Abstract

Lower respiratory tract microbiome constitutes a unique immune microenvironment for advanced non-small cell lung cancer as one of dominant localized microbial components. However, there exists little knowledge on the associations between this regional microbiome and clinical responses to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy from clinical perspectives. Here, we equivalently collected bronchoalveolar lavage fluids from 56 advanced NSCLC participants treated with none (untreated, n = 28) or anti-PD-1 immunotherapy (treated, n = 28), which was further divided into responder (n = 17) and non-responder (n = 11) subgroups according to clinical responses, aiming to compare their microbial discrepancy by performing metagenomic sequencing and targeted metabolic alterations by tryptophan sequencing. Correspondingly, microbial diversities transformed significantly after receiving immunotherapeutic agents, where Gammaproteobacteria and Campylobacter enriched, but Escherichia, Streptococcus, Chlamydia, and Staphylococcus reduced at the genus level, differences of which failed to be achieved among subgroups with various clinical responses (responder or non-responder; LDA > 2, P < 0.05*). And the relative abundance of Staphylococcus and Streptomyces was escalated in response subgroup to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy by microbial compositional analysis (as relative abundance ≥ 3%, P < 0.05*), no significance of which was achieved among treated and untreated groups. In addition, relative abundances of bacterial tryptophan metabolites and its derivatives were also higher in the responder subgroup, distinctively being associated with divergent genera (VIP > 1, P < 0.05*). Our study revealed predictive performance of lower respiratory tract microbiome to antitumoral immunotherapy and further suggested that anti-PD-1 immunotherapy may alter lower respiratory tract microbiome composition and interact with its tryptophan metabolites to regulate therapeutic efficacy in advanced NSCLC, performing as potential biomarkers to prognosis and interventional strategies.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00262-025-03996-3.

Keywords: Advanced non-small cell lung cancer, Lower respiratory tract microbiome, Tryptophan metabolites, Anti-PD-1 immunotherapy, Clinical responses

Introduction

The advent of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) over the past decade has achieved significant improvements in survival for patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), which accounts for the great majority of morbidity and mortality in the worldwide [1]. Unfortunately, only 20% of NSCLC could benefit from ICIs, especially targeting programmed death-ligand 1 and its ligand (PD-1/PD-L1) blockade therapy, with the presence of primary or acquired drug resistance to immunotherapy [2–5]. Although the relative expression of PD-1/PD-L1 has been taken as primary efficacy predictor to ICIs in clinic, tumoral heterogeneity and individual differences still make it vulnerable to reach unsatisfied therapeutic outcomes and even excessive expectation among identified potential beneficiaries by detecting PD-1/PD-L1 alone [6]. Therefore, exploring innovative biomarkers to effectively identify potentially profiting cohort to ICI therapy is still an urgency in advanced NSCLC.

Microbiomes have been extensively validated to take effects in the efficacies of chemotherapy, radiotherapy and to reduce treatment-related adverse events in advanced NSCLC [7–9]. Taking gut microbiome as an example, distinct microbial characteristics in gut dynamically establish individualized microecological environments from the birth. And gut microbiome usually performs as personnel “Identity Cards” to maintain health by organ-oriented axial transportation, disturbance of which may drive morbid, and even lung cancer-included tumoral conditions. Growing evidences have also proved that intestinal microbiome determines the sensitivity to multiple antitumoral therapeutic strategies regarded as microbial predictors in NSCLC [10–12]. However, lower respiratory tract microbiome is seemingly negligent on carcinogenesis in pulmonary disorders, although amounts of studies have demonstrated its dominant performance on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cystic fibrosis, asthma, and other respiratory diseases. Due to the spatial/temporal coexistence with malignant cells in lung, lower respiratory tract microbiome is correlated more closely with NSCLC by direct interaction than gut microbiome by axial transportation via blood [13–15]. Indeed, outburst of cultural techniques and multi-omics sequencings enables precise identification of lower respiratory tract microbiome rather than present invasive examinations [16], further presenting a potential preference for achieving dynamic monitoring and agent efficacy prediction during therapeutic steps to NSCLC.

Predictive performance of lower respiratory tract microbiome in antitumoral immunotherapy has been verified by several studies up to now. Recent reports illustrated that pulmonary immune signatures appeared to be more closely related to lower respiratory tract flora than to gut microbiome in the same ones, albeit in a restricted biomass compared to that in gut [17]. From clinical perspectives, responders to immunotherapy feature a more diverse lower respiratory tract microbiota than that in non-responders, and certain bacterial products could be crucial for the response group [18], but other studies have still reached no difference between them both [19]. Thus, enough attentions need to be further paid on the ICI-associated lower respiratory tract microbiome alterations, which may provide a convenient, implementable approach for illustrating the distinctive role of lower respiratory tract microbiome in clinical responses throughout immune checkpoint blockade therapy.

In addition, besides the microbe-derived direct interaction to host cells, microorganisms are liable to produce various metabolites as signaling mediums to crosstalk with the host [20]. Among them, tryptophan metabolism centers as a common therapeutic target in multiple cancer types, but reaches contradictory evidences as to whether tryptophan metabolism affects responses to immunotherapy. Several studies revealed that tryptophan metabolite L-kynurenine mediates the immunosuppression across different cancer types by activating aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) ligands [21, 22], and yet, the others took on opposite standpoint that microbe-oriented tryptophan metabolite, indole-3-aldehyde (I3A), enhanced antitumoral immunity as a potent AhR ligand to activate ICI in preclinical melanoma [23]. Furthermore, positive response to ICI in pancreatic cancer seemed embraced higher concentrations of microbe-generated tryptophan metabolite indole-3-acetic acid (3-IAA) [24]. Collectively, tryptophan and its derivatives produced by lower respiratory tract microbiome deserve detailed investigation to further uncover their potential clinical values among monitoring and prediction to antitumor immunotherapy.

In this study, we performed shotgun metagenomic sequencing to bronchoalveolar lavage fluid collected from lower respiratory tract in 28 patients with non-treated NSCLC and 28 patients after receiving standard ICIs therapeutic regimes to compare microbial differences. Additionally, targeted tryptophan sequencing was also carried out on those received ICIs interventions subgroups to analyze potential correlations between targeted metabolic discrepancy and responses. Our study attempted to uncover the role of lower respiratory tract microbiome in antitumoral immunotherapy and further suggested that anti-PD-1 immunotherapy may alter lower respiratory tract microbiome composition and interact with its metabolites to potentially determine treatment efficacy and long-term prognosis in advanced NSCLC.

Materials and methods

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study involved human participants and was approved by Medical Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Fourth Military Medical University (NO. XJYY-LL-FJ-002). All participants enrolled in this study have signed informed consent based on the voluntary principle before sample collection performance. This research presented here has been performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines.

Study cohort description and participant enrollment

The study included a total of 56 advanced NSCLC participants at the Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care of Medicine, the First Affiliated Hospital of Air Force Medical University from May 2022 to December 2022. The enrollment was assignment to randomizations and blinding. The final diagnosis depended on the pathological characteristics of electronic bronchoscopy-mediated needle biopsy tissue samples after bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) collection. These participants were then equivalently divided into two groups as untreated and treated, former of which received no medication before initial treatment as negative control and latter of which received at least four cycles of standardized treatment of immune checkpoint inhibitors. In detail, after at least four cycles of standardized treatment of immune checkpoint inhibitors with 3 mg/kg intravenously every 3 weeks until disease progression or intolerable toxicity, examined by computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, all enrolled patients, who refused to combine or failed to undergo chemotherapy, were classified into responder and non-responder subgroups mainly by their responses to antitumor schemes as defined by RECIST 1.1, excluding those with pseudo-progression and delayed immune treatment efficacy. Subjects were excluded if they had a history of antibiotics and glucocorticoid drugs utilization in the past 3 months, combined respiratory acute or chronic infectious diseases, significant alterations in dietary habits within previous 3 months, and other conditions in which they failed to perform immunotherapy normatively. Clinical characteristics were retrieved from electronic medical records and standardized case report forms. In detail, participants enrolled were at stage IIIB/IV according to TNM staging (Version 8th) and received immune checkpoint blockade monotherapy or combined regimes according to the Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology, CSCO; Version 2022) and Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (National Comprehensive Cancer Network, NCCN; Version 2022). Basic information is displayed in Table 1, including sex, gender, and subject demographics. Workflow is shown in Fig. 1B.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the cohort

| Untreated (n = 28) | Treated (n = 28) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics/anthropometric | |||

| Age/year | 63.0 ± 9.5 | 61.6 ± 10.5 | 0.605 |

| Male/Female | 21/7 | 24/4 | 0.313 |

| BMI(kg/m2) | 24.00 ± 3.21 | 22.64 ± 3.73 | 0.150 |

| Tumor stage (%) | 0.163 | ||

| III | 7 | 3 | |

| IV | 21 | 25 | |

| Tumor type (%) | 0.312 | ||

| ADC | 12 | 12 | |

| LCC | 9 | 13 | |

| Others | 7 | 3 | |

| Tumor metastasis | 0.064 | ||

| Metastasis | 18 | 24 | |

| Non-metastasis | 10 | 4 | |

| Ki-67(%) | 68.64 ± 0.23 | 55.36 ± 0.24 | 0.041* |

| PD-L1 | |||

| Yes | 11 | 19 | 0.032* |

| No | 17 | 9 | |

| Smoking status (%) | 0.567 | ||

| Never smoker | 10 | 8 | |

| Ever smoker | 18 | 20 | |

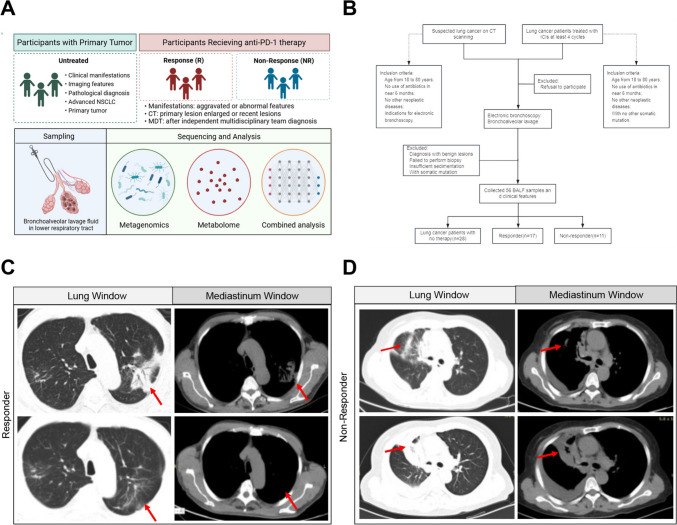

Fig. 1.

Study design and participant cohort enrollment. A Flow chart of this study. B Workflow demonstrating the cohort enrollment and exclusion criterion. Subsets are divided into patients with no therapy (Untreated, n = 28) and patients with anti-PD-1 therapy (Treated, n = 28), latter of which was further divided into Non-Responder (NR, n = 11) and Responder (R, n = 17) according to RECICST 1.1. C and D Representative Computed Tomography (CT) scanning images of indicated participants in NR (left) and R (right) at the identical layers among the same participant. Lung and mediastinum windows are shown as marked. Red arrow, suspected lesion sites

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluids collection and sample preservation

The same bronchoscopy specialist used a sterile bronchoscope to collect BALF samples. Performed following the standard protocol, the target tumor lesion was treated with preheated sterile physiological saline for 50-60 ml, maintaining a stable recovery rate > 60%. All samples intended for microbial and metabolomics analysis were under centrifugation at 4℃, 12000 rpm for 40 min. Centrifugal sedimentation and supernatant were segregated and restored at -80℃ for microbial and targeted metabolomics analysis concurrently until processing. All processes strictly abided by sterile operating standards. Detailed information is also displayed in our previous study [25].

DNA extraction and metagenome sequencing

Total DNA was extracted from BALF samples using the QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (RRID: SCR_008539; QIAGEN, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (www.qiagen.com/handbooks). The concentration and quality of extracted DNA were determined using Qubit® dsDNA Assay Kit in Qubit® 2.0 Fluorometer (RRID:SCR_008817; Life Technologies, CA, USA). The library was prepared using the Illumina’s NEBNext® Ultra DNA library preparation kit (RRID: SCR_010233. NEB, USA). And the DNA sample was fragmented by sonication to a size of 350 bp for Illumina sequencing with further PCR amplification. At last, PCR products were purified by AMPure XP Capabilities (RRID: SCR_008940; Beckman Coulter, USA, https://www.beckmancoulter.com/) and libraries were analyzed for size distribution by Agilent2100 Bioanalyzer (RRID: SCR_019715; https://www.agilent.com/cs/library/posters/Public/BioAnalyzer) and quantified using real-time PCR.

Pre-processing of sequencings and metagenome assembly

Fastp software (RRID: SCR_016962; https://github.com/OpenGene/fastp) was used for raw data quality control, default software parameters were selected to preprocess raw data obtained by Illumina HiSeqX platform (RRID: SCR_016385; https://www.illumina.com/systems/sequencing platforms/hiseq-x.html), and clean data were obtained for subsequent analysis. Reads were aligned to the human genome by the Bowtie2 software (RRID: SCR_016368; v2.3.4, https://bowtiebio.sourceforge.net/bowtie2/index.shtml ), and any hit associated with the reads and their mated reads were removed. Metagenomics data were assembled using MEGAHIT (RRID:SCR_018551; v1.2.9, https://github.com/voutcn/megahit), and contigs with the length being or more than 500 bp were selected as the final assembling result. Open reading frames from each assembled contigs were predicted via GeneMark (RRID:SCR_011930; v3.38, http://opal.biology.gatech.edu/GeneMark/). Combine the ORF prediction results of all samples and mixed assembly, and use CD-HIT (RRID:SCR_007105; http://weizhong-lab.ucsd.edu/cd-hit/) software to remove the redundancy, so as to obtain the non-redundant initial gene catalog [25]. By default, identity 95% and coverage 90% were used for clustering, and the longest sequence was selected as the representative sequence. Clean data of each sample were aligned to the initial gene catalog by using Bowtie2 (as mentioned above) to calculate the number of reads of the genes on each sample alignment. Genes with reads ≤ 2 in each sample were filtered out to finally determine the gene catalog by Unigene (RRID:SCR_004405; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/unigene) for additional analysis. Based on the number of reads aligned and the length of gene, the abundances of genes in each sample were calculated by the following formula, in which R was the number of gene reads on alignment, and L was the length of gene.

Species annotation and functional profiles

On the basis of the NCBI RefSeq non-redundant proteins database (RRID:SCR_022748; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/refseq/about/nonredundantproteins/), we annotated gene sets for bacteria, fungi, viruses, protozoa, and archaea using DIAMOND (RRID:SCR_009457; v0.9.9.110, https://github.com/bbuchfink/diamond). On the basis of a unified database, each gene was assigned to the highest-scoring taxonomy, which facilitated simultaneous assessment of these microbial species in the lower respiratory tract of enrolled participants. We used the lowest common ancestor (LCA) algorithm to obtain the number of genes and abundance for each sample in each taxonomic hierarchy (kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species). Krona analysis, relative abundance overview, abundance clustering thermal map, principal component analysis (PCA), and non-metric multi-dimensional scaling (NMDS) dimensional reduction analysis, Anosim intergroup (intragroup) difference analysis, and LEfSe multivariate statistical analysis of intergroup differential species were performed based on the abundance tables at each classification level. The KEGG annotation was also conducted using DIAMOND against the database (RRID:SCR_012773; http://www.kegg.jp/) with an e value cutoff of 1 × 10−5. Based on the abundance tables at each classification level and the number statistics of annotated genes, relative abundance overview, abundance clustering heat map, PCA and NMDS dimensionality reduction analysis, Anosim intergroup (intragroup) difference analysis based on functional abundance were carried out separately.

Tryptophan-targeted metabolomic sequencing

Tryptophan and its metabolites were sequenced by MetWare (http://www.metware.cn/) based on the AB Sciex QTRAP 6500 LC–MS/MS platform (RRID:SCR_021831). To put it simply, samples were thawed on ice, extracted with methanol, and internal standard was added. The Waters ACQUITY UPLC HSS T3 C18 (100 mm × 2.1 mm i.d., 1.8 µm) was used for liquid chromatography. The mobile phase for liquid chromatography was water with 0.1% formic acid (A) and acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid (B). Tryptophan and its metabolites were analyzed using scheduled multiple reaction monitoring. Data acquisitions were performed using Analyst®TF software (RRID:SCR_015785). And MultiQuant software on SCIEX (RRID:SCR_023651) was used to quantify all metabolites. Analyses such as PCA and OPLS-DA were implemented using R packages. Identified metabolites were annotated using KEGG database (RRID:SCR_012773; http://www.kegg.jp/compound), and annotated metabolites were then mapped to KEGG pathway database (RRID:SCR_018145; https://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (RRID:SCR_016479). Demographic and clinical variables were shown as the mean (standard deviation) or the median (interquartile range) for continuous variables and number (%) for categorical variables. Continuous variables were compared between groups by the independent t test and Chi-square test for classification variables. The statistical significance level was set at P < 0.05*, P < 0.01**, P < 0.001***. No significance was labeled as P > 0.05 ns. Detailed statistical methods are described in the figure legends and Results section, respectively.

Results

Study design and participant cohort enrollment

We included a total of 56 participants with NSCLC in this study, in which computed tomography (CT) scanning highly suggestive of malignant lung tumors confirmed by electronic bronchoscopy biopsy ultimately. In detail, this cohort was divided into two groups including 28 participants received no treatment as control (untreated) and 28 participants who received anti-PD-1 immunotherapy (treated), which was further split into responder and non-responder subgroups after standardized therapeutic regimes based on the RICIST 1.1 criteria (Fig. 1A and B). As expected, there were no significant differences in age, gender, BMI, or tumor type between the untreated and treated groups (P > 0.05 ns) as previous reported [25]. The images complied with the grouping criteria as well, and representative imaging graphs were posted (Fig. 1C and D). Baseline clinical characteristics of enrolled participants are summarized in Table 1.

Relative abundance of lower respiratory tract microbiome reconfigured in response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy

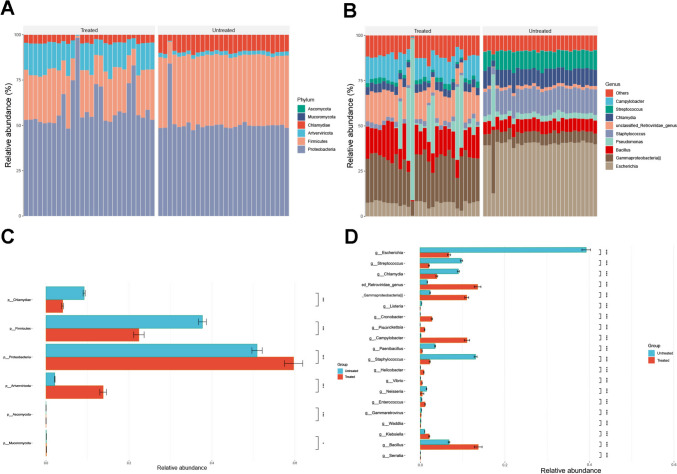

To investigate whether antineoplastic drugs affected the composition of the lower respiratory tract microbiome, we compared the discrepancies in the lower respiratory tract microbiome between the treated and untreated groups by metagenomic sequencings. Correspondingly, both groups were predominantly composed of Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, and Chlamydiae at the phylum level, with the virus Artverviricota also being found (Fig. 2A). However, the relative abundance of Proteobacteria was enriched in the treated group than in the untreated group, while Firmicutes and Chlamydiae were enriched in the untreated group (P < 0.05*) (Fig. 2C). The top eight represented genera in lower respiratory tract were Escherichia, Gammaproteobacteria, Bacillus, Pseudomonas, Staphylococcus, Chlamydia, Streptococcus, and Campylobacter (Fig. 2B). The results of the Wilcoxon rank-sum nonparametric test showed that the treated group had higher concentrations of Gammaproteobacteria and Campylobacter, while untreated group was enriched with Escherichia, Streptococcus, Chlamydia, and Staphylococcus (Fig. 2D). These results indicated that immune checkpoint inhibitors might reconfigure lower respiratory tract microbiome by changing relative abundance of several dominant microbes at genus level which presented an insight to monitor immunotherapy-mediated antitumoral performances from a microbial perspective.

Fig. 2.

Relative abundance of lower respiratory tract microbiome altered in response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. A Microbial taxonomy of each participant at phylum level with indicated subgroups. B Microbial taxonomy of each participant at genus level with indicated subgroups. C and D, Bot plots display the prevalence of the relative abundance for most prevalent phylum and genera (present at ≥ 3% in any one of the samples), illustrating the dissimilarity in microbial composition of each group. Significance was determined using Kruskal–Wallis rank-sum non-parametric test on each plot (P > 0.05ns not shown)

Lower respiratory tract microbial diversity decreased with standardized therapeutic interventions of immune checkpoint inhibitors

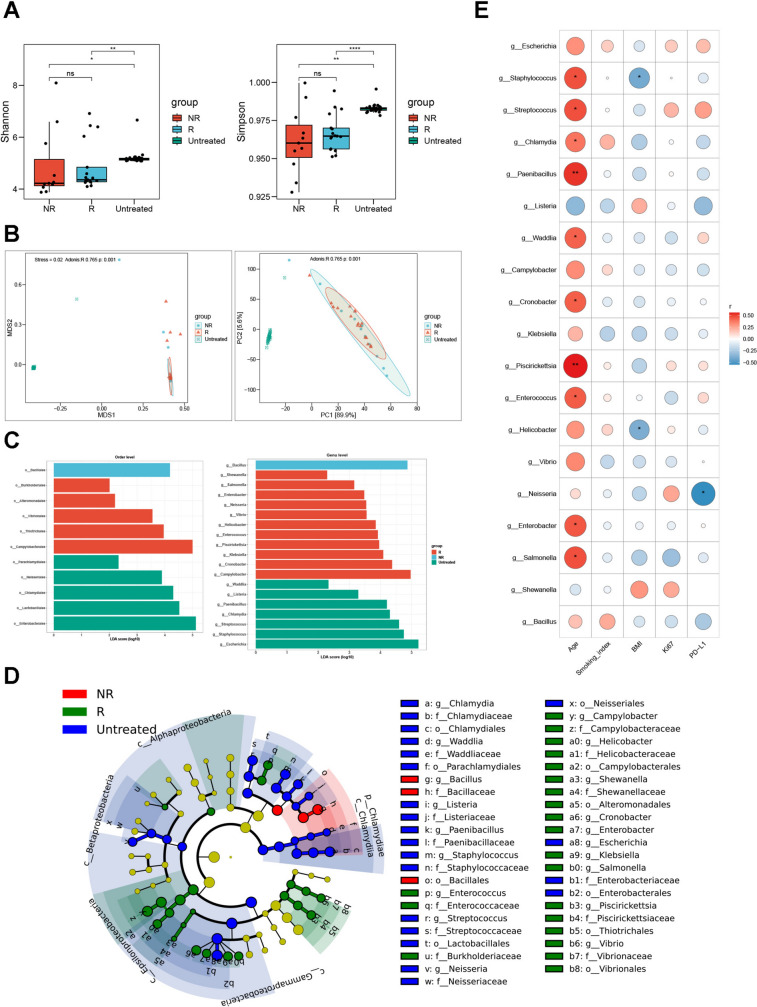

Next, we focused on the microbial community differences between treated, which was further divided into responder and non-responder subgroups according to clinical responses and untreated in terms of microbiome diversity. To surprise, both Shannon index and Simpson index based on Kruskal–Wallis rank-sum nonparametric test showed that the diversity of the treated group was significantly lower than that of the untreated group (P < 0.05*) (Fig. 3A). Then we used PCA analysis and NMDS analysis based on Bray–Curtis distance to compare the beta diversity between groups. Correspondingly, PCA and NMDS ordination with 95% confidence interval ellipses revealed a better differentiation in the microbial communities between both groups (Fig. 3B). The diversity analysis and the examination of various abundance levels determined differences in the microbial communities between them both. To further explore which candidate microbe drove these dominant differences, we performed LEfSe analysis, finding that the results were similar to those acquired by Wilcoxon rank-sum test (Fig. 3C and D). We then applied Spearman correlation analysis to identify the differential microbes at species level found by LEfSe analysis and clinical characteristics, so as to investigate whether microorganisms and patient clinical characteristics have a link. The results showed that smoking index and Ki-67 were not associated with bacteria, while the abundance of some pathogenic microorganisms, such as Salmonella, Enterobacter, Enterococcus, or conditional pathogenic ones, such as Cronobacter, Chlamydia, Streptococcus, and Staphylococcus, increased with age growing. There was a negative link between BMI and the abundance of Helicobacter and Staphylococcus. Remarkably, we also observed an adverse relationship between PD-L1 and Neisseria (Fig. 3E). These results indicated that microbiome alterations correlated closely to the application of standardized therapeutic interventions of immune checkpoint inhibitors, which might be achieved by reducing the diversities of lower respiratory tract microbiome besides their relative abundances to some extent, albeit the presence of selective bias in this cohort.

Fig. 3.

Microbial diversity in lower respiratory tract reduced after receiving anti-PD-1 therapy. A Alpha diversity measured by inverse Shannon (up) and Simpson (down) index using Kruskal–Wallis rank-sum non-parametric test. P values were shown on the top. B Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS, left) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA, right) of beta diversity measurements based on Bray–Curtis distances for indicated subgroups. Each symbol represented one individual patient. C and D Cladograms showing microbial compositional differences at indicated subgroups analyzed by linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) method. From domain to species with linear discriminant analysis score (LDA) > 2. E Heatmap of the correlation between candidate microbial species and clinical characteristics. P < 0.05*, P < 0.01**, P < 0.001***, P < 0.0001****, ns, no significance

Lower respiratory tract microbiome performed as predictive microbial markers to evaluate clinical responses to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy

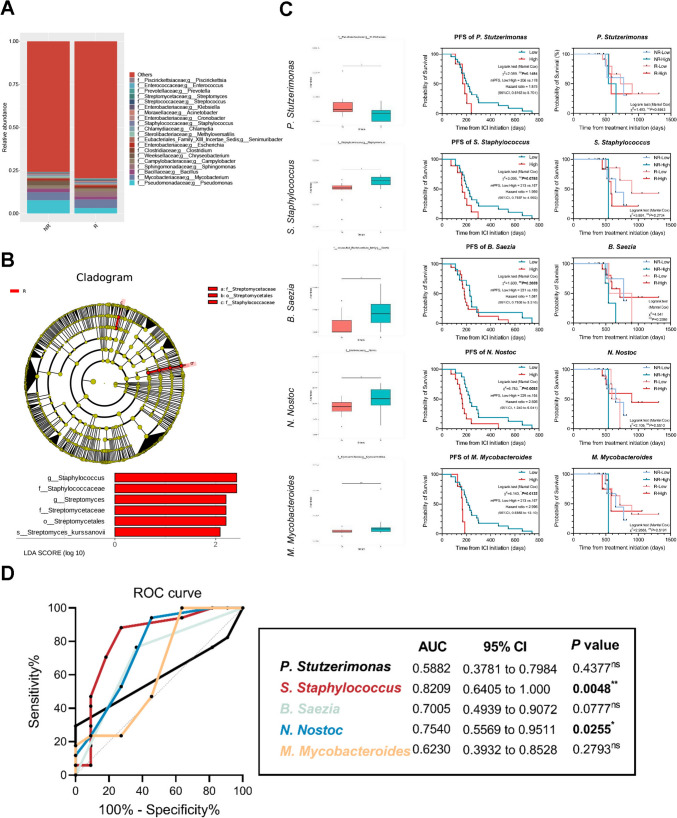

In order to further explore whether the lower respiratory tract microbiome was involved in antitumor response, we divided the treated group receiving ICIs into responder (R) and non-responder (NR) subgroups according to RECIST criteria (version 1.1). After routine reorganization on core-pan analysis based on the number and abundance of genes in each sample, correspondingly, there was a difference in the composition of lower respiratory tract microbiome between R and NR subgroups at genus level in microbiota compositional analysis. The top ten genera are Pseudomonas, Mycobacterium, Bacillus, Sphingomonas, Campylobacter, Chryseobacterium, Clostridium, Escherichia, Senimuribacter, and Methyloversatilis (Fig. 4A). Meanwhile, LEfSe analysis also confirmed that Staphylococcus and Streptomyces were enriched in R subgroup (Fig. 4B), which further indicated their distinguishable performance to immunotherapy. Then, Metastats analysis further implied that the relative abundance of the 22 representative genera was identified with notable differences between two subgroups, such as Stutzerimonas, Saezia, Staphylococcus, Nostoc, and Mycobacteroides (Fig. 4C, left), several of which were overlapped with previous results. In order to explore their potent decisive roles in determining long-term survivals, we examined the connections between relative microbial abundances and survivals using the Kruskal–Wallis rank-sum nonparametric test. In detail, these participants were divided into low and high subsets to compare indicated progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) according to an averaged biomass on relative abundance of each microbe. Interestingly, the results showed that low abundance of indicated microbes was seemingly associated with relatively extended PFS (Fig. 4C, middle), even though they were more abundant in the R subgroup than those in NR, partially attributed to restricted cohort, and microbial diversity rather than relative abundances in specific ones. However, OS reached no significance for further divisions on subgroups (Fig. 4C, right). Based on results above, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were launched to evaluate diagnostic abilities of each indicated candidate by assessing the area under the curve (AUC). Although the presence of limited samples, these indicated microbes also reached a relatively satisfying diagnostic performances, especially Staphylococcus to 0.8209 (P < 0.05*) and Nostoc to 0.7540 (P < 0.05*) (Fig. 4D). Taken together, these results further illustrated that lower respiratory tract microbiome had the potential to predict clinical outcomes to anti-PD-1 therapeutic regimes in a relative abundance-dependent manner, further presenting an operational, interventional approach to modulate its responses after amounts of well-designed experiments in the next steps.

Fig. 4.

Microbial elements in lower respiratory tract acted as potential candidates for predicting clinical responses to anti-PD-1 therapy. A Relative abundance of the lower respiratory tract microbiota in the NR and R subgroups at genus level. B Cladograms showing microbial compositional differences at both subgroups analyzed by linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) method. From domain to species with linear discriminant analysis score (LDA) > 2. C Bot plots display the prevalence of the relative abundance for most prevalent genera (Left, present at ≥ 3% in any one of the samples), illustrating the dissimilarity in microbial composition of each group. Significance was determined using Kruskal–Wallis rank-sum non-parametric test on each plot (P > 0.05 ns not shown). PFS of each candidate microbe are divided into High and Low subgroups according to the average expression (Middle). OS of each candidate microbe are divided into High and Low subgroups among R and NR, respectively (Right). D ROC curves of indicated microbes based on survival days. P < 0.05*, P < 0.01**, P > 0.05 ns; ns, no significance

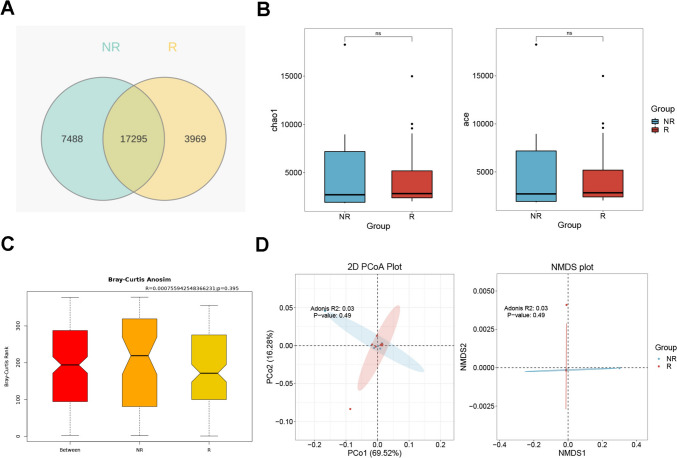

Microbial diversity failed to be the dominant predictor to ICIs within preferred clinical responses

As for microbial diversity in lower respiratory tract microbiome as mentioned above, there seemed to be no significant differences to predict specific clinical responses to immunotherapy. In particular, we identified total 17295 overlapped microbes by metagenomic sequencings, while the R group had 3969 unique genes and the NR group had 7488 unique genes (Fig. 5A). Although no significant differences in α diversity or β diversity were observed in this cohort (Fig. 5B-D), we also found tendencies that lower respiratory tract microbiome seemingly responded differently to ICI interventions according to quite unidentical outcomes by partially overlapped microbes, which deserved verifications in additional extensive cohorts.

Fig. 5.

Clinical responses to anti-PD-1 therapy embraced a relative constancy in microbial diversity among lower respiratory tract. A Venn plots of differentiated candidates within NR and R. B Chao and ACE analysis of indicated subgroups. ns, no significance. C Anosim showing the outcomes of beta diversity measurements based on Bray–Curtis distances for NR and R. R2 and P values are shown on the top. D Principal Coordinate analysis (PCoA, left) and non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS, right) of beta diversity measurements based on Bray–Curtis distances for NR and R. Each symbol represented a single participant

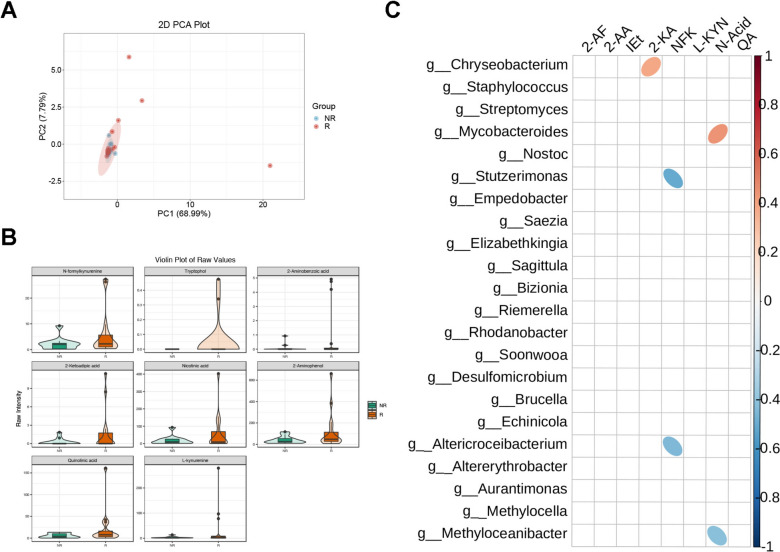

Combined analysis of targeted tryptophan metabolomics and lower respiratory tract microbial candidates

Taken the dominant role of tryptophan as key microbe-derived ligands to AhR-included endogenous cellular receptors, microbial-derived tryptophan sequencing was performed in BALF samples of R and NR subgroups. To our surprise, however, the clusters of PCA did not show significant separate visually and statistically (Fig. 6A). As for compositional analysis, a total of 8 tryptophan derivative products were found to significantly increase in the R subgroup (Fig. 6B), but there were no significant compositional differences with PD-L1 expression (Supplementary Figs. 1, 2). These results indicated that unlike PD-L1 expression, tryptophan metabolites alone are short of independently diagnostic efficacy, and PD-L1 on the host failed to be dominant in tryptophan metabolites within complicated setting among enrolled cohorts. We then performed Spearman correlation analysis on the differential metabolites and various differential microorganisms. Accordingly, it revealed a negative correlation between N-formyl kynurenine and Stutzerimonas, as well as Altericroceibacterium. Conversely, 2-ketoadipic acid and nicotinic acid showed a positive correlation with Chryseobacterium and Mycobacteroides, respectively (Fig. 6C). These results illustrated that several specific microbes in lower respiratory tract might be primary sources of microbe-derived tryptophan metabolites to constitute individual microecological environments, further modulating drug responses to ICIs and their correlations with clinical manifestations.

Fig. 6.

Tryptophan metabolites correlated with preferred clinical response to anti-PD-1 therapy with indicated microbes. A Principal Component Analysis of beta diversity measurements based on Bray–Curtis distances for indicated subgroups. Each symbol represented one individual patient. B Violin plot of raw values of indicated tryptophan metabolites among NR and R. C Ellipse heatmap of indicated microbe with differentiated tryptophan metabolites

Discussion

Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy has been taken as a preferred therapeutic antitumoral strategy to non-mutated advanced NSCLC for recent years, and yet, from which partial participants fail to benefit, further suffering impaired clinical practices to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). During clinical processes in seeking for effective prediction biomarkers, recent studies have shown that the microbiome, including those in lower respiratory tract with relatively low biomass, play a crucial role in modulating responses to immunotherapy as a potential predictive biomarker. Taken diverse outcomes after antibiotics utilization in patients receiving ICIs into account, the presence of microbiome seems dominant on a double-edged standpoint, partially due to the co-existence of probiotics and pathogenic microbes spatiotemporally. But unfortunately, there was quite limited knowledge about the exact performance of lower respiratory tract microbiome in reconstructing cancer-related microecological environment among advanced NSCLC and their corresponding correlations after ICI interventions. In this study, we collected bronchoalveolar lavage fluids in lower respiratory tract from 56 participants with advanced-stage NSCLC treated with anti-PD-1 therapy or none equally, and compared their microbial discrepancy by performing metagenomic sequencing to identify ICI-mediated microbial alterations, and targeted metabolic alterations by tryptophan sequencing accordingly in different subgroups according to clinical response to immune checkpoint inhibitors, to uncover the potential microbial and targeted metabolite predictive effects.

Lower respiratory tract microbiome in modulating lung cancer behaviors has just been recognized for several years which used to be relatively neglected for decades. Indeed, recent studies have been conducted to identify that specific microbes in the lower respiratory tract may participate in the occurrence and biological modulations of lung cancer by inducing host inflammatory response, producing microbial toxins, and/or releasing microbial metabolites to transform the stability of the host genome and mediate signal transduction [26]. Lee and teammates suggested that Veillonella and Megasphaera were significantly more abundant in advanced NSCLC than those with benign diseases or the health, indicating their potential to serve as biomarkers for prediction [27]. The latest research also found that Veillonella is thought to be associated with the upregulation of IL17, PI3K, MAPK, and ERK pathways in the airway transcriptome, and in vivo study showed that lower airway dysbiosis with Veillonella led to decreased survival, increased tumor burden, IL17 inflammatory phenotype, and even activation of checkpoint inhibitor markers [28]. However, of noting, Veillonella was not detected in our studies, which may be attributed to variations in the population, restricted samples, and differences in sample types, but it also implied that other microbes in the lower respiratory tract might also possess the capacities of carcinogenesis. Interestingly, our study found that Escherichia, which is significantly associated with the occurrence of colorectal cancer, accounted for a high proportion in the untreated subgroup at the genus level, coupled with a statistically significant discrepancy to those in treated groups. In accordance, previous studies found that E. coli increased IL-17 and enhanced DNA damage in the colonic epithelium with faster tumor onset [29, 30]. Our findings provided a new perspective that Escherichia might be involved in the occurrence and development of NSCLC by inflammatory approaches. In addition, after analyzing the relationship between clinical characteristics and differentiated microbes, the relative abundance of potential pathogenic microbes, such as Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, and Chlamydia, also increased with growing age, which was partially approved by that as people aged, the quantity of probiotics declines, while the abundance of harmful bacteria increases [31]. This may also explain why older people have a greater chance of developing malignancies somewhat [32]. We had to admitted that conclusions drawn by different studies are quite discordant, which call for extensive sample cohorts and reasonable basic experimental verifications in the coming future.

In correspondence, the relative abundances of indicated microbes in the treated group, such as Streptococcus, Escherichia, Chlamydia, and Staphylococcus, were significantly reduced to those in untreated group, which were previously thought to be related to the development of multiple cancer types [33–35]. In fact, a considerable enrichment of Streptococcus at the genus level was achieved in a small-scale study of sputum samples from eight never-smoking female lung cancer cases and eight never-smoking female controls in China [36], which were also obtained from another NSCLC cohort to healthy controls [37]. Our research also intended to illustrate from a microbial perspective that ICIs not only activated the antitumoral performance of T cells, but also reshaped systemic microbial composition in lower respiratory tracts to facilitate beneficial immune microenvironment in advanced NSCLC. Streptococcus in gut microbiome was positively associated with favored anti-PD-1/PD-L1 responses in different GI cancer types [38]. Zhang and colleagues observed a significant positive correlation between Streptococcus in the lower respiratory tract and the abundance of CD8+T cells [39]. In contrast, a short PFS was associated with both Streptococcus salivarius and Streptococcus vestibularis in NSCLC patients receiving anti-PD-1 treatment [40]. It seemed paradoxical that tumorigenic microbes also exhibit a preference for immune responses, which might be attributed to the pathogenic diversity of microbes at different diseases, and microbial antigens on subspecies mediated divergent immune responses to activate antitumoral immune balance [41]. We had to be admitted that such differences further highlighted the complexity of the interplay between the immune system and the malignancy, which deserved additional attentions. Correspondingly, our study showed that the lower respiratory tract of lung cancer patients treated with ICIs showed a marked increase in the proportion of probiotic Bacillus compared to the untreated group. Bacillus can not only activate innate immune responses to drive host clearance of pathogens [42], but also have the capability of biosynthesis in organic acids, such as SCFAs, which can enhance immune responses by inducing GPCRs-mediated dendrite protrusion of intestinal C-X3-C motif chemokine receptor 1+ cells [43]. Paradoxically, LEfSe analysis showed that Bacillus was the predominant genus in non-responders, which means that its role in lower respiratory tract immunity is complex and requires further investigation. However, our study cannot confirm that this change is caused by immune intervention, and we can only elaborate on the correlation. In the future, we can verify the causal relationship through studies with larger sample size and animal experiments.

Of note, diversity of the microbiome is essential for immune balance rather than relative abundances alone [44], which reflects the richness and evenness of microorganisms in a specific environment. Compared with restricted regulatory function from a single microbe, multiple microbes are prone to collaborate in concert to maintain the natural balance of relatively open environments by dynamic microbial exchanges with outsides, such as intestinal tracts and lower respiratory tracts [45]. From this standpoint, immune microenvironment in these tracts is liable to be reassembled by inherent colonized microbes with low biomass and relative microbial diversities, compositional disturbance of which may imbalance local and even integral immune system. A pan-cancer analysis of the microbiome in metastatic cancer validated that microbial communities of various types of cancer are generally rich and balanced. And in those with high microbial diversity, multiple pathways involved in extracellular matrix (ECM) tissue and antimicrobial peptides (AMP) are significantly enriched, which further promoted inherent and acquired immune cells infiltration [46]. Additionally, a significant decrease in bacterial richness was observed in patients receiving only ICB treatment; after receiving chemotherapy drugs with known antibiotic modes of action, such as doxorubicin/epirubicin and bleomycin, microbial abundance also decreased, which further demonstrated immunotherapy may reshape community, especially more pronounced in responding one [46]. As for those in lower respiratory tracts, several researches have illustrated drastic alterations on microbial composition imbalance immune status by reducing its diversity. There is a notable decrease in the variety of lung cancer cohort when compared to the healthy or the healthy lung segment [37, 47]. Commensal bacteria in lungs stimulated Myd88-dependent IL-1β and IL-23 production from myeloid cells, inducing proliferation and activation of Vγ6+Vδ1+γδ T cells that produced IL-17 and other effector molecules to promote inflammation and tumor cell proliferation [48]. Our study found a substantial decrease in the alpha diversity of the lower respiratory tract microbiota in lung cancer patients receiving ICIs, further supporting the point that antitumoral immunotherapy may reshape microbial constitution partially by disrupting its microbial composition.

However, there still existed several unavoidable limitations in our study. First, our study is a retrospective study of single center, which may lead to a selective bias, and the restricted cohort may not be able to fully reflect the patients with lower respiratory tract flora composition. Secondly, BALF samples were not taken from the same patient before and after receiving ICIs, which was insufficient to provide a comprehensive and intuitive conclusion to the interventional effects of immunotherapy on the lower respiratory tract flora. Additionally, for microbial metabolites, we used a targeted tryptophan assay rather than a broad metabolic profiling assay, which may miss the impacts of other metabolites on the lower airway immune microenvironment due to the complexity of lower airway flora metabolism. Finally, specific mechanistic principles could not be explored because it was not possible to isolate certain species from the immunotherapy response group for animal experiments.

Collectively, our study descripted the distinct compositional characteristics of microecological environment in lower respiratory tract among different responses to ICI interventions, further identifying metagenomic sequencing-based microbiomes, and untargeted metabolome as potent predictors of responder selection using integrated analyzing approaches. This study demonstrated the potential correlations of these enrolled components, highlighting clinical response predictive potencies from multiple dimensional perspectives. Our findings also inspired detailed investigations into the practical applications of microecological characteristics-driven markers in ICI therapeutic regimes by bronchoalveolar lavage fluids.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all participants who were enrolled in this study and all the clinical staff that assisted with the sample collections and processing. We are grateful to thank Guangzhou Gene Denovo Biotechnology Co., Ltd for assisting in sequencing and taxonomy profiling.

Author contributions

X. Chen, Q. Ju and D. Qiu were responsible for data acquisition, statistical analysis, and initial writings. They were listed as their practical contributions after all agreements. Y. Zhou collected basic information and details from enrolled cohort. Y. Wang provided assistances of microbial and metabolic aspects. X. Zhang provided financial assistance in this study. J. Li, M. Wang, and N. Chang enrolled participants in clinics according to relative standards. X. Xu, Y. Zhang and T. Zhao contributed to figure draft and graphs. K. Wang provided funding acquisition, and supervision during all processes. Y. Zhang was responsible for writing review, project administration and study design. J. Zhang provided financial supporting, writing-review and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NO. 82473215), Clinical Booster Project of Fourth Military Medical University (NO.2021LC2115), and Shaanxi San-qin Special Support Program Innovation and Entrepreneurship Team—Precise Diagnosis, Treatment and Standardized Management of Lung Cancer to Prof. Zhang; National Natural Science Foundation of China (NO.82273226), Young Elite Scientist Sponsorship Program by China Association for Science and Technology (NO.2020QNRC001) to Prof. Wang, and National Natural Science Foundation of China (NO. 82103446) to Dr. Zhang.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed in this study were oriented from a standardized clinical process and are included in this published article. Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the NCBI Short Read Archive with the Primary Bio-project accession code PRJNA991321 on the following link: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA991321. Metagenomic sequencing data of those receiving anti-PD-1 immunotherapy was deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive with the Primary Bio-project accession code CRA020393 on the following link: https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsub/submit/gsa/subCRA032908. Targeted tryptophan metabolome was also deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive with the Primary Bio-project accession code PRJCA032109 on the following link: https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/bioproject/browse/PRJCA032109. Additional supports for sequencings could also be directed to and will be fulfilled by Prof. Jian Zhang at zjfmmu19700227@163.com.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Xiang-xiang Chen, Qing Ju, and Dan Qiu have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Ke Wang, Email: wangke@fmmu.edu.cn.

Yong Zhang, Email: 15829245717@163.com.

Jian Zhang, Email: zjfmmu19700227@163.com.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F (2021) Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 71(3):209–249. 10.3322/caac.21660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borghaei H, Gettinger S, Vokes EE, Chow LQM, Burgio MA, de Castro CJ et al (2021) Five-year outcomes from the randomized, phase iii trials checkmate 017 and 057: nivolumab versus docetaxel in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 39(7):723–733. 10.1200/jco.20.01605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howlader N, Forjaz G, Mooradian MJ, Meza R, Kong CY, Cronin KA et al (2020) The effect of advances in lung-cancer treatment on population mortality. N Engl J Med 383(7):640–649. 10.1056/NEJMoa1916623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mazieres J, Rittmeyer A, Gadgeel S, Hida T, Gandara DR, Cortinovis DL et al (2021) Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in pretreated patients with nsclc: final results from the randomized phase 2 POPLAR and phase 3 OAK clinical trials. J Thorac Oncol Off Publ Int Assoc Study Lung Cancer 16(1):140–150. 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peters S, Reck M, Smit EF, Mok T, Hellmann MD (2019) How to make the best use of immunotherapy as first-line treatment of advanced/metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. Annal Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol 30(6):884–896. 10.1093/annonc/mdz109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang X, Qiao Z, Aramini B, Lin D, Li X, Fan J (2023) Potential biomarkers for immunotherapy in non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 10.1007/s10555-022-10074-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jin Y, Dong H, Xia L, Yang Y, Zhu Y, Shen Y et al (2019) The diversity of gut microbiome is associated with favorable responses to anti-programmed death 1 immunotherapy in Chinese patients with NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol Off Publ Int Assoc Study Lung Cancer 14(8):1378–1389. 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng WY, Wu CY, Yu J (2020) The role of gut microbiota in cancer treatment: friend or foe? Gut 69(10):1867–1876. 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hakozaki T, Richard C, Elkrief A, Hosomi Y, Benlaïfaoui M, Mimpen I et al (2020) The gut microbiome associates with immune checkpoint inhibition outcomes in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Immunol Res 8(10):1243–1250. 10.1158/2326-6066.Cir-20-0196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martini G, Ciardiello D, Dallio M, Famiglietti V, Esposito L, Corte CMD et al (2022) Gut microbiota correlates with antitumor activity in patients with mCRC and NSCLC treated with cetuximab plus avelumab. Int J Cancer 151(3):473–480. 10.1002/ijc.34033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Botticelli A, Vernocchi P, Marini F, Quagliariello A, Cerbelli B, Reddel S et al (2020) Gut metabolomics profiling of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients under immunotherapy treatment. J Transl Med 18(1):49. 10.1186/s12967-020-02231-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gopalakrishnan V, Spencer CN, Nezi L, Reuben A, Andrews MC, Karpinets TV et al (2018) Gut microbiome modulates response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Science 359(6371):97–103. 10.1126/science.aan4236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dick S, Turner S (2020) The airway microbiome and childhood asthma - what is the link? Acta Medica Academica 49(2):156–163. 10.5644/ama2006-124.294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Enaud R, Lussac-Sorton F, Charpentier E, Velo-Suárez L, Guiraud J, Bui S et al (2023) Effects of lumacaftor-ivacaftor on airway microbiota-mycobiota and inflammation in patients with cystic fibrosis appear to be linked to pseudomonas aeruginosa chronic colonization. Microbiol Spectr 11(2):e0225122. 10.1128/spectrum.02251-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salama KSM, Moazen EM, Elsawy SB, Kotb SF, Mohammed EM, Tahoun SA et al (2023) Bacterial species and inflammatory cell variability in respiratory tracts of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation: a multicentric study. Infect Drug Resist 16:2107–2115. 10.2147/idr.S402828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Man WH, de Steenhuijsen Piters WA, Bogaert D (2017) The microbiota of the respiratory tract: gatekeeper to respiratory health. Nat Rev Microbiol 15(5):259–270. 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dickson RP, Erb-Downward JR, Falkowski NR, Hunter EM, Ashley SL, Huffnagle GB (2018) The lung microbiota of healthy mice are highly variable, cluster by environment, and reflect variation in baseline lung innate immunity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 198(4):497–508. 10.1164/rccm.201711-2180OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li R, Li J, Zhou X (2024) Lung microbiome: new insights into the pathogenesis of respiratory diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther 9(1):19. 10.1038/s41392-023-01722-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jang HJ, Choi JY, Kim K, Yong SH, Kim YW, Kim SY et al (2021) Relationship of the lung microbiome with PD-L1 expression and immunotherapy response in lung cancer. Respir Res 22(1):322. 10.1186/s12931-021-01919-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Helmink BA, Khan MAW, Hermann A, Gopalakrishnan V, Wargo JA (2019) The microbiome, cancer, and cancer therapy. Nat Med 25(3):377–388. 10.1038/s41591-019-0377-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campesato LF, Budhu S, Tchaicha J, Weng CH, Gigoux M, Cohen IJ et al (2020) Blockade of the AHR restricts a Treg-macrophage suppressive axis induced by L-Kynurenine. Nat Commun 11(1):4011. 10.1038/s41467-020-17750-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Labadie BW, Bao R, Luke JJ (2019) Reimagining IDO pathway inhibition in cancer immunotherapy via downstream focus on the tryptophan-kynurenine-aryl hydrocarbon axis. Clin Cancer Res Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res 25(5):1462–1471. 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-18-2882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bender MJ, McPherson AC, Phelps CM, Pandey SP, Laughlin CR, Shapira JH et al (2023) Dietary tryptophan metabolite released by intratumoral lactobacillus reuteri facilitates immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment. Cell 186(9):1846–62.e26. 10.1016/j.cell.2023.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tintelnot J, Xu Y, Lesker TR, Schönlein M, Konczalla L, Giannou AD et al (2023) Microbiota-derived 3-IAA influences chemotherapy efficacy in pancreatic cancer. Nature 615(7950):168–174. 10.1038/s41586-023-05728-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.PD-1 inhibitors raise survival in NSCLC. Cancer Discov 2014;4(1):6 10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-nb2013-164 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Goto T (2022) Microbiota and lung cancer. Semin Cancer Biol 86(Pt 3):1–10. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2022.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee SH, Sung JY, Yong D, Chun J, Kim SY, Song JH et al (2016) Characterization of microbiome in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients with lung cancer comparing with benign mass like lesions. Lung Cancer 102:89–95. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2016.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsay JJ, Wu BG, Sulaiman I, Gershner K, Schluger R, Li Y et al (2021) Lower airway dysbiosis affects lung cancer progression. Cancer Discov 11(2):293–307. 10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-20-0263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joo JE, Chu YL, Georgeson P, Walker R, Mahmood K, Clendenning M et al (2024) Intratumoral presence of the genotoxic gut bacteria pks(+) E. coli, enterotoxigenic bacteroides fragilis, and fusobacterium nucleatum and their association with clinicopathological and molecular features of colorectal cancer. British J Cancer. 10.1038/s41416-023-02554-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tomita Y, Ikeda T, Sakata S, Saruwatari K, Sato R, Iyama S et al (2020) Association of probiotic clostridium butyricum therapy with survival and response to immune checkpoint blockade in patients with lung cancer. Cancer Immunol Res 8(10):1236–1242. 10.1158/2326-6066.Cir-20-0051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kiousi DE, Kouroutzidou AZ, Neanidis K, Matthaios D, Pappa A, Galanis A (2022) Evaluating the role of probiotics in the prevention and management of age-related diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 10.3390/ijms23073628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fane M, Weeraratna AT (2020) How the ageing microenvironment influences tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer 20(2):89–106. 10.1038/s41568-019-0222-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.He T, Cheng X, Xing C (2021) The gut microbial diversity of colon cancer patients and the clinical significance. Bioengineered 12(1):7046–7060. 10.1080/21655979.2021.1972077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Premachandra NM, Jayaweera J (2022) Chlamydia pneumoniae infections and development of lung cancer: systematic review. Infect Agents Cancer 17(1):11. 10.1186/s13027-022-00425-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Urbaniak C, Gloor GB, Brackstone M, Scott L, Tangney M, Reid G (2016) The microbiota of breast tissue and its association with breast cancer. Appl Environ Microbiol 82(16):5039–5048. 10.1128/aem.01235-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hosgood HD 3rd, Sapkota AR, Rothman N, Rohan T, Hu W, Xu J et al (2014) The potential role of lung microbiota in lung cancer attributed to household coal burning exposures. Environ Mol Mutagen 55(8):643–651. 10.1002/em.21878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu HX, Tao LL, Zhang J, Zhu YG, Zheng Y, Liu D et al (2018) Difference of lower airway microbiome in bilateral protected specimen brush between lung cancer patients with unilateral lobar masses and control subjects. Int J Cancer 142(4):769–778. 10.1002/ijc.31098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peng Z, Cheng S, Kou Y, Wang Z, Jin R, Hu H et al (2020) The gut microbiome is associated with clinical response to anti-pd-1/pd-l1 immunotherapy in gastrointestinal cancer. Cancer Immunol Res 8(10):1251–1261. 10.1158/2326-6066.Cir-19-1014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang C, Wang J, Sun Z, Cao Y, Mu Z, Ji X (2021) Commensal microbiota contributes to predicting the response to immune checkpoint inhibitors in non-small-cell lung cancer patients. Cancer Sci 112(8):3005–3017. 10.1111/cas.14979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dora D, Ligeti B, Kovacs T, Revisnyei P, Galffy G, Dulka E et al (2023) Non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with Anti-PD1 immunotherapy show distinct microbial signatures and metabolic pathways according to progression-free survival and PD-L1 status. Oncoimmunology 12(1):2204746. 10.1080/2162402x.2023.2204746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bonaventura P, Shekarian T, Alcazer V, Valladeau-Guilemond J, Valsesia-Wittmann S, Amigorena S et al (2019) Cold tumors: a therapeutic challenge for immunotherapy. Front Immunol 10:168. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu J, Chen Y, Imre K, Arslan-Acaroz D, Istanbullugil FR, Fang Y et al (2023) Mechanisms of probiotic bacillus against enteric bacterial infections. One Health Adv. 10.1186/s44280-023-00020-037521533 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morita N, Umemoto E, Fujita S, Hayashi A, Kikuta J, Kimura I et al (2019) GPR31-dependent dendrite protrusion of intestinal CX3CR1(+) cells by bacterial metabolites. Nature 566(7742):110–114. 10.1038/s41586-019-0884-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roviello G, Iannone LF, Bersanelli M, Mini E, Catalano M (2022) The gut microbiome and efficacy of cancer immunotherapy. Pharmacol Ther 231:107973. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2021.107973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mendez R, Banerjee S, Bhattacharya SK, Banerjee S (2019) Lung inflammation and disease: a perspective on microbial homeostasis and metabolism. IUBMB Life 71(2):152–165. 10.1002/iub.1969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Battaglia TW, Mimpen IL, Traets JJH, van Hoeck A, Zeverijn LJ, Geurts BS et al (2024) A pan-cancer analysis of the microbiome in metastatic cancer. Cell 187(9):2324–35.e19. 10.1016/j.cell.2024.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu G, Gail MH, Consonni D, Carugno M, Humphrys M, Pesatori AC et al (2016) Characterizing human lung tissue microbiota and its relationship to epidemiological and clinical features. Genome Biol 17(1):163. 10.1186/s13059-016-1021-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jin C, Lagoudas GK, Zhao C, Bullman S, Bhutkar A, Hu B et al (2019) Commensal microbiota promote lung cancer development via γδ t cells. Cell 176(5):998-1013.e16. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.12.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ren S, Feng L, Liu H, Mao Y, Yu Z (2024) Gut microbiome affects the response to immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Thorac cancer 15(14):1149–1163. 10.1111/1759-7714.15303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Muller AJ, Manfredi MG, Zakharia Y, Prendergast GC (2019) Inhibiting IDO pathways to treat cancer: lessons from the ECHO-301 trial and beyond. Seminar Immunopathol 41(1):41–48. 10.1007/s00281-018-0702-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Théate I, van Baren N, Pilotte L, Moulin P, Larrieu P, Renauld JC et al (2015) Extensive profiling of the expression of the indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 protein in normal and tumoral human tissues. Cancer Immunol Res 3(2):161–172. 10.1158/2326-6066.Cir-14-0137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jia D, Wang Q, Qi Y, Jiang Y, He J, Lin Y et al (2024) Microbial metabolite enhances immunotherapy efficacy by modulating T cell stemness in pan-cancer. Cell 187(7):1651–65.e21. 10.1016/j.cell.2024.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fong W, Li Q, Ji F, Liang W, Lau HCH, Kang X et al (2023) Lactobacillus gallinarum-derived metabolites boost anti-PD1 efficacy in colorectal cancer by inhibiting regulatory T cells through modulating IDO1/Kyn/AHR axis. Gut 72(12):2272–2285. 10.1136/gutjnl-2023-329543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Badawy AA (2022) Tryptophan metabolism and disposition in cancer biology and immunotherapy. Biosci Rep. 10.1042/bsr20221682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Renga G, D’Onofrio F, Pariano M, Galarini R, Barola C, Stincardini C et al (2023) Bridging of host-microbiota tryptophan partitioning by the serotonin pathway in fungal pneumonia. Nat Commun 14(1):5753. 10.1038/s41467-023-41536-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stockinger B, Shah K, Wincent E (2021) AHR in the intestinal microenvironment: safeguarding barrier function. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 18(8):559–570. 10.1038/s41575-021-00430-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Badawy AA (2022) Tryptophan metabolism and disposition in cancer biology and immunotherapy. Biosci Rep. 10.1042/bsr20221682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed in this study were oriented from a standardized clinical process and are included in this published article. Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the NCBI Short Read Archive with the Primary Bio-project accession code PRJNA991321 on the following link: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA991321. Metagenomic sequencing data of those receiving anti-PD-1 immunotherapy was deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive with the Primary Bio-project accession code CRA020393 on the following link: https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsub/submit/gsa/subCRA032908. Targeted tryptophan metabolome was also deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive with the Primary Bio-project accession code PRJCA032109 on the following link: https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/bioproject/browse/PRJCA032109. Additional supports for sequencings could also be directed to and will be fulfilled by Prof. Jian Zhang at zjfmmu19700227@163.com.