Abstract

Background

Chronic liver disease is an on-going loss of liver structure and functions that lasts for at least six months. About 1.5 billion population suffered with this devastating disease worldwide.

Objectives

The aim of this study is to assess the treatment outcome and associated factors in patients with chronic liver disease at Bahir Dar, North West Ethiopia.

Method

A retrospective cross sectional study was conducted in both governmental and private hospitals of Bahir Dar city from January to August 2024. All patients with liver disease for at least six months and treated for their specific causes and/or complications were included. Descriptive statistics was employed to explain socio-demographic and relevant clinical characteristics. Binary logistic regression was employed to determine associated factors with poor treatment outcome. Texts, tables and charts used to present statistically and/or clinically significant results. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Result

A total of 213 medical records of chronic liver disease patients were reviewed. Most of the study participants (72.8%) were male and resided in rural area (63.8%). Viral hepatitis was the most frequent (60.0%) etiology followed by parasitic (23.0%) and alcohol misuse (11.5%). The percentage of patients with chronic liver disease who experienced poor treatment outcomes was 39.0% and 54.2% were not taking medications specifically tailored to their condition. Stages of chronic liver disease (AOR = 2.68; 95%CI: 1.50–4.76, p = 0.001), carcinoma status (AOR = 2.68; 95%CI: 1.07–6.68, p = 0.035) and treatment duration (AOR = 0.38; 95%CI: 0.15–0.98, p = 0.045) were independent predictors for poor treatment outcome.

Conclusion

The overall treatment outcome of chronic liver disease in our study was inadequate. Decompensated stages of cirrhosis, cellular carcinoma and shorter treatment duration were significant factors of treatment failure. Timely initiation of appropriate therapy is warranted to improve the treatment outcome of chronic liver disease patients.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12876-025-03719-z.

Keywords: Chronic liver disease, Predictor, Treatment outcome

Introduction

Background

Chronic liver disease (CLD) is a progressive decline of liver functions, such as synthesis of blood proteins, detoxification of harmful metabolic waste and excretion of bile for at least six months [1, 2]. It is the eleventh leading cause of death worldwide accounts for two million deaths annually and is responsible for 4% of all deaths [3]. Portal hypertension, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma are the three significant complications of CLD that lead to death [1, 2].

Cirrhosis is a permanent scar that develops after a long period of inflammation which results in the replacement of the healthy liver parenchyma with fibrotic tissue and regenerative nodules [4]. It may lead to portal hypertension, hepatic encephalopathy, jaundice, ascites and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, hyperestrinism, hepatatorenal and hepatopulmonary syndrome and coagulopathy [1, 3, 4].

Similarly, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fourth-leading cause of cancer related death after lung, breast and colorectal cancer, but the second-leading cause of cancer-related death in men [3]. About 1.45 million people in the world had liver cancer from which 0.66, 0.37, 0.26, 0.1 and 0.12 million caused by hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), alcohol misuse, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and other causes respectively [5].

The most common causative agents for CLD comprises prolonged alcohol abuse, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), toxins including drugs (methotrexate, amiodarone), viral infections (hepatitis B, hepatitis C), autoimmune diseases, genetic and metabolic disorders [1, 3, 4]. NAFLD, which is characterized by the intracellular deposition of lipids in hepatocytes, associated with obesity, diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension and insulin resistance, and chronic alcohol use are the leading causes of cirrhosis globally [3, 6, 7, 8].

It is crucial to identify the etiologic agent and the severity of the disease before making a treatment decision. It can be asymptomatic and neglected until decompensation occurs, unless timely screening with comprehensive history, viral markers, metabolism and liver panels, antibody tests, imaging and biopsy is performing [9].

Treatment of CLD requires a multidisciplinary approach and targeted to address the symptoms, halt the progression of the disease and complications [1]. Most pharmacological therapies target to treat the direct causes of CLD but not pause progression and reverse cirrhosis. Liver transplantation remains the only curative option for a selected group of patients with decompensated cirrhosis [4].

Complete abstinence from alcohol, combined with a high-calorie diet, multivitamins, thiamine, and folic acid supplementation, is the cornerstone of therapy for chronic alcoholic liver disease (ALD). Although treatment with prednisolone 40 mg daily, improve 28‐day mortality rate, it had no effect on long‐term outcomes [2, 10]. Lifestyle modification and control of metabolic syndrome risk factors; involving diet, exercise, and weight loss has been encouraged to treat patients with NAFLD [2, 11].

Conventional and pegylated interferon (PEG-INF), lamivudine, adefovir, entecavir, telbivudine and Tenofovir have been approved for the treatment of chronic HBV induced CLD [12]. Tenofovir 300 mg oral once daily for patients with a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of at least 60 ml/min or Entecavir 0.5 mg oral, once daily are the first line antivirals for HBV. Entecavir is preferred over Tenofovir in patients age > 60 years old, chronic kidney disease, osteoporosis or steroid use [2, 13].

Nowadays, most patients with persistent HCV infection appear to be cured by direct acting antivirals (DAA) [9]. A simple, pangenotypic DAA should be given to any patient with HCV infection who is willing to receive treatment. For 12 weeks, the recommended regimen consists of one pill once day containing 400 mg of Sofosbuvir and 100 mg of Velpatasvir [13].

First-line therapies for cirrhosis sequelae include carvedilol or propranolol to prevent variceal bleeding, lactulose for hepatic encephalopathy, combination aldosterone antagonists and loop diuretics for ascites, and terlipressin for hepatorenal syndrome [5, 14].

While liver transplantation is the preferred course of treatment for patients with early-stage HCC in the presence of decompensated cirrhosis, surgical resection is strongly advised for localized HCC with or without compensated cirrhosis [13].

About 1.75 million hospital admissions and deaths were caused by chronic liver disease, a neglected illness that significantly impacted Ethiopia’s health and economy [20]. Merely 28% of the study population was released with improved outcomes from St. Paul’s Hospital Millennium Medical College, and no one received antiviral therapy or any other type of targeted treatment [21].

Inadequate awareness on vaccination, prompt screening and treatment commencement; inadequate treatment adherence, socioeconomic instability, shortage and cost of cause specific drugs may result in patient attrition, diminished success of each therapy technique and overall results.

Certain countries have carried out studies on the treatment result of CLD and its predictors [15, 16, 17, 18, 19]. Data on the effectiveness of treatment and independent variables associated with CLD are, however, scarce in Ethiopia. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of CLD treatment and risk factors among patients receiving care in the Amhara Region in Northwest Ethiopia.

Methods and materials

Study area, period, design, and population

The study was conducted in all hospitals at Bahir Dar City, Amhara region of Ethiopia, between January 1 and August 30, 2024. Bahir Dar City situated 552 km northwest of Addis Ababa, and it is one of Ethiopia’s tourist destinations. 455,901 people call Bahir Dar City home, according to the Ethiopian Statistics Service data from 2022. The hospitals that serve this population are four private (Adinas General Hospital, Afilas General Hospital, GAMBY Teaching General Hospital, and Dream Care General Hospital) and three governmental (Tibebe Gion Teaching and Specialized Hospital, Felege Hiwot Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, and Addis Alem General Hospital).

A retrospective facility-based cross-sectional study was carried out to gather clinical and demographic information from the medical records of CLD patients who underwent follow-up care at all of Bahir Dar city’s hospitals. Patients who had liver illness for at least six months and were receiving therapy for its consequences or particular causes during the study period made up the research populations.

Sample size determination and techniques

All CLD patients treated in all hospitals at Bahir Dar city during the study period were considered. Patients with incomplete information about treatment and lost to follow up were excluded.

Operational definitions

Alcoholic liver disease

Clinical and radiological signs of CLD plus daily alcohol consumption of > 20 g in women and > 30 g in men, for a minimum period of 6 months.

Chronic HBV

Evidence of CLD on liver ultrasound and positive serum hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg).

Chronic HCV

Evidence of CLD on liver ultrasound and positive serum anti-HCV and positive HCV ribonucleic acid (RNA).

Chronic liver disease

a progressive destruction of liver tissue with subsequent necrosis that persists for at least 6 months. It is declared using the combination of clinical features suggestive of CLD and either ultrasound findings (presence of an irregular liver surface) or serological tests (The serum aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index (APRI) using a threshold of 0.7 as an indicator of significant fibrosis.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

Liver ultrasound findings of steatosis and absence of significant alcohol consumption or other recognised secondary causes of steatosis plus BMI > 25 kg/m2.

Data collection procedures and instrument

Important characteristics were incorporated into a structured questionnaire by going over prior research [20, 21, 22], treatment charts, follow-up forms, patient registrations, and lab requests. Each CLD patient’s treatment card was located and examined after obtaining their medical registration number from the registration book in order to gather clinical, laboratory, and demographic information.

The MSc pharmacist was tasked with overseeing all activities, while four of the BSC pharmacists were designated as data collectors. Using a structured questionnaire, all of the data collectors and the coordinator exchanged ideas on how to collect data from patient charts. Data collectors were able to extract clinical and sociodemographic information on CLD patients from their patient charts. Every day, the coordinator verified that the data was complete and oversaw the entire process of gathering data.

Prior to the actual data collection period, 15 CLD patients at Debre Tabor Referral Hospital were tested using the data abstraction format. All data that was missing, erroneous, unnecessary, improperly formatted, or duplicated was promptly fixed. The data were meticulously cleaned up prior to the primary analysis.

Data processing and analysis

IBM SPSS v26 2019 was used to record and analyse the gathered data. The mean, median, and standard deviations were used in the analysis of descriptive statistics for continuous data. While frequency and percentage were employed to summarize categorical variables, the chi-square test was used to ascertain the association. Results that were statistically or clinically significant were presented using tables and charts. The variables in the bivariate analysis with p-value ≤ 0.2 were subsequently analysed in multivariate logistic regression to control the effect of confounders after verifying the bivariate logistic regression assumptions of multi-collinearity using spearman correlation and extreme values using scatter plot. A significant threshold of P < 0.05 was established.

Clinical and biochemical parameters

The following clinical and laboratory parameters were collected from the patient’s medical records: sex, age, residence, religion, aetiology, alcohol use history, treatment duration, decompensated and cirrhotic status at baseline, hepatitis C virus-RNA, platelets, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, serum bilirubin, serum hepatitis B surface antigen, viral load, and Albumin level.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was patient morbidity and mortality. The following were also addressed: identifying the aetiology of CLD, acute complications of CLD and treatment disparities. Patients referred for better treatment, died, self-discharged with lack of improvement and non-suppressed viral load and deteriorated clinical condition after end of treatment were considered to have poor treatment outcome.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of patients

A total of 213 CLD patient medical data were examined. Most of the study participants (72.8%) were male and Christians (93.9%). The participants’ ages ranged from 5 to 82 (SD ± 12.7), with the median age being 39. Approximately one-third (31.9%) were younger than 35. Approximately two thirds (63.8%) of the sample population lived in rural areas. (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic variables of CLD patients treated at hospitals of Bahir Dar City, 2024 (n = 213)

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 58 | 27.2 |

| Male | 155 | 72.8 | |

| Age in years | < 35 | 68 | 31.9 |

| 35–45 | 73 | 34.3 | |

| 46–65 | 61 | 28.6 | |

| ≥ 65 | 11 | 5.2 | |

| Religion | Christian | 200 | 93.9 |

| Muslim | 13 | 6.1 | |

| Residence | Urban | 77 | 36.2 |

| Rural | 136 | 63.8 |

Clinical characteristics

The most common (66.2%) etiology of CLD treated patients was viral hepatitis (HBV = 117, HCV = 30, and combined HBV and HCV = 6), followed by parasitic (23.0%) and ALD (11.5%). The parasitic causes of CLD include hyper-reactive malarial splenomegaly syndrome (4.7%) and hepatosplenic schistosomiasis (18.3%). Ascites accounted for 64.8% of all clinical presentations, with portal hypertension coming in second (52.1%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of CLD patients treated at hospitals of Bahir Dar City, 2024 (n = 213)

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cause of CLD | Diagnosed as: | ||

| Viral (HBV = 117, HCV = 30) | Both HBV & HCV = 6, ALD = 2 | 141 | 60.0 |

| HSS | ALD = 1, HBV = 3, HCV = 2 | 43 | 18.3 |

| ALD | HBV = 4, HCV = 1 | 27 | 11.5 |

| HMS | HCV = 4, HSS = 2 | 11 | 4.7 |

| NAFLD | 5 | 2.1 | |

| Others | TB = 2, Amoeba = 2, Drug = 4, ALD = 1 | 8 | 3.4 |

| Complications | Ascites | 138 | 64.8 |

| Portal hypertension | 114 | 52.1 | |

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | 13 | 6.1 | |

| Hepatorenal syndrome | 9 | 4.2 | |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 6 | 2.8 | |

| Comorbid condition | No | 161 | 75.6 |

| Yes* | 52 | 24.4 | |

| Stages of CLD | Compensated | 114 | 53.5 |

| Decompensated | 99 | 46.5 | |

| End stage liver disease | HCC | 60 | 60.6 |

| Cirrhosis | 39 | 39.4 | |

| Albumin level | ≥ 3.5 g/dl | 75 | 35.2 |

| < 3.5 g/dl | 138 | 64.8 | |

| APRI score | < 2 | 130 | 61.0 |

| ≥ 2 | 83 | 39.0 | |

| FIB-4 | Less likely (< 1.45) | 59 | 27.7 |

| Indeterminate (1.45–3.25) | 73 | 34.3 | |

| More likely (> 3.25 points) | 81 | 38.0 | |

|

Took appropriate treatment and regimen for specific CLD cause |

Yes | 97 | 45.5 |

| No | 116 | 54.5 | |

| Treatment duration | < 1 Years | 22 | 10.3 |

| 1–2 Years | 119 | 55.9 | |

| > 2 Years | 72 | 33.8 | |

| Clinical and serological patient outcome | Improved | 130 | 61.0 |

| Died (1 patient was on medication) | 5 | 2.4 | |

| Self-discharged (6 were on medication) | 13 | 6.1 | |

| No charge (31 took medication) | 65 | 30.5 |

Key: FIB– fibroscan, HMS - hyper-reactive malarial splenomegaly syndrome, HSS - hepatosplenic schistosomiasis, *Diabetes mellitus [9], heart failure [3], hypertension [14], pneumonia [6], renal disorder [4], tuberculosis [6], venous thromboembolism [3], HIV/AIDS [2] and others; ** no charge (66), self-discharged [13] and death [4]

The treatment lasted an average of 2.3 years, with a minimum of 3 months and a maximum of 10.5 years. When receiving treatment for CLD, nearly a quarter (24.4%) of the study group had at least one comorbid disorder. Of the CLD patients, 60.6% had HCC and 46.5% were decompensated. APRI scores of two or above were present in more than one-third (39.0%) of study populations. For the purpose of treating their CLD, less than half (45.5%) of patients were able to obtain cause-specific drugs, and 39.2% of those who were on medication had unsatisfactory treatment outcomes. Only one HCV patient used cause-specific medicine. Five people died out of the 39% of patients who had poor treatment outcomes overall.

Associated factors

Bivariate test results were not significant at p < 0.25 for the following variables: sex, religion, and causes of CLD, comorbid conditions, being on cause-specific medication, APRI score, FIB-4, and Alb level. Shorter treatment durations, clinical features of cirrhosis, and CLD stages all had a substantial impact on treatment failure. Compared to patients with non-decompensated CLD, those with decompensated CLD had a 2.7-fold (AOR = 2.68; 95%CI: 1.50–4.76, p = 0.001) increased risk of having unfavorable treatment outcomes. Patients with HCC are more likely than non-cancerous cirrhotic patients to encounter treatment failure (AOR = 2.68; 95%CI: 1.07–6.68, p = 0.035). Compared to treatment lasting less than a year, treatment lasting 1–2 years has a protective impact against treatment failure (AOR = 0.38; 95%CI: 0.15–0.98, p = 0.045) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factors associated with treatment failure among patients of CLD treated in hospitals of Bahir Dar City, 2024 (n = 213)

| Variable | Category | X2, % (n = 83) | COR (CI) | AOR (CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | < 35 | 29 (34.94) | 1 | 1 | |

| 35–45 | 25 (30.12) | 0.70 (0.35–1.39) | 0.40 (0.14–1.17) | 0.094 | |

| 46–65 | 27 (32.53) | 1.07 (0.53–2.15) | 0.36 (0.11–1.11) | 0.075 | |

| > 65 | 2 (2.41) | 0.30 (0.06–1.49) | 0.16 (0.03–1.06) | 0.057 | |

| Residence | Urban | 24 (28.92) | 1 | 1 | 0.122 |

| Rural | 59 (71.08) | 1.69 (0.94–3.05) | 1.61 (0.88–2.93) | ||

| Stages of CLD | Compensated | 33 (39.76) | 1 | 1 | 0.001** |

| Decompensated | 50 (60.24)** | 2.51 (1.42–4.41) | 2.68 (1.50–4.76) | ||

| End stage liver disease (n = 50) | Cirrhosis | 26 (52.0) | 1 | 1 | 0.035 * |

| HCC | 24 (48.0)* | 2.34 (1.02–5.36) | 2.68 (1.07–6.68) | ||

| Treatment duration | < 1 year | 12 (14.46) | 1 | 1 | |

| 1–2 years | 39 (46.99) | 0.41 (0.16–1.02) | 0.38 (0.15–0.98) | 0.045* | |

| > 2 years | 32 (38.55) | 0.67 (0.26–1.74) | 0.62 (0.23–1.65) | 0.339 |

Key: AOR - adjusted odd ratio, CI– confidence interval, CLD - chronic liver disease, COR - crude odd ratio, HCC - hepatocellular carcinoma

Discussion

Numerous pharmaceutical and non-pharmacologic treatments are intended to be used in the management of chronic liver disease. The purpose of this retrospective, hospital-based study was to evaluate the effects of treatment for chronic liver disease and the factors that contribute to it. Of the CLD patients, only 97 (45.5%) had cause-specific drugs for the management of their disease, and 38 (39.5%) suffered treatment failure.

According to our findings, men and rural tenants had higher rates of CLD. A study from Dessie comprehensive specialized hospital also reported high prevalence of CLD in males (66.3%) and rural residents (74.2%) [23]. The highest prevalence in males is comparable to the findings of Eastern Ethiopia (72.0%), Ghana (72.2%), Jimma (78.0%), Northern Ethiopia (81.9%) and Addis Ababa (91.5%) [18, 19, 24, 25, 26]. The higher prevalence in rural residents also supports the report of Jimma (53.2%) [19] but deviates from the findings of Northern Ethiopia (44.7%) [25]. Since their study was conducted at tertiary hospital, the difference may be attributed to study population.

In this study, the primary cause of CLD was chronic viral hepatitis infection at 60.0%, with parasitic infection following at 23.0% and alcoholic liver disease at 11.5%. These findings align with similar studies conducted in Ghana, which reported percentages of 75%, 8.9%, and 6.7% for chronic viral hepatitis infection, parasitic infection, and alcoholic liver disease, respectively [24].

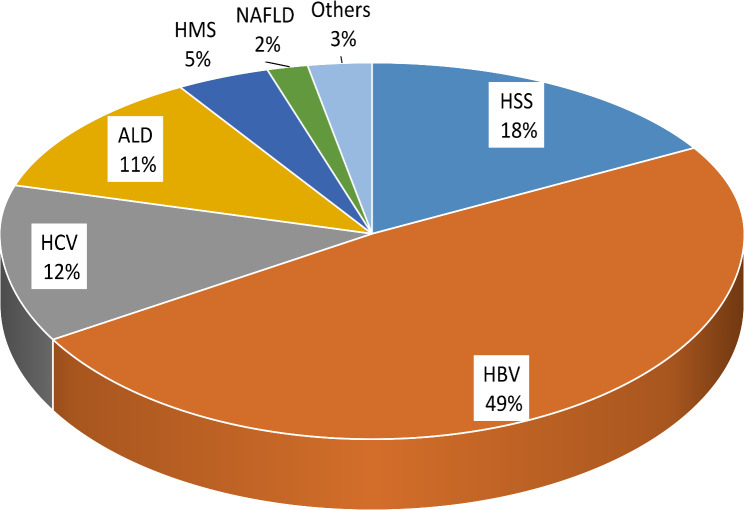

The increased prevalence of hepatic schistosomiasis and malaria observed in this study contrasts with previous findings from the APHI conducted at Dessie Comprehensive Specialized Hospital and global reports [5, 27]. This discrepancy may be attributed to differences in living standards and community awareness. The majority of our study population lived in rural areas where access to clean water and health information is insufficient. Additionally, the ongoing political and socioeconomic instability in the region contributes to this variation (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Percentage by causes of CLD among patients treated in hospitals of Bahir Dar city

The overall mortality rate in the current study is significantly lower than those reported in studies conducted in Eritrea (7.5%), teaching hospitals in Ethiopia (28.4%), and St. Paul’s Hospital in Addis Ababa (41%) [17, 18, 19]. Such variations could be due to differences in study populations, sample sizes, healthcare access, and study designs. The earlier studies primarily included patients admitted to medical wards who received only supportive care. Additionally, another factor that may have contributed to the variation in mortality rates is that many of the previous studies focused on specific etiologies of chronic liver disease (CLD).

In the present study, the stages of chronic liver disease (CLD), types of end-stage liver disease, and treatment duration emerged as significant predictors. Patients with decompensated CLD were approximately 2.7 times more likely to experience treatment failure compared to those with non-decompensated cirrhosis. This finding is consistent with previous research conducted in Taiwan (AHR = 4.36; 95% CI: 1.7–11.1), sub-Saharan Africa (AHR = 44.6; 95% CI: 6.1–328.1; p < 0.001), and Jimma, Ethiopia (AHR = 11.4; 95% CI: 2.4–54.0) [15, 16, 19, 28]. The type of end stage liver disease being HCC was about three fold more likely to have treatment failure compared with non-cancerous cirrhosis. This result supports the study of Gambia, in which patients with HCC had more than ten times poor prognosis than noncancerous cirrhosis [29]. On the other hand, the finding of this study contradicts with the outcome in China (AHR: 0.93 versus 0.90). The possible reason for this discrepancy may be due to that the study of China followed up more than 12,000 populations at 299 centers for up to 10 years. The availability of supportive and advanced treatment approach for management of HCC in their study could also make a difference [30]. Extended treatment duration is arbitrarily protective factor for treatment outcome in this study. One-to-two year’s treatment duration shows a better treatment outcome while it shows no value after two years of therapy. This is in line with the patient registry and treatment outcome system of England [31].

Limitations of the study

As the study design is retrospective and relies on secondary data, it may not be possible to access all the necessary information from the patient charts, making it challenging to determine the treatment outcomes for CLD. Additionally, the small sample size limits the ability to extrapolate the findings. There was variability among health professionals and hospitals in how each study variable was measured, which could result in underestimating or overestimating treatment outcomes. Factors such as blood glucose levels, nutritional status, BMI, education level, marital status, monthly income, and medication adherence were not included in the analysis because they were not fully documented in the patient follow-up charts.

Conclusion

Overall, this study indicated that the treatment outcomes for chronic liver disease in the study area are unfavorable. Key factors contributing to this poor outcome include cellular characteristics of cirrhosis, the stage of chronic liver disease, and shorter treatment duration.

Recommendations

This study demonstrated the importance of infection prevention through sanitation, alcohol moderation and vaccination, timely screening and early treatment. Hospitals should offer treatment for viral hepatitis, promote therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma. Multi-center prospective studies are necessary for more accurate assessment and prediction.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, we would like to express our gratitude and praise to the Almighty God, who has been our source of strength throughout our journey. We are grateful to Bahir Dar Health Science College and GAMBY Medical and Business College for their initiatives and unwavering support. Finally, we extend our heartfelt appreciation to the staff of Bahir Dar Health Science College for their valuable insights and invaluable guidance.

Abbreviations

- ALD

Alcoholic liver disease

- APRI

Aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index

- AST

Aspartate aminotransferase

- BMI

Body mass index

- CLD

Chronic liver disease

- DAA

Direct acting antivirals

- GFR

Glomerular filtration rate

- HBsAg

Hepatitis B surface antigen

- HBV

Hepatitis B virus

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- HCV

Hepatitis C virus

- NAFLD

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH

Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

- PEG-INF

Pegylated interferon

- RNA

Ribonucleic acid

- SPSS

Statistical package for social science

- SVR

Sustained viral response

- TDF

Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate

- WHO

World health organization

Author contributions

MAA, YAD, MEN, WTN, and SMB in conception, design, conduct, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretationMAA, YAD, MEN, WTN, and SMB have participated in drafting, revising, or critically reviewing the article, given final approval of the version to be published.

Funding

The study was conducted with the financial assistance from Bahir Dar Health Science College and GAMBY Medical and Business College.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

In line with the Declaration of Helsinki (1964), ethical approval was secured from the Ethics Review Committee of the Amhara Public Health Institute, referenced by the letter number APHI/R/D/D- 03/2349. The Amhara Public Health Institute Ethical Review Committee, along with the quality assurance departments of seven hospitals and the gastroenterology focal person, waived the need for informed consent to access patients’ data. All procedures were conducted in compliance with the applicable guidelines and regulations. Only numerical identifiers were utilized for reference. The confidentiality and anonymity of the participants were preserved by refraining from recording any identifying information, such as names or other personal identifiers.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Nagalli ASS. Chronic liver disease. July 3, 2023.(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554597/).

- 2.Fortes RC. Nutritional implications in chronic liver diseases. J Liver Res Disorders Therapy. 2017;3(5).

- 3.Devarbhavi H, Asrani SK, Arab JP, Nartey YA, Pose E, Kamath PS. Global burden of liver disease: 2023 update. J Hepatol. 2023;79(2):516–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gines P, Krag A, Abraldes JG, Sola E, Fabrellas N, Kamath PS. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet. 2021;398(10308):1359–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Disease GBD, Injury I, Prevalence C. Global, regional, and National incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1789–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Siervi S, Cannito S, Turato C. Chronic liver disease: latest research in pathogenesis, detection and treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(13). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Casanova J, Bataller R. Alcoholic hepatitis: prognosis and treatment. Gastroenterología Y Hepatología. 2014;37(4):262–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wigg AJ, McCormick R, Wundke R, Woodman RJ. Efficacy of a chronic disease management model for patients with chronic liver failure. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11(7):850–e81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu JH, Yu YY, Xu XY. Management of chronic liver diseases and cirrhosis: current status and future directions. Chin Med J (Engl). 2020;133(22):2647–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim W, Kim DJ. Severe alcoholic hepatitis-current concepts, diagnosis and treatment options. World J Hepatol. 2014;6(10):688–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leoni S, Tovoli F, Napoli L, Serio I, Ferri S, Bolondi L. Current guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review with comparative analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24(30):3361–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liaw YF. Impact of therapy on the outcome of chronic hepatitis B. Liver Int. 2013;33(Suppl 1):111–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ethiopia MoH. Standard treatment guidelines for general hospital. 2021;4th ed:269– 89.

- 14.Aithal GP, Palaniyappan N, China L, Harmala S, Macken L, Ryan JM, et al. Guidelines on the management of Ascites in cirrhosis. Gut. 2021;70(1):9–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Desalegn H, Aberra H, Berhe N, Medhin G, Mekasha B, Gundersen SG, et al. Predictors of mortality in patients under treatment for chronic hepatitis B in Ethiopia: a prospective cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019;19(1):74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Desalegn H, Orlien SMS, Aberra H, Mamo E, Grude S, Hommersand K, et al. Five-year results of a treatment program for chronic hepatitis B in Ethiopia. BMC Med. 2023;21(1):373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghebremeskel GG, Berhe Solomon M, Achila OO. Real-world treatment outcome of direct-acting antivirals and patient survival rates in chronic hepatitis C virus infection in Eritrea. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):20792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mulugeta Adhanom HD. Magnitude, clinical profile and hospital outcome of chronic liver disease at St. Paul’s hospital millennium medical college, addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2017;55(4).

- 19.Terefe Tesfaye B, Gudina EK, Bosho DD, Mega TA. Short-term clinical outcomes of patients admitted with chronic liver disease to selected teaching hospitals in Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(8):e0221806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minwuyelet Maru Temesgen SLH. Birtukan Shiferaw ayalew et.al. Magnitude and trends of chronic liver disease: A retrospective hospital based study in Eastern Amhara region, Northeast Ethiopia. J Spleen Liver Res. 2023;1(4).

- 21.Tsertsvadze T, Gamkrelidze A, Nasrullah M, et al. Treatment outcomes of patients with chronic hepatitis C receiving sofosbuvir-based combination therapy within National hepatitis C elimination program in the country of Georgia. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20(1):30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yemisrach Chanie PS, Miftah Delil. Treatment of chronic hepatitis C in Ethiopia: A prospective cohort study. Millennium Journal of Health; 2022.

- 23.Gillespie IA, Chan KA, Liu Y, Hsieh SF, Schindler C, Cheng W, et al. Characteristics, treatment patterns, and clinical outcomes of chronic hepatitis B across 3 continents: retrospective database study. Adv Ther. 2023;40(2):425–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aidoo M, Sulemana Mohammed B. Distribution and determinants of etiologies and complications of chronic liver diseases among patients at a tertiary hospital in a lower economic region of Ghana. Cent Afr J Public Health. 2020;6(5).

- 25.Migbar Sibhat TK, Dawit Aklilu. Risk factors of chronic liver disease among adult patients in tertiary hospitals, Northern Ethiopia: an unmatched case-control study. 2022.

- 26.Orlien SMS, Ismael NY, Ahmed TA, Berhe N, Lauritzen T, Roald B, et al. Unexplained chronic liver disease in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18(1):27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang FS, Fan JG, Zhang Z, Gao B, Wang HY. The global burden of liver disease: the major impact of China. Hepatology. 2014;60(6):2099–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Everson GT, Hoefs JC, Seeff LB, Bonkovsky HL, Naishadham D, Shiffman ML, et al. Impact of disease severity on outcome of antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C: lessons from the HALT-C trial. Hepatology. 2006;44(6):1675–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ndow G, Vo-Quang E, Shimakawa Y, Ceesay A, Tamba S, Njai HF, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in the Gambia, West Africa: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Glob Health. 2023;11(9):e1383–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hou JL, Zhao W, Lee C, Hann HW, Peng CY, Tanwandee T, et al. Outcomes of Long-term treatment of chronic HBV infection with Entecavir or other agents from a randomized trial in 24 countries. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(2):457–67. e21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Helen Harris ACaSM. Hepatitis C treatment monitoring in England. Public Health England 2018.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.