Abstract

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a major human pathogen whose increased antibiotic resistance poses a serious threat to human health.

Aim

The aim of this study is to further explore the association between H. pylori resistance to clarithromycin, levofloxacin, metronidazole, amoxicillin, rifampicin, tetracycline and its genomic characteristics.

Methodology

Using H. pylori isolates, we studied their susceptibility to six antibiotics by the agar dilution method. By performing whole-genome resequencing of the H. pylori genomic DNA, the differences in single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) between phenotype resistant and sensitive strains were statistically analyzed to identify potential mutation sites related to drug resistance, and the consistency between genotype and phenotype resistance was analyzed.

Results

The drug resistance rates of 65 H. pylori isolates are as follows: clarithromycin 36.9%, levofloxacin 29.2%, metronidazole 63.1%, amoxicillin 7.7%, rifampicin 12.3%, and tetracycline 3.1%. Based on the whole genome resequencing results of H. pylori isolates, 10 new mutations that may be related to drug resistance were identified. There is strong consistency between the genotype and phenotype resistance of clarithromycin and levofloxacin.

Conclusion

The resistance rate to amoxicillin and tetracycline is relatively low in Northern China. and the above two antibiotics can be given priority for clinical treatment. It has a high resistance rate to metronidazole and should be avoided as much as possible, or combined with other drugs for treatment. The 10 mutations identified through analysis that only exist in drug-resistant strains may be associated with levofloxacin, metronidazole, amoxicillin, and rifampicin resistance, respectively. The results indicate that genotype testing of H. pylori can serve as a method for predicting its resistance to clarithromycin and levofloxacin.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s42770-024-01582-w.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, Resistance, Whole-genome resequencing, Mutations

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a Gram negative bacterium, with infection rates typically exceeding 50% in regions such as Asia and South America, making it a major global public health challenge [1]. It may lead to severe gastrointestinal diseases, including gastric and duodenal ulcers, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT), and gastric cancer [2].

The mechanisms of antibiotic resistance development in H. pylori have been increasingly studied in depth over the past two decades, mainly for the family of antibiotics commonly used in the treatment of H. pylori infection, namely β-lactams, quinolones, macrolides, nitroimidazoles tetracyclines, etc. The main reason for treatment failure is the increasing drug resistance of H. pylori. Currently, the antibiotics used for the treatment of H. pylori infection in the latest consensus mainly include clarithromycin (CLR), levofloxacin (LVX), metronidazole (MNZ), amoxicillin (AMO), rifampicin (RIF), and tetracycline (TET) [3, 4].

Antibiotic susceptibility guided therapy instead of empirical therapy fulfills antibiotic stewardship principles, ensuring a satisfactory eradication success rate and preventing further antibiotic misuse and resistance [5]. However, a culture-based antimicrobial susceptibility testing performed on gastric biopsy tissue is time-consuming (results take > 2 weeks to be available). Current molecular tests for detecting H. pylori resistance focus on identifying mutations in specific genes or regions associated with resistance to CLR and/or LVX [6]. The drug resistance of H. pylori mainly comes from structural changes in gene sequences. These changes disrupt the cellular activity of antibiotics by altering drug targets or inhibiting intracellular drug activation. It has been reported that most genetic changes related to antibiotic resistance are mutations (e.g., missense, nonsense, frameshift, insertion, or deletion) [7]. Several common mutations associated with drug resistance in H. pylori have been identified, and confirmed in multiple regions. It has been reported that the most common genetic mutations associated with CLR resistance are mutations of 23 S rRNA, specifically A2142G/C or A2143G [8]. However, PPI-based therapies containing CLR may also fail in patients without these mutations [9]. Furthermore, the gyrA gene is not specific enough to predict LVX resistance to H. pylori [10]. Increasing evidence has shown that antibiotic resistance is determined by many resistance genes or mutations.

Recently, bacterial whole genome sequencing (WGS) enabled by next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology has become an economically efficient, powerful, and fast tool for antimicrobial resistance prediction and infectious disease monitoring [11, 12].Currently, numerous studies have identified genotypes that predict bacterial resistance, based on WGS [13, 14]. Within a clinically relevant timeframe (24 to 72 h). WGS allows for a more comprehensive analysis of bacterial resistance mechanisms than traditional methods alone, enabling a better correspondence between genotype and phenotype as well as the development of a molecular antimicrobial susceptibility system [15]. To determine their biological correlation with phenotype resistance in the region, expanding the sample size is still necessary due to differences in genomic characteristics between strains around the world. In addition, there are limited studies on the mutation characteristics associated with antibiotic resistance of several other antibiotics that used to treat H. pylori. Further in-depth exploration is needed. This study aims to further explore the association between H. pylori resistance to CLR, LVX, MNZ, AMO, RIF, TET and its genomic characteristics.

Methods

Study design and H. Pylori isolates collection

Patients who underwent gastroscopy with dyspepsia symptoms at Emergency General Hospital from October 2021 to February 2022 were included in this study. The patients were examined by a professional gastroenterologist through an electronic gastroscopy. All patients involved have not undergone eradication treatment for H. pylori. Patients who had used bismuth, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), antibiotics, or probiotics in the last four weeks were excluded. Furthermore, pregnant and patients with gastrointestinal perforation were excluded. A total of 115 patients were enrolled in this study. The patients’ age and gender were available. The gastric biopsy specimens from the gastric antrum or corpus of 115 patients were transported to the laboratory in Brucella broth (Solarbio, China) containing 10% fetal calf serum (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) and 5% sucrose (Solarbio, China). The gastric biopsies were inoculated onto selective agar which contained Columbia Blood Agar (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 7% sterile defibrinated sheep blood (Solarbio, China) and Dent (Oxoid, UK) for up to 7 days and grew at 37 °C in microaerophilic conditions (10% CO2, 5% O2, and 85% N2) generated with GENbox microaerophilic gas pack (BioMeriuex, France). H. pylori was identified by urease, catalase and oxidase assays as well as Gram staining.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) protocols were followed for the antimicrobial susceptibility testing using Mueller-Hinton agar (Solarbio, China) containing 5% sterile defibrinated sheep blood and two-fold serial dilutions of antibiotics. H. pylori isolates were grown on Columbia blood agar plates for 72–96 h at 37 °C and suspended in 0.9% saline to achieve a McFarland opacity of 2.0.

The CLSI M45 3rd guideline was used to determine CLR susceptibility. Due to the lack of established CLSI interpretive criteria for LVX, TET, MNZ, RIF, and AMO resistance, it was defined based on the breakpoints published in the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) guidelines (Version 11.0). Helicobacter pylori ATCC 43,504 was used as quality control. Multidrug resistance (MDR) was defined as resistance to ≥ 3 different classes of antibiotics.

Genomic DNA extraction and whole-genome resequencing

Following manufacturer’s instructions, genomic DNA was extracted from pure cultures using a TIAN-amp bacteria DNA kit (Tiangen, China). DNA quality was assessed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA). In this study, genomic libraries were prepared using a TruSeq PCR-free prep kit (Illumina, USA) and sequenced using the NovaSeq platform (Illumina, USA) with paired end sequencing. The library quality was evaluated using the High Sensitivity DNA Kit (Agilent, USA) on the Agilent Bioanalyzer.

Genome assembly and identification of mutations in resistance-associated genes

Using bwa mem, the high-quality data were aligned to the reference genome, and the alignment parameters followed bwa men’s defaults. Picard 1.107 was used to sort and convert the sam files into bam files, and the “FixMateInformation” command was used to ensure consistency between all Paired-end reads information. Sequencing data generation involves library amplification and cluster formation. These two steps are prone to producing Duplicates, which cannot be used as evidence for variant detection. Use “MarkDuplicates” in Picard software to remove Duplicates, if multiple paired reads have the same chromosomal coordinates after alignment, the paired reads with the highest score are retained. The reads near the Indel are most prone to Mapping errors. In order to minimize the SNPs caused by the Mapping errors, the reads near the Indel need to be re-aligned to improve SNP Calling accuracy. The IndelRealigner command in the GATK program aligns reads near Indels to improve SNP prediction accuracy.

We studied 23 S rRNA and infB for CLR, gryA and gryB for LVX, rdxA、fur and recA for MNZ, pbp1 for AMO, rpoB for RIF, and 16 S rRNA for TET in WGS data. Using ATCC 26,695 (NC_000915.1) as the reference genome, retrieve and compare multiple sequences from annotated genomes to determine the presence of genes and mutations. Cluster analysis is carried out on genes identified with point mutations to determine the correlation between observed mutations and MIC values.

Construction of a phylogenetic tree

A phylogenetic tree is a tree like structure used to represent the distance and proximity of phylogenetic relationships between species within a population. Construct a phylogenetic tree using the Maximum Likelihood algorithm in FastTree software (http://www.microbesonline.org/fasttree/). After the tree construction is completed, verify the reliability of the phylogenetic tree branches (bootstrap, 1000 replicates).

Data analysis

Cohen’s kappa coefficient was used to assess the agreement between phenotype resistance and drug resistance mutations. A kappa coefficient value of < 0.4 was considered low agreement, a value of 0.4 to 0.6 was considered moderate agreement, a value of 0.61 to 0.8 was considered substantial agreement, and a value of 0.81 to 1.0 was considered nearly perfect or perfect agreement. For the drawing of mutation clustering analysis maps and consistency analysis maps, R Version are mainly used. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) software version 22.

Results

Characteristics of strains included in the study

65 H. pylori clinical strains were isolated from gastric biopsy tissues of 115 patients, with a positive rate of 56.5%. Among positive patients, there were 38 males and 27 females, with an average age of 46 years; 75.4% (49/65) of people had college education, and 76.9% (50/65) of people lived in households with three or fewer person; 53.8% (35/65) of the patients had a smoking habit, and 50.8% (33/65) had a drinking habit. They were divided into three groups by gastroscopy, with 43.1% (28/65) of patients with non-atrophic gastritis, 26.2% (17/65) of patients with non-atrophic gastritis with erosion, and 30.8% (20/65) of patients with atrophic gastritis (see Table 1).

Table 1.

The demographics and clinical characteristics of 65 patients with H. Pylori isolates

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Mean age (yr) | 46 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 38(58.5%) |

| Female | 27(41.5%) |

| Education | |

| College or higher | 49(75.4%) |

| Below college | 16(24.6%) |

| Smoking habit | |

| Yes | 35(53.8%) |

| No | 30(46.1%) |

| Alcohol habit | |

| Yes | 33(50.8%) |

| No | 32(49.2%) |

| Family size | |

| ≤ 3 | 50(76.9%) |

| ≥ 4 | 15(23.1%) |

| Disease type | |

| non-atrophic gastritis | 28(43.1%) |

| non-atrophic gastritis with erosion | 17(26.2%) |

| atrophic gastritis | 20(30.8%) |

Genomic level correlation analysis of H. Pylori isolates

Among the 65 DNA samples of H. pylori clinical strains sent for testing, 59 DNAs passed the quality inspection. Whole-genome resequencing was performed on the DNA of the 59 isolates, and genome variations were analyzed. We performed a phylogenetic analysis of the SNPs results, and the results are shown in supplementary Fig. 1. It suggests that although different H. pylori strains have different drug resistance, they may be within the same branch and have a close kinship.

Antibiotic susceptibility

The MIC distribution of six antibiotics against H. pylori strains is shown in Fig. 1. The antibiotic resistance rates are as follows: CLR, 36.9% (24/65); LVX, 29.2% (19/65); MNZ, 63.1% (41/65); AMO, 7.7% (5/65); RIF, 12.3% (8/65); TET, 3.1% (2/65). As shown in Table 2, MDR accounted for 16.9% (11/65) of strains, with a strain being simultaneously resistant to four antibiotics, including CLR, LVX, MNZ and RIF. 6.2% (4/65) of the strains were simultaneously resistant to CLR, LVX, and MNZ.

Fig. 1.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing using the agar dilution method. (a) CLR; (b) LVX; (c) MNZ; (d) AMO; (e) RIF; (f) TET Note: Blue represents sensitive strains, while red represents drug-resistant strains

Table 2.

Profile of phenotype antimicrobial resistance of H. pylori clinical isolates

| Phenotype Susceptibility Profile | Antibiotic | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Susceptibility to all antibiotics | 9 | 13.8 | ||

| Single drug resistance | CLR | 7 | 10.8 | |

| LVX | 2 | 3.1 | ||

| MNZ | 14 | 21.5 | ||

| RIF | 1 | 1.5 | ||

| TET | 1 | 1.5 | ||

| Dual drug resistance | CLR + LVX | 3 | 4.6 | |

| CLR + MNZ | 7 | 10.8 | ||

| LVX + MNZ | 4 | 6.2 | ||

| LVX + RIF | 1 | 1.5 | ||

| MNZ + AMO | 2 | 3.1 | ||

| MNZ + RIF | 3 | 4.6 | ||

| Multidrug resistance | CLR + LVX + MNZ | 4 | 6.2 | |

| CLR + MNZ + AMO | 1 | 1.5 | ||

| CLR + MNZ + RIF | 1 | 1.5 | ||

| LVX + MNZ + AMO | 2 | 3.1 | ||

| LVX + MNZ + RIF | 1 | 1.5 | ||

| LVX + MNZ + TET | 1 | 1.5 | ||

| CLR + LVX + MNZ + RIF | 1 | 1.5 | ||

Mutation analysis using WGS

CLR

CLR is an important component of non-bismuth quadruple therapy, and its resistance rate is increasing globally every year. All CLR resistant strains in this study underwent mutations in the 23 S rRNA gene. Of these, 14 strains exhibited the A2143G mutation with the strongest correlation with CLR resistance. No A2115G, A2144G, G1939A, C2147G, and G2172T mutations were found in the isolated strains. In addition, mutations in A2143G and A2142G were also found in two sensitive strains (Fig. 2b). In this study, both the A2143G mutation and A2142G mutation in the 23 S rRNA gene were associated with CLR resistance. After cluster analysis, no significant correlation was observed between the drug-resistant phenotype and coexisting mutations (Fig. 2a). According to a previous study in Vietnam, the G160A mutation in the infB gene is believed to be associated with CLR resistance in H. pylori. However, this mutation was not found in this study (supplementary Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Distribution and consistency analysis of mutation sites related to CLR resistance in 23 S rRNA gene. (a) Correlation analysis between mutation clustering of 23S rRNA gene and phenotype drug sensitivity results (MIC values) of H. pylori isolates. The clustering of mutations reflects their coexistence within a single genome. Mutations are indicated in red, while no mutations are indicated in blue. The MIC value is displayed on a green scale; (b) Analysis of consistency between MIC values and 23S rRNA mutations

LVX

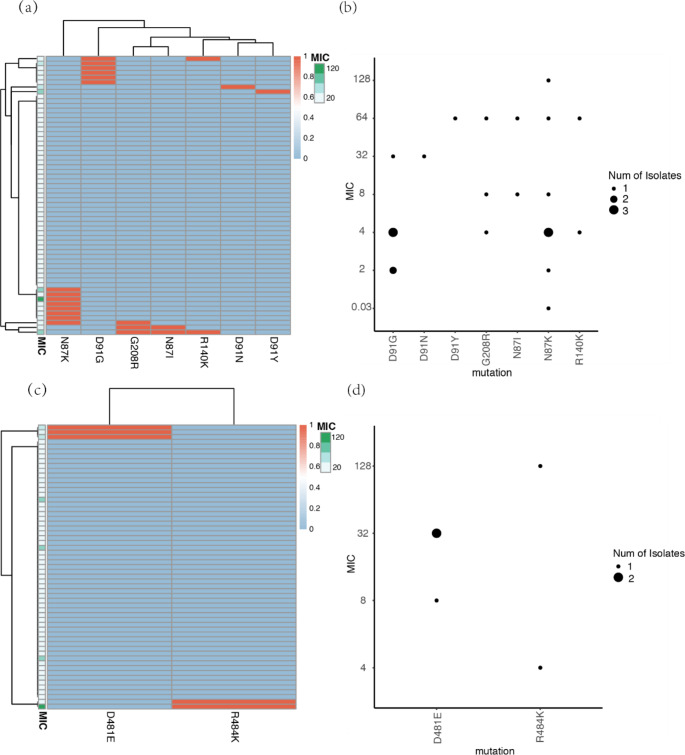

Quinolone antibiotics, such as LVX and moxifloxacin, are one of the drugs used in clinical treatment to eradicate H. pylori. Then, we analyzed the genetic characteristics associated with LVX resistance, mainly including the gyrA gene and gyrB gene. 17 clinical isolates of H. pylori have phenotype resistance to LVX. Resistant mutations (N87I/N87K/D91Y/D91N/D91G) were found in the gyrA gene among them. Two previously reported mutations related to drug resistance, D481E and R484K, were also found in the gyrB gene of five resistant H. pylori strains. In this study, N87K and D91G mutations were detected in the gyrA gene, and D481E mutations in the gyrB gene were associated with LVX resistance (supplementary Table 2). After cluster analysis, no significant correlation was observed between the drug-resistant phenotype and coexisting mutations (Fig. 3a and c). In addition, we found new G208R mutations located in the gyrA gene in all three drug-resistant strains, while no new mutation sites that may be related to drug resistance were detected in the gyrB gene (Fig. 3b and d).

Fig. 3.

Distribution and consistency analysis of mutation sites associated with LVX resistance in gyrA and gyrB genes. (a) Correlation analysis between mutation clustering of gyrA gene and phenotype drug sensitivity results (MIC values) of H. pylori isolates. The clustering of mutations reflects their coexistence within a single genome. Mutations are indicated in red, while no mutations are indicated in blue. The MIC value is displayed on a green scale; (b) Consistency analysis between MIC values and gyrA mutations; (c) Correlation analysis between mutation clustering of gyrB gene and phenotype drug sensitivity results (MIC values) of H. pylori isolates; (d) Analysis of consistency between MIC values and gyrB mutations

MNZ

At present, studies have shown that resistance to MNZ is closely related to the mutation and inactivation of rdxA, fur and recA, but there is no clear conclusion yet. Therefore, we analyzed the mutations of these genes to evaluate their correlation with MNZ resistance. The R16H/C and M21A mutations in the rdxA gene are believed to be most closely related to MNZ resistance. We only found R16H/C mutations in 6 out of 38 phenotype resistant strains, R16C only appeared in resistant strains, and R16H mutations were also detected in 1 sensitive strain. No M21A mutation was found in this study. The N118K mutation in the fur gene only occurs in drug-resistant strains. In addition, several other previously reported mutations related to MNZ resistance were investigated, but we did not find any correlation between them and MNZ resistance in our study (supplementary Table 3). After cluster analysis, no significant correlation was observed between the drug-resistant phenotype and the coexisting mutations in rdxA (Fig. 4a). Due to the presence of only one drug resistance related mutation targeting the fur gene in the isolated strains, cluster analysis cannot be performed on fur. In addition, we identified four new mutations: R176C, K64N, A206T, and L156F in rdxA, which were only present in drug-resistant strains (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

Distribution and consistency analysis of mutation sites related to MNZ resistance in rdxA and fur genes. (a) Correlation analysis between mutation clustering of rdxA gene and phenotype drug sensitivity results (MIC values) of H. pylori isolates. The clustering of mutations reflects their coexistence within a single genome. Mutations are indicated in red, while no mutations are indicated in blue. The MIC value is displayed on a green scale; (b) Consistency analysis of MIC value and rdxA mutation (c) Consistency analysis of MIC value and fur mutation

AMO

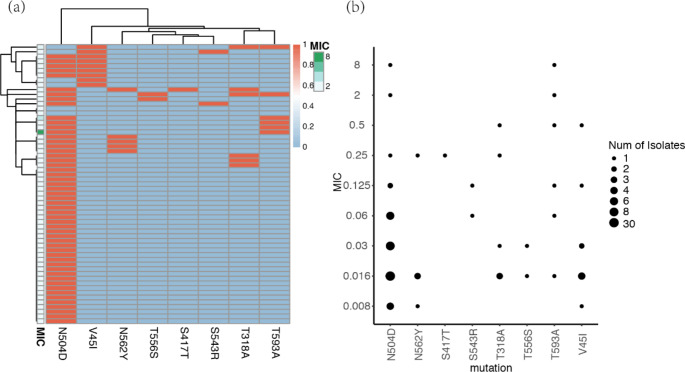

AMO is the most commonly used β-lactam antibiotic in the treatment of H. pylori. The mechanism of drug resistance is mainly related to PBPs, which interferes with the activity of transpeptidase required for crosslinking peptidoglycans. We analyzed pbp1 mutations to evaluate their correlation with AMO resistance. Four H. pylori isolates exhibited phenotype resistance to AMO, and mutations were present in the pbp1 gene. In addition, we also evaluated the reported mutation sites in pbp1 that may be associated with antibiotic resistance. In this study, we found that T593A and T318A mutations were associated with the phenotype of AMO resistance (supplementary Table 4). After cluster analysis, no significant correlation was observed between the drug-resistant phenotype and coexisting mutations (Fig. 5a). In addition, we found the following new mutation: S417T in pbp1, which only appeared in drug-resistant strains (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5.

Distribution and consistency analysis of mutation sites related to AMO resistance in pbp1 gene. (a) Correlation analysis between mutation clustering of pbp1 gene and phenotype drug sensitivity results (MIC values) of H. pylori isolates. The clustering of mutations reflects their coexistence within a single genome. Mutations are indicated in red, while no mutations are indicated in blue. The MIC value is displayed on a green scale; (b) Consistency analysis of MIC values and pbp1 mutations

RIF

The point mutation in the rpoB resistance-determining region (RRDR511 − 612) may lead to its resistance to such drugs [16]. Out of the 7 RIF resistant strains, only 2 had previously reported RRDR mutations (supplementary Table 5). In addition, four novel mutations were observed in the resistant strain RRDR, namely E518D, N587S, D597N, and D610N (Fig. 6b). Cluster analysis revealed that the simultaneous occurrence of D530N and E518D mutations in the rpoB gene may be related to H. pylori high-level resistance to RIF (Fig. 6a).

Fig. 6.

Distribution and consistency analysis of mutation sites related to RIF resistance in rpoB gene. (a) Correlation analysis between mutation clustering of rpoB gene and phenotype drug sensitivity results (MIC values) of H. pylori isolates. The clustering of mutations reflects their coexistence within a single genome. Mutations are indicated in red, while no mutations are indicated in blue. The MIC value is displayed on a green scale; (b) Analysis of consistency between MIC values and rpoB mutations

TET

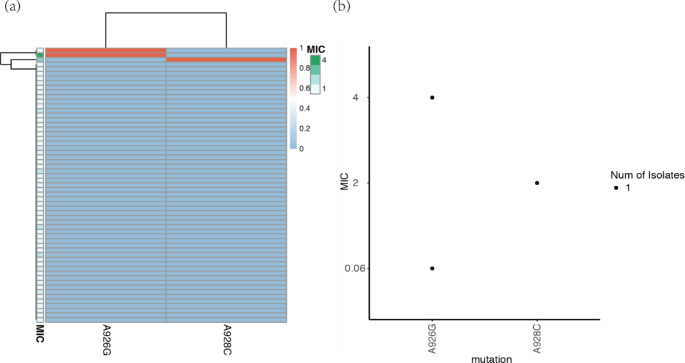

We analyzed the sequencing results of the 16 S rRNA gene and obtained the previously reported mutations that make H. pylori resistant to TET, namely A926G and A928C. In this study, the above two mutations were found in two TET resistant strains, respectively. Among them, the A928C mutation was associated with TET resistance (supplementary Table 6). In addition, the A926G mutation was also observed in a sensitive strain (Fig. 7b). After cluster analysis, no significant correlation was observed between the drug-resistant phenotype and coexisting mutations (Fig. 7a).

Fig. 7.

Distribution and consistency analysis of mutation sites associated with TET resistance in the 16 S rRNA gene. (a) Correlation analysis between mutation clustering of 16 S rRNA gene and phenotype resistance of H. pylori isolates. The clustering of mutations reflects their coexistence within a single genome. Mutations are indicated in red, while no mutations are indicated in blue. The MIC value is displayed on a green scale; (b) Consistency Analysis of MIC Values and 16 S rRNA Mutation

Evaluation of genotype test performance to predict antibiotic resistance

Due to the association between certain mutations in antibiotic resistance related genes and the drug resistance phenotype of H. pylori, we investigated the reliability of using genotypes to predict drug resistance phenotype (Table 3). For CLR, mutations at bases 2142 and 2143 of the 23 S rRNA gene were defined as genotype resistance. Kappa consistency analysis was performed between phenotype resistance and genotype resistance. The Kappa coefficient was 0.931, indicating strong consistency between the resistance genotype and phenotype; For LVX, N87K/I/Y and D91N/G amino acid mutations in the gyrA gene were defined as genotype resistance, and the Kappa coefficient was 0.959, indicating strong consistency between the resistance genotype and phenotype; For MNZ, genotype resistance was defined as a R16H/C amino acid mutation in the rdxA gene. The Kappa coefficient was 0.083, and the consistency was poor. For AMO, the following mutations in the pbp1 gene were used as genotype resistance: three pbp motifs (SAIK368_371, SKN402-404, KTG555-557, and SNN559_561) and three codons located at the C-terminus (A474, T558, T593, and G595). The results showed a Kappa coefficient of 0.503, suggesting moderate consistency between the resistance genotype and phenotype. For RIF, the mutation in RRDR511 − 612 was used as genotype resistance, and the Kappa coefficient was 0.618, indicating substantial agreement between resistance genotype and phenotype. For TET, mutations at the 16 S rRNA gene bases 926–928 were used as genotype resistance, and Kappa consistency analysis was performed with phenotype resistance. The Kappa coefficient was 0.792, indicating substantial agreement between resistance genotype and phenotype.

Table 3.

Agreement between phenotype and genotype resistance

| Antibiotic | MIC(µg/ml) breakpoint |

Genotype | No. of isolates with the following phenotype: |

Kappa coefficient | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resistant | Sensitive | |||||

| CLR | ≥ 1 | Resistant | 21 | 2 | 0.931 | 0 |

| Sensitive | 3 | 33 | ||||

| LVX | > 1 | Resistant | 17 | 1 | 0.959 | 0 |

| Sensitive | 0 | 41 | ||||

| MNZ | > 8 | Resistant | 6 | 1 | 0.083 | 0.210 |

| Sensitive | 32 | 20 | ||||

| AMO | > 0.125 | Resistant | 3 | 4 | 0.503 | 0 |

| Sensitive | 1 | 51 | ||||

| RIF | > 1 | Resistant | 5 | 3 | 0.618 | 0 |

| Sensitive | 2 | 49 | ||||

| TET | > 1 | Resistant | 2 | 1 | 0.792 | 0 |

| Sensitive | 0 | 56 | ||||

Therefore, genotypes perform well in predicting phenotype resistance to CLR and LVX. In our study, genotype testing was found to be effective in predicting phenotype CLR resistance and LVX resistance in H. pylori.

Discussion

For many reasons, antibiotics lose their antibacterial effects on bacteria, including changes in antibiotic targets, decreased enzyme activity in antibiotics, drug efflux pumps, changes in bacterial cell wall permeability, the acquisition of alternative metabolic pathways, excessive production of target proteins, and the formation of biofilms. However, there are many resistance mechanisms that have not been studied in detail or reported in H. pylori. Mutations in antibiotic target genes are considered as the most common drug resistance mechanism of H. pylori, and are also the main problem faced in eradicating H. pylori.

The peptide transferase in the V region of the 23 S rRNA gene domain is the region where H. pylori binds to CLR. Therefore, point mutations occurring in this region will inhibit the binding of macrolide antibiotics to ribosome subunits, thus leading to the emergence of bacterial resistance to macrolide antibiotics [17]. In H. pylori, there are two 23 S rRNA genes. Mutations in either of these two genes lead to the development of its resistance to CLR. As indicated by previous studies, the main mutations associated with CLR resistance are A2143G, A2142G, and A2142C. Several other mutations, such as G1939A, A2115G, A2144G, C2147G and T2182C, have also been reported in different regions. These mutations have been shown to be correlated with CLR resistance. In this study, four mutations that had been confirmed to be associated with drug resistance in previous studies were identified: A2143G, A2142G, A2142C, and T2182C, but only A2143G and A2142G were associated with drug resistance (p < 0.05).

The region in the DNA gyrase sequence where point mutations can occur leading to resistance to LVX is called the quinolone resistance determining region (QRDR). Mutations inhibit the binding of LVX to DNA gyrase and ultimately lead to bacterial resistance to quinolone (or fluoroquinolone) drugs. The most common mechanism of H. pylori resistance to LVX is the point mutation in DNA gyrase (gyrA and gyrB) [18]. The mutation will inhibit the combination of LVX and DNA gyrase, and eventually lead to bacteria resistance to quinolones (or fluoroquinolones). The point mutation of gyrA in the 87th and 91st amino acids, such as N87I, N87K, N87Y, D91Y, D91N and D91G, is the most common cause of H. pylori resistance to quinolones [19, 20]. The gyrB mutation is not considered as a common drug resistance mechanism; However, Rimbara et al. believe that a new mutation at position 463 has led to resistance to quinolones [21]. Other mutations in gyrB, such as S479T, R484K, and E483K, have recently been reported in isolated strains resistant to LVX [22]. Mutations at position 479 and 484 in gyrB are associated with the most common mutations at amino acids 87 and 91 in gyrA. Therefore, it is difficult to determine whether these mutations are responsible for LVX resistance. In this study, it was found that the N87K and D91G mutations in the gyrA gene, as well as the D481E mutation in the gyrB gene, showed statistical differences (p < 0.05) between phenotype resistant and sensitive strains. A novel mutation site G208R was also found in the gyrA gene of three drug-resistant strains. The G208R mutation is hypothesized to disrupt the binding of LVX to its target, DNA gyrase, thereby reducing the drug’s bactericidal effect.

In H. pylori, oxygen insensitive NADPH Nitroreductase (rdxA), NADPH flavin oxidoreductase (frxA) and neurotransmitter like enzyme (frxB) reduce the nitro group of nitroimidazole and convert it into the active form. The development of MNZ resistance is mainly attributed to mutations in rdxA and frxA, which reduce the activity of reductase and lead to insufficient activation of MNZ. Among them, mutations in rdxA are involved in the main mechanism [23]. A novel mechanism attributed to mutations in the iron uptake regulator (fur) is also associated with MNZ resistance. Superoxide dismutase is important for preventing superoxide stress. It is regulated by fur, causing fur mutants with elevated expression levels of superoxide dismutase to exhibit resistance to MNZ. In addition, recombinase A (recA) has also been speculated to be associated with MNZ resistance in previous studies. In this study, four novel mutation sites were also identified that only exist in drug-resistant strains: R176C, K64N, A206T, and L156F in rdxA.

Currently, pbp1, pbp2, and pbp3, are associated with AMO resistance. Mutations in the binding motif sequence of pbp1 and the surrounding amino acids can prevent AMO from binding to pbp1. This is the main reason for its AMO resistance. In this study, it was found that T318A and T593A mutations in pbp1 may be associated with AMO resistance (p < 0.05), and the S417T mutation site was detected only in the AMO resistant strain pbp1.

At present, the resistance rate of H. pylori to rifamycin is relatively low. The rpoB gene encodes the β-subunit of RNA polymerase, and mutations in this gene can cause structural changes that reduce the drug’s ability to bind and inhibit bacterial RNA synthesis. Mutations have been found in codons 530, 538, 540, and 545 of the rpoB gene of its resistant strains. In this study, four new mutation sites were identified that only exist in RIF resistant strains rpoB: E518D, N587S, D597N, and D610N.

Previous studies have found mutations in the 16 S rRNA gene of TET resistant strains at positions 926 to 928, leading to TET resistance in the strains [20, 24]. In this study, it was found that the A928C mutation is a mutation site associated with TET resistance.

By calculating the consistency between phenotype and genotype resistance of various antibiotics, we found that there is strong consistency between phenotype and genotype resistance to CLR and LVX. In the future, we can predict the phenotype resistance of antibiotics by detecting the mutation types of corresponding resistance genes.

Through whole-genome resequencing of H. pylori clinical strains, 10 mutations were identified that only exist in drug-resistant strains, which may be associated with drug resistance to LVX, MNZ, AMO, and RIF, respectively. Research has shown strong consistency between genotype and phenotype resistance to CLR and LVX. This indicates that detecting mutation types can predict H. pylori resistance to CLR and LVX.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

YW contributed to the draft of the manuscript, and performed the experiment; TJ contributed to the conception of the study and draft of the manuscript; XL contributed to the sample collection, and performed the data analyses; RS worked on data analysis and interpretation; XZ contributed to the data interpretation; JH revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work received no specific grant from any funding agency.

Data availability

The data generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethical approval

The study was undertaken in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration principles. Ethical approval for this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Emergency General Hospital. All human subjects provided informed consent before participation in the study.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yaxuan Wang, Tiantong Jiang, Xiaochuan Liu and Rina Sa contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Eusebi LH, Zagari RM, Bazzoli F (2014) Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter 19(Suppl 1):1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hooi JKY et al (2017) Global prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection: systematic review and Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 153(2):420–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malfertheiner P et al (2022) Management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht VI/Florence consensus report. Gut [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Helicobacter pylori Study Group, Chinese Society of Gastroenterology, Chinese Medical Association (2022) Sixth Chinese national consensus report on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection (treatment excluded). Chin J Dig 42(5):289–303 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graham DY, Liou JM (2022) Primer for Development of guidelines for Helicobacter pylori Therapy using Antimicrobial Stewardship. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 20(5):973–983e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pohl D et al (2019) Review of current diagnostic methods and advances in Helicobacter pylori diagnostics in the era of next generation sequencing. World J Gastroenterol 25(32):4629–4660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gong Y, Yuan Y (2018) Resistance mechanisms of Helicobacter pylori and its dual target precise therapy. Crit Rev Microbiol 44(3):371–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roldan IJ, Castano R, Navas MC (2019) Mutations in the Helicobacter pylori 23S rRNA gene associated with clarithromycin resistance in patients at an endoscopy unit in Medellin, Colombia. Biomedica, 39(Supl. 2): pp. 117–129 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Seo SI et al (2019) Helicobacter pylori Eradication according to sequencing-based 23S ribosomal RNA Point Mutation Associated with Clarithromycin Resistance. J Clin Med, 9(1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Domanovich-Asor T et al (2020) Genomic Analysis of Antimicrobial Resistance genotype-to-phenotype agreement in Helicobacter pylori. Microorganisms, 9(1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Maljkovic Berry I et al (2020) Next generation sequencing and Bioinformatics Methodologies for Infectious Disease Research and Public Health: approaches, applications, and considerations for development of Laboratory Capacity. J Infect Dis 221(Suppl 3):S292–S307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tuan VP et al (2019) A next-generation sequencing-based Approach to identify genetic determinants of Antibiotic Resistance in Cambodian Helicobacter pylori Clinical isolates. J Clin Med, 8(6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Zhao S et al (2016) Whole-genome sequencing analysis accurately predicts Antimicrobial Resistance Phenotypes in Campylobacter spp. Appl Environ Microbiol 82(2):459–466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karlsson PA et al (2021) Molecular characterization of Multidrug-Resistant Yersinia enterocolitica from Foodborne outbreaks in Sweden. Front Microbiol 12:664665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cirillo DM, Miotto P, Tortoli E (2017) Evolution of phenotypic and molecular drug susceptibility testing. Adv Exp Med Biol 1019:221–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tshibangu-Kabamba E, Yamaoka Y (2021) Helicobacter pylori infection and antibiotic resistance - from biology to clinical implications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 18(9):613–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tran VH et al (2019) Characterisation of point mutations in domain V of the 23S rRNA gene of clinical Helicobacter pylori strains and clarithromycin-resistant phenotype in central Vietnam. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 16:87–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Subsomwong P et al (2022) Next-generation sequencing-based study of Helicobacter pylori isolates from Myanmar and their susceptibility to antibiotics. Microorganisms, 10(1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Saranathan R et al (2020) Helicobacter pylori infections in the Bronx, New York: surveying Antibiotic susceptibility and strain lineage by whole-genome sequencing. J Clin Microbiol, 58(3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Mannion A et al (2021) Helicobacter pylori Antimicrobial Resistance and Gene variants in High- and low-gastric-Cancer-risk populations. J Clin Microbiol, 59(5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Rimbara E et al (2012) Fluoroquinolone resistance in Helicobacter pylori: role of mutations at position 87 and 91 of GyrA on the level of resistance and identification of a resistance conferring mutation in GyrB. Helicobacter 17(1):36–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miftahussurur M et al (2016) Surveillance of Helicobacter pylori Antibiotic susceptibility in Indonesia: different resistance types among regions and with Novel genetic mutations. PLoS ONE 11(12):e0166199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanih NF, Ndip LM, Ndip RN (2011) Characterisation of the genes encoding resistance to metronidazole (rdxA and frxA) and clarithromycin (the 23S-rRNA genes) in South African isolates of Helicobacter pylori. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 105(3):251–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hulten KG et al (2021) Comparison of Culture with Antibiogram to Next-Generation sequencing using bacterial isolates and Formalin-Fixed, paraffin-embedded gastric biopsies. Gastroenterology 161(5):1433–1442e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.