556. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sánchez Vergara M.E., Villanueva Heredia L.F., Hamui L. Influence of the coordinated ligand on the optical and electrical properties in titanium phthalocyanine-based active films for photovoltaics. Materials. 2023;16:551. doi: 10.3390/ma16020551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.El-Zaidia E.F.M., Qashou S.I., Yahia I.S., Abdel-Galil A., Darwish A.A.A. Impact of gamma irradiation on optical and nonlinear properties of Indium chloride phthalocyanine thin films. Phys. Scripta. 2024;99 doi: 10.1088/1402-4896/ad8113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cornil J., Beljonne D., Calbert J.P., Brédas J.L. Interchain interactions in organic p-conjugated materials: impact on electronic structure, optical response, and charge transport. Adv. Mater. 2001;13:1053–1067. doi: 10.1002/1521-4095(200107)13:14<1053::AID-ADMA1053>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pan L., Jia K., Shou H., Zhou X., Wang P., Liu X. Unification of molecular NIR fluorescence and aggregation-induced blue emission via novel dendritic zinc phthalocyanines. J. Mater. Sci. 2017;52:3402–3418. doi: 10.1007/s10853-016-0628-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Soliman I.M., El-Nahass M.M., Khalifa B.A. Characterization and photovoltaic performance of organic device based on AlPcCl/p-Si heterojunction. Synth. Met. 2015;209:55–59. doi: 10.1016/j.synthmet.2015.06.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Madhuri K.P., John N.S., Angappane S., Santra P.K., Bertram F. Influence of iodine doping on the structure, morphology, and physical properties of manganese phthalocyanine thin films. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2018;122:28075–28084. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.8b08205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang X., Di Q., Wang X., Zhao H., Liang B., Yang J. Effect of oxygen vacancies on photoluminescence and electrical properties of (2 0 0) oriented fluorine-doped SnO2 films. Mater. Sci. Eng. B. 2019;250 doi: 10.1016/j.mseb.2019.114433. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang B., Tian Y., Zhang J.X., Cai W. The role of oxygen vacancy in fluorine-doped SnO2 films. Phys. B Condens. Matter. 2011;406:1822–1826. doi: 10.1016/j.physb.2011.02.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Islam Z.U.I., Tahir M., Syed W.A., Aziz F., Wahab F., Said S.M., Sarker M.R., Md Ali S.H., Mohd Sabri M.F. Fabrication and photovoltaic properties of organic solar cell based on zinc phthalocyanine. Energies. 2020;13:962. doi: 10.3390/en13040962. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request. For requesting data, please write to the corresponding author.