Abstract

Background

Psychological resilience refers to maintaining or regaining psychological well-being after experiencing adversity, trauma, or stress. There is evidence suggesting that cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can significantly enhance an individual’s coping skills. However, the overall effectiveness of CBT on resilience among cancer patients remains unclear. Therefore, this study systematically evaluated the impact of CBT on resilience among cancer patients.

Methods

The PubMed, PsycINFO, Cochrane Library, CINAHL, and Embase databases were searched using keywords. Two researchers independently conducted a rigorous evaluation of the quality of the evidence using the GRADE system and independently performed data extraction. A meta-analysis was conducted to calculate the experimental group's effect size and to explore the effects of CBT on enhancing resilience.

Results

Thirteen randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were included in this meta-analysis. The effect of CBT on increasing resilience among cancer patients was small but significant immediately after the intervention (g = 1.211; p < 0.001). The results showed that CBT delivered via mobile devices was more effective than face-to-face CBT (β = 0.284; P = 0.012). Additionally, group CBT also outperformed individual CBT (β = 0.181; P = 0.042). Furthermore, CBT was more effective among patients with existing tumors (β = 0.285; P = 0.037). The evidence regarding the effects of CBT on resilience was found to be of moderate strength.

Conclusions

The results of this study indicate CBT can improve resilience among cancer patients. These findings underscore the importance of considering delivery methods and formats when implementing CBT interventions, with mobile device delivery and group formats resulting in better outcomes. The positive effects of CBT on patients with existing tumors highlight the importance of delivering this therapy in specific clinical contexts. Overall, this study provided moderately strong evidence that CBT is a valuable tool for enhancing resilience among cancer patients.

Trial registration

CRD42021256841.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12888-025-06628-3.

Keywords: Cancer, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Resilience, Meta-Analysis, Psycho-oncology

Introduction

The global incidence of cancer continues to rise, with an estimated 19.3 million new cancer cases (18.1 million when excluding nonmelanoma skin cancer) occurring in 2020 alone [1]. The development of a tumor not only impairs a patient's physical well-being but also significantly increases their psychological stress [2]. During cancer rehabilitation, more than one-third of patients with cancer may experience symptoms of depression or anxiety disorders [3]. These mental disorders not only negatively impact patients' quality of life but also compromise treatment adherence and overall therapeutic outcomes, thus placing an additional burden on healthcare resources [4]. Although tumors and treatments can increase to cancer patients’ psychological stress, some patients adapt mentally and face challenges positively, with psychological resilience playing a key role in this phenomenon [5].

Psychological resilience is a crucial psychological defense mechanism that improves patients' quality of life by mitigating psychological distress and alleviating symptoms of depression [6]. Psychological resilience refers to an individual's capacity to maintain or regain psychological well-being in the face of adversity, trauma, or stress (D, 1987). Patients’ self-perceived resilience has been linked to significant clinical outcomes, such as psychological distress, health-related behaviors, and ease in conveying values to medical teams [7]. A review of cancer patients revealed that their average resilience score is considerably lower than that of the general population [8, 9]. Research has also revealed that despite differences in personality traits among cancer patients, enhancing psychological resilience can significantly improve their cognitive function, thereby further highlighting the important role of resilience in protecting the physical and mental health of cancer patients [10].

These results also emphasize the importance of effective, evidence-based treatments for enhancing resilience among cancer patients [11]. Current therapeutic strategies to enhance psychological resilience are diverse and include mindfulness-based stress reduction, support groups, and resilience training programs [12]. These approaches aim to reduce stress, build coping skills, and promote emotional well-being through various techniques [13]. Additionally, some interventions combine multiple methods to create a comprehensive approach that targets both the emotional and the cognitive aspects of resilience [14]. Among these, cognitive‒behavioral therapy (CBT) has gained widespread recognition as one of the most frequently utilized interventions [15].

CBT is a form of psychological treatment that addresses maladaptive behaviors and thought patterns through a combination of cognitive and behavioral strategies to improve emotional regulation and develop personal coping strategies [16]. The purpose of CBT is to change negative thought patterns, internal dialogs, and fixed beliefs. The effectiveness of CBT in enhancing psychological resilience and posttraumatic growth was examined in a systematic review published in 2019, which included 15 randomized controlled trials [17]. In the ensuing years, several well-designed study protocols and preliminary feasibility studies have been published, further supporting the role of CBT as a major tool for enhancing psychological resources [18]. Despite the growing body of research on the effectiveness of CBT in enhancing psychological resilience among various patient populations, a meta-analysis specifically examining the effects of CBT among cancer patients should be conducted to draw more robust conclusions about this particular population.

Previous studies have examined the impact of CBT on psychological resilience and posttraumatic growth in various patient populations, including individuals with anxiety, depression, and PTSD [19]. However, cancer patients have been largely excluded from these investigations; alternatively, the studies that do include cancer patients have not specifically addressed the unique challenges this group faces. Furthermore, there is a lack of consensus on the most effective formats, delivery methods, and duration of CBT for cancer patients. CBT is a well-established psychological intervention and has been widely used to improve mental health and enhance psychological resilience [20]. However, research specifically focusing on its effects, adaptability, and optimization for cancer patients remains limited and warrants systematic research.

Therefore, the current systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to investigate the effects of CBT on psychological resilience among cancer patients. In particular, the effects of various formats, delivery methods, and sessions were examined in order to provide guidance to healthcare professionals on how to tailor CBT interventions to maximize benefits for cancer patients and enhance their quality of life. We hypothesized that CBT would enhance resilience.

Methods

This study was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses PRISMA guidelines [21] and was preregistered with PROSPERO (registration No. CRD42021256841).

Eligibility criteria

Only studies published in English or Chinese were eligible for this systematic review and meta-analysis. Protocols and gray literature were excluded. The literature was screened in strict accordance with the population, intervention, comparator, and outcome (PICO) framework [22].

Population

Eligible participants included adult cancer patients aged 18 years or older. Studies involving children and adolescents with cancer, as well as studies focusing on caregivers of cancer patients, were excluded.

Intervention

Various intervention strategies were eligible, including cognitive restructuring, exposure therapy, behavioral activation, problem-solving skills training, relaxation training, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) and psychotherapy under the umbrella of CBT. These interventions did not have to directly focus on resilience.

Comparator

Eligible studies had a control group, such as a waitlist or treatment-as-usual group, for comparison purposes. Studies that solely compared two active psychological interventions without a control group (for instance, in noninferiority trials) or observational studies employing uncontrolled pre-post designs were not considered for inclusion in this meta-analysis.

Outcome

The outcome of interest was resilience levels, regardless of whether they were assessed as primary or secondary outcomes. Eligible studies had to report the mean, standard deviation, and effect size for each group, both pre- and postintervention. Alternatively, studies that provided data that can be transformed into an effect size (ES) for analysis were eligible for inclusion.

Information sources

The PubMed, PsycINFO, Cochrane Library, CINAHL, and Embase databases were systematically searched up to August 1, 2023, using keywords to identify relevant RCTs, experimental studies, and pre- and postcontrol trials. Through backward searches (snowballing), we also searched the reference lists of relevant systematic reviews and to identify additional eligible studies that were not retrieved during the search process.

Search strategy

Keywords related to cancer (e.g., "Neoplasms/psychology"[Mesh], "Medical Oncology"[Mesh], cancer, oncology, malignancy, tumor), intervention (e.g., Cognitive Behavioral Therapy"[Mesh], psychotherap* OR “cognitive therap*” OR “cognitive-behav* therap*” OR “psycholog* treatment” OR “psycholog* intervention” OR “mindfulness” OR “problem-solving”), and resilience (e.g., "Resilience, Psychological"[Mesh], “psychological resilience” OR "resilience*" OR “psychological adjustment”) were used for the search strategy.

The specific search strategies for each database are provided in the attached SDC Table.

Selection procedure

Two authors (Xiang and Zhu) independently screened all potentially relevant studies on the basis of the PICO framework after reviewing the literature. Disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third author (Wan) until a consensus was reached. To assess interrater reliability, Cohen's kappa was calculated to quantify the level of agreement between the two independent reviewers. Discrepancies were resolved vis discussion and consensus. Xiang and Zhu subsequently performed the final screening independently by reading the full texts of the selected studies to ensure eligibility.

Data extraction

Data extraction was independently carried out by two researchers (Xiang, Zhu) based on the Cochrane Intervention System Evaluation Manual, which was used to determine which data to extract and to design a data extraction form. The following data were extracted: the general information of the study (author, nationality), sample characteristics (sex, age), cancer type and stage, measurement tools, intervention methods, form of intervention, frequency, time, number of participants in the experimental and control groups, evaluation time, intervention indicators, means of continuous indicators and standard deviations.

Resilience assessment

At present, there are many tools for measuring resilience, including the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC), the Resilience Scale for Adults (RSA), the Resilience Scale (RS), and the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS). Owing to the reliability and validity of the scale and the scope of application, our search terms were not restricted by the different names of the measurement tools. Instead, each article's resilience measurement, including measured content, was reviewed for congruence with our operationalization of resilience.

Risk of bias assessment

Two reviewers (Xiang, Zhu) independently assessed the quality of all studies using the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool [23]. The following risk of bias domains were evaluated: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other sources of bias. Additionally, we divided "other sources of bias" into two categories: "treatment integrity" (such as therapist training and fidelity) and "conflict of interest" (including therapists and/or original designers). Disagreements were resolved by consulting a third author (Wan).

Meta-analysis procedures

Analyses were conducted using the Metan package in Stata 15.0. The results were presented in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 Checklist.

Computing Effect Size (ES)

In this systematic review, resilience scores were considered continuous variables; therefore, the mean difference (MD) of preintervention, postintervention, or change data were calculated, and the combined effect size was determined via the weighted mean difference (WMD) or standard mean difference (SMD). Unless the above value was provided in the included studies, it was be excluded from the meta-analysis. If studies reported results for more than one measure per outcome, we chose the primary outcome to calculate the average ES of each measurement. We included this ES as the final result to ensure that each study had only one ES. Hedges’ g was used as the standardized between-group ES.

Heterogeneity

We assessed the clinical heterogeneity and methodological heterogeneity of the included studies [24] and then evaluated the statistical heterogeneity. P > 0.1 or I2 ≤ 50% indicated a low level of heterogeneity; in such cases, the fixed effects model was used for meta-analysis. P ≤ 0.1 or I2 > 50% indicated a high degree of heterogeneity; in such cases, the random effects model was applied. Random effects models were used for all analyses [25]. Stata version 15.1 was employed to systematically review the effect of CBT on resilience among cancer patients.

Results

Study selection

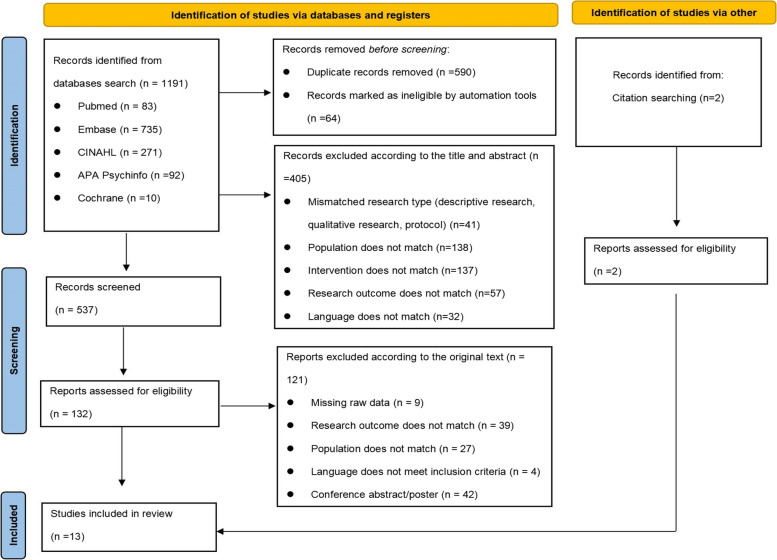

Figure 1 illustrates the study selection process. A total of 1,191 articles were initially retrieved from the databases. A total of 1,059 duplicate articles were removed, leaving 132 articles for further screening. A total of 13 articles ultimately met the eligibility criteria for this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the Study Selection Process

Study characteristics and quality

CT characteristics

A total of 1185 patients were included in this systematic review (see Table 1). The mean sample size of the included studies was 91. Thirteen studies reported postintervention data, and two studies reported long-term (follow-up) data (the follow-up durations after the intervention were 1 month and 3 months, separately). Most experimental studies used routine psychological care as a control intervention, and seven studies used psychological resilience as the main outcome indicator. Most studies were controlled trials (K = 13), with most control groups receiving no therapy (K = 13). All but two studies were conducted in China; the other two studies were conducted in the United States and Iran, separately. In most studies, the majority of participants were women. Breast cancer was the most frequent cancer diagnosis (K = 5). In half of the studies (K = 7), the participants had no evidence of a tumor.

Table 1.

Study Characteristics (N = 13)

| Study | Cancer type | Age | No. of arms(number of participants in IG†/CG†) | Resilience measure | Resilience as primary outcome | Intervention type | CBT delivery; | Measurement time point |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer present (yes/no) | Gender | CBT format; | ||||||

| CBT no. of session; | ||||||||

| Cancer stage | CBT duration, weeks | |||||||

| Peihua Wu 2018-China [26] |

Breast cancer; Yes; Stage 0–3 |

Mean age: 51.2; Female (100%) |

2(20/20) | RS† | Yes | Psycho-educational interventions (PEIs)② | Face-to-face | Before the first chemotherapy session (T0) and at 2 weeks after the final chemotherapy session (T1) |

| Individual | ||||||||

| 6 sessions | ||||||||

| 6 weeks | ||||||||

| Kaina Zhou 019-China [27] |

Breast cancer; Yes; Stage 0–3 |

Mean age: 44.56; Female (100%); |

2(66/66) | CD-RISC† | Yes | Cyclic adjustment training② | Mobile device | Before the treatment (T0), immediately after the treatment (T1) |

| Individual | ||||||||

| 12 sessions | ||||||||

| 12 weeks | ||||||||

| Chuan Yan Lin 2020-China [28] |

Colon cancer; No; Stage 2–4 |

Mean age: 42; Males (68%); |

2(100/100) | CD-RISC† | Yes | Attention and interpretation therapy (AIT)① | Face-to-face | Before the treatment (T0), immediately after the treatment (T1) |

| Group | ||||||||

| 10 sessions | ||||||||

| 10 weeks | ||||||||

| Jiajia Zhang 2021-China [29] |

Pituitary adenoma; No; Stage 2–4 |

Mean age: 40 Male (55%); |

2(50/50) | CD-RISC† | Yes | Cognitive bias modification (CBM)① | Mobile device | Before the treatment (T0), immediately after the treatment (T1) |

| Individual | ||||||||

| 8 sessions | ||||||||

| 8 weeks | ||||||||

| Yulian Lei 2019-China [30] |

Prostate cancer; Yes; NR |

Mean age: 62.65; Male (100%); |

2(60/60) | CD-RISC† | Yes | Cognitive Behavior Intervention② | Face-to-face | Before the treatment (T0), immediately after the treatment (T1) |

| Individual | ||||||||

| 5 sessions | ||||||||

| 5 weeks | ||||||||

| Caitlin E. Loprinzi 2011-United States [31] |

Breast cancer; No; Stage 0–3 |

Mean age: 46; Female (100%); | 2(12/8) | CD-RISC† | No | Stress Management and Resiliency Training② | Face-to-face | Before the treatment (T0), immediately after the treatment (T1) |

| Individual | ||||||||

| 2 sessions | ||||||||

| 12 weeks | ||||||||

| Yao Zhang 2023-China [32] |

Breast cancer; Yes; NR; |

Mean age 47.37; Female (100%); |

2(49/49) | CD-RISC† | No | Family‑centered positive psychological intervention② | Face-to-face |

Outcome measures compared at baseline (T1), immediately after the intervention (T2), and at 1-month follow-up (T3) |

| Couple | ||||||||

| 4 sessions | ||||||||

| 4 weeks | ||||||||

| Weiping Yang 2021-China [33] |

Malignant glioma patients; Yes; Stage 2–4; |

Mean age (53.1 ± 10.6); Male (50%); |

2(30/30) | CD-RISC† | No | Cognitive Behavior Intervention① | Face-to-face | Before the treatment (T0), immediately after the treatment (T1) |

| Individual | ||||||||

| 6 sessions | ||||||||

| 6 weeks | ||||||||

| Na Zhang 2021-China [34] |

Malignant lymphoma patients; Yes; Stage 2–4; |

Mean age (52.81 ± 9.64); Male (70.63%); |

2(72/88) | CD-RISC† | Yes | Cognitive Behavior Intervention① | Mobile device | Before the treatment (T0), immediately after the treatment (T1) |

| Group | ||||||||

| 8 sessions | ||||||||

| 4 weeks | ||||||||

| Qiaoping Wang 2018-China [35] |

Esophageal cancer patients; No; Stage 0–3; |

Mean age (54.4 ± 14.1); Male (56.94%); |

2(36/36) | CD-RISC† | No | Cognitive Behavior Intervention① | Face-to-face | Before the treatment (T0), immediately after the treatment (T1) |

| Individual | ||||||||

| 6 sessions | ||||||||

| 2 weeks | ||||||||

| Kemei Wu 2020-China [26] |

Mixed cancer; No; Stage 0–3; |

Mean age (54.03 ± 4.87); Male (57%); |

2(50/50) | CD-RISC† | No | Cognitive Behavior Intervention① | Face-to-face | Before the treatment (T0), immediately after the treatment (T1) |

| Group | ||||||||

| Not clearly | ||||||||

| Not clearly | ||||||||

| Juan Wang 2022-China [36] |

Thyroid cancer; No; Stage 0–3; |

Mean age (51.78 ± 8.12); Male (29.31%); |

2(26/27) | CD-RISC† | No | Cognitive Behavior Intervention① | Face-to-face | Before the treatment (T0), immediately after the treatment (T1) |

| Group | ||||||||

| 8 sessions | ||||||||

| 8 weeks | ||||||||

| Fatemeh Faghani 2022-Iran [37] |

Mixed cancer; No; NR; |

Mean age: 37.9; Female (60%); |

2(15/15) | CD-RISC† | No | Mindfulness-based supportive psychotherapy② | Face-to-face | Before the treatment (T0), immediately after the treatment (T1) and in a 3-month follow-up (T2) |

| Individual | ||||||||

| 6 sessions | ||||||||

| 6 weeks |

Abbreviations: †CD-RISC: Conner–Davison Resilience Scale;

†RS: Resilience Scale;

†IG: intervention group;

†CG: control group;

① Traditional CBT; ② Contemporary CBT

Thirteen of the included studies used traditional or contemporary CBT as the main intervention measure. Seven interventions involved a traditional CBT framework, and six interventions involved contemporary CBT. Traditional CBT was defined as interventions that adhere to established cognitive‒behavioral principles, including not only models based on Beck’s therapy but also models based on information processing. These models assume that individual biases lead to decreased resilience. On the other hand, contemporary CBT is characterized by a focus on cognitive processes—such as cognitive bias, attention and interpretation—rather than the content of thoughts, aiming to change the interaction between individuals and their internal experiences. Ten studies involved face-to-face interventions, and 3 other studies were conducted via the internet, telephone, etc. Eight interventions were individualized, four interventions were group-based, and one intervention was couple-based. The number of sessions ranged from one to 12 (mean, 6).

Main effects

Table 2 summarizes the results of the meta-analyses, and forest plots are presented in Fig. 2.

Table 2.

Pooled Postintervention Effects of CBT on Resilience among Cancer Patients (N = 13)

| Effect | Sample size | Heterogeneity | Global Effect Size | Failsafe No.‡ | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K | N | Q⇃ | df | P | I2 | Hedges’s ga | 95% CI | P | |||

| Overall combined effect | 13 | 1185 | 53.92 | 12 | < 0.001 | 77.7% | 1.211 | 0.933 | 1.490 | < 0.001 | 1141 |

| Gender: Mixed | 8 | 775 | 26.75 | 7 | 0.008 | 73.8% | 1.355 | 1.031 | 1.679 | < 0.001 | 559 |

| Gender: female | 4 | 290 | 11.83 | 3 | 0.001 | 74.6% | 0.758 | 0.230 | 1.286 | < 0.001 | 36 |

| Gender: male | 1 | 120 | 0 | 0 | / | / | 1.587 | 1.175 | 1.999 | < 0.001 | 14 |

| Cancer type: breast | 5 | 410 | 20.31 | 4 | < 0.001 | 80.3% | 0.946 | 0.445 | 1.447 | < 0.001 | 85 |

| Cancer type: other/mixed | 8 | 775 | 26.79 | 7 | < 0.001 | 73.9% | 1.367 | 1.043 | 1.691 | < 0.001 | 559 |

| Cancer present: Yes | 6 | 610 | 36.08 | 5 | < 0.001 | 86.1% | 1.346 | 0.852 | 1.840 | < 0.001 | 323 |

| Cancer present: No | 7 | 575 | 16.23 | 6 | 0.013 | 63.0% | 1.106 | 0.791 | 1.421 | < 0.001 | 244 |

| Cancer stage: 0–3 | 6 | 417 | 8.62 | 5 | 0.125 | 42.0% | 0.997 | 0.714 | 1.280 | < 0.001 | 150 |

| Cancer stage: 2–4 | 4 | 520 | 11.17 | 3 | 0.011 | 73.1% | 1.669 | 1.265 | 2.074 | < 0.001 | 259 |

| Cancer stage: NR | 3 | 248 | 12.36 | 2 | 0.002 | 83.8% | 1.035 | 0.322 | 1.749 | < 0.001 | 39 |

| Resilience measurement tool: RS | 1 | 40 | 0 | 0 | / | / | 0.525 | −0.107 | 1.156 | < 0.001 | 0 |

| Resilience measurement tool: CD-RISC | 12 | 1145 | 47.92 | 11 | 0.001 | 77.0% | 1.251 | 0.970 | 1.531 | < 0.001 | 1085 |

| Resilience as secondary outcome | 7 | 433 | 16.14 | 6 | 0.013 | 62.8% | 0.991 | 0.644 | 1.337 | < 0.001 | 452 |

| Resilience as primary outcome | 6 | 752 | 20.93 | 5 | 0.001 | 76.1% | 1.416 | 1.074 | 1.758 | < 0.001 | 151 |

| Intervention type: traditional CBT | 7 | 745 | 24.84 | 6 | 0.001 | 75.8% | 1.400 | 1.059 | 1.742 | < 0.001 | 503 |

| Intervention type: contemporary CBT | 6 | 440 | 20.42 | 5 | 0.001 | 75.5% | 0.936 | 0.500 | 1.372 | < 0.001 | 123 |

| CBT format: individual | 8 | 574 | 20.09 | 7 | 0.005 | 65.2% | 1.146 | 0.825 | 1.466 | < 0.001 | 305 |

| CBT format: group | 4 | 513 | 14.11 | 3 | 0.003 | 78.7% | 1.479 | 1.032 | 1.927 | < 0.001 | 217 |

| CBT format: couple | 1 | 98 | 0 | 0 | / | / | 0.564 | 0.160 | 0.968 | < 0.001 | 1 |

| CBT delivery: face-to-face | 10 | 793 | 38.98 | 9 | 0.001 | 76.9% | 1.103 | 0.769 | 1.438 | < 0.001 | 500 |

| CBT delivery: mobile device | 3 | 392 | 9.95 | 2 | 0.007 | 79.9% | 1.472 | 0.966 | 1.978 | < 0.001 | 127 |

| CBT duration, weeks ≤ 6 | 7 | 580 | 39.02 | 6 | 0.001 | 84.6% | 1.217 | 0.737 | 1.696 | < 0.001 | 306 |

| CBT duration, weeks > 6 | 5 | 505 | 11.91 | 4 | 0.018 | 66.4% | 1.248 | 0.885 | 1.611 | < 0.001 | 189 |

| CBT duration, weeks: NR | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | / | / | 0.973 | 0.557 | 1.388 | < 0.001 | 5 |

Abbreviations: CBT cognitive behavioral therapy, RS Resilience Scale, CD-RISC Conner‒Davison Resilience Scale

aEffect size: Hedges’s g positive value indicates an effect size in the hypothesized direction. All pooled effect sizes were obtained using a random effects model and categorized as follows: small (0.2), medium (0.5), or large (0.8)

⇃Q statistic: P values < 0.1 indicated high heterogeneity. I2 statistics: 0% (no heterogeneity), 25% (low heterogeneity), 50% (moderate heterogeneity), and 75% (high heterogeneity). Meta-analysis was conducted using a random effects model

‡Failsafe No: Number of nonsignificant studies for which the P value was nonsignificant (P > 0.05)

Fig. 2.

Postintervention Impact of CBT on Psychological Resilience Based on a Forest Plot

The pooled postintervention ES was large and statistically significant (g = 1.211; 95% CI, 0.933 to 1.490; P < 0.001). There was no evidence of publication bias, and the failsafe number for effects at posttreatment (failsafe N = 1141) exceeded the criterion (N = 115) [38], thus indicating a robust result.

Heterogeneity

There was a considerable amount of heterogeneity among the included studies, as evidenced by the high I2 value of 77.7% postintervention. This significant heterogeneity was further indicated by statistically significant Q tests. The primary causes of this heterogeneity appear to be substantial differences in intervention methods, measurement tools, and patient characteristics across the studies. Another factor contributing to this heterogeneity is the limited number of studies included in the analysis, which can limit the generalizability of the findings and may not capture the full spectrum of variability in intervention methods, measurement tools, and patient characteristics.

Subgroup and moderation analyses

Table 2 shows the results of the subgroup analyses based on gender, cancer type, cancer present, cancer stage, resilience as the primary outcome, resilience measurement tool, intervention type, CBT format, CBT delivery, and CBT duration (weeks). At postintervention, almost all the ESs were large in magnitude.

Meta-regression analysis was conducted to investigate how covariates influenced the effectiveness of CBT in enhancing resilience among cancer patients. The results of the meta-regression analyses on the covariates of postintervention effects are presented in Table 3. Postintervention, the effects of CBT delivered via mobile devices (g = 1.472) were stronger than those of face-to-face CBT (g = 1.103; β = 0.284; P = 0.012). The group format of CBT (g = 1.479) was found to be more effective than the individual format in terms of improving resilience among cancer patients (g = 1.146; β = 0.181; P = 0.042). Furthermore, CBT was more effective at enhancing resilience in patients with existing tumors (g = 1.346) than in those without tumors (g = 1.106; β = 0.285; P = 0.037).

Table 3.

Results of Meta-regression Analyses on the Covariates of Postintervention Effects (N = 13)

| Variable | Coef | Std. Err | t | P >|t| | 95% Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer type: mixed (referent: breast cancer) | 1.021 | 0.826 | 1.240 | 0.342 | −2.533 | 4.574 |

| Cancer Present: yes (referent: no) | 1.047 | 0.285 | 2.179 | 0.037* | 0.167 | 1.926 |

| Cancer stage: 0–3 (referent: 2–4) | −0.201 | 0.186 | −1.080 | 0.392 | −1.000 | 0.598 |

| Gender: mixed (referent: female) | −0.126 | 0.451 | −0.280 | 0.806 | −2.066 | 1.814 |

| Resilience as primary outcome: yes (referent: no) | 0.922 | 0.228 | 4.050 | 0.056 | −0.058 | 1.901 |

| Resilience measurement tool: CD-RISC (referent: RS) | 1.590 | 0.491 | 3.240 | 0.084 | −0.522 | 3.701 |

| Intervention type: traditional CBT (referent: contemporary CBT) | 0.240 | 0.520 | 0.460 | 0.690 | −1.999 | 2.480 |

| CBT delivery: face-to-face (referent: mobile device) | −0.765 | 0.284 | 2.681 | 0.012* | −1.485 | −0.044 |

| CBT format: group (referent: individual) | −0.105 | 0.181 | −0.580 | 0.042* | −0.570 | 0.360 |

| CBT duration weeks: ≤ 6 weeks (referent: > 6 weeks) | 0.044 | 0.176 | 0.25 | 0.825 | −0.713 | 0.801 |

| _cons | −5.225 | 2.552 | −2.047 | 0.018* | −16.206 | 5.756 |

Abbreviations: *P < 0.05

Risk of bias

The two raters (Xiang, Zhu) agreed on 87 (95.6%) of the 91 risk of bias assessments. The Cohen's kappa for full-text screening was 0.817, indicating a high level of agreement between the reviewers. Figure 3 shows the final results of the risk of bias assessments for the included studies.

Fig. 3.

Risk of Bias Assessment

Overall quality of the evidence

The GRADE system was used to qualify the overall quality of the evidence from RCTs. All 13 controlled trials were included in this meta-analysis. As a result of concerns regarding research heterogeneity, the grade of evidence for controlled trials was downgraded to moderate. The intervention measures were quite different, and they were not conducted in strict accordance with CBT principles.

Discussion

The primary objective of our study was to evaluate the effect of CBTs on resilience among cancer patients. Thirteen controlled trials were included in our meta-analysis, which indicated that CBT had a statistically significant effect on resilience. This effect was large in magnitude, and it was observed immediately after the interventions. There was no evidence of publication bias, thus providing support for our hypothesis that CBT was effective in enhancing resilience among cancer patients. These findings are encouraging, given that managing resilience is a common unmet need among survivors of cancer [39].

The results of this study demonstrated that CBT has a significant effect on improving psychological resilience in cancer patients, thus helping these individuals build stronger adaptive coping mechanisms. Cancer patients often face unique psychological challenges, such as disease progression, fear of death, and loneliness [40]. CBT involves a structured approach of identifying negative thoughts, adjusting cognitive biases, and enhancing self-efficacy, thus leading to significant improvements in psychological resilience [41]. Related studies have confirmed that CBT is more effective than other types of psychotherapy in terms of enhancing psychological resilience in cancer patients [12]. On the basis of these findings, it is recommended that CBT be incorporated as a routine psychological support intervention for cancer patients in clinical practice, particularly with the aim of alleviating emotional issues such as anxiety and depression.

Compared with face-to-face CBT, mobile-based CBT exerted more positive intervention effects. Mobile devices represent a key future avenue for psychological interventions, as virtual agents powered by artificial intelligence (AI) and big data can effectively communicate and empathize with patients, adjusting the learning content according to their pace and overcoming the limitations of time and space [42]. Future research could integrate structured intervention content (such as emotional regulation, cognitive restructuring, and relaxation training) into mobile applications or online platforms; leverage AI and big data to create user profiles for patients; track trajectories of patients’ emotions, cognition, and behavior; and deliver personalized CBT. This platform would be designed for cancer patients to use both in the hospital and at home, with personalized feedback and real-time support, enabling patients to engage in interventions anytime and anywhere and improving the convenience and effectiveness of treatment [42, 43].

Group CBT is more effective than individual CBT in terms of enhancing psychological resilience among cancer patients. During treatment, cancer patients often experience emotional and physical isolation, and group CBT provides emotional comfort and encouragement, helping them alleviate isolation and stigma through shared stories [44]. Group interactions promote cognitive shifts, with participants gaining inspiration from others' coping strategies and learning to find strength in adversity [45]. Research shows that social support is crucial for the mental health of cancer patients and that group therapy leverages the power of the group to help patients better cope with psychological challenges [46]. Group CBT not only enhances patients' psychological resilience but also provides an inclusive and supportive system, further improving treatment outcomes.

This study revealed that demographic and clinical variables, such as gender and cancer stage, did not significantly influence the effectiveness of CBT in improving psychological resilience. This result supports the broad applicability of CBT to enhance psychological resilience across different patient groups. Although previous studies have reported the significant effects of CBT in breast cancer patients [18], the current study did not find a notable response in this group. This discrepancy may be related to individual differences in psychological needs [42], misalignment of intervention content with deeper emotional challenges (e.g., body image loss, uncertainty), cultural influences favoring group interaction over individual therapy, limitations in intervention design (e.g., fatigue and attention span), or insensitivity of measurement tools to subtle changes beyond anxiety and depression.Future research should focus specifically on breast cancer patients to explore the differential effects of CBT across different cancer types.

Clinical implications

This study provides important clinical guidance for improving psychological resilience in cancer patients. The results demonstrate that CBT has a significant effect on improving the mental health of cancer patients, particularly with respect to emotional regulation and stress management. Additionally, both mobile-based CBT and group CBT show great potential in clinical practice. Mobile-based CBT overcomes the time and space limitations of traditional treatment models, enhancing flexibility and accessibility, especially for remote interventions and patients with mobility issues. Through social learning and group support, group CBT alleviates feelings of loneliness and emotional isolation, thereby promoting psychological recovery. The study also suggests providing CBT training for healthcare providers to enhance their therapeutic skills and discusses ways to promote the widespread adoption of mobile-based CBT for broader patient accessibility.

Future research should focus on exploring the impact of cancer type and treatment stage on psychological resilience outcomes. Different types of cancer present unique psychological challenges; therefore, personalized CBT interventions may have varying effects. Furthermore, different stages of treatment (e.g., early treatment vs. recovery) may influence patients’ psychological needs and responses to CBT. Thus, future research should evaluate how the effectiveness of CBT changes across stages to identify the optimal intervention timing. Furthermore, future studies should also consider the potential impact of cancer treatment modalities (e.g., chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy) on CBT outcomes. Cross-cultural research will help to reveal how cancer patients’ psychological resilience outcomes vary in different cultural contexts, thus advancing global cancer mental health intervention strategies.

Limitations

This study has several limitations that may affect the interpretability and generalizability of the results. First, the included studies were heterogenous in terms of clinical characteristics and methodology, including variations in treatment stages, intervention timing, and intensity. This heterogeneity led to diverse outcomes. Additionally, the use of different psychological resilience measurement tools increased clinical heterogeneity, and despite the use of subgroup analysis, substantial variability was observed within each subgroup, thus indicating the potential influence of unidentified variables. Second, this study only included Chinese- and English-language literature, which may have introduced language bias and limited the global applicability of the results. Future research should expand the literature search to include studies in other languages and utilize statistical methods such as Begg's test or Egger's test to assess the risk of publication bias. Finally, the exclusion of certain CTs due to a lack of raw data or differences in study design could have impacted the findings. Future studies should aim to include more raw data and minimize exclusions to improve the representativeness of the results. In conclusion, while this study offers valuable insights into psychological resilience interventions for cancer patients, further methodological improvements are needed to control for heterogeneity and bias, thereby enhancing the reliability and generalizability of the findings.

Conclusion

This study is the first comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of CBT on resilience among cancer patients. Thirteen studies were included, and the results revealed that CBT had a significant and substantial effect on resilience. Future studies should further investigate the CBT intervention model aimed at enhancing resilience. These studies should also explore the impact of various intervention delivery methods, session frequencies, and formats on resilience. Additionally, future studies should examine how theories related to psychological resilience can be used to optimize the effectiveness of CBT interventions.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the participants who helped us with this project.

Abbreviation

- CBT

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Authors’ contributions

Lina Xiang: Responsible for the literature search, screening, quality assessment, data analysis, and drafting of the manuscript. Yu Zhu: Contributed to the literature search, screening, quality assessment, data analysis, and drafting of the manuscript. Hongwei Wan: Oversaw the study design, conducted quality assessment, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Funding

Shanghai Shenkang Hospital Development Center Municipal Hospital Diagnosis and Treatment Technology Promotion and Optimization Management Project (SHDC12022620); Shanghai Pudong New Area Science and Technology Commission Project (PKJ2024-Y56). Research Project in Nursing at Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine for the Year 2024 (grant number: Jyhz 2401). The 2024 Shanghai Mental Health Center "Qihang" Talent Program (No.: 2024-QH-01).

Data availability

The data are provided within the manuscript and supplementary information files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Lina Xiang and Yu Zhu should be considered joint first authors.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49. 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Pitman A, Suleman S, Hyde N, Hodgkiss A. Depression and anxiety in patients with cancer. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2018;361:k1415. 10.1136/bmj.k1415. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Hsu FC, Hsu CH, Chung CH, Pu TW, Chang PK, Lin TC, Jao SW, Chen CY, Chien WC, Hu JM. The Combination of Sleep Disorders and Depression Significantly Increases Cancer Risk: A Nationwide Large-Scale Population-Based Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(15):9266. 10.3390/ijerph19159266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Hart NH, Crawford-Williams F, Crichton M, Yee J, Smith TJ, Koczwara B, Fitch MI, Crawford GB, Mukhopadhyay S, Mahony J, Cheah C, Townsend J, Cook O, Agar MR, Chan RJ. Unmet supportive care needs of people with advanced cancer and their caregivers: a systematic scoping review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2022;176: 103728. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2022.103728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Opsomer S, De Lepeleire J, Lauwerier E, Pype P. Resilience in advanced cancer caregiving. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70(suppl 1):bjgp20X711041. 10.3399/bjgp20X711041. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Lai MC, Szatmari P. Resilience in autism: Research and practice prospects. Autism. 2019;23(3):539–41. 10.1177/1362361319842964. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Gao Y, Yuan L, Pan B, Wang L. Resilience and associated factors among Chinese patients diagnosed with oral cancer. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):447. 10.1186/s12885-019-5679-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Tamura S, Suzuki K, Ito Y, Fukawa A. Factors related to the resilience and mental health of adult cancer patients: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(7):3471-86. 10.1007/s00520-020-05943-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Eaton S, Cornwell H, Hamilton-Giachritsis C, Fairchild G. Resilience and young people's brain structure, function and connectivity: A systematic review. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 2021;132:936–56. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Zhang X, Lu J, Ding Z, Zhong G, Qiao Y, Li X, Cui H. Psychological resilience and post-traumatic stress disorder as chain mediators between personality traits and cognitive functioning in patients with breast cancer. BMC Psychiatry. 2024;24(1):750. 10.1186/s12888-024-06219-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seiler A, Jenewein J. Resilience in Cancer Patients. Frontiers in psychiatry. 2018;10:208. 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Ding X, Zhao F, Wang Q, Zhu M, Kan H, Fu E, Wei S, Li Z. Effects of interventions for enhancing resilience in cancer patients: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2024;108: 102381. 10.1016/j.cpr.2024.102381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenberg AR, Bradford MC, Junkins CC, Taylor M, Zhou C, Sherr N, Kross E, Curtis JR, Yi-Frazier JP. Effect of the promoting resilience in stress management intervention for parents of children with cancer (PRISM-P): a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(9): e1911578. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.11578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salsman JM, Rosenberg AR. Fostering resilience in adolescence and young adulthood: considerations for evidence-based, patient-centered oncology care. Cancer. 2024;130(7):1031–40. 10.1002/cncr.35182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joyce S, Shand F, Bryant RA, Lal TJ, Harvey SB. Mindfulness-Based Resilience Training in the Workplace: Pilot Study of the Internet-Based Resilience@Work (RAW) Mindfulness Program. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(9):e10326. 10.2196/10326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Carson AJ, McWhirter L. Cognitive behavioral therapy: principles science and patient selection in neurology. Abstr Semin Neurol. 2022;42(02):114–22. 10.1055/s-0042-1750851. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Ludolph P, Kunzler AM, Stoffers-Winterling J, Helmreich I, Lieb K. Interventions to Promote Resilience in Cancer Patients. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2019;51-52(51-52):865–72. 10.3238/arztebl.2019.0865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Ma Y, Hall DL, Ngo LH, Liu Q, Bain PA, Yeh GY. Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2021;55: 101376. 10.1016/j.smrv.2020.101376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galante J, Dufour G, Vainre M, Wagner AP, Stochl J, Benton A, Lathia N, Howarth E, Jones PB. A mindfulness-based intervention to increase resilience to stress in university students (the mindful student study): a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Public Health. 2018;3(2):e72–81. 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30231-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng P, Kalmbach DA, Hsieh H-F, Castelan AC, Sagong C, Drake CL. Improved resilience following digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia protects against insomnia and depression one year later. Psychol Med. 2023;53(9):3826–36. 10.1017/S0033291722000472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed). 1996;312(7023):71–2. 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savovic J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JAC, Cochrane Bias Methods Group, Cochrane Statistical Methods Group. The Cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed). 2011;343:d5928. 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Egger M, Smith GD, Phillips AN. Meta-analysis: principles and procedures. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed). 1997;315(7121):1533–7. 10.1136/bmj.315.7121.1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larry V. Hedges and Ingram Olkin. Statistical Methods for Meta-Analysis. Academic Press; 1985.

- 26.Wu K. The impact of a cognitive-behavioral intervention model on fatigue levels and psychological resilience in cancer chemotherapy patients. Primary Care Medicine Forum. 2020;34(24):4963–4. 10.19435/j.1672-1721.2020.34.041. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou K, Li J, Li X. Effects of cyclic adjustment training delivered via a mobile device on psychological resilience, depression, and anxiety in Chinese post-surgical breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;178(1):95–103. 10.1007/s10549-019-05368-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin C, Diao Y, Dong Z, Song J, Bao C. The effect of attention and interpretation therapy on psychological resilience, cancer-related fatigue, and negative emotions of patients after colon cancer surgery. Ann Palliat Med. 2020;9(5):3261–70. 10.21037/apm-20-1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang J, Xu X, Wang Z, Jiang S. The effects of cognitive bias modification for attention and interpretation on the postoperative psychological resilience and quality of life of patients with pituitary adenoma: a randomized trial. Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10(5):5729–37. 10.21037/apm-21-782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lei Y, Zhou L, Xu N, Meng X, Deng Q. Effect of Individualized Cognitive Behavior Intervention on Resilience and Self-Efficacy of Patients with Chemotherapy after Prostate Cancer Operation. Anti-Tumor Pharmacy. 2019;9(3):522–26. 10.3969/j.issn.2095-1264.

- 31.Loprinzi CE, Prasad K, Schroeder DR, Sood A. Stress management and resilience training (SMART) program to decrease stress and enhance resilience among breast cancer survivors: a pilot randomized clinical trial. Clin Breast Cancer. 2011;11(6):364–8. 10.1016/j.clbc.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Y, Tang R, Bi L, Wang D, Li X, Gu F, Han J, Shi M. Effects of family-centered positive psychological intervention on psychological health and quality of life in patients with breast cancer and their caregivers. Support Care Cancer. 2023;31(10):592. 10.1007/s00520-023-08053-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang W, Wang Z, Chen X. Impacts of cognitive behavioral intervention on anxiety, depression and resilience of patients with malignant glioblastoma. China Modern Doctor. 2021;59(17):167–70. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang N, Xie X, Liu C, Li G. Effect of cognitive-behavioral intervention on psychological resilience and quality of life for patients with malignant lymphoma. Oncology Progress. 2021;19(12):1276–9+1283. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Q. The impact of cognitive-behavioral interventions on hope levels and psychological resilience in patients undergoing esophageal cancer surgery. Chinese Greneral Practice Nursing. 2018;16(12):1488–90. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang J. Effect of cognitive behavioral group therapy on patients with differentiated thyroid cancer. Chinese Medical Digest: Otorhinolaryngology. 2022;1(37):179–82. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Faghani F, Choobforoushzadeh A, Sharbafchi MR, Poursheikhali H. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based supportive psychotherapy on posttraumatic growth, resilience, and self-compassion in cancer patients: a pilot study. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2022. 10.1007/s00508-022-02057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Orwin RG. A Fail-Safe N for Effect Size in Meta-Analysis. Journal of Educational Statistics. 1983;8(2):157–9. 10.2307/1164923.

- 39.Lau N, Bradford MC, Steineck A, Scott S, Bona K, Yi-Frazier JP, McCauley E, Rosenberg AR. Examining key sociodemographic characteristics of adolescents and young adults with cancer: A post hoc analysis of the Promoting Resilience in Stress Management randomized clinical trial. Palliative medicine. 2020;34(3):336–48. 10.1177/0269216319886215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Keller M, Sommerfeldt S, Fischer C, Knight L, Riesbeck M, Löwe B, Herfarth C, Lehnert T. Recognition of distress and psychiatric morbidity in cancer patients: a multi-method approach. Annals of Oncology: Official Journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology. 2004;15(8):1243–9. 10.1093/annonc/mdh318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Henrich D, Glombiewski JA, Scholten S. Systematic review of training in cognitive-behavioral therapy: summarizing effects, costs and techniques. Clin Psychol Rev. 2023;101: 102266. 10.1016/j.cpr.2023.102266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Akechi T, Yamaguchi T, Uchida M, Imai F, Momino K, Katsuki F, Sakurai N, Miyaji T, Mashiko T, Horikoshi M, Furukawa TA, Yoshimura A, Ohno S, Uehiro N, Higaki K, Hasegawa Y, Akahane K, Uchitomi Y, Iwata H. Smartphone psychotherapy reduces fear of cancer recurrence among breast cancer survivors: a fully decentralized randomized controlled clinical trial (J-SUPPORT 1703 study). J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(5):1069–78. 10.1200/JCO.22.00699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sauer C, Zschäbitz S, Krauss J, Walle T, Haag GM, Jäger D, Hiller K, Bugaj TJ, Friederich HC, Maatouk I. Electronic health intervention to manage symptoms of immunotherapy in patients with cancer (SOFIA): results from a randomized controlled pilot trial. Cancer. 2024;130(14):2503–14. 10.1002/cncr.35300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clark MM, Bostwick JM, Rummans TA. Group and individual treatment strategies for distress in cancer patients. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78(12):1538–43. 10.4065/78.12.1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chirico A, Palombi T, Alivernini F, Lucidi F, Merluzzi TV. Emotional distress symptoms, coping efficacy, and social support: a network analysis of distress and resources in persons with cancer. Ann Behav Medicine: A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine. 2024;58(10):679–91. 10.1093/abm/kaae025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rogers SN, Tsai HH, Cherry MG, Patterson JM, Semple CJ. Experiences and needs of carers of patients with head and neck cancer: a systematic review. Psychooncology. 2024;33(10):e9308. 10.1002/pon.9308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data are provided within the manuscript and supplementary information files.