Abstract

Purple sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) are known to have bioactive anthocyanin compounds with numerous human therapeutic benefits. Anthocyanins derived from I. batatas can suppress the action of Transforming Growth Factor beta Type II Receptor (TGFβRII) to prevent fibrosis progression. This study aims to examine the molecular features and bioactivity of anthocyanins in I. batatas and determine the interaction of six anthocyanins in I. batatas against TGFβRII through in silico studies. The TGFβRII protein was retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) database, while the I. batatas anthocyanin was acquired from the PubChem database. Proteins and ligands were docked utilizing the PyRx 0.8 and visualized by Discovery Studio 4.1 software. The in silico study results indicated peonidin-3-glucoside, pelargonidin-3-glucoside, cyanidin 3-o-galactoside, delphinidin 3-glucoside, peonidin 3-galactoside and, cyanidin 3-glucoside were revealed to be efficacious against TGFβRII. Analysis of protein–ligand interactions demonstrates that anthocyanins bind to amino acid residues in the target protein’s active site, and these anthocyanins have higher binding energy than the reference drug. I. batatas, one of the traditional medicinal plants containing anthocyanins, has the potential to generate effective therapeutic approaches for the treatment of fibrosis. Additional in-vitro and in-vivo research is highly recommended to comprehend the antifibrosis mechanism adequately.

Keywords: Anthocyanin, Antifibrosis, Ipomoea batatas, TGFβRII

Introduction

Fibrosis is scar tissue that arises due to a chronic inflammatory process triggered by persistent infections, autoimmune reactions, allergic responses, radiation, and tissue injury [1]. Fibrosis is one of the primary causes of mortality and morbidity on a global scale. Viral hepatitis, chronic kidney disease (CKD), nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), cystic fibrosis, and pneumoconiosis are common diseases associated with fibrosis [2]. The annual incidence of fibrosis-related diseases is approximately 4,968 per 100,000 person-years [3]. In 2019, fibrosis-related diseases contributed significantly to disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) [4].

The initiation of fibrosis involves the production of cytokines by inflammatory cells [5], which triggers fibroblasts [6], induces proliferation and differentiation of fibroblasts [7], and protein profibrotic transforming growth factor (TGFβ), which causes excessive synthesis of extracellular matrix (ECM) and triggers the formation of fibrosis [6,8]. TGFβ cytokines signal through the transmembrane receptors TGFβRI and TGFβRII which are receptor protein serine/threonine kinases.[9].

A ligand-receptor complex is produced when TGFβ binds to TGFβRII. TGFβRI will be phosphorylated and activated by TGFβRII receptor kinase following creation of TGFβRI and TGFβRII complexes in response to ligand-receptor interaction. The TGFβ will subsequently become active and induce fibrosis through Smad signaling (canonical pathway) [10] and Smad Independent signaling (non canonical pathway). In the canonical pathway, active TGFβ will bind to TGFβRII, which causes TGFβRI phosphorylation [11]. R-Smads detach from TGFβR1 and form a heterotrimeric complex with TGFBRII and Co-Smad on the endosome then translocated into the nucleus upon activation of TGFβR1. The Smad complex will interact with transcription factors which will then bind to target genes for control of transcription at the genomic level and generate fibrosis [12]. TGFβ signaling also emerges through non-canonical pathways [13]. This pathway involves Erk/MAPK signaling and also Protein kinase B (Akt) via phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3K), leading to fibrosis [12].

Fibrosis is considered a critical health challenge in the global community. There are currently few curative treatments for fibrosis. One of the fibrosis drugs registered by the food and drug administration (FDA) is pirfenidone. Pirfenidone works as an antifibrosis agent by reducing the synthesis and activation of TGFβ [2]. However, long-term usage of pirfenidone has numerous side effects, including gastrointestinal disorders (nausea, dyspepsia, vomiting, anorexia) [14] and skin (rash, photosensitivity) [15], necessitating the employment of alternate therapeutic approachs. In experimental animal models of fibrosis, alternative therapies with anthocyanin compounds from various plant sources are known to suppress the fibrosis process [16]. In Otunctemur’s study, anthocyanins from pomegranate extract 100/L for 14 days could prevent fibrosis progression by lowering oxidative stress [17]. Studies conducted by Laorodphun also showed that anthocyanins from the 200 mg/kg black rice fraction could improve organ morphology and function [18].

Anthocyanins are secondary metabolites, flavonoids with a structure consisting of two aromatic rings separated by a heterocyclic ring with oxygen cations. Naturally, anthocyanins are found as glycosides [19]. The main anthocyanins in plants are delphinidin, cyanidin, malvidin, pelargonidin, peonidin, and petunidin [20]. Anthocyanin is the main functional compound of purple sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas). Specific anthocyanins have been extracted and identified from purple sweet potato, including peonidin-3-glucoside, pelargonidin-3-glucoside, cyanidin 3-o-galactoside, delphinidin 3-glucoside, peonidin 3-galactoside, cyanidin 3-glucoside, and peonidin 3-galactoside. Purple sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) is known to contain anthocyanins which function as antioxidants [21,22] and anti-inflammatories [23,24].

Purple sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) is based on its substantial anthocyanin content, demonstrating remarkable bioactive potential in fibrosis-related research. Anthocyanins sourced from diverse plants, including purple sweet potato, are acknowledged for their antioxidant [21,22], anti-inflammatory [21,22], and renoprotective properties [17], particularly relevant to the essential mechanisms of fibrosis, such as oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, and tissue injury. Although previous studies have highlighted the antifibrotic potential of anthocyanins from sources such as black rice [18] and pomegranate [17], the specific anthocyanins found in purple sweet potato remain underexplored in the context of fibrosis, given their documented pharmacological benefits and the potential to modulate critical fibrotic pathways, including TGFβ signaling, the anthocyanins from purple sweet potato merit further investigation as promising candidates for antifibrotic therapy.

Developing a chemical into a standard therapeutic agent, such as an antifibrotic treatment, generally requires 15 to 25 years and involves significant expenses. This requires the application of drug discovery approaches that can expedite the identification and assessment of candidate compounds, thereby reducing both time and expense [25]. Computational in silico approaches offer an efficient and cost-effective alternative to conventional drug development methods by enabling the rapid prediction and evaluation of compounds’ biological activity.

This study aims to investigate the inhibitory potential of anthocyanins on TGFβRII, an essential receptor in the TGFβ signaling pathway implicated in fibrosis, using in silico methodologies, including virtual screening, ADME analysis, and molecular docking simulations. These approaches provide preliminary insights into the mechanism of action and pharmacological potential of purple sweet potato anthocyanins, laying the groundwork for future in vitro and in vivo validation.

Materials and methods

Protein preparation

The three-dimensional structure of the Transforming Growth Factor Beta Receptor II (TGFβRII) protein (Protein Data Bank ID: 7DV6) was obtained from the Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics Protein Data Bank (RCSB PDB) with a resolution of 2.39 Å. Prior to molecular docking analysis, the structure was prepared by removing all water molecules using PyMOL version 2.5.4 to eliminate unnecessary interactions during docking. The cleaned protein structure was saved in PDBQT format using AutoDock Tools, which prepared the receptor for docking simulations by assigning appropriate atom types and adding polar hydrogens. Pirfenidone (CID: 40632) was selected as a reference ligand because of its recognized function as a TGFβRII inhibitor in antifibrotic therapy.

Ligand preparation

The anthocyanin compounds from purple sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) were selected based on their relevance to fibrosis-related research. Six anthocyanin derivatives, including peonidin-3-glucoside, pelargonidin-3-glucoside, cyanidin 3-O-galactoside, delphinidin 3-glucoside, peonidin 3-galactoside, and cyanidin 3-glucoside, were retrieved from the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) in SDF 3D file format.The energy minimization of all ligands, including the control compound (pirfenidone), was performed using the Open Babel tool integrated into PyRx version 0.8 to optimize their geometry for docking. The minimized structures were then converted into PDBQT format, compatible with the AutoDock Vina engine embedded in PyRx.

Molecular docking analysis

Molecular docking analysis was conducted using PyRx version 0.8, which utilizes the AutoDock Vina scoring algorithm. The docking study focused on evaluating the binding interactions of anthocyanins with TGFβRII. Docking Parameters: Grid Box Center: The docking grid was centered at x: 14.1554, y: −2.2594, z: 5.8492. Grid Dimensions: x: 18.4462 Å, y: 13.3944 Å, z: 18.9721 Å. Scoring Function: AutoDock Vina’s scoring action was used to estimate the binding affinity between the ligands and the receptor, which was reported in kcal/mol.

Post-Docking Analysis: The docking results, including binding affinity values and receptor-ligand interactions, were analyzed using BIOVIA Discovery Studio version 4.1 (https://3dsbiovia.com/products/).). This software facilitated the visualization of fundamental interactions, such as hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions, and van der Waals forces.

ADMET analysis

ADMET analysis was conducted to evaluate the pharmacokinetic and toxicological properties of anthocyanins as potential drug candidates.

SwissADME (http://www.swissadme.ch) was utilized to predict physicochemical properties [molecular weight, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, topological polar surface area (TPSA), and the number of rotatable bonds (NRB)], lipophilicity (Log Po/w using iLOGP, XLOGP3, WLOGP, MLOGP, SILICOS-IT), water solubility (Log S via ESOL, Ali, SILICOS-IT), pharmacokinetics [Gastrointestinal absorption (GIA), blood–brain barrier (BBB) permeability, P-glycoprotein (P-gp) substrate, and cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzyme inhibition)], and drug-likeness (Lipinski and Ghose). SwissADME platform, a computational platform developed and operated by the SIB Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics. The platform utilizes licensed materials that are made available under the CC-BY 4.0 Creative Commons International License, ensuring transparency and reproducibility of the results.

Toxicity predictions, including LD50, mutagenicity, carcinogenicity, cytotoxicity, immunotoxicity, and hepatotoxicity, were performed using ProTox 3.0 – Prediction Of chemical toxicity (https://tox.charite.de/protox3/), leveraging machine-learning models validated on large experimental datasets. Results provided confidence scores and categorized anthocyanins based on their drug-like profiles and safety parameters.

Screening criteria

Anthocyanins were screened based on their molecular weights (≤500 Da) to comply with Lipinski’s Rule of Five, favorable ADME profiles without significant violations of drug-likeness filters, and acceptable toxicity parameters, including LD50 values > 500 mg/kg and low mutagenicity and carcinogenicity. Control compounds, such as pirfenidone, were chosen for their established therapeutic role as TGFβRII inhibitors and evaluated using comparable screening criteria.

Results and discussion

ADME evaluation

The ADME evaluation assesses the structure and bioavailability of the radar, physicochemical properties, lipophilicity, solubility, pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness, and medicinal chemistry.

Radar structure and bioavailability.

Evaluation of ADME can be seen in bioavailability radar images, which assess physicochemical properties, including lipophilicity, size, polarity, solubility, flexibility, and saturation(Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Bioavailability radar of anthocyanin.

Physicochemical properties

This area includes physicochemical and molecular properties, molecular weight, molecular formula, number of heavy aromatic atoms, number of heavy atoms, csp3 fraction, number of rotatable bonds, number of H-bond donors, number of H-bond acceptors, molar refractivity, and TPSA. Peonidin-3-glucoside, pelargonidin-3-glucoside, cyanidin 3-O-galactoside, delphinidin 3-glucoside, peonidin 3-galactoside, and cyanidin 3-glucoside had 7, 7, 8, 9, 7, and 8 hydrogen donors (atoms –OH and –NH) respectively. Peonidin-3-glucoside, pelargonidin-3-glucoside, cyanidin 3-O-galactoside, delphinidin 3-glucoside, peonidin 3- galactoside, and cyanidin 3-glucoside had 11, 10, 11, 12, 11, and 11 hydrogen acceptors (O and N atoms) correspondingly. Rotatable bonds of peonidin-3-glucoside, pelargonidin-3-glucoside, cyanidin 3-O-galactoside, delphinidin 3-glucoside, peonidin 3-galactoside, cyanidin 3-glucoside are 5, 4, 4, 4, 4, 5, and 4 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Physicochemical properties of anthocyanins dan pirfenidone.

| CID | Compound name | Formula | MW (g/mol) | NHA | NHD | NRB | MR | TPSA (Å2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 443,654 | Peonidin-3-glucoside | 463.41 | 11 | 7 | 5 | 112.76 | 182.44 | |

| 443,648 | Pelargonidin-3-glucoside | 433.39 | 10 | 7 | 4 | 106.27 | 173.21 | |

| 441,699 | Cyanidin 3-O-galactoside | 449.38 | 11 | 8 | 4 | 108.29 | 193.44 | |

| 443,650 | Delphinidin 3-glucoside | 465.38 | 12 | 9 | 4 | 110.32 | 213.67 | |

| 91,810,512 | Peonidin 3-galactoside | C22H23ClO11 | 498.86 | 11 | 7 | 5 | 118.62 | 182.44 |

| 12,303,220 | Cyanidin 3-glucoside | C21H21ClO11 | 484.84 | 11 | 8 | 4 | 114.15 | 193.44 |

| 40,632 | Pirfenidone | C12H11NO | 185.22 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 57.01 | 22.00 |

MW; molecular weight, NHD; several hydrogen donors; NHA, number of hydrogen acceptors MR; molar refractivity.

The TPSA values of peonidin-3-glucoside, pelargonidin-3-glucoside, cyanidin 3-O-galactoside, elphinidin 3-glucoside, Peonidin 3-galactoside, Cyanidin 3-glucoside were 182.44, 173.21, 193.44, 213.67, 182.44 and 193.44. The TPSA value of pirfenidone was 92.51.

Lipophilicity and water solubility

Lipophilicity is the most crucial parameter in drug discovery and design because lipophilicity is one of the most critical physicochemical properties of candidate drug compounds.

Lipophilicity is shown experimentally as partition coefficients (log P). Log P defines the equilibrium partitioning between water and insoluble organic solvents of non-ionized solutes. Five models designed to predict the lipophilicity of substances are XLOGP3, iLOGP, MLOGP, WLOGP, and SILICOS-IT. This study determined the lipophilicity of anthocyanin and pierfenidone compounds utilizing the XLOGP3 multimodel system. The permissible value for lipophilicity is − 7.0 < XLOGP3 < 5.0. All anthocyanins and pirfenidone have XLOGP3 levels within the acceptable value (Table 2).

Table 2.

Lipophilicity and water solubility of anthocyanins dan pirfenidone.

| Compound Name | Lipophilicity | Water solubility | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log Po/w (XLOGP3) | Log S (ESOL) | Log S (ALI) | Log S (SILICOS-IT) | |

| Peonidin-3-glucoside | 0.46 | −3.03 | −3.86 | −1.62 |

| Pelargonidin-3-glucoside | 0.49 | −2.95 | −3.70 | −1.52 |

| Cyanidin 3-O-galactoside | 0.14 | −2.82 | −3.76 | −0.93 |

| Delphinidin 3-glucoside | −0.22 | −2.68 | −3.81 | −0.34 |

| Peonidin 3-galactoside | 1.26 | −3.03 | −3.86 | −1.62 |

| Cyanidin 3-glucoside | 0.94 | −2.82 | −3.76 | −0.93 |

| Pirfenidone | 1.86 | −2.73 | −1.94 | −4.01 |

Solubility is measured as the saturation concentration at which adding solute does not raise the concentration of the solution. The solvent, temperature, and pressure determine the solubility of a substance. SwissAdme’s three solubility model approaches utilize the ESOL, Ali, and SILICOS-IT models. The Log S scale for the three models, ESOL, ALI and SILICOS-IT were: Insoluble < −10, poorly < −6, moderately < −4, soluble < −2, very < 0 < highly. Based on the Log S values in the ESOL and ALI models, all anthocyanins and pirfenidone are in the’soluble’ criteria. Moreover, the Log S value in the SILICOS-IT model for all anthocyanins is’very’ while pirfenidone is’moderate.’.

The solubility of a compound is a multidimensional physicochemical characteristic that might fluctuate based on the predictive model employed. Three esteemed models—ESOL, ALI, and SILICOS-IT—estimate the solubility of anthocyanins and pirfenidone. Each model relies on distinct algorithmic approaches and training datasets, resulting in minor discrepancies in solubility classifications for identical compounds. These discrepancies do not signify inconsistencies but instead illustrate the intrinsic sensitivity of each model to diverse structural and chemical characteristics.

The ESOL and ALI models categorized both anthocyanins and pirfenidone as “soluble,” whereas the SILICOS-IT model designated anthocyanins as “very soluble” and pirfenidone as “moderately soluble.” This divergence can be attributed to the different parameter weightings and solubility cutoff criteria employed by each model. SILICOS-IT, for example, exhibits a more conservative approach in its higher classifications, which may elucidate why pirfenidone’s solubility was classified as “moderate” by SILICOS-IT and “soluble” by the other models.

Employing numerous models facilitates a more rigorous and thorough evaluation of solubility, offering insights into the potential behavior of molecules across diverse solubility circumstances. The observed disparities do not inherently signify inconsistency; instead, they augment our comprehension by including various possible outcomes.

Achieving interpretative consistency necessitates reliance on the dominant classification among models. Considering that both ESOL and ALI classified all tested substances as “soluble,” it is deemed that “soluble” is the most representative classification for anthocyanins and pirfenidone. This approach provides a balanced interpretation, considering the subtleties of each model while assuring a reliable and comparable solubility profile among compounds. Although individual models may produce slightly different results, the consistent classification as “soluble” in two of the three models substantiates the reliability of these findings and interpretations.

Pharmacokinetics

All anthocyanins have minimal gastrointestinal absorption and cannot cross the blood–brain barrier. Also are not P-gp substrates (Table 3).

Table 3.

Pharmacokinetic properties of anthocyanins and pirfenidone.

| Compound name | GIA | BBB | P-gp substrate | CYP1A2 inhibitor | CYP2C19 inhibitor | CYP2C9 inhibitor | CYP2D6 inhibitor | CYP3A4 inhibitor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peonidin-3-glucoside | Low | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Pelargonidin-3-glucoside | Low | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Cyanidin 3-O-galactoside | Low | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Delphinidin 3-glucoside | Low | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Peonidin 3-galactoside | Low | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Cyanidin 3-glucoside | Low | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Pirfenidone | High | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

GIA: Gastrointestinal absorption, BBB: blood–brain barrier.

Peonidin-3-glucoside, pelargonidin-3-glucoside, cyanidin 3-O-galactoside, delphinidin 3-glucoside, peonidin 3-galactoside, cyanidin 3-glucoside were not found as CYP enzyme inhibitors. Pirfenidone inhibited CYP1A2 enzymes.

Drug-likeness

According to Table 4, only pelargonidin-3-glucoside (CID 443648) was shown to meet Lipinski’s rule of five violations (RO5), but pirfenidone was found to have zero violations, hence qualifying the RO5 rule.

Table 4.

Drug likeness (Lipinski RO5) of anthocyanins and pirfenidone.

| CID | Compound name | Formula | MW (g/mol) | NHA | NHD | MLOGP | Lipinski’s rule of five violation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 443,654 | Peonidin-3-glucoside | 463.41 | 11 | 7 | −1.54 | 2 | |

| 443,648 | Pelargonidin-3-glucoside | 433.39 | 10 | 7 | −1.27 | 1 | |

| 441,699 | Cyanidin 3-O-galactoside | 449.38 | 11 | 8 | −1.76 | 2 | |

| 443,650 | Delphinidin 3-glucoside | 465.38 | 12 | 9 | −2.25 | 2 | |

| 91,810,512 | Peonidin 3-galactoside | C22H23ClO11 | 498.86 | 11 | 7 | −1.33 | 2 |

| 12,303,220 | Cyanidin 3-glucoside | C21H21ClO11 | 484.84 | 11 | 8 | −1.54 | 2 |

| 40,632 | Pirfenidone | C12H11NO | 185.22 | 1 | 0 | 2.49 | 0 |

The molecular weight requirement for the ghose rule is 160 ≤ MW ≤ 480, hence peonidin 3-galactoside (498.86) and cyanidin 3-glucoside (484.84) do not meet the ghose rule. Following the ghose rule, the required WLOGP value is 0.4 ≤ WLOGP ≤ 5.6, hence all WLOGP anthocyanin values meet the ghose rule requirements, excluding peonidin 3-galactoside (−2.31), and cyanidin 3-glucoside (−5.6). (−2.61). The molar refractivity (MR) of ghose is 40 ≤ MR ≤ 130, implying that the six anthocyanins meet the MR requirements of ghose. The criteria for the number of atoms in ghose is 20 ≤ atoms ≤ 70, thus, all anthocyanins comply with the rules for the number of atoms in ghose. Table 5. reveals that peonidin-3-glucoside, pelargonidin-3-glucoside, cyanidin 3-O-galactoside, and delphinidin 3-glucoside (Ghose = 0) are the anthocyanins that adhere to the ghose rule. Pirfenidone is known to have 0 violations of the ghose rule.

Table 5.

Drug likeness (Ghose) of anthocyanins and pirfenidone.

| CID | Compound Name | Formula | MW (g/mol) | WLOGP | MR | Atoms | Ghose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 443,654 | Peonidin-3-glucoside | 463.41 | 0.69 | 112.76 | 33 | 0 | |

| 443,648 | Pelargonidin-3-glucoside | 433.39 | 0.68 | 106.27 | 31 | 0 | |

| 441,699 | Cyanidin 3-O-galactoside | 449.38 | 0.38 | 108.29 | 32 | 0 | |

| 443,650 | Delphinidin 3-glucoside | 465.38 | 0.09 | 110.32 | 33 | 0 | |

| 91,810,512 | Peonidin 3-galactoside | C22H23ClO11 | 498.86 | −2.31 | 118.62 | 34 | 2 |

| 12,303,220 | Cyanidin 3-glucoside | C21H21ClO11 | 484.84 | −2.61 | 114.15 | 33 | 2 |

| 40,632 | Pirfenidone | C12H11NO | 185.22 | 2.15 | 57.01 | 14 | 0 |

MW; molecular weight, MR; molecular refractivity.

Medicinal chemistry

SwissAdme adopted a structural warning consisting of a list of 105 fragments found by Brenk [26] that were suspected of being poisonous, chemically reactive, metabolically unstable, or possessing traits that result in poor pharmacokinetics. SwissAdme will display a chemical description of the problematic fragment in a molecule by displaying a “question mark” icon after the fragment list.Table 6.

Table 6.

Medicinal chemistry of anthocyanins and pirfenidone.

| CID | Compound Name | PAINS | Brenk |

|---|---|---|---|

| 443,654 | Peonidin-3-glucoside | 0 | 1 (oxygen_sulfur) |

| 443,648 | Pelargonidin-3-glucoside | 0 | 1 (oxygen_sulfur) |

| 441,699 | Cyanidin 3-O-galactoside | 1 (cathechol_A) | 2 (oxygen_sulfur; cathechol_A) |

| 443,650 | Delphinidin 3-glucoside | 1 (cathechol_A) | 2 (oxygen sulfur; cathechol_A) |

| 91,810,512 | Peonidin 3-galactoside | 0 | 1 (oxygen_sulfur) |

| 12,303,220 | Cyanidin 3-glucoside | 1 (cathechol_A) | 2 (oxygen sulfur; cathechol_A) |

| 40,632 | Pirfenidone | 0 | 0 |

PAINS: pan assay interference structure.

Toxicity evaluation

Toxicity analysis showed that some anthocyanins have immunotoxic properties except Pelargonidin-3-glucoside. Anthocyanins, which are cytotoxic, are peonidin-3-glucoside and peonidin 3-galactoside. Immunotoxic anthocyanins are peonidin-3-glucoside, delphinidin 3-glucoside, cyanidin 3-O-galactoside, peonidin 3-galactoside, cyanidin 3-glucoside. Pirfenidone is hepatotoxic and carcinogenic (Table 7).

Table 7.

Evaluation of anthocyanin and pirfenidone toxicity.

| Compound Name | LD50 prediction (mg/kg) | Toxicity class | Hepato toxicity | Carcinogenicity | Immunotoxicity | Mutage nicity | Cyto toxicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peonidin-3-glucoside | 5000 | 5 | inactive | inactive | Active | inactive | active |

| Delphinidin 3-glucoside | 5000 | 5 | inactive | inactive | Active | inactive | inactive |

| Pelargonidin-3-glucoside | 5000 | 5 | inactive | inactive | inactive | inactive | inactive |

| Cyanidin 3-O-galactoside | 5000 | 5 | inactive | inactive | active | inactive | inactive |

| Peonidin 3-galactoside | 5000 | 5 | inactive | inactive | active | inactive | active |

| Cyanidin 3-glucoside | 5000 | 5 | inactive | inactive | active | inactive | inactive |

| Pirfenidone | 580 | 4 | active | active | inactive | inactive | inactive |

Molecular docking analysis

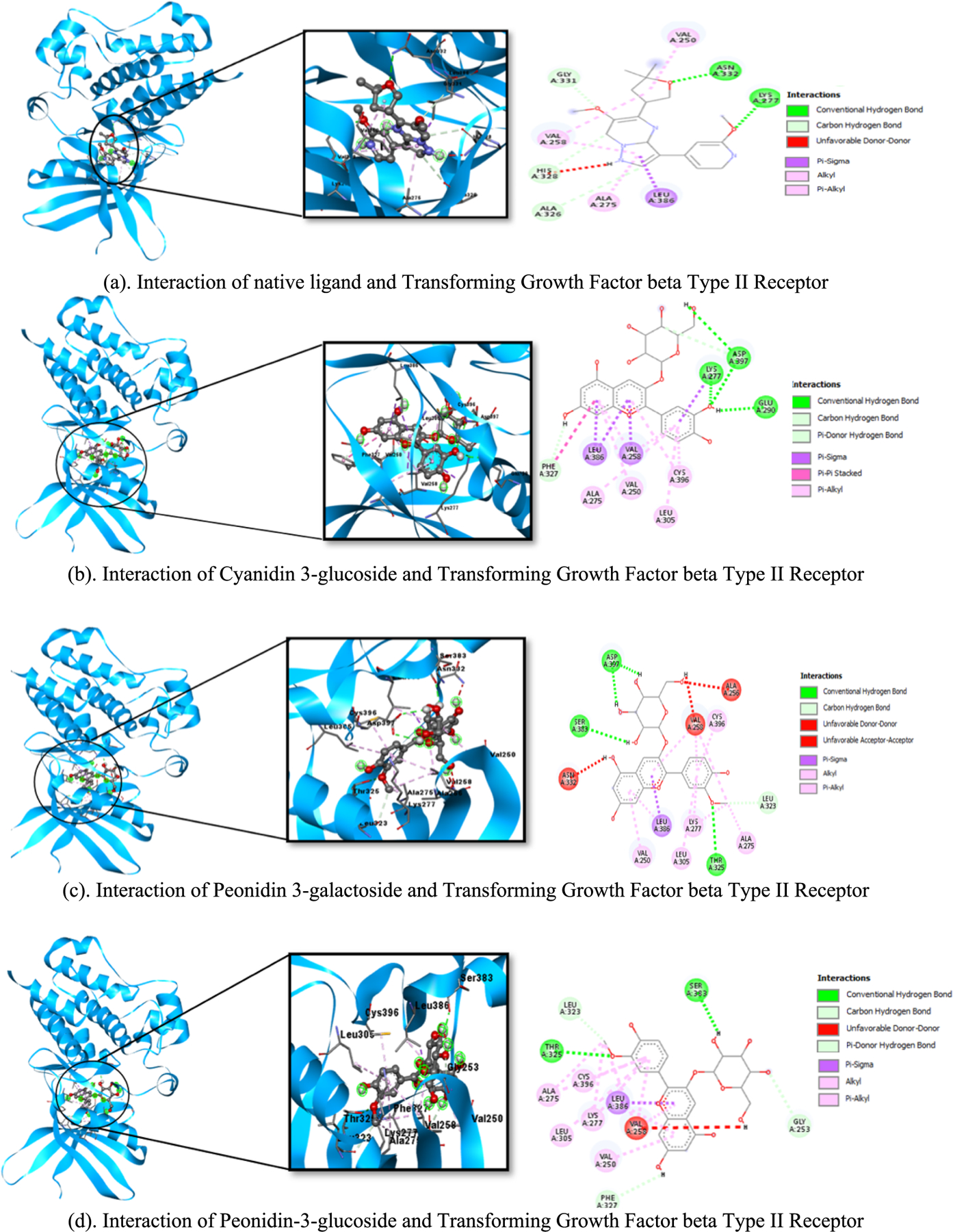

Anthocyanins (peonidin-3-glucoside, pelargonidin-3-glucoside, cyanidin 3-O-galactoside, delphinidin 3-glucoside, peonidin 3-galactoside, cyanidin 3-glucoside) bind to the same site (active site) as the native ligand (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Interaction of native ligand, anthocyanin, and pirfenidone at the active site.

Molecular docking obtained the highest binding affinity for delphinidin 3-glucoside (−10.4) and the lowest binding affinity for peonidin 3-galactoside and peonidin 3-galactoside (−9.1) and hydrogen and hydrophobic bonds were obtained as shown in Table 8. The results of redocking Transforming Growth Factor beta Type II Receptor with a native ligand on autodock tools 1.5.7 obtained a RMSD value of 0.035 Å.

Table 8.

Binding affinity and amino acid residues.

| Ligand | Binding affinity (kcal mol) | Hydrogen Bonds | Hydrophobic Bonds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Native ligand | −9,6 | Asn332, Lys277, Gly331, His328, Ala326 | Leu386, Val250, Val258, Ala275 |

| Delphinidin 3-glucoside | −10,4 | Lys277, Thr325, Ala256 | Val258, Leu386, Val250, Leu305, Ala275, Cys396 |

| Cyanidin 3-O-galactoside | −10,3 | Asp397, Glu290, Lys277, Phe327 | Leu386, Val258, Val250, Ala275, Leu305, Cys396 |

| Cyanidin 3-glucoside | −10,2 | Lys277, Asp397, Glu290, Phe327 | Val258, Leu386, Val250, Ala275, Cys396, Leu305 |

| Pelargonidin-3-glucoside | −9,8 | Ala256, Asp397 | Val258, Leu386, Ala275, Lys277, Leu305, Cys396, Val250 |

| Peonidin 3-galactoside | −9,1 | Asp397, Ser383, Thr325, Leu323 | Leu386, Val250, Leu305, Lys277, Ala275, Cys396, Ala256, Val258, Asn332 |

| Peonidin-3-glucoside | −9,1 | Thr325, Ser383, Leu323, Gly253, Phe327 | Leu386, Ala275, Cys396, Leu305, Lys277, Val250 |

| Pirfenidone | −7,9 | — | Leu 386, Val258, Ala275, Phe327, Leu305 |

The interaction of anthocyanin with TGFRII is shown below. The various anthocyanin forms were presented in distinct rows, with the 3D interaction on the left and center sides and the 2D interaction on the right (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

(a-h). The interaction between anthocyanin and TGFβRII. The different types of anthocyanin were displayed in separate rows, with the 3D interaction depicted on the left and center sides and the 2D interaction on the right Native ligand (yellow), drug reference pirfenidone (red) and anthocyanin (green). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Discussion

Ipomoea batatas have 18 anthocyanins [24], but only six anthocyanin derivatives have molecular weight ≤ 500, particularly peonidin-3-glucoside, pelargonidin-3-glucoside, cyanidin 3-O-galactoside, delphinidin 3-glucoside, peonidin 3-galactoside, and cyanidin 3-glucoside. The efficiency of anthocyanin derivative compounds that might inhibit the binding of Transforming Growth Factor beta Type II Receptor (TGFβRII) was evaluated by molecular docking after six compounds were evaluated in silico for their ADMET properties.

Examining bioactive molecules as potential therapeutic candidates are essential to the drug discovery process. Bioinformatics technologies should be employed to estimate new therapeutic candidates’ drug-likeness and ADMET properties. Bioinformatics enables us to study the physicochemical characteristics of natural compounds in a short period and a cheaper, faster [25], and more cost-effective approach [27].

SwissADME is one of the approaches used to measure the anthocyanin compound’s drug-likeness. Druglikeness is a qualitative concept used in drug design to describe how a candidate drug compound behaves “drug-like” concerning bioavailability. Lipinski, Ghose, Veber, Rule, Muegge, and Egan predicted the drug-likeness of anthocyanins. Lipinski and Ghose’s RO5 is an essential rule for characterizing bioactive compounds. [28,29] Pelargonidin-3-glucoside is the only anthocyanin that adheres to RO5 Lipinski’s drug-likeness criteria (RO5 = 1 violation). Peonidin-3-glucoside, pelargonidin-3-glucoside, cyanidin 3-O-galactoside, and delphinidin 3-glucoside, in contrast to Lipinski, did not break the Ghose rule (Ghose = 0). This reveals that anthocyanins can meet the drug-likeness criteria as potential drug compound candidates.

Topology Polar surface area (TPSA) is used to analyze the polarity of a compound and its ability to enter cells by considering sulfur and phosphorus as polar atoms [30]. Polar groups cause desolvation, which causes movement in the aqueous environment from extracellular to cell membranes. The TPSA value of compounds with good bioavailability is between 20 and 120 Å [27]. All anthocyanin compounds in purple sweet potatoes have a TPSA value > 130, which indicates that these compounds are polar and relatively challenging to penetrate cells by passive transport. The TPSA value will also be related to the GIA and BBB.

The number of rotatable bonds (NRB) indicates the flexibility of a bioactive molecule [27]. When the NRB rises, the molecule’s flexibility increases the therapeutic candidate compound’s binding effect on the target protein’s active site. A compound is flexible if it has an NRB of 0–9 [27,31]. The NRB of the six anthocyanins is 4, 5 while that of pirfenidone is 1, which means that all of the anthocyanin derivatives are more flexible and show better binding properties in docking analysis than pirfenidone.

ADMET can be utilized to evaluate the physicochemical properties of candidate drug compounds based on natural products [32]. ADMET analysis was conducted to predict lipophilicity, water solubility, and pharmacokinetic properties of six anthocyanins utilizing the SwissADME database. The lipophilic properties of the bioactive compounds were determined based on the partition coefficient of n-octanol/water (logPo/w). The lipophilic of the compounds were predicted using five models: iLOGP, XLOGP3, WLOGP, MLOGP, and SILICOS-IT. In this study, the lipophilicity of anthocyanin compounds utilized the XLOGP3 multimodel. The primary objective of this model is to reduce the difference between the expected and measured logPo/w values. The main goal of this model is to reduce the error between the predicted and calculated values of logPo/w [33]. Lipophilicity is an essential physicochemical property for estimating compounds’ oral bioavailability and expresses compounds’ ability to dissolve in fats, oils, lipids, or non-polar solvents such as hexane or toluene. The range of lipophilic values is −7.0 < XLOGP3 < 5.0. All anthocyanins meet the XLOG3P value, indicating that all anthocyanins feature lipophilic properties, allowing them to permeate lipid bilayer cell membranes.

Water solubility is another physicochemical feature that predicts a compound’s oral or parenteral administration. Three models were used to indicate anthocyanins’ water solubility (log S): the Ali Model, ESOL Model, and SILICOS-IT on SwissADME. Log S in the three models states the maximum amount of a substance that can dissolve in a solvent. The Log S score scale for the three models is Insoluble < −10, poorly < −6, moderately < −4, soluble < −2, very < 0 < highly. The Log S value of the six anthocyanin compounds is within the category of solubility, indicating that anthocyanins are acceptable for oral administration because they dissolve in water [27].

WLOP and TPSA values also indicate absorption in the gastrointestinal tract (GIA) and blood–brain barrier (BBB) [34]. Anthocyanins have a low GIA and cannot penetrate the BBB, so a nanoparticle carrier is needed to enhance anthocyanin absorption in the digestive tract. The six anthocyanins are not P-gp substrates. The binding of substances to P-gp can diminish the concentration of molecules within cells and result in the transfer of drug resistance out of cells. Therefore, this can increase the possibility of anthocyanins becoming drug-candidate compounds.

Cytochrome P450 (CYP) is an essential hemoprotein involved in drug metabolism. As the liver’s primary component of drug metabolism, it detoxifies and facilitates the excretion of xenobiotics or foreign substances by transforming fat-soluble molecules into water-soluble compounds. Drugs are metabolized through phase I, phase II reactions, or a mixture of the two. The CYP system catalyzes the most common phase I reaction, oxidation, which is the most frequent phase I reaction. Based on the identical gene sequence, the cytochrome P450 pathway is classified with a family number (CYP1, CYP2) and a letter as a subfamily marker. CYP inhibitors can alter the metabolism of concurrent pharmacological agents. Inhibitors of the CYP enzymatic pathway can raise the levels of other medicines metabolized by the same system, leading to drug toxicity. Anthocyanins have no inhibitory effect on CYP enzymes. Therefore, anthocyanins will not prevent the biotransformation of medicines processed by CYP enzymes. Thus, the accumulation of other drugs administered concurrently will not develop, and the adverse effects of the drugs will be diminished. The LD50 value for six anthocyanins is 5000 mg/kg (class 5), whereas the LD50 value for pirfenidone is 580 mg/kg (class 4), indicating that administration of anthocyanins at higher levels is predicted to be safer for human consumption than pirfenidone.

All anthocyanins (Peonidin-3-glucoside, Pelargonidin-3-glucoside, Cyanidin 3-O-galactoside, Delphinidin 3-glucoside, Peonidin 3-galactoside, Cyanidin 3-glucoside) bind to the same site (active site) as the native ligand. The active site is where the ligand binds to the protein, forming a protein–ligand complex that will conduct numerous chemical processes. The hydrogen bonds in cyanidin 3-glucoside, cyanidin 3-O-galactoside, and delphinidin 3-glucoside are similar to those of Lys277, the native ligand. However, the Lys277 amino acid residue in pelargonidin-3-glucoside and peonidin 3-galactoside is incorporated into the hydrophobic bond because the bond distance is greater than 3. The amino acid residues of the hydrophobic bonds in all anthocyanins are identical to the native ligand (Leu386, Val250, Val258, Ala275), except for peonidin-3-glucoside, which has just three amino acid residues comparable to the hydrophilic bonds in the native ligand (Leu386, Ala275, Val250). Pirfenidone has exclusively hydrophobic bonding and has no amino acid residues with hydrogen bonds. Hydrogen bonds strengthen the binding between the ligand and the receptor, whereas hydrophobic bonds make them more stable.

Binding affinity is a measure of the ability of a ligand to bind to a receptor [35]. The lower the binding affinity value, the higher the affinity between receptors and ligands, and conversely, the greater the binding affinity value, the lower the affinity between receptors [36]. All anthocyanin binding affinity values were better than the antifibrosis reference drug (pirfenidone), and the binding affinities for delphinidin 3-glucoside, cyanidin 3-O-galactoside, cyanidin 3-glucoside, and pelargonidin-3-glucoside were lower than native ligands. This demonstrates that anthocyanins can be utilized as potential therapeutic candidates to inhibit Transforming Growth Factor beta Type II Receptors in fibrosis.

Previous studies have demonstrated that anthocyanins can be employed as therapeutic candidates that suppress TGFβ via TGFβRI and TGFβRII receptors. Anthocyanins can be employed as drug candidates for inhibiting TGFβRI or acting receptor-like kinase 5 (ALK5) through the SMAD signaling mechanism [37]. TGFβ signaling occurs at type I (TGFβRI) and type II (TGFβRII) receptors. TGFβRII has five receptor types, and TGFβRI has seven receptor types and is a similar transmembrane serine/threonine kinase. In the absence of ligands, TβRI and TβRII exist as homodimers in the plasma membrane. Ligand binding induces a TβRI and TβRI complex, where TβRII phosphorylates and activates TβRI. This phosphorylation event is associated with the activation of TβRI kinase and subsequent signaling leading to fibrosis [38,39].

Anthocyanins are prevalent in purple plants, including purple sweet potatoes (Ipomoea batatas). The purple sweet potato is known to contain anthocyanins, which have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Anthocyanins are secondary metabolites derived from flavonoids. The most prevalent anthocyanidins include cyanidin, pelargonidin, peonidin, malvidin, and delphinidin (the aglycone part of anthocyanins) [20]. Anthocyanins are produced when sugars (such as glucose, rhamnose, xylose, and arabinose) bind to anthocyanidins. In addition, monosaccharides, disaccharides, and trisaccharides are bonded to anthocyanins. They attach to the 3 or 5.7 positions on the A or C ring [40]. This chemical property provides delphinidin 3-glucoside, cyanidin 3-O-galactoside, cyanidin 3-glucoside, and pelargonidin-3-glucoside with greater binding energies in TGFβRII than the reference drug (pirfenidone). Anthocyanin in I. batatas was proposed as potential compounds whose potential therapeutic activity on TGFBRII requires further exploration, based on the computer-aided predictions revealed in the current work and the previous study antifibrosis actions. In order to determine the biological activity of anthocyanin in I. batatas, in-vitro and in-vivo experiments are required.

Conclusion

This study’s findings indicate that the six anthocyanins in Ipomoea batatas may serve as inhibitors of Transforming Growth Factor Beta Type II Receptor (TGFβRII) signaling, according to in silico predictions. The findings suggest that anthocyanins could be valuable natural compounds for further investigating their potential anti-fibrotic features. Nonetheless, it is crucial to acknowledge that these results are exclusively derived from computational predictions. Subsequent research, incorporating sophisticated computational methods and thorough in vitro and in vivo investigations, is crucial to validate these anthocyanins’ biological efficacy and comprehensively elucidate their mechanism of action.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number D43TW009672. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

This article is part of a special issue entitled: ‘Treatment of Major Chronic Diseases’ published in Results in Chemistry.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Evi Lusiana: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Ernawati Sinaga: Visualization, Resources, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis. Zen Hafy: Visualization, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Debby Handayati Harahap: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Ramzi Amin: Validation, Resources, Project administration, Investigation. Irsan Saleh: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Evi Lusiana reports financial support was provided by the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health (D43TW009672). If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- [1].Albino AH, Zambom FFF, Foresto-Neto O, et al. , Renal Inflammation and Innate Immune Activation Underlie the Transition From Gentamicin-Induced Acute Kidney Injury to Renal Fibrosis, Front Physiol (2021), 10.3389/fphys.2021.606392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Zhao M, Wang L, Wang M, et al. , Targeting fibrosis: mechanisms and clinical trials, Signal Transduct. Target. Ther 7 (1) (2022) 206, 10.1038/s41392-022-01070-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Zhao X, Kwan JYY, Yip K, et al. , Targeting metabolic dysregulation for fibrosis therapy, Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 19 (1) (2020) 57–75, 10.1038/s41573-019-0040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abbasi-Kangevari M, et al. , Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019, Lancet (london, England) 396 (10258) (2020) 1204, 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Moses HL, Roberts AB, Derynck R, The Discovery and Early Days of TGF-β: A Historical Perspective, Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 8 (7) (2016) a021865, 10.1101/cshperspect.a021865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Zhan J, Liu M, Pan L, et al. , Oxidative Stress and TGF-β1/Smads Signaling Are Involved in Rosa roxburghii Fruit Extract Alleviating Renal Fibrosis, Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine : Ecam 2019 (2019) 4946580, 10.1155/2019/4946580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Nolte M, Margadant C, Controlling Immunity and Inflammation through Integrin-Dependent Regulation of TGF-β, Trends Cell Biol 30 (1) (2020) 49–59, 10.1016/J.TCB.2019.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kim KK, Sheppard D, Chapman HA, TGF-β1 Signaling and Tissue Fibrosis, Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 10 (4) (2018) a022293, 10.1101/cshperspect.a022293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hao Y, Baker D, Ten DP, TGF-β-Mediated Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Cancer Metastasis, Int J Mol Sci (2019), 10.3390/IJMS20112767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Li J, Zhang Z, Wang D, et al. , TGF-beta 1/Smads signaling stimulates renal interstitial fibrosis in experimental AAN, J. Recept. Signal Transduct. Res 29 (5) (2009) 280–285, 10.1080/10799890903078465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Meng XM, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Lan HY, TGF-β: the master regulator of fibrosis, Nat. Rev. Nephrol 12 (6) (2016) 325–338, 10.1038/NRNEPH.2016.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Chung J-Y-F, Chan M-K-K, Li J-S-F, et al. , TGF-β Signaling: From Tissue Fibrosis to Tumor Microenvironment, Int. J. Mol. Sci 22 (14) (2021) 7575, 10.3390/ijms22147575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zhang YE, Non-Smad Signaling Pathways of the TGF-β Family, Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 9 (2) (2017) a022129, 10.1101/cshperspect.a022129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Margaritopoulos GA, Vasarmidi E, Antoniou KM, Pirfenidone in the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: an evidence-based review of its place in therapy, Core Evidence 11 (2016) 11–22, 10.2147/CE.S76549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Cottin V, Maher T, Long-term clinical and real-world experience with pirfenidone in the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, Eur. Respir. Rev 24 (135) (2015) 58–64, 10.1183/09059180.00011514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Fauzi A, Titisari N, Agusti Paramanandi D (2020) Role of anthocyanin blueberry extract in the histopathological improvement of renal fibrosis - unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) model. Veterinary Practitioner 21 (2): 467–471. doi: http://www.vetpract.in/contents/role-of-anthocyanin-blueberry-extract-in-the-histopathological-improvement-of-renal-fibrosis-unilateral-ureteral-obstruction-uuo-model. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Otunctemur A, Ozbek E, Cakir SS, et al. , Pomegranate extract attenuates unilateral ureteral obstruction-induced renal damage by reducing oxidative stress, Urology Annals 7 (2) (2015) 171, 10.4103/0974-7796.150488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Laorodphun P, Arjinajarn P, Thongnak L, et al. , Anthocyanin-rich fraction from black rice, Oryza sativa L. var. indica “Luem Pua,” bran extract attenuates kidney injury induced by high-fat diet involving oxidative stress and apoptosis in obese rats, Phytother. Res 35 (9) (2021) 5189–5202, 10.1002/ptr.7188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Khoo HE, Azlan A, Tang ST, Lim SM, Anthocyanidins and anthocyanins: colored pigments as food, pharmaceutical ingredients, and the potential health benefits, Food Nutr. Res 61 (1) (2017) 1361779, 10.1080/16546628.2017.1361779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Pojer E, Mattivi F, Johnson D, Stockley CS, The Case for Anthocyanin Consumption to Promote Human Health: A Review, Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf 12 (5) (2013) 483–508, 10.1111/1541-4337.12024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Zhu F, Cai YZ, Yang X, et al. , Anthocyanins, hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives, and antioxidant activity in roots of different chinese purple-fleshed sweetpotato genotypes, J. Agric. Food Chem 58 (13) (2010) 7588–7596, 10.1021/JF101867T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Tanaka M, Ishiguro K, Oki T, Okuno S, Functional components in sweetpotato and their genetic improvement, Breed. Sci 67 (1) (2017) 52–61, 10.1270/JSBBS.16125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Montilla EC, Hillebrand S, Butschbach D, et al. , Preparative Isolation of Anthocyanins from Japanese Purple Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) Varieties by High-Speed Countercurrent Chromatography, J. Agric. Food Chem 58 (18) (2010) 9899–9904, 10.1021/jf101898j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Luo C-L, Zhou Q, Yang Z-W, et al. , Evaluation of structure and bioprotective activity of key high molecular weight acylated anthocyanin compounds isolated from the purple sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L. cultivar Eshu No.8), Food Chem 241 (2018) 23–31, 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.08.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Priyandoko D, Widowati W, Subangkit M, et al. , Molecular Docking Study of the Potential Relevanc of the Natural Compounds Isoflavone and Myriceti to COVID-19, International Journal Bioautomation 25 (3) (2021) 271–282, 10.7546/IJBA.2021.25.3.000796. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Brenk R, Schipani A, James D, et al. , Lessons Learnt from Assembling Screening Libraries for Drug Discovery for Neglected Diseases, ChemMedChem 3 (3) (2008) 435, 10.1002/CMDC.200700139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Daina A, Michielin O, Zoete V, SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules, Sci. Rep 7 (1) (2017) 1–13, 10.1038/srep42717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Lipinski CA, Lead- and drug-like compounds: the rule-of-five revolution, Drug Discov. Today Technol 1 (4) (2004) 337–341, 10.1016/J.DDTEC.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Lipinski CA, Rule of five in 2015 and beyond: Target and ligand structural limitations, ligand chemistry structure and drug discovery project decisions, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 101 (2016) 34–41, 10.1016/j.addr.2016.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Putra PP, Fauzana A, Lucida H, In Silico Analysis of Physical-Chemical Properties, Target Potential, and Toxicology of Pure Compounds from Natural Products, Indonesian Journal of Pharmaceutical Science and Technology 7 (3) (2020) 107–117, 10.24198/IJPST.V7I3.26403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kandagalla S, Sharath BS, Bharath BR, et al. , Molecular docking analysis of curcumin analogues against kinase domain of ALK5, In Silico Pharmacol 5 (1) (2017) 15, 10.1007/s40203-017-0034-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Bocci G, Carosati E, Vayer P, et al. , ADME-Space: a new tool for medicinal chemists to explore ADME properties, Sci. Rep 7 (1) (2017) 6359, 10.1038/s41598-017-06692-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Wang Y, Xing J, Xu Y, et al. , In silico ADME/T modelling for rational drug design, Q. Rev. Biophys 48 (4) (2015) 488–515, 10.1017/S0033583515000190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Panyatip P, Nunthaboot N, Puthongking P, In Silico ADME, Metabolism Prediction and Hydrolysis Study of Melatonin Derivatives, International Journal of Tryptophan Research : IJTR 13 (2020) 1178646920978245, 10.1177/1178646920978245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Al-Khayyat MZ, In silico homology modeling and docking studies of RecA from Campylobacter jejuni, International Journal Bioautomation 23 (1) (2019) 1–12, 10.7546/IJBA.2019.23.1.1-12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Pantsar T, Poso A, Binding Affinity via Docking: Fact and Fiction, Molecules : A Journal of Synthetic Chemistry and Natural Product Chemistry 23 (8) (2018) 1, 10.3390/MOLECULES23081899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Kurter H, Mert-Ozupek N, Ellidokuz H, Calibasi-Kocal G, In-silico drug-likeness analysis ADME properties, and molecular docking studies of cyanidin-3-arabinoside, pelargonidin-3-glucoside, and peonidin-3-arabinoside as natural anticancer compounds against acting receptor-like kinase 5 receptor, Anticancer Drugs 33 (6) (2022) 517–522, 10.1097/CAD.0000000000001297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Frangogiannis N, Transforming growth factor-β in tissue fibrosis, J. Exp. Med 217 (3) (2020) e20190103, 10.1084/jem.20190103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Verrecchia F, Mauviel A, Transforming growth factor-β and fibrosis, World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG 13 (22) (2007) 3056, 10.3748/WJG.V13.I22.3056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Fang J, Bioavailability of anthocyanins, Drug Metab. Rev 46 (4) (2014) 508–520, 10.3109/03602532.2014.978080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.