Abstract

The interaction of perfluoroaromatic compounds with 1-aminoadamantane followed by oxidation of the formed N-adamantylanilines with meta-chloroperoxybenzoic acid led to functionalized N-polyfluorophenyl-N-adamantylaminoxyls (mono- and diradicals) in high total yields. The molecular and crystal structures of N-adamantylanilines and the aminoxyl radicals obtained from them by oxidation have been established using single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis. The introduction of a substituent into the polyfluorinated moiety affects the arrangement of N-adamantylanilines in the crystal structure and the formation of hydrogen bonds; in addition, short contacts of the rare N···N type are present in crystals of 4-((adamantan-1-yl)amino)-perfluorobiphenyl. In crystals of the aminoxyls, oxygen atoms make unusually short contacts with C atoms of polyfluorinated aromatic rings giving rise to ferromagnetic exchange.

1. Introduction

In a broad family of organic stable radicals, polyfunctional N-tert-butyl-N-arylaminoxyls are the focus of much attention.1 For instance, these aminoxyls have been actively used as ligands for the construction of molecule-based magnets. This can be illustrated by heterospin complexes of M(hfac)2 with triplet tert-butylaminoxyl diradicals capable of cooperative magnetic ordering at 3.4–46.0 K2−5 or breathing crystals based on copper–nitroxide complexes.6−8 It is noteworthy that among synthesized triplet tert-butylaminoxyl diradicals, some compounds are able to undergo structural phase transitions, which result in a change in the product of molar magnetic susceptibility and temperature, similar to the changes observed in the complexes with spin transitions.9,10 Additionally, tert-butylaminoxyls capable of forming intermolecular H-bonds have become attractive as components for controlled assembly of high-dimensional paramagnetic systems.11−17 The use of tert-butylaminoxyls has also contributed to substantial progress in the creation of high-spin organic systems, the development of stable analogs of canonical hydrocarbon diradicals, and the design of magnetic switches and sensors.18−22 The synthesis of structurally complex paramagnetic compounds (consisting of several functional blocks, a donor, a chromophore, an acceptor, and tert-butylaminoxyl as the spin carrier) intended for studies on the relaxation of photoinduced excited states in spin-labeled chromophores has been reported (Figure 1).23

Figure 1.

Examples of polyfunctional tert-butylaminoxyls.

The wide range of applications of radicals has contributed to active development of the chemistry of this class of paramagnetic substances, including both modification of known methods and the invention of new efficient approaches. Their qualified application has made it possible to obtain and isolate a long series of tert-butylaminoxyls including mono-, bi-, and diradicals, special high-spin systems, and molecular-spin devices.24 Many of the obtained tert-butylaminoxyls possess high kinetic stability due to the presence of a bulky tert-butyl group (that shields the paramagnetic center) and an aromatic substituent (that ensures delocalization of the spin density). The high stability of N-tert-butyl-N-arylaminoxyls means that some paramagnetic derivatives can be applied to specially pretreated surfaces on which spin carriers are retained for several years.25

Whether the stability of these paramagnetic species would be preserved after a change of the tert-alkyl substituent, and whether this substituent could be multifunctional has been examined. Only a few stable aminoxyls with bulky alkyl substituents other than the tert-butyl group have been reported. An adamantyl-substituted aminoxyl obtained by the interaction of 3,5-dichloropyridyl lithium with nitrosoadamantane followed by oxidation of the resulting hydroxylamine has been reported (Scheme 1).26

Scheme 1. Only Reported Adamantyl-Substituted Aminoxyl Monoradical.

An adamantyl-substituted triplet diradical assembled by nucleophilic addition of lithiated 4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-4,5-dihydro-1H-imidazole-3-oxide-1-oxyl to 1-nitrosoadamantane with subsequent oxidation of the intermediate hydroxylamine has been prepared (Scheme 2). This diradical is stable under ambient conditions and possesses strong ferromagnetic interactions (ΔEST ∼ 880 K).27

Scheme 2. Synthesis of an Adamantyl-Substituted Triplet Diradical.

An attempt to prepare the corresponding aminoxyl radical via the oxidation of N-phenyl-N-9-triptycylamine led to the formation of 9-triptycylaminoxyl (6%) and N-(9-triptycyl)-1,4-benzoquinone imine (7%) in low yields, with a fair amount of the starting amine (41%) remaining unchanged (Scheme 3).28

Scheme 3. Synthesis of 9-Triptycylaminoxyl.

To expand the range of aminoxyls bearing various tert-alkyl groups and to reveal their stability and structural features, new adamantyl-substituted aminoxyls have been prepared. Further, an original approach has been used for the synthesis. It consists of replacing the fluorine atom at the first stage under the action of an amino derivative, followed by oxidation of the prepared anilines. The resultant paramagnets are the first aminoxyls bearing adamantyl and polyfluoroaromatic substituents.

2. Results and Discussion

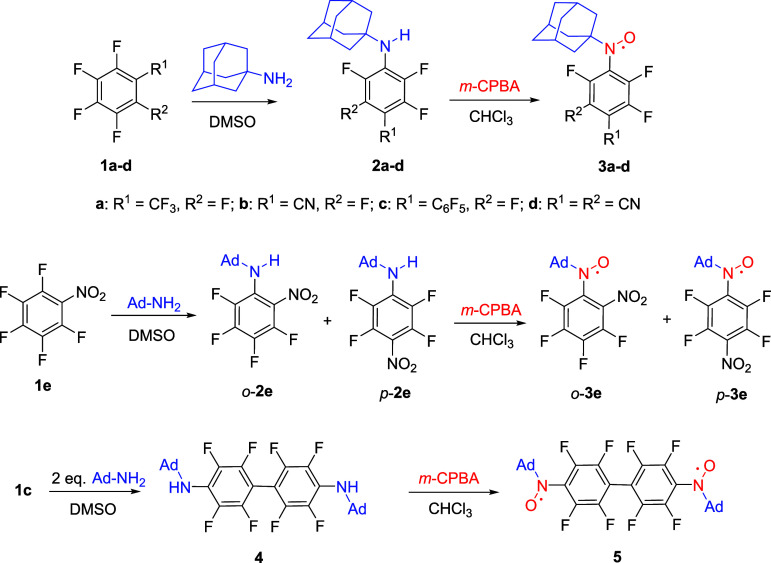

A typical method for the preparation of N-tert-butyl-N-arylaminoxyls starts with the reaction of the appropriate aromatic organometallic compound with tert-nitrosobutane, resulting in aryl tert-butylhydroxylamine, followed by its oxidation to the target radical product.29,30 Recently, a new approach was proposed involving nucleophilic substitution of a fluorine atom in an activated arene under the action of tert-butylamine and subsequent oxidation of the resulting amines to the target paramagnetic compounds.31−34 Here, this methodology was successfully applied to prepare adamantyl-substituted aminoxyls. The reaction of polyfluorinated arenes 1a–d with 1-aminoadamantane in DMSO led to adamantyl-amino-substituted fluorinated arenes 2 in nearly quantitative yields, with the exception of derivative 2c because diamine 4 also formed along with it. In other tested solvents, such as DMF and CHCl3, yields of anilines 2a–d were noticeably lower than in DMSO (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4. Synthesis of Adamantyl-Substituted Polyfluoroaryl Aminoxyls 3a–e and Aminoxyl Diradical 5 (Ad = 1-Adamantyl).

In reactions of polyfluorinated arenes 1a–d with 1-aminoadamantane, only para-substitution products formed, whereas the interaction of perfluoronitrobenzene 1e with aminoadamantane also gave a product of substitution of the ortho-fluorine atom, and the ratio of ortho- and para-substitution products, respectively o-2e and p-2e, was ∼1.3:1.0. A possible reason is the formation of hydrogen bonds between the amino and nitro groups, and this process almost equalizes energies of the respective activation barriers on the way to the ortho- and para-substitution products. The reaction of perfluorobiphenyl 1c with two equivalents of aminoadamantane caused substitution of two fluorine atoms at positions 4 and 4′ thereby producing diamine 4.

Molecular and crystal structures of all monoamino derivatives were solved by X-ray diffraction (XRD) (Tables S1, S10, and S16). Fluorinated anilines 2a and p-2e crystallize in triclinic space group P1̅ with two molecules per unit cell (which means one per asymmetric unit); in turn, aniline 2d crystallizes in the same space group with two independent molecules per asymmetric unit, and one of them is disordered (Figure 2 and Supporting Information). As to anilines 2b and o-2e, they tend to crystallize in monoclinic space groups P21 and P21/n with two and four molecules per unit cell, respectively. In the synthesized anilines, the geometry of the nitrogen atom matches sp2 hybridization. For example, in 2a, the sum of angles C7–N1–C8, C7–N1–H and C8–N1–H is 360°; dihedral angle C4–C7–N1–C8 is only 1.3°, which ensures effective conjugation of the nitrogen lone pair with the aromatic cycle and the shortening of the C7–N1 bond to 1.361(2) Å. In 2b and 2d, such torsion angles are also small: ≤ 17°.

Figure 2.

Molecular structure of 2a and 2d with low deviation of the adamantyl substituent. Molecules of 2c and o-2e with the numbering of selected atoms (characteristics of atomic displacement are shown with a 50% probability).

In o-2e and p-2e, the nitro group is turned relative to the aromatic ring by 25.3° and 40.5°, respectively, and in both compounds, the adamantyl substituent deviates from the plane of the aniline moiety, thus forming dihedral angle CAr–CAr–N1–CAd of 28.8° and 19.9°; the length of the C7–N1 bond is 1.358 Å. Among the obtained anilines, biphenyl derivative 2c differs substantially in structure. In it, the deviation of the adamantyl substituent from the aniline moiety is characterized by a large torsion angle of 80.7°, which also leads to a noticeable increase in C1–N1 bond length [1.407 (2) Å]. The pentafluorophenyl ring is rotated relative to the adjacent aromatic ring, and the dihedral angle between the mean planes of the rings is 53.7° (Figure 2 and Supporting Information).

The crystal structures of the obtained anilines contain numerous short contacts of the F···H and F···F types as well as others such as O···H in o-2e and p-2e, which is quite expected (ESI). Nevertheless, there are several notable features of the packaging of polyfluorinated anilines. The first feature is related to the specificity of hydrogen bond formation. In ortho-isomer o-2e, as expected, there is an intramolecular H-bond (Figure S5). In aniline 2d, the hydrogen bonds arise between the NH groups and the N atoms of the nitrile groups, giving ribbons {AB}n extending along crystallographic axis a (Figure 3). The ribbons are linked to each other by H-bonds and multiple short contacts involving nitrile groups (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Intermolecular H-bonds and short contacts between crystallographically independent molecules A and B in 2d.

Figure 4.

Intermolecular H-bonds and short intermolecular contacts between ribbons {AB}n in 2d.

Another remarkable feature is the short contact of the N···N type in crystals of 2c: 2.983 as compared to 3.1 Å (the sum of standard van der Waals radii of two N atoms; Figure 5). It is in this case that the adamantyl substituents deviate from the plane of the conjugated aniline system.

Figure 5.

A fragment of crystal structure of 2c showing short contact N···N.

The oxidation of anilines 2a–d, o-2e, p-2e, and 4 with meta-chloroperoxybenzoic acid in chloroform provided corresponding aminoxyls. The new aminoxyl radicals are stable enough, and it was possible to isolate them as red crystals in 60–70% yields (Scheme 4). Electron spin resonance (ESR) spectra from diluted (∼10–4 M), oxygen-free chloroform solutions of the radicals show characteristic triplet patterns owing to the hfs of an unpaired electron at the nitrogen nucleus. The spectra have no resolved substructure, and their modeling assuming the unresolved substructure from two equivalent fluorine nuclei at ortho-positions gave aN = 1.26–1.28 mT, aFortho = 0.11 mT (fixed), and giso = 2.0063–2.0065; a representative spectrum of nitroxide 3a is presented in Figure 6a.

Figure 6.

Experimental (black curve) and simulated (red curve) ESR spectra of monoradical 3a [aN = 1.26 mT, aFortho = 0.11 mT, giso = 2.0063(2)] and diradical 5 [aN/2 = 0.64 mT, giso = 2.0061(2)].

ESR spectra of diluted (∼10–4 M) chloroform solutions of diradical 5 contain the quintet at an intensity ratio of 1:2:3:2:1 (Figure 6b). This shows that exchange interactions J between radical moieties are much larger than the hyperfine coupling (J ≫ aN).35 Indeed, for the optimized structure of 5, calculations at the BS-UB3LYP level predicted antiferromagnetic exchange interaction with |J| = 1 cm–1 that was ∼30 GHz. A simulated spectrum (red curve) was calculated with |J| > 1.3 GHz and aN/2 = 0.64 mT.

Crystal structure analysis was crucial for gaining insight into the structure of the molecules being studied. Even though some freshly prepared radicals were red oils, repeated efforts were made to obtain them in a crystalline form. Finally, by crystallization from a cold hexane solution, aminoxyls 3b, 3c, and 5 were isolated as high-quality crystals, and their molecular and crystalline structure was determined by XRD (Table S10).

Radical 3b crystallizes in monoclinic space group P21/c with four molecules per unit cell. The aminoxyl group in radical 3b is twisted by a large angle (∼62°) relative to the aromatic ring (Figure 7), obviously owing to mutual effects of (i) steric repulsion between the adamantyl group and ortho-fluorines and (ii) electrostatic repulsion of dipoles C–F and N–O. The sum of angles O1–N2–C4, O1–N2–C8, and C4–N2–C8 is 358°, matching sp2 hybridization of the nitrogen atom. For radical 3c, two polymorphic modifications were obtained by crystallization and characterized by XRD. Both forms belong to the monoclinic system—space groups I2/a and P21/n—and contain one and two crystallographically independent molecules per asymmetric unit, respectively (Table S10). In both forms, the aminoxyl group is also twisted by a large angle (64–67°) relative to the aromatic ring, and nitrogen atom geometry corresponds to sp2 hybridization. In diradical 5, the bond lengths and angles are very similar to those of monoradical 3c; conformations adopted by molecules of monoradical 3b and diradical 5 in crystals are also similar, including in terms of angles between the N–O bond and the plane of the neighboring aromatic ring and angles between planes of the aromatic rings (Table 1).

Figure 7.

Molecular structure of aminoxyls 3b and 3c (characteristics of atomic displacement are shown with a 50% probability).

Table 1. Comparison of Selected Bond Lengths (Å) and Angles (°) for 3c (the First Polymorph) and 5.

| radical 3c | values | diradical 5 | values |

|---|---|---|---|

| O(1)–N(1) | 1.2822(15) | O(1)–N(1) | 1.288(8) |

| N(1)–C(10) | 1.4330(16) | N(1)–C(1) | 1.427(7) |

| N(1)–C(13) | 1.4890(16) | N(1)–C(7) | 1.489(8) |

| O(1)–N(1)–C(10) | 115.38(11) | O(1)–N(1)–C(1) | 116.09(8) |

| O(1)–N(1)–C(13) | 119.21(10) | O(1)–N(1)–C(7) | 118.54(4) |

| C(10)–N(1)–C(13) | 123.69(11) | C(1)–N(1)–C(7) | 123.52(4) |

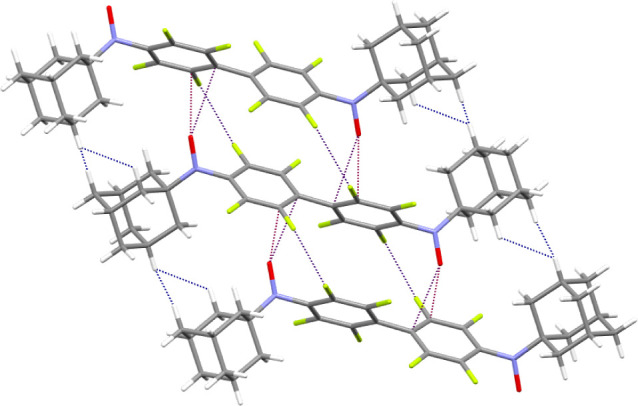

Analysis of crystal packing of aminoxyl 3b revealed short contacts F···H of 2.647 Å and atypical short ONO···CAr contacts of 2.871 and 3.091 Å, which formally bind molecules into chains along the c axis (Figure S6). The chains are packed into layers with short NCN···H contacts of 2.724 Å, which is shorter than the sum of corresponding van der Waals radii (2.75 Å).36 Overall, the formation of short contacts between the O atoms of the aminoxyl groups and the C atoms of the aromatic cycles is a characteristic feature of the packing of the obtained aminoxyls. For example, in crystals of diradical 5, short ONO···CAr contacts of 2.951 and 3.057 Å were observed, which link molecules into chains (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Short intermolecular contacts in 5.

Using BS-DFT, it was then selectively determined which exchange interactions could provide the aforementioned contacts. For nitroxide 3b, the analysis of pairwise exchange interactions {3b···3b} with NO···ON distances from 5.51 to 9.68 Å (Figure 9) showed that the strongest as well as ferromagnetic exchange interaction (J = +2.82 cm–1) is indeed realized in chains formed by short contacts between the O atoms of nitroxide and the C atoms of the aromatic ring (2.871 and 3.091 Å). The C atom with the shortest distance to the O atom has a small but noticeable negative spin population (−0.01), indicating ferromagnetic interaction according to the McConnell 1 model.37 For all other radical pairs, only very weak exchange interactions (with |J| ≤ 0.3 cm–1), both ferro- and antiferromagnetic, were predicted.

Figure 9.

A chain formed by short contacts between the O atoms of the nitroxide and the C atoms of the aromatic ring; the shortest C···O and O···O distances are given.

The atypical short ONO···CAr contacts not only form ferromagnetically bound chains in the case of radicals (Figure 9), they also promote the formation of dimers of diradicals 5 (RC···O = 2.95 Å) with ferromagnetic interaction between neighboring radical centers (J1 = +1.9 cm–1). The interaction between distant radical centers is negligible (J2 = −0.1 cm–1, Figure 10), and the intramolecular exchange interaction parameter was predicted to be slightly higher for the XRD geometry (J = −1.9 cm–1).

Figure 10.

A dimer of diradicals 5, as formed by short contacts between the O atoms of the nitroxide and the C atoms of the aromatic ring. The shortest C···O distances and the corresponding J parameters are given (Table S25).

Among the synthesized radicals, fluorinated aminoxyl o-3e is less stable and decomposes upon isolation; accordingly, it was characterized as a complex with Cu(hfac)2. The freshly prepared o-3e radical was subjected to complexation with half equivalent of Cu(hfac)2 in a CHCl3/n-heptane mixture, yielding the 1:2 complex [Cu(hfac)2(o-3e)2], which was recrystallized from hexane to obtain crystals suitable for XRD. The [Cu(hfac)2(o-3e)2] complex crystallizes in the orthorhombic Pbca space group with four molecules per unit cell (Figure 11). The asymmetric part of [Cu(hfac)2(o-3e)2] includes half-independent units located at the centers of symmetry. In the distorted octahedron around the copper ion, two ONO atoms occupy axial positions with dCu–O = 2.474 Å; equatorial Cu–Ohfac distances are 1.951 and 1.946 Å; the N2–O3–Cu1 angle is 127° (Table 2). The complex of Cu(hfac)2 with aminoxyl 3c of 1:2 composition was also obtained as well-shaped crystals. Their X-ray diffraction analysis also revealed elongated coordination bonds Cu–ONO (2.461 Å) and shortened bonds Cu–Ohfac (1.937 and 1.940 Å); the N1–O1–Cu1 angle is 123° (Figure 12 and Table S16). The resultant metal complexes are the first compounds of this class containing adamantyl-bearing ligands and coordinated paramagnetic moieties.

Figure 11.

Molecular structure of [Cu(hfac)2(o-3e)2] (H atoms are omitted; characteristics of atomic displacement are shown with a 50% probability).

Table 2. Selected Bond Lengths (Å) and Angles (°) for [Cu(hfac)2(o-3e)2].

| parameters | values |

|---|---|

| Cu(1)–O(3) | 2.4740(13) |

| Cu(1)–O(4) | 1.9460(13) |

| Cu(1)–O(5) | 1.9507(13) |

| O(3)–N(2) | 1.290(2) |

| N(2)–O(3)–Cu(1) | 86.11(2) |

| O(4)–Cu(1)–O(5) | 92.70(5) |

Figure 12.

Molecular structure of [Cu(hfac)2(3c)2] (H atoms are omitted; characteristics of atomic displacement are shown with a 50% probability).

The parameters of exchange interactions in the aforementioned complexes were also evaluated using the BS-UB3LYP approach. The calculations predicted that the exchange interactions between radicals and Cu(II) cations are ferromagnetic (which is characteristic of axial coordination of nitroxide radicals24 and moderate: J = 35 and 62 cm–1 for the complexes [Cu(hfac)2(o-3e)2] and [Cu(hfac)2(3c)2], respectively. The exchange interactions between radicals in the complex were predicted to be weak and antiferromagnetic (J = −1.3 and −3.2 cm–1, respectively, Table S25).

3. Conclusions

A new approach to the preparation of adamantyl-bearing aminoxyls was demonstrated: sequential substitution of the fluorine atom in polyfluorinated arenes by 1-aminoadamantane and oxidation of resulting N-adamantylaniline with m-CPBA. Molecular and crystal structures of N-adamantylanilines and the aminoxyl radicals obtained by oxidation were unambiguously confirmed by single-crystal XRD analysis. The title radicals exhibit high kinetic and chemical stability and are able to enter into heterospin complexes with Cu(hfac)2. Given that the adamantyl substituent is richer in the variety of different derivatives than the tert-butyl group is, this work opens up new possibilities for the design of functionalized paramagnets with desired magnetic characteristics.

4. Experimental Part

4.1. Reagents and General Procedures

Bis(hexafluoroacetylacetonato)copper-(II) [abbreviated as Cu(hfac)2] was prepared and purified by previously described procedures.38 Other chemicals were of the highest purity commercially available and were used as received. The progress of reactions was monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) on Silica gel 60 F254 aluminum sheets with hexane or CHCl3 as the eluent. The plates were visualized under UV radiation at 254 nm. Column chromatography was carried out on silica gel (0.063–0.200 mm). Melting points were measured by means of Stuart melting point apparatus SMP 30; solvents used for recrystallization are indicated after the melting points. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded for solutions in CDCl3 on a Bruker Avance 300 spectrometer (300.13 MHz for 1H and 282.37 MHz for 19F). Deuterated solvents were used to achieve a homonuclear lock, and the signals are presented in reference to the deuterated solvent peaks. IR spectra of samples in KBr were recorded on a BRUKER Vertex-70 FTIR spectrometer, and strong, medium, and weak peaks are labeled as s, m, and w, respectively. Molecular weights and elemental composition were determined using high-resolution mass spectrometry on a Bruker micrOTOF II instrument in electrospray ionization mode.

ESR spectra were acquired in deoxygenated and diluted toluene solutions at 295 K at concentrations of ∼10–4 M by means of a commercial Jeol X-band (9 GHz) spectrometer, JES-FA200, with the following settings: frequency, 9.87 GHz; microwave power, 2.0 mW; modulation amplitude, 0.2 mT; and time constant, 0.03 s. Isotropic g-factor values were measured experimentally using Mn(II)-doped MgO as a standard placed in the resonator simultaneously with the test solution. The spectra were simulated in Winsim v.0.96 software.

4.2. Synthesis of Radicals and Complexes

4.2.1. N-(2,3,5,6-Tetrafluoro-4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)adamantan-1-amine (2a)

A solution of perfluorotoluene (1.26 g, 5.3 mmol) and 1-aminoadamantane (0.97 g, 6.4 mmol) in DMSO (7 mL) was stirred on a magnetic stirrer for 48 h at 40–45 °C, then the reaction mixture was diluted with water and extracted with chloroform. Combined organic solutions were dried over sodium sulfate and evaporated thus giving the almost pure title product. Yield 1.92 g (98%), white crystals, mp 156–158 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, chloroform-d): δ = 1.57–1.75 (m, 7H, adamantyl protons); 1.79–1.97 (m, 4H, adamantyl protons); 1.98–2.21 (m, 4H, adamantyl protons); 3.9 (br.s, 1H, NH). 19F NMR (300 MHz, chloroform-d): δ = −55.2 (t, J = 21 Hz, 3F, CF3); – 143.3 (m, 2F, C2–F and C3–F); – 151.95 (dm, J = 21 Hz, 2F, C5–F and C6–F). IR (KBr): 3433, 2976, 2913, 2857, 1658, 1539, 1511, 1466, 1435, 1361, 1331, 1268, 1242, 1175, 1131, 1106, 1077, 1003, 970, 923, 870, 798, 713, 429 cm–1. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M – H]− Calcd for C17H15F7N– 366.1098; Found: 366.1111. The molecular and crystal structures of 2a were solved using single-crystal XRD data.

4.2.2. 4-((Adamantan-1-yl)amino)-2,3,5,6-tetrafluorobenzonitrile (2b)

It was obtained similar to 2a from perfluorobenzonitrile (1.03 g, 5.3 mmol) and 1-aminoadamantane (0.97 g, 6.4 mmol) in DMSO (7 mL). Yield 1.71 g (99%), yellowish solid, mp 182–184 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, chloroform-d): δ = 1.57–1.77 (m, 5H, adamantyl protons); 1.81–1.89 (m, 2H, adamantyl protons); 1.89–1.93 (m, 2H, adamantyl protons); 2.05–2.20 (m, 6H, adamantyl protons); 2.97 (br.s, 1H, NH). 19F NMR (300 MHz, chloroform-d): δ = −135.2 (dm, 2F, C2–F and C3–F); – 152.2 (dm, 2F, C5–F and C6–F). IR (KBr): 3412, 3294, 2917, 2894, 2856, 2227, 1658, 1640, 1571, 1532, 1508, 1455, 1440, 1368, 1347, 1321, 1190, 1140, 1124, 1094, 977, 818, 680, 548, 462 cm–1. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M – H]− Calcd for C17H15F4N2– 323.1177; Found: 323.1177. The molecular and crystal structures of 2b were solved by means of single-crystal XRD data.

4.2.3. N-(Perfluoro-(1,1′-biphenyl)-4-yl)adamantan-1-amine (2c)

It was obtained similar to 2a from perfluorobiphenyl (2.14 g, 6.4 mmol) and 1-aminoadamantane (0.97 g, 6.4 mmol) in DMSO (7 mL). Yield 1.99 g (67%), white crystals, mp 210–212 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, chloroform-d): δ 1.53–1.78 (m, 8H); 1.85–1.92 (m, 4H); 2.00–2.20 (m, 3H); 3.61 (s, 1H). 19F NMR (282 MHz, chloroform-d): δ −137.60 (m, 4H); −140.71 (m, 4H); −151.82 (m, 4H); −160.23 (m, 4H). HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ Calcd for C22H17F9N 466.1212; Found 466.1199. The molecular and crystal structures of 2c were solved on the basis of single-crystal XRD data.

4.2.4. 4-((Adamantan-1-yl)amino)-3,5,6-trifluorophthalonitrile (2d)

It was obtained similar to 2a from perfluorophthalonitrile (1.5 g, 7.5 mmol) and 1-aminoadamantane (1.36 g, 9.0 mmol) in DMSO (8 mL). Yield 2.43 g (98%), white crystals, mp 167–169 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, chloroform-d): δ = 1.61–1.78 (m, 6H, adamantyl protons); 1.79–1.98 (m, 6H, adamantyl protons); 2.01–2.21 (m, 3H, adamantyl protons); 4.38 (br.s., 1H, NH). 19F NMR (300 MHz, chloroform-d): δ = −118.81 (dd, J = 17.2, 8.3 Hz, 1F); −129.79 (dd, J = 20.9, 8.2 Hz, 1F); −136.86 (dd, J = 20.9, 17.2 Hz, 1F). IR (KBr): 3412, 3212, 2854, 2228, 1657, 1532, 1507, 1470, 1440, 1363, 1343, 1321, 1308, 1289, 1273, 1190, 1110, 1088, 1003, 975, 817, 803, 719, 469 cm–1. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ Calcd for C18H15F3N3+ 332.1369; Found: 332.1368. The molecular and crystal structures of 2d were solved using single-crystal XRD data.

4.2.5. N-(2,3,4,5-Tetrafluoro-6-nitrophenyl)adamantan-1-amine (o-2e) and N-(2,3,4,5-Tetrafluoro-4-nitrophenyl)adamantan-1-amine (p-2e)

A solution of perfluoronitrobenzene (1.13 g, 5.3 mmol) and 1-aminoadamantane (0.97 g, 6.4 mmol) in DMSO (10 mL) was stirred for 48 h at room temperature, then the reaction mixture was diluted with water and extracted with chloroform. Combined organic solutions were dried over sodium sulfate and evaporated. The residue was purified using TLC to obtain isomers o-2e and p-2e with yields 24% and 18%, respectively. Aminoxyl o-2e: yellow crystals, mp 184–186 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, chloroform-d): δ 1.02–0.75 (m, 2H); 1.37–1.17 (m, 5H); 2.06–1.57 (m, 8H); 4.04–3.92 (m, 1H). 19F NMR (282 MHz, chloroform-d): δ −143.93 (dt, J = 23.3, 8.3 Hz); −147.03 (ddd, J = 22.4, 20.1, 8.4 Hz); −155.65 (ddd, J = 20.1, 8.2, 5.6 Hz); −171.60 (ddd, J = 23.3, 22.3, 5.5 Hz). HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M – H]− Calcd for C16H15F4N2O2– 343.1075; Found: 343.1070. Aminoxyl p-2e: yellow crystals, mp 193–195 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, chloroform-d): δ 1.39–1.15 (m, 1H); 1.82–1.45 (m, 7H); 1.95–1.86 (m, 4H); 2.25–2.02 (m, 3H); 4.03 (br. s, 1H). 19F NMR (282 MHz, chloroform-d): δ −147.12 (m, 2F), −152.85 (m, 2F). HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M – H]− Calcd for C16H15F4N2O2– 343.1075; Found: 343.1072. The molecular and crystal structures of o-2e and p-2e were solved on the basis of single-crystal XRD data (see the main text).

4.2.6. N4,N4′-Di(adamantan-1-yl)-2,2′,3,3′,5,5′,6,6′-octafluoro-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4,4′-diamine (4)

A solution of perfluorotoluene (1.07 g, 3.2 mmol) and 1-aminoadamantane (0.97 g, 6.4 mmol) was stirred in DMSO (15 mL) for 48 h at 100–110 °C, then the reaction mixture was cooled, diluted with water and extracted with chloroform. Yield 1.09 g (57%), pale yellow crystals, mp 196–198 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, chloroform-d): δ 1.57–1.75 (m, 14H); 1.78–1.97 (m, 8H); 1.98–2.20 (m, 8H); 3.85 (s, 2H). 19F NMR (282 MHz, chloroform-d): δ −140.68 (m, 4H); −150.50 (m, 4H). HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ Calcd for C32H33F8N2 597.2511; Found 597.2500.

4.2.7. N-(Adamantan-1-yl)-N-(4-trifluoromethyl-2,3,5,6-tetrafluorophenyl)aminoxyl (3a)

A solution of aniline 2a (0.37 g, 1.0 mmol) and m-CPBA (0.21 g, 1.2 mmol) in CHCl3 (10 mL) was stirred at room temperature for 48 h. The solution was filtered through a layer of Al2O3, from which compounds were eluted with CHCl3. The eluate was diluted with heptane (10 mL) and concentrated in vacuo at room temperature down to 3–5 mL. Then, the solution was subjected to column chromatography (SiO2, column 1.5 × 10 cm, CHCl3 as an eluent). A red fraction of the aminoxyl radical was collected, diluted with heptane (10 mL), and concentrated under reduced pressure at room temperature to ∼2 mL. The solution was kept in a freezer at −15 °C, and the crystalline product was separated and analyzed. Yield 0.37 g (96%), red crystals. ESR (toluene): g = 2.0063(2), aN (1N) = 1.26 mT, aFortho = 0.11 mT.

4.2.8. N-(Adamantan-1-yl)-N-(4-cyano-2,3,5,6-tetrafluorophenyl)aminoxyl (3b)

It was obtained similar to 3a from aniline 2b (0.32 g, 1.0 mmol). Yield 0.31 g (91%), red crystals. ESR (toluene): g = 2.0061(2), aN (1N) = 1.27 mT, aFortho = 0.12 mT. The molecular and crystal structure of 3b was refined from single-crystal XRD data.

4.2.9. N-(Adamantan-1-yl)-N-(perfluoro-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)aminoxyl (3c)

It was obtained similar to 3a from aniline 2c (0.23 g, 0.5 mmol). Yield 0.21 g (87%), red crystals. ESR (toluene): g = 2.0060(1), aN (1N) = 1.28 mT, aFortho = 0.10 mT. The molecular and crystal structure of 3c was refined from single-crystal XRD data.

4.2.10. N-(Adamantan-1-yl)-N-(3,4-dicyano-2,5,6-trifluorophenyl)aminoxyl (3d)

It was obtained similar to 3a from aniline 2d (0.17 g, 0.5 mmol). Yield 0.16 g (92%), red crystals. ESR (toluene): g = 2.0059(3), aN (1N) = 1.26 mT, aFortho = 0.12 mT.

4.2.11. N-(Adamantan-1-yl)-N-(4-nitro-2,3,5,6-tetrafluorophenyl)aminoxyl (p-3e)

It was obtained similar to 3a from aniline p-2e (0.17 g, 0.5 mmol). Yield 0.16 g (90%), red crystals. ESR (toluene): g = 2.0057(2), aN (1N) = 1.26 mT, aFortho = 0.12 mT.

4.2.12. N4,N4′-Di(adamantan-1-yl)-2,2′,3,3′,5,5′,6,6′-octafluoro-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4,4′-diaminoxyl (5)

A solution of aniline 4 (0.30 g, 0.5 mmol) and m-CPBA (0.42 g, 2.4 mmol) in CHCl3 (15 mL) was stirred at room temperature for 48 h. The diradical was isolated as described for 3a. Yield 0.28 g (85%), red crystals. ESR (toluene): g = 2.0061(2), aN (1N) = 0.64 mT. The molecular and crystal structure of 5 was refined from single-crystal XRD data (see main text).

4.2.13. trans-Bis(1,1,1,5,5,5-Hexafluoropentane-2,4-dionato-κ2O,O′)bis{N-(adamantan-1-yl)-N-(2-nitro-2,3,5,6-tetrafluorophenyl)aminoxyl-κO}copper(II) ([Cu(hfac)2(o-3e)2])

A solution of aniline o-2e (76 mg, 0.22 mmol) and m-CPBA (47 mg, 0.27 mmol) in CHCl3 (5 mL) was stirred at room temperature for 48 h. The solution was filtered through a layer of Al2O3, from which compounds were eluted with CHCl3. The eluate was diluted with n-heptane (10 mL) and concentrated in vacuo at room temperature down to ∼3 mL. To this solution, a solution of Cu(hfac)2 prepared by heating under reflux for 20 min [a solution of Cu(hfac)2·H2O (50 mg, 0.1 mmol) in n-heptane (5 mL)] was added. The resultant mixture was allowed to stand at −15 °C for several days thereby affording brown crystals that were filtered off and air-dried; yield 45 mg (38%). The molecular and crystal structures of [Cu(hfac)2(o-3e)2] were solved by means of single-crystal XRD data (see main text).

4.2.14. trans-Bis(1,1,1,5,5,5-hexafluoropentane-2,4-dionato-κ2O,O′)bis{N-(adamantan-1-yl)-N-(perfluoro-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)aminoxyl-κO}copper(II) ([Cu(hfac)2(3c)2])

A solution of Cu(hfac)2·H2O (50 mg, 0.1 mmol) in n-heptane (5 mL) was heated under reflux for 20 min. The solution was cooled to room temperature, and a solution of aminoxyl 3c (96 mg, 0.2 mmol) in ether (1 mL) was introduced. The resultant mixture was allowed to stand at −15 °C for several days thereby giving brown crystals that were filtered off and air-dried; yield 65 mg (45%). The molecular and crystal structure of [Cu(hfac)2(3c)2] was refined from single-crystal XRD data (see main text).

4.3. Single-Crystal X-ray Diffractometry

X-ray diffraction data on structures 2a, 2b, 2c, p-2e, 3b, 3c (the first polymorph), [Cu(hfac)2(o-3e)2], and [Cu(hfac)2(3c)2] were collected at 100 K on a four-circle Rigaku Synergy S diffractometer equipped with a HyPix6000HE area-detector (kappa geometry, shutterless ω-scan technique), using monochromatized Cu Kα-radiation. The intensity data were integrated and corrected for absorption and decay in the CrysAlisPro software.39 The structure was solved by direct methods using SHELXT40 and refined on F2 using SHELXL-201841 in the OLEX2 program.42 All nonhydrogen atoms were refined with individual anisotropic displacement parameters. For structures 2a, 2b, 2c, and p-2e, locations of amino hydrogen atoms (named H1 for all structures) were found from the electron density-difference map; these hydrogen atoms were refined with individual isotropic displacement parameters. All other hydrogen atoms were placed in ideal calculated positions and refined as riding atoms with relative isotropic displacement parameters. For structures 3b, 3c, [Cu(hfac)2(o-3e)2], and [Cu(hfac)2(3c)2], all hydrogen atoms were placed in ideal calculated positions and refined as riding atoms with relative isotropic displacement parameters. The Mercury software43 was used for molecular graphics.

X-ray diffraction data on structures 2d, o-2e, and 3c (the second polymorph) were collected at 100 K on a Bruker Quest D8 diffractometer equipped with a Photon-III area-detector (graphite monochromator, shutterless φ- and ω-scan technique), using Mo Kα-radiation. The intensity data were integrated in the SAINT software44 and were corrected for absorption and decay using SADABS.45 The structure was solved by direct methods using SHELXT40 and refined on F2 using SHELXL-201841 in the OLEX2 program.42 All nonhydrogen atoms were refined with individual anisotropic displacement parameters. For structures 2d and o-2e, the locations of amino hydrogen atoms (H1, H1, and H1A) were found from the electron density-difference map; they were refined with the individual isotropic displacement parameters. All other hydrogen atoms were placed in ideal calculated positions and refined as riding atoms with relative isotropic displacement parameters. For the 2d structure, a sequential refinement of the fragment disorder resulting from the 180° rotation of the perfluoroaromatic ring was performed. The Mercury program43 was used for molecular graphics.

4.4. Computational Methods

The exchange

interaction parameters (J) between radicals and within

the Cu complexes with radicals  were evaluated using the spin-unrestricted

broken-symmetry (BS) approach46 using Yamaguchi’s

formula47

were evaluated using the spin-unrestricted

broken-symmetry (BS) approach46 using Yamaguchi’s

formula47

where energies of high-spin (HS) and low-spin (LS) states were calculated at the UB3LYP/def2-TZVP level48−50 for XRD geometry of radical pairs and complexes using the ORCA 5.0.1 software package.51 This approach has been previously shown24 to work well for intermolecular exchange interactions and intramolecular interactions in radical complexes of Cu(II). In the case of Cu(II) complexes, the exchange interaction parameters between Cu(II) and radical R were calculated for the monoradical complex, obtained by replacement of the second radical with its diamagnetic analog Ad-N(OH)R’. The interaction between radicals within the complex was evaluated for the complex obtained by replacement of paramagnetic Cu(II) with diamagnetic Zn(II) (Table S25).

Acknowledgments

The crystal structure determination was performed in the Department of Structural Studies at the Zelinsky Institute of Organic Chemistry (Moscow) for 2a, 2b, 2c, p-3e, 3b, 3c (the first polymorph), [Cu(hfac)2(o-3e)2], and [Cu(hfac)2(3c)2] and in the Laboratory for X-ray Diffraction Studies at the Nesmeyanov Institute of Organoelement Compounds (Moscow) for 2d, o-2e, and 3c (the second polymorph).

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.5c00505.

Accession Codes

CCDC 2390073 (2a), 2390071 (2b), 2390075 (2c), 2390065 (2d), 2390072 (p-2e), 2390067 (o-2e), 2390055 (3b), 2390053 (3c, the first polymorph), 2390051 (3c, the second polymorph), 2390054 ([Cu(hfac)2(3c)2]), and 2390056 ([Cu(hfac)2(o-3e)2]) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif, or by emailing data_request@ccdc.cam.ac.uk, or by contacting The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: + 44 1223 336033.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Tretyakov E. V.Chapter 5 – Preparation and characterization of magnetic and magnetophotonic materials based on organic free radicals. In Organic Radicals; Wang C., Labidi A., Lichtfouse E., Eds.; Elsevier, 2024; pp. 61–181. 10.1016/B978-0-443-13346-6.00005-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamura H.; Inoue K.; Hayamizu T. High-spin polynitroxide radicals as versatile bridging ligands for transition metal complexes with high ferri/ferromagnetic Tc. Pure Appl. Chem. 1996, 68, 243–252. 10.1351/pac199668020243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue K.; Hayamizu T.; Iwamura H.; Hashizume D.; Ohashi Y. Assemblage and Alignment of the Spins of the Organic Trinitroxide Radical with a Quartet Ground State by Means of Complexation with Magnetic Metal Ions. A Molecule-Based Magnet with Three-Dimensional Structure and High Tc of 46 K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 1803–1804. 10.1021/ja952301s. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh T.; Matsuda K.; Iwamura H.; Hori K. Tris[p-(N-oxyl-N-tert-butylamino)phenyl]amine, -methyl, and -borane Have Doublet, Triplet, and Doublet Ground States, Respectively. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 2567–2576. 10.1021/ja9920819. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue K.; Iwahori F.; Markosyan A. S.; Iwamura H. Synthesis and magnetic properties of one-dimensional ferro- and ferrimagnetic chains made up of an alternating array of 1,3-bis(N-tert-butyl-N-oxyamino)benzene derivatives and Mn(II)(hfac)2. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2000, 198, 219–229. 10.1016/S0010-8545(99)00225-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fedin M. V.; Drozdyuk I. Y.; Tretyakov E. V.; Tolstikov S. E.; Ovcharenko V. I.; Bagryanskaya E. G. EPR of Spin Transitions in Complexes of Cu(hfac)2 with tert-Butylpyrazolylnitroxides. Appl. Magn. Reson. 2011, 41, 383–392. 10.1007/s00723-011-0249-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drozdyuk I. Y.; Tolstikov S. E.; Tretyakov E. V.; Veber S. L.; Ovcharenko V. I.; Sagdeev R. Z.; Bagryanskaya E. G.; Fedin M. V. Light-Induced Magnetostructural Anomalies in a Polymer Chain Complex of Cu(hfac)2 with tert-Butylpyrazolylnitroxides. J. Phys. Chem. A 2013, 117 (30), 6483–6488. 10.1021/jp403977n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tretyakov E.; Tolstikov S.; Suvorova A.; Polushkin A.; Romanenko G.; Bogomyakov A.; Veber S.; Fedin M.; Stass D.; Reijerse E.; Lubitz W.; Zueva E.; Ovcharenko V. Crucial role of paramagnetic ligands for magneto-structural anomalies in “breathing crystals. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 51 (17), 9385–9394. 10.1021/ic301149e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimaki H.; Mashiyama S.; Yasui M.; Nogami T.; Ishida T. Bistable Polymorphs Showing Diamagnetic and Paramagnetic States of an Organic Crystalline Biradical Biphenyl-3,5-diyl Bis(tert-butylnitroxide). Chem. Mater. 2006, 18, 3602–3604. 10.1021/cm061222k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimaki H.; Ishida T. Organic Two-Step Spin-Transition-Like Behavior in a Linear S = 1 Array: 3′-Methylbiphenyl-3,5-diyl Bis(tert-butylnitroxide) and Related Compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 9598–9599. 10.1021/ja102890g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer J. R.; Lahti P. M.; George C.; Antorrena G.; Palacio F. Synthesis, Crystallography, and Magnetic Properties of 2-tert-Butylaminoxylbenzimidazole. Chem. Mater. 1999, 11, 2205–2210. 10.1021/cm990149d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lahti P. M.; Ferrer J. R.; George C.; Oliete P.; Julier M.; Palacio F. Hydrogen-bonded benzimidazole-based tert-butylnitroxides. Polyhedron 2001, 20, 1465–1473. 10.1016/S0277-5387(01)00637-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer J. R.; Lahti P. M.; George C.; Oliete P.; Julier M.; Palacio F. Role of Hydrogen Bonds in Benzimidazole-Based Organic Magnetic Materials: Crystal Scaffolding or Exchange Linkers. Chem. Mater. 2001, 13, 2447–2454. 10.1021/cm010322h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Field L. M.; Lahti P. M. Coordination complexes of 1-(4-[N-tert-butyl-N-aminoxyl]phenyl)-1H-1,2,4-triazole with paramagnetic transition metal dications. Inorg. Chem. 2003, 42, 7447–7454. 10.1021/ic0349050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maspoch D.; Catala L.; Gerbier P.; Ruiz-Molina D.; Vidal-Gancedo J.; Wurst K.; Rovira C.; Veciana J. Radical para-benzoic acid derivatives: Transmission of ferromagnetic interactions through hydrogen bonds at long distances. Chem. – Eur. J. 2002, 8, 3635–3645. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field L. M.; Lahti P. M. Magnetism of conjugated organic nitroxides: Structural scaffolding and exchange pathways. Chem. Mater. 2003, 15, 2861–2863. 10.1021/cm034225v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nagao O.; Kozaki M.; Shiomi D.; Sato K.; Takui T.; Okada K. Magnetic behavior of a manganese(II) complex of nitroxide-substituted 1,3-di(4-pyridyl)benzene. Polyhedron 2001, 20, 1653–1658. 10.1016/S0277-5387(01)00668-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ravat P.; Baumgarten M. Tschitschibabin type biradicals”: Benzenoid or quinoid?. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 983–991. 10.1039/C4CP03522D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravat P.; Baumgarten M. Positional Isomers of Tetramethoxypyrene-based Mono- and Biradicals. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 13649–13655. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b03056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okazawa A.; Terakado Y.; Ishida T.; Kojima N. A triplet biradical with double bidentate sites based on tert-butyl pyridyl nitroxide as a candidate for strong ferromagnetic couplers. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 17874–17878. 10.1039/C8NJ04180F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami H.; Tonegawa A.; Ishida T. A designed room-temperature triplet ligand from pyridine-2,6-diyl bis(tert-butyl nitroxide). Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 1306–1309. 10.1039/C5DT04218F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omokawa Y.; Hatano S.; Abe M. Electron-spin resonance (ESR) characterization of quintet spin-state bis-nitroxide-bearing cyclopentane-1,3-diyl diradicals. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2015, 28, 116–120. 10.1002/poc.3381. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giacobbe E. M.; Mi Q.; Colvin M. T.; Cohen B.; Ramanan C.; Scott A. M.; Yeganeh S.; Marks T. J.; Ratner M. A.; Wasielewski M. R. Ultrafast intersystem crossing and spin dynamics of photoexcited perylene-3, 4: 9, 10-bis (dicarboximide) covalently linked to a nitroxide radical at fixed distances. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 3700–3712. 10.1021/ja808924f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tretyakov E. V.; Ovcharenko V. I.; Terent’ev A. O.; Krylov I. B.; Magdesieva T. V.; Mazhukin D. G.; Gritsan N. P. Conjugated nitroxides. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2022, 91, RCR5025. 10.1070/RCR5025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murata H.; Baskett M.; Nishide H.; Lahti P. M. Adsorption of a Carboxylic Acid-Functionalized Aminoxyl Radical onto SiO2. Langmuir 2014, 30, 4026–4032. 10.1021/la5000952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z.; Mikuriya M. Syntheses, Crystal Structures, and Magnetic Properties of a Stable Aminoxyl Radical and Its Copper(II) Complex. Chem. Lett. 2008, 37, 400–401. 10.1246/cl.2008.400. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mikhailova M. V.; Dudko E. M.; Nasyrova D. I.; Akyeva A. Y.; Syroeshkin M. A.; Bogomyakov A. S.; Artyukhova N. A.; Fedin M. V.; Gorbunov D. E.; Gritsan N. P.; Tretyakov E. V.; Ovcharenko V. I.; Egorov M. P. Adamantyl-Substituted Triplet Diradical: Synthesis, Structure, Redox and Magnetic Properties. Dokl. Chem. 2022, 507, 270–280. 10.1134/S0012500822700148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Agawa C.; Otsuka K.; Minoura M.; Mazaki Y.; Yamamoto G. Synthesis and Stereochemistry of N-Phenyl-N-9-triptycylhydroxylamine Derivatives and Related Compounds. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2004, 77, 2273–2281. 10.1246/bcsj.77.2273. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stable Radicals: Fundamentals and Applied Aspects of Odd-Electron Compounds. Hicks R. G.; Eds.; John Wiley and Sons: Chichester, UK, 2010. 10.1002/9780470666975. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tretyakov E. V.; Ovcharenko V. I. The chemistry of nitroxide radicals in the molecular design of magnets. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2009, 78, 971–1012. 10.1070/RC2009v078n11ABEH004093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tretyakov E.; Fedyushin P.; Panteleeva E.; Gurskaya L.; Rybalova T.; Bogomyakov A.; Zaytseva E.; Kazantsev M.; Shundrina I.; Ovcharenko V. Aromatic SN F-Approach to Fluorinated Phenyl tert-Butyl Nitroxides. Molecules 2019, 24, 4493. 10.3390/molecules24244493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedyushin P.; Rybalova T.; Asanbaeva N.; Bagryanskaya E.; Dmitriev A.; Gritsan N.; Kazantsev M.; Tretyakov E. Synthesis of Nitroxide Diradical Using a New Approach. Molecules 2020, 25, 2701. 10.3390/molecules25112701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Politanskaya L. V.; Fedyushin P. A.; Rybalova T. V.; Bogomyakov A. S.; Asanbaeva N. B.; Tretyakov E. V. Fluorinated Organic Paramagnetic Building Blocks for Cross-Coupling Reactions. Molecules 2020, 25, 5427. 10.3390/molecules25225427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tretyakov E. V.; Fedyushin P. A. Polyfluorinated organic paramagnets. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2021, 70, 2298–2314. 10.1007/s11172-021-3346-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shinomiya M.; Higashiguchi K.; Matsuda K. Evaluation of the β Value of the Phenylene Ethynylene Unit by Probing the Exchange Interaction between Two Nitronyl Nitroxides. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 9282–9290. 10.1021/jo4015062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland R. S.; Taylor R. Intermolecular Nonbonded Contact Distances in Organic Crystal Structures: Comparison with Distances Expected from van der Waals Radii. J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 7384–7391. 10.1021/jp953141+. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell H. M. Ferromagnetism in Solid Free Radicals. J. Chem. Phys. 1963, 39, 1910. 10.1063/1.1734562. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.-L.; Li Y.-X.; Yang S.-L.; Zhang C.-X.; Wang Q.-L. Two copper complexes based on nitronyl nitroxide with different halides: Structures and magnetic properties. J. Coord. Chem. 2017, 70 (3), 487–496. 10.1080/00958972.2016.1271417. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rigaku. CrysAlisPro: Version 1.171.41. Rigaku Oxford Diffraction, 2021.

- Sheldrick G. M. SHELXT - Integrated space-group and crystalstructuredetermination. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A: Found. Adv. 2015, 71, 3–8. 10.1107/S2053273314026370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. C: Struct. Chem. 2015, 71, 3–8. 10.1107/S2053229614024218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolomanov O. V.; Bourhis L. J.; Gildea R. J.; Howard J. A. K.; Puschmann H. OLEX2: A complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009, 42 (2), 339–341. 10.1107/S0021889808042726. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Macrae C. F.; Sovago I.; Cottrell S. J.; Galek P. T. A.; McCabe P.; Pidcock E.; Platings M.; Shields G. P.; Stevens J. S.; Towler M.; Wood P. A. Mercury 4.0: From visualization to analysis, design and prediction. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2020, 53 (1), 226–235. 10.1107/S1600576719014092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruker. APEX-III. Bruker AXS Inc., Madison, Wisconsin, USA, 2019.

- Krause L.; Herbst-Irmer R.; Sheldrick G. M.; Stalke D. Comparison of silver and molybdenum microfocus X-ray sources for single-crystal structure determination. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2015, 48, 3–10. 10.1107/S1600576714022985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagao H.; Nishino M.; Shigeta Y.; Soda T.; Kitagawa Y.; Onishi T.; Yoshioka Y.; Yamaguchi K. Theoretical studies on effective spin interactions, spin alignments and macroscopic spin tunneling in polynuclear manganese and related complexes and their mesoscopic clusters. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2000, 198, 265–295. 10.1016/S0010-8545(00)00231-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soda T.; Kitagawa Y.; Onishi T.; Takano Y.; Shigeta Y.; Nagao H.; Yoshioka Y.; Yamaguchi K. Ab initio computations of effective exchange integrals for H–H, H–He–H and Mn2O2 complex: Comparison of broken-symmetry approaches. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2000, 319, 223–230. 10.1016/S0009-2614(00)00166-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.; Yang W.; Parr R. G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785–789. 10.1103/PhysRevB.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becke A. D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. 10.1063/1.464913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weigend F.; Ahlrichs R. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297–3305. 10.1039/b508541a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neese F. Software update: The ORCA program system—Version 5.0. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Comput. Mol. Sci. 2022, 12, e1606 10.1002/wcms.1606. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.