Abstract

Background

To examine the parallel mediating effects of social networking site use and self-esteem on the internalization of homophobia among LGB individuals, with a focus on variations across gender and coming out status.

Methods

A sample of 657 homosexual and bisexual individuals (mean age: 22.81 ± 6.15 years) was recruited through online social media platforms. This study examined romantic relationship status, coming out status, and the use of social networking sites. It also assessed internalized homophobia using the Internalized Homophobia Scale (IHS), social network site engagement with the Social Network Site Intensity Scale (SNSIS), and self-esteem using the Self-Esteem Scale (SES). SPSS PROCESS was used to examine the parallel mediation model, while Amos was employed to analyze the moderated mediation model.

Results

The social networking site use and self-esteem serve as parallel mediators in the relationship between romantic relationship status and the internalized homophobia. The mediating effect accounted for 23.75% and 21.88% of the total effect, respectively. Gender acts as a mediator in the pathways involving social networking site use and self-esteem, while coming out status mediates each component of these pathways. The romantic relationship status of LGB individuals is linked to internalized homophobia. Social networking site use and self-esteem act as parallel mediators in their relationship, while gender and coming out status playing a moderating role.

Conclusions

This study sheds light on the intricate factors influencing internalized homophobia among LGB individuals, emphasizing the mediating roles of social networking site usage and self-esteem, along with the moderating effects of gender and coming out status. The findings underscore the importance of fostering inclusive environments that support self-expression and reduce discrimination against LGB individuals. Furthermore, this study suggests directions for future research, including the use of longitudinal designs, the detailed categorization of romantic relationship statuses, and deeper exploration of psychological and behavioral differences across various LGB identities. By addressing these limitations, future studies can offer a more nuanced understanding of internalized homophobia and contribute to the development of effective intervention and prevention strategies for this vulnerable population.

Keywords: LGB, Internalized homophobia, Romantic relationship status, Social networking site use, Self-esteem

Introduction

LGB individuals, as part of the sexual minority group, include homosexuals (lesbians and gay men) and bisexuals [1]. LGB individuals often experience stress related to their sexual orientation due to discrimination, prejudice, and stigmatization of sexual minority groups in society. They generally have poorer mental and sexual health compared to heterosexual individuals and engage in problematic behaviors more frequently [2]. The minority stress model suggests that individuals in sexual minority groups experience significant stress as a result of the stigma attached to their sexual orientation. This stress motivates sexual minorities to adapt to challenging environments, thereby playing a crucial role in shaping differences in their mental health outcomes [3]. Internalized homophobia, the process by which individuals in the LGBTQ + community internalize negative attitudes towards their sexual orientation as part of their self-concept, represents a significant source of stress within sexual minority groups [4]. This is evidenced by low levels of sexual identity acceptance [5]. The negative emotions and behaviors stemming from internalized homophobia can have harmful effects on the mental and physical well-being of LGB individuals. It is recognized as a key factor that can trigger a variety of problematic behaviors [6]. Researches indicate that individuals with elevated levels of internalized homophobia are at a heightened risk for depression, suicidal ideation, substance abuse, and other related concerns [3, 7]. Additionally, they often exhibit reduced levels of subjective well-being, sense of life meaning, and overall life satisfaction, which are considered essential positive psychological resources [5]. Therefore, it is imperative to investigate the mechanisms underlying the formation of internalized homophobia in LGB individuals and to discover effective strategies to mitigate its deleterious effects.

Romantic relationships play a vital role in individual health and are widely regarded as the most impactful social relationship for overall health across the lifespan [8]. The romantic relationship status of LGB individuals is reflected in whether they have a stable same-sex partner. For LGB individuals, same-sex partners can offer emotional support and companionship. Positive romantic experiences can help reduce stress and alleviate psychological distress among sexual minority groups [9]. Nevertheless, entering into romantic relationships with same-sex partners may expose individuals to their sexual orientation, potentially subjecting them to new social pressures and discrimination that can have adverse effects on mental health [10]. This can also exacerbate internalized homophobia. LGB individuals with same-sex partners frequently encounter relationship stigmatization [11] and societal discrimination against same-sex romantic relationships [12–13]. This not only affects their mental health but is also strongly linked to depression and behavioral problems [12]. Studies indicate that entering into romantic relationships can worsen smoking behavior in LGB individuals and elevate drug use in bisexual individuals [14]. Hence, romantic relationship status of LGB individuals may have adverse effects on their mental health and potentially exacerbate internalized homophobia [14–15]. Building on this, this study sets forth hypothesis H1: Individuals in romantic relationships will report significantly higher levels of internalized homophobia than those not in relationships.

With the advancement of the Internet, social networking sites have emerged as a crucial platform for interpersonal communication and interaction [16]. LGB individuals utilize same-sex social networking sites, such as Blued and Grindr to acquire self-relevant knowledge, cultivate social circles, and shape their identities [17], as well as to seek romantic partners [18]. Nonetheless, the utilization of same-sex social networking sites also heightens the chances of LGB individuals contracting sexually transmitted infections [19] and perpetuates societal exclusion towards sexual minorities, as well as stereotypical perceptions of individuals who utilize dating apps [19–20]. Discrimination and stigmatization against sexual minority groups can also be disseminated through these networks, intensifying the pressure on sexual minority individuals and fueling the worsening of internalized homophobia [21–23]. Moreover, LGB individuals are more inclined to seek support from same-sex partners or sexual minority communities when they encounter sexual minority stress [14]. To some degree, same-sex romantic relationships foster group cohesion and social support within LGB individuals [24], offering a feeling of connection and emotional satisfaction [25]. Studies have indicated that romantic relationships can enhance group cohesion [24], thereby increasing the frequency of social networking site use [26]. Building on this, this study sets forth hypothesis H2: Social networking site use will mediate the relationship between romantic relationship status and internalized homophobia.

Self-esteem, regarded as a fundamental component of the personality structure, encompasses an individual’s emotional perception of their self-worth and abilities [27]. Self-esteem serves as a crucial intervention point for improving the psychological well-being of the LGBTQ + community, showing a significant negative correlation with internalized homophobia and serving as a safeguard for the mental state and overall well-being of LGBTQ individuals when confronted with unfavorable external assessments [5]. The sociometer theory proposes that the establishment and preservation of self-esteem are greatly influenced by positive feedback from the external environment, including social acceptance and favorable evaluations within intimate relationships [28]. This suggests that the romantic relationship status of LGB individuals plays a significant role in shaping their self-esteem. Studies have indicated that negative romantic relationships and dating encounters can result in psychological distress, including symptoms of anxiety and depression [29–30]. The incidence of dating violence in same-sex romantic relationships is relatively high [31], posing significant health risks including lowered self-esteem, heightened anxiety, and increased susceptibility to depression. Additionally, such violence can contribute to heightened vulnerability to sexually transmitted infections and an increased likelihood of substance abuse [20]. Furthermore, LGB individuals who encounter shame and discrimination in romantic relationships often face heightened levels of unfair treatment, which can detrimentally affect their self-esteem [32–33] and exacerbate internalized homophobia. Building on this, this study proposes hypothesis H3: Romantic relationships will influence internalized homophobia through the mediating effect of self-esteem, with self-esteem and social networking site use jointly acting as parallel mediators in this process.

Research indicates that among sexual minorities, females tend to experience lower levels of depression within romantic relationships [34]; however, the influence of romantic relationship status on gender differences is not statistically significant [25]. In traditional Chinese beliefs, men are often seen as carrying the primary responsibility for “continuing the family line,” with society placing stricter behavioral expectations on them [35]. Li and Zhao [36] noted that male homosexuals, compared to females, often encounter more negative public attitudes. Consequently, women in sexual minority groups generally possess a stronger self-identification with their sexual identity and orientation than men [37] and tend to face less societal discrimination and lower levels of internalized homophobia [38]. Additionally, specific behavioral patterns among male homosexuals may contribute to an increased risk of HIV transmission [26]. Society tends to associate men’s use of same-sex social networking sites more readily with casual behavior, potentially leading to notable gender differences among LGB individuals in their social networking sites usage. Sexual minorities often face societal condemnation for expressing gender preferences and behaviors that do not align with their biological sex [39], leaving them susceptible to the pressures of gender stereotypes. Donnelly and Twenge [40] found that men tend to experience stronger negative emotions and a decline in self-esteem when confronted with the pressures of gender stereotype. Research also suggests that when individuals defy gender role expectations, men are more likely than women to experience heightened anxiety and reduced self-esteem [41]. Building on this, this study proposes hypothesis H4: The effect of romantic relationship status on internalized homophobia will be moderated by gender, with same-sex social networking site use and self-esteem serving as mediating factors in this relationship. “Coming out” refers to the process by which sexual minorities openly disclose their sexual orientation. Despite societal progress, negative attitudes and biases towards sexual minorities persist, prompting many LGB individuals to choose to conceal their identities to avoid rejection and discrimination [42]. Concealing one’s sexual orientation not only hampers identification and communication within the sexual minority community [43] but also obstructs the formation of intimate relationships. This concealment subjects LGB individuals to dual pressures from both within and outside the community [44], ultimately depleting their psychological resources [45]. Additionally, concealing one’s identity can result in psychological suppression and the harmful impact of stigmatizing beliefs [46], further exacerbating internalized homophobia [9]. Research has shown that LGB individuals who have not come out experience poorer mental and physical health when confronted with stigmatizing experiences [46]. Coming out can foster community integration among sexual minority groups, strengthen a sense of belonging and social support [47], and encourage LGB individuals to engage with same-sex social networking sites more openly. Although coming out can expose individuals to increased discrimination and stigma [48], it also plays a crucial role in strengthening identity among sexual minority groups, enhancing self-esteem, and supporting overall psychological well-being [47]. Research indicates that, compared to individuals who conceal their sexual orientation, lesbian women who are open about their identity report lower level of anxiety and higher self-esteem [49]. Building on this, this study proposes hypothesis H5: The effect of romantic relationship status on internalized homophobia, mediated by same-sex social networking site use and self-esteem, will be moderated by an individual’s coming out status.

In conclusion, this study centers on LGB individuals to explore how varying romantic relationship statuses impact levels of internalized homophobia through the parallel mediating effects of social networking site usage and self-esteem. Additionally, it examines the moderating roles of gender and coming out status, aiming to offer empirical insights and inform intervention strategies to address mental health challenges within the LGB community.

Methods

Participants

The sample size estimation was conducted using the formula N = Z2×[P(1–P)]/E2 [50], where N represents the sample size, Z is the statistical value, E denotes the margin of error, and P is the probability value. For this study, we set Z = 1.96 (corresponding to a 95% confidence level), E = 5%, and P = 80%, based on prior research indicating that approximately 80% of individuals in the LGBT community engage with same-sex social media platforms [38]. Consequently, the required sample size for this study was calculated to be 246 participants.

We utilized online recruitment of lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals through various platforms, including Grindr, Blued, LGBTQ QQ groups, REDnote, and TikTok. To ensure a diverse and representative sample, targeted strategies were implemented beyond just listing platforms. Invitations were worded inclusively and explicitly invited participants from different age groups, ethnic backgrounds, and geographic locations. Specific efforts were made to reach subgroups that are often underrepresented in LGBT research, such as individuals from rural areas or those identifying with multiple marginalized identities. These invitations emphasized the importance of diversity in the study and encouraged participation from a broad range of individuals. In addition, participants must be aged 14 or older and self-identify as homosexual or bisexual [51–52]. A total of 657 valid questionnaires were collected, yielding a response rate of 88.90%. The sample includes 309 males and 348 females; 233 individuals with a stable partner and 424 without; 495 homosexuals and 162 bisexuals. Educational levels are distributed as follows: 194 participants with a college education or below, 385 undergraduates, and 78 with postgraduate education or above. The average age of participants is 22.81 ± 6.15 years.

Ethical considerations were central to the recruitment process. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Anhui Agricultural University, in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were fully informed about the study’s purpose, procedures, and their right to withdraw at any time without consequence. The invitation and consent forms were carefully crafted to ensure clarity and transparency, and were provided in multiple languages to accommodate participants from diverse linguistic backgrounds. All participants provided written informed consent prior to participation. Efforts were made to reduce potential biases inherent in online recruitment by ensuring the platforms used were accessible to individuals from various socio-economic backgrounds and not limited to a specific subgroup within the LGBT community. Data privacy and informed consent were handled in strict accordance with ethical guidelines. Participants were assured that all data would be anonymized and stored securely, with access to the data limited to the research team. Encrypted databases were used, and best practices for data handling were followed. Given the sensitive nature of the study, participants were also informed about the availability of mental health resources should they require support during or after participation.

Materials

Romantic relationship status survey

Following Li et al. [53], this study assesses participants’ romantic relationship status with the question, “Do you have a stable romantic partner or sexual companion?” Participants are asked to indicate whether they currently have a stable romantic partner or sexual companion by marking 1 for “yes” and 0 for “no.”

Internalized Homophobia Scale (IHS)

The scale used in this study was developed by Herek et al. [54] and revised by Li et al. [5]. It consists of 8 items rated on a 5-point scale, with higher scores indicating a greater level of internalized homophobia. For the purposes of this study, the term “male homosexuality” was adjusted to “homosexuality” to ensure inclusivity. The scale demonstrated good internal consistency reliability in this study, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.82.

Social Network Site Intensity Scale (SNSIS)

The scale used in this study was originally developed by Elison et al. [55] and later revised by Niu et al. [56]. It includes 8 items: the first two items assess the number of friends on same-sex social networking sites and the daily usage time on these platforms among LGB individuals. The remaining six items evaluate the emotional connection to and integration of these sites into the lives of LGB individuals. Items are rated on a 5-point scale, with higher scores indicating more intensive social networking site usage. For this study, “social networking sites” was modified to “same-sex social networking sites.” The scale’s internal consistency reliability in this study is 0.87.

Self-Esteem Scale (SES)

The scale employed in this study was developed by Rosenberg [57] and later revised by Tian [58]. It comprises 10 items rated on a 4-point scale, with higher scores reflecting higher levels of self-esteem. In this study, the scale demonstrated an internal consistency reliability of 0.84.

Coming out status survey

Following Li and Zhao [36]’s definition of “coming out,” which entails openly disclosing one’s sexual orientation to at least one family member, colleague, classmate, supervisor, or teacher, this study uses the question “Have you ever disclosed your sexual orientation to others?” to assess participants’ coming out status. Participants are asked to indicate whether they have disclosed their sexual orientation by marking 1 for “yes” and 0 for “no.”

Data processing

In this study, participants were instructed in the questionnaire to respond based on their actual circumstances, with all items marked as mandatory to ensure consistency and accuracy in the data collection process. Following data standardization, the researchers employed Model 4 in SPSS PROCESS 4.1, developed by Hayes [59], to test parallel mediation models. Model 4 is commonly used for examining direct and indirect effects in mediation analysis, especially when investigating the relationships between independent variables, mediators, and dependent variables. This model was chosen due to its robustness in handling simple mediation pathways and its ability to estimate standard errors and confidence intervals using bootstrapping techniques, which strengthens the reliability of the results in small to moderate sample sizes.

For the analysis of moderated mediation models, Amos 24.0 was utilized, which is well-suited for structural equation modeling (SEM). Amos allows for more complex models and can explicitly account for latent variables, making it an ideal tool for exploring how moderation impacts the mediation process. The use of Amos also facilitated testing of model fit indices (e.g., CFI, RMSEA), ensuring the adequacy of the proposed model structure.

An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) without rotation was conducted using the Harman single-factor test on the measured items, as recommended by Tang and Wen [60]. This technique helps identify potential common method bias by examining the factor structure of the data. The results indicated that the first factor accounted for 27.34% of the variance, which is below the commonly accepted threshold of 40%. This suggests that common method bias is not a significant concern in this study and that the data is likely free from this particular source of distortion.

Furthermore, a bootstrap analysis was performed to assess the stability and robustness of the indirect effects in the mediation models. Bootstrap methods are particularly valuable in overcoming the limitations of traditional statistical tests, such as the assumption of normality, by generating empirical distributions of estimates through resampling. This technique enhances the validity of the results, especially in complex models with multiple mediators or moderators. The bootstrap procedure used in this study involved 5,000 resamples to ensure sufficient accuracy in estimating the confidence intervals of the indirect effects.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

The descriptive statistics and correlation analysis for each variable are shown in Table 1. The results reveal significant positive correlations between romantic relationship status and social networking site use, as well as between romantic relationship status and internalized homophobia, alongside a significant negative correlation between romantic relationship status and self-esteem. Furthermore, social networking site use is significantly positively correlated with internalized homophobia and negatively correlated with self-esteem, while internalized homophobia show a significant negative correlation with self-esteem. These findings indicate that the data in this study are appropriate for further analysis.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | ― | ― | ― | |||||||

| 2. Sexual orientation | ― | ― | 0.03 | ― | ||||||

| 3. Educational background | ― | ― | –0.19** | 0.04 | ― | |||||

| 4. Coming out | ― | ― | 0.30** | –0.02 | –0.04 | ― | ||||

| 5. Romantic relationship status | ― | ― | –0.27** | 0.01 | 0.07 | –0.15** | ― | |||

| 6. Internalized homophobia | 2.40 | –0.59** | 0.08 | 0.11** | –0.39** | 0.28** | ― | |||

| 7. Social networking site use | 3.10 | 0.03 | 0.01 | –0.03 | –0.14** | 0.09* | 0.23** | ― | ||

| 8. Self-esteem | 2.76 | 0.13** | –0.09* | 0.13** | 0.16** | –0.15** | –0.28** | –0.14** | ― |

Note: Male = 0, Female = 1; Homosexual = 1, Bisexual = 2; College education or below = 1, Undergraduate = 2, Postgraduate or above = 3; Out = 1, Closed = 0. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, the same below

Parallel mediation analysis

After controlling for sexual orientation, gender, education level, and coming out status, a parallel mediation analysis was conducted using Model 4 in SPSS PROCESS 4.1, as developed by Hayes [59], to examine the parallel mediating effects of social networking site use and self-esteem between romantic relationship status and internalized homophobia. The results (see Table 2) indicated that romantic relationship status significantly positively predicted social networking site use (β = 0.20, p = 0.018) and negatively predicted self-esteem (β=−0.23, p = 0.004). Both romantic relationship status (β = 0.16, p = 0.011) and social networking site use (β = 0.19, p < 0.001) were found to significantly positively predict internalized homophobia, while self-esteem significantly negatively predicted internalized homophobia (β=−0.15, p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Parallel mediation model analysis

| Regression equations | Overall fit indices | Regression coefficients and significance | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variables | Predictor variables | R | R 2 | F | β | 95% CI | t |

| Romantic relationship status | 0.20 | [0.03, 0.36] | 2.38* | ||||

| Sexual orientation | –0.01 | [–0.19, 0.16] | –0.16 | ||||

| Social networking site use | Gender | 0.19 | 0.03 | 4.70 | 0.20 | [0.04, 0.37] | 2.38* |

| Educational background | –0.04 | [–0.16, 0.09] | –0.62 | ||||

| Coming out | –0.40 | [–0.61, − 0.20] | –3.90*** | ||||

| Romantic relationship status | –0.92 | [–0.40, − 0.07] | –2.86** | ||||

| Sexual orientation | –0.23 | [–0.40, − 0.06] | –2.61** | ||||

| Self-esteem | Gender | 0.28 | 0.08 | 10.88 | 0.19 | [0.03, 0.36] | 2.32* |

| Educational background | 0.26 | [0.14, 0.38] | 4.20*** | ||||

| Coming out | 0.30 | [0.10, 0.50] | 2.99** | ||||

| Romantic relationship status | 0.16 | [0.04, 0.28] | 2.55* | ||||

| Social networking site use | 0.19 | [0.13, 0.25] | 6.55*** | ||||

| Self-esteem | –0.15 | [–0.21, − 0.09] | –5.08*** | ||||

| Internalized homophobia | Sexual orientation | 0.70 | 0.48 | 86.89 | 0.17 | [0.04, 0.30] | 2.63** |

| Gender | –1.01 | [–1.13, − 0.89] | –16.08*** | ||||

| Educational background | 0.04 | [–0.06, 0.13] | 0.80 | ||||

| Coming out | –0.45 | [–0.61, − 0.30] | –5.87*** | ||||

The results of the bias-corrected bootstrap tests (see Table 3) show that the 95% confidence intervals for the mediation paths involving social networking site use and self-esteem do not include zero, accounting for 23.75% and 21.88% of the total effect, respectively. These findings indicate that social networking site use and self-esteem partially mediate the relationship between romantic relationship status and internalized homophobia among LGB individuals.

Table 3.

Mediating effects analysis

| Effects | Bootstrap SE | 95% CI | Relative mediation effects | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total mediation effects | 0.073 | 0.023 | 0.029 | ― |

| Social networking site use | 0.038 | 0.018 | 0.006 | 23.75% |

| Self-esteem | 0.035 | 0.014 | 0.010 | 21.88% |

Note: The calculation method for the relative mediation effects value is the absolute value of “mediation path effect / direct effect”

Parallel mediation model of romantic relationship status on internalized homophobia: testing for gender difference

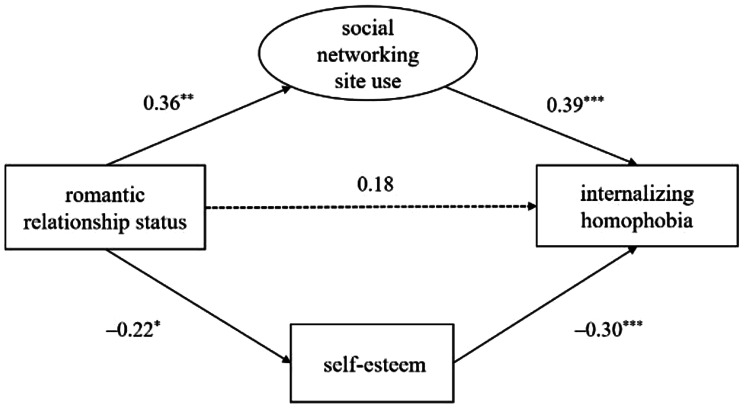

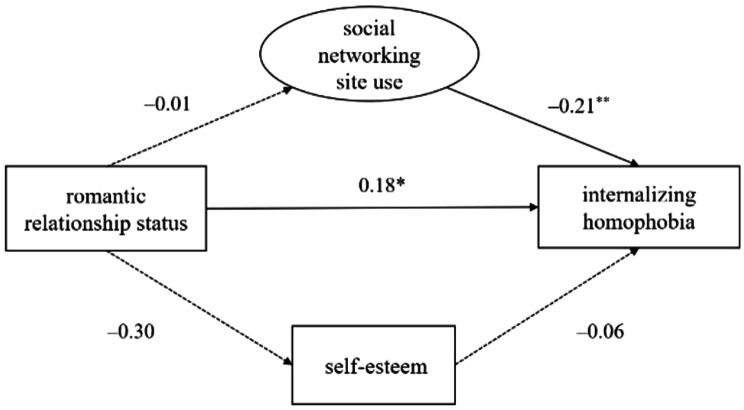

All variables in this study showed significant gender differences: romantic relationship status (males > females, p < 0.001), social networking site use (males < females, p < 0.001), self-esteem (males < females, p < 0.001), and internalized homophobia (males > females, p < 0.001). Accordingly, a multi-group analysis was performed to investigate the moderating effect of gender. Firstly, model fit indices for the male and female samples were examined separately using the bootstrap method. The results indicated good fit indices for both groups, supporting cross-group comparisons (Male: χ2/df = 0.59, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.01, GFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.00; Female: χ2/df = 0.08, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.05, GFI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.00). Based on this, three models were specified: an unconstrained model (M1), a model with equal factor loadings (M2), and a model with equal path coefficients (M3). The results of the cross-group comparisons revealed significant differences between Model M1 and Model M2 (χ2/df = 28.45, p < 0.001), as well as between Model M3 and Model M2 (χ2/df = 7.70, p < 0.001), indicating significant gender differences in the structural model. The unconstrained estimation models for males and females are presented in Figs. 1 and 2, respectively, illustrating the presence of moderated mediation effects in this study.

Fig. 1.

Parallel mediation effect of romantic relationship status on internalized homophobia (male)

Fig. 2.

Parallel mediation effect of romantic relationship status on internalized homophobia (female)

Further examination of gender differences in the mediation effects was conducted using the bootstrap method. The results showed that, for males, social networking site use (95% CI=[0.06, 0.24]) and self-esteem (95% CI=[0.02, 0.13]) fully mediated the relationship between romantic relationship status and internalized homophobia. However, in the female group, this parallel mediation effect was not significant. Following Rong’s (2009) recommendations, difference value critical ratio analysis revealed significant gender differences as follows: romantic relationship status exhibited significant gender differences in predicting social networking site use (CR = − 3.14, p < 0.01), with males (β = 0.36, p = 0.002) showing a significant effect, while females (β=−0.01, p = 0.790) did not. Impact of social networking site use on internalized homophobia showed significant gender differences (CR = − 7.41, p < 0.001), with males (β = 0.39, p < 0.001) having a significantly higher effect than females (β=−0.21, p = 0.002), though in the opposite direction. Effect of self-esteem on internalized homophobia also displayed significant gender differences (CR = − 3.14, p < 0.01), with males (β=−0.30, p < 0.001) showing a significant effect, while females (β=−0.06, p = 0.07) did not. No significant gender differences were observed in the paths from romantic relationship status to self-esteem (CR = − 0.44, absolute value < 1.96) and romantic relationship status to internalized homophobia (CR = 0.69, absolute value < 1.96).

Parallel mediation model of romantic relationship status on internalized homophobia: testing for coming out difference

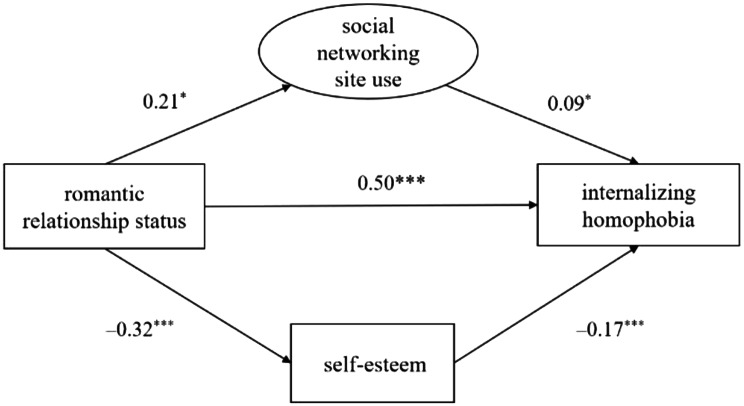

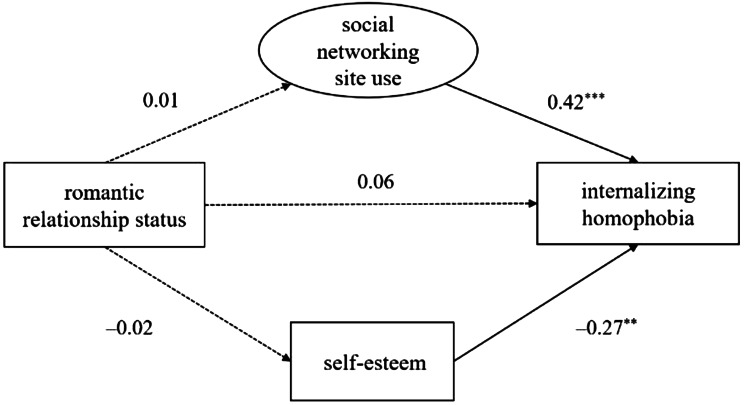

In this study, significant differences were observed between “out” and “closeted” LGB individuals in terms of romantic relationship status (out < closeted, p < 0.001), self-esteem (out > closeted, p < 0.001), and internalized homophobia (out < closeted, p < 0.001). Accordingly, a multi-group analysis was conducted to investigate the moderating effect of being “out”. Firstly, model fit indices for both closeted and out LGB samples were examined separately. The results indicated good fit indices for the out group (χ2/df = 0.85, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, GFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.00) and the closeted group (χ2/df = 0.40, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.03, GFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.01), supporting cross-group comparisons. Accordingly, as mentioned previously, an unconstrained model (M1), a model with equal factor loadings (M2), and a model with equal path coefficients (M3) were specified. The cross-group comparison results are as follows: significant differences were found between Model M1 and Model M2 (χ2/df = 10.97, p < 0.001) and between Model M3 and Model M2 (χ2/df = 3.65, p = 0.006), further confirming structural model differences associated with being “out”. The unconstrained estimation models for the “out” LGB group (Fig. 3) and the closeted LGB group (Fig. 4) reveal notable differences, verifying the moderated mediation effects in this study.

Fig. 3.

Parallel mediation effect of romantic relationship status on internalized homophobia (male)

Fig. 4.

Parallel mediation effect of romantic relationship status on internalized homophobia (female)

Further examination of mediation effect differences based on being “out” was conducted using the bootstrap method. The results showed that, for the “out” LGB group, social networking site use (95% CI=[0.01, 0.06]) and self-esteem (95% CI=[0.03, 0.10]) both served as partial mediators, jointly functioning as parallel mediators. However, this parallel mediation effect was not significant in the closeted LGB group, indicating that being “out” moderates the mediation effects.

The difference value critical ratio analysis revealed significant differences in the impact of romantic relationship status on self-esteem based on being “out” (CR = − 1.98, p < 0.05). For “out” LGB individuals, romantic relationship status significantly predicted self-esteem (β=−0.32, p < 0.001), whereas for closeted LGB individuals, this relationship was not significant (β=−0.02, p = 0.90). Similarly, significant differences were observed in the impact of romantic relationship status on internalized homophobia based on being “out” (CR = 3.00, p < 0.01). For “out” LGB individuals, romantic relationship status significantly predicted internalized homophobia (β = 0.50, p < 0.001), whereas for closeted LGB individuals, this relationship was not significant (β = 0.06, p = 0.630). Additionally, the influence of social networking site use on internalized homophobia showed significant differences based on being “out” (CR = − 3.67, p < 0.001). For closeted LGB individuals, the predictive effect of social networking site use on internalized homophobia (β = 0.42, p < 0.001) was significantly stronger than for “out” LGB individuals (β = 0.09, p = 0.032). However, the predictive paths from romantic relationship status to social networking site use (CR = 1.27, absolute value < 1.96) and from self-esteem to internalized homophobia (CR = 1.00, absolute value < 1.96) did not show significant differences based on being “out”.

Discussion

This study identified a significant positive correlation between romantic relationship status and internalized homophobia among LGB individuals, providing support for hypothesis H1. The results suggest that LGB individuals with a committed partner or sexual companion tend to exhibit higher levels of internalized homophobia. This finding diverges from previous research [24], potentially due to the broader sample in this study, which included both lesbian and bisexual populations. The findings suggest that LGB individuals with committed partners often encounter heightened social discrimination, pressure, and stigmatization of same-sex relationships [11], which can lead to increased levels of minority stress and internalized homophobia [9]. Compared to heterosexual individuals, LGB individuals may experience higher levels of depression and anxiety within same-sex relationships [30], suggesting that romantic relationships may not effectively alleviate mental health challenges. Instead, they may amplify negative emotions, further intensifying internalized homophobia.

Research findings reveal that the romantic relationship status partially mediates internalized homophobia through the use of same-sex social networking sites, supporting hypothesis H2. This suggests that social networking sites play a crucial role between romantic involvement and internalized homophobia: for individuals with a committed partner or sexual companion, reducing the use of same-sex social media platforms may help alleviate internalized homophobia. The rise of the internet has transformed same-sex social networking sites into spaces where sexual minorities can exchange information, engage in self-exploration, and construct their identities [17], while also offering LGB individuals a platform for seeking intimate relationships [61]. Engaging with same-sex social networking sites can enhance self-identity [62] but may also increase vulnerability to stigmatization [63]. For sexual minority groups, excessive group identification can heighten feelings of exclusion and stigmatization [64], potentially intensifying internalized homophobia [65]. While forming intimate relationships within the LGB community can strengthen a sense of identity and belonging [24–25], it may also increase vulnerability to sexual minority stress [63].

Research indicates that romantic relationship status partially mediates internalized homophobia through self-esteem, with self-esteem and the use of same-sex social networking sites jointly serving as parallel mediators, thereby supporting hypothesis H3. This finding aligns with previous studies [24, 28]. Individuals with low self-esteem, being more sensitive to external judgments, are more likely to internalize societal biases and evaluations into their self-concept, thereby intensifying their level of internalized homophobia [54]. According to the sociometer theory, the formation of self-esteem is closely tied to positive evaluations stemming from social acceptance and intimate relationships [66]. However, LGB individuals are more prone to experience dating violence in romantic relationships [31] and often perceive greater relationship stigmatization [11], which can lead to reduced self-esteem. This suggests that remaining single may help LGB individuals avoid the societal stigmatization associated with same-sex relationships, thereby potentially reducing internalized homophobia.

This study found that gender significantly moderates the predictive effects of romantic relationship status on social networking site usage, the effects of social networking site usage on internalized homophobia, and the effects of self-esteem on internalized homophobia, supporting hypothesis H4. Specifically, the positive predictive effect of romantic relationship status on same-sex social networking site usage is more pronounced in males, whereas in females, the predictive direction is opposite and less defined. This may be attributed to the stricter societal expectations placed on male homosexuals [36]. Male homosexuals and bisexual individuals face a heightened risk of marginalization [22], which may increase their desire for partner recognition and seeking validation, often sought through same-sex social networking sites [67]. Positive same-sex relationships can offer emotional support for LGB individuals [25], foster group cohesion [24], and encourage increased use of same-sex social networking sites. Furthermore, among men, higher intensity of same-sex social networking site usage is associated with deeper levels of internalized homophobia, whereas for women, this relationship is reversed. Male homosexual and bisexual individuals face higher risks of infectious diseases and are more often labeled as “promiscuous” [19, 26]. Combined with a greater susceptibility to derogatory language within the community [68], these factors contribute to elevated levels of internalized homophobia. Lastly, the negative predictive effect of self-esteem on internalized homophobia is more pronounced in males, suggesting that when male homosexuals experience greater pressure, the protective effect of positive mental health resources becomes more significant [25]. This underscores the differences in public attitudes toward LGB individuals of different genders in traditional societies.

This study found that being “out of the closet” significantly moderates the effects of romantic relationship status on internalized homophobia, the effects of romantic relationship status on self-esteem, and the predictive effects of social networking site usage on internalized homophobia, supporting hypothesis H5. Specifically, the positive predictive effect of romantic relationship status on internalized homophobia is more pronounced in LGB individuals who are out, whereas this effect is less evident for those who are not out. Out individuals typically possess a stronger sense of group and sexual identity [47], which can make them more vulnerable to the effects of negative stigmatization [63], thereby increasing internalized homophobia. Additionally, the negative predictive effect of romantic relationship status on self-esteem is more pronounced in out individuals. This may stem from the fact that coming out and forming relationships with same-sex partners encourage LGB individuals to integrate into the community, share stigmatized experiences, and heighten awareness of social injustices, which can, in turn, reduce self-esteem [32]. Furthermore, the positive predictive effect of social media activity on internalized homophobia is stronger for individuals who are not out than for those who are. Individuals who are not out often experience pressure and psychological burdens related to the prospect of coming out when using online resources, which can intensify their internalized homophobia [47]. While coming out may introduce additional pressures, out individuals typically have more positive psychological resources to cope with rejection and to form clearer self-concepts [69]. In contrast, concealing one’s sexual orientation can foster feelings of self-rejection and discomfort, thereby increasing internalized homophobia [70].

The main theoretical contributions of this study are as follows: First, this study not only identified romantic relationship status as an influencing factor but also highlighted the mediating roles of social networking site usage and self-esteem, offering a fresh perspective on the mechanisms underlying internalized homophobia. Second, the study explored the moderating effects of gender and coming out status within this framework, deepening our understanding of the complex formation of internalized homophobia within the LGB community. In terms of practical implications, this study provides valuable guidance for addressing and preventing psychological challenges among LGB individuals. To foster an inclusive environment, schools, families, society, and online communities must strive to create greater equality for LGB individuals, reduce discrimination and stigmatization, and promote opportunities for openly expressing sexual orientation. By enhancing self-esteem and mental health support, these measures can help mitigate internalized homophobia. This is especially pertinent for men, who, influenced by traditional Chinese values and Confucian culture, face heightened expectations around “carrying on the family line.” This societal pressure makes male LGB individuals particularly vulnerable to internalizing negative societal attitudes, leading to adverse psychological effects. To combat this, society should work to reduce the spread of negative information about LGB individuals online and support efforts to bolster their self-esteem. Furthermore, the societal environment places unique pressures on LGB individuals, where romantic relationships and coming out can sometimes intensify internalized homophobia. This highlights the importance of cultivating an accepting environment that encourages LGB individuals to express themselves freely, while offering social support and respect to help reduce internalized homophobia.

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, the use of a cross-sectional research design limits the ability to draw causal inferences about the relationships between variables. Although the associations identified in this study provide valuable insights, they do not establish directionality. Future studies could employ longitudinal designs to more accurately examine how these relationships evolve over time and the developmental dynamics of internalized homophobia within different contexts. Second, this study did not differentiate between various romantic relationship statuses (e.g., heterosexual relationship, same-sex relationship, dating, cohabitation, marriage), which may have distinct effects on internalized homophobia. Future research could address this limitation by categorizing relationship statuses more precisely, allowing for a deeper understanding of how different relationship types impact internalized homophobia among LGB individuals. Additionally, the study did not consider the role of different LGB subgroups in the relationship between romantic relationship status and internalized homophobia. It would be valuable to explore psychological and behavioral differences among individuals with varying sexual orientations (e.g., gay, lesbian, bisexual) and gender role preferences within the LGB community. Such differentiation could yield more nuanced insights into how internalized homophobia manifests differently across subgroups. Further, the implications of these findings for interventions to reduce internalized homophobia should be addressed. Given that romantic relationships and self-esteem play crucial roles in shaping internalized homophobia, interventions could focus on enhancing self-esteem and promoting supportive romantic relationships within the LGB community. It would also be beneficial to develop programs that specifically target individuals experiencing internalized homophobia due to social media exposure or societal rejection. Finally, future research should incorporate qualitative approaches, such as in-depth interviews, to explore the lived experiences of participants. This would provide richer insights into the psychological mechanisms underlying internalized homophobia and help refine intervention strategies tailored to the diverse needs of LGB individuals.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study sheds light on the intricate factors influencing internalized homophobia among LGB individuals, emphasizing the mediating roles of social networking site usage and self-esteem, along with the moderating effects of gender and coming out status. The findings underscore the importance of fostering inclusive environments that support self-expression and reduce discrimination against LGB individuals. Furthermore, this study suggests directions for future research, including the use of longitudinal designs, the detailed categorization of romantic relationship statuses, and deeper exploration of psychological and behavioral differences across various LGB identities. By addressing these limitations, future studies can offer a more nuanced understanding of internalized homophobia and contribute to the development of effective intervention and prevention strategies for this vulnerable population.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants for their collaboration.

Author contributions

Study design: Shen Liu, Minghua Song, Na Zhang. Data collection, analysis and interpretation: Nirui Yu. Drafting the manuscript: Nirui Yu, Kexin Chen, Minghua Song, Na Zhang, Shen Liu. Critical revision of the manuscript: Nirui Yu, Kexin Chen, Minghua Song, Na Zhang, Shen Liu. Approval of the final version for publication: all co-authors.

Funding

SL was supported by the Research Project of Humanities and Social Sciences of the Ministry of Education (24YJC190018), the Outstanding Youth Program of Philosophy and Social Sciences in Anhui Province (2022AH030089), and the Starting Fund for Scientific Research of High-Level Talents at Anhui Agricultural University (rc432206).

Data availability

Data and materials are available on request from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethics committee of Anhui Agricultural University approved the study protocol. Participants signed an informed consent form before beginning the research. The study’s objectives, confidentiality, and anonymity were described, and volunteers were given full authority to complete the questionnaire. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Minghua Song, Email: 1443081434@qq.com.

Na Zhang, Email: zhangna@ahjgxy.edu.cn.

Shen Liu, Email: liushen@ahau.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Martos A, Nezhad S, Meyer IH. Variations in sexual identity milestones among lesbians, gay men and bisexuals. Sex Res Soc Policy. 2015;12(1):24–33. 10.1007/s13178-014-0167-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rogers AH, Seager I, Haines N, Hahn H, Aldao A, Ahn WY. The indirect effect of emotion regulation on minority stress and problematic substance use in lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Front Psychol. 2017;8:1881. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hatzenbuehler ML. How does sexual minority stigma get under the skin? A psychological mediation framework. Psychol Bull. 2009;135(5):707–30. 10.1037/a0016441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(5):674–97. 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li F, Zheng X, Mai XH, Wu JF, Wang YB. Internalized homophobia and subjective well-being among young gay men: the mediating effect of delf-esteem and loneliness. J Psychol Sci. 2014;37(5):1204–11. 10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.2014.05.025. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Denton FN, Rostosky SS, Danner F. Stigma-related stressors, coping self-efficacy, and physical health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. J Couns Psychol. 2014;61(3):383–91. 10.1037/a0036707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mongelli F, Perrone D, Balducci J, Sacchetti A, Ferrari S, Mattei G, Galeazzi GM. Minority stress and mental health among LGBT populations: an update on the evidence. Minerva Psich. 2019;60(1):27–50. 10.23736/S0391-1772.18.01995-7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Umberson D, Crosnoe R, Reczek C. Social relationships and health behavior across the life course. Annu Rev Sociol. 2010;36:139–57. 10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-120011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rostosky SS, Riggle ED. Same-sex relationships and minority stress. Curr Opin Psychol. 2017;13:29–38. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsu J, Mernitz S. The role of romantic relationships for sexual minority young adults’ depressive symptoms: does relationship type matter? Soc Sci Res. 2024;122:10449. 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2024.103049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenthal L, Starks TJ. Relationship stigma and relationship outcomes in interracial and same-sex relationships: examination of sources and buffers. J Fam Psychol. 2015;29(6):818–30. 10.1037/fam0000116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.LeBlanc AJ, Frost DM. Couple-level minority stress and mental health among people in same-sex relationships: extending minority stress theory. Soc Ment Health. 2020;10(3):276–90. 10.1177/2156869319884724. [Google Scholar]

- 13.LeBlanc AJ, Frost DM, Wight RG. Minority stress and stress proliferation among same-sex and other marginalized couples. J Marriage Fam. 2015;77(1):40–59. 10.1111/jomf.12160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whitton SW, Dyar C, Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Effects of romantic involvement on substance use among young sexual and gender minorities. Drug Alcohol Depen. 2018;191:215–22. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsieh N, Liu H. Social relationships and loneliness in late adulthood: disparities by sexual orientation. J Marriage Fam. 2021;83(1):57–74. 10.1111/jomf.12681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gosling SD, Mason W. Internet research in psychology. Annu Rev Psychol. 2015;66:877–902. 10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deters FG, Mehl MR. Does posting Facebook status updates increase or decrease loneliness? An online social networking experiment. Soc Psychol Pers Sci. 2013;4(5):579–86. 10.1177/1948550612469233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goedel WC, Duncan DT. Geosocial-networking app usage patterns of gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men: survey among users of grindr, a mobile dating app. JMIR Public Hlth Sur. 2015;1(1):e4. 10.2196/publichealth.4353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cao B, Liu C, Stein G, Tang W, Best J, Zhang Y, Yang B, Huang SJ, Wei CY, Tucker JD. Faster and riskier? Online context of sex seeking among men who have sex with men in China. Sex Transm Dis. 2017;44(4):239–44. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Costa ECV, Gomes SC. Social support and self-esteem moderate the relation between intimate partner violence and depression and anxiety symptoms among Portuguese women. J Fam Violence. 2018;33(5):355–68. 10.1007/s10896-018-9962-7. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blackwell C, Birnholtz J, Abbott C. Seeing and being seen: Co-situation and impression formation using grindr, a location-aware gay dating app. New Media Soc. 2014;17(7):1117–36. 10.1177/1461444814521595. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cao B, Smith K. Gay dating apps in China: do they alleviate or exacerbate loneliness? The serial mediation effect of perceived and internalized sexuality stigma. J Homosexual. 2023;70(2):347–63. 10.1080/00918369.2021.1984751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen L, Shi J. Social support exchanges in a social media community for people living with HIV/AIDS in China. AIDS Care. 2015;27(6):693–6. 10.1080/09540121.2014.991678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li F, Wang YB, Zhong LP. Gay community connectedness, romantic relationship status and internalized homonegativity among gay men: A moderated mediation effect. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2023;31(5):1080–4. 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2023.05.011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baams L, Bos HMW, Jonas KJ. How a romantic relationship can protect same-sex attracted youth and young adults from the impact of expected rejection. J Adolescence. 2014;37(8):1293–302. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Castro Á, Barrada JR, Ramos-Villagrasa PJ, Fernández-Del-Río E. Profiling dating apps users: sociodemographic and personality characteristics. Int J Env Res Pub He. 2020;17(10):1–13. 10.3390/ijerph17103653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Orth U, Robins RW. The development of self-esteem. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2014;23(5):381–7. 10.1177/0963721414547414. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murray SL, Griffin DW, Rose P, Bellavia GM. Calibrating the sociometer: the relational contingencies of self-esteem. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;85(1):63–84. 10.1037/0022-3514.85.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.La Greca AM, Harrison HM. Adolescent peer relations, friendships, and romantic relationships: do they predict social anxiety and depression? J Clin Child Adolesc. 2005;34(1):49–61. 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Russell ST, Consolacion TB. Adolescent romance and emotional health in the united States: beyond binaries. J Clin Child Adolesc. 2003;32(4):499–508. 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3204_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davis LS, Crain EE. Intimate partner violence in the LGBTQ + community: implications for family court professionals. Fam Court Rev. 2024;62(1):45–67. 10.1111/fcre.12765. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lakey B, Orehek E. Relational regulation theory: A new approach to explain the link between perceived social support and mental health. Psychol Rev. 2011;118(3):482–95. 10.1037/a0023477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rostosky SS, Riggle EDB, Gray BE, Hatton RL. Minority stress experiences in committed same-sex couple relationships. Prof Psychol-Res Pr. 2007;38(4):392–400. 10.1037/0735-7028.38.4.392. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whitton SW, Dyar C, Godfrey LM, Newcomb ME. Within-person associations between romantic involvement and mental health among sexual and gender minorities assigned female-at-birth. J Fam Psychol. 2021;35(5):606–17. 10.1037/fam0000835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kite ME, Whitley BEJ. Sex differences in attitudes toward homosexual persons, behaviors, and civil rights: A meta-analysis. Pers Soc Psychol B. 1996;22(4):336–53. 10.1177/0146167296224002. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li LM, Zhao BH. Perceived public attitude and loneliness in the homosexuals: moderating of coming out condition. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2015;23(5):911–4. 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2015.05.035. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J, Braun L. Sexual identity development among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths: consistency and change over time. J Sex Res. 2006;43(1):46–58. 10.1080/00224490609552298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chan RCH, Leung JSY. Monosexism as an additional dimension of minority stress affecting mental health among bisexual and pansexual individuals in Hong Kong: the role of gender and sexual identity integration. J Sex Res. 2022;60(5):704–17. 10.1080/00224499.2022.2119546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rudman LA, Moss-Racusin CA, Glick P, Phelan JE. Reactions to vanguards: advances in backlash theory. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 2012;45:167–227. 10.1016/B978-0-12-394286-9.00004-4. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Donnelly K, Twenge JM. Masculine and feminine traits on the bem sex-role inventory, 1993– 2012: A cross-temporal meta-analysis. Sex Roles. 2017;76(9–10):556–65. 10.1007/s11199-016-0625-y. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rudman LA, Dohn MC, Fairchild K. Implicit self-esteem compensation: automatic threat defense. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;93(5):798–813. 10.1037/0022-3514.93.5.798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pachankis JE, Goldfried MR. Social anxiety in young gay men. J Anxiety Disord. 2006;20(8):996–1015. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang J, Zheng LJ, Zheng Y. The mental health of sexual minorities: theoretical models and research orientations. Adv Psychol Sci. 2015;23(6):1021–30. 10.3724/SP.J.1042.2015.01021. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Herek GM, Capitanio JP, Widaman KF. Stigma, social risk, and health policy: public attitudes toward HIV surveillance policies and the social construction of illness. Health Psychol. 2003;22(5):533–40. 10.1037/0278-6133.22.5.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Riggle EDB, Rostosky SS, Black WW, Rosenkrantz DE. Outness, concealment, and authenticity: associations with LGB individuals’ psychological distress and well-being. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2017;4(1):54–62. 10.1037/sgd0000202. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Camacho G, Reinka MA, Quinn DM. Disclosure and concealment of stigmatized identities. Curr Opin Psychol. 2020;31:28–32. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Suppes A, van der Toorn J, Begeny CT. Unhealthy closets, discriminatory dwellings: the mental health benefits and costs of being open about one’s sexual minority status. Soc Sci Med. 2021;285:114286. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bahamondes J, Sibley CG, Osborne D. We look (and feel) better through system-justifying lenses: system-justifying beliefs attenuate the well-being gap between the advantaged and disadvantaged by reducing perceptions of discrimination. Pers Soc Psychol B. 2019;45(9):1391–408. 10.1177/0146167219829178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jordan KM, Deluty RH. Coming out for lesbian women: its relation to anxiety, positive affectivity, self-esteem, and social support. J Homosexual. 1998;35(2):41–63. 10.1300/J082v35n02_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huang YQ. Random error control and sample size determination in medical research. Chin Mental Health J. 2015;29(11):874–80. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Calzo JP, Masyn KE, Austin SB, Jun HJ, Corliss HL. Developmental latent patterns of identification as mostly heterosexual versus lesbian, gay, or bisexual. J Res Adolescence. 2017;27(1):246–53. 10.1111/jora.12266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meyer IH, Wilson PA. Sampling lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. J Couns Psychol. 2009;56(1):23–31. 10.1037/a0014587. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li F, Huang LJ, Zhong LP, Wang YB, Xing JT, Zheng X. State of romantic relationship and life satisfaction among gay men: A chain mediation model. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2019;27(4):785–9. 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2019.04.030. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Herek GM, Cogan JC, Gillis JR, Glunt EK. Correlates of internalized homophobia in a community sample of lesbians and gay men. J Gay Lesbian Med Association. 1998;2(1):17–26. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ellison NB, Steinfield C, Lampe C. The benefits of Facebook friends: social capital and college students’ use of online social network Sies. J Comput-Mediat Comm. 2007;12(4):1143–68. 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00367.x. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Niu GF, Sun XJ, Zhou ZK, Kong FC, Tian Y. The impact of social network site (Qzone) on adolescents’ depression: the serial mediation of upward social comparison and self-esteem. Acta Physiol Sinica. 2016;48(10):1282–91. 10.3724/SP.J.1041.2016.01282. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tian LM. Shortcoming and merits of Chinese version of Rosenberg (1965) self-esteem scale. Psychol Explor. 2006;26(2):88–91. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tang DD, Wen ZL. Statistical approaches for testing common method bias: problems and suggestions. J Psychol Sci. 2020;43(1):215–23. 10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.20200130. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kosenko KA, Bond BJ, Hurley RJ. An exploration into the uses and gratifications of media for transgender individuals. Psychol Pop Media Cu. 2018;7(3):274–88. 10.1037/ppm0000135. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gabriel J, Castañeda M. Grindring the self: young Filipino gay Men’s exploration of sexual identity through a geo-social networking application. Philippine J Psychol. 2015;48(1):29–58. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Herek G, Gillis J, Cogan J. Internalized stigma among sexual minority adults: insights from a social psychological perspective. J Couns Psychol. 2009;56(1):32–43. 10.1037/a0014672. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Crabtree JW, Haslam SA, Postmes T, Haslam C. Mental health support groups, stigma, and self-esteem: positive and negative implications of group identification. J Soc Issues. 2010;66(3):553–69. 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2010.01662.x. [Google Scholar]

- 65.White HJM, Pachankis JE, Eldahan AI, Keene DE. You can’t just walk down the street and Meet someone: the intersection of social-sexual networking technology, stigma, and health among gay and bisexual men in the small City. Am J Men’s Health. 2017;11(3):726–36. 10.1177/1557988316679563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Leary MR, Baumeister RF. The nature and function of self-esteem: sociometer theory. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology, Vol. 32. Academic Press, 2000. pp. 1–62. 10.1016/S0065-2601(00)80003-9

- 67.Baams L, Jonas KJ, Utz S, Bos HMW, van der Vuurst L. Internet use and online social support among same sex attracted individuals of different ages. Comput Hum Behav. 2011;27(5):1820–7. 10.1016/j.chb.2011.04.002. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang S. Calculating dating goals: data gaming and algorithmic sociality on blued, a Chinese gay dating app. Inf Commun Soc. 2020;23(2):181–97. 10.1080/1369118X.2018.1490796. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bos HMW, Sandfort TGM, Bruyn EH, Hakvoort EM. Same-Sex attraction, social relationships, psychosocial functioning, and school performance in early adolescence. Dev Psychol. 2008;44(1):59–68. 10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhao JY, Zhang B, Yu G. Effects of concealable stigma for learning disabilities. Soc Behav Personal. 2008;36(9):1179–88. 10.2224/sbp.2008.36.9.1179. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data and materials are available on request from the corresponding author.