ABSTRACT

Background

5‐methylcytosine (m5C) methylation is the crucial posttranscriptional modification of RNA. NSUN4, a methyltransferase for m5C methylation, contributes to lung tumorigenesis. Here, we determined the precise action of NSUN4 on the development of non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Methods

NSUN4 and CDC20 mRNA expression was detected by quantitative PCR. Western blot and immunohistochemistry were used for the analysis of protein expression. Cell growth, apoptosis, invasiveness, migratory ability, and stemness potential were evaluated by colony formation, flow cytometry, transwell, and sphere formation assays. The influence of NSUN4 in CDC20 mRNA was analyzed using RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) assay and Actinomycin D (Act D) treatment. Subcutaneous xenograft studies were performed to analyze the function in vivo.

Results

In human NSCLC tumors and cell lines, NSUN4 and CDC20 levels were upregulated. NSUN4 inhibition diminished NSCLC cell growth, stemness, invasiveness, and migratory ability in vitro, while NSUN4 increase had opposite effects. A positive expression association between CDC20 and NSUN4 was observed in NSCLC samples. Mechanistically, NSUN4 enhanced the stability of CDC20 mRNA through m5C modification. CDC20 depletion significantly counteracted NSUN4‐driven cell phenotype alterations in vitro. Additionally, inhibition of NSUN4 impeded the growth of A549 NSCLC subcutaneous xenografts in vivo.

Conclusion

Our findings identify the pro‐tumorigenic property of the NSUN4/CDC20 cascade in NSCLC. Targeting the novel cascade may be a promising way for combating this deadly disease.

Keywords: CDC20, m5C methylation, methyltransferase, NSCLC, NSUN4

In non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells, the methyltransferase NSUN4 is upregulated and thus leads to increased CDC20 expression through an m5C modification mechanism, thereby contributing to enhanced proliferation, stemness, migration, and invasion.

1. Introduction

Accounting for approximately 85% of all lung cancer cases, non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is a heterogeneous group of malignancies, which encompasses squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, and large cell carcinoma [1]. It poses a significant threat globally due to its high prevalence and associated morbidity and mortality rates. The prognosis for NSCLC remains dismal, with a 5‐year survival rate often falling below 20%, largely owing to late‐stage diagnosis and aggressive tumor characteristics. The etiology of NSCLC is multifactorial, including smoking, lifestyle, environmental, and genetic factors, which complicate early diagnosis and prolong the initiation of effective treatment [2, 3]. Current therapeutic strategies for NSCLC include surgery, immunotherapy, chemoradiotherapy, and targeted therapies; however, despite these advancements, the overall prognosis remains challenging [4, 5]. The development of NSCLC involves various molecular pathways, and the complexity of these regulatory mechanisms underscores the need for a deeper understanding of NSCLC pathogenesis [6, 7, 8]. This understanding will not only aid in the identification of potential therapeutic targets but also facilitate the development of more effective and personalized treatment strategies.

5‐methylcytosine (m5C) methylation, the posttranscriptional modification of RNA, is vital for gene expression, protein synthesis, and cellular processes, thereby participating in human diseases [9, 10]. NSUN4, a member of the NSUN family of RNA cytosine‐C(5)‐methyltransferases, is responsible for catalyzing the methylation of cytosine residues in RNA [11]. In recent years, NSUN4 has garnered significant attention due to its potential role in modulating cellular functions and tumorigenesis. As an example, NSUN4 has an association with the overall outcomes of clear cell renal cell carcinoma patients [12]. Aberrant expression of NSUN4 is linked to hepatocellular carcinoma development and patient prognosis [13, 14]. Specifically, studies have begun to unravel the complex interplay between NSUN4 and oncogenic pathways. For instance, NSUN4‐mediated changes in RNA m5C modification affect the ALYREF/CDC20 interaction to activate the oncogenic PI3K/AKT pathway in glioma [15]. In the context of lung cancer, NSUN4 expression is enhanced in primary tumors and related to patient survival [16]. Dysregulation of NSUN4 is also associated with the infiltration of neutrophils and tumor immune microenvironment in lung carcinoma [16]. Furthermore, NSUN4‐induced circERI2 m5C methylation contributes to lung tumorigenesis by controlling energy metabolism by targeting and stabilizing DDB1 [17]. Despite the emerging insights into NSUN4's contributions to lung tumorigenesis, the underlying mechanisms in this context are still largely unknown.

In this report, we further determined the precise action of NSUN4 on NSCLC development using cultured NSCLC cells in vitro and generated NSCLC subcutaneous xenografts in vivo. Further, we attempted to uncover a novel determinant underlying the action of NSUN4 depending on its m5C regulation mechanism.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bioinformatics

The expression profiling of NSUN4 in human NSCLC was retrieved from the online databases TIMER (https://cistrome.shinyapps.io/timer/) and UALCAN (https://ualcan.path.uab.edu/analysis.html). We utilized the linkedomics website (https://www.linkedomics.org/login.php) to observe the NSUN4‐associating genes that were dysregulated in NSCLC following NSUN4 upregulation. The linkedomics website was also used for the analysis of the expression correlation of CDC20 with NSUN4 in NSCLC. The upregulation of the CDC20 transcript in NSCLC was also revealed by the UALCAN online tool.

2.2. Human Clinical Specimens

During surgical procedures, we acquired pulmonary tissue samples from 53 sufferers diagnosed with NSCLC. These clinical specimens, encompassing both primary NSCLC tumors and their neighboring noncancerous lung samples, originated from the same individuals at Shanxi Province Cancer Hospital, Shanxi Hospital Affiliated to Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Cancer Hospital Affiliated to Shanxi Medical University. Once collected, we placed these human specimens in liquid nitrogen for storage. Patient consent was obtained before specimen collection. The research involving human subjects received approval from the Research Ethics Committee of Shanxi Province Cancer Hospital, Shanxi Hospital Affiliated to Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Cancer Hospital Affiliated to Shanxi Medical University.

2.3. Cell Lines and Culture Method

A549 (human lung adenocarcinoma [LUAD] cell line, #IM‐H113, Immocell, Xiamen, China), SK‐MES‐1 (human lung squamous cell carcinoma [LUSC] cell line, #CL‐0213, Procell, Wuhan, China), H460 (human large cell lung cancer cell line, #IM‐H228, Immocell), H1299 (#IM‐H242, Immocell), H2170 (human LUSC cell line, #CL‐0394, Procell), and BEAS‐2B (nontumor bronchial epithelial cell line, #IM‐H128, Immocell) cells were used in the present work. For cell cultivation, we procured DMEM (for A549 and BEAS‐2B), RPMI‐1640 (for H460, H1299, and H2170), and MEM (for SK‐MES‐1) from Cell Application (San Diego, CA, USA), both of which were enriched with 1% Streptomycin/Penicillin (Invitrogen, Wesel, Germany) and 10% FBS (Nichirei Bioscience, Tokyo, Japan). We routinely maintained these cell lines in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere incubator (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Uppsala, Sweden) at 37°C.

2.4. Constructs and Transfection and Transduction of Cell Lines

For in vitro depletion or overexpression studies, we obtained pLV3‐U6‐NSUN4 (human)‐shRNA1‐CopGFP‐Puro (sh‐NSUN4#1), pLV3‐U6‐NSUN4 (human)‐shRNA2‐CopGFP‐Puro (sh‐NSUN4#2), pLV3‐U6‐CDC20 (human)‐shRNA‐CopGFP‐Puro (sh‐CDC20), the corresponding shRNA control (sh‐ctrl), pLV3‐CMV‐NSUN4 (human)‐EF1a‐CopGFP‐Puro (NSUN4 expression construct), pLV3‐CMV‐ALYREF (human)‐3 × FLAG‐CopGFP‐Puro (OE‐ALYREF), and matched nontarget control plasmid (vector) from Miaoling Biology (Wuhan, China). Under the application of Lipofectamine 3000, in accordance with the producer's protocols (Thermo Fisher Scientific), we introduced shRNA, plasmid, or plasmid+shRNA into SK‐MES‐1 and A549 NSCLC cells. After changing the medium, cells were incubated for 24–72 h.

Based on the sh‐NSUN4#2 or sh‐ctrl construct, sh‐NSUN4#2 lentivirus particles and sh‐ctrl virus controls were generated by Genomeditech (Shanghai, China). To produce in vivo xenograft models, each virus strain was used to transduce A549 cells in media encompassing polybrene (5 μg/mL, Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Following a 24‐h period, the cells underwent puromycin selection at a concentration of 2 μg/mL (Beyotime) for 2 weeks.

2.5. Analysis of NSUN4 and CDC20 mRNA Expression

Using the RNA purification kit and accompanying suggestions (Norgen Biotek Corporation, Thorold, ON, Canada), we prepared RNA from collected human specimens (~20 mg) or cultivated SK‐MES‐1 and A549 cells. For reverse transcription (RT), 200 ng of RNA was diluted and used. The RT reactions for NSUN4 and CDC20 were conducted with GoScript RT System (Promega, Charbonnières, France), followed by quantitative PCR using Thunderbird SYBR qPCR Mix as described by the supplier (Toyobo, Tokyo, Japan) with synthetic primer sets specific for NSUN4 (5′‐CGCAATCTTGCTGCCAATGA‐3′‐forward and 5′‐TCCTGCCATCCCATGAGGTA‐3′‐reverse) or CDC20 (5′‐ATTCACCCAGCATCAAGGGG‐3′‐forward and 5′‐AGCACACATTCCAGATGCGA‐3′‐reverse). Gene expression was normalized to β‐actin (5′‐CTTCGCGGGCGACGAT‐3′‐forward and 5′‐CCACATAGGAATCCTTCTGACC‐3′‐reverse), and fold‐change (2−ΔΔCt method) in NSUN4 and CDC20 expression between conditions was determined.

2.6. Subcutaneous Xenograft Studies and Immunohistochemistry

In accordance with the guidelines approved by Shanxi Province Cancer Hospital, Shanxi Hospital Affiliated to Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Cancer Hospital Affiliated to Shanxi Medical University Animal Care and Use Committee, we utilized BALB/c nude mice (age: 5–6 weeks, gender: female, n = 12), which were purchased from Vital River Laboratory (Beijing, China), for our animal studies. For the xenograft modeling, we subcutaneously injected 5 × 106 A549 cells, which had been transduced with either sh‐ctrl or sh‐NSUN4#2 lentivirus particles, into the left flank of nude mice. Tumor growth monitoring began 1‐week postinjection by the measurement of tumor volume (longest diameter × [shortest diameter]2 × 1/2) weekly using a caliper. Following a period of 5 weeks, after the mice were euthanized, we collected the xenografts for subsequent weight assessment and expression detection. Sections (4–5 μm) of paraffin‐embedded subcutaneous xenograft were subjected to immunohistochemistry under a standard method reported by Lee et al. [18], using rabbit anti‐CD133 monoclonal (#ab222782, 1–1000, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), rabbit anti‐NSUN4 polyclonal (#PA5‐140975, 1–150, Invitrogen), rabbit anti‐CDC20 polyclonal (#10252‐1‐AP, 1–300, Proteintech, Wuhan, China), rabbit anti‐SOX2 polyclonal (#PA1‐094, 1–300, Invitrogen), or rabbit anti‐KLF4 polyclonal (#11880‐1‐AP, 1–300, Proteintech).

2.7. Western Blot

We harvested protein extracts from collected tissue specimens (~50 mg) or cultivated cells (1 × 107) and conducted immunoblot analysis as described previously [18] with rabbit anti‐NSUN4 polyclonal (#29786‐1‐AP, 1–4000, Proteintech), rabbit anti‐CDC20 polyclonal (#10252‐1‐AP, 1–8000, Proteintech), rabbit anti‐SOX2 polyclonal (#11064‐1‐AP, 1–600, Proteintech), rabbit anti‐CD133 monoclonal (#ab222782, 1–2000, Abcam), rabbit anti‐KLF4 polyclonal (#11880‐1‐AP, 1–6000, Proteintech), or mouse anti‐β‐actin monoclonal (#66009‐1‐Ig, 1–50 000, Proteintech). The EZ‐ECL Kit was used for signal visualization as recommended by the vendor (Biological Industries, Beit‐Haemek, Israel). For intensity analysis, we applied the ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

2.8. Cell Colony Formation

In six‐well culture plates, we seeded SK‐MES‐1 and A549 cells at the density of ~300 cells per well, 24 h following the suitable transfection. After seeding, the colonies were allowed to proliferate for 10–14 days. After crystal violet (0.5%) staining, we utilized the ImageJ software to quantify the number of colonies formed, with each colony consisting of more than 50 cells.

2.9. Assessment of Cell Apoptosis by Flow Cytometry

We performed FACS analysis on the Calibur flow cytometer with CellQuest software (BD Biosciences, Cowley, UK). At 72‐h posttransfection, we stained SK‐MES‐1 and A549 cells with FITC‐labeled Annexin V and propidium iodide using the commercially available Assay Kit and manufactory recommendations (Vazyme Biotech, Nanjing, China). Within 1 h, stained cells were tested for the evaluation of apoptotic cells.

2.10. Evaluation of Cell Invasiveness and Migratory Ability by Transwell Assay

For conducting invasiveness assays, we utilized Matrigel invasion chambers from BD Biosciences. For the assessment of cell migratory ability, we employed 24‐Transwell migration chambers with 8 μm pore inserts (BD Biosciences). After being re‐suspended in nonserum media, SK‐MES‐1 and A549 cells at 24 h following the suitable transfection were plated in each upper chamber (1 × 105 for invasiveness and 4 × 104 for migration). Subsequently, the lower chamber was added with the medium containing 10% FBS. Following a 24‐h incubation period, the invading or migratory cells were evaluated by ImageJ across five randomly chosen fields after staining with 0.5% crystal violet.

2.11. Cell Sphere Formation Assay

We employed the 96‐well Clear Round Bottom Ultra Low Attachment plate (Corning, Shanghai, China) to evaluate the sphere formation potential of SK‐MES‐1 and A549 cells, 24 h following the indicated transfection. Transfected SK‐MES‐1 and A549 cells, which had been serum‐deprived, were seeded into individual wells. After the incubation for 1 week at 37°C, we scored the diameter of formed spheres by ImageJ through microscopic examination.

2.12. RNA Immunoprecipitation (RIP) Assay

RIP assays were performed with the BeyoRIP RIP Assay Kit from Beyotime and rabbit anti‐NSUN4 polyclonal (#A14983, ABclonal, Wuhan, China), mouse anti‐m5C monoclonal (#C15200081, Diagenode, Liège, Belgium), rabbit anti‐ALYREF polyclonal (#16690‐1‐AP, Proteintech), or rabbit anti‐IgG polyclonal (#30000‐0‐AP, Proteintech). We prepared total extractions of SK‐MES‐1 and A549 cells transfected with or without sh‐ctrl, sh‐NSUN4#2, vector, or NSUN4 expression construct. Meantime, the complex of the indicated antibody and Protein A/G Agarose was generated. The mixture of cell extractions and antibody–bead complex was prepared and incubated for 4–6 h at 4°C. After that, the precipitates were subjected to RNA extraction for the determination of the CDC20 mRNA enrichment level using quantitative PCR.

2.13. Actinomycin D (Act D) Treatment for CDC20 mRNA Stability Detection

SK‐MES‐1 and A549 cells, after transfection with sh‐ctrl, sh‐NSUN4#2, vector, or NSUN4 expression construct, were subjected to the treatment of Act D (50 μg/mL, Beyotime). Following exposure durations of 0, 2, 4, and 8 h, the abundance of the remaining CDC20 mRNA was quantified by quantitative PCR.

2.14. Statistics

We expressed all data as mean ± SD. For statistical significance, we used a Mann–Whitney U‐test, Student's t‐test (two‐tailed, unpaired), or ANOVA (either one‐way or two‐way), with P values < 0.05 considered significant. For the analysis of expression association, we utilized Pearson's correlation coefficients.

3. Results

3.1. High Expression of NSUN4 Is Observed in Human NSCLC, and Its Inhibition Diminishes Cell Growth, Stemness, Invasiveness, and Migratory Ability In Vitro

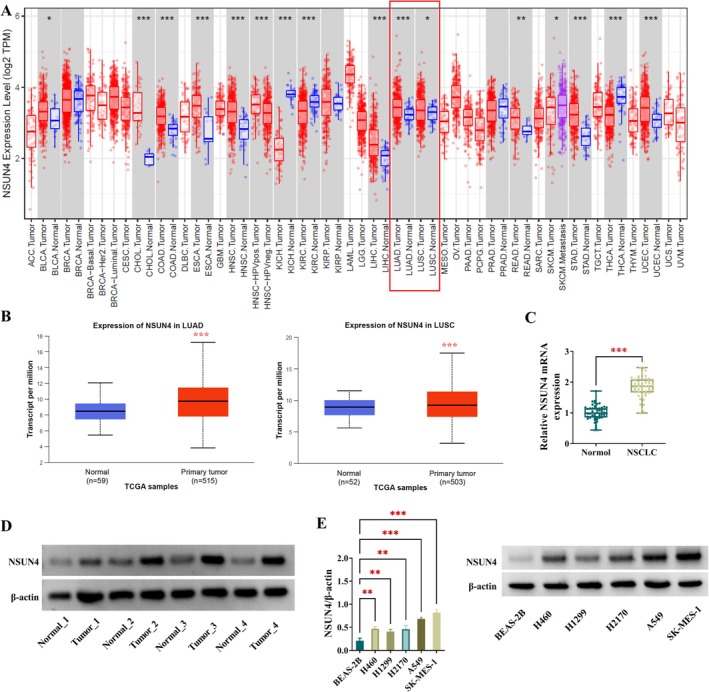

The analysis of NSUN4 expression profiling using the online databases TIMER suggested that compared with normal controls, NSUN4 transcript was highly expressed not only in LUAD but also in LUSC (Figure 1A). In parallel, NSUN4 mRNA levels in 111 normal samples, 515 LUAD, and 503 LUSC were retrieved from TCGA on the online UALCAN project, revealing the enhanced expression of NSUN4 mRNA in NSCLC (Figure 1B). Additionally, using the UALCAN web, we observed that NSUN4 expression did not significantly (p = 0.16) associate with the prognosis of patients with LUAD, yet it was significantly (p = 0.028) correlated with the overall survival of LUSC patients (Figure S1). The RNA levels were subsequently measured in 53 pairs of primary NSCLC tumors and their neighboring noncancerous lung tissues. As demonstrated by quantitative PCR, NSUN4 mRNA levels were significantly upregulated in NSCLC tumors compared with the corresponding controls (Figure 1C). Protein extractions were also prepared from four pairs of NSCLC tumors and matched noncancerous lung samples, followed by immunoblot analysis. From this analysis, we observed the strongly increased expression of NSUN4 protein in human NSCLC tumors (Figure 1D). The NSUN4 protein expression was also examined in NSCLC cell lines A549 and SK‐MES‐1 and compared to that in nontumor BEAS‐2B cells. Using immunoblot analysis, we found that NSCLC cells exhibited increased expression of NSUN4 protein compared with BEAS‐2B cells (Figure 1E). Moreover, A549 and SK‐MES‐1 cells displayed higher levels of NSUN4 (Figure 1E). Thus, we used A549 and SK‐MES‐1 NSCLC cells in this study.

FIGURE 1.

High expression of NSUN4 in human NSCLC. (A and B) TIMER and UALCAN‐TCGA databases suggested that NSUN4 transcript was highly expressed in lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) and lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC). (C) NSUN4 mRNA levels by quantitative PCR in primary NSCLC tumors (n = 53) and their neighboring noncancerous lung tissues (n = 53). (D) NSUN4 protein expression by immunoblotting in primary NSCLC tumors (n = 4) and their neighboring noncancerous lung tissues (n = 4). (E) NSUN4 protein expression in A549, H460, H1299, H2170, and SK‐MES‐1 NSCLC cells and nontumor BEAS‐2B cells (n = 3). **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Next, we prepared NSUN4‐silenced A549 and SK‐MES‐1 NSCLC cells using two different shRNAs targeting NSUN4 (sh‐NSUN4#1 or sh‐NSUN4#2) to evaluate the precise activity of NSUN4 in NSCLC development. The significant depletion of NSUN4 was achieved in the two NSCLC cell lines by sh‐NSUN4#1 or sh‐NSUN4#2, which was verified by immunoblotting (Figure 2A). The deficiency of NSUN4 reduced the number of generated colonies (Figure 2B) and had promoting impact on cell apoptosis (Figure 2C). Moreover, NSUN4‐depleted A549 and SK‐MES‐1 cells exhibited retarded migratory and invasive potential (Figure 2D,E). Of note, the depletion of NSUN4 had suppressive effects on NSCLC cell stemness, which was evidenced by the reduced diameter of formed spheres (Figure 2F). Immunoblot analysis also showed the expression downregulation of stemness‐related proteins SOX2, CD133, and KLF4 in NSUN4‐depleted A549 and SK‐MES‐1 cells (Figure 2G,H), supporting the suppression of NSUN4 depletion on stemness. Thus, we conclude that upregulated NSUN4 plays a critical role in accelerating cell malignant phenotypes in NSCLC.

FIGURE 2.

NSUN4 inhibition affects cell growth, apoptosis, stemness, invasiveness, and migratory ability in vitro. (A–H) Various experiments were conducted using different treatment methods and cell types (A549 and SK‐MES‐1 NSCLC cells), with three groups: Sh‐ctrl, sh‐NSUN4#1, or sh‐NSUN4#2. (A) Evaluation of NSUN4 protein expression by immunoblotting in cells transfected as indicated. (B) Assessment of the number of formed colonies with cells transfected as indicated. (C) Determination of cell apoptotic ratio with cells transfected as indicated by flow cytometry. (D and E) Examination of cell migratory rate and invasiveness with transfected cells. Scale bars: 100 μm. (F) Measurement of sphere formation with transfected NSCLC cells. Scale bars: 100 μm. (G and H) Expression of SOX2, CD133, and KLF4 proteins using immunoblot analysis in transfected A549 and SK‐MES‐1 NSCLC cells. n = 3 in (A–G). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

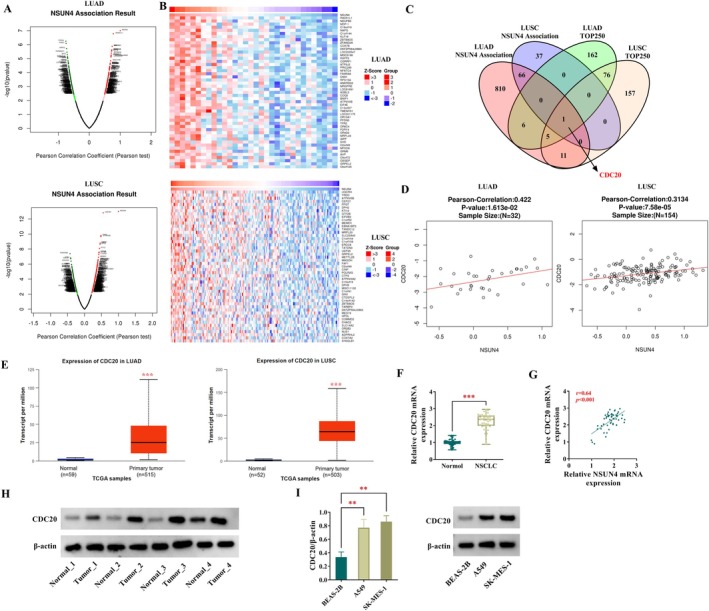

3.2. Positive Expression Association Between CDC20 and NSUN4 in NSCLC

Since the depletion of NSUN4 affects NSCLC cell behaviors, we hypothesized that these effects are mediated by its regulatory targets that were dysregulated in NSCLC following NSUN4 upregulation. As shown in Figure 3A, volcano plot revealed the profiling of NSUN4‐associating genes in LUAD and LUSC from the online data of the linkedomics website. Based on these data, the heat map presented the positively correlated genes with NSUN4 in LUAD and LUSC (Figure 3B). By combining these positively correlated genes (with Pearson's correlation coefficient > 0.3) with the top 250 significantly upregulated genes in LUAD and LUSC on the UALCAN website, only CDC20 was found (Figure 3C). Studies have highlighted the oncogenic property of CDC20 in various human malignancies [19]. Of interest, the linkedomics database revealed the positive expression correlation of CDC20 with NSUN4 in LUAD and LUSC (Figure 3D). Using the UALCAN online tool, we observed the upregulation of CDC20 transcript in LUAD and LUSC tumors compared with their nontumor counterparts (Figure 3E). High expression of CDC20 mRNA was also confirmed in clinical NSCLC tumors compared with the matched nontumor samples (Figure 3F). Furthermore, in clinical NSCLC tumors, CDC20 mRNA expression was positively associated with NSUN4 transcript levels (Figure 3G). In addition, through western blot analysis, we verified that CDC20 protein levels were increased in clinical NSCLC tumors and cancer cell lines (A549 and SK‐MES‐1) (Figure 3H,I).

FIGURE 3.

CDC20 expression is positively associated with NSUN4 in NSCLC. (A) Volcano plot revealed the profiling of NSUN4‐associating genes in LUAD and LUSC (the linkedomics website). (B) Heat map presented the positively correlated genes with NSUN4 in LUAD and LUSC (the linkedomics website). (C) Venn diagram showing CDC20 that was positively correlated with NSUN4 in NSCLC (the linkedomics website) and one of the top 250 significantly upregulated genes in LUAD and LUSC (UALCAN website). (D) The linkedomics database revealed the positive expression correlation of CDC20 with NSUN4 in LUAD and LUSC. (E) The UALCAN online tool showed the high expression of CDC20 transcript in LUAD and LUSC. (F) CDC20 mRNA expression by quantitative PCR in primary NSCLC tumors (n = 53) and their neighboring noncancerous lung tissues (n = 53). (G) Expression correlation analysis of CDC20 with NSUN4 in clinical NSCLC tumors (n = 53). (H) CDC20 protein levels in primary NSCLC tumors (n = 4) and their neighboring noncancerous lung tissues (n = 4). (I) CDC20 protein expression in A549 and SK‐MES‐1 NSCLC cells and nontumor BEAS‐2B cells (n = 3). **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

3.3. NSUN4 Enhances the Stability of CDC20 mRNA Through ALYREF‐Dependent m5C Modification

As an m5C regulator, NSUN4 has been reported to contribute to RNA m5C methylation and thus participates in tumor biology [15, 17]. Having established the positive expression association of CDC20 with NSUN4, we set to examine whether NSUN4 can influence CDC20 mRNA m5C modification. First, we evaluated the impact of NSUN4 on CDC20 expression in A549 and SK‐MES‐1 cells. In contrast, sh‐NSUN4#2‐mediated NSUN4 knockdown resulted in decreased CDC20 expression at both mRNA and protein, while the introduction of the NSUN4 expression constructs elevated the mRNA and protein levels of CDC20 in the two NSCLC cell lines (Figure 4A–D), supporting their positive expression association. We then examined the binding relationship between NSUN4 and CDC20 mRNA using RIP experiments. Employing the specific anti‐NSUN4 antibody, we confirmed their interaction in NSCLC cells because CDC20 mRNA was strongly enriched in NSUN4‐associating precipitates compared with isotype IgG complexes (Figure 4E). Thirdly, we analyzed the influence of NSUN4 on the m5C methylation of CDC20 mRNA. Using an anti‐m5C antibody in RIP assays, the m5C modification of CDC20 mRNA was observed in A549 and SK‐MES‐1 cells, and the depletion of NSUN4 significantly repressed this transcript m5C methylation compared with the sh‐ctrl control (Figure 4F). On the other hand, increased NSUN4 expression by the NSUN4 expression construct remarkably promoted CDC20 mRNA m5C methylation (Figure 4G). Finally, we monitored the effect of NSUN4 on CDC20 mRNA stabilization by Act D treatment. In the presence of Act D to prevent transcription, NSUN4 depletion significantly shortened the half‐life of CDC20 mRNA, while increased NSUN4 expression enhanced its half‐life in A549 and SK‐MES‐1 NSCLC cells (Figure 4H–K). ALYREF, a key m5C reader, recognizes and binds to the mRNA m5C sites to stabilize mRNA and thus has been implicated in NSCLC progression [20]. Using RIP experiments with an antibody to ALYREF, we found that NSUN4 depletion led to a strong reduction in the enrichment levels of CDC20 mRNA in the ALYREF‐associating precipitates (Figure 4L,M), suggesting that NSUN4 mediates the m5C modification of CDC20 mRNA in an ALYREF‐dependent manner. In support of this notion, we showed that ALYREF increase could attenuate NSUN4 depletion‐caused CDC20 reduction in A549 and SK‐MES‐1 cells (Figure 4N,O). Taken together, these results suggest that NSUN4 can mediate the m5C modification of CDC20 mRNA in an ALYREF‐dependent manner to promote the stability and expression of this transcript.

FIGURE 4.

NSUN4 mediates m5C modification of CDC20 mRNA to stabilize this transcript. (A–D) CDC20 mRNA levels by quantitative PCR (A and B) and its protein expression by western blot (C and D) in A549 and SK‐MES‐1 NSCLC cells transfected with sh‐ctrl, sh‐NSUN4#2, vector, or NSUN4 expression construct. (E) RIP experiments with lysates of A549 and SK‐MES‐1 NSCLC cells using anti‐IgG or anti‐NSUN4 antibody, followed by assessment of CDC2 mRNA enrichment abundance by quantitative PCR. (F and G) m5C RIP experiments with total extractions of sh‐ctrl‐ or sh‐NSUN4#2‐transfected A549 and SK‐MES‐1 cells using anti‐m5C antibody, followed by quantitative PCR for evaluation of CDC2 mRNA enrichment levels. (H–K) A549 and SK‐MES‐1 cells transfected with sh‐ctrl, sh‐NSUN4#2, vector, or NSUN4 expression construct were exposed to Act D for the indicated time points and checked for the remaining level of CDC20 mRNA. (L and M) RIP experiments with lysates of sh‐ctrl‐ or sh‐NSUN4#2‐transfected cells using an antibody against ALYREF or IgG, followed by assessment of CDC2 mRNA enrichment abundance. (N and O) CDC20 mRNA and protein expression in cells transfected as indicated. n = 3 in (A–O). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

3.4. CDC20 Depletion Counteracts NSUN4‐Driven Cell Phenotype Alterations In Vitro

Previous studies have highlighted the oncogenic activity of CDC20 in NSCLC by affecting cancer cell growth and apoptosis [21, 22]. Based on our findings and previous reports, we hypothesized that NSUN4 regulates NSCLC cell phenotypes via CDC20. To test this hypothesis, we generated NSUN4‐increased or CDC20‐depleted cells and reduced CDC20 expression in NSUN4‐increased A549 and SK‐MES‐1 NSCLC cells. The depletion of CDC20 was achieved by sh‐CDC20 introduction (Figure 5A). Increased expression of NSUN4 by the expression construct led to a significant augmentation in CDC20 protein expression, which was partially abrogated by sh‐CDC20 (Figure 5A). Functional analyses revealed that NSUN4 increased accelerated cell colony formation (Figure 5B), impeded cell apoptosis (Figure 5C), enhanced migratory and invasive abilities (Figure 5D,E), promoted cell stemness (Figure 5F), as well as upregulated SOX2, CD133, and KLF4 levels (Figure 5G,H) in A549 and SK‐MES‐1 cells. Conversely, the deficiency of CDC20 led to a strong inhibition in cell colony formation (Figure 5B), a striking promotion in cell apoptosis (Figure 5C), and a distinct repression in cell motility, invasiveness, and stemness (Figure 5D–H). Furthermore, the NSUN4 + sh‐CDC20‐transfected cells and control cells were of comparable cell colony formation (Figure 5B), apoptosis (Figure 5C), cell motility, invasiveness, and stemness (Figure 5D–H). These results demonstrate our hypothesis that the observed effects of NSUN4 are due to its regulation in CDC20.

FIGURE 5.

NSUN4 affects NSCLC cell malignant phenotypes through CDC20. (A–H) A549 and SK‐MES‐1 NSCLC cells were subjected to introduction with vector + sh‐ctrl, NSUN4 expression construct + sh‐ctrl, vector + sh‐CDC20, or NSUN4 + sh‐CDC20. (A) CDC20 protein expression by immunoblotting in cells transfected as indicated. (B) The number of formed colonies by colony formation assay with cells transfected as indicated. (C) Cell apoptotic ratio by flow cytometry with cells transfected as indicated. (D and E) Cell migratory rate and invasiveness by transwell assay with transfected cells. Scale bars: 100 μm. (F) Measurement of sphere formation with transfected NSCLC cells. (G and H) Expression of SOX2, CD133, and KLF4 proteins by immunoblot analysis in transfected A549 and SK‐MES‐1 NSCLC cells. n = 3 in (A–G). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns: non‐significant.

3.5. Inhibition of NSUN4 Impedes the Growth of A549 NSCLC Subcutaneous Xenografts In Vivo

Finally, we elucidated whether NSUN4 influences NSCLC development not only in cultured NSCLC cells but also in NSCLC subcutaneous xenografts. We established A549 NSCLC subcutaneous xenografts in nude mice and determined the impact of NSUN4 depletion on tumor growth. The silencing of NSUN4 significantly hindered the growth of A549 subcutaneous xenografts (Figure 6A–C). Western blot and immunohistochemistry analyses revealed reduced expression of NSUN4, CDC20, SOX2, CD133, and KLF4 proteins in sh‐NSUN4#2 A549 xenografts compared with sh‐ctrl controls (Figure 6D,E). Taken together, these data indicate the inhibitory effect of NSUN4 depletion on the growth of A549 subcutaneous xenografts.

FIGURE 6.

NSUN4 depletion hinders the growth of A549 subcutaneous xenografts. (A–E) A549 subcutaneous xenografts were generated by implanting sh‐ctrl or sh‐NSUN4#2 lentivirus‐infected A549 cells. After 30 days, xenografts were harvested. n = 5 for each group. (A) Growth curves of A549 subcutaneous xenografts (n = 3). (B) Representative pictures of A549 subcutaneous xenografts. (C) Tumor average weight was calculated (n = 3). (D) Expression of NSUN4, CDC20, SOX2, CD133, and KLF4 proteins by immunoblot analysis in A549 subcutaneous xenografts (n = 3). (E) Expression of NSUN4, CDC20, SOX2, CD133, and KLF4 proteins by immunohistochemistry in sections of subcutaneous xenografts. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

4. Discussion

NSCLC represents a significant clinical challenge due to its high incidence and poor prognosis [1]. Identifying the mechanisms that drive NSCLC development is crucial for devising efficient therapies, yet the complexity and heterogeneity of NSCLC biology pose substantial obstacles. Here, we have found that upregulated NSUN4 plays a critical role in accelerating cell malignant phenotypes in NSCLC. Furthermore, we highlight the implication of the NSUN4/CDC20 axis, a novel mechanism that has not been previously reported, in the context of NSCLC. This finding is significant as CDC20 is a known oncogenic factor that plays a pivotal role in cell cycle regulation and is implicated in carcinogenesis [19]. Thus, the NSUN4/CDC20 cascade emerges as a promising target for combating this challenging disease.

As a methyltransferase known for its role in the modification of RNA, specifically through m5C methylation, NSUN4 is emerging as a significant player in tumor biology and is related to the risk of breast cancer, prostate cancer, and anaplastic thyroid cancer [23, 24, 25]. NSUN4 expression also has relevance to the prognosis and diagnosis of papillary thyroid carcinoma [26]. The functional studies have revealed diverse roles of NSUN4 in regulating gene expression and cellular processes, with particular emphasis on its potential oncogenic functions. Research has indicated that NSUN4 has been implicated in the progression of various malignancies, such as hepatocellular carcinoma and glioma [13, 15]. Furthermore, NSUN4 is reported to function as a potential prognostic marker in LUAD and LUSC [16, 27]. NSUN4 is also able to affect immune checkpoint expression, neutrophil infiltration, and tumor immune microenvironment in NSCLC [16, 27]. By mediating m5C methylation of circERI3, NSUN4 has been shown to exert a pro‐tumorigenic function in lung cancer by regulating mitochondrial energy metabolism [17]. Our data illuminate the upregulation of NSUN4 in NSCLC tumors and cell lines, correlating with aggressive tumor characteristics. Through loss‐of‐function studies, we demonstrate the crucial role of NSUN4 in fostering NSCLC cell growth, stemness, invasiveness, and migratory potential and suppressing apoptosis in vitro. Inhibition of NSUN4 also impedes the growth of A549 NSCLC subcutaneous xenografts in vivo. These findings underscore the relevance of NSUN4 as a potential player in NSCLC progression and aggressiveness. Inhibiting NSUN4 may open avenues for innovative treatments in NSCLC management.

CDC20, a cell division cycle protein, plays an essential role in multiple biological processes, particularly in cell cycle regulation and mitotic progression [28]. Its dysregulation has been implicated in various malignancies, where elevated CDC20 expression is often positively associated with enhanced tumor aggressiveness and poor prognosis [19, 29]. For example, CDC20 contributes to glioblastoma development depending on its regulation of cancer cell proliferation [30]. CDC20 is present at high expression in hepatocellular carcinoma, and its knockdown retards cancer cell cycle progression, growth, and invasion by enhancing their radiosensitivity [31]. Inhibiting CDC20 is capable of enhancing the efficacy of anti‐PD1‐based immunotherapy in prostate cancer [32]. In lung cancer, specifically, CDC20 has garnered attention for its contributions to cell proliferation, mitosis, and metastatic potential [21, 22, 33], positioning it as a potential target for therapeutic intervention. Our current study reveals intriguing insights into the regulation of CDC20 by NSUN4 in NSCLC. A positive association between CDC20 and NSUN4 expression is observed in NSCLC tumors. ALYREF functions as a key m5C reader in stabilizing mRNA by binding to the m5C sites and has been implicated in NSCLC progression [20]. Mechanistically, NSUN4 enhances the stability of CDC20 mRNA through ALYREF‐dependent m5C modification, effectively upregulating CDC20 protein levels. This finding is novel and provides a mechanism underlying CDC20 overexpression in NSCLC. Importantly, our data show that depletion of CDC20 counteracts NSUN4‐driven cellular phenotype alterations, suggesting that CDC20 is a downstream effector of NSUN4 in promoting NSCLC malignant phenotypes. Thus, the NSUN4/CDC20 axis may be critical for maintaining the malignant characteristics of NSCLC cells. Despite establishing that NSUN4 mediates m5C modification of CDC20 mRNA, the specific m5C modification sites on CDC20 mRNA remain unclear, which is a big limitation in our study. Exploring the m5C modification sites of CDC20 would be better and more valuable for our understanding of the epigenetic regulation of CDC20 in NSCLC. Related research will be warranted in future studies.

Despite the intriguing observation that NSUN4 influences CDC20 expression in vivo, direct evidence linking the NSUN4/CDC20 cascade in NSCLC remains unclear within an in vivo NSCLC xenograft model and warrants further investigation. Second, our research utilized only two NSCLC cell lines, which may not fully represent the heterogeneity of NSCLC tumors. Future studies should incorporate a broader range of cell lines and primary patient‐derived cancer cells to comprehensively evaluate the role of the NSUN4/CDC20 axis across different NSCLC subtypes. With these results, we envision that the sh‐NSUN4 and sh‐CDC20 are starting points for the development of molecularly targeted therapies against NSCLC. Future research directions should focus on exploring the potential of targeting this cascade in combination therapies, and assessing the efficacy and safety of sh‐NSUN4 or sh‐CDC20 in various animal experimental models.

In conclusion, we report, for the first time, the pro‐tumorigenic property of the NSUN4/CDC20 cascade in NSCLC. Targeting the novel cascade using pharmacological inhibitors or genetic manipulation techniques represents a promising way for combating this deadly disease.

Author Contributions

The author takes full responsibility for this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Association between NSUN4 expression and patient prognosis analyzed using the UALCAN project.

Acknowledgments

The authors have nothing to report.

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Hendriks L. E. L., Remon J., Faivre‐Finn C., et al., “Non‐Small‐Cell Lung Cancer,” Nature Reviews. Disease Primers 10 (2024): 71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Duma N., Santana‐Davila R., and Molina J. R., “Non‐Small Cell Lung Cancer: Epidemiology, Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment,” Mayo Clinic Proceedings 94 (2019): 1623–1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Riely G. J., Wood D. E., Ettinger D. S., et al., “Non‐Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 4.2024, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology,” Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 22 (2024): 249–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Meyer M. L., Fitzgerald B. G., Paz‐Ares L., et al., “New Promises and Challenges in the Treatment of Advanced Non‐Small‐Cell Lung Cancer,” Lancet 404 (2024): 803–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Li S., Wang A., Wu Y., et al., “Targeted Therapy for Non‐Small‐Cell Lung Cancer: New Insights Into Regulated Cell Death Combined With Immunotherapy,” Immunological Reviews 321 (2024): 300–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Imyanitov E. N., Iyevleva A. G., and Levchenko E. V., “Molecular Testing and Targeted Therapy for Non‐Small Cell Lung Cancer: Current Status and Perspectives,” Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 157 (2021): 103194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Saller J. J. and Boyle T. A., “Molecular Pathology of Lung Cancer,” Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine 12 (2022): a037812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kerr K. M., Bibeau F., Thunnissen E., et al., “The Evolving Landscape of Biomarker Testing for Non‐Small Cell Lung Cancer in Europe,” Lung Cancer 154 (2021): 161–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Xiong Y., Li Y., Qian W., and Zhang Q., “RNA m5C Methylation Modification: A Potential Therapeutic Target for SARS‐CoV‐2‐Associated Myocarditis,” Frontiers in Immunology 15 (2024): 1380697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li Y., Jin H., Li Q., Shi L., Mao Y., and Zhao L., “The Role of RNA Methylation in Tumor Immunity and Its Potential in Immunotherapy,” Molecular Cancer 23 (2024): 130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kim S., Tan S., Ku J., et al., “RNA 5‐Methylcytosine Marks Mitochondrial Double‐Stranded RNAs for Degradation and Cytosolic Release,” Molecular Cell 84 (2024): 2935–2948.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wu J., Hou C., Wang Y., Wang Z., Li P., and Wang Z., “Comprehensive Analysis of m(5)C RNA Methylation Regulator Genes in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma,” International Journal of Genomics 2021 (2021): 3803724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sun G. F. and Ding H., “NOP2‐Mediated m5C Methylation of XPD is Associated With Hepatocellular Carcinoma Progression,” Neoplasma 70 (2023): 340–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li X. Y. and Yang X. T., “Correlation Between the RNA Methylation Genes and Immune Infiltration and Prognosis of Patients With Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Pan‐Cancer Analysis,” Journal of Inflammation Research 15 (2022): 3941–3956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhao Z., Zhou Y., Lv P., et al., “NSUN4 Mediated RNA 5‐Methylcytosine Promotes the Malignant Progression of Glioma Through Improving the CDC42 mRNA Stabilization,” Cancer Letters 597 (2024): 217059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pan J., Huang Z., and Xu Y., “m5C RNA Methylation Regulators Predict Prognosis and Regulate the Immune Microenvironment in Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma,” Frontiers in Oncology 11 (2021): 657466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wu J., Zhao Q., Chen S., et al., “NSUN4‐Mediated m5C Modification of circERI3 Promotes Lung Cancer Development by Altering Mitochondrial Energy Metabolism,” Cancer Letters 605 (2024): 217266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lee Y. J., Shin K. J., Jang H. J., et al., “GPR143 Controls ESCRT‐Dependent Exosome Biogenesis and Promotes Cancer Metastasis,” Developmental Cell 58 (2023): 320–334.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jeong S. M., Bui Q. T., Kwak M., Lee J. Y., and Lee P. C. W., “Targeting Cdc20 for Cancer Therapy,” Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta. Reviews on Cancer 1877 (2022): 188824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yang Q., Wang M., Xu J., et al., “LINC02159 Promotes Non‐Small Cell Lung Cancer Progression via ALYREF/YAP1 Signaling,” Molecular Cancer 22 (2023): 122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Volonte D., Sedorovitz M., and Galbiati F., “Impaired Cdc20 Signaling Promotes Senescence in Normal Cells and Apoptosis in Non‐Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells,” Journal of Biological Chemistry 298 (2022): 102405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hu H., Tou F. F., Mao W. M., et al., “microRNA‐1321 and microRNA‐7515 Contribute to the Progression of Non‐Small Cell Lung Cancer by Targeting CDC20,” Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences 38 (2022): 425–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Li Y., Sundquist K., Zhang N., Wang X., Sundquist J., and Memon A. A., “Mitochondrial Related Genome‐Wide Mendelian Randomization Identifies Putatively Causal Genes for Multiple Cancer Types,” eBioMedicine 88 (2023): 104432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhang L., Xu M., Zhang W., et al., “Three‐Dimensional Genome Landscape Comprehensively Reveals Patterns of Spatial Gene Regulation in Papillary and Anaplastic Thyroid Cancers: A Study Using Representative Cell Lines for Each Cancer Type,” Cellular & Molecular Biology Letters 28 (2023): 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kar S. P., Beesley J., Amin Al Olama A., et al., “Genome‐Wide Meta‐Analyses of Breast, Ovarian, and Prostate Cancer Association Studies Identify Multiple New Susceptibility Loci Shared by at Least Two Cancer Types,” Cancer Discovery 6 (2016): 1052–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nie F., Jiang J., and Ning J., “Exploration of the Prognostic Value of Methylation Regulators Related to m5C in Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma,” Medicine (Baltimore) 103 (2024): e38623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ma Y., Yang J., Ji T., and Wen F., “Identification of a Novel m5C/m6A‐Related Gene Signature for Predicting Prognosis and Immunotherapy Efficacy in Lung Adenocarcinoma,” Frontiers in Genetics 13 (2022): 990623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tsang M. J. and Cheeseman I. M., “Alternative CDC20 Translational Isoforms Tune Mitotic Arrest Duration,” Nature 617 (2023): 154–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wu F., Sun Y., Chen J., et al., “The Oncogenic Role of APC/C Activator Protein Cdc20 by an Integrated Pan‐Cancer Analysis in Human Tumors,” Frontiers in Oncology 11 (2021): 721797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang J., Xiao Z., Li P., et al., “PRMT6‐CDC20 Facilitates Glioblastoma Progression via the Degradation of CDKN1B,” Oncogene 42 (2023): 1088–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhao S., Zhang Y., Lu X., et al., “CDC20 Regulates the Cell Proliferation and Radiosensitivity of P53 Mutant HCC Cells Through the Bcl‐2/Bax Pathway,” International Journal of Biological Sciences 17 (2021): 3608–3621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wu F., Wang M., Zhong T., et al., “Inhibition of CDC20 Potentiates Anti‐Tumor Immunity Through Facilitating GSDME‐Mediated Pyroptosis in Prostate Cancer,” Experimental Hematology & Oncology 12 (2023): 67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Maan M., Agrawal N. J., Padmanabhan J., et al., “Tank Binding Kinase 1 Modulates Spindle Assembly Checkpoint Components to Regulate Mitosis in Breast and Lung Cancer Cells,” Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – Molecular Cell Research 1868 (2021): 118929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Association between NSUN4 expression and patient prognosis analyzed using the UALCAN project.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.