Abstract

Countries are urged to advance the energy transition in a just, orderly, and equitable manner, yet the appropriate pathway remains unclear. Using a provincial-level, hourly-dispatched power system model of China that incorporates intertemporal decisions on early retirement and carbon capture retrofitting, our study reveals that for coal-rich but gas-poor economies, repositioning coal power from a baseload resource to a flexibility provider can accelerate net-zero transition of the power system in three aspects. First, when achieving the same emissions reduction target, it mitigates stranded assets by decreasing the average lifespan loss of coal power by 7.9-9.6 years and enhancing the long-term competitiveness of retrofitted coal power. Second, it enables the integration of an additional 194-245 gigawatts of variable renewables by 2030 under the same carbon emissions reduction trajectory. Third, it reduces China’s power system transition costs by approximately 176 billion U.S. Dollars, particularly in the face of costly gas power and energy storage technologies. These robust findings underscore the need for appropriate policies to incentivize the flexible dispatch, orderly retirement, and carbon capture retrofitting of coal power, thereby accelerating the decarbonization of China’s power system.

Subject terms: Climate-change mitigation, Energy policy

A study on China finds that repositioning coal power from a baseload resource to a flexibility provider can accelerate the net-zero transition by mitigating stranded assets, enabling greater integration of renewables, and reducing transition costs.

Introduction

The net-zero transition of power system is crucial for achieving the carbon neutrality goals of all countries and addressing the global climate crisis, as the power and heat sector accounted for 43.6% of global energy-related carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in 20211. This transition not only reduces carbon emissions from power generation, but also facilitates emission reductions in other energy end-use sectors by accelerating electrification2. However, many obstacles can hinder rapid net-zero transition, especially in countries that are highly dependent on fossil fuels.

On the one hand, the variability and intermittency of variable renewable energy (VRE) pose integration challenges3 and potential supply shortages during extreme weather events4, highlighting the necessity for flexibility resources5. The rapid cost reduction of VRE technologies is reshaping the energy landscape, rendering them increasingly competitive against fossil fuel-based alternatives6,7. Promoting renewable energy not only benefits carbon emissions reduction but also fosters sustainable development, as evidenced by numerous studies8–13. To address the variability and intermittency of VRE, various flexibility resources, including gas power14, short- and long-term energy storage technologies11,15,16, transmission lines5,17,18 and demand-side responses17,19,20, have been recognized in supporting the integration of VRE. Some studies also emphasized the feasibility of achieving a 100% renewables-powered electricity system by leveraging various energy storage technologies15. However, limited adoption of new technologies can slow down ambitious deployment of VRE.

On the other hand, socio-political feasibility21, transition justice concerns22,23, stranded asset risks24–27 and decision-making preferences28 impede the rapid phase-out of fossil fuels. Numerous studies have analyzed power system transitions using integrated assessment models29, energy system models30, and power system models17,31. These studies have identified cutting coal power generation as an urgent action to reduce carbon emissions. Early retirement28,32–34 and carbon capture and storage (CCS) retrofitting of existing plants35–40 are both widely recognized in bottom-up analysis as essential for achieving climate targets. The stranding of carbon-intensive infrastructure is of increasing concern across the fossil fuel24,41, power25,26, industrial42 and broader energy sectors43,44 under a rapid net-zero transition. They potentially trigger the increasing risks on financial system24,45,46, geopolitics47 and macroeconomy27. The United Arab Emirates Consensus, reached at the 28th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, underscores the importance of transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems in a just, orderly and equitable manner, yet the appropriate pathway remains unclear.

Here we highlight that repositioning coal power from base load to flexibility provider in countries highly dependent on fossil fuels can be a feasible pathway to address above challenges, through taking China as a case study. Coal power exhibits the ability to dispatch flexibly to respond to the fluctuating demand and VRE loads48–50. Promoting unabated coal power in the short term as an alternative flexibility resource in coal-rich, gas-poor countries like China, could be economically effective. CCS-equipped coal power, with additional retrofitting approaches like solvent storage, might be also feasible to provide flexibility, in the long term51–53. However, limited studies have simulated the intertemporal decisions of newly installation, early retirement, CCS retrofitting and flexible dispatch of coal power in one single framework. Such an approach is necessary to optimize the power system transition pathways and quantify the multiple system values of repositioning coal power, including the integration of renewables, reduction of transition costs and mitigation of assets stranding risks.

This paper addresses these gaps by using a provincial-level, hourly-dispatched, and intertemporal-optimized power system model of China. Provincial electricity demand is derived from a provincial-level energy-economic model. The model integrates detailed CCS retrofitting decision for thermal power by accounting for investment, operation, energy penalties, carbon leakage and regional carbon storage potential. Early retirement of coal power is also considered to explore different scenarios of coal power transition. We compared pathways and costs with and without coal power flexibility to examine its effects on power system decarbonization. Additionally, we analyzed sensitivity factors such as coal power technical parameters, technology investment costs and fuel costs to understand the robustness of our research findings. The results suggest that utilizing the flexibility of coal power, compared to cases that fully rely on other flexibility resources, can impact both coal power phase-out strategies and power system transition pathways. This approach can alleviate pressure for early retirement of existing coal power, promote the long-term development of CCS-retrofitted coal power, facilitate the integration of variable renewable energy sources, and reduce the net-zero transition costs of power system. Regional disparities are evident considering the heterogenous distribution of fuel costs, carbon storage availability and renewable energy potential.

Results

Modeling net-zero transition pathways under different scenarios

This study focuses on simulating the variations in net-zero transition pathways and costs through repositioning coal power as a flexibility provider. We developed a provincial-level, hourly-dispatched power system model, to optimize the investment and dispatch of generators, energy storage and transmission lines. The model minimizes the total discounted system costs from 2025 to 2060, subject to a set of constraints, including resource availability, operational conditions, supply-demand balance and reserve requirements. Our approach integrates intertemporal decisions on early retirement, carbon capture retrofitting, and hourly dispatch of coal power, a focus rarely addressed in previous power system models. Detailed descriptions can be found in the “Methods” section and Supplementary Notes 1–3.

This analysis explores two key dimensions in scenario settings (Table 1). First, we define three carbon emission caps for the power sector, i.e., REF, MOD, and STR, to represent reference, moderate, and stringent climate policy scenarios, respectively. The emission trajectory of the REF scenario is determined endogenously through modeling, with no emission cap applied. The MOD scenario aims for carbon neutrality by 2060, while the STR scenario targets this goal by 2050. Under each emission cap, we consider two scenarios reflecting different roles for coal power. In the Base scenario, coal power operates as a baseload with high utilization and limited flexibility, assuming annual utilization exceeds 5000 h and the minimum output level remains above 70%. In contrast, the Flex scenario allows for flexible dispatch of coal power, with no constraints on utilization hours and a minimum output level set at 40%, reflecting technical limitations. These two dimensions result in six distinct scenarios, i.e., REF-Base, REF-Flex, MOD-Base, MOD-Flex, STR-Base, and STR-Flex. The emission trajectories can be found in Supplementary Fig. 7. Sensitivity analyses are performed to assess how variations in technical parameters of coal power, and the costs of fuels, CCS, renewable energy, and energy storage technologies, influence the system value of coal power, thereby evaluating the robustness of our findings.

Table 1.

Model scenario descriptions and settings

| Emission cap | Role of coal power |

|---|---|

| REF (Reference): The emission trajectory is determined endogenously through model simulation, without imposing a carbon emission cap. | Base: coal power operates as a base load with high utilization and limited flexibility. Annual utilization of coal power must exceed 5000 h for any period, and the minimum output level is set at 70% |

| MOD (Moderate): Carbon emissions in the power sector are required to peak in 2030 and reach carbon neutrality in 2060. | Flex: coal power can be dispatched flexibly. There is no constraint on minimum utilization hours of coal power; and the minimum output level is set at 40% |

| STR (Stringent): Carbon emissions in the power sector are required to peak in 2025 and reach carbon neutrality in 2050 |

Impact on early retirement of existing coal power

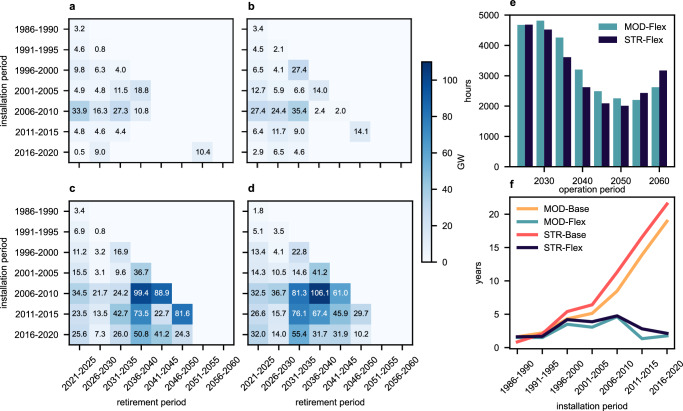

Shifting the role of coal power through flexible dispatch can delay early retirement and reduce asset stranding risks while still achieving the same climate target. Although the levelized cost of coal power exceeds that of VRE in most regions, making coal power increasingly less cost-competitive for baseload generation, flexible dispatch enables coal power to adapt to residual loads amidst fluctuating demands and VRE outputs. This helps remain power system stability and significantly enhancing coal power’s system value, as depicted by the dispatch curves shown in Supplementary Figs. 8, 9. As a result, the extent of early retirement varies substantially between the two scenarios. We compare the early-retired capacity of coal power installed at different stages under various scenarios before achieving carbon neutrality (Fig. 1). Compared to the Base scenario, flexible dispatch of coal power significantly reduces early retirement pressures, owing to substantial reductions in utilization hours and an increase in system value. The utilization hours of coal power in the Flex scenario reach 4523–4816 h in 2030, 2089–2489 h in 2045 and 2622–3173 h in 2060, respectively (Fig. 1e). Under the MOD and STR scenarios, up to 617.8 gigawatts (GW) and 651.2 GW of coal power capacity, respectively, can avoid early retirement. This results in a decrease in the average lifespan loss of coal power installed before 2020 from 10.8–13.1 years to 2.9–3.5 years. The stricter the carbon emission cap, the greater the average lifespan loss.

Fig. 1. Early retirement, utilization and lifespan of coal power.

Panels (a–d) show the early retired capacity heatmaps for the MOD-Flex, STR-Flex, MOD-Base, and STR-Base scenarios, respectively. Each cell in the heatmaps represents the retired capacity during the retirement period (x-axis) of existing coal power plants, which were constructed during the installation period (y-axis). e The average utilization hours of coal power plants during different operation periods for the MOD-Flex and STR Flex scenarios. f The average lifespan loss of existing coal power plants constructed during different installation periods (x-axis) under the four scenarios. MOD and STR represent moderate and stringent emission caps, respectively; Flex and Base represent that coal power can be dispatched flexibly and operates as a base load, respectively. GW gigawatt. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The benefits of avoiding early retirement are primarily concentrated in periods of rapid emissions reduction. Early retirement of coal power before 2025 primarily stems from excess capacity or weak cost competitiveness. However, the scale of early retirement in the Base scenario still exceeds that in the Flex scenario by 58.9–61.7 GW during 2021–2025. From 2030 to 2040, rapid reductions in carbon emissions lead to a significant increase in early retirement under the Base scenario compared to the Flex scenario. The additional early-retired capacity during 2030–2040 and 2040–2050 ranges from 302.8–397.1 GW to 162.6–258.8 GW, respectively, under the two carbon emission caps. Carbon emission caps result in greater lifespan losses for more recently built coal power if coal power is operated as a baseload resource (Fig. 1f). For coal power installed between 2015 and 2020, the average lifespan loss reaches 18.9–21.5 years in the Base scenario, while the loss for capacity built before 2000 does not exceed 6 years. When the coal power is dispatched flexibly, the lifespan loss for capacity installed during any periods is limited to no more than 5 years.

The optimal capacity of coal power varies significantly between the two scenarios across all periods. Under the STR emission trajectory, coal power capacity in the Base scenario is 866.8 GW, 137.8 GW, and 17.7 GW in 2030, 2045, and 2060, respectively—substantially lower than the values in the Flex scenario, which are 1009.6 GW, 802.5 GW and 275.3 GW (Fig. 2a–c). By enhancing the flexible dispatch of coal power and reducing utilization hours, the system value of coal power can be significantly increased. This approach helps mitigate early retirement of existing coal power capacity and reduces transition risks.

Fig. 2. National power system capacity and generation mix under different scenarios and periods.

a Capacity mix in 2030; (b) capacity mix in 2045; (c) capacity mix in 2060; (d) generation mix in 2030; (e) generation mix in 2045; (f) generation mix in 2060. Scenario names at the X-axis are combinations of two dimensions. REF, MOD, and STR represent no, moderate and stringent emission caps, respectively; Flex and Base represent that coal power can be dispatched flexibly and operates as a base load, respectively. PV solar photovoltaic technology, CCS carbon capture and storage, W/ with, W/O without, GW gigawatt, TWh terawatt-hour. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Impact on the net-zero transition of the power system

The structural transformation of the power system, from fossil fuels to renewables, is irreversible, driven by the rapid cost decline of VRE and energy storage technologies (Fig. 2). Without climate policy, solar photovoltaics (PV) and wind power are projected to constitute approximately 74.0–75.2% of power generation capacity and 51.1–53.8% of total generation by 2060. However, a portion of coal power capacity and generation without CCS retrofitting will remain in 2060, comprising 10.8–12.3% of capacity and 23.5–24.1% of generation, emitting about 3.34–3.57 gigatons (Gt) CO2. In a carbon-neutral power system, non-retrofitted coal power is phased out, and VRE is expected to account for 82.8–85.5% of capacity and 66.5–69.9% of generation. The variability and intermittency inherent in solar and wind power necessitate the use of flexible resources, including battery storage, pumped hydro and thermal power plants. By 2060, the discharge from battery and pumped hydro is projected to reach 2220.7–2625.2 terawatt-hours (TWh), equivalent to 18.2–20.1% of VRE generation, offering significant flexibility for VRE integration.

Flexible dispatch of coal power accelerates the net-zero transition of the power system in four ways. First, it increases the system value of coal power, thereby boosting the cost competitiveness of CCS retrofitting. By 2045, the capacity of CCS-retrofitted coal power in the Flex scenario is projected to reach 77.4–203.1 GW, exceeding the Base scenario by 36.6–168.4 GW. By 2060, the capacity of CCS-retrofitted coal power in the Flex scenario is expected to reach 275.3–318.1 GW, surpassing the Base scenario by 257.5–294.3 GW. Second, flexible dispatch of coal power prevents excessive expansion of gas power. In the Base scenario, as coal power capacity rapidly declines during the mid-term transition, gas power capacity must expand to meet peak load demands. In 2030, 2045, and 2060, gas power capacity in the Base scenario exceeds that in the Flex scenario by 110.3–148.3 GW, 493.4–528.5 GW and 121.8–153.0 GW, respectively. Notably, gas power is primarily used to meet peak loads, with utilization hours in 2060 ranging from only 1068 to 2202 h, making CCS retrofitting of gas power economically infeasible. The residual carbon emissions from coal and gas power in 2060, estimated at 0.27–0.31 Gt, are offset by negative carbon emissions generated by 69.4–111.2 GW of bioelectricity with CCS (BECCS). Third, the rapid phase-out of coal power capacity of the Base scenario increases the demand for battery storage as a flexible resource, with the required capacity rising by 750.8–913.8 gigawatt-hours (GWh) (Supplementary Fig. 10). Finally, the flexibility provided by coal power accelerates the short-term deployment of VRE. Due to the higher emission factor of coal power compared to gas or biomass power, thermal power generation in the Flex scenario is 173.3–257.4 TWh lower than in the Base scenario in 2030, under the same carbon emission constraints. This reduction in thermal generation promotes VRE deployment, with capacity increasing by 194.0–244.8 GW.

Regional transition pathways vary significantly due to differences in renewable energy resource endowment, electricity demand, and cross-regional transmission capacity (Fig. 3). The regional potential and economic feasibility of alternative energy sources can substantially reduce reliance on coal-fired power. In the STR-Flex scenario, VRE is projected to account for 91.7%, 69.7%, and 86.5% of electricity generation in Northeast, Northwest, and North China by 2060, respectively. Hydropower will continue to dominate in Southwest China, comprising 66.7% of the region’s electricity generation by 2060. In South and East China, nuclear power is expected to complement the limited VRE resources, contributing 20.6% and 46.5% in 2060, respectively. Resource constraints in Central and East China will necessitate significant cross-regional power transmission from North and Northwest China to meet local demand. Additionally, regions with lower coal prices and higher carbon storage potential are better positioned to retrofit coal power capacity with CCS, which will play a crucial role in North and Northwest China.

Fig. 3. Regional power generation mix and demand in stringent emission cap scenarios.

a Northwest China, (b) North China, (c) Northeast China, (d) Southwest China, (e) Central China, (f) East China, (g) South China. The provinces included in each region are detailed in Supplementary Table 1. The x-axis labels consist of two dimensions: Flex and Base represent that coal power can be dispatched flexibly and operates as a base load, respectively; 2030, 2045 and 2060 are the simulated periods. PV solar photovoltaic technology, CCS carbon capture and storage, W/ with, W/O without, TWh terawatt-hour. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The regional impacts of coal power’s flexibility resources vary significantly. Taking Central China as an example, high coal price makes the provision of flexible resources from coal power expensive. Additionally, relatively low capacity factor and limited land availability for wind and solar resources constrain VRE’s development potential. By 2030, 2045, and 2060, VRE generation in Central China is projected to be only 173.7, 527.9, and 618.6 TWh, respectively, accounting for less than 6% of nationwide VRE generation in the STR-Flex scenario. Consequently, the demand for local flexible resources to support VRE integration remains limited. These two aspects undermine the competitiveness of coal power in the region. Under the STR-Flex scenario, coal power generation in Central China is expected to decline to 57.9 TWh by 2045, with a complete phase-out by 2060. Similar phase-out trajectories are projected for coal power in South, Southwest, East, and Northeast China. By 2060, the presence of CCS-retrofitted coal power in these regions will be minimal, with flexibility primarily provided by energy storage technologies and transmission lines. In contrast, coal power phase-out paths in Northwest and North China diverge significantly. Due to lower coal price and higher carbon storage potential, CCS-retrofitted coal power remains cost-competitive in the mid-to-long term. Flexible dispatch of coal power enables an additional 532.5 TWh and 232.3 TWh of CCS-retrofitted coal power generation in North and Northwest China by 2060, respectively.

Impact on transition costs

The net-zero transition of the power system incurs substantial costs. Without policy interventions, a cost-minimizing power system will see continuous increases in renewables, significantly reducing the carbon intensity. However, reducing remaining carbon emissions necessitates more investments in renewables, energy storage, transmission lines and CCS technologies, along with reduced coal power capacity and utilization hours to meet carbon emission reduction targets. We quantified the annual transition costs for different policy scenarios compared to the REF scenario (Fig. 4a). The results reveal that as carbon emission constraints tighten, the proportion of mitigation costs relative to total system costs rises, peaking at 8.3–14.4% by 2050. The costs then decrease by 2060 as the net-zero target is substantially achieved. Achieving net-zero emissions significantly reduces fuel costs and variable operation and maintenance (O&M) costs compared to the REF scenario (Fig. 4b). The continued decline in coal power generation significantly cut coal consumption, leading to a decrease in fuel costs by 252.7–526.3 billion U.S. Dollars (USD). Capital investments in generation and energy storage technologies increase substantially, with investment costs rising by 612.8–843.8 billion USD. Additionally, CCS retrofits increase CCS-related fixed and variable costs by 55.1–103.8 billion USD, and the start-up costs of thermal plants rise due to stringent emission constraints, reaching 7.9–43.2 billion USD. Considering both costs and benefits, the net discounted transition cost amounts to 171.3–447.0 billion USD, representing 2.17–5.65% of total system costs.

Fig. 4. Trends and components of power system transition costs.

a The percentage of power system transition costs relative to the total system costs in the REF-Flex scenario; (b) the discounted power system transition cost components for the scenarios compared to REF-Flex; (c) the difference in cost components between MOD-Base and MOD-Flex by periods; (d) the difference in cost components between STR-Base and STR-Flex by periods. REF, MOD, and STR represent no, moderate and stringent emission caps, respectively; Flex and Base represent that coal power can be dispatched flexibly and operates as a base load, respectively. ΔMOD represents the difference in cost components between MOD-Base and MOD-Flex, and ΔSTR represents the difference in cost components between STR-Base and STR-Flex. CCS carbon capture and storage, T&D transmission and distribution, O&M operation and maintenance. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The flexible dispatch of coal power significantly lowers the transition costs of the power system. The annual savings in transition costs, relative to total system costs, are 2.53–2.56% in 2030, 2.22–2.42% in 2045, and 0.27–0.40% in 2060, indicating significant benefits across all periods. The total discounted transition cost savings reach 175.2–176.6 billion USD (Fig. 4b), with fuel cost savings being the largest component, totaling 261.0–273.5 billion USD. This is because, without coal power flexibility, additional gas power required for peaking would rely on costly natural gas, significantly increasing fuel costs. Moreover, flexible coal dispatch reduces start-up costs by 11.3–11.7 billion USD, as gas power used for peaking requires frequent start-up cycles, and some inflexible coal plants must shut down during low demand timepoints. The impact of flexible dispatch of coal power on the transition costs varies across different periods (Fig. 4c, d). Fuel costs are significantly reduced during all periods except for 2060. In terms of power generation and storage technology investments, repositioning coal power in the short- to medium-term transition periods significantly supports the growth of renewable energy, leading to an increase in capacity investment. In contrast, investment costs are reduced due to the avoidance of excessive investment in technologies such as gas power and battery storage in the later stages. Due to the increased competitiveness of coal power CCS retrofitting, both the fixed and variable costs of CCS rise under the Flex scenario. Overall, repositioning coal power can substantially reduce the transition costs of the power system.

Sensitivity analysis

We identified the sensitivities of coal power technical parameters, wind and solar resource potential, electricity demand, and the costs of renewable energy, energy storage, CCS, and fuels on transition pathways and costs under the MOD emissions trajectory (Fig. 5). The experiments are described in Supplementary Table 9. The results demonstrate that coal power capacity without CCS retrofitting is rapidly phased out, while the capacity of coal power in all Flex scenarios remains significantly higher than in Base scenarios due to its high system value, with differences ranging from 370.1 GW to 537.1 GW by 2045 under varying parameter assumptions. Over the long term, the capacity of CCS-retrofitted coal power in Flex scenarios is markedly larger than in Base scenarios. Under low coal prices, the capacity of CCS-retrofitted coal power reaches 594.1 GW by 2060 in the Flex scenario, underscoring its higher system value and competitiveness. Conversely, high coal prices, low natural gas prices, and high CCS costs significantly undermine the cost-effectiveness of retrofitting coal-fired power plants with CCS, resulting in installed capacities of only 130.1 GW, 103.8 GW, and 19.7 GW by 2060, respectively. Among the factors analyzed, CCS retrofit costs exhibit the greatest sensitivity to the deployment of CCS-retrofitted coal power, highlighting the critical need for accelerated CCS cost reductions to enhance its viability. Except in scenarios with substantially high CCS costs, gas power and battery storage capacities in Flex scenarios are consistently lower than those in Base scenarios, with a gas power capacity reduction of 364.0–512.2 GW by 2045 and a corresponding decrease in storage capacity of 85.3–939.1 GWh. In contrast, under high CCS costs, battery storage capacity increases by 189.7 GWh by 2060 to compensate for the limited deployment of CCS-retrofitted coal power and to provide operational flexibility. In the near term, the capacity of variable renewables in Flex scenarios surpasses that in Base scenarios, with wind and solar generation capacity increasing by 68.6–271.0 GW by 2030. The substantial avoidance of additional, high-cost gas power capacity reduces fuel costs by 200.4–293.7 billion USD and overall system costs by 126.5–188.4 billion USD.

Fig. 5. Uncertainties of power system transition pathways and costs.

a The capacity of non-retrofitted coal power; (b) the capacity of carbon capture retrofitted coal power; (c) the capacity of gas power; (d) the capacity of variable renewables; (e) the capacity of battery storage; (f) the difference in cost components between Base and Flex for sensitivity experiments. Flex and Base represent that coal power can be dispatched flexibly and operates as a base load, respectively. The emissions trajectory is set as the moderate emission cap scenario. Box plots show the median (center line), interquartile range (box), and whiskers extend to the minimum and maximum values, excluding outliers. Outliers are defined as data points outside 1.5× the interquartile range from the first and third quartiles. CCS carbon capture and storage, T&D transmission and distribution, O&M operation and maintenance, GW gigawatt, GWh gigawatt-hour. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Furthermore, we evaluated the sensitivity of our conclusions to the operational flexibility of CCS-retrofitted coal power. Previous studies have indicated that retrofitting coal-fired power plants with CCS could significantly constrain their operational flexibility. However, additional technological retrofits—such as venting and solvent storage—can mitigate these limitations and enable flexibility51–53. To explore this, we developed two sensitivity experiments based on the MOD-Flex scenario. In the Flex-BaseCCS scenario, retrofitted coal plants operate as baseload units with limited flexibility, characterized by utilization hours exceeding 5000 annually. The Flex-FlexCCS scenario incorporates operational flexibility through solvent storage retrofits, albeit at a 20% increase in CCS retrofit investment costs51. The results reveal that both limited operational flexibility and additional investment costs for flexibility enhancements significantly reduce the long-term competitiveness of CCS-retrofitted coal plants. By 2060, the installed capacity of CCS retrofitted coal power in the Flex-BaseCCS and Flex-FlexCCS scenarios decreases to 162.8 GW and 264.2 GW, respectively, compared to 318.1 GW in the MOD-Flex scenario (Supplementary Fig. 11).

In conclusion, our comprehensive sensitivity analysis underscores the pivotal role of repositioning coal power in driving China’s low-carbon energy transition and reducing system transition costs. Nevertheless, the deployment scale of CCS-retrofitted coal power is highly sensitive to CCS costs, emphasizing the importance of advancing CCS technologies to improve their cost-effectiveness and scalability.

Discussion

The coal power phase-out strategies must align with the net-zero transition of the whole power system. This study develops a provincial, hourly-dispatched power system model for China that intertemporally optimizes the investment and dispatch decisions. The model highlight decisions related to the installation of new coal power, early retirements and CCS retrofitting of existing capacity. It also addresses the impact of the flexible dispatch of coal power on the net-zero transition of power system, compared to solely relying on other dispatchable sources.

This study indicates that reducing coal power generation is essential for meeting ambitious net-zero emissions targets. This can be achieved either by rapidly phasing out the coal power used as the baseload or by decreasing the utilization hours through flexible dispatch. These two approaches, however, have vastly different implications for the power system’s transition pathway and costs. Flexible dispatch reduces the utilization hours of coal power plants to below 3000 h, significantly alleviating the pressure for early retirement of existing coal power plants in the short to medium term, cutting the average lifespan loss from 10.8–13.1 years to 2.9–3.5 years. In the long term, it enhances the cost competitiveness of CCS-retrofitted coal power, adding an estimated 257.5–294.3 GW in 2060. This approach also avoids the need for substantial new investments in costly gas-fired power plants, preventing the addition of 493.4–528.5 GW of new gas power capacity around 2045, which helps stabilize the power system and promotes the development of renewable energy sources. While flexible dispatching entails higher fixed and variable costs for coal power, it substantially reduces the overall system transition cost by about 176 billion USD. This underscores the critical role of an orderly coal power transition in achieving net-zero target.

However, regional disparities in the pace of coal power phase-out are evident. In regions like Central China, East China, and the South, where coal price is high and carbon sequestration potential is limited, coal power capacity will rapidly decline and nearly exit by 2045, even with flexible dispatch. In contrast, CCS retrofits for coal power remain competitive in the long term in North and Northwest China, with a certain proportion of coal power capacity still present by 2060 to lower the national power sector’s net-zero transition costs. This study, however, does not fully address the fairness and feasibility of regional coal power phase-out. The slow progress of China’s electricity market reform hinders the reduction of coal power utilization hours purely based on economic dispatch principles. Local governments’ preferences for local generation enterprises may obstruct the phase-out of uncompetitive coal power in certain regions and hinder the cost-optimal integration of VRE54,55. Therefore, corresponding incentive policies are needed to effectively manage these challenges. Additionally, regional coordination of the low-carbon transition in coal power and other high coal-consuming industries, such as coal-to-chemicals, is crucial for mitigating emissions, preventing carbon leakage, and achieving economy-wide net-zero emissions target.

Confronting the issue of stranded assets of coal-fired power plants is becoming unavoidable due to the rapid penetration of VRE and the role of coal-fired power as a flexibility provider. This shift leads to a significant rise of fixed costs over time. Without supporting mechanisms to offset the increasing capacity price, coal power enterprises may lack the financial motivation to undertake flexible transformations, CCS retrofits and provide auxiliary services to VRE. Market mechanisms aimed at reducing stranded assets must ensure incentive compatibility to maximize the value of coal-fired power in supplying flexible resources and meeting peak demand while minimizing unnecessary generation that hinders the penetration of VRE. Expanding the auxiliary service market or electricity spot market can provide coal-fired power with more economic benefits in supplying flexible resources. A capacity price mechanism can be designed to correlate the recovery of fixed costs with the decline of capacity factor and the flexibility transformation. Additionally, a carbon market with a emission cap can create incentives to reduce excessive coal power capacity and generation in the short term and provide long-term motivations for CCS retrofitting.

The sensitivity analysis demonstrates the robustness of this study, highlighting the crucial role of flexible dispatch of coal power in facilitating the power system’s net-zero transition. However, certain limitations exist. First, the model only focuses on typical days, rather than simulates the power dispatch continuously for the whole year, which may introduce bias when assessing the relative competitiveness of coal power and VRE. Second, the installation of carbon capture facilities in coal-fired power plants and further implementation of flexibility retrofitting face significant technical and cost challenges. The study does not address the cost allocation and pricing mechanisms under different technological pathways towards net-zero transition, and identify the differences in CCS and flexibility retrofitting for various types of coal-fired units, such as combined heat and power plants. Future work could focus on more detailed modeling and analysis of coal-fired power units, considering specific technical aspects. Third, this study does not consider long-duration energy storage technologies such as hydrogen storage and thermal energy storage. These technologies could significantly reduce dependence on coal power in the long term. Incorporating more diversified energy storage technologies into power system models would provide deeper insights into the long-term transition dynamics.

Methods

Modeling framework

The modeling framework used in this study, named China Hybrid Energy Economic Research (CHEER), focuses on analyzing the provincial-level transition dynamics of China. CHEER integrates a power system model (CHEER/Power) with a computable general equilibrium (CGE) model through soft-linking mechanism (Supplementary Note 1). CHEER/Power model optimizes the capacity and hourly dispatch of various energy generators, energy storage technologies, CCS and transmission lines to minimize system costs while adhering to a set of constraints, including resource availability, hourly supply-demand equilibrium, unit commitment and economic dispatch conditions and carbon emission caps. The model covers nine power generation technologies, including coal, gas, nuclear, hydro, utility-scale and distributed PV, onshore and offshore wind, and biomass, and two energy storage technologies, i.e., battery and pumped hydro. CHEER/Power model simulates the power system transition pathways intertemporally, with each period representing a span of 5 years from 2025 to 2060, aligned with the electricity demand projections generated by CGE model. The CHEER/Power model is coded in the Julia programming language and incorporates historical capacity data, renewable energy resource potential estimations and recent technology and fuel cost data (Supplementary Notes 2–3). This integration ensures accurate simulation of the power system’s transition pathways.

Early retirement and carbon capture retrofits decision

CHEER/Power simulates the early retirement of coal power and CCS retrofits decision of thermal power (i.e., coal, gas and biomass-fired) through two non-negative continuous variables, i.e., and . The former represents the cumulative CCS-retrofitted capacity, and the latter represents the cumulative early-retired capacity in period of thermal power generation project g built in year . The differences in and between current and previous period are the newly CCS retrofitted and early-retired capacity, i.e., and , respectively, which are no less than 0. must be within the life expectancy of given power generator, i.e., , here is the life expectancy. The upper constraint of cumulative CCS-retrofitted and early-retired capacity is the installed capacity of the given generator built in year , i.e., . We then separate the in-service thermal power capacity of each period p into retrofitted capacity and non-retrofitted capacity , see Eqs. (1), (2). The economic motivation for early retirement of coal power is to avoid annually fixed O&M costs.

| 1 |

| 2 |

The dispatch of retrofitted and non-retrofitted capacity must adhere to the dispatch rules for thermal power. However, the CCS-retrofitted capacity faces energy penalty, resulting in lower total on-grid power compared to non-retrofitted one, see Eq. (3).

| 3 |

in which is the efficiency loss, and are the dispatch capacities of CCS retrofitted and non-retrofitted generator g in timepoint t, respectively. is the total on-grid power in timepoint t.

The cost components of CCS are divided into capital cost, variable O&M cost, carbon transport and carbon storage cost. The annualized capital cost depends on the overnight cost in the retrofitted year, the interest rate and the remaining lifetimes (Eq. (4)). The provincial-level carbon transport cost is assumed to be proportional to the averaged distance between existing power units and carbon sequestration areas. We calculate the CCS variable cost as the sum of O&M cost, carbon transport cost and storage cost (Eq. (5)).

| 4 |

| 5 |

in which is the annualized capital expenditure of generator g built in year pb and retrofitted in year pt. is the total variable O&M costs of CCS in timepoint t. is the fixed costs of CCS in year pt, including both the annualized capital investment cost and fixed O&M cost. is the variable O&M cost using fuel f, is the emission factor of fuel f, is the carbon capture rate, and are the carbon transport and storage cost, respectively.

Scenario design and sensitivity analysis

We firstly design 6 scenarios regarding three carbon emission trajectories and two roles of coal power. The three carbon emission trajectories, i.e., REF, MOD and STR, represent reference, moderate and stringent climate policy scenarios on China’s power system decarbonization, respectively. The REF trajectory is determined endogenously through simulating without an emission cap. The MOD scenario achieves carbon neutrality by 2060, whereas the STR scenario reaches this goal by 2050. Under each trajectory, we consider two scenarios related to the role of coal power. In the Base scenario, coal power operates as a baseload with high utilization rates and limited flexibility. In this scenario, annual utilization hours must exceed 5000 h, and the minimum output level must be higher than 70%. The Flex scenario allows flexible dispatch of coal power without constraints on utilization hours, with a minimum output level set at 40% due to technical requirements. The transition cost is calculated as the difference in total system costs between the four policy scenarios and REF-Flex scenario.

We conducted a sensitivity analysis on several key parameters affecting transition pathways and costs, including: (1) two minimum output levels for coal power, i.e., 30% and 50%; (2) two scenarios for land use constraints on solar and wind, which primarily impact the capacity potential of onshore wind and utility-scale PV in Central, South and East China; (3) four technology cost assumptions, including low renewables costs, low battery costs, low renewables and battery costs, and high CCS costs, which affects the relative competitiveness of key technologies; (4) three fuel cost assumptions, including low coal prices, low gas prices and high coal prices; (5) two electricity demand levels; and (6) two flexibility assumptions for CCS-retrofitted coal power. Detailed descriptions of the scenarios can be found in Supplementary Table 7, and the results are summarized in Source Data file. We analyzed the impacts of these factors on the optimal coal and gas power capacity, the scale of CCS-retrofitted capacity, the development of renewables and storage, and transition costs.

Supplementary information

Source data

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 72348001 and No. T2261129475).

Author contributions

K.A., X.Z., and C.W. conceived the idea of this study and designed the research. K.A. developed the model, conducted the optimization experiments and analyzed the results. J.S. and C.B. provides necessary data for the model. K.A. and X.Z. wrote the manuscript. J.S., C.X. and W.C., revised the manuscript. K.A., X.Z., J.S., C.X., C.W., W.C., and C.B. reviewed the approved the final manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Chris Greig, Peter Balash and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

The model inputs and scenario results generated in this study are available on Zenodo at 10.5281/zenodo.1483676056. Output curves for variable renewable energy are available from https://renewables.ninja. Source data for the figures in the main text are provided with this paper. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code for modeling, analyzing, and creating figures is open-source and available on GitHub (https://github.com/KennethAnn/CHEER-Power) and stored at 10.5281/zenodo.1483676056.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-025-57559-2.

References

- 1.IEA. Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Energy. (2023).

- 2.Bistline, J. E. T. et al. Economy-wide evaluation of CO2 and air quality impacts of electrification in the United States. Nat. Commun.13, 6693 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heptonstall, P. J. & Gross, R. J. K. A systematic review of the costs and impacts of integrating variable renewables into power grids. Nat. Energy6, 72–83 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fan, J.-L. et al. A net-zero emissions strategy for China’s power sector using carbon-capture utilization and storage. Nat. Commun.14, 5972 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li, M., Shan, R., Abdulla, A., Virguez, E. & Gao, S. The role of dispatchability in China’s power system decarbonization. Energy Environ. Sci.17, 2193–2205 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiser, R. et al. Expert elicitation survey predicts 37% to 49% declines in wind energy costs by 2050. Nat. Energy6, 555–565 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmidt, O., Hawkes, A., Gambhir, A. & Staffell, I. The future cost of electrical energy storage based on experience rates. Nat. Energy2, 17110 (2017).

- 8.He, G. et al. Rapid cost decrease of renewables and storage accelerates the decarbonization of China’s power system. Nat. Commun.11, 2486 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.An, K., Wang, C. & Cai, W. Low-carbon technology diffusion and economic growth of China: An evolutionary general equilibrium framework. Struct. Change Economic Dyn.65, 253–263 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang, Y. et al. Accelerating the energy transition towards photovoltaic and wind in China. Nature619, 761–767 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gulagi, A. et al. The role of renewables for rapid transitioning of the power sector across states in India. Nat. Commun.13, 5499 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luderer, G. et al. Environmental co-benefits and adverse side-effects of alternative power sector decarbonization strategies. Nat. Commun.10, 5229 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peng, K. et al. The global power sector’s low-carbon transition may enhance sustainable development goal achievement. Nat. Commun.14, 3144 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bistline, J. E. T. & Young, D. T. The role of natural gas in reaching net-zero emissions in the electric sector. Nat. Commun.13, 4743 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bogdanov, D. et al. Radical transformation pathway towards sustainable electricity via evolutionary steps. Nat. Commun.10, 1077 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peng, L., Mauzerall, D. L., Zhong, Y. D. & He, G. Heterogeneous effects of battery storage deployment strategies on decarbonization of provincial power systems in China. Nat. Commun.14, 4858 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen, X. et al. Pathway toward carbon-neutral electrical systems in China by mid-century with negative CO2 abatement costs informed by high-resolution modeling. Joule5, 2715–2741 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhuo, Z. et al. Cost increase in the electricity supply to achieve carbon neutrality in China. Nat. Commun.13, 3172 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fu, Y., Bai, H., Cai, Y., Yang, W. & Li, Y. Optimal configuration method of demand-side flexible resources for enhancing renewable energy integration. Sci. Rep.14, 7658 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jabir, H. J., Teh, J., Ishak, D. & Abunima, H. Impacts of demand-side management on electrical power systems: A review. Energies11, 1050 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muttitt, G., Price, J., Pye, S. & Welsby, D. Socio-political feasibility of coal power phase-out and its role in mitigation pathways. Nat. Clim. Chang.13, 140–147 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nacke, L., Vinichenko, V., Cherp, A., Jakhmola, A. & Jewell, J. Compensating affected parties necessary for rapid coal phase-out but expensive if extended to major emitters. Nat. Commun.15, 3742 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mirzania, P., Gordon, J. A., Balta-Ozkan, N., Sayan, R. C. & Marais, L. Barriers to powering past coal: Implications for a just energy transition in South Africa. Energy Res. Soc. Sci.101, 103122 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Semieniuk, G. et al. Stranded fossil-fuel assets translate to major losses for investors in advanced economies. Nat. Clim. Chang.12, 532–538 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu, Y., Cohen, F., Smith, S. M. & Pfeiffer, A. Plant conversions and abatement technologies cannot prevent stranding of power plant assets in 2 °C scenarios. Nat. Commun.13, 806 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oshiro, K. & Fujimori, S. Limited impact of hydrogen co-firing on prolonging fossil-based power generation under low emissions scenarios. Nat. Commun.15, 1778 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mercure, J.-F. et al. Macroeconomic impact of stranded fossil fuel assets. Nat. Clim. Change8, 588–593 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yan, X. et al. Cost-effectiveness uncertainty may bias the decision of coal power transitions in China. Nat. Commun.15, 2272 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cui, R. Y. et al. A plant-by-plant strategy for high-ambition coal power phaseout in China. Nat. Commun.12, 1468 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang, S. & Chen, W. Assessing the energy transition in China towards carbon neutrality with a probabilistic framework. Nat. Commun.13, 87 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bistline, J. E. T. & Blanford, G. J. Impact of carbon dioxide removal technologies on deep decarbonization of the electric power sector. Nat. Commun.12, 3732 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li, J. et al. Incorporating health cobenefits in decision-making for the decommissioning of coal-fired power plants in China. Environ. Sci. Technol.54, 13935–13943 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tong, D. et al. Health co-benefits of climate change mitigation depend on strategic power plant retirements and pollution controls. Nat. Clim. Chang.11, 1077–1083 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Henneman, L. et al. Mortality risk from United States coal electricity generation. Science382, 941–946 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang, R. et al. Alternative pathway to phase down coal power and achieve negative emission in China. Environ. Sci. Technol.56, 16082–16093 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fan, J.-L., Xu, M., Li, F., Yang, L. & Zhang, X. Carbon capture and storage (CCS) retrofit potential of coal-fired power plants in China: The technology lock-in and cost optimization perspective. Appl. Energy229, 326–334 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang, P.-T. et al. Carbon capture and storage in China’s power sector: Optimal planning under the 2 °C constraint. Appl. Energy263, 114694 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wei, N. et al. Decarbonizing the coal-fired power sector in China via carbon capture, geological utilization, and storage technology. Environ. Sci. Technol.55, 13164–13173 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fan, J.-L., Xu, M., Yang, L. & Zhang, X. Benefit evaluation of investment in CCS retrofitting of coal-fired power plants and PV power plants in China based on real options. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev.115, 109350 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fan, J.-L. et al. Co-firing plants with retrofitted carbon capture and storage for power-sector emissions mitigation. Nat. Clim. Chang.13, 807–815 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kemfert, C., Präger, F., Braunger, I., Hoffart, F. M. & Brauers, H. The expansion of natural gas infrastructure puts energy transitions at risk. Nat. Energy7, 582–587 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu, R. et al. Plant-by-plant decarbonization strategies for the global steel industry. Nat. Clim. Chang.13, 1067–1074 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tong, D. et al. Committed emissions from existing energy infrastructure jeopardize 1.5 °C climate target. Nature572, 373–377 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith, C. J. et al. Current fossil fuel infrastructure does not yet commit us to 1.5 °C warming. Nat. Commun.10, 101 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Battiston, S., Mandel, A., Monasterolo, I., Schütze, F. & Visentin, G. A climate stress-test of the financial system. Nat. Clim. Change7, 283–288 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dietz, S., Bowen, A., Dixon, C. & Gradwell, P. Climate value at risk’ of global financial assets. Nat. Clim. Change6, 676–679 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jaffe, A. M. The role of the US in the geopolitics of climate policy and stranded oil reserves. Nat. Energy1, 1–4 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fiebrandt, M., Röder, J. & Wagner, H.-J. Minimum loads of coal-fired power plants and the potential suitability for energy storage using the example of Germany. Int. J. Energy Res.46, 4975–4993 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gonzalez-Salazar, M. A., Kirsten, T. & Prchlik, L. Review of the operational flexibility and emissions of gas- and coal-fired power plants in a future with growing renewables. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev.82, 1497–1513 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Energiewende, A. Flexibility in Thermal Power Plants – With a Focus on Existing Coal-Fired Power Plants. (2017).

- 51.van der Wijk, P. C. et al. Benefits of coal-fired power generation with flexible CCS in a future northwest European power system with large scale wind power. Int. J. Greenh. Gas. Control28, 216–233 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu, J. et al. Evaluation and improvements on the flexibility and economic performance of a thermal power plant while applying carbon capture, utilization & storage. Energy Convers. Manag.290, 117219 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chalmers, H., Gibbins, J. & Leach, M. Valuing power plant flexibility with CCS: the case of post-combustion capture retrofits. Mitig. Adapt Strateg Glob. Change17, 621–649 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yu, Y. et al. Decarbonization efforts hindered by China’s slow progress on electricity market reforms. Nat. Sustain6, 1006–1015 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xiang, C., Zheng, X., Song, F., Lin, J. & Jiang, Z. Assessing the roles of efficient market versus regulatory capture in China’s power market reform. Nat. Energy8, 747–757 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 56.An, K. et al. Code and data for article titled “repositioning coal power to accelerate net-zero transition of China’s power system”. Zenodo. 10.5281/zenodo.14836760 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The model inputs and scenario results generated in this study are available on Zenodo at 10.5281/zenodo.1483676056. Output curves for variable renewable energy are available from https://renewables.ninja. Source data for the figures in the main text are provided with this paper. Source data are provided with this paper.

The code for modeling, analyzing, and creating figures is open-source and available on GitHub (https://github.com/KennethAnn/CHEER-Power) and stored at 10.5281/zenodo.1483676056.