Abstract

Objectives:

Veterans of the 1991 Gulf War (GW) were exposed to a myriad of potentially hazardous chemicals during deployment. Epidemiological data suggest a possible link between chemical exposures and Parkinson’s disease (PD); however, there have been no reliable data on the incidence or prevalence of PD among GW veterans to date. This study included the following 2 questions: 1. Do deployed GW veterans display PD-like symptoms? and 2. Is there a relationship between the occurrence and quantity of PD-like symptoms, and the levels of deployment-related exposures in GW veterans?

Material and Methods:

Self-reports of symptoms and exposures to deployment-related chemicals were filled out by 293 GW veterans, 202 of whom had undergone 3 Tesla volumetric measurements of basal ganglia volumes. Correlation analyses were used to examine the relationship between the frequency of the veterans’ self-reported exposures to deployment-related chemicals, motor and non-motor symptoms of PD, and the total basal ganglia volumes.

Results:

Healthy deployed GW veterans self-reported few PD-like non-motor symptoms and no motor symptoms. In contrast, GW veterans with Gulf War illness (GWI) self-reported more PD-like motor and non-motor symptoms, and more GW-related exposures. Compared to healthy deployed veterans, those with GWI also had lower total basal ganglia volumes.

Conclusions:

Although little is known about the long-term consequences of GWI, findings from this study suggest that veterans with GWI show more symptoms as those seen in PD/prodromal PD, compared to healthy deployed GW veterans. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2019;32(4):503 – 26

Keywords: occupational exposure, pesticides, chemical exposure, Parkinson’s disease, basal ganglia, Gulf War

INTRODUCTION

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most common age-related neurodegenerative disorder, preceded only by Alzheimer’s disease [1]. There are 2 forms of PD: familial PD, which is caused by a number of single gene mutations (e.g., α-synuclein, ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase L1 [UCH-L1], parkin, leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 [LRRK 2], PTEN-induced kinase 1 [PINK 1], and DJ-1 genes [2]), and sporadic PD, which accounts for most PD cases. Although the exact cause of sporadic PD remains elusive, epidemiological studies have implicated environmental exposures to chemicals such as pesticides and polychlorinated biphenyls in an increased risk of PD [3].

Many toxic chemicals were present in the 1991 Gulf War (GW) environment, including pesticides, low levels of chemical warfare agents released by the destruction of Iraqi munition facilities, depleted uranium munitions, and airborne contaminants from the Kuwaiti oil well fires [4]. Although the specific exposures among individual soldiers were most likely varied [4,5], these deployment-related exposures have been suspected of contributing to the chronic symptomatic illness that affects an estimated 25–32% of the nearly 700 000 U.S. GW veterans [4,6–9]. The symptomatic illness, referred to as Gulf War illness (GWI), typically includes some combinations of persistent fatigue, widespread pain, memory and concentration problems, and mood disturbances [5].

This study has investigated whether the deployed GW veterans developed PD-like symptoms because some epidemiological studies suggest that environmental chemical exposures are associated with an increased risk of PD [3], and there were a number of toxic chemicals present in the GW milieu [4,5]. It is a well-known fact that some GW soldiers were exposed to high levels of pesticides and insect repellants [10,11], many of which have been linked to an increased risk of PD (Table 1). Therefore, this study has also examined the relationship between the occurrence and quantity of PD-like symptoms and the levels of deployment-related exposures in GW veterans.

Table 1.

Pesticides used by Gulf War veterans during deployment and their relation to the Parkinson’s disease risk in the study of Gulf War veterans (N = 293) recruited in 2002–2017

| Pesticide | Active ingredient | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| General use pesticides | ||

| repellants | DEET 33% cream/stick or DEET 75% liquid permethrin 0.5% (P) spray | Furlong et al. [75] |

| area spray | d-phenothrin 0.2%(P) aerosol | |

| fly bait crystals | methomyl 1% (C) azamethiphos 1% (OP) | Gatto et al. [76] |

| pest strip | dichlorvos 20% (OP) | Narayan et al. [77] |

| Field use pesticides | ||

| spray liquids (emulsifiable concentrates) | chlorpyrifos 45% (OP) | Freire and Koifman [78] |

| diazinon 48% (OP | Gatt et al. [76] | |

| malathion 57% (OP) | Narayan et al. [77] | |

| propoxur 14.7% (C) | Firestone et al. [79] | |

| sprayed powder | bendiocarb 76% (C) | Wechsler et al. [80] |

| ultra-low volume fogs | chlorpyrifos 19% (OP) | Freire and Koifman [78] |

| malathion 91% (OP) | Gatto et al. [76] | |

| Narayan et al. [77] | ||

| Firestone et al. [79] | ||

| Delousing pesticide | ||

| delousing agent | lindane 1% (OC) | Corrigan et al. [81] |

| Pesticide-treated uniforms, tents, bedding, insect netting | ||

| repellant/permethrin | permethrin (P) | Furlong et al. [75] |

Adapted from Winkenwerder W. [10].

C – carbamate; OC – organochlorine; OP – organophosphate; P – pyrethroid.

Unfortunately, there have been no reliable data on the incidence or prevalence of PD among GW veterans to date [4]. While a handful of studies have examined GW veterans’ health longitudinally, they have not specifically inquired about neurological conditions such as PD [12,13]. One longitudinal study concluded that GW veterans did not display higher mortality rates due to PD compared to non-deployed veterans [14]. However, it did not take into account the potential cases of GW veterans currently living with PD or prodromal PD.

There is converging evidence from clinical, neuropathological and imaging research that the initiation of PD-specific pathology occurs prior to the occurrence of the “classical” motor symptoms of PD [15], which include resting tremor, bradykinesia (i.e., slowness of movement), rigidity, and postural instability (i.e., problems with standing or walking, or impaired balance and coordination). It is noteworthy that there have been reports of postural instability in > 50% of GW veterans with “medically unexplained symptoms” (i.e., GWI) compared to only 10% of healthy controls [16,17]. In addition to motor symptoms, PD is also associated with a variety of non-motor symptoms that can precede the occurrence of the classical motor features in PD, sometimes by decades [18,19]. Interestingly, many symptoms of GWI are similar to the non-motor symptoms of PD. Table 2 summarizes the similarities between the symptoms queried by the Non-Motor Symptom (NMS) Scale for Parkinson’s Disease [20] and GWI symptoms.

Table 2.

Similarities between the non-motor symptoms (NMS) in Parkinson’s disease (PD) and Gulf War Illness (GWI) symptoms in the study of Gulf War veterans (N = 293) recruited in 2002–2017

| Non-motor symptom of PD | Symptom presence in GWI |

|---|---|

| Domain 1. Cardiovascular, including falls | |

| orthostatic hypotension (i.e., light-headedness on standing from sitting or lying position); falls due to fainting or blacking out | Davis et al. [82] reported a higher incidence of neurally mediated hypotension in fatigued |

| GW veterans compared to unfatigued controls | |

| Rayhan et al. [83] reported that exercise challenge induced orthostatic tachycardia in a subgroup of veterans with GWI | |

| Haley et al. [84] reported that GW veterans who met any of the 3 syndrome criteria had higher self-reports of orthostatic intolerance | |

| feeling dizzy, lightheaded or faint is a symptom of the Kansas GWI case definition [9] there have been anecdotal reports of fainting or blacking out from veterans with GWI | |

| Domain 2. Sleep/fatigue | |

| dozing off or falling asleep unintentionally during daytime activities | anecdotal reports from veterans participating in the Veterans Affairs-funded (VA- funded) clinical trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBTi) for veterans with GWI reported in a recent meta-analysis of GW veterans’ self-reported health symptoms [85] |

| fatigue or lack of energy that limits daytime activities | symptom in both Kansas GWI (KGWI) [9] and CDC CMI [6] case definitions |

| reported in a recent meta-analysis of GW veterans’ self-reported health symptoms [85] | |

| difficulties falling or staying asleep | symptom in both KGWI [9] and CDC CMI [6] case definitions |

| reported in a recent meta-analysis of GW veterans’ self-reported health symptoms [85] | |

| urge to move legs or restlessness in legs that improves with movement when the patient is sitting or lying down inactive | anecdotally, many GW veterans have restless legs syndrome (RLS): 12% of GW veterans were excluded from our Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia clinical trial because of high scores on RLS screening questionnaire [86] |

| Domain 3. Mood/cognition | |

| lost interest in surroundings, in doing things, or lack of motivation to start new activities | |

| feeling nervous, worried, or frightened for no apparent reason | symptom of the CDC CMI [6] case definition |

| reported in recent meta-analysis of GW veterans’ self-reported health symptoms [85] | |

| feeling sad or depressed | symptom in both KGWI [9] and CDC CMI [6] case definitions |

| reported in a recent meta-analysis of GW veterans’ self-reported health symptoms [85] | |

| flat moods; difficulty experience pleasure from usual activities | |

| Domain 4. Perceptual problems/hallucinations | |

| hallucinations and/or delusions | |

| experience double vision | symptom of the KGWI case definition [9] |

| Domain 5. Attention/memory | |

| problems sustaining concentration | symptom in both KGWI [9] and CDC CMI [6] case definitions |

| reported in a recent meta-analysis of GW veterans’ self-reported health symptoms [85] | |

| problems remembering recent information | symptom in both KGWI [9] and CDC CMI [6] case definitions |

| reported in a recent meta-analysis of GW veterans’ self-reported health symptoms [85] | |

| forgets to do things | reported in a recent meta-analysis of GW veterans’ self-reported health symptoms [85] |

| Domain 6. Gastrointestinal tract | |

| dribbles saliva during the day | |

| difficulty swallowing | reported by Hallman et al. [87] in the Gulf War Health Registry cohort |

| constipation | reported in a recent meta-analysis of GW veterans’ self-reported health symptoms [85] |

| Domain 7. Urinary dysfunction | |

| urgency; frequency; nocturia | Haley et al. [84] reported that GW veterans who met any of the 3 syndrome criteria had higher self-reports of urinary dysfunction |

| there are anecdotal reports of nocturia from GW veterans participating in the Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia clinical trial | |

| Domain 8. Sexual dysfunction | |

| altered interest in sex or problems having sex | male sexual dysfunction noted in GW veterans with the Haley syndrome [84] female sexual dysfunction noted in GW veterans with chronic fatigue [88] |

| reported in a recent meta-analysis of GW veterans’ self-reported health symptoms [85] | |

| Domain 9. Miscellaneous | |

| unexplained pain | symptom in both KGWI [9] and CDC CMI [6] case definitions |

| reported in a recent meta-analysis of GW veterans’ self-reported health symptoms [85] | |

| change in the ability to taste or smell | anecdotal reports from veterans suffering from GWI |

| excessive sweating | night sweats are a symptom of KGWI case definition [9] |

| reported in a recent meta-analysis of GW veterans’ self-reported health symptoms [85] | |

CDC CMI – Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Chronic Multisymptom Illness [6].

The authors conducted secondary analyses on the data obtained from a convenience sample of 293 GW veterans used in previous studies to address the following 2 questions: 1. Does GW deployment increase a veteran’s risk of developing PD-like symptoms? 2. Are GW veterans with high levels of deployment-related exposures more likely to show PD-like symptoms than veterans with low levels of deployment-related exposures? The gold standard for studying the exposure outcome relationships requires the demonstration of a dose-effect relationship and a biological or environmental measure of the actual exposure dose. Unfortunately, there are very few measured data indicating which GW veteran was exposed to which agent during the GW, and at what levels [4,5]. Therefore, the authors relied on the veterans’ self-reports of deployment-related experiences to assess GW-related exposures, as many epidemiological studies of GWI had previously done [5,6,8,9,21]. Characteristics suggestive of PD-like motor (i.e., tremors and/or shaking) and non-motor [20] symptoms were also quantified by self-reports. Finally, because the neurons in the substantia nigra (located in the midbrain) degenerate progressively in PD, triggering a cascade of functional changes in the basal ganglia [22], the authors examined the total basal ganglia volumes in a subgroup of the sample that had undergone 3 Tesla (3T) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) procedures.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study sample

The study sample consisted of 293 GW veterans who were recruited in 2002–2017 at the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center (SF VAMC) as part of studies funded by the Departments of Defense (DOD) and Veterans Affairs (VA) to examine the effects of exposure to the Khamisiyah plume [23,24] on brain structure and function. Written informed consent, approved by the University of California, San Francisco and the SF VAMC Institutional Review Boards, was obtained from all the participants.

In the sample, 231 (79%) veterans met the case definition for “chronic multisymptom illness” (CMI), as defined by Fukuda et al. [6] at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). This definition, sometimes referred to as the CDC case definition, requires veterans to endorse ≥ 1 symptoms that have been ongoing for at least 6 months in 2 out of 3 symptom categories, including: fatigue, musculoskeletal pain (e.g., joint pain/stiffness, muscle pain), and mood-cognitive problems (e.g., feeling depressed, moody, anxious, having trouble sleeping, difficulty remembering or concentrating, trouble with word finding) [6].

The Kansas GWI (KGWI) criteria [9], which require veterans to endorse moderately severe or multiple chronic symptoms in at least 3 out of 6 defined symptom domains (i.e., fatigue/sleep problems, somatic pain, neurologic/cognitive/mood symptoms, gastrointestinal symptoms, respiratory symptoms, and skin abnormalities), were met by 122 (42%) veterans. Qualifying symptoms had to persist for the 6-month period preceding the study. Additionally, veterans were excluded as KGWI cases if they reported being diagnosed with medical or psychiatric conditions that could explain their symptoms or interfere with their ability to report them. Veterans who did not meet the CDC CMI or KGWI case definitions, and who did not have KGWI exclusionary condition(s), were considered “healthy.” Table 3 summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of the study sample.

Table 3.

Demographic, military and clinical characteristics in the study of Gulf War veterans (N = 293) recruited in 2002–2017

| Variable | Participants | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| total (N = 293) |

with KGWI (N = 122, 42%) |

with CMI (N = 231, 79%) |

controls (N = 48, 16%) |

|

| Age [years] (M±SD) | 55.5±8.9 | 52.8±7.9c | 54.8±8.7 | 57.3±8.7 |

| Education [years] (M±SD) | 15.0±2.4 | 14.3±2.2c | 14.6±2.3c | 16.4±2.3 |

| Sex [n (%)] | ||||

| males | 246 (84) | 102 (84) | 192 (83) | 42 (87) |

| females | 47 (16) | 20 (16) | 39 (17) | 6 (13) |

| Race [n (%)] | ||||

| white | 212 (72) | 82 (67) | 159 (69) | 40 (83) |

| black | 26 (9) | 13 (11) | 21 (9) | 4 (8) |

| other | 55 (19) | 27 (22) | 51 (22) | 4 (8) |

| GW military characteristics | ||||

| officer during GW [n (%)] | 64 (22) | 14 (12)c | 37 (16)c | 21 (44) |

| branch of service [n (%)] | ||||

| army | 168 (57) | 72 (59) | 138 (60) | 21 (44) |

| marines | 48 (16) | 24 (20) | 37 (16) | 11 (23) |

| air force | 31 (11) | 12 (10) | 24 (10) | 5 (10) |

| navy | 46 (16) | 14 (12) | 32 (14) | 11 (23) |

| Type of service [n (%)] | ||||

| active duty | 215 (73) | 98 (80) | 174 (75) | 33 (69) |

| reserves | 59 (20) | 18 (15) | 41 (18) | 14 (29) |

| National Guard | 19 (7) | 6 (5) | 16 (7) | 1 (2) |

| Khamisiyah Plume Exposure [n (%)] | 104 (35) | 47 (39) | 84 (36) | 13 (27) |

| Served in Iraq or Kuwait [n (%)] | 196 (67) | 84 (69) | 162 (70)c | 26 (54) |

| Comorbiditiesa [n (%)] | 126 (43) | 55 (45)c | 113 (49)c | 9 (19) |

| current PTSD | 43 (15) | 24 (20)c | 43 (19)c | 0 (0) |

| current MDD | 33 (11) | 18 (15)c | 33 (14)c | 0 (0) |

| alcohol history | 93 (32) | 35 (29) | 82 (36)c | 7 (15) |

| substance history | 27 (9) | 10 (8) | 20 (9) | 6 (13) |

| History of TBIb [n (%)] | ||||

| improbable | 105 (52) | 45 (48) | 68 (45) | 32 (76) |

| possible | 49 (24) | 25 (27) | 43 (29) | 3 (7) |

| mild | 46 (23) | 23 (25) | 39 (26) | 6 (14) |

| moderate | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) |

CMI – chronic multisymptom illness; KGWI – Kansas Gulf War illness; MDD – major depressive disorder; PTSD – posttraumatic stress disorder.

At least ≥ 1 of the psychiatric diagnoses listed below.

Data available for 202 GW veterans.

Different from controls: p ≤ 0.03.

Kansas Gulf War Military History and Health Questionnaire

The Kansas Gulf War Military History and Health Questionnaire [9] was used to obtain information about the veterans’ symptoms and medical conditions to classify them as CDC CMI and KGWI cases, to determine the number of PD-like symptoms, and to obtain information about the veterans’ GW-related exposures and experiences. The questionnaire, developed based on health and exposure questions, representative of those used in previous large population-based surveys of GW veterans [6,8,9,21], inquires about the veterans’ military and demographic characteristics, health and medical histories, when they first arrived in and finally departed from the Gulf region, the locations in which they served during the GW, and specific experiences or exposures of interest during GW deployment. The focus groups employed in the development of the questionnaire revealed that military personnel were typically not in the position to know the specific types of chemicals to which they were exposed. Therefore, the questionnaire asks veterans about specific GW experiences (e.g., coming into contact with destroyed enemy vehicles, which is an experience required for nearly all personnel directly exposed to spent depleted uranium) instead of exposures to a particular substance (e.g., depleted uranium) [5]. The symptom and exposures portions of the questionnaire can be considered using a Likert scale (i.e., 0 for no symptoms, 1 for mild symptoms, 2 for moderate symptoms, and 3 for severe symptoms; 0 for no exposure, 1 for 1–6 days of exposure, 2 for 7–30 days of exposure, and 3 for > 30 days of exposure).

There is evidence that many of the GW-related exposures are highly intercorrelated [25,26]. Moreover, studies that have assessed the myriad of GW-related exposures without controlling for the confounding effects of concurrent exposures have tended to report that nearly all of the GW-related experiences queried are linked to poor health outcomes in GW veterans [27,28]. In contrast, studies that have accounted for the effects of concurrent exposures have identified only a limited number of significant risk factors for GWI [5,29–31].

Gulf War-exposure indices

To avoid the confounding effects of intercorrelated, concurrent exposures, and to reduce the number of individual comparisons, the authors created 2 GW-exposure indices for data analysis in the present study. The first index was based on the work by Nisenbaum et al. [30], who, in a survey of 1002 GW veterans from 4 Air Force units, reported that severe and mild-moderate CDC CMI were positively associated with self-reported pyridostigmine bromide (PB) use, a carbamate that was given prophylactically to protect troops against nerve agent exposure during deployment [4,32], insect repellant use, and belief in a threat from biological or chemical weapons. Thus, the exposure index proposed by Nisenbaum was generated by summing the veterans’ responses to questions about the frequency of using PB pills, cream or liquid and/or powdered pesticides on their skin, and whether or not they had any experiences, while in the Persian Gulf region, that led them to believe they might have been exposed to chemical agents (0 = no; 1 = yes).

The second index was based on the work by Steele et al. [5] who found, in a survey of 304 GW veterans (144 KGWI cases and 160 controls), that the risk of KGWI was significantly associated with self-reported PB pill use and proximity to SCUD missile explosions among forward-deployed GW veterans (i.e., those who served in Iraq and Kuwait), and with self-reported use of pesticide-treated uniforms, which was significantly correlated with the use of pesticides on skin among GW veterans who remained in support areas (i.e., not Iraq or Kuwait). Therefore, the exposure index proposed by Steele was derived by summing the responses to questions about the frequency of taking PB and being within 1 mile of an exploding SCUD missile among the veterans who reported serving in Iraq and/or Kuwait, and by summing the responses to questions about the frequency of wearing pesticide-treated uniforms, using cream or liquid and/or powdered pesticides on skin among the veterans who did not report serving in Iraq and/or Kuwait.

While other risk factors have been identified for GWI [29,31], the authors did not base the exposure indices on these studies because they lacked information about whether the veterans surveyed had been stationed in northeastern Saudi Arabia on the fourth day of the air war [29], or if they had been seen in a clinic while they were in the Gulf region [31], and also because the authors did not have the necessary data to categorize GW veterans by the Haley syndrome [29] or the levels of general psychological distress [31].

Assessment of PD-like symptoms

The veterans’ self-reported number of PD-like symptoms, which were categorized as motor (i.e., tremors and/or shaking) and non-motor in nature, were assessed with the symptom portion of the Kansas Gulf War Military History and Health Questionnaire [9]. The authors used the domains from the Non-Motor Symptoms (NMS) Scale for Parkinson’s Disease [20] to quantify PD-like non-motor symptoms. These included feeling dizzy, light-headed or faint (NMS Domain 1), fatigue, problems getting to or staying asleep (NMS Domain 2), feeling down or depressed, feeling anxious (NMS Domain 3), blurred or double vision (NMS Domain 4), difficulty concentrating, difficulty remembering recent information (NMS Domain 5), pain in joints, muscles, or pain all over the body, and night sweats (NMS Domain 9).

Clinical assessments

All the veterans surveyed were evaluated by a Ph.D. level psychologist with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Diagnosis (SCID) [33] to diagnose the current major depressive disorder (MDD), and to rule out the individuals with a lifetime history of psychotic or bipolar disorders and alcohol or drug abuse or dependence within the previous 12 months. An interview version of the Life Stressor Checklist-Revised [34], which assesses 21 stressful life events (e.g., experiencing or witnessing serious accidents, illnesses, sudden death, and physical and sexual assault), was used to determine exposure to traumatic events. The Clinician Administered Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Scale (CAPS) [35] was used to diagnose the current posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

A group of 202 veterans, recruited in 2014–2017 for a VA-funded study, were also assessed with the Ohio State University Traumatic Brain Injury Identification (OUS TBI-ID) method to capture the severity of their lifetime history of TBI [36,37].

The 3T magnetic resonance imaging data acquisition and processing

The 3T structural MRI data that consisted of a 3D T1-weighted multi-echo Magnetization Prepared Rapid Gradient Echo (ME-MPRAGE: TR/TE/TI = 2500/2.98/1100 ms, 1 mm3 isotropic imaging voxels), and a 3D T2-weighted turbo spin-echo sequence (TR/TE = 3400/402 ms, 1 mm3 isotropic imaging voxels), which was used to calculate intracranial volume (ICV), were acquired and processed for the 202 veterans recruited in 2014–2017 for a VA-funded study.

Freesurfer version 5.1 was used to label cortical and subcortical tissue classes and derive quantitative estimates of the regional brain volume [38–40]. Freesurfer spatially normalizes each cortical surface to a template cortical surface, allowing for the automatic parcellation of the cortical surface [41]. Freesurfer also performs an automatic subcortical segmentation of the non-cortical voxels in the normalized brain volume to subcortical labels. The basal ganglia volume was derived by combining the subcortical segmentation of the caudate, putamen, and globus pallidus. Because the authors had no a priori hypotheses about laterality, the volumes of the left and right basal ganglia were combined into a single measure.

Statistical analyses

To determine whether the presence of PD-like symptoms was associated with having been deployed to the GW or with having KGWI/CMI, healthy veterans (i.e., not representing CMI or KGWI cases, and showing no KGWI exclusionary condition[s]) were compared with KGWI and CMI cases. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to examine differences between continuous variables, and χ2 tests were used to examine differences between dichotomous variables. Although the symptom portion of the Kansas Gulf War Military History and Health Questionnaire inquires about the severity of a symptom (if it is present), for the sake of simplicity, the authors only considered the absence or presence of PD-like motor symptoms (i.e., tremors and/or shaking) and non-motor symptoms. Because a given motor symptom was operationalized as a binary variable (either present or absent), group differences were analyzed with a χ2 test. Because the number of non-motor PD-like symptoms could range 0–10, the Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to analyze group differences.

The basal ganglia volume was adjusted for intracranial volume according to the following formula:

| (1) |

where:

BGa – the adjusted basal ganglia volume,

BGraw – the raw basal ganglia volume,

β – the slope of the regression line between ICV and the basal ganglia volume,

ICVraw i – the individual’s raw ICV,

ICVmean – the mean ICV of the study sample.

An analysis of covariance was used to examine group differences in the adjusted basal ganglia volumes controlling for age, sex, a history of TBI severity, and a number of psychiatric comorbidities. Finally, Spearman’s rank order correlations were used to examine the relationship between the GW-exposure indices and the number of PD-like motor and non-motor symptoms endorsed by the veterans.

Post-hoc analysis 1

Because only a small subgroup (24%) of veterans self-reported PD-like motor symptoms, in post-hoc analyses, the authors examined demographic, clinical, or military differences between the veterans who endorsed PD-like motor symptoms versus those who did not, using the Wilcoxon rank sum and χ2 tests. Finding that the veterans with PD-like motor symptoms also had larger GW-exposure indices than the veterans without motor symptoms prompted the authors to further explore the differences in the individual GW-related exposures queried by the Kansas Gulf War Military History and Health Questionnaire. A Bonferroni adjustment (α = 0.05/14 exposures of interest) was used for these comparisons.

Post-hoc analysis 2

Because the gold standard for studies of the exposure outcome relationships is to demonstrate a dose-effect relationship with a biological or environmental measure of the actual exposure dose, and because the DOD has attempted to estimate military personnel’s exposures to oil well fire smoke [42] and to low levels of sarin and cyclosarin from the demolition operations at Khamisiyah, Iraq [24], in the second post-hoc analysis, the authors examined the relationship between the number of PD-like motor and non-motor symptoms with DOD estimates of exposures to oil well fire smoke (N = 81 in the present sample) and the cumulative dosage of exposure to the Khamisiyah plume (N = 100 in the present sample; 4 veterans, for some reason, were not identified in initial data collections when the last plume modeling effort occurred in 2002, but were later identified as having been with the units that were in the hazard area; therefore, they did not have the cumulative exposure level estimates).

RESULTS

Table 3 summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of the study sample. Demographically, KGWI cases were younger (Wilcoxon W = 9528.5, Z = 3.13, p = 0.002), less educated (Wilcoxon W = 9050.0, Z = 4.89, p < 0.001), and less likely to have been officers during the GW (χ2 = 21.95, df = 1, p < 0.001) than healthy veterans. Chronic multisymptom illness cases were marginally younger (Wilcoxon W = 31 777.5.0, Z = 1.92, p = 0.05), less educated (Wilcoxon W = 30 605.0, Z = 4.21, p < 0.001), less likely to have been officers (χ2 = 15.47, df = 1, p < 0.001), and more likely to have served in Iraq or Kuwait (χ2 = 4.61, df = 1, p = 0.03) during the GW than healthy veterans. Clinically, KGWI (Wilcoxon W = 3319.0, Z = 3.15, p = 0.002) and CMI (Wilcoxon W = 5603.5.0, Z = −3.73, p < 0.0001) cases had more comorbidities than healthy veterans.

Relationship between GW deployment, KGWI/CMI case status, and PD-like symptoms

Compared to healthy veterans, CMI cases had larger GW-exposure indices (Nisenbaum index: Wilcoxon W = 4037.5, Z = 5.32; Steele index: Wilcoxon W = 4725.0, Z = 4.00, p < 0.001 for both), and more motor (Wilcoxon W = 5064.0, Z = 4.36, p < 0.001) and non-motor (Wilcoxon W = 1482.5, Z = 10.36, p < 0.001) PD-like symptoms. Likewise, KGWI cases had larger GW-exposure indices (Nisenbaum index: Wilcoxon W = 2444.0, Z = 5.80; Steele index: Wilcoxon W = 2891.5, Z = 4.28, p < 0.001 for both) and more motor (Wilcoxon W = 3264.0, Z = 4.15, p < 0.001) and non-motor (Wilcoxon W = 1289.0, Z = 9.81, p < 0.001) PD-like symptoms than healthy veterans. KGWI (F1,124 = 6.68, p = 0.01) and CMI (F1,177 = 6.17, p = 0.01) cases also had smaller basal ganglia volumes than healthy controls, even after accounting for age, sex, a history of TBI severity, and psychiatric comorbidities (Table 4).

Table 4.

Gulf War-exposure indices, Parkinson’s disease-like (PD-like) symptoms, and intracranial volume-adjusted (ICV-adjusted) basal ganglia volumes by group in the study of Gulf War veterans (N = 293) recruited in 2002–2017

| Symptoms | Participants | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| total (N = 293) |

with KGWI (N = 122) |

with CMI (N = 234) |

controls (N = 48) |

|

| Gulf War-exposure indices (M±SD) | ||||

| Nisenbaum indexa | 3.3±2.2 | 4.1±2.0f | 3.7±2.1f | 1.9±1.9 |

| Steele indexb | 2.0±1.8 | 2.3±1.7f | 2.2±1.8f | 1.1±1.3 |

| Parkinson’s disease-like symptoms | ||||

| motorc [n (%)] | 70 (24) | 35 (29)g | 69 (30)g | 0 (0) |

| non-motord [n] (M±SD) | 5.9±3.2 | 7.4±2.1f | 7.1±2.3f | 1.2±1.4 |

| Adjusted basal ganglia volumese | 2.13×104 | –1.94×107 | –1.28×107 | 1.14×108 |

| (3.11×108) | (2.54×108)g | (2.83×108)g | (3.16×108) | |

Abbreviations as in Table 3.

A sum of responses regarding the frequency of taking PB pills, using cream or liquid and/or powdered pesticides on skin, and the presence or absence of experiences that lead the veteran to believe s/he was exposed to chemical agents while in the Gulf region, based on Nisenbaum et al. [30].

A sum of responses regarding the frequency of taking PB and being within 1 mile of an exploding SCUD missile among the veterans who served in Iraq and/or Kuwait, and a sum of responses regarding the frequency of wearing pesticide-treated uniforms, using cream or liquid and/or powdered pesticides on skin among the veterans who did not serve in Iraq or Kuwait, based on Steele et al. [5].

Tremors and/or shaking.

The total number of non-motor symptoms (i.e., feeling dizzy/light headed; fatigue; problems getting to/staying asleep; night sweats; blurred or double vision; pain in joints, muscles, or overall body pain; feeling anxious; feeling depressed; problems concentrating; problems remembering recent information) endorsed.

Adjusted for intracranial volume (ICV).

Significantly different from controls: p = 0.01.

Significantly different from controls: p < 0.001.

Relationship between GW-exposure indices and PD-like symptoms

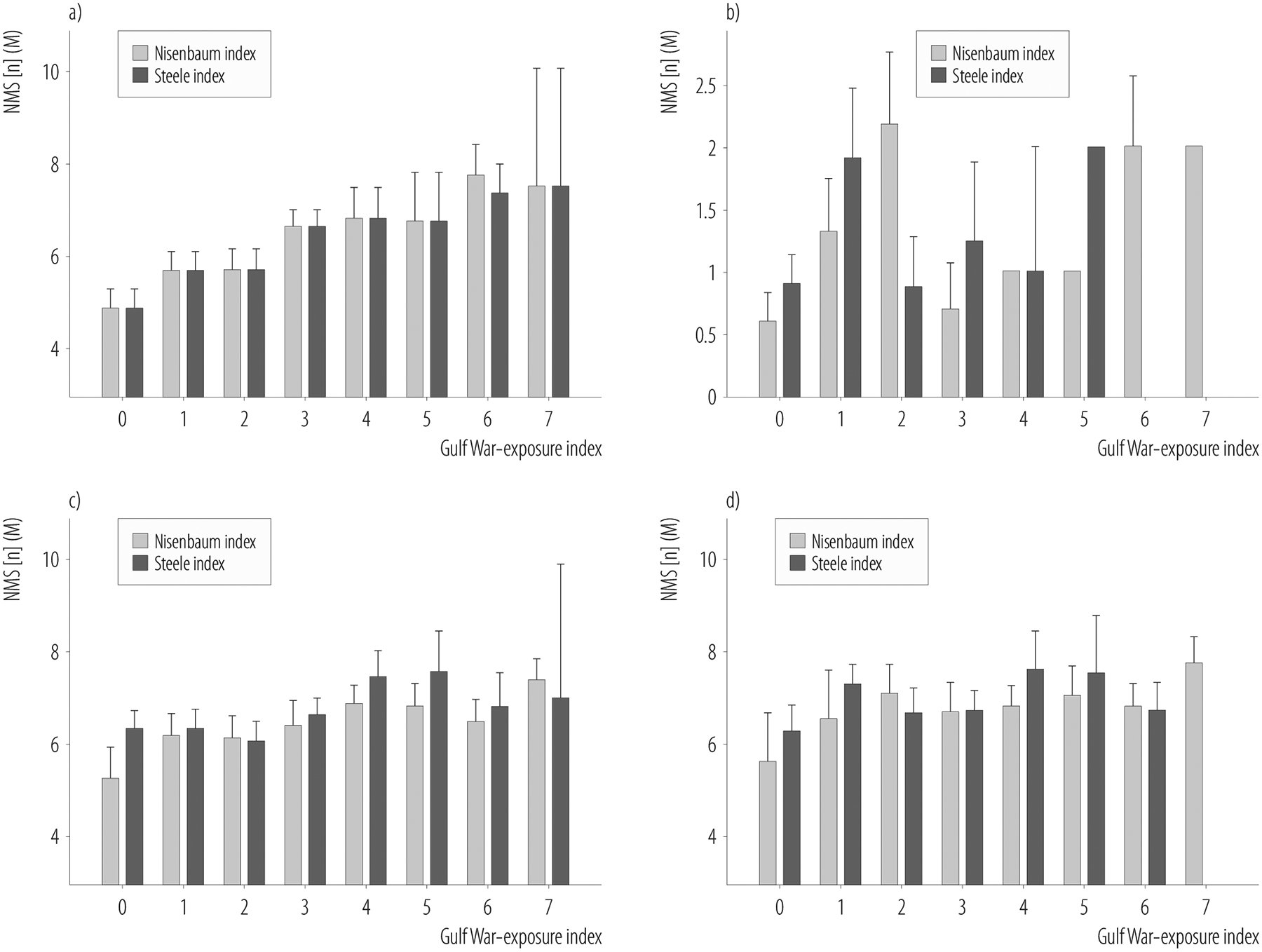

Table 5 summarizes the relationship between the 2 GW-exposure indices and PD-like symptoms in the entire sample, and in various veteran subgroups. Both GW-exposure indices were positively correlated with each other in the entire sample and in all subgroups of GW veterans (p < 0.001 for all). Motor and non-motor PD-like symptoms were also positively correlated with each other in all groups except healthy veterans who did not report any motor symptoms. Both GW-exposure indices were positively correlated with the number of non-motor PD-like symptoms in the entire sample (Figure 1). Among CMI cases, the Nisenbaum index was positively correlated with non-motor PD-like symptoms (Figure 1). However, there were no significant relationships between the GW-exposure indices and non-motor PD-like symptoms among KGWI cases. There were no significant correlations between basal ganglia volumes, the GW-exposure indices, or the number of PD-like symptoms.

Table 5.

Spearman’s ρ from correlations between the Gulf War-exposure indices for motor and non-motor symptoms in the study of Gulf War veterans (N = 293) recruited in 2002–2017

| Variable | Spearman’s correlations | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| index | symptoms | |||

| Nisenbauma | Steeleb | motor | non-motor | |

| Nisenbaum indexa | ||||

| total | – | 0.74g | 0.16f | 0.34g |

| KGWI | – | 0.72g | 0.04 | 0.12 |

| CMI | – | 0.70g | 0.08 | 0.16e |

| controls | – | 0.76g | – | 0.21 |

| Steele indexb | ||||

| total | 0.74g | – | 0.12e | 0.22g |

| KGWI | 0.72g | – | 0.02 | 0.10 |

| CMI | 0.70g | – | 0.08 | 0.10 |

| controls | 0.76g | – | – | 0.11 |

| Motor symptomsc | ||||

| total | 0.16f | 0.12e | – | 0.48g |

| KGWI | 0.04 | 0.02 | – | 0.29f |

| CMI | 0.08 | 0.08 | – | 0.43g |

| controls | – | – | – | – |

| Non-motor symptomsd | ||||

| total | 0.34g | 0.22g | 0.48g | – |

| KGWI | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.29f | – |

| CMI | 0.16e | 0.10 | 0.43g | – |

| controls | 0.21 | 0.11 | – | – |

Abbreviations as in Table 3.

A sum of responses regarding the frequency of taking PB pills, using cream or liquid and/or powdered pesticides on skin, and the presence or absence of experiences that lead the veteran to believe s/he was exposed to chemical agents while in the Gulf region, based on Nisenbaum et al. [30].

A sum of responses regarding the frequency of taking PB and being within 1 mile of an exploding SCUD missile among the veterans who served in Iraq and/or Kuwait and a sum of responses regarding the frequency of wearing pesticide-treated uniforms, using cream or liquid and/or powdered pesticides on skin among the veterans who did not serve in Iraq or Kuwait, based on Steele et al. [5].

Tremors and/or shaking.

Feeling dizzy/light headed; fatigue; problems getting to/staying asleep; night sweats; blurred or double vision; pain in joints, muscles, or overall body pain; feeling anxious; feeling depressed; problems concentrating; problems remembering recent information) endorsed.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

Figure 1.

Parkinson’s disease-like non-motor symptoms (NMS) as a function of the a) 2 Gulf War-exposure indices in the entire study sample, b) healthy deployed veterans, c) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Chronic Multisymptom Illness (CDC CMI) cases, and d) Kansas Gulf War illness (KGWI) cases in the study of Gulf War veterans (N = 293) recruited in 2002–2017

The Nisenbaum exposure index, based on Nisenbaum et al. [30], was derived by summing the self-reported frequency taking of PB pills, using cream or liquid and/or powdered pesticides on skin, and the presence or absence of experiences that lead the veteran to believe s/he was exposed to chemical agents while in the Gulf region.

The Steele exposure index, based on Steele et al. [5], was derived by summing the self-reported frequency of taking PB and being within 1 mile of an exploding SCUD missile among veterans who served in Iraq and/or Kuwait and among veterans who did not serve in Iraq or Kuwait, it was derived by summing the self-reported frequency of wearing pesticide-treated uniforms, using cream or liquid and/or powdered pesticides on skin.

Results of post-hoc analysis 1

Demographically, the veterans who self-reported having PD-like motor symptoms were less educated (Wilcoxon W = 8501.5, Z = 2.95, p = 0.003), less likely to have been officers (χ2 = 11.64, df = 1, p = 0.001), and more likely to have been forward deployed (i.e., served in Iraq and/or Kuwait) during the GW (Wilcoxon W = 8501.5, Z = 2.95, p = 0.003), and they had more psychiatric comorbidities (current PTSD: χ2 = 25.87, df = 1, p < 0.001; current MDD: χ2 = 5.43, df = 1, p = 0.02; a history of alcohol abuse/dependence: χ2 = 11.49, df = 1, p = 0.001) than the veterans who reported no motor symptoms (Table 6).

Table 6.

Demographic, military and clinical characteristics as a function of self-reported motor symptoms in the study of Gulf War veterans (N = 293) recruited in 2002–2017

| Variable | Symptoms | |

|---|---|---|

| motor (N = 70, 24%) |

non-motor (N = 223, 76%) |

|

| Age [years] (M±SD) | 54.0+8.7 | 56.0+8.9 |

| Education [years] (M±SD) | 14.3+2.2a | 15.2+2.4 |

| Sex [n (%)] | ||

| males | 57 (81) | 189 (85) |

| females | 13 (19) | 34 (15) |

| Race [n (%)] | ||

| white | 46 (66) | 166 (74) |

| black | 6 (9) | 20 (9) |

| other | 18 (23) | 37 (17) |

| GW military characteristics | ||

| officer during GW [n (%)] | 5 (7)a | 65 (29) |

| branch of service [n (%)] | ||

| army | 42 (60) | 126 (57) |

| marines | 10 (14) | 38 (17) |

| air force | 3 (4) | 28 (13) |

| navy | 15 (21) | 31 (14) |

| type of service [n (%)] | ||

| active duty | 54 (77) | 161 (72) |

| reserves | 12 (17) | 47 (21) |

| National Guard | 4 (6) | 15 (7) |

| Khamisiyah Plume Exposure [n (%)] | 22 (33) | 80 (36) |

| Served in Iraq or Kuwait [n (%)] | 51 (77)c | 142 (64) |

| Comorbiditiesa [n (%)] | 45 (64)c | 81 (36) |

| current PTSD | 23 (34)c | 20 (9) |

| current MDD | 13 (19)c | 20 (9) |

| ETOH history | 33 (49)c | 60 (27) |

| substance history | 6 (9) | 21 (10) |

| History of TBIb [n (%)] | ||

| improbable | 13 (38) | 92 (55) |

| possible | 10 (29) | 39 (23) |

| mild | 11 (32) | 35 (21) |

| moderate | 0 (0) | 2 (1) |

| GW-exposure indices [n (%)] | ||

| Nisenbaum index | 4.0 (2.0)c | 3.2 (2.2) |

| Steele index | 2.3 (1.9)c | 1.8 (1.7) |

| Specific GW exposures [n (%)] | ||

| oil well fire smoke | 2.1 (1.0) | 1.8 (1.1) |

| proximity to SCUD missile explosion | 0.9 (0.9) | 0.6 (0.8) |

| hearing chemical alarms sound | 1.5 (1.0) | 1.2 (1.0) |

| contact with destroyed enemy vehicles | 1.2 (1.0) | 1.0 (1.0) |

| contact with US vehicles destroyed by friendly fire | 0.5 (0.8) | 0.3 (0.7) |

| took PB pills | 1.6 (1.1) | 1.4 (1.1) |

| contact with POWs | 0.9 (1.0) | 0.8 (1.0) |

| used powdered pesticides on skin | 0.5 (1.0) | 0.4 (0.9) |

| used cream/liquid pesticides on skin | 1.7 (1.3) | 1.4 (1.3) |

| wore pesticide-treated uniform | 1.0 (1.3) | 0.7 (1.2) |

| wore flea collar | 0.2 (0.6) | 0.1 (0.5) |

| saw the living area sprayed with pesticides | 0.9 (1.1)d | 0.5 (0.9) |

| lived in a tent heated by fuel-burning heater | 1.5 (1.4) | 1.5 (1.4) |

| had contact with Chemical Agent Resistant Coating paint | 0.8 (1.1) | 0.4 (0.9) |

At least ≥ 1 of the psychiatric diagnoses listed below.

Data available for 202 GW veterans.

Significantly different from the veterans without motor symptoms, p < 0.04.

Significantly different from the veterans without motor symptoms after Bonferroni adjustment (p = 0.003).

Although the GW-exposure indices were created to avoid the confounding effects of intercorrelated, concurrent exposures, the indices may have obscured the individual effects of certain exposures over others. Because veterans with PD-like motor symptoms also had larger GW-exposure indices than veterans with no motor symptoms (Nisenbaum index: Wilcoxon W = 31 111, Z = 2.72, p = 0.006; Steele index: Wilcoxon W = 31 529.5, Z = 2.07, p < 0.04), this prompted the authors to explore group differences in individual GW-related exposures of interest. Post-hoc analyses revealed that the veterans who endorsed PD-like motor symptoms were more likely to report seeing their living area being sprayed or fogged with pesticides than the veterans who self-reported no motor symptoms (Wilcoxon W = 28 386, Z = 2.93, p = 0.003) (Table 6).

Post-hoc analysis 2 results

There were no significant relationships between the DOD estimates of military GW military personnel’s exposures to oil well fire smoke [42] or the cumulative dosage estimates to low levels of sarin and cyclosarin from the demolition operations at Khamisiyah, Iraq [24], and the self-reported presence of PD-like motor and non-motor symptoms or the basal ganglia volume.

DISCUSSION

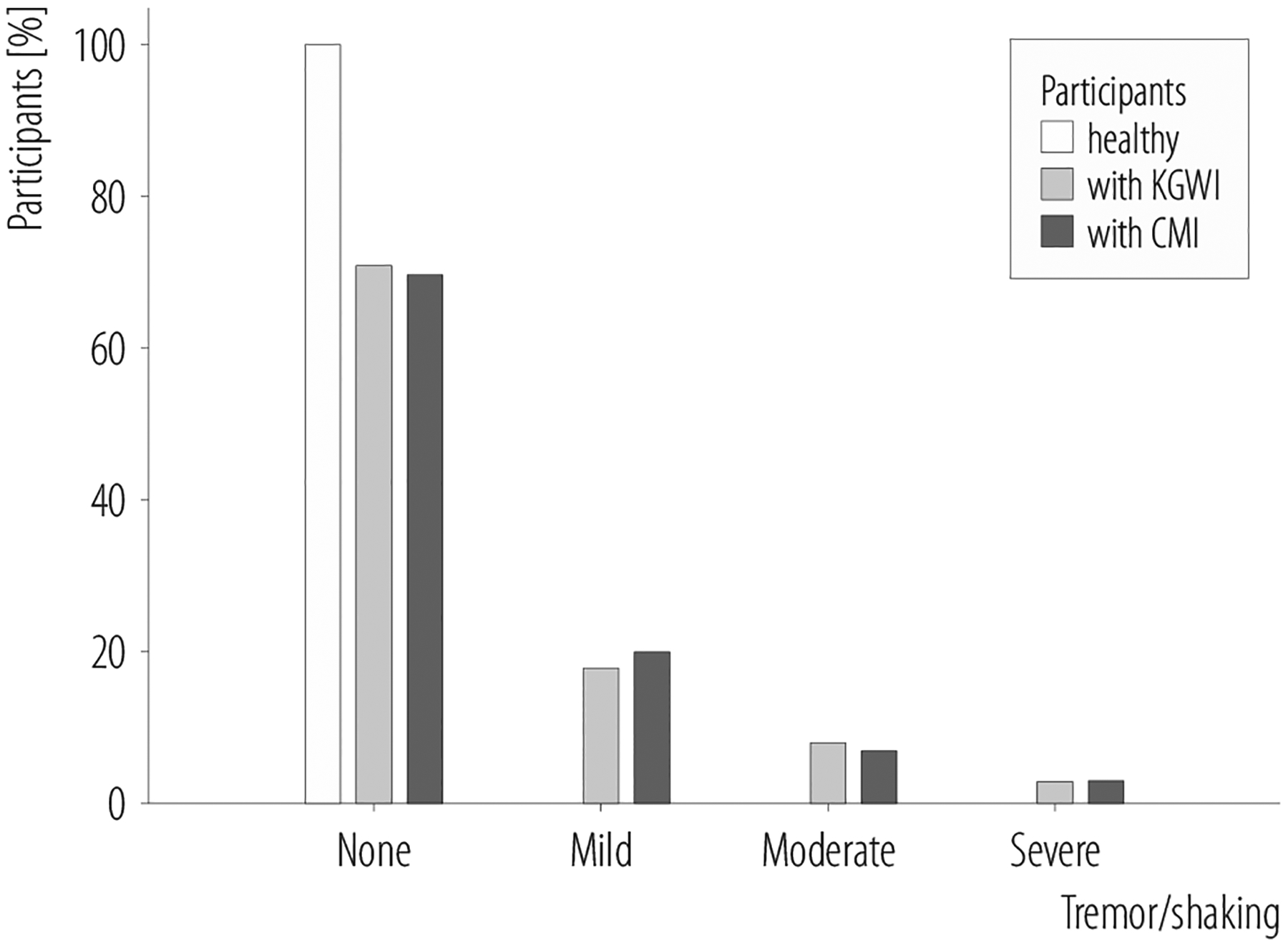

The first question asked in this study is as follows: Does GW deployment, in the absence of having developed GWI, increase a veteran’s risk of having PD-like symptoms? In this convenience sample of deployed GW veterans, there were no self-reports of PD-like motor symptoms among “healthy” (i.e., those without KGWI/CMI or any KGWI exclusionary condition[s]) veterans (Figure 2). Healthy GW veterans also self-reported fewer non-motor PD-like symptoms compared to KGWI and CMI cases. Thus, GW deployment, in the absence KGWI or CMI, does not appear to increase a veteran’s risk of having PD-like symptoms. However, it should be noted that this convenience sample of 293 deployed GW veterans, who were originally recruited for neuroimaging studies investigating the effects of exposure to the Khamisiyah plume on brain function and structure, may not be completely representative of all GW veterans.

Figure 2.

Healthy veterans, and Kansas Gulf War illness (KGWI) and chronic multisymptom illness (CMI) cases, both without and with PD-like motor symptoms, in the study of Gulf War veterans (N = 293) recruited in 2002–2017

Healthy deployed veterans also had lower GW-exposure indices compared to KGWI and CMI cases, which may explain why they stayed “healthy.” Demographically, healthy veterans (16% of the study sample) were different from KGWI and CMI cases, who tended to be younger and less educated, and were more likely to be minorities and enlisted personnel during the GW. Not surprisingly, healthy veterans also had fewer psychiatric comorbidities (e.g., current PTSD or MDD) compared to KGWI and CMI cases. The second question asked in this study is as follows: Does having KGWI/CMI increase a veteran’s risk of having PD-like symptoms? Veterans with KGWI/CMI endorsed significantly more PD-like motor and non-motor symptoms than healthy veterans. But this is not unexpected given the overlap between many of the PD-like symptoms and KGWI/CMI symptoms (Table 2).

Because epidemiological studies have linked environmental exposures, such as pesticides, metals, and polychlorinated biphenyls, to an increased risk of PD [3], the authors investigated the relationship between GW-exposures of interest and the number of PD-like symptoms that veterans endorsed. To avoid the confounding effects of intercorrelated, concurrent exposures [25,26], and to reduce the number of individual comparisons, 2 GW-exposure indices were created for analyses. The first index, based on Nisenbaum et al. [30], was created by combining the veterans’ self-reported frequency taking of PB pills, using pesticides on skin, and a belief that they may have been exposed to chemical agents. The second index, based Steele et al. [5], was derived by combining the self-reported frequency of taking PB pills and being within 1 mile of an exploding SCUD missile among the veterans who served in Iraq and/or Kuwait. Among the veterans who did not serve in Iraq and/or Kuwait, the index was derived by combining the self-reported frequency of wearing pesticide-treated uniforms and using pesticides on skin.

Not surprisingly, both KGWI and CMI cases had larger GW-exposure indices compared to healthy veterans. This reaffirms the idea that GWI is related to exposure to deployment-related chemicals [4,5]. Both GW-exposure indices were positively correlated with non-motor PD-like symptoms in the entire sample of 293 GW veterans (Figure 1). Thus, it may be that the occurrence of GWI with Parkinsonian features is associated with exposures to chemicals present in the GW environment. Among CMI cases, the Nisenbaum exposure index was positively correlated with the number of non-motor PD-like symptoms. However, there were no significant correlations in other subgroups of veterans. The latter finding may relate to the restricted range of exposures and symptoms in the subgroups (e.g., healthy veterans tended to have few exposures and few symptoms while ill/symptomatic veterans tended to have higher levels of exposures and more symptoms).

Only 24% of this convenience sample of deployed GW veterans self-reported PD-like motor symptoms. This subgroup of veterans with PD-like motor symptoms had fewer years of formal education, were less likely to have been officers during the GW, and more likely to have been forward deployed (i.e., in Iraq and/or Kuwait). They also had more psychiatric comorbidities, and were more likely to report seeing their living area being sprayed or fogged with pesticides than veterans without motor symptoms. The latter finding is interesting in light of certain meta-analyses that have reported associations between rural living, pesticide exposure, and PD [43,44]. When the proportion of agricultural land was used as a marker of rurality, the incidence of PD increased progressively with rurality [45]. Furthermore, specific agricultural activities have been associated with a higher PD risk, even in non-farmers, suggesting that non-occupational pesticide exposures plays a role in PD [45].

Another main finding of this study is that KGWI and CMI cases had smaller basal ganglia volumes than healthy GW veterans. This result is in line with Haley’s suggestion that an injury to or loss of dopaminergic neurons in the basal ganglia may be related to GWI, as classified by the Haley syndrome factor analyses [46,47]. However, not all studies have replicated Haley et al.’s finding [48], and the present study categorized GW veterans by the CDC CMI and KGWI case definitions, and not by the Haley syndrome. This finding is also noteworthy because the basal ganglia function is severely impaired in PD [49] and a decreased basal ganglia volume has been reported in PD [49–55].

However, the authors did not find any significant relationship between the total basal ganglia volume and PD-like symptoms or the GW-exposure indices. This may be because PD is histopathologically associated with the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra [56]. Therefore, the total basal ganglia volume is not sensitive enough to detect the effects of GW-related exposures or PD-like symptoms. It may be that more PD-specific measures (e.g., iron and neuromelanin, a pigment produced in dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra that selectively degenerates in PD) are needed to detect associations with GW-related exposures and/or PD-like symptoms.

Because the gold standard for studies of the exposure outcome relationships requires the demonstration of a dose-effect relationship between a biological or environmental measure of the actual exposure dose and an outcome of interest, in the second post-hoc analyses, the authors looked for, but did not find, any significant relationships between DOD estimates of exposure to smoke from oil well fires, to the Khamisyah plume, PD-like motor and non-motor symptoms, and the basal ganglia volume. This negative finding may be due to a lack of power. The authors only had estimates of oil well fire smoke exposure for 81 veterans in the sample, and of the cumulative exposure to the Khamisiyah plume for 100 veterans in the sample. The negative finding may also relate to inaccuracies in the DOD estimates. The exposure level estimates were calculated at the unit rather than individual level. Therefore, there is no definitive way of checking if an individual soldier was with his or her unit on the days when the exposures were modeled. Furthermore, the United States General Accounting Office (GAO) has cited a number of problems with the Khamisiyah plume models, including inaccuracies in the source terms (e.g., quantity and purity of nerve agent), underestimation of explosion plume heights, unrepresentative conditions of field tests, and wide divergence of plume patterns from the various computer models [57], which led the GAO to conclude that the plume models did not reliably indicate which troops were exposed to nerve agent released from the Khamisiyah demolitions. Finally, the DOD plume models do not take into account other nerve agent exposures that may have occurred in the Gulf War [23,58–60].

There are many interesting similarities between GWI and sporadic PD:

Epidemiological studies have linked environmental chemical exposures to an increased risk of both diseases [3–5].

Gene-environment interaction effects have been implicated in the incidence risk of both diseases because of some genetically-determined inter-individual differences in metabolizing specific types of chemicals [61,62]. In the case of GWI, Steele et al. reported that GW veterans with genetic variants of the butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) enzyme, which is less able to metabolize acetylcholinesterase inhibiting chemicals (such as carbamates) [63], were at a greater risk of developing KGWI if they used PB during deployment [4,32].

Both diseases are highly variable and their symptoms may differ among different patients [64].

Both diseases have been proposed to be syndromes with multiple possible etiologies [5,65].

Many GWI symptoms are similar to non-motor PD symptoms (Table 2).

Mechanistic studies suggest that oxidative stress, neuroinflammation and mitochondrial dysfunction are involved in the pathogenesis of both diseases [4,66–68].

As noted in the introduction, PD is a heterogeneous disease with different clinical subtypes that have been defined based on key clinical features [69,70]. There is some evidence that the different PD subtypes differ in their pathophysiological mechanism or disease progression [69,71]. It has also been suggested that different causative factors may be involved in different clinical subtypes of PD [72,73]. Therefore, it is an intriguing possibility that GWI may be an early form of 1 subtype of PD. Future studies with larger, randomly selected samples of GW veterans undergoing clinical evaluations for PD will be needed to answer this question.

The present study’s findings should be considered in light of some limitations. First, the veterans involved were not clinically assessed for PD; PD-like symptoms were only assessed by self-reports. Second, the assessment of PD-like symptoms and GW-related exposures by self-reports may be subject to recall bias.

However, the lack of measured data on the types and doses of exposures experienced by GW veterans in theater severely limits the methods that investigators can use to evaluate the consequences of GW-related exposures [5,60]. One key feature of the GW theater experience is exposure to a multitude of chemicals. To reduce the number of individual comparisons and to avoid the confounding effects of intercorrelated, concurrent exposures, 2 GW-exposure indices were created based on the works by Niesebaum et al. [30] and Steele et al. [5]. However, it is possible that by combining exposures, the authors inadvertently obscured the importance of certain exposures over others. This may explain, at least in part, why the GW-exposure indices were not significantly correlated with the total basal ganglia volume.

In a post-hoc analysis, the authors found that the veterans with PD-like motor symptoms were more likely to report having witnessed their living area being sprayed with pesticides than the veterans with no motor symptoms. It is likely that different GW veterans were exposed to different combinations of chemicals during deployment. Therefore, another limitation of this study is that the GW-exposure indices did not adequately account for the complex, possibly additive, but not necessarily linear effects of chemicals when combined into mixtures such as those experienced in theater by GW veterans.

Also, because the authors did not inquire about the veterans’ exposures and experiences that may have occurred in the years since the end of the GW, the possibility cannot be ruled out that non-GW related exposures and/or experiences (e.g., occupational chemical exposures, excessive pesticide use, etc.) that have taken place in the nearly 30 years since the end of the GW may have contributed to their PD-like symptoms. The recruitment of participants lasted over a period of 15 years, with a gap in between 2 separate studies. This could have introduced a confound because certain symptoms may develop (or cease) over time and the recall of exposures could have gotten more difficult as the time passed, or more distinct in instances where a particular exposure or situation was discussed in the media as indicative of GWI, causing veterans to remember the exposure more vividly.

Another limitation is that this convenience sample of GW veterans who participated in the previous studies investigating the effects of exposure to the Khamisiyah plume on brain function and structure may not be representative of all GW veterans. Because the previous studies did not specifically target healthy, symptom-free veterans for recruitment, only 16% of the present sample were “healthy” deployed veterans. Also, a current or lifetime history of any psychiatric disorder with psychotic features acted as an exclusionary condition for these previous studies. Because psychosis is a common symptom of PD [74], this may have led to an underrepresentation of PD cases in the present sample. Because of these limitations, future studies based on larger, randomly selected samples of GW veterans will be needed to replicate and extend these findings.

CONCLUSIONS

Although little is known about the long-term consequence of GWI, findings from this convenience sample of 293 GW veterans suggest that GW deployment, in the absence of KGWI or CMI, is not associated with showing PD-like symptoms. In contrast, KGWI and CMI cases not only displayed more PD-like symptoms, but KGW and CMI cases also had smaller basal ganglia volumes and more GW-related exposures of concern than healthy GW veterans. Because the present study did not clinically evaluate the veterans involved for PD, future studies will be necessary to determine if KGWI and/or CMI cases truly are at increased risk of developing PD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author would like to thank the Gulf War Veterans who participated in these studies.

Funding:

this study was supported by the Department of Veterans’ Affairs Merit Award (grant No. I01 CX0007080 entitled “Longitudinal Assessment of Gulf War Veterans with Suspected Sarin Exposure”).

The content of this publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the Department of Veterans Affairs. This material is the result of work supported with the resources and use of facilities at the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

REFERENCES

- 1.De Lau L, Breteler M. Epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5(6):525–35, 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70471-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davie CA. A review of Parkinson’s disease. Br Med Bull. 2008;86(1):109–27, 10.1093/bmb/ldn013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nandipati S, Litvan I. Environmental Exposures and Parkinson’s Disease. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(9):E881, 10.3390/ijerph13090881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White RF, Steele L, O’Callaghan JP, Sullivan K, Binns JH, Golomb BA, et al. Recent research on Gulf War illness and other health problems in veterans of the 1991 Gulf War: Effects of toxicant exposures during deployment. Cortex. 2016;74:449–75, 10.1016/j.cortex.2015.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steele L, Sastre A, Gerkovich MM, Cook MR. Complex factors in the etiology of Gulf War Illness: Wartime exposures and risk factors in veteran subgroups. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(1):112–8, 10.1289/ehp.1003399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fukuda K, Nisenbaum R, Stewart G, Thompson WW, Robin L, Washko RM, et al. Chronic multisymptom illness affecting Air Force veterans of the Gulf War. JAMA. 1998;280(11):981–8, 10.1001/jama.280.11.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Unwin C, Blatchley N, Coker W, Ferry S, Hotopf M, Hull L, et al. Health of UK servicemen who served in Persian Gulf War. Lancet. 1999;353:169–78, 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)11338-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang HK, Mahan CM, Lee KY, Magee CA, Murphy FM, et al. Illnesses among United States veterans of the Gulf War: A population-based survey of 30,000 veterans. J Occup Environ Med. 2000;42(5):491–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steele L Prevalence and patterns of Gulf War illness in Kansas veterans: association of symptoms with characteristics of person, place, and time of military service. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(10):992–1002, 10.1093/aje/152.10.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winkenwerder W Environmental Exposure Report: Pesticides Final Report [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Defense, Office of the Special Assistant to the Undersecretary of Defense (Personnel and Readiness) for Gulf War Illnesses Medical Readiness and Military Deployments; 2003. [cited 2018 Apr 5]. Available from: https://gulflink.health.mil/pest_final/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sullivan K, Krengel M, Bradford W, Stone C, Thompson TA, Heeren T, et al. Neuropsychological functioning in military pesticide applicators from the Gulf War: Effects on information processing speed, attention and visual memory. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2018;65:1–13, 10.1016/j.ntt.2017.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li B, Mahan CM, Kang HK, Eisen SA, Engel CC. Longitudinal health study of US 1991 Gulf War veterans: changes in health status at 10-year follow-up. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174(7):761–8, 10.1093/aje/kwr154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dursa EK, Barth SK, Schneiderman AI, Bossarte RM. Physical and Mental Health Status of Gulf War and Gulf Era Veterans: Results From a Large Population-Based Epidemiological Study. J Occup Environ Med. 2016;58(1):41–6, 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barth SK, Kang HK, Bullman TA, Wallin MT. Neurological mortality among U.S. veterans of the Persian Gulf War: 13-year follow-up. Am J Ind Med. 2009;52(9):663–70, 10.1002/ajim.20718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahlknecht P, Seppi K, Poewe W. The Concept of Prodromal Parkinson’s Disease. J Parkinsons Dis. 2015;5(4):681–97, 10.3233/JPD-150685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chaudhry H, Findley T, Quigley KS, Bukiet B, Ji Z, Sims T, et al. Measures of postural stability. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2004; 41(5):713–20, 10.1682/JRRD.2003.09.0140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaudhry H, Findley T, Quigley KS, Ji Z, Maney M, Sims T, et al. Postural stability index is a more valid measure of stability than equilibrium score. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2005;42(4):547–56, 10.1682/JRRD.2004.08.0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pont-Sunyer C, Hotter A, Gaig C, Seppi K, Compta Y, Katzenschlager R, et al. The onset of nonmotor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease (the ONSET PD study). Mov Disord. 2015;30(2):229–37, 10.1002/mds.26077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rana AQ, Ahmed US, Chaudry ZM, Vasan S. Parkinson’s disease: a review of non-motor symptoms. Expert Rev Neurother. 2015;15(5):549–62, 10.1586/14737175.2015.1038244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaudhuri KR, Martinez-Martin P, Brown R, Sethi K, Stocchi F, Ondo W, et al. The metric properties of a novel non-motor symptoms scale for Parkinson’s disease: Results from an international pilot study. Mov Disord. 2007;22(13):1901–11, 10.1002/mds.21596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The Iowa Persian Gulf Study Group. Self-reported illness and health status among Gulf War veterans: a population-based study. JAMA. 1997;277(3):238–45, 10.1001/jama.1997.03540270064028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blandini F, Nappi G, Tassorelli C, Martignoni E. Functional changes of the basal ganglia circuitry in Parkinson’s disease. Prog Neurobiol. 2000;62(1):63–88, 10.1016/S0301-0082(99)00067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.U.S. Government Publishing Office [Internet].USA: Coalition Chemical Detections and Health of Coalition Troops in Detection Area; 1996. [cited 2017 Apr 4]. Available from: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CRPT-105hrpt388/html/CRPT-105hrpt388.htm.

- 24.Gulflink Office of the Special Assistant for Gulf War Illness [Internet]. USA: Technical Report: Modeling and Risk Characterization of US Demolition Operations at Khamisiyah Pit, 2002. [cited 2018 Apr 5]. Available from: https://gulflink.health.mil/khamisiyah_tech/.

- 25.Cherry N, Creed F, Silman A, Dunn G, Baxter D, Smedley J, et al. Health and exposures of United Kingdom Gulf war veterans. Part II: the relation of health to exposure. Occup Environ Med. 2001;58(5):299–306, 10.1136/oem.58.5.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fricker RD, Reardon E, Spektor DM, Cotton SK, Hawes-Dawwon J, Pace JE, et al. Pesticide use during the Gulf War: A survey of Gulf War Veterans. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2000. [cited 2018 Apr 5]. Available from: https://www.rand.org/pubs/monograph_reports/MR1018z12.html. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barrett DH, Gray GC, Doebbeling BN, Clauw DJ, Reeves WC. Prevalence of symptoms and symptom-based conditions among Gulf War veterans: current status of research findings. Epidemiol Rev. 2002;24(2):218–27, 10.1093/epirev/mxf003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hotopf M, Wessely S. Can epidemiology clear the fog of war? Lessons from the 1990–91 Gulf War. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34(4):791–800, 10.1093/ije/dyi102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haley RW, Kurt TL. Self-reported exposure to neurotoxic chemical combinations in the Gulf War. JAMA. 1997;277(3):231–7, 10.1001/jama.1997.03540270057027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nisenbaum R, Barrett DH, Reyes M, Reeves WC. Deployment stressors and a chronic multisymptom illness among Gulf War veterans. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2000;188(5):259–66, 10.1097/00005053-200005000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolfe J, Proctor SP, Erickson DJ, Hu H. Risk factors for multisymptom illness in US Army veterans of the Gulf War. J Occup Environ Med. 2002;44(3):271–81, 10.1097/00043764-200203000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans’ Illnesses (RAC0GWVI). Gulf War Illness and the Health of Gulf War Veterans: Research Update and Recommendations, 2009–2013 [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: US Government Printing Office; 2014. [cited 2018 Apr 4]. Available from: https://www.va.gov/RAC-GWVI/RACReport2014Final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 33.First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute Biometrics Research Development; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wolfe J, Kimmerling R, Brown P, Chresman K, Levin K. Psychometric review of the lift stressor checklist-revised. In:Stamm BH, editor. Instrumentation in stress, trauma, and adaptation. Lutherville: Sirdan Press; 1996. p. 144–51. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blake D, Weather F, Nagy L, Kaloupek D, Klauminzer G, Charney D, et al. Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS). [Internet]. Boston: National Center for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, Behavioral Science Division; 1997. [cited 2018 Apr 5]. Available from: https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/documents/CAPSmanual.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Corrigan JD, Bogner JA. Initial reliability and validity of the OSU TBI identification method. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2007;22(6):318–29, 10.1097/01.HTR.0000300227.67748.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bogner JA, Corrigan JD. Reliability and validity of the OSU TBI identification method with prisoners. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2009;24(6):279–91, 10.1097/HTR.0b013e3181a66356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dale AM, Fischl B, Sereno MI. Cortical surface-based analysis I: segmentation and surface reconstruction. Neuroimage. 1999;9(2):179–94, 10.1006/nimg.1998.0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Desikan RS, Segonne F, Fischl B, Quinn BT, Dickerson BC, Blacker D, et al. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage. 2006;31(3):968–80, 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fischl B, Sereno MI, Dale AM. Cortical surface-based analysis. II: Inflation, flattening, and a surface-based coordinate system. Neuroimage. 1999;9(2):195–207, 10.1006/nimg.1998.0396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fischl B, van der Kouwe A, Destrieux C, Halgren E, Ségonne F, Salat DH, et al. Automatically parcellating the human cerebral cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2004;14(1):11–22, 10.1093/cercor/bhg087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gulflink Office of the Special Assistant for Gulf War Illness [Internet]. USA: Environmental exposures report: Oil well fires. 2000. [cited 2018 Apr 5]. Available from: https://gulflink.health.mil/owf_ii/.

- 43.Noyce AJ, Bestwick JP, Silveira-Moriyama L, Hawkes CH, Giovannoni G, Lees AJ, et al. Meta-analysis of early nonmotor features and risk factors for Parkinson disease. Ann Neurol. 2012;72(6):893–901, 10.1002/ana.23687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pezzoli G, Cereda E. Exposure to pesticides or solvents and risk of Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2013;80(20):2035–41, 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318294b3c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kab S, Spinosi J, Chaperon L, Dugravot A, Singh-Manoux A, Moisan F, et al. Agricultural activities and the incidence of Parkinson’s disease in the general French population. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32(3):203–16, 10.1007/s10654-017-0229-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haley RW, Marshall WW, McDonald GG, Daugherty MA, Petty F, Fleckenstein JL. Brain abnormalities in Gulf War syndrome: evaluation with 1H MR spectroscopy. Radiology. 2000;215(3):807–17, 10.1148/radiology.215.3.r00jn48807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haley RW, Fleckenstein JL, Marshall WW, McDonald GG, Kramer GL, Petty F. Effect of Basal Ganglia Injury on Central Dopamine Activity in Gulf War Syndrome Correlation of Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy and Plasma Homovanillic Acid Levels. JAMA Neurology. 2000;57(9):1280–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weiner MW, Meyerhoff DJ, Neylan TC, Hlavin J, Ramage ER, McCoy D, et al. The relationship between Gulf War illness, brain N-acetylaspartate, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Mil Med. 2011;176(8):896–902, 10.7205/MILMED-D-10-00332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pitcher TL, Melzer TR, Macaskill MR, Graham CF, Livingston L, Keenan RJ, et al. Reduced striatal volumes in Parkinson’s disease: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Transl Neurodegener. 2012;1(1):17, 10.1186/2047-9158-1-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Almeida OP, Burton EJ, McKeith I, Gholkar A, Burn D, O’Brien JT. MRI study of caudate nucleus volume in Parkinson’s disease with and without dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer’s disease. Demen Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2003;16(2):57–63, 10.1159/000070676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Geng DY, Li YX, Zee CS. Magnetic resonance imaging-based volumetric analysis of basal ganglia nuclei and substantia nigra in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neurosurgery. 2006;58(2):256–62, 10.1227/01.NEU.0000194845.19462.7B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ghaemi M, Hilker R, Rudolf J, Sobesky J, Heiss WD. Differentiating multiple system atrophy from Parkinson’s disease: contribution of striatal and midbrain MRI volumetry and multi-tracer PET imaging. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73(5):517–23, 10.1136/jnnp.73.5.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Krabbe K, Karlsborg M, Hansen A, Werdelin L, Mehlsen J, Larsson HB, et al. Increased intracranial volume in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Sci. 2005;239(1):45–52, 10.1016/j.jns.2005.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.O’Neill J, Schuff N, Marks WJ, Feiwell R, Aminoff MJ, Weiner MW. Quantitative 1 H magnetic resonance spectroscopy and MRI of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2002;17(5):917–27, 10.1002/mds.10214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schulz JB, Skalej M, Wedekind D, Luft AR, Abele M, Voigt K, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging-based volumetry differentiates idiopathic Parkinson’s syndrome from multiple system atrophy and progressive supranuclear palsy. Ann Neurol. 1999;45(1):65–74, . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Makenzie IRA. The Pathology of Parkinson’s Disease. BCMJ. 2001;43(3):142–7. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rhodes K [Internet]. Testimony before the subcommittee on National Security, Emerging Threats, and International Relations, Committee on Government Reform, House of Representatives, 2014 DOD’s conclusions about U.S. Troops’ exposures cannot be adequately supported [cited 2018 Mar 1]. Washington D.C.: United States General Accounting Office; 2004. Available from: https://www.gao.gov/new.items/d04821t.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Riegle DW. U.S. chemical and biological warfare-related dual use exports ot Iraq and their possible impact on health consequences of the Persian Gulf War [Internet]. Washington D.C.: Gulflink Office of the Special Assistant for Gulf War Illness; 1994. [cited 2018 Apr 5]. Available from: https://gulflink.health.mil/medsearch/FocusAreas/riegle_report/riegle_report_main.html. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tucker JB. Evidence Iraq used chemical weapons during the Persian Gulf War. Nonproliferation Rev. 1997;Spring–Summer:114–22. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Haley RW, Tuite JJ. Epidemiologic evidence of health effects from long-distance transit of chemical weapons fallout from bombing early in the 1991 Persian Gulf War. Neuroepidemiology. 2013;40(3):178–89, 10.1159/000345124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Biernacka JM, Chung SJ, Armasu SM, Anderson KS, Lill CM, Bertram L, et al. Genome-wide gene-environment interaction analysis of pesticide exposure and risk of Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2016;32:25–30, 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Steele L, Lockridge O, Gerkovich MM, Cook MR, Sastre A. Butyrylcholinesterase genotype and enzyme activity in relation to Gulf War illness: preliminary evidence of gene-exposure interaction from a case–control study of 1991 Gulf War veterans. Environ Health. 2015;14:4, 10.1186/1476-069X-14-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lockridge O, Masson P. Pesticides and susceptible populations: people with butyrylcholinesterase genetic variants may be at risk. Neurotoxicology. 2000;21(1–2):113–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.National Institute on Aging [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: 2018. [cited 2017 Dec 1]. Parkinson’s Disease. Available from: https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/parkinsons-disease. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Alder CH. Premotor symptoms and early diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Int J Neurosci. 2011;121(Suppl 2):3–8, 10.3109/00207454.2011.620192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Blesa J, Trigo-Damas I, Quiroga-Varela A, Jackson-Lewis VR. Oxidative stress and Parkinson’s disease. Front Neuroanat. 2015;9:91, 10.3389/fnana.2015.00091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang Q, Liu Y, Zhou J. Neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s disease and its potential as therapeutic target. Transl Neurodegener. 2015;4:19, 10.1186/s40035-015-0042-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Exner N, Lutz AK, Haass C, Winklhofer KF. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease: molecular mechanisms and pathophysiological consequences. EMBO J. 2012;31(14):3038–62, 10.1038/em-boj.2012.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Selikhova M, Williams DR, Kempster PA, Holton JL, Revesz T, Lees AJ. A clinico-pathological study of subtypes in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2009;132(11):2947–57, 10.1093/brain/awp234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Van Rooden SM, Heiser WJ, Kok JN, Verbaan D, van Hilten JJ, Marinus J. The identification of Parkinson’s disease subtypes using cluster analysis: a systematic review. Mov Disord. 2010;25(8):969–78, 10.1002/mds.23116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Eggers C, Pedrosa DJ, Kahraman D, Maier F, Lewis CJ, Fink GR, et al. Parkinson subtypes progress differently in clinical course and imaging pattern. PLoS One. 2012;7(10): e46813, 10.1371/journal.pone.0046813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Marras C, Lang A. Parkinson’s disease subtypes: lost in translation? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84(4):409–15, 10.1136/jnnp-2012-303455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Obeso JA, Rodriguez-Oroz MC, Goetz CG, Marin C, Kordower JH, Rodriguez M, et al. Missing pieces in the Parkinson’s disease puzzle. Nat Med. 2010;16(6):653–61, 10.1038/nm.2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zahodne LB, Fernandez HH. Pathophysiology and treatment of psychosis in Parkinson’s disease: a review. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(8):665–82, 10.2165/00002512-200825080-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Furlong M, Tanner CM, Goldman SM, Bhudhikanok GS, Blair A, Chade A, et al. Protective glove use and hygiene habits modify the associations of specific pesticides with Parkinson’s disease. Environ Int. 2015;75:144–50, 10.1016/j.envint.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gatto NM, Cockburn M, Manthripragada AD, Ritz B. Well-water consumption and Parkinson’s disease in rural California. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117(12):1912–8, 10.1289/ehp.0900852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Narayan S, Liew Z, Paul K, Lee PC, Sinsheimer JS, Bronstein JM, et al. Household organophosphorus pesticide use and Parkinson’s disease. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(5):1476–85, 10.1093/ije/dyt170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Freire C, Koifman S. Pesticide exposure and Parkinson’s disease: epidemiological evidence of association. Neurotoxicology. 2012;33(5):947–71, 10.1016/j.neuro.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Firestone JA, Smith-Weller T, Franklin G, Swanson P, Longstreth WT Jr, Checkoway H. Pesticides and risk of Parkinson disease: a population-based case-control study. Arch Neurol. 2005;62(1):91–5, 10.1001/archneur.62.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wechsler LS, Checkoway H, Franklin GM, Costa LG. A pilot study of occupational and environmental risk factors for Parkinson’s disease. Neurotoxicology. 1991;12(3):387–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Corrigan FM, Wienburg CL, Shore RF, Daniel SE, Mann D. Organochlorine insecticides in substantia nigra in Parkinson’s disease. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2000;59(4):229–34, 10.1080/009841000156907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Davis SD, Kator SF, Wonnett JA, Pappas BL, Sall JL. Neurally mediated hypotension in fatigued Gulf War veterans: a preliminary report. Am J Med Sci. 2000;319(2):89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rayhan RU, Stevens BW, Raksit MP, Ripple JA, Timbol CR, Adewuyi O, et al. Exercise challenge in Gulf War Illness reveals two subgroups with altered brain structure and function. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e63903, 10.1371/journal.pone.0063903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Haley RW, Charuvastra E, Shell WE, Buhner DM, Marshall WW, Biggs MM, et al. Cholinergic autonomic dysfunction in veterans with Gulf War illness: confirmation in a population-based sample. JAMA. 2013;70(2):191–200, 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Maule AL, Janulewicz PA, Sullivan KA, Krengel MH, Yee MK, McClean M, et al. Meta-analysis of self-reported health symptoms in 1990–1991 Gulf War and Gulf Warera veterans. BMJ Open. 2018;8(2):e016086, 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Stiasny-Kolster K, Möller JC, Heinzel-Gutenbrunner M, Baum E, Ries V, Oertel WH. Validation of the restless legs syndrome screening questionnaire (RLSSQ). Somnologie. 2009;13(1):37–42, 10.1007/s11818-009-0402-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]