Abstract

Background

The collagen β (1-O) glycosyltransferase 25 domain 1 (GLT25D1), a crucial collagen-modifying enzyme (CME), plays a pivotal role in multiple pathophysiological processes. However, its prognostic and biological roles in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) have not been reported.

Methods

CME-related genes (CMEGs) were obtained from the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB), differentially expressed CMEGs (DECMEGs) and prognostic ones were identified. GLT25D1 expression was determined at the mRNA and protein levels in multiple datasets and in our HCC cohort. Its prognostic performance was evaluated and the immune microenvironment was investigated. The effects of GLT25D1 on tumorigenesis were further explored via in vitro and in vivo experiments.

Results

Four potential prognosis-associated DECMEGs, including GLT25D1, were identified. GLT25D1 was noticeably up-regulated in HCC tissues and significantly associated with advanced tumor grade and stage. Enrichment analysis revealed that GLT25D1 could participate in regulating immune responses and various carcinogenic processes. HCC patients with high GLT25D1 expression had decreased CD8+ T cells and increased M0 macrophages, leading to an immunosuppressive microenvironment. Our in vivo and in vitro experiments confirmed the increased GLT25D1 expression, and GLT25D1 knockdown impaired the HCC malignant phenotypes.

Conclusions

Our results showed that GLT25D1 could be a carcinogenic indicator reflecting poor prognosis and might serve as a potential risk biomarker for HCC patients.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12935-025-03715-z.

Keywords: Collagen modification enzyme-related genes, GLT25D1, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Immunosuppression, Alignant phenotypes

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) represents the most prevalent form of primary liver cancer [1] and currently ranks as the fifth most commonly diagnosed malignancy and the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality globally [2, 3]. Despite advances in treatment modalities such as surgical resection, liver transplantation, and systemic therapies, including chemotherapy, radiotherapy and immunotherapy, the overall five-year survival rate for HCC patients has not been substantially improved [4]. This static prognosis is, in part, due to the typically late-stage diagnosis of HCC, which is often attributed to its asymptomatic nature and inherent biological variability. Consequently, when detected, HCC frequently presents with compromised liver function, thereby narrowing the window for effective treatment [5]. This diagnostic challenge underscores the critical need to identify molecular markers that can aid in early detection, inform the development of new therapeutic strategies, and enhance prognostic assessment of HCC, thus potentially improving patient outcomes.

Emerging evidence has consistently indicated a crucial role of collagen modifications in tumorigenesis, where increased collagen deposition and cell-collagen interactions can promote tumor development through physical support and biological signals [6, 7]. These processes are regulated by specific collagen-modifying enzymes (CMEs), notably the procollagen-lysine, 2-oxoglutarate 5-dioxygenase (PLOD) family, and prolyl 4-hydroxylase subunit alpha 1 (P4HA1) [8, 9]. Within the spectrum of CME-related genes (CMEGs), collagen β (1-O) glycosyltransferase 25 domain 1 (GLT25D1) has emerged as a protein of interest. This gene encodes a Hyl-specific galactosyltransferase enzyme [10], which catalyzes the critical step of collagen glycosylation by transferring βlinked Gal to Hyl residues [11]. GLT25D1 is widely expressed across various tissues and organs, indicating its importance in physiological processes. Notably, evidence indicates that GLT25D1 deficiency can exacerbate carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced liver fibrogenesis [12]. Although its expression has been associated with prognosis in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC) [13], the role of GLT25D1 in HCC has largely not been explored.

In this study, based on extensive public databases and through experimental validation, we identified a series of survival-associated CMEGs, among which GLT25D1 was significantly upregulated in HCC, correlating with adverse clinicopathological features and a poor survival prognosis. Our research revealed multiple GLT25D1-related oncogenic pathways and demonstrated its roles in promoting cellular proliferation, migration, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) models. In addition, we evaluated the correlation between GLT25D1 expression and immune infiltration. To improve the clinical applicability of our findings, we developed a prognostic model based on GLT25D1 expression using the LASSO-Cox regression method, providing a novel tool for predicting patient outcomes in HCC patients.

Materials and methods

Gene expression analysis

Collagen-modifying enzyme-related genes (CMEGs) were obtained from the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) [14] according to the gene sets “REACTOME_COLLAGEN_BIOSYNTHESIS_AND_MODIFYING_ENZYMES.v2023.1.Hs.gmt”. RNA-seq data, including HCC-related GEO (GSE14520, GSE25097, GSE64041, GSE121248 and GSE62232), TCGA-LIHC and ICGC (LIRI-JP) cohorts with corresponding clinical information were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/) and the International Cancer Genomics Consortium (ICGC) (https://dcc.icgc.org/projects/LIRI-JP) databases, respectively. Based on the GLT25D1 expression profile, HCC patients were divided into high- and low-GLT25D1 expression groups according to the median GLT25D1 expression. The Tumor Immune Estimation Resource (TIMER) (http://timer.cistrome.org/) and Genotype tissue expression (GTEx) (https://commonfund.nih.gov/GTEx) were also employed. The TCGA-LIHC cohort and corresponding GTEx dataset were integrated into a large cohort (TCGA + GTEx, 160 normal and 374 HCC patients). Additionally, to investigate GLT25D1 expression at the protein level, immunohistochemical (IHC) images and proteomic data from normal and HCC samples (165 pairs of HCC and adjacent tissues) were obtained from the Human Protein Atlas (HPA) database (https://www.proteinatlas.org/) and Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC) (https://cptac-data-portal.georgetown.edu) databases. The correlations between GLT25D1 expression and common clinical pathological parameters were analysed using the BioPortal (http://www.cbioportal.org), UALCAN (http://ualcan.path.uab.edu/), and TISIDB (http://cis.hku.hk/TISIDB/index.php) databases, as well as the GEO, TCGA-LIHC and ICGC (LIRI-JP) datasets.

Prognostic analysis

Cox regression analysis was used to identify significant prognosis-associated CMEGs and to systematically assess the impact of GLT25D1 on the prognosis of HCC patients. We conducted a survival analysis using the Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA) (http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/), Kaplan-Meier (K-M) plotter (http://kmplot.com/), TCGA-LIHC, and proteomics datasets with the “survminer” R package to determine the relationships between GLT25D1 expression and overall survival (OS) and relapse-free survival (RFS). The associations of GLT25D1 expression with other cancer types were also evaluated using the GEPIA database and the “survival” R package. In addition, to evaluate the accuracy of the prediction, a nomogram with a concordance index (C-index) was constructed using the “rms” R package, and univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were subsequently performed to determine the prognostic ability of GLT25D1 in HCC patients. Furthermore, we used the “limma” R package to obtain the GLT25D1-related differentially expressed genes (GDEGs) between the low and high GLT25D1 expression groups from the TCGA-LIHC cohort based on a false detection rate (FDR) < 0.05 and a|log2-fold change (FC)| > 1. Subsequently, we conducted univariate Cox analysis to screen OS-related GDEGs. Based on these selected GDEGs, a GLT25D1-related risk model was generated by least absolute contraction and selection operator (LASSO) regression with the “glmnet” R package and validated in the International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC) (LIRI-JP) cohort. The risk score of each patient was calculated using the following formula: Risk score = esum (each gene’s expression × corresponding coefficient) [15].

We further divided the HCC patients into high-risk and low-risk groups according to the median risk score and used the “stats” and “Rtsne” R packages for PCA and t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) analyses to explore the distribution of the two different risk groups. The difference in OS between the high-risk and low-risk groups was evaluated using the “survival” R package. A time-dependent ROC curve was drawn to illustrate the performance of the risk model, and the “survival ROC” R package was used to compare the predictive ability of the risk model with that of other clinical indicators. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were used to determine whether the risk score was an independent predictor of prognosis, and the relationships of the risk score with GLT25D1 expression and HCC progression were analysed.

Enrichment analysis

Based on the identified GDEGs, we applied Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) and Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analyses to determine the potential biological functions of GLT25D1 via the “clusterProfiler” R package and Metascape online tool (https://metascape.org). In addition, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) and gene set variation analysis (GSVA) were performed to investigate the carcinogenic pathways associated with GLT25D1 by using GSEA software and the “GSVA” package with reference gene sets, including KEGG, REACTOME, WIKIPATHWAYS (WP) and HALLMARKER, from the molecular signature database (MSigDB) (http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/msigdb/index.jsp). The enrichment results were further confirmed with GEO sets constructed with the “sva” R package [16]. A normalized p value < 0.05 were considered to indicate a significantly enriched pathway. In addition, the relationships between GLT25D1 and marker genes related to the enrichment pathway were also analysed.

The immune cell infiltration landscape

Based on the transcriptional matrixes obtained from the TCGA-LIHC and ICGC (LIRI-JP) cohorts, the overall infiltration score (EstimateScore), stromal content (StromalScore), immune infiltration (ImmuneScore), and tumor purity (TumorPurity) were calculated using the ESTIMATE approach with the “estimate” R package. The single sample GSEA (ssGSEA) algorithm was used to evaluate the enrichment of immune cells, immune function and immune pathways in each HCC sample by using the “GSEAbase” R package. Furthermore, the fractions of 22 infiltrating leukocyte subsets from HCC samples were quantified using the CIBERSORT package. Samples with CIBERSORT p < 0.05 were further analysed [17]. We then investigated the association of the ESTIMATE algorithm-derived score with OS by using the K‒M method in HCC samples based on GLT25D1 expression. The associations of GLT25D1 expression with T-cell exhaustion, immune suppressor cells and immunosuppressive genes were evaluated via the TIMER, GEPIA, and TCGA-LIHC datasets. The T-cell exhaustion score of each patient in the TCGA-LIHC cohort was calculated with the Tumor Immune Dysfunction and Exclusion (TIDE) database (http://tide.dfci.harvard.edu) [18], and its correlation with GLT25D1 expression was subsequently analyzed.

Human HCC specimen and tissue microarray collection

Twenty-four HCC samples and matched normal adjacent tissue samples were collected from the Chongqing University Affiliated Tumor Hospital (Chongqing, China). The HCC patients had not undergone any treatments before hepatectomy. Specimens were frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately after surgery. The studies were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethics committee of Chongqing University Tumor Hospital, and informed consent was obtained from each patient. Moreover, a human HCC tissue microarray (Cat No. IWLT-N-64LV41) was obtained from Hunan afantibody Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Hunan, China); This microarray included 80 paracancerous tissues and paired tumor samples with essential pathological characteristics.

Cell culture and stable GLT25D1 knockdown cell lines

L02, HepG2, Huh7, and Hep3B cells were obtained from the Academy of Sciences Cell Bank of China and cultured in DMEM (Gibco, California, USA) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Lentiviruses (Genechem Co., China) expressing short hairpin RNAs targeting GLT25D1 (LV-shGLT25D1) or negative controls (LV-NC) [19] were stably transfected into Huh7 and Hep3B cells with polybrene (10 µg/ml), which were subsequently selected with puromycin (Beyotime Biotechnology, China) for 2 weeks.

Quantitative real time‒PCR (RT‒qPCR) analysis

Total RNA was extract from HCC tissue or HCC cell lines using the TRIzol reagent (Takara Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd, Beijing). Reverse transcriptase was conducted to synthesize cDNA. After mixing cDNA and primers, RT-qPCR was performed using a CFX ConnectTM optical module (Bio Rad, USA). The primer sequences used were: forward 5′-AC TCACGCTACGAGCATGTC-3′; reverse 5′-GTGTCAGGGTTGAGGATCAG-3′for GLT25- D1 and forward 5′-CGCTCTCTGCTCCTCCTGTT-3′; reverse 5′-CCATGGTGTCTGAGC GATGT-3′ for GAPDH (Sangon Biotech, China), as previously reported [20].

Western blotting analysis

Protein was extracted from tissue or cell lines and separated by SDS-PAGE. Samples were transferred to PVDF membranes, and were immunoblotted with corresponding primary antibodies, including anti-GLT25D1 (#16768-1-AP; Proteintech), anti-N-cadherin (#13116; CST), anti-E-cadherin (#3195; CST), anti-vimentin (#5741; CST) and anti-GAPDH (#5174; CST), as described previously [21, 22]. Western blots band intensity analysis was performed using ImageJ software.

Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was measured by cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) and plate colony formation assays as described previously [23, 24]. Briefly, for CCK-8 assays, transfected Huh7 and Hep3B cells were seeded on 96 well culture plates (1 × 103 cells per well). CCK-8 solution (Beyotime Biotechnology, China) was added to each well at indicated time point. Cells were incubated at 37 ℃ for 1 h, and the absorbance at 450 nm wavelength was measured by using a microplate reader. For the colony formation assay, transfected Huh7 and Hep3B cells were seeded in six-well culture plates. After 14 days of cultivation, the colonies were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with Crystal Violet (Beyotime Biotechnology, China). Colony numbers were counted using Image J.

Cell invasion assays

Transwell invasion were performed as described previously [25]. Briefly, the invasive capacity of Huh7 and Hep3B cells was performed using Transwell inserts with Matrigel to form a matrix barrier (BD Biosciences, USA). After incubation for 24 h, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min and stained with crystal violet for 10 min. After washing three times, invading cells were observed and counted by using a microscope.

Wound healing assay

The Huh7 and Hep3B cells were placed in a six-well plate. When achieving 95% cell confluence, the cell monolayer were scraped with a 200 µl sterile pipette. The migrated distance and photomicrographs were captured at the indicated time points using a microscope and the remaining scratch width was determined using ImageJ software.

Cell cycle and apoptosis assays

The cell cycle and apoptosis were measured via flow cytometry analysis or TUNEL assays, as described previously [26]. In brief, transfected Huh7 and Hep3B cells were incubated for 48 h. For apoptosis assays, cells were resuspended in 500 µl ice-cold PBS, and stained with 5 µl Annexin V APC-A and DAPIPB450-A (BD Biosciences, USA) at room temperature for 20 min, and then immediately assessed by flow cytometry system (FACS Vantage SE, BD, USA). For cell cycle distribution analysis, the cells were fixed in 75% ethanol overnight, then incubated with 1 mg/ml RNase (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) for 10 min at 37℃, and subsequently were stained with propidium iodide (15 mg/ml) for 20 min at 4 ℃. The stained cells were analyzed by flow cytometry (FACS Vantage SE, BD, USA). For TUNEL assays, tumor tissue sections with paraffin embedding from mice transplanted with GLT25D1 knockdown or control Hep3B cells were stained with TUNEL (Servicebio, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The images were obtained using a fluorescence microscope (TCS SP8, Leica). The percentage of TUNEL-positive cells was counted using an ImageJ software.

Animal xenograft model

BALB/C nude mice (18–20 g) were purchased from GemPhamatech Co., Ltd. (Jiangsu, China). Xenografting tumor models were established by subcutaneous implantation of LV-shGLT25D1- or LV-shNC-transfected Hep3B cells (1 × 106/0.1 ml) into the right axilla of the mice. Tumor size was observed every week for five weeks using the formula V = 1/2 (width2× length) [24]. Finally, the mice were euthanized, and the weights of the excised tumor tissues were measured. All procedures were approved by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee, Chongqing Medical University.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining

Paraffin-embedded sections of human and mouse tumor tissue were subjected to IHC staining following a standard protocol [27] with primary antibodies, including anti-CD31 (ab28364, Abcam), anti-PCNA (#13110, CST), anti-TGF-β (ab215715, Abcam), anti-Ki67 (ab15580, Abcam), anti-CD8 (ab101500, Abcam) and anti-GLT25D1 (16768-1-AP, Proteintech). The images were captured by a light microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and analysed with Image J software. For the GLT25D1-stained HCC tissue microarray, the staining intensity and the percentage of stained cells were multiplied to obtain an IHC score for each patient as indicators for semiquantitative evaluation [28]. Finally, an IHC staining score ≤ 3.587 (the median of GLT25D1 IHC score from the 80 HCC tissue microarray) was defined as low GLT25D1 expression, while an IHC score > 3.587 was defined as high GLT25D1 expression; thus, these patients were divided into two groups (low GLT25D1 and high GLT25D1 expression) [29], as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Relationship between GLT25D1 expression and clinicopathological parameters in HCC patients

| Clinical parameters | GLT25D1 expression, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | χ2 | p-value | |

| Gender | 0.104 | 0.747 | ||

| Male | 26 (32.5%) | 28 (35.0%) | ||

| Female | 14 (17.5%) | 12 (15.0%) | ||

| Age (years) | 0.104 | 0.747 | ||

| > 55 | 15 (18.8%) | 18 (22.5%) | ||

| <=55 | 25 (31.3%) | 22 (27.5%) | ||

| Tumor sizes (cm) | 4.178 | 0.041 | ||

| > 5.5 | 13 (16.3%) | 24 (30.0%) | ||

| <=5.5 | 27 (33.8%) | 16 (20.0%) | ||

| T | 13.878 | 0.003 | ||

| T1 + T2 | 27 (33.8%) | 13 (16.3%) | ||

| T3 + T4 | 13 (16.3%) | 27 (33.8%) | ||

| Pathologic stages | 13.462 | 0.004 | ||

| I + II | 32 (40.0%) | 19 (23.8%) | ||

| III + IV | 8 (10.0%) | 21 (26.3%) | ||

| Histologic grade | 13.878 | 0.003 | ||

| G1 + G2 | 31 (38.8%) | 20 (25.0%) | ||

| G3 + G4 | 9 (11.3%) | 20 (25.0%) | ||

| Microvascular invasion | 1.246 | 0.264 | ||

| no | 33 (41.3%) | 28 (35.0%) | ||

| yes | 7 (8.75%) | 12 (15.0%) | ||

| Cirrhosis | 5.735 | 0.017 | ||

| negative | 30 (37.5%) | 18 (22.5%) | ||

| positive | 10 (12.5%) | 22 (27.5%) | ||

| Survival state | 4.593 | 0.032 | ||

| alive | 29 (36.3%) | 17 (21.3%) | ||

| dead | 11 (13.8%) | 23 (28.8%) | ||

Bold values indicated the p < 0.05 by Chi-square test. Survival state was defined as alive or dead outcomes during the time from the surgery to either death or the last follow-up

Statistical analysis

Primary bioinformatic analyses were performed, and the results were visualized using the R 3.6.3 platform and GraphPad Prism 8.0 software. The Wilcoxon test or Student’s t test was used to compare the differences between two groups and comparisons between multiple groups were conducted using chi-square test, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and Bonferroni’s post-hoc test. Survival analyses of the subgroups were performed by the Cox proportional hazards regression model and the K-M approach with the log-rank test. Spearman’s or Pearson’s analysis was applied to determine the correlation between the variables. A p value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Identification of CMEGs with prognostic potential for HCC

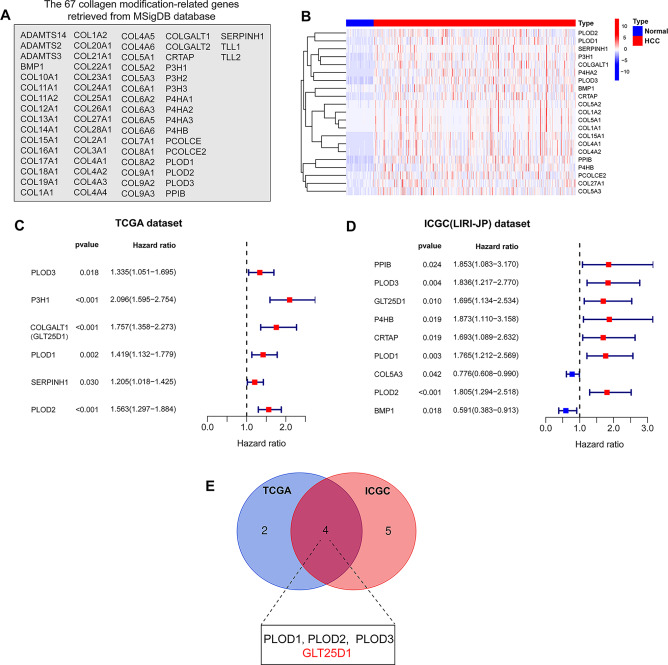

To screen CMEGs with prognostic potential for HCC, we used the Molecular Feature Database (MSigDB) to extract subsets of 67 CMEGs for this study (Fig. 1A). In the Cancer Genome Atlas-Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma (TCGA-LIHC) dataset, after screening the gene expression profiles, we found that 21 CMEGs were significantly upregulated, suggesting that the process of regulating collagen modification was interrupted in HCC (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, we performed a univariate Cox regression analysis to evaluate the impact of these CMEGs on the prognosis of HCC patients. With respect to the TCGA-LIHC and International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC) (LIRI-JP) cohorts, we identified 6 and 9 candidate CMEGs, respectively, with prognostic potential for HCC (Fig. 1C and D). Further analysis via Venn plot of the two datasets revealed the intersection of four CMEGs (PLOD1, PLOD2, PLOD3, and GLT25D1), which may be associated with the prognosis of HCC patients (Fig. 1E). Previous studies have reported the prognostic value and biological functions of PLOD family members in HCC [30, 31], but the role of GLT25D1 in the pathophysiology of HCC is still unknown. Therefore, we selected GLT25D1 as the focus of further research.

Fig. 1.

Identification of CMEGs with prognostic potential for HCC. (A) Sixty-seven CMEGs from the MSigDB database. (B) Heatmap of CMEGs’ expression. (C and D) Univariate Cox regression analysis of the 21 differentially expressed CMEGs in the TCGA (C) and ICGC (D) cohorts. (E) Venn diagram for identifying prognosis-associated CMEGs. CMEGs, collagen-modifying enzyme-related genes; MSigDB, Molecular Signatures Database

GLT25D1 expression is aberrantly upregulated in HCC

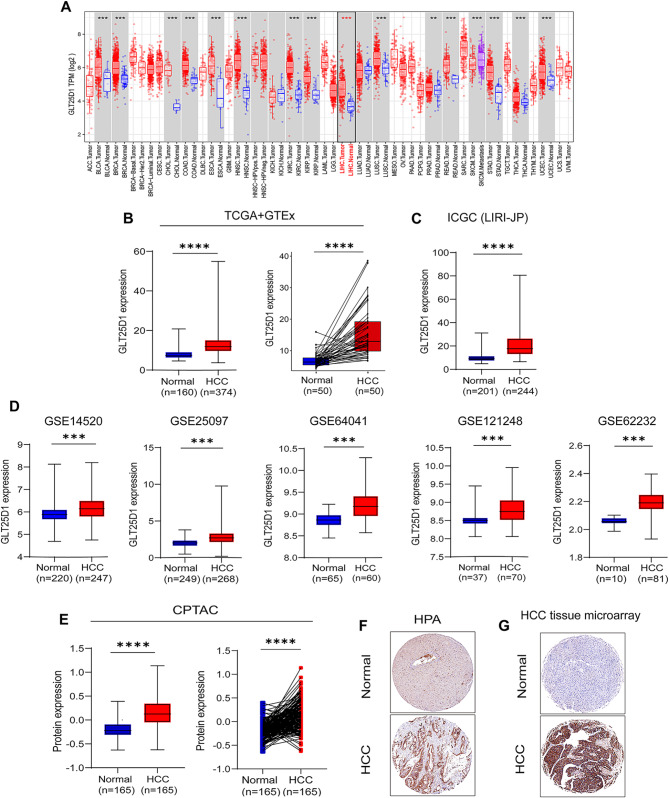

To understand the role of GLT25D1 in tumor development, the Tumor Immune Estimation Resource (TIMER) database was used to construct a gene expression profile of GLT25D1. We found that GLT25D1 expression was significantly elevated in various cancers (Fig. 2A), suggesting that GLT25D1 may be involved in the pathogenesis of various tumor, such as HCC. We further integrated multiple datasets, including TCGA + GTEx, ICGC (LIRI JP), GEO, CPTAC, and HPA datasets, and found that, compared with those in normal liver tissue, the mRNA and protein levels of GLT25D1 were significantly greater in HCC tissue samples (Fig. 2B-F).

Fig. 2.

Bioinformatics analysis of the GLT25D1 expression profile in HCC. (A) GLT25D1 mRNA expression in diverse tumor and normal tissues from the TIMER database. (B-D) GLT25D1 mRNA expression in HCC tissues from the TCGA + GTEx (B), ICGC (LIRI-JP) (C) and five independent GEO datasets (GSE14520, GSE25097, GSE64041, GSE121248 and GSE62232) (D). (E-G) GLT25D1 protein levels in HCC tissues from the CPTAC (E) and HPA (F) cohorts and our HCC microarray cohort (G). The data are presented as the means ± SDs. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 and ****p < 0.0001

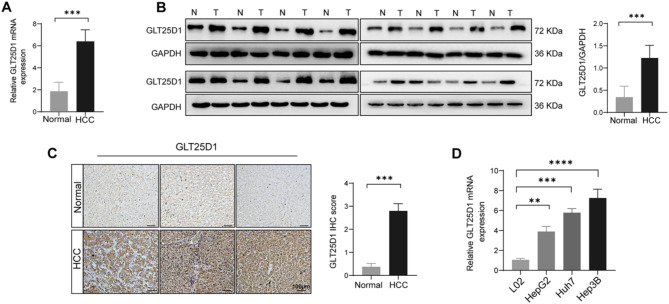

To further confirm the changes in GLT25D1 expression in HCC, we conducted RT‒qPCR, Western blotting, and IHC staining of HCC and normal liver tissue samples and found that GLT25D1 mRNA and protein expression were significantly increased in HCC tissue (Fig. 3A‒C). Furthermore, we confirmed a significant increase in GLT25D1 mRNA expression in multiple liver cancer cell lines, including HepG2, Huh7, and Hep3B (Fig. 3D). Therefore, these bioinformatics analyses, histological and cellular experiments suggest that GLT25D1 may be involved in the occurrence and development of HCC.

Fig. 3.

Identification of GLT25D1 expression in liver tissue and cell lines. (A and B) GLT25D1 mRNA (A) and protein (B) expression in HCC and normal liver tissues (n = 16). (C) IHC staining of HCC and normal liver tissues (n = 83). (D) GLT25D1 mRNA expression in cell lines (n = at least 3 repeated experiments). The data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001

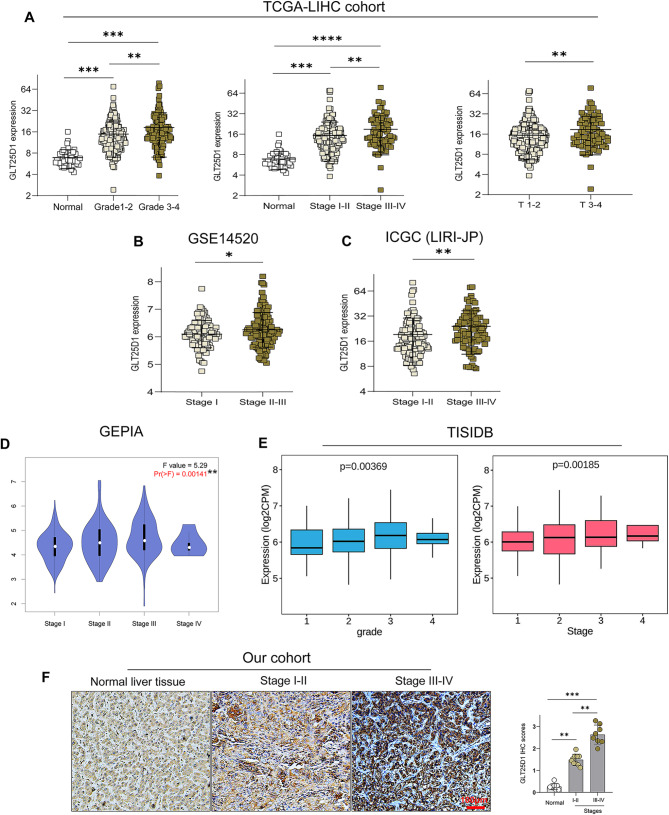

Considering that the tumor stages and pathological grades in HCC patients are important prognostic factors, we analysed the clinical characteristics of samples from the TCGA-LIHC, ICGC (LIRI-JP), GEO, GEPIA and TISIDB datasets. Our analysis revealed a significant correlation between elevated GLT25D1 expression and several adverse clinical parameters, including advanced tumor stage and grade, increased tumor size and alpha fetoprotein (AFP) levels, and increased risk of metastasis and mortality (Fig. 4A-E, Fig. S1A-C). These findings were further validated by the UALCAN database (Fig. S1D) and IHC staining in our cohort (Fig. 4F). Consistently, the results from our tissue microarray analysis confirmed that high GLT25D1 expression was significantly correlated with malignant parameters of HCC, including tumor size, T stage, pathological stage, histological grade, liver cirrhosis and survival state (Table 1, Fig. S2). These data indicated that the expression of GLT25D1, an oncogene, is significantly elevated in HCC and may enhance tumor malignancy, hence contributing to the poor prognosis in HCC patients.

Fig. 4.

GLT25D1 expression levels in patients with different pathological stages of HCC. (A-E) Association analyses of GLT25D1 expression with different pathological grades of HCC based on the TCGA-LIHC (A), GSE14520 (B), ICGC (LIRI-JP) (C), GEPIA (D) and TISIDB (E) cohorts. (F) IHC analysis of GLT25D1 expression in patients with different pathological stages (n = 43; scale bars: 100 μm). The data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Differences among multiple groups were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc tests. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001

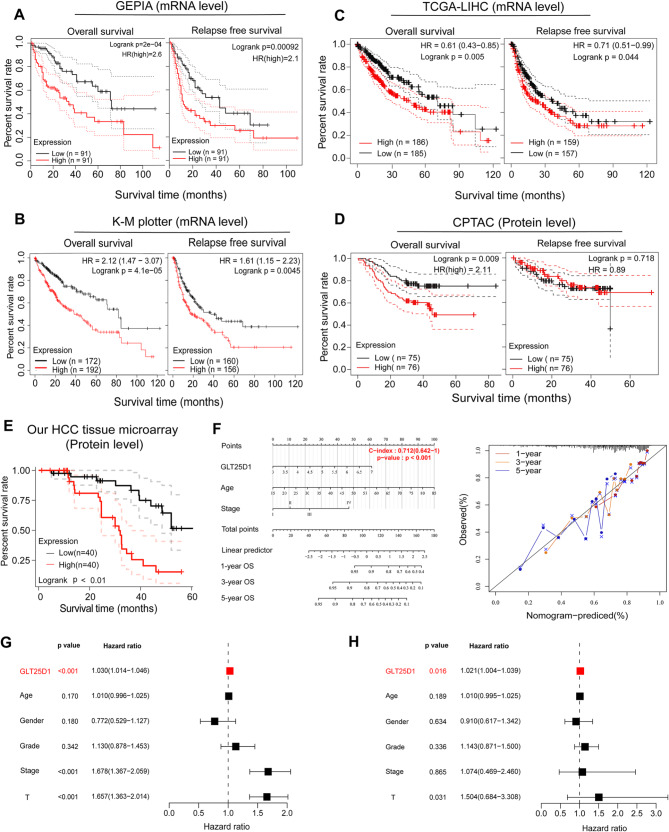

GLT25D1 serves as a prognostic indicator in HCC

We next investigated the prognostic value of GLT25D1 in HCC patients using the GEPIA, K-M plotter, CPTAC and TCGA-LIHC datasets. We observed that elevated mRNA levels of GLT25D1 were significantly associated with reduced overall survival (OS) and relapse-free survival (RFS) in patients with HCC (Fig. 5A-C). Interestingly, while higher GLT25D1 protein expression correlated with shorter OS, it did not have prognostic value for RFS, which maybe due to the limitations of sample size, detection platform and so on. (Fig. 5D and E). The robustness of these associations was further demonstrated by the construction of a nomogram, which presented excellent concordance in predicting survival at 1, 3, and 5 years, affirming the reliable prediction ability of the model (Fig. 5F). Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses revealed that GLT25D1 serves as a potential biomarker for poor OS (hazard ratio (HR) > 1, p < 0.05) (Fig. 5G), and its independent prognostic value was validated in the TCGA-LIHC cohort (HR > 1, p = 0.016) (Fig. 5H). Similar results were observed in our HCC tissue microarray cohort using univariate Cox regression (HR = 1.314, 95% CI = 1.151–1.500, p < 0.01) and multivariate Cox regression analysis (HR = 1.172, 95% CI = 0.981–1.399, p = 0.026), as presented in Table 2.

Fig. 5.

Prognostic value of GLT25D1 in HCC. (A-E) Survival curves of overall survival (OS) and relapse-free survival (RFS) according to GLT25D1 expression in HCC samples from the GEPIA (A), K-M plotter (B), TCGA-LIHC (C), CPTAC (D) and our HCC tissue microarray (E) cohorts. (F) Nomogram with calibration curve for predicting OS at 1, 3, and 5 years based on the GLT25D1 expression in HCC samples from the TCGA-LIHC cohort. (G and H) Cox regression analyses of the independent prognostic value of GLT25D1 in HCC patients from the TCGA-LIHC dataset

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis of GLT25D1 protein expression in HCC patients’ prognosis

| Univariate Cox regression | Multivariate Cox regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical variables | HR (95%CI) | p value | HR (95%CI) | p value |

| Gender (male vs. female) | 0.667(0.329–1.355) | 0.263 | ||

| Age (year, <= 55 vs. > 55) | 0.991(0.963–1.021) | 0.569 | ||

| Microvascular invasion (no vs. yes) | 0.961(0.447–2.065) | 0.919 | ||

| Cirrhosis (negative vs. positive) | 1.592(0.794–3.193) | 0.190 | ||

| Tumor size (cm, <=5.5 vs. > 5.5) | 1.062(0.958–1.177) | 0.250 | ||

| Histologic grade (G1 + G2 vs. G3 + G4) | 1.598(1.113–2.294) | 0.011 | 1.221(0.810–1.840) | 0.024 |

| T (T1 + T2 vs. T3 + T4) | 2.020(1.363–2.993) | < 0.001 | 1.387(0.853–2.254) | 0.006 |

| Pathologic stage (I + II vs. III + IV) | 1.568(1.041–2.361) | 0.031 | 1.197(0.769–1.864) | 0.015 |

| GLT25D1 level (low vs. high) | 1.314(1.151-1.500) | 0.003 | 1.172(0.981–1.399) | 0.026 |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval. Bold values indicated the p < 0.05

To evaluate the effect of GLT25D1 on the prognosis of patients with other kinds of tumor, we conducted a univariate Cox regression analysis and found that GLT25D1 expression in tumor tissues was related to OS in ACC, BLCA, GBM, KICH, KIRC, KIRP, LGG, LUAD, MESO and PAAD patients (HR > 1, p < 0.05) (Fig. S3A). K‒M analysis corroborated these findings (p < 0.01), revealing a clear inverse relationship between GLT25D1 expression and patient prognosis (Fig. S3B and C), thereby underscoring the potential universality of GLT25D1 as a prognostic marker beyond HCC.

Construction and evaluation of a prognostic risk model for HCC

To refine the prognostic stratification of HCC, we identified 1143 GDEGs from the TCGA-LIHC cohort (Fig. S4A). Among them, 68 genes were significantly associated with OS and were selected as prognostic indicators (p < 0.001) (Fig. S4B). We then established a LASSO regression model by calculating the risk score, and patients were divided into high- and low-risk groups according to the median risk scores. PCA and t-SNE analysis revealed that patients in different risk groups exhibited two directions of aggregation (Fig. S4C and D). Survival analysis highlighted a significant disparity; high-risk patients exhibited a markedly reduced survival rate and diminished survival duration in comparison to their low-risk counterparts (Fig. S4E and F). Subsequent short-term survival analysis and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis underscored the prognostic significance of the risk score (p < 0.01) and its superiority over traditional clinical pathological parameters (tumor stage, tumor grade and T classification) (Fig. S5A-C). Notably, a positive correlation between the risk score and GLT25D1 expression was observed (Spearman, r = 0.647, p < 0.001) (Fig. S5D). Analysis of patient data, considering both the risk score and GLT25D1 expression, revealed that high risk scores combined with high GLT25D1 levels were associated with the worst survival outcomes. Conversely, low risk scores and low GLT25D1 expression correlated with significantly better survival (p < 0.001) (Fig. S5E). These findings indicate that a combined assessment of risk score and GLT25D1 expression could enhance the accuracy of prognosis in HCC patients.

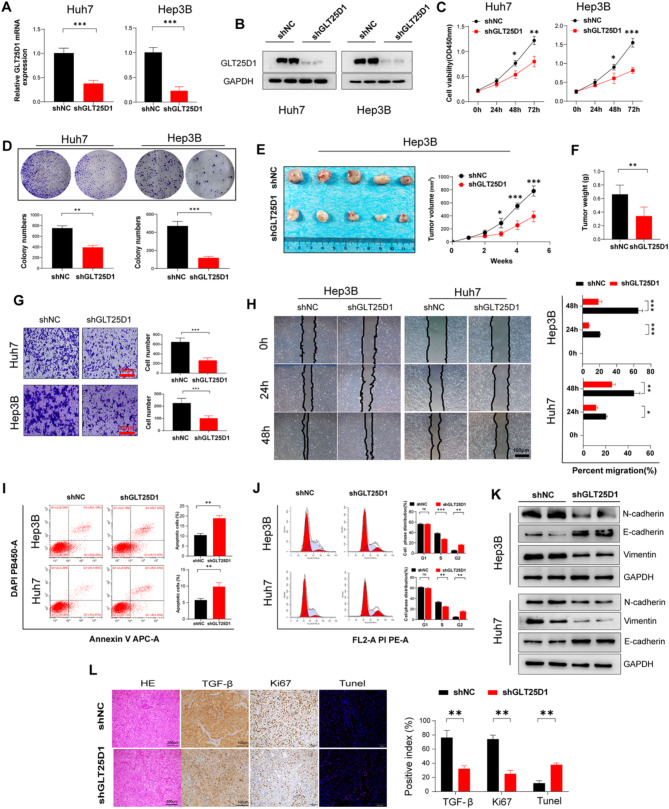

GLT25D1 contributed to cell proliferation, migration, EMT, and angiogenesis in HCC

To determine the involvement of GLT25D1 in tumor progression, we proceeded to delineate the role of this gene in tumorigenesis. Our GSEA results of the TCGA-LIHC and GEO datasets revealed that GLT25D1 expression was involved in the activation of several tumorigenic pathways, including angiogenesis, EMT, cell cycle progression and hypoxia (Fig. S6A and B). GSVA corroborated these findings, revealing significantly greater enrichment scores for cell proliferation, angiogenesis and EMT-related pathways in the cohort with high GLT25D1 expression (p < 0.001) (Fig. 6A). Similarly, we observed an increase in the expression of pivotal genes within these signaling pathways (p < 0.001) (Fig. 6B-D). Moreover, our correlation analyses indicated a positive association between GLT25D1 expression and CD31 (a marker of angiogenesis), PCNA (a marker of cell proliferation) and TGF-β (a marker of EMT) expression (all p < 0.001), a pattern that was mirrored in our IHC analyses (p < 0.001) (Fig. 6E and F).

Fig. 6.

Effect of GLT25D1 on three tumorigenic pathways. (A) Enrichment scores of cell proliferation, angiogenesis and EMT-related pathways associated with GLT25D1 expression in the TCGA-LIHC dataset. (B-D) Effects of GLT25D1 on angiogenesis (B), EMT (C) and cell proliferation-related genes (D) in the TCGA-LIHC dataset. (E and F) Correlation analysis of GLT25D1 and the three tumorigenic pathway-related genes in the TIMER, GEPIA, TCGA-LIHC (E) and IHC (F) cohorts. IHC, immunohistochemical staining. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM. **p < 0.01

To rigorously verify the effect of GLT25D1 on HCC, we used two HCC cell lines with GLT25D1 knockdown (Fig. 7A and B). We observed that GLT25D1 knockdown significantly inhibited the growth and migration of HCC cells in vitro and contributed to a reduction in tumor volume and weight in vivo (p < 0.01) (Fig. 7C-H). Further investigation via flow cytometry revealed that inhibition of GLT25D1 increased apoptosis and growth arrest in HCC cells (Fig. 7I and J). Western blot analyses revealed that GLT25D1 inhibition led to a decrease in the mesenchymal markers N-cadherin and vimentin and an increase in the epithelial marker E-cadherin (Fig. 7K). Complementary IHC confirmed the downregulation of TGF-β and Ki67 (a marker of cell proliferation) following GLT25D1 knockdown (p < 0.01) (Fig. 7L), providing further support for the role of GLT25D1 in enhancing malignant traits in HCC.

Fig. 7.

GLT25D1 knockdown inhibits HCC malignant phenotypes. Huh7 and Hep3B cells were transfected with LV-shNC/shGLT25D1 as indicated in the Methods section. (A) GLT25D1 mRNA expression. (B) GLT25D1 protein expression. (C) CCK-8 experiments for cell viability. (D) Plate colony formation assays for cell proliferation. (E and F) Morphology (E) and weight (F) of subcutaneous xenograft tumors generated from Hep3B cells. (G) Cell invasion was measured by a Transwell invasion assay. (H) Cell mobility was measured by a wound healing assay. (I and J) Cell apoptosis (I) and cell cycle progression (J) were measured via flow cytometry. (K) Protein expression of EMT-related markers. (L) H&E staining, IHC staining for Ki-67 and TGF-β and TUNEL staining of tumor tissues. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM of two or three independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01and***p < 0.001 vs. shGLT25D

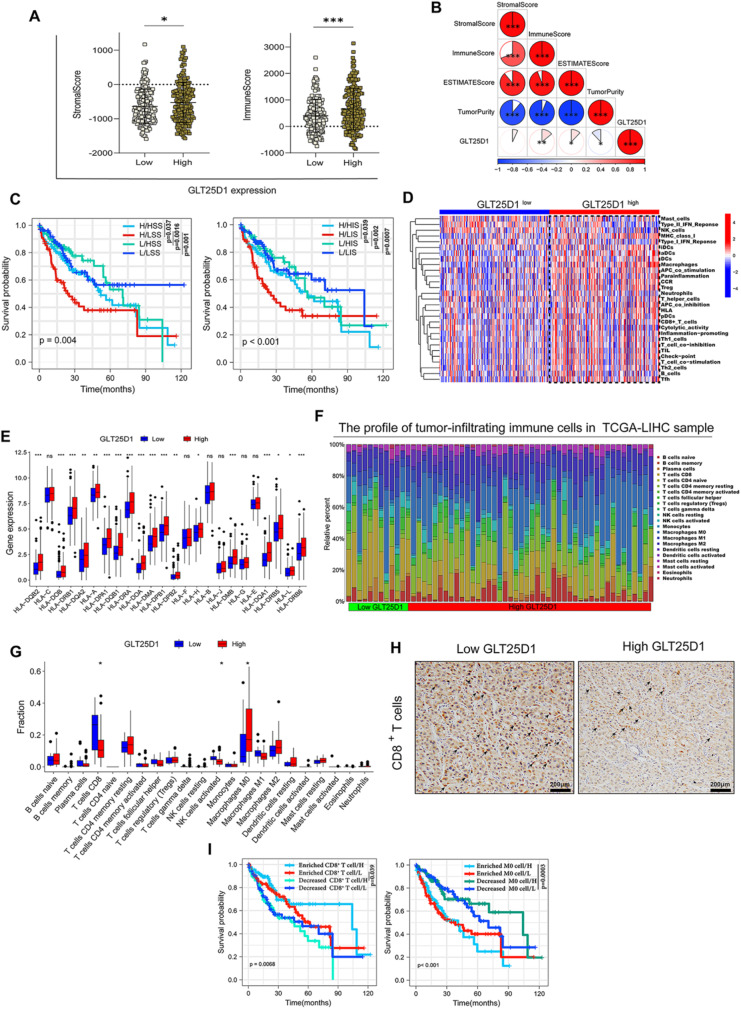

High GLT25D1 expression was associated with an immunosuppressive microenvironment in HCC

To elucidate the intricate role of GLT25D1 in HCC, we undertook a comprehensive analytical approach by integrating GO, KEGG and GSEA across several databases (Fig. S6A-G). The analysis indicated a strong correlation between GLT25D1 expression and immune-related functions. Therefore, the relationship between GLT25D1 expression and immune status was further investigated. ESTIMATE analysis revealed that patients with high GLT25D1 expression in the TCGA-LIHC cohort had a high stromal score (p < 0.05) and immune score (p < 0.001) (Fig. 8A) and ICGC (LIRI-JP) (Fig. S7A), and the immune score was positively correlated with GLT25D1 expression (p < 0.01) (Fig. 8B). In addition, patients with high GLT25D1 expression and a low immune score or low stromal score had the worst OS (p < 0.01) (Fig. 8C). ssGSEA revealed high enrichment scores for multiple immune cell functions in the high GLT25D1 expression group in the TCGA-LIHC (Fig. 8D) and LIRI-JP (Fig. S7B) cohorts, and the expression of HLA family genes was significantly greater in the high GLT25D1 expression group than in the low GLT25D1 expression group (Fig. 8E). Our CIBERSORT analysis confirmed these findings, revealing significant infiltration of M0 macrophages and a reduction in CD8+ T cells in patients with high GLT25D1 expression across the TCGA-LIHC (p < 0.05) (Fig. 8F and G) and ICGC (LIRI-JP) (p < 0.05) cohorts (Fig. S7C), as corroborated by IHC staining (Fig. 8H). These alterations in immune cell composition were significantly associated with patient prognosis (p < 0.01) (Fig. 8I). Furthermore, a significant upregulation of key checkpoint molecules was observed in patients with elevated GLT25D1 expression (Fig. S8A). Correlations drawn from the TIDE algorithm indicated that T-cell exclusion scores were positively associated with GLT25D1 levels (Fig. S8B). Similarly, markers of T-cell exhaustion, such as CD274, PDCD1, HAVCR2, TIGIT and CTLA4, exhibited a positive correlation with GLT25D1 expression across the TIMER and GEPIA databases (p < 0.0001) (Fig. S8C and D). Additionally, the expression of pivotal immunosuppressive cells, including myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and regulatory T cells (Tregs) (p < 0.0001), was positively correlated with GLT25D1 expression in the TIMER and GEPIA databases (Fig. S8 E and F). Taken together, these results suggested that increased GLT25D1 expression contributes to HCC progression and unfavorable outcomes, which was closely related to the enhancement of immunosuppressive molecules and cells within the HCC tumor microenvironment.

Fig. 8.

Association analyses between GLT25D1 expression and the immune infiltration landscape in HCC. (A) Differences in immune and stromal scores according to GLT25D1 expression. (B) Correlation analysis between immune, matrix and ESTIMATE scores and GLT25D1 expression levels. (C) K-M curves of OS based on immune and stromal scores and GLT25D1 expression levels. (D and E) Comparison of GLT25D1 expression with the ssGSEA score (D) and HLA gene expression (E) in the TCGA-LIHC cohort. (F) Profiles of the 22 tumor-infiltrating immune cells in HCC samples estimated by the CIBERSORT algorithm. (G) Fractions of 22 tumor-infiltrating immune cells in HCC samples. (H) IHC staining of CD8+ T cells in human HCC tissues. (I) K-M curves of OS in HCC samples based on GLT25D1 expression and the infiltration levels of CD8+ T cells and M0 macrophages. L, low GLT25D1 expression; H, high GLT25D1 expression; LIS, low immune score; HIS, high immune score; LSS, low stromal score; HSS, high stromal score; OS, overall survival; IHC, immunohistochemical staining. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001

Discussion

Although GLT25D1 has been shown to be a protein of interest in physiological processes, its role in HCC remains unknown. In the present study, using several public databases and bioinformatics algorithms, we identified several prognostic CMEGs and, for the first time, scientifically characterized the expression pattern, biological functions and prognostic value of GLT25D1 in HCC. We also verified its role in HCC tumorigenesis via cell-animal experiments and further explored the causal relationship between CMEGs and HCC risk.

Our results and database data (from the GEO, ICGC and CPTAC cohorts) consistently indicated that GLT25D1 expression is increased at both the mRNA and protein levels in HCC, suggesting its association with the pathogenesis of HCC. However, little is currently known about the ability of GLT25D1 to predict the prognosis of human cancers, including HCC. Our Cox regression analyses and K-M curves suggested that GLT25D1 is an independent and unfavorable prognostic indicator of both OS and RFS in patients with various cancer types, including HCC. Its high expression was associated with higher histological grades and more advanced clinical stages, which indicated greater tumor malignancy. In addition, increasing research has focused on constructing models with different genetic characteristics for predicting the prognosis of HCC patients [32]. Herein, we developed a complementary risk scoring model consisting of two key GLT25D1-related genes (SLC1A5 and G6PD) selected by Cox regression analysis and LASSO analysis.

A previous study revealed that blocking the expression of SLC1A5 can inhibit cancer proliferation, induce cell death and oxidative stress, and thus have antitumour effects [33]. Therefore, SLC1A5 may serve as a new drug target for antitumour therapy, and glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) is a rate-limiting enzyme in the pentose phosphate pathway. It has been identified as a risk biomarker related to the prognosis of HCC [34], and its increased expression accelerates the migration and invasion of HCC cells by inducing EMT [35]. In the present study, we found that HCC patients with high SLC1A5 and G6PD expression had higher risk scores than did those with normal or low SLC1A5 and G6PD expression, indicating that HCC patients with high SLC1A5 and G6PD expression had later disease stages, higher tumor grades, and poorer prognoses. In addition, the synergistic effect of high GLT25D1 expression and the risk score can be used to evaluate the prognosis of HCC patients well. Taken together, these findings suggested that GLT25D1 could be an independent prognostic indicator for patients with HCC and that its high expression may enhance HCC development.

Our GSEA and GSVA functional analyses showed that high GLT25D1 expression contributes to the activation of several carcinogenic pathways, especially the cell proliferation, EMT, and angiogenesis-related signaling pathways. These signaling pathways and processes have been reported to be involved in HCC carcinogenesis, and previous studies have revealed that proliferation, EMT and angiogenesis-related markers might serve as prognostic predictors and potential therapeutic targets in cancer [36, 37]. Herein, our in vitro and in vivo experiments further demonstrated that knockdown of GLT25D1 significantly inhibited cancer cell proliferation and migration, EMT, and tumor growth and induced HCC cell apoptosis, indicating the beneficial effect of low expression of GLT25D1. These experimental results were consistent with the bioinformatics analysis and further confirmed that GLT25D1 might be an oncogene and enhance the tumorigenicity of HCC through the aforementioned biological processes. In addition, GO and KEGG analyses of genes related to GLT25D1-related DEGs revealed that GLT25D1 is closely related to various immune-related processes and pathways, such as cytokine‒cytokine receptor interactions, chemokine signaling pathways, inflammatory responses, and cytokine production. Chemokines can affect tumor progression, treatment, and prognosis by regulating tumor immunity [38]. Therefore, we speculate that GLT25D1 may affect the biological properties of HCC through immune regulation.

As an essential defense, the immune system plays a critical role in tumorigenesis and prognosis [39]. Previous studies have demonstrated that infiltrating immune cells in the TME are strongly associated with patient survival and treatment efficacy [40]. We found that GLT25D1 expression was positively correlated with stromal score, immune score, and ESTIMATE score but negatively correlated with tumor purity. Moreover, low GLT25D1 expression and a high fraction of infiltrating immune cells had favorable effects on the prognosis of HCC patients. These findings were consistent with previous studies [41]. Furthermore, ssGSEA revealed some obvious differences in immune activity, immune cell infiltration, and immune pathway enrichment between the high- and low-GLT25D1 groups, confirming our speculation that GLT25D1 plays a key role in the TME. Subsequently, CIBERSORT analysis revealed that when GLT25D1 was highly expressed, the CD8+ T cells were weakly infiltrated, but the M0 macrophages were highly infiltrated in the TCGA-LIHC and ICGC cohorts. According to previous reports, decreased fractions of CD8+ T cells result in a poor prognosis and impaired immune response against HCC development [42], and high infiltrated fractions of M0 macrophages imply increased patient risk [43]. Consistent with these findings, we also found that these genes collectively contributed to the prognosis of HCC patients. Owing to the presence of immunosuppressive cells and cytokines as well as the exhaustion of T cells, the TME is usually in an immunosuppressive state [44]. In this study, our results revealed that GLT25D1 expression was positively associated with the phenotype of immunosuppressive cells, including MDSCs, TAMs, and Tregs, in HCC samples [45]. According to the enrichment annotation, the underlying mechanism may involve inflammatory mediators and chemokines (TNF-α, IL6 and IL-17), and the upregulation of immune inhibitors (such as PD-1, PD-L1, CTLA-4, and HAVCR2 checkpoints) associated with exhausted T cells was observed in patients with high GLT25D1 expression. Previous studies have reported that IL-6 can modulate the expression of chemokines and adhesion molecules, induce the recruitment of mononuclear leukocytes into TAMs and the accumulation of MDSCs in the tumor microenvironment, and upregulate the expression of PD-1 and HAVCR2 in tumor-infiltrated CD8+ T cells. These data indicate that GLT25D1 can cause immune suppression of the TME in HCC, which is partially mediated by inflammatory signals. Therefore, GLT25D1 may be a potential biological target for immunotherapy in HCC patients.

However, despite our comprehensive analysis of GLT25D1 across multiple databases, several unavoidable limitations still need to be noted. First, since the data originated from publicly reported cohorts, large supporting cases with clinicopathologic information from the real world are still needed to validate the credibility of our results. Second, several cellular and animal experiments were employed to preliminarily reveal the effects of GLT25D1 on proliferation, apoptosis, and EMT in HCC, but in-depth mechanistic investigations will be helpful for supporting its clinical practicality. Third, although GLT25D1 expression was shown to be associated with immune infiltration and prognosis in HCC, determining exactly whether it affects clinical outcome via immune regulation requires further study. Fourth, due to technical limitations, we did not use bioluminescence imaging to determine tumor size. Finally, whether targeted GLT25D1 therapy is beneficial for HCC treatment remains an interesting question that needs to be evaluated in further research.

In conclusion, as shown in Figure S9, this study systematically revealed that GLT25D1 enhances the tumorigenicity of HCC by interfering with cell growth and might be an independent predictor of HCC prognosis. We also found that high expression of GLT25D1 was closely related to immunosuppressive cells and factor-mediated TME immunosuppression. Our these results support GLT25D1 as a biomarker for HCC prognosis and a promising intervention target.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

S.Q. and H.H. conducted the experiments and analysed the data. H.Z. M.Y and H.W contributed to the technical assistance and discussion. G.Y., L.L., and K.L are the guarantors of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation (No.82170816, No.82300922, No.82270853), the Scientific and Technological Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission (KJZD-K202200401), theChina Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2022MD713711) and the Chongqing Natural Science Foundation Project-Postdoctoral Science Foundation Project (CSTB2022NSCQ-BHX0670).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The studies were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethics committee of Chongqing University Cancer Hospital, and informed consent was obtained from each patient. The experimental procedures performed on the mice were approved by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee, Chongqing Medical University.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Sheng Qiu and Hongdong Han contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Ke Li, Email: like@hospital.cqmu.edu.cn.

Ling Li, Email: liling@cqmu.edu.cn.

Gangyi Yang, Email: gangyiyang@hospital.cqmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cadier B, Bulsei J, Nahon P, et al. Early detection and curative treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: A cost-effectiveness analysis in France and in the united States. Hepatology. 2017;65(4):1237–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Serag HB. Rudolph. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology and molecular carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(7):2557–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Lope CR, Tremosini S, Forner A, et al. Management of HCC. J Hepatol. 2012;56(Suppl 1):S75–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zeng H, Zheng R, Guo Y, et al. Cancer survival in China, 2003–2005: a population-based study. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(8):1921–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lochter A, Bissell MJ. Involvement of extracellular matrix constituents in breast cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 1995;6(3):165–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Provenzano PP, Eliceiri KW, Campbell JM, et al. Collagen reorganization at the tumor-stromal interface facilitates local invasion. BMC Med. 2006;4(1):38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qi Y, Xu R. Roles of plods in collagen synthesis and Cancer progression. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2018;6:66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robinson AD, Chakravarthi B, Agarwal S, et al. Collagen modifying enzyme P4HA1 is overexpressed and plays a role in lung adenocarcinoma. Transl Oncol. 2021;14(8):101128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liefhebber JM, Punt S, Spaan WJ, et al. The human collagen beta(1-O)galactosyltransferase, GLT25D1, is a soluble Endoplasmic reticulum localized protein. BMC Cell Biol. 2010;11:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schegg B, Hülsmeier AJ, Rutschmann C, et al. Core glycosylation of collagen is initiated by two beta(1-O)galactosyltransferases. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29(4):943–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He L, Ye X, Gao M, et al. Down-regulation of GLT25D1 inhibited collagen secretion and involved in liver fibrogenesis. Gene. 2020;729:144233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang J, Liu D, Gu Y, et al. Potential prognostic markers and significant lncRNA-mRNA co-expression pairs in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Open Life Sci. 2021;16(1):544–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liberzon A, Subramanian A, Pinchback R, et al. Molecular signatures database (MSigDB) 3.0. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(12):1739–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liang JY, Wang DS, Lin HC, et al. A novel Ferroptosis-related gene signature for overall survival prediction in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16(13):2430–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leek JT, Johnson WE, Parker HS, et al. The Sva package for removing batch effects and other unwanted variation in high-throughput experiments. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(6):882–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ali HR, Chlon L, Pharoah PD, et al. Patterns of immune infiltration in breast Cancer and their clinical implications: A Gene-Expression-Based retrospective study. PLoS Med. 2016;13(12):e1002194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang P, Gu S, Pan D, et al. Signatures of T cell dysfunction and exclusion predict cancer immunotherapy response. Nat Med. 2018;24(10):1550–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Terajima M, Taga Y, Sricholpech M, et al. Role of glycosyltransferase 25 domain 1 in type I collagen glycosylation and molecular phenotypes. Biochemistry. 2019;58(50):5040–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baumann S, Hennet T. Collagen accumulation in osteosarcoma cells lacking GLT25D1 collagen galactosyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(35):18514–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang M, Wang J, Wu S, et al. Duodenal GLP-1 signaling regulates hepatic glucose production through a PKC-δ-dependent neurocircuitry. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8(2):e2609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wei Q, Zhou B, Yang G, et al. JAZF1 ameliorates age and diet-associated hepatic steatosis through SREBP-1c -dependent mechanism. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9(9):859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tan G, Huang C, Chen J, et al. HMGB1 released from GSDME-mediated pyroptotic epithelial cells participates in the tumorigenesis of colitis-associated colorectal cancer through the ERK1/2 pathway. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13(1):149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Y, Peng C, Chen J, et al. WTAP facilitates progression of hepatocellular carcinoma via m6A-HuR-dependent epigenetic Silencing of ETS1. Mol Cancer. 2019;18(1):127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Z, Wang J, Li J, et al. MicroRNA-150 promotes cell proliferation, migration, and invasion of cervical cancer through targeting PDCD4. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;97:511–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiao T, Zhu W, Huang W, et al. RACK1 promotes tumorigenicity of colon cancer by inducing cell autophagy. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9(12):1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang J, Zhang L, Jiang Z, et al. TCF12 promotes the tumorigenesis and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma via upregulation of CXCR4 expression. Theranostics. 2019;9(20):5810–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sinicrope FA, Ruan SB, Cleary KR, et al. bcl-2 and p53 oncoprotein expression during colorectal tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 1995;55(2):237–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhong P, Shu R, Wu H, et al. Low KRT15 expression is associated with poor prognosis in patients with breast invasive carcinoma. Exp Ther Med. 2021;21(4):305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang B, Zhao Y, Wang L, et al. Identification of PLOD family genes as novel prognostic biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Noda T, Yamamoto H, Takemasa I, et al. PLOD2 induced under hypoxia is a novel prognostic factor for hepatocellular carcinoma after curative resection. Liver Int. 2012;32(1):110–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang Y, Wu G, Li Q, et al. Angiogenesis-Related immune signatures correlate with prognosis, tumor microenvironment, and therapeutic sensitivity in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Mol Biosci. 2021;8:690206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schulte ML, Fu A, Zhao P, et al. Pharmacological Blockade of ASCT2-dependent glutamine transport leads to antitumor efficacy in preclinical models. Nat Med. 2018;24(2):194–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen Q, Li F, Gao Y, et al. Identification of energy metabolism genes for the prediction of survival in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu M, Lu L, Dong Q, et al. Elevated G6PD expression contributes to migration and invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai). 2018;50(4):370–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ouyang X, Lv L, Zhao Y, et al. ASF1B serves as a potential therapeutic target by influencing cell cycle and proliferation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2021;11:801506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu J, Lamouille S, Derynck R. TGF-beta-induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Cell Res. 2009;19(2):156–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Balkwill F. Cancer and the chemokine network. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(7):540–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marin-Acevedo JA, Kimbrough EO, Lou Y. Next generation of immune checkpoint inhibitors and beyond. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14(1):45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nishida N, Kudo M. Immunological microenvironment of hepatocellular carcinoma and its clinical implication. Oncology. 2017;92(Suppl 1):40–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pan L, Fang J, Chen MY, et al. Promising key genes associated with tumor microenvironments and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26(8):789–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Philip M, Schietinger A. CD8(+) T cell differentiation and dysfunction in cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2022;22(4):209–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang Z, Zi Q, Xu K, et al. Development of a macrophages-related 4-gene signature and nomogram for the overall survival prediction of hepatocellular carcinoma based on WGCNA and LASSO algorithm. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;90:107238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kalathil SG, Thanavala Y. Natural killer cells and T cells in hepatocellular carcinoma and viral hepatitis: current status and perspectives for future immunotherapeutic approaches. Cells. 2021;10(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Li G, Liu D, Kimchi ET, et al. Nanoliposome C6-Ceramide increases the Anti-tumor immune response and slows growth of liver tumors in mice. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(4):1024–e10369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.