Abstract

Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) stands as a prevalent bacterial cause of global diarrheal incidents. ETEC’s primary virulence factors encompass the B subunit of the Heat Labile Enterotoxin, along with the adhesion factors CfaB and EtpA. In this study, we isolated IgY antibodies against the three virulence factors individually, in pairs, and as triple cocktails. The in vitro efficacy of these IgY antibodies was examined, focusing on inhibiting heat-labile enterotoxin (LT) toxin cytotoxicity and impeding ETEC adherence to HT29 cells. Assessing the impact of IgY-treated bacteria on intestinal epithelial cells utilized the standard ileal loop method. Results demonstrated that the anti-LTB IgY antibody at 125 µg/ml and IgY antibodies from double and tertiary cocktails at 200 µg/ml effectively inhibited LT toxin attachment to the Y1 cell line. Pre-incubation of HT29 intestinal cells with specific IgYs reduced bacterial attachment by 59.7%. In the ileal loop test, toxin neutralization with specific IgYs curtailed the toxin’s function in the intestine, leading to a 74.8% reduction in fluid accumulation compared to control loops. These findings suggest that egg yolk immunoglobulins against recombinant proteins LTB, CfaB, and EtpA, either individually or in combination, hold promise as prophylactic antibodies to impede the functioning of ETEC bacteria.

Keywords: Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli, Heat labile enterotoxin, Passive immunotherapy, IgY, Egg yolk immunoglobulin

Introduction

Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) stands out as a major contributor to traveler’s diarrhea, intestinal inflammation, and fatalities in children under the age of 5, resulting in an annual toll of 300,000 to 500,000 deaths [1]. ETEC engages with intestinal epithelial cells through colonization factors (CFs) and the EtpA adhesin, triggering pathogenesis by releasing heat-labile enterotoxin (LT) and heat-stable enterotoxin (ST) [2]. Prior research has explored these virulence factors as potential candidates for an ETEC vaccine, aiming to reduce antibiotic usage, the prevailing method for treating bacterial infections [3, 4]. Recently, the world health organization (WHO) reassert that ETEC due to a significant Anti-Microbial-Resistance threat is a vaccine priority [5]. Despite recent endeavors to develop an ETEC vaccine utilizing live attenuated ETEC, an effective vaccine remains absent from the market [6]. Consequently, the quest for safe and potent antibiotic alternatives to thwart ETEC infection emerges as an imperative and noteworthy undertaking. Avian antibodies, specifically IgYs, present themselves as a promising passive immunotherapy, holding the potential to alleviate concerns related to antibiotic and antimicrobial resistance [7]. Antigen-specific antibodies, found in the egg yolk of chickens and known as IgY, offer a valuable means to prevent pathogenic infections in food, humans, and animals. IgY, in comparison to other antibody types, boasts several advantages, including a hygienic and non-invasive production process, absence of antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) reactions or complement activation upon human injection, stability, and high avidity [8]. Consequently, passive immunization through IgY is regarded as an appealing strategy for preventing and treating various pathogens such as rotavirus, epidemic diarrhea virus, coronavirus, and gastroenteritis virus [9, 10]. The mechanism involves IgY binding to bacteria or their toxins, hindering their attachment to host cells and thereby preventing colonization and subsequent damage to target cells. Notably, oral administration of IgY has proven to be a successful treatment for ETEC [11]. Passive immunotherapy using antigen-specific IgY against prevalent antigens in various ETEC strains holds promise as an efficient approach for achieving universal prophylactic effect. Three key antigenic factors in ETEC, namely the heat-labile enterotoxin B subunit, CFaB (the major subunit of CFA/I), and EtpA (a secretory glycoprotein of ETEC flagella), play crucial roles in bacterial binding and colonization on the surface of intestinal epithelial cells. These factors are considered protective candidates for an ETEC vaccine [12, 13]. Immunization with EtpA has been shown to induce humoral immunity and significantly reduce ETEC H10407 colonization in mice, suggesting its potential as an effective target for ETEC immunization [14]. The objective of this study was to produce polyclonal IgY against recombinant proteins of LTB, CfaB, and EtpA, as well as their binary and tertiary cocktails. Subsequently, the antibody titer and the protective effects of the produced IgY were evaluated, focusing on inhibiting colonization, adhesion, and the toxin effects of heat-labile enterotoxin in both in vitro and animal models.

Materials and methods

Expression and purification of CfaB, LTB, and EtpA proteins

The genes encoding LTB and CfaB were subcloned into pET28a, and the gene for EtpA was cloned into pET32 plasmids. Following transformation into Escherichia coli BL21, DE3, positive colonies were selected on LB agar plates supplemented with 80 µg/ml kanamycin. Subsequently, the recombinant clones were individually cultured in 200 ml LB broth medium with 50 µg/ml kanamycin at 37 °C until reaching an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.5–0.6. Induction with 1 M isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was then carried out, with the culture containing LTB or CfaB recombinant clones incubated at 37 °C for 5 h, and the EtpA clone grown at 25 °C for 12 h.

Post-induction, cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 rpm for 10 min. The resulting pellet was resuspended in phosphate buffer (100 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM Tris-HCl) and subjected to ultrasonication for lysis. Purification of the CfaB protein was accomplished through the native method employing a Ni-NTA column (Qiagen, Netherlands), following the manufacturer’s instructions. For LTB and EtpA, purification from inclusion bodies involved suspending the recombinant cells’ pellet in TE buffer, sonication, and subsequent centrifugation at 13,000 × g/4°C for 15 min. The pellet was washed with TE buffer, suspended in buffer B containing 8 M urea, and shaken for 45 min. Following another centrifugation step, the supernatant containing unfolded proteins was isolated for refolding through dialysis with a cut-off of 12 kDa. The quality and identity of the LTB, CfaB, and EtpA recombinant proteins were assessed using SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting assays, respectively. The total protein concentration of LTB, CfaB, and EtpA was determined using the Bradford method.

Development of chicken egg yolk antibody (IgY)

To produce egg antibodies, 5-month-old White Leghorn hens were acquired from the Razi Institute in Tehran, Iran. The animals were housed under standard conditions with unrestricted access to food and water, cared for by trained personnel, and immunized following the protocol outlined by Yokoyama et al. [15]. All procedures in this study adhered to national and international standards for the ethical care and use of laboratory animals, receiving approval from the ethics committee for animal use at Shahed University (IR.SHAHED.REC.967586400). In summary, the vaccine was prepared by combining 100 µg of each protein or binary or tertiary cocktails in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), emulsified in 500 µl of Montanide adjuvant (Seppic, France), with a total volume of 1000 µl. Hens were immunized by injecting 0.5 ml into each breast muscle, with three boosters administered at 14-day intervals (Table 1). Eggs from immunized hens were collected before and 10 days after each booster and 45 days after the final booster. The collected eggs were stored at 4 °C. Egg yolk was carefully separated from the albumin and yolk membrane. The water-soluble fraction of the yolk was prepared using the method described by Akita et al. [16]. Briefly, the pH of diluted yolk, diluted sevenfold in distilled water, was adjusted to 4.0 using 0.5 M HCl and stored at -4 °C for 3 days. After defrosting and filtration through a Teflon filter cloth, NaCl was added to achieve a final concentration of 8.8%. The solution’s pH was adjusted to 4.0 and stirred for 2 h at 4 °C. Following centrifugation for 20 min at 4 °C/3400 × g, the supernatant and pellet were isolated for analysis by SDS-PAGE and western blotting. Control IgY was prepared from the eggs of non-immunized hens using the same method.

Table 1.

Immunization program

| Group | Antigen concentration | Montanide adjuvant | Total volume |

|---|---|---|---|

| LTB | 100 µg | 700 µl | 1 ml |

| CfaB | 100 µg | 700 µl | 1 ml |

| EtpA | 100 µg | 700 µl | 1 ml |

| EtpA-LTB | 100 µg EtpA + 100 µg LTB | 700 µl | 1 ml |

| EtpA-CfaB | 100 µg EtpA + 100 µg CfaB | 700 µl | 1 ml |

| EtpA- CfaB-LTB | 100 µg EtpA + 100 µg CfaB + 100 µg LTB | 700 µl | 1 ml |

| Control | 300 µl PBS | 700 µl | 1 ml |

IgY titer assay in egg yolk by indirect ELISA

To assess the IgY antibody titers specific to LTB, CfaB, and EtpA proteins, an indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was employed. Purified recombinant proteins were diluted to 50 µg/ml in carbonate buffer (pH: 9.6) and utilized to coat the wells of a polystyrene plate (100 µl/well). Following incubation at 4 °C overnight, the plates underwent three washes with PBST and were then blocked with 5% skim milk in PBST for 1 h at 37 °C. Subsequently, the plates were incubated with 5 µg/well of purified IgY for 2 h at 37 °C. After washing, anti-IgY HRP conjugate obtained from Abcam company was added (100 µl/well) at an appropriate dilution. Following a 1-hour incubation at 37 °C, the plates were washed, and 100 µl of 3, 3´, 5, 5´-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) solution was added to each well. The reaction was halted by adding 100 µl of 3 N sulfuric acid/well, and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm. Additionally, a whole-cell ELISA was conducted using 108 CFU of ETEC on each well to validate the specificity of the IgY against the surface proteins of EtpA and CfaB.

LT toxin isolation from ETEC

The LT toxin from the ETEC S10407H A strain was isolated using a method adapted from Tsuji et al. [17]. In a concise procedure, a 25 ml ETEC bacterial culture was incubated at 37 °C for 3 h until reaching an OD600nm of 0.48. Following centrifugation at 3000 × g for 15 min, the bacterial pellet was suspended in PBS and sonicated at 4 °C. The resulting supernatant containing the LT toxin was filtered through a 0.22-micron filter (MilliporeSigma, USA) and stored at -4 °C. To quantitatively assess the cytotoxic effect of the isolated LT toxin, the Y1 cell line was employed in vitro. The Y1 cell line was exposed to 50 µl of various concentrations of LT toxin in 150 µl DMEM medium for 12 h. Subsequently, the medium was discarded, and the cells were washed with PBS. The cells were stained to examine the rate of morphological changes, transitioning from a spindly to a round shape indicative of LT dose-dependent cell death. The concentration of LT toxin resulting in 50–70% cell death was selected for use in the toxin inhibition assay.

In vitro LTB toxin inhibition assay

To assess the inhibitory effects of IgY in vitro, the LTB toxin inhibition assay was conducted following the protocol outlined by Xu et al. [18]. The Y1 cell line was cultured in DMEM medium containing 10% FBS. Subsequently, 105 cells were seeded into each well of a 24-well plate (SPL, Korea) and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 until reaching 70% confluency. Various concentrations of IgY, purified from the egg yolks of different immunized groups, were then incubated with the IC50 of LT at 37 °C for 90 min. Following this, the Y1 cells were treated with 50 µl of the IgY-LT toxin mixture in 150 µl complete DMEM medium and incubated for 12 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Subsequently, cells were washed three times with PBS, fixed with methanol for 5 minutes, and stained with Giemsa stain. The morphological features of the treated cells were examined using inverted microscopy. Treated Y1 cells with LT toxin and PBS served as positive and negative controls, respectively. This assay was repeated three times for each IgY concentration to ensure result accuracy.

In vitro adhesion inhibition activity of anti-LTB, CfaB, and EtpA IgY

Following the toxin inhibition assays, we proceeded to evaluate the anti-adhesion activity of purified IgY against ETEC colonization on the HT29 cell line. The HT29 cell line was cultured in RPMI medium containing 10% FBS. Subsequently, 105 cells were seeded into each well of a 24-well plate (SPL, Korea) and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 until reaching 70% confluency. To assess the anti-adhesion activity, 5 × 108 CFU of ETEC was added to various concentrations of purified IgY, ranging from 100 to 5000 µg/ml, isolated from different immunized groups. The mixture was incubated with shaking at 37 °C for 75 min. Following washing with PBS, cells were incubated with the ETEC and IgY mixture for 3 h. To eliminate unattached bacteria, each well was washed with PBS, and after trypsinization, the count of attached ETEC on the surface of HT29 cells was determined by culturing on LB agar plates.

Animal challenge

To assess the inhibitory effect of purified IgY on ETEC colonization in vivo, an animal challenge was conducted following previously established procedures [19, 20]. Briefly, 6-week-old New Zealand rabbits weighing 1.5 kg were individually separated and fasted for 36 h before the surgery. Anesthesia was induced by intramuscular injection of ketamine (35 mg per kg body weight) and xylazine 2% (5 mg/kg). A small incision was made in the abdomen, and loops measuring 3 cm in length were isolated in the distal ileum using sutures. Each closed ileal loop was perfused with 200 µl of a 5 × 106 CFU ETEC H10408 suspension, incubated with 0.5 and 1.5 mg/ml of isolated IgY from different groups for 1 h. After 18 h post-incubation, the rabbits were sacrificed, loops were isolated, and the weight-to-length ratio (g/cm) was calculated. ETEC bacteria incubated with non-immunized hen eggs served as the negative control (Table 2).

Table 2.

Ileal loop challenge using IgY isolated from immunized hens’ egg and ETEC bacteria

| Loop number | Groups | IgY concentration (mg ml− 1) | ETEC bacteria (CFU) | Total volume (µl) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | PBS | - | - | 200 |

| 1 | C-IgY | 1.5 | 5 × 106 | 200 |

| 2 | ETEC | - | 5 × 106 | 200 |

| 3 | LTB | 0.5 | 5 × 106 | 200 |

| 4 | LTB | 1.5 | 5 × 106 | 200 |

| 5 | EtpA-LTB | 0.5 | 5 × 106 | 200 |

| 6 | EtpA-LTB | 1.5 | 5 × 106 | 200 |

| 7 | EtpA-CfaB-LTB | 0.5 | 5 × 106 | 200 |

| 8 | EtpA-CfaB-LTB | 1.5 | 5 × 106 | 200 |

Statistical analysis

All data were presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis of data from different groups was performed using the One-way ANOVA and Duncan test. Differences with a P value < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. SPSS22 software and GraphPad Prism 6.0 were utilized for the statistical analyses.

Results

EtpA, LTB, and CfaB expression and purification

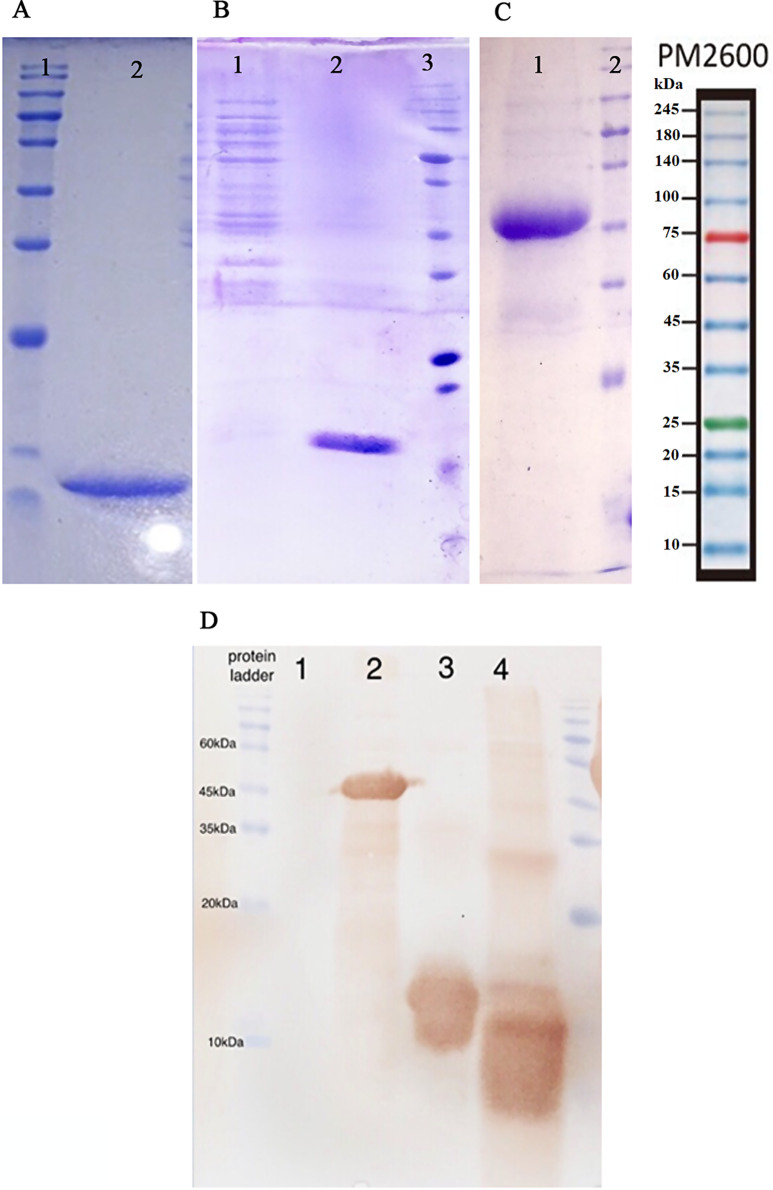

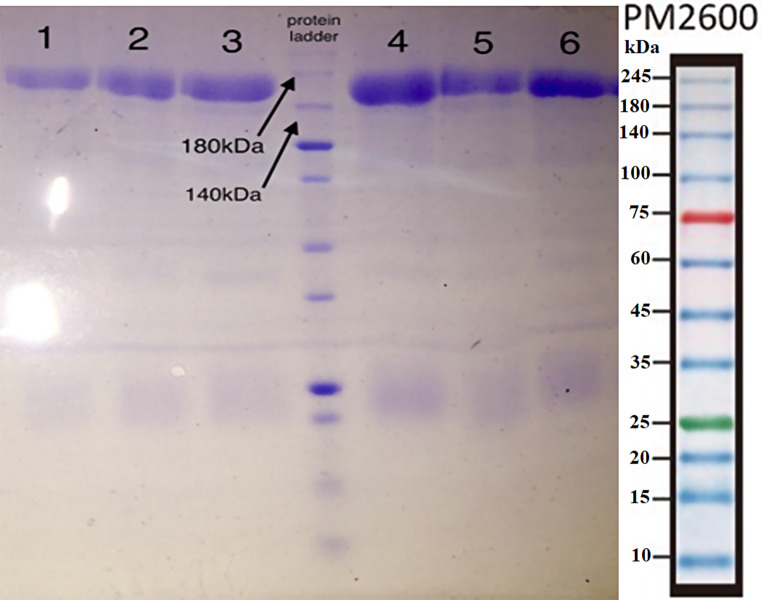

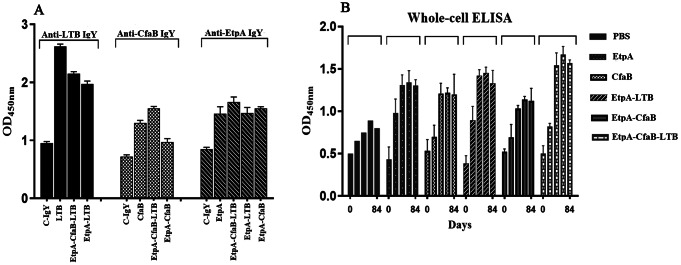

In our investigation, recombinant LTB, CfaB, and EtpA proteins with molecular weights of 14, 49, and 16 kDa, respectively, were successfully purified from Escherichia coli by inclusion body refolding and Ni-NTA column chromatography (Fig. 1). Their identity was confirmed through western blotting (Fig. 1). Following intramuscular injection of 100 µg of each protein or binary or tertiary cocktails in PBS mixed with 500 µl of Montanide adjuvant in hens, with three boosters administered, sera and eggs were collected from immunized hens. The purity and the size of IgY were monitored by SDS-PAGE technique (Fig. 2). IgY titers in both sera and egg yolk were measured by indirect ELISA, utilizing purified proteins and whole-cell ELISA with 108 CFU of ETEC bacteria. The ELISA results demonstrated a significant increase in antibody titers compared to the control group, particularly in the tertiary and binary cocktail groups (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Verifying the LTB, EtpA, and CfaB protein expression through SDS-PAGE 12%. (A) lane 1: protein marker, lane 2: LTB protein purified (14 kDa) from inclusion bodies; (B) lane 1: negative control (protein content of the E. coli BL21 lacking plasmid), lane 2: EtpA protein (16 kDa) purified from inclusion bodies, lane 3: protein marker; (C) lane 1; CfaB protein (49 kDa) purified using Ni-NTA column, lane 2: protein marker; (D) western blot of lane 1: negative control, lane 2: CfaB, lane 3: EtpA, lane 4: LTB proteins

Fig. 2.

The IgY extraction from egg yolk of immunized hens with recombinant LTB, EtpA, and CfaB proteins and binary and tertiary cocktails; lane 1: anti-LTB IgY; lane 2: anti-CfaB IgY; lane 3: anti-EtpA IgY; lane 4: anti-EtpA-CfaB IgY; lane 5: anti-EtpA-LTB IgY; lane 6: anti-EtpA-CfaB-LTB IgY

Fig. 3.

ELISA results for the anti-LTB, anti-EtpA, and anti-CfaB IgY and binary and tertiary groups raised against LTB, EtpA, and CfaB proteins (A), and the whole ETEC strain on different days of 0, 14, 28, 42, and 82 (B). Values represent the mean of triplicate independent experiments ± standard division of the mean (SD). Differences with a P value < 0.05 were considered statistically significant

Isolated IgY could inhibit LTB toxin in vitro

The purified LT toxin, at a 1/40 dilution, induced morphological changes in 50–70% of the Y1 cell line, transitioning from a spindly to a round shape. In the LTB toxin inhibition assay, 105 Y1 cells were exposed to various concentrations of IgY, incubated with a 1/40 dilution of LT toxin for 12 h at 37 °C. Purified IgY against LTB at a concentration of 125 µg/ml, as well as 200 µg/ml of anti-LTB-EtpA and the tertiary cocktail of three recombinant proteins, demonstrated the ability to inhibit the toxic effects of LT toxin at its IC50. Conversely, lower concentrations of IgY were insufficient to prevent the morphological changes in the Y1 cell line induced by the LT toxin (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Inhibitory effect of IgY isolated from various immunized groups on morphological changes of Y1 cells pretreated with (A) PBS, (B) LT in 1/40 dilution, (C) LT mixed with 425 µg of C-IgY, (D) LT mixed with 125 µg of anti-LTB IgY, (E) LT mixed with 200 µg of anti-EtpA-LTB IgY, (F) LT mixed with 200 µg of anti-EtpA-CfaB-LTB IgY

In vitro adhesion inhibition activity of anti-LTB, CfaB, and EtpA IgY

The anti-adhesion activity of isolated IgY against ETEC colonization on the HT29 cell line was evaluated by treating bacteria with various concentrations of purified IgY from different groups. IgY targeting colonization factors LTB-CfaB-EtpA, LTB-EtpA, and CfaB-EtpA, at concentrations of 1000, 2000, and 5000 µg/ml, effectively inhibited ETEC colonization on the surface of HT29 cells compared to control groups. Untreated ETEC and bacteria treated with IgY purified from the control group served as negative controls (Table 3). The adhesion coefficient of ETEC to the HT29 cell line was calculated using the formula:

Table 3.

In vitro adhesion inhibition activity of isolated IgY (1000 µg ml− 1) on ETEC attachment to HT29 cells

| Group | Number of test colonies | Number of control colonies | Adhesion coefficient | % Adhesion inhibition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EtpA-CfaB-LTB | 116 | 278 | 41/7 | 58/3 |

| EtpA-CfaB | 137 | 278 | 49/3 | 50/7 |

| EtpA-LTB | 230 | 278 | 82/7 | 17/3 |

| C-IgY | 264 | 278 | 94/6 | 5/04 |

Adhesion coefficient = (Number of bacterial colonies in test group/number of colonies in control group) × 100.

The anti-CfaB-EtpA-LTB cocktail demonstrated a 58.3% inhibition of ETEC attachment to the HT29 cell line.

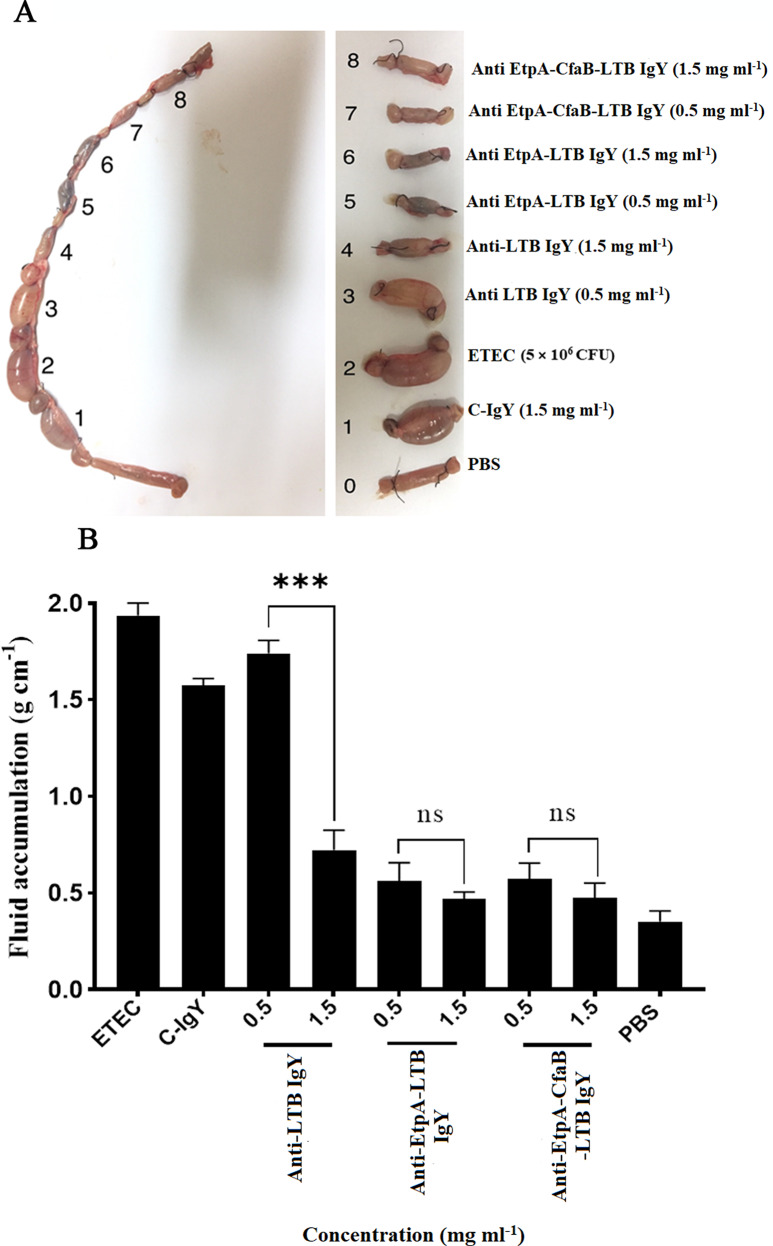

IgY protection against ETEC colonization in challenge route

To assess the protective efficacy of isolated IgYs against ETEC colonization in the ileal loop challenge, experiments were conducted using the ileum of unimmunized 6-week-old New Zealand rabbits. Briefly, 36 h fasted rabbits were anesthetized by Ketamine/Xylazine intraperitoneal injection. After making a midline incision in the abdomen, 3 cm loops were isolated in terminal ileum by suture. Each closed ileal loop was perfused with 200 µl saline containing 5 × 106 CFU of ETEC H10408 without any treatment or treated with 0.5 and 1.5 mg/ml IgY of LTB, CfaB-EtpA-LTB, and EtpA-LTB groups. After 12 h, ileal loops were taken out for evaluation of weight/length ratio. Weight/length proportion of at least 0.1 g cm-1 were considered as positive response to diarrhea. The IgYs targeting binary and tertiary cocktails demonstrated the ability to induce protection against 5 × 106 CFU of ETEC at a concentration of 0.5 mg/ml (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Ileal loop assay, (A) 5 × 106 CFU of ETEC bacteria incubated with different doses of specific IgY antibodies were injected into each loop. After 18 h, fluid accumulation ratio (g cm− 1) was measured. C-IgY and PBS were considered negative controls and ETEC as positive control; (B) The results were expressed as mean ± SD, n = 3, and the letters show a significant difference between the columns for each dose with a P value < 0.05, ns, not significant. C-IgY, control IgY; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline

Discussion

E. coli is a part of the normal flora with several pathotypes causing extraintestinal and enteric infections like diarrhea, sepsis, meningitis, and urinary tract infections [21]. Passive immunization using polyclonal antibodies can provide a prophylaxis against diarrheal illness as an alternative to active immunization especially in short-term traveler. Animal Studies suggest that targeting enteropathogens using IgY act as an effective approach in preventing and treatment of diarrhea. Simultaneous immunization of hens with multiple antigens, induce polyvalent IgYs disparting several steps of pathogenesis process [22]. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) poses a significant threat, causing severe intestinal inflammation, diarrhea, and mortality, particularly in young animals and human infants [1]. The present study aimed at developing a multi-valent passive immunotherapy agent by targeting colonization factors (CFs), toxins, and antigens such as EtpA to counteract both toxicity and bacterial adherence. Despite existing adhesion-based bispecific IgYs offering partial protection through adhesion inhibition, there is a noticeable absence of a universally effective commercial ETEC immunotherapy against ETEC-induced diarrhea [6]. Based on statistical measures passive immunization with IgY is an effective prophylactic and therapeutic approach against diarrheagenic E. coli [23]. Immunogens capable of eliciting broadly neutralizing antibodies that target conserved epitope domains on the bacterial surface present promising candidates for a universal immunotherapy agent. In a related study, Yang et al. employed a computational model to explore antibody evolution through affinity maturation following immunization with two types of immunogens: a heterotrimeric “chimera” hemagglutinin enriched for the receptor-binding site (RBS) epitope and a cocktail comprising three non-epitope-enriched homotrimers of the chimera’s monomers. The results indicated that immunization with the chimera and cocktail immunogens induced cross-reactive RBS-directed B cells, with the chimera demonstrating superior quantitative performance over the cocktail [24]. The observed results appear to be a consequence of the intricate interplay between how B cells engage with these antigens, coupled with their interaction with diverse helper T cells, necessitating T cell-mediated selection of germinal center B cells [25]. In our previous study [26], an IgY targeting the CfaB-EtpA-LTB chimera was developed, confirming the antigenicity of this chimera and its effectiveness in inhibiting ETEC colonization both in vitro and in vivo. In this parallel investigation, we explored the bacteriostatic activity of IgY against the CfaB-EtpA-LTB cocktail and its impact on ETEC H10408 colonization in vitro. Additionally, we evaluated the protective effects of IgY against ETEC infection in vivo. The results indicated that IgY against LTB toxin and binary and tertiary cocktails were effective in reducing colonization and intestinal inflammation associated with ETEC infection in rabbits. The yield of purified IgY antibodies, obtained through water dilution and salt precipitation, reached 12 mg/ml, falling within a similar range as reported in previous studies and surpassing the polyethylene glycol method, which yielded 5 mg/ml [27]. Hens were intramuscularly injected with 100 µg of each antigen in a single group, 200 µg in total across double groups, and 300 µg in tertiary groups—a dosage range reported as optimal by Chalghoumi et al. [6]. ELISA results, utilizing three antigens, affirmed the specific binding of IgY to the corresponding antigens in each group. The IgY titer peaked after the third injection, consistent with previous studies [15, 26]. Incorporating whole cell ELISA, it was discerned that 5 µg of IgY against double and tertiary cocktails demonstrated the ability to detect ETEC bacteria by binding to surface antigens EtpA and CfaB. Immunoblot analysis further confirmed the immunoreactivity of IgY antibodies against the corresponding antigens. These findings were consistent with the chimeric protein CEL reported in our prior study [26]. To assess the potency of specific IgYs in inhibiting the function of the LT toxin on Y1 cells, different IgY dilutions were employed. Anti-LTB IgY at 125 µg/ml effectively neutralized the toxic effects of LT toxin on the Y1 cell line. Notably, for IgY obtained from double and tertiary cocktails, a concentration of 200 µg/ml was required for neutralization. This is in contrast to the 750 µg/ml concentration of anti-CEL IgY reported by Mohammadkhani et al. [26]. The demonstrated neutralizing activity of IgY suggests that the antibody effectively recognized the pentameric B subunit of the LT toxin, inhibiting the toxin’s binding to the GM1 receptor. This insight underscores the crucial role of the anti-LTB antibody in impeding the intracellular increase of cAMP and preventing morphological changes in cells from a spindly to a round shape [28]. Results from the adhesion inhibition assay unveiled that anti-CfaB-LTB-EtpA IgY could effectively prevent the attachment of ETEC bacteria to HT29 cells in a dose-dependent manner, particularly at concentrations ranging from 1000 to 5000 µg/ml. Notably, at a concentration of 1000 µg/ml, anti-CfaB-LTB-EtpA IgY exhibited a substantial 58.3% inhibitory effect compared to the control group. This indicates that IgY antibodies raised against the double cocktail of CfaB-EtpA binding factors could significantly inhibit bacterial adhesion by binding to the virulence factors present on the surface of ETEC bacteria. In our prior study, 2 mg/ml of anti-CEL IgY showed a 74% inhibitory effect on ETEC attachment to HT29 cells [26]. In a similar study, Reddy et al. reported that 150 mg/ml of anti-CFA/I IgY inhibited ETEC bacterial adhesion by 60% [29]. Moreover, pretreatment with 50 mg of specific IgY or egg yolk powder demonstrated efficacy in inhibiting the adhesion of E. coli K88 to intestinal mucosal cells in pigs, offering protection against diarrhea [30]. The ileal loop assay demonstrates that this antibody neutralized the toxin and prevented the fluid accumulation in rabbit ileal loops in a dose-dependent manner spcifically in two concentrations of 0.5 and 1.5 mg/ml of IgY incubated with 5 × 106 CFU of ETEC bacteria. Notably, at a concentration of 1.5 mg/ml of IgY against double and tertiary cocktails, a remarkable inhibitory effect of 75% was observed compared to the control group, while it slightly decreased to 70% at 0.5 mg/ml. Comparing these results with anti-CEL IgY, which demonstrated an 80% inhibitory effect at 2 mg/ml, confirmed the superior protective efficacy of the tertiary cocktail over the chimeric protein in inhibiting ETEC toxicity and colonization both in vitro and in vivo. Importantly, as there was no significant difference in the efficiency of IgY obtained from double and tertiary cocktails, it suggests that the antibody against colonization factors could effectively inhibit bacterial attachment, preventing diarrhea caused by ETEC. In conclusion, the findings strongly suggest that passive immunotherapy using an anti-CfaB-LTB-EtpA cocktail of IgY antibodies holds promise as an efficient treatment against ETEC-induced intestinal infections. This treatment strategy works by decreasing colonization and neutralizing the LT toxin’s effects on intestinal epithelial cells.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Deputy Research, Shahed University, Tehran, Iran for financial support.

Authors’ Contributions

Maryam Mafi (Investigation, Methodology), Razieh Rezaei Adriani (Data curation, Software, Writing original draft), Fatemeh Mohammadkhani (Investigation, Data curation), Seyed Latif Mousavi Gargari (Project administration, Validation, Data Curation). All authors reviewed the final version and approved it.

Funding

The authors wish to thank Deputy Research, Shahed University, Tehran, Iran for financial support.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Declarations

Ethics approval

All the animal experiments were conducted under the protocols approved by the Animal Care and Ethical Committee of Shahed University.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Noroozi N, Mousavi Gargari SL, Nazarian S, Sarvary S, Adriani RR (2018) Immunogenicity of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli outer membrane vesicles encapsulated in chitosan nanoparticles. Iran J Basic Med Sci 21(3):284. 10.22038/ijbms.2018.25886.6371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roy K, Hilliard GM, Hamilton DJ, Luo J, Ostmann MM, Fleckenstein JM (2009) Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli EtpA mediates adhesion between flagella and host cells. Nature 457(7229), 594–598.10.1038/nature07568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Clements A, Young JC, Constantinou N, Frankel G (2012) Infection strategies of enteric pathogenic Escherichia coli. Gut Microbes 3(2):71–78. 10.4161/gmic.19182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holmgren J, Bourgeois L, Carlin N, Clements J, Gustafsson B, Lundgren A, Nygren E, Tobias J, Walker R, Svennerholm AM (2013) Development and preclinical evaluation of safety and immunogenicity of an oral ETEC vaccine containing inactivated E. coli bacteria overexpressing colonization factors CFA/I, CS3, CS5 and CS6 combined with a hybrid LT/CT B subunit antigen, administered alone and together with dmLT adjuvant. Vaccine 31(20):2457–2464. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.03.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cassels FJ, Khalil I, Bourgeois AL, Walker RI (2024) Special Issue on Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) Vaccines: ETEC Infection and Vaccine-Mediated Immunity. Microorganisms 12(6):1087. 10.3390/microorganisms12061087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fleckenstein JM (2021) Confronting challenges to enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli vaccine development. Front Trop Dis 2:709907. 10.3389/fitd.2021.709907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chalghoumi R, Beckers Y, Portetelle D, Théwis A (2009) Hen egg yolk antibodies (IgY), production and use for passive immunization against bacterial enteric infections in chicken: a review. Biotechnologie, Agronomie, Société et Environnement 13(3).

- 8.Kovacs-Nolan J, Mine Y (2012) Egg yolk antibodies for passive immunity. Annual Rev food Sci Technol 3:163–182. 10.1146/annurev-food-022811-101137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vega CG, Bok M, Vlasova AN, Chattha KS, Fernández FM, Wigdorovitz A, Parreno VG, Saif LJ (2012) IgY antibodies protect against human Rotavirus induced diarrhea in the neonatal gnotobiotic piglet disease model. 10.1371/journal.pone.0042788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Pereira E, Van Tilburg M, Florean E, Guedes M (2019) Egg yolk antibodies (IgY) and their applications in human and veterinary health: A review. Int Immunopharmacol 73:293–303. 10.1016/j.intimp.2019.05.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hatta H, Tsuda K, Ozeki M, Kim M, Yamamoto T, Otake S, Hirasawa M, Katz J, Childers N, Michalek S (1997) Passive immunization against dental plaque formation in humans: effect of a mouth rinse containing egg yolk antibodies (IgY) specific to Streptococcus mutans. Caries Res 31(4):268–274. 10.1159/000262410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anosova N, Chabot S, Shreedhar V, Borawski J, Dickinson B, Neutra M (2008) Cholera toxin, E. coli heat-labile toxin, and non-toxic derivatives induce dendritic cell migration into the follicle-associated epithelium of Peyer’s patches. Mucosal Immunol 1(1):59–67. 10.1038/mi.2007.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fingerut E, Gutter B, Meir R, Eliahoo D, Pitcovski J (2005) Vaccine and adjuvant activity of recombinant subunit B of E. coli enterotoxin produced in yeast. Vaccine 23(38):4685–4696. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.03.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim TG, Kim BG, Kim MY, Choi JK, Jung ES, Yang MS (2010) Expression and immunogenicity of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli heat-labile toxin B subunit in transgenic rice callus. Mol Biotechnol 44:14–21. 10.1007/s12033-009-9200-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yokoyama H, Peralta RC, Diaz R, Sendo S, Ikemori Y, Kodama Y (1992) Passive protective effect of chicken egg yolk immunoglobulins against experimental enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli infection in neonatal piglets. Infect Immun 60(3):998–1007. 10.1128/iai.60.3.998-1007.1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akita E, Nakai S (1992) Immunoglobulins from egg yolk: isolation and purification. J Food Sci 57(3):629–634. 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1992.tb08058.x [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsuji T, Joya JE, Honda T, Miwatani T (1990) A heat-labile enterotoxin (LT) purified from chicken enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli is identical to porcine LT. FEMS Microbiol Lett 67(3):329–332. 10.1016/0378-1097(90)90018-L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu Y, Li X, Jin L, Zhen Y, Lu Y, Li S, You J, Wang L (2011) Application of chicken egg yolk immunoglobulins in the control of terrestrial and aquatic animal diseases: a review. Biotechnol Adv 29(6):868. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adriani R, Mousavi Gargari SL, Nazarian S, Sarvary S, Noroozi N (2018) Immunogenicity of Vibrio cholerae outer membrane vesicles secreted at various environmental conditions. Vaccine 36(2):322–330. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sayeed S, Uzal FA, Fisher DJ, Saputo J, Vidal JE, Chen Y, Gupta P, Rood JI, McClane BA (2008) Beta toxin is essential for the intestinal virulence of Clostridium perfringens type C disease isolate CN3685 in a rabbit ileal loop model. Mol Microbiol 67(1):15–30. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06007.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaper JB, Nataro JP, Mobley HL (2004) Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat Rev Microbiol 2(2):123–140. 10.1038/nrmicro818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aizenshtein E, Yosipovich R, Kvint M, Shadmon R, Krispel S, Shuster E, Eliyahu D, Finger A, Banet-Noach C, Shahar E, Pitcovski J (2016) Practical aspects in the use of passive immunization as an alternative to attenuated viral vaccines. Vaccine 34(22):2513–2518. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.03.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karthikeyan M, Indhuprakash ST, Gopal G, Ambi SV, Krishnan UM, Diraviyam T (2022) Passive immunotherapy using chicken egg yolk antibody (IgY) against diarrheagenic E. coli: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Immunopharmacol 102:108381. 10.1016/j.intimp.2021.108381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caradonna TM, Windsor IW, Roffler AA, Song S, Watanabe A, Kelsoe G, Kuraoka M, Schmidt AG (2022) An epitope-enriched immunogen increases site targeting in germinal centers. bioRxiv 2001518697. 10.1101/2022.12.01.518697

- 25.Yang L, Caradonna TM, Schmidt AG, Chakraborty AK (2023) Mechanisms that promote the evolution of cross-reactive antibodies upon vaccination with designed influenza immunogens. Cell reports 42(3).10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Mohammadkhani F, Mousavi Gargari SL, Nazarian S, Mafi M (2023) Protective effects of anti-CfaB-EtpA-LTB IgY antibody against adherence and toxicity of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC). J Appl Microbiol 134(2):lxad013. 10.1093/jambio/lxad013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fathi J, Ebrahimi F, Nazarian S, Hajizade A, Malekzadegan Y, Abdi A (2020) Production of egg yolk antibody (IgY) against shiga-like toxin (stx) and evaluation of its prophylaxis potency in mice. Microb Pathog 145:104199. 10.1016/j.micpath.2020.104199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mudrak B, Kuehn MJ (2010) Heat-labile enterotoxin: Beyond GM1 binding. Toxins 2(6):1445–1470. 10.3390/toxins2061445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reddy BS, Bhat PR (2016) Colonization factor antigen I, an enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli colonization factor, exhibits therapeutic significance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, India Section B: Biological Sciences 86, 995–1000. 10.1007/s40011-015-0549-2

- 30.Wang Z, Li J, Li J, Li Y, Wang L, Wang Q, Fang L, Ding X, Huang P, Yin J (2019) Protective effect of chicken egg yolk immunoglobulins (IgY) against enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli K88 adhesion in weaned piglets. BMC Vet Res 15:1–12. 10.1186/s12917-019-1958-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.