Abstract

Nicotine exposure in the context of smoking or vaping worsens airway function. Although nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) are commonly thought to exert effects through the peripheral nervous system, we previously showed that airway smooth muscle (ASM) expresses them, particularly α7 subtype nAChR (α7nAChR), with functional effects on contractility and metabolism. However, the mechanisms of nAChR regulation and downstream effects in ASM are not fully understood. Using ASM cells from people without asthma versus people with mild to moderate asthma, we tested the hypothesis that nAChR-specific endoplasmic reticulum (ER) chaperones, resistance to inhibitors of cholinesterase 3 (RIC-3) and transmembrane protein 35A (TMEM35A) promote cell surface localization of α7nAChR with downstream influence on its functionality: effects exacerbated by inflammation. We found that mild to moderate asthma and exposure to proinflammatory cytokines relevant to asthma promote chaperone and α7nAChR expression in ASM. Downstream, ER stress was linked to nicotine/α7nAChR signaling, where RIC-3 and TMEM35 regulate nicotine-induced ER stress, intracellular Ca2+ regulation, and ASM cell proliferation. Overall, our data highlight the importance α7nAChR chaperones in mediating and modulating nicotine effects in ASM toward airway contractility and remodeling.

Keywords: ASM, nicotinic receptor, chaperones, ER stress, cell proliferation

Clinical Relevance

Nicotine exposure exacerbates airway function, particularly alpha7 subtype (α7nAChR) with functional effects on contractility and metabolism. Using human airway smooth muscle (ASM) cells, we tested the hypothesis that nAChR-specific endoplasmic reticulum chaperones resistance to inhibitors of cholinesterase 3 (RIC-3) and transmembrane protein 35A (TMEM35A) promote cell surface localization of α7nAChR with downstream influence on its functionality: effects exacerbated by inflammation. Overall, our data highlights the importance of intracellular α7nAChR chaperones in mediating and modulating nicotine effects in ASM towards airway contractility and remodeling.

Airway smooth muscle (ASM) plays key roles in promoting airway contractility and remodeling (e.g., cell proliferation, fibrosis) (1–3) and is thus important in diseases such as asthma (4–6). Accordingly, factors such as environmental exposures that exacerbate asthma can mediate their effects through ASM. Because of the increased use of vaping products that deliver nicotine, and continued smoking of tobacco products, there is interest in understanding how nicotine can trigger or exacerbate asthma (7–9). Nicotine effects are well known to be mediated through nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs)—ligand-gated ion channels that regulate the flow of ions in the short term but can also genomically affect cellular structure and function in the long term (10–13). In the airways, although functional nAChRs have been commonly thought to work through cholinergic receptors in the peripheral nervous system, we previously showed that they are expressed in human ASM and that their expression is increased in people with asthma (14, 15). Furthermore, we found that nAChRs can modulate cytosolic intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) as well as mitochondrial structure and function (16)—effects that are increased in ASM from people with asthma. However, the mechanisms by which nAChRs themselves are regulated in ASM are unknown, as are their long-term influences towards airway remodeling.

Nicotinic nAChRs comprise homopentameric and heteropentameric combinations of α and β subunits that consist of four transmembrane (TM) domains, M1–M4, which fold and assemble in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) before being transported to the cell surface (8, 10, 11). Recent studies have shown that processing and intracellular transportation of nAChRs require specialized chaperones such as resistance to inhibitors of cholinesterase 3 (RIC-3) and transmembrane protein 35A (TMEM35A), also known as Nicotinic Cholinergic Receptor Regulator or Novel Acetylcholine Receptor Chaperone (12, 17). RIC-3 activates itself serving as a magnet to pull individual prefolded α7 subtype nAChR (α7nAChR) subunits in the ER through dimerization of its coiled-coil domains (17). Knockout of TMEM35 in mice results in the complete absence of α7nAChR in the brain (18). Cotransfection of RIC-3 and TMEM35 in HEK cells increases surface expression and function of α7nAChR, as seen with α-bungarotoxin binding (19). TMEM35 interacts with the molecular machinery in the early stages of α7nAChR insertion into the ER membrane, later joined by the RIC-3 to stimulate the composition of the complete nAChR unit. Thus, the critical role of these chaperones is clear, but whether and how these chaperones play a role in nAChR in ASM in the context of airway structure/function, inflammation or asthma are entirely unknown.

As a critical intracellular organelle responsible for Ca2+ storage, protein assembly, folding and transport to the cell surface/membrane, and protein homeostasis (20, 21), the ER, in turn, is sensitive to changes in cell stress, oxygen, Ca2+ and energy levels (22), leading to ER stress and an imbalance in misfolded/unfolded proteins (23–25). In turn, to maintain homeostasis, ER stress is detected through ER TM sensors (26–28) that are activated to restore normal ER functioning, collectively termed the unfolded protein response (UPR). Such pathways are well described (23, 25) and include autophosphorylation of inositol-requiring enzyme 1a (IRE1α) with downstream splicing of X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1) (29, 30), protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase (PERK), which mediates downstream phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) (31, 32), and translocation of activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) to the Golgi (33, 34). Although the role of ER stress has been explored in diseases such as asthma, the interactions between nicotine action by means of α7nAChR and ER stress remain unexplored. Furthermore, interactions between ER stress and mitochondria also play important roles in the airway, and thus, given the potential for α7nAChR to influence mitochondria, the potentially bidirectional relationships between nicotine/α7nAChR and the ER and its chaperones become important.

In the present study, we used ASM from people without asthma versus people with mild to moderate asthma to explore the hypothesis that nAChR-specific ER chaperones RIC-3 and TMEM35 promote cell-surface localization of α7nAChR with downstream influence on its functionality—effects that are exacerbated by inflammation, focusing on ER stress, Ca2+ regulation, and cell proliferation.

Methods

Human Airway Samples

All protocols involving human lung tissue and primary human ASM cells were approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (#08-002518 and #16-009655). Bronchial ASM cells were isolated and cultured using previously established procedures with experiments limited to less than five passages of subculture and cells being serum deprived for at least 24 hours, along with consistent verification of smooth muscle phenotype (14). Samples were from people without asthma and people with mild to moderate asthma, including those with a history of smoking in either group. (For additional patient details, see Table E1 in the data supplement.)

Cell Treatments

After serum starvation, cells were treated with nicotine (10 μM), TNF-α (20 ng/ml), IL-13 (50 ng/ml), tunicamycin (1 μM), tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA; 0.5 mM), α7nAChR agonist PNU (100 nM), α7nAChR antagonist MLA (100 nM), or TGF-β (2 ng/ml) as appropriate. For qRT-PCR and protein analyses, ASM cells from people with and without asthma were treated in the presence or absence of nicotine for 48 hours. Concentrations of nicotine, proinflammatory cytokines, inducers, and inhibitors used are consistent with previous work, as outlined elsewhere (see Table E2) (14, 16, 35).

Immunostaining and qRT-PCR Analysis

The detailed procedure is as outlined in the data supplement.

Protein Analyses

For the detailed procedure, see Table E3.

siRNA Transfection

The siRNA formulations were included in the study after verification of knockdown efficiency, as shown previously (16).

shRNA Transduction

The detailed procedure is as outlined in the data supplement. shRNA-transduced ASM cells were included in the study after verification of knockdown efficiency, as shown elsewhere (see Figure E1).

Real-Time [Ca2+]i Imaging

Previously described calibration procedures were used to quantify [Ca2+]i from fura-2-AM fluorescence levels (36, 37). Further details are provided in the data supplement.

Cell Proliferation Assay

Additional details regarding proliferation assay are provided in the data supplement. Proliferation changes were separately verified using protein levels of PCNA and Ki67.

ER Staining

ASM cells were rinsed with Hanks’ balanced salt solution and incubated for 30 minutes with 1 μM prewarmed ER-Tracker blue-white DPX (ThermoFisher Scientific; catalog no. E12353) before the cells were imaged with the Nikon Eclipse Ti imaging system.

ER Stress Response Assay

ER stress response was dynamically monitored using the Green/Red Cell Stress Assay (Montana Molecular, catalog no. U0901G) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed on ASM cells from at least 5 patients and performed in duplicate for each patient sample. Statistical comparisons were made using either Student’s t test or one-way ANOVA as appropriate, followed by Tukey’s post hoc multiple comparisons test using GraphPad Prism, Version 10.2.0 for Windows (GraphPad Software; www.graphpad.com). Statistical significance was tested at a level of P < 0.05. All values are expressed as means ± SEM (minimum to maximum, showing all points).

Results

α7nAChR Chaperones in Human ASM

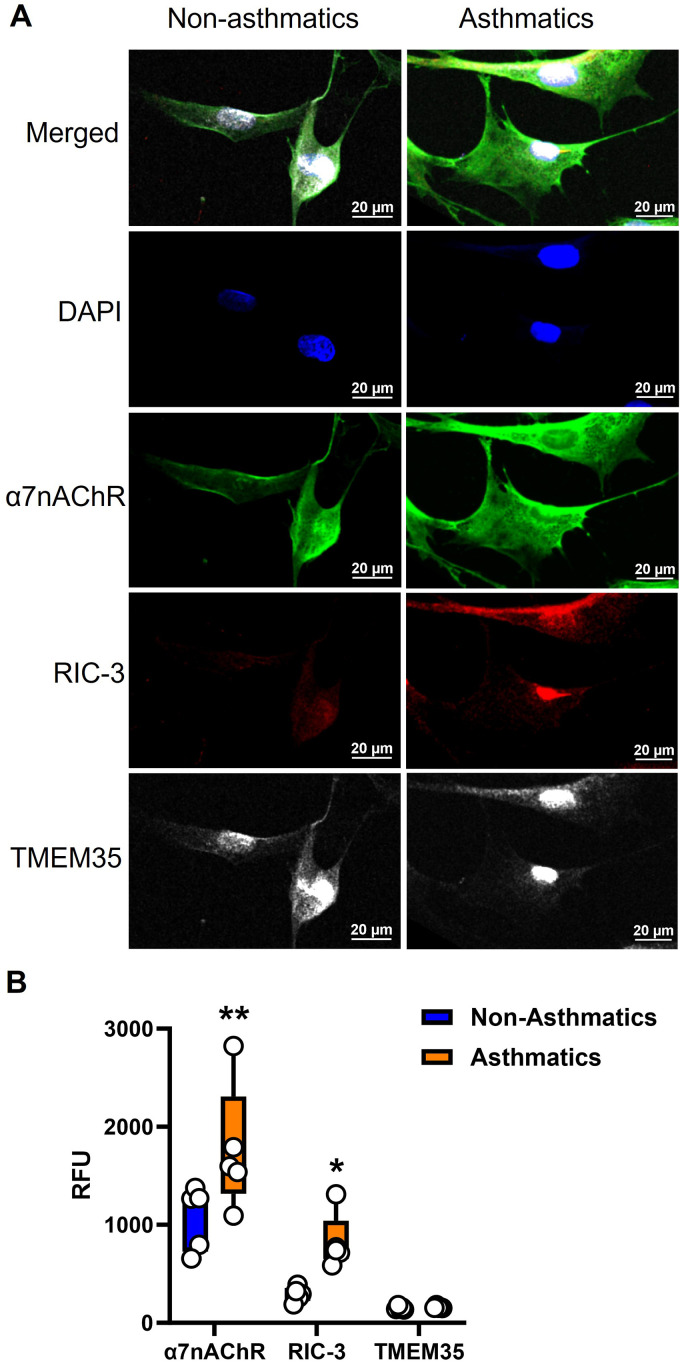

In paraformaldehyde-fixed ASM cells, immunofluorescence staining (Figure 1A) showed that α7nAChR, RIC-3, and TMEM35 are all expressed in human ASM (Figure 1B), with cytoplasmic localization for RIC-3 and TMEM35 but both intracellular and membrane localization of α7nAChR. Additionally, α7nAChR, RIC-3, and TMEM35 are differentially expressed in human ASM (P < 0.01 for α7nAChR and P < 0.05 for RIC-3; Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Expression of nicotinic α7 receptor (α7nAChR) chaperones resistance to inhibitors of cholinesterase 3 (RIC-3) and transmembrane protein 35A (TMEM35A) in human airway smooth muscle (ASM). (A and B) Paraformaldehyde-fixed cells were immunostained for α7nAChR (AF-488), RIC-3 (AF-555) and TMEM35 (AF-647). α7nAChR and its chaperones were expressed in human ASM, with cytoplasmic localization for RIC-3 and TMEM35 but both intracellular and membrane localization of α7nAChR. Additionally, α7nAChR, RIC-3, and TMEM35 were differentially expressed. Representative images from five independent samples from people with and without asthma (asthmatic and nonasthmatic samples, respectively). Scale bars, 20 μm. *P < 0.05, versus nonasthmatic samples. **P < 0.01, versus nonasthmatic samples.

Effect of Nicotine, Asthma, and Inflammation on RIC-3 and TMEM35

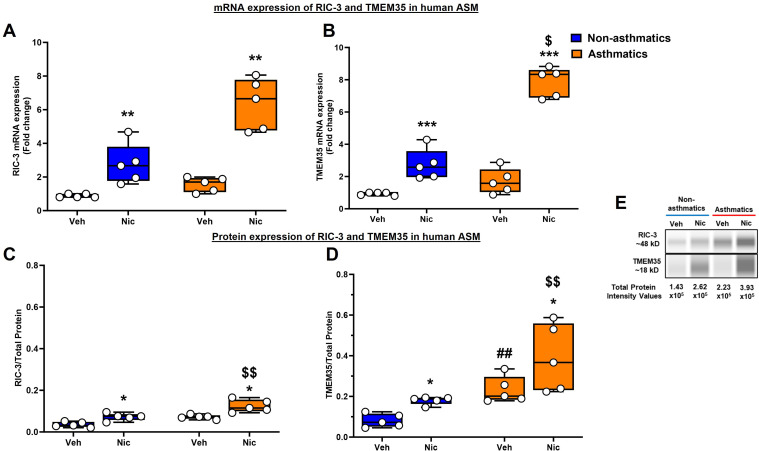

mRNA expression of both RIC-3 and TMEM35 was significantly elevated upon treatment with nicotine, albeit more significantly in ASM cells (from people with asthma) treated with nicotine (P < 0.01 for RIC-3, and P < 0.001 for TMEM-35; Figures 2A and 2B). We reconfirmed this using JESS analysis for RIC-3 and TMEM35 protein expression (P < 0.05; Figures 2C and 2D), where there were significant differences in ASM cells treated with nicotine. It is interesting that people with asthma showed increased baseline expression of TMEM35 protein compared with people without asthma (P < 0.01): exacerbated with nicotine exposure (P < 0.05 for TMEM35 mRNA, and P < 0.01 for RIC-3 and TMEM35 proteins). Representative digital electropherogram images are shown in Figure 2E.

Figure 2.

mRNA and protein expression of RIC-3 and TMEM35 in ASM from people with and without asthma. (A and B) mRNA expression. (C and D) Total protein expression. qRT-PCR and simple western analysis of (A and C) RIC-3 and (B and D) TMEM35 showed higher expression of RIC-3 and TMEM35 in nicotine-treated ASM cells. This increase was further accentuated in ASM samples from people with asthma. (E) Representative electropherograms. n = 5 in each group. *P < 0.05, versus respective vehicle. **P < 0.01, versus respective vehicle. ***P < 0.001, versus respective vehicle. ##P < 0.01, versus nonasthmatic vehicle. $P < 0.05, versus nonasthmatic nicotine. $$P < 0.01, versus nonasthmatic nicotine. Nic = nicotine; Veh = vehicle.

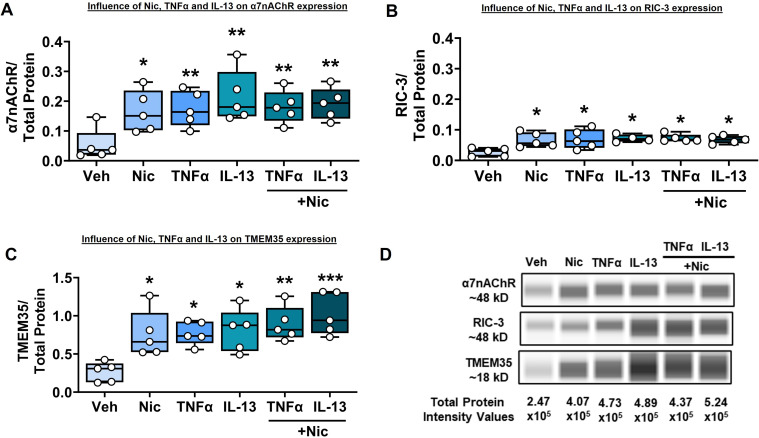

ASM cells were exposed to nicotine, TNF-α, or IL-13 alone as well as cytokines in the presence of nicotine. Nicotine by itself significantly increased expression of α7nAChR, RIC-3, and TMEM35 (P < 0.05; Figures 3A–3C). TNF-α and IL-13 each also significantly increased the expression of α7nAChR and the chaperones (P < 0.01 for α7nAChR, and P < 0.05 for RIC-3 and TMEM35). However, nicotine did not potentiate the effect of cytokine stimuli on α7nAChR (P < 0.01) or RIC3 (P < 0.05) expression but did potentiate TMEM35 expression (P < 0.01 for TNFα, P < 0.001 for IL-13) in the presence of cytokines. Representative electropherograms are shown in Figure 3D.

Figure 3.

Effect of nicotine and proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-13 on α7nAChR, RIC-3, and TMEM35 expression. (A–C) ASM cells that were treated with nicotine alone, TNF-α, or IL-13 ± nicotine showed an increase in the expression of (A) α7nAChR and chaperones (B) RIC-3 and (C) TMEM35. (D) Representative electropherograms. n = 5 in each group. *P < 0.05, versus vehicle. **P < 0.01, versus vehicle. ***P < 0.001, versus vehicle.

Nicotine Induces ER Stress in Human ASM

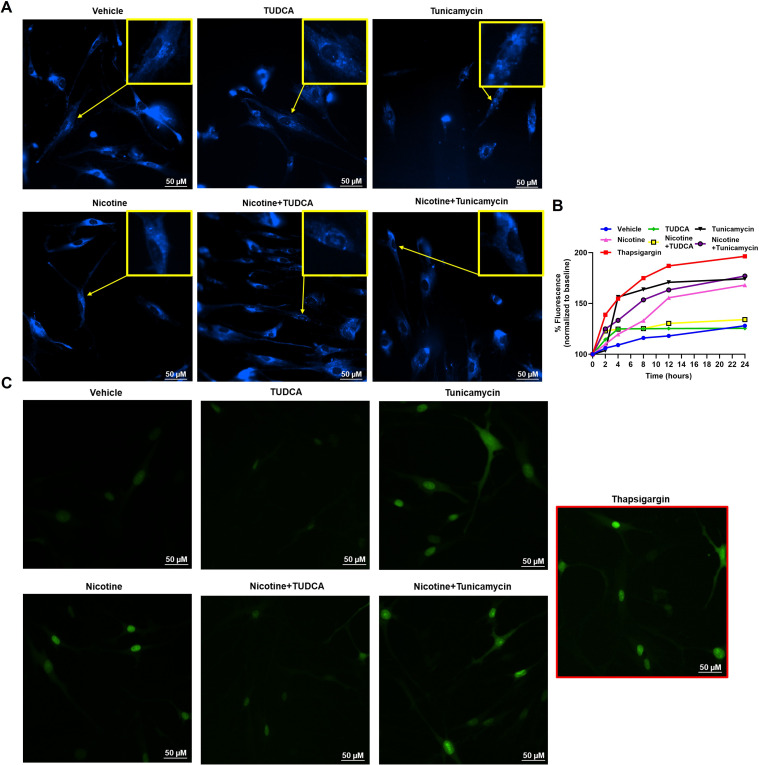

We exposed ASM cells to inducers of ER stress (thapsigargin, tunicamycin) or inhibitors (TUDCA), alone or in combination with nicotine, to assess changes in ER stress using complementary methods. Vehicle exposure showed intact whole ER assembly, whereas cells exhibiting ER stress showed more punctate ER assembly and granulated structures (Figure 4A). We quantified ER stress using a cell-based assay to measure the increase in percent fluorescence (GFP) with respect to similar treatments as mentioned earlier. We used thapsigargin (1 μM) as a positive control for ER stress response. We observed comparable increase in percent fluorescence with tunicamycin and nicotine compared with thapsigargin. TUDCA alone did not exhibit any ER stress, as expected. Nicotine did not consistently accentuate the effect of tunicamycin. However, nicotine in the presence of TUDCA did not increase ER stress, with a trend similar to that of vehicle. (Figure 4B). Representative images of cells quantified for the cell stress assay are as shown (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Effect of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress induction on ER assembly and stress in human ASM. (A) ASM cells that were treated with nicotine, ER stress inducer, tunicamycin, or the ER stress inhibitor tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA) showed changes in ER assembly. (B) Impact of ER stress on ER assembly was further measured using an ER stress assay and recording the percentage of fluorescence changes in treatments compared with baseline (vehicle). Thapsigargin was used as a positive control for ER stress induction. (C) Representative images used for quantification of the cell stress assay. Representative images and graphs are from five independent samples. Scale bars, 50 μm.

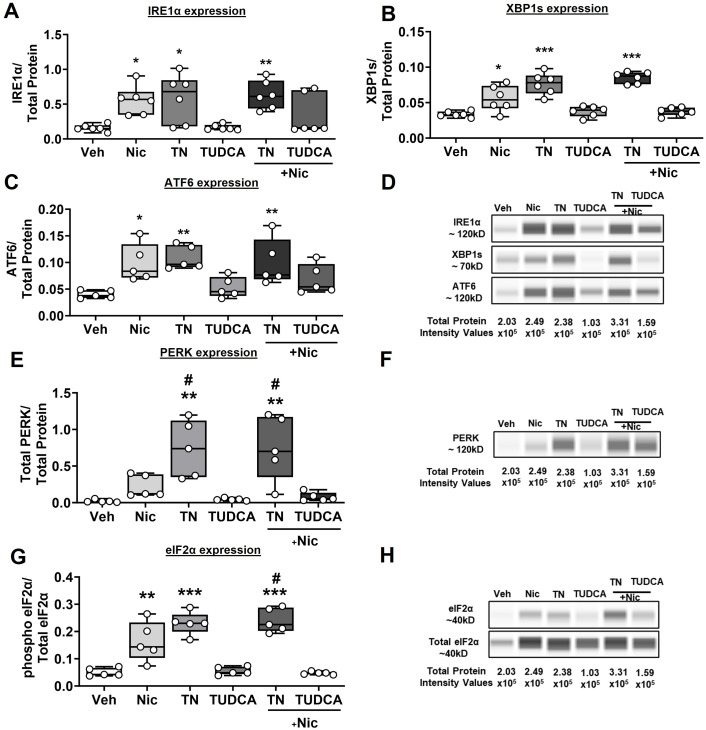

In terms of ER stress/UPR markers, nicotine by itself induces the activation of IRE1α (P < 0.05; Figure 5A), XBP1s (P < 0.05; Figure 5B), and ATF6 (P < 0.05; Figure 5C). Tunicamycin as an ER stress inducer showed robust activation of all three ER stress proteins (P < 0.05 for IRE1α, P < 0.001 for XBP1s, and P < 0.01 for ATF6). TUDCA, as expected, showed values similar to those of baseline/vehicle. Nicotine in the presence of tunicamycin further amplified the protein expression of IRE1α (P < 0.01), XBP1s (P < 0.001), and ATF6 (P < 0.01), compared with vehicle. On the other hand, TUDCA abrogated nicotine-induced ER stress. Representative electropherograms are shown in Figure 5D. Separately, there were no significant changes in total PERK expression in nicotine- and TUDCA-exposed samples, whereas total PERK expression increased with tunicamycin and in the presence of nicotine (P < 0.01; Figure 5E). However, nicotine did not potentiate the effect of tunicamycin on PERK but the effect was significantly high compared with that of nicotine alone (P < 0.05). Similarly, nicotine significantly increased phosphorylated eIF2α, comparable with the effect of tunicamycin (P < 0.01), and potentiated the effect of the latter (P < 0.001). Tunicamycin in the presence of nicotine also elevated the expression of phosphorylated eIF2α compared with nicotine alone (P < 0.05). TUDCA, as expected, showed no changes with respect to eIF2α phosphorylation, and it blunted the effects of nicotine (Figure 5G). Representative electropherograms are shown in Figures 5F and 5H.

Figure 5.

Expression profile of different ER stress markers. ASM cells that were treated with nicotine, TN, or TUDCA ± nicotine were tested for the different ER stress markers, (A) IRE1α, (B) XBP1s, (C) ATF6, (E) PERK, and (G) eIF2α. (D, F, and H) Representative electropherograms for (D) IRE1α, (F) PERK, and (H) eIF2α. n = 5–6 in each group. *P < 0.05, versus vehicle. **P < 0.01, versus vehicle. ***P < 0.001, versus vehicle. #P < 0.05, versus nicotine. Nic = nicotine; TN = tunicamycin.

Role of Chaperones in Regulating Functional Effects of Nicotine in Human ASM

We investigated whether the effects of nicotine involve the α7nAChR chaperones RIC-3 and TMEM35. We created RIC-3 and TMEM35 knockdown cell lines using shRNA lentiviral particles. Knockdown efficiency was verified using western blot analysis and immunocytochemistry (Figure E1).

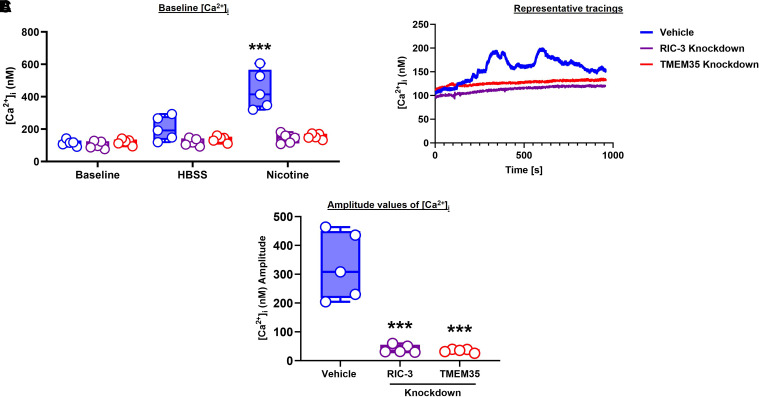

In fura-2–loaded cells, baseline [Ca2+]i was not different between vehicle control and shRNA groups (P < 0.001; Figure 6A). Exposure to nicotine alone resulted in [Ca2+]i responses in the vehicle group but was essentially eliminated in the shRNA groups. Representative tracings are shown in Figure 6B, and average amplitudes are shown in Figure 6C (P < 0.001).

Figure 6.

Role of RIC-3 and TMEM35 in intracellular calcium. (A and C) Real-time calcium imaging experiments were performed to determine the changes in (A) baseline [Ca2+]I and (C) average amplitude values. (B) Representative tracings. n = 5 in each group. ***P < 0.001, versus baseline/vehicle. HBSS = Hanks’ balanced salt solution.

We performed the CyQUANT proliferation assay with ASM cells (from people with and without asthma) exposed to nicotine, PNU (α7nAChR agonist), MLA (α7nAChR inhibitor), and nicotine in the presence of PNU or MLA. We used TGF-β as a positive control in our proliferation assays (P < 0.001). ASM from people with asthma did show a trend toward increasing cell proliferation, albeit not a significant one compared with that seen in their nonasthmatic counterparts. We observed increases in cell proliferation for regular ASM cells exposed to nicotine alone (P < 0.01) and the α7nAChR agonist PNU (P < 0.001). We did not find any significant changes in cell proliferation for cells exposed to the α7nAChR antagonist MLA. Nicotine in the presence of PNU further amplified cell proliferation in the case of the ASM population from people with and without asthma (P < 0.001). Although MLA alone did not show any significant changes in cell proliferation, nicotine in the presence of MLA did induce some—however, not significant—increase in cell proliferation (Figure 7A). In α7nAChR knockdown cells, nicotine or α7nAChR agonism did increase proliferation but not to the same extent as that of the nontransfected cells (P < 0.05 for nicotine alone, and P < 0.01 for PNU alone; Figure 7B). PNU in the presence of nicotine also increased the percentage of cell proliferation (P < 0.01) in ASM from people with and without asthma. MLA by itself, as well as in the presence of nicotine, did not contribute to any significant changes in cell proliferation.

Figure 7.

Functional effects of α7nAChR and chaperones RIC-3 and TMEM35 in ASM cell proliferation. Effects of nicotine activation of α7nAChR and chaperones RIC-3 and TMEM35 were determined by the proliferation assay. (A) Negative siRNA/shRNA cells were treated with nicotine alone, PNU alone, MLA alone, PNU ± nicotine, or MLA ± nicotine to determine the percentage of cell proliferation at baseline for ASM in both nonasthmatic and asthmatic samples. (B) Separately, siRNA α7nAChR cells were also included in a proliferation assay to determine the percentage of cell proliferation, which was comparatively lesser compared with the percentage of cell proliferation at baseline. (C and D) Similarly, RIC-3 and TMEM35 shRNA cells also showed some increase in cell proliferation values but seemingly lesser compared with cells at baseline. (E–H) Simple western analysis of proliferative markers was performed to corroborate our findings in cell proliferation assay for (E) PCNA and (G) Ki67. (F and H) Representative electropherograms for (F) PCNA and (H) Ki67. n = 5–6 nonasthmatic and asthmatic ASM samples in each group. *P < 0.05, versus vehicle. **P < 0.01, versus vehicle. ***P < 0.001, versus vehicle. #P < 0.05, versus nicotine. MLA = methyllycaconitine citrate (α7nAChR antagonist); PNU = PNU 282987 (selective α7nAChR agonist); TGFβ = transforming growth factor beta (mitogenic cytokine).

With RIC-3 shRNA knockdown, increases in cell proliferation in response to nicotine or PNU were blunted (P < 0.05 for nicotine, and P < 0.01 for PNU in ASM from people with asthma only; Figure 7C). PNU in the presence of nicotine did not seem to further accentuate nicotine’s effects on cell proliferation in people without asthma (P < 0.05), but it was amplified in ASM of people with asthma (P < 0.01). Again, MLA did not produce any significant changes in cell proliferation in RIC-3 knockdown ASM cells. Similarly, TMEM35 knockdown by means of shRNA also blunted the effects of nicotine and PNU (P < 0.05 for nicotine and PNU in ASM of people with asthma, and P < 0.01 for PNU alone in ASM of people without asthma), (Figure 7D). Here, PNU in the presence of nicotine further increased cell proliferation in ASM of people with asthma (P < 0.01). As expected, TMEM35 knockdown ASM cells did not produce any significant deviations in cell proliferation upon stimulation with MLA alone or in the presence of nicotine.

The CyQUANT proliferation data were verified using protein expression of the proliferative markers PCNA and Ki67. Nicotine significantly increased PCNA (P < 0.05; Figure 7E) and Ki67 (P < 0.05; Figure 7G) expression, as did the α7nAChR agonist PNU (P < 0.05 for PCNA, and P < 0.01 for Ki67). MLA alone did not produce any changes that were comparable with those of vehicle, although MLA was significantly lower in PCNA when compared with nicotine alone (P < 0.05), indication the robustness of MLA—not the amount or quantity—to block the effect of α7nAChR on proliferation. PNU in the presence of nicotine also upregulated the proliferative marker, especially in the case of Ki67 (P < 0.01). MLA blunted the effect of nicotine on PCNA and Ki67 expression, although not significantly enough. Representative electropherograms are shown in Figures 7F and 7H.

Discussion

Inflammation, hypercontractility, and proliferative remodeling are hallmarks of airway diseases such as asthma (4, 38). Asthma is also exacerbated by tobacco and smoke exposure (e.g., cigarette smoke) (13, 39, 40). Nicotine, the major addictive component of cigarette smoke, binds to nAChRs, leading to an activated conformational state. nAChRs are pentameric structures that contain several subunits ranging from α1 to α10, β1 to β4, γ, δ, and ε. α7nAChR, with its α7 subunits, assembles into a fully functional receptor. The rationale for our focus on α7nAChR is due to its ability to induce critical downstream signaling effects such as enhancing [Ca2+]i and contractility, disrupting mitochondrial energetics, and potentially contributing to enhanced airway hyperresponsiveness and airway remodeling, as shown previously (13, 41). As one of the most widely studied ligand-gated ion channels, α7nAChR leads to a series of cellular responses, including, but not limited to, calcium influx, neurotransmitter release, synaptic plasticity, and transmission of excitatory stimuli (12, 42). We and others have shown that α7nAChR signaling also induces other cellular events, such as inflammation, autophagy, necrosis, and apoptosis (14–16, 43). However, the upstream regulation of α7nAChR and the role of its chaperones, RIC-3 and TMEM35, have not been explored, which we demonstrate in this study, with a focus on enhancing the surface expression of α7nAChR as well as its downstream effects on ER stress, calcium and proliferation.

RIC-3 and TMEM35 are known chaperones of the α7nAChR, and the structure activity relationships of these chaperones to α7nAChR are also relatively well established. Previous studies suggest that the expression of α7nAChR is largely determined and facilitated by RIC-3 and TMEM35 (44–46). However, the role of these chaperones in the context of nonneuronal cells is yet to be determined. Studies have reported a perinuclear localization of RIC-3 and suggest that it is a resident protein of the ER (47, 48). Expression of RIC-3 dramatically increases the expression of α7nAChR in C. elegans (49). In this regard, our results, which show the reduction of α7nAChR when RIC-3 expression is suppressed, are consistent, as are the correlative data showing that, in the presence of inflammation where RIC-3 expression increases, α7nAChR is increased as well. With regard to TMEM35, knockout of TMEM35 in mice results in the complete absence of α7nAChR in the brain (18). Our results with TMEM35 suppression and changes in α7nAChR are also consistent. Cotransfection of RIC-3 and TMEM35 in HEK cells increases surface expression and function of α7nAChR, as seen with α-bungarotoxin binding (19). Whether RIC-3 and TMEM35 are equally important chaperones that regulate the expression of α7nAChR in ASM and whether they play differential roles in the context of inflammation or asthma remain to be established. However, our results showing greater levels of RIC-3 in ASM from people with asthma would suggest that at least at baseline, this chaperone may be more important. It is interesting that exposure to nicotine per se increased RIC-3 and, more so, TMEM35, particularly in people with asthma, suggesting that nicotine can induce expression of its own receptor and setting the stage for exacerbated downstream effects of α7nAChR in the context of inflammation or disease. Additionally, we note that such effects of nicotine and chaperones are observed in the ASM of smokers, providing relevance to the idea of α7nAChR effects in the context of smoking and vaping.

As the largest cellular organelle spanning from the nuclear envelope to the cell membrane (20, 22), the ER has several functions including, but not limited to, calcium storage, detoxification of chemicals, lipid synthesis, the site of protein folding, and posttranslational modification of proteins. These activities are critical for maintaining cellular homeostasis and responses under conditions of excessive protein folding (i.e., ER stress) (25). With ER stress, intracellular pathways (UPRs) are activated to restore cellular homeostasis. (27). ER stress engages the UPR to reduce cellular load, thereby maintaining cell viability and function (26). There is now evidence, including from our group, that ER stress occurs in ASM and is increased in the presence of inflammation and asthma. In this study, we demonstrate an upstream role for α7nAChR per se and for its chaperones. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation is responsible for inflammation-induced ER stress (24). On the basis of increased ROS generation in asthma, we explored the influence of major cytokines TNF-α and IL-13. In this study, we linked increases in ROS generation on exposure to nicotine to ER stress, using chemical chaperones such as TUDCA, which have also gained interest as potential therapeutic agents including in asthma, as in the case of TUDCA (50). Notably, we show that nicotine influences the UPR arms IRE1α, XBP1s, ATF6, PERK, and eIF2α and that nicotine and the α7nAChR agonist PNU can induce ASM cell proliferation, an effect dependent on the chaperones RIC-3 and TMEM35. Furthermore, such effects are increased in the presence of inflammation and asthma. Overall, mitigation of the inflammation-induced α7nAChR chaperones RIC-3 and TMEM35 and the nicotine-exacerbated ER stress mechanism in human ASM may represent a novel target for therapeutic intervention against asthma. Further studies are needed to elucidate the detailed mechanisms of crosstalk between α7nAChR and the UPR arms to induce ER stress. Also, whether ER stress itself induces human ASM cell proliferation is unknown and a topic for future investigation.

The effects of α7nAChR, RIC3, and TMEM35 on cell proliferation are significant in contributing toward our understanding of airway remodeling in the context of smoking/vaping and asthma. If nicotine, by means of α7nAChR, can promote cell proliferation and airway thickening (effects that are potentially also present in other airway cell types), then alleviating α7nAChR expression or effects has a substantial influence on the detrimental effects of smoking or vaping.

Although our study links α7nAChR, its chaperones, ER stress, and cell proliferation in ASM from people with and without asthma (and including smokers), some limitations should be recognized. α7nAChR can have several other effects, including on metabolism, which have not been further explored in the context of chaperones or ER stress and which may all be interlinked. Given relatively small sample sizes, we did not perform subanalyses regarding the influence of asthma severity, smoking, or medications that may influence α7nAChR expression or effects. Regardless of these limitations, our data clearly highlights the importance of α7nAChR in ASM towards understanding the parameters of airway contractility and remodeling in the context of smoking/vaping and of asthma.

Supplemental Materials

Footnotes

Supported by Foundation for the National Institutes of Health grants R01-HL146705 (V.S.), R01-HL142061 (C.M.P. and Y.S.P.), and R01-HL088029 (Y.S.P.) and an American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship Grant 24POST1241979 (N.A.B.).

Author Contributions: N.A.B., V.S., Y.S.P. and C.M.P. designed research studies and contributed to writing the manuscript drafts. N.A.B., M.A.T., B.K., B.T.S., and S.K.H. conducted experiments, N.A.B., M.A.T., and B.K. acquired and analyzed data. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

This article has a data supplement, which is accessible at the Supplements tab.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2024-0194OC on September 5, 2024

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Lundback B, Backman H, Lotvall J, Ronmark E. Is asthma prevalence still increasing? Expert Rev Respir Med . 2016;10:39–51. doi: 10.1586/17476348.2016.1114417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ellis AK, Soliman M. Year in review: upper respiratory diseases. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol . 2015;114:168–169. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Borkar NA, Combs CK, Sathish V. Sex steroids effects on asthma: a network perspective of immune and airway cells. Cells . 2022;11 doi: 10.3390/cells11142238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kistemaker LEM, Prakash YS. Airway innervation and plasticity in asthma. Physiology (Bethesda) . 2019;34:283–298. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00050.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Prakash YS. Emerging concepts in smooth muscle contributions to airway structure and function: implications for health and disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol . 2016;311:L1113–L1140. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00370.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borkar NA, Sathish V. In: Sex-based differences in lung physiology. Silveyra P, Tigno XT, editors. Cham: 2021. Sex steroids and their influence in lung diseases across the lifespan; pp. 39–72. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Laviolette SR, van der Kooy D. The neurobiology of nicotine addiction: bridging the gap from molecules to behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci . 2004;5:55–65. doi: 10.1038/nrn1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wittenberg RE, Wolfman SL, De Biasi M, Dani JA. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and nicotine addiction: a brief introduction. Neuropharmacology . 2020;177:108256. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2020.108256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lucchiari C, Masiero M, Veronesi G, Maisonneuve P, Spina S, Jemos C, et al. Benefits of e-cigarettes among heavy smokers undergoing a lung cancer screening program: randomized controlled trial protocol. JMIR Res Protoc . 2016;5:e21. doi: 10.2196/resprot.4805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dani JA. Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor structure and function and response to nicotine. Int Rev Neurobiol . 2015;124:3–19. doi: 10.1016/bs.irn.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hogg RC, Raggenbass M, Bertrand D. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: from structure to brain function. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol . 2003;147:1–46. doi: 10.1007/s10254-003-0005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhao Y, Liu S, Zhou Y, Zhang M, Chen H, Xu HE, et al. Structural basis of human α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor activation. Cell Res . 2021;31:713–716. doi: 10.1038/s41422-021-00509-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Borkar NA, Thompson MA, Bartman CM, Khalfaoui L, Sine S, Sathish V, et al. Nicotinic receptors in airway disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol . 2024;326:L149–L163. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00268.2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Borkar NA, Roos B, Prakash YS, Sathish V, Pabelick CM. Nicotinic α7 acetylcholine receptor (α7nAChR) in human airway smooth muscle. Arch Biochem Biophys . 2021;706:108897. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2021.108897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Khalfaoui L, Mukhtasimova N, Kelley B, Wells N, Teske J, Roos B, et al. Functional α7 nicotinic receptors in human airway smooth muscle increase intracellular calcium concentration and contractility in asthmatics. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol . 2023;325:L17–L29. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00260.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Borkar NA, Thompson MA, Bartman CM, Sathish V, Prakash YS, Pabelick CM. Nicotine affects mitochondrial structure and function in human airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol . 2023;325:L803–L818. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00158.2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Loring RH. Speculation on how RIC-3 and other chaperones facilitate α7 nicotinic receptor folding and assembly. Molecules . 2022;27:4527. doi: 10.3390/molecules27144527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kennedy BC, Dimova JG, Dakoji S, Yuan LL, Gewirtz JC, Tran PV. Deletion of novel protein TMEM35 alters stress-related functions and impairs long-term memory in mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol . 2016;311:R166–R178. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00066.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Couturier S, Bertrand D, Matter JM, Hernandez MC, Bertrand S, Millar N, et al. A neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit (α7) is developmentally regulated and forms a homo-oligomeric channel blocked by α-BTX. Neuron . 1990;5:847–856. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90344-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schwarz DS, Blower MD. The endoplasmic reticulum: structure, function and response to cellular signaling. Cell Mol Life Sci . 2016;73:79–94. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-2052-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Giorgi C, Marchi S, Pinton P. The machineries, regulation and cellular functions of mitochondrial calcium. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol . 2018;19:713–730. doi: 10.1038/s41580-018-0052-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Luo B, Lee AS. The critical roles of endoplasmic reticulum chaperones and unfolded protein response in tumorigenesis and anticancer therapies. Oncogene . 2013;32:805–818. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen X, Shi C, He M, Xiong S, Xia X. Endoplasmic reticulum stress: molecular mechanism and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct Target Ther . 2023;8:352. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01570-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bhattarai KR, Riaz TA, Kim HR, Chae HJ. The aftermath of the interplay between the endoplasmic reticulum stress response and redox signaling. Exp Mol Med . 2021;53:151–167. doi: 10.1038/s12276-021-00560-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Almanza A, Carlesso A, Chintha C, Creedican S, Doultsinos D, Leuzzi B, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress signalling—from basic mechanisms to clinical applications. FEBS J . 2019;286:241–278. doi: 10.1111/febs.14608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Galluzzi L, Yamazaki T, Kroemer G. Linking cellular stress responses to systemic homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol . 2018;19:731–745. doi: 10.1038/s41580-018-0068-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hetz C, Zhang K, Kaufman RJ. Mechanisms, regulation and functions of the unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol . 2020;21:421–438. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-0250-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Malhotra JD, Kaufman RJ. ER stress and its functional link to mitochondria: role in cell survival and death. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol . 2011;3:a004424. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Itzhak D, Bright M, McAndrew P, Mirza A, Newbatt Y, Strover J, et al. Multiple autophosphorylations significantly enhance the endoribonuclease activity of human inositol requiring enzyme 1α. BMC Biochem . 2014;15:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-15-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang C, Chang Y, Zhu J, Ma R, Li G. Dual role of inositol-requiring enzyme 1α-X-box binding protein 1 signaling in neurodegenerative diseases. Neuroscience . 2022;505:157–170. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2022.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Liu Z, Lv Y, Zhao N, Guan G, Wang J. Protein kinase R-like ER kinase and its role in endoplasmic reticulum stress-decided cell fate. Cell Death Dis . 2015;6:e1822. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Humeau J, Leduc M, Cerrato G, Loos F, Kepp O, Kroemer G. Phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor-2α (eIF2α) in autophagy. Cell Death Dis . 2020;11:433. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-2642-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hillary RF, FitzGerald U. A lifetime of stress: ATF6 in development and homeostasis. J Biomed Sci . 2018;25:48. doi: 10.1186/s12929-018-0453-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chen X, Shen J, Prywes R. The luminal domain of ATF6 senses endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and causes translocation of ATF6 from the ER to the Golgi. J Biol Chem . 2002;277:13045–13052. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110636200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Prakash YS, Thompson MA, Pabelick CM. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in TNF-α modulation of Ca2+ in human airway smooth muscle. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol . 2009;41:603–611. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0151OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sieck GC, White TA, Thompson MA, Pabelick CM, Wylam ME, Prakash YS. Regulation of store-operated Ca2+ entry by CD38 in human airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol . 2008;294:L378–L385. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00394.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Prakash YS, Iyanoye A, Ay B, Mantilla CB, Pabelick CM. Neurotrophin effects on intracellular Ca2+ and force in airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol . 2006;291:L447–L456. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00501.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Prakash YS. Airway smooth muscle in airway reactivity and remodeling: what have we learned? Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol . 2013;305:L912–L933. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00259.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Aravamudan B, Kiel A, Freeman M, Delmotte P, Thompson M, Vassallo R, et al. Cigarette smoke-induced mitochondrial fragmentation and dysfunction in human airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol . 2014;306:L840–L854. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00155.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Aravamudan B, Thompson M, Sieck GC, Vassallo R, Pabelick CM, Prakash YS. Functional effects of cigarette smoke-induced changes in airway smooth muscle mitochondrial morphology. J Cell Physiol . 2017;232:1053–1068. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Xu ZQ, Zhang WJ, Su DF, Zhang GQ, Miao CY. Cellular responses and functions of α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor activation in the brain: a narrative review. Ann Transl Med . 2021;9:509. doi: 10.21037/atm-21-273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Noviello CM, Gharpure A, Mukhtasimova N, Cabuco R, Baxter L, Borek D, et al. Structure and gating mechanism of the α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Cell . 2021;184:2121–2134.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.02.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nakamura Y, Matsumoto H, Wu CH, Fukaya D, Uni R, Hirakawa Y, et al. Alpha 7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors signaling boosts cell-cell interactions in macrophages effecting anti-inflammatory and organ protection. Commun Biol . 2023;6:666. doi: 10.1038/s42003-023-05051-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mulcahy MJ, Blattman SB, Barrantes FJ, Lukas RJ, Hawrot E. Resistance to inhibitors of cholinesterase 3 (Ric-3) expression promotes selective protein associations with the human α7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor interactome. PLoS One . 2015;10:e0134409. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lansdell SJ, Gee VJ, Harkness PC, Doward AI, Baker ER, Gibb AJ, et al. RIC-3 enhances functional expression of multiple nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes in mammalian cells. Mol Pharmacol . 2005;68:1431–1438. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.017459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gu S, Matta JA, Lord B, Harrington AW, Sutton SW, Davini WB, et al. Brain α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor assembly requires NACHO. Neuron . 2016;89:948–955. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Halevi S, McKay J, Palfreyman M, Yassin L, Eshel M, Jorgensen E, et al. The C. elegans ric-3 gene is required for maturation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. EMBO J . 2002;21:1012–1020. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.5.1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wang Y, Yao Y, Tang XQ, Wang ZZ. Mouse RIC-3, an endoplasmic reticulum chaperone, promotes assembly of the α7 acetylcholine receptor through a cytoplasmic coiled-coil domain. J Neurosci . 2009;29:12625–12635. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1776-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nguyen M, Alfonso A, Johnson CD, Rand JB. Caenorhabditis elegans mutants resistant to inhibitors of acetylcholinesterase. Genetics . 1995;140:527–535. doi: 10.1093/genetics/140.2.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Siddesha JM, Nakada EM, Mihavics BR, Hoffman SM, Rattu GK, Chamberlain N, et al. Effect of a chemical chaperone, tauroursodeoxycholic acid, on HDM-induced allergic airway disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol . 2016;310:L1243–L1259. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00396.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.