Abstract

The neuropsychiatric syndrome of apathy is now recognized to be a common and disabling condition in Huntington’s disease. However, the mechanisms underlying it are poorly understood. One way to investigate apathy is to use a theoretical framework of normal motivated behaviour, to determine where breakdown has occurred in people with this behavioural disruption. A fundamental computation underlying motivated, goal-directed behaviour across species is weighing up the costs and rewards associated with actions. Here, we asked whether people with apathy are more sensitive to costs of actions (physical effort and time delay), less sensitive to rewarding outcomes, or both. Based on the unique anatomical substrates associated with Huntington’s disease pathology, we hypothesized that a general hypersensitivity to costs would underpin Huntington’s disease apathy.

Genetically confirmed carriers of the expanded Huntingtin gene (premanifest to mild motor manifest disease, n = 53) were compared to healthy controls (n = 38). Participants performed a physical effort-based decision-making task (Apple Gathering Task) and a delay discounting task (Money Choice Questionnaire). Choice data was analysed using linear regression and drift diffusion models that also accounted for the time taken to make decisions.

Apathetic people with Huntington’s disease accepted fewer offers overall on the Apple Gathering Task, specifically driven by increased sensitivity to physical effort costs, and not explained by motor severity, mood, cognition or medication. Drift diffusion modelling provided further evidence of effort hypersensitivity, with apathy associated with a faster drift rate towards rejecting offers as a function of varying effort. Increased delay sensitivity was also associated with apathy, both when analysing raw choice and drift rate, where there was moderate evidence of Huntington’s disease apathy drifting faster towards the immediately available (low-cost) option. Furthermore, the effort and delay sensitivity parameters from these tasks were positively correlated.

The results demonstrate a clear mechanism for apathy in Huntington’s disease, cost hypersensitivity, which manifests in both the effort and time costs associated with actions towards rewarding goals. This suggests that Huntington’s disease pathology may cause a domain-general disruption of cost processing, which is distinct from apathy occurrence in other brain disorders and may require different therapeutic approaches.

Keywords: Huntington’s disease, apathy, decision-making, effort, delay

Morris et al. show that Huntington’s disease apathy is underpinned by increased sensitivity to both physical effort and temporal decision costs when determining if a course of action is worth pursuing, suggesting a domain general alteration in cost processing underlying this behavioural disturbance.

Introduction

Seeking to maximize rewards whilst minimizing costs is a ubiquitous principal governing behaviour—apparent across the scala naturae. Evidence is growing that perturbations to this process underlie many behavioural disruptions that accompany disorders of the nervous system. One such behavioural disruption is apathy, characterized by an observable reduction in goal-directed behaviour.1,2 Apathy is highly prevalent in Huntington’s disease (HD), a genetic neurodegenerative disorder with marked motor, cognitive and psychiatric decline.3,4 Whilst there has been progress in understanding apathy across different brain disorders through leveraging our understanding of typical goal-directed behaviour, this remains incomplete. In particular in HD, a mechanistic account of apathy’s occurrence is lacking. This is of concern, given that in HD and more broadly apathy, is associated with reduced wellbeing and quality of life and predicts reduced functional independence and mortality.5-8 In the present work, we bring to bear the approach of probing disruptions of behaviour based on a model of normal goal-directed actions,9,10 applying this theoretical framework to investigate the effects of changing costs and rewards on decision behaviour in people with HD with apathy.

Current neuroscientific theories suggest that normal goal-directed behaviour is underpinned by a set of cognitive computations that subserve value-based decision-making.11 To decide if something is worth doing or not (or which option to choose), potential rewards and anticipated costs are integrated into a theorized subjective value signal, to drive behaviour towards a goal. Importantly, rewards (e.g. money, food, social approval) are devalued by the costs (e.g. effort, time, pain) associated with obtaining them—a phenomenon known as discounting (Box 1). Experimental manipulation of rewards and costs allows for quantification of individual sensitivity to these changing decision variables, of particular interest in trying to understand behavioural disruption—for example, why a person is not acting to pursue goals. People with apathy, across different brain pathologies, choose to do nothing more frequently than non-apathetic people—both in general life and in experimental paradigms that probe decisions about exerting physical effort for reward.12-15 Determining what drives this is of fundamental interest. Are apathetic people less incentivized by the rewards? Do they deem the effort too ‘costly’? Is it a combination of both? Apathetic people with Parkinson’s disease and small vessel disease show decreased incentivization by low levels of reward, both behaviourally and physiologically.13-17 In contrast, people with apathy in frontotemporal dementia,12 and to some extent individuals with small vessel disease,15 show increased aversion to effort costs. Thus, depending on the neural systems involved, distinct behavioural and computational signatures may underpin the frequent choice to do nothing.

Box 1. Core concepts.

Apathy: A reduction in goal-directed behaviour due to loss of motivation.

Impulsivity: A set of behaviours not limited to motor impulsivity: premature responses, poor behavioural inhibition, a tendency to act rashly; decisional impulsivity: preference for immediate reward, risk, sensation.

Goal-directed behaviour: Behaviours or actions performed to obtain or avoid particular outcomes. Action-outcome associations characterize goal-directed behaviour.

Value-based decision-making: A set of cognitive processes at the core of goal-directed behaviour, whereby the subjective values of potential rewards and associated costs are integrated, to generate the overall expected value of a course of action and its outcomes.

Effort-based decision-making: A type of value-based decision making, where the cost involved is effort (physical or cognitive).

Discounting: The decrease in subjective value of an outcome as costs to its attainment increase. ‘Delay discounting’ and ‘effort discounting’ refer to costs of time and effort devaluing rewards, respectively.

Binary choice tasks: Decision-making tasks where each offer consists of two options, and the decision-maker must choose one out of the two; also known as two-alternate forced-choice tasks

Drift diffusion model: A computational method to analyse binary choice tasks. Evidence towards selecting a particular option is thought to accumulate in a noisy manner in the brain. Parameters of drift rate, bias, threshold and non-decision time are modelled from subjects’ choices and decision times. Parameters are thought to reflect latent cognitive variables.

Latent cognitive variables: cognitive processes directly unobservable in raw behavioural data, but uncovered by modelling.

In HD, apathy has been associated with structural and functional changes in neural networks subserving value-based decision-making—the ventral striatum, anterior cingulate cortex, insula and ventromedial prefrontal cortex18—which are regions that have also been associated with apathy in other diseases.19,20 Additionally, bilateral amygdala atrophy is highly associated with apathy in people with HD, in whom white matter tracts connecting the amygdala with frontal regions are also often compromised.18,21 Intriguingly, the basolateral amygdala has been shown to play a role in the processing of several costs, including effort and time,22-25 suggesting a generalized role in processing behavioural costs, unlike some cortical regions which appear to be cost-specific.26-28 This raises the question of whether disrupted cost-reward processing at a subcortical level may give rise to a behavioural ‘cost-general’ sensitivity in HD apathy. Alternately, as is the case in many previous apathy studies,13-17 altered reward processing may be the key driver of this behavioural change.

Behaviourally, very few HD studies have systematically examined value-based decision-making as a function of disrupted motivation. Existing signatures suggest reward insensitivity may be less of an issue in HD, with work in premanifest and manifest HD pointing towards increased sensitivity to cognitive (although not physical) effort, compared to healthy controls.29,30 Whilst this provides some evidence for altered effort cost computation in HD, none of the participants in that study were reported to be apathetic. Another investigation found no differences between people with and without apathy in HD on a task of physical effort (depressing a spacebar) for reward,31 albeit with important caveats related to the experimental paradigm which did not systematically vary effort costs and rewards, rendering it difficult to tease apart the effects of each on behaviour. In a risk-reward task, people with HD selected more high-reward options compared to controls despite the higher risk associated,32 suggesting insensitivity to risk cost, but how this relates to apathy was not investigated. In summary, the extant (scant) evidence points to altered cost sensitivity, rather than decreased reward sensitivity in HD, but whether apathetic people evaluate physical effort costs to be ‘more costly’ is not known. Furthermore, if a generalized neural cost-network disruption is key in HD apathy, costs other than physical effort which are integrated for behavioural decision-making may also be affected. One important cost for behaviour is time to obtain a goal. However, to the best of our knowledge, no study has examined whether people with HD who show intolerance to delay also show increased sensitivity to physical effort or how both these costs relate to apathy.

While the choices people make allow important inferences to be made about processing of reward and cost information, the time taken to make these decisions is also a crucial variable that can yield insights about value integration. A combined analysis of choices made and decision times can be achieved using a drift diffusion model.33 This assumes that evidence accumulates in a noisy manner towards a threshold corresponding to a decision. The model parameters capture latent, or unobservable, cognitive processes and thus relate behavioural data more closely to the neurophysiological processes hypothesized to underlie it.34 One such parameter, the drift rate, was recently shown to be altered in people with apathy in the setting of small vessel disease.15 In addition to reduced incentivization by reward in their raw choice data, the drift rate was slower as a function of changing reward but not effort, which correlated with white matter degradation in apathy networks. However, to date, drift diffusion analysis has not yet been applied to HD apathy. Here, using two separate tasks, we use drift diffusion modelling to investigate how the costs of physical effort and time delays are integrated with reward in decision-making in HD apathy.

Overall, in this study we asked: is cost and/or reward processing in value-based decisions altered in people with HD with apathy? Specifically, we wanted to determine whether reduction in behaviour observed in HD apathy is related to increased sensitivity to effort and/or time costs, decreased sensitivity to rewards, or both. To answer this, we used value-based decision-making tasks with two types of costs: physical effort exertion and time delay to reward receipt. Participants with HD and healthy controls performed an effort-based decision-making task (Apple Gathering Task, AGT) and a delay discounting task (Money Choice Task). We hypothesized that apathetic people with HD would have (i) increased sensitivity to effort costs, rather than reduced sensitivity to reward; (ii) increased sensitivity to time costs, as part of a cost-general aversion; or (iii) a common cost sensitivity, such that effort and time costs would be positively associated.

Materials and methods

Ethics

The study was approved by the Health and Disability Ethics Committee of the New Zealand Ministry of Health (21/CEN/242) and the local ethics committee in Oxford, UK. Written consent was obtained from all subjects in accordance with the New Zealand National Ethical Standards and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Participants

People with confirmed expansion of the Huntington’s gene (premanifest to mild motor manifest disease; n = 53) were recruited from three specialist HD clinics (Auckland and Christchurch, New Zealand; Oxford, UK) between 2015–17 (UK) and in 2022 (NZ). Exclusion criteria included motor disease too advanced to voluntarily squeeze a hand-held dynamometer or cognitive impairment to the degree of inability to provide informed consent to take part in the study. Age and gender matched controls (n = 39) with no history of neurological or psychiatric illnesses (other than mild depression) were recruited via local databases in Christchurch, New Zealand and Oxford, UK. Participants performed a battery of behavioural tasks, two of which are presented in this paper (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Study participants. (A) Flow chart of study participants. Owing to site test battery differences, not all participants completed the delay discounting task. (B) Age and (C) motor disease severity of Huntington’s disease participants, split by apathy status. UHDRS-TMS = Unified Huntington’s Disease Rating Scale Total Motor Score.

Disease, cognitive and questionnaire measures

Apathy was assessed at both sites using the Apathy Evaluation Scale–self report version (AES).35,36 Additionally, the short Problem Behaviours Assessment (sPBA)–apathy subscale and the Lille Apathy Rating Scale (LARS) were administered in New Zealand and Oxford, respectively.37,38 In line with previous work, people were classified as apathetic if their self-reported AES score was ≥37, the clinician-rated sPBA score was ≥2 or the LARS was ≥ −21, indicating at least mild-moderate apathy.13,39,40 Motor disease severity was assessed using the Unified Huntington’s Disease Rating Scale Total Motor Score (UHDRS-TMS) by an experienced neurologist (T.A., R.R. or C.L.H.)41 (Fig. 1B and C). Cognition was screened using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment or a Mini-Mental State Examination-conversion equivalent in New Zealand and the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination-Revised (ACE-R) in Oxford.42,43 To enable comparison across sites, cognition scores were z-scored using previously published normative data for each tool.44,45 Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II).46 Because some elements of the BDI-II probe motivational changes that overlap with apathy, a subscore excluding these items was calculated (dysphoria subscale), using previously validated methodology.47 Quality of life was evaluated by a Cantril ladder, which consists of a visual scale of 1–10.48 Impulsivity was assessed using the UPPS-P Impulsive Behaviour Scale.49 Impulsivity scores were available for a subset of participants only (HD n = 40, controls n = 19). Demographic and clinical data were analysed in R50 using one-way ANOVA tests, and where necessary, Tukey’s honestly significant difference tests.

Effort-based decision-making paradigm: Apple Gathering Task

Effort-based decision-making was assessed using a validated task previously used to study apathy in other patient populations—the AGT. Participants were presented with sequential offers to exert effort for reward and had to decide whether to accept or reject each offer. Offers were presented in the form of a cartoon apple tree, with reward being the number of apples on the tree, each worth some money. A yellow bar on the apple tree trunk indicated the effort required to obtain the reward; the higher the bar on the trunk, the more effort required. ‘Effort’ was exerted via squeezing an individually calibrated hand dynamometer (Vernier, HD-BTA and SS25LA, Biopac Systems). The effort levels ranged from 10% to 80% of each participant’s maximal voluntary contraction. Reward and effort levels were systematically combined, and the resultant conditions were sampled evenly in a pseudo-randomized order across blocks. A version of the task with five reward and effort levels (1, 3, 6, 9 and 12 apples; 10%, 27.5%, 45%, 62.5% and 80% effort), resulting in 25 combinations over five blocks (125 trials), was used in New Zealand (see Saleh et al.51 for a similar structure). A six-by-six version of the task was used in Oxford [1, 3, 6, 9, 12 and 15 apples; 10%, 24%, 38%, 52%, 66% and 80% effort; 36 combinations; six blocks (180 trials)].13 Prior to task commencement, participants practiced exerting all force levels. In addition, the first block was a practice block, to ensure participants fully comprehended the task and were engaging adequately. To reduce the potential effects of fatigue, the response side was varied between left and right hands, indicated after offer acceptance. Participants were also allowed to rest between each block of trials (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

The Apple Gathering Task in Huntington’s disease. (A) The Apple Gathering Task. Levels of physical effort (squeezing a handheld dynamometer) and reward (apples, worth money) are varied; here we show 25 combinations of effort and reward, for each of which participants must decide if the reward is worth the effort. Participants in the UK performed a six-by-six version of this task, not shown. (B) Overall, apathetic participants with Huntington’s disease (HD) accepted fewer offers than their non-apathetic counterparts and control participants. (C) Proportion of offers accepted varied as a function of the effort and (D) reward on offer. (E) Model parameter estimates capturing overall tendency to accept (intercept), and effects of changing reward and effort levels. Apathetic people showed greater change in behaviour as effort, but not reward, varied, compared to non-apathetic people. (F) Difference in acceptance between people with and without apathy was in the high effort space. (G) All participants reached target effort levels when exerting effort, and (H) choice behaviour did not differ significantly across task blocks. (I) Decision times did not differ by apathy status in HD. Controls had shorter decision times than people with HD. New Zealand (NZ) data only are shown in G and H for graphical purposes. Error bars show standard error of the mean. MVC = maximum voluntary contraction. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Apple Gathering Task statistical analysis

Data were analysed in R.50 Decision times <0.4 s were regarded as accidental squeezes and removed prior to choice analyses. The effort term was squared for all analyses because of previous work demonstrating a quadratic relationship between perceived effort and effort requirements.52,53 Reward and effort levels were z-scored. The proportion of choices accepted overall was computed for each person and compared between groups using a one-way ANOVA. A generalized linear mixed effects model was fitted to choice data (accept or reject), to investigate the log-odds (logit) of choice behaviour. Reward, effort, apathy and their interactions were included as fixed effects. Our random effects structure allowed the slope of reward and effort to vary for each person, allowing us to extract individual reward and effort sensitivity metrics from the model output. This approach reduced both the Akaike information criterion (AIC, Δ 845) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC, Δ 811) when compared to a model with only subject as a random effect. Adding covariates to the model did not significantly improve model fit, so the chosen model did not include them. Because participants from the UK site performed a version of the AGT with six levels of reward and effort, a solution was required to move their decisions into a common space with the New Zealand (five-by-five) data. To enable this comparison, choice data were affine-transformed within the generalized linear mixed effects model by adding site as a fixed effect and the interactions of site with reward and effort. This enabled a shift in centroid and change in scale of the decision matrices, allowing for estimation of model parameters within a common decision space.

| (1) |

To investigate other factors which may influence effort and reward sensitivity, we fitted multiple regression models to the individual effort and reward slopes extracted from the main model. These models included the variables apathy, dysphoria, motor disease severity, cognition, medication usage, age and sex.

Delay discounting task

We used the Money Choice Questionnaire, which consists of 27 hypothetical choices.54 Each choice has two options—a smaller monetary reward available immediately or a larger monetary reward available after a delay. Monetary values and delays are varied for each option (range, monetary reward: $11–$85; delay in days: 0–186). To additionally capture decision times, we computerized this questionnaire using PsychoPy.55 Choices appeared one by one on a screen, and participants selected the smaller-sooner or larger-later option for each using the left and right arrow keys, respectively. Four practice questions were added but excluded from analyses, and task completion took approximately 2–5 min.

Statistical analysis of the delay discounting task

To determine each person’s overall choice behaviour, we computed the proportion of delayed choices made, in line with previous work.56 Thus, a steeper discounter would have a lower proportion of delayed choices, and a shallower discounter would have a higher proportion. An individual discounting parameter per participant, computed using R code from Gray et al.,57 was highly correlated with proportion of delayed choices made (r = 0.98, P < 0.0001), so we used the simpler proportion delayed choices metric. We were also interested in choice behaviour across different offers. To this end, we calculated the k (offer value) associated with each question, as per Mazur’s (1987) hyperbolic equation and fitted a generalized linear mixed effects model (glmer in R, logit) to HD choice data. Predictors were (z-scored) log(k), apathy, and their interaction, with subject as a random effect.

| (2) |

To investigate other factors which may influence choice, we fitted a multiple regression model to individual proportion of delayed choices. This model included variables apathy, dysphoria, motor disease severity, cognition, medication usage, age and sex.

Hierarchical drift diffusion modelling

The drift diffusion model estimates four parameters: threshold (a, the distance between the two options, for example, ‘accept’ or ‘reject’), bias (z, the starting point of evidence accumulation), non-decision time (t, information encoding and response execution time) and drift rate (v, the rate of evidence accumulation to reach a threshold, or more simply, the speed and direction of evidence accumulation).58 For the Apple gathering and delay discounting tasks, a drift diffusion model toolbox—hddm version 0.8.059 implemented in Python 3.8 was used to fit models to the data. Five Markov chain Monte Carlo chains were run, with 10 000 samples, with the first 5000 discarded as burn-ins. Model convergence was checked using the Gelman-Rubin statistic (R-hat values) and visualization of trace plots (Supplementary Figs 1 and 2 and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Probability distributions were generated, providing a measure of uncertainty for each parameter estimate. Separate simple models were fitted, examining parameters between controls and those with HD and then those with HD with and without apathy. Finally, to investigate any drift rate differences between those with and without apathy in HD as a function of changing task variables, we fitted regression models with drift rate as the outcome variable. For the AGT, fixed effects of effort and reward were included, and for the Money Choice Questionnaire, a fixed effect of offer k-value. Group-wise comparisons between parameters were conducted using Bayesian hypothesis testing.

Finally, we reanalysed both tasks using impulsivity scores (for the subset of HD participants with impulsivity scores, n = 40) to determine whether the behavioural signatures were specific to apathy or generalized to other disturbances of goal-directed behaviour.

Results

Clinical and demographic results

Overall, 24 (45%) people with HD scored above clinical cut-offs for apathy. Motor disease severity did not significantly differ between those with and without apathy [F(1,37) = 1.2, P = 0.29]. There were significantly more males in the HD apathy group compared to the other groups (χ2 = 13.8, P = 0.001). There were no significant differences in education between those with and without apathy, but controls had significantly higher education than the HD apathy group [HD apathy versus HD no apathy: mean difference = 1.2, 95% confidence interval (CI) (−0.78, 3.14), P = 0.33; HD apathy versus controls: mean difference = 2.7, 95%CI (0.87, 4.58), P = 0.002; HD no-apathy versus controls: mean difference = 1.5, 95%CI (−0.21, 3.3), P = 0.1].

A one-way ANOVA revealed significant differences in the BDI II dysphoria subscale. This was driven by higher scores in the HD apathy group [HD apathy versus HD no apathy: mean difference = 4.5, 95%CI (−7.8, −1.2), P = 0.004; HD apathy versus controls: mean difference = 5.0, 95%CI (−8.1, −1.9), P = 0.0007; HD no apathy versus controls: mean difference = 0.5, 95%CI (−3.4, 2.4), P = 0.9]. Quality of life also differed significantly, with the HD apathy group having lower scores on a Cantril ladder compared to the HD no apathy group [HD apathy versus HD no apathy: mean difference = 1.2, 95%CI (0.1, 2.2), P = 0.02; HD apathy versus controls: mean difference = 0.8, 95%CI (−1.9, 0.3), P = 0.2; HD no apathy versus controls: mean difference = 0.3, 95%CI (−0.8, 1.4), P = 0.8].

In HD, whilst there were no significant differences in antidepressant usage (P = 0.09), more people with apathy were taking antipsychotics (HD no apathy: n = 4/29, HD apathy: n = 7/24, P = 0.03). Only one participant with HD was taking tetrabenazine. In the subset of HD participants (NZ cohort: n = 36 and UK cohort n = 4: Total n = 40) with impulsivity scores, apathy (AES scores) and impulsivity (UPPS-P scores) were significantly correlated (r = 0.53, P = 0.0005). Demographic and clinical data are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant demographic, clinical and behavioural characteristics

| Controls | HD no-apathy | HD apathy | Statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants | n = 39 | n = 29 | n = 24 | |

| Site | ||||

| Oxford | n = 19 | n = 9 | n = 8 | – |

| New Zealand | n = 20 | n = 20 | n = 16 | – |

| Age | 53 (15) | 51 (13) | 50 (14) | F(2,88) = 0.24, P = 0.79 |

| Male: Female, % male | 15:23 (65%) | 9:20 (31%) | 19:5 (79%) | χ2(2, n = 91) = 13.8, P = 0.001 |

| Education, years | 16.5 (2.8) | 14.9 (2.5) | 13.8 (3.8) | F(2,88) = 6.4, P = 0.003 |

| UHDRS total motor score/124 | NA | 10.8 (12.3) | 14.9 (11) | F(1,37) = 1.2, P = 0.29 |

| Medication | ||||

| Antidepressant use (%) | 3 (8%) | 8 (28%) | 11 (46%) | χ2(2, n = 91) = 4.7, P = 0.09 |

| Antipsychotic use (%) | 0 | 4 (14%) | 7 (29%) | χ2(2, n = 91) = 7.1, P = 0.03 |

| Tetrabenazine | NA | 1 | 0 | – |

| Mood and behaviour | ||||

| Apathy Evaluation Scale/72 | 28 (8.5) | 27 (5.5) | 39 (9.4) | F(2,87) = 18.5, P < 0.0001 |

| BDI II/63 | 5.6 (5.6) | 6.5 (4.9) | 14.8 (12.7) | F(2,87) = 10.8, P < 0.0001 |

| BDI II dysphoria subscale/33 | 2.3 (3.2) | 2.8 (2.6) | 7.4 (8.4) | F(2,87) = 8.2, P = 0.001 |

| Impulsivity UPPS-P/236a | 116 (24) | 121 (21.9) | 132 (18.5) | F(2,56) = 2.8, P = 0.07 |

| Quality of life | ||||

| Cantril ladder/10 | 7.8 (1.5) | 7.8 (1.3) | 6.6 (2) | F(2,86) = 4.7, P = 0.01 |

| Cognitionb | ||||

| MoCA/30 | 27.8 (2) | 27.1 (2.9) | 26.6 (5.1) | F(2,52) = 0.56, P = 0.58 |

| ACE-R/100 | 96.6 (2.4) | 89.1 (6.3) | 84.6 (12.4) | F(2,30) = 9.9, P = 0.0005 |

ACE-R = Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination Revised; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment; UHDRS = Unified Huntington’s Disease Rating Scale.

aNot all participants had UPPS scores.

bCognitive screening tests between sites differed. Participants from Oxford performed the ACE-R whilst those from New Zealand performed the MoCA.

Physical effort discounting: the Apple Gathering Task

Apathetic people with Huntington’s disease accepted fewer offers overall

A one-way ANOVA of overall acceptance rates between the three groups was significant [F(2,88) = 7.8, P = 0.0007]. Post hoc testing revealed that people with HD with apathy accepted significantly fewer offers than HD participants without apathy [mean difference 0.13, 95%CI (0.03, 0.24), P = 0.007] and controls [mean difference = 0.2, 95%CI (0.06, 0.3), P = 0.0008]. There was no significant difference between those without apathy and controls [HD no-apathy versus controls: mean difference = 0.02, 95%CI (−0.07, 0.1), P = 0.84]. This effect remained after controlling for dysphoria [F(2,86) = 6.47, P = 0.002] (Fig. 2B).

Heightened effort sensitivity in Huntington’s disease apathy

To investigate the factors leading to reduced acceptance of offers by those with apathy, a generalized linear mixed effects model was fitted to the HD choice data (see the ‘Materials and Methods’ section). There was a main effect of apathy on choice behaviour (ꞵ = −1.1, z = −2.6, P = 0.009). Furthermore, the interaction of effort and apathy was significant (ꞵ = −0.6, z = −2.3, P = 0.02), but not that of reward and apathy (ꞵ = 0.1, z = 0.1, P = 0.9), suggesting that the reduced acceptance of offers in those with apathy was driven by differences in sensitivity to changing effort rather than changing reward. Specifically, those with apathy accepted fewer offers as effort levels increased (Fig. 2C–F).

The three-way interaction term for reward, effort, and apathy was not significant (ꞵ = −0.1, z = −1.4, P = 0.2). Main effects of both reward (ꞵ = 4.8, z = 9.3, P < 0.0001) and effort (ꞵ = −2.2, z = −7, P < 0.0001) were present, such that an increasing reward predicted increasing acceptance of offers whereas increasing effort predicted reduced acceptance of offers. The interaction between reward and effort was also significant (ꞵ = 0.4, z = 2.6, P = 0.01). Importantly, there was no main effect of site (ꞵ = −0.3, z = −0.3, P = 0.7).

To ensure the apathy relationship with choice metrics was not driven by other factors, multiple regression models were fitted to individual effort and reward sensitivity parameter estimates from the model, with predictors of apathy, dysphoria, motor disease severity, cognition, medication usage, age and sex. Increased effort sensitivity and apathy retained a significant association (ꞵ = −0.7, t = −2.9, P = 0.007), after controlling for these factors. Additionally, antipsychotic usage was associated with reduced effort sensitivity (ꞵ = 1.8, t = 2.7, P = 0.01; Supplementary Fig. 3). No other covariates predicted effort sensitivity. There were no significant predictors of reward sensitivity.

Control analyses

To investigate whether fatigue influenced choice behaviour, we examined the proportion of choices accepted per block using linear regression models. There were no significant main effect of block (ꞵ = 0.008, z = 0.12, P = 0.91) and the interaction between block and apathy was not significant (block × apathy: ꞵ = −0.007, z = −0.1, P = 0.9). All participants reached the required effort levels of the task, and modulated their effort exertion according to the target effort level (effort: ꞵ = 0.2, t = 63.9, P < 0.0001). There was no difference in force production across effort levels in HD as a function of apathy, but controls exhibited greater accuracy to target effort levels (effort × controls: ꞵ = 0.03, t = 7.8, P < 0.0001; Fig. 2G and H and Supplementary Fig. 4).

Decision time: Apple Gathering Task

Across all participants, a one-way ANOVA of individual mean decision times was significant [F(2,88) = 12.7, P < 0.0001]. Post hoc testing revealed the difference to be driven by shorter decision times in controls. Of note, there was no significant difference in decision times between those with and without apathy in HD [Controls versus HD apathy: mean difference = 0.7 s, 95%CI (−1.1, −0.3), P < 0.0001; Controls versus HD no-apathy: mean difference = 0.6 s, 95%CI (−0.9, −0.2), P = 0.0008; HD apathy versus HD no-apathy: mean difference = 0.2 s, 95%CI (−0.5, 0.2), P = 0.62; Fig. 2I].

Drift diffusion modelling: Apple Gathering Task

Next, drift diffusion models were fitted to decision time and choice data, to examine the integration of cost-reward information when making value-based decisions. Overall, baseline drift rate (v) was higher in controls compared to HD [P denotes Bayesian probability of different distributions; P(Controls > HD) = 0.99], meaning that control participants accumulated evidence faster towards a decision bound than those with HD. The threshold parameter (a) was lower in controls [P(Controls < HD) = 0.99], corresponding to a shorter distance between bounds. The bias parameter (z) was higher in controls [P(Controls > HD) = 0.99], with a value greater than 0.5, suggesting that controls had a small bias towards accepting offers irrespective of their value, whereas mean bias in HD was 0.5 (no bias towards acceptance/rejection). The non-decision time parameter (t) was smaller in controls, reflecting overall greater processing time in HD, irrespective of task values [P(Controls < HD) = 0.99]. In summary, people with HD accumulated evidence more slowly, needed more evidence before reaching a decision and took longer to encode information and execute responses.

We next examined differences in drift diffusion model parameters within people with HD, to test our apathy-specific hypotheses. There was no evidence for differences in threshold, bias, or non-decision time parameters as a function of apathy. However, overall drift rate (to a decision threshold) was slower in HD apathy [P(Apathy < No-apathy) = 0.99; Fig. 3A–D]. To explore the drivers of altered drift rate as a function of apathy in HD, the effects of changing effort and reward levels on drift rate were examined using a regression model, in which the trial by trial effect of changes in these task metrics on drift rate were estimated. Baseline drift rate (intercept) was significantly lower in HD apathy [P(Apathy < No-apathy) = 0.99]. Changing effort and reward levels had the same effect on drift rate direction in people with and without apathy; effort towards the negative (reject) bound, and reward towards the positive (accept) bound, respectively. However, there was moderate evidence that people with apathy accumulated evidence faster towards rejecting an offer as effort costs increased compared to those without apathy [P(Apathy > No-apathy) = 0.94], in line with the effect of effort on choice. In contrast, there was no significant evidence that the reward’s effect on drift rate varied as a function of apathy [P(Apathy > No-apathy) = 0.87]. There was also no effect of apathy on the interaction between effort and reward affecting drift rate [P(Apathy > No-apathy) = 0.54; Fig. 3F]. Thus, although apathetic people had an overall slower drift rate, this was not simply a reflection of increased noise or speed-accuracy trade-off, as in fact as effort costs increased, apathetic people accounted for effort in a more sensitive manner than non-apathetic people.

Figure 3.

Drift diffusion model outputs from the Apple Gathering Task. Per subject parameter estimates from a drift diffusion model, showing probabilities from hypothesis testing between participants with Huntington’s disease (HD) and controls, and HD apathy versus no-apathy, for (A) drift rate, (B) threshold, (C) non-decision time and (D) bias. (E) An illustration of the drift diffusion model parameters. (F) Regression model parameter estimates of the drift rate intercept, the effects of changing reward and changing effort on drift rate, and their interaction, in HD. In people with apathy compared to people without, drift rate overall was slower, but increased as a function of increasing effort. Error bars show standard error of the mean. E re-used with permission from Saleh et al.15.

Delay discounting task

Altered response to changing offer value in Huntington’s disease apathy

A generalized linear mixed effects model fit to trial-by-trial choice data in people with HD showed that response to offer value differed as a function of apathy [log(k) × Apathy: β = −0.4, z = −2.5, P = 0.01]. Whilst all participants adjusted their behaviour as offer values changed, people with apathy remained more likely to select the smaller-sooner options as the value of the delayed option increased. There was a main effect of offer value (β = 2.4, z = 14.3, P < 0.0001). There was no significant main effect of apathy (β = −0.42, z = −0.9, P = 0.37) (Fig. 4A–C). A multiple linear regression model showed no other variables predicted choices made.

Figure 4.

Delay discounting task and results. (A) Delay discounting task, in which participants are offered choices between smaller-sooner or larger-later monetary rewards. Whilst it is not possible to disentangle sensitivity to delay and reward in this task, each offer has a numeric value associated; choice behaviour changes as this number increases. A computerized version was used, to additionally capture decision times. (B) No significant difference between groups in overall proportion of delayed choices made. (C) As delay to reward increased, people with apathy selected more immediate options, compared to those without apathy and controls. Inset depicts modelled choice behaviour. (D) Mean decision times did not differ in Huntington’s disease (HD) as a function of apathy. (E) Drift diffusion regression model parameter estimates, showing baseline drift rate (intercept), and drift rate as a function of changing offer value, with a trend towards faster evidence accumulation towards the lower bound (smaller-sooner option) in HD apathy overall. Error bars show standard error of the mean. **P < 0.01.

Drift diffusion models: delay discounting task

There was a significant difference in mean decision times between groups [F(2,53) = 8.1, P = 0.0008]. Post hoc testing revealed this to be driven by shorter mean decision times in controls compared to HD no-apathy [Control versus HD no-apathy: mean difference = 2.5, 95%CI (−4, −1), P = 0.0005; Control versus HD apathy: mean difference = −1.1, 95%CI (−2.7, 0.6), P = 0.26; HD apathy versus HD-no apathy: mean difference = 1.4, 95%CI (−0.2, 3), P = 0.1; Fig. 4D].

A regression model in HD showed moderate evidence for differences in drift rate intercepts for HD apathy and no-apathy groups [P(HD apathy < HD no-apathy) = 0.94]. Apathetic people drifted faster towards the lower bound (immediate option), compared to non-apathetic people, although there was much individual variability. Drift rate did not vary between groups as a function of offer value, [P(HD apathy > HD no-apathy) = 0.65; Fig. 4E and Supplementary Fig. 5]. In summary, the tendency for apathetic people to choose the smaller-sooner option in the face of increasing delay costs was reflected in a model of their evidence accumulation, whereby they drifted faster towards this immediate option across all offer values.

Common cost sensitivity across tasks

To test our hypothesis that people with HD apathy would show cost-general sensitivity, we next examined whether individual effort and delay cost sensitivity across decision-making tasks was related. Individual effort sensitivity parameter estimates from the AGT and overall proportion of delayed choices per person on the delay discounting task, were correlated in participants with HD (r = 0.36, P = 0.036). That is, those more sensitive to effort costs were also more sensitive to increasing delay costs (Fig. 5). The proportion of delayed choices was not significantly correlated with AGT reward sensitivity parameter estimates (r = 0.15, P = 0.27).

Figure 5.

Cost sensitivity in Huntington’s disease. Effort sensitivity (Apple Gathering Test) and proportion delayed choices (delay discounting task) showed significant correlation in Huntington’s disease (HD). For graphical purposes we show proportion immediate choices on the x-axis and reverse-coded effort sensitivity on the y-axis.

Cost sensitivity not associated with Huntington’s disease impulsivity

We re-ran the behavioural task analyses for the subset of people with UPPS-P impulsivity scores, to determine whether behavioural findings were unique to apathy or reflected a broader goal-directed behaviour disruption. Impulsivity was not significantly associated with choice behaviour on the effort-based or delay discounting decision-making tasks [AGT: F(1,38) = 0.23, P = 0.64; delay discounting: F(1,34) = 2.6, P = 0.1]. Thus, despite being correlated with apathy, impulsivity did not show the same behavioural signatures as loss of motivation on our value-based decision-making tasks.

Discussion

Goal-directed behaviour is characterized by the weighing up of rewards (outcomes) and the associated costs of actions to obtain them, with changes in either of these parameters potentially leading to behavioural disruption. To determine the cognitive mechanisms giving rise to apathy in HD we investigated the influence of changing costs and rewards on behaviour, using an effort-based decision-making task and a delay discounting task. People with apathy accepted fewer offers of physical effort for reward, driven by increased sensitivity to increasing effort costs, despite no physical differences in force production. This was evident both in their choice behaviour and modelled decision drift rate—a metric hypothesized to reflect neural evidence accumulation. On a delay discounting task apathy was associated with choices consistent with increased delay sensitivity, which again was reflected in the modelled rate of evidence accumulation. Furthermore, effort and delay sensitivity were significantly correlated in HD. Our results suggest a distinct cognitive mechanism of cost general hypersensitivity may underlie apathy in HD, explaining this common behavioural phenotype. This contrasts to many other neurological conditions, in which apathy is driven mainly by reduced incentivization by rewards, meaning that different therapeutic approaches to apathy may be required in people with HD.

Increased physical effort sensitivity in Huntington’s disease apathy

Consistent with our hypothesis, we found evidence that increased sensitivity to physical effort costs underlies the behavioural change in HD apathy, rather than reduced incentivization by rewards. Previous HD studies found no differences in physical effort sensitivity compared to healthy controls, but did not directly compare effort sensitivity between people with HD with and without apathy.29,30 Increased physical effort sensitivity has previously been associated with apathy, in the setting of frontotemporal dementia.12 Apathy in small vessel disease, too, has been associated with effort aversion at high effort levels and also with reduced reward sensitivity, with white matter changes in tracts linking key nodes underpinning value-based decision-making hypothesized to mediate this finding.15 In contrast, Parkinson’s disease apathy has been associated with reduced incentivization by reward, both behaviourally and on measures of autonomic arousal,14,17 with associated structural and functional alterations to reward-associated neural networks, including the ventral striatum (and nucleus accumbens).60-62 Thus, across brain diseases, although the observable behaviour expressed is apathy, cost-reward decision variables are affected in different ways.

Drift diffusion computational models are thought to closely represent the neurophysiological mechanisms that underlie decision-making.63 Our results using these methods provide further evidence for altered effort, rather than reward, sensitivity in HD apathy. Drift rate in HD apathy increased with changing effort levels, leading to a faster drift rate towards the ‘no’ bound, suggesting that effort information in particular was weighted more strongly. In addition, the cost-reward integration process was slower overall as a function of apathy, shown by a slower drift rate on the AGT, despite no difference in decision times. Previous work has also shown a slower overall drift rate in apathetic people with small vessel disease, in association with white matter degradation in apathy-relevant networks.15 Whilst a slower drift rate could reflect increased noise due to systems-level neural degeneration in key valuation circuits, decreased quality of evidence provided by incoming sensory circuits, or a combination of these, the faster drift rate with changing effort in HD apathy points to altered processing of specific information, rather than simply a more noisy system. On delay-reward choices, apathetic people also had a faster overall drift rate towards the immediately available option, again showing alteration in cost processing. A key next step will be finding neural evidence of these behaviourally derived metrics.

A cost-general mechanism underlying apathy in Huntington’s disease

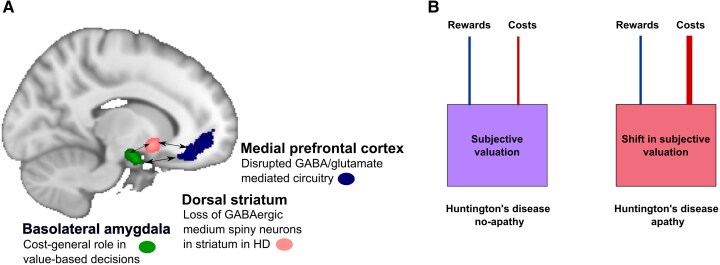

We show preliminary behavioural evidence for a cost-general hypersensitivity in HD apathy. Although previous work has shown the neural underpinnings of effort and time cost processing can be dissociated,26,27 these decision variables are also thought to be integrated within a common pathway, in which the basolateral amygdala is a key hub.23-25 The co-occurrence of shifts in effort and temporal cost processing, associated with apathy in HD, points more strongly to a cost-general processing disruption occurring secondary to HD pathology. A potential mechanism underlying these behavioural findings may be disruption to the amygdala-frontal network. The basolateral amygdala has reciprocal connections with medial frontal cortex, mediated by GABAergic/glutamatergic projections,64 and this connectivity is implicated in the expression of goal-directed behaviour.65,66 HD is characterized histopathologically, at least initially, by selective loss of GABAergic medium spiny neurons in the dorsal striatum, disrupting the excitatory-inhibitory balance.67 In HD, circuitry imbalances result in incomplete inhibition of movement, with choreiform movements emerging. Causal models of behavioural changes in HD are less clear. Which non-motor features emerge due to incomplete inhibition? Fronto-striatal circuitry changes are evident prior to, and in manifest HD,68,69 and the amygdala is associated with HD apathy,18 but the motivational sequelae of disrupted amygdala-medial prefrontal cortex connectivity in HD have not been elucidated. Given the cost-general role of the amygdala in value-based decisions,23-25,70,71 alterations to this mechanism would predict a cost-general sensitivity, in line with our behavioural findings (Fig. 6). One caveat is that whilst our physical effort task required actual effort exertion, our delay discounting task was hypothetical, and future work using a binary experiential delay discounting task, which can dissociate the effects of delay and reward, is needed (which may need to be created, given the intricacies of evaluating time as a cost).

Figure 6.

Theoretical model of cost sensitivity in Huntington’s disease apathy. A proposed theoretical model of mechanisms leading to apathy in Huntington’s disease (HD). (A) Loss of medium spiny neurons in the dorsal striatum may lead to altered GABA/glutamate balance, affecting frontal cortical—amygdala functional connectivity, with resultant increased amygdala activation. (B) Cost information may be weighted more heavily, in cost-reward integration, leading to a shift in threshold of costs deemed worth expending for reward, expressed as reduced goal-directed behaviour. This theoretical model is based on knowledge of Huntington’s disease neuropathology, previous rodent work, and our behavioural findings, and it remains to be empirically tested.

Cost sensitivity specific to apathy

Despite a significant positive association between apathy and impulsivity in people with HD, choice behaviours were dissociable. Apathy was associated with increased sensitivity to decision costs, whereas impulsivity was not associated with choice behaviour on either task. This is an interesting finding given previous associations between impulsivity and delay sensitivity—albeit in non-HD contexts.72 Future research is needed to investigate the cognitive changes underpinning impulsivity in HD in more detail.

Clinical implications

Whilst it is fairly intuitive that effort hypersensitivity may underpin an apathetic phenotype, it is perhaps less so for delay hypersensitivity. Why should an aversion to waiting for future rewards lead to reduced goal directed behaviour? Many goals in real life are temporally distant and often require achievement of multiple sub-goals to realize them. Hypersensitivity to delay costs would make people less likely to engage in pursuit of these goals that are distant in time—with this lack of engagement manifesting as apathy. These findings have implications for potential treatment strategies for apathy occurring in the context of HD, which may differ from other neurological conditions in which changes in reward sensitivity is a more dominant contributor.13,16,17 Cognitive-behavioural strategies to reduce the perception of costs by, for example, focusing attention on rewarding outcomes may hold promise for HD apathy. Pharmacologically, the link between both encoding of effort costs and mobilization of effort and the noradrenergic system suggests that measures modulating this are worth exploring.73,74 Considering delay hypersensitivity, in rodents serotonergic agonists have been associated with increased willingness to wait.75,76 However, serotonergic manipulations in humans have been associated with mixed effects on motivation.77 Ultimately, determining the specific disruptions in goal-directed behaviour underlying loss of motivation in an individual may be an important step towards directing appropriate choice of treatment.

Potential confounding factors

It is important to consider potential confounding factors which may influence choice behaviour in HD. To control for differences in grip strength, the physical effort tasks’ requirements were calibrated for each individual, enabling all participants to reach target effort levels, which they did. Furthermore, fatigue was not an apparent driver of effort hypersensitivity, given that our analysis of acceptance rates across the task blocks showed no differences in choice behaviour. Antipsychotics, as well as tetrabenazine, broadly dampen down the dopaminergic system, typically associated with less willingness to exert effort for reward.78,79 Theoretically, this could explain our effort sensitivity result, rather than apathy. However, we found that people with HD taking antipsychotic medications (only one participant was taking tetrabenazine) were ‘less sensitive’ to changing effort costs on the AGT, precluding this as an explanation for increased effort sensitivity in HD apathy. This reduced sensitivity is surprising, and although speculative, could be explained by the baseline state of dopaminergic nuclei, which influences dose-response and thus can seemingly paradoxically give rise to opposite behaviours.80,81 Antidepressant usage was not associated with effort or reward sensitivity in HD. Furthermore, dysphoric mood, cognition or motor severity were not associated with effort, delay or reward sensitivity. Lastly, our findings were specific to apathy, and did not generalize to impulsivity—an important control, given that these behaviours commonly co-occur and both can be conceptualized as changes to goal-directed behaviour.82 A limitation of the present work is a lack of neurophysiological data to accompany the behavioural findings. Identification of the neural regions and neuromodulatory activity involved in effort and time computations in people with and without apathy are clear research priorities. Our control group was underpowered to comprehensively analyse effort and delay cost sensitivity associations in health. An important step will be to determine this relationship in a non-diseased setting, which in turn will provide further information about whether the observed HD findings are specific to this pathology or a general feature of decision systems. This behavioural work however, lays a strong foundation for these future studies, producing a framework and clear hypotheses to investigate.

Conclusion

In conclusion, apathy in premanifest to mild motor manifest Huntington’s disease was characterized by increased sensitivity to both physical effort costs and time delays, but not insensitivity to rewarding outcomes. Furthermore, effort and delay sensitivity were associated within individuals with HD, suggesting a cost-general alteration in the cognitive mechanisms underlying goal-directed behaviour, leading to the development of apathy. This work lays an important behavioural foundation, grounded in the theoretical framework of value-based decision making which, alongside future hypothesis-driven neurophysiology studies of neural cost signals in HD apathy, may guide treatment strategies—with the ultimate goal of regaining motivated behaviour in HD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the participants who took part in this study.

Contributor Information

Lee-Anne Morris, Department of Medicine, University of Otago, Christchurch 8011, New Zealand; New Zealand Brain Research Institute, Christchurch 8011, New Zealand.

Kyla-Louise Horne, Department of Medicine, University of Otago, Christchurch 8011, New Zealand; New Zealand Brain Research Institute, Christchurch 8011, New Zealand.

Sanjay Manohar, Department of Experimental Psychology, University of Oxford, Oxford OX2 6GG, UK; Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Oxford, Oxford OX3 9DU, UK.

Laura Paermentier, New Zealand Brain Research Institute, Christchurch 8011, New Zealand.

Christina M Buchanan, Department of Neurology, Auckland City Hospital, Te Whatu Ora Health New Zealand, Auckland 1023, New Zealand; Centre for Brain Research Neurogenetics Research Clinic, University of Auckland, Auckland 1023, New Zealand.

Michael R MacAskill, New Zealand Brain Research Institute, Christchurch 8011, New Zealand.

Daniel J Myall, New Zealand Brain Research Institute, Christchurch 8011, New Zealand.

Matthew Apps, Centre for Human Brain Health, School of Psychology, University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2SQ, UK.

Richard Roxburgh, Department of Neurology, Auckland City Hospital, Te Whatu Ora Health New Zealand, Auckland 1023, New Zealand; Centre for Brain Research Neurogenetics Research Clinic, University of Auckland, Auckland 1023, New Zealand.

Tim J Anderson, Department of Medicine, University of Otago, Christchurch 8011, New Zealand; New Zealand Brain Research Institute, Christchurch 8011, New Zealand; Department of Neurology, Christchurch Hospital, Te Whatu Ora Health New Zealand, Christchurch 8011, New Zealand.

Masud Husain, Department of Experimental Psychology, University of Oxford, Oxford OX2 6GG, UK; Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Oxford, Oxford OX3 9DU, UK.

Campbell J Le Heron, Department of Medicine, University of Otago, Christchurch 8011, New Zealand; New Zealand Brain Research Institute, Christchurch 8011, New Zealand; Department of Neurology, Christchurch Hospital, Te Whatu Ora Health New Zealand, Christchurch 8011, New Zealand.

Data availability

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Funding

This study was funded by a grant from the Canterbury Medical Research Foundation (C.J.L.H.), a University of Otago doctoral scholarship (L.M.), a University of Oxford Christopher Welch Scholarship in Biological Sciences, a University of Oxford Clarendon Fund Scholarship and a Green Templeton College Partnership award (C.J.L.H.) and a Wellcome Trust Principal Research Fellowship (M.H.).

Competing interests

The authors report no competing interests.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Brain online.

References

- 1. Marin RS. Apathy: A neuropsychiatric syndrome. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1991;3:243–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Robert P, Lanctôt KL, Agüera-Ortiz L, et al. Is it time to revise the diagnostic criteria for apathy in brain disorders? The 2018 international consensus group. Eur Psychiatry. 2018;54:71–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tabrizi SJ, Scahill RI, Owen G, et al. Predictors of phenotypic progression and disease onset in premanifest and early-stage Huntington’s disease in the TRACK-HD study: Analysis of 36-month observational data. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:637–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Thompson JC, Harris J, Sollom AC, et al. Longitudinal evaluation of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Huntington’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;24:53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fritz NE, Boileau NR, Stout JC, et al. Relationships among apathy, health-related quality of life and function in Huntington’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2018;30:194–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lansdall CJ, Coyle-Gilchrist ITS, Vázquez Rodríguez P, et al. Prognostic importance of apathy in syndromes associated with frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology. 2019;92:e1547–e1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Murley AG, Rouse MA, Coyle-Gilchrist ITS, et al. Predicting loss of independence and mortality in frontotemporal lobar degeneration syndromes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2021;9:737–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yeager CA, Hyer L. Apathy in dementia: Relations with depression, functional competence, and quality of life. Psychol Rep. 2008;102:718–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Husain M, Roiser JP. Neuroscience of apathy and anhedonia: A transdiagnostic approach. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2018;19:470–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pessiglione M, Vinckier F, Bouret S, Daunizeau J, Le Bouc R. Why not try harder? Computational approach to motivation deficits in neuro-psychiatric diseases. Brain. 2018;141:629–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rangel A, Hare T. Neural computations associated with goal-directed choice. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2010;20:262–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Le Bouc R, Borderies N, Carle G, et al. Effort avoidance as a core mechanism of apathy in frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2022;146:712–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Le Heron C, Manohar S, Plant O, et al. Dysfunctional effort-based decision-making underlies apathy in genetic cerebral small vessel disease. Brain. 2018;141:3193–3210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Le Heron C, Plant O, Manohar S, et al. Distinct effects of apathy and dopamine on effort-based decision-making in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2018;141:1455–1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Saleh Y, Le Heron C, Petitet P, et al. Apathy in small vessel cerebrovascular disease is associated with deficits in effort-based decision making. Brain. 2021;144:1247–1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Le Bouc R, Rigoux L, Schmidt L, et al. Computational dissection of dopamine motor and motivational functions in humans. J Neurosci. 2016;36:6623–6633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Muhammed K, Manohar S, Ben Yehuda M, et al. Reward sensitivity deficits modulated by dopamine are associated with apathy in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2016;139:2706–2721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Martínez-Horta S, Perez-Perez J, Sampedro F, et al. Structural and metabolic brain correlates of apathy in Huntington’s disease. Mov Disord. 2018;33:1151–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Le Heron C, Apps MAJ, Husain M. The anatomy of apathy: A neurocognitive framework for amotivated behaviour. Neuropsychologia. 2018;118:54–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Levy R, Dubois B. Apathy and the functional anatomy of the prefrontal cortex–basal ganglia circuits. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16:916–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. De Paepe AE, Sierpowska J, Garcia-Gorro C, et al. White matter cortico-striatal tracts predict apathy subtypes in Huntington’s disease. Neuroimage Clin. 2019;24:101965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chong TTJ, Apps M, Giehl K, Sillence A, Grima LL, Husain M. Neurocomputational mechanisms underlying subjective valuation of effort costs. PLoS Biol. 2017;15:e1002598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Floresco SB, Ghods-Sharifi S. Amygdala-prefrontal cortical circuitry regulates effort-based decision making. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17:251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ghods-Sharifi S, St Onge JR, Floresco SB. Fundamental contribution by the basolateral amygdala to different forms of decision making. J Neurosci. 2009;29:5251–5259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Winstanley CA, Theobald DEH, Cardinal RN, Robbins TW. Contrasting roles of basolateral amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex in impulsive choice. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4718–4722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Prevost C, Pessiglione M, Metereau E, Clery-Melin ML, Dreher JC. Separate valuation subsystems for delay and effort decision costs. J Neurosci. 2010;30:14080–14090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rudebeck PH, Walton ME, Smyth AN, Bannerman DM, Rushworth MFS. Separate neural pathways process different decision costs. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1161–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wallis JD, Kennerley SW. Contrasting reward signals in the orbitofrontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1239:33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Atkins KJ, Andrews SC, Stout JC, Chong TTJ. Dissociable motivational deficits in pre-manifest Huntington’s disease. Cell Rep Med. 2020;1:100152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Atkins KJ, Andrews SC, Stout JC, Chong TTJ. The effect of Huntington’s disease on cognitive and physical motivation. Brain. 2024;147:2449–2458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McLauchlan DJ, Lancaster T, Craufurd D, Linden DEJ, Rosser AE. Insensitivity to loss predicts apathy in Huntington’s disease. Mov Disord. 2019;34:1381–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. van Wouwe NC, Kanoff KE, Claassen DO, et al. The allure of high-risk rewards in Huntington’s disease. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2016;22:426–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ratcliff R. A theory of memory retrieval. Psychol Rev. 1978;85:59–108. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gupta A, Bansal R, Alashwal H, Kacar AS, Balci F, Moustafa AA. Neural substrates of the drift-diffusion model in brain disorders. Front Comput Neurosci. 2022;15:678232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Clarke DE, Reekum Rv, Simard M, Streiner DL, Freedman M, Conn D. Apathy in dementia: An examination of the psychometric properties of the apathy evaluation scale. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;19:57–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Marin RS, Biedrzycki RC, Firinciogullari S. Reliability and validity of the Apathy Evaluation Scale. Psychiatry Res. 1991;38:143–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Callaghan J, Stopford C, Arran N, et al. Reliability and factor structure of the Short Problem Behaviors Assessment for Huntington’s disease (PBA-s) in the TRACK-HD and REGISTRY studies. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;27:59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sockeel P, Dujardin K, Devos D, Denève C, Destée A, Defebvre L. The Lille apathy rating scale (LARS), a new instrument for detecting and quantifying apathy: Validation in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:579–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Martinez-Horta S, Perez-Perez J, van Duijn E, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms are very common in premanifest and early stage Huntington’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2016;25:58–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Santangelo G, Barone P, Cuoco S, et al. Apathy in untreated, de novo patients with Parkinson’s disease: Validation study of Apathy Evaluation Scale. J Neurol. 2014;261:2319–2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Unified Huntington’s disease rating scale: Reliability and consistency. Huntington study group. Mov Disord. 1996;11:136–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hsieh S, Schubert S, Hoon C, Mioshi E, Hodges JR. Validation of the Addenbrooke’s cognitive examination III in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2013;36:242–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cheung G, Clugston A, Croucher M, et al. Performance of three cognitive screening tools in a sample of older New Zealanders. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27:981–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kourtesis P, Margioti E, Demenega C, Christidi F, Abrahams S. A comparison of the Greek ACE-III, M-ACE, ACE-R, MMSE, and ECAS in the Assessment and Identification of Alzheimer’s disease. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2020;26:825–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory–II. Psychological Corporation; 1996. doi: 10.1037/t00742-000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kirsch-Darrow L, Marsiske M, Okun MS, Bauer R, Bowers D. Apathy and depression: Separate factors in Parkinson’s disease. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2011;17:1058–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cantril H. The pattern of human concerns. 1st ed. Rutgers University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Whiteside SP, Lynam DR, Miller JD, Reynolds SK. Validation of the UPPS impulsive behaviour scale: A four-factor model of impulsivity. Eur J Personal. 2005;19:559–574. [Google Scholar]

- 50. R Core Team . R: The R Project for Statistical Computing. Accessed 11 October 2022. https://www.r-project.org/

- 51. Saleh Y, Jarratt-Barnham I, Petitet P, Fernandez-Egea E, Manohar SG, Husain M. Negative symptoms and cognitive impairment are associated with distinct motivational deficits in treatment resistant schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2023;28:4831–4841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Morel P, Ulbrich P, Gail A. What makes a reach movement effortful? Physical effort discounting supports common minimization principles in decision making and motor control. PLoS Biol. 2017;15:e2001323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shadmehr R, Huang HJ, Ahmed AA. A representation of effort in decision-making and motor control. Curr Biol. 2016;26:1929–1934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kirby KN, MarakoviĆ NN. Delay-discounting probabilistic rewards: Rates decrease as amounts increase. Psychon Bull Rev. 1996;3:100–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Peirce J, Gray JR, Simpson S, et al. Psychopy2: Experiments in behavior made easy. Behav Res Methods. 2019;51:195–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Myerson J, Baumann AA, Green L. Discounting of delayed rewards: (A)theoretical interpretation of the Kirby questionnaire. Behav Processes. 2014;107:99–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gray JC, Amlung MT, Palmer AA, MacKillop J. Syntax for calculation of discounting indices from the monetary choice questionnaire and probability discounting questionnaire. J Exp Anal Behav. 2016;106:156–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Myers CE, Interian A, Moustafa AA. A practical introduction to using the drift diffusion model of decision-making in cognitive psychology, neuroscience, and health sciences. Front Psychol. 2022;13:1039172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wiecki TV, Sofer I, Frank MJ. HDDM: Hierarchical Bayesian estimation of the drift-diffusion model in python. Front Neuroinform. 2013;7:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Carriere N, Besson P, Dujardin K, et al. Apathy in Parkinson’s disease is associated with nucleus accumbens atrophy: A magnetic resonance imaging shape analysis. Mov Disord. 2014;29:897–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Martinez-Horta S, Sampedro F, Pagonabarraga J, et al. Non-demented Parkinson’s disease patients with apathy show decreased grey matter volume in key executive and reward-related nodes. Brain Imaging Behav. 2017;11:1334–1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Morris LA, Harrison SJ, Melzer TR, et al. Altered nucleus accumbens functional connectivity precedes apathy in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2023;146:2739–2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Gold JI, Shadlen MN. The neural basis of decision making. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2007;30:535–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. McDonald AJ. Cortical pathways to the mammalian amygdala. Prog Neurobiol. 1998;55:257–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Janak PH, Tye KM. From circuits to behaviour in the amygdala. Nature. 2015;517:284–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Wassum KM, Izquierdo A. The basolateral amygdala in reward learning and addiction. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;57:271–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Vonsattel JP, Myers RH, Stevens TJ, Ferrante RJ, Bird ED, Richardson EP Jr. Neuropathological classification of Huntington’s disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1985;44:559–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Espinoza FA, Turner JA, Vergara VM, et al. Whole-brain connectivity in a large study of Huntington’s disease gene mutation carriers and healthy controls. Brain Connect. 2018;8:166–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Nair A, Johnson EB, Gregory S, et al. Aberrant striatal value representation in Huntington’s disease gene carriers 25 years before onset. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2021;6:910–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Dixon ML, Dweck CS. The amygdala and the prefrontal cortex: The co-construction of intelligent decision-making. Psychol Rev. 2022;129:1414–1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Hart EE, Izquierdo A. Basolateral amygdala supports the maintenance of value and effortful choice of a preferred option. Eur J Neurosci. 2017;45:388–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Amlung M, Marsden E, Holshausen K, et al. Delay discounting as a transdiagnostic process in psychiatric disorders: A meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76:1176–1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Varazzani C, San-Galli A, Gilardeau S, Bouret S. Noradrenaline and dopamine neurons in the reward/effort trade-off: A direct electrophysiological comparison in behaving monkeys. J Neurosci. 2015;35:7866–7877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Hezemans FH, Wolpe N, Rowe JB. Apathy is associated with reduced precision of prior beliefs about action outcomes. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2020;149:1767–1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Lottem E, Banerjee D, Vertechi P, Sarra D, Lohuis MO, Mainen ZF. Activation of serotonin neurons promotes active persistence in a probabilistic foraging task. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Miyazaki KW, Miyazaki K, Tanaka KF, et al. Optogenetic activation of dorsal raphe serotonin neurons enhances patience for future rewards. Curr Biol. 2014;24:2033–2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Costello H, Husain M, Roiser JP. Apathy and motivation: Biological basis and drug treatment. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2024;64:313–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Randall PA, Lee CA, Nunes EJ, et al. The VMAT-2 inhibitor tetrabenazine affects effort-related decision making in a progressive ratio/chow feeding choice task: Reversal with antidepressant drugs. PLoS One. 2014;9:e99320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Salamone JD, Correa M, Farrar A, Mingote SM. Effort-related functions of nucleus accumbens dopamine and associated forebrain circuits. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2007;191:461–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. O’Callaghan C, Hezemans FH, Ye R, et al. Locus coeruleus integrity and the effect of atomoxetine on response inhibition in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2021;144:2513–2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Robbins TW. Chemical neuromodulation of frontal-executive functions in humans and other animals. Exp Brain Res. 2000;133:130–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Sinha N, Manohar S, Husain M. Impulsivity and apathy in Parkinson’s disease. J Neuropsychol. 2013;7:255–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.