Abstract

Background

Janus kinase inhibitors (JAKi) have been shown to reduce pruritus and improve associated inflammatory skin lesions in canine atopic dermatitis (cAD).

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of ilunocitinib, in comparison to oclacitinib, for the control of cAD in a randomised, blinded trial.

Animals

Three‐hundred‐and‐thirty‐eight dogs with cAD.

Materials and Methods

Dogs were randomised to receive oclacitinib (0.4–0.6 mg/kg twice daily for 14 days; then once daily) or ilunocitinib (0.6–0.8 mg/kg once daily), for up to 112 days. Owners assessed pruritus using an enhanced Visual Analog Scale (PVAS). Investigators assessed skin lesions using the Canine Atopic Dermatitis Extent and Severity Index, 4th interaction (CADESI‐04).

Results

Reduction in pruritus and CADESI‐04 scores was similar for both treatment groups from Day (D)0–D14. PVAS scores increased between D14 and D28 for oclacitinib and decreased for ilunocitinib. On D28 to D112, mean PVAS and CADESI‐04 scores were significantly lower for ilunocitinib compared to oclacitinib (p ≤ 0.003 and p ≤ 0.023, respectively). On D28 to D112, a greater number of ilunocitinib‐treated dogs achieved clinical remission of pruritus (i.e. PVAS score <2). Subjective assessment of overall response was significantly better for ilunocitinib on D28 to D112 (p ≤ 0.002). Both drugs demonstrated similar safety throughout the study.

Conclusions and Clinical Relevance

Ilunocitinib rapidly and safely controlled signs of cAD. Ilunocitinib demonstrated significantly better control of pruritus and skin lesions compared to oclacitinib, with more dogs achieving clinical remission of pruritus.

Keywords: canine atopic dermatitis, ilunocitinib, JAK inhibitor, oclacitinib, pruritus, skin lesions

Background – Janus kinase inhibitors (JAKi) have been shown to reduce pruritus and improve associated inflammatory skin lesions in canine atopic dermatitis (cAD). Objective – To evaluate the efficacy and safety of ilunocitinib, in comparison to oclacitinib, for the control of cAD in a randomised, blinded trial. Conclusions and Clinical Relevance – Ilunocitinib rapidly and safely controlled signs of cAD. Ilunocitinib demonstrated significantly better control of pruritus and skin lesions compared to oclacitinib, with more dogs achieving clinical remission of pruritus.

Zusammenfassung

Hintergrund

Es konnte gezeigt werden, dass Januskinase Inhibitoren (JAKi) Juckreiz und die damit einhergehenden entzündlichen Hautveränderungen bei der caninen atopischen Dermatitis (cAD) reduzieren.

Ziel

Eine Evaluierung von Wirksamkeit und Sicherheit von Ilunocitinib zur Kontrolle von cAD in einer randomisierten, geblindeten Studie, im Vergleich zu Oclacitinib.

Tiere

Dreihundertachtundreißig Hunde mit cAD.

Materialien und Methoden

Die Hunde wurden zufällig eingeteilt, um Oclacitinib (0,4‐0,6 mg/kg) zweimal täglich für 14 Tage; danach einmal täglich) oder Ilunocitinib (0,6‐0,8 mg/kg einmal täglich) für bis zu 112 Tage zu erhalten.

Ergebnisse

Die Reduzierung von Juckreiz und CADESI‐04 Werten war für beide Behandlungsgruppen zwischen den Tagen (D)0‐D14 ähnlich. Die PVAS‐Werte nahmen zwischen D14 und D28 für Oclacitinib zu und für Ilunocitinib ab. Am D28 bis D112 waren die durchschnittlichen PVAS‐Werte sowie die CADESI‐04 Werte signifikant niedriger für Ilunocitinib im Vergleich zu Oclacitinib (p ≤ 0,003 bzw p ≤0,023). Von D28 bis D112 erzielten eine größere Anzahl an Hunden, die mit Ilunocitinib behandelt wurden, eine klinische Remission des Pruritus (i.e. PVAS‐Wert <2). Eine subjektive Bewertung der Gesamtreaktion war für Ilunocitinib von D28 bis D112 signifikant besser (p ≤0,002). Beide Wirkstoffe zeigten während der ganzen Studie eine ähnliche Sicherheit.

Schlussfolgerungen und klinische Bedeutung

Ilunocitinib kontrollierte die Zeichen von cAD schnell und sicher. Ilunocitinib zeigte eine signifikant bessere Kontrolle von Juckreiz und Hautveränderungen im Vergleich zu Oclacitinib, wobei eine größere Anzahl an Hunden eine klinische Remission des Pruritus erzielten.

摘要

背景

Janus 激酶抑制剂 (JAKi) 已被证明可以减少犬特应性皮炎 (cAD) 的瘙痒并改善相关的炎症性皮肤病变。

目的

在一项随机、盲法试验中评估伊诺替尼与奥拉替尼相比在控制 cAD 方面的有效性和安全性。

动物

338只cAD患犬

材料和方法

将犬随机分配接受奥拉替尼(0.4‐0.6 mg/kg,每天两次,持续 14 天;然后每天一次)或伊诺替尼(0.6‐0.8 mg/kg,每天一次),持续长达 112 天。主人使用增强型视觉模拟量表 (PVAS) 评估瘙痒。研究人员使用犬特应性皮炎范围和严重程度指数第 4 次迭代 (CADESI‐04) 评估皮肤病变。

结果

从第0天到第14天,两个治疗组的瘙痒和 CADESI‐04 评分减少情况相似。奥拉替尼在第 14 天和第 28 天之间的 PVAS 评分增加,伊洛替尼在第 112 天之间的 PVAS 评分降低。在第 28 天到第 112 天,伊洛替尼的平均 PVAS 以及 CADESI‐04 评分显著低于奥拉替尼(分别为 p < 0.003 和 p < 0.023)。在第 28 天到第 112 天,接受伊洛替尼治疗的犬中,有更多犬的瘙痒得到临床缓解(即 PVAS 评分 <2)。在第 28 天到第 112 天,伊洛替尼的总体反应主观评估显著更好(p < 0.002)。两种药物在整个研究过程中表现出相似的安全性。

结论和临床相关性

伊洛替尼可快速安全地控制 cAD 症状。与奥拉替尼相比,伊诺替尼在控制瘙痒和皮肤病变方面表现出明显更好的效果,更多的犬实现了瘙痒的临床缓解。

Résumé

Contexte

Les inhibiteurs de Janus kinase (JAKi) ont montré qu'ils réduisaient le prurit et amélioraient les lésions cutanées inflammatoires associées dans la dermatite atopique canine (DAC).

Objectif

Évaluer l'efficacité et la sécurité de l'ilunocitinib, en comparaison avec l'oclacitinib, pour le contrôle de la dermatite atopique canine dans un essai randomisé en aveugle.

Animaux

Trois cent trente‐huit chiens atteints de DAC.

Matériels et méthodes

Les chiens sont randomisés et reçoivent de l'oclacitinib (0,4‐0,6 mg/kg deux fois par jour pendant 14 jours, puis une fois par jour) ou de l'ilunocitinib (0,6‐0,8 mg/kg une fois par jour), pendant 112 jours au maximum. Les propriétaires évaluent le prurit à l'aide d'une échelle visuelle analogique améliorée (PVAS). Les investigateurs évaluent les lésions cutanées à l'aide du Canine Atopic Dermatitis Extent and Severity Index, 4e édition (CADESI‐04).

Résultats

La réduction du prurit et des scores CADESI‐04 est similaire dans les deux groupes de traitement du jour (J)0 au jour 14. Les scores PVAS augmentent entre J14 et J28 pour l'oclacitinib et diminuent pour l'ilunocitinib. De J28 à J112, les scores PVAS moyens ainsi que les scores CADESI‐04 sont significativement plus faibles pour l'ilunocitinib que pour l'oclacitinib (p < 0,003 et p < 0,023, respectivement). De J28 à J112, un plus grand nombre de chiens traités par l'ilunocitinib obtient une rémission clinique du prurit (c'est‐à‐dire un score PVAS < 2). L'évaluation subjective de la réponse globale est significativement meilleure pour l'ilunocitinib entre J28 et J112 (p < 0,002). Les deux médicaments font preuve d'une sécurité similaire tout au long de l'étude.

Conclusions et pertinence clinique

L'ilunocitinib permet de contrôler rapidement et en toute sécurité les signes de DAC. L'ilunocitinib permet de contrôler significativement mieux le prurit et les lésions cutanées que l'oclacitinib, avec un plus grand nombre de chiens obtenant une rémission clinique du prurit.

要約

背景

ヤヌスキナーゼ阻害薬(JAKi)は、犬アトピー性皮膚炎(cAD)における掻痒を軽減し、関連する炎症性皮膚病変を改善することが示されている。

目的

本研究の目的は、イルノシチニブのcADに対する有効性および安全性を、オクラシチニブとの比較で盲検化無作為化試験により評価することであった。

対象動物

cADの犬338頭

材料と方法

試験犬にオクラシチニブ(0.4~0.6mg/kgを1日2回、14日間投与、その後1日1回投与)またはイルノシチニブ(0.6~0.8mg/kgを1日1回投与)を最大112日間投与する群に無作為に割り付けた。掻痒の評価にはenhanced Visual Analog Scale(PVAS)を用いた。皮膚病変はCanine Atopic Dermatitis Extent and Severity Index, 4th interation(CADESI‐04)を用いて評価した。

結果

掻痒およびCADESI‐04スコアの低下は、両投与群ともDay(D)0~D14で同程度であった。PVASスコアはD14〜D28にかけてオクラシチニブ群で増加し、イルノシチニブ群で減少した。D28~D112において、平均PVASスコアおよびCADESI‐04スコアはオクラシチニブ群と比較してイルノシチニブ群で有意に低かった(それぞれp<0.003およびp<0.023)。D28~D112において、イルノシチニブ投与群ではより多くの犬が掻痒の臨床的寛解(すなわちPVASスコア<2)を達成した。全奏効に関する主観的評価は、D28〜D112においてイルノシチニブが有意に良好であった(p<0.002)。両薬剤とも試験期間を通じて同様の安全性を示した。

結論と臨床的意義

イルノシチニブはcADの徴候を迅速かつ安全に制御した。イルノシチニブはオクラシチニブと比較して、掻痒および皮膚病変のコントロールが有意に良好であり、より多くの犬が掻痒の臨床的寛解を達成した。

Resumo

Contexto

Os inibidores da Janus quinase (JAKi) demonstraram reduzir o prurido e melhorar as lesões inflamatórias cutâneas associadas à dermatite atópica canina (DAC).

Objetivo

Avaliar a eficácia e a segurança do ilunocitinib, em comparação ao oclacitinib, para o controle da DAC em um ensaio randomizado e cego.

Animais

Trezentos e trinta e oito cães com DAC.

Materiais e métodos

Os cães foram randomizados para receber oclacitinib (0,4–0,6 mg/kg duas vezes ao dia por 14 dias; depois uma vez ao dia) ou ilunocitinib (0,6–0,8 mg/kg uma vez ao dia) por até 112 dias. Os donos avaliaram o prurido usando uma Escala Visual Analógica de Prurido (PVAS) aprimorada. Os pesquisadores avaliaram as lesões cutâneas usando o Índice de Extensão e Gravidade da Dermatite Atópica Canina, 4ª interação (CADESI‐04).

Resultados

A redução no prurido e nos escores de CADESI‐04 foi semelhante para ambos os grupos de tratamento do Dia (D)0–D14. Os escores PVAS aumentaram entre D14 e D28 para oclacitinib e diminuíram para ilunocitinib. No D28 a D112, os escores médios de PVAS e CADESI‐04 foram significativamente menores para ilunocitinib em comparação com oclacitinib (p < 0,003 e p < 0,023, respectivamente). No D28 a D112, um número maior de cães tratados com ilunocitinib atingiu remissão clínica do prurido (ou seja, pontuação PVAS < 2). A avaliação subjetiva da resposta geral foi significativamente melhor para ilunocitinib no D28 a D112 (p < 0,002). Ambos os medicamentos demonstraram segurança semelhante ao longo do estudo.

Conclusões e relevância clínica

O ilunocitinib controlou de forma rápida e segura os sinais de DAC. O ilunocitinib demonstrou controle significativamente melhor do prurido e das lesões cutâneas em comparação ao oclacitinib, com mais cães alcançando remissão clínica do prurido.

RESUMEN

Introducción

Se ha demostrado que los inhibidores de la quinasa Janus (JAKi) reducen el prurito y mejoran las lesions cutáneas inflamatorias asociadas en la dermatitis atópica canina (cAD).

Objetivo

Evaluar la eficacia y seguridad de ilunocitinib, en comparación con oclacitinib, para el control de cAD en un ensayo al azar y ciego.

Animales

Trescientos treinta y ocho perros con cAD

Materiales y métodos

Los perros fueron asignados al azar para recibir oclacitinib (0,4–0,6 mg/kg dos veces al día durante 14 días; luego una vez al día), o ilunocitinib (0,6–0,8 mg/kg una vez al día), durante hasta 112 días. Los propietarios evaluaron el prurito utilizando una Escala Visual Análoga (PVAS) mejorada. Los investigadores evaluaron las lesiones cutáneas utilizando el Índice de Extensión y Gravedad de la Dermatitis Atópica Canina, 4.ª revisión (CADESI‐04).

Resultados

La reducción del prurito y de las puntuaciones de la CADESI‐04 fue similar para ambos grupos de tratamiento desde el día (D)0 al D14. Las puntuaciones PVAS aumentaron entre el D14 y el D28 para oclacitinib y disminuyeron para ilunocitinib. Del D28 al D112, las puntuaciones medias PVAS y CADESI‐04 fueron significativamente más bajas para ilunocitinib en comparación con oclacitinib (p < 0,003 y p < 0,023, respectivamente). Del D28 al D112, un mayor número de perros tratados con ilunocitinib alcanzaron la remisión clínica del prurito (es decir, puntuación PVAS <2). La evaluación subjetiva de la respuesta general fue significativamente mejor para ilunocitinib del D28 al D112 (p < 0,002). Ambos fármacos demostraron una seguridad similar durante todo el estudio.

Conclusiones y relevancia clínica

El ilunocitinib controló de forma rápida y segura los signos de la cAD. El ilunocitinib demostró un control significativamente mejor del prurito y las lesiones cutáneas en comparación con el oclacitinib, y más perros lograron la remisión clínica del prurito.

INTRODUCTION

Canine atopic dermatitis (cAD) is a common, chronic skin disease in dogs characterised by skin inflammation and pruritus. Its complex pathogenesis involves inflammatory and allergic immune responses mediated by various cytokines, many of which signal through the Janus kinase‐signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK–STAT) pathway. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 Janus kinase inhibitors (JAKi) have been demonstrated to be safe and effective in the management of pruritus associated with cAD. In 2013, the first veterinary JAKi, oclacitinib (Apoquel) received marketing authorisation in Europe for the control of clinical manifestations of cAD. The dose frequency must be reduced from twice daily to once daily at Day (D)14 of treatment, which can lead to an increase in pruritus. 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 Although oclacitinib has substantially changed the management of cAD, up to one‐third of dogs do not experience satisfactory control of clinical signs, so there remains a continuing need for novel therapeutic agents. 11

Trials evaluating the efficacy of drugs to treat cAD defined clinical success as either a ≥ 2 decrease from baseline in owner‐assessed pruritus Visual Analog Scale (PVAS) or a ≥ 50% decrease from baseline in skin lesions, assessed by the Canine Atopic Dermatitis Extent and Severity Index, 4th iteration (CADESI–04). 12 , 13 , 14 The International Committee of Allergic Diseases of Animals (ICADA) developed a Core Outcome Set for Canine Atopic Dermatitis (COSCAD'18), 15 to establish what constitutes treatment success. COSCAD'18 emphasises the importance of not only achieving delta changes (reduction by ≥2 units or ≥ 50%), but also meeting clinical thresholds that resemble those of an unaffected dog. Ideally, an efficacious therapeutic will return a dog to this clinical condition or, in other words, achieve clinical remission—a state where the disease severity has been reduced to a minimum and does not impact a dog's daily life. 16 For atopic dogs, clinical remission would mean an itch score or skin lesion score within the range of a healthy, nonallergic dog: PVAS <2 17 and CADESI‐04 <10. 18

This study was conducted in client‐owned animals to confirm the field efficacy and safety of once‐daily dosing of ilunocitinib, a novel JAKi with a high in vitro potency for inhibition of JAK1, JAK2 and tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2) (unpublished data). Oclacitinib was selected as the positive control product because of its similar mode of action to ilunocitinib, as well as being an approved product for the intended indication. In addition, to evaluate the efficacy and safety of ilunocitinib, this study assessed both delta changes and clinical remission criteria to provide a comprehensive evaluation of therapeutic success.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

This study was conducted according to applicable European and national regulatory requirements and in compliance with VICH GL9 (Good Clinical Practice, June 2000), in support of a new marketing authorisation by the European Medicines Agency. The protocol was reviewed and approved before study initiation by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Elanco Animal Health and by participating clinical investigators. Animal owners provided written informed consent to allow each dog to participate in the study.

Dogs diagnosed with cAD, in accordance with published recommendations, were enrolled at 25 veterinary clinics in Germany, Hungary, Ireland and Portugal. 19 , 20 The study was initially designed as a 56‐day prospective, double‐blinded, randomised, positive‐controlled field study to assess the efficacy and safety of ilunocitinib in comparison to oclacitinib for the treatment of pruritus and skin lesions in atopic dogs. During the in‐life phase, the protocol was amended to include an optional continuation phase, wherein dogs could continue in the same treatment group for a total study duration of 112 days. This continuation phase was implemented to gather further data on the efficacy and safety of long‐term ilunocitinib use.

Day (D)28 efficacy data were used for statistical confirmation of the noninferiority of ilunocitinib compared to oclacitinib for the treatment of clinical signs associated with cAD. A sample size estimate of 272 evaluable subjects (136 in each treatment group) was calculated to be sufficient to demonstrate noninferiority as measured by changes from baseline at D28 in both PVAS and CADESI‐04 scores with a power of ≥85% and a noninferiority margin of 20%. This calculation was based on unpublished data from a previous field study as well as published data for the positive control, assuming a two‐sided type‐I error (alpha) of 0.025, equal allocation of subjects to treatment groups in a 1:1 ratio and a common standard deviation of 35.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Client‐owned dogs of any breed or sex, >12 months of age and weighing ≥3.0 kg were eligible for enrolment. Other than a confirmed diagnosis of cAD, the dog had to be physically healthy and free of serious or systemic disease that could interfere with study objectives. All dogs underwent a diagnostic regimen determined by the investigator, which was sufficient to rule out diseases resembling cAD including food allergies, flea allergy dermatitis, bacterial or fungal dermatitis, internal and external parasitism and metabolic disease. The dog had to have had severe pruritus (PVAS score ≥6.0 of 10, i.e. moderate‐to‐severe itch) as assessed by owners 17 and at least a moderate CADESI‐04 score (≥35 of 180) 18 as assessed by the investigator. Dogs had no evidence of flea infestation at enrolment, and continuous use of flea control throughout the study was mandatory.

Dogs with conditions that required concomitant medications could be enrolled if the treatment remained consistent before the study, no change in treatment would be made during the study (e.g. NSAIDs) and/or the medication was not likely to interfere with evaluations (e.g. parasiticides and vaccinations). Withdrawal times for prohibited concurrent medications or those which were conditionally allowed are summarised in Table S1 in the Supporting information.

Exclusion criteria included: pregnant or lactating dogs, or if the dog was intended to be used for breeding purposes; evidence of malignant neoplasia, demodicosis or immune suppression such as hyperadrenocorticism; known sensitivity to JAKi; and ongoing treatment with prohibited concomitant medications within the last 90 days. Dogs with clinically significant abnormalities in complete blood counts, serum chemistry or urinalysis conducted at enrolment, were withdrawn from the study.

Enrolment, randomisation and masking

Animals that met the study inclusion criteria were blocked and randomised (block size four, two per group) in a 1:1 ratio based on the order of enrolment at each clinic to receive daily oral doses of ilunocitinib or oclacitinib using SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.). The individual dog was the experimental unit. To maintain investigator blinding, each site designated one or more persons as a dispenser who was responsible for treatment distribution. Owners were not informed about treatment group assignment or drug name, and both treatments were packaged in identical study‐specific packaging.

Drug administration

Ilunocitinib was dosed according to Table 1. Each treatment was administered with or without food, at the owner's choice. Owners were instructed to give the tablets at approximately the same time each day.

TABLE 1.

Treatment groups: Dogs were randomly allotted to two groups, Group 1 received ilunocitinib tablets and Group 2 received oclacitinib tablets.

| Treatment group | Treatment description | Treatment dose band (mg/kg body weight) | Route/dose form | Dosing frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ilunocitinib tablets | 0.6–0.8 | Oral/scored tablet | Once daily, D0 to D112 |

| 2 | Oclacitinib tablets | 0.4–0.6 | Twice daily D0 to D14, once daily D15 to D112 |

Abbreviation: D, Day.

Study activities

Baseline data (clinical history, concomitant therapies, body weight, physical examinations and assessments of pruritus and skin lesions) were collected for each dog at D0. Further clinic visits were carried out on D14 (±2), D28 (±2) and D56 (±3) and for dogs entering the continuation phase, D84 (±3) and D112 (±3). At each follow‐up visit, data were collected regarding body weight, physical examination, PVAS score, CADESI‐04 score and both the owner and investigator independently recorded overall response to treatment (RTT). RTT was assessed using a simple VAS scale graded from “no improvement” at 0 cm to “excellent improvement” at 10 cm (designated ORTT‐VAS and IRTT‐VAS, respectively). Owners kept a daily log of feeding, dosing and observations, including any possible adverse events.

Blood samples (complete blood count and serum chemistry) were collected on D0 (before dosing) and on D28, D56, D84 and D112. All blood samples were evaluated by a central laboratory (Idexx BioAnalytics, Kornwestheim, Germany).

Efficacy assessments

There were two equivalent primary end‐points: percentage reduction from baseline (D0) on D28 in owner‐assessed PVAS scores and percentage reduction from baseline on D28 in investigator‐assessed CADESI‐04 scores. Further efficacy assessments included evaluation of: (i) the change in PVAS or CADESI‐04 over time; (ii) the proportion of dogs with ≥50% decrease in PVAS or CADESI‐04; (iii) the proportion of dogs with ≥2 cm decrease in PVAS; (iv) frequency of dogs meeting the criteria of clinical remission from pruritus or skin lesions – i.e. scores of <2 for PVAS or < 10 for CADESI‐04 respectively; and (v) owner and investigator independent evaluations of overall RTT (ORTT and IRTT, respectively).

Safety assessments

Clinical safety was assessed via adverse events (AEs), physical examinations and clinical pathological investigations (haematology and serum chemistry). An abnormal clinical sign occurring at any time during the study after dosing on D0 was documented as an AE regardless of the treatment group.

Data analysis

All assessments were evaluated at the two‐tailed 0.05 level of significance, except for the tests for noninferiority which had a 20% margin. This margin was set following statistical guideline EMA/CVMP/EWP/81976/2010 recommendations. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS for windows (v9.4).

Efficacy data were analysed from two populations of animals: (1) Intention to treat: those dogs that were enrolled, received at least one dose of medication and at least one post‐baseline measurement was obtained. (2) Per protocol: those dogs that were enrolled and completed the study without major deviations from the study. Because both populations were very similar, efficacy conclusions were based on the results from the per‐protocol analyses. All dogs that received at least one dose of assigned medication were included in the evaluation of product safety, regardless of whether they completed the study. Adverse events were coded by preferred terms (PT) and summarised by system organ class (SOC) based on the Veterinary Dictionary for Drug Regulatory Activities (VeDDRA).

Noninferiority

The analyses were conducted using a linear mixed effect model for repeated measures (MMRM), which included baseline as a covariate, and treatment, time and treatment × time interaction as fixed effects. The model included site, treatment‐by‐site and animal as random effects.

For both PVAS and CADESI‐04, the difference in percentage change from baseline in scores, between the two treatment groups, assessed at D28, was calculated. To adjust for multiple testing of the two primary efficacy variables, a Bonferroni corrected significance level of 2.5% and confidence intervals (CI) of 97.5% were used. Noninferiority of ilunocitinib to oclacitinib was concluded if the upper limit of the 97.5% CI for the difference of oclacitinib minus ilunocitinib was <20%.

Efficacy assessments

Assessments with a binary response were analysed using a generalised linear mixed model for repeated measures with a logit link and binomial error. The model included treatment, time and treatment × time as fixed effects and site, treatment × site and animal as random effects. Model‐derived estimates of the treatment success rates and 95% CIs were calculated for each treatment group.

Continuous efficacy assessments were analysed using a linear mixed model for repeated measures including fixed effects of treatment, time and treatment × time interaction. Site, treatment × site and animal were included as a random effect. Baseline CADESI‐04 scores were included in the CADESI‐04 model and baseline PVAS scores were included in the ORTT and IRTT models as a covariate. For continuous secondary end‐points, data also were summarised by treatment group for each study visit.

Dogs withdrawn from the study on or before each day of assessment as a consequence of worsening signs of cAD (lack of efficacy), or an AE potentially related to the study drug, were considered as treatment failures for each binary response variable. For continuous variables, the last time point that data were available was used for subsequent time points.

RESULTS

Demographics

A total of 338 dogs were enrolled and randomised into the study: 169 to the ilunocitinib group and 169 to the oclacitinib group. The mean age was 5.5 years and the mean body weight (BW) was 19.1 kg. Female and pure‐bred dogs were more frequently enrolled. Demographics of the study population are presented in Table 2. Because the optional continuation phase was implemented several months after the study start, not all dogs had the opportunity to stay in the study beyond D56. Consequently, a total of 154 dogs entered the continuation phase (75 ilunocitinib, 79 oclacitinib).

TABLE 2.

Demographics of enrolled dogs at Day 0.

| Statistic | Ilunocitinib n = 169 | Oclacitinib n = 169 | Total n = 338 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Min, max | (1.0, 13.4) | (1.0, 13.5) | (1.0, 13.5) |

| Mean | 5.57 | 5.49 | 5.53 | |

| SD | 3.22 | 3.14 | 3.17 | |

| Body weight (kg) | Min, max | (3.1, 50.1) | (3.2, 60.1) | (3.1, 60.1) |

| Mean | 18.24 | 20.04 | 19.14 | |

| SD | 10.87 | 12.29 | 11.62 | |

| Gender | Female | 92 (54.4%) | 105 (62.1%) | 197 (58.3%) |

| Male | 77 (45.6%) | 64 (37.9%) | 141 (41.7%) | |

| Breed | Mixed | 46 (27.2%) | 65 (38.5%) | 111 (32.8%) |

| Pure‐bred | 123 (72.8%) | 104 (61.5%) | 227 (67.2%) | |

| PVAS | Mean | 7.8 | 7.8 | 7.8 |

| SD | 0.991 | 1.062 | 1.026 | |

| (Min, max) | (6, 10) | (6, 10) | (6, 10) | |

| CADESI‐04 | (Min, max) | (35.0, 136.0) | (35.0, 138.0) | (35, 138) |

| Mean | 61 | 63 | 61.91 | |

| SD | 20.630 | 23.535 | 22.129 |

Abbreviations: CADESI‐04, Canine Atopic Dermatitis Extent and Severity Index, 4th iteration; PVAS, pruritus Visual Analog Scale.

Efficacy analyses: Tests of noninferiority

Pruritus visual analog scale (PVAS)

The mean percentage reduction from baseline on D28 was 68.2% for ilunocitinib and 59.4% for oclacitinib. Ilunocitinib demonstrated noninferiority to oclacitinib, and the difference between treatment groups was statistically significant (p = 0.003) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Percentage reduction of the pruritus Visual Analog Scale (PVAS) and Canine Atopic Dermatitis Extent and Severity Index, 4th iteration (CADESI‐04) score from baseline (Day 28).

| Variable | Treatment group | Study day | Model estimates | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSmean | Standard error | 95% CI | p‐Value versus oclacitinib | |||

| PVAS | Ilunocitinib | 28 | 68.2 | 2.65 | (63.04, 73.43) | 0.003 |

| Oclacitinib | 59.4 | 2.67 | (54.20, 64.69) | |||

| CADESI‐04 | Ilunocitinib | 28 | 73.2 | 3.10 | (67.15, 79.32) | 0.056 |

| Oclacitinib | 69.0 | 3.11 | (62.86, 75.08) | |||

Note: Significant differences are displayed in bold.

Canine atopic dermatitis extent and severity index (CADESI‐04)

The mean percentage reduction from baseline on D28 was 73.2% for ilunocitinib and 69.0% for oclacitinib, and ilunocitinib demonstrated noninferiority to oclacitinib (Table 3).

Efficacy assessments

Owner‐assessed pruritus scores (PVAS)

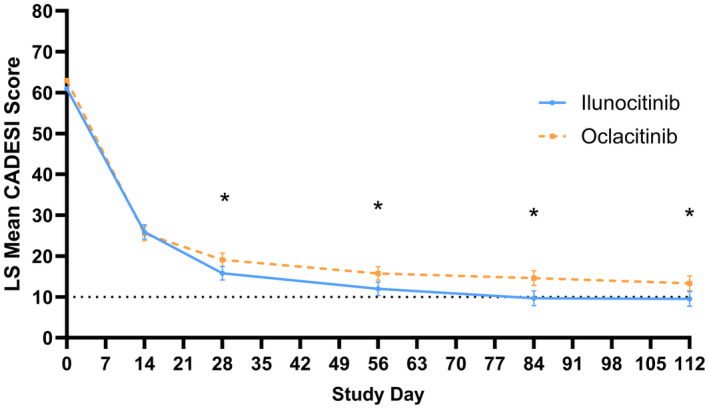

Over the first 7 days of treatment, there was a rapid drop in mean PVAS to approximately half of the baseline for both treatment groups, and PVAS scores continued to improve up to D14. On D28, there was a mild increase in PVAS for oclacitinib‐treated dogs, while ilunocitinib‐treated dogs demonstrated continuous improvement in PVAS scoring. Mean PVAS scores for ilunocitinib‐treated dogs were significantly lower than for oclacitinib‐treated dogs on D28 to D112 (p ≤ 0.003; Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Least square means (LSM) ± SEs pruritus Visual Analog Scale (PVAS) score over time. *Statistically significant difference.

A greater percentage of ilunocitinib‐treated dogs achieved ≥50% reduction from baseline in PVAS from D28 onward, with significantly greater numbers on D28 to D84 (p ≤ 0.03) compared to oclacitinib‐treated dogs. At D84, 90% of ilunocitinib‐treated dogs had achieved a 50% reduction compared to 72% of oclacitinib‐treated dogs (Table S2). A similar finding was observed for a ≥2.0 cm reduction from baseline in PVAS, with significantly greater numbers on D56 and D84 (p ≤ 0.043) (Table S3).

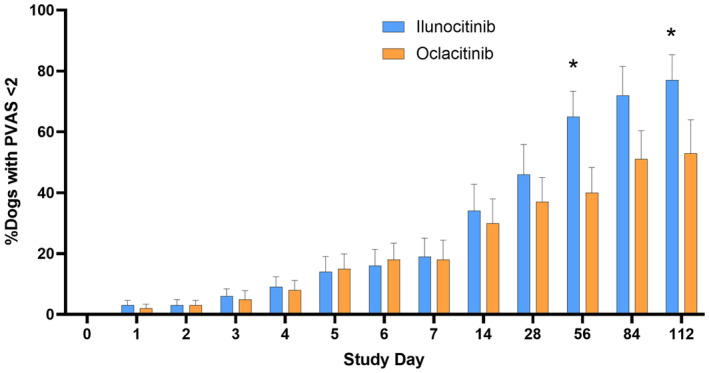

A higher proportion of dogs treated with ilunocitinib reached clinical remission of pruritus (PVAS <2) from D14 onwards compared to dogs treated with oclacitinib, with the difference being significant on D56 and D112 (p < 0.04) (Figure 2). By D112, 77% of ilunocitinib‐treated dogs were in clinical remission versus 53% of oclacitinib‐treated dogs.

FIGURE 2.

Proportion of dogs in clinical remission from pruritus (pruritus Visual Analog Scale [PVAS] <2). Data presented are percentage of dogs with PVAS <2 (normal). *Statistically significant difference.

Investigator‐assessed skin lesion scores (CADESI‐04)

For both ilunocitinib and oclacitinib, the mean CADESI‐04 scores dropped rapidly over the first 14 days of treatment to less than half of the baseline scores. However, from D 28 to D112, the mean scores of ilunocitinib‐treated dogs were significantly lower than the mean scores of oclacitinib‐treated dogs (p ≤ 0.02) (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Mean Canine Atopic Dermatitis Extent and Severity Index (CADESI)‐04 scores. Data presented are the least square mean ± SEs. The horizontal line at CADESI‐04 = 10 represents the threshold for clinical remission from skin lesions. A dog is considered to have achieved clinical remission if their CADESI‐04 score is below this value. *Statistically significant difference.

The percentage of dogs achieving ≥50% reduction from baseline in CADESI‐04 scores was similar for both treatment groups at D14. From D28 to D112, 94%–97% of dogs treated with ilunocitinib demonstrated ≥50% reduction from baseline in CADESI‐04 compared to 85–88% of dogs treated with oclacitinib. On D28 and D56 the difference was statistically significant (p ≤ 0.005) (Table S4).

The proportion of dogs achieving clinical remission from skin lesions (CADESI‐04 <10) was numerically higher in the ilunocitinib group compared to the oclacitinib group from D56 onwards (43%–69% versus 37%–64%, respectively), although this difference did not reach statistical significance. The proportions were similar for both treatment groups on D14 and D28 (Table S5).

Owner and investigator assessment of response to treatment

The comparison of ORTT and IRTT between the treatment groups on D14 to D112 is displayed in Table 4, with higher scores indicating a better clinical response. On D14, ORTT and IRTT were similar for both treatment groups. On all subsequent days, ORTT and IRTT were significantly better in the ilunocitinib group compared to the oclacitinib group (p ≤ 0.002) (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Owner‐assessed response to treatment (ORTT−VAS) score and investigator response to treatment (IRTT−VAS) score linear mixed model for repeated measures (LMM).

| Study day | ORTT‐VAS | IRTT‐VAS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ilunocitinib LS mean (SE) | Oclacitinib LS mean (SE) | p‐value I versus O | Ilunocitinib LS mean (SE) | Oclacitinib LS mean (SE) | p‐Value I versus O | |

| 14 | 7.22 (0.211) | 7.14 (0.213) | 0.742 | 7.26 (0.191) | 7.37 (0.193) | 0.592 |

| 28 | 7.90 (0.211) | 7.04 (0.213) | <0.001 | 8.26 (0.192) | 7.51 (0.193) | <0.001 |

| 56 | 8.56 (0.214) | 7.50 (0.214) | <0.001 | 8.80 (0.197) | 7.83 (0.197) | <0.001 |

| 84 | 8.53 (0.256) | 7.51 (0.252) | <0.001 | 8.88 (0.231) | 7.97 (0.227) | <0.001 |

| 112 | 8.70 (0.254) | 7.77 (0.252) | 0.002 | 8.92 (0.230) | 8.06 (0.229) | 0.002 |

Note: Significant differences are displayed in bold.

Safety

Physical examination results

The results of physical examinations (respiration rate, heart rate, rectal temperature and body weight) showed no abnormal or notable changes in both treatment groups over the study period.

Serum biochemical and haematological results

No clinically relevant differences were seen in any of the serum biochemical parameters in either treatment group over the study period.

While in most cases mean values remained within normal laboratory reference ranges, during the first 28 days of the study both treatment groups showed similar decreases in mean leucocyte counts, primarily involving neutrophils and eosinophils with monocytes being affected to a lesser degree.

The statistical analysis of haematological parameters revealed a treatment effect for eosinophils (% and absolute), erythrocytes, haemoglobin concentration and packed cell volume (%), as well as a treatment × time effect for band neutrophils (%). However, the differences in the means of these parameters between the two study groups and between study days were small and not considered to be of clinical relevance.

Concomitant therapies

Forty‐one ilunocitinib‐treated dogs and 31 oclacitinib‐treated dogs were administered a variety of concomitant therapies during the study. The most administered therapeutics were: parasiticides, vaccines, antibiotics, antifungals, NSAIDs, ear cleaners, sedatives/anaesthetics and dietary supplements such as pre‐ and probiotics (for a complete listing, see Table S6). There were no drug interactions observed with the concomitantly used veterinary medicinal products in either treatment group.

Adverse events

Adverse events were monitored over the extended study period of 112 days and their frequency was calculated on a per‐animal basis. The frequency of any observed AE was similar in both treatment groups. Most commonly observed AEs were digestive tract disorders, predominantly emesis and diarrhoea with 13.6% and 10.7% in the ilunocitinib and oclacitinib group, respectively, followed by systemic disorders (5.3% ilunocitinib; 7.1% oclacitinib) and skin/appendages disorders (5.9% ilunocitinib; 3.6% oclacitinib) (Table S7).

Most of these AEs were evaluated by the investigators as possibly related to treatment. Clinically relevant laboratory investigation results were documented as AEs on six occasions (3.6%) in both treatment groups. Most of them were evaluated as either possibly treatment‐related or unknown.

Four serious adverse events were observed and their relationship to treatment was assessed as unlikely or unknown. Three were in the oclacitinib group (fatal road traffic accident; hepatitis; mammary gland mass) and one in the ilunocitinib group (seminoma).

DISCUSSION

This multi‐site pivotal field study of once‐daily administration of ilunocitinib given with or without food at a dose of 0.6–0.8 mg/kg for the control of cAD in client‐owned dogs provided extensive product efficacy and safety data. Enrolment of 338 dogs at 25 clinics in four different countries with diverse climatic conditions enabled data collection in a variety of clinical settings in dogs with a broad range of environmental allergies. Demographically, the study population was well‐balanced between the two treatment groups and represented a spectrum of ages, breeds, pre‐existing medical conditions and concomitant medication use.

Results indicate that ilunocitinib is highly efficacious when used in accordance with the stated once‐daily dosing schedule. Ilunocitinib was rapidly efficacious, closely matching oclacitinib BID for reduction of pruritus and skin lesion scores over the first 14 days of the study. However, with the change in dosing schedule after D14 for oclacitinib‐treated animals, ilunocitinib‐treated dogs were numerically or statistically significantly improved at all subsequent time points and for all pruritic indicators of efficacy when compared to oclacitinib‐treated dogs.

It has been reported previously that the change to once‐daily dosing of oclacitinib after D14 leads to a renewed increase of pruritus in some dogs. 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 While most studies report only the group mean PVAS score, which tends to increase from D14 to D28 following the reduction in oclacitinib dosage, the proportion of dogs showing increased pruritus levels is less commonly detailed. Notably, a study by Olivry et al. reported that 45% of dogs experienced a worsening of pruritus after reducing the dose frequency. 9 A reasonable hypothesis for the rebound effect is supported by the experimental observation of increased transcription of pruritogenic cytokines following cessation of oclacitinib therapy in mice. 10 In our study, the rebound effect for the oclacitinib‐treated group was only mild, and the reason for the difference between our findings and those reported in the literature is unknown. 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 However, mean pruritus scores for the ilunocitinib‐treated group decreased continuously as a result of the consistent once‐daily dosing scheme. Consequently, even though the rebound effect for oclacitinib was not pronounced in our study, a distinct divergence between the two treatment groups was evident when the oclacitinib dosage was reduced, as demonstrated by significantly lower mean PVAS scores from D28 onwards, (significantly) greater percentages of dogs with ≥2 cm decrease in PVAS, (significantly) more dogs with a ≥50% decrease in PVAS, and ultimately to (significantly) greater numbers of dogs in clinical remission from pruritus.

In addition to the rapid decrease in pruritic behaviour, both treatment groups showed a fast improvement in skin lesion scores after treatment initiation. By D14, mean CADESI‐04 scores were less than half of those for D0 for both treatment groups. Skin lesion scores in both groups continued to decrease with ongoing treatment and similar to the trend observed in pruritus scores, the groups began to diverge following a reduction in the oclacitinib dosage. This divergence led to significantly lower mean CADESI‐04 scores in the ilunocitinib‐treated group compared to the oclacitinib group from D28 onwards. There are two likely reasons for the prompt and sustained improvement of skin lesion scores with ilunocitinib treatment. First, the rapid decrease in pruritus disrupts the itch–scratch cycle, reducing mechanical damage to the skin from scratching and allowing it to restore. Second, ilunocitinib has shown potent inhibition of JAK1, JAK2 and TYK2 in vitro, and it is highly likely that this also decreases the signalling of many pro‐inflammatory cytokines involved in the pathogenesis of cAD in vivo. With the rapid and sustained improvement in skin lesions observed in this study, it is concluded that ilunocitinib also has an anti‐inflammatory effect.

Achieving clinical remission – defined as a state where the disease severity does not significantly impact a dog's daily life – is an important measure of therapeutic success. In this study clinical remission was quantified as a PVAS score <2 for pruritus and a CADESI‐04 score < 10 for skin lesions. For pruritus, greater proportions of dogs treated with ilunocitinib achieved clinical remission between D28 and D112, with significant differences compared to oclacitinib on D56 and D112. By D112, 77% of ilunocitinib‐treated dogs were in clinical remission from pruritus, while 53% of dogs treated with oclacitinib reached this state. In summary, more than three‐quarters of dogs receiving ilunocitinib returned to a pruritus level comparable to that of a normal, nonallergic dog. For skin lesion scores, the proportion of dogs in clinical remission also was numerically higher in the ilunocitinib‐treated group from D56 onwards without reaching the level of statistical significance. At D112, 69% of dogs in the ilunocitinib group had achieved clinical remission from skin lesions compared to 64% in the oclacitinib group. These results are in line with the anti‐inflammatory effect of ilunocitinib and JAK inhibitors in general discussed above. 21

In the evaluation of efficacy, it is important to consider the overall opinion of the owners and investigators regarding the success of treatment. ORTT and IRTT scores were similar for both treatment groups on D14, while at all subsequent time points, both owners and investigators ranked ilunocitinib significantly higher than oclacitinib for the RTT. Ongoing clinical signs can severely impact the human–animal bond. 22 The comparable and even higher RTT scores for ilunocitinib suggest that it can substantially contribute to an improvement in the quality of life for both the dog and its owner, similar to the effects described for oclacitinib treatment. 23

Ilunocitinib was well‐tolerated when used in accordance with the stated dosing schedule. During the study, there were no notable changes observed in the clinical safety parameters such as respiration rate, heart rate, rectal temperatures and body weight. Likewise, there were no clinically relevant abnormalities seen in the serum chemistry results. Decreases in leucocyte counts, primarily involving neutrophils and eosinophils with monocytes being affected to a lesser degree, were seen in both treatment groups over the study period, yet most of these remained within normal laboratory reference ranges. Changes in haematological parameters have been described previously for JAKi and the clinical pathological changes observed in this study were similar to those reported previously. 6 , 24

The most frequently observed AEs were digestive tract disorders (e.g. emesis and diarrhoea), followed by systemic disorders and skin and appendage disorders. Similar AEs are already known and reported for the commercially marketed JAKi. 24 None of the four serious AEs were assessed as likely, probably or possibly related to the experimental treatment. No drug interactions were observed with the concomitantly used veterinary medicinal products (primarily vaccines, parasiticides and antibiotics/antifungals). The low frequency of AEs and limited impact on serum biochemical and haematological parameters during a study lasting up to 112 days suggest that ilunocitinib is a well‐tolerated therapy for the management of cAD.

Limitations of the study include that the opportunity to enter the continuation phase was only introduced several months after the study start. Many dogs had already completed the study by the time of the amendment, which is why data for D84 and D112 include a lower number of dogs. However, dogs were still evenly distributed to treatment groups and even with lower numbers, it was possible to demonstrate statistically significant improvement of ilunocitinib‐treated dogs over oclacitinib‐treated dogs in multiple parameters at these time points. Another limitation of the study was that in statistical analyses for secondary efficacy parameters, the level of significance was not adjusted for multiple end‐point testing to account for the potential inflation of type‐I error rate. Therefore, although the overall outcome of the study was consistently in favour of ilunocitinib, individual p‐values should be interpreted with caution.

CONCLUSIONS

Based on the results of this field study in client‐owned dogs, once‐daily administration of ilunocitinib administered with or without food, at the dosage of 0.6–0.8 mg/kg, is efficacious and safe for the treatment of clinical manifestations of cAD. Ilunocitinib treatment demonstrated better clinical outcomes compared to oclacitinib treatment in multiple efficacy parameters, and continuous once‐daily dosing reduces caregiver burden compared to products requiring a change in dosing regimen over time.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Sophie Forster: Writing – original draft; writing – review and editing; methodology; project administration; conceptualization. Simona Despa: Writing – review and editing; formal analysis. Candace Trout: Writing – review and editing; project administration. Stephen King: Writing – review and editing. Annette Boegel: Writing – review and editing.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The study was initiated and funded by Elanco Animal Health, Inc., Greenfield, IN, USA.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

All authors are current or former employees of Elanco Animal Health.

Supporting information

Data S1.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank all of the dog owners and the following veterinarians who enrolled dogs in this study: Carla Albano, Ricardo Baptista, Anna Csernavölgyi, Lydia Doyle Clerkin, Catarina Duarte, Adriana Estrela, Sara Rola Franca, Nicholas Garvey, Annamária Gergely, Peter Grommelt, Tamas Jando, László Király, Elisabeth Koldt, Donal Lynch, Manuela Mangas, Ursula Mayer, Ricardo Mendanha, Carolina Mesquita, Péter Novák, Kieran O'Mahony, Krisztina Briskine Palfi, Patricia Ribereiro de Sá, Joana Rocha and Fernando Costa Silva. We thank the following current and former Elanco colleagues for their contributions: Jane Owens, David Wheeler, Kelly Doucette and Shilpa Rani.

Forster S, Boegel A, Despa S, Trout C, King S. Comparative efficacy and safety of ilunocitinib and oclacitinib for the control of pruritus and associated skin lesions in dogs with atopic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol. 2025;36:165–176. 10.1111/vde.13319

REFERENCES

- 1. Datsi A, Steinhoff M, Ahmad F, Alam M, Buddenkotte J. Interleukin‐31: the “itchy” cytokine in inflammation and therapy. Allergy. 2021;76:2982–2997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gonzales AJ, Humphrey WR, Messamore JE, Fleck TJ, Fici GJ, Shelly JA, et al. Interleukin‐31: its role in canine pruritus and naturally occurring canine atopic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol. 2013;24:48–53.e11‐2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bachmann MF, Zeltins A, Kalnins G, Balke I, Fischer N, Rostaher A, et al. Vaccination against IL‐31 for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in dogs. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142:279–281.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Marsella R, Ahrens K, Sanford R. Investigation of the correlation of serum IL‐31 with severity of dermatitis in an experimental model of canine atopic dermatitis using beagle dogs. Vet Dermatol. 2018;29:69‐e28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chaudhary SK, Singh SK, Kumari P, Kanwal S, Soman SP, Choudhury S, et al. Alterations in circulating concentrations of IL‐17, IL‐31 and total IgE in dogs with atopic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol. 2019;30:383‐e114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cosgrove SB, Wren JA, Cleaver DM, Walsh KF, Follis SI, King VI, et al. A blinded, randomized, placebo‐controlled trial of the efficacy and safety of the Janus kinase inhibitor oclacitinib (Apoquel®) in client‐owned dogs with atopic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol. 2013;24:587–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Little PR, King VL, Davis KR, Cosgrove SB, Stegemann MR. A blinded, randomized clinical trial comparing the efficacy and safety of oclacitinib and ciclosporin for the control of atopic dermatitis in client‐owned dogs. Vet Dermatol. 2015;26:23–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gadeyne C, Little P, King VL, Edwards N, Davis K, Stegemann MR. Efficacy of oclacitinib (Apoquel®) compared with prednisolone for the control of pruritus and clinical signs associated with allergic dermatitis in client‐owned dogs in Australia. Vet Dermatol. 2014;25:512–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Olivry T, Lokianskiene V, Blanco A, Mestre PD, Bergvall K, Beco L. A randomised controlled trial testing the rebound‐preventing benefit of four days of prednisolone during the induction of oclacitinib therapy in dogs with atopic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol. 2023;34:99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fukuyama T, Ganchingco JR, Bäumer W. Demonstration of rebound phenomenon following abrupt withdrawal of the JAK1 inhibitor oclacitinib. Eur J Pharmacol. 2017;794:20–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nuttall T. The genomics revolution: will canine atopic dermatitis be predictable and preventable? Vet Dermatol. 2013;24:10–18.e3‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wheeler D, Civil J, Payne‐Johnson M, Stegemann M, Cosgrove S. Oclacitinib for the treatment of pruritus and lesions associated with canine flea allergic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol. 2012;23(S1):2–104.22823741 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Olivry T, Bizikova P. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials for prevention or treatment of atopic dermatitis in dogs: 2008–2011 update. Vet Dermatol. 2013;24:97–117.e25‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Olivry T, Steffan J, Fisch RD, Prélaud P, Guaguère E, Fontaine J, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the efficacy of cyclosporine in the treatment of atopic dermatitis in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2002;221:370–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Olivry T, Bensignor E, Favrot C, Griffin CE, Hill PB, Mueller RS, et al. Development of a core outcome set for therapeutic clinical trials enrolling dogs with atopic dermatitis (COSCAD'18). BMC Vet Res. 2018;14:238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bieber T. Disease modification in inflammatory skin disorders: opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2023;22:662–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hill PB, Lau P, Rybnicek J. Development of an owner‐assessed scale to measure the severity of pruritus in dogs. Vet Dermatol. 2007;18:301–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Olivry T, Saridomichelakis M, Nuttall T, Bensignor E, Griffin CE, Hill PB, et al. Validation of the canine atopic dermatitis extent and severity index (CADESI)‐4, a simplified severity scale for assessing skin lesions of atopic dermatitis in dogs. Vet Dermatol. 2014;25:77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hensel P, Santoro D, Favrot C, Hill P, Griffin C. Canine atopic dermatitis: detailed guidelines for diagnosis and allergen identification. BMC Vet Res. 2015;11:196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Favrot C, Steffan J, Seewald W, Picco F. A prospective study on the clinical features of chronic canine atopic dermatitis and its diagnosis. Vet Dermatol. 2010;21:23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bonelli M, Kerschbaumer A, Kastrati K, Ghoreschi K, Gadina M, Heinz LX, et al. Selectivity, efficacy and safety of JAKinibs: new evidence for a still evolving story. Ann Rheum Dis. 2024;83:139–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Linek M, Favrot C. Impact of canine atopic dermatitis on the health‐related quality of life of affected dogs and quality of life of their owners. Vet Dermatol. 2010;21:456–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cosgrove SB, Cleaver DM, King VL, Gilmer AR, Daniels AE, Wren JA, et al. Long‐term compassionate use of oclacitinib in dogs with atopic and allergic skin disease: safety, efficacy and quality of life. Vet Dermatol. 2015;26:171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. CVMP assessment report for APOQUEL (EMEA/V/C/002688/0000). [cited 2024 Jul 31]. Available from: https://medicines.health.europa.eu/veterinary/en/600000035462#documents

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1.