Highlights

-

•

The effects of prenatal endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) exposure were studied.

-

•

Prenatal exposure to EDCs associated with lower intelligence scores in adolescents.

-

•

Higher EDCs exposure associated with altered adolescent brain morphometry.

-

•

Neural fiber connectivity mediated prenatal EDCs exposure effects on intelligence.

-

•

Long-lasting brain-behavioral consequences of prenatal exposure to EDCs identified.

Keywords: Phthalic acid esters (PAE), Perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), Diffusion kurtosis imaging (DKI) and Neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging (NODDI), Intelligence quotient (IQ), Mediation analysis

Abstract

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and phthalic acid esters (PAEs) are well-known endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) that potentially affect child neurodevelopment. We aimed to investigate the effects of prenatal exposure to PFAS and PAEs on macro- and micro-structural brain development and intelligence in adolescents using multimodal neuroimaging techniques. We employed structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and various diffusion MRI techniques, including diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), diffusion kurtosis imaging (DKI), and neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging (NODDI), to assess the gray-matter macrostructure and white-matter microstructural integrity and complexity. Participants were drawn from a birth cohort of 52 mother–child pairs in central Taiwan recruited in 2001, and the adolescent intelligence quotient (IQ) scores were assessed using the Wechsler Intelligence Scale. Nine PFAS concentrations of cord blood and maternal serum samples were obtained from the children’s mothers during the third trimester of pregnancy (27–40 weeks) using a liquid chromatography system coupled to a triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer, while maternal urinary phthalates were used to evaluate PAEs exposure. Our results showed significant associations between prenatal exposure to PFAS and phthalates with changes in specific fronto-parietal regions of the adolescent male brain, including reduced cortical thickness in the inferior frontal gyrus and right superior parietal cortex, which are involved in language, memory, and executive function. A dose–response association was observed, with higher levels of PFAS and PAE exposure modulating altered white-matter fiber integrity in the superior cerebellar peduncle and inferior cerebellar peduncle of the male and female adolescent brains. In addition, higher levels of prenatal exposure to EDCs were associated with lower IQ scores in adolescents. Mediation analyses further revealed that white-matter microstructure of inter-hemispheric and cerebellar fibers mediated the association between prenatal EDC exposure and adolescent IQ scores in female adolescents. Our multimodal human neuroimaging findings suggest that prenatal exposure to EDCs may have long-lasting effects on neuroanatomical development, neural fiber connectivity, and intelligence in adolescents, and highlight the importance of using advanced diffusion imaging techniques, including DKI and NODDI, to detect neurodevelopmental changes and their brain-behavioral consequences with the risks associated with these environmental exposures.

1. Introduction

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) are exogenous substances or mixtures in the environment, food sources, and manufactured products that alter functions of the endocrine system and its interactive effects of multiple physiological systems. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and phthalic acid esters (PAEs) have been identified as two significant EDCs which are widely present in the environment. Human exposure to these chemicals is primarily through food, drinking water, and air (Benjamin et al., 2017). For example, PFASs, known for their heat resistance and chemical stability, are found in furniture, carpets, food packaging, and cooking utensils (Fromme et al., 2009, Lau et al., 2003). Phthalates, widely used as plasticizers, can be found in hygiene products, cosmetics, medical devices, and pharmaceuticals, contributing to exposure through inhalation, ingestion, or dermal absorption (Hsieh et al., 2019, Koch et al., 2013, Wittassek and Angerer, 2008). There is clear evidence that prenatal exposure to PFASs, phthalates, and other EDCs may impact fetal brain development and indirectly affect the psychological and behavioral development of children, elucidating the links between endocrine disruptors and neurodevelopment (Braun et al., 2017, Miguel et al., 2019, Schug et al., 2015). Moreover, the effects of prenatal EDC exposure may persist into adulthood, leading to long-term health issues such as cardiovascular diseases, neurodegenerative diseases, cancer, reproductive system disorders, and diabetes. These effects often depend on the dosage, duration, and timing of exposure during pregnancy, as well as genetic susceptibility (De Felice et al., 2015, Murphy et al., 2017, Thapar et al., 2013, Yi et al., 2022).

PFASs are commonly used synthetic chemicals in the various commercial and industrial products. More than three thousand PFASs are utilized worldwide (Wang et al., 2017). PFASs are composed of multiple carbon–fluorine bonds with high chemical and thermal stability, strength, and durability (Buck et al., 2011). The health concerns for PFAS exposure are due to their bioaccumulation and persistence (Cousins et al., 2020). The adverse neurodevelopmental effects of PFASs exposure in children have been observed. Harris et al. (2018) reported that prenatal and childhood PFAS exposure was associated with lower visual motor abilities in childhood (Harris et al., 2018). Zhou et al. (2023) found that prenatal mixture PFAS exposure was associated with a decrease in communication domain scores in 6-month-old infants (Zhou et al., 2023). Prenatal exposure to perfluorobutanesulfonate was reported to be negatively associated with the developmental quotient of gross motor in infancy (Yao et al., 2022). Zhang et al. (2024) observed that increased prenatal exposure to PFASs negatively affected the intelligence quotient (IQ) of school-aged children (Zhang et al., 2024). We have also previously shown that prenatal exposure to perfluoroundecanoic acid (PFUnDA) and perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA) was associated with the reduced IQ scores and impaired neurocognitive performance in children (Wang et al., 2015). Recent results of ECHO (Environmental influences on Child Health Outcomes) study showed PFNA as the strongest and most consistent associated with increased risk for autism among the 14 PFAS studied (Ames et al., 2023). Thereby the present investigation aimed at evaluating brain white matter integrity in relation to PFASs.

Advanced non-invasive magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques, encompassing anatomical, functional, and diffusion imaging, have been extensively utilized to explore the neuroanatomical development, neural connectivity, and functional dynamics of the brain. By integrating these multimodal approaches, researchers can achieve a comprehensive understanding of brain structure, the organization and directionality of neural fibers, and their interplay in neurobiological mechanisms, providing critical insights into both typical and atypical brain development (Fox and Raichle, 2007, Giedd et al., 1999, Jones et al., 2013, Luo et al., 2022). Anatomical MRI technique is a common MRI approach to measure the cortical thickness and surface area, as well as to quantify brain volume and neuronal density of the human brain, providing structural information about the process of brain development and the relationship between brain structure and function (Levman et al., 2017, Shaw et al., 2006, Vijayakumar et al., 2016). In contrast, diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) is an MRI-based brain imaging technique that is widely used to measure the structural integrity of white matter (WM) tracts by visualizing the diffusion properties of water in the brain (Cox et al., 2016, Fan et al., 2019, Yang et al., 2016). By using DTI, Fractional anisotropy (FA) is often used as a metric to measure the overall tissue structure of white matter fiber bundles, while mean diffusivity (MD) and axial diffusivity (AD) reflect changes in cell membrane integrity or cell density, and radial diffusivity (RD) is used to reflect the state of myelin sheaths (Beaulieu, 2002). Many studies have found associations between DTI metrices, and different stages of brain development (Bava et al., 2010, Lebel et al., 2008). Previous studies also showed the evidence that DTI metrices associated with cognitive and behavioral changes across the human lifespan (Cox et al., 2016, Fan et al., 2019). For example, some studies have found that FA values are related to the development of language abilities, memory, and learning abilities. Other studies also revealed the associations between micro-structural changes in MD, AD, and RD and cognitive functions such as attention, working memory, and emotional control in the developing brain of children and adolescence (Schmithorst et al., 2005, Tamnes et al., 2010).

The advanced diffusion models, diffusion kurtosis imaging (DKI) and neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging (NODDI), have been recently developed to estimate the microstructural complexity of dendrites and axons in vivo (Jensen et al., 2005, Zhang et al., 2012). Changes in DKI parameters in the brain's white matter or neural fiber bundles has been evidenced to detect the subtle changes in various biophysical features during neurodevelopment, including neural cell growth and differentiation, changes in the volume and shape of neural fibers, and changes in connections and communication between neural cells (Shi et al., 2019). Despite some inconsistent NODDI findings on neurodevelopmental trajectories, recent studies have shown a close relationship between NODDI parameters and neurodevelopment (Dimond et al., 2020, Kelly et al., 2016, Mah et al., 2017, Pines et al., 2020, Young et al., 2019). For example, one study found that NODDI parameters such as intracellular volume fraction (ICVF) showed stronger correlations with age than conventional DTI measures such as fractional anisotropy (FA), suggesting that NODDI may provide more sensitive insights into age-related changes in brain microstructure (Pines et al., 2020). Another reported diffusion MRI study using NODDI found that changes in cortical folding in children with developmental reading disorders were associated with abnormal morphology of neural prominences, which may reflect differences in synaptic pruning (Caverzasi et al., 2018). Furthermore, other studies have emphasized the importance of using diffusion MRI techniques to better understand microstructural changes in white matter during maturation, suggesting a potential relationship between NODDI parameters and the development of white matter in the brain (Lebel & Deoni, 2018). A recent study found that boys with Sensory Processing Dysfunction (SPD) and co-occurring Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) had significant reductions in the neurite density index (NDI), particularly in the projection tracts of the internal capsule and the commissural fibers of the splenium of the corpus callosum. These microstructural differences were not fully captured by Fractional Anisotropy (FA) alone, suggesting that NODDI parameters may be more sensitive and may be associated with specific neurodevelopmental disorders (Mark et al., 2023).

A few structural and diffusion MRI studies have been reported to investigate the associations of prenatal exposures to PFAS and PAEs with brain development (England-Mason et al., 2020, Ghassabian et al., 2023, Shen et al., 2021). A recent structural MRI study reported an association between maternal mono-ethyl phthalate (MEP) concentrations with total brain volumes, suggesting a global impact of prenatal EDCs exposure on brain volume (Ghassabian et al., 2023). Shen et al. also reported that prenatal PFAS exposure was associated with reduced brain volume in the frontal lobe and cerebellum in adolescents (Shen et al., 2021). Another neuroimaging study using DTI technique showed the differential effects of prenatal phthalates exposure on white matter fiber bundles, with higher phthalates levels correlating with decreased FA values in the left inferior longitudinal fasciculus and increased MD values in the right inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus (England-Mason et al., 2020). Although the results are inconclusive, these neuroimaging findings suggest that the prenatal exposure to EDCs (i.e., PFAS and PAEs) may affect neurodevelopment with global and regional brain structural changes (Cajachagua-Torres et al., 2024).

The present study aims to investigate whether and how maternal exposure to PFAS and phthalates affects brain development and intelligence in adolescents using multimodal neuroimaging techniques, including structural MRI, conventional DTI techniques, and advanced DKI and NODDI models. Given the previous findings that prenatal exposure to EDCs may result in neurodevelopmental deficits, we hypothesized that prenatal exposure to these EDCs would modulate the developmental trajectory of brain neuroanatomy and the microstructure of neural fiber bundles, leading to individual differences in neurocognitive changes.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

Participants for this study were drawn from an existing cohort conducted in 2001 in central Taiwan, mother–child pairs followed when children aged 14–15 years were recruited. After obtained informed consent from adolescents and their parents or main caretakers, they would fill out a questionnaire. Brain imaging was performed using multimodal MRI techniques (i.e., structural and diffusion MRI) to assess neurodevelopmental changes at an authorized hospital. The adolescent intelligence was assessed using the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Fourth Edition (WISC-IV) Full-Scale Intelligence Quotient (IQ) scores (Wechsler & Kodama, 1949). Maternal blood samples collected in the third trimester of pregnancy were used to assess prenatal exposure to the aforementioned chemicals. The research adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines and received approval from the Ethics Review Committee of the Chung Shan Medical University Hospital and the National Health Research Institutes in Taiwan.

2.2. Questionnaires

Structured questionnaires were completed by mothers in their third trimester of pregnancy. Birth outcomes (such as, gestational age, birth weight, birth length) were obtained and recorded by nurses at childbirth. Adolescents or their primary caretakers also filled out the questionnaires during the follow-up visit at ages 14 to 15 years. Questionnaires were used to gather data on basic demographics (such as sex, age, height, weight, maternal age at childbirth, parental education, family income, and so on), lifestyle (i.e. dietary habits, exercise habits, and smoking status), and medical history.

2.3. Edcs measurements

To assess prenatal exposure to a wide range of chemical compounds, we obtained urine and/or serum samples from pregnant women during their third trimester. These compounds included concentrations of seven perfluorinated compounds in cord blood and maternal serum and levels of seven phthalate metabolites in maternal urine.

2.3.1. Measurement of PFASs

We used an Agilent-1200 high performance liquid chromatography system (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA, USA) coupled with a triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer (Scitex API 4000, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) to detect plasma concentrations of nine PFASs in cord blood. There were, perfluorohexanesulfonic acid (PFHxS), perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), PFNA, perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), perfluorodecanoic acid (PFDeA), perfluoroundecanoic acid (PFUA), and perfluorododecanoic acid (PFDoA). The analytical method was described in detail in a previous study (Lien et al., 2011, Lin et al., 2013). The limit of quantitation values (LOQ) for nine PFASs were 0.08, 0.45, 0.10, 0.11, 0.19, 0.13, and 0.07 ng/mL for PFHxS, PFOA, PFNA, PFOS, PFDeA, PFUA, and PFDoA, respectively. The plasma concentrations of PFASs below the LOQ were replaced with half of LOQ.

2.3.2. Measurement of urinary phthalate metabolites

Urinary monoesters are the major metabolites of phthalates excreted in urine and are frequently utilized as indicators of internal exposure. In this study, we measured seven urinary phthalate metabolites of the five most commonly used phthalates using quantitative liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), as previously described in detail (Lin et al., 2011). These metabolites included mono-ethyl phthalate (MEP) for diethyl phthalate (DEP), mono-methyl phthalate (MMP) for dimethyl phthalate (DMP), mono-n-butyl phthalate (MBP) for di-n-butyl phthalate (DnBP), mono-benzyl phthalate (MBzP) for benzyl butyl phthalate (MBzP), and mono-2-ethylhexyl phthalate (MEHP), mono-2-ethyl-5-hydroxyhexyl phthalate (MEHHP) and mono- 2-ethyl-5-oxohexyl phthalate (MEOHP) for di-2-ethyl-hexyl phthalate (DEHP). The limit of detection (LOD) value of phthalate metabolites was 0.55, 0.23, 0.26, 0.99, 1.6, 3.4, and 2.2 μg/mL for MEHP, MEHHP, MEOHP, MBzP, MnBP, MMP, and MEP, respectively. Urinary phthalate metabolite levels below the LOD were replaced with a half of LOD value.

Measured phthalate metabolite levels were divided on the basis of urinary creatinine levels for urinary volume correction and expressed as “μg/g creatinine” in the statistical analysis. The creatinine levels were assessed by a spectrophotometric method at Kaohsiung Medical University Chung-Ho Memorial Hospital. The sum of DEHP metabolite levels (DEHP) (nmol/g creatinine) was estimated as the sum of MEHP, MEHHP, and MEOHP.

2.4. MRI image acquisition

All participants underwent a whole-brain anatomical T1-weighted images and diffusion-weighted scan acquired using a 20-channel head coil on the 3 T MRI scanner (Skyra, Siemens, Germany). The 3D T1-weighted images were obtained using a magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo (MPRAGE) sequence with the following parameters: matrix 256 × 256; 160 slices; 1 mm in plane resolution, slice thickness = 1 mm; TE/TR = 2.27/2500 ms; TI = 902 ms; flip angle = 8◦. Diffusion-weighted images were acquired using spin echo echo-planar imaging (SE-EPI), with TE/TR = 97/4800 ms; 128 × 128 acquisition matrix and 35 slices; voxel size (resolution) = 2 × 2 × 4 mm3; 64 isotopically distributed orientations for the diffusion weighted gradient at b-value = 1000, 1500, 2000 s/mm2, and 12b = 0 s/mm2 images.

2.5. Structural and diffusion MRI images processing

Each participant's anatomical T1 images were processed using FreeSurfer (Version 6) automated neuroanatomical segmentation software (Fischl, 2012). Cortical thickness and surface area values were determined using the recon-all script on each T1-weighted scan. The processing includes motion correction, the removal of non-brain tissue, intensity normalization, applied affine transformation to Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space, Talairach alignment, who brain segmentation, cortical surface reconstruction and the cerebral cortex parcellation. After automated segmentation, all images were visually inspected for accuracy and quality control by trained medical imaging scientists. Removal of non-brain tissue was performed using FSL's bet, and the recon-all scripts were re-run if the output of the images appeared abnormal. The cortical thickness is estimated by finding the shortest path between each vertex of the white matter surface and the grey matter surface. At last, we estimate the cortical thickness as the average of these two distances. Mean Surface areas and mean cortical thicknesses in each region of interest (ROI) of FreeSurfer's atlas were obtained from FreeSurfer's output *.aparc.stats files. Diffusion weighted images were first denoised by using Marchenko-Pastur principal component analysis (MP-PCA) denoising (Veraart et al., 2016). Gibbs-ringing artifact was eliminated by using the method of local subvoxel-shifts proposed by Kellner et al. (Kellner et al., 2016). Eddy current induced distortion and motion artifacts were corrected by FSL's eddy (Andersson and Sotiropoulos, 2015, Andersson and Sotiropoulos, 2016).

The diffusion tensors were estimated from the single-shell DWI data (b = 1000 s/mm2) using a linear fitting algorithm. Tensor-derived matrices − including fractional anisotropy (FA) and mean diffusivity (MD) − were calculated using DTI Fit (Basser et al., 1994). In addition, multi-shell DWI data (b-values = 1000, 1500, 2000 s/mm2) were used to fit the DKI and NODDI models. Diffusion Kurtosis Imaging (DKI) metrics, including mean kurtosis (MK), axial kurtosis (AK) and radial kurtosis (RK), were estimated using the DIPY toolkit (https://dipy.org/) (Chang et al., 2005, Garyfallidis et al., 2014, Jensen et al., 2005, Tabesh et al., 2011). NODDI maps, including free water fraction (FWF), neurite density index (NDI) and orientation dispersion index (ODI) were computed using the AMICO software package (https://github.com/daducci/AMICO) (Daducci et al., 2015, Zhang et al., 2012).

2.6. Tractography and segmentation

To identify the neural fiber tracts associated with EDC exposure, we employed TractSeg, a tool designed for the precise segmentation of white matter bundles from diffusion MRI data (https://github.com/MIC-DKFZ/TractSeg) (Wasserthal et al., 2018a, Wasserthal et al., 2018b). TractSeg employs a supervised learning method rooted in a convolutional neural network. This allows for the segmentation of specific tracts directly within the fiber orientation distribution function (FOD) map, eliminating the need for parcellation (Wasserthal et al., 2020, Wasserthal et al., 2021, Wasserthal et al., 2019, Wasserthal et al., 2018b). This approach has been successfully applied in several diffusion studies and has been shown to be both practical and effective for analysing brain anatomy and pathology, including in patients with neurodegenerative diseases and psychiatric disorders (Qiu et al., 2023, Wasserthal et al., 2021).

Following the tract segmentation procedure outlined by Dewenter et al. (Dewenter et al., 2023), we generated whole-brain FOD maps for all subjects using the multi-shell, multi-tissue constrained spherical deconvolution (MSMT-CSD) technique (Jeurissen et al., 2014). A study-specific FOD template was created by averaging the FODs across all participants. Spatial normalization was performed using a symmetric diffeomorphic non-linear transformation, and the transformation matrix was applied to other diffusion indices to align them to the template space. Finally, using the segmented tractography masks, we calculated along-tract mean diffusion indices for 72 white matter tracts within the template space.

2.7. Statistical analysis

2.7.1. Demographic statistic

Statistical analyses were carried out using Statistical Product and Service Solutions (IBM SPSS Statistics Version 20.0. Armonk, NY and JMP version 13.0. SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Group differences between continuous variables (e.g., age) were analysed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, and the group differences between categorical variables (e.g., sex) were analysed using the chi-square test. A p-value of < 0.05 in two-sided test was considered statistically significant. Table 1 summarizes the general characteristics among followed and those not included in the final analysis due to missing data. There was not significant difference between groups.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 14-year-old adolescents and their parents in included and excluded participants.

| Characteristic | Values as mean ± SD or n (%) | p-value§ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Included adolescents (n = 46) |

Excluded adolescents (n = 87) |

||

| Adolescents | |||

| Age (year) | 14.21 (0.24) | 14.16 (0.39) | 0.856 |

| Gestational length (weeks)* | 38.82 (1.25) | 38.63 (1.57) | 0.666 |

| Missing | 1 (2.2) | 2 (2.3) | |

| Birth weight (g)* | 3217.61 (329.83) | 3060.12 (476.43) | 0.046 |

| Missing | 0 | 3 (3.4) | |

| Sex | |||

| Boys | 25 (54.4) | 41 (47.1) | 0.428 |

| Girls | 21 (45.6) | 46 (52.9) | |

| Method of delivery | |||

| Vaginal birth | 24 (52.2) | 39 (44.8) | 0.580 |

| Caesarean section | 10 (21.7) | 21 (24.1) | |

| Missing | 12 (26.1) | 27 (31.0) | |

| Birth order | |||

| 1st | 22 (47.8) | 51 (58.6) | 0.435 |

| 2nd | 16 (15.2) | 28 (32.2) | |

| >=3rd | 7 (15.2) | 8 (9.2) | |

| Missing | 1 (2.2) | 0 | |

| IQ score* | 111.83 (16.52) | 111.80 (15.87) | 0.971 |

| Missing | 0 | 11 (12.6) | |

| Mothers | |||

| Maternal BMI before pregnancy (kg/m2)* | 20.62 (3.05) | 20.70 (3.04) | 0.971 |

| Missing | 2 (4.3) | 6 (6.9) | |

| Maternal weight gain during pregnancy (kg)* | 11.92 (5.42) | 11.24 (5.26) | 0.398 |

| Missing | 1 (2.2) | 7 (8.0) | |

| Maternal age at childbirth (year)* | 29.74 (3.75) | 29.57 (4.16) | 0.876 |

| Maternal education | |||

| ≤ 12 years | 20 (43.5) | 31 (35.6) | 0.376 |

| > 12 years | 26 (56.5) | 56 (64.4) | |

| ETS exposure before pregnancy | |||

| Yes | 25 (54.3) | 33 (37.9) | 0.085 |

| No | 19 (41.3) | 48 (55.2) | |

| Missing | 2 (4.3) | 6 (6.9) | |

| *mean (SD) | |||

| ¶P valSD was calculated by χ2 test for categorical data and Kruskal-Wallis test for continues data. | |||

2.7.2. Statistical analysis of structural and diffusion MRI data

Partial correlation was performed to examine the association between EDCs concentration and the cortical measures of adolescent brain. Bonferroni correction (0.05/68) was applied to 68 cortical regions as the correction for multiple comparisons regarding the association between EDCs and brain structural measures. A Bonferroni-corrected p-value of less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Partial correlation was used to determine the relationship between EDCs levels and diffusion MRI metrics of white matter tracts in adolescent. A Bonferroni correction (0.05/72) was applied to 72 white matter tracts as the correction for multiple comparison when evaluating the association between EDCs and neural fibers metrics. A p-value less than 0.05 after Bonferroni correction was considered statistically significant.

We utilized the natural log-transformed values of EDC metabolites as independent variables. Creatinine served as a covariate for its correction. Furthermore, for the phthalate metabolites under investigation, maternal urine concentrations adjusted for creatinine were employed as a further correction method. To reduce the impact from other confounders, family income and gender were applied in the model as covariates. Additionally, we divided boys and girls into distinct groups for partial correlation. To investigate the potential indirect effects of prenatal EDC exposure on adolescent intelligence, as measured by Full-Scale IQ scores from the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Fourth Edition (WISC-IV).

2.7.3. Mediation analysis of MRI, Intelligence, and EDCs

If our data show significant correlations between MRI indices, EDCs, and IQ performance, we would perform the mediation analysis using a widely used open-source Matlab-based toolbox developed by Dr. Wager and colleagues (https://github.com/canlab/CanlabCore) (Wager et al., 2008, Wager et al., 2009). The mediation analysis method was described in detail in our previously published neuroimaging work (Fan et al., 2019). Based on the conceptual framework of mediation effect (MacKinnon et al., 2007), the mediation analysis models in this multimodal MRI study included three main components: the independent variable (i.e., EDCs in this study), the mediator (i.e., MRI parameters), and the dependent variable (i.e., IQ scores).

The independent variable was the concentration of various compounds in the mother's body during pregnancy, including PFHxS, PFOA, PFNA, PFOS, PFDeA, PFUA, PFDoA, MMP, MEP, MBP, MBzP, MEOHP, MEHHP, MEHP, DEHP. The mediator variable was the average measurements of each brain region's cortical thickness or surface area, or the diffusion parameters of white matter, as derived from structural MRI images. The dependent variable was the IQ scores of the adolescents, as measured by the WISC-IV test.

In the mediation model, the relationship between the independent variable (X) and the mediator (M) is characterized by path a. This path seeks to elucidate how the concentration of specific compounds during pregnancy affects brain structures. Path b, meanwhile, captures the relationship between the mediator and the dependent variable, with controls in place for X. This means the effect of brain structures on IQ scores after adjusting for compound concentrations. The direct relationship between X and Y without the influence of the mediator is called the total effect or path c. However, when the mediator is included, the remaining relationship between X and Y is called as path c'.

To establish mediation, it is essential that the product of the path coefficients a and b (a*b) is significant. This would indicate a significant indirect effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable via the mediator. In our subsequent analysis, we will use multiple linear regressions to assess the relationship between MRI measures, EDCs, and intelligence, focusing on the significance of the association between specific MRI measures and IQ score. Lastly, the statistical threshold for significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic results

A total of 133 children aged 14–15 years old participated in the present study. Participating children without MRI scans (n = 74), with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (n = 1), and/or without maternal data at pregnancy (n = 6) were excluded, resulting in a total of 52 adolescentsfor analysis. Fig. S1 presents the flow chart of participants' recruitmentand Table 1 shows the characteristics of the children and their mothers included (n = 52) and excluded (n = 81) in the present study. The mean age of the included children was 14.22 years. The mean of their gestational age, birth weight, and IQ score were 38.75 weeks, 3196.35 g, and 111.58 points, respectively. The mean of pre-pregnancy BMI, weight gain during pregnancy, and age at delivery in pregnant women were 20.69 kg/m2, 11.80 kg, and 30.09 years, respectively. No significant differences in these characteristics were observed between included adolescents and excluded adolescents (Table 1). Tables 2 shows the concentrations of EDCs in the mothers of all adolescents.

Table 2.

Concentrations of Endocrine disruptor chemicals (EDCs) in the mothers of all adolescents.

| EDCs/hormones |

All participants |

With male adolescents |

With female adolescents |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean ± std | Median | IQR | n | Mean ± std | Median | IQR | n | Mean ± std | Median | IQR | |

| Cord Blood | ||||||||||||

| PFHxS (ng/mL) | 46 | 26.05 ± 14.85 | 25.65 | 16.2–31.35 | 24 | 26.01 ± 17.19 | 23.95 | 13.38–29.48 | 22 | 26.09 ± 12.2 | 26.35 | 17.65–33.55 |

| PFOA (ng/mL) | 46 | 1.36 ± 1.4 | 0.81 | 0.23–2.36 | 24 | 1.28 ± 1.38 | 0.77 | 0.23–2.41 | 22 | 1.45 ± 1.44 | 0.84 | 0.23–2.21 |

| PFNA (ng/mL) | 46 | 1.4 ± 1.69 | 0.8 | 0.25–1.77 | 24 | 1.36 ± 1.89 | 0.73 | 0.08–1.4 | 22 | 1.45 ± 1.5 | 0.94 | 0.39–1.96 |

| PFOS (ng/mL) | 46 | 5.46 ± 4.74 | 4.22 | 2.55–6.45 | 24 | 5.04 ± 4.44 | 3.52 | 2.13–6.85 | 22 | 5.93 ± 5.12 | 4.5 | 3.3–6.2 |

| PFDeA (ng/mL) | 46 | 0.28 ± 0.32 | 0.1 | 0.1–0.42 | 24 | 0.26 ± 0.31 | 0.1 | 0.1–0.32 | 22 | 0.3 ± 0.34 | 0.1 | 0.1–0.51 |

| PFUA (ng/mL) | 46 | 4.01 ± 6.84 | 1.36 | 0.07–3.01 | 24 | 4.12 ± 7.92 | 1.45 | 0.07–2.72 | 22 | 3.89 ± 5.6 | 1.07 | 0.07–4.75 |

| PFDoA (ng/mL) | 46 | 0.29 ± 0.28 | 0.21 | 0.04–0.39 | 24 | 0.25 ± 0.31 | 0.16 | 0.04–0.34 | 22 | 0.34 ± 0.25 | 0.28 | 0.18–0.5 |

| Mother Urine | ||||||||||||

| Urinary creatinine (mg/dL) | 45 | 82.57 ± 56.23 | 61.69 | 38.52–121.48 | 24 | 94.02 ± 66.04 | 80.03 | 42.54–128.91 | 21 | 69.48 ± 40.05 | 58.66 | 36.33–95.26 |

| MMP (µg/L) | 45 | 52.89 ± 35.89 | 47.57 | 22.21–75.3 | 24 | 53.87 ± 36.68 | 45.58 | 29.76–77.37 | 21 | 51.76 ± 35.83 | 49.34 | 19.75–73.61 |

| MEP (µg/L) | 45 | 53.16 ± 57.01 | 36.96 | 24.46–53.73 | 24 | 62.62 ± 69.51 | 41.4 | 27.32–55.56 | 21 | 42.34 ± 36.93 | 32.35 | 20.52–50.27 |

| MBP (µg/L) | 45 | 58.43 ± 45.94 | 45.02 | 21.26–78.41 | 24 | 65.77 ± 47.22 | 52.56 | 30.72–105.97 | 21 | 50.04 ± 44.05 | 39.44 | 20.84–58.78 |

| MBzP (µg/L) | 45 | 12.5 ± 10.26 | 8.87 | 5.8–15.43 | 24 | 11.3 ± 7.71 | 9.2 | 5.46–14.42 | 21 | 13.87 ± 12.63 | 8.86 | 6.32–15.74 |

| MEOHP (µg/L) | 45 | 33.94 ± 64.36 | 8.64 | 5.69–25.58 | 24 | 48.56 ± 83.76 | 9.29 | 5.36–36.5 | 21 | 17.23 ± 22.21 | 8.64 | 5.82–17.09 |

| MEHHP (µg/L) | 45 | 19.07 ± 39.12 | 7.07 | 4.02–14.76 | 24 | 28.46 ± 51.77 | 6.92 | 4.47–20.31 | 21 | 8.33 ± 7.57 | 7.69 | 2.43–9.67 |

| MEHP (µg/L) | 45 | 15.86 ± 24.79 | 9.81 | 7.49–14.53 | 24 | 20.19 ± 33.11 | 10.89 | 8.49–18.62 | 21 | 10.9 ± 6.55 | 8.78 | 7.08–11.93 |

| DEHP (µg/L) | 45 | 68.87 ± 119.49 | 27.12 | 17.53–55.14 | 24 | 97.22 ± 157.39 | 32.96 | 18.19–57.4 | 21 | 36.46 ± 29.31 | 22.28 | 15.93–51.26 |

| Mother Serum | ||||||||||||

| PFHxS (ng/mL) | 45 | 1.03 ± 2.37 | 0.79 | 0.04–1.08 | 23 | 1.39 ± 3.24 | 0.82 | 0.16–1.12 | 22 | 0.64 ± 0.69 | 0.64 | 0.04–1 |

| PFOA (ng/mL) | 45 | 2.85 ± 4.39 | 2.5 | 1.06–2.97 | 23 | 3.61 ± 5.85 | 2.64 | 1.96–3.1 | 22 | 2.06 ± 1.81 | 1.92 | 0.23–2.68 |

| PFNA (ng/mL) | 45 | 1.55 ± 1.58 | 1.18 | 0.59–1.8 | 23 | 2.03 ± 2.03 | 1.41 | 0.8–2.47 | 22 | 1.04 ± 0.61 | 0.88 | 0.59–1.63 |

| PFOS (ng/mL) | 45 | 14.1 ± 9.95 | 11.3 | 9.79–17.42 | 23 | 15.55 ± 12.78 | 10.95 | 9.89–17.84 | 22 | 12.58 ± 5.63 | 12.13 | 8.8–17.15 |

| PFDeA (ng/mL) | 45 | 0.45 ± 0.29 | 0.43 | 0.27–0.6 | 23 | 0.5 ± 0.34 | 0.38 | 0.26–0.75 | 22 | 0.4 ± 0.21 | 0.43 | 0.28–0.48 |

| PFUA (ng/mL) | 45 | 4.25 ± 5.41 | 2.45 | 1.27–4.34 | 23 | 5.39 ± 7.01 | 2.72 | 1.22–8.03 | 22 | 3.05 ± 2.65 | 2.43 | 1.32–3.32 |

| PFDoA (ng/mL) | 45 | 0.31 ± 0.23 | 0.3 | 0.12–0.39 | 23 | 0.35 ± 0.3 | 0.31 | 0.04–0.58 | 22 | 0.26 ± 0.13 | 0.29 | 0.23–0.34 |

PFHxS: perfluorohexanesulfonic acid. PFOA: perfluorooctanoic acid. PFNA: perfluorononanoic acid. PFOS: perfluorooctane sulfonate. PFDeA perfluorodecanoic acid. PFUA: perfluoroundecanoic acid. PFDoA: perfluorododecanoic acid. MEP: mono-ethyl phthalate. MMP: mono-methyl phthalate. MBP: mono-butyl phthalate. MBzP: mono-benzyl phthalate. MEHP: mono-2-ethylhexyl phthalate. MEHHP: mono-2-ethyl-5-hydroxyhexyl phthalate. MEOHP: mono- 2-ethyl-5-oxohexyl phthalate. DEHP: di-2-ethyl-hexyl phthalate.

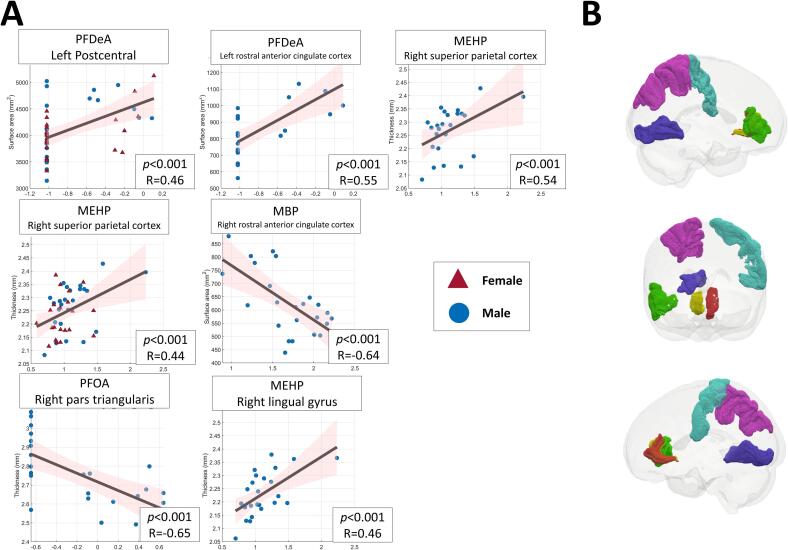

3.2. Associations between EDCs and neuroanatomical development

Table 3 presents the significant associations observed between different measures of maternal EDCs in adolescent mothers and structural MRI measures of the adolescent brains, including cortical thickness and surface areas after correction for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni correction (Fig. 1). For all mothers of adolescents in the cohort, there was a significant positive correlation between the concentration of PFDeA in cord blood and the surface area of the left postcentral gyrus (corrected p < 0.001, r = 0.458). In addition, after controlling for sex, family income and urinary creatinine, the concentration of urinary MEHP showed a significant positive association with cortical thickness in the right superior parietal cortex (corrected p < 0.001, r = 0.442).

Table 3.

Partial correlation between cortical thickness measures in different regions of the adolescent brains and maternal EDCs measures in adolescent mothers, controlling for sex, family income, and urinary creatinine.

| EDCs | Cortical Indices | Region | r | P-value | Covariates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All adolescent mothers | |||||

| Cord Blood | |||||

| PFDeA | Surface Area | Left postcentral gyrus | 0.458 | <0.001 | Sex + Family income |

| Urine | |||||

| MEHP | Cortical thickness | Right superior parietal cortex | 0.442 | <0.001 | Sex + Family income + Urinary creatinine |

| Mothers with male adolescents | |||||

| Cord Blood | |||||

| PFOA | Cortical thickness | Right inferior frontal gyrus (pars triangularis) | −0.655 | <0.001 | Family income |

| PFDeA | Surface Area | Left rostral anterior cingulate cortex | 0.549 | <0.001 | |

| Urine | |||||

| MBP | Surface Area | Right rostral anterior cingulate cortex | −0.640 | <0.001 | Family income + Urinary creatinine |

| MEHP | Cortical thickness | Right lingual gyrus | 0.467 | <0.001 | |

| Cortical thickness | Right superior parietal cortex | 0.536 | <0.001 | ||

| Mothers with female adolescents | |||||

| No significant results | |||||

| EDC: endocrine-disrupting chemicals. PFOA: perfluorooctanoic acid. PFDeA: perfluorodecanoic acid. MEHP: mono-2-ethylhexyl phthalate. MBP: mono-butyl phthalate. | |||||

Fig. 1.

(A) Scatterplots showing the significant correlations between cortical indices of specific regions in adolescent brains and maternal EDCs measures in adolescent mothers. (B) 3D glass brain renderings displaying various cortical regions associated with significant correlations from panel A. Each region is color-coded as follows: left postcentral gyrus in blue, right pars triangularis in green, left rostral anterior cingulate cortex in red, right rostral anterior cingulate cortex in yellow, right lingual gyrus in dark blue, and right superior parietal cortex in purple. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

As we hypothesized a sex-specific effect of prenatal EDC exposure on neurodevelopment, the follow-up analyses were performed separately for male and female adolescents. In the subset of mothers with male adolescents, PFOA concentration in cord blood was significantly negatively correlated with cortical thickness in the right inferior frontal gyrus (pars triangularis) (corrected p < 0.001, r = -0.655), after controlling for family income. There was also a significant positive correlation between PFDeA in cord blood and surface area in the left rostral anterior cingulate cortex (corrected p < 0.001, r = 0.549). After controlling for family income and urinary creatinine, urinary MBP levels were significantly negatively associated with surface area in the right rostral anterior cingulate cortex (corrected p < 0.001, r = -0.640). In addition, urinary MEHP showed a significant positive correlation with cortical thickness in the right lingual gyrus (corrected p < 0.001, r = 0.467), and also with cortical thickness in the right superior parietal cortex (corrected p < 0.001, r = 0.536). No significant associations were found for female adolescents.

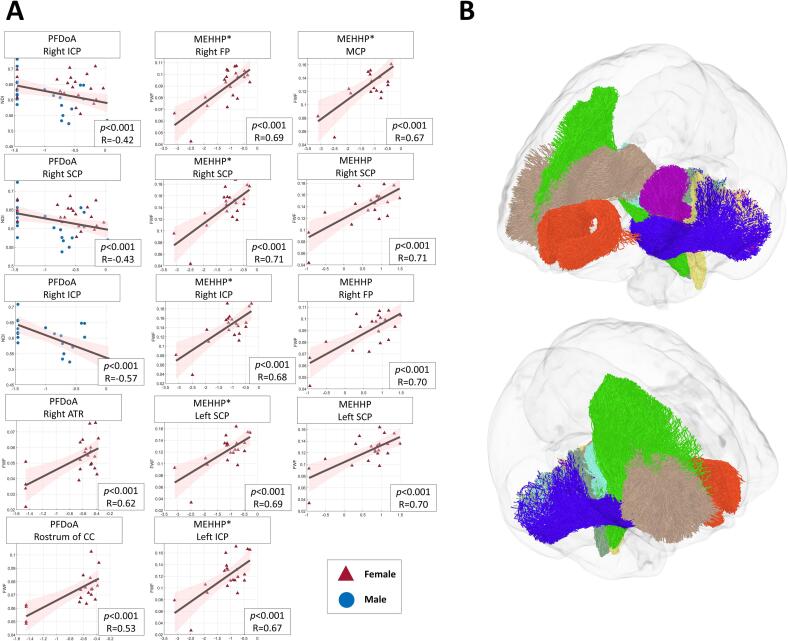

3.3. Associations between EDCs and neural fiber integrity

The associations between different measures of maternal EDCs in adolescent mothers and white matter fiber tracts of the adolescent brains were examined by using a variety of diffusion MRI techniques, including DTI, DKI, and NODDI. Table 4 presents the significant results of the associations between various EDCs and indices of white matter tracts, including FA, MD, RD, and AD, measured by the DTI technique after correction for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni correction (Fig. 2). After controlling for sex and family income, the results showed a significant association between PFDoA exposure and FA in the right inferior cerebellar peduncle (ICP) (corrected p < 0.001, r = -0.458) and in the the right superior cerebellar peduncle (SCP) (corrected p < 0.001, r = -0.46143) in all adolescents. As we hypothesized a sex-specific effect of prenatal EDC exposure on neural fiber integrity, the follow-up analyses were performed separately for male and female adolescents. After controlling for family income, the association between PFDoA and FA was significant only in the right ICP fiber tract for male adolescents (corrected p < 0.001, r = -0.587). No significant associations were found for female adolescents.

Table 4.

Partial correlation between white matter fiber tract integrity of the adolescent brains and maternal EDCs measures in adolescent mothers, controlling for sex, family income, and urinary creatinine.

| EDCs | Diffusion Indices | Region | r | p-value | Covariates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All adolescent mothers | |||||

| Cord Blood | |||||

| PFDoA | DTI_FA | Right ICP | −0.458 | <0.001 | Sex + Family income |

| DTI_FA | Right SCP | −0.461 | <0.001 | ||

| Mothers with male adolescents | |||||

| Cord Blood | |||||

| PFDoA | DTI_FA | Right ICP | −0.587 | <0.001 | Family income |

| DTI_FA | Right SCP | −0.631 | <0.001 | ||

| Mothers with female adolescents | |||||

| No significant results | |||||

| EDC: endocrine-disrupting chemicals. PFDoA: perfluorododecanoic acid. DTI: diffusion tensor imaging. FA: fractional anisotropy. SCP: superior cerebellar peduncle. ICP: inferior cerebellar peduncle. | |||||

Fig. 2.

(A) Scatterplots showing the significant correlations between white matter fiber tract of the developing brain and maternal EDCs measures in adolescent mothers. (B) A 3D glass brain visualization presenting the specific white matter fiber tract with significant correlations from panel A. The colour coding for these regions is as follows: right ICP in medium aquamarine, left ICP in champagne yellow, right FP in lime, MCP in dark blue, right SCP in cyan, left SCP in purple, right ATR in camel, and rostrum of CC in orange red. ICP: inferior cerebellar peduncle, FP: fronto-pontine, MCP: middle cerebellar peduncle, SCP: superior cerebellar peduncle, ATR: anterior thalamic radiation, CC: corpus callosum. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Table 5 presents the significant results of the associations between various EDCs and indices of white matter tracts, including MK, AK, and RK, measured by the DKI technique after correction for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni correction (Table 5). After controlling for sex and family income, significant correlations were found between PFDoA exposure and mean kurtosis (MK) in the right ICP fiber tract of cord blood samples from all adolescents (corrected p < 0.001, r = -0.333) (Table 5). For male adolescents, a significant association was observed between PFDoA exposure in cord blood and MK in the right ICP fiber tract (corrected p < 0.001, r = -0.557), controlling for family income. For female adolescents, PFDoA exposure in serum was significantly associated with AK in the anterior commisssure (CA) fiber tract (corrected p < 0.001, r = 0.692), controlling for family income.

Table 5.

Partial correlation between white matter fiber tract integrity of the adolescent brains and maternal EDCs measures in adolescent mothers, controlling for sex, family income, and urinary creatinine.

| EDCs | Diffusion Indices | Region | r | p-value | Covariates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All adolescent mothers | |||||

| Cord Blood | |||||

| PFDoA | DKI_MK | Right ICP_ | −0.384 | <0.001 | Sex + Family income |

| DKI_MK | Right SCP | −0.333 | <0.001 | ||

| DKI_RK | Right ICP | −0.379 | <0.001 | ||

| Mothers with male adolescents | |||||

| Cord Blood | |||||

| PFDoA | DKI_MK | Right ICP | −0.557 | <0.001 | Family income |

| Mothers with female adolescents | |||||

| Serum | |||||

| PFDoA | DKI_AK | CA | 0.668 | <0.001 | Family income |

| DKI_MK | Right ATR | 0.646 | <0.001 | ||

| DKI_MK | CA | 0.692 | <0.001 | ||

| DKI_RK | CA | 0.646 | <0.001 | ||

| EDC: endocrine-disrupting chemicals. PFDoA: perfluorododecanoic acid. DKI: diffusional kurtosis imaging. MK: mean kurtosis. AK: axial kurtosis. RK: radial kurtosis. SCP: superior cerebellar peduncle. ICP: inferior cerebellar peduncle. ATR: anterior thalamic radiation. CA: commissure anterior | |||||

Table 6 presents the significant results of the associations between various EDCs and indices of white matter tracts, including NDI, FWF, and ODI, measured by the NODDI technique after correction for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni correction (Table 6). Our results showed that PFDoA exposure was significantly associated with NDI in the right ICP fiber tract (corrected p < 0.001, r = -0.428) and in the right SCP fiber tract (corrected p < 0.001, r = -0.432) in all adolescents (Table 6), controlling for sex and family income. For male adolescents, PFDoA exposure in cord blood was significantly associated with NDI in the right ICP fiber tract (corrected p < 0.001, r = −0.569), controlling for family income. Moreover, for female adolescents, PFDoA exposure in serum was significantly associated with FWF in the right anterior thalamic radiation (ATR) fiber tract (corrected p < 0.001, r = 0.622) and FWF in the rostrum of the CC fiber tract (corrected p < 0.001, r = 0.538), controlling for family income. In additon, after controlling for family income and urinary creatinine levels, the results showed that exposure to urine MEHHP was significantly associated with FWF in the right fronto-pontine (FP) fiber tract (corrected p < 0.001, r = 0.702), in the left SCP fiber tract (corrected p < 0.001, r = 0.700), and in the right SCP fiber tract (corrected p < 0.001, r = 0.711) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Partial correlation between white matter fiber tract integrity of the adolescent brains and maternal EDCs measures in adolescent mothers, controlling for sex, family income, and urinary creatinine.

| EDCs | Diffusion Indices | Region | r | p-value | Covariates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All adolescent mothers | |||||

| Cord Blood | |||||

| PFDoA | NODDI_NDI | Right ICP | −0.428 | <0.001 | Sex + Family income |

| NODDI_NDI | Right SCP | −0.432 | <0.001 | ||

| Mothers with male adolescents | |||||

| Cord Blood | |||||

| PFDoA | NODDI_NDI | Right ICP | −0.569 | <0.001 | Family income |

| Mothers with female adolescents | |||||

| Serum | |||||

| PFDoA | NODDI_FWF | Right ATR | 0.622 | <0.001 | Family income |

| NODDI_FWF | Rostrum of the CC | 0.538 | <0.001 | ||

| Urine | |||||

| MEHHP | NODDI_FWF | Right FP | 0.702 | <0.001 | Family income + Urinary creatinine |

| NODDI_FWF | Left SCP | 0.7000 | <0.001 | ||

| NODDI_FWF | Right SCP | 0.711 | <0.001 | ||

| MEHHP (creatinine adjusted)* | NODDI_FWF | Right FP | 0.689 | <0.001 | Family income |

| NODDI_FWF | Left ICP | 0.674 | <0.001 | ||

| NODDI_FWF | Right ICP | 0.685 | <0.001 | ||

| NODDI_FWF | MCP | 0.666 | <0.001 | ||

| NODDI_FWF | Left SCP | 0.689 | <0.001 | ||

| NODDI_FWF | Right SCP | 0.712 | <0.001 | ||

| *The concentration of EDCs in urine was divided by the concentration of urinary creatinine. EDC: endocrine-disrupting chemicals. PFDoA: perfluorododecanoic acid. MEHHP: mono-2-ethyl-5-hydroxohexyl phthalate. NODDI: Neurite Orientation Dispersion and Density Imaging. NDI: neurite density index. FWF: free water fraction. SCP: superior cerebellar peduncle. ICP: inferior cerebellar peduncle. FP: fronto-pontine. MCP: middle cerebellar peduncle. ATR: anterior thalamic radiation. CC: corpus callosum. | |||||

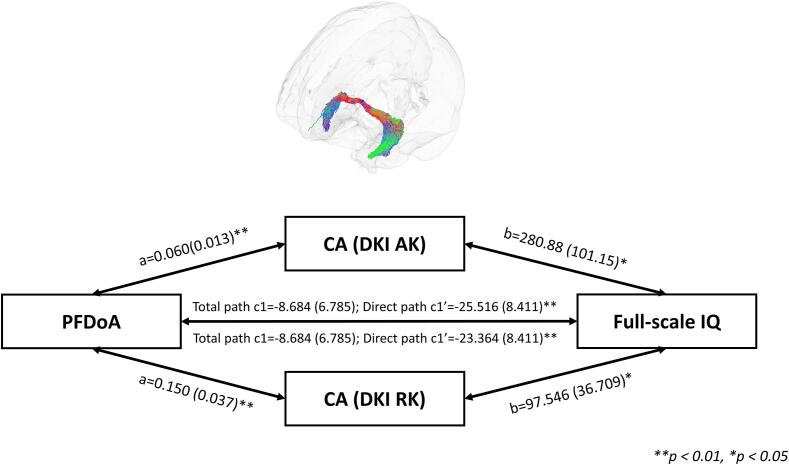

3.4. Mediation analysis among diffusion MRI indices, intelligence, and EDCs

As the diffusion MRI metrics, IQ scores, and EDCs measures were significantly correlated, we performed the mediation analyses to examine the relationship between white matter fiber tracts in the adolescent brain, intelligence, and prenatal endocrine-disrupting chemicals exposure. For serum PFDoA, since PFDoA, IQ scores and AK/RK/MK values of the CA fiber tract are significantly correlated, the mediation analyses were performed to examine whether AK/RK values of the CA fiber tract serve as a mediator to influence the relationship between the PFDoA and IQ scores. The results of mediation analysis showed that AK values of the CA fiber significantly mediated the effects of the PFDoA leveles on IQ scores (a = 0.060, corrected p < 0.05; b = 280.884, Raw p < 0.05; c' = −25.516, Raw p < 0.05; c = -8.684, Raw p = 0.21453) (Fig. 3). In addition, MK and RK values of the CA fiber tract were significant mediators between PFDoA levels and IQ scores (MK: a = 0.121, corrected p < 0.05; b = 134.961, Raw p < 0.05; c' = −24.947, Raw p < 0.05; c = -8.684, Raw p = 0.21; RK: a = 0.150, corrected p < 0.05; b = 97.546, Raw p < 0.05; c' = –23.364, Raw p < 0.05; c = -8.684, Raw p = 0.21) (Table 7).

Fig. 3.

Mediation analysis between CA fiber tract (DKI AK and DKI RK), IQ score, and PFDoA exposure. A 3D glass brain visualization presenting CA fiber tract the streamlines were coloured according to the direction, as follows: anterior-to-posterior: green; superior-to-inferior: blue; and left-to-right: red. CA: commissure anterior, PFDoA: perfluorododecanoic acid, full-scale IQ: Full-Scale Intelligence Quotient. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Table 7.

Mediation analysis results. The MRI measures mediate the effects of EDCs measures on IQ scores.

| EDCs | Diffusion Indices | Region | Path | p-value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c' | c | a | b | c' | c | ||||

| All adolescent mothers | |||||||||||

| No significant result | |||||||||||

| Mothers with male adolescents | |||||||||||

| No significant result | |||||||||||

| Mothers with female adolescents | |||||||||||

| Serum | |||||||||||

| PFDoA | DKI_AK | CA | 0.060 | 280.884 | −25.516 | −8.684 | <0.001 | 0.012 | 0.007 | 0.215 | |

| DKI_MK | CA | 0.121 | 134.961 | −24.947 | −8.684 | <0.001 | 0.017 | 0.009 | 0.215 | ||

| DKI_RK | CA | 0.150 | 97.546 | –23.364 | −8.684 | <0.001 | 0.015 | 0.009 | 0.215 | ||

| Urine | |||||||||||

| MEHHP (creatinine adjusted)* | NODDI_FWF | Right SCP | 0.035 | −306.460 | 10.896 | 0.290 | <0.001 | 0.008 | 0.037 | 0.941 | |

| *The concentration of EDCs in urine was divided by the concentration of urinary creatinine. EDC: endocrine-disrupting chemicals. PFDoA: perfluorododecanoic acid. MEHHP: mono-2-ethyl-5-hydroxohexyl phthalate. DKI: diffusional kurtosis imaging. MK: mean kurtosis. AK: axial kurtosis. RK: radial kurtosis. NODDI: Neurite Orientation Dispersion and Density Imaging. FWF: free water fraction. SCP: superior cerebellar peduncle. CA: commissure anterior. | |||||||||||

Moreover, for urine MEHHP levels, since MEHHP level, IQ scores, and FWF values of in the right SCP fiber tract are significantly correlated, the mediation analyses were performed to examine whether FWF values of in the right SCP fiber tract serves as a mediator to influence the relationship between MEHHP level and IQ scores. The results of mediation analysis showed that FWF values of the right SCP fiber tract significantly mediated the effects of MEHHP levels on IQ scores (a = 0.035, corrected p < 0.05; b = -306.461, Raw p < 0.05; c' = 10.896, Raw p < 0.05; c = 0.290, Raw p = 0.94) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Mediation analysis among right SCP fiber tract (NODDI FWF), IQ score, and MEHHP exposure. A 3D glass brain visualization presenting the right SCP fiber tract. The streamlines were coloured according to the direction, as follows: anterior-to-posterior: green; superior-to-inferior: blue; and left-to-right: red. SCP: superior cerebellar peduncle, MEHHP: mono-2-ethyl-5-hydroxohexyl phthalate, full-scale IQ: Full-Scale Intelligence Quotient. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

4. Discussion

This multimodal human neuroimaging study using structural and diffusion MRI techniques (i.e., DTI, DKI, and NODDI) showed significant associations between prenatal exposure to PFASs and phthalates, IQ score, and macro- and micro-structural changes in the adolescent brain. Moreover, our results indicated a dose–response relationship, with higher levels of EDCc exposure correlating with more pronounced changes in brain morphometry and microstructural integrity and complexity. Specifically, we observed significant associations between PFAS exposure and the surface area of the left postcentral gyrus in all adolescents and the anterior cingulate cortex in male adolescents, reduced cortical thickness in the right inferior frontal gyrus in male adolescents, and altered white-matter fiber integrity and complexity in the SCP and ICP of male and female adolescent brains. Furthermore, our study showed a strong negative correlation between prenatal exposure to these EDCs and adolescent IQ scores. Adolescents with higher levels of exposure had lower IQ scores, highlighting the potential long-term neurocognitive consequences of prenatal exposure to PFASs and phthalates. Our mediation analysis results further suggest that prenatal exposure to PFAS and phthalates in female adolescents is directly associated with white matter microstructure—particularly in the CA and SCP fiber bundles—and indirectly associated with IQ scores. Our study advances the field by providing the neuroimaging evidence to support the effects of maternal exposure to PFASs and phthalates on brain development and IQ in adolescents, using diffusion MRI indices as mediators.

Our results were consistent with previous studies showing that prenatal exposure to EDCs affects brain development (Cecil, 2022, Cediel-Ulloa et al., 2022, Chopra et al., 2014, de Water et al., 2019, Shen et al., 2021, Weng et al., 2020, Wylie and Short, 2023). For instance, maternal concentrations of EDCs have been found to correlate with adolescent brain development, with some associations being sex-specific (Weng et al., 2020). Furthermore, specific vulnerable brain areas and structures have been associated with prenatal EDCs exposure, including reduced focal brain volume, particularly in the frontal lobe, and structural changes in white matter (Shen et al., 2021).

4.1. Brain surface area, cortical thickness and white matter microstructure associated with PFAS

Our PFAS correlation analyses revealed significant associations between the concentration of PFDeA and measures of brain structure. For all adolescents, we found a significant positive correlation between the concentration of PFDeA in umbilical cord blood and the surface area of the left postcentral gyrus, which is involved in somatosensory functions, including visuomotor learning and spatial working memory. In a subset of mothers with male adolescent, the concentration of PFOA in umbilical cord blood was found to have a significantly negative correlation with the cortical thickness of the right inferior frontal gyrus (pars triangularis) after controlling for family income. The right inferior frontal gyrus (pars triangularis) is central to language understanding, speech, and other language functions. Beyond this, it also contributes to cognitive processes such as attention, working memory, and reasoning. Additionally, the concentration of PFDeA in umbilical cord blood was significantly positively correlated with the surface area of the left anterior cingulate cortex, which plays an important role in cognitive processing and emotion regulation.

Previous studies have utilized DTI technique to investigate the relationship between white matter microstructure and variations in behavior, motor skills, cognitive abilities and emotional process. In addition to conventional DTI indices, we also used advanced diffusion indices, such as NDI and FWF, which are derived from NODDI and DKI, respectively. These advanced diffusion MRI indices provide more detailed information about the microstructural complexity and are more sensitive to subtle changes than conventional DTI indices.

We found a significant association between prenatal PFDoA exposure and diffusion MRI indices, such as FA and MK, RK, NDI, FWF in neural fiber bundles of ICP, SCP, ATR, CA, CC and MCP in adolescents. The subsequent mediation models showed that AK in the CA bundle played a significant role in mediating the effects of PFDoA concentrations on IQ scores. Moreover, MK and RK of the CA bundle were also significant mediators between PFDoA levels and IQ outcomes. Studies have shown that the microstructural integrity of SCP is associated with motor impairments in individuals with autism spectrum disorders (Hanaie et al., 2013). Abnormalities in ICP and SCP have also been associated with motor adaptations and their impact on motor behaviour (Odom & Swanson, 2020). Furthermore, SCP has been associated with the development of cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome (CCAS), a disorder characterized by impairments in executive function, language processing, visuospatial abilities, and emotion regulation (Schmahmann, 2019). Therefore, the white matter changes we observed in ICP and SCP may contribute to cognitive-affective deficits in adolescents. However, further research is needed to fully understand the implications impact of these white matter microstructural changes. The ATR connects the thalamus to the frontal lobe. It plays a critical role in several cognitive functions, including attention, memory, and executive functions. Damage to the ATR has been linked to neurological and mood disorders.

CA fiber bundles that connect the left and right hemispheres of the brain, facilitating communication and information processing between different brain regions. These fiber bundles are particularly important for cognitive functions, such as attention, memory, and executive control. The CC is the largest white matter structure in the brain, connecting the left and right cerebral hemispheres. It facilitates communication between the two hemispheres and is involved in several cognitive functions, including motor coordination, visual processing, and verbal communication. Damage to the CC can lead to a range of cognitive and physical impairments, including difficulties with coordinated movements and split-brain syndrome. The MCP connects the cerebellum to the brainstem and is involved in transmitting information about voluntary movements from the cerebral cortex to the cerebellum. It plays a crucial role in motor coordination and learning new motor skills. Damage to the MCP can lead to ataxia, a condition characterized by a lack of voluntary muscle coordination.

The results of the current multimodal MRI study may suggest that increased prenatal exposure to PFASs may be associated with changes in white matter microstructure in areas related to language production and emotional function (i.e., neural fiber bundles of ATR, CC) and tracts associated with motor skills (i.e., neural fiber bundles of ICP, SCP, MCP). Increased prenatal exposure to the PFAS may also be associated with increased surface area and reduced cortical thickness in the parietal and frontal lobes. These correlations are consistent with recent findings that increased prenatal exposure to PFAS correlates with behavioural difficulties (Ghassabian and Trasande, 2018, Stein et al., 2014, Vuong et al., 2021), motor challenges (Lin et al., 2013), and cognitive impairment (Chen et al., 2013, Kawabata et al., 2017, Vuong et al., 2018). Therefore, incorporating neuroimaging data into future research on phthalates and other developmental outcomes, such as motor, cognitive, and emotional aspects, may reveal potential neurological mechanisms behind these associations.

Studies have shown that prenatal exposure to PFASs can have adverse effects on the development of adolescent brain. However, the specific mechanisms by which PFDoA affects brain development and cognitive function are not fully understood. Our results provide supportive evidence that the effects of prenatal exposure to PFDoA on intelligence are mediated, at least in part, by the microstructural changes in the CA fiber bundles. Understanding the specific mechanisms by which PFDoA affects these fiber bundles may provide valuable insights into the neurodevelopmental consequences of prenatal PFAS exposure and inform interventions aimed at mitigating the adverse effects on brain development and cognitive function in adolescents.

4.2. Brain surface area, cortical thickness and white matter microstructure associated with phthalate esters

In analyzing the association with phthalates, we found an association between higher maternal urine MBP concentrations and reduced surface area in male adolescents, particularly in the right rostral anterior cingulate cortex, which is located in the frontal part of the brain and is primarily involved in the processing emotions and is linked to the reward system, particularly responses to pain, emotion, attention, and behavior. We also found a positive association between changes in cortical thickness and MEHP level in urine, particularly in the superior parietal cortex and lingual gyrus. The superior parietal cortex is involved in spatial orientation and navigation, coordinating eye and hand movements and processing sensory information. The lingual gyrus is primary involved in visual processing, especially the recognition of objects and faces. In addition, we observed a positive association between changes in white matter microstructural integrity in adolescent females and maternal urine concentrations of MEHHP in the neural fiber bundles of right FP, MCP, bilateral ICP and SCP. The FP is responsible for transmitting neural signals from the cerebral cortex to the brainstem, specifically supporting motor control and regulation. These hypothesized relationships are consistent with recent studies showing that increased prenatal phthalate exposure is associated with motor problems (Balalian et al., 2019), cognitive slowing (Bornehag et al., 2018, Nakiwala et al., 2018), spatial processing problems (Braun et al., 2017), and emotional disturbances (England-Mason et al., 2020, Philippat et al., 2017).

The NODDI parameters measure three key neural tissue characteristics: NDI assesses axon or dendrite packing density; ODI evaluates neurite orientation coherence; and FWF estimates the extent of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) contamination. Studies have shown that certain phthalate metabolites can act as endocrine disruptors, affecting hormone levels and signaling pathways in the brain. These disruptions may have lasting effects on the adolescent brain, potentially altering neural connectivity and affecting cognitive abilities. Understanding the potential mechanisms by which phthalates affect the developing brain is crucial for implementing effective prevention strategies and mitigating the potential negative effects of exposure. Our results indicate that prenatal phthalate exposure and intelligence have an association mediated by the FWF of the right SCP, suggesting potential changes in neurite morphology with prenatal phthalate exposure (Eaton-Rosen et al., 2015). Several studies have linked DEHP exposure during pregnancy and lactation to emotional, cognitive, and social behavioral abnormalities linked to the cerebellum (Engel et al., 2018, Gascon et al., 2015, Verstraete et al., 2016). An animal study found that maternal exposure to DEHP and its metabolite MEHP caused cerebellar granule cells apoptosis, suggesting the disruption of proliferation, differentiation, or apoptosis during early postnatal cerebellar development may alter cerebellar function and structure (Fu et al., 2018). Therefore, these changes in the SCP bundles could result in the individual differences in IQ scores due to prenatal phthalate exposure. However, future studies are needed as this study lacks the power to provide detailed insights into these specific processes. Understanding the specific role of the right SCP fiber bundle in mediating the effects of prenatal exposure to MEHHP on intelligence may provide valuable information for developing targeted interventions to mitigate the negative effects of phthalates on brain development and cognitive abilities in adolescents.

In analyzing the data from our research on prenatal exposure to EDCs and their effects on brain development and IQ in adolescents, we found interesting differences between the sexes. These sex-specific differences provide valuable insights into the complex interplay between biological factors and environmental exposures during prenatal development. Our findings suggest that while both male and female adolescents are susceptible to exposure to PFASs and phthalates, the nature and extent of these effects differ between the sexes, highlighting the need for targeted interventions and further research into the underlying mechanisms. Overall, our research sheds light on the nuanced gender differences in prenatal exposure to PFASs and phthalates, and their effects on brain development. These findings have important implications for understanding and managing the potential risks associated with these environmental factors.

This landmark study provide new insights into the potential neural mediators of the association between prenatal chemical exposure and neurocognitive development in adolescents. Our findings provide compelling evidence linking these EDCs to changes in brain structure. It also suggests that changes in white-matter micro-structural integrity and complexity may serve as potential mediators for linking the effects of prenatal EDCs exposure to adolescent IQ (Deary et al., 2006, Northam et al., 2011). A potential strength of this study is the use of advanced diffusion models, which compensate for the inherent limitations of DTI and provide more comprehensive insights into brain microstructural changes. Overall, this EDC MRI work provides new insights into the effects of prenatal exposure to PFAS and phthalates on brain development and cognitive performance in adolescents. By utilizing advanced MRI techniques, we were able to identify specific brain regions affected by these EDCs and establish a link between exposure levels and cognitive impairment.

Our findings add to the growing body of evidence supporting the urgent need for stricter regulation of these chemicals to protect the neurodevelopmental health of future generations. Despite the valuable findings of this research, it is important to acknowledge its limitations. Firstly, the study sample consisted of a relatively small number of participants, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Future studies should aim to include larger and more diverse samples to increase the external validity of the findings. Moreover, the inclusion of objective measures of exposure, such as biomarkers, may provide more accurate and reliable data. Furthermore, this study primarily focused on the effects of prenatal exposure to PFASs and phthalates on brain development and IQ scores. While these are undoubtedly crucial aspects to investigate, other cognitive and behavioral outcomes, such as executive function, social skills and academic performance, should also be examined in future research. Understanding the broader impact of these EDCs exposures on various domains of child development would provide a more comprehensive understanding of their effects. Exploring the associations between brain MRI features and clinical measures has been a focus of efforts to identify clinically relevant biomarkers. However, as previous studies have suggested, reported effect sizes of brain-clinical measures associations obtained using multivariate approaches may be overly optimistic (Li et al., 2023, Li et al., 2024, Vieira et al., 2024). Future research should consider these findings and employ robust statistical methods to validate these associations in larger and more diverse populations. In addition, this study used advanced MRI techniques to look at structural and functional changes in the brain. However, it did not investigate possible mechanisms underlying the observed associations. Future research should aim to elucidate the specific pathways through which these prenatal exposures affect cognitive and brain development. Moreover, to advance the understanding of how exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals impacts the brain, future research should integrate insights from studies mapping intrinsic brain connectivity networks (Long et al., 2024, Luo et al., 2023, Wang et al., 2024, You et al., 2022). These approaches provide a mechanistic framework to elucidate the functional aspects of the human brain and shed light on potential pathways linking structural and functional changes in the adolescent brain. Finally, childhood PFAS exposure may also affect the neurodevelopment in children. For brain development, the period of rapid neuron production occurs from birth to 1.5 years of age, when approximately 4.6 million neurons are generated per hour (Silbereis et al., 2016). Recent reviews have highlighted gaps in our understanding of prenatal exposure in relation to specific brain structural changes in adolescents. It is imperative to investigate the effects of toxicant exposure during critical brain developmental stages. In addition, we want to assess prenatal exposure, which would provide unbiased results because pregnant women are unaware of their children's developmental outcomes at the time of PFAS exposure assessment. On the other hand, mothers may change their lifestyle and dietary habits after the development of their children. For these reasons, we focused only on the effects of prenatal exposure in the present study.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, our findings provide supportive evidence that prenatal exposure to EDCs may have long-lasting and sex-specific effects on neurodevelopmental changes in fronto-parietal brain regions, microstructural maturation of inter-hemispheric and cerebellar fiber tracts, and intelligence in adolescents. Furthermore, our multimodal neuroimaging results highlight the importance of using advanced diffusion imaging techniques, including DKI and NODDI, to detect neurodevelopmental changes and their brain-behavioral consequences with prenatal exposure to EDCs and the potential risks associated with these environmental factors. Future study was directed to follow up the multimodal MRI techniques to see if the alteration remained in the light of current knowledge gap (Cajachagua-Torres et al., 2024). These findings highlight the importance of understanding and mitigating the risks associated with these environmental EDCs exposures to protect the neurodevelopmental and cognitive health of our future generations.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Shi-Ming Wang: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Hui-Ju Wen: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Fan Huang: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Methodology. Chien-Wen Sun: Writing – review & editing, Methodology. Chih-Mao Huang: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Shu-Li Wang: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the children and their main caretakers who participated in the present study, the interviewers who supported the data collection, and all the study groups who participated in our longitudinal birth cohort study. This study was supported by a research grant from the National Health Research Institutes (NHRI: EM-104-PP-05, EM-113-PP-05) and National Science and Technology Council (NSTC: 111-2410-H-A49 -071-MY3; 112-2314-B-400-020-MY3), Taiwan.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2025.103758.

Contributor Information

Chih-Mao Huang, Email: cmhuang40@nycu.edu.tw.

Shu-Li Wang, Email: slwang@nhri.edu.tw.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Ames, J. L., Burjak, M., Avalos, L. A., Braun, J. M., Bulka, C. M., Croen, L. A., Dunlop, A. L., Ferrara, A., Fry, R. C., Hedderson, M. M., Karagas, M. R., Liang, D., Lin, P. D., Lyall, K., Moore, B., Morello-Frosch, R., O'Connor, T. G., Oh, J., Padula, A. M., Woodruff, T. J., Zhu, Y., Hamra, G. B., & program collaborators for Environmental influences on Child Health, O. (2023, May 1). Prenatal Exposure to Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances and Childhood Autism-related Outcomes. Epidemiology, 34(3), 450-459. Doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000001587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Andersson J.L., Sotiropoulos S.N. Nov 15). Non-parametric representation and prediction of single- and multi-shell diffusion-weighted MRI data using Gaussian processes. Neuroimage. 2015;122:166–176. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.07.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson J.L., Sotiropoulos S.N. Jan 15). An integrated approach to correction for off-resonance effects and subject movement in diffusion MR imaging. Neuroimage. 2016;125:1063–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balalian A.A., Whyatt R.M., Liu X., Insel B.J., Rauh V.A., Herbstman J., Factor-Litvak P. Apr). Prenatal and childhood exposure to phthalates and motor skills at age 11 years. Environ. Res. 2019;171:416–427. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2019.01.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basser P.J., Mattiello J., LeBihan D. MR diffusion tensor spectroscopy and imaging. Biophys. J. 1994;66(1):259–267. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80775-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bava S., Thayer R., Jacobus J., Ward M., Jernigan T.L., Tapert S.F. Apr 23). Longitudinal characterization of white matter maturation during adolescence. Brain Res. 2010;1327:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.02.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu, C. (2002, Nov-Dec). The basis of anisotropic water diffusion in the nervous system–a technical review. NMR Biomed. Int. J. Devoted Dev. Appl. Magnet. Reson. In Vivo, 15(7‐8), 435-455. Doi: 10.1002/nbm.782. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Benjamin S., Masai E., Kamimura N., Takahashi K., Anderson R.C., Faisal P.A. Oct 15). Phthalates impact human health: Epidemiological evidences and plausible mechanism of action. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017;340:360–383. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornehag C.-G., Lindh C., Reichenberg A., Wikström S., Hallerback M.U., Evans S.F., Sathyanarayana S., Barrett E.S., Nguyen R.H., Bush N.R. Dec 1). Association of prenatal phthalate exposure with language development in early childhood. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(12):1169–1176. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.3115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun J.M., Bellinger D.C., Hauser R., Wright R.O., Chen A., Calafat A.M., Yolton K., Lanphear B.P. Jan). Prenatal phthalate, triclosan, and bisphenol A exposures and child visual-spatial abilities. Neurotoxicology. 2017;58:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2016.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck, R. C., Franklin, J., Berger, U., Conder, J. M., Cousins, I. T., De Voogt, P., Jensen, A. A., Kannan, K., Mabury, S. A., & van Leeuwen, S. P. (2011, Oct). Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances in the environment: terminology, classification, and origins. Integrat. Environ. Assessm. Manage., 7(4), 513-541. Doi: 10.1002/ieam.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cajachagua-Torres K.N., Quezada-Pinedo H.G., Wu T., Trasande L., Ghassabian A. Exposure to endocrine disruptors in early life and neuroimaging findings in childhood and adolescence: a scoping review. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2024:1–27. doi: 10.1007/s40572-024-00457-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caverzasi E., Mandelli M.L., Hoeft F., Watson C., Meyer M., Allen I.E., Papinutto N., Wang C., Wheeler-Kingshott C.A.G., Marco E.J. Abnormal age-related cortical folding and neurite morphology in children with developmental dyslexia. NeuroImage: Clin. 2018;18:814–821. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2018.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecil, K. M. (2022, Mar 5). Pediatric exposures to neurotoxicants: A Review of magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy findings. Diagnostics, 12(3), 641. Doi: 10.3390/diagnostics12030641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cediel-Ulloa A., Lupu D.L., Johansson Y., Hinojosa M., Özel F., Rüegg J. Impact of endocrine disrupting chemicals on neurodevelopment: the need for better testing strategies for endocrine disruption-induced developmental neurotoxicity. Expert. Rev. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022;17(2):131–141. doi: 10.1080/17446651.2022.2044788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L.C., Jones D.K., Pierpaoli C. Restore: robust estimation of tensors by outlier rejection. Magnet. Reson. Med. Off. J. Int. Soc. Magn. Reson. Med. 2005;53(5):1088–1095. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M.-H., Ha E.-H., Liao H.-F., Jeng S.-F., Su Y.-N., Wen T.-W., Lien G.-W., Chen C.-Y., Hsieh W.-S., Chen P.-C. Nov). Perfluorinated compound levels in cord blood and neurodevelopment at 2 years of age. Epidemiology. 2013;24(6):800–808. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3182a6dd46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopra V., Harley K., Lahiff M., Eskenazi B. Association between phthalates and attention deficit disorder and learning disability in US children, 6–15 years. Environ. Res. 2014;128:64–69. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousins, I. T., DeWitt, J. C., Glüge, J., Goldenman, G., Herzke, D., Lohmann, R., Miller, M., Ng, C. A., Scheringer, M., & Vierke, L. (2020, Jul 1). Strategies for grouping per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) to protect human and environmental health. Environ. Sci. Processes Impacts, 22(7), 1444-1460. Doi: 10.1039/d0em00147c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]