Abstract

Advances in medical care have significantly extended the lifespan of patients with congenital heart disease (CHD), allowing most to survive into adulthood. However, they continue to face significant cardiovascular morbidity, particularly atrial arrhythmias (AA), heart failure, and thromboembolic (TE) events. TE events in adult CHD patients arise from various factors, including AA, intracardiac repairs, cyanotic CHD, Fontan palliation, pregnancy, and mechanical heart valves (MHV). As randomized clinical trials are lacking, most current guidelines rely on observational data and expert opinions, leading to inherent variability. While vitamin K antagonists are the only option for patients with MHV and significant mitral stenosis, direct oral anticoagulants appear to be a reasonable choice for other indications. In the presence of AA, complex conditions alone may justify anticoagulation, whereas thromboembolic and haemorrhagic risks should be evaluated individually for simpler lesions. This review summarizes the available evidence and makes relevant recommendations regarding thromboprophylaxis in ACHD patients, focusing on indications, risk scores, and therapies.

Keywords: Adult congenital heart disease, Thromboprophylaxis, Thromboembolic events, Management

1. Background

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is one of the most common birth defects, and recent estimates indicate that there are over 1 million patients with CHD in Europe [1]. Due to advances in cardiac surgery and cardiology, nearly two-thirds of the total CHD population now reach adulthood [2]. Even though there has been a significant improvement in long-term prognosis for most congenital defects, these patients still suffer from considerable cardiovascular morbidity and mortality during their lives [3].

In this context, thromboembolic (TE) events such as stroke, systemic embolism, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism, along with atrial arrhythmias and heart failure, are among the most common complications [[4], [5], [6]]. Notably, adult congenital heart disease (ACHD) patients aged 55 years or younger experience stroke rates 9 to 12 times higher than the general population [7]. In contrast, the incidence of venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism varies widely, ranging from 3 % to 40 %, depending on the cardiac defect and study design [3].

These patients are at a higher risk of TE events for a multitude of reasons, including high incidence rates of atrial arrhythmias, residual valvular heart disease, residual intracardiac shunts, the presence of cyanosis, myocardial scarring and ventricular dysfunction, and the use of prosthetic materials for intracardiac repair [3,4,[8], [9], [10]]. Therefore, the proper use of oral anticoagulant medications to avert thromboembolism is crucial for this at-risk patient population [[11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16]].

Nevertheless, due to the specificities and diversity of ACHD patients, assessing risk and managing TE events remains troublesome in this group, and several issues are still unresolved. Additionally, current guidelines are largely based on expert opinion, given the lack of randomized controlled trials in this population [8,[17], [18], [19]]. This has led to significant variability in recommendations across different documents, which further complicates decision-making for individual patients [8,[17], [18], [19]]. In this narrative review, we aim to synthesize existing evidence on thromboprophylaxis in ACHD patients, covering indications, risk scores, and therapies. Furthermore, we propose a standardized approach based on the latest available guidelines, highlighting challenges and needs in specific subgroups.

2. Methods

PubMed and Scopus electronic database were scanned up to August 2024. We included the following listed keywords: "anticoagulation" or “DOAC” (direct oral anticoagulants) or "NOAC" (novel oral anticoagulants) or “VKA” (vitamin K antagonists) and "congenital heart disease", “guidelines”, “ACHD” and “thromboembolism”.

Both qualitative and quantitative studies were included to explore various aspects of congenital heart disease, thromboembolism, and anticoagulation. Only English-language manuscripts related to human research were considered. Most of the recommendations are based on the guidelines of the American Heart Association and the European Society of Cardiology [8,[17], [18], [19]]. Following this selection process, each article was analysed for relevance and quality of evidence before being included in this review.

3. Pathophysiology

3.1. General mechanisms

ACHD patients are at an increased risk of thromboembolic (TE) events compared with the general population due to a variety of factors (Fig. 1) [3,5].

Fig. 1.

Thromboembolic risk Continuum in adults with congenital heart disease.

∗ The cumulative risk factors are arranged in increasing order for graphical purposes, which does not imply that they are necessarily more significant than others.

ACHD: adult congenital heart disease; CHD: congenital heart disease; PH: pulmonary hypertension; RV: right ventricle; TE: thromboembolic; UVH: univentricular heart.

One key risk factor is the high prevalence of atrial arrhythmias (AA), particularly atrial fibrillation (AF), atrial flutter (AFL), and intra-atrial re-entrant tachycardia, which occur three times more frequently in ACHD patients [20]. It is estimated that 15 % of ACHD patients have AA, and it is expected that 50 % of 20-year-old patients will develop AA during their lifetime. Additionally, as these patients age, the arrhythmic burden increases, particularly in the form of AF and other permanent AAs [21]. These patients are at higher risk for AA due to surgical scarring and chronic hemodynamic or hypoxic stress, which lead to atrial dilation and remodelling, creating a substrate for arrhythmias [20].

AA can increase the risk of stroke in the ACHD population by up to threefold compared to ACHD patients without AA [5,22]. The underlying mechanisms are complex, involving the Virchow triad, with abnormal blood constituents, vessel wall abnormalities and abnormal blood flow [23]. Moreover, the complexity of the congenital defect influences the likelihood of TE events [24]. A retrospective multicentre cohort study conducted in the USA and Canada reported annual TE event rates of 0 %, 0.93 %, and 1.95 % for patients with AA and simple, moderate, and severe forms of CHD, respectively [24].

Another significant risk factor for TE events is valve-related procedures [25]. A notable example is patients with tetralogy of Fallot, who often require pulmonary valve replacement [26]. Mechanical heart valves (MHV) are particularly prone to thrombus formation through the activation of the intrinsic pathway (contact activation). Furthermore, MHV in the pulmonary position are associated with a higher risk of valvular thrombosis (1.7 % per patient-year) when compared to MHV in the aortic or mitral positions (around 0.3 % per patient-year) [27]. Consequently, biological valves are widely the preferred choice, with increasing numbers being percutaneously deployed. Nevertheless, even tissue valves are linked to subclinical thrombus formation at the base of the bioprosthetic cusps or on the leaflets of percutaneously implanted valves [28]. The clinical impact of these thrombi remains unclear, unlike subclinical leaflet thrombosis in aortic valves, which has been associated with increased rates of transient ischemic events and need for reoperations [29].

Moreover, ACHD patients frequently require other types of prosthetic material, such as surgical baffles, stents, leads, and shunt closure devices, all of which further elevate the risk of thrombus formation via contact activation [8]. A comprehensive meta-analysis reported device-associated thrombosis in 1.2 % of cases following percutaneous atrial septal defect closure, with the risk primarily linked to outdated devices (0 % with the Amplatzer™ occluder versus 7 % with the CardioSEAL® device) [30]. The pooled estimated rate of cerebrovascular incidents was 1.1 %, strongly correlated with the presence of AA [30]. Moreover, a more than twofold increase in the risk of systemic TE has been observed in patients with transvenous leads and intracardiac shunts [31].

Finally, heart failure is strongly linked to TE events, particularly stroke, with a sixfold higher incidence in patients aged 18–49 years [7]. The likely underlying mechanisms include blood stasis, neuroendocrine and hemorheological abnormalities, i.e., related to flow properties of blood and its elements [7].

3.2. Specific subgroups of patients

3.2.1. Fontan circulation

Fontan surgery creates a connection between the systemic venous return and the pulmonary arteries, bypassing a rudimentary or absent sub-pulmonary ventricle [8]. In these cases, TE is a common complication and one of the main causes of long-term morbidity and mortality [32]. Although the true incidence of TE has not yet been precisely determined, given the occurrence of clinically silent thrombi in the Fontan conduit and silent pulmonary thrombi, the long-term incidence has been estimated to range between 3.3 and 7.4 per 100 patient-years [[33], [34], [35]].

The underlying mechanisms for TE in Fontan circulation are complex and not fully understood, involving the three factors of Virchow's triad: stasis, hypercoagulability, and endothelial injury/dysfunction [9,36]. Stasis is inevitable in both the extracardiac conduit setting and, more significantly, in the atriopulmonary connection with subsequent atrial dilatation [35]. Additionally, there is an unpredictable disparity between procoagulant and anticoagulant factors [37]. In this setting, decreases in levels of protein C, protein S, and antithrombin III have been reported [36]. Decreased fibrinolytic activity, with increased thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitors, and increased platelet reactivity have also been noted in Fontan patients who experienced TE [38]. Furthermore, impaired endothelial function has been described [39].

Two key contributors to this imbalance in the clotting cascade are abnormal liver protein synthesis and protein-losing enteropathy [40]. Liver dysfunction can be explained by chronic systemic venous hypertension and intrinsic hemodynamic changes [41]. Protein-losing enteropathy, which occurs in 8 % of patients after Fontan surgery, leads to a loss of serum proteins into the gastrointestinal tract, further disrupting the coagulation process [40,42].

Moreover, AA are very common in this population [34]. Ten years after a Fontan operation, approximately 20 % of patients experience these episodes, which further increase their risk of TE events [34].

Another relevant issue is the presence of fenestration, which increases the risk of paradoxical embolism [43]. Although most historical studies have not demonstrated a statistically significant increase in thromboembolic events (TE) among patients with fenestration, a more recent study from the Australian and New Zealand Fontan Registry challenges these findings [43]. In this study, a propensity-score matched analysis revealed that freedom from Fontan thromboembolism at 10 and 20 years was 89.6 % (95 % CI, 85.7%–92.5 %) and 84.1 % (95 % CI, 77.2%–89.0 %) in the fenestrated group, compared with 93.5 % (95 % CI, 90.0%–95.8 %) and 88.8 % (95 % CI, 87.9%–94.9 %) in the non-fenestrated group (P = 0.03) [43]. These findings suggest the need for further investigation into this aspect.

Although many factors have been identified, their specific impact has not yet been fully established, making it difficult to identify Fontan patients at higher risk for TE.

3.3. Cyanotic congenital disease and pulmonary hypertension

Cyanotic congenital disease corresponds to a subgroup of patients with chronic hypoxemia due to an intracardiac defect with a right-to-left shunt, often associated with either pulmonary stenosis or pulmonary hypertension (PH) (i.e., Eisenmenger syndrome) [8]. These patients are typically at increased risk of both TE events and bleeding complications [8].

The most common types of thromboses are cerebral and pulmonary, with prevalence ranging from 20 % to 40 % in various computed tomography studies [[44], [45], [46]]. While cyanotic CHD without pulmonary hypertension (PH) is more frequently associated with cerebral events, Eisenmenger syndrome is more commonly linked to pulmonary thromboembolism [46].

Thrombosis arises from coagulation abnormalities, blood stasis in dilated chambers and vessels, atherosclerosis, endothelial dysfunction, the presence of thrombogenic materials, AA, pregnancy, and IE [44,47]. Hemostatic abnormalities are common and complex, involving platelet dysfunction (thrombocytopenia and thrombasthenia), disruptions in coagulation pathways, and other irregular clotting mechanisms [8]. Levels of vitamin K-dependent clotting factors and factor V are reduced, fibrinolytic activity is increased, and the largest von Willebrand factor multimers are depleted [8]. Further risk factors include female sex, low oxygen saturation, advanced age, biventricular dysfunction, and dilated pulmonary arteries [45].

In contrast, spontaneous bleeding is typically minor and self-limiting, including dental bleeding, epistaxis, easy bruising, and menorrhagia [8]. Hemoptysis is the most frequent major bleeding event (reported in up to 100 % of Eisenmenger patients) and can be secondary to arterial thrombosis, leading to pulmonary infarction [45].

This hypocoagulable state is associated with impaired fibrinogen function, elevated hematocrit, and platelet activity [[48], [49], [50]]. Paradoxically, platelet activity can also modulate the endogenous anticoagulant protein C pathway in a manner that may promote bleeding [50].

While precise estimates of incidence and hazard ratios for risk markers in these subgroups remain elusive, a deeper understanding of the physiological pathways contributing to thrombotic and bleeding risks is still achievable and should be pursued. This is highlighted by recent studies exploring the role of platelets [50].

3.4. Pregnancy

Pregnancy, the postpartum period (defined in most studies up to 6–12 weeks after delivery) and CHD are all associated with an elevated risk of thrombosis [51,52]. Venous thromboembolism during pregnancy is typically a major cause of maternal morbidity and mortality in developed countries, with an incidence ranging from 0.5 to 2.2 per 1000 pregnancies [53].

In general, this increased tendency for thrombosis is secondary to physiological changes during pregnancy and serves as an evolutionary safeguard against hemorrhage during childbirth [52]. The hormonal milieu promotes a natural activation of the coagulation cascade, including increased production of clotting factors, reduced availability of free protein S, and decreased fibrinolytic activity, resulting in a pro-thrombotic state [54] Additionally, other physiological and anatomical factors, such as increased venous capacitance and pooling, contribute to stasis, while mechanical pressure from the uterus may compress the left iliac vein [52]. Immune system changes, including a cytokine surge and vascular endothelial dysfunction, may also increase the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) [52] Additional factors, such as in vitro fertilization, pre-eclampsia, infections, and cesarean delivery, can also increase this risk [[54], [55], [56], [57]].

In women with CHD, this risk is further heightened. The ROPAC registry followed 3295 pregnant patients with CHD over ten years, reporting a 1 % incidence of TE events [58]. This increased risk is partly attributed to the complexity of the underlying cardiac defect [58]. Women with MHV had the highest rate of TE complications, with an incidence of valve thrombosis during pregnancy at 7 %, which proved fatal in 18 % of cases [58].

TE complications were also observed in 4 % of pregnant women with a Fontan procedure, and pulmonary embolism was identified as a leading cause of death in Eisenmenger patients during the postpartum period [59]. However, no TE events were reported in a recent observational study of 71 pregnancies in patients with cyanotic CHD [47]. Hemodynamic changes related to pregnancy can also trigger AA, occurring in 2 % of women in the ROPAC registry [58]. AA were linked to an increase in maternal deaths, partly due to TE complications [60].

4. Indications for thromboprophylaxis

Thromboprophylaxis in the ACHD population has several universally accepted indications [8,[17], [18], [19]]. However, many situations lack consensus due to the heterogeneity of this population and the absence of randomized controlled trials. As a result, most cases require individual evaluation, with decisions made through multidisciplinary team discussions that should incorporate the patient's preferences (Table 1) [8].

Table 1.

Indications for thromboprophylaxis in Adults with Congenital Heart Disease.

| Primary Prevention – individualized approach balancing thromboembolic and bleeding risks | Secondary Prevention – applies to all patients |

|---|---|

| Atrial arrhythmias (AF, AFL, IART) | Previous embolic stroke/TIA |

| Fontan palliationa | Deep vein thrombosis |

| Cyanotic CHDb | Pulmonary embolism |

| PHc | Previous intracardiac or intravascular thrombi |

| Stent implantation, surgical, or transcatheter proceduresd | |

| Pregnancye |

AA: atrial arrhythmia; AF: atrial fibrillation; AFL: atrial flutter; CHD: congenital heart disease; IART: intra-atrial re-entrant tachycardia; PH: pulmonary hypertension; TE: thromboembolic; TIA: transient ischemic attack.

Additional risk factors include residual intracardiac right-to-left shunts or veno-venous collaterals.

Additional risk factors such as atrial arrhythmia, mechanical heart valve or previous thromboembolic event should be present; consider increased risk of bleeding.

Additional risk factors include pulmonary artery aneurisms with thrombus or previous thromboembolic event.

Short-term vs. long-term according to the procedure; for further indications see Table 2.

For further information see Fig. 3.

Patients with a prior thromboembolic event (such as deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, embolic stroke) or a history of previous intracardiac or intravascular thrombi have a clear indication for thromboprophylaxis, including those with simple defects and persistent intracardiac shunts (class of recommendation I, level of evidence C) [8,17].

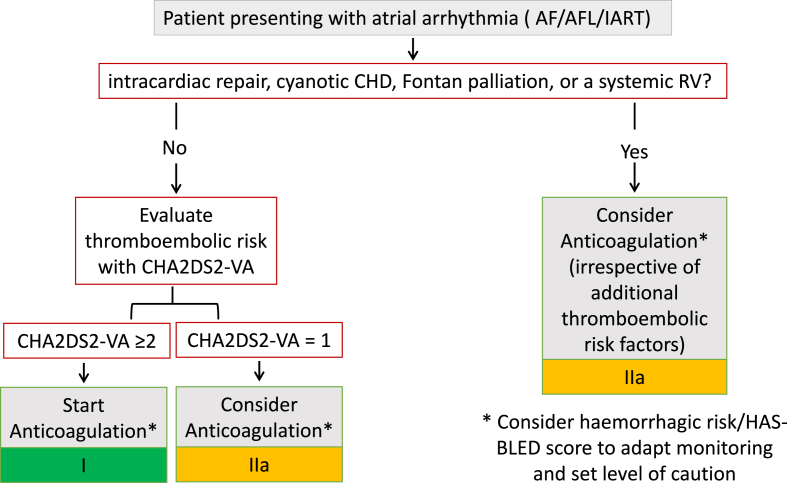

The second and most common indication is in the context of AA, including AF, AFL, and intra-atrial re-entrant tachycardia [8,[20], [21], [22]]. To date, no study has differentiated the thromboembolic risk between these various arrhythmias; thus, anticoagulation is recommended for all (class of recommendation I, level of evidence C) [8]. The 2024 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation recommend anticoagulation for all patients with AF who have undergone intracardiac repair, have cyanotic CHD, Fontan palliation, or a systemic right ventricle, regardless of individual thromboembolic risk factos [18]. For other patients, anticoagulation should be guided by general risk stratification tools for OAC use in AF, such as the CHA2DS2-VA (congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥75 years (2 points), diabetes mellitus, prior stroke/transient ischaemic attack/arterial thromboembolism (2 points), vascular disease, age 65–74 years) score (Fig. 2) [18].

Fig. 2.

Management of Thromboprophylaxis in adult congenital heart disease patientspresenting with Atrial Arrhythmias.

AF: atrial fibrillation; AFL: atrial flutter; IART: intra-atrial re-entrant tachycardia; CHA2DS2-VA: Congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥75 years (2 points), diabetes mellitus, prior stroke/transient ischaemic attack/arterial thromboembolism (2 points), vascular disease, age 65–74 years (score) CHD: congenital heart disease; HAS-BLED: Hypertension, Abnormal renal/liver function, Stroke, Bleeding history or predisposition, Labile international normalized ratio, Elderly (>65 years), Drugs/alcohol concomitantly (score); RV: right ventricle.

The American guidelines suggest that either anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy may be considered for Fontan patients, regardless of previous events, with a Class IIb recommendation and a level B-NR (nonrandomized) of evidence [17] In addition to AA and previous documented thrombus formation, anticoagulation may also be considered for Fontan patients with significant residual intracardiac right-to-left shunts or veno-venous collaterals [17].

For patients with cyanotic CHD, the rationale is similar to that for the Fontan population, though they face an even greater baseline risk of bleeding, as aforementioned [8,17]. Additionally, there are technical challenges in monitoring coagulation parameters in this population. For example, high haematocrit levels can lead to falsely elevated INR values, complicating the management of patients on antithrombotic therapy [8].

In the setting of PH, thromboprophylaxis is not generally recommended in the absence of AA, MHV, or vascular prosthesis [8]. Decisions should be made on an individual basis, for example, in cases of large PA aneurysms with thrombus or a history of previous TE events [8,45].

For patients with intracardiac defects and a high risk of paradoxical embolism, the first step is to close the shunt, if feasible [8,17]. Following stent implantation, surgical, or transcatheter procedures, thromboprophylaxis is required and will be discussed in more detail in the subsequent chapters [8,17]. It is crucial to remember the recommendation for three months of anticoagulation after surgical repair of anomalous pulmonary venous return, such as scimitar vein syndrome, as low-velocity venous flow post-surgery may result in thrombosis [17].

During pregnancy, guidelines advise considering therapeutic anticoagulation for women with PH and Eisenmenger syndrome, where pregnancy is high risk and should be discontinued, while weighing the risk of bleeding [8,19]. For other cardiac conditions that may occur during pregnancy, such as AA, heart failure, or valvular heart disease, the indication for anticoagulant therapy and regimen should adhere to general recommendations (Fig. 3) [8,19].

Fig. 3.

Thromboprophylaxis in pregnant women with congenital heart disease - indications.

AA: atrial arrhythmia; ACHD: adult congenital heart disease; CHA2DS2-VA: Congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥75 years (2 points), diabetes mellitus, prior stroke/transient ischaemic attack/arterial thromboembolism (2 points), vascular disease, age 65–74 years (score); MHV: mechanical heart valve; PH: pulmonary hypertension; TE: thromboembolic.

5. Risk scores

To date, there is no specific risk score for TE events in the ACHD population. It is known that the likelihood of an event increases with the complexity of the underlying defect, but this has not been precisely quantified [61,62]. Moreover, this population is typically young and highly heterogeneous, and some conditions are quite rare, making it difficult to conduct dedicated studies and generalize potential findings.

While some conditions are inherently too risky to leave untreated in the setting of AA, such as intracardiac repair, cyanotic CHD, Fontan palliation, or a systemic right ventricle, others require careful evaluation of both TE and hemorrhagic risks (Fig. 2) [8,18].

The CHA2DS2-VASc score, introduced in 2010, was designed to evaluate stroke risk in adults with non-valvular AF and guide decisions regarding the potential benefit of thromboprophylaxis [63]. It includes the following variables: congestive heart failure/left ventricular systolic dysfunction (C), hypertension (H), age ≥75 years (A), diabetes mellitus (D), prior stroke/transient ischemic attack/thromboembolism (S), vascular disease (V), age 65–74 years (A), and female sex category (Sc) [63]. Each risk factor is assigned a score of 1, except for age ≥75 years and prior stroke, which are associated with a higher risk and each receives a score of 2 [63]. However, the 2024 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation abolished the sex category due to challenges in daily practice, recommending treatment for patients with a CHA2DS2-VA score of 2 or more and consideration for those with a score of 1, following a patient-centered, shared care approach [18].

Conversely, the HAS-BLED score was developed to assess the risk of bleeding before initiating anticoagulation in patients with AF [64]. It assigns 1 point for each of the following bleeding risk factors: hypertension (H), abnormal renal and/or liver function (A), previous stroke (S), history of bleeding (B), labile INR (L), advanced age (E), and the use of concomitant medications and/or excessive alcohol intake (D) [64]. A score of ≥3 indicates a high risk of bleeding, including intracranial hemorrhage [18]. While a high HAS-BLED score is not a contraindication to starting anticoagulant therapy, it underscores the need to minimize reversible risk factors and increase monitoring [18].

The applicability of these scores in the ACHD cohort remains controversial. For example, Heindendael et al. found the CHA2DS2-VASc score to be an accurate tool for assessing thromboembolic risk in ACHD patients with AA, particularly when dichotomized with a cut-off of ≥2 [65]. The continuous HAS-BLED score lacked significant diagnostic value in their cohort, but when dichotomized at HAS-BLED ≥2, it was predictive of major bleeding, with an event rate of 10.8 % per year [65]. Conversely, in the retrospective multicenter cohort study by Khairy et al., the CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores were not predictive of TE risk, although HAS-BLED was independently associated with major bleeds [24].

When considering international guidelines, the 2018 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC) Guideline for the Management of Adults with Congenital Heart Disease does not provide recommendations regarding the use of either CHA2DS2-VA or HAS-BLED [17]. In contrast, the 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of adult congenital heart disease recommend the use of both risk scores in all CHD patients with AA, except in cases where treatment is required regardless of other risk factors [8]. The 2024 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation endorse this approach while also emphasizing the removal of the sex category in decision-making [18].

Finally, it is crucial to develop dedicated scoring systems to assess the indication for thromboprophylaxis in these patients, particularly in those with moderate and complex CHD.

6. Therapies

Historically, VKAs were the most used and extensively studied therapeutic options for the ACHD population [61]. Even today, they remain the primary choice in various settings—particularly for patients with MVH and those with significant mitral stenosis [66,67]. The superiority of warfarin in these scenarios is likely due to its inhibition of multiple steps in the coagulation pathway, including the contact pathway (by inhibiting the synthesis of factor IX), which is especially relevant in the context of prosthetic valves [66]. However, VKAs present several limitations, including a narrow therapeutic range, delayed onset and offset of action, numerous drug, and food interactions, significant pharmacogenetic variability, and the need for intensive management (Table 2, Table 3) [68].

Table 2.

| Antiplatelet agents only |

Antiplatelet agents or vitamin K antagonists |

Vitamin K antagonists only |

Vitamin K antagonists or Direct oral anticoagulants |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indication | Duration | Indication | Duration | Indication | Duration | Indication | Duration |

| stent implantation, TPVR, or closure device placement Aortic valve repair TAVI Pregnancy∗ |

3–6 months 3 months lifelong during |

Aortic BHV Fontan palliation (without additional risk factors) |

3 months lifelong |

MHV Significant mitral stenosis Mitral or tricuspid BHV Mitral or tricuspid valve repair Anomalous pulmonary venous return surgical repair Pregnancy∗ |

lifelong lifelong 3 months 3 months 3 months during |

AA (AF/AFL/IART) Previous TE event Previous intracardiac/ intravascular thrombi |

lifelong |

AA: atrial arrhythmia; AF: atrial fibrillation; AFL: atrial flutter; IART: intra-atrial re-entrant tachycardia; PH: pulmonary hypertension; TAVI: transcatheter aortic valve implantation; TE: thromboembolic; TIA: transient ischemic attack; TPVR: transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement.

For management during pregnancy see Fig. 5.

For common drug interactions and contraindications see Table 3.

Table 3.

Common drug interactions and contraindications with oral anticoagulants.

| Vitamin K antagonists | Direct oral anticoagulants |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apixaban | Dabigatran | Edoxaban | Rivaroxaban | |

| Target INR 2.0–3.0 | Standard full dose | Standard full dose | Standard full dose | Standard full dose |

| 5 mg twice daily | 150 mg twice daily | 60 mg once daily | 20 mg once daily | |

| >70 % of time on INR range | Reduced dose | Reduced dose | Reduced dose | Reduced dose |

| 2.5 mg twice daily | 110 mg twice daily | 30 mg once daily | 15 mg once daily | |

|

Avoid where possible NSAIDs; Fluconazole; Voriconazole; Fluoxetine |

Avoid where possible Carbamazepine; Phenytoin; Phenobarbital; Rifampicin; Ritonavir; Itraconazole; Ketoconazole | Avoid where possible Dronedarone; Carbamazepine; Phenytoin; Rifampicin; Ritonavir; Itraconazole; Ketoconazole; Cyclosporin; Glecaprevir/pibrentasvir; Tacrolimus |

Avoid where possible Carbamazepine; Phenytoin; Phenobarbital; Rifampicin; Ritonavir |

Avoid where possible Dronedarone; Carbamazepine; Phenytoin; Phenobarbital; Itraconazole; Ketoconazole; Posaconazole; Voriconazole; Rifampicin; Ritonavir |

|

Reduce dose Amiodarone; Metronidazole; Sulphonamides; Allopurinol; Fluvastatin; Gemfibrozil; Fluorouracil |

Avoid or reduce dose if another interacting drug therapy Posaconazole; Voriconazole; Protease inhibitors; Apalutamide; Enzalutamide; Tyrosine kinase inhibitors |

Delay timing of drugs and/or adjust dose Amiodarone; Ticagrelor; Verapamil; Quinidine; Clarithromycin; Posaconazole |

Avoid or reduce dose Dronedarone |

Avoid if another interacting drug therapy Protease inhibitors; Tyrosine kinase inhibitors |

|

Avoid or reduce dose if another interacting drug therapy Cyclosporin; Itraconazole; Ketoconazole; Erythromycin |

Caution if renal function impaired Verapamil; Cyclosporin; Clarithromycin; Erythromycin; Fluconazole |

|||

| Increase dose Carbamazepine | ||||

| Vitamin K antagonists | Direct oral anticoagulants |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apixaban | Dabigatran | Edoxaban | Rivaroxaban | |

|

Monitor INR carefully Dronedarone; Statins; Penicillin antibiotics; Macrolide antibiotics; Quinolone antibiotics; Rifampicin; Methotrexate; Ritonavir; Phenytoin; Sodium valproate; Tamoxifen; Chemotherapies |

Two out of three needed for dose reduction:

|

Dose reduction recommended if any apply:

|

Dose reduction if any apply:

|

Dose reduction if: Creatinine clearance 15–49 mL/min. |

|

Limit consumption Alcohol Grapefruit/cranberry juice St John's wort |

Limit consumption | Limit consumption | Limit consumption | Limit consumption |

| Grapefruit juice | Grapefruit juice | Grapefruit juice | Grapefruit juice | |

| St John's wort | St John's wort | St John's wort | St John's wort | |

The paradigm shifted with the development of NOACs, which offer superior pharmacokinetics and high specificity, with no need for monitoring or frequent dose adjustments [[69], [70], [71], [72]]. Evidence for their safety and efficacy in the ACHD population has been progressively increasing [16,68]. The first prospective study to document their benefit was published in 2016 by Pujol et al. This study included 75 patients, of whom 21 % had complex CHD, five had cyanosis, and three had undergone Fontan palliation, with a mean follow-up of 12 ± 11 months and no reported thromboembolic or bleeding events [73]. These findings were further validated by the international NOTE registry, which included more than 500 patients, the majority (85 %) with either moderate or complex CHD, followed for a median of one year [IQR 0–2] [15]. Furthermore, this year, in the context of AA, the PROTECT-AR study confirmed the non-inferiority of apixaban compared to warfarin regarding stroke and TE events, with a similar risk of major bleeding [74]. This study included 143 patients (55.5 %) with moderate and complex CHD and 29 patients (13.3 %) with BHV [74]. It is noteworthy that even for Fontan palliation, several observational studies document NOACs’ efficacy and safety in this specific scenario, which will likely be addressed in future guidelines [36,75].

Nevertheless, there was a study from a German database including 44,097 ACHD patients treated with VKAs or NOACs with multiple backgrounds in which NOACs we associated with higher rates of TE events (3.8 % vs. 2.8 %), major adverse cardiovascular events (7.8 % vs. 6.0 %), bleeding rates (11.7 % vs. 9.0 %), and all-cause mortality (4.0 % vs. 2.8 %; all P < 0.05) after one year of therapy compared with VKAs [14]. Even though this study included a greater number of patients, it is still subject to selection bias, as up to one-third of these patients were only under local general cardiology care [14]. Ultimately, until further data from prospective studies is available, this study warns us that VKAs may be the safest option for the majority of ACHD patients and initiation of NOACs should be reserved for experienced ACHD cardiologists, carefully weighing risk-benefit profiles on an individual patient basis [68].

The role of antiplatelet therapy, particularly ASA, is more limited. In Fontan patients, a meta-analysis suggested a lower incidence of TE with either ASA or warfarin prophylaxis, which was confirmed by a large study using propensity score matching [12,76]. However, failure rates with both agents remained high (∼9 %), likely due to suboptimal anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy [12]. Although the theoretical benefits of warfarin over aspirin for preventing thromboembolism in patients with atrial arrhythmias or a history of thromboembolism are evident, real-world data supporting this comes mainly from small observational studies and lacks further confirmation from larger series [9]. Therefore, treatment decisions for Fontan patients should be individualized, weighing the benefits of antiplatelet versus anticoagulation therapy [8,17].

Antiplatelet agents also play a crucial role after stent implantation, transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement, or closure device placement, as they are typically prescribed empirically for three to six months [8,17]. Although pulmonary valve replacement is linked to a higher risk of thromboembolic events and infective endocarditis (IE), there is no consensus regarding the need for lifelong thromboprophylaxis [28,77].

Additionally, as in the general population, all patients with MHV require lifelong VKAs [78]. For patients without a baseline indication for oral anticoagulation (OAC), warfarin should be considered for three months following mitral or tricuspid biologic heart valve (BHV) implantation [78]. ASA or warfarin should also be considered for three months after the surgical implantation of an aortic BHV [78].

When managing pregnant patients, there are once again no randomized controlled trials, so the evidence is drawn from observational studies [10,13,51,53]. Long-term anticoagulation during this period is linked to an elevated risk of maternal hemorrhage and TE complications, as well as an increased likelihood of fetal loss [13]. In the case of warfarin, there is also the potential for teratogenic effects [13]. NOACs also cross the placenta and may pose a risk of fetal bleeding or embryopathy, although evidence in this area is limited [79]. Current guidelines advise against the use of NOACs in pregnancy [19]. The selection of a particular anticoagulant must carefully balance maternal health with the risks to both mother and fetus and should be tailored to the individual [19]. The guidelines suggest considering the continuation of VKAs in women with MHV when the VKA dose is low, as VKAs remain the most effective strategy for preventing valve thrombosis during pregnancy (Fig. 4 and 5 ). Otherwise, VKAs should be discontinued and substituted with adjusted-dose unfractionated heparin (UFH) or low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) with anti-Xa levels monitoring, which is our preferred approach [19]. Additionally, they recommend prophylactic anticoagulation with LMWH for patients at high risk of TE, such as those with Fontan circulation or pulmonary hypertension, and applying the same guidelines for patients with atrial arrhythmias as for non-pregnant individuals [19].

Fig. 5.

Thromboprophylaxis in pregnant women with congenital heart disease – management if previous indication for low dose of VKA.

aPTT: activated partial thromboplastin time; INR: international normalized ratio; i.v.: intravenous; LMWH: low molecular weight heparin; MHV: mechanical heart valve; Trim.: trimester; UFH: unfractionated heparin; VKA: vitamin K antagonist.a weeks 6–12; bmonitoring LMWH: starting dose for LMWH is 1 mg/kg body weight for enoxaparin and 100 IU/kg for dalteparin, twice daily subcutaneously; -in-hospital daily anti-Xa levels until target, then weekly (I); -target anti- Xa levels: 1.0–1.2 U/ml (mitral and right sided MHV) or 0.8–1.2 U/ml (aortic MHV) 46 h post-dose (I); -pre-dose anti-Xa levels >0.6 U/ml (IIb).

† There are concerns on risk of cerebral bleeding even with low dosage (underreported.

Fig. 4.

Thromboprophylaxis in pregnant women with congenital heart disease – management if previous indication for high dose of VKA.

aPTT: activated partial thromboplastin time; INR: international normalized ratio; i.v.: intravenous; LMWH: low molecular weight heparin; MHV: mechanical heart valve; Trim.: trimester; UFH: unfractionated heparin; VKA: vitamin K antagonist.a weeks 6–12; bmonitoring LMWH: starting dose for LMWH is 1 mg/kg body weight for enoxaparin and 100 IU/kg for dalteparin, twice daily subcutaneously; -in-hospital daily anti-Xa levels until target, then weekly (I); -target anti- Xa levels: 1.0–1.2 U/ml (mitral and right sided MHV) or 0.8–1.2 U/ml (aortic MHV) 46 h post-dose (I); -pre-dose anti-Xa levels >0.6 U/ml (IIb).

7. Conclusion

Thromboprophylaxis in the ACHD population is of utmost importance, as TE events are a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in these patients. While the inherent risk is closely related to the complexity of the underlying defects, several cumulative risk factors play a significant role, including AA, device-related procedures, IE, heart failure, and pregnancy. Immediate anticoagulation is required in the presence of AA for conditions such as Fontan palliation and cyanotic CHD who were not medicated or were on antiplatelet regimens. Nevertheless, for the general ACHD population, a comprehensive evaluation of both thromboembolic and hemorrhagic risks should be performed, utilizing tools like CHA2DS2-VA and HAS-BLED. In patients with MHV and significant mitral stenosis, VKA remains the only option, though NOACs may be a safe alternative for other indications. Thromboprophylaxis is nearly universal in Fontan patients, and NOACs are anticipated to assume a prominent role in the near future. The choice should always be individualized and discussed with the patient. Further efforts toward developing multicenter, prospective, and ideally randomized controlled trials are essential to generate evidence that can standardize guidelines and improve daily practice in ACHD.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Mariana Sousa Paiva: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Jorge Ferreira: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Methodology. Rui Anjos: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision. Michael A. Gatzoulis: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization.

Funding

No funding.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. MAG is the IJCCHD Editor in Chief but was not involved with the handling of this paper.

Acknowledgements

I am deeply grateful to Dr. Sérgio Madeira for his invaluable mentorship in ACHD and to Prof. Adragão for supporting my fellowship, which greatly enriched my experience and contributed to this work.

Contributor Information

Mariana Sousa Paiva, Email: marianasousapaiva@gmail.com.

Jorge Ferreira, Email: jorge_ferreira@netcabo.pt.

Rui Anjos, Email: ranjos@ulslo.min-saude.pt.

Michael A. Gatzoulis, Email: M.Gatzoulis@rbht.nhs.uk.

References

- 1.Baumgartner H. Geriatric congenital heart disease: a new challenge in the care of adults with congenital heart disease? Eur Heart J. 2014;35:683–685. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marelli A.J., Ionescu-Ittu R., Mackie A.S., Guo L., Dendukuri N., et al. Lifetime prevalence of congenital heart disease in the general population from 2000 to 2010. Circulation. 2014;130:749–756. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.008396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Engelfriet P., Boersma E., Oechslin E., Tijssen J., Gatzoulis M.A., et al. The spectrum of adult congenital heart disease in Europe: morbidity and mortality in a 5 year follow-up period. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:2325–2333. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaemmerer H., Fratz S., Bauer U., Oechslin E., Brodherr-Heberlein S., et al. Emergency hospital admissions and three-year survival of adults with and without cardiovascular surgery for congenital cardiac disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;126:1048–1052. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(03)00737-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mandalenakis Z., Rosengren A., Lappas G., Eriksson P., Hansson P.O., et al. Ischemic stroke in children and young adults with congenital heart disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:1–8. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.003071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prokšelj K. Stroke and systemic embolism in adult congenital heart disease. Int J Cardiol Congenit Heart Dis. 2023;12 doi: 10.1016/J.IJCCHD.2023.100453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lanz J., Brophy J.M., Therrien J., Kaouache M., Guo L., et al. Stroke in adults with congenital heart disease incidence, cumulative risk, and predictors. Circulation. 2015;132:2385–2394. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.011241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baumgartner H., de Backer J., Babu-Narayan S.V., Budts W., Chessa M., et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of adult congenital heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:563–645. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Westhoff-Bleck M., Klages C., Zwadlo C., Sonnenschein K., Sieweke J.-T., et al. Thromboembolic characteristics and role of anticoagulation in long-standing Fontan circulation. Int J Cardiol Congenit Heart Dis. 2022;7 doi: 10.1016/J.IJCCHD.2022.100328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Voortman M., Roos J.W., Slomp J., van Dijk A.P.J., Bouma B.J., et al. Strategies for low-molecular-weight heparin management in pregnant women with mechanical prosthetic heart valves: a nationwide survey of Dutch practice. Int J Cardiol Congenit Heart Dis. 2022;9 doi: 10.1016/J.IJCCHD.2022.100373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang H., Heidendael J.F., de Groot J.R., Konings T.C., Veen G., et al. Oral anticoagulant therapy in adults with congenital heart disease and atrial arrhythmias: implementation of guidelines. Int J Cardiol. 2018;257:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alsaied T., Alsidawi S., Allen C.C., Faircloth J., Palumbo J.S., et al. Strategies for thromboprophylaxis in Fontan circulation: a meta-analysis. Heart. 2015;101:1731–1737. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-307930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steinberg Z.L., Dominguez-Islas C.P., Otto C.M., Stout K.K., Krieger E.V. Maternal and fetal outcomes of anticoagulation in pregnant women with mechanical heart valves. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:2681–2691. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.03.605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freisinger E., Gerß J., Makowski L., Marschall U., Reinecke H., et al. Current use and safety of novel oral anticoagulants in adults with congenital heart disease: results of a nationwide analysis including more than 44 000 patients. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:4168–4177. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang H., Bouma B.J., Dimopoulos K., Khairy P., Ladouceur M., et al. Non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) for thromboembolic prevention, are they safe in congenital heart disease? Results of a worldwide study. Int J Cardiol. 2020;299:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dirbach F., Goulouti E., Bouchardy J., Ladouceur M., Alberio L., et al. A new strategy for monitoring of direct oral anticoagulants in patients with cyanotic and complex congenital heart disease. Int J Cardiol Congenit Heart Dis. 2024;18 doi: 10.1016/J.IJCCHD.2024.100545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stout K.K., Daniels C.J., Aboulhosn J.A., Bozkurt B., Broberg C.S., et al. 2018 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of adults with congenital heart disease: a report of the American College of cardiology/American heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2019;139:e698–e800. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Gelder I.C., Rienstra M., V Bunting K., Casado-Arroyo R., Caso V., et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) Eur Heart J. 2024:3314–3414. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehae176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Regitz-Zagrosek V., Roos-Hesselink J.W., Bauersachs J., Blomström-Lundqvist C., Cífková R., et al. 2018 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3165–3241. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bouchardy J., Therrien J., Pilote L., Ionescu-Ittu R., Martucci G., et al. Atrial arrhythmias in adults with congenital heart disease. Circulation. 2009;120:1679–1686. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.866319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lambordada F., Hamilton R., Shohoudi A., Aboulhosn J., Broberg C., et al. Increasing prevalence of atrial fibrillation and permanent atrial arrhythmias in congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:857–865. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mandalenakis Z., Rosengren A., Lappas G., Eriksson P., Gilljam T., et al. Atrial fibrillation burden in young patients with congenital heart disease. Circulation. 2018;137:928–937. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.029590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamel H., Okin P.M., V Elkind M.S., Iadecola C. Atrial fibrillation and mechanisms of stroke. Stroke. 2016;47:895–900. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.012004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khairy P., Aboulhosn J., Broberg C.S., Cohen S., Cook S., et al. Thromboprophylaxis for atrial arrhythmias in congenital heart disease: a multicenter study. Int J Cardiol. 2016;223:729–735. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.08.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ionescu-Ittu R., MacKie A.S., Abrahamowicz M., Pilote L., Tchervenkov C., et al. Valvular operations in patients with congenital heart disease: increasing rates from 1988 to 2005. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90:1563–1569. doi: 10.1016/J.ATHORACSUR.2010.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caughron H., Kim D., Kamioka N., Lerakis S., Yousef A., et al. Repeat pulmonary valve replacement: similar intermediate-term outcomes with surgical and transcatheter procedures. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:2495–2503. doi: 10.1016/J.JCIN.2018.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Toole J.M., Stroud M.R., Kratz J.M., Crumbley A.J., III, Bradley S.M., et al. Twenty-five year experience with the st. Jude medical mechanical valve prosthesis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:1402–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jewgenow P., Schneider H., Bökenkamp R., Hörer J., Cleuziou J., et al. Subclinical thrombus formation in bioprosthetic pulmonary valve conduits. Int J Cardiol. 2019;281:113–118. doi: 10.1016/J.IJCARD.2019.01.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chakravarty T., Søndergaard L., Friedman J., De Backer O., et al. Subclinical leaflet thrombosis in surgical and transcatheter bioprosthetic aortic valves: an observational study. Lancet. 2017;389:2383–2392. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30757-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abaci A., Unlu S., Alsancak Y., Kaya U., Sezenoz B. Short and long term complications of device closure of atrial septal defect and patent foramen ovale: meta-analysis of 28,142 patients from 203 studies. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;82:1123–1138. doi: 10.1002/ccd.24875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khairy P., Landzberg M.J., Gatzoulis M.A., Mercier L.-A., Fernandes S.M., et al. Transvenous pacing leads and systemic thromboemboli in patients with intracardiac shunts. Circulation. 2006;113:2391–2397. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.622076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alsaied T., Bokma J.P., Engel M.E., Kuijpers J.M., Hanke S.P., et al. Factors associated with long-term mortality after Fontan procedures: a systematic review. Heart. 2017;103:104. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-310108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaulitz R., Ziemer G., Rauch R., Girisch M., Bertram H., et al. Prophylaxis of thromboembolic complications after the Fontan operation (total cavopulmonary anastomosis) J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129:569–575. doi: 10.1016/J.JTCVS.2004.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Egbe A.C., Miranda W.R., Devara J., Shaik L., Iftikhar M., et al. Recurrent sustained atrial arrhythmias and thromboembolism in Fontan patients with total cavopulmonary connection. IJC Heart & Vasculature. 2021;33 doi: 10.1016/J.IJCHA.2021.100754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laflamme E., Roche S.L. Fontan circuit thrombus in adults: often silent, rarely innocent. Can J Cardiol. 2019;35:1631–1634. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2019.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heidendael J.F., Engele L.J., Bouma B.J., Dipchand A.I., Thorne S.A., et al. Coagulation and anticoagulation in fontan patients. Can J Cardiol. 2022;38:1024–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2022.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Odegard K.C., McGowan F.X., Zurakowski D., DiNardo J.A., Castro R.A., et al. Procoagulant and anticoagulant factor abnormalities following the fontan procedure: increased factor VIII may predispose to thrombosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;125:1260–1267. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(02)73605-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ravn H.B., Hjortdal V.E., V Stenbog E., Emmertsen K., Kromann O., et al. Increased platelet reactivity and significant changes in coagulation markers after cavopulmonary connection. Heart. 2001;85:61. doi: 10.1136/heart.85.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Binotto M.A., Maeda N.Y., Lopes A.A. Altered endothelial function following the Fontan procedure. Cardiol Young. 2008;18:70–74. doi: 10.1017/S1047951107001680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Atz A.M., Zak V., Mahony L., Uzark K., D’agincourt N., et al. Longitudinal outcomes of patients with single ventricle after the fontan procedure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:2735–2744. doi: 10.1016/J.JACC.2017.03.582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Procelewska M., Kolcz J., Januszewska K., Mroczek T., Malec E. Coagulation abnormalities and liver function after hemi-Fontan and Fontan procedures - the importance of hemodynamics in the early postoperative period. Eur J Cardio Thorac Surg. 2007;31:867–873. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rychik J. Protein-losing enteropathy after fontan operation. Congenit Heart Dis. 2007;2:288–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0803.2007.00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Daley M., Buratto E., King G., Grigg L., Iyengar A., et al. Impact of fontan fenestration on long‐term outcomes: a propensity score–matched analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.122.026087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Silversides C.K., Granton J.T., Konen E., Hart M.A., Webb G.D., et al. Pulmonary thrombosis in adults with Eisenmenger syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1982–1987. doi: 10.1016/J.JACC.2003.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Broberg C.S., Ujita M., Prasad S., Li W., Rubens M., et al. Pulmonary arterial thrombosis in eisenmenger syndrome is associated with biventricular dysfunction and decreased pulmonary flow velocity. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:634–642. doi: 10.1016/J.JACC.2007.04.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jensen A.S., Idorn L., Thomsen C., Von Der Recke P., Mortensen J., et al. Prevalence of cerebral and pulmonary thrombosis in patients with cyanotic congenital heart disease. Heart. 2015;101:1540–1546. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-307657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ladouceur M., Benoit L., Basquin A., Radojevic J., Hauet Q., et al. How pregnancy impacts adult cyanotic congenital heart disease: a multicenter observational study. Circulation. 2017;135:2444–2447. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.027152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jensen A.S., Johansson P.I., Bochsen L., Idorn L., Sørensen K.E., et al. Fibrinogen function is impaired in whole blood from patients with cyanotic congenital heart disease. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:2210–2214. doi: 10.1016/J.IJCARD.2012.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jensen A.S., Johansson P.I., Idorn L., Sørensen K.E., Thilén U., et al. The haematocrit – an important factor causing impaired haemostasis in patients with cyanotic congenital heart disease. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:1317–1321. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.03.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kevane B., Allen S., Walsh K., Egan K., Maguire P.B., et al. Dual endothelin‐1 receptor antagonism attenuates platelet‐mediated derangements of blood coagulation in Eisenmenger syndrome. J Thromb Haemost. 2018;16:1572–1579. doi: 10.1111/jth.14159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Greer I.A. Thrombosis in pregnancy: maternal and fetal issues. Lancet. 1999;353:1258–1265. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10265-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bukhari S., Fatima S., Barakat A.F., Fogerty A.E., Weinberg I., et al. Venous thromboembolism during pregnancy and postpartum period. Eur J Intern Med. 2022;97:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2021.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu S., Rouleau J., Joseph K.S., Sauve R., Liston R.M., et al. Epidemiology of pregnancy-associated venous thromboembolism: a population-based study in Canada. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2009;31:611–620. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cerneca F., Ricci G., Simeone R., Malisano M., Alberico S., et al. Coagulation and fibrinolysis changes in normal pregnancy. Increased levels of procoagulants and reduced levels of inhibitors during pregnancy induce a hypercoagulable state, combined with a reactive fibrinolysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1997;73:31–36. doi: 10.1016/S0301-2115(97)02734-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hansen A.T., Kesmodel U.S., Juul S., Hvas A.M. Increased venous thrombosis incidence in pregnancies after in vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod. 2014;29:611–617. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van Pampus M.G., Dekker G.A., Wolf H., Huijgens P.C., Koopman M.M.W., et al. High prevalence of hemostatic abnormalities in women with a history of severe preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:1146–1150. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(99)70608-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lindqvist P., Dahlbäck B., Marŝál K. Thrombotic risk during pregnancy: a population study. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:595–599. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(99)00308-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Roos-Hesselink J., Baris L., Johnson M., De Backer J., Otto C., et al. Pregnancy outcomes in women with cardiovascular disease: evolving trends over 10 years in the ESC Registry of Pregnancy and Cardiac disease (ROPAC) Eur Heart J. 2019;40:3848–3855. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bédard E., Dimopoulos K., Gatzoulis M.A. Has there been any progress made on pregnancy outcomes among women with pulmonary arterial hypertension? Eur Heart J. 2009;30:256–265. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Salam A.M., Ertekin E., Van Hagen I.M., Al Suwaidi J., Ruys T.P.E., et al. Atrial fibrillation or flutter during pregnancy in patients with structural heart disease: data from the ROPAC (registry on pregnancy and cardiac disease) JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2015;1:284–292. doi: 10.1016/J.JACEP.2015.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sinning C., Zengin E., Blankenberg S., Rickers C., von Kodolitsch Y., et al. Anticoagulation management in adult patients with congenital heart disease: a narrative review. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2021;11:1324–1333. doi: 10.21037/cdt-20-631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Karsenty C., Waldmann V., Mulder B., Hascoet S., Ladouceur M. Thromboembolic complications in adult congenital heart disease: the knowns and the unknowns. Clin Res Cardiol. 2021;110:1380–1391. doi: 10.1007/s00392-020-01746-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lip G.Y.H., Nieuwlaat R., Pisters R., Lane D.A., Crijns H.J.G.M., et al. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: the Euro Heart Survey on atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2010;137:263–272. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pisters R., Lane D.A., Nieuwlaat R., de Vos C.B., Crijns H.J.G.M., et al. A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess 1-year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation: the euro heart survey. Chest. 2010;138:1093–1100. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Heidendael J.F., Bokma J.P., De Groot J.R., Koolbergen D.R., Mulder B.J.M., et al. Weighing the risks: thrombotic and bleeding events in adults with atrial arrhythmias and congenital heart disease. Int J Cardiol. 2015;186:315–320. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Eikelboom J.W., Connolly S.J., Brueckmann M., Granger C.B., Kappetein A.P., et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with mechanical heart valves. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1206–1214. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1300615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Connolly S.J., Karthikeyan G., Ntsekhe M., Haileamlak A., El Sayed A., et al. Rivaroxaban in rheumatic heart disease–associated atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:978–988. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa2209051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Verhamme P., Budts W., Van de Werf F. Non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants in adults with congenital heart disease: quod non? Eur Heart J. 2020;41:4178–4180. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Connolly S.J., Ezekowitz M.D., Yusuf S., Eikelboom J., Oldgren J., et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1139–1151. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa0905561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Patel M.R., Mahaffey K.W., Garg J., Pan G., Singer D.E., et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:883–891. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Granger C.B., Alexander J.H., McMurray J.J.V., Lopes R.D., Hylek E.M., et al. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:981–992. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1107039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Giugliano R.P., Ruff C.T., Braunwald E., Murphy S.A., Wiviott S.D., et al. Edoxaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2093–2104. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1310907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pujol C., Niesert A.C., Engelhardt A., Schoen P., Kusmenkov E., et al. Usefulness of direct oral anticoagulants in adult congenital heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 2016;117:450–455. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kartas A., Papazoglou A.S., Moysidis D.V., Despotopoulos S., Baroutidou A., et al. Use of apixaban in adults with congenital heart disease and atrial arrhythmias: the PROTECT-AR study. Int J Cardiol. 2024;406 doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2024.131993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kawamatsu N., Ishizu T., Machino-Ohtsuka T., Masuda K., Horigome H., et al. Direct oral anticoagulant use and outcomes in adult patients with Fontan circulation: a multicenter retrospective cohort study. Int J Cardiol. 2021;327:74–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Iyengar A.J., Winlaw D.S., Galati J.C., Wheaton G.R., Gentles T.L., et al. No difference between aspirin and warfarin after extracardiac Fontan in a propensity score analysis of 475 patients. Eur J Cardio Thorac Surg. 2016;50:980–987. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezw159. on behalf of the A. and N.Z.F. Registry. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hascoet S., Pozza R.D., Bentham J.R., Carere R., Kanaan M., et al. Early outcomes of percutaneous pulmonary valve implantation using the Edwards SAPIEN 3 transcatheter heart valve system. EuroIntervention. 2019;14:1378–1385. doi: 10.4244/EIJ-D-18-01035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vahanian A., Beyersdorf F., Praz F., Milojevic M., Baldus S., et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:561–632. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Søgaard M., Skjøth F., Nielsen P.B., Beyer-Westendorf J., Larsen T.B. First trimester anticoagulant exposure and adverse pregnancy outcomes in women with preconception venous thromboembolism: a nationwide cohort study. Am J Med. 2022;135:493–502.e5. doi: 10.1016/J.AMJMED.2021.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]