Abstract

Background

Luteolin, a natural flavonoid compound, has demonstrated anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and broad anti-tumor properties. Recent studies suggest that its anti-tumor effects are linked to enhanced CTL function—including proliferation, survival, and cytotoxicity-via inhibition of the YAP/Wnt signaling pathway in tumor cells. Consequently, luteolin has potential as an adjuvant in combination therapies with adoptive immunotherapy.

Methods

This study first assessed luteolin’s tumor-inhibitory effects in vitro and in vivo using cytotoxicity assays, Transwell invasion tests, wound healing assays, and analyses of post-treatment tumor growth and survival time. Additionally, we explored whether luteolin combined with a DC/tumor fusion vaccine could synergistically enhance overall antitumor efficacy by boosting activation, proliferation, cytokines secretion, and cytotoxicity of effector T cells.

Results

Our findings indicate that luteolin, as a standalone agent, can inhibit the proliferation and invasion of colon and lung cancer cells both in vitro and in vivo to a certain extent. When combined with activated CTLs, it upregulated the expression of CD25 and CD69 in effector cells and resulted in higher levels of IL-2, TNF-α, and IFN-γ secretion in vitro. In vivo, this combination significantly curtailed subcutaneous tumor growth and extended the mean survival time of tumor-bearing mice (HCT116, A549), outperforming luteolin monotherapy. Furthermore, the efficacy of this combination therapy may be attributable to enhanced apoptosis in tumor cells, reduced proliferation, and decreased YAP expression.

Conclusion

The combination of luteolin and DC/tumor fusion vaccine-activated CTLs presents a novel approach for cancer treatment. As an adjuvant, luteolin downregulates YAP expression in tumor cells, enhancing CTL proliferation, cytotoxicity, and survival, thus improving tumor recognition and selective targeting. This strategy is promising for safe and effective tumor treatment.

Introduction

Adoptive immunotherapy, which leverages cytotoxic T cells, has demonstrated therapeutic potential by promoting the regression of tumor cells (TCs). This process relies on the activation, expansion, targeting, and persistence of antitumor cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs). However, the efficacy of this immune response is often compromised by the tumor’s ability to evolve various immune evasion strategies. Notably, in the context of solid tumor therapy, it has been observed that immunosuppressive factors within the tumor microenvironment (TME) limit the cytotoxicity and proliferation of effector T cells in vivo [1]. The TME, characterized by its complexity, supports tumor progression while simultaneously depleting infused effector T cells. This dual effect is widely recognized as the primary mechanism that restricts the effectiveness of adoptive immunotherapy and constrains its broader clinical application [2–3]. In clinical practice, cancer treatment has shifted from empirical chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or targeted therapy alone to personalized approaches, making tumor treatment more precise and sustainable. However, challenges remain. the adoptive effector T cells usually need activators, such as PD-1/PD-L1 or CTLA-4 inhibitors, to promote proliferation and activation, which adds to the treatment cost [4]. Besides, in depth, the TME should be disarmed. Recently, some reports have suggested a combination of adoptive CTL immunotherapy with chemotherapy might inhibit tumor persistence and disrupt TME, although chemotherapy due to its toxic effects and the inhibition of T cells holds limited potential to give synergy in results [5–6].

In recent years, the research of active ingredients from natural products in tumor treatment has been a hot topic. Flavonoids are a kind of extensively distributed and biologically active compound that mainly exists in plants. Among them, luteolin is especially of a particular molecular structure and biological activity [7]. Luteolin is a flavonoid derived mainly from vegetables, fruits, and herbs, including Schizonepeta, Herba Ajugae, and Callicarpa nudiflora. The molecular formula is C15H10O6, with a molecular weight of 286.24 [8]. In recent decades, luteolin, with properties including antioxidant, anti-aging, and myocardial ischemia-relieving, was reported to possibly have some therapeutic effects on human solid tumors like liver cancer, colon cancer, and breast cancer. The attributed effects are due to the fact that it regulates many pathways in tumor cell growth, differentiation, and apoptosis [9–11]. Furthermore, luteolin does not act merely on TCs but has also been widely reported to have significant regulating effects on the TME [12]. While there is proof of low toxicity, strict toxicity studies will be required to clear luteolin for safety and further advance it into clinical practice [13]. Recent studies show that luteolin enhances tumor-specific CD8+ T lymphocyte activation through the inhibition of the Hippo pathway effector Yes-associated protein (YAP) and counteracts Wnt-induced suppression of CTL responses. The mechanistic action has been indicated to enhance the therapeutic effect of chemotherapy against cancer, because YAP itself has a critical role in the regulation of the MHC-I-related pathway that is influencing the proliferation and activation of CD8+ T lymphocytes [14, 15]. Therefore, in addition to its role as an antitumor agent, luteolin can serve as a T cell activator. Its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties may also alleviate tumor-related complications, making it an ideal adjuvant in combination therapies for tumors.

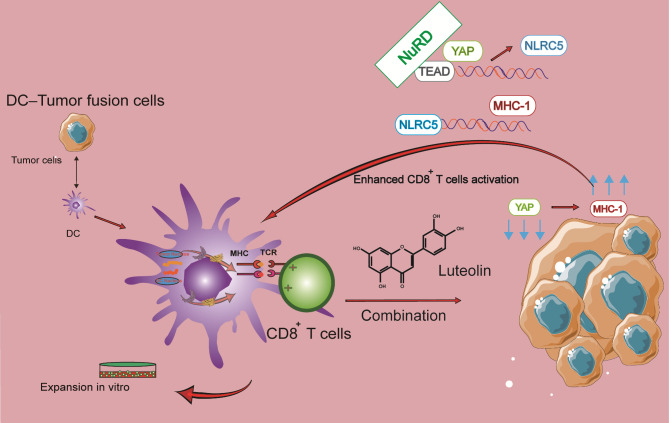

In this study, the inhibitory effects of luteolin on the cell lines of HCT116 and A549 were investigated. In addition, with the purpose to overcome negative effects of TME in adoptive CTL therapy to enhance the activation, proliferation, and survival of effector T cells within the tumor, a novel combination therapy was designed by combining adoptive, tumor-specific CTLs with luteolin. As shown in Fig. 1, a DC/tumor fusion vaccine with human colorectal carcinoma (HCRC), HCT116 cells, and human non-small cell lung cancer (HNSCL), A549 cells, was prepared to activate CD8+ T lymphocytes, followed by the treatment of tumors using a combination of effector T cells and luteolin. Luteolin exerts its antitumor effect not only directly but also as an activator in a synergistic manner on adoptive T cell therapy. We investigated the antitumor efficacy and the underlying mechanisms of tumor-specific CTLs elicited by a DC-tumor fusion vaccine in combination with luteolin.

Fig. 1.

Therapy strategy with FC + luteolin

YAP/TEAD(transcriptional enhanced associate domain) complex cooperated with the NuRD(nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase) complex to repress NLRC5(Nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain-like receptor family member) transcription. On the contrary, the Hippo pathway inhibits YAP activity, subsequently enhancing the expression of MHC-I genes, which ultimately potentiates antitumor immunity. In this study, FCs were created and subsequently used to stimulate CD8+ T cells. These T cells, after being activated by the FC, were further treated with luteolin to enhance their antitumor activity

Materials and methods

Animals and cells

Cell lines HCT116 and A549 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and grown at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in DMEM Gibco, USA), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Hyclone, USA), 100 U/mL of penicillin streptomycin (PS). Peripheral blood mononuclear cell(PBMCs) were extracted from healthy volunteers by gradient density centrifugation. The cells were then cultured in an immune cell medium containing 10% FBS from Hyclone in the USA. The culture was maintained at 37 °C with CO2.

The female NOD/SCID and BALB/c mice, 6–8 weeks old, were acquired from Vital River Animal Technology Laboratory in Beijing, China, and raised in laminar flow cabinets in a speciffc pathogen‑free environment (temperature, 23 ± 1˚C, humidity, 50 ± 10%, 12 h light/dark cycle starting at 7:00 a.m. with free access to food and water). The Animal Ethics Committee of Hainan Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital gave its approval to the protocols.

Transwell invasion and wound healing assay

For 24 h, HCT116 cells that were in the logarithmic growth phase were grown in chambers that contained Matrigel with 750 μL of media that included 40 μmol of luteolin (Selleck, USA). Following the incubation period, the chambers were taken out, cleaned three times with PBS, and then drained. Using a 1 mL solution of 4% paraformaldehyde, the membranes were fixed for a duration of 15 min. Next, 1 milliliter of 0.1% crystal violet was added to the membranes and let to sit in darkness for 20 min to stain them. The membranes were rinsed three times with PBS following staining. The last step was to photograph the membranes on slides and then count the cells.

The wound healing assay involved growing HCT116 cells to confluence in a 6-well dish. The monolayer of cells was vertically scratched using a pipette tip, and then cultivated for 48 h with or without 40 μmol of luteolin. A microscope was used to examine and photograph the region of the wound.

CD8+ T cells and DCs generation

The detailed steps of CD8+ T cells and dendritic cells(DCs) generation have been reported in our previous study [16–17]. Healthy subjects contributed their PBMCs for this study after receiving informed consent. To cultivate the cells, we first extracted them using density gradient centrifugation with Human Lymphocyte Separation Medium (Solarbio, China). We next added recombinant human IL-2 (100 U/mL, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) to the RPMI 1640 medium. Subsequently, non-adherent cells(mainly peripheral blood mononuclear cell) and adherent cells(mainly immature dendritic cells and monocyte) were isolated, respectively.

After further purification of the PBMCs collected above using the Act Sep™ CD3/CD28 Sorting activated magnetic beads from T&L Biotechnology in China, the obtained CD8+ lymphocytes were activated and cultured in the same medium. A complete medium including RPMI 1640, rhGM-CSF (1000 U/mL, R&D, USA) and rhIL-4 (500 U/mL, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was used to stimulate monocyte differentiation into DCs in the adherent cells. The Institutional Review Committee of the Hainan Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospita gave their approval to all investigations involving human samples.

Fusion of DC and tumor cells(FC)

The detailed steps of fusion of DC and tumor cells have been reported in our previous study [16–17]. A549 and HCT116 TCs were harvested, rendered inactive by 30 Gy X-irradiation, and subsequently labeled with PKH26 fluorescent dye (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). DCs were combined with TCs in a 2:1 ratio after being labeled with CFSE fluorescent dye (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). After that, PEG(Sigma, USA) was slowly and gently added along the wall of the tube and was water-bathed for 5 min at 37 °C. Next, The diluted collagen I (Sigma, USA) was then added and soaked in a 37 °C water bath for 30 min. The cells, upon PBS washing, were suspended again. The fusion of tumor cells and DCs was viewed by fluorescence microscopy (BX53, Olympus, Japan) to measure the fusion cells’ fluorescence intensity. To assess the DC maturation, the fusion cells were collected after 7 days of culture, a flow cytometry (Beckman Coulter CytoFlex S) was used to evaluate their MHC II, CD80, and CD86 expression levels.

Cytotoxicity assay

Annexin V-APC-labeled target cells (HCT116 or A549) were co-cultured with CD8+ T cells in 1:1, 5:1, 10:1, or 20:1 ratios for 6 h. The FC + luteolin group that received CD8+ T cells activated by FCs and and was again exposed to 40 μmol luteolin. Then harvest these target cells and dyed with 7-AAD (Keygen Biotech, China). Next, In order to ascertain cytotoxicity, flow cytometry was used to examine the proportion of Annexin V-APC+ 7-AAD+ cells in every group.

ELISA and ELISPOT assays

HCT116 or A549 cells were co-cultured with CD8+ T lymphocytes from each group at a 1:1 ratio. Commercially available ELISA kits (BD Biosciences, USA) were used to quantify the amounts of IL-2 and TNF-α in the supernatants. Luteolin was added at the concentration that had been previously determined. The fraction of T lymphocytes secreting IFN-γ was also evaluated using an ELISPOT kit. The streptavidin-AP-processed immunological complex that was specific to IFN-γ was then found in the BCIP/NBT substrate solution. Cellular Technology Limited’s ImmunoSpot S6 Ultimate-V analyzer was used to quantify the number of spots.

Modeling of xenograft tumors and in vivo therapy

The NOD/SCID mice were subcutaneously injected with HCT116 and A549 cells at a density of 5 × 105 cells/mouse. With 0.5ab² (where a is the largest diameter and b is the perpendicular diameter), the tumor volume was assessed every three days. The mice were split into groups and given intravenous injections of CD8+ T lymphocytes activated by a DC/tumor fusion vaccine via the tail vein when the tumor volume reached about 100 mm³, q7d × 4. Meanwhile, mice in FC + luteolin groups were injected luteolin with dosages of 25 or 50 mg/kg (Intraperitoneal injection), qd × 28. We measured the tumor volume every three days. After the last measurement, the mice were put down, and their tumors and important organs were taken out for more research. For the euthanasia procedure, the mice were placed in a carbon dioxide anesthesia box with carbon dioxide gas at a flow rate of 40% volume displacement per minute and increasing concentration to 100%, rendering them nconscious and ultimately leading to death. After euthanized, each mouse was individually checked, followed by cervical dislocation. The euthanasia methods employed for all mice were approved by The Ethics Committee of Hainan Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital and are in accordance with the AVMA Euthanasia Guidelines of Animals (2013 edition).

Maixin Biotech’s Kit-0005 and ABCAM’s ab81289 were used for immunostaining tumor samples against Ki-67 and human YAP, respectively. A method for detecting tumor cell apoptosis was employed by immunofluorescence, namely the TUNEL assay developed by Roche in Switzerland. To test the toxicity of FC + luteolin treatment in vivo, after the healthy BALB/c mice received a complete treatment, their spleen, kidney, heart, lungs, liver, and brain were among the major organs that were harvested, cut into sections, and stained with HE. The images were captured by means of a Nikon, Japan-based fluorescence microscope.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis and figure preparation were conducted utilizing GraphPad Prism 6.02. Statistical comparisons were conducted employing Student’s t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA). A p-value below 0.05 was deemed statistically significant. The data are expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD).

Results

Luteolin inhibits the activity of tumor cells to a certain extent

The effect of luteolin on tumor cell inhibition was first evaluated at different concentrations. The data indicated that the viability of HCT116 and A549 TCs diminished in a dose-dependent manner following luteolin exposure. More importantly, luteolin also significantly inhibited normal human cells (293T) at concentrations exceeding 40 μmol (Fig. 2A). Therefore, 40 μmol was selected as the safe concentration for the in vitro experiments in this study. The invasion and wound healing assays confirmed that luteolin inhibits the migration and invasion of TCs (Fig. 2B-C). In tumor-bearing mice, luteolin demonstrated a certain antitumor effect, delaying tumor growth and improving survival time (Fig. 2D-E).

Fig. 2.

Luteolin inhibits the activity of tumor cells in vitro and vivo. (A) Effect of different concentrations luteolin on the activity of HCT116 and A549 cells detected by CCK-8 method. n = 3. (B) The effect of luteolin on the invasion of HCT116 cells. The spots represent the number of cells that have crossed the bottom membrane. n = 3, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. (C) Effect of Luteolin on Scratches in HCT116 cells. (D-E) a xenograft models with HCT116 cell line was constructed. The tumor size was measured every 3 days and recorded survival time. 5 mice/per group, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001

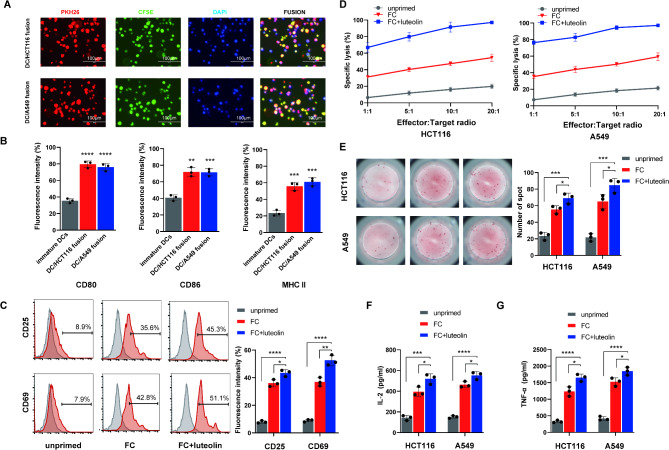

Preparation of DC/tumor fusion vaccine

In the experimental setup, TCs (HCT116 or A549) were labeled with CFSE, while DCs were tagged with PKH26. These cells were then co-cultured for seven days in the presence of PEG. The data showed that both fluorescence and high expression of maturation markers were present on the DC/tumor fusion cells (Fig. 3A-B), indicating successful preparation of the fusion cells.

Fig. 3.

Functional verification of FC + luteolin treatment on tumor cells in vitro. (A) DCs and HCT116 or A549 cells were co-cultured in the presence of PEG 2000, respectively. DCs were stained with PKH26 (red), tumor cells were stained with CFSE (green), and nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar = 50 μm. (B) DC/tumor fusion cells expressed high levels of costimulatory CD80, CD86 and MHC II. n = 3, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. (C) The CD8+ T lymphocytes co-culture with HCT116 cells, with FC, or FC + luteolin(40 μmol), respectively, for 5 days. CD8+ T lymphocytes cells alone as the blank control group(unprimed). Next, these lymphocytes were collected and stained with PE-conjugated anti-CD25 or anti-CD69 mAb and analyzed by flow cytometry for the activation. n = 3, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001.(D) The CD8+ T lymphocytes were co-incubated with PKH26-prestained HCT116 or A549 cells with DC/tumor fusion vaccine at E/T ratio 1:1,5:1,10:1 or 20:1, with FC, or FC + luteolin(40 μmol) for 6 h. propidium iodide(Pl) was used for lysed cell staining. The ratios of PHK26+PI+cell were measured by flow cytometry. n = 3. (E) ELISPOT was used to detect the activation of CD8+ T lymphocytes in different groups to stimulate IFN-γ secretion of corresponding tumor cells. Representative image of ELISPOT plate readout analyzing the frequency of IFN-γ-secreted CD8+ T lymphocytes are shown histograms represent data of the triplicates for 3 × 105 cells from three independent ELISPOT assays, and shown as bars of means + S.D. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001. (F-G) After co-culture with CD8+ T lymphocytes and tumor cells, supernatants were collected andmeasuring for secretion of IL-2 and TNF-a by the ELISA kits. data indicated the increased secretion of above two cytokines from the target cell-reactive CD8+ T lymphocytes stimulated by FC, or FC + luteolin. n = 3, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001

Luteolin enhances proliferation, activation, and cytotoxicity of CD8+ T cells activated by DC/tumor fusion cells in FC + luteolin treatment

The stimulatory effect of luteolin on the activation and proliferation of CD8+ T cells, which were activated using the FC, was confirmed by the elevated expression levels of CD25 and CD69 (Fig. 3C). Further studies showed that when these CD8+ T cells were treated with luteolin, a synergistic effect led to the elimination of a larger proportion of matched TCs (Fig. 3D). To investigate the release of inflammatory cytokines and verify the cytotoxic mechanisms, ELISA and ELISPOT assays were conducted. The results confirmed that FC + luteolin treatment increased the levels of inflammatory mediators (IL-2, TNF-α) after exposure to HCT116 and A549 cells, compared to FC alone (Fig. 3F-G). As expected, ELISPOT results showed a higher number of IFN-γ secreting spots in the FC + luteolin groups (Fig. 3E).

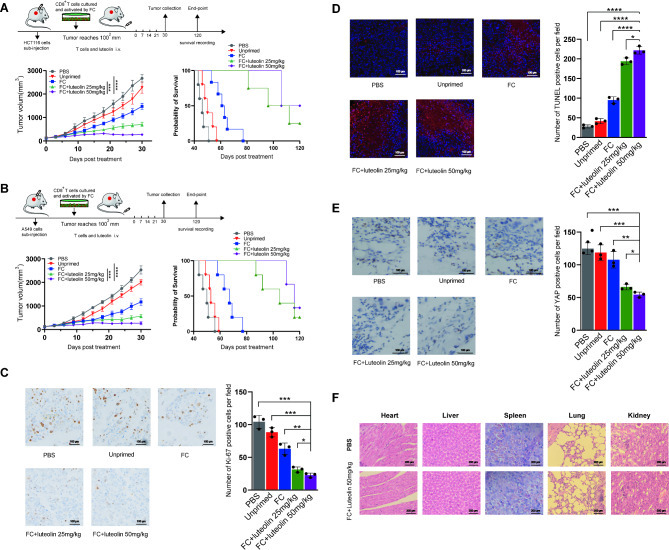

Activated CD8+ T cells combined with luteolin induce stronger antitumor effects in tumor-bearing mice

The study further examined the suppression of tumor growth in xenograft models established with HCT116 and A549 cell lines. It was observed that adoptive CD8+ T cells, stimulated by the FC, significantly inhibited tumor growth and enhanced survival in these models, demonstrating superior performance over both the unprimed T cells and the PBS control groups. However, long-term survival was not achieved. When these effector T cells were combined with luteolin (25 or 50 mg/kg), a more pronounced antitumor effect was observed, with a certain percentage of the mice surviving for more than 120 days, suggesting promising potential for clinical applications(Fig. 4A-B). Investigations into the mechanism behind the FC + luteolin treatment’s efficacy focused on the analysis of Ki-67 and YAP expression levels, along with apoptosis markers in the tumors, using both immunohistochemical and immunofluorescence staining techniques. The analyses revealed a notable reduction in Ki-67 and YAP positive cells in the FC + luteolin groups compared to those in the PBS, unprimed, and FC only groups (Fig. 4C, E). Moreover, substantial apoptosis was observed, as evidenced by the TUNEL assay(Fig. 4D). These findings suggest that the combination of adoptive CD8+ T cells activated by the FC with luteolin effectively curtailed tumor progression by impeding tumor cell proliferation through the YAP signaling pathway and enhancing apoptotic activity.

Fig. 4.

Functional verification of FC + luteolin treatment in vivo. (A-B) xenograft models with HCT116 and A549 cell line was constructed. The tumor size was measured every 3 days and recorded survival time. 5 mice/per group, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. (C) Ki-67 detection by immunohistochemical stain. n = 5, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (D) The number of apoptosis cells detection by immunofluorescence. n = 5, *P < 0.05, ****P < 0.0001. (E) YAP expression detection by immunohistochemical stain. n = 5, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (F) Balb/c mice were received a complete FC + luteolin 50 mg/kg treatment or PBS. Sections from primary organs were stained with hematoxylin-eosin and images were captured using microscopy

Moreover, the potential in vivo toxicity of the FC + luteolin treatment was assessed through HE staining. The analysis verified the absence of toxicological effects in critical organs, including the kidneys, lungs, spleen, liver, heart, and brain of the treated mice (Fig. 4F).

Discussion

The anticancer effect of luteolin has been confirmed in various tumor cell lines and animal models, including breast cancer, and leukemia [11, 18–20]. The mechanism of action is primarily linked to the inhibition of cell cycle progression, the suppression of proliferation signals mediated by growth factor receptors, and the activation of pro-apoptotic pathways [8, 21]. In this study, our data also show that luteolin can inhibit the proliferation and invasion of colon and lung cancer cells to some extent. However, this effect is limited and does not meet expectations, as it fails to consistently hinder tumor growth and recurrence. Given luteolin’s low toxicity, it holds great potential for development into an effective anticancer drug or for use in specific tumor therapies. While luteolin’s effectiveness as a standalone anticancer agent could benefit from enhancement, its utility in combination therapies is increasingly recognized due to its concurrent anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anti-estrogenic effects [10, 22, 23]. Research has highlighted luteolin’s involvement in enhancing antitumor immunity, notably through its modulation of CTL activities [24–25]. For instance, luteolin is known to bolster the immune responses of CTLs by activating pathways critical for the survival, proliferation, and metabolic functions of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) [26]. Furthermore, luteolin directly suppresses PD-L1 expression in TCs, thus disrupting the PD-1/PD-L1 interaction and promoting CTL proliferation, viability, and ability to counteract tumor invasion [27]. Therefore, due to its limited direct anticancer efficacy, luteolin is better suited as an adjuvant for adoptive immune cell therapies (especially APC-mediated) to improve the survival and infiltration of effector cells, thereby generating a synergistic effect.

Dendritic cells, as powerful APCs, are pivotal in triggering antitumor immune responses and are a focal point of recent research [28]. Currently, several techniques are employed to present tumor-associated antigens to DCs for cancer vaccine applications, including RNA or DNA transfection, peptide or protein loading, and fusion with TCs. The strategy of creating a FC by merging entire TCs with DCs represents a novel cancer treatment approach [29]. Following immune stimulation by DCs, FC can present a wide array of tumor antigens, both recognized and novel. In prior research, we devised an effective technique for generating DC/tumor cell vaccines, which prompted tumor-specific CTL responses and produced substantial antitumor outcomes in both preclinical in vitro and in vivo settings [16–17]. Expanding on these initial findings, this study investigates whether luteolin could further boost the proliferation and survival of these effector cells when used as an adjuvant alongside the FC. To enhance antigen specificity and cytotoxic capabilities of CTLs, we engineered two DC/tumor vaccines by fusing immature DCs with prevalent tumor cell lines (HCT116 and A549). The maturation of these fusion cells was predominantly gauged by the upregulation of co-stimulatory molecules such as CD80 [30]. The elevated expression levels of these molecules in both FCs, relative to immature DCs, suggest that the fusion process fosters DC maturation and improves their antigen-presenting efficacy. Our findings demonstrated that the FC efficiently triggered the formation of tumor-specific CTLs by delivering tumor antigens, subsequently enhancing their proliferation, activation, and cytotoxicity.

To validate the efficacy of the luteolin-enhanced FC-activated CTL treatment in vivo, we established two subcutaneous tumor transplantation models in SCID mice, representing lung and colon cancers. The results confirmed that this therapeutic approach, combining FC-activated CTLs with luteolin, notably impeded tumor progression and extended the average survival duration in the mice. Remarkably, most of the mice that received this treatment survived beyond the 120 day observation period, maintaining very small tumor volumes. This suggests that they survived with tumors for long periods without recurrence. Previous research has reported that adoptive immunotherapy often has limited efficacy in mesenchymal and epithelioid cancer cell populations due to upregulation of the YAP/Wnt pathway. However, other studies have confirmed that the antitumor activity of luteolin is associated with the downregulation of this pathway [31]. In this study, we further verified that luteolin enhances the function and survival of T cells by downregulating the expression of YAP in TCs when used in combination therapy, achieving a strong synergistic therapeutic effect. As expected, our results demonstrated that the YAP level in TCs was significantly reduced after treatment with luteolin combined with activated CTLs, compared with CTLs alone. Consequently, there was a significant decrease in both proliferative (Ki-67) and apoptotic (TUNEL) indices of TCs in the mice, aligning with the targeted elimination of TCs by the synergistic action of activated CTLs and luteolin.

In summary, since luteolin possesses anti-tumor, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant activities, we propose its use as an adjuvant to enhance the function and survival of adoptive CTLs, achieving a better synergistic effect. We have designed a novel tumor treatment strategy using FC-activated CTLs combined with luteolin, providing preclinical evidence for their therapeutic potential. This optimally designed dual activation therapy could enhance CTL proliferation, cytotoxicity, and survival, allowing for better recognition and selective targeting of TCs. This strategy appears to be safe and highly effective for tumor treatment, offering the benefits of both natural product therapy and adoptive immunotherapy. It also reduces the dosage of therapeutic drugs and lowers the risk of adverse reactions in antitumor therapy.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank the Public Research Center of Hainan Medical University(Hainan Provincial Academy of Medical Sciences) for their support and assistance interms of instruments and facilities.

Abbreviations

- APCs

Antigen-presenting cells

- CTLs

Cytotoxic T lymphocytes

- DCs

Dendritic cells

- FC

DC/tumor fusion cell

- TCs

Tumor cells

- TME

Tumor microenvironment

- YAP

Yes-associated protein

Author contributions

Wu Wang and Shiguo Yuan conceived and designed the present study. Zhiheng Lai and Yanyang Pang performed the molecular and cellular experiments in vitro. Yujing Zhou, Leiyuan Chen1 and Kai Zheng performed in the analysis of in vivo experiments. Wu Wang managed the Written of the manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported, in part, by grants from Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 823MS150), Hainan Provincial Health Industry Research Project(No. 22A200106), Project supported by Hainan Province Clinical Medical Center([2021] No. 276).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study areavailable from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained for collection of human PBMC samples fromthe local ethics committee of Hainan Medical University and inaccordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Written informed consent was signed all volunteer. All procedures involving animal care and use were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Hainan Medical University and were in accordance with the National Policy and Regulations on Use of Laboratory Animals. All animal experiments were carried out in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Zhiheng Lai, Yanyang Pang, Yujing Zhou, Leiyuan Chen and Kai Zheng contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Shiguo Yuan, Email: ysg@smu.edu.cn.

Wu Wang, Email: lxd8860@163.com.

References

- 1.Rosenberg SA. Progress in human tumour immunology and immunotherapy. Nature. 2001;411(6835):380–4. 10.1038/35077246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giles JR, Globig AM, Kaech SM, Wherry EJ. CD8+ T cells in the cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity. 2023;56(10):2231–53. 10.1016/j.immuni.2023.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen DS, Mellman I. Oncology meets immunology: the cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity. 2013;39(1):1–10. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi Y, Shi Y, Haymaker CL, Naing A, Ciliberto G, Hajjar J. T-cell agonists in cancer immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8(2):e000966. 10.1136/jitc-2020-000966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Restifo NP, Dudley ME, Rosenberg SA. Adoptive immunotherapy for cancer: harnessing the T cell response. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12(4):269–81. 10.1038/nri3191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan JD, Lai J, Slaney CY, Kallies A, Beavis PA, Darcy PK. Cellular networks controlling T cell persistence in adoptive cell therapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21(12):769–84. 10.1038/s41577-021-00539-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ross JA, Kasum CM. Dietary flavonoids: bioavailability, metabolic effects, and safety. Annu Rev Nutr. 2002;22:19–34. 10.1146/annurev.nutr.22.111401.144957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Imran M, Rauf A, Abu-Izneid T et al. Luteolin, a flavonoid, as an anticancer agent: a review [published correction appears in biomed Pharmacother. 2019;116:109084. 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.108612 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Ma J, Mo J, Feng Y, et al. Combination of transcriptomic and proteomic approaches helps unravel the mechanisms of luteolin in inducing liver cancer cell death via targeting AKT1 and SRC. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15:1450847. 10.3389/fphar.2024.1450847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zheng Y, Li L, Chen H, et al. Luteolin exhibits synergistic therapeutic efficacy with erastin to induce ferroptosis in colon cancer cells through the HIC1-mediated inhibition of GPX4 expression. Free Radic Biol Med. 2023;208:530–44. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2023.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu HT, Lin J, Liu YE, et al. Luteolin suppresses androgen receptor-positive triple-negative breast cancer cell proliferation and metastasis by epigenetic regulation of MMP9 expression via the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Phytomedicine. 2021;81:153437. 10.1016/j.phymed.2020.153437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zong S, Li X, Zhang G, et al. Effect of luteolin on glioblastoma’s immune microenvironment and tumor growth suppression. Phytomedicine. 2024;130:155611. 10.1016/j.phymed.2024.155611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yao C, Dai S, Wang C, et al. Luteolin as a potential hepatoprotective drug: molecular mechanisms and treatment strategies. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;167:115464. 10.1016/j.biopha.2023.115464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mediratta K, El-Sahli S, Marotel M, et al. Targeting CD73 with flavonoids inhibits cancer stem cells and increases lymphocyte infiltration in a triple-negative breast cancer mouse model. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1366197. 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1366197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peng L, Zhou L, Li H, et al. Hippo-signaling-controlled MHC class I antigen processing and presentation pathway potentiates antitumor immunity. Cell Rep. 2024;43(4):114003. 10.1016/j.celrep.2024.114003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang W, Pang Y, Wang X, et al. A novel CTLA-4 blocking strategy based on nanobody enhances the activity of dendritic cell vaccine-stimulated antitumor cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Cell Death Dis. 2023;14(7):406. 10.1038/s41419-023-05914-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang W, Sun Q, Zhang X, et al. A novel doxorubicin/CTLA-4 blocker co-loaded drug delivery system improves efficacy and safety in antitumor therapy. Cell Death Dis. 2024;15(6):386. 10.1038/s41419-024-06776-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fu W, Xu L, Chen Y, et al. Luteolin induces ferroptosis in prostate cancer cells by promoting TFEB nuclear translocation and increasing ferritinophagy. Prostate. 2024;84(3):223–36. 10.1002/pros.24642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nazim UM, Park SY. Luteolin sensitizes human liver cancer cells to TRAIL–induced apoptosis via autophagy and JNK–mediated death receptor 5 upregulation. Int J Oncol. 2019;54(2):665–72. 10.3892/ijo.2018.4633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.21 Sak K, Kasemaa K, Everaus H. Potentiation of luteolin cytotoxicity by flavonols fisetin and quercetin in human chronic lymphocytic leukemia cell lines. Food Funct. 2016;7(9):3815–24. 10.1039/c6fo00583g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin Y, Shi R, Wang X, Shen HM. Luteolin, a flavonoid with potential for cancer prevention and therapy. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2008;8(7):634–46. 10.2174/156800908786241050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang X, Zhang L, Si H. Combining luteolin and curcumin synergistically suppresses triple-negative breast cancer by regulating IFN and TGF-β signaling pathways. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024;178:117221. 10.1016/j.biopha.2024.117221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.eon YW, Suh YJ. Synergistic apoptotic effect of celecoxib and luteolin on breast cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2013;29(2):819–25. 10.3892/or.2012.2158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Y, Zeng Y, Yang W, Wang X, Jiang J. Targeting CD8+ T cells with natural products for tumor therapy: revealing insights into the mechanisms. Phytomedicine. 2024;129:155608. 10.1016/j.phymed.2024.155608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cai S, Gou Y, Chen Y, et al. Luteolin exerts anti-tumour immunity in hepatocellular carcinoma by accelerating CD8+ T lymphocyte infiltration. J Cell Mol Med. 2024;28(17):e18535. 10.1111/jcmm.18535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tian L, Wang S, Jiang S, et al. Luteolin as an adjuvant effectively enhances CTL anti-tumor response in B16F10 mouse model. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;94:107441. 10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang ZB, Wang WJ, Xu C, et al. Luteolin and its derivative apigenin suppress the inducible PD-L1 expression to improve anti-tumor immunity in KRAS-mutant lung cancer. Cancer Lett. 2021;515:36–48. 10.1016/j.canlet.2021.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steinman RM, Banchereau J. Taking dendritic cells into medicine. Nature. 2007;449:419–26. 10.1038/nature06175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenblatt J, Vasir B, Uhl L, Blotta S, Macnamara C, Somaiya P, et al. Vaccination with dendritic cell/tumor fusion cells results in cellular and humoral antitumor immune responses in patients with multiple myeloma. Blood. 2011;117:393–402. 10.1182/blood-2010-04-277137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gong J, Chen D, Kashiwaba M, Kufe D. Induction of antitumor activity by immunization with fusions of dendritic and carcinoma cells. Nat Med. 1997;3:558–61. 10.1038/nm0597-558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stampouloglou E, Cheng N, Federico A, et al. Yap suppresses T-cell function and infiltration in the tumor microenvironment. PLoS Biol. 2020;18(1):e3000591. 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study areavailable from the corresponding author on reasonable request.