Abstract

Background:

Postoperative liver failure due to insufficient liver cell quantity and function remains a major cause of mortality following surgery. Hence, additional investigation and elucidation are required concerning suitable surgeries for promoting in vivo regeneration.

Methods:

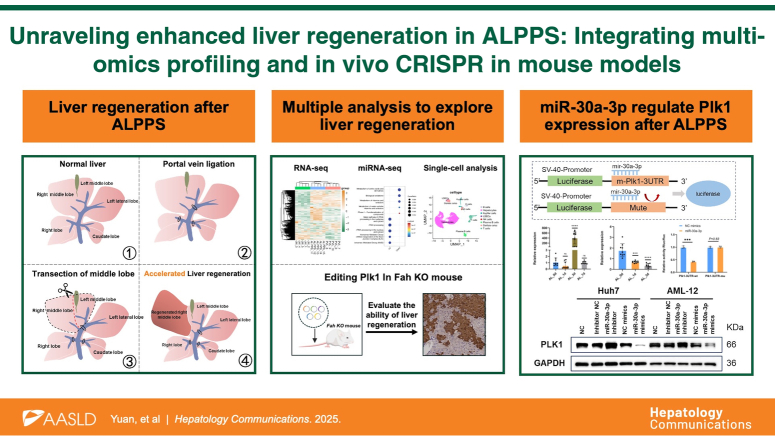

We established the portal vein ligation (PVL) and associated liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy (ALPPS) mouse models to compare their in vivo regeneration capacity. Then, RNA-seq and microRNA-seq were conducted on the livers from both mouse models. Weighted gene co-expression network analysis algorithm was leveraged to identify crucial gene modules. ScRNA-seq analysis was used to understand the distinctions between Signature30high hepatocytes and Signature30low hepatocytes. Moreover, in vivo, validation was performed in fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase knockout mice with gene editing using the CRISPR-cas9 system. A dual luciferase report system was carried out to further identify the regulatory mechanisms.

Results:

RNA-seq analysis revealed that ALPPS could better promote cell proliferation compared to the sham and portal vein ligation models. Moreover, a Plk1-related 30-gene signature was identified to predict the cell state. ScRNA-seq analysis confirmed that signature30high hepatocytes had stronger proliferative ability than signature30low hepatocytes. Using microRNA-seq analysis, we identified 53 microRNAs that were time-dependently reduced after ALPPS. Finally, miR-30a-3p might be able to regulate the expression of Plk1, contributing to the liver regeneration of ALPPS.

Conclusions:

ALPPS could successfully promote liver regeneration by activating hepatocytes into a proliferative state. Moreover, a Plk1-related 30-gene signature was identified to predict the cell state of hepatocytes. miR-30a-3p might be able to regulate the expression of Plk1, contributing to the liver regeneration of ALPPS.

Keywords: cell proliferation, in vivo CRISPR, liver regeneration, miR-30a-3p, Plk1

INTRODUCTION

Hepatectomy is a surgical procedure involving partial removal of liver tissues and is commonly used for treating malignant liver tumors.1 Nonetheless, post-hepatectomy liver failure has emerged as a primary cause of mortality following surgery, imposing constraints on patients with primary liver cancer. In cases of well-preserved liver function, it is imperative to ensure that the future liver remnant (FLR) exceeds a threshold of 25%, while patients with cirrhosis necessitate an FLR exceeding 40%.2 Therefore, inadequate FLR currently poses a significant challenge impeding the progress of hepatic surgery.

By excising the affected portion of the liver, hepatectomy aims to alleviate hepatic congestion, optimize liver function, and stimulate compensatory liver regeneration. Substantial progress in surgical techniques of hepatectomy, alongside improvements in perioperative care and surgical precision, has led to enhanced outcomes and decreased perioperative complications. However, the efficacy of hepatectomy in the context of promoting liver regeneration remains inadequately researched.

To promote the regeneration of the residual liver, traditional methods mainly employ portal vein embolization (PVE), but its effectiveness remains limited.3 In recent years, research on the technique of 2-stage hepatectomy has confirmed that this technique, combining liver partition and portal vein ligation (PVL), is called associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy (ALPPS). It is a novel 2-staged approach to hepatectomy and might promote the speed of liver regeneration. As a result, ALPPS might contribute to the treatment of HCC that would otherwise be thought to be unresectable.4 And most studies supported that this innovative approach has a faster pace and larger scale advantage in promoting residual liver hypertrophy compared to PVE.3,5 However, the precise mechanism of ALPPS-induced acceleration of liver regeneration is not fully understood at present. Liver regeneration is a complex physiological process controlled by a series of molecular signaling pathways, which is essential for maintaining hepatic homeostasis and restoring liver volume after injury or resection. The regenerative ability of the liver is primarily attributed to the proliferative potential of hepatocytes. Hepatectomy is a potent stimulus for liver regeneration, triggering a series of cellular events characterized by hepatocyte proliferation, angiogenesis, and extracellular matrix remodeling. Understanding the mechanisms of liver regeneration induced by hepatectomy, especially ALPPS, is essential for optimizing surgical strategies and utilizing the regenerative potential of the liver for therapy.

In our preliminary research, a distinct subgroup of hepatocytes exhibiting significant proliferation after liver resection was identified 48 hours after hepatectomy,6 indicating the potential of both hepatectomy surgeries, including PVL and ALPPS models, to enhance hepatocyte proliferation. In the present study, we successfully constructed the ALPPS model in mice, which could be more conveniently used to study the potential mechanism of liver regeneration after hepatectomy.1 We found that mice undergoing ALPPS surgery showed significantly enhanced hepatocyte proliferation compared to traditional PVL model mice and WT mice. Furthermore, the liver-to-body weight ratio and the expression levels of Mki67 (a widely recognized cell proliferation marker) in liver tissue 2 days postoperatively far exceeded those in the PVL group. To elucidate the regulatory mechanisms in ALPPS mice, we conducted RNA-seq and microRNA-seq sequencing on WT mice, PVL mice, and ALPPS mice and used bioinformatics analysis to reveal their potential regulatory networks, providing new insights into in vivo hepatocyte regeneration.

METHODS

Animals

C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (JAX: 000664). Fah KO (fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase knockout) mice were purchased from GemPharmatech (T052634) and were backcrossed for at least 6 generations onto the C57BL/6 background. Fah KO mice were maintained on 7.5 mg/mL nitisinone (Macklin, CAS:104206-65-7) until hydrodynamic injection was performed at 8–10 weeks of age. Genotyping was performed with Full Length-F (5′-TGATGGCTGCCCAGTCCTTTAAG-3′) and Full-Length-R (5′-TGACAGATTGTGTCCCTGAGCTG-3′) to distinguish Het from WT, and Inside-F(5′-AGTTCCCAACTCGTGAATGGATG-3′) and Inside-R (5′- GTGAATGCACTGAAACAGAATCAGG-3′) to distinguish KO from Het.

ALPPS surgery and liver sample collection

All animals used in this study were bred and housed under SPF conditions on a 12-hour light/dark cycle with free access to standard chow and water in ZHBY Biotechnology. All experiments in this protocol were approved by the Veterinary Authorities of the Jiangxi Provincial People’s Hospital (Ethnic number NYLLSC20240412). Furthermore, all experimental steps were performed in strict compliance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

ALPPS surgery was performed as described.1 C57BL/6J were anesthetized with isoflurane (2%–4%) and underwent abdominal incision. The portal branches of the liver lobes were individually ligated using 8-0 silk. The right middle lobe’s portal vein and artery were preserved as the FLR, representing 10%–13% of the total liver volume. An 80% liver parenchymal transection was achieved using bipolar forceps and hemostatic agents between the right middle lobe and the left middle lobe. A routine cholecystectomy was performed during the initial surgery. Each animal was monitored throughout the perioperative period. Weights of the resected and remnant liver were recorded at surgery and sacrifice. Liver and plasma samples were collected at 1, 2, 3, and 7 days after surgery and stored at −80 °C. Four to five mice were used per time point for histology, immunofluorescence staining, and liver function tests. The operation videos have been uploaded in the supplemental files (Video 1).

Video 1.

ALPPS surgery was performed as described previously(1). C57BL/6J were anesthetized with isoflurane (2% to 4%) and underwent abdominal incision. The portal branches of the liver lobes were individually ligated using 8-0 silk. The right middle lobe’s portal vein and artery were preserved as the future liver remnant (FLR), representing 10% to 13% of the total liver volume. An 80% liver parenchymal transection was achieved using bipolar forceps and hemostatic agents between the right middle lobe and left middle lobe. A routine cholecystectomy was performed during the initial surgery. Each animal was monitored throughout the perioperative period. Weights of the resected and remnant liver were recorded at surgery and sacrifice. Liver and plasma samples were collected at 1, 2, 3, and 7 days after surgery and stored at −80°C. Four to five mice were used per time point for histology, immunofluorescence staining, and liver function tests. The operation videos have been uploaded in the supplementary files. (see video 1)

Plasmid and sgRNA construction

The transposon plasmids used for CRISPR KO screening (FAH-Cas9) and CRISPRa screening (FAH-dCas9-VP64) were a gift from Zhu Lab.7 sgRNAs for activation screening were extracted from Dr Rosenblum8 (Supplemental Table S2, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B881).

In vivo CRISPR validation

Twenty micrograms of the library plasmid and 1 μg of SB100 (Addgene #34879) were suspended in a 0.9% NaCl solution to a final volume equivalent to 10% of the mouse’s body weight. This mixture was then hydrodynamically injected into the tail vein of 8-week-old Fah KO mice. Nitisinone water was discontinued immediately after hydrodynamic injection. After 1 month, the livers were harvested.

Cell culture

In this study, all cell lines were acquired from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (China). The human hepatoma cell line HuH-7 and the mouse AML-12 cell line were cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Excell). All cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2.

RNA interference

For gene interference, we obtained mimics and inhibitors of the miR-30a-3p gene, as well as negative control mimics and inhibitors, from HANBIO Company. These mimics and inhibitors were introduced into HuH-7 and AML-12 cells using the jetPRIMER transfection reagent from Polyplus Transfection (France) when the cell confluence reached 30%–50%. The sequences of the mimics targeting the miR-30a-3p gene are provided in Supplemental Table S2, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B881

Western blotting

To extract total protein from the aforementioned cells and tissue samples, RIPA lysis buffer (Solaribio) was utilized on ice. Equal amounts of protein from each sample were separated by 10%–12% SDS-PAGE (Servicebio) and subsequently transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore). The membranes were treated with a blocking buffer consisting of TBST mixed with 5% skim milk at room temperature for 1 hour. Incubation with primary antibodies, PLK1 (1:1000, A21082, ABclonal), and GAPDH (1:100,000, 60004-1-Ig, Proteintech), was carried out overnight at 4 °C. After 3 washes with TBST, the membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies. Following this, membranes were treated with an enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Easysee Western Blot Kit), and digital images of the blots were captured using an imaging system (Bio-Rad).

Liver function tests

Blood samples were obtained through retro-orbital collection using heparinized tubes. Following collection, the blood was transferred into 1.5 mL tubes and centrifuged at 2000g for 15 minutes at 4 °C. The resulting supernatants, referred to as plasma, were analyzed for liver damage using AST and ALT activity kits (Beyotime #C0018S).

Histology, immunohistochemistry, and immunofluorescence

The tissues were fixed in 10% formalin for 72 hours. Paraffin-embedded slides were deparaffinized in xylene and underwent dehydration and rehydration with a series of ethanol solutions (100%, 90%, 80%, 70%, 50%, and 30%) and deionized water. Antigen retrieval was performed using a 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) containing 0.05% Tween 20 at a sub-boiling temperature for 20 minutes in a microwave. After natural cooling for 30 minutes, endogenous enzyme activity was blocked using 10% hydrogen peroxide. Following the manufacturer’s instructions, immunohistochemistry was performed using the VECTASTAIN ABC-HRP kit (Beyotime #P0603). The procedures for immunofluorescence can be referred to the aforementioned steps. The following antibodies were used: FAH (ThermoFisher #PA5-93078; 1:800), PTEN (Cell Signaling #9559; 1:250), Ki67 (Abcam #15580; 1:200), and EdU (Ribobio #C10310-3; 1:300). Hematoxylin (Beyotime #C0105M) was used for counterstaining the slides.

RNA extraction and qRT-PCR

Liver total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen #15596026). For qRT-PCR, 1 mg of cDNA was synthesized from 20 mL of total RNA using 5×PrimeScriptTM RT Master Mix (Takara Bio Inc.). qRT-PCR analysis was conducted using 2×SYBR Green qRT-PCR Master Mix (Selleck). mRNA levels were normalized to the expression of GAPDH mRNA. Data analysis was performed using the delta-delta method to evaluate the relative mRNA levels between the control and experimental groups of mice. Each individual mouse was assessed with 3 replicates. The normalized expression values from the experimental group were divided by the average normalized expression values from the control group to obtain the fold change in expression. The primer sequences for qRT-PCR are listed in Supplemental Table S1, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B882.

Dual luciferase assay

Cells were seeded at 50% density in each well of the cell culture plate (293T cells and primary mouse liver cells). Cells were transfected with plasmids at ~70% confluency. Separate transfection reagent, plasmid, and miRNA negative control/mimic groups were prepared, and were diluted, mixed, and added to the wells. After 6 hours, the medium was replaced with a fresh culture medium. Cells were washed with PBS 36–48 hours after transfection. PLB lysis buffer was added and shaken for 20–30 minutes to lyse the cells completely. The cell lysate was transferred to a 96-well plate, and Luciferase Assay Reagent II was added for the luciferase reaction. The luminescence intensity of luciferase activity was measured. Stop&Glo Reagent was added to stop the reaction and the luminescence intensity of the internal control, Renilla luciferase activity, was measured. Readings were recorded, and the RLU1/RLU2 ratio was calculated to analyze the response strength of different groups.

Analysis of RNA-seq data related to PVL and ALPPS operations

We conducted RNA-seq sequencing on WT mice, PVL mice, and ALPPS mice. The sequencing was performed by Omicshare. First, we assessed the sequencing data quality using fastqc. Subsequently, trim_galore software was employed for quality control, and the data were further aligned to the mm10 genome using hisat2. We then converted the bam file to a bam file format using samtools. Finally, featurecounts was used to quantify the gene expression levels. For the differential expression analysis in bulk RNA-seq, we used the LIMMA package, considering mRNAs with logFC >2 and adjusted p values <0.01 as differentially expressed. The Limma package, an R package for differential expression analysis in expression profiles, was used to identify genes with significant differential expression between comparison groups9. The R package “limma” was employed to analyze the molecular mechanisms of sepsis data, identifying differentially expressed genes between control and disease samples using a differential gene filtering criterion of |logFC| >1.5 and p value <0.05, and generating a volcano plot.

Analysis of microRNA-seq data related to PVL and ALPPS operations

We performed microRNA-seq sequencing on WT mice, PVL mice, and ALPPS mice. The sequencing was conducted by Omicshare. Initially, we assessed the sequencing data quality using fastqc. Subsequently, trim_galore software was employed for quality control, and bowtie2 was used for genome alignment. In the microRNA-seq analysis, since our research did not involve the discovery of new microRNAs, we used sequences downloaded from the miRBase database as the alignment reference (www.mirbase.org/). It should be noted that in the downloaded sequences, “U” was replaced with “T” since we sequenced gene sequences. Afterward, the bam file was converted to the bam file format using samtools. Finally, featurecounts was used for gene expression quantification. The LIMMA package was applied for differential expression analysis in microRNA-seq, with logFC >1 and adjusted p < 0.01 as criteria for identifying differentially expressed microRNAs.

Function enrichment analyses

For estimating the potential functions of interested gene sets, we adopted the metascape web tools for function enrichment analyses (https://metascape.org/gp).

WGCNA for bulk RNA-seq data

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) with the default parameters was leveraged to explore potential hub gene modules for ALPPS.10 In the present study, we performed the WGCNA pipeline on the bulk RNA-seq data: (i) WGCNA for comparing the control (sham), PVL, and ALPPS groups; (ii) WGCNA for detecting the time-dependent genes using RNA-seq data on 1 day, 2 days, 3 days, and 7 days after ALPPS.

Data collection

All data sets in the present work were collected from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, including GSE180012, GSE158864, GSE167034, GSE215423, GSE83598, and GSE4528. Supplemental Table S1, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B882, lists detailed information about all sequencing data.

Principal component analysis

Principal component analysis (PCA) analysis was conducted to assess the relationship among control (sham), PVL, and ALPPS mice. The PCA was performed based on bulk RNA-seq (mRNA-seq) and microRNA-seq data.

Gene set enrichment analysis and single-sample gene set enrichment analysis

To estimate the activation of the 30-gene signature, a single-sample gene set enrichment analysis algorithm in gene set variation analysis package was used for estimating signature score in mRNA-seq data.11 More, the clusterProfiler package was also adopted for gene enrichment analysis, unveiling the potential differences among control (sham), PVL, and ALPPS operations.12

Single-cell RNA-seq analysis

We collected data from single-cell RNA sequencing (GSE151309)13 and aligned sequencing reads with mm10 genome using the Cell Ranger pipeline provided by 10x Genomics. Subsequently, we employed the Seurat package14 for quality control and analysis of the expression matrix. We normalized and scaled the data, and utilized the “FindNeighbors” and “FindClusters” functions for clustering and identifying cell subpopulations. Cell types were annotated during the clustering process based on the expression of known marker genes to accurately identify and classify cell populations. We tried to understand the expression pattern of the 30-gene signature in this partial hepatectomy (PHx)-related scRNA data, which enabled us to comprehensively understand the heterogeneity and functional features of cells in liver regeneration, laying the foundation for subsequent functional analysis and result interpretation.

Trajectory and cell-cell communication analyses

To better understand the differences between the signature30high hepatocytes and the signature30low hepatocytes, the hepatocytes in scRNA-seq data were separated into the signature30high hepatocytes and the signature30low hepatocytes based on the 30-gene signature score. Then, the trajectory analysis of hepatocytes was performed based on the Monolce2 package15 and the cell-cell communication analysis of all cell types was conducted using cellchat package.16

Prediction of potential targets for polo-like kinase 1

In the present work, 3 databases, namely RNA22 (https://cm.jefferson.edu/rna22/),17 miRWalk (http://mirwalk.umm.uni-heidelberg.de/),18 and TargetMiner (https://www.isical.ac.in/),19 were adopted to predict the potential microRNAs for polo-like kinase 1 (Plk1). Results showed common microRNAs that were intersected in 3 online databases as key microRNAs that had the potential to regulate the expression of Plk1.

Statistical analysis

The statistically significant difference is estimated by the Student 2-tailed t test. p values of <0.05, 0.01, and 0.001 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Characteristics of liver regeneration after PVL

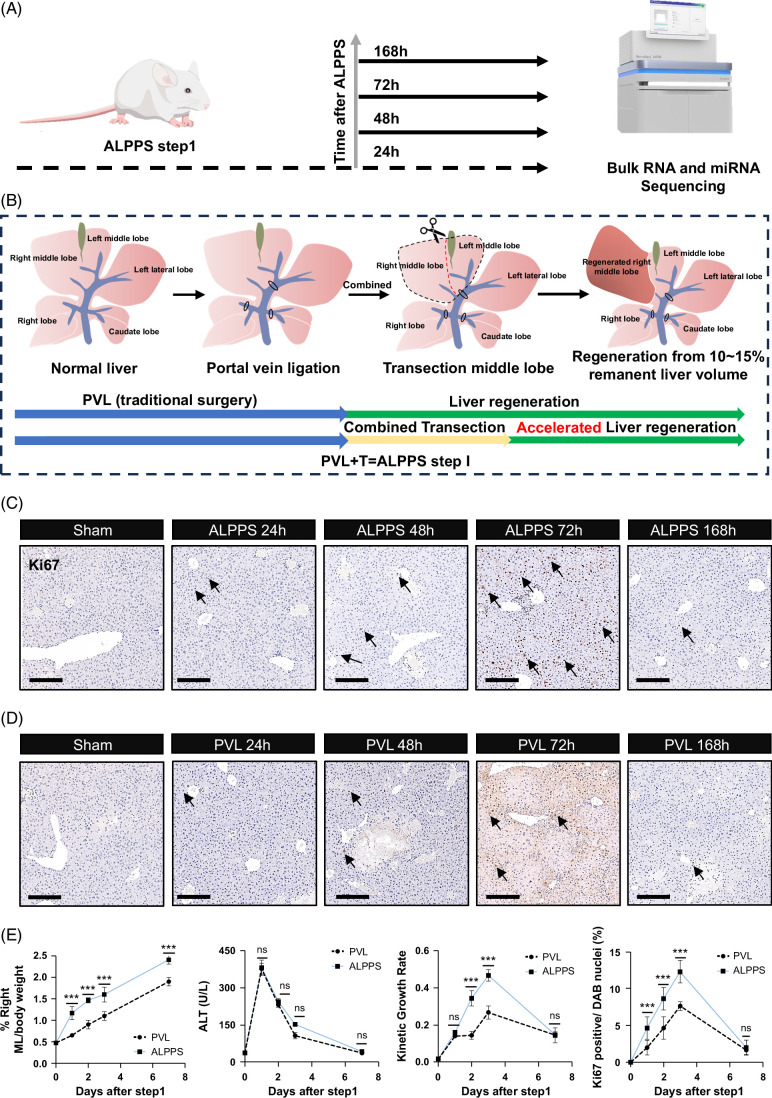

The comparison of operation benefits between PVL and ALPPS still remains to be unveiled. Here, we performed the RNA-seq of liver tissues under PVL and ALPPS surgery for better deeper analyses. The flowchart of this study is shown in Figure 1A.

FIGURE 1.

Different time points of RNA sequencing analysis from regenerated liver tissues after mouse ALPPS and PVL. (A) Preparation of liver samples from mice at various time points (0, 24, 48, 72, and 168 h) following ALPPS and PVL for RNA sequencing (harvest mice, n = 5, 3, 4, 3, 4). (B) Four liver schematic diagrams were utilized to succinctly illustrate the operational procedures of ALPPS and PVL. Mouse liver displayed lobular characteristics comparable to those of the human liver. Notably, the middle lobe can be further subdivided into left and right middle lobes based on the portal vein blood supply (subfigure I). Following the ligation of the portal vein branches (subfigure II) of the RL, CL, and ML + LLL, we simulated the traditional surgical process of PVL. The presence of an ischemic line in the middle lobe allowed for dissection along this line (subfigure III), thereby facilitating the first step of ALPPS (subfigure IV). (C) The intensity of Ki67 expression in the liver on days 1, 2, 3, and 7 following ALPPS, bar = 200 μm, n = 3. (D) The intensity of Ki67 expression in the liver on days 1, 2, 3, and 7 following PVL, bar = 200 μm, n = 3. (E) Changes in the remnant liver-to-body weight ratio, serum ALT levels, kinetic growth rate, Ki67 positive ratio following ALPPS and PVL surgeries at different points. Data are shown as means ± SEM. ***p < 0.001, ns = not statistically significant, compared to the PVL group. Abbreviations: ALPPS, associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy; CL, caudate lobe; LLL, left lateral lobe; ML, middle lobe; PVL, portal vein ligation; RL, right lateral.

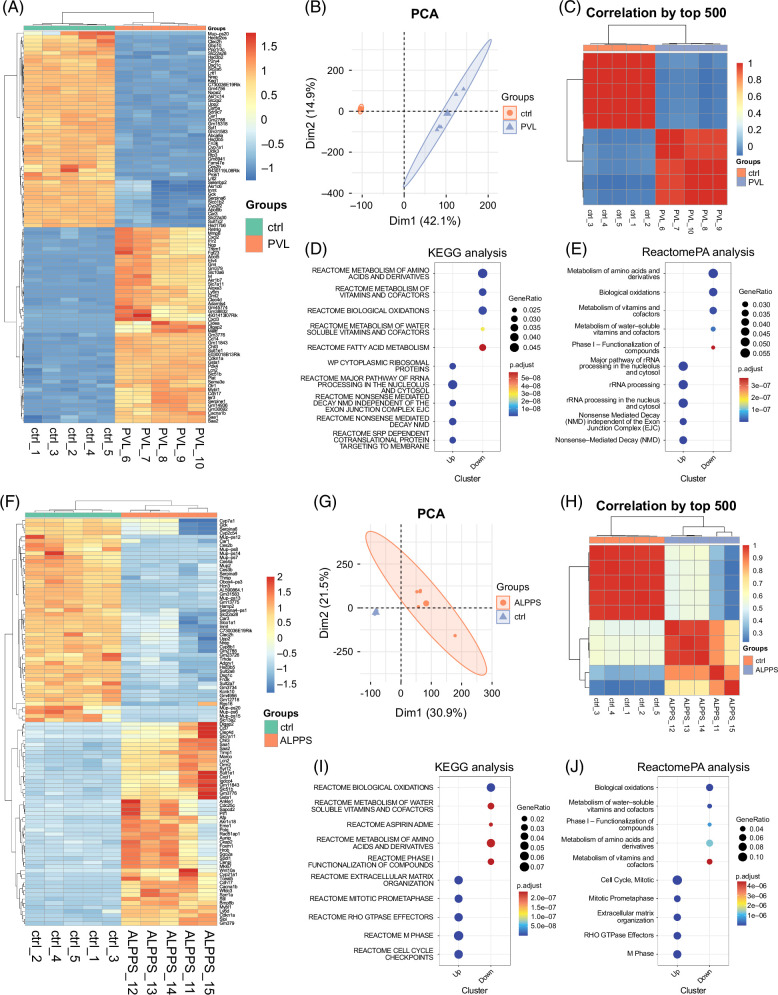

We tried to explore the changes in livers after the PVL surgery first. The differential analysis was performed between the PVL group and control group (Figure 2A and Supplemental Figure S1, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B883). Interestingly, we found that various ligands/cytokines and receptors were upregulated in mouse livers with PVL, including Cxcl2, Cxcl3, Cd14, Saa1, Saa2, and Il1r2 (Figure 2A), which might be attributed to the liver injury and the activation of the immune system. PCA and correlation analysis demonstrated the great changes in livers from PVL mice compared to those from sham mice (Figures 2B, C). Then, the KEGG and Reactome pathway databases were both adopted to perform function enrichment analyses (Figures 2D, E). Of interest, we could not obtain the pathway terms related to the proliferative ability of hepatocytes. It is obvious that the metabolism and biological oxidation of livers were largely distinct in the comparison of PVL mice with sham mice, hinting at the limited promotion of liver regeneration of the PVL surgery.

FIGURE 2.

Characteristics of liver regeneration between ALPPS and PVL based on RNA-seq analysis. (A) Heatmap shows the differentially expressed mRNAs (DEGs) between the ctrl (sham) and ALPPS model. (B) PCA based on RNA-seq data. Different colors indicate the different groups. (C) Correlation analysis of the 6 RNA-seq samples. The color represents the correlation coefficient between each sample. (D) KEGG enrichment analysis for DEGs (ALPPS versus ctrl). (E) Reactome pathway enrichment analysis for DEGs (ALPPS versus ctrl). (F) Heatmap shows the differentially expressed mRNAs (DEGs) between the ctrl (sham) and ALPPS model. (G) PCA based on RNA-seq data. Different colors indicate the different groups. (H) Correlation analysis of the six RNA-seq samples. The color represents the correlation coefficient between each sample. (I) KEGG enrichment analysis for DEGs (ALPPS versus ctrl). (J) Reactome pathway enrichment analysis for DEGs (ALPPS versus ctrl). Abbreviations: ALPPS, associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy; DEG, differentially expressed gene; PCA, principal component analysis.

Characteristics of liver regeneration after ALPPS

Since the PVL operation could not efficiently enhance the proliferative ability of hepatocytes, we further explored the biological changes of ALPPS operation (Figure S2, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B883). Consistent with the PVL surgery, various ligands/cytokines and receptors were upregulated in mouse livers with ALPPS, including Ccl7, Saa1, Saa2, Cxcl1, Macro, and Wnt10a (Figure 2A). However, we also found that ALPPS operation promotes the expression of Afp, Foxm1, and Mki67, the canonical biomarkers for cell proliferation (Figure 2F). Then, the PCA and correlation analysis demonstrated that the ALPPS group could be obviously separated from the sham group (Figures 2G, H). Moreover, KEGG and Reactome analyses showed that ALPPS not only regulated the pathways related to metabolisms and biological oxidations similar to PVL but also controlled the pathways involved in the “cell cycle” and “M phage” (Figures 2I, J). To sum up, ALPPS, not PVL, could promote hepatocytes into a proliferative state and promote liver regeneration.

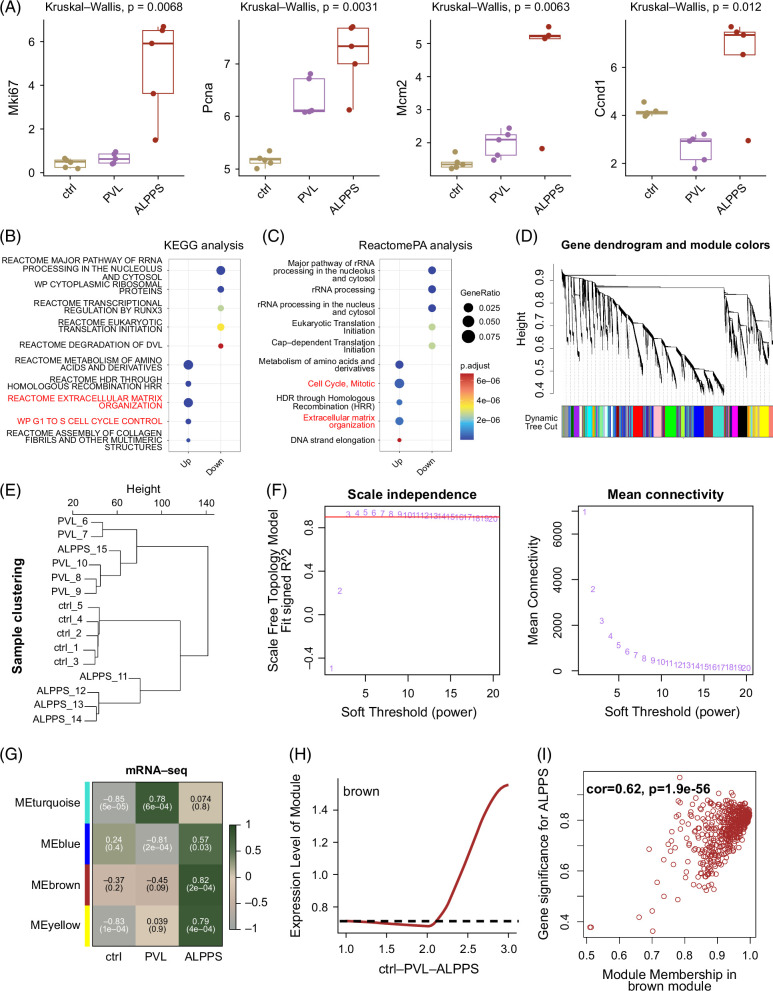

Comparison of ALPPS operation with PVL operation highlights the pro-proliferative possibility of ALPPS

To further compare the differences between the ALPPS operation and the PVL operation, we detected the gene expression of Mki67, Pcna, Mcm2, and Ccnd1 (Figure 3A). Intriguingly, all these proliferative genes were highly expressed in the ALPPS group rather than the PVL group. Again, we performed the enrichment analysis between the differentially expressed genes between ALPPS and PVL. Consistently, ALPPS could promote the activation of “cell cycle” and “extracellular matrix organization” pathways (Figures 3B, C). To further find out genes related to ALPPS, the WGCNA algorithm was utilized in all RNA-seq samples (Figures 3D–F). There were 4 obtained gene modules, including turquoise, blue, brown, and yellow modules (Figure 3G). Further, we found that the brown gene module was mainly activated in the ALPPS group (Figures 3H, I). Taken together, the brown gene module might be highly correlated to the biological characteristics of livers with ALPPS and ALPPS-dependent gene modules.

FIGURE 3.

Comparison of ALPPS operation with PVL operation. (A) Expression levels of several proliferative biomarkers, including Mki67, Pcna, Mcm2, and Ccnd1. (B) KEGG enrichment analysis for DEGs (ALPPS vs. PVL). (C) Reactome pathway enrichment analysis for DEGs (ALPPS vs. PVL). (D) WGCNA analysis for RNA-seq data. A gene dendrogram was performed. The color indicates different gene modules. (E) Clustering analysis of all sequenced samples. (F) Identification of soft threshold (power) for WGCNA pipeline. (G) Module-trait heatmap for identifying ALPPS-specific gene module. (H) The average module score of the brown module. (I) Correlation analysis between ALPPS and brown module. Abbreviations: ALPPS, associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy; DEG, differentially expressed gene; PVL, portal vein ligation; WGCNA, weighted gene co-expression network analysis.

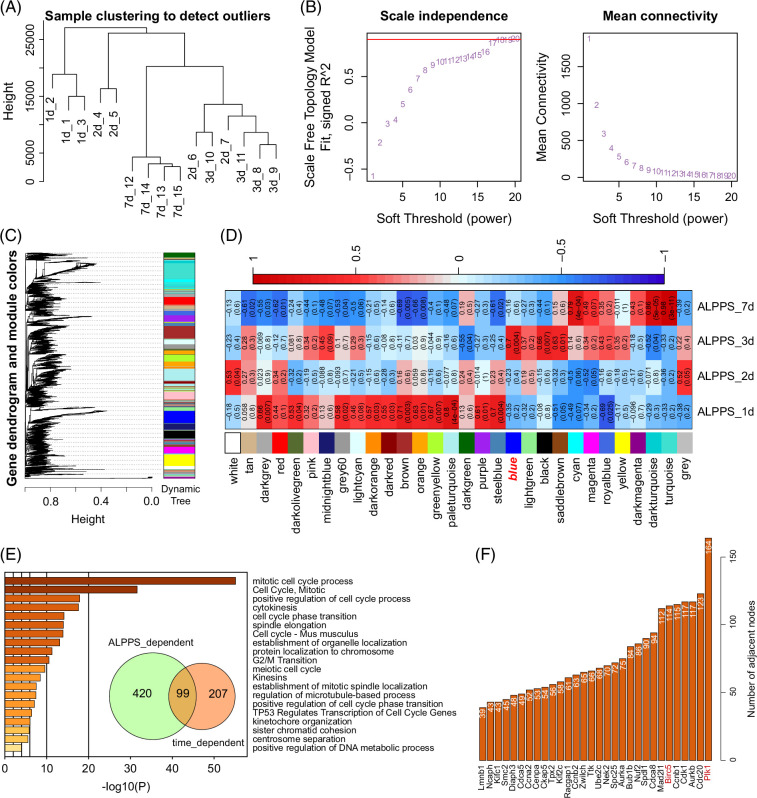

Exploration of time-dependent and ALPPS-dependent genes using WGCNA

To further obtain the time-dependent genes in livers during ALPPS surgery, transcriptomic sequencing (RNA-seq) on 1 day, 2 days, 3 days, and 7 days after ALPPS was conducted and analyzed using the WGCNA algorithm (Figures 4A–D). Clustering analysis of RNA-seq data indicated that liver samples on 7 days after ALPPS were quite different from those on 1 day, 2 days, and 3 days post ALPPS (Figure 4A). Then, based on the WGCNA pipeline, we obtained various gene modules (Figures 4B, C). Especially, the blue gene module was identified as the 3-day–dependent gene module (Figure 4D). Thus, we intersected the ALPPS-dependent gene module (brown module; compared to the control and PVL groups) and the time-dependent gene module (blue module; compared to 1 day, 2 days, and 7 days after ALPPS) (Figure 4E). Finally, 99 genes were overlapped and highly related to the proliferation- and cell-cycle- pathways, including “cell cycle, mitotic,” “G2/M transition,” and “TP53 regulates transcription of cell cycle genes” (Figure 4E). Then, we collected and ranked all the genes from the enriched pathways (Figure 4F). To better represent the potential proliferative signature of ALPPS, the top 30 genes were conserved, and others were removed. Of interest, polo-like kinase 1 (Plk1), an important regulator for cell mitosis,20 were ranked at the top with 164 related pathway terms, and Birc5 was also included, which had been highlighted in our previous study6 (Figure 4F).

FIGURE 4.

Exploration of time-dependent and ALPPS-dependent genes using WGCNA based on RNA-seq data. (A) Sample clustering analysis for liver tissues at 0 days, 1 day, 2 days, 3 days, and 7 days after ALPPS. (B) WGCNA pipeline for identifying time-dependent gene modules. Estimation of the suitable soft threshold for the time point RNA-seq data. (C) Gene dendrogram and module colors. Different colors indicate different gene modules. (D) Module-trait heatmap for identifying crucial gene modules for the most proliferative time point (ALPPS: 3 d). (E) Enrichment analysis for the 99 time-dependent and ALPPS-dependent genes. The Metascape web tool was utilized (https://metascape.org). (F) Ranking of the significant genes. Only the top 30 genes were shown. Abbreviations: ALPPS, associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy; WGCNA, weighted gene co-expression network analysis.

Validation of the signature30 of ALPPS in external datasets

To further confirm the prediction ability of the 30-gene signature, we adopted 6 external data sets related to liver regeneration after PHx for validation, including GSE180012, GSE158864, GSE167034, GSE215423, GSE83598, and GSE4528 (Supplemental Figure S4A, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B883). Concordantly, the 30-gene signature related to ALPPS was highly activated at the peak of regeneration time after PHx (Supplemental Figure S4A, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B883). Then, we also drew out the expression levels of the 30 genes in each data set, and the results showed that the expression patterns of all 30 genes were in concordance with the signature (Supplemental Figure S4B, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B883).

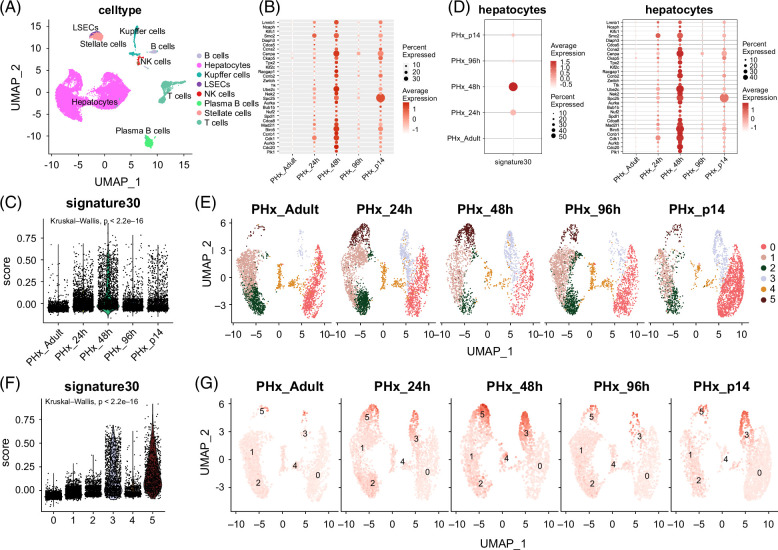

Single-cell RNA-seq analysis for verifying the proliferative characteristics of the 30-gene signature

To better verify the proliferative characteristics of the 30-gene signature in single-cell levels, liver scRNA-seq data related to adult (0 h), 24, 48, and 96 hours after PHx surgery and at the postnatal day 14 (P14, a midpoint between the neonatal period and weaning) were collected and used for downstream analysis (Figure 5A). After removing low-quality liver cells, we annotated the cell types (Figure 5A). Subsequently, the expression levels of all these 30 genes were detected in a pseudo-bulk of scRNA-seq data. Similarly, 30 genes were mostly higher expressed at 24 and 48 hours after PHx rather than at other time points (Figures 5B and 6C). In parallel, similar results were obtained in hepatocytes (Figure 5D).

FIGURE 5.

Single-cell RNA-seq analysis for verifying the proliferative characteristics of 30-gene signature. (A) Annotation of all cell types in scRNA-seq data. The GSE151309 data related to PHx were adopted. (B) Dotplot shows the expression levels of the 30 genes. (C) Signature score of scRNA-seq data. The signature score was estimated using the “AddModule” function in the Seurat package. (D) Dotplot displays the expression levels of the 30 genes in hepatocytes from GSE151309 data. (E) Clustering analysis of hepatocytes. (F) Violin plot shows the signature score of hepatocytes in scRNA-seq data. The signature score was estimated using the “AddModule” function in the Seurat package. (G) UMAP plot displays the signature score of hepatocytes in scRNA-seq data. Abbreviation: PHx, partial hepatectomy.

FIGURE 6.

MicroRNA-seq analysis for comparing difference hepatectomy procedures (PVL and ALPPS) for promoting liver regeneration. (A) PCA based on microRNA-seq data. (B) Volcano plots show the differentially expressed microRNAs. (C) Heatmaps show the clustering results of all microRNA-seq samples. (D) Heatmap plots the potential downregulated microRNAs in livers from PVL and ALPPS mice compared to ctrl (sham) mice. (E) Interaction of the potential microRNAs for regulating Plk1 based upon 3 databases (RNA22, miRWalk, and TargetMiner databases). (F) Interaction of the potential microRNAs for regulating Plk1 and also downregulated in livers from PVL and ALPPS mice compared to ctrl (sham) mice. Abbreviations: ALPPS, associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy; PCA, principal component analysis; Plk1, polo-like kinase 1; PVL, portal vein ligation.

Furthermore, we separated hepatocytes into 5 clusters using clustering analysis, and the harmony package was adopted to remove the batch effect between each sample (Figure 5E). Intriguingly, we found that the 30-gene signature was activated in clusters 3 and 5 (Figure 5F), whose cell counts were both upregulated at 24 and 48 hours after PHx, the proliferative time point of PHx (Figure 5G). Herein, the 30-gene signature could reflect the proliferative state of hepatocytes.

Signature30high hepatocytes indicated a higher proliferative state while Signature30low hepatocytes represented a higher metabolic and functional state

To better understand the features of the 30-gene signature in hepatocytes, we conducted the trajectory analysis for all hepatocytes. Unexpectedly, the livers at 24 and 48 hours after PHx were in the same branch of pseudotime trajectory while the livers at 0 hours (adult) and 96 hours after PHx were in the other branch (Supplemental Figures S4A–C, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B883). Then, the expression changes of 30 genes were also following the trajectory pseudotime (Supplemental Figure S4D, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B883). Therefore, the cell state and function will be shifted after hepatectomy.

To validate that the 30-gene signature could indicate the cell state of hepatocytes, we split the hepatocytes into signature30high hepatocytes and signature30low hepatocytes. Moreover, the cell-cell communication analysis was performed using the cellchat package (Supplemental Figure S4E, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B883). Intriguingly, signature30high hepatocytes had lower communication ability than signature30low hepatocytes, no matter the number of interactions or the interaction weights/strength (Supplemental Figures S4E–G, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B883).

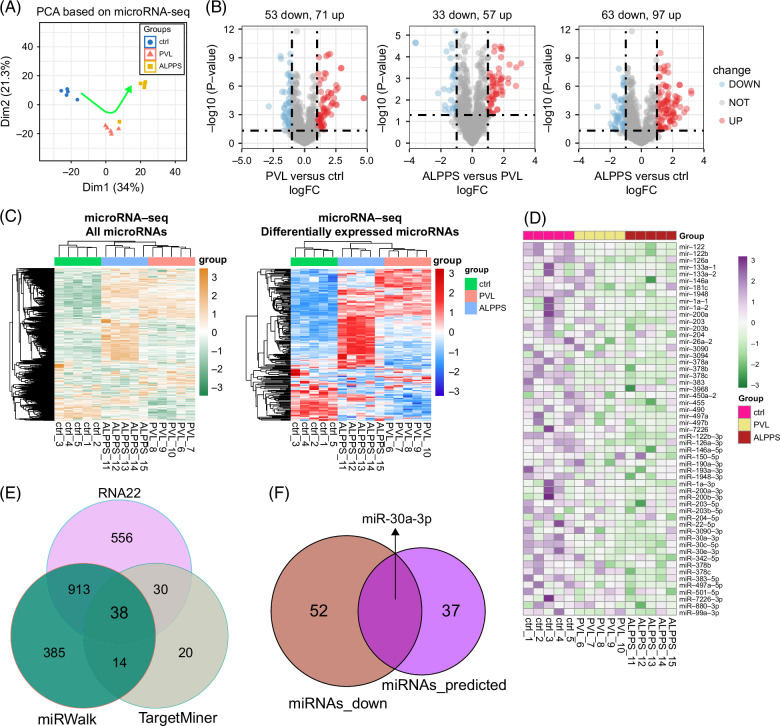

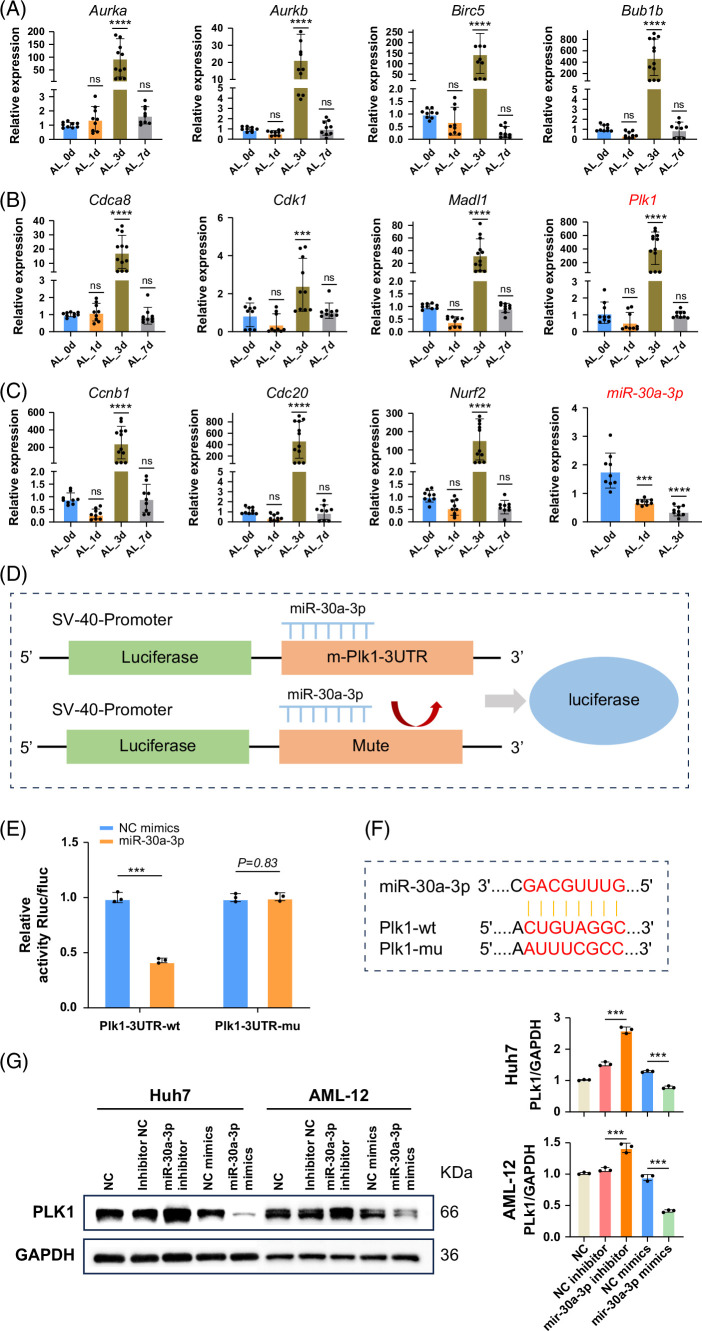

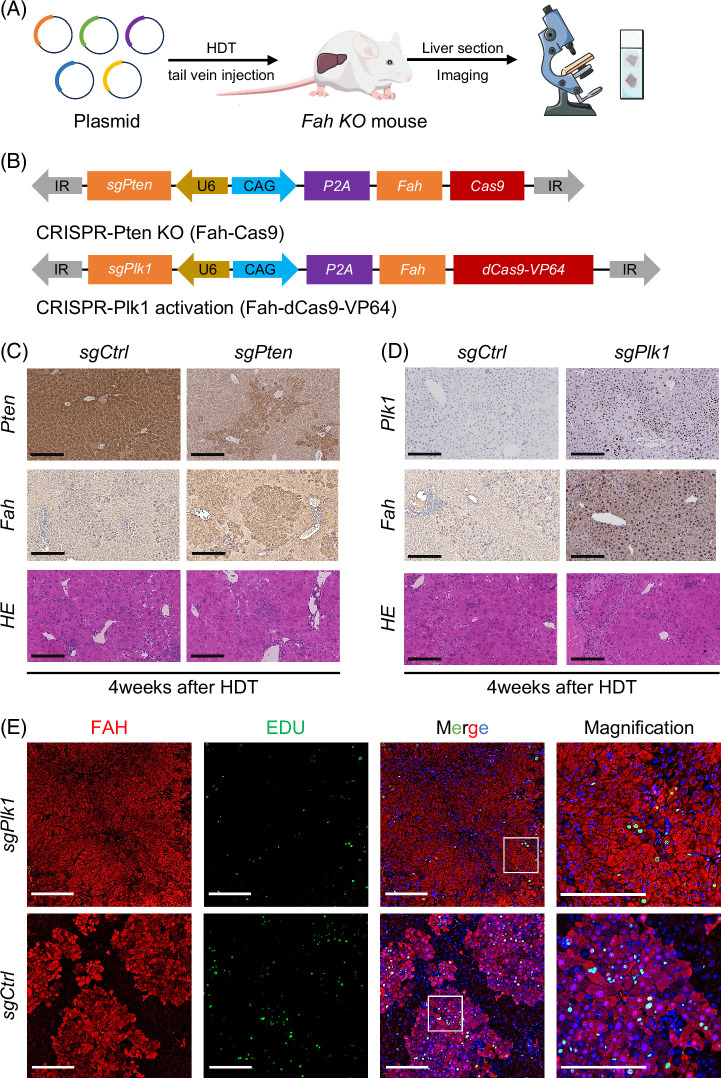

microRNA-seq analysis revealed the changes in microRNAs might also shift the cell state of hepatocytes

Then, to confirm that the cell state of hepatocytes was also regulated by small RNAs, microRNA-seq analysis was conducted on the livers of sham (ctrl), PVL, and ALPPS (Figure 6A). Based on PCA results of detected microRNAs, the 2 hepatectomy operations both regulated the cell state of hepatocytes. Then, a differential analysis of microRNAs was performed, and the results showed that ALPPS surgery had the most differentially expressed microRNAs (Figure 6B). Interestingly, the clustering analysis of all 15 samples based on all detected microRNAs or differentially expressed microRNAs showed that liver tissues from the ALPPS and PVL groups were more similar to each other compared to the control (sham) group (Figure 6C). These results indicated that microRNAs also participated in the liver regeneration process after hepatectomy. Considering that we had already highlighted a 30-gene signature for predicting hepatocyte proliferation during liver regeneration after ALPPS, it triggered us to further explore the relationship between the microRNA-seq data and this ALPPS-related signature. First, we selected the microRNAs (total number: 53) that were downregulated in livers after the PVL and ALPPS operations (Figure 6D) because the expression relationships between microRNAs and mRNAs were commonly converse. Then, Plk1 was ranked first in the signature (Figure 4G). Therefore, we tried to predict the potential microRNAs that could regulate the Plk1 using the RNA22, miRWalk, and TargetMiner databases (Figure 6E). There were 38 microRNAs identified as microRNAs targeting Plk1. Finally, we overlapped the 38 microRNAs with the 53 regeneration-related microRNAs. Interestingly, miR-30a-3p was left and might get involved in the expression changes of Plk1 (Figure 6F). Specifically, the downregulation of miR-30a-3p might lead to the upregulation of Plk1, promoting the hepatocytes into the proliferative state (Figure 6F). As aforementioned, the use of real-time PCR to amplify cDNA products reverse from mRNA was performed to study the abundance of gene expression of 30 genes (Figures 7A–C). The correlation between the 2 was further validated using a dual-luciferase reporter system (Figure 7E). To verify the regulatory role of microRNA on Plk1, we constructed systems for the overexpression and inhibition of microRNA in an in vitro system and assessed the protein expression (Figure 7G). To further investigate the potential role of PLk1 in liver regeneration, we conducted in vivo validation work using Fah KO mice and the Sleeping Beauty transposon system. By combining hydrodynamic injection with the Sleeping Beauty transposon (Figure 8B), we successfully reintroduced the Fah and made specific gene edits (Plk1 and Pten) in partial hepatocytes of Fah KO mice. Subsequently, during a 4-to-6-week in vivo regeneration, we observed distinct regulatory abilities in liver regeneration among hepatocytes with different gene edits. Consistent with the sequencing results, the activation of Plk1 and the knockout of Pten exhibited similar tendencies in promoting liver regeneration in Fah KO mice, which resulted in a higher proportion of FAH staining area (Figure 8C). Moreover, through in vivo injection of Edu-labeled proliferating hepatocytes, it was found that hepatocytes with gene edits demonstrated enhanced proliferation activity (Figure 8D).

FIGURE 7.

RT-PCR and dual-luciferase assays validated the interaction between Plk1 and miR-30a-3p. (A–C) We selected 11 in 30 gene databases that significantly altered regeneration-related genes for RT-PCR validation and observed significant upregulation of previously reported hepatocyte proliferation-related genes such as Cdk1 and Ccnb1 on day 3 after ALPPS. Similarly, Plk1 exhibited the same trend. In addition, a downregulation trend of miR-30a-3p was observed at this time point. Data are shown as means ± SEM. ***p < 0.001, ns = not statistically significant, compared to the Sham group, n = 9. (D) Schematic diagram of the dual-luciferase assay illustrating the binding interaction between miR-30a-3p and Plk1. (E) The dual-luciferase assay demonstrated the binding interaction between Plk1 and miR-30a-3p, which can be reversed by mutating the Plk1 binding site. Data are shown as means ± SEM. ***p < 0.001. NC mimics versus miR-30a-3p group, n = 3. (F) Predicted binding sites of miR-30a-3p for both wild-type and mutant Plk1. (G) The expression of Plk1 was evaluated in both the overexpression and inhibition systems. In vitro transfection of the Huh7 and AML-12 cell lines was performed to simulate the microRNA overexpression and inhibition systems. Western blot results demonstrated that the inhibition of microRNA significantly enhanced the expression of Plk1, whereas the overexpression of microRNA significantly reduced Plk1 expression. Data are shown as means ± SEM. ***p < 0.001. NC mimics versus miR-30a-3p mimics, inhibitor NC versus miR-30a-3p inhibitor group, n = 3. Abbreviations: ALPPS, associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy; NC, negative control; Plk1, polo-like kinase 1.

FIGURE 8.

In vivo CRISPR validation of Plk1’s ability to promote liver regeneration in Fah KO mice (A) Using in vivo transfection technology via HDT, Sleeping Beauty transposon-mediated CRISPR KO and CRISPRa systems can effectively delete and overexpress individual genes in the liver. (B) The transposon plasmid was employed to carry out Pten deletion, representing the CRISPR KO system, and activate Plk1 using the CRISPRa system. (C) Representative IHC staining revealed that PTEN deletion significantly increased the proliferation efficiency of FAH-positive hepatocytes compared to the control group. However, no significant differences were observed in liver lobule morphology with HE staining, scale bar = 200 μm, n = 3. (D) Immunohistochemical analysis indicated that the activation of PLK1 exhibited a positive impact on the proliferation of FAH-positive liver cells. Furthermore, HE staining did not detect any signs of hepatic lobule injury, scale bar = 200 μm, n = 3. (E) Representative immunofluorescence results revealed that the proportion of EDU-positive cells within the FAH-positive cell population was higher after PLk1 overexpression compared to the control group. This implies that FAH-positive cells exhibit a greater capacity for proliferation, scale bar = 200 μm, n = 3. Abbreviations: Fah KO, fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase knockout; HDT, hydrodynamic injection; IHC, immunohistochemical; KO, knockout; Plk1, polo-like kinase 1.

DISCUSSION

The human liver possesses a robust regenerative potential, capable of rapid proliferation within a mere 3 months to meet metabolic demands, which is critical for the recovery following the PHx for treating various liver diseases.21,22 However, for scenarios necessitating extended hepatectomy to preserve tumor margin integrity, it is crucial to ensure an adequate FLR. In recent years, the ALPPS procedure has emerged as a novel surgical strategy based on liver partitioning and PVL, particularly suitable for patients with insufficient residual liver volume undergoing tumor resection, and is considered one of the most groundbreaking approaches in the field of liver tumor surgery. However, several studies support the advantage of ALPPS in enhancing residual liver regeneration, showing that FLR hypertrophy and KGR (kinetic growth rate) are higher after ALPPS than after PVE.23,24,25,26 However, we also found that some literature suggests ALPPS does not have an “overwhelming” advantage in promoting liver regeneration.27,28 In addition, the degree of FLR hypertrophy following ALPPS is not unprecedented, as the KGR in the FLR from living donors can reach or even exceed the level seen after ALPPS.29 Overall, our work (Figure 1E) supports that ALPPS is significantly more effective than PVE in promoting liver regeneration.

By partially ligating the portal vein and dividing the median liver lobe in our preliminary study, we were able to construct the ALPPS surgical model in mice.1 Of note, the unique lobular structure of the mouse liver, along with its independent dual portal venous supply to the median liver lobe, ensures postoperative blood flow to the right median lobe. Based on the successful establishment of the ALPPS model in mice, we found that ALPPS increased liver regeneration rates compared with the PVL approach. However, the underlying mechanisms driving liver regeneration remain unclear. Thus, in this study, we simulated mouse liver regeneration and combined RNA-seq and miRNA-seq to reveal the patterns of gene regulation in physiological liver regeneration, slow liver regeneration, and rapid liver regeneration, highlighting that the Plk1-related signature can accurately predict changes in liver cell status during liver regeneration. Particularly, the 30-gene signature also included the Birc5 gene, which has been highlighted in our previous work.6 In this study, we pinpointed the potential pro-proliferative function of Plk1 during liver regeneration. Interestingly, both Plk1 and Birc5 had a crucial role in promoting autophagy and cell proliferation. 30,31 However, a deeper study of the role of Plk1 and Birc5 in hepatectomy still needs more validation. Moreover, a study has reported that ALPPS surgery enhances hepatocellular proliferation through the IHH-GLI1-CCND1 pathway.4 Consistently, the Ccnd1 gene was also found in our identified 30-gene signature, which also re-assured the reliability of the 30-gene proliferative signature based on sequence data of ALPPS surgery. To further validate the role of Plk1 in promoting liver regeneration in vivo, we chose Fah KO mice as the experimental model. In the context of liver recolonization, particularly through selective transdifferentiation-driven regeneration, it is crucial to emphasize the exceptional regenerative capacity of hepatocytes. The commonly used Fah-deficient mouse model supports this process, as Fah deficiency leads to hepatocyte death and liver failure, which can be reversed through transplantation of FAH-positive hepatocytes.32 In addition, using the Sleeping Beauty transposon and hydrodynamic injection transfection technology enables efficient in vivo transfection of the Fah gene, offering a novel approach to liver regeneration research in Fah KO mice.23 Previous studies have indicated that Fah mice demonstrate a robust preference for FAH-positive liver cells during cell transplantation, making them an optimal vehicle for in vivo liver regeneration processes.33 Leveraging the efficient and convenient CRISPR-Cas9 system, gene editing can be efficiently performed, offering a platform for subsequent high-throughput screening of liver-related genes in vivo.

There are various microRNAs proved to be crucial for cell proliferation. For example, a microRNA-related network was constructed for hepatic lineage maturation, underscoring a microRNA signature for regulating the development of hepatic lineage cells.34 A study showed that the upregulation of miR-30a-3p expression inhibits trophoblast cell proliferation.35 Here, we also found that miR-30a-3p was downregulated after ALPPS surgery. Parallelly, the reduction of miR-30a-3p might lead to elevated expression levels of Plk1, contributing to hepatocyte proliferation during hepatectomy.

This study has some potential limitations, including the lack of differences in liver regeneration in mice simulated under different physiological conditions after ALPPS. In clinical practice, patients undergoing ALPPS surgery often present with complex underlying conditions such as hepatitis, cirrhosis, or liver cancer, which markedly differ from the physiological status of the mice utilized in our research. Further experimental evidence is needed to determine whether the regulation of “miR-30a-3p/Plk1” promotes liver regeneration.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, our study revealed that ALPPS surgery could successfully promote liver regeneration by activating hepatocytes into a “cell cycle.” Through RNA-seq analysis using WGCNA, a Plk1-related 30-gene signature was identified to predict the cell state of hepatocytes. More than 5 external data sets were included for validation. ScRNA-seq analysis confirmed that signature30high hepatocytes had stronger proliferative ability than signature30low hepatocytes. Using microRNA-seq analysis, we identified 53 microRNAs that were time-dependently reduced after ALPPS. Particularly worth mentioning is that the miR-30a-3p might be able to regulate the expression of Plk1, contributing to the liver regeneration of ALPPS.

Supplementary Material

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data supporting the research findings can be found in the main text and supplemental manuscript. The RNA sequencing experiments are available from the GEO database (https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo), and the information is listed in Supplemental Table S1, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B882.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Yuan Du and JunXiang Yin supervised the whole study, wrote and finally approved the manuscript, and provided financial support. Yuan Du conducted an overall analysis of the databases, designed the study, and prepared and revised every version of the manuscript. YiHan Yang developed the bioinformatic analysis methods together with YiPeng Zhang. YiHan Yang prepared and conducted all in vivo experiments. FuYang Zhang and JunJun Wu collected all liver samples and image staining.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Zhu Hao Laboratory at UTSW for their generous provision of the plasmid, as well as to Dr Jia for their meticulous guidance throughout the in vivo experimental process. Duyuan would like to express his heartfelt gratitude to his wife, Ms Jian Shuqin, for her support for his work. He also wants to thank his newly born daughter, Du Jinyi, during this submission period. It has been a challenging yet joyful time. He hopes to include this in the acknowledgment section as a commemoration of her birth and wishes her health and happiness in the days to come. All authors acknowledged all the researchers for the open-access data sets used in the present study.

FUNDING INFORMATION

No funding was received for this work.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts to report.

Footnotes

Yuan Du and YiHan Yang contributed equally to this work.

Abbreviations: ALPPS, associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy; Fah KO, fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase knockout; FLR, future liver remnant; GEO, Gene Expression Omnibus; PCA, principal component analysis; PHx, partial hepatectomy; PVE, portal vein embolization; PVL, portal vein ligation; WGCNA, weighted gene sco-expression network analysis.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's website, www.hepcommjournal.com.

Contributor Information

Yuan Du, Email: 361439920013@email.ncu.edu.cn.

YiHan Yang, Email: 1742752186@qq.com.

YiPeng Zhang, Email: dlkflyzxkx@163.com.

FuYang Zhang, Email: 403634545@qq.com.

JunJun Wu, Email: 1163995925@qq.com.

JunXiang Yin, Email: m15180162907@163.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hu C, Xu Z, Du Y. A mouse model of the associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy procedure aided by microscopy. J Vis Exp. 2024. doi:10.3791/66098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chapelle T, Op de Beeck B, Driessen A, Roeyen G, Bracke B, Hartman V, et al. Estimation of the future remnant liver function is a better tool to predict post-hepatectomy liver failure than platelet-based liver scores. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43:2277–2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Isfordink CJ, Samim M, Braat M, Almalki AM, Hagendoorn J, Borel Rinkes IHM, et al. Portal vein ligation versus portal vein embolization for induction of hypertrophy of the future liver remnant: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Oncol. 2017;26:257–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Langiewicz M, Graf R, Humar B, Clavien PA. JNK1 induces hedgehog signaling from stellate cells to accelerate liver regeneration in mice. J Hepatol. 2018;69:666–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Linecker M, Bjornsson B, Stavrou GA, Oldhafer KJ, Lurje G, Neumann U, et al. Risk adjustment in ALPPS is associated with a dramatic decrease in early mortality and morbidity. Ann Surg. 2017;266:779–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du Y, Jian S, Wang X, Yang C, Qiu H, Fang K, et al. Machine learning and single cell RNA sequencing analysis identifies regeneration-related hepatocytes and highlights a Birc5-related model for identifying cell proliferative ability. Aging (Albany NY). 2023;15:5007–5031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jia Y, Li L, Lin YH, Gopal P, Shen S, Zhou K, et al. In vivo CRISPR screening identifies BAZ2 chromatin remodelers as druggable regulators of mammalian liver regeneration. Cell Stem Cell. 2022;29:372–385 e378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenblum D, Gutkin A, Kedmi R, Ramishetti S, Veiga N, Jacobi AM, et al. CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing using targeted lipid nanoparticles for cancer therapy. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eabc9450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. Testing significance relative to a fold-change threshold is a TREAT. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:765–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Langfelder P, Horvath S. WGCNA: An R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanzelmann S, Castelo R, Guinney J. GSVA: Gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y, He QY. clusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS. 2012;16:284–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chembazhi UV, Bangru S, Hernaez M, Kalsotra A. Cellular plasticity balances the metabolic and proliferation dynamics of a regenerating liver. Genome Res. 2021;31:576–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hao Y, Hao S, Andersen-Nissen E, Mauck WM, 3rd, Zheng S, Butler A, et al. Integrated analysis of multimodal single-cell data. Cell. 2021;184:3573–3587 e3529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trapnell C, Cacchiarelli D, Grimsby J, Pokharel P, Li S, Morse M, et al. The dynamics and regulators of cell fate decisions are revealed by pseudotemporal ordering of single cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:381–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin S, Guerrero-Juarez CF, Zhang L, Chang I, Ramos R, Kuan CH, et al. Inference and analysis of cell-cell communication using CellChat. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miranda KC, Huynh T, Tay Y, Ang YS, Tam WL, Thomson AM, et al. A pattern-based method for the identification of microRNA binding sites and their corresponding heteroduplexes. Cell. 2006;126:1203–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sticht C, De La Torre C, Parveen A, Gretz N. miRWalk: An online resource for prediction of microRNA binding sites. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0206239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bandyopadhyay S, Mitra R. TargetMiner: MicroRNA target prediction with systematic identification of tissue-specific negative examples. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2625–2631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Carcer G, Manning G, Malumbres M. From Plk1 to Plk5: Functional evolution of polo-like kinases. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:2255–2262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Forbes SJ, Newsome PN. Liver regeneration—Mechanisms and models to clinical application. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13:473–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michalopoulos GK. Liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy: Critical analysis of mechanistic dilemmas. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:2–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zwirner S, Abu Rmilah AA, Klotz S, Pfaffenroth B, Kloevekorn P, Moschopoulou AA, et al. First-in-class MKK4 inhibitors enhance liver regeneration and prevent liver failure. Cell. 2024;187:1666–1684 e1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schlegel A, Lesurtel M, Melloul E, Limani P, Tschuor C, Graf R, et al. ALPPS: From human to mice highlighting accelerated and novel mechanisms of liver regeneration. Ann Surg. 2014;260:839–846; discussion 846–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garcia-Perez R, Revilla-Nuin B, Martinez CM, Bernabe-Garcia A, Baroja Mazo A, Parrilla Paricio P. Associated liver partition and portal vein ligation (ALPPS) vs selective portal vein ligation (PVL) for staged hepatectomy in a rat model. Similar regenerative response? PLoS One. 2015;10:e0144096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi JH, Hammarstrom C, Grzyb K, Line PD. Experimental evaluation of liver regeneration patterns and liver function following ALPPS. BJS Open. 2017;1:84–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gavriilidis P, Sutcliffe RP, Roberts KJ, Pai M, Spalding D, Habib N, et al. No difference in mortality among ALPPS, two-staged hepatectomy, and portal vein embolization/ligation: A systematic review by updated traditional and network meta-analyses. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2020;19:411–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.He X, Zhang Y, Ma P, Mou Z, Wang W, Yu K, et al. Extreme hepatectomy with modified ALPPS in a rat model: Gradual portal vein restriction associated with hepatic artery restriction. BMC Surg. 2023;23:291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Croome KP, Hernandez-Alejandro R, Parker M, Heimbach J, Rosen C, Nagorney DM. Is the liver kinetic growth rate in ALPPS unprecedented when compared with PVE and living donor liver transplant? A multicentre analysis. HPB (Oxford). 2015;17:477–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yin L, Wang Y, Lin Y, Yu G, Xia Q. Explorative analysis of the gene expression profile during liver regeneration of mouse: A microarray-based study. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2019;47:1113–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iliaki S, Beyaert R, Afonina IS. Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) signaling in cancer and beyond. Biochem Pharmacol. 2021;193:114747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Overturf K, Al-Dhalimy M, Tanguay R, Brantly M, Ou CN, Finegold M, et al. Hepatocytes corrected by gene therapy are selected in vivo in a murine model of hereditary tyrosinaemia type I. Nat Genet. 1996;12:266–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grompe M, Lindstedt S, al-Dhalimy M, Kennaway NG, Papaconstantinou J, Torres-Ramos CA, et al. Pharmacological correction of neonatal lethal hepatic dysfunction in a murine model of hereditary tyrosinaemia type I. Nat Genet. 1995;10:453–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang X, Zhang W, Yang Y, Wang J, Qiu H, Liao L, et al. A microRNA-based network provides potential predictive signatures and reveals the crucial role of PI3K/AKT signaling for hepatic lineage maturation. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:670059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Y, Wang L, Yu X, Gong W. MiR-30a-3p targeting FLT1 modulates trophoblast cell proliferation in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Horm Metab Res. 2022;54:633–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]