Abstract

Significant strides have been made in electronic (e)-prescribing standards and software applications that have further fueled the adoption and use of e-prescribing. However, for e-prescribing to realize its full potential for improving the safety, effectiveness, and efficiency of prescription drug delivery, important work remains to be carried out. This perspective describes the ultimate goal of all e-prescribing stakeholders including prescribers and dispensing pharmacists: a clear, complete, and unambiguous e-prescription order that can be seamlessly received, processed, and fulfilled at the dispensing pharmacy without the need for additional clarification from the prescriber. We discuss the challenges to creating the perfect e-prescription by focusing on selected data segments and data fields that are available in the new e-prescription transaction as defined in the NCPDP SCRIPT Standard and suggest steps that could be taken to move the industry closer to achieving this vision.

Keywords: e-prescribing, electronic prescriptions, NCPDP SCRIPT, ambulatory care, recommendations, quality

The perfect electronic (e)-prescription order

In a perfect world, prescribers would validate their patients’ personal information and reconcile their medication history during every office visit.1,2 Prior to issuing an e-prescription, the prescriber would have reviewed the patient's prescription benefit coverage and discussed the most clinically appropriate and cost-effective therapy options with the patient.3

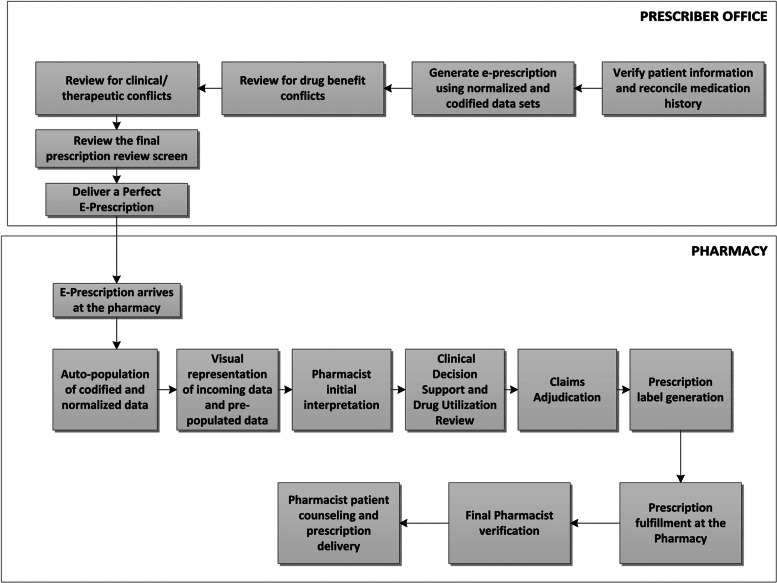

The perfect e-prescription issued by the prescriber would be limited to data that are structured and codified using recognized industry standards and data formats, with strict limitations on free-text information. These structured and codified data enable the e-prescription-generating software application to apply clinical decision support tools that alert the prescriber to possible conflicts prior to transmission of the e-prescription to the pharmacy.4 The resulting perfect prescription would be a complete, interpretable, and safe prescription order that arrives at the dispensing pharmacy electronically having already been screened for therapeutic and drug benefit conflicts. The perfect e-prescription would seamlessly populate all required data fields in the pharmacy's practice management system without the need for additional edits and would generate no conflicts during subsequent in-pharmacy and online drug utilization review. In short, the perfect e-prescription order would require only routine processing and fulfillment, thereby fully utilizing the production efficiencies the pharmacy has engineered into its policies, procedures, technologies, workflow, and management practices (figure 1). Receipt of such a complete, unambiguous, and accurate e-prescription will eliminate mundane manual pharmacy tasks such as data entry and order clarifications, thus allowing the pharmacist to focus on delivering much needed patient counseling and medication therapy management services.5–8

Figure 1:

The perfect e-prescription.

The good news is that the perfect world we envision above is achievable. Impressive strides have been made in the quality of e-prescribing in recent years. However, the ultimate goal of a perfect e-prescription remains elusive. Contributing factors include: the absence and implementation of coding formats that accurately and completely communicate prescriber intent in all circumstances; inadequate end-user interface designs; limited end-user system knowledge, training, and support; and insufficient integration of user workflow and preferences into e-prescribing systems.9–14 This paper discusses key data segments and fields within the widely implemented National Council for Prescription Drug Programs’ (NCPDP) SCRIPT Standard that we believe would move us towards achieving the goal of the perfect e-prescription.

Drug Description data field

Purpose

The Drug Description data field is contained within the SCRIPT Drug segment of the e-prescription message. This free-text data field is designed to communicate the medication name, strength, and dosage form.15 The receipt of a complete and unambiguous drug description clearly communicates the prescriber's intent to the pharmacy.

Problems/challenges

Some e-prescribing applications allow users to enter free-text drug descriptions. In many cases, these descriptions are incomplete and/or open to multiple interpretations. The absence of standardized drug descriptions is an industry-wide problem.16 Most physician and pharmacy vendor systems subscribe to one of several commercial drug databases to fulfill their drug terminology needs. Each drug database company maintains its own proprietary editorial naming convention policy. Moreover, physician and pharmacy vendors that use these drug database products also create their own in-house editorial policies, and healthcare systems may implement their own naming conventions beyond what is provided to them by their system vendor and the vendor-subscribed drug database product. Finally, some physician practices create their own local medication name lists (ie, favorites list), thereby further confusing drug description names. As a result, a pharmacy can receive dozens of different variations for a particular drug description. The receipt of a non-standardized drug description string prevents the pharmacy system from programmatically reconciling with its internal drug description using the standardized drug identifiers in the message. This, in turn, precludes them from populating internal pharmacy screens, thereby requiring staff to manually match incoming drug descriptions to internal descriptions or rekey data.

Recommendations

NCPDP has created recommendations to help alleviate this problem, including: (a) encouraging drug database companies to create recommended e-prescribing drug description names and train clients on proper usage; (b) encouraging pharmacy and physician technology vendors to send only recommended e-prescription descriptions in all outbound messages; and (c) urging prescriber and pharmacy system vendors to prohibit ‘free texting’ of drug descriptions.17 We believe industry-wide implementation of these recommendations would eliminate most observed drug description problems.

Drug Identifier data field

Purpose

The Drug Identifier data field carries a codified data element in the SCRIPT Drug segment of the e-prescription message. Early in e-prescribing, lacking a unique medication identifier, the e-prescribing industry began using the concept of a ‘representative National Drug Code (NDC)’.17 Drug identifier values such as representative NDCs and the National Library of Medicine's (NLM) RxNorm concept unique identifiers (RxCUIs) are used to communicate the identity of the prescribed drug to enable clinical decision support checks.17–19 The accurate and consistent population of drug identifiers in the e-prescription also enables the receiving pharmacy system to positively identify the incoming free-text drug description by validating it against the textual drug description associated with these identifiers. This allows the pharmacy system to pre-populate internal user screens.

Problems/challenges

The NDC directory has not been properly maintained, and the absence of an accurate and complete central repository to identify and cross-reference representative NDCs is an acknowledged industry problem.19,20 The accuracy of the representative NDC identifier received in the new e-prescription message is sometimes questionable. If the drug description associated with the representative NDC does not match the textual drug description sent in the message, then required screens in the pharmacy system cannot be auto-populated.11 The use of the NLM's RxNorm clinical terminology is recommended.19 While RxNorm codes are available directly from NLM, most physician technology vendors depend on commercial drug databases for their terminology mapping needs. The industry-wide adoption and consistent use of this terminology is still lacking. Meaningful use criteria specified by the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act, enacted as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, mandates the use of RxNorm, which may propel adoption.21

Recommendations

Prescriber technology vendors should restrict end-user access by allowing only authorized personnel to map representative NDCs and RxCUIs to drug descriptions. Prescriber technology vendors should also consistently send accurate RxCUIs when available and validate representative NDC and RxCUI identifiers at the point of care before transmitting prescriptions. Prescriber and pharmacy vendors must maintain accurate and timely drug database files and ensure that they are accessible to end users. Long term, the e-prescribing industry should move away from using representative NDCs completely and use RxNorm as the main prescribing drug identifier.

Patient Directions (Sig) data field and Structured and Codified Sig segment

Purpose

The Sig text is a 140-character free-text data field in the SCRIPT Drug segment. The Sig is also available within the SCRIPT Standard as an independent structured and codified segment. A complete and unambiguous Sig (ie, directions for use) communicates the prescriber's intent for how the patient should take the medication. Communication of clear and complete directions for use is essential to ensure proper prescription labeling, appropriate pharmacist counseling, and optimal medication use.22

Problems/challenges

As with paper prescriptions, considerable variability is found in the electronic Sig text strings that are generated by prescribers.23–25 A seemingly simple Sig such as ‘take one tablet every day’ can be represented in numerous ways, and the absence of standardization can lead to requests for clarification by the pharmacy. In the current SCRIPT version used by the industry, prescribers cite a problem when some directions are greater than 140 characters. A standard codified Sig structure has been a recognized industry need for many years. Although this functionality is available in the SCRIPT Standard, feedback from pharmacy and physician technology vendors suggests that the approach taken in the structure is complex and cumbersome to implement. However, our initial research indicates that most commonly used ambulatory Sigs are fairly simple in construction and hence can be more easily mapped to the standard codified Sig structure.

Recommendations

Universal Medication Schedule (UMS) is a methodology that simplifies medication administration instructions for the patient and/or their caregiver and is intended as an optimal way to convey Sigs for use to the patient.26 Variability in the Sig text strings observed in e-prescriptions has the potential to introduce quality defects; industry-wide implementation of UMS can result in standardization of Sigs, thus reducing variations as described in table 1.27 To this effect, NCPDP, in April 2013, published a white paper to help the industry implement UMS using NCPDP standards.26 Industry-wide deployment of a Structured and Codified Sig standard in SCRIPT is needed. In September 2013, NCPDP created a task group to develop detailed guidance around the implementation of the Structured and Codified Sig standard as available in the 10.6 NCPDP SCRIPT and future SCRIPT versions, and create examples to help facilitate adoption. Finally, the length of the free-text Sig field as available within the Drug segment of SCRIPT has been increased from 140 to 1000 characters in SCRIPT Standard V.2012, and it is recommended that the industry implement a future version of SCRIPT as soon as possible to accommodate all legitimate use cases.

Table 1:

Example of Universal Medication Schedule Sig

| Sig string variations found in e-prescriptions | Universal Medication Schedule sig |

|---|---|

| Take one tablet twice a day | Take one tablet in the morning and take one tablet in the evening |

| One tablet twice daily | |

| Twice daily | |

| Take one tablet by mouth twice a day | |

| Take tablet twice a day | |

| Take twice daily |

Notes data field

Purpose

The Notes data field in the Drug segment is a free-text optional field in the SCRIPT standard. This field allows prescribers to include additional patient-specific information that is related to, but not part of, the prescription.28 An example is a prescriber's request to the pharmacist to reinforce key aspects of therapy (eg, ‘Reinforce to mother that medication must be given until it is all gone’). Importantly, the Notes field should not be used for prescription and other types of information that has a designated, standard field.17,28

Problems/challenges

The Notes field is often populated with information that should be included in one of the other designated fields, most commonly patient Sig.11 This often results in confusing or contradictory information to that included in other parts of the e-prescription message such as Sig or Quantity, thereby necessitating contact with the prescriber to resolve. The Notes field is also sometimes populated with instructions that are to be handled in other available transactions (such as a new prescription containing a note to cancel a previous prescription).

Recommendations

Better user training, end-user interface enhancement, and ongoing content monitoring by physician technology vendors is needed to reduce inappropriate use of the Notes field.17,29 Industry-wide adoption, utilization, and end-user education on other NCPDP SCRIPT transactions—specifically ‘Change Prescription’ and ‘Cancel Prescription’ messages—are key towards ensuring complete resolution of this problem. NCPDP's Electronic Prescribing Best Practices Task Group is working to structure this Notes data field and its use. Presentation of structured notes strings and creation of new data fields in the SCRIPT Standard will result in machine-readable, actionable data that can then be put to meaningful use at the pharmacy. When available, prompt industry-wide deployment of this enhancement will help mitigate the problems. However, the Notes field should continue to allow prescribers to enter free text only in cases where it is needed.

Additional requirements

In addition to the data segments and fields discussed above, realizing our vision of a perfect e-prescription will also require a strategy that addresses other components of the e-prescribing process including implementation of continual end-user training programs, interface improvements targeted towards improving usability, and integration of end-user input into system designs.9,30–32 Achievement of this goal will require the collective efforts of standards organizations such as NCPDP, with industry involvement from database suppliers, e-prescribing networks, and physician and pharmacy technology vendors.

Conclusion

Properly implemented and used, e-prescribing has demonstrated improved safety, effectiveness, and efficiency of patient care. However, some work remains to be carried out before the potential benefits of this transformative technology are fully realized. In this paper we have discussed the need for implementation of several key SCRIPT data fields and segments and adoption of best practice recommendations. While the current SCRIPT Standard does contain important features, it is important that the e-prescribing industry continues to move forward to adopt and implement the most recent version of the SCRIPT Standard and encourage improvements in interface designs and end-user training.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Lynne Gilbertson, Vice President of Standards at NCPDP, for her critical review of the manuscript.

Contributors

The corresponding author, AAD, takes responsibility for the integrity of this manuscript. Study concept and design: AAD, MTR. Drafting of manuscript: AAD, MTR. Critical revision of manuscript for important intellectual content: AAD, MTR. Administrative, technical, or material support: AAD. Supervision: AAD.

Competing interests

None.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lapane KL, Whittemore K, Rupp MT, et al. Maximizing the effectiveness of e-prescribing between physicians and community pharmacies. Final Progress Report submitted to AHRQ on January 28, 2007.

- 2. Grossman JM, Gerland A, Reed MC, et al. Physicians’ experiences using commercial e-prescribing systems. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26:w393–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fischer MA, Vogeli C, Stedman M, et al. Effect of electronic prescribing with formulary decision support on medication use and cost. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:2433–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. National Research Council. Preventing medication errors: quality chasm series. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Crosson JC, Etz RS, Wu S, et al. Meaningful use of electronic prescribing in 5 exemplar primary care practices. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9:392–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kilbridge P. E-prescribing. Oakland, CA: California HealthCare Foundation, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Institute for Safe Medicine Practices. A call to action: eliminate handwritten prescriptions within three years! http://www.ismp.org/newsletters/acutecare/articles/whitepaper.asp (accessed April 2014).

- 8. Harvey J, Avery AJ, Waring J, et al. The socio-technical organisation of community pharmacies as a factor in the Electronic Prescription Service Release Two implementation: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Singh H, Mani S, Espadas D, et al. Prescription errors and outcomes related to inconsistent information transmitted through computerized order entry: a prospective study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:982–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Palchuk MB, Fang EA, Cygielnik JM, et al. An unintended consequence of electronic prescriptions: Prevalence and impact of internal discrepancies. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2010;17:472–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Grossman JM, Cross DA, Boukus ER, et al. Transmitting and processing electronic prescriptions: experiences of physician practices and pharmacies. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012;19:353–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rupp MT, Warholak TL. Evaluation of e-prescribing in chain community pharmacy: best-practice recommendations. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2008;48:64–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Warholak TL, Rupp MT. Analysis of community chain pharmacists’ interventions on electronic prescriptions. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2009;49:59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Koppel R, Metlay JP, Cohen A, et al. Role of computerized physician order entry systems in facilitating medication errors. JAMA. 2005;293:1197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. National Council for Prescription Drug Programs (NCPDP). SCRIPT Standard Implementation Guide. October 2008 Version 10.6.

- 16. Levin MA, Krol M, Doshi AM, et al. Extraction and mapping of drug names from free text to a standardized nomenclature. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2007:438–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. National Council for Prescription Drug Programs (NCPDP). SCRIPT Implementation Recommendations. April 2014 Version 1.25. http://www.ncpdp.org/NCPDP/media/pdf/SCRIPT-Implementation-Recommendations-V1-25.pdf (accessed April 2014).

- 18. Teich JM, Osheroff JA, Pifer EA, et al. CDS Expert Review Panel. Clinical decision support in electronic prescribing: recommendations and an action plan: report of the joint clinical decision support workgroup. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2005;12:365–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bell DS, O'Neill S, Reynolds K, et al. Evaluation of RxNorm in Ambulatory Electronic Prescribing. TR-941-CMS. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation, 2011. http://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/TR941 (accessed Feb 2013). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Levinson DR. The Food and Drug Administration's National Drug Code Directory. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General, 2006. http://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-06-05-00060.pdf (accessed Feb 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 21. United States Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). Health Information Technology: Initial Set of Standards, Implementation Specifications, and Certification Criteria for Electronic Health Record Technology; Final Rule 45 CFR Part 170. http://edocket.access.gpo.gov/2010/pdf/2010-17210.pdf (accessed Feb 2014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hernandez LM. ed. Standardizing Medication Labels: Confusing Patients Less. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bailey SC, Persell SD, Jacobson KL, et al. Comparison of handwritten and electronically generated prescription drug instructions. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:151–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wolf MS, Shekelle P, Choudhry NK, et al. Variability in pharmacy interpretations of physician prescriptions. Med Care. 2009;47:370–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shrank WH, Agnew-Blais J, Choudhry N, et al. The variability and poor quality of medication container labels: a prescription for confusion. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1760–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. National Council for Prescription Drug Programs (NCPDP). Universal Medication Schedule (UMS) April 2013. http://www.ncpdp.org/Education/Whitepaper?page=2 (accessed Feb 2014).

- 27. Wolf MS, Curtis LM, Waite K, et al. Helping patients simplify and safely use complex prescription regimens. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:300–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Whittemore Ken., Jr. “Guidelines to Creating High-Quality Electronic Prescriptions in the Ambulatory Healthcare Setting,” Surescripts LLC, 2012. http://surescripts.com/docs/default-source/Resources/quality_e-prescription_guidelines_surescripts.pdf?sfvrsn=0 (accessed April 2014) [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dhavle, Ajit A. “Best Practices and Implementation Clinical Quality Checklist v1.0c” Surescripts LLC, 2012. http://surescripts.com/docs/default-source/Resources/best_practices_implementation_clinical_quality_checklist_surescripts.pdf (accessed Apr 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 30. Campbell EM, Guappone KP, Sittig DF, et al. Computerized provider order entry adoption: implications for clinical workflow. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:21–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Aarts J, Ash J, Berg M. Extending the understanding of computerized physician order entry: implications for professional collaboration, workflow and quality of care. Int J Med Inform. 2007;76(suppl 1):S4–S13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. van der Sijs H, Aarts J, Vulto A, et al. Overriding of drug safety alerts in computerized physician order entry. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006;13:138–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]