Abstract

Background

The mental health of adolescents is the key to ensure their smooth growth. This study aimed to explore the underlying mechanism between bullying victimization and boarding adolescents’ mental health problems in rural China.

Methods

A total of 2155 boarding adolescents from middle schools (Nboy = 936, Ngirl = 1219, Mage = 13.86, SD = 0.81) participated in this survey and completed four questionnaires on bullying victimization, parenting styles, self-esteem and mental health problems.

Results

Results shown that: (1) In rural China, about one fifth of boarding adolescents were in an unhealthy mental state, and learning anxiety was the most common mental health problem reported by them; (2) Bullying victimization had a significant effect on boarding adolescents’ mental health problems, and the more bullied experiences predict more serious mental health problems; (3) Self-esteem played a mediating role in bullying victimization and boarding adolescents’ mental health problems, whiles parenting styles played a moderating role.

Conclusion

Bullying victimization has been shown to decrease self-esteem, which in turn contributes to mental health problems among boarding adolescents. Low-level negative parenting styles further intensify these issues. Consequently, the education department and educators must prioritize addressing school bullying and protecting the mental health of boarding students. Most importantly, collaboration with parents is essential to foster the healthy development of these adolescents.

Keywords: Bullying victimization, Mental health problems, Parenting styles, Self-esteem, Boarding adolescents

Background

Due to the rapid development of urbanization in China recently, more and more rural schools have become vacant due to a serious shortage of students, and have to be merged. However, the location of the merged school is relatively far from students’ own homes, resulting in an increasing number of rural boarding students [1]. According to the latest reports, there were about 20.74 million boarding students in China, accounting for 46.7% of the total number of middle school students in the country and 94.1% middle schools were boarding schools in rural China [2]. Mental problems are the main risk faced by boarding adolescents in their development, which has attracted more and more researchers’ attention. It is necessary to identify the causes of their mental health problems, which are also prerequisites for ensuring the mental health of boarding adolescents. Latest research shown that factors from peers, oneself and parents were important predictors of psychological problems affecting boarding adolescents, and individual and interpersonal factors jointly affect the behavior of rural boarding students [3–6]. In addition, the impact of school bullying on students psychological development cannot be ignored. Students who experience bullying often suffer from anxiety, depression, and low self-esteem. These psychological traumas can have long-lasting effects on their personal growth and social skills. However, current research focuses more on how to intervene in the behavior of bullies than on the protection of the mental health of victims. According to ecological systems theory, individual psychological development is the result of the interaction between the micro environmental system centered on the family and the individual, and the psychological health development of boarding adolescents is also the same [7]. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to reveal the indirect role of self-esteem and parenting styles between peer bullying and mental health problems. It was expected to provide more research evidence to explain the underlying effect mechanism of bullying victimization on mental health problems in boarding adolescents, and provide the necessary foundation and guidance for further intervention research or activities.

Bully victimization and boarding adolescents’ mental health problems

Bullying victimization refers to the phenomenon that individuals suffer physical, verbal, interpersonal, property, and other damages during bullying, especially peer bullying [8]. There is no doubt that the harm done to the victims goes far beyond the harm to the operators. However, almost all bullying operators underestimate the negative impact of their behaviors on the victims. Adolescents who have been bullied frequently might drop out of school, socially withdraw, and even commit suicide, which seriously endangers their social development and life safety [9]. What’s more serious is that the damage of bullying to the victims is permanent. Lee’s study in 2020 found that the experience of bullying victimization in childhood profoundly endangers the psychological development in adulthood. Both the traditional and cyberbullying victimization increased adulthood’s anxiety symptoms [8].

More and more studies have confirmed that bullying victimization has a devastating negative impact on adolescents’ mental health at that time and in the future [10]. For example, through a two-year longitudinal study of first-year secondary school students in Rotterdam, Bannink et al. found that traditional bullying victimization was associated with an increased risk of suicidal ideation. In contrast, traditional and cyberbullying victimization was associated with an increased risk of girls’ mental health problems [11, 12]. Furthermore, experiencing frequent bullying during childhood is associated with self-labeling and a tendency to seek help for mental health issues in adulthood [10].

Recent studies have indicated that boarding students are at higher risk of exposure to bullying than those non-boarding students [3]. That is, bullying is more frequent among boarding students than day students [3, 4]. This is because students from boarding schools are more likely to have externalized problematic behaviors that make their peers suffer [3]. In addition, since most of the week’s activities are limited to the school environment, boarders’ daily behaviors are extremely lacking parental supervision, coupled with their unique collective accommodation and eating habits, making them more likely to have conflicts with their peers and adopt irrational coping strategies [3, 4]. At the same time, boarding adolescents’ mental health problems caused by bullying victimization are also very worrying. For example, Yin et al. found that bullying victimization significantly predicted the depression level of Chinese boarding adolescents (average age 13.52 years old) and thus easily made them at risk of a depressed state [3, 4].

In China, the mental health problems of boarding adolescents who are victims of school bullying may be more serious. Different from other countries, the main reasons for Chinese teenagers to choose boarding are that they are far away from home and backward in economic development. Boarding schools are generally distributed in rural areas and are shared by many different villages. However, more and more evidence shows that victims of bullying are likely to cause psychological problems of adolescents indirectly through internal and external factors. These factors include self-esteem, which is directly related to self-assessment, and parenting styles, which are related to parent-child interaction.

The effect of self-esteem

Self-esteem is also an important predictor of mental health problems. Self-esteem refers to an individual’s perception and evaluation of self-worth and importance [11, 13]. Self-esteem has a significant predictive effect on the depression level and suicidal intention of Asian adolescents [14]. Individuals with ostensibly high self-esteem may project an exterior of fortitude, yet internally, they often possess a tenuous sense of self-worth and exhibit a marked lack of resilience in the face of adversity [15]; while low self-esteem people usually suffer from loneliness, anxiety, depression, and social anxiety [11]. A latent profile analysis showed that there might be such a correlation that high and moderate self-esteem levels were associated with fewer mental health problems, while low self-esteem was linked to a greater prevalence of mental health challenges [16].

Negative life events are non-ignorable environmental causes of adolescents’ self-esteem development, and bullying is one of these events [17, 18]. Being bullied at school puts adolescents in a vicious circle. Recent studies have found that victims of bullying would fall into a situation of low self-esteem, which in turn predicts the subsequent bullying victimization [19]. A meta-analysis study involving samples from the United States, France, and the United Kingdom showed that peer victimization has a lasting negative impact on adolescents’ self-esteem. Low self-esteem is also one of the reasons for being a victim [20]. However, in samples of Chinese adolescents, more research findings support the view that bullying victimization is a long-term predictor of low self-esteem [16, 21]. Generally speaking, the experience of being bullied will significantly reduce adolescents’ evaluation of themselves and then hinders their mental health development [16]. In addition, studies have shown that self-esteem does mediate between bullying victimization and mental health problems [21]. Therefore, it can be inferred that self-esteem is likely to be an important mediator between bullying victimization and mental health problems in Chinese boarding adolescents.

The role of parenting styles

According to the ecological systems theory, the family environment plays a crucial role in individual development and its interactions, highlighting the moderating influence of familial factors, with parenting styles being a primary source among them [7]. Parenting styles involve parents’ attitudes, emotions, and behaviors in raising their kids [21, 22]. Different types of parenting styles have different effects on children’s and adolescents’ development. Parents’ positive parenting styles (e.g., warmth and understanding) can, to a large extent, protect adolescents from the risks of bullying or depression, while negative parenting styles (e.g., punishment and harshness, excessive interference, rejection and denial, and overprotection) will increases these risks [5, 6]. At the same time, positive parenting styles are also easier to cultivate self-affirming children, who have a higher overall evaluation of themselves, while negative parenting styles are more likely to lead to low self-esteem [23]. It can be seen that there are known differences between positive and negative parenting styles in bullying victimization, mental health problems, and self-esteem. In this sense, parenting styles can have important and lasting impacts on child development. Any inappropriate parenting styles such as physical punishments may lead to unwanted damaging effects on the mental health of children [24]. Therefore, parenting styles would be a moderator between bullying victimization, self-esteem, and mental health problems.

Due to the lower frequency of interaction with their parents, boarding adolescents tend to be more independent and free than day students. Still, at the same time, they also show a lower degree of intimacy in their interactions with their parents [25]. Thus, although it can provide a better learning environment for adolescents from rural China and improve their cognitive outcomes, boarding schools often fail to fully meet their nutritional, health, and emotional needs [26]. More notably, the care and support from parents can hardly be replaced by teachers or peers, and boarding schools cannot fully compensate for the emotional needs of parents and family. Therefore, whether parents can provide adequate emotional support and understanding for their children in boarding schools is also largely related to whether they can adapt to school life and smoothly pass the “turbulent” adolescence [5]. In short, positive parenting styles are likely to be an important protective factor for Chinese boarding adolescents’ mental health development. On the contrary, negative parenting styles may be potentially destructive factors.

The current study

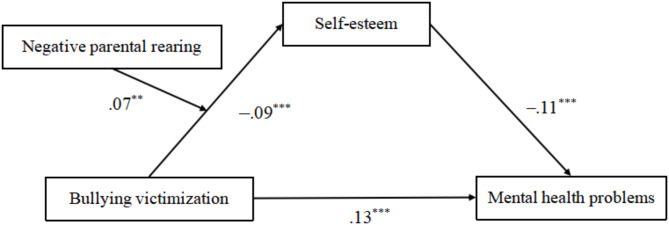

An existing study confirmed that after the transition to the boarding system, the report rate of bullying increased significantly [27]. This finding suggested that it is critical to pay more attention to school bullying in boarding students and its negative consequences. However, there are remarkable cultural and contextual differences in boarding schools across countries. In Germany, for example, boarding students usually come from relatively wealthy families [3]. In contrast, boarding students are generally people with lower socioeconomic status in China, for boarding schools are more in rural or even poor areas [4]. Therefore, Chinese boarding students tend to be more disadvantaged and vulnerable to school bullying than their counterparts in Germany. Against the backdrop of the constantly changing urban-rural structure in China, due to the lack of educational resources and family management, most rural students in China choose to live in boarding schools. Due to the school being located in economically underdeveloped rural areas, boarding students do not receive good services such as food, accommodation, and learning, and also lack sufficient parental care and concern. In addition, schools have grouped students with varying personalities in communal boarding environments without fully considering individual differences. This practice often exacerbates conflicts among peer groups and significantly affects the mental health of rural boarding students. It is thus critical to explore the mental health problems caused by bullying and victimization in rural Chinese schools. It is also important to develop and implement interventions that are culturally and contextually appropriate to address these challenges effectively. To meet this end, this study aimed at evaluating the role of self-esteem and parenting styles between bullying victimization and Chinese boarding adolescents’ mental health, and proposed a moderated mediation model (see Fig. 1). And the following hypotheses were proposed for this study, based on the literature review:

Fig. 1.

Hypothesized model

H1

Bullying victimization can directly predict boarding adolescents’ mental health problems;

H2

Self-esteem plays a mediating role in the impact of bullying on mental health problems;

H3

Parenting styles moderate the mediating effect of self-esteem.

Methods

Participants and process

This research was reviewed and approved by the educational authorities of the research site and the authors’ University. Therefore, all the rural schools in the research city were invited to participate in this study. As a result, 2772 boarding adolescents from 84 rural schools consented to participate in this study and completed four questionnaires. According to the Mental Health Test [27], when a participant’s score on the validity scale was greater than 7, the whole answers in this test were invalid, and this case should be abandoned. In this study, there were 617 subjects with invalid answers. After excluding those invalid cases, 2155 students were involved in this study, and their data were adopted to test the hypotheses proposed in this research (effective rate 77.74%). Finally, the age range of participants in this study was 12 to 17, with an average age of 13.86 years (SD = 0.81), and there were 936 boys (43.43%) and 1219 girls (56.57%).

In this study, participants were recruited according to the principle of voluntariness and convenient sampling. After obtaining permission and informed consent from the headmasters and head teachers of the rural school, the questionnaires were administered to the boarding adolescents. Only students who were aware of the purpose of the survey and willing to participate (within formed consent) were measured. All participants were required to complete four questionnaires under the guidance of a trained researcher, who then collected the completed questionnaires.

Measures

Bullying victimization. This item was developed from Pepler’s original scale, which has two items about the degree (how often) and the frequency (how many times) of bullying victimization [28]. However, it is very challenging for students to report the frequency of bullying victimization correctly; thus, this study opted to ask participants to assess their experience of bullying victimization using only one item. Specifically, students were asked, “How often are you bullied by other classmates?” with response options ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (always). This item has been proved to be an effective measure of bullying victimization among adolescents [29].

Parenting styles. The Chinese version of Egma Minnen av Bardndosnauppforstran (EMBU-C) was used in this study. The scale was first developed by Perris [22], then was revised into a Chinese version and measured in Chinese samples [30]. EMBU-C consists of 115 items, including 58 for father and 57 for mother, and subjects were asked to respond from 1 (never) to 4 (always). The father scale includes emotional warmth, severe punishment, excessive interference, preference, rejection, and overprotection, while the mother scale includes the same five dimensions besides excessive interference. According to Chen and Liu’s research, emotional warmth was selected as positive parenting styles, and rejection and overprotection have remained as negative parenting styles [31]. Therefore, these two dimensions contain the scores of the father scale and mother scale. In this study, the overall Cronbach’s α and the subscale Cronbach’s α of the scale were 0.97, 0.95, and 0.92.

Self-esteem. The Self-Esteem Scale (SES) was originally developed by Rosenberg [13] and then revised to a Chinese version [32]. The revised SES has been proved to be suitable for Chinese youth samples. But different from the original scale, the eighth item (I think it is difficult for me to get more respect in the future) was revised to a positive score because of cultural differences [33]. There are 10 items on this scale, of which four items are scored reversely, and they are all answered according to 1 (very consistent) to 4 (very inconsistent). The higher the total score, the higher the self-esteem. In this study, Cronbach’s α of the scale was 0.86.

Mental health problems. Based on Suzuki’s anxiety test, Zhou developed a Mental Health Test (MHT) to measure Chinese children and adolescents [27]. The test has been conducted on a large scale in China, and the norm has been obtained. There are 100 items in MHT divided into nine dimensions: validity, study anxiety, anxiety about people, oneness tendency, self reproduce tendency, allergic tendency, physical symptoms, impractical tendency, and terrestrial tendency. The validity scale is not included in the total score. All items are forced to answer (1 = yes, 0 = no). When the validity score is greater than 7, the answer should be false and this sample should be discarded. When the scores of other dimensions are greater than or equal to 8, it can be judged that the subject has serious psychological problems in these dimensions. 4 to 7 means light psychological problems. Less than or equal to 3 means no such problems. Cronbach’s α in this research was 0.95 for the scale.

Common method bias and normality tests

All measurements in this study are adolescents’ self-assessment report related to the validity of the data collected. Harman single factor method was used to test whether the common method bias existed [34]. After factor analysis of all items, the results showed 64 principal components (λ > 1). The variation explained by the first principal component was only 10.74% of the total variation, which was far below the critical value of 40%. Therefore, there is no significant common bias in the current research.

The skewness and kurtosis normality test showed that the Mental Health Problems Scale had a skewness of − 0.624 and a kurtosis of 0.008. it is generally accepted that if the absolute value of the kurtosis is less than 10 and the absolute value of the skewness is less than 3, then it is basically accepted as a normal distribution.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Frequency statistics were conducted to make clear the mental health status of boarding adolescents in rural China. Results found that the overall mental health of the boarding adolescents was at a health level (see Table 1). Among them, 1731 were healthy (80.32%), 268 had general mental problems (12.44%), and 156 had serious mental problems (7.24%). However, it is worth noting that more than half of these boarding students were in serious study anxiety (1387, 64.36%), more than one-third had severe physical symptoms (835, 38.75%), and more than one-fifth had severe self-reported tendency and allergic tendency (506, 23.48%; 555, 25.75%). In other words, although the vast majority of boarding adolescents seemed to be mentally healthy in general, yet more than half of them had high-intensity academic pressure, and some shown adverse physiological reactions (such as headache, dyspnea, nightmares, etc.), mental tension and self-blame.

Table 1.

Boarding students’ scores on mental health problems test (N = 2155)

| Scores (n/%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Dimensions | =< 3 | 4 ∼ 7 | >=8 |

| Study anxiety | 280 (12.99%) | 488 (22.65%) | 1387 (64.36%) |

| Anxiety about people | 668 (31.00%) | 1172 (54.39%) | 315 (14.61%) |

| Loneliness tendency | 1059 (49.14%) | 931 (43.20%) | 165 (7.66%) |

| Self reproach tendency | 593 (27.52%) | 1056 (49.00%) | 506 (23.48%) |

| Allergic tendency | 493 (22.88%) | 1107 (51.37%) | 555 (25.75%) |

| Physical symptoms | 460 (21.35%) | 860 (39.90%) | 835 (38.75%) |

| Impulsive tendency | 955(44.32%) | 961 (44.59%) | 239 (11.09%) |

| Terror tendency | 988 (45.85%) | 1014 (47.05%) | 153 (7.10%) |

| 1 ∼ 55 | 56 ∼ 64 | >=65 | |

| Mental health problems | 1731 (80.32%) | 268 (12.44%) | 156 (7.24%) |

Further ANOVA results shown that there was significant gender difference in mental health of boarding adolescents (F = 13.44, p <.001), but there was no significant interaction effect between gender and age. Also t-test results indicated that significant gender differences did exist in the mental health of boarding adolescents (t = -11.55, p <.001; Cohen’s d = 0.97, 95% confidence intervals not including 0, lower bound − 0.59, upper bound − 0.42). Specifically, boys’ scores of mental health problems were significantly higher than that of girls (Mboy = 63.73; Mgirl = 54.91). That is, boys in boarding adolescents were facing more mental health problems.

As shown in Table 2, findings from correlation analyses proved that there was a significant positive association among bullying victimization, negative parenting styles and mental health problems (r =.19, p <.001; r =.09, p <.001), and significant negative associations between bullying victimization and self-esteem, positive parenting styles (r =–.08, p <.001; r =–.06, p <.01). In addition, self-esteem, and negative parenting styles also had correlations with mental health problems (r =–.12, p <.001; r =.08, p <.001), but the correlation between positive parenting styles and mental health is not significant (r =–.04, p >.05).

Table 2.

Means, standard deviation and correlations among study variables (N = 2155)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Bullying victimization | 1 | ||||

| 2 Self-esteem | –0.08*** | 1 | |||

| 3 Positive parenting styles | –0.06** | 0.26*** | 1 | ||

| 4 Negative parenting styles | 0.19*** | –0.04 | 0.25*** | 1 | |

| 5 Mental health problems | 0.09*** | –0.12*** | –0.04 | 0.08*** | 1 |

| M | 1.48 | 27.42 | 85.97 | 75.44 | 48.68 |

| SD | 0.64 | 3.95 | 19.77 | 16.03 | 18.05 |

Note. **p <.01, ***p <.001

Hypothesis model testing

Model 4 and Model 59 in PROCESS 3.2 were used to test the hypothesis model. After controlling for gender and age, In Table 3, the results revealed that firstly, bullying victimization could not only directly predict boarding adolescents’ mental health problems (β = 0.13, p <.001), but also indirectly predict their mental health problems through self-esteem (β = 0.01, p <.01). Furthermore, self-esteem mediated the effect of bullying victimization on mental health problems. Then, positive parenting styles had no significant effect on the relationship among bullying victimization, self-esteem, and mental health problems (p >.05). Finally, the interaction between negative parenting styles and bullying victimization could remarkably predict boarding students’ self-esteem (β = 0.07, p <.01). That is, negative parenting styles moderated the mediating effect of self-esteem (see Fig. 2).

Table 3.

Direct and indirect path analysis between bullying victimization and mental health

| Path | β | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|

| Direct effect | ||

| Bullying victimization → mental health problems | 0.13*** | [0.09, 0.18] |

| Mediating effect | ||

| Bullying victimization → self-esteem → mental health problems | 0.01** | [0.00, 0.02] |

| Moderating effects of positive rearing | ||

| Bullying victimization×positive parenting styles → self-esteem | 0.03 | [–0.01, 0.08] |

| Self-esteem×positive parenting styles → mental health problems | –0.01 | [–0.05, 0.02] |

| Bullying victimization×positive parenting styles → mental health problems | 0.02 | [–0.03, 0.06] |

| Moderating effects of negative rearing | ||

| Bullying victimization×negative parenting styles → self-esteem | 0.07** | [0.02, 0.11] |

| Self-esteem×negative parenting styles → mental health problems | –0.00 | [–0.04, 0.03] |

| Bullying victimization×negative parenting styles → mental health problems | 0.02 | [–0.02, 0.06] |

Note. **p <.01, ***p <.001

Fig. 2.

Final model in this study

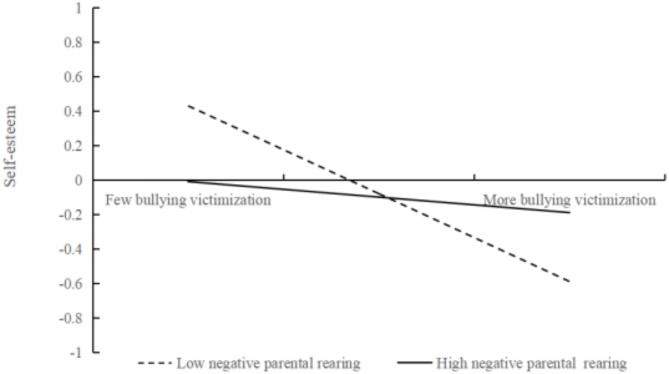

To further understand how negative parenting styles influence the relationship between bullying victimization and mental health problems, it was divided into high-level group and low-level group according to the standard deviation of plus (+ 1 SD) one and minus one (–1 SD), and the simple slope test was performed then [35]. As shown in Fig. 3, the self-esteem of the high negative group was much lower than that of the low negative group at the initial level. No matter high negative rearing level or a low level, boarding adolescents’ self-esteem gradually decreases with the increase of bullying victimization (β =–0.03; β =–0.17). However, there were differences in the decline. In the high negative rearing group, the negative predictive effect of bullying victimization on self-esteem was lower than that in the low negative rearing group (βhigh < βlow). The latter strengthened the inhibition of self-esteem.

Fig. 3.

Interaction of negative parenting styles between bullying victimization and self-esteem

Discussion

Mental health problems of Chinese boarding adolescents

In this survey, Chinese boarding adolescents are generally at a healthy level (80.32%), but most of them are facing severe academic anxiety (64.36%), and some have severe physical symptoms (38.75% ). The possible reason is that almost all of these boarding adolescents come from rural China, where the economy is relatively backward and lacks excellent educational resources [4]. The influence of imperial examinations (that is, through some selective examinations to determine whether a person is capable of becoming a government official ) on rural parents highlights the historical importance of education as a pathway to social mobility and government positions. The idea of “he who excels in a study can follow an official career” is also deeply ingrained in their minds [36]. Therefore, these adolescents have been instilled by their parents or surrounding culture since childhood; achieving excellent academic results and entering a good university is a precious opportunity or the only chance to escape poverty and lead a better life in the future [36]. However, there is a contradiction between parents’ high educational expectations and the relative lack of excellent educational resources caused by economic backwardness [36, 37]. Therefore, compared with adolescents in other rich regions, boarding adolescents in China will bear more academic pressure, become academically anxious, and even have physical symptoms.

Direct effects of bullying victimization and mental health problems in boarding adolescents

In this study, the bullying victimization significantly and positively predicted boarding adolescents’ mental health problems. That is, mental health problems become more serious as the degree of being bullied increases. This finding supports the proposed research hypothesis 1 and aligns with recent studies involving autistic and overweight adolescents [38, 39]. Furthermore, it demonstrates that the impact of bullying on adolescents’ mental health is consistent across different groups.

The most likely reason is that after being bullied, the boarding adolescents might lack the necessary support and help from various schools and families. On the one hand, although the government and the education department have issued a series of related policies to promote the mental health of Chinese primary and secondary school students, professional psychological counseling services for student growth are currently very scarce, therefore, they cannot satisfy the demand of students from boarding schools in rural China. What’s worse, many schools do not have the conditions to set up psychological counseling rooms, and there are no professional psychological counseling teachers to serve in schools [40]. On the other hand, only a very small number of adolescents would like to tell or inform their parents or teachers about their experience of being bullied at school, making it impossible to seek support from home and school timely [1]. Therefore, victims usually need to face the negative effects brought about by the negative incident of bullying on their own, including the ridicule and discrimination of their peers, which makes them extremely prone to various psychological problems, even endanger their live [41, 42].

Indirect effects between bullying victimization and mental health problems in boarding adolescents

This study found that bullying victimization also impacted boarding adolescents’ mental health problems through the indirect effects of self-esteem and negative parenting styles. In this indirect path, self-esteem played a mediating role, and negative parenting styles played a moderator role. In particular, self-esteem was a moderated mediator, and its mediating effect was significantly different at different levels of negative parenting styles. These findings are consistent with existing research results and support hypotheses 2 and 3 in this study [23].

Boarding students who suffer from school bullying tend to have lower overall self-assessments, and it is this low self-esteem causes them to have mental health problems. At the same time, negative parenting styles such as rejection, denial, and doting from parents affect the path between victimization and self-esteem. The self-esteem of boarding adolescents from the low-level negative-rearing group was higher than those from the high-level negative-rearing group when they first encountered bullying. However, as the number of bullying victims increased, low-level negative parenting styles intensified the negative predictive effect of bullying victimization on boarding students’ self-esteem, which have a detrimental influence on the relationship between bullying victimization and self-esteem. Thus, the self-esteem in this group is gradually lower than that of the high-level group. This may be related to the floor effect—individuals in the high-level negative-rearing group may already have lower self-esteem due to their more significant exposure to negative parenting. Consequently, they may not experience as sharp a decline in self-esteem when faced with bullying because their self-esteem levels are already at a lower baseline [33, 34].

This finding shows that the parenting styles of parents to their children are an extremely important role in their children’s mental health development and smooth prevention of school bullying is inseparable from family support. The reduction of negative parenting styles can cultivate children’s self-esteem and confidence, while simultaneously mitigating feelings of loneliness and difficulties in social adaptation, and thus lower the likelihood of being bullied.

Limitations and practical significance

This research has certain limitations, which need to be broken through by subsequent research. On the one hand, this study is a cross-sectional study, and it may not be possible to understand the dynamic development process of the mental health of Chinese boarding adolescents. Therefore, longitudinal research on the development of boarding students’ mental health is very urgent. On the other hand, a comparison of boarding and non-boarding students should also be considered to have a more comprehensive understanding of the impact of bullying victimization on mental health problems to propose more targeted school bullying intervention programs. Meanwhile, the limited set of control variables also constitutes a notable limitation of the research. While gender and age were included as control variables, the absence of other potentially influential factors, such as parental SES and family structure, may limit the comprehensiveness of the findings. This restricted range of control variables could potentially lead to omitted variable bias, thereby affecting the robustness and generalizability of the results. Future research would benefit from incorporating a more extensive set of control variables, including but not limited to parental income, educational attainment, occupational status, and family composition. Moreover, it is necessary to conduct in-depth research on the multi-dimensional victimization of bullying. Different types of victimization may have different effects on mental health, and the type with the greatest impact should be identified and intervened in the future.

Recommendations for countermeasures

The findings in this study provide necessary guidance for academic research and educational practice to prevent and reduce school bullying among Chinese boarding adolescents. First of all, more attention should be paid by researchers and educators to boarding adolescents’ mental health development (such as academic anxiety, physical symptoms), especially those students who have suffered bullying in school. Secondly, schools ought to attach more significance to the harmfulness of school bullying to boarding adolescents’ development, especially for victims, and afterward, psychological intervention projects are essential. Meanwhile, harmonious teacher-student relationship and a positive school culture grounded in mutual respect should be fostered, as it is a crucial school factor to lessen the frequency and the severity of school bullying. Such a culture fosters an environment where students feel valued and included, making them less likely to engage in or tolerate bullying behavior. Moreover, a positive school culture promotes a sense of belonging and community, which can act as a strong deterrent against bullying. Next, helping victims rebuild their correct self-perception and assessment is key to preventing boarding adolescents from having mental health problems. These adolescents should be convinced that it is not their fault to be bullied and they should cope with school bullying positively and strategically. Finally, parents play a non-negligible role in the fight against school bullying. The task of preventing school bullying does not belong to the school alone. Parents need to work hard to accomplish it together. Particularly with regard to the daily communication between boarding students and their parents, given that all interactions are mediated through mobile phones in the absence of direct face-to-face contact, parents should maintain a positive attitude in communicating with their children, attentively listen to their issues, assist in alleviating negative emotions, and avoid negative daily communication.

Conclusions

First, bullying victimization directly predicted the mental health problems of Chinese boarding adolescents and indirectly predicted their mental health problems through self-esteem and negative parenting styles. Second, self-esteem played a mediating role in the path from bullying victimization to mental health problems. Third, this mediating effect was moderated by negative parenting styles. Specifically, individuals who experienced bullying victimization were more likely to suffer from low self-esteem, which in turn led to mental health problems. However, when negative parenting styles were present, this mediating effect of bullying victimization on self-esteem was exacerbated, resulting in a higher risk of low self-esteem. In fact, negative parenting styles act as a catalyst between bullying victimization and decreased self-esteem. Specifically, both low and high levels of negative parenting styles are detrimental factors in the relationship between bullying victimization and decreased self-esteem. In other words, children who were both bullied and exposed to negative parenting styles were at a higher risk of developing severe mental health issues.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Dear Zhao Hongxia of the Normal College of Jimei University for her unwavering support and encouragement throughout the entire research process. Dr. Zhao’s visionary leadership not only provides us with a nurturing academic environment, but also inspires us to break through the boundaries of knowledge in our field. Her constant encouragement and valuable insights help us determine the direction of our work and ensure its successful completion.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Writing-original draft, data analysis were performed by Chen xu. Writing-review, editing were performed by Chen Jing and Jiang Huijuan. Resources, Supervision were performed by Zhao Hongxia and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The research leading to these results received funding from The Key Project of the “National Office for Education Sciences Planning” Research on Interpersonal Adaptation Barriers and Psychological Interventions for Hong Kong, Macao, Taiwan, and Overseas Chinese Students Based on Cultural Identity Theory under Grant Agreement No WBZ230531 and The Special Project of the“Fourteenth Five Year Plan”of Fujian Education Science“Research on the Heterogeneity of Campus Bullying Groups Based on Role Categories” under Grant Agreement No Q202225.

Data availability

The data is confidential. If necessary, please contact the corresponding author to request it.(Email: hxzhao@jmu.edu.cn).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The questionnaire and methodology for this study was approved by the Human Research Ethics committee of the Jimei University. All participants involved in this manuscript, including those classified as minors (individuals under the age of 16), have obtained the requisite informed consent from their respective parents or legally appointed guardians. This consent process is essential for ensuring ethical compliance and safeguarding the rights and well-being of all underage participants, in strict adherence to the guidelines and regulations governing such research activities.

Accordance

Our study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, which serves as a fundamental guide for medical research involving human participants. We also complied with the appropriate national research guidelines and regulations applicable to our study. All research procedures were reviewed and approved by the Normal College of Jimei university, ensuring that the rights, safety, and well-being of participants were protected throughout the study.

Consent for publication

It refers to consent for the publication of identifying images or other personal or clinical details of participants that compromise anonymity. And this is not applicable to our manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Luo R, Shi Y, Zhang L, Liu C, Rozelle S, Sharbono B. Malnutrition in China’s rural boarding schools: the case of primary schools in Shaanxi Province. Asia Pac J Educ. 2009;29(4):481–501. 10.1080/02188790903312680 [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNICEF. Education and child development. 2017. https://www.unicef.cn/figure-820-number-boarding-students-primary-and-junior-secondary-education-2017

- 3.Fredrick SS, McClemont AJ, Jenkins LN, Kern M. Perceptions of emotional and physical safety among boarding students and associations with school bullying. School Psychol Rev. 2021. 10.1080/2372966X.2021.1873705 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yin XQ, Wang LH, Zhang GD, Liang XB, Li J, Zimmerman MA, Wang JL. The promotive effects of peer support and active coping on the relationship between bullying victimization and depression among Chinese boarding students. Psychiatry Res. 2017;256:59–65. 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.06.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang YD, Liu SH. What factors have more influence on the deviant behavior of rural Boarders? Ranking the importance of variables based on random forest. Educ Econ. 2024;40(05):21–8. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeongyeon S, Ja YG. The influence of adolescents’ life satisfaction, and perceived parenting styles on adolescents’ depression: verification of mediating effect of resilience. J Family Relations. 2017;22(2):27–50. 10.21321/jfr.22.2.27 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bronfenbrenner U. Citation Classic - Toward an experimental ecology of human development. Current Contents/Social & Behavioral Sciences. 1983;27:24–24.

- 8.Lee J. Pathways from childhood bullying victimization to young adult depressive and anxiety symptoms. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2021;17(3):e779. 10.1007/s10578-020-00997-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malaeb D, Awad E, Haddad C, Salameh P, Sacre H, Akel M, Soufia M, Hallit R, Obeid S, Hallit S. Bullying victimization among Lebanese adolescents: the role of child abuse, internet addiction, social phobia and depression and validation of the Illinois bully scale. BMC Pediatr. 2020;20(1):e520. 10.1186/s12887-020-02413-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oexle N, Ribeiro W, Fisher HL, Gronholm PC, Laurens KR, Pan P, Owens S, Romeo R, Rüsch1 N, EvansLacko S. Childhood bullying victimization, selflabelling, and helpseeking for mental health problems. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2020;55(1):81– 88. 10.1007/s00127-019-01743-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lyyra N, Thorsteinsson EB, Eriksson C, Madsen KR, Tolvanen A, Löfstedt P, Välimaa R. The association between loneliness, mental well-being, and self-esteem among adolescents in four nordic countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:e7405. 10.3390/ijerph18147405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bannink R, Broeren S, van de Looij-Jansen PM, de Waart FG, Raat H. Cyber and traditional bullying victimization as a risk factor for mental health problems and suicidal ideation in adolescents. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(4):e94026. 10.1371/journal.pone.0094026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press; 1965.

- 14.Lee HG, Chul JJ. Relationship among physical activity, self-esteem, depression and suicidal ideation of youth. Korean Soc Sports Sci. 2018;27(4):389– 398. 10.35159/kjss.2018.08.27.4.389 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duan CB, Zhou H, Jiang Y, Zhu HY, Wang T, Huang XH, Jian DW. Attentional bias to aggressive words under self-threat priming in college students with different types of high self-esteem. Chin Mental Health J. 2024;38(05):452–7. (in Chinese, no DOI). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu XF, Huebner ES, Tian LL. Profiles of narcissism and self-esteem associated with comprehensive mental health in adolescents. J Adolesc. 2020;80:275– 387. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeHart T, Pelham BW. Fluctuations in state implicit self-esteem in response to daily negative events. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2007;43(1):157– 165. 10.1016/j.jesp.2006.01.002 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tetzner J, Becker M, Baumert J. Still doing fine? The interplay of negative life events and self-esteem during young adulthood. Eur J Pers. 2016;30(4):358– 373. 10.1002/per.2066 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi B, Park S. Bullying perpetration, victimization, and low self-esteem: examining their relationship over time. J Youth Adolesc. 2021;50(4):739– 752. 10.1007/s10964-020-01379-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Geel M, Goemans A, Zwaanswijk W, Gini G, Vedder P. Does peer victimization predict low self-esteem, or does low self-esteem predict peer victimization? Meta-analyses on longitudinal studies. Dev Rev. 2021;49:31–40. 10.1016/j.dr.2018.07.001 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhong MT, Huang XC, Huebner ES, Tian LL. Association between bullying victimization and depressive symptoms in children: the mediating role of self-esteem. J Affect Disord. 2021;294:322– 328. 10.1016/J.JAD.2021.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perris C, Jacobsson L, Linndström H, Knorring L, Perris H. Development of a new inventory for assessing memories of parenting styles behaviour. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1980;61(4):265– 274. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1980.tb00581.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wei YH. A study on the influence of parenting styles on the development of children’s self-esteem. Psychol Dev Educ. 1999;3:7–11. (in Chinese, no DOI). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang L, Tian J, Rozelle S. Parenting style and child mental health at preschool age: evidence from rural China. BMC Psychiatry. 2024;24: e314. 10.1186/s12888-024-05707-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blau B, Blau P. Identity status, separation, and parent-adolescent relationships among boarding and day school students. Residential Treat Child Youth. 2021;38(2):178– 197. 10.1080/0886571X.2019.1692757 [Google Scholar]

- 26.REAP. Educational challenges—boarding schools. Rural education action program Stanford University. 2019. Accessed at reap. fsi.stanford.edu/docs/boarding_schools.

- 27.Zhou BC. Handbook of mental health test. East China Normal University; 1991.

- 28.Pepler D, Jiang D, Craig W, Connolly J. Developmental trajectories of bullying and associated factors. Child Dev. 2008;79:325– 338. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01128.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nepon T, Pepler DJ, Craig WM, Connolly J, Flett GL. A longitudinal analysis of peer victimization, self-esteem, and rejection sensitivity in mental health and substance use among adolescents. Int J Mental Health Addict. 2021;19:1135– 1148. 10.1007/s11469-019-00215-w [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yue DM, Li MG, Jin KH, Ding BK. Parenting styles: the preliminary revision of EMBU and its application in neurotic patients. J Chin Mental Health. 1993;3:97–101. (in Chinese, no DOI). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen HB, Liu J. The relationship between family socioeconomic status and adolescents’ wisdom: the mediating role of active parenting and open personality. Psychol Dev Educ. 2018;34(5):558– 566. (in Chinese, no DOI). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tian LM. The shortcomings of the Chinese version of Rosenberg's (1965) self-esteem scale.Psychological Exploration. 2006;(02):88–91.(in Chinese).

- 33.Shen ZL, Cai TS. Treatment of item 8 of the Chinese version of the Rosenberg self-esteem scale. Chin J Mental Health. 2008;9:661–663. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; 1991.

- 36.Yang YS. The status quo and thinking of the rural middle school curriculum reform. Contemp Educ Forum. 2004;7:126– 127. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 37.An YJ. The flow of students, the reorganization of educational resources and the imbalance of urban-rural compulsory education: based on a case study of N County, Gansu. J Beijing Univ Technol. 2021;21(5):39–47. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodriguez G, Drastal K, Hartley SL. Cross-lagged model of bullying victimization and mental health problems in children with autism in middle to older childhood. Autism. 2021;25(1):90–101. 10.1177/1362361320947513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sahin N, Kirli U. The relationship between peer bullying and anxiety-depression levels in children with obesity. Alpha Psychiatry. 2021;22(2):94– 99. 10.5455/apd.133514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang CP, Ren TW. Investigation and analysis of the current situation of rural junior high school students’ psychological counseling needs. Teach Manage. 2012;33:79–81. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arango A, Opperman KJ, Gipson PY, King CA. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among youth who report bully victimization, bully perpetration and/or low social connectedness. J Adolesc. 2016;51:19–29. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bauman S, Toomey RB, Walker JL. Associations among bullying, cyberbullying, and suicide in high school students. J Adolesc. 2013;36(2):341– 350. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data is confidential. If necessary, please contact the corresponding author to request it.(Email: hxzhao@jmu.edu.cn).