Abstract

The effect of ultrasound (US) on persulfate (PS) activation was investigated to determine whether acoustic cavitation can effectively induce PS activation for bisphenol A (BPA) degradation at 20, 28, and 300 kHz under various temperature conditions. The optimal liquid volume in the vessel was geometrically determined to be 400, 900, and 420 mL at 20, 28, and 300 kHz, respectively, using KI dosimetry and sonochemiluminescence image analysis. The pseudo-1st-order reaction kinetic constants in the only PS, only US, and US/PS processes at 20, 28, and 300 kHz were obtained under 5–10 ℃, 15–20 ℃, 25–30 ℃, 45–50 ℃, 55–60 ℃, and no temperature control conditions. No notable BPA degradation occurred at 5–10 ℃, 15–20 ℃, and 25–30 ℃ in the only PS processes for all frequencies. The highest sonochemical BPA degradation was obtained at 300 kHz, and much lower BPA degradation was observed at 45–50 ℃ and 55–60 ℃ for all frequencies in the only US processes. No notable enhancement of BPA degradation was observed at 5–10 ℃, 15–20 ℃, and 25–30 ℃ in the US/PS processes compared to the only US processes for all frequencies. At 20 kHz and temperatures between 55 and 60 ℃, the highest BPA degradation was obtained, with a synergistic effect of 171 %. However, the enhancement might be due to the instant or local temperature increase, and not due to acoustic cavitation. No notable PS activation by US irradiation was observed in the US/PS processes in this study. The profiles of the generated sulfate ion concentrations in the US/PS processes confirmed this. Some previous studies found high synergistic effects, whereas others have found low or no synergistic effects in US/PS processes.

Keywords: Ultrasound, Acoustic cavitation, Persulfate, Sulfate radicals, Bisphenol A, Advanced oxidation processes

1. Introduction

Acoustic cavitation, that uses highly concentrated energy in micron-sized bubbles, has been investigated over the past few decades [1], [2], [3]. Various sonochemical and sonophysical effects have been qualitatively and quantitatively analyzed in chemical and environmental engineering processes for advanced oxidation/reduction processes (AORPs) for the removal of recalcitrant emerging pollutants, hydrogen production processes using organic compounds, ultrasonic soil washing processes for the remediation of contaminated soils, and catalysts synthesis in homogeneous and heterogeneous systems [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]. Previous studies have focused on the optimization of frequency and input power under various solution conditions including temperature, pH, dissolved gases, inorganic ions, and additives in small-scale sonoreactors [1], [2], [13]. Recently, researchers have investigated the geometric effects of cavitational activity for the optimal design of large-scale sonoreactors [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21].

For the last two decades, sulfate radical-based water and wastewater treatment processes have been extensively studied using various activation methods as well as peroxymonosulfate (PMS) and peroxydisulfate, also known as persulfate (PS) [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28]. Sulfate radicals are more effective than hydroxyl radicals in terms of their oxidizing power, lifetime, pH range, and oxidation capacity in advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) [29], [30]. In addition, PS has higher capacity to generate sulfate radicals, lower O-O bond dissociation energy, and higher water solubility than PMS [24], [26], [28]. Among the various PS activation methods, ultraviolet (UV) activation has been reported to be one of the most effective and eco-friendly methods [31], [32].

Acoustic cavitation can lead to PS activation by the heat generated during cavitation bubbles’ collapse and by the cavitation-generated radicals [23], [33], [34], [35]. Most researchers have focused on optimizing the combination of ultrasound (US) and PS (US/PS) (Scheme 1) [33], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45]. However, some researchers have reported no synergistic effects in the US/PS processes [46], [47], [48]. In addition, ultrasonic PS activation might be difficult to distinguish from thermal PS activation because the attenuation of US in a liquid medium leads to the conversion of mechanical energy into heat energy [49], [50], [51]. It might not be possible to completely control the temperature in a liquid medium and inhibit thermal PS activation. Thus, it requires systematic research to further understand ultrasonic PS activation and to quantitatively analyze synergistic effects in US/PS processes.

Scheme 1.

Ultrasonic PS activation mechanisms (Acoustic cavitation and US attenuation).

To understand whether acoustic cavitation can effectively induce PS activation for BPA degradation at certain temperature conditions, only PS, only US, and US/PS processes were systematically investigated for 20, 28, and 300 kHz under various temperature conditions from 5 ℃ to 60 ℃. The geometric optimal conditions were determined for 20, 28, and 300 kHz. The pseudo-1st-order reaction rate constants and synergistic effects for BPA degradation were compared and analyzed. The generated sulfate ions in the US/PS were compared and analyzed to evaluate the degree of sulfate-radical reactions under different temperature conditions.

2. Experimental methods

Junsei Chemical Co. Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan) supplied potassium iodide (KI) and sodium sulfate (Na2SO4). Sigma-Aldrich Co. (USA) provided BPA (C15H16O2) and luminol (3-aminophthalhydrazide, C8H7N3O2). Samchun Pure Chemical Co., Ltd. (Korea) supplied sodium persulfate (Na2S2O8) and NaOH. All chemicals were used as received.

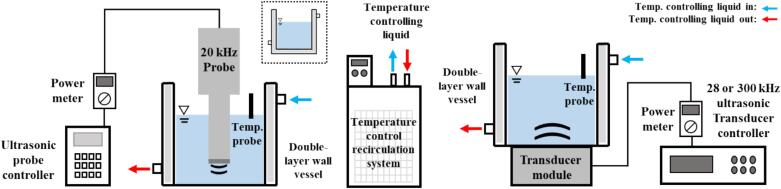

Three types of ultrasonic systems (20, 28, and 300 kHz) were used in this study, as shown in Fig. 1. All ultrasonic systems consisted of a circular glass vessel with a temperature-control double-layer wall, a recirculating chiller with a mixture of water and antifreeze (ethylene glycol), and an US generator [20 kHz probe-type sonicator with a replaceable tip (d: 13 mm) (VCX–750; Sonics & Materials Inc., USA), 28 kHz transducer module (Mirae Ultrasonic Tech., Bucheon, Korea), or 300 kHz transducer module (Mirae Ultrasonic Tech., Bucheon, Korea)]. Two double-layer wall vessels were used at 20 kHz and 28/300 kHz. The inner diameters of the glass vessels at 20 kHz and 28/300 kHz were 90 and 105 mm, respectively. The inner height of both vessels was 130 mm. A circular glass vessel without a double-layer bottom was mainly used for the 20 kHz systems in this study. A vessel with a double-layer wall and bottom was used to investigate the effect of the double-layer bottom on sonochemical oxidation activity, as shown in Fig. 1. The electrical input powers, measured using a power meter (HPM-300A, ADPower, Korea), were fixed at 80 ± 2.1 W for all frequency conditions. The ultrasonic power, also known as calorimetric power, was calculated using Equation (2):

| (1) |

where Pcal is the ultrasonic or calorimetric energy, dT/dt is the rate of increase in liquid temperature, Cp is the specific heat capacity of the liquid (4.184 J/(g·K) for water), and M is the mass of the liquid. All prepared solutions for ultrasound irradiation in this study were air-saturated to ensure consistent results [52], [53], [54], [55], [56].

Fig. 1.

Schematics of the 20 and 28/300 kHz ultrasonic systems and the temperature control recirculation system. A circular glass vessel without a double-layer bottom was mainly used for the 20 kHz systems. The image in the dotted line represents the vessel with a double-layer wall and bottom for comparison experiments.

Based on the end of the probe tip, the probe was placed at three positions: a top position (1 cm below the liquid surface), a middle position (midpoint between the liquid surface and the bottom), and a low position (1 cm above the bottom of the vessel). The positions were designated as “TOP”, “MID”, and “BOT”, respectively. The wavelength for the liquid height in the 28 and 300 kHz systems was obtained using the following equation:

| (2) |

where λ is the wavelength, c is the speed of sound in water (1,500 m/s), and f is the applied frequency. The wavelengths for 28 and 300 kHz were calculated as 54 and 5 mm, respectively.

To determine the geometrically optimal probe position and liquid volume in the systems, KI dosimetry (KI conc.: 10 g/L) for the quantification of sonochemical oxidation activity and the sonochemiluminescence (SCL) method (0.1 g/L luminol and 1 g/L NaOH) for the visualization of the sonochemically active zone were used under various probe positions and liquid volumes.

It has been reported that the threshold for thermal activation of PS is around 40 ℃ [34]. So, six different temperature conditions (5–10 ℃, 15–20 ℃, 25–30 ℃, 45–50 ℃, 55–60 ℃, and no temperature control (NTC)) were applied in the only PS, only US, and US/PS processes in this study. The temperature in the liquid phase was measured every 15 min, and no considerable change in the controlled temperature range was observed. Under various temperature conditions, the BPA degradation tests [BPA conc.: 1.0 mg/L (0.004 mM)] were conducted in the only PS, only US, and US/PS processes at the determined optimal geometric conditions (Optimal liquid volumes of 400, 900, and 420 mL were determined for 20, 28, and 300 kHz, respectively, and this will be discussed in Chapter 3.1). The initial Na2S2O8 concentrations were 45 and 90 mg/L (0.19 and 0.38 mM, respectively). The degradation of BPA was analyzed using the pseudo 1st-order reaction kinetics.

The concentration of I3- ions, sonochemically generated in the KI solution, was measured using a UV–vis spectrophotometer (Libra S60; Biochrom Ltd., UK). BPA concentration was measured using a HPLC system (1260 Infinity II LC; Agilent, USA). The concentration of sulfate ions, evidence for PS activation, was quantified using ion chromatography (IC) system (ICS-2100; Dionex, USA). SCL images were obtained using a digital camera (DSC-RX100M7; Sony Corp., Japan) in a completely dark room (ISO-6400, F 2.8). The exposure time was 10–30 sec.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Geometric optimization

To investigate the US/PS processes under optimal geometric conditions with the highest sonochemical activity at 20, 28, and 300 kHz, various geometric conditions including the probe positions and liquid volumes were tested using KI dosimetry, as shown in Fig. 2. It has been reported that slight changes in geometric conditions, including probe positions and liquid heights/volumes, can result in considerably different sonochemical activities under similar input power conditions. Geometric optimal conditions can lead to significant enhancement of sonochemical activity [14], [15], [17], [18], [57]. For 20 kHz probe-type sonicators, the sonochemical activity increased noticeably as the probe approached the bottom of the vessel because the strong reflections of the ultrasound at the vessel bottom induced the formation of large and bright active zone [14], [17], [58]. For bath-type sonoreactors equipped with a transducer module at the bottom, high sonochemical activity could be obtained when the liquid height/volume was high enough to form a stable standing wave field [16], [18], [59]. Note that different shapes and sizes of sonoreactors might lead to different optimal geometric conditions.

Fig. 2.

Sonochemical oxidation activities under different liquid volume conditions at 20, 28, and 300 kHz. The inset in Fig. 2(a) represents the sonochemical oxidation activities at 20 kHz obtained using a vessel with a double-layer wall and bottom.

In this study, the sonochemical oxidation activities were compared using the mass of I3- ions representing the total number of effective sonochemical oxidation reactions in KI solution, rather than using the concentration of sonochemically generated I3- ions because comparing the concentrations under volume-changing conditions was not appropriate [14], [17], [18], [20], [59]. As shown in Fig. 2(a), the highest sonochemical oxidation activity was obtained at a volume of 400 mL with the probe position of “BOT” for the 20 kHz probe systems with the double-layer wall. The enhancement of the sonochemical activity was attributed to the expansion of the sonochemical active zone, induced by the strong reflection of US at the bottom and at the liquid surface as shown in the SCL images in Fig. 3(a) [17]. The luminol molecules react with sonochemically generated oxidizing radicals such as OH radicals and emit blue/white light. The degree of radical oxidation reactions in sonochemical processes can be qualitatively considered using the area and intensity of light in the SCL images [54]. Son et al. reported that the enhancement of sonochemical activity could be achieved by optimizing the probe position, input power, and liquid height/volume in 20 kHz probe-type sonoreactors [17]. As shown in Fig. 2(a), relatively low and similar activities were obtained for all volume and probe position conditions using the vessel with a double-layer wall and bottom. The substantial decrease in the activity might be due to a weak US reflection at the bottom, induced by US transmission/absorption in the bottom part consisting of two glass layers and liquid. Son et al. reported that sonochemical activity decreased significantly as the bottom plate’s thickness beneath the vessel increased. It might be attributed to the difference in the degree of the ultrasound reflection at the boundary between the liquid and the solid bottom layer [17]. The SCL images obtained using the vessel with the double-layer wall and bottom at 20 kHz are shown in Fig. 1S. The observed SCL intensities were relatively low.

Fig. 3.

SCL images under different liquid volumes and probe positions at 20 kHz and under different liquid height/volume conditions at 28 and 300 kHz.

As shown in Fig. 2(b), the optimal liquid volumes of 900 mL (2λ: 108 mm) and 420 mL (10λ: 50 mm) were determined for the 28 and 300 kHz systems, respectively. Although larger liquid volumes could be determined as the optimal condition for the 28 kHz system, a volume of 900 mL was used in this study considering the liquid volumes determined for 20 kHz in this study and the liquid volumes used in previous US/PS studies (200–500 mL) [44], [47], [48], [60]. In previous researches, the highest sonochemical activities were obtained at 4–5λ for 35 and 36 kHz [59], [61], [62]. In addition, the optimal liquid height in bath-type sonoreactors was reported to be in the range of 5λ–15λ for 291 and 448 kHz [18], [63]. The optimal liquid volumes were not found at small volumes, with relatively high-power densities (the input power divided by the liquid volume), but rather at larger volume ranges, where the power densities decreased considerably. This might be attributed to the stable distribution of US energy and the stable formation of the standing wave field adjacent to the liquid surface.

In addition, US, especially at low frequencies (20–40 kHz), from the bottom of small-liquid-height/volume sonoreactors can induce ripples at the liquid surface. This leads to a substantial decrease in the stability of the liquid surface and a stable standing wave field cannot form [16], [54], [59]. As the liquid height/volume increases to optimal conditions, stable reflection of US can occur at the liquid surface and a strong standing wave field can be formed with high sonochemical activity. In the SCL images in Fig. 3(b), clear and strong standing wave fields are observed at the determined optimal volume conditions. High-frequency US is relatively weak compared to low-frequency US and induces fewer ripples at the liquid surface [15], [18], [59]. This leads to the formation of stable standing wave field for all liquid height/volume conditions as shown in Fig. 3(c).

3.2. PS, US, and US/PS processes

Ultrasonic PS activation can be induced by acoustic cavitation (heat energy from cavitation bubbles’ collapse and cavitation-generated radicals) and by US attenuation in bulk liquid phase (the conversion of mechanical energy into heat energy) [23], [33], [34], [35], [49], [50], [51]. To understand the PS activation mechanism in US/PS processes at certain temperature conditions, only PS, only US, and US/PS processes were investigated under the following temperature conditions: 5–10 ℃, 15–20 ℃, 25–30 ℃, 45–50 ℃, 55–60 ℃, and NTC at the optimal geometric conditions with the highest cavitational activity (400 mL for 20 kHz, 900 mL for 28 kHz, and 420 mL for 300 kHz). Under a fixed input electrical power (80 ± 2.1 W), the calorimetric powers at 20, 28, and 300 kHz were 33.6 ± 4.3, 33.3 ± 6.2, and 37.6 ± 1.4 W, respectively. The degradation of BPA was quantified and the pseudo-1st-order reaction constants were compared, as shown in Fig. 4 [41], [47], [60]. The reaction constants, their coefficients of determination (R2 values), and synergistic effects (only for the cases of PS 90 mg/L) are summarized in Table S1. For the conditions of NTC, the initial temperature was 18 ± 1.5 ℃ and the final temperatures after 120 min of US irradiation were 66, 40, and 47 ℃ for 20, 28, and 300 kHz, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Pseudo-1st-order reaction rate constants for BPA degradation in the US, US/PS, and PS processes under various temperature conditions at 20, 28, and 300 kHz. The final temperatures for NTC were 66 ℃, 40 ℃, and 47 ℃ at 20, 28, and 300 kHz, respectively.

In only US processes, the sonochemical degradation of BPA occurs mainly using cavitationally generated oxidizing radicals such as OH radicals adjacent to the cavitation bubbles. This is because of BPA’s low volatility [41]. This process can be considerably affected by the applied frequency and liquid temperature [1]. It has been reported that the use of US in the high frequency range (300–500 kHz) is more effective in generating oxidizing radicals than the use of US in the low frequency range (20–40 kHz) in small lab-scale sonochemical reactors [15]. Even though higher frequency US induces less intense cavitation events with smaller bubbles, it can generate more active cavitation bubbles and radicals at more rapid rates, resulting in higher pollutant removal efficiencies (RE) [1], [49], [64]. In this study, the highest degradation of BPA was observed at 300 kHz, and the lowest removal was observed at 28 kHz (the reaction rates at 28 kHz were approximately 9–15 % of those at 300 kHz at temperatures below 30 ℃). The 20 kHz US, the lowest frequency in this study, induced relatively high BPA removal because the 20 kHz probe-type sonicator could result in high cavitational activity and violent mixing in small volume conditions [17], [57]. As mentioned above, the optimal liquid volume for each frequency was determined based on the mass of sonochemical reaction products (I3− in this study), and the reaction kinetic constants were obtained based on the concentration of sonochemical reaction products. Therefore, a comparison of the reaction constants at the applied frequencies may not be appropriate for different liquid volumes [15].

For all frequencies of 20, 28, and 300 kHz, the reaction kinetic constants in the US processes remained relatively constant and then decreased considerably at 45–50 ℃ and 55–60 ℃ as the liquid temperature increased (The highest reaction constants were obtained at 25–30 ℃ for all frequencies.). For the NTC cases, the reaction constants were similar to or lower than those at 15–20 ℃ and 25–30 ℃ depending on the final liquid temperature. When US is irradiated, the temperature increase in the bulk liquid phase can reduce the number of dissolved gas molecules, acting as cavitation nuclei. The increase in temperature elevates vapor inside the cavitation bubbles, resulting in less intensive cavitational activity by inducing the cushioning effect [1], [65], [66], [67], [68]. Therefore, increasing the liquid temperature above a certain value (30–40 ℃ in this study) was not desirable for the sonochemical degradation of BPA.

In the only PS processes, designated as “Heat + PS 90 mg/L” conditions in Fig. 4, no significant BPA degradation was obtained at low and moderate temperature conditions (5–10 ℃, 15–20 ℃, and 25–30 ℃). However, BPA degradation by thermal activation of PS was observed at 45–50 ℃, and the third highest reaction constant (as high as the second highest constant) of all cases was observed at 55–60 ℃. In several recent review papers regarding the thermal activation of PS, it has been generally reported that only PS at room temperature (or ambient temperature) cannot generate reactive oxidizing species, and meaningful pollutant degradation by thermal activation of PS cannot be achieved at temperatures below 40 ℃ because high energy is required to break the O-O bond in PS [34], [69], [70]. In contrast, PMS can be activated and degrade aqueous pollutants at room temperature [69]. It has been suggested that temperature optimization is required for thermal activation of PS because of the ineffective consumption of generated sulfated radicals at considerably high temperature conditions and concerns of considerable energy consumption [34], [70], [71].

In US/PS processes, it has been reported that the role of US in the activation of PS can be divided into two categories: 1) acoustic-cavitation-induced activation resulting from the thermal effects of cavitation bubble collapse and radical chain reactions [23], [33], [34] and 2) US-heating-induced activation resulting from the conversion of mechanical energy into heat energy, which is the basic concept for the measurement of calorimetric/ultrasonic energy in sonochemistry [49], [50], [51]. The second role of US is minor when the liquid temperature remains constant below 30 ℃ during US irradiation using direct/indirect cooling systems. However, it is not easy to completely prevent instant or local temperature increase in liquid under continuous US irradiation in spite of small liquid volumes.

As shown in Fig. 4, no notable enhancement by the addition of PS was observed at 5–10 ℃, 15–20 ℃, and 25–30 ℃ for all frequency conditions in the US/PS processes. This resulted in almost similar reaction constants for only US, US/PS (45 mg/L), and US/PS (90 mg/L) processes. As shown in the results of the only PS processes at 55–60 ℃, the applied PS concentrations in this study were sufficient to achieve high BPA removal once PS activation occurred properly. In addition, the degree of acoustic cavitation was sufficient to obtain high BPA removal in the only US processes. In this study, the pseudo-1st-order reaction rate constants for BPA degradation in the only US processes (20, 28, and 300 kHz) at low and moderate temperature conditions ranged from 0.0034 to 0.043 min−1. In previous studies, the average value of pseudo-1st-order reaction rate constants for BPA degradation at 20–25 ℃ for 200–404 kHz was 0.045 ± 0.037 min−1 [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77]. Consequently, it was found that US irradiation at various frequencies and the resulting acoustic cavitation phenomena could not induce observable PS activation for BPA removal at low and moderate temperatures in this study.

It is well known that the generation of sulfate ions in various PS processes is a good indicator of whether and to what extent PS activation occurs. PS activation can generate highly reactive sulfate radicals, which are converted to sulfate ions by losing their oxidizing power. In this study, sulfate ion concentration was used as an indicator of the degree of PS activation for the degradation of BPA under various temperature conditions [22], [78]. Note that free radical detection methods need to be conducted to further understand mechanisms of thermal and ultrasonic PS activation [45]. Fig. 5 shows the sulfate ion concentrations in the US/PS processes (PS: 45 and 90 mg/L) under various temperatures for 20, 28, and 300 kHz. It should be noted that the reaction time required for 90 % BPA removal ranged from 21 min to 84 min, 42 min to 196 min, and 44 min to 80 min for 20, 28, and 300 kHz, respectively, in the US/PS processes (PS 45 and 90 mg/L) at 45–50 ℃ and 55–60 ℃. Therefore, PS could be consumed for BPA and byproduct degradation from early or late reaction times and the concentrations of the sulfate ions might not show significant correlations with the reaction rate constants for BPA degradation.

Fig. 5.

Concentrations of sulfate ions generated by PS activation in the US/PS processes for BPA degradation under various temperature conditions at 20, 28, and 300 kHz. The final temperatures for NTC were 66 ℃, 40 ℃, and 47 ℃ for 20, 28, and 300 kHz, respectively.

At 20 kHz, notable levels of sulfate ion concentrations were observed at 45–50 ℃, 55–60 ℃, and NTC. Higher BPA removals were observed in the US/PS processes compared to those in the only US processes (The highest concentrations of the sulfate ions were obtained at 55–60 ℃ where the highest BPA removal, much higher than those in the only US process, were obtained for the PS concentrations of 45 and 90 mg.). No notable concentrations of sulfate ions at 5–10 ℃, 15–20 ℃, and 25–30 ℃ indicated that no notable PS activation occurred, and most of the BPA removal was induced by sonochemical reactions rather than sulfate radical reactions.

At 300 kHz, no noticeable sulfate ion concentrations were observed at all temperature conditions, except at 55–60 ℃. This indicated that BPA degradation at 5–10 ℃, 15–20 ℃, 25–30 ℃, 45–50 ℃, and NTC may be induced mainly by sonochemical oxidation reactions. At 55–60 ℃, no notable sonochemical reactions for BPA removal might occur considering the reaction rates in the PS and US/PS processes (PS 90 mg/L: kPS = 53.9 × 10-3 min−1; kUS/PS = 52.7 × 10-3 min−1). This may be due to the low cavitational activity under the high temperature conditions discussed above. Although to a lesser degree, similar trends of PS activation were observed at 45–50 ℃, 55–60 ℃, and NTC for 28 kHz, and no notable contribution of the sonochemical reactions was observed at 55–60 ℃ (PS 90 mg/L: kPS = 53.9 × 10-3 min−1; kUS/PS = 55.5 × 10-3 min−1).

In addition, at a frequency of 20 kHz, PS activation at 45–50 ℃ and NTC might be induced not by cavitational effects but by uncontrolled instant or local temperature increase, considering the results of 28 and 300 kHz above. The highest reaction rate constant, obtained at 55–60 ℃ for 20 kHz and approximately twice as large as the second highest constant for all cases, might be due to the formation of instant or local hot-temperature zones higher than 55–60 ℃. Relatively moderate synergistic effects of 149 % and 171 % were obtained at 45–50 ℃ and 55–60 ℃, respectively, at 20 kHz as shown in Table S1. In this study, it seemed that the external cooling in the 300 kHz sonoreactor worked successfully in preventing the instant or local temperature increase considering the low and nearly identical concentrations of sulfate ions at 5–10 ℃, 15–20 ℃, 25–30 ℃, and 45–50 ℃ as shown in Fig. 5(e) and 5(f). However, it should be noted that the instant or local temperature increase might vary considerably depending not only on the applied frequency but also on the geometric conditions and cooling systems.

In this study, we obtained the following findings: 1) lower BPA degradation at 45–50 ℃, 55–60 ℃, and NTC than at 5–10 ℃, 15–20 ℃, and 25–30 ℃ in the only US processes; 2) similar BPA degradations in the US/PS and the only PS processes at 55–60 ℃ for 28 and 300 kHz; 3) much higher BPA degradation in the only PS processes at 55–60 ℃ (thermal PS activation) than in the US/PS processes at 5–10 ℃, 15–20 ℃, and 25–30 ℃. These findings indicated that US irradiation at various frequencies and the resulting acoustic cavitation phenomena could not induce observable PS activation for BPA removal at low, moderate and high temperatures (except for the 20 kHz’s cases at 45–50 ℃ and 55–60 ℃). In addition, thermal PS activation seemed more effective than ultrasonic PS activation. Thus, we thought that the high synergistic effects for 20 kHz at high temperature conditions might be caused by uncontrolled instant or local temperature increase, under the assumption that other PS activation mechanisms were not identified in this study.

4. Conclusion

In this study, US/PS processes were investigated to determine whether acoustic cavitation could induce PS activation and BPA degradation at 20, 28, and 300 kHz under various temperature conditions of 5–60 ℃. Under the optimal geometric conditions including the probe position at 20 kHz and the liquid volumes at 20, 28, and 300 kHz, the pseudo-1st-order reaction constants for BPA degradation in the only PS, only US, and US/PS processes were obtained, and synergistic effects were analyzed. It was found that no notable PS activation or synergistic effects occurred in the US/PS processes for all frequencies below 30 ℃. Although relatively moderate synergistic effects of 149 % and 171 % were obtained at 45–50 ℃ and 55–60 ℃, respectively, at 20 kHz, the enhancement might be due to the instant or local temperature increase induced by the strong 20 kHz US irradiation and incomplete system cooling because higher temperature conditions considerably reduce cavitational activity. To further understand ultrasonic activation of PS, more experimental data should be accumulated using novel methods such as EPR under various conditions. In addition, comprehensive research on developing various scale-up strategies is required for large-scale US/PS applications.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Bokyung Jun: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Jongbok Choi: Writing – original draft, Validation, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Younggyu Son: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea [RS-2024-00350023] and the Korea Ministry of Environment (MOE) as part of the “Subsurface Environment Management (SEM)” Program [RS-2021-KE001466].

Footnotes

This article is part of a special issue entitled: ‘Power Ultrasound & Cavitation’ published in Ultrasonics Sonochemistry.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2025.107281.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Wood R.J., Lee J., Bussemaker M.J. A parametric review of sonochemistry: control and augmentation of sonochemical activity in aqueous solutions. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017;38:351–370. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Y. Son, Advanced Oxidation Processes Using Ultrasound Technology for Water and Wastewater Treatment, in: M. Ashokkumar (Ed.), Handbook of Ultrasonics and Sonochemistry, Springer Singapore, Singapore, 2016, pp. 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-470-2_53-1.

- 3.Meroni D., Djellabi R., Ashokkumar M., Bianchi C.L., Boffito D.C. Sonoprocessing: from concepts to large-scale reactors. Chem. Rev. 2022;122(3):3219–3258. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Na I., Kim T., Qiu P., Son Y. Machine learning model to predict rate constants for sonochemical degradation of organic pollutants. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2024;110 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2024.107032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi J., Yoon S., Son Y. Effects of alcohols and dissolved gases on sonochemical generation of hydrogen in a 300 kHz sonoreactor. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023;101 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2023.106660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho S.H., Jeon H.J., Son Y., Lee S.E., Kim T.O. Water splitting over an ultrasonically synthesized NiFe/MoO3@CFP electrocatalyst. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 2023;48(67):26032–26045. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2023.03.236. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee D., Son Y. Ultrasound-assisted soil washing processes using organic solvents for the remediation of PCBs-contaminated soils. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Son Y., Lee D., Lee W., Park J., Hyoung Lee W., Ashokkumar M. Cavitational activity in heterogeneous systems containing fine particles. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2019;58 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2019.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.B. Park, Y. Son, Ultrasonic and mechanical soil washing processes for the removal of heavy metals from soils, Ultrason. Sonochem. 35, Part B (2017) 640-645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Neppolian B., Bruno A., Bianchi C.L., Ashokkumar M. Graphene oxide based Pt–TiO2 photocatalyst: ultrasound assisted synthesis, characterization and catalytic efficiency. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2012;19(1):9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2011.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dehane A., Nemdili L., Merouani S., Ashokkumar M. Critical analysis of hydrogen production by aqueous methanol sonolysis. Top. Curr. Chem. 2023;381(2):9. doi: 10.1007/s41061-022-00418-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yusof N.S.M., Babgi B., Alghamdi Y., Aksu M., Madhavan J., Ashokkumar M. Physical and chemical effects of acoustic cavitation in selected ultrasonic cleaning applications. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2016;29:568–576. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2015.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rooze J., Rebrov E.V., Schouten J.C., Keurentjes J.T.F. Dissolved gas and ultrasonic cavitation – a review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2013;20(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Na I., Son Y. Sonochemical oxidation activity in 20-kHz probe-type sonicator systems: the effects of probe positions and vessel sizes. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2024;108 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2024.106959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee S., Son Y. Effects of gas saturation and sparging on sonochemical oxidation activity under different liquid level and volume conditions in 300-kHz sonoreactors: Zeroth- and first-order reaction comparison using KI dosimetry and BPA degradation. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023;98 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2023.106521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee D., Kang J., Son Y. Effect of violent mixing on sonochemical oxidation activity under various geometric conditions in 28-kHz sonoreactor. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023;101 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2023.106659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Son Y., No Y., Kim J. Geometric and operational optimization of 20-kHz probe-type sonoreactor for enhancing sonochemical activity. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020;65 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Son Y. Simple design strategy for bath-type high-frequency sonoreactors. Chem. Eng. J. 2017;328:654–664. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2017.07.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khuyen Viet Bao T., Yoshiyuki A., Shinobu K. Influence of liquid height on mechanical and chemical effects in 20 kHz sonication. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2013;52(7S) doi: 10.7567/JJAP.52.07HE07. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asakura Y., Nishida T., Matsuoka T., Koda S. Effects of ultrasonic frequency and liquid height on sonochemical efficiency of large-scale sonochemical reactors. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2008;15(3):244–250. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Son Y., Lim M., Khim J. Investigation of acoustic cavitation energy in a large-scale sonoreactor. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2009;16(4):552–556. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kang J., Choi J., Lee D., Son Y. UV/persulfate processes for the removal of total organic carbon from coagulation-treated industrial wastewaters. Chemosphere. 2024;346 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.140609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Z., Ren X., Duan X., Sarmah A.K., Zhao X. Remediation of environmentally persistent organic pollutants (POPs) by persulfates oxidation system (PS): a review. Sci. Total Environ. 2023;863 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.160818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee J., von Gunten U., Kim J.H. Persulfate-based advanced oxidation: critical assessment of opportunities and roadblocks. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020;54(6):3064–3081. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.9b07082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang J., Wang S. Activation of persulfate (PS) and peroxymonosulfate (PMS) and application for the degradation of emerging contaminants. Chem. Eng. J. 2018;334:1502–1517. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2017.11.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wacławek S., Lutze H.V., Grübel K., Padil V.V.T., Černík M., Dionysiou D.D. Chemistry of persulfates in water and wastewater treatment: a review. Chem. Eng. J. 2017;330:44–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2017.07.132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin Q., Deng Y. Is sulfate radical a ROS? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021;55(22):15010–15012. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.1c06651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giannakis S., Lin K.Y.A., Ghanbari F. A review of the recent advances on the treatment of industrial wastewaters by sulfate radical-based advanced oxidation processes (SR-AOPs) Chem. Eng. J. 2021;406 doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2020.127083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xia X., Zhu F., Li J., Yang H., Wei L., Li Q., Jiang J., Zhang G., Zhao Q. A review study on sulfate-radical-based advanced oxidation processes for domestic/industrial wastewater treatment: degradation, efficiency, and mechanism. Front. Chem. 2020;8 doi: 10.3389/fchem.2020.592056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang X., Chen Z., He Y., Yi X., Zhang C., Zhou Q., Xiang X., Gao Y., Huang M. Activation of persulfate-based advanced oxidation processes by 1T-MoS2 for the degradation of imidacloprid: performance and mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2023;451 doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2022.138575. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang Y., Ji Y., Yang P., Wang L., Lu J., Ferronato C., Chovelon J.M. UV-activated persulfate oxidation of the insensitive munitions compound 2,4-dinitroanisole in water: Kinetics, products, and influence of natural photoinducers. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2018;360:188–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2018.04.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang J., Zhu M., Dionysiou D.D. What is the role of light in persulfate-based advanced oxidation for water treatment? Water Res. 2021;189 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.116627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang L., Xue J., He L., Wu L., Ma Y., Chen H., Li H., Peng P., Zhang Z. Review on ultrasound assisted persulfate degradation of organic contaminants in wastewater: influences, mechanisms and prospective. Chem. Eng. J. 2019;378 doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2019.122146. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang B., Wang Y. A comprehensive review on persulfate activation treatment of wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;831 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.154906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kathuria T., Mehta A., Sharma S., Kumar S. Review on ultrasound-enhanced activation of persulfate/peroxymonosulfate in hybrid advanced oxidation technologies. Chem. Eng. Commun. 2024;211(10):1645–1669. doi: 10.1080/00986445.2024.2358372. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neppolian B., Doronila A., Ashokkumar M. Sonochemical oxidation of arsenic(III) to arsenic(V) using potassium peroxydisulfate as an oxidizing agent. Water Res. 2010;44(12):3687–3695. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neppolian B., Jung H., Choi H., Lee J.H., Kang J.-W. Sonolytic degradation of methyl tert-butyl ether: the role of coupled fenton process and persulphate ion. Water Res. 2002;36(19):4699–4708. doi: 10.1016/S0043-1354(02)00211-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li B., Zhu J. Simultaneous degradation of 1,1,1-trichloroethane and solvent stabilizer 1,4-dioxane by a sono-activated persulfate process. Chem. Eng. J. 2016;284:750–763. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2015.08.153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li B., Li L., Lin K., Zhang W., Lu S., Luo Q. Removal of 1,1,1-trichloroethane from aqueous solution by a sono-activated persulfate process. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2013;20(3):855–863. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2012.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hao F., Guo W., Wang A., Leng Y., Li H. Intensification of sonochemical degradation of ammonium perfluorooctanoate by persulfate oxidant. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2014;21(2):554–558. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2013.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Darsinou B., Frontistis Z., Antonopoulou M., Konstantinou I., Mantzavinos D. Sono-activated persulfate oxidation of bisphenol A: Kinetics, pathways and the controversial role of temperature. Chem. Eng. J. 2015;280:623–633. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2015.06.061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang S., Zhou N. Removal of carbamazepine from aqueous solution using sono-activated persulfate process. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2016;29:156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2015.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Monteagudo J.M., El-taliawy H., Durán A., Caro G., Bester K. Sono-activated persulfate oxidation of diclofenac: degradation, kinetics, pathway and contribution of the different radicals involved. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018;357:457–465. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kermani M., Farzadkia M., Morovati M., Taghavi M., Fallahizadeh S., Khaksefidi R., Norzaee S. Degradation of furfural in aqueous solution using activated persulfate and peroxymonosulfate by ultrasound irradiation. J. Environ. Manage. 2020;266 doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wei Z., Villamena F.A., Weavers L.K. Kinetics and mechanism of ultrasonic activation of persulfate: An in situ EPR spin trapping study. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017;51(6):3410–3417. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b05392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nasseri S., Mahvi A.H., Seyedsalehi M., Yaghmaeian K., Nabizadeh R., Alimohammadi M., Safari G.H. Degradation kinetics of tetracycline in aqueous solutions using peroxydisulfate activated by ultrasound irradiation: effect of radical scavenger and water matrix. J. Mole. Liq. 2017;241:704–714. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2017.05.137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Diao Z.H., Dong F.X., Yan L., Chen Z.L., Qian W., Kong L.J., Zhang Z.W., Zhang T., Tao X.Q., Du J.J., Jiang D., Chu W. Synergistic oxidation of bisphenol A in a heterogeneous ultrasound-enhanced sludge biochar catalyst/persulfate process: Reactivity and mechanism. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020;384 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nejumal K.K., Satayev M.I., Rayaroth M.P., Arun P., Dineep D., Aravind U.K., Azimov A.M., Aravindakumar C.T. Degradation studies of bisphenol S by ultrasound activated persulfate in aqueous medium. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023;101 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2023.106700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Son Y., Lim M., Khim J., Kim L.H., Ashokkumar M. Comparison of calorimetric energy and cavitation energy for the removal of bisphenol-A: the effects of frequency and liquid height. Chem. Eng. J. 2012;183:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2011.12.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koda S., Kimura T., Kondo T., Mitome H. A standard method to calibrate sonochemical efficiency of an individual reaction system. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2003;10(3):149–156. doi: 10.1016/S1350-4177(03)00084-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mason T.J., Lorimer J.P. Applied sonochemistry-The uses of power ultrasound in chemistry and processing, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH. Weinheim. 2002 doi: 10.1002/352760054X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Son Y., Choi J. Effects of gas saturation and sparging on sonochemical oxidation activity in open and closed systems, part II: NO2−/NO3− generation and a brief critical review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023;92 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2022.106250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Choi J., Son Y. Quantification of sonochemical and sonophysical effects in a 20 kHz probe-type sonoreactor: Enhancing sonophysical effects in heterogeneous systems with milli-sized particles. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022;82 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Son Y., Seo J. Effects of gas saturation and sparging on sonochemical oxidation activity in open and closed systems, Part I: H2O2 generation. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022;90 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2022.106214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Choi J., Lee H., Son Y. Effects of gas sparging and mechanical mixing on sonochemical oxidation activity. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;70 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee D., Na I., Son Y. Effect of liquid recirculation flow on sonochemical oxidation activity in a 28 kHz sonoreactor. Chemosphere. 2022;286 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.131780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Choi J., Son Y. Effect of dissolved gases on sonochemical oxidation in a 20 kHz probe system: continuous monitoring of dissolved oxygen concentration and sonochemical oxidation activity. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023;97 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2023.106452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.No Y., Son Y. Effects of probe position of 20 kHz sonicator on sonochemical oxidation activity. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2019;58(SG) doi: 10.7567/1347-4065/ab0adb. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Son Y., Lim M., Ashokkumar M., Khim J. Geometric optimization of sonoreactors for the enhancement of sonochemical activity. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2011;115(10):4096–4103. doi: 10.1021/jp110319y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sun S., Ren Y., Guo F., Zhou Y., Cui M., Ma J., Han Z., Khim J. Comparison of effects of multiple oxidants with an ultrasonic system under unified system conditions for bisphenol A degradation. Chemosphere. 2023;329 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.138526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Choi J., Khim J., Neppolian B., Son Y. Enhancement of sonochemical oxidation reactions using air sparging in a 36 kHz sonoreactor. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2019;51:412–418. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2018.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Son Y., Lim M., Song J., Khim J. Liquid height effect on sonochemical reactions in a 35 kHz sonoreactor. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2009;48(7) doi: 10.1143/JJAP.48.07GM16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lim M., Ashokkumar M., Son Y. The effects of liquid height/volume, initial concentration of reactant and acoustic power on sonochemical oxidation. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2014;21(6):1988–1993. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Beckett M.A., Hua I. Impact of ultrasonic frequency on aqueous sonoluminescence and sonochemistry. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2001;105:3796–3802. doi: 10.1021/jp003226x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Merouani S., Hamdaoui O., Saoudi F., Chiha M. Influence of experimental parameters on sonochemistry dosimetries: KI oxidation, Fricke reaction and H2O2 production. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010;178(1):1007–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jiang Y., Petrier C., Waite T.D. Sonolysis of 4-chlorophenol in aqueous solution: effects of substrate concentration, aqueous temperature and ultrasonic frequency. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2006;13(5):415–422. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Entezari M.H., Kruus P. Effect of frequency on sonochemical reactions II. Temperature and intensity effects, Ultrason. Sonochem. 1996;3(1):19–24. doi: 10.1016/1350-4177(95)00037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fagan W.P., Zhao J., Villamena F.A., Zweier J.L., Weavers L.K. Synergistic, aqueous PAH degradation by ultrasonically-activated persulfate depends on bulk temperature and physicochemical parameters. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020;67 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li N., Wu S., Dai H., Cheng Z., Peng W., Yan B., Chen G., Wang S., Duan X. Thermal activation of persulfates for organic wastewater purification: heating modes, mechanism and influencing factors. Chem. Eng. J. 2022;450 doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2022.137976. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Matzek L.W., Carter K.E. Activated persulfate for organic chemical degradation: a review. Chemosphere. 2016;151:178–188. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Huang K.C., Zhao Z., Hoag G.E., Dahmani A., Block P.A. Degradation of volatile organic compounds with thermally activated persulfate oxidation. Chemosphere. 2005;61(4):551–560. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pétrier C., Torres-Palma R., Combet E., Sarantakos G., Baup S., Pulgarin C. Enhanced sonochemical degradation of bisphenol-A by bicarbonate ions. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2010;17(1):111–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Inoue M., Masuda Y., Okada F., Sakurai A., Takahashi I., Sakakibara M. Degradation of bisphenol A using sonochemical reactions. Water Res. 2008;42(6):1379–1386. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Meng L., Gan L., Gong H., Su J., Wang P., Li W., Chu W., Xu L. Efficient degradation of bisphenol a using high-frequency ultrasound: analysis of influencing factors and mechanistic investigation. J. Clean. Prod. 2019;232:1195–1203. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.06.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lim M., Son Y., Khim J. The effects of hydrogen peroxide on the sonochemical degradation of phenol and bisphenol A. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2014;21(6):1976–1981. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2014.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gültekin I., Ince N.H. Ultrasonic destruction of bisphenol-A: the operating parameters. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2008;15(4):524–529. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Torres R.A., Nieto J.I., Combet E., Pétrier C., Pulgarin C. Influence of TiO2 concentration on the synergistic effect between photocatalysis and high-frequency ultrasound for organic pollutant mineralization in water. Appl. Catal. B. 2008;80(1–2):168–175. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2007.11.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gao Y., Gao N., Deng Y., Yang Y., Ma Y. Ultraviolet (UV) light-activated persulfate oxidation of sulfamethazine in water. Chem. Eng. J. 2012;195–196:248–253. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2012.04.084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.