Abstract

Pathophysiology and outcomes after traumatic brain injury (TBI) are complex and heterogeneous. Current classifications are uninformative about pathophysiology. Proteomic approaches with fluid-based biomarkers are ideal for exploring complex disease mechanisms, because they enable sensitive assessment of an expansive range of processes potentially relevant to TBI pathophysiology. We used novel high-dimensional, multiplex proteomic assays to assess altered plasma protein expression in acute TBI.

We analysed samples from 88 participants from the BIO-AX-TBI cohort [n = 38 moderate–severe TBI (Mayo Criteria), n = 22 non-TBI trauma and n = 28 non-injured controls] on two platforms: Alamar NULISA™ CNS Diseases and OLINK® Target 96 Inflammation. Patient participants were enrolled after hospital admission, and samples were taken at a single time point ≤10 days post-injury. Participants also had neurofilament light, GFAP, total tau, UCH-L1 (all Simoa®) and S100B (Millipore) data. The Alamar panel assesses 120 proteins, most of which were previously unexplored in TBI, plus proteins with known TBI specificity, such as GFAP. A subset (n = 29 TBI and n = 24 non-injured controls) also had subacute (10 days to 6 weeks post-injury) 3 T MRI measures of lesion volume and white matter injury (fractional anisotropy).

Differential expression analysis identified 16 proteins with TBI-specific significantly different plasma expression. These were neuronal markers (calbindin 2, UCH-L1 and visinin-like protein 1), astroglial markers (S100B and GFAP), neurodegenerative disease proteins (total tau, pTau231, PSEN1, amyloid-beta-42 and 14-3-3γ), inflammatory cytokines (IL16, CCL2 and ficolin 2) and cell signalling- (SFRP1), cell metabolism- (MDH1) and autophagy-related (sequestome 1) proteins. Acute plasma levels of UCH-L1, PSEN1, total tau and pTau231 were correlated with subacute lesion volume. Sequestome 1 was positively correlated with white matter fractional anisotropy, whereas CCL2 was inversely correlated. Neuronal, astroglial, tau and neurodegenerative proteins were correlated with each other, IL16, MDH1 and sequestome 1. Exploratory clustering (k means) by acute protein expression identified three TBI subgroups that differed in injury patterns, but not in age or outcome. One TBI cluster had significantly lower white matter fractional anisotropy than control-predominant clusters but had significantly lower lesion subacute lesion volumes than another TBI cluster. Proteins that overlapped on two platforms had excellent (r > 0.8) correlations between values.

We identified TBI-specific changes in acute plasma levels of proteins involved in neurodegenerative disease, inflammatory and cellular processes. These changes were related to patterns of injury, thus demonstrating that processes previously studied only in animal models are also relevant in human TBI pathophysiology. Our study highlights how proteomic approaches might improve classification and understanding of TBI pathophysiology, with implications for prognostication and treatment development.

Keywords: inflammation, biomarker, neuroimaging, neurodegeneration

Using proteomic assays, Li et al. identified changes in plasma levels of proteins involved in neurodegenerative disease and inflammation in the days following traumatic brain injury. Different patterns of plasma proteins were associated with distinct brain injury patterns on neuroimaging, suggesting potential for classifying TBI.

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a highly heterogeneous condition, encompassing multiple possible mechanisms and sequelae.1 Current, overly simplistic classifications inadequately describe the range of processes occurring during and after TBI.2 This limits clinical prognostication, in addition to patient selection for and evaluation of potential treatments. The TBI field is increasingly moving towards neuroimaging and fluid biomarker-led phenotyping that can inform about post-injury pathophysiological processes and be clinically relevant. Early post-TBI blood levels of neuronal and astroglial markers (e.g. NFL and GFAP) and cytokines (e.g. IL6) reflect injury and are associated with later neuronal loss and functional outcomes.3-5 However, only a small number, likely to be from many interacting pathophysiological processes that accompany or are triggered by TBI, have been studied.

Highly sensitive, high-dimensional protein assays are now available to assess a range of proteins using small sample volumes. These novel antibody-based proteomic technologies, namely the OLINK® Proximity Extension6 and the Alamar NUcleic acid Linked Immuno-Sandwich Assay (NULISA™)7 technologies, combine the sensitivity and specificity of immunoassay with the ability to detect a large breadth of targets.8 This makes them ideal for discovery work, characterizing disease mechanisms and identifying potential targets for intervention. This approach is particularly advantageous in conditions such as TBI, where a broad and complex range of processes contribute to heterogeneous downstream effects.

In this study, we used the Alamar NULISA™ CNS diseases panel for the first time in a clinical TBI cohort to investigate the plasma proteomic response in acute TBI compared with non-TBI trauma (NTT) and non-injured controls (CON). This panel assesses 120 proteins, most of which have not been investigated before in human TBI. These include phosphorylated tau species and neurodegenerative markers, such as amyloid-beta-42, cytokines and proteins important for peripheral immune cell infiltration and neuroinflammation, such as IL16, and proteins involved in cellular processes. This enables a single experiment to investigate whether processes previously identified to be important in animal TBI models, such as autophagy9 and neuroinflammatory signalling,10 are also relevant in human TBI pathophysiology. It also includes proteins, such as GFAP and NFL, which we have previously shown to differentiate TBI from healthy and non-TBI trauma.3

Samples tested were collected as part of the BIO-AX-TBI study,11 a longitudinal TBI cohort study that also collected other measures. This enabled us to investigate whether acute patterns of protein expression were related to subacute white matter injury and lesion volume. Furthermore, we explored the extent to which acute patterns of plasma protein expression could differentiate clinically meaningful TBI subgroups, given that pathophysiological heterogeneity in TBI is a major challenge for prognostication and developing effective interventions.1 Explicit inclusion of an NTT group allowed us to identify patterns of plasma protein expression that differentiate TBI from injury in general. For example, a previous proteomic study identified post-TBI altered blood and CSF levels of many neuroinflammatory and structural proteins,12 but it is uncertain whether all changes are TBI specific. We additionally tested our cohorts on the OLINK Target 96 Inflammation panel, which assesses 92 inflammation-related proteins, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)-based platforms to assess key neuronal and astroglial markers. The overlapping targets enabled us to cross-validate our findings, an important step for identifying robust protein markers for future clinical studies.

Our hypotheses are as follows: (i) neuronal and astroglial markers and proteins associated with neurodegenerative disease increase after TBI, whereas acute phase and inflammatory proteins increase after both TBI and non-TBI trauma; (ii) proteins specifically increasing after TBI will be correlated with injury measures from subacute MRI; and (iii) proteomic expression can identify clinically meaningful subgroups within TBI.

Materials and methods

Participant cohort

We analysed plasma samples from n = 38 TBI [33 male and 5 female, mean age 43.8 years, standard deviation (SD) 16.8], n = 22 non-TBI trauma (NTT; 20 male and 2 female, mean age 44.2 years, SD 17.7) and n = 28 non-injured healthy (CON; 20 male and 8 female, mean age 36.2 years, SD 16.2) participants (Table 1). These samples are from a subgroup of participants in the BIO-AX-TBI study,11 a longitudinal study of adult (aged 18–80 years) moderate–severe TBI (defined by the Mayo Criteria13). TBI and NTT participants were enrolled after hospital admission. Further inclusion/exclusion criteria and injury mechanisms are detailed in the Supplementary material. TBI patients mostly presented with bilaterally reactive pupils (29 of 35 patients) and a CT Marshall grade of II (20 of 38 patients) (midline shift <5 mm with visible basal cisterns, and no high- or mixed-density lesions >25 cm3) and had a mean hospital stay of 39.3 days (SD 30.1) (Fig. 1). We assessed functional outcome after TBI with the Glasgow Outcome Scale-Extended (GOS-E) at 6 and 12 months.14 Twelve of 38 patients had pre-injury comorbidities, including hypertension, non-insulin-dependent type II diabetes, arrhythmia and prior alcohol misuse (for full comorbidity list, see Supplementary Table 1). Twenty of 38 patients had additional extracranial injury, most commonly polytrauma (Table 1). The most common injury in the NTT cohort was fractures (Fig. 1E). All participants provided written informed consent, and the local ethics board granted ethical approval (IRAS no. 230221).

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic information

| Parameter | Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CON (non-injured, healthy) | NTT (non-TBI trauma) | TBI (traumatic brain injury) | |

| n (male/female) | 28 (20/8) | 22 (20/2) | 38 (33/5) |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 36.2 (16.2) | 44.2 (17.7) | 43.8 (16.8) |

| Sample collection time, day after injury, median (IQR) | n/a | 2 (2–3.75) | 1 (1–2) |

| Admission GCS: | n/a | n/a | – |

| 14–15 | – | – | 6 |

| 9–13 | – | – | 13 |

| 3–8 | – | – | 19 |

| Admission pupils: | n/a | n/a | – |

| Bilaterally reactive | – | – | 29 |

| Unilateral dilated and NR | – | – | 6 |

| Bilaterally dilated and NR | – | – | 0 |

| Unknown | – | – | 3 |

| Marshall CT gradea: | n/a | n/a | – |

| Diffuse injury I | – | – | 2 |

| Diffuse injury II | – | – | 20 |

| Diffuse injury III | – | – | 4 |

| Diffuse injury IV | – | – | 0 |

| EML V | – | – | 0 |

| NEML VI | – | – | 12 |

| Extracranial injury type | n/a | – | – |

| Polytrauma | – | 6 | 12 |

| Chestb | – | 3 | 4 |

| Abdominal/pelvicb | – | 0 | 0 |

| Spine | – | 0 | 2 |

| Fracture(s) | – | 11 | 2 |

| Vascular | – | 2 | 0 |

| Mortality (days after injury) | n/a | 0 | 1 (51) |

| GOS-E (6 months): | n/a | n/a | – |

| Dead (1) | – | – | 1 |

| VS (2) | – | – | 2 |

| LSD (3) | – | – | 7 |

| USD (4) | – | – | 3 |

| LMD (5) | – | – | 7 |

| UMD (6) | – | – | 5 |

| LGR (7) | – | – | 6 |

| UGR (8) | – | – | 3 |

| Lost to follow-up | – | – | 4 |

| GOS-E (12 months): | n/a | n/a | – |

| Dead (1) | – | – | 1 |

| VS (2) | – | – | 2 |

| LSD (3) | – | – | 4 |

| USD (4) | – | – | 3 |

| LMD (5) | – | – | 2 |

| UMD (6) | – | – | 7 |

| LGR (7) | – | – | 7 |

| UGR (8) | – | – | 3 |

| Lost to follow-up | – | – | 9 |

EML = evacuated mass lesion; GCS = Glasgow Coma Scale; GOS-E = Glasgow Outcome Scale Extended; LGR = lower good recovery; LMD = lower moderate disability; LSD = lower severe disability; n/a = not applicable; NEML = non-evacuated mass lesion; NR = non-reactive; UGR = upper good recovery; UMD = upper moderate disability; USD = upper severe disability; VS = vegetative state.

aOn initial CT.

bIndicates injury of chest or abdominal or pelvic organs; isolated rib or pelvic fractures with no underlying organ damage was classified under Fractures.

Figure 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of cohorts. (A) Age and sex distribution of the cohorts. (B) Duration of hospital stay (in days) by age for the traumatic brain injury (TBI) cohort. (C) Distribution of clinical descriptors of injury severity [pupil reactivity (BDNR = bilaterally dilated and non-reactive; BR = bilaterally reactive; UDNR = unilaterally dilated and non-reactive), CT Marshall grade and pre-hospital Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS)] within the TBI cohort. (D) Distribution of functional outcome, assessed by Glasgow Outcome Scale Extended (GOS-E) at 6 months (6m) and 12 months (12m) after TBI. (E) Distribution of injury type within the non-TBI trauma (NTT) cohort.

MRI acquisition and analysis

Thirty-six TBI (31 male and 5 female, mean age 43.2 years, SD 17.0) and n = 24 CON (20 male and 4 female, mean age 35.5 years, SD 16.3) participants had subacute 3 T MRI scans (10 days to 6 weeks post-TBI, to allow for the practicalities of acquiring MRI in critically unwell patients). We included lesion volumes and measures of white matter injury in this analysis. MRI was acquired, preprocessed and analysed for the BIO-AX-TBI study (for protocol details, see Graham et al.3,11). In brief, lesion volume was calculated from manually drawn lesion masks, using T1-weighted and T2 fluid attenuated inversion recovery scans, and volumes extracted from the masks with fslstats from the FMRIB Software Library (FSL) imaging analysis software package.15 K.Z., F.M. and N.G. carried out manual lesion segmentation, working together on a small subset to ensure consistency of approach, before working independently. N.G. is a neurologist, and all are experienced neuroimaging researchers. Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) was available for 29 TBI (25 male and 4 female, mean age 43.1 years, SD 17.1) and all CON participants. Two TBI patients could not have a subacute MRI owing to practical difficulties, one patient did not tolerate the whole scan so did not have DTI, and diffusion data for six patients were not usable owing to poor data quality or artefacts. White matter injury was assessed with z-scored mean fractional anisotropy (FA) across the whole skeletonized white matter after registration of diffusion scans to Diffusion Tensor Imaging Toolkit space16 and using a tract-based spatial statistics approach to generate voxelwise maps of FA. The z-scores were calculated by comparing values from patients and controls scanned on the same scanner. Mean z-scored FA was extracted for the corpus callosum and whole white matter skeleton. Voxelwise analysis was conducted using the general linear model with non-parametric permutation testing (10 000) in FSL Randomise,17 with age and sex included as nuisance covariates in cross-sectional analyses and individualized lesion masking. Voxelwise analysis of FA z-score was cluster-corrected using threshold-free cluster enhancement, with multiple-comparison correction using a family-wise error rate of P < 0.05.

Blood sample processing

Eighty-eight plasma samples (n = 38 TBI, n = 22 NTT and n = 28 CON) were processed on the OLINK® Target 96 Inflammation panel, and 86 plasma samples [n = 38 TBI, n = 22 NTT and n = 26 CON (20 male and 6 female, mean age 36 years, SD 16.2)] processed on the Alamar NULISA™ CNS Diseases panel. Samples were from the first acute time point (≤10 days after injury) in the BIO-AX-TBI study.3 The median sample collection time was 1 day after injury for the TBI cohort [interquartile range (IQR) 1–2 days] and 2 days after injury for the NTT cohort (IQR 2–3.75 days). A breakdown of sampling time points is in Supplementary Fig. 1. Samples were taken immediately to the laboratory after collection for processing and freezing at −80°C. Other simultaneously acquired plasma samples had previously been analysed for GFAP, total tau, NFL and UCH-L1 (Simoa®-HD1 platform) and S100B (Millipore ELISA).3 For this study, we could test only a subset (one plate’s worth) of plasma samples from the BIO-AX-TBI study. To achieve roughly balanced groups, we tested all available samples from the NTT cohort plus a subset from the CON and TBI cohorts. The CON and TBI samples were selected randomly, after screening out those participants who had high or low outlier GFAP values (defined as outside 3 SD of the mean GFAP value for that cohort) on the Simoa®-HD1 platform assay (full details are given in Supplementary Fig. 2). The selected samples were randomized with the RAND function in Excel, then plated in ascending well order onto a single plate each of the OLINK® Target 96 Inflammation panel18 and the Alamar Biotech NULISA™ CNS Diseases panel (Supplementary Table 2). The Alamar NULISA™ CNS Diseases panel was chosen for its breadth of proteins, covering multiple pathways implicated in neurological disease, including proteins known to be important TBI markers (e.g. GFAP and NFL). This provided the opportunity to explore many potential pathophysiological pathways using a small amount of sample in a single experiment. The OLINK® Target 96 Inflammation panel, which assesses 92 proteins implicated in inflammatory and immune pathways, was used because it aligns with another ongoing study, and also several proteins overlap with the Alamar NULISA™ CNS Diseases panel, enabling cross-validation of several proteins with one assay.

Alamar NULISA™ profiling

Samples used had been through one previous freeze–thaw cycle. Relative protein concentrations were measured by Alamar Biosciences on the NULISA™ CNS disease panel. The Alamar NULISA™ immunoassays use differential conjugation of a pair of capture and detection antibodies of each target.19 Both antibodies are conjugated with part of a ‘barcode’ sequence specific to the target. In addition, one of the antibodies is conjugated to partly double-stranded DNA with a poly-A-containing oligonucleotide, whereas the other contains a biotin-containing oligonucleotide. Sequential capture–release of the antibody/antigen and antibody/antigen/antibody complexes offers increased sensitivity, allowing a final amplification of the ‘barcode’ sequence for each target, which is then quantified using next generation sequencing. The assay is fully automated. Normalization takes place against both an internal control and an inter-plate control.

OLINK® protein profiling

Samples used had never been defrosted previously. We used the Target 96 Inflammation panel OLINK Signature Q100 platform (OLINK Proteomics AB). The OLINK immunoassays are based on the proximity extension assay (PEA) technology,6 which uses a pair of antibodies per marker detected, labelled with oligonucleotides that are incubated with 1 μl of sample. When both antibodies of a pair bind on the target, the oligonucleotides bind to each other, allowing a PCR to take place, the products of which are then detected and quantified by quantitative PCR.

Biomarker data for both Alamar and OLINK® assays are not absolute quantification data, but are given as a normalized protein expression (NPX) value for the OLINK® panel and as NULISA protein quantification (NPQ) units for the Alamar panel. Both NPQ and NPX are arbitrary units on a log2 scale, with the data being to minimize variation.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in R (v.4.3.2), using RStudio (2021).

We carried out DE analysis on the Alamar panel data to identify proteins whose plasma levels are affected by TBI. DE is a statistical approach to detect and identify, on a wide scale, biological markers whose expression varies between different groups. We used the limma package from Bioconductor, which uses a moderated t-test. False discovery rate correction (the Benjamini–Hochberg method) was done for multiple comparisons across all 120 proteins assayed.

Spearman correlation was used to assess correlations between blood biomarker levels identified by DE analysis, and between MRI measures of injury and those blood biomarker levels. False discovery rate correction was done to account for the number of correlations performed.

To investigate whether plasma protein levels could identify subgroups with TBI, we performed exploratory k means clustering analysis using the fmsb package. We iterated from 1 to 10 k clusters, with 25 random starting assignments. A model was built based on the k (k = 5) that was identified as the ‘elbow’ of the scree plot of within-cluster sum of squares value, with 50 random starting assignments. Difference in age and neuroimaging measures (lesion volume, whole skeleton and corpus callosum FA) between clusters was interrogated using ANOVA, with cluster assignment as a factor, and Tukey’s post hoc HSD tests for significant ANOVA tests. We used χ2 tests to test whether the proportions of each GOS-E outcome category at 6 and 12 months was different between clusters. Bonferroni correction was used for multiple comparisons correction, such that the ANOVA or χ2 test was deemed significant with a critical P-value of 0.0083 (0.05/6). No adjustment was made for sampling time, extracranial and secondary injury, systemic complications or premorbid conditions.

Cross-validation analyses

Pearson correlations were used to determine the relationship between proteins that overlapped on different assays approaches. One-way ANOVA tests (with participant type as factor) were performed for overlapping proteins using values from both available assays, to assess whether both types of assays would return the same conclusion about the main effect of cohort on protein expression.

Results

Differential expression analyses identify TBI-specific derangements in plasma protein expression

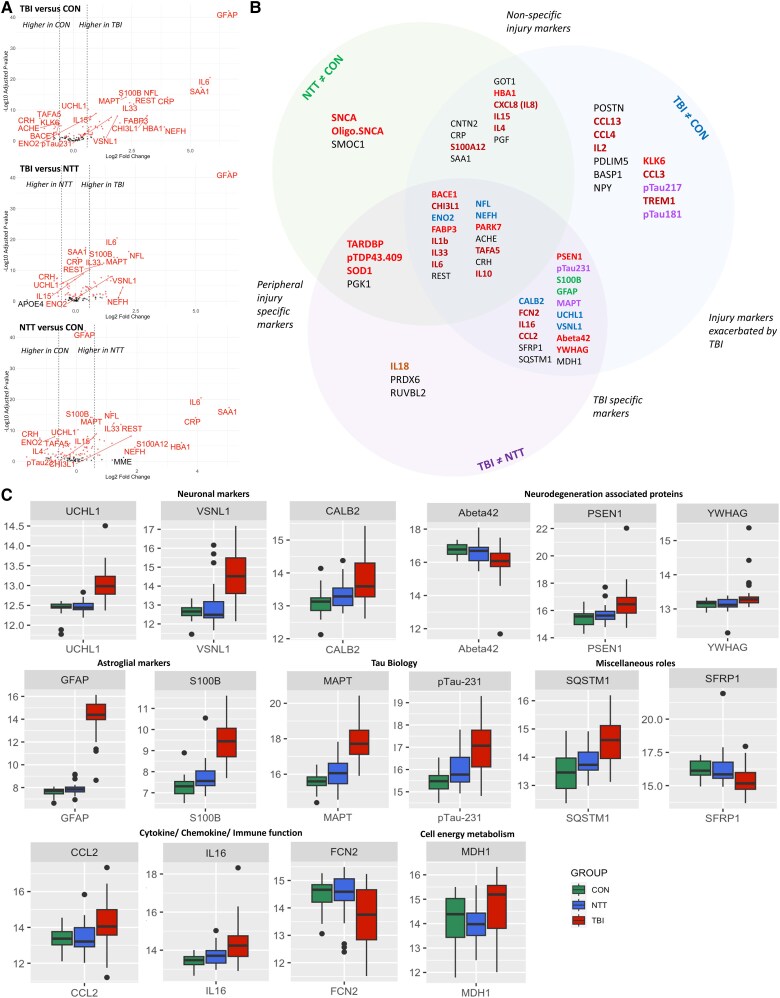

Differential expression analysis of the Alamar NULISA™ CNS Diseases panel identified 71 proteins whose plasma levels differed significantly between non-injured control (CON), non-TBI injury (NTT) and TBI injury groups (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Table 3). The volcano plots demonstrate how plasma expression of proteins differed between each pair of groups (Fig. 2A), with the Venn diagram (Fig. 2B) summarizing whether proteins were differentially expressed between TBI and CON only or also between TBI and NTT (Fig. 2B). Sixteen proteins had different plasma levels compared with both NTT and CON cohorts, indicating TBI-specific pathophysiology (Fig. 2A, top and middle, B and C). As expected, these included neuronal [ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase 1 (UCH-L1)], astroglial [glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and S100 calcium binding protein B (S100B)] and total tau (MAPT) proteins, all of which have previously been shown to be increased after TBI compared with CON and NTT.3 We additionally showed that changes in plasma levels of phosphorylated Tau 231 (pTau231) and amyloid-beta-42 (Abeta42), which have previously been seen in comparison to non-injured controls,20 are specific to TBI and not seen in NTT (Fig. 2C). Newly demonstrated TBI-specific changes included deranged plasma levels of neuronal proteins [visinin-like protein 1 (VSNL1) and calbindin1 (CALB1)], proteins associated with neurodegenerative disease [presenilin 1 (PSEN1) and 14-3-3γ (YWHAG)], inflammatory signalling proteins [ficolin 2 (FCN2)] and proteins involved in cell signalling [secreted frizzle-like protein1 (SFRP1)], cell metabolism [malate dehydrogenase 1 (MDH1)] and autophagy [sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1)]. Although most proteins had significantly raised levels in acute TBI, levels of FCN2, Abeta42 and SFRP1 were significantly lower in TBI than in CON and NTT cohorts (Fig. 2B and C).

Figure 2.

Differential expression analysis identifying traumatic brain injury-specific changes in plasma proteins. (A) Volcano plots showing the differences in plasma protein expression between each pair of groups. Red dots denote significant proteins. (B) Schematic diagram of the categorization of proteins with significant group differences (adjusted P < 0.05). Proteins are categorized based on a between-group comparison coefficient log2 > 0.58 (equivalent to >1.5× difference between the two groups) and post hoc t-test P < 0.05. Protein names are colour-coded based on biological role/pathway: red = neurodegenerative disease associated; blue = neuronal marker; orange = cytokine/chemokine; purple = tau pathology; green = astroglial marker. Black indicates a range of other roles and pathways (Supplementary Table 2). Nine proteins for which between-group comparison did not meet these criteria for any of the group pairs [traumatic brain injury (TBI) versus control (CON), TBI versus non-TBI trauma (NTT) and NTT versus CON] are not included in the schematic diagram. (C) Boxplots illustrating plasma protein levels in CON, NTT and TBI groups for proteins identified by differential expression analysis to be TBI specific. The y-axis units are NULISA protein quantification (NPQ) units.

Several proteins were raised in both NTT and TBI groups, but more so after TBI, suggesting their involvement in the pathophysiology of general injury, which is exacerbated by TBI (Fig. 2B and C and Supplementary Fig. 3). These included pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL1b, IL33 and IL6), anti-inflammatory cytokines and proteins [IL10 and chitinase-3-like 1 (CHI3L1)], in addition to neuronal proteins [neurofilament light (NEFL) and enolase 2 (ENO2)]. Non-specific injury markers, i.e. proteins with increased plasma levels in the NTT group with no additional effect of TBI, included acute phase proteins [C-reactive protein (CRP) and serum amyloid A1 (SAA1)] and inflammatory proteins (e.g. IL8) (Fig. 2A, bottom and Supplementary Fig. 3).

Correlations between acute levels of TBI-specific proteins and subacute MRI findings

Diffusion tensor imaging was used to quantify white matter injury. Compared with the CON cohort, the TBI cohort had significantly reduced white matter FA z-scores across both the whole skeletonized white matter tract and the corpus callosum in the subacute setting (10 days to 6 weeks after TBI), indicative of white matter injury (Fig. 3A). Tract-based spatial statistics analysis also showed significant reductions in FA in several white matter tracts (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, there was an inverse relationship between acute plasma levels of the cytokine CCL2 and corpus callosum FA z-scores (rs = −0.60, P = 0.0006) and a positive relationship between acute levels of the autophagy-related protein SQSTM1 and whole skeleton FA z-scores (rs = 0.5, P = 0.0054).

Figure 3.

Relationship between plasma proteins and neuroimaging features. (A) Comparison of mean fractional anisotropy (FA) z-scores of the whole skeleton and corpus callosum between non-injured healthy controls (CON) and traumatic brain injury (TBI) patients on subacute MRI (10 days to 6 weeks post-injury). *Adjusted P < 0.05. (B) Voxelwise comparison of z-scored mean FA in patients compared with controls on subacute MRI (10 days to 6 weeks post-injury), with significant (P < 0.05) group differences in red, overlaid on the white matter skeleton in green. Results are overlaid on a 1 mm standard brain in Diffusion tensor imaging toolkit space. (C) Correlation matrix of TBI-specific proteins (identified by differential expression analysis) with lesion volume, z-score of the whole skeleton FA (z_wholeskel_FA) and z-score of the corpus callosum (z_CC_FA) on subacute MRI (10 days to 6 weeks post-injury) within the TBI cohort. Proteins are ordered by category. See Supplementary Table 2 for category. Only statistically significant results (false discovery rate adjusted P < 0.05) are shown.

Thirty-two TBI patients had evidence of focal lesions (mean volume = 22 198.55 mm3, range = 352.00–82 147.05 mm3). Subacute lesion volume was positively correlated with acute plasma levels of the neuronal marker UCH-L1 (rs = 0.64, P < 0.0001), the amyloid cleavage enzyme PSEN1 (rs = 0.53, P = 0.0012), total tau (MAPT) (rs = 0.61, P < 0.0001) and phosphorylated tau isoform pTau231 (rs = 0.62, P < 0.0001), indicating a potential relationship with the extent of focal injury (Fig. 3C).

Correlations between acute levels of TBI-specific proteins

There were multiple significant correlations between the TBI-specific proteins, particularly between neuronal and astroglial markers, tau proteins and proteins associated with neurodegeneration (Fig. 4). In turn, many of these proteins showed significant correlations with IL16, SQSTM1 and MDH1. Although most were positive correlations, MDH1 levels were inversely correlated with levels of plasma Abeta42, and FCN2 was inversely correlated with pTau231 but positively correlated with Abeta42.

Figure 4.

Correlations between proteins. Correlation matrix of traumatic brain injury (TBI)-specific proteins (identified by differential expression analysis) within the TBI cohort. Proteins are ordered by category, separated by a dashed line. See Supplementary Table 2 for category. Only statistically significant results (false discovery rate adjusted P < 0.05) are shown.

Cluster analysis of acute plasma proteins identifies TBI subgroups with distinct MRI findings

We next performed exploratory clustering analysis to assess whether variation in acute protein levels could identify distinct groups in a data-driven way. The k means cluster analysis of plasma proteins using the Alamar NULISA™ CNS Diseases panel identified five groups [total wiss (within cluster sum of squares) = 6988.2, between sum of squares/total sum of squares = 31.5] (Fig. 5A). We separated TBI-only/TBI-predominant groups (Clusters 3, 4 and 5) from control-predominant groups (Clusters 1 and 2) (Table 2 and Fig. 5A). Furthermore, this analysis differentiated a TBI subgroup with a high burden of focal injury (Cluster 4) (Fig. 5A and B, right). There was a main effect of cluster type on mean skeleton FA z-score [F(4) = 6.624, P = 0.00025], corpus callosum FA z-score [F(4) = 7.151, P = 0.000134] and lesion volume [F(4) = 10.33, P = 2.45 × 10−6] assessed on subacute MRI (Fig. 5B). Tukey’s post hoc tests confirmed that Cluster 5 had lower corpus callosum and mean skeleton FA z-scores than both control-predominant clusters (Clusters 1 and 2), whilst Cluster 4 had greater lesion volumes than both control-predominant clusters and Cluster 5 (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Cluster analysis identifying traumatic brain injury subgroups. (A) Cluster analysis identified five clusters, with three TBI-predominant clusters (Clusters 3, 4 and 5) and two non-TBI predominant clusters (Clusters 1 and 2). The black box highlights a set of proteins with marked differently levels between TBI-predominant Clusters 4 and 5. CON = non-injured healthy controls; NTT = non-TBI trauma controls; TBI = traumatic brain injury. (B) Comparison of MRI measures between the clusters. Cluster 5 had significantly lower mean skeleton fractional anisotropy (FA) and mean corpus callosum FA, in comparison to Clusters 1 and 2. In contrast, Cluster 4 had significantly higher lesion volumes than Clusters 1, 2 and 5. *P < 0.05 on Tukey’s post hoc test, performed after a statistically significant effect of cluster was identified using ANOVA. Note that only CON and TBI groups had MRI.

Table 2.

Characteristics of traumatic brain injury clusters

| Characteristic | Cluster | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | Cluster 4 | Cluster 5 | |

| Cohort distribution | 7 CON | 19 CON | 8 TBI | 15 TBI | 10 TBI |

| 16 NTT | 4 NTT | – | – | 2 NTT | |

| 4 TBI | 1 TBI | – | – | – | |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 36.5 (18.2) | 42.3 (15.6) | 49.9 (17.7) | 42.5 (15.3) | 45.2 (17.9) |

| MRI acquisition timea, day after TBI, median (IQR) | 24.5 (20.8–25.3) | 14 | 19 (15–26.5) | 20 (15–33.5) | 14 (12–18) |

| Lesion volumea, mm3, mean (SD) | 1177.09 (2623.92) | 1761.00 | 18 163.86 (22 227.08) | 32 849.83 (27 693.92) | 11 304.52 (10 317.78) |

| Mean skeleton FA z-score, mean (SD) | 0.04 (0.34) | 0.16 (0.28) | −0.49 (0.67) | −0.37 (0.62) | −0.88 (0.65) |

| Mean corpus callosum FA z-score, mean (SD) | 0.19 (0.37) | 0.16 (0.45) | −0.89 (1.43) | −0.70 (0.95) | −2.14 (2.07) |

| Marshall CT gradea,b | |||||

| Diffuse injury I | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Diffuse injury II | 4 | 1 | 4 | 8 | 3 |

| Diffuse injury III | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Diffuse injury IV | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| EML V | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| NEML VI | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 4 |

| GOS-E category (6 months)a | |||||

| Dead (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| VS (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| LSD (3) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| USD (4) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| LMD (5) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| UMD (6) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| LGR (7) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| UGR (8) | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Lost to follow-up | 2 | n/a | n/a | 1 | 1 |

| GOS-E category (12 months)a | |||||

| DEAD (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| VS (2) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| LSD (3) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| USD (4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| LMD (5) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| UMD (6) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| LGR (7) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| UGR (8) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Lost to follow-up | 2 | n/a | 1 | 4 | 2 |

EML = evacuated mass lesion; FA = fractional anisotropy; GCS = Glasgow Coma Scale; GOS-E = Glasgow Outcome Scale Extended; LGR = lower good recovery; LMD = lower moderate disability; LSD = lower severe disability; n/a = not applicable; NEML = non-evacuated mass lesion; NR = non-reactive; TBI = traumatic brain injury; UGR = upper good recovery; UMD = upper moderate disability; USD = upper severe disability; VS = vegetative state.

aFor TBI participants only.

bOn initial CT.

Compared with the control-predominant clusters (Cluster 1 and 2), the TBI-predominant Cluster 5 had significantly lower mean skeleton FA z-score [mean difference between Cluster 5 and Cluster 1 = −0.92, 95% confidence interval (CI) (−1.67, −0.17), P = 0.009; mean difference between Cluster 5 and Cluster 2 = −1.03, 95% CI (−1.70, 0.37), P = 0.0006] and corpus callosum FA z-score [mean difference between Cluster 5 and Cluster 1 = −2.33, 95% CI (−3.86, −0.80), P = 0.0007; mean difference between Cluster 5 and Cluster 2 = −2.30, 95% CI (−3.67, −0.93), P = 0.0002]. In contrast, the TBI-only Cluster 4 had significantly greater lesion volumes than control-predominant Cluster 1 [mean difference = 31 672.74, 95% CI (13 559.48, 49 786.00), P = 0.00007] and Cluster 2 [mean difference = 32 761.78, 95% CI (17 096.16, 48 427.40), P = 0.000002]. Furthermore, Cluster 4 also had significantly higher lesion volume than Cluster 5, despite both being TBI-predominant groups [mean difference = 21 545.40, 95% CI (1620.72, 41 490.90), P = 0.029]. These findings cannot be attributed to more lesion resolution with time, because Cluster 4 has a later median MRI acquisition time than Cluster 5. Likewise, Cluster 5 has the lowest white matter FA z-scores of the TBI subgroups, which cannot be explained by ongoing white matter degeneration, because it has the earliest median MRI acquisition time.

Plasma proteins whose acute levels were higher than the whole group mean in Cluster 4 and lower than the whole group mean in Cluster 5 included inflammasome-associated proteins (e.g. IL18), pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL7) and proteins associated with neurodegenerative disease [e.g. alpha-synuclein (SCNA), oligo-alpha-synuclein (SCNA), superoxide dismutase (SOD1), TAR DNA binding protein 43/TDP-43 (TARDBP) and TDP-43 with phosphorylation on serine 409 (pTDP43.409)] (Fig. 5B). There was no difference in GOS-E at 6 months (χ2 = 2.1325, d.f. = 4, P-value = 0.7114) or 12 months (χ2 = 2.902, d.f. = 4, P-value = 0.5744) or in age [F(4) = 1.251, P = 0.296] between any of the clusters. However, we were unable to adjust for potential confounds.

Proteins measured with two assays showed excellent overall agreement

As a range of proteomic platforms become available, an important issue is whether results are consistent across panels. Pearson correlations for proteins that were assessed in two different assays (Alamar NULISA™plus either OLINK®/Simoa®/Millipore) found high correlation coefficients (r > 0.8) for most overlapping proteins (Fig. 6). Notably and unsurprisingly, proteins for which >50% of samples were flagged as below the limit of detection on one of the panels (neuronal growth factor beta-subunit, IL2, IL4, IL5 and IL13) had very low correlation coefficients. Additionally, for all proteins with a correlation coefficient >0.8 across two assays, ANOVA testing drew the same conclusion about the effect of group (CON, NTT and TBI) on protein levels (Supplementary Fig. 4). All but two proteins (MCP1/CCL2 and IFNg) also had the same pairwise group differences on post hoc testing (Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 4). There were some differences in fold changes detected with different assay approaches (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Figure 6.

Correlations between assay approaches. Pearson correlation between levels of proteins assessed by two different assay approaches (the Alamar NULISA™ CNS Diseases panel, horizontal, versus OLINK® Target 96 Inflammation panel or Simoa® or Millipore ELISA-based assay, vertical). The correlation coefficient is shown superimposed on a representative circle. Red boxes denote proteins for which >50% samples were below the limit of detection (LOD) of the OLINK panel. We used 50% of samples as the cut-off because this would mean that below the LOD would not be simply from one participant type. Inset are plots of three of the overlapping proteins: IL6 and GFAP, which show excellent correlation between two assay approaches, and IL4, which shows very poor correlation. Note: NEFL/NFL, MAPT/total tau, MCP1/CCL2 and MCP4/CCL13 are the same proteins, but named differently in the different assays.

Discussion

Using the novel multiplex proteomic assay, Alamar NULISA™ CNS Diseases, we identify several proteins whose plasma expression was altered specifically in acute TBI patients, in comparison to non-TBI trauma and non-injured participants. We show TBI-specific deranged plasma levels of proteins associated with neurodegenerative disease (PSEN1 and 14-3-3γ), immune signalling (FCN2 and SFRP1), cell metabolism (MDH1) and autophagy (SQSTM1). This provides in-human evidence of several pathways implicated in TBI pathophysiology, which have previously been shown only in animal studies. Additionally, we show that changes in plasma phosphorylated Tau-231 (pTau231) and Abeta42 are specific to TBI, and not NTT. We also replicate, on a new multiplex immunoassay platform, previous findings that neuronal and astroglial markers (GFAP, S100B, UCH-L1, TAU and NFL) have utility as TBI-specific markers. Conversely, our study suggests that some proteins, such as IL6 and IL10, might be deranged in a non-specific, acute response to any injury. We have related acute levels of TBI-specific proteins with each other, and of UCH-L1, total tau, pTau231, PSEN1, CCL2 and SQSTM1 with subacute neuroimaging measures of injury. Furthermore, we find that different patterns of plasma protein expression can identify TBI subgroups with specific injury pathologies. Overall, we show that studying acute patterns of plasma protein expression can help to quantify focal injury and identify potential processes, including neurodegeneration and inflammation, that are important in human TBI pathophysiology. This provides a basis for more rational classification of TBI based on pathophysiology.

Deranged proteins reflect inflammatory pathways and multiple cellular processes

We found acutely raised levels of the inflammatory proteins IL6, IL10, IL1b, IL8, IL15, IL16, serum amyloid A (SAA1) and CCL2 after TBI, in line with prior studies assessing both blood4,21-34 and CSF/microdialysate.12,35 In contrast to many prior studies, we recruited a non-TBI trauma control cohort, and thus demonstrated that changes in plasma levels of IL8, SAA1 and IL15 might reflect general injury responses. IL1b, IL10 and IL6 levels were raised in both NTT and TBI compared with CON, but were higher in TBI than in NTT, suggestive of involvement in a general pro-inflammatory response to injury, which is exaggerated by TBI.

Conversely, IL16 and CCL2 were elevated specifically in TBI, which might reflect their roles in promoting neuroinflammation. IL16 is produced by CD4+ and CD8+ cells, including microglia in the brain, and acts as a chemokine and activating signal for CD4+ cells, such as T lymphocytes, monocytes and macrophages.36-38 Peripheral CD4+ T-lymphocyte activation is reported in acute human TBI,21 and experimental studies have found that CD4+ T lymphocytes can increase injury severity.39 Increased IL16 expression is seen in experimental neuroinflammation, as a result of infiltrating immune cells and microglial activation.40 Preclinical studies show that CCL2 is a key mediator of post-injury neuroinflammation, possibly through its role in increasing blood–brain barrier permeability and attracting monocytes to the brain.41,42 Our results are thus in keeping with TBI triggering release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) that cause activated microglia to release IL16 that, along with CCL2, results in increased immune cell infiltration into the brain and acute neuroinflammation that is particularly harmful to white matter. In keeping with this interpretation, acutely increased CCL2 levels were correlated with lower subacute corpus callosum white matter integrity, a marker of traumatic axonal injury, which we have previously shown to relate to cognitive and functional outcomes,43-46 tau deposition47 and brain atrophy48 after TBI.

There were TBI-specific changes in other proteins implicated in post-injury neuroinflammation. FCN2 aids clearance of dying cells and is also an initiator of the lectin complement pathway,10,49 which is activated in brain tissue after experimental TBI.10 Complement proteins are also correlated with measures of blood–brain barrier permeability and outcome in acute severe TBI.12 The positive correlation with Abeta42 and inverse correlation with pTau231 might indicate that acute activation of these pathways is beneficial after TBI, but this requires further investigation. SFRP1 is a cell–cell signalling molecule involved in multiple pathways relevant to neuroinflammation, such as Wnt signalling. Astrocyte-derived SFRP1 after experimental TBI leads to sustained microglial activation, promoting a state of chronic neuroinflammation.50 The clinical significance of our new finding, that of reduced plasma levels acutely in human TBI, is uncertain. SQSTM1/p62-mediated autophagy51 is important for peripheral myeloid cell differentiation52 and microglial functions, including degradation of amyloid plaques.53 Raised SQSTM1 in our TBI cohort was associated with less axonal injury, as measured on DTI, supporting a role for post-injury autophagy in mitigating axonal injury. Indeed, experimental TBI studies have shown that impaired autophagy by microglia and macrophages reduces clearance of DAMPs and pro-inflammatory signals, like the NLRP3 inflammasome, which exacerbates post-injury neuroinflammation and worsens outcomes.9

Changes in cell metabolism, such as oxidative stress and abnormal glucose metabolism, contribute to secondary injury after the initial TBI event.54-56 Experimental studies have found reduced astrocytic MDH1 expression in concussive TBI models57 and increased thalamic expression in blast TBI models.58 MDH1 acetylation reduces oxidative stress after intracerebral haemorrhage, and reduced MDH1 activity is associated with cell senescence.59,60 TBI-specific raised plasma MDH1 in our study might reflect dysfunctional glucose metabolism and response to oxidative stress.

Neurodegenerative markers are deranged in TBI

We identified TBI-specific derangement of several proteins associated with neurodegenerative disease. For example, pTau231, which was elevated, is a sensitive marker of early brain tau pathology and increases with amyloid beta deposition in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease.61 We and others have demonstrated tau pathology after single-hit moderate–severe TBI, as early as 1 year post-TBI, compared with controls.47,62,63 Higher rates of brain atrophy are seen after TBI,64,65 and experimental studies have also demonstrated that TBI initiates a cascade of prion-like self-propagating tau pathology.63 Therefore, increased pTau231, an abnormal phosphorylated tau isoform, in the acute period is intriguing because it might indicate the beginning of pathological processes that lead to later neurodegeneration. In contrast, acute plasma levels of pTau181 and pTau217 were raised compared with CON but did not reach statistical significance compared with the NTT cohort. There are no prior clinical acute TBI studies of pTau217, and prior studies of pTau181 have reported conflicting findings about whether pTau181 is acutely elevated in TBI.66,67 Chronic traumatic encephalopathy might have distinct tau pathology from other neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s,68,69 hence the ability to assess multiple isoforms on one panel might be useful for future in vivo differentiation of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Given the difficulty of diagnosing chronic traumatic encephalopathy in life, cohort studies or data banks, such as CONNECT-TBI,70 which have both blood samples (e.g. for pTau231) and post-mortem samples, would help to validate differential patterns of these markers as potential diagnostic tools for different types of post-TBI neurodegeneration.

We also found lower levels of plasma Abeta42 in acute TBI, compared with NTT and CON. Prior studies have found both reduced and increased CSF Abeta42 levels71-73 in acute TBI, and two prior human TBI studies reported raised plasma Abeta42 levels in acute TBI.72,74 Plasma and CSF Abeta42 levels are reduced in Alzheimer’s disease, because soluble amyloid isoforms decrease as they condense into amyloid plaques.75,76 Therefore, our finding of reduced plasma Abeta42 in acute TBI fits with the idea that TBI triggers neurodegenerative processes. Future studies should aim to elucidate whether acute pTau231 and Abeta42 elevation predicts higher rates of brain atrophy and neurodegeneration after TBI.

Plasma levels of the neurodegenerative proteins PSEN1 and 14-3-3γ showed TBI-specific acute increases after TBI, which has not been reported previously in clinical TBI studies. Abnormal amyloid plaque formation can occur within 24 h after TBI.77 Amyloid precursor protein (APP), enzymes required for its cleavage (specifically, BACE1 and PSEN1) and Abeta are co-located in these abnormal diffuse amyloid plaques early after TBI; they accumulate in axons in both human pathological and experimental TBI studies, and inhibition of cleavage activity in experimental TBI reduces injury-induced cell loss and behavioural deficits.78-80 Axonal disruption and cell death during TBI might promote abnormal amyloid plaque formation by forcing together all the components necessary for abnormal APP cleavage,77 and the raised PSEN1 we show might reflect this process. Raised CSF levels of 14-3-3ζ have previously been reported in TBI,81 but raised plasma 14-3-3γ (YWHAG) is reported here for the first time. This brain-enriched intracellular signal transduction is a component of pathological protein depositions in several neurodegenerative diseases82 and is also a marker of neuronal injury in the diagnosis of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease.83 Therefore, raised levels of YWHAG in our acute TBI cohort might reflect neuronal damage, with its implications to be investigated further.

TBI subgroups defined by proteomics reflect different neuroimaging injury patterns

Our exploratory cluster analysis suggests that heterogeneity of plasma protein expression patterns might reflect injury characteristics. This data-driven approach differentiated TBI from non-injured and non-TBI trauma cohorts, in addition to identifying TBI subgroups with specific pathological characteristics. These new findings might indicate that different pathophysiological processes mediate the development of white matter versus lesional injury. For example, TBI subgroups with significantly different lesion volumes had markedly different expression patterns of pro-inflammatory proteins (e.g. IL18, an NLRP3 inflammasome-associated protein84), neurotrophins (e.g. BDNF), and neuronal injury and neurodegenerative disease proteins (e.g. SOD1, TDP-43 proteins and alpha-synuclein proteins). We also found correlations between acute levels of neurodegenerative proteins (pTau231, total tau and PSEN1) and the neuronal marker UCH-L1 and subacute lesion volume, but not white matter integrity. Future work can seek to disentangle whether and how these proteins and associated pathways contribute to lesion development, and whether there is regional variation in the relationship between brain structural measures and plasma protein levels, as we have previously shown with GFAP.85

Several proteins were assessed with two different assay types, the Alamar NULISA™ assay and/or ELISA and OLINK® PEA assays. There was generally excellent correlation of assay values for overlapping proteins between the Alamar NULISA™ and OLINK® or ELISA-based platforms, in addition to agreement between panels about the significance of findings. This overall consistency across platforms increases confidence in the new findings and further strengthens the case for NFL, GFAP, S100B, total tau and UCH-L1 as biomarkers of TBI and its severity. Important exceptions to the generally good correlation between panels were for proteins where >50% of samples were below the level of detection of the OLINK® assay. This suggests that there is a threshold for protein changes to be robust enough to be platform agnostic. This is an important consideration for future work, for example, if using these assays to track treatment responses.

Limitations

AAlthough we show several new and interesting findings, our work is exploratory. The cohort size means that we cannot perform multivariate analyses to investigate the mechanistic or prognostic role of specific proteins to specific outcomes. Our results should motivate experiments to investigate why and how the protein patterns identified arise, and the associated clinical implications. Replication is necessary in larger and more diverse cohorts, such as those with repetitive and milder TBIs. The median sampling time was 1 day earlier for TBI participants compared with NTT, which might have contributed to some differences in protein levels we found. For example, a previous study found that the biggest difference in plasma CCL2 levels between TBI and NTT cohorts was 6 h after injury.30 However, difference in sampling time cannot fully explain our findings; for example, CCL2 remains elevated in TBI up to 72 h,30 and we previously found that neuronal and astroglial markers (NFL, GFAP, total tau and UCH-L1) plasma levels remain elevated in TBI, compared with NTT, at later acute time points.3 It is also possible, given the early sampling median time point in our study, that we did not detect delayed TBI-specific changes or peaks in plasma protein levels. Some of the TBI-specific changes in plasma proteins levels we found have not previously been demonstrated in clinical TBI studies, hence we cannot know when in the trajectory of the protein rise and fall our sample was taken. A priority for future clinical studies is explicitly to study the time course of plasma protein changes.

Our groups were not explicitly matched at recruitment for comorbidities, and limited comorbidity information is available. This might be a potential source of bias in our study if some comorbidities themselves contribute to differences in plasma protein levels. Many of the proteins we found to be deranged specifically after TBI have not been investigated outside the context of neurological and psychiatric disease, which were exclusion criteria for all study participants. Nevertheless, the potential impact of comorbidities, for example through interaction with injury processes, needs to be investigated fully. Larger cohorts, with prespecified subgroups, can investigate how the proteins we have identified might be influenced by patient factors, such as age, sex and comorbidities, and test their prognostic value. Sensitivity analyses would help to elucidate the potential influence of factors such as comorbidities, where it is not always practical to match during recruitment.

The present study cannot differentiate the tissue or cell provenance of proteins, whether their levels represent release from cell death or unregulated expression, or whether their derangement contributes to or only accompanies TBI pathology. Additionally, because our findings were in blood, not CSF, it is likely that we could not detect all the proteomic changes occurring after TBI. For example, a previous clinical TBI study found changes in CXCL1 and neuronal pentraxin-1 only in CSF,12 and we did not find these two proteins to be differentially expressed in the plasma. Studies with paired CSF and plasma samples and studies in which proteins are experimentally upregulated or knocked out are needed to address these questions.

Some of the proteins assayed, particularly inflammatory proteins, are affected by injury other than TBI, hence interpretation of our results is limited by the different distribution of extracranial injuries within the TBI group compared with the NTT group. It is not known, for example, whether or how the assayed proteins are differentially affected by different types of extracranial injuries.

Our study highlights the importance of including NTT cohorts in protein biomarker studies, and further attempting to closely match or account for extracranial injury type where possible. Half of our NTT group were limb fractures, which is a risk factor for delirium, occurring in ∼10%–35% of hip fractures.86,87 Studies of perioperative delirium show increased plasma levels of inflammatory cytokines88 and tau.89,90 This means that although the NTT group enabled us to identify protein responses specific to TBI, compared with general injury, the NTT group might not be a fully ‘brain neutral’ control group. However, there are clearly important differences between TBI and delirium pathophysiology, for example, demonstrated by the fact that raised CSF and plasma GFAP is a robust finding in TBI but not in delirium.89-91 Our results are therefore still likely to reflect aspects of pathophysiology specific to TBI, but future work should consider potential brain effects of different non-healthy control groups. Owing to sample size, we could not adjust for potential confounds in our cluster analyses, hence input samples differed with regard to factors, such as systemic complications, that might independently have influenced clustering results. Of note, some confounds, such as secondary injury, might also be important pathophysiological processes relevant to TBI extent and outcome. Teasing this apart is beyond the scope of the present study and requires both mechanistic work focused on specific markers, in addition to replication in larger cohorts that enable finer matching or adjustment of confounds.

Finally, assays that report in relative units, such as the Alamar and OLINK® panels, are more suited to the discovery and hypothesis-generating work that we have done than for direct clinical use. The relative units also mean that we could only assess correlation between assays, but not agreement.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we identify novel proteins whose plasma levels are specifically deranged in acute TBI, compared with non-TBI trauma and non-injured controls. These proteins are involved in neurodegeneration, cell metabolism, autophagy and inflammation. We also show correlations between inflammatory proteins and those associated with neurodegeneration. Furthermore, we find that patterns of protein expression distinguish subgroups with TBI. We highlight how a multiplex proteomic approach can contribute to pathophysiological classification of TBI, which is a crucial step towards improved prognostication and identification of treatments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Alamar for providing complimentary testing.

Contributor Information

Lucia M Li, Department of Brain Sciences, Imperial College London, London W12 0BZ, UK; UK Dementia Research Institute Centre for Care Research & Technology, Imperial College London and University of Surrey, London W12 0BZ, UK.

Eleftheria Kodosaki, Department of Neurodegenerative Disease, UCL Institute of Neurology, London WC1N 3BG, UK; UK Dementia Research Institute, UCL, London W1T 7NF, UK.

Amanda Heslegrave, Department of Neurodegenerative Disease, UCL Institute of Neurology, London WC1N 3BG, UK; UK Dementia Research Institute, UCL, London W1T 7NF, UK.

Henrik Zetterberg, UK Dementia Research Institute, UCL, London W1T 7NF, UK; Department of Psychiatry and Neurochemistry, Institute of Neuroscience and Physiology, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg 431 41, Sweden; Clinical Neurochemistry Laboratory, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Mölndal 413 45, Sweden.

Neil Graham, Department of Brain Sciences, Imperial College London, London W12 0BZ, UK; UK Dementia Research Institute Centre for Care Research & Technology, Imperial College London and University of Surrey, London W12 0BZ, UK.

Karl Zimmerman, Department of Brain Sciences, Imperial College London, London W12 0BZ, UK; UK Dementia Research Institute Centre for Care Research & Technology, Imperial College London and University of Surrey, London W12 0BZ, UK.

Eyal Soreq, Department of Brain Sciences, Imperial College London, London W12 0BZ, UK; UK Dementia Research Institute Centre for Care Research & Technology, Imperial College London and University of Surrey, London W12 0BZ, UK.

Thomas Parker, Department of Brain Sciences, Imperial College London, London W12 0BZ, UK; UK Dementia Research Institute Centre for Care Research & Technology, Imperial College London and University of Surrey, London W12 0BZ, UK.

Elena Garbero, Department of Medical Epidemiology, Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario Negri IRCCS, Milan, Bergamo 21056, Italy.

Federico Moro, Department of Acute Brain and Cardiovascular Injury, Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario Negri IRCCS, Milan, Bergamo 21056, Italy.

Sandra Magnoni, Department of Medicine, Surgery and Pharmacy, University of Sassari, Sassari 07100, Italy.

Guido Bertolini, Department of Medical Epidemiology, Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario Negri IRCCS, Milan, Bergamo 21056, Italy.

David J Loane, School of Biochemistry and Immunology, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin 2, Ireland; Department of Anesthesiology and Shock, Trauma and Anesthesiology (STAR) Research Center, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD 21201, USA.

David J Sharp, Department of Brain Sciences, Imperial College London, London W12 0BZ, UK; UK Dementia Research Institute Centre for Care Research & Technology, Imperial College London and University of Surrey, London W12 0BZ, UK.

Data availability

Datasheets, R workspace and R code scripts will be made available to any reasonable request.

Funding

ERA-Net NEURON (MR/R004528/1), a part of the European Research Projects on External Insults to the Nervous System call, within the Horizon 2020 funding framework, provided the core funds for the project. The UK Dementia Research Institute provided additional funds. L.M.L., T.P. and N.G. are supported by National Insitute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) academic clinical lectureships and acknowledge the support of the Imperial NIHR BRC. N.G. acknowledges support of Academy of Medical Sciences. H.Z. is a Wallenberg Scholar and a Distinguished Professor at the Swedish Research Council supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council (2023-00356, 2022-01018 and 2019-02397), the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 101053962, Swedish State Support for Clinical Research (ALFGBG-71320), the Alzheimer Drug Discovery Foundation (ADDF), USA (201809-2016862), the AD Strategic Fund and the Alzheimer’s Association (ADSF-21-831376-C, ADSF-21-831381-C, ADSF-21-831377-C and ADSF-24-1284328-C), the Bluefield Project, Cure Alzheimer’s Fund, the Olav Thon Foundation, the Erling-Persson Family Foundation, Stiftelsen för Gamla Tjänarinnor, Sweden (FO2022-0270), the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 860197 (MIRIADE), the European Union Joint Programme—Neurodegenerative Disease Research (JPND2021-00694), the National Institute for Health and Care Research University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre and the UK Dementia Research Institute at UCL (UKDRI-1003). D.L. acknowledges support of Science Foundation Ireland (SFI) grant SFI17/FRL/4860. D.J.S. is funded by the UK Dementia Research Institute.

Competing interests

Alamar Biosciences provided complimentary testing of samples but were not involved in the analysis or interpretation of results or write-up of the manuscript. H.Z. has served on scientific advisory boards and/or as a consultant for Abbvie, Acumen, Alector, Alzinova, ALZPath, Amylyx, Annexon, Apellis, Artery Therapeutics, AZTherapies, Cognito Therapeutics, CogRx, Denali, Eisai, Merry Life, Nervgen, Novo Nordisk, Optoceutics, Passage Bio, Pinteon Therapeutics, Prothena, Red Abbey Labs, reMYND, Roche, Samumed, Siemens Healthineers, Triplet Therapeutics and Wave, has given lectures in symposia sponsored by Alzecure, Biogen, Cellectricon, Fujirebio, Lilly, Novo Nordisk and Roche, and is a co-founder of Brain Biomarker Solutions in Gothenburg AB (BBS), which is a part of the GU Ventures Incubator Program (outside submitted work). D.J.S. has received an honorarium from the Rugby Football Union for participation in an expert concussion panel. D.J.S. receives payment by Rugby Football Union, The Football Association and Premiership Rugby for private clinical services at the Institute of Sports Exercise and Health. There are no other conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Brain online.

References

- 1. Maas AIR, Menon DK, Manley GT, et al. Traumatic brain injury: Progress and challenges in prevention, clinical care, and research. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21:1004–1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tenovuo O, Diaz-Arrastia R, Goldstein LE, Sharp DJ, van der Naalt J, Zasler ND. Assessing the severity of traumatic brain injury—time for a change? J Clin Med. 2021;10:148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Graham NSN, Zimmerman KA, Moro F, et al. Axonal marker neurofilament light predicts long-term outcomes and progressive neurodegeneration after traumatic brain injury. Sci Transl Med. 2021;13:eabg9922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kumar RG, Boles JA, Wagner AK. Chronic inflammation after severe traumatic brain injury: Characterization and associations with outcome at 6 and 12 months postinjury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2015;30:369–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Peters AJ, Schnell E, Saugstad JA, Treggiari MM. Longitudinal course of traumatic brain injury biomarkers for the prediction of clinical outcomes: A review. J Neurotrauma. 2021;38:2490–2501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. OLINK . OLINK company website. Accessed 15 October 2024. https://olink.com/technology/what-is-pea

- 7. Feng W, Beer JC, Hao Q, et al. NULISA: A proteomic liquid biopsy platform with attomolar sensitivity and high multiplexing. Nat Commun. 2023;14:7238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Teunissen CE, Kimble L, Bayoumy S, et al. Methods to discover and validate biofluid-based biomarkers in neurodegenerative dementias. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2023;22:100629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hegdekar N, Sarkar C, Bustos S, et al. Inhibition of autophagy in microglia and macrophages exacerbates innate immune responses and worsens brain injury outcomes. Autophagy. 2023;19:2026–2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ciechanowska A, Ciapała K, Pawlik K, et al. Initiators of classical and lectin complement pathways are differently engaged after traumatic brain injury—time-dependent changes in the cortex, striatum, thalamus and hippocampus in a mouse model. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Graham NSN, Zimmerman KA, Bertolini G, et al. Multicentre longitudinal study of fluid and neuroimaging BIOmarkers of AXonal injury after traumatic brain injury: The BIO-AX-TBI study protocol. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e042093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lindblad C, Pin E, Just D, et al. Fluid proteomics of CSF and serum reveal important neuroinflammatory proteins in blood–brain barrier disruption and outcome prediction following severe traumatic brain injury: A prospective, observational study. Crit Care. 2021;25:103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Malec JF, Brown AW, Leibson CL, et al. The Mayo classification system for traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2007;1424:1417–1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jennett B, Snoek J, Bond MR, Brooks N. Disability after severe head injury: Observations on the use of the Glasgow Outcome Scale. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1981;44:285–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TEJ, Woolrich MW, Smith SM. FSL. Neuroimage. 2012;62:782–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhang H, BB Avants, PA Yushkevich, et al. High-dimensional spatial normalization of diffusion tensor images improves the detection of white matter differences: An example study using amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2007;26:1585–1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Winkler AM, Ridgway GR, Webster MA, Smith SM, Nichols TE. Permutation inference for the general linear model. Neuroimage. 2014;92:381–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. OLINK . OLINK Target 96 Inflammation Panel. Accessed 21 February 2024. https://olink.com/products-services/target/inflammation/

- 19. Alamar Biosciences . Alamar NULISA Technology. Accessed 28 March 2024. https://alamarbio.com/technology/nulisa-platform/

- 20. Rubenstein R, Chang B, Yue JK, et al. Comparing plasma phospho tau, total tau, and phospho tau–total tau ratio as acute and chronic traumatic brain injury biomarkers. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74:1063–1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Magatti M, Pischiutta F, Ortolano F, et al. Systemic immune response in young and elderly patients after traumatic brain injury. Immun Ageing. 2023;20:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lindqvist D, Dhabhar FS, Mellon SH, et al. Increased pro-inflammatory milieu in combat related PTSD—a new cohort replication study. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;59:260–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hergenroeder GW, Moore AN, McCoy JP Jr, et al. Serum IL-6: A candidate biomarker for intracranial pressure elevation following isolated traumatic brain injury. J Neuroinflammation. 2010;7:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pierce ME, Hayes J, Huber BR, et al. Plasma biomarkers associated with deployment trauma and its consequences in post-9/11 era veterans: Initial findings from the TRACTS longitudinal cohort. Transl Psychiatry. 2022;12:80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chaban V, Clarke GJB, Skandsen T, et al. Systemic inflammation persists the first year after mild traumatic brain injury: Results from the prospective Trondheim mild traumatic brain injury study. J Neurotrauma. 2020;37:2120–2130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Edwards KA, Pattinson CL, Guedes VA, et al. Inflammatory cytokines associate with neuroimaging after acute mild traumatic brain injury. Front Neurol. 2020;11:348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gill J, Motamedi V, Osier N, et al. Moderate blast exposure results in increased IL-6 and TNFα in peripheral blood. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;65:90–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wu X, Xu W, Zhang T, Bao W. Peripheral inflammatory markers in patients with prolonged disorder of consciousness after severe traumatic brain injury. Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10:9114–9121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chen Y, Wang Y, Xu J, et al. Multiplex assessment of serum chemokines CCL2, CCL5, CXCL1, CXCL10, and CXCL13 following traumatic brain injury. Inflammation. 2023;46:244–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rowland B, Savarraj JPJ, Karri J, et al. Acute inflammation in traumatic brain injury and polytrauma patients using network analysis. Shock. 2020;53:24–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yue JK, Kobeissy FH, Jain S, et al. Neuroinflammatory biomarkers for traumatic brain injury diagnosis and prognosis: A TRACK-TBI pilot study. Neurotrauma Rep. 2023;4:171–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Di Battista AP, Churchill N, Rhind SG, Richards D, Hutchison MG. Evidence of a distinct peripheral inflammatory profile in sport-related concussion. J Neuroinflammation. 2019;16:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Di Battista AP, Rhind S, Hutchison MG, et al. Inflammatory cytokine and chemokine profiles are associated with patient outcome and the hyperadrenergic state following acute brain injury. J Neuroinflammation. 2016;13:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Thompson HJ, Martha SR, Wang J, Becker KJ. Impact of age on plasma inflammatory biomarkers in the 6 months following mild traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2020;35:324–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dyhrfort P, Wettervik TS, Clausen F, Enblad P, Hillered L, Lewén A. A dedicated 21-plex proximity extension assay panel for high-sensitivity protein biomarker detection using microdialysis in severe traumatic brain injury: The next step in precision medicine? Neurotrauma Rep. 2023;4:25–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cruikshank W, Center DM. Modulation of lymphocyte migration by human lymphokines. II. Purification of a lymphotactic factor (LCF). J. Immunol. 1982;128:2569–2574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mathy NL, Bannert N, Norley SG, Kurth R. Cutting edge: CD4 is not required for the functional activity of IL-16. J. Immunol. 2000;164:4429–4432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schluesener HJ, Seid K, Kretzschmar J, Meyermann R. Leukocyte chemotactic factor, a natural ligand to CD4, is expressed by lymphocytes and microglial cells of the MS plaque. J Neurosci Res. 1996;44:606–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fee D, Crumbaugh A, Jacques T, et al. Activated/effector CD4+ T cells exacerbate acute damage in the central nervous system following traumatic injury. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;136:54–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hridi SU, Barbour M, Wilson C, et al. Increased levels of IL-16 in the central nervous system during neuroinflammation are associated with infiltrating immune cells and resident glial cells. Biology (Basel). 2021;10:472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Szmydynger-Chodobska J, Strazielle N, Gandy JR, et al. Posttraumatic invasion of monocytes across the blood–cerebrospinal fluid barrier. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:93–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Murugan M, Ravula A, Gandhi A, et al. Chemokine signaling mediated monocyte infiltration affects anxiety-like behavior following blast injury. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:340–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kinnunen KM, Greenwood R, Powell JH, et al. White matter damage and cognitive impairment after traumatic brain injury. Brain. 2011;134:449–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sharp DJ, Beckmann CF, Greenwood R, et al. Default mode network functional and structural connectivity after traumatic brain injury. Brain. 2011;134:2233–2247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Li LM, Violante IR, Zimmerman K, et al. Traumatic axonal injury influences the cognitive effect of non-invasive brain stimulation. Brain. 2019;142:3280–3293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jolly AE, Bălăeţ M, Azor A, et al. Detecting axonal injury in individual patients after traumatic brain injury. Brain. 2021;144:92–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gorgoraptis N, Li LM, Whittington A, et al. In vivo detection of cerebral tau pathology in long-term survivors of traumatic brain injury. Sci Transl Med. 2019;11:eaaw1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Graham NSN, Cole JH, Bourke NJ, Schott JM, Sharp DJ. Distinct patterns of neurodegeneration after TBI and in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2023;19:3065–3077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jensen ML, Honoré C, Hummelshøj T, Hansen BE, Madsen HO, Garred P. Ficolin-2 recognizes DNA and participates in the clearance of dying host cells. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:856–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rueda-Carrasco J, Martin-Bermejo MJ, Pereyra G, et al. SFRP1 modulates astrocyte-to-microglia crosstalk in acute and chronic neuroinflammation. EMBO Rep. 2021;22:e51696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jakobi AJ, Huber ST, Mortensen SA, et al. Structural basis of p62/SQSTM1 helical filaments and their role in cellular cargo uptake. Nat Commun. 2020;11:440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wang Z, Cao L, Kang R, et al. Autophagy regulates myeloid cell differentiation by p62/SQSTM1-mediated degradation of PML-RARα oncoprotein. Autophagy. 2011;7:401–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Choi I, Wang M, Yoo S, et al. Autophagy enables microglia to engage amyloid plaques and prevents microglial senescence. Nat Cell Biol. 2023;25:963–974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Eastman CL, D’Ambrosio R, Ganesh T. Modulating neuroinflammation and oxidative stress to prevent epilepsy and improve outcomes after traumatic brain injury. Neuropharmacology. 2020;172:107907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Khellaf A, Garcia NM, Tajsic T, et al. Focally administered succinate improves cerebral metabolism in traumatic brain injury patients with mitochondrial dysfunction. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2022;42:39–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Strogulski NR, Portela LV, Polster BM, Loane DJ. Fundamental neurochemistry review: Microglial immunometabolism in traumatic brain injury. J Neurochem. 2023;167:129–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Arneson D, Zhang G, Ying Z, et al. Single cell molecular alterations reveal target cells and pathways of concussive brain injury. Nat Commun. 2018;9:3894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Harper MM, Rudd D, Meyer KJ, et al. Identification of chronic brain protein changes and protein targets of serum auto-antibodies after blast-mediated traumatic brain injury. Heliyon. 2020;6:e03374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wang M, Zhou C, Yu L, et al. Upregulation of MDH1 acetylation by HDAC6 inhibition protects against oxidative stress-derived neuronal apoptosis following intracerebral hemorrhage. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2022;79:356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lee S-M, Dho SH, Ju S-K, Maeng J-S, Kim J-Y, Kwon K-S. Cytosolic malate dehydrogenase regulates senescence in human fibroblasts. Biogerontology. 2012;13:525–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Suárez-Calvet M, Karikari TK, Ashton NJ, et al. Novel tau biomarkers phosphorylated at T181, T217 or T231 rise in the initial stages of the preclinical Alzheimer’s continuum when only subtle changes in Aβ pathology are detected. EMBO Mol Med. 2020;12:e12921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Johnson VE, Stewart W, Smith DH. Widespread τ and amyloid-β pathology many years after a single traumatic brain injury in humans. Brain Pathol. 2012;22:142–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Zanier ER, Bertani I, Sammali E, et al. Induction of a transmissible tau pathology by traumatic brain injury. Brain. 2018;141:2685–2699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Cole JH, Jolly A, de Simoni S, et al. Spatial patterns of progressive brain volume loss after moderate-severe traumatic brain injury. Brain. 2018;141:822–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Cole JH, Leech R, Sharp DJ; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative . Prediction of brain age suggests accelerated atrophy after traumatic brain injury. Ann Neurol. 2015;77:571–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Devoto C, Vorn R, Mithani S, et al. Plasma phosphorylated tau181 as a biomarker of mild traumatic brain injury: Findings from THINC and NCAA-DoD CARE consortium prospective cohorts. Front Neurol. 2023;14:1202967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Graham N, Zimmerman K, Heslegrave AJ, et al. Alzheimer’s disease marker phospho-tau181 is not elevated in the first year after moderate-to-severe TBI. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2024;95:356–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Cherry JD, Esnault CD, Baucom ZH, et al. Tau isoforms are differentially expressed across the hippocampus in chronic traumatic encephalopathy and Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2021;9:86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. McKee AC, Stein TD, Huber BR, et al. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE): Criteria for neuropathological diagnosis and relationship to repetitive head impacts. Acta Neuropathol. 2023;145:371–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Smith DH, Dollé J-P, Ameen-Ali KE, et al. COllaborative Neuropathology NEtwork Characterizing ouTcomes of TBI (CONNECT-TBI). Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2021;9:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Franz G, Beer R, Kampfl A, et al. Amyloid beta 1-42 and tau in cerebrospinal fluid after severe traumatic brain injury. Neurology. 2003;60:1457–1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Mondello S, Buki A, Barzo P, et al. CSF and plasma amyloid-β temporal profiles and relationships with neurological status and mortality after severe traumatic brain injury. Sci Rep. 2014;4:6446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Olsson A, Csajbok L, Ost M, et al. Marked increase of β-amyloid(1–42) and amyloid precursor protein in ventricular cerebrospinal fluid after severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurol. 2004;251:870–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]