Abstract

Background

Protein arginine methylations are crucial post-translational modifications (PTMs) in eukaryotes, playing a significant regulatory role in diverse biological processes. Here, we present our investigation into the detailed arginine methylation pattern of the C-terminal RG-rich region of METTL14, a key component of the m6A RNA methylation machinery, and its functional implications in biology and disease.

Methods

Using ETD-based mass spectrometry and in vitro enzyme reactions, we uncover a specific arginine methylation pattern on METTL14. RNA methyltransferase activity assays were used to assess the impact of sDMA on METTL3:METTL14 complex activity. RNA immunoprecipitation was used to evaluate mRNA-m6A reader interactions. MeRIP-seq analysis was used to study the genome-wide effect of METTL14 sDMA on m6A modification in acute myeloid leukemia cells.

Results

We demonstrate that PRMT5 catalyzes the site-specific symmetric dimethylation at R425 and R445 within the extensively methylated RGG/RG motifs of METTL14. We show a positive regulatory role of symmetric dimethylarginines (sDMA) in the catalytic efficiency of the METTL3:METTL14 complex and m6A-specific gene expression in HEK293T and acute myeloid leukemia cells, potentially through the action of m6A reader protein YTHDF1. In addition, the combined inhibition of METTL3 and PRMT5 further reduces the expression of several m6A substrate genes essential for AML proliferation, suggesting a potential therapeutic strategy for AML treatment.

Conclusions

The study confirms the coexistence of sDMA and aDMA modifications on METTL14’s RGG/RG motifs, with sDMA at R425 and R445 enhancing METTL3:METTL14’s catalytic efficacy and regulating gene expression through m6A deposition in cancer cells.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12964-025-02130-1.

Keywords: METTL14, Symmetric dimethylarginine, N6-methyladenosine, Post-translational modification, Acute myeloid leukemia

Introduction

N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is the most prevalent internal modification in eukaryotic RNAs [1]. m6A modification of RNAs plays many important roles in regulating RNA splicing, translation, stability, translocation, and the high-level structure [2–4]. Aberrant m6A levels are involved in cancer progression via regulating the expression of tumor-related genes [5]. For example, elevated m6A levels in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells facilitate the translation of oncogenes such as SP1, c-MYC, BCL2 and PTEN, promoting AML development and maintenance [6, 7].

The function of m6A is carried out by orchestrated activities from the “writers” (methyltransferases), the “erasers” (demethylases) and the “readers” (proteins that recognize and bind to m6A) in the cell. METTL3:METTL14 heterodimer forms the core complex of the major “writer” for m6A addition, in which METTL3 is the catalytic subunit binding the methyl donor, S-adenosyl methionine, while METTL14 acts as the RNA-binding scaffold responsible for substrate recognition [8, 9]. The activity of the methyltransferase complex is under various regulations, including post-translational modifications such as SUMOylation [10], phosphorylation [11], ubiquitination [12] and methylation [13–15]. The C terminal region of METTL14, which comprises multiple RGG/RG repeats, was reported to be asymmetrically dimethylated at arginine residues by PRMT1 and PRMT3 [14–16]. Asymmetric dimethylarginine (aDMA) in this region was suggested to promote its binding to RNA substrates and enhance the methyltransferase activity of the complex [14, 15].

Arginine methylation is a post-translational modification commonly found in histones and non-histone proteins, including many RNA-binding proteins, plays a significant role in epigenetic regulation as well as protein–protein and protein-RNA interactions [17]. Arginine methylation exists in three forms, including monomethylarginine (MMA), aDMA and symmetric dimethylarginine (sDMA), which are catalyzed by a family of nine arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs) in human [18]. Type I PRMTs are responsible for adding aDMA modifications, type II for sDMA modifications and type III for MMA only [19]. We have previously developed an optimized strategy for protein methylarginine profiling utilizing an ETD-based mass spectrometry method [20]. Using such a strategy, we profiled arginine methylation in cancer cell lines with high sDMA modifications. We identified and confirmed the symmetric dimethylation at R425 and R445 within the extensively methylated RGG/RG motifs of METTL14. We demonstrated the regulatory role of MELLT14 sDMA modification in the catalytic efficacy of the RNA methyltransferse complex and m6A-specific gene expression in HEK293T and acute myeloid leukemia cells, potentially through the action of m6A reader protein YTHDF1. Furthermore, we showed a potential therapeutic application in AML treatment through the combined inhibition of METTL3 and PRMT5.

Methods

Cell culture

HEK293T cells were from Cellcook Biotech Co., Ltd (Guangzhou, China). MOLM-13 cells were from Beyotime Biological Technology Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). A549, MCF7, HELA, HCC827, THP-1, and HL-60 cells were gifts from Prof. Wang Junjian at Sun Yat-Sen University (Guangzhou, China). HEK293T, A549, MCF7, and HELA cells were cultured in DMEM (GIBCO, C11995500BT) medium supplemented with 10% FBS at 37 °C and 5% CO2. THP-1, MOLM-13, HL-60, and HCC827 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (GIBCO, C11875500BT) medium supplemented with 10% FBS at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

Antibodies and chemicals

METTL14 (48699S), sDMA (13222S), anti-rabbit IgG (7074S) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. METTL3 (15073), BRD4 (28486), SP1 (21962), GAPDH (10494), m6A (68055), YTHDF1 (17479) were purchased from Proteintech. Anti-FLAG antibody was from Sigma (F1804). Anti-mouse IgG (sc-516102), and YTHDF3 (sc-377119) were from Santa Cruz (sc-516102). The anti-YTHDF2 antibody was from solarbio (K107893P). Type I PRMTs inhibitor MS023 (HY-19615), PRMT5 inhibitor EPZ015666 (HY-12727) and METTL3 inhibitor STM2457 (HY-134836) were purchased from MCE.

DNA cloning

For expression of proteins in this study, the relevant DNA sequences were cloned into pcDNA 3.1 vector between restriction sites BamHI and XbaI, and the relevant DNA sequences were cloned into pcDH vector between restriction sites NheI and EcoRI. The cDNA for PRMT1, PRMT5, MEP50, METTL3, and METTL14 were purchased from YouBio Platform (Changsha, China). Codon-optimized FLAG-METTL14 DNA sequence was synthesized by GENEWIZ INC. RK mutations of METTL14 were generated by overlapping PCR.

The shRNAs targeting YTHDF1, YTHDF2, YTHDF3, PRMT5 and METTL14 were cloned into pLKO.1 TRC-cloning vector via EcoRI and AgeI restriction sites. All the oligos and primers used in DNA cloning were synthesized by GENEWIZ INC. (Suzhou, China). The primers used in the study were included in Table S1.

Lentivirus production and transduction

For lentivirus production, HEK293T cells were co-transfected with lentiviral plasmid, pSPAX2 and pMD2.G at a 7:5:2 ratio in serum-free DMEM. 3 μL polyethylenimine was added per μg plasmid. 4 h later, changed to complete DMEM. The supernatant medium was harvested 48 h after transfection and centrifuged in 2000 xg for 10 min, aliquoted, and stored at −80 °C. Target cells were infected at 30% confluence by addition of viral supernatant and 10 μg/mL polybrene.

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from cell pellets by RNAiso Plus (Takara, 9108) and quantified by NanoDrop (Thermo). 1 μg total RNA was reverse transcribed by PrimeScript RT Enzyme Mix (Takara, RR047) at 37 °C for 15 min. Then, the cDNAs were used as templates for qPCR assays by TB Green Premix Ex Taq II (Takara, RR820) using CFX96 qPCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). The BRD4, SP1, and c-MYC mRNA levels were normalized to the housekeeping gene GAPDH and further analyzed using GraphPad Prism (version 8).

Immunoblotting

Cells were digested with Trypsin and washed twice with cold PBS. Cell pellets were lysed in RIPA buffer (MCE, HY-K1001) for 30 min at 4 °C. The lysates were sonicated on ice and then spun at 12,000 g for 30 min. The supernatants were collected as the whole cell lysates and the protein concentration were determined by BCA assay (Beyotime, P0012). Equal amounts of total proteins were mixed with equal volume of 2 × SDS loading buffer (MCE, HY-K1100) suppled with 50 mM DTT and heated at 95 °C for 10 min. The protein samples were separated on a 10% Bis–Tris gels and transferred onto 0.22 μm PVDF membranes (PALL, BSP0161). The membranes were blocked with 5% BSA in TBST at room temperature for 1 h and then incubated with primary antibody at 4 °C overnight. After washing three times with TBST, the membranes were further incubated with a secondary antibody at room temperature for 1 h. The membranes were washed three times with TBST and exposed with PHOTO METRICS (Tanon, 5200). The protein expression level was quantified by grayscale analysis.

Immunoprecipitation

HEK293T cells expressing FLAG-METTL14 or FLAG-METTL3 were washed briefly with cold PBS and lysed in immunoprecipitation buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% CA-630, and protease inhibitor) at 4 °C for 30 min. Lysed cells were centrifugated at 12,000 g for 30 min and the supernatants were collected as cell lysates. 100 μL cell lysates were saved as input controls, the remaining lysates were incubated with prepared anti-FLAG magnetic beads (Pierce, A36797) overnight at 4 °C with gentle vertical rotation. The immunocomplex was precipitated by the magnet and washed three times with the immunoprecipitation buffer. For western blot analysis, the proteins were eluted by 2 × SDS loading buffer with 50 mM DTT at 95 °C for 10 min. For MS analysis, the proteins were eluted with ulilysin buffer (100 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 10 mM CaCl2) with 0.5% Rapigest and 20 mM DTT at 95 °C for 10 min.

Protein purification

HEK293T cells were transfected with indicated plasmids for 72 h and harvested by PBS with 2 mM EDTA. Samples were then lysed in CO-IP buffer at 4 °C for 30 min and clarified by centrifugation. The supernatant was incubated with Ni–NTA Resin (GenScript, L00250) at 4 °C for 2 h and eluted by gradient elution buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 20—200 mM imidazole) at 4 °C. The eluate was then desalted and concentrated in store buffer (0.01% Triton-X 100 and 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4) by Amicon Ultra 0.5 ml 10 K (Millipore, UFC5010). The concentration of purified proteins was determined by BCA reagent and aliquoted, stored at −80 °C.

In vitro peptide methylation assays

Peptides derived from the RGG/RG motifs of METTL14 were synthesized. 5 µM peptides were incubated with 150 nM PRMT1 or PRMT5 with MEP50 in peptide reaction buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 25 μM ademetionine) at 25 °C for 12 h. Methylated peptides were then assayed by Bruker ultrafleXtreme MALDI–time-of-flight mass spectrometer. 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid was used as a MALDI matrix.

RNA methyltransferase activity assay

The sequence of RNA probes (5’-ACGAGUCCUGGACUGAAACGGACUUGU-3’) was derived from a previous study [8]. Before the reaction, the RNA probes were annealed by incubating at 95 °C for 5 min and with the 700 cycles of decreasing 0.1 °C per cycle in 4 s beginning from 95 °C. Then, in vitro methyltransferase activity assay was performed in RNA reaction buffer (0.8 μM SAM, 0.2 U/mL RNasin, 1 mM DTT, 1% glycerol, 0.01% Triton-X and 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4) with concentration gradient RNA probe and 0.012 nmol each fresh recombinant protein (METTL3 and METTL14 wildtype or mutants with a molar ratio of 1:1 for the two components). The reaction was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h and then inactivated at 85 °C for 5 min. The resultant RNA was digested by nuclease P1 and alkaline phosphatase for LC–MS/MS analysis. The nucleosides were quantified by multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) modes using the mass transitions of G (284.1 to 152.1) and m6A (282.1 to 150.1). G served as an internal control to normalize the amount of RNA probe in each reaction mixture [21].

RNA co-immunoprecipitation

The cell pellets were lysed by RIP binding buffer (150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.5% NP40, RNasin, protease inhibitor cocktail) at 4 °C for 30 min and centrifuged at 1000 xg for 5 min. The supernatant was combined with an anti-YTHDF1 antibody or IgG control at 4 °C overnight with rotation. The solution was then combined with protein A at 4 °C for 2 h with rotation. The co-immunoprecipitated RNA was eluted with DEPC water at 60 °C for 5 min after washing three times with RIP wash buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA). Total RNA was extracted from equal cell pellets by RNAiso Plus (Takara, 9108) as input.

m6A RNA immunoprecipitation and sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from cell pellets by RNAiso Plus. For mRNA enrichment, total RNA was combined with dT (25)-biotin oligos at 25 °C for 10 min in mRNA binding buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 1 M NaCl, 2 mM EDTA) with rotation. Then, the solution was incubated with streptavidin magnetic beads at 25 °C for 30 min with rotation. The mRNA was eluted with DEPC water at 80 °C for 5 min after washing 3 times with RIP wash buffer. Before use, the anti-m6A antibody was combined with protein A magnetic bead at 25 °C for 1 h with rotation in RIP buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, RNasin). The mRNA was incubated with prepared beads at 4 °C for 6 h with rotation in RIP buffer. The mRNA with m6A modification was then eluted with m6A elution buffer (5 mM m6A, 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4) at 60 °C for 10 min after washing 3 times with RIP buffer and followed by standard ethanol precipitation. For m6A sequencing, the mRNA was fragmented by fragment buffer (10 mM ZnCl2, 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.0) at 94 °C for 5 min and stopped by 20 mM EDTA at 4 °C, following by standard ethanol precipitation. Then, fragment mRNA was immunoprecipitated by the anti-m6A antibody as described above. Priming was performed using Random Primers. Then libraries with different indexes were multiplexed and loaded on an Illumina Novaseq instrument for sequencing using a 2 × 150 paired-end (PE) configuration according to manufacturer’s instructions. Read quality was assessed using the R package Rfastp (v 1.14) [22]. The read data were filtered for PCR duplicates and filtered to remove the ones with mapping quality less than 20 using SAMtools (v 1.20) [23]. Filtered reads were next mapped to the hg38 genome using the R package Rhisat2 (v 1.2) with default parameters. Peak detection and differential methylation for Methylated RNA Immunoprecipitation Sequencing was performed by R package exomePeak2 (v 1.16). Metagene plots were generated using the R package Guitar (v 2.2.0) [24]. The m6A peaks were analyzed for enrichment of known and de novo motifs using the software HOMER (v 4.10) [25]. Genomic annotation was performed using ChIPseeker (v 1.40) [26].

Cell viability assays

MOLM-13, THP-1, and HL-60 cells were plated in 96 well plates with 200 μL medium in triplicate at 10, 000 cells per well and treated with vehicle (DMSO) or the indicated concentrations of STM2457, EPZ015666, and MS023 for 6 days. Change the medium once during the treatment period. Cell viability was assayed using Cell Counting Kit-8 (MCE) on day 6 and analyzed using GraphPad Prism (version 8).

Bliss independence model analysis

The efficacy was quantified as the percentage of cancer cells that underwent apoptosis following drug administration, a metric commonly denoted as the inhibition rate (Y(A) and Y(B)). This methodology involves a comparative assessment of the observed combination response (Y(O)) against the predicted combination response(Y(P)). Synergism is typically inferred when the observed response surpasses the predicted response.

Scores greater than 10, between −10 and 10, and less than −10 are considered synergistic, additive, and antagonistic, respectively.

LC–MS/MS analysis

Before digestion, protease ulilysin [20] was activated in ulilysin buffer (100 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 10 mM CaCl2) at 25 °C for 16 h. The sample was digested by 20 ng/μL activated ulilysin at 37 °C for 16 h in ulilysin buffer. After digestion, the sample was treated with 0.5% TFA to hydrolyze Rapigest at 37 °C for 30 min and centrifuged at 10,000 xg for 5 min. The supernatant was desalted by the C18 stage tip and freeze-dried. After dissolving in 15 μL 0.1% FA solution, the samples were analyzed using an EASY-nLC 1200 system coupled to an Orbitrap Fusion Lumos Tribrid mass spectrometer equipped with a Nanospray Flex Ion Source (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA). Mobile phase A: water with 0.1% FA. Mobile phase B: 80% acetonitrile, 0.1% FA, and 19.9% water. Nano-LC was operated in a single analytical column, packed in-house with Reprosil-Pure-AQ C18 phase (Dr. Maisch, 1.9 µm particle size, 15 cm column length), at a flow rate of 200 nL/min. 4 μL samples dissolved in 0.1% FA were injected into the column and eluted in a 2 h gradient. The nanoSpray ion source was operated at 2.2 kV spray voltage and 275 °C heated capillary temperature. The mass spectrometer was set to acquire full scan MS spectra (300–1750 m/z) for a maximum injection time of 120 ms at a mass resolution of 60,000 and an automated gain control (AGC) target value of 1e6. The dynamic exclusion was set to 40 s at an exclusion window of 10 ppm. In HCD scans, collision energy was 30% in fixed collision energy mode. In all HCD/ETciD/EThcD scans, the AGC target was set to 2.0e5 and the maximum injection time was 86 ms. For ETD scans, calibrated charge-dependent ETD parameters were set as True. All MS/MS spectra were acquired in the Orbitrap with a resolution of 50,000 in profile mode.

LC–MS/MS data analysis

Proteome Discoverer (version 2.2) was used to search raw files against the UniProt human database containing 20,520 entries. Protease ulilysin was set as digestion mode. A maximum of five miscleavages were allowed for the digestion mode of ulilysin. For the database searching to identify DMA, carbamidomethyl on cysteine was set as fixed modifications, while monomethylation and dimethylation on arginine, and methionine oxidation were set as variable modifications. The site probability threshold was 75. Water loss and ammonia loss were selected in the database search.

Public dataset-based survival analysis

To assess the contribution of sDMA and m6A modifications in tumor development, we analyzed the overall survival relevance of genes involved in our study in various common cancers. We used the public database Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/) for this analysis. The log-rank test was used to compare the survival curves of the 25% samples with the lowest gene expression and the 25% samples with the highest gene expression. Finally, survival score was calculated with log10 (p-Value), and high expression level associated with poor prognosis was assigned as positive value.

Statistics and reproducibility

All experiments were independently reproduced at least three times. Data were presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined by unpaired t-test for two groups comparison and one-way Anova for multiple groups comparison. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.

Results

The C-terminal RGG/RG motifs of METTL14 are modified with both sDMA and aDMA

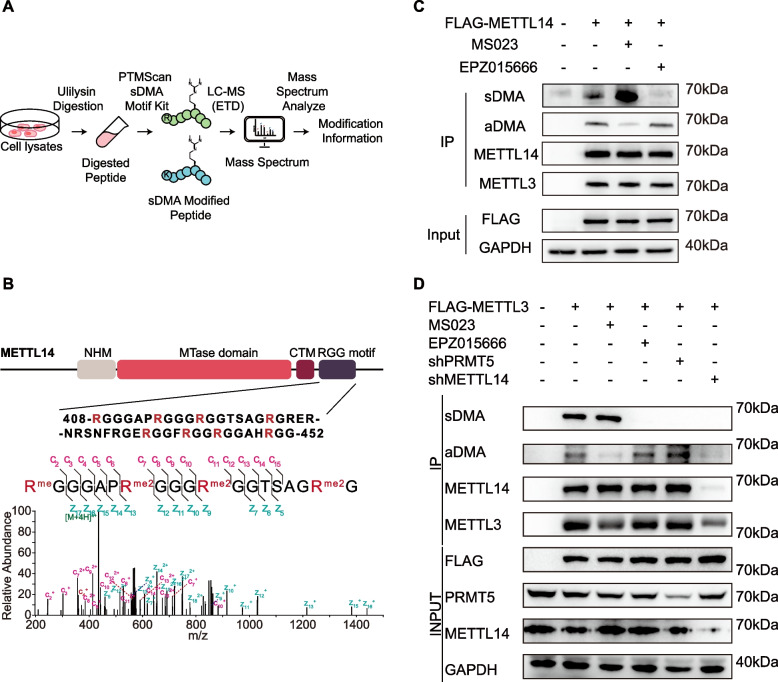

Our group has previously established an optimized ETD-based proteomic workflow for the identification of protein sDMA modifications [20]. To have a more comprehensive picture of cellular sDMA, we first examined additional cell lines for high levels of sDMA modifications as judged by western blot analysis (Figure S1). Among examined cell lines, HCC827 exhibited the highest level of overall sDMA modification. Based on this result, we performed proteomic profiling of sDMA sites in HCC827 cells to further elucidate the functional implications of this PTM (Fig. 1A). Proteomic profiling detected 137 methylarginine-containing peptides across 52 proteins (Figure S2A and S2B). Among the newly identified peptides, we noticed a peptide from the RGG/RG motif located in the C-terminal domain of METTL14 (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, the intrinsically disordered C terminus of METTL14 was reported to bear aDMA modifications, which were reported to be catalyzed by PRMT1 or PRMT3 [14–16]. Thus, our proteomic results may have presented a different perspective on the methylation events within the RGG/RG motif of METTL14 and its regulatory functions.

Fig. 1.

Identification of sDMA and aDMA Modifications at the C-terminal RGG/RG Motifs of METTL14. A Workflow for proteomic profiling of protein arginine methylation using PTM Scan sDMA motif antibody. B Schematic diagram of METTL14 domain structure. The primary sequence in the C terminal RGG/RG motif was shown with potential methylation sites in red. MS/MS spectrum shows the localization of dimethylarginines within the identified peptide from the proteome study. C Immunoprecipitation and western blot analysis of arginine dimethylation in METTL14 overexpressed in HEK293T cells. Cells were treated with 1 μM EPZ015666, 1 μM MS023, or DMSO for 72 h and METTL14 is immunoprecipitated by anti-METTL14 antibody. D Immunoprecipitation and western blot analysis of arginine dimethylation in endogenous METTL14 in HEK293T cells. Endogenous METTL14 is co-immunoprecipitated with METTL3 by anti-FLAG antibody. Cells were treated with 1 μM EPZ015666, 1 μM MS023, shPRMT5, shMETTL14 or DMSO for 72 h

The isobaric nature of sDMA and aDMA makes them difficult to distinguish by mass spectrometry, therefore we overexpressed FLAG-tagged METTL14 in HEK293T, immunoprecipitated and analyzed it by western blot using pan-specific antibodies against aDMA and sDMA, respectively. As shown in Fig. 1C, overexpressed METTL14 contains both sDMA and aDMA. In addition, when treated with EPZ015666, a specific inhibitor of PRMT5 [27, 28], the major Type II PRMT, the sDMA signal from METTL14 was significant reduced. This finding highlights the role of PRMT5 in the modification of METTL14. Similarly, treatment with MS023 [29], a potent inhibitor of human type I PRMTs, not only led to a notable reduction in aDMA levels within METTL14 but also elicited an elevation in sDMA abundance. Prior studies have suggested that inhibition of type I PRMTs may augment global sDMA levels [30]. Our findings demonstrated a similar response between these two types of dimethylation when examining a specific protein substrate.

We also confirmed the co-occurrence of aDMA and sDMA in endogenous METTL14, by co-immunoprecipitation with overexpressed FLAG-METTL3. LC–MS analysis of endogenous METTL14 revealed two distinct stretches of RGG/RG motifs being methylated (405–426 and 445–456), with the first stretch exhibiting clustered dimethylation (Figure S2C), similar to the proteome profiling results. EPZ015666 and MS023 treatment also resulted in a significant signal reduction in sDMA and aDMA signal, respectively (Fig. 1D). PRMT5 knockdown by shRNA further confirmed the findings from inhibitor treatment.

Taken together, we have identified and confirmed the presence of both sDMA and aDMA in the C terminal RGG/RG repeat of METTL14.

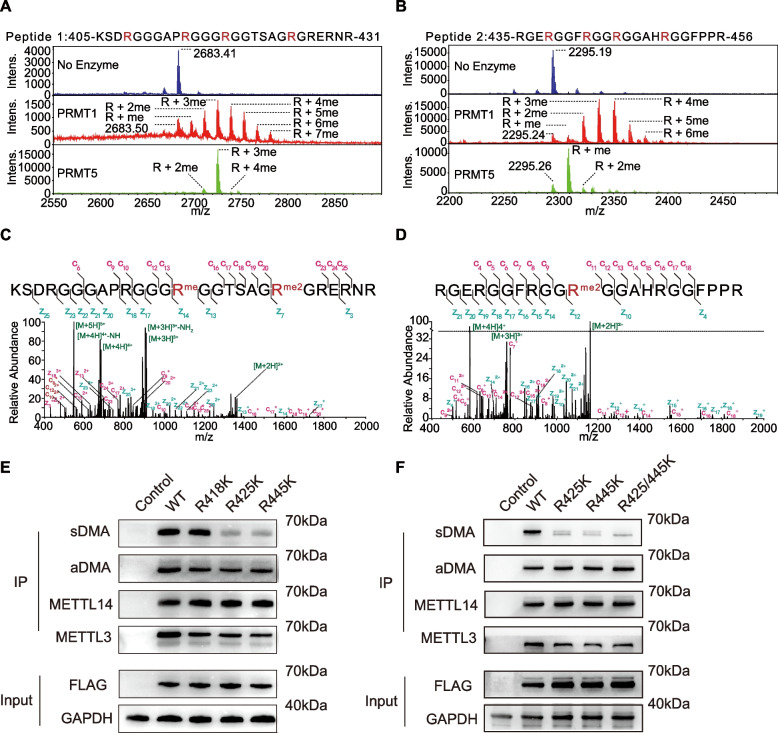

PRMT5 specifically methylates R425 and R445 within the RGG/RG motifs of METTL14

aDMA modification in METTL14 was reported to affect its substrate binding affinity [14]. In order to elucidate the functional importance of sDMA modification in METTL14, we first tried to identify sDMA modification sites in METTL14. In vitro methyl transfer reactions were carried out using peptides derived from the RGG/RG motifs of METTL14 (peptide 1: 405–431 and peptide 2: 435–456). Given PRMT5 is the major enzyme responsible for sDMA formation and PRMT1 was reported to catalyze aDMA modifications within this domain, we purified the human PRMT5:MEP50 complex as well as PRMT1 for the in vitro reactions. Notably, MALDI-TOF analysis of PRMT1 reaction products revealed a spectrum characterized by multiple methylation events on both peptides, whereas PRMT5 reactions yielded one major product for each peptide (Fig. 2A and B). MS analysis of the main product from PRMT5 reaction with peptide 1 revealed monomethylation at R418 and dimethylation at R425 (Fig. 2C), and that with peptide 2 revealed dimethylation at R445 (Fig. 2D). It’s worth noting that the arginine residues modified by PRMT5 in this context are preceded by glycine residues, aligning with the known substrate preference of PRMT5 [31].

Fig. 2.

R425 and R445 of METTL14 were modified with sDMA by PRMT5. A-B MALDI-TOF analysis of arginine methylation reactions catalyzed by PRMT1 and PRMT5 using METTL14-derived peptide 1 and 2. C MS/MS spectrum shows the localization of monomethylated R418 and dimethylated R425 in PRMT5 reaction product with peptide 1. D MS/MS spectrum shows the localization of dimethylated R445 in PRMT5 reaction product with peptide 2. E–F Western blot analysis of aDMA and sDMA modifications in WT and the RK mutant of METTL14

To confirm the specific sDMA sites at the C-terminal tail of METTL14 in cellular contexts, we constructed METTL14 mutants with either R418, R425, or R445 mutated to lysine individually, mimicking sDMA-deficient mutation of the protein. Immunoprecipitated R425K and R445K mutants showed a marked decrease in sDMA levels, but not the R418K mutant (Fig. 2E). Notably, the mutant harboring R425K and R445K double mutations exhibited a complete loss of sDMA (Fig. 2F). These observations suggest that R425 and R445 of METTL14 are likely to be modified with sDMA in the backdrop of aDMA modifications in this region. R418 could be an aDMA site, consistent with a previous report that R418 was modified by PRMT3 [16].

Collectively, our findings provide compelling evidence that the C-terminal tail of METTL14 undergoes site-specific sDMA modifications at R425 and R445 by PRMT5, amidst the backdrop of numerous aDMA modifications in the region. However, it requires further investigation into the functional significance of sDMA in METTL14 and if the intertwined sDMA and aDMA is a general phenomenon in highly methylated RGG/RG motifs.

sDMA Modifications at R425 and R445 of METTL14 modulate the enzymatic activity of the methyltransferase complex in vitro and regulate the expression of known m6A substrates in the cell

To understand the functional significance of sDMA modifications on the C terminal tail of METTL14, we first analyzed the impact of sDMA on the catalytic activity of the METTL3:METTL14 complex, the key m6A writer enzyme complex. The complex containing wild-type (WT) or sDMA-deficient METTL14 mutant (R425K or R445K single or double mutant) was purified to homogeneity and an in vitro RNA methyltransferase activity assay was conducted using a synthetic RNA oligo [8]. m6A addition was monitored by LC–MS after RNA digestion. As shown in Fig. 3A, either single or double mutant showed reduced catalytic efficiencies than WT METTL14, suggesting that sDMA modifications at R425 and R445 of METTL14 likely play a regulatory role in the catalytic activity of the METTL3:METTL14 complex.

Fig. 3.

sDMA Modifications at R425 and R445 of METTL14 modulate methyltransferase activity in vitro and in the cell. A Kinetic characterization of WT METTL14 and the RK mutants by an in vitro methyltransferase assay. Vmax and Kcat for the protein complex were calculated and shown in the table (n = 3 technical replicates). B Western blot analysis of BRD4, SP1, and c-MYC expression in HEK293T cells upon METTL14 knockdown by shRNAs. C Western blot and quantitative densitometry analysis of BRD4, SP1, and c-MYC expression in HEK293T cells overexpressing WT or the R425/445K mutant of METTL14 with endogenous METTL14 knocked down. Data are presented as mean values ± SD (n = 3 independent experiments). D Western blot analysis of BRD4, SP1 and c-MYC expression in HEK293T cells upon METTL3 inhibitor STM2457, Type I PRMT inhibitor MS023 or PRMT5 inhibitor treatment. E Western blot and quantitative densitometry analysis of BRD4, SP1, and c-MYC expression in HEK293T cells upon YTHDF1 knockdown by shRNAs. Data are presented as mean values ± SD (n = 3 independent experiments). F RIP-qPCR analysis of YTHDF1 binding to mRNA of BRD4, SP1, and c-MYC in HEK293T cells expressing WT or the R425/445K mutant of METTL14. For B, E and F, P-values were calculated by unpaired t test. For D, P-values were calculated by one-way Anova. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001

We next investigated the impact of sDMA modification in METTL14 on m6A substrate expression. BRD4, SP1, and c-MYC are known m6A substrates and their gene expressions were reported to be regulated by METTL3:METTL14 complex activity [32]. Consistent with the known role of METTL14, we observed a substantial reduction in the protein levels of BRD4, SP1, and c-MYC upon METTL14 knockdown by shRNAs in HEK293T cells (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, overexpressing WT METTL14 could restore the protein levels of these known m6A substrates (Fig. 3C). However, the R425K/R445K double mutant (R425/445 K mutant) does not have the same effect. The finding indicates that site-specific sDMA modifications in METTL14 could have a positive impact on the catalytic activity of the methyltransferase complex within the cell, thereby influencing the expression levels of m6A substrates. Similarly, PRMT5 inhibition by EPZ015666 in HEK293T cells also resulted in reduced protein levels of BRD4, SP1, and c-MYC (Fig. 3D).

The three YTHDF proteins, YTHDF1, YTHDF2 and YTHDF3, are the primary readers of RNA m6A modification in mammals and are largely responsible for m6A-mediated regulation of cellular translation by promoting mRNA translation or degradation [33–35]. We next investigated if a specific YTHDF is responsible for the decreased protein expression of BRD4, SP1, and c-MYC resulting from sDMA deficiency in METTL14. We show that YTHDF1 knockdown by shRNAs caused a significant decrease in the expression levels of BRD4, SP1, and c-MYC in HEK293T (Fig. 3E), while YTHDF2 or YTHDF3 knockdown does not have the same effect (Figure S3A, S3B). This result suggests that YTHDF1 is the main m6A reader responsible for the regulation of BRD4, SP1, and c-MYC expression in HEK293T. The result is also consistent with the reported function of YTHDF1 in translation promotion in HEK293T cells [36].

Furthermore, through RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) coupled with RT-qPCR, we evaluated the binding of YTHDF1 to selected mRNAs in cells expressing WT METTL14 or the R425/445 K mutant. Compared to WT METTL14, less mRNAs transcribed from BRD4, SP1 and c-MYC genes, bind to YTHDF1 (Fig. 3F) in the R425/445 K mutant cells, indicating potential lower m6A densities in these mRNAs. Therefore, the reduced binding of selected mRNAs to YTHDF1 in METTL14 mutant cells could be responsible for the decreased protein levels of BRD4, SP1 and c-MYC in HEK293T cells.

Taken together, we show that sDMA modifications at R425 and R445 of METTL14 modulate the methyltransferase activity and the expression of known m6A substrates in the cell, possibly via the reduced binding of mRNA to the m6A reader YTHDF1.

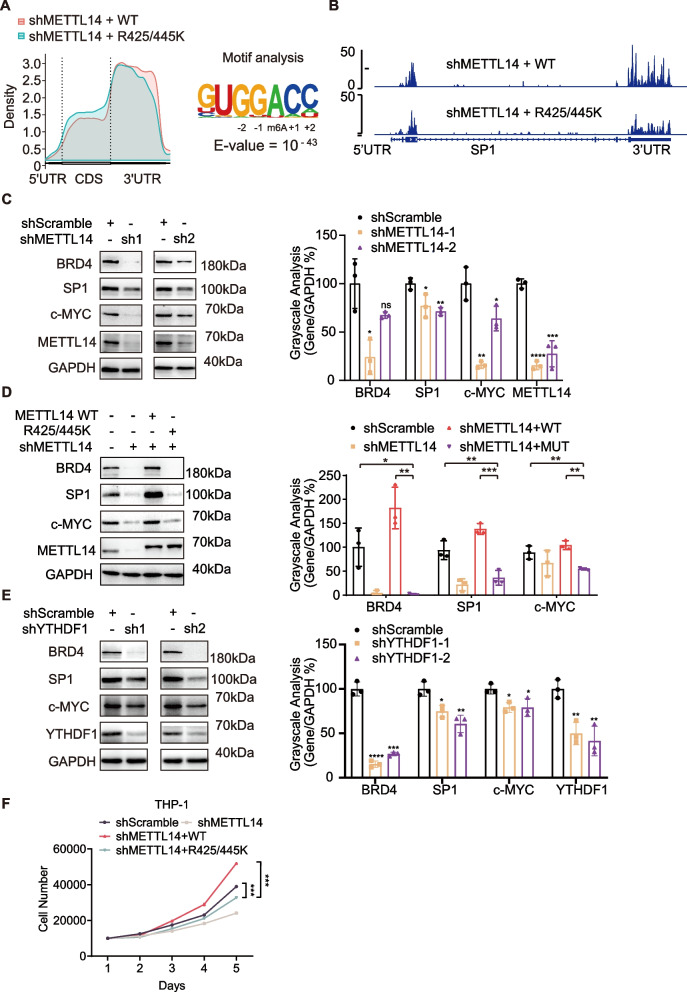

Specific sDMA modifications in METTL14 affect the expression levels of proteins essential for AML proliferation

To investigate the potential role of sDMA modification in METTL14 in tumor progression, we first analyzed the survival relevance of genes involved in sDMA and m6A modification in multiple common cancers. Among the analyzed cancer types, AML is most likely affected by sDMA and m6A modifications, as the expression of multiple genes involved in the process is negatively correlated with overall survival (Figure S4A). It was reported that dysregulation of c-MYC, BRD4 and SP1 were involved in AML pathogenesis and their expressions are regulated by m6A modification in their mRNAs [7]. The involvement of c-MYC in AML tumorigenesis through transcriptional regulation is well studied [37]. Suppression of BRD4 through shRNA-mediated knockdown or inhibition by small molecules has exhibited potent antiproliferative effects across various AML subtypes [38]. SP1, known for its overexpression in numerous cancer types, is correlated with unfavorable prognosis and represents a potential target for cancer therapy [39]. Therefore, we next investigated the impact of sDMA modification in METTL14 on the expression of these essential proteins and their regulatory mechanism in THP-1, an AML cell line.

We first performed MeRIP-seq analysis, which is m6A-specific RNA immunoprecipitation followed by RNA-sequencing, to investigate the genome-wide effect of sDMA modifications on METTL14 in THP-1 cells. WT METTL14 or the R425/445 K mutant was overexpressed in THP-1 cells with endogenous METTL14 knocked down by shRNAs (Figure S4B). As shown in Fig. 4A, m6A modifications in both WT and R425/445 K mutant cells predominantly localized to the coding regions and 3' untranslated regions (3'UTRs) at the consensus motif UGG(m6A)C, which was consistent with previous studies [40]. Importantly, the number of m6A peaks on RNA decreased from 17,693 m6A peaks in the WT cells to 9437 peaks in the R425/445 K mutant cells. Distribution analysis showed downregulation in m6A density in the 3'UTR of the global transcriptome in cells expressing R425/445 K mutant of METTL14 (Fig. 4A). The results align with the decreased methyltransferase activity of METTL3:METTL14 complex with sDMA site mutations and suggest that sDMA modifications at R425 and R445 of METTL14 contribute to the global m6A levels and the distribution of m6A peaks in the transcriptome of AML cells.

Fig. 4.

Specific sDMA modifications in METTL14 affect cellular m6A distribution and the expression levels of proteins essential for AML proliferation. A Distribution of all called m6A peaks on poly-A + enriched RNAs from METTL14 KD THP-1 cells overexpressing WT or the R425/445K mutant of METTL14. B Genomic visualization of the normalized m6A-meRIP signal for SP1 in METTL14 KD THP-1 cells overexpressing WT or the R425/445K mutant METTL14. C Western blot and quantitative densitometry analysis of of BRD4, SP1, and c-MYC expression in THP-1 cells upon METTL14 knockdown by shRNAs. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 independent experiments). D Western blot and quantitative densitometry analysis of BRD4, SP1, and c-MYC expression in THP-1 cells overexpressing WT or the R425/445K mutant of METTL14 with endogenous METTL14 knocked down. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 independent experiments). E Western blot and quantitative densitometry analysis of BRD4, SP1, and c-MYC expression in THP-1 cells upon YTHDF1 knockdown by shRNAs. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 independent experiments). F Cell growth curves of THP-1 cells overexpressing WT or the R425/445K mutant of METTL14 with endogenous METTL14 knocked down. For C and E, P-values were calculated by unpaired t test. For D and F, P-values were calculated by one-way Anova. ns: not significant, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001

Next, we examined the m6A peaks of known m6A substrates such as BRD4, SP1, and c-MYC in the MeRIP-seq results. Notably, the m6A peaks of BRD4, SP1 and c-MYC were significantly reduced, especially in the 3’UTR region, upon sDMA site mutations in METTL14 (Fig. 4B, and Figure S4C) without changing their mRNA levels (Figure S4D). Western blot analysis confirmed that the expression levels of BRD4, SP1, and c-MYC were significantly reduced upon METTL14 knockdown by shRNAs in THP-1 (Fig. 4C). Overexpressing wild-type METTL14, but not the R425/445 K mutant, could restore their expression levels (Fig. 4D). Similarly, PRMT5 knockdown by shRNAs resulted in their reduced expressions (Figure S4E). Additionally, YTHDF1 knockdown also resulted in decreased expression of these essential proteins in THP-1 (Figs. 4E and S4F), similar to what we showed in HEK293T, suggesting that YTHDF1 could be the reader protein responsible for the regulation of these m6A substrate expression in THP-1. Our results support findings from prior studies that YTHDF1 is an integral regulator of AML progression by regulating the expression of m6A-modified mRNAs [35].

Furthermore, we have performed the growth curve analysis of THP-1 with METTL14 knockdown and rescued with WT or the R425/445 K mutant. Compared to WT METTL14, the R425/445 K mutant shows a significantly reduced growth rate (Fig. 4F), suggesting the functional importance of R425 and R445 methylation in the proliferation of the AML cells.

Collectively, these results confirmed the significance of sDMA modifications at R425 and R445 of METTL14 in modulating the expression of these important cancer-related genes through a post-transcriptional mechanism in AML cells.

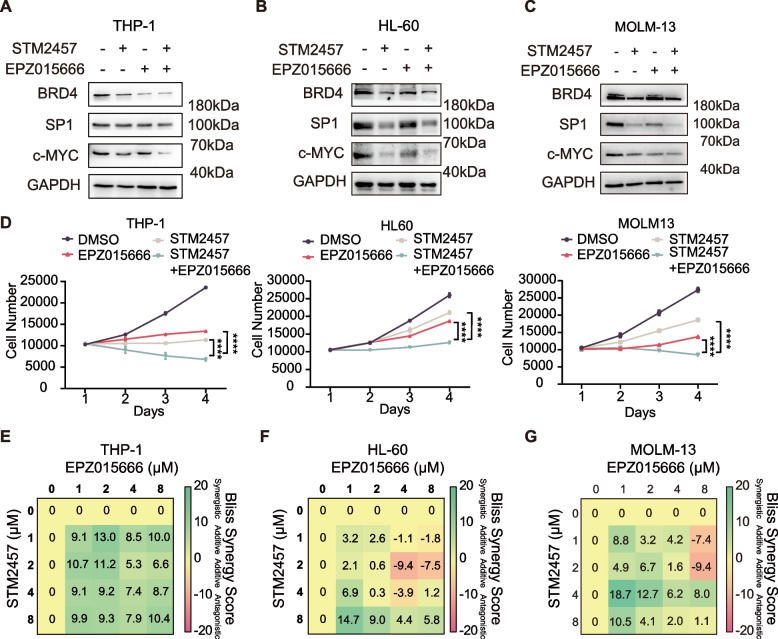

Combined inhibition of PRMT5 and METTL3 further reduces the proliferation of AML cells

It is widely recognized that single drug regimens exhibit constrained anti-neoplastic efficacy due to their inability to eradicate all malignant cells and the propensity of cancer cells to develop resistance against single agents. Consequently, there is a growing imperative to explore drug combinations, which allow the use of lower doses of each constituent drug to achieve higher efficacy than single drug administration. METTL3 inhibition by small molecule STM2457 was shown to inhibit the proliferation of AML cells by reducing the expression of several oncogenic proteins [32]. Since PRMT5-catalyzed sDMA modification on METTL14 also regulate the expression of BRD4, SP1 and c-MYC, we speculate that the combination of METTL3 and PRMT5 inhibition would further reduce the expression of these essential genes and showing improved antiproliferation activity in AML.

To test our hypothesis, we first examined the effect of METTL3 inhibitor STM2457 and PRMT5 inhibitor EPZ015666 on oncogene expression in multiple AML cell lines, including THP-1, HL-60, and MOLM-13. The proliferation of these cell lines are known to be sensitive to BRD4 and c-MYC expression [41]. We showed that while either inhibitor treatment reduced the expression levels of BRD4 and c-MYC in all three tested AML cell lines, the combination of two led to a more pronounced reduction than either inhibitor alone (Fig. 5A-C).

Fig. 5.

Combined inhibition of PRMT5 and METTL3 activity results in a further reduction in BRD4, SP1, and c-MYC expression and the proliferation of AML cell lines. A-C Western blot analysis of BRD4, SP1, and c-MYC expression in THP-1, HL-60 and MOLM-13 cells treated with STM2457 and EPZ015666, either alone or in combination. D Growth curves of cells treated with STM2457 and EPZ015666, either alone or in combination. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 independent experiments). P-values were calculated by One-way Anova, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001. E–G Bliss analysis of combined teatment of EPZ01566 and STM2457 in THP-1, HL-60 and MOLM-13 cells. Scores greater than 10, between −10 and 10, and less than −10 are considered synergistic, additive, and antagonistic, respectively. Green box indicates the synergistic dose region by Bliss independence analysis

We then assessed the antiproliferative activities of these two compounds either alone or in combination in the three AML cell lines. IC50s were obtained for the two compounds in three cell lines using CCK8 proliferation assay (Figure S5) and we chose 10 μM for each compound in the combination study. As shown in the growth curves (Fig. 5D), either compound exhibited certain antiproliferative activity and their combination produced more pronounced inhibition in all three cell lines, which is consistent with the western blot results. Bliss independence model [42] for the analysis of the antiproliferation effect of these two compounds in a concentration matrix also confirmed the additive effect of the two drugs (Fig. 5E-G). However, further research is needed to validate these findings in vivo and to determine if the combination of STM2457 and EPZ015666 could be a more effective treatment for cancer than either drug alone.

Nevertheless, our findings highlight a potential application of modulating the expression of key proteins through m6A modification by simultaneously inhibiting m6A methyltransferase complex and the major sDMA methyltransferase PRMT5 in the treatment of AML.

Discussion

The m6A modification of RNA has been shown to play an important role in the pathogenesis of AML [43]. As an essential member of the m6A writer complex, the abnormal expression of METTL14 has been reported in primary AML samples and in AML cell lines. By depositing m6A marks on its substrate mRNAs, METTL14 positively modulates the expression of oncogenic MYB and MYC, implicating its role in leukemogenesis [44]. Therefore, it is critical to understand the regulatory mechanism on METTL14 and the activity of the methyltransferase complex in order to find therapeutic strategies for AML involving m6A.

Wang and colleagues have documented the arginine methylation of the RGG/RG motif of METTL14 by PRMT1, implicating its regulatory role in m6A deposition in mammalian cells [15]. Our study has revealed the presence of both types of dimethylarginine modifications in this region through western blot analysis of immunoprecipitated METTL14 and in vitro peptide-based enzymatic reactions. Notably, our discovery of sDMA modification at two specific arginines within METTL14 suggests that, between PRMT1-mediated aDMA and PRMT5-mediated sDMA modifications within the same RGG/RG motif, PRMT5 displays a high sequence specificity while PRMT1 is more promiscuous. Previous studies have revealed RGG/RG motifs as the preferred substrates for both PRMT1 and PRMT5 [45]. This prompts the question of whether aDMA and sDMA sites are intertwined in the RG-rich motif or if these two major arginine methyltransferases compete for the same site within the motif. In the case of METTL14, PRMT5 modifies specific sites at the C terminal RGG/RG motifs, and PRMT1 deposits methyl groups to the rest arginine sites. It’s worth noting that the arginines modified by PRMT5 in METTL14, namely R425 and R445, are invariably preceded by a glycine residue, consistent with the stringent requirement of a glycine proximal to sDMA sites catalyzed by PRMT5, as opposed to a modest preference for proline at the −1 position by PRMT1 [46].

However, it still remains a question how these two types of methylation affect methyltransferase activity. From our in vitro enzyme kinetic data, site-specific sDMA modification may not significantly affect the affinity between the enzyme and the RNA substrate, however, it may affect how the substrate is presented to the catalytic residue and thus the catalytic efficiency. The study by Z. Wang et al. [15] suggested lower binding affinity with methylation deficient mutations in METTL14. It is possible that clustered aDMA modification in the region may modulate the enzyme’s substrate binding affinity while specific sDMA modification might be involved in the precise positioning of the substrate for catalysis. However, it would require detailed structural analysis to fully understand the intricate interplay between these two types of modification.

The coexistence of aDMA and sDMA within the same RGG/RG motif of METTL14 may signify a recurring phenomenon in RNA-binding proteins. Previous studies have revealed the co-existence of sDMA and aDMA in the central RGG/RG motif of SERBP1, an RNA-binding protein involved in translational regulation, and loss of either methylation caused increased recruitment of SERBP1 to stress granule under oxidative stress [20]. METTL14 and SERBP1 are likely not the only cases where the RGG/RG motifs are modified with both types of dimethylation. The intertwined sDMA and aDMA modification on the RGG/RG motif may form a recognition pattern for RNA binding and both methylation types fine-tune the functions of their modified substrates. Interestingly, our findings indicate that the loss of symmetric dimethylation at R425 and R445 reduces the catalytic activity of the METTL3:METTL14 complex, similar to the effects observed with aDMA modification on METTL14 [13–15]. In our study, treatment with MS023, a pan-type I PRMT inhibitor, in HEK293T cells also resulted in a reduction in the expression of BRD4, SP1, and c-MYC, although less pronounced than that from PRMT5 inhibitor treatment (Fig. 3D). The result suggests that although sDMA modifications may occur at fewer sites, they could represent critical regulatory loci that significantly impact protein–protein or protein-RNA interactions, as implied by the functional roles of RGG/RG motif-containing proteins.

Conclusion

In conclusion, through the employment of mass spectrometry and biochemical assays, we have confirmed the co-presence of sDMA and aDMA modifications on the RGG/RG motifs located at the C-terminal region of METTL14. Notably, the site-specific sDMA modification at R425 and R445 of METTL14 has been shown to positively modulate the catalytic efficacy of the METTL3:METTL14 complex and play a regulatory role in essential gene expression through m6A deposition in cancer cells such as AML.

Supplementary Information

Abbreviations

- aDMA

Asymmetric Dimethylarginine

- AGC

Automatic Gain Control

- AML

Acute Myeloid Leukemia

- BSA

Bovine Serum Albumin

- CFX96

C1000 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium

- DEPC

Diethyl Pyrocarbonate

- DNase

Deoxyribonuclease

- DNTPs

Deoxyribonucleoside Triphosphates

- EDTA

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid

- EThcD

Electron Transfer/Higher-energy Collisional Dissociation

- ETCiD

Electron Transfer/Higher-energy Collisional Dissociation

- ETD

Electron Transfer Dissociation

- FBS

Fetal Bovine Serum

- FA

Formic Acid

- GEO

Gene Expression Omnibus

- HCD

Higher-energy Collisional Dissociation

- HEK293T

Human Embryonic Kidney 293T cells

- IgG

Immunoglobulin G

- LC–MS/MS

Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry

- m6A

N6-Methyladenosine

- m6A-seq

N6-Methyladenosine sequencing

- MALDI-TOF

Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-of-Flight

- MMA

Monomethylarginine

- MRM

Multiple Reaction Monitoring

- PAGE

Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis

- PBS

Phosphate-Buffered Saline

- PE

Paired-End

- PRM

Parallel Reaction Monitoring

- PRMT1

Protein Arginine Methyltransferase 1

- PRMT5

Protein Arginine Methyltransferase 5

- PRMTs

Protein Arginine Methyltransferases

- PTMs

Post-translational modifications

- PVDF

Polyvinylidene Fluoride

- qPCR

Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

- RIP

RNA Immunoprecipitation

- RPMI 1640

Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 Medium

- RT

Room Temperature

- shRNAs

Short Hairpin RNAs

- sDMA

Symmetric dimethylarginine

- TBST

Tris-Buffered Saline with Tween

- YTHDF1

YTH Domain Family Protein 1

Authors’ contributions

Y.L.Z. performed experiments and analyzed data. Y.Y.Y. performed experiments and prepared the manuscript. R.Z. and L.Z.L. performed experiments. H.J.T analyzed RNA-seq data. Y.M., and Y.Q.Y. contributed to in the design, coordination and manuscript editing. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Key Research and Development Program, Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2021YFA1200903), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32271497, 32001044 and 92478126) and Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Drug Nonclinical Evaluation and Research (2023B1212070029).

Data availability

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (https://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the iProX partner repository [47] with the dataset identifier PXD054570. Sequences were deposited in BioProject under the accession number PRJNA1145927.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yuyu You, Email: youyy8@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Yang Mao, Email: maoyang3@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Yanqiu Yuan, Email: yuanyq8@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Jia G, Fu Y, He C. Reversible RNA adenosine methylation in biological regulation. Trends Genet. 2013;29:108–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ma C, Chang M, Lv H, Zhang ZW, Zhang W, He X, et al. RNA m6A methylation participates in regulation of postnatal development of the mouse cerebellum. Genome Biol. 2018;19:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shi H, Wei J, He C. Where, when, and how: context-dependent functions of RNA methylation writers, readers, and erasers. Mol Cell. 2019;74:640–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao BS, Roundtree IA, He C. Post-transcriptional gene regulation by mRNA modifications. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017;18:31–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He L, Li H, Wu A, Peng Y, Shu G, Yin G. Functions of N6-methyladenosine and its role in cancer. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barbieri I, Tzelepis K, Pandolfini L, Shi J, Millán-Zambrano G, Robson SC, et al. Promoter-bound METTL3 maintains myeloid leukaemia by m6A-dependent translation control. Nature. 2017;552:126–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vu LP, Pickering BF, Cheng Y, Zaccara S, Nguyen D, Minuesa G, et al. The N6-methyladenosine (m6A)-forming enzyme METTL3 controls myeloid differentiation of normal hematopoietic and leukemia cells. Nat Med. 2017;23:1369–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu J, Yue Y, Han D, Wang X, Fu Y, Zhang L, et al. A METTL3–METTL14 complex mediates mammalian nuclear RNA N6-adenosine methylation. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:93–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ping X-L, Sun B-F, Wang L, Xiao W, Yang X, Wang W-J, et al. Mammalian WTAP is a regulatory subunit of the RNA N6-methyladenosine methyltransferase. Cell Res. 2014;24:177–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Du Y, Hou G, Zhang H, Dou J, He J, Guo Y, et al. SUMOylation of the m6A-RNA methyltransferase METTL3 modulates its function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:5195–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schöller E, Weichmann F, Treiber T, Ringle S, Treiber N, Flatley A, et al. Interactions, localization, and phosphorylation of the m6A generating METTL3-METTL14-WTAP complex. RNA. 2018;24:499–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun H-L, Zhu AC, Gao Y, Terajima H, Fei Q, Liu S, et al. Stabilization of ERK-Phosphorylated METTL3 by USP5 increases m6A methylation. Mol Cell. 2020;80:633-647.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu X, Wang H, Zhao X, Luo Q, Wang Q, Tan K, et al. Arginine methylation of METTL14 promotes RNA N6-methyladenosine modification and endoderm differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat Commun. 2021;12:3780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang J, Wang Z, Inuzuka H, Wei W, Liu J. PRMT1 methylates METTL14 to modulate its oncogenic function. Neoplasia. 2023;42:100912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Z, Pan Z, Adhikari S, Harada BT, Shen L, Yuan W, et al. m6A deposition is regulated by PRMT1-mediated arginine methylation of METTL14 in its disordered C-terminal region. EMBO J. 2021;40:e106309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y, Wang C, Guan X, Ma Y, Zhang S, Li F, et al. PRMT3‐mediated arginine methylation of METTL14 promotes malignant progression and treatment resistance in endometrial carcinoma. Adv Sci. 2023;10:2303812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larsen SC, Sylvestersen KB, Mund A, et al. Proteome-wide analysis of arginine monomethylation reveals widespread occurrence in human cells. Science signaling. 2016;9:rs9–rs9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blanc RS, Richard S. Arginine methylation: the coming of age. Mol Cell. 2017;65:8–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bedford MT, Clarke SG. Protein arginine methylation in mammals: who, what, and why. Mol Cell. 2009;33:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu L, Ye Z, Zhang R, Olsen JV, Yuan Y, Mao Y. ETD-based proteomic profiling improves arginine methylation identification and reveals novel PRMT5 substrates. J Proteome Res. 2024;23:1014–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yuan BF. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry for analysis of RNA adenosine methylation. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1562:33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen S, Zhou Y, Chen Y, Gu J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:i884–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cui X, Wei Z, Zhang L, Liu H, Sun L, Zhang SW, et al. Guitar: an R/bioconductor package for gene annotation guided transcriptomic analysis of RNA‐related genomic features. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:8367534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heinz S, Benner C, Spann N, Bertolino E, Lin YC, Laslo P, et al. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol Cell. 2010;38:576–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu G, Wang L-G, He Q-Y. ChIPseeker: an R/Bioconductor package for ChIP peak annotation, comparison and visualization. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:2382–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chan-Penebre E, Kuplast KG, Majer CR, Boriack-Sjodin PA, Wigle TJ, Johnston LD, et al. A selective inhibitor of PRMT5 with in vivo and in vitro potency in MCL models. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11:432–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duncan KW, Rioux N, Boriack-Sjodin PA, Munchhof MJ, Reiter LA, Majer CR, et al. Structure and property guided design in the identification of PRMT5 tool compound EPZ015666. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2016;7:162–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eram MS, Shen Y, Szewczyk M, Wu H, Senisterra G, Li F, et al. A potent, selective, and cell-active inhibitor of human type i protein arginine methyltransferases. ACS Chem Biol. 2016;11:772–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dhar S, Vemulapalli V, Patananan AN, Huang GL, Di Lorenzo A, Richard S, et al. Loss of the major type I arginine methyltransferase PRMT1 causes substrate scavenging by other PRMTs. Sci Rep. 2013;3:1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boisvert FM, Côté J, Boulanger MC, Richard S. A proteomic analysis of arginine-methylated protein complexes. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2003;2:1319–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yankova E, Blackaby W, Albertella M, Rak J, De Braekeleer E, Tsagkogeorga G, et al. Small-molecule inhibition of METTL3 as a strategy against myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 2021;593:597–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zaccara S, Jaffrey SR. A Unified model for the function of YTHDF proteins in regulating m6A-modified mRNA. Cell. 2020;181:1582-1595.e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paris J, Morgan M, Campos J, Spencer GJ, Shmakova A, Ivanova I, et al. Targeting the RNA m6A reader YTHDF2 selectively compromises cancer stem cells in acute myeloid leukemia. Cell Stem Cell. 2019;25:137-148.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hong Y-G, Yang Z, Chen Y, Liu T, Zheng Y, Zhou C, et al. The RNA m6A reader YTHDF1 is required for acute myeloid leukemia progression. Cancer Res. 2023;83:845–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zou Z, He C. The YTHDF proteins display distinct cellular functions on m6A-modified RNA. Trends Biochem Sci. 2024;49:611–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Delgado MD, Albajar M, Gomez-Casares MT, Batlle A, León J. MYC oncogene in myeloid neoplasias. Clin Transl Oncol. 2013;15:87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zuber J, Shi J, Wang E, Rappaport AR, Herrmann H, Sison EA, et al. RNAi screen identifies Brd4 as a therapeutic target in acute myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 2011;478:524–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beishline K, Azizkhan-Clifford J. Sp1 and the “hallmarks of cancer.” FEBS J. 2015;282:224–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dominissini D, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Schwartz S, Salmon-Divon M, Ungar L, Osenberg S, et al. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature. 2012;485:201–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsherniak A, Vazquez F, Montgomery PG, Weir BA, Kryukov G, Cowley GS, et al. Defining a cancer dependency map. Cell. 2017;170:564-576.e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bliss CI. The calculation of microbial assays. Bacteriol Rev. 1956;20:243–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yankova E, Aspris D, Tzelepis K. The N6-methyladenosine RNA modification in acute myeloid leukemia. Curr Opin Hematol. 2021;28:80–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weng H, Huang H, Wu H, Qin X, Zhao BS, Dong L, et al. METTL14 inhibits hematopoietic stem/progenitor differentiation and promotes leukemogenesis via mRNA m6A modification. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;22:191-205.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Musiani D, Bok J, Massignani E, Wu L, Tabaglio T, Ippolito MR, et al. Proteomics profiling of arginine methylation defines PRMT5 substrate specificity. Sci Signal. 2019;12:eaat8388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kölbel K, Ihling C, Kühn U, Neundorf I, Otto S, Stichel J, et al. Peptide backbone conformation affects the substrate preference of protein arginine methyltransferase I. Biochemistry. 2012;51:5463–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen T, Ma J, Liu Y, Chen Z, Xiao N, Lu Y, et al. iProX in 2021: connecting proteomics data sharing with big data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50:D1522–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (https://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the iProX partner repository [47] with the dataset identifier PXD054570. Sequences were deposited in BioProject under the accession number PRJNA1145927.