Summary

Background

Circadian rhythms regulate immune cell activity, influencing responses to vaccines, and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). Early time-of-day administration (ToDA) of singe-agent ICIs has been associated with improved overall survival (OS) in patients with metastatic “immunotherapy sensitive” cancers. However, the impact of ToDA on OS in patients receiving combination therapy with ICIs and chemotherapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) remains unclear.

Methods

This retrospective study included patients from oncology units in Paris, France (Cohort 1) and Hunan, China (Cohort 2) who received first-line immuno-chemotherapy for stage IIIC or IV NSCLC between January 2018 and October 2023. The primary outcome was OS. The median ToDA of the initial four ICI infusions was computed for each patient. Hazard ratio (HR) for death or progression were determined using cut-off times ranging from 10:30 to 13:00. Kaplan Meier and Cox models were used to estimate OS and progression-free survival (PFS) adjusting for main patient characteristics.

Findings

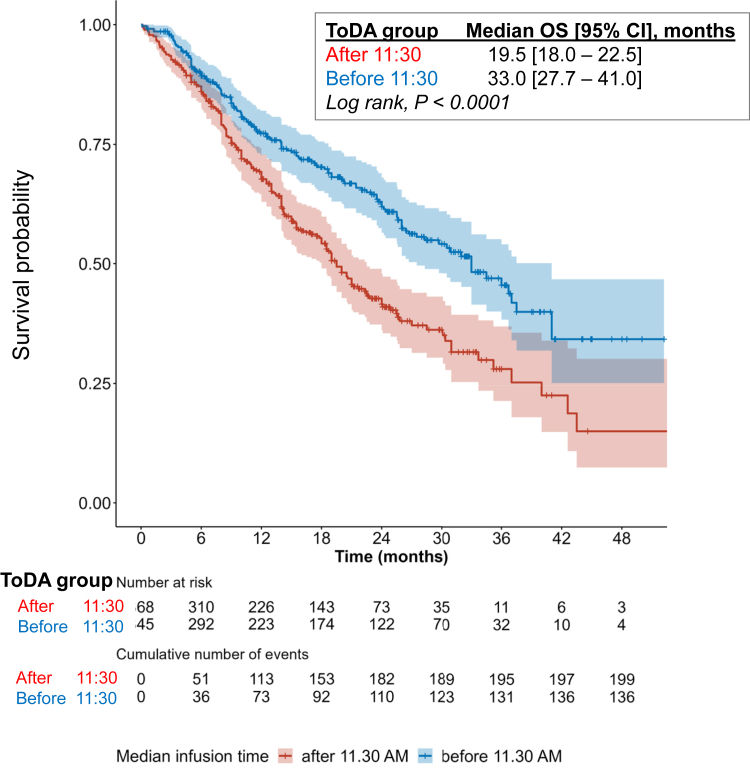

The study included 713 patients (Cohort 1, n = 165; Cohort 2, n = 548). Pembrolizumab was the most common ICI (51%), which was used with either pemetrexed-carboplatin/cisplatin (49%) or paclitaxel-carboplatin (51%). The optimal ToDA cut-off was 11:30, with patients receiving immuno-chemotherapy before 11:30 showing significantly improved OS (33.0 months [95% CI, 27.5–41.0] vs 19.5 months [18.0–22.5]; p < 0.0001). Multivariable analysis confirmed that earlier ToDA was associated with better OS (adjusted HR = 0.47 [95% CI, 0.37–0.60]). ToDA significantly impacted OS in each cohort and for PFS and response rates in each cohort and the pooled data.

Interpretation

This sizeable bi-continental study provided real-world evidence that morning administration of standard first-line immuno-chemotherapy was associated with improved clinical outcomes compared to afternoon dosing in patients with NSCLC. Randomised trials are required to validate this finding and inform recommendations for clinical practice.

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China (82222048, 82003206, 82173338, and 82102747).

Keywords: Circadian rhythm, Chronotherapy, Immune checkpoint inhibitors, Time of day of administration, Lung cancer, Immuno-chemotherapy

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Immunotherapy in combination with chemotherapy has become the standard first-line treatment for advanced non-small cell lung cancer without actionable driver gene mutations. Despite its widespread use, approximately 40% of patients fail to derive clinical benefit from this regimen, highlighting the urgent need for innovative therapeutic strategies to improve treatment outcomes. Over 20 retrospective studies have demonstrated a near doubling in progression-free and/or overall survival in patients with advanced or metastatic cancer, including non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), when single-agent immune checkpoint inhibitors are administered at an early time of day. Preclinical studies in murine models further suggest that the onset of daily activity is consistently associated with enhanced anti-tumour efficacy of ICIs. This phenomenon is attributed to the circadian rhythms that govern immune and myeloid cell function, trafficking, and the expression of PD-1 in immune cells, thereby influencing response to immunotherapy.

Added value of this study

This study represents the first investigation into the survival implications of the timing of immuno-chemotherapy administration in patients with advanced NSCLC across two continents with markedly distinct ethnic and lifestyle factors. We conducted a comprehensive analysis of longitudinal clinical and infusion data from a total of 713 patients who received treatment at leading oncology centres in Paris, France and Changsha, China. Focussing on patients diagnosed with advanced or metastatic NSCLC, our findings revealed that administering ICI infusions before midday (11:30) during the four courses of immuno-chemotherapy was associated with a nearly two-fold increase in both progression-free and overall survival, compared to patients receiving the majority of their treatment after 11:30. Multivariate analysis confirmed that morning ICI infusion was an independent predictor of improved survival outcomes.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our findings provide valuable insights into optimising the effectiveness of the immuno-chemotherapy regimen by emphasising the potential benefit of scheduling ICI infusions earlier in the day. These results complement existing evidence on the timing of ICI monotherapy across seven cancer types, which similarly reported significant improvements in treatment effectiveness when administered in the morning or early afternoon. The critical timing data presented in this study could serve as the foundation for designing randomised clinical trials and translational chronotherapy studies aimed at further validating the therapeutic benefits of treatment timing. Such studies would inform routine clinical practice, facilitating the personalisation of immuno-chemotherapy delivery schedule based on circadian principles. These results will also enhance the growing body of research linking the circadian timing system and the immune system, further advancing the field of precision circadian medicine.

Introduction

Differences in overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) have been reported as a function of the time-of-day administration (ToDA) of single-agent immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) in numerous retrospective studies, which collectively involve over three thousand patients.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 A meta-analysis encompassing the first thirteen studies has shown that both OS and PFS were nearly doubled in patients who received their single-agent ICI infusions predominantly in the morning or in the early afternoon, compared to those receiving treatment at later times.3 The survival impact of ToDA were found to be remarkably consistent across seven different tumour types, including non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), malignant melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, bladder, oesophageal, and gastric cancers.3,5,6 Experimental studies have revealed the strict regulation of immune cell trafficking and programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) expression by the circadian timing system.7, 8, 9 Specifically, circadian rhythms govern the infiltration of tumours by CD8+ T cells, dendritic cells–the key immune cells involved in the action of ICIs against cancer cells.7,8 Additionally, PD-1, the principal target of anti-PD-1 inhibitors, exhibits a rhythmic expression pattern in immune cells throughout the 24-h cycle.7,9,10 Large amplitude circadian rhythms also characterise the circulation, function, and proliferation of immune cells in humans.10, 11, 12

With the current standard of care for advanced or metastatic NSCLC having shifted from single-agent anti-PD-1 therapy to a combination of ICI and chemotherapy during the initial four treatment cycles, we hypothesised that early ToDA ICI dosing could result in a 50% increase in OS, in line with prior findings on single-agent ICI therapy. This hypothesis is further supported by data from five clinical studies that reported the association between ToDA of single-agent immunotherapy and survival outcomes,5,13, 14, 15, 16 as well as by preclinical studies in murine models demonstrating the critical role of circadian timing in the effectiveness of the first dose of an ICI. It is also plausible that circadian rhythms may influence ICI pharmacokinetics, particularly during the early stages of treatment. A well-established pharmacokinetic principle is that drug plasma levels reach a plateau after five administrations, spaced according to the drug's half-life.16,17 For anti-PD-1 agents like pembrolizumab, the average half-life is 2–3 weeks in patients with NSCLC, with a plateau in plasma concentrations typically occurring after 15–20 weeks, depending on treatment intervals and patient characteristics.5,13,18,19 Thus, potential pharmacokinetic effects relating to the timing of ICI administration could influence peak concentrations, tissue distribution, and drug clearance prior to the establishment of the plateau phase, which corresponds mainly to the first four treatment cycles.20,21

In this study, we investigate the potential impact of the daily timing of the first four immuno-chemotherapy infusions on OS and PFS in chemotherapy-naïve patients with advanced or metastatic NSCLC. We analyse treatment outcomes in two independent cohorts from France and China with distinct ethnic and lifestyle differences as well as data pooled cohort from these two cohorts.22,23 We first calculated the hazard ratios (HR) for earlier death or disease progression in relation to the median ToDA of a PD-1 inhibitor combined with chemotherapy, separately for the French and a Chinese cohorts. Given the strong consistency of the results across these cohorts, we then examined the relationship between HRs and ToDA as a continuous variable in the pooled data, reporting treatment outcomes based on the timing of anti-PD-1 infusion.

Methods

Study objective, design and ethics

This study aimed to identify the clinical relevance of the ToDA for the initial four courses of anti-PD-1 ICI combined with chemotherapy as first-line treatment for advanced or metastatic NSCLC. Grounded on various evidence, including prior unpublished analyses of our own data,1 a meta-analysis of 13 reported studies of single-agent ICI timing effect,3 and an extensive follow-up literature survey,24 our current investigation postulated that the timing of administering the four initial treatment courses was critical for patient outcomes. Moreover, the tumour response to these initial treatment courses—either objective response or disease control—guide the subsequent treatment decisions, such as continuing immunotherapy alone, or extending a ‘lighter’ immuno-chemotherapy for several months or years.

We conducted a large, international, retrospective study, pooling deidentified individual patient data from two cohorts: Cohort 1 (France) and Cohort 2 (China). Cohort 1 comprised patients with metastatic NSCLC who received treatment from Le Raincy-Montfermeil Hospital in Montfermeil and Avicenne University Hospital in Bobigny, France between February 2019 and October 2023. Cohort 2 included patients with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC who received treatment from Hunan Hospital in Changsha, China between January 2018 and June 2022.

Ethics statement

The study procedures adhered to the ethical standards set forth by the institutional and national research committees and followed the 2013 revision of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol for Cohort 1 was approved by the Internal Review Boards of Le Raincy-Monfermeil Hospital (IRB 200224) and Avicenne Hospital (CLEA-2023-n°337). The study protocol for Cohort 2 was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hunan Cancer Hospital (2022015). The study conformed to the STROBE guidelines.25

Patient selection

For both cohorts, data (Table S1) were collected from consecutive patients who met the following inclusion criteria: (i) histologically- or cytologically-documented diagnosis of NSCLC; (ii) advanced or metastatic disease; (iii) World Health Organization (WHO) performance status of 0, 1 or 2; (iv) negative tumour status for actionable driver gene mutations in EGFR, ROS1, or ALK; (v) at least one course of standard first-line treatment combining an anti-PD-1 ICI with either pemetrexed-carboplatin (or cisplatin) or paclitaxel-carboplatin. Tumour expression of PD-L1 was categorised as <1%, 1–49%, and 50–100% where data were available, in accordance with standard recommendations.22,23,26,27 Patients with brain metastases that did not require glucocorticoid therapy were included, whereas those receiving >10 mg/day of glucocorticoid for any reason were excluded. Patients with missing data on ICIs infusion timing for any of the first four treatment courses were excluded from analyses.

Treatment procedures

Pembrolizumab or another anti-PD-1 ICI (i.e., sintilimab, toripalimab, tislelizumab, or camrelizumab) was administered at a fixed dose of 200 mg for each course. The ICI was infused intravenously over 30 min, followed by standard chemotherapy protocols. For non-squamous NSCLC, chemotherapy consisted of pemetrexed combined with either carboplatin or cisplatin; for squamous cell carcinoma, paclitaxel plus carboplatin were used. The treatment sequence and infusion duration for the chemotherapy combinations were fixed at 2.5 h for pemetrexed plus carbo/cisplatin and 4 h for paclitaxel plus carboplatin. As a result, the total duration of each immuno-chemotherapy course was 3 h and 4.5 h, respectively.

Subsequent to the initial four courses, patients could continue receiving pembrolizumab or another ICI as a single-agent or in combination with pemetrexed every 3 weeks until disease progression, severe toxicity, or cessation of therapy for medical or patient reasons.22,23 For both cohorts, follow-up visits and laboratory tests were conducted before each treatment course, while imaging studies were performed after the second and fourth courses, and thereafter every 2–4 courses, until treatment termination.

Immuno-chemotherapy treatment and schedule

The timing of ICI-chemotherapy infusion was coordinated by the day hospital coordinator based on the availability of out-patient beds or armchairs. For logistical reasons, subsequent ICI infusion times remained approximately consistent for each patient.

The precise timing of ICI infusion times was recorded in both cohorts. In Cohort 1, the exact date and time (hours, minutes) of the drug solution delivery by the pharmacy to the outpatient clinics, and the start and end times for ICI and chemotherapy infusions were documented in patient charts by the nursing personnel. In Cohort 2, similar documentation procedures were followed, with both the physician's orders and nursing drug administration times meticulously recorded. Treatments continued until disease progression, occurrence of unacceptable toxicities, or death.

Assessments

De-identified electronic medical records were reviewed at each site to collect pre-selected baseline patient and tumour characteristics, including WHO performance status, type of ICI, the time ICI administration started for each of the initial four infusions (both date and clock hour), and the number of courses administered. Anti-tumour responses were assessed using computed tomography (CT) scans, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and/or positron emission tomography (PET) scan, typically after every two to three courses. Tumour responses was classified according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST) v1.1 criteria as complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), or progressive disease (PD).28 Adverse events and blood test results were not collected for this study. Data were reviewed independently by two clinicians, in conjunction with the lead oncologist for each patient, to ensure consistency, accuracy, and plausibility.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint was OS, defined as the time from the first ICI administration to all-cause death or the last follow-up visit for patients last seen alive. Secondary endpoints included progression-free survival (PFS) and best response rate. PFS was defined as the time from the first ICI administration to death or disease progression (whichever came first) or the last follow-up visit for patients last seen alive and without disease progression. The best response rate was defined as the percentage of patients whose best tumour response was either a PR or a CR.

Statistical considerations

Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were expressed either as mean ± standard deviation or median and interquartile range (IQR). Normality assumption was assessed graphically. The median follow-up was estimated using the reverse Kaplan–Meier method. The median ToDA was defined based on the administration start time for the initial four immuno-chemotherapy courses. The intra-patient coefficient of variation was calculated as the ratio of the SD to the mean of the four infusion times for each individual patient. The median between-patient coefficient of variation for ICI infusion times, along with its interquartile range, was also computed for each cohort.

Two complementary sets of analyses were conducted to assess the relationship between infusion timing and the risks of earlier mortality or disease progression. First, infusion time was analysed as a categorical variable, where timing cut-offs ranging from 10:30 to 13:00 in 30-min intervals were explored. Patients were classified as either “Before” or “After” each cut-off, based on their median ToDA. In the “Before cut-off time” group, patients received two, three or four courses before the cut-off, while those in the “After cut-off time” group received one or no courses before the cut-off time. Patient characteristics between the groups were compared using Student's t-test (or non-parametric Wilcoxon test) for quantitative variables, Chi-square test (or Fisher's exact test) for non-ordered categorical variables, and Cochran–Armitage test for ordered categorical variables (WHO performance status and PD-L1 expression). OS and PFS were estimated using Kaplan–Meier methods and compared using the log-rank test. The associations between ToDA cut-off and OS or PFS were evaluated using the Cox regression models, adjusting for country, sex, age, WHO performance status, tumour stage, PD-L1 expression, number of metastatic sites, and type of immunotherapy and chemotherapy regimen administered.29 Unadjusted Cox models were also performed within subgroups to explore the consistency of ToDA effects on OS and PFS.

Second, ToDA was analysed as a continuous variable, using Cox regression models incorporating periodic restricted cubic splines (RCS) to account for the periodic nature of infusion time and the risks of death and disease progression. Periodic RCS is a useful extension of RCS for handling periodic data, such as infusion time.30 These models were used to estimate HR and 95% confidence interval (CI) for different infusion times relative to 13:00 time point. The number of knots was selected to minimise the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC).31 All models were adjusted for the same factors as mentioned earlier.

The association between ToDA cut-off and response rates was assessed using a logistic regression model, adjusting for the same variables.

Missing data were handled by assuming it was missing at random, with categorical variable having missing data being assigned under a ‘Missing’ category.

The primary analysis was conducted on pooled deidentified data from both cohorts. Sensitivity analyses were performed for exploratory purposes within each cohort. The same cut-off times were studied following the same methods as described above.

The p-value was set a priori at 0.05 for all analyses and 95% CIs of the estimates were calculated. All tests were two-sided. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS® v26.0 (Chicago, IL, USA) and R® v4.3.0.32 Periodic RCS were implemented using the peRiodiCS R package.33

Role of the funders

The funders had no role in the experiment design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation, manuscript writing, or any aspect of this study.

Results

Patient characteristics and study flow

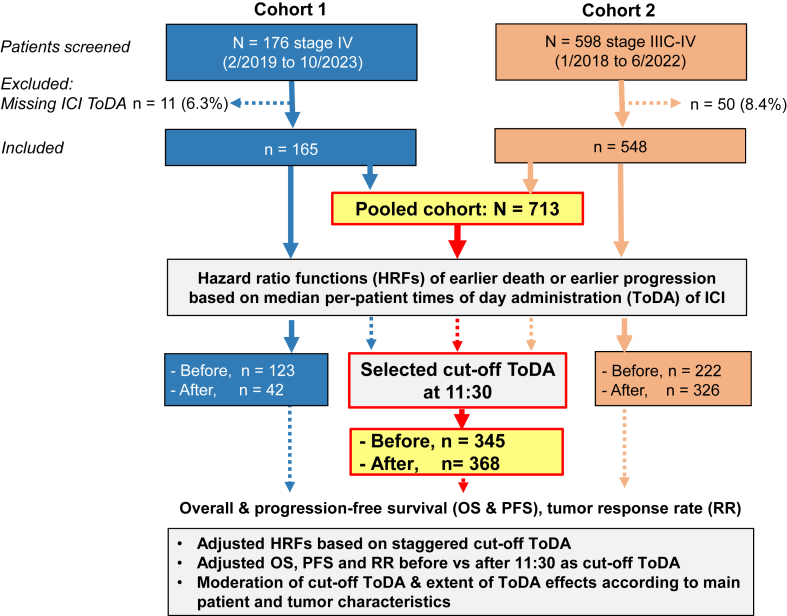

Due to missing ToDA of ICI infusions, 165 out of 176 patients (93.8%) in Cohort 1, and 548 out of 598 patients (91.6%) in Cohort 2 met selection criteria (Fig. 1). The included patients initiated first-line immuno-chemotherapy between February 5, 2019 and October 9, 2023 for Cohort 1, and from January 1, 2018 to June 30, 2022 for Cohort 2 (Table S2). Of the 713 patients, 83.9% were male, with a median age of 62 [IQR, 56–68] year. The majority (93.5%) had a WHO performance status of 0 or 1; and 87.8% presented with Stage IV disease (Table 1). Patients had a median of two metastatic sites, including bone (33.5%), brain (17.7%), and liver (11.6%) involvement. PD-L1 expression was detected in the tumours of 71.1% of the 540 patients who underwent such testing. The predominant ICI administered was pembrolizumab (50.5%). Immunotherapy was combined with paclitaxel-carboplatin or pemetrexed-carboplatin in 51.3% and 48.2% of the patients, respectively, while three patients (0.4%) received pemetrexed-cisplatin. The median ToDA of the per-patient median ToDA of the initial four courses 11:36 [IQR, 10:49–12:48]. The median coefficient of variation of ToDA within individual patients was 9.9% [IQR, 5.2–18.1]. Overall, patients received a median of 9 courses [IQR, 5–18] of immunotherapy, with or without chemotherapy throughout the protocol treatment (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Consort diagram: study flow and endpoints in each cohort, and in the pooled cohort. This flow chart illustrates the inclusion and exclusion process of the patients across both cohorts, detailing the study design and key study endpoints in Cohort 1 (France) and Cohort 2 (China), as well as the pooled analysis.

Table 1.

Main patient characteristics.

| Characteristics | Cohort 1 (n = 165) | Cohort 2 (n = 548) | Overall (n = 713) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 120 (72.7%) | 478 (87.2%) | 598 (83.9%) |

| Female | 45 (27.3%) | 70 (12.8%) | 115 (16.1%) |

| Age | |||

| Median [IQR] | 63.8 [56.2–70.0] | 61.0 [55.8–67.0] | 62.0 [56.0–68.0] |

| (Range) | (37.5–85.1) | (40.0–79.0) | (37.5–85.1) |

| Race | |||

| Asian | 0 | 548 (100%) | 548 (76.9%) |

| White | 165 (100%) | 0 | 165 (23.1%) |

| Smoking (yes) | 158 (95.8%) | 440 (80.3%) | 598 (83.9%) |

| WHO performance score | |||

| 0 | 43 (26.4%) | 87 (15.9%) | 130 (18.3%) |

| 1 | 89 (54.6%) | 446 (81.4%) | 535 (75.2%) |

| 2 | 31 (19.0%) | 15 (2.7%) | 46 (6.5%) |

| Missing | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Histological type | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 111 (67.3%) | 284 (51.8%) | 395 (55.4%) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 25 (15.2%) | 254 (46.4%) | 279 (39.1%) |

| Poorly differentiated carcinoma | 29 (17.6%) | 10 (1.8%) | 39 (5.5%) |

| Stage | |||

| IIIC | 0 (0.0%) | 87 (15.9%) | 87 (12.2%) |

| IV | 165 (100.0%) | 461 (84.1%) | 626 (87.8%) |

| Main sites or metastases | |||

| Brain | 55 (33.7%) | 71 (13.0%) | 126 (17.7%) |

| Liver | 35 (21.2%) | 48 (8.8%) | 83 (11.6%) |

| Bone | 76 (46.1%) | 163 (29.7%) | 239 (33.5%) |

| Number of metastatic sites | |||

| Median [IQR] | 3 [2–4] | 1 [1–2] | 2 [1–2] |

| (Range) | (1–11) | (0–5) | (0–11) |

| PD-L1 tumour proportion score | |||

| <1% | 59 (37.6%) | 97 (25.3%) | 156 (28.9%) |

| 1%–49% | 56 (35.7%) | 149 (38.9%) | 205 (38.0%) |

| ≥50% | 42 (26.8%) | 137 (35.8%) | 179 (33.1%) |

| Missing | 8 | 165 | 173 |

| Chemotherapy regimen administered | |||

| Pemetrexed + Carboplatin | 122 (73.9%) | 222 (40.5%) | 344 (48.2%) |

| Paclitaxel + Carboplatin | 40 (24.2%) | 326 (59.5%) | 366 (51.3%) |

| Pemetrexed + Cisplatin | 3 (1.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (0.4%) |

| Immune checkpoint inhibitor regimen administered | |||

| Pembrolizumab | 165 (100.0%) | 195 (35.6%) | 360 (50.5%) |

| Sintilimab | 0 (0.0%) | 202 (36.9%) | 202 (28.3%) |

| Toripalimab | 0 (0.0%) | 43 (7.8%) | 43 (6.0%) |

| Tirelizumab | 0 (0.0%) | 55 (10.0%) | 55 (7.7%) |

| Camrelizumab | 0 (0.0%) | 53 (9.7%) | 53 (7.4%) |

| Median time of day when the first four ICI infusions were administered per patient (clock hours, hh:mm) | |||

| Median [IQR] | 10:39 [9:56–11:30] | 11:51 [11:12–13:37] | 11:36 [10:49–12:48] |

| (Range) | (8:53–16:59) | (9:16–18:11) | (8:53–18:11) |

| Within-patient coefficient of variation of time of ICI infusion (%) | |||

| Median [IQR] | 6.4 [3.5–11.1] | 11.2 [5.9–19.8] | 9.9 [5.2–18.1] |

| (Range) | (0–33) | (0–35) | (0–35) |

| Number of ICI + chemotherapy courses per patient | |||

| Median [IQR] | 4 [3–4] | 4 [4–6] | 4 [4–5] |

| (Range) | (1–6) | (1–26) | (1–26) |

| Total number of ICI infusions (±chemotherapy) administered per patient | |||

| Median [IQR] | 7 [3–14] | 13.5 [6–19] | 9 [5–18] |

| (Range) | (1–49) | (1–40) | (1–49) |

| N of patients with local radiotherapy post ICI-chemotherapy (%) | 47 (28.5%) | 27 (4.9%) | 74 (10.4%) |

IQR, interquartile range.

The median per-patient ToDA was 10:39 [IQR, 9:57–11:30] for Cohort 1 and 11:51 for Cohort 2, with both distribution patterns skewed to the left (Figure S1). The median follow-up duration was 24.5 months [95% CI, 23.2–25.6]. The OS and PFS curves of the whole cohort revealed a median OS of 25.5 months [95% CI, 22.5–29.7] and a median PFS of 9.0 months [95% CI, 8.3–9.9] (Figure S2).

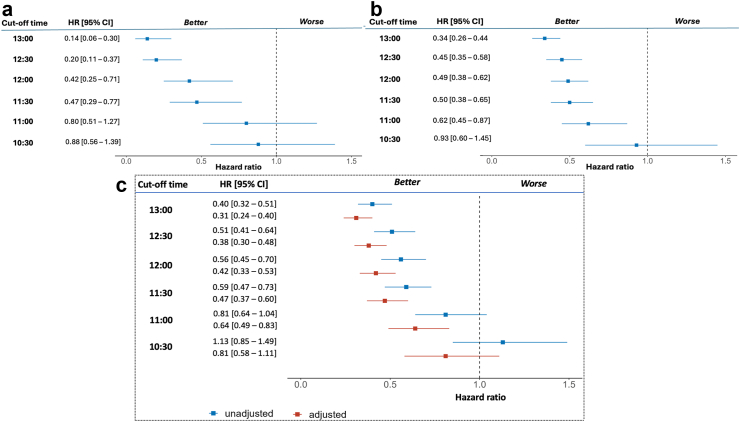

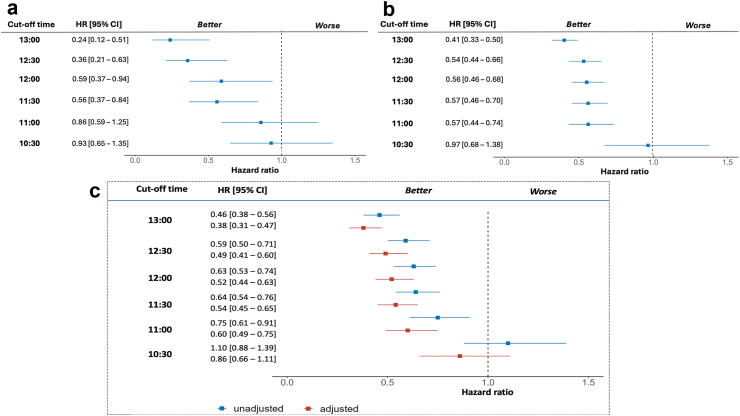

Determination of ToDA cut-off for differentiating survival outcomes

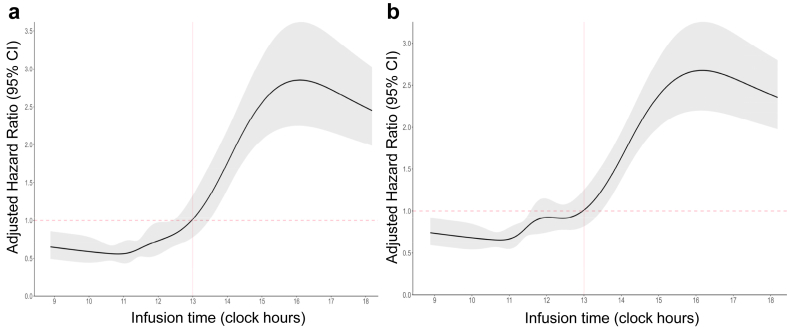

The HR for both OS (Fig. 2) and PFS (Fig. 3) showed similar trends across the individual cohorts and the pooled data. Unadjusted HRs for earlier death and earlier disease progression were statistically significant for ToDA cut-off of 11:30 for both cohorts and the pooled data. At this cut-off ToDA, the HRs for earlier death were 0.47 [95% CI, 0.29–0.77] for Cohort 1 (Fig. 2a) and 0.50 [95% CI, 0.38–0.65] for Cohort 2 (Fig. 2b), with similar results observed for the pooled cohort (HR = 0.59 [95% CI, 0.47–0.73]; Fig. 2c). The HRs for earlier progression were also comparable in both cohorts and pooled cohort, with HR of 0.56 [95% CI, 0.37–0.84] for Cohort 1, 0.57 [95% CI, 0.46–0.70] for Cohort 2, and 0.64 [95% CI, 0.54–0.76] for the pooled cohort (Fig. 3a–c). Statistically significant HRs were also identified for ToDA cut-off times staggered by 30 min, ranging from 11:30 to 13:00, with overlapping 95% CI in each individual cohort and in the pooled cohort, regardless of whether unadjusted or adjusted data were analysed (Figs. 2 and 3). Similarly, when ToDA was modelled as a continuous variable, a significant and gradual increase in the risk of death and disease progression was observed for afternoon administrations, with a protective effect associated with morning administrations. The inflection point appeared to occur between 11:00 and 12:00 (Fig. 4a and b).

Fig. 2.

Hazard Ratios (HRs) for earlier death as a function of cut-off time-of-day administration (ToDA) of immuno-chemotherapy. Forest plots showing the unadjusted HR function in Cohort 1 (a), Cohort 2 (b), and the pooled cohort (c). Adjustment factors included country, sex, age, WHO performance status, tumour stage, PDL-1 expression, number of metastatic sites, immunotherapy agent, and chemotherapy protocol. The left column presents tested cut-off ToDAs, spaced 30-min apart, ranging from 10:30 (bottom row) to 13:00 (upper row). The middle column shows the HRs and their respective 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each tested cut-off ToDA. The right column provides a graphical illustration of the HRs and their respective 95% CIs. Note: The cut-off ToDA at clock hour 11:30 appears as the first timepoint that consistently differentiates the overall survival outcomes of patients receiving the majority of their ICI infusions Before vs After 11:30. Overlapping 95% CIs indicate that later ToDA cut-off points do not offer additional discriminatory power compared with 11:30.

Fig. 3.

Hazard Ratios (HRs) for earlier progression as a function of cut-off time-of-day administration (ToDA) of immuno-chemotherapy. Forest plots illustrating the unadjusted HR function in cohort 1 (a) and cohort 2 (b), and unadjusted and adjusted HR function in pooled cohort (c). Adjustment factors included: country, sex, age, WHO performance status, tumour stage, PD-L1 expression, number of metastatic sites, immunotherapy agent, and chemotherapy protocol. The left column presents tested cut-off ToDAs spaced 30-min apart, ranging from 10:30 (bottom row) to 13:00 (upper row). The middle column shows the HRs and their respective 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each tested cut-off ToDA. The right column provides a graphical illustration of the HRs and their respective 95% CIs. Note: The cut-off ToDA at clock hour 11:30 appears as the first timepoint that consistently differentiates the progression-free survival of patients receiving the majority of their ICI infusions Before vs After 11:30. Overlapping 95% CI indicate that later ToDA cut-off points do not offer a greater discriminatory effect compared with 11:30.

Fig. 4.

Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis of (a) earlier mortality and (b) earlier disease progression using periodic restricted cubic splines (RCS). The black lines represent the fitted curves of the association between time-of-day administration (ToDA) and the estimated hazard ratio (HR) after adjustment. The shaded areas represent the 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The models were adjusted for the following covariates: country, sex, age, WHO performance status, tumour stage, PD-L1 expression, number of metastatic sites, type of immunotherapy, and chemotherapy protocol. The periodic RCS plot used the infusion time at 13.00 as the reference for HR calculation.

Efficacy of immuno-chemotherapy administered “Before” or “After” 11:30

A total of 345 patients were assigned to the “Before 11:30” group and 368 patients to the “After 11:30” group (Table S2). Compared to the “Before 11:30” group, the “After 11:30” group included slightly higher proportion of patients with non-squamous cell NSCLC, fewer metastatic sites, and higher tumour PD-L1 expression, potentially favouring later ToDA treatments.

In this dichotomised patient population, large and statistically significant differences were observed in both OS (Fig. 5) and PFS (Fig. 6) curves. Median OS were 33.0 months [95% CI, 27.5–41.0] in the “Before 11:30” group, compared to 19.5 months [95% CI, 18.0–22.5] in the “After 11:30” group (p from log-rank <0.0001). The respective median PFS times were 11.8 months [95% CI, 9.9–14.0] and 7.2 months [95% CI, 6.6–8.5] (p from log-rank <0.0001). Log-rank test demonstrated significant differences in both OS and PFS for each cohort using 11:30 as a cut-off (Figures S3 and S4).

Fig. 5.

Overall survival curves as a function of time-of-day administration (ToDA) of immuno-chemotherapy in the pooled cohort. Kaplan–Meier curve comparing the overall survival (OS) of the 368 patients who received a majority of the first four immuno-chemotherapy courses before 11:30, and 345 patients who received theirs after 11:30. P-values were calculated using log-rank test.

Fig. 6.

Progression-free survival curves as a function of ICI ToDA in the pooled cohort. Kaplan–Meier curve comparing the progression-free survival (PFS) of the 368 patients who received a majority of the first four immuno-chemotherapy courses before 11:30, and 345 patients who received theirs after 11:30. P-values were calculated using log-rank test.

Response rates were also higher in the “Before 11:30” group in Cohort 1 (63.4% vs 45.9%, p = 0.014), Cohort 2 (60.8% vs 53.1%, p = 0.036), and the pooled cohort (61.7% vs 52.4%, p from Χ2 = 0.002) (Figure S5). Due to a more rapid disease progression following treatments administered after 11:30, the immuno-chemotherapy protocol was discontinued earlier for treatment failure, resulting in fewer treatment courses and less loco-regional radiotherapy in the “After 11:30” group (p from Χ2 < 0.001) (Table S2).

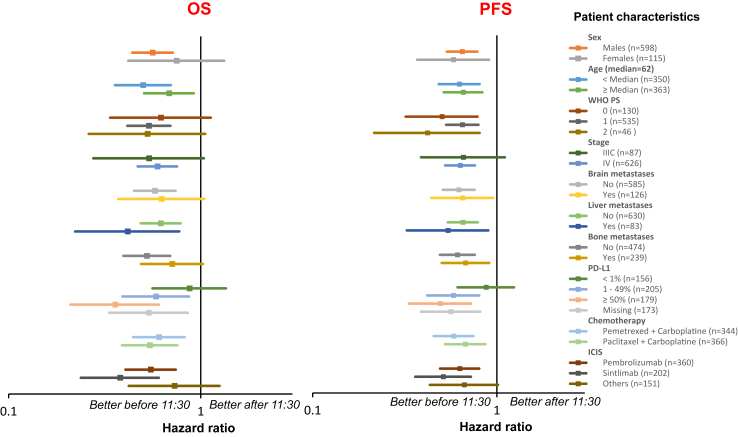

Multivariable analyses of pooled cohort data and relevance of ToDA in patient subsets

Multivariable analyses revealed statistically significant effects of ToDA on both OS and PFS, with adjusted HRs shown for staggered ToDA times between 10:30 to 13:00 (Figs. 2 and 3). Using 11:30 as the cut-off ToDA, the adjusted HR for earlier death was 0.47 [95% CI, 0.37–0.60]. Performance status, PD-L1 expression and chemotherapy protocol were identified as jointly significant prognostic indicators, with improved outcomes observed in patients with a PS of 0 (HR, 0.30 [95% CI, 0.19–0.48]), or u PD-L1 expression ≥50% (HR, 0.54 [95% CI, 0.39–0.76]) or those receiving paclitaxel-carboplatin chemotherapy (HR, 0.77 [95% CI, 0.61–0.98]) (Figure S6).

The adjusted HR for earlier progression was 0.54 [95% CI, 0.45–0.65], with performance status, tumour PD-L1 expression, and chemotherapy protocol serving as joint prognostic factors (Figure S7). Subgroup analyses confirmed that the administration of the majority of the initial four immuno-chemotherapy courses before 11:30 improved both OS and PFS, irrespective of patient or tumour characteristics, except for tumour PD-L1 expression below 1%, where the relevance of 11:30 as a ToDA cut-off appeared diminished (Fig. 7). Logistic regression analysis further confirmed the advantage of ICI infusions “Before 11:30” for response rates, with an unadjusted odds ratio (OR) of 1.48 [95% CI, 1.09–2.00] and adjusted OR of 1.56 [95% CI, 1.13–2.17].

Fig. 7.

Impact of the time-of-day administration (ToDA) effects in patient subgroups from the pooled cohort. Forest plots showing the hazard ratios (HRs) for earlier death (Left panel) or earlier disease progression (Right panel) using clock hour 11:30 as cut-off ToDA in selected patient subgroups (Right column). HRs are presented with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each subgroup analysis.

Post-study protocol treatments

As a result of the longer PFS, patients in the “Before 11:30” group received more ICI-based courses (median, 14 courses; IQR, 6–21; extremes, 1–49) compared to the “After 11:30” group (median, 7; IQR, 4–10; 1–40) (p from Wilcoxon <0.001). A higher proportion of patients in the early ToDA group (n = 54, 15.7%) also received palliative radiotherapy compared to the late ToDA group (n = 20, 5.4%) (p from Fisher's exact test = 0.01).

Discussion

This study demonstrates that the timing of ICI infusion, specifically the ToDA, is a critical determinant of treatment outcomes oin713 patients receiving first-line immuno-chemotherapy for NSCLC. Notably, patients who received the initial three or four ICI infusions before 11:30 exhibited significantly longer OS and PFS, alongside significantly higher response rates, compared to those who received the infusion after 11:30. Remarkably, the median survival in the ‘morning’ group was nearly one year longer than that of the ‘afternoon’ group within this large pooled cohort. Furthermore, the ‘morning’ group consistently had more favourable treatment outcomes than the ‘afternoon’ group across both cohorts in terms of OS, PFS and response rates. When using 11:30 as cut-off time for ToDA, the unadjusted HRs for earlier death were 0.47 [95% CI, 0.29–0.77] for Cohort 1, and 0.57 [95% CI, 0.46–0.70] for Cohort 2, and 0.59 [95% CI, 0.47–0.73] for the pooled cohort, with an adjusted HR was 0.47 [95% CI, 0.37–0.60]. The selection of 11:30 as a likely ToDA cut-off time was further supported by its alignment with inflection points in the temporal relation between HRs and ToDA, as evidenced by Cox models incorporating ToDA as a continuous variable with periodic RCS.

The similarities observed in treatment outcomes across the two distinct patient cohorts highlight the consistency of ICI timing responses in patients with NSCLC from both continents. These results are in alignment with the findings from our recent meta-analysis of 13 retrospective studies, which demonstrated that early ToDA of single-agent ICIs nearly doubled both OS and PFS in 1667 patients with lung, kidney, bladder or oesophageal cancer or melanoma.3 Similar findings were reported for single-agent pembrolizumab in a large cohort of 361 patients with metastatic cancer, of whom 80% had NSCLC, with 11:30 also identified as a relevant cut-off for ToDA.4 In total, 24 out of 25 retrospective studies of single-agent ICI therapy support the survival advantage of early ToDA across cancer types (Suppl. References list; reviewed in 41).

This large cohort study, involving the combination of immunotherapy with chemotherapy, provides additional validation for the hypothesis that circadian rhythms also play an important role in the efficacy of immuno-chemotherapy in patients with NSCLC. Specifically, the administration of immuno-chemotherapy in the morning was associated with nearly twofold increase in OS, independent of prognostic indicators, and genetic background (i.e., Caucasian vs Chinese).

This study presents several strengths, including the involvement of 713 patients across two cohorts from different continents, with similar patient characteristics, except their ethnicity/genetic origin and lifestyle factors. All patients were treated according to the current standard of care. However, body mass index and socio-economic determinants were not considered in the analysis, as these are not typically regarded as major prognostic factors for immuno-chemotherapy outcomes, although they may exert some influence. The primary limitation of this study is its retrospective design, which may have introduced minor imbalances that could have biased the outcomes. For example, certain factors might have favoured the “After 11:30” group, while others might have favoured the “Before 11:30” group. These potential confounders were addressed by adjusting the HRs with established prognostic factors, such as WHO performance status, tumour stage, PD-L1 expression, and number of metastatic sites, as well as additional potential confounders such as ethnicity, sex, age, immunotherapy agent, and chemotherapy protocol, through multivariable analyses of OS and PFS.

Importantly, the robustness of the circadian hypothesis was further substantiated by the fact that the magnitude of the timing effect was even more pronounced following the adjustments using the main prognostic factors. The deidentified data from two continents reinforce the conclusion that the significant survival benefit derived from immuno-chemotherapy administration before 11:30 is not specific to any particular healthcare system, genetic predisposition, or lifestyle factors.

In mammals, the Circadian Timing System (CTS) rhythmically regulates cellular processes such as metabolism, proliferation, and death, in addition to modulating drug responses over a 24-h cycle.11 The CTS is governed by a network of molecular circadian clocks in each cell, which are coordinated by the supra-chiasmatic nuclei, a hypothalamic pacemaker. This pacemaker also adjusts the timing of the molecular clocks in response to environmental cues, generating physiological rhythms, including those involved in rest-activity cycles, body temperature, and glucocorticoid secretion.11,34 The molecular clocks are composed of 15 key genes, including Bmal1, Clock, Rev-Erb's, Per's, and Cry's, which are present in immune cells involved in immune function and trafficking.7, 8, 9, 10 Consequently, the timing of drug administration can impact the efficacy and tolerability of treatments such as interferons,35,36 interleukin-2,37 and more recently, anti-PD-1 agents in preclinical models.7 Circadian rhythms influence tumour infiltration by immune cells, such as CD8+ T cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells, which can eliminate cancer cells. This process is enhanced following ICI blockade of PD-1 during the early stages of nocturnal activity in mice.38,39 The efficacy of this process is further amplified by the synchronous circadian increase in PD-1 protein and Pcdc1 mRNA expression in immune cells.7,8 Moreover, PD-L1 expressing immunosuppressive myeloid cells exhibit rhythmic tumour infiltration in mice, increasing the efficacy of anti-PD-L1 agents during early nocturnal hours.38,39 In humans, circulating T-lymphocyte subset levels exhibit nearly twofold increase from approximately 10:00 in the morning (trough) to 02:00 at night (peak).11 These findings suggest that immune cell depletion may occur during the afternoon hours, which may contribute to the observed reduced effectiveness of ICIs when administered later in the day. These chronopharmacodynamic mechanisms likely override the currently unexplored chronopharmacokinetics of ICIs. The half-lives of ICIs, typically ranging from 2 to 3 weeks, support the hypothesis that their chronopharmacokinetics may influence the initial four treatment courses before plasma concentrations reach plateau, typically within five half-lives following the start of treatment, a period consistent with the design of our study.

The CTS also regulates cell cycle and apoptosis, leading to established circadian rhythms in the toxicities and efficacy profiles of approximately 50 anticancer medications in experimental models.40,41 A systematic review of 18 randomised trials of chronomodulated chemotherapy demonstrated consistent benefits of circadian timing for chemotherapy tolerance and efficacy.24,42 These findings align with our initial finding, particularly as chemotherapy was administered immediately after ICI infusion, precluding separate analysis of the timing effects of chemotherapy separately. Experimental and clinical data also suggest improved tolerability of carboplatin when administered in the afternoon to patients with lung cancer.43 However, data on chronopharmacology of agents such as paclitaxel and pemetrexed remain limited or lacking. Nevertheless, our findings showed a similar trend of reduced risk of earlier disease progression or death between patients who received paclitaxel-based and pemetrexed-based chemotherapy in the morning group.

In contrast, taxanes appear to be best tolerated and most effective when administered in the late rest phase in murine models,44,45 with a correlation between the expression of the clock gene Bmal1 and tumour cell susceptibility to paclitaxel.46 Similarly, platinum-based compounds display reduced toxicity and increased efficacy when administered during the active phase in preclinical models (i.e., mice, rats) and patients with cancer,41 although sex may also contribute to the differences.11 Taken together, these findings highlight the need for further mechanistic investigations and the optimisation of chrono-immuno-chemotherapy.

While healthcare logistics often dictate that treatments are administered irrespective of the time of day. Circadian rhythms have long been recognised as key determinants of both the toxicity and efficacy of medications, including anticancer therapies.11,40,41 ICIs have largely improved the survival outcomes for patients with a variety of cancer types over the past two decades.47 However, it is noteworthy that none of the pivotal clinical trials for ICIs approval investigated the possible relevance of ToDA, a factor that has largely been overlooked by the regulatory authorities. Despite variations in ICI administration timing, OS and PFS in our pooled cohort were similar to those reported in key clinical trials that established the current immuno-chemotherapy protocols for advanced or metastatic NSCLC.48,49 This consistency supports the robustness of our overall findings, irrespective of treatment timing, when compared with data from two major randomised clinical trials. Evidence is accumulating to suggest the optimal treatment schedules should account not only for the appropriate dose but also for the optimal time of administration, particularly in therapies targeting immune-cancer cell interactions. Twenty four retrospective studies examining ICI-based immunotherapy have consistently reported improved efficacy outcomes following early ToDA in nearly 3000 patients with various cancers, including lung, kidney, bladder, head-and-neck, oesophageal, stomach, liver and skin cancers.50 However, randomised trials are required to unequivocally validate these findings and to define the best timing recommendations for ICI recommendations (e.g., NCT05549037). These trials will likely include investigations into inter-patient differences in optimal timing, as well as the underlying mechanisms cross the 24-h cycle, facilitating the identification of circadian biomarkers that can inform the personalised scheduling of chrono-immuno-chemotherapy.

In a previous study, Karaboué et al. reported a significantly higher incidence of mild or moderate skin reactions among patients who received the majority of their nivolumab infusions in the morning compared to those who received them in the afternoon.1,16 Conversely, morning administration was found to be more effective and associated with significantly less moderate to severe fatigue. These findings underscore the need for prospective studies to examine the circadian influences of adverse events and efficacy profiles of ICIs, as this remains an area of uncertainty and requires further investigations to optimise treatment strategies.

In conclusion, this large bi-continental study provides compelling real-world evidence that morning administration of immuno-chemotherapy is associated with significantly improved OS, PFS, and response rate in patients with advanced NSCLC. These findings highlight the importance of circadian rhythms in moderating treatment outcomes with immuno-chemotherapy. Further randomised controlled trials are necessary to establish clinical recommendations regarding optimal timing of treatment, with a particular focus on the identification of circadian, sleep and immunological biomarkers to guide the personalisation of immuno-chemotherapy treatment.

Contributors

Z Huang conceived the study, collected Cohort 2 data, contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data, manuscript writing, and development of figures and tables. A Karaboué conceived the study, collected Cohort 1 data, contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data, manuscript writing, and development of figures and tables. L Zeng contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data, and to manuscript review, and revision. A Lecoeuvre designed and performed the statistical analyses, wrote the statistical methods section, contributed to the preparation of figures and tables, and critically read and improved the manuscript. L Zhang, H Qin, F Yang, and L Deng collected data for Cohort 2. XM Li contributed to all collaborative aspects in the study, and critically read and improved the manuscript. G Danino, MS Malin, and M Rigal collected data for Cohort 1. H Liu, X Chen, and Q Xu collected data for Cohort 2, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. L Grimaldi designed the statistical analysis plan of each cohort and both pooled, discussed results, and critically read and improved the manuscript. T Collon contributed to Cohort 1 study design, patient assessments and reviewed the manuscript. J Wang, N Yang, and R Adam discussed results and interpretation, and critically improved the manuscript. B Duchemann conceived the study, was in charge of deidentified data collection for Cohort 1, contributed to all study progress and development, contributed to methods, results, interpretation, and manuscript writing. Y Zhang and F Lévi co-directed this study, including conception, organisation, data collection, auditing, supervision, project management, funding acquisition, writing and editing the manuscript. Z Huang, A Karaboué, A Lecoeuvre, B Duchemann, Y Zhang, and F Lévi verified the underlying data. All authors approved the current manuscript.

Data sharing statement

All the deidentified participant data will be made available 12 months after the publication of this manuscript to the scientists, who will address a request to francis.levi@universite-paris-saclay.fr.

Declaration of interests

All authors report no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Dr. Zhaohui Ruan and Dr. Jiacheng Dai for their valuable assistance in revising the language of this manuscript. Their insights and feedback have significantly improved the clarity and precision of our work.

This work received financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China, (grant numbers: 82222048, 82173338, 82102747, 82303629, and 82160489) and Key Basic Research Project of Qinghai Provincial Department of Science and Technology (2022-ZJ-733).

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2025.105607.

Contributor Information

Yongchang Zhang, Email: zhangyongchang@csu.edu.cn.

Francis Lévi, Email: f.levi@warwick.ac.uk.

Appendix ASupplementary data

References

- 1.Karaboué A., Collon T., Pavese I., et al. Time-dependent efficacy of checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab: results from a pilot study in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2022;14(4) doi: 10.3390/cancers14040896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qian D.C., Kleber T., Brammer B., et al. Effect of immunotherapy time-of-day infusion on overall survival among patients with advanced melanoma in the USA (MEMOIR): a propensity score-matched analysis of a single-centre, longitudinal study. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(12):1777–1786. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00546-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Landre T., Karaboue A., Buchwald Z.S., et al. Effect of immunotherapy-infusion time of day on survival of patients with advanced cancers: a study-level meta-analysis. ESMO Open. 2024;9(2) doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.102220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Catozzi S., Assaad S., Delrieu L., et al. Early morning immune checkpoint blockade and overall survival of patients with metastatic cancer: an In-depth chronotherapeutic study. Eur J Cancer. 2024;199 doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2024.113571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pascale A., Allard M.A., Benamar A., Levi F., Adam R., Rosmorduc O. Prognostic value of the timing of immune checkpoint inhibitors infusion in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42(3_suppl):457. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishizuka Y., Narita Y., Sakakida T., et al. Impact of time-of-day on nivolumab monotherapy infusion in patients with metastatic gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42(3_suppl):268. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsuruta A., Shiiba Y., Matsunaga N., et al. Diurnal expression of PD-1 on tumor-associated macrophages underlies the dosing time-dependent antitumor effects of the PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor BMS-1 in B16/BL6 melanoma-bearing mice. Mol Cancer Res. 2022;20(6):972–982. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-21-0786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang C., Barnoud C., Cenerenti M., et al. Dendritic cells direct circadian anti-tumour immune responses. Nature. 2023;614(7946):136–143. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05605-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohdo S., Koyanagi S., Matsunaga N. Chronopharmacology of immune-related diseases. Allergol Int. 2022;71(4):437–447. doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2022.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cermakian N., Stegeman S.K., Tekade K., Labrecque N. Circadian rhythms in adaptive immunity and vaccination. Semin Immunopathol. 2022;44(2):193–207. doi: 10.1007/s00281-021-00903-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lévi F.A., Okyar A., Hadadi E., Innominato P.F., Ballesta A. Circadian regulation of drug responses: toward sex-specific and personalized chronotherapy. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2024;64:89–114. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-051920-095416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang C., Lutes L.K., Barnoud C., Scheiermann C. The circadian immune system. Sci Immunol. 2022;7(72) doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abm2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yeung C., Kartolo A., Tong J., Hopman W., Baetz T. Association of circadian timing of initial infusions of immune checkpoint inhibitors with survival in advanced melanoma. Immunotherapy. 2023;15(11):819–826. doi: 10.2217/imt-2022-0139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vilalta A., Arasanz H., Rodriguez-Remirez M., et al. 967P the time of anti-PD-1 infusion improves survival outcomes by fasting conditions simulation in non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2021;32:S835. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nomura M., Hosokai T., Tamaoki M., Yokoyama A., Matsumoto S., Muto M. Timing of the infusion of nivolumab for patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus influences its efficacy. Esophagus. 2023;20(4):722–731. doi: 10.1007/s10388-023-01006-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karaboué A., Collon T., Innominato P., Chouahnia K., Adam R., Levi F. Improved survival on morning pembrolizumab with or without chemotherapy during initial treatment for stage IV non-small cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(16_suppl):e21055–e. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rowland M., Tozer T.N. Williams & Wilkins; Baltimore, Maryland, USA: 1995. Clinical Pharmacokinetics: Concepts and Applications. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yagishita S., Yamanaka Y., Kurata T., et al. Multicenter pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of pembrolizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer in patients aged 75 Years and older. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2024;116(4):1042–1051. doi: 10.1002/cpt.3339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohuchi M., Yagishita S., Jo H., et al. Early change in the clearance of pembrolizumab reflects the survival and therapeutic response: a population pharmacokinetic analysis in real-world non-small cell lung cancer patients. Lung cancer. 2022;173:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2022.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hurkmans D.P., Sassen S.D.T., de Joode K., et al. Prospective real-world study on the pharmacokinetics of pembrolizumab in patients with solid tumors. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9(6) doi: 10.1136/jitc-2021-002344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Otten L.S., Piet B., van den Haak D., et al. Prognostic value of nivolumab clearance in non-small cell lung cancer patients for survival early in treatment. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2023;62(12):1749–1754. doi: 10.1007/s40262-023-01316-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gandhi L., Rodriguez-Abreu D., Gadgeel S., et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(22):2078–2092. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paz-Ares L., Luft A., Vicente D., et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy for squamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(21):2040–2051. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1810865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Printezi M.I., Kilgallen A.B., Bond M.J.G., et al. Toxicity and efficacy of chronomodulated chemotherapy: a systematic review. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(3):e129–e143. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00639-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vandenbroucke J.P., von Elm E., Altman D.G., et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Epidemiology. 2007;18(6):805–835. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181577511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reck M., Rodriguez-Abreu D., Robinson A.G., et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1823–1833. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Castro G., Jr., Kudaba I., Wu Y.L., et al. Five-year outcomes with pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy as first-line therapy in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer and programmed death ligand-1 tumor proportion score >/= 1% in the KEYNOTE-042 study. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(11):1986–1991. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.02885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seymour L., Bogaerts J., Perrone A., et al. iRECIST: guidelines for response criteria for use in trials testing immunotherapeutics. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(3):e143–e152. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30074-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uno H., Claggett B., Tian L., et al. Moving beyond the hazard ratio in quantifying the between-group difference in survival analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(22):2380–2385. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lusa L., Ahlin C. Restricted cubic splines for modelling periodic data. PLoS One. 2020;15(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harrell F.E. Springer; New York, New York, USA: 2012. Regression Modeling Strategies. R Package Version 2012: 6.2-0. [Google Scholar]

- 32.R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. R Core Team; Vienna, Austria: 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahlin C., Lusa L. peRiodiCS: periodic restricted and unrestriced cubic splines for regression modelling. 2018. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=peRiodiCS [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Allada R., Bass J. Circadian mechanisms in medicine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(6):550–561. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1802337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ohdo S., Koyanagi S., Suyama H., Higuchi S., Aramaki H. Changing the dosing schedule minimizes the disruptive effects of interferon on clock function. Nat Med. 2001;7(3):356–360. doi: 10.1038/85507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koren S., Whorton E.B., Jr., Fleischmann W.R., Jr. Circadian dependence of interferon antitumor activity in mice. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(23):1927–1932. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.23.1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kemeny M.M., Alava G., Oliver J.M. Improving responses in hepatomas with circadian-patterned hepatic artery infusions of recombinant interleukin-2. J Immunother (1991) 1992;12(4):219–223. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199211000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang C., Zeng Q., Gul Z.M., et al. Circadian tumor infiltration and function of CD8(+) T cells dictate immunotherapy efficacy. Cell. 2024;187(11):2690–2702.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2024.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fortin B.M., Pfeiffer S.M., Insua-Rodriguez J., et al. Circadian control of tumor immunosuppression affects efficacy of immune checkpoint blockade. Nat Immunol. 2024;25(7):1257–1269. doi: 10.1038/s41590-024-01859-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dallmann R., Okyar A., Lévi F. Dosing-time makes the poison: circadian regulation and pharmacotherapy. Trends Mol Med. 2016;22(5):430–445. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lévi F., Okyar A., Dulong S., Innominato P.F., Clairambault J. Circadian timing in cancer treatments. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;50:377–421. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.48.113006.094626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lévi F., Zidani R., Misset J.L. Randomised multicentre trial of chronotherapy with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and folinic acid in metastatic colorectal cancer. International Organization for Cancer Chronotherapy. Lancet. 1997;350(9079):681–686. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)03358-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boughattas N.A., Levi F., Fournier C., et al. Stable circadian mechanisms of toxicity of two platinum analogs (cisplatin and carboplatin) despite repeated dosages in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;255(2):672–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tampellini M., Filipski E., Liu X.H., et al. Docetaxel chronopharmacology in mice. Cancer Res. 1998;58(17):3896–3904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Granda T.G., Filipski E., D'Attino R.M., et al. Experimental chronotherapy of mouse mammary adenocarcinoma MA13/C with docetaxel and doxorubicin as single agents and in combination. Cancer Res. 2001;61(5):1996–2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tang Q., Cheng B., Xie M., et al. Circadian clock gene Bmal1 inhibits tumorigenesis and increases paclitaxel sensitivity in tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2017;77(2):532–544. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Waldman A.D., Fritz J.M., Lenardo M.J. A guide to cancer immunotherapy: from T cell basic science to clinical practice. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20(11):651–668. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0306-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gadgeel S., Rodriguez-Abreu D., Speranza G., et al. Updated analysis from KEYNOTE-189: pembrolizumab or placebo plus pemetrexed and platinum for previously untreated metastatic nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(14):1505–1517. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.03136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paz-Ares L., Vicente D., Tafreshi A., et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in patients with metastatic squamous NSCLC: protocol-specified final analysis of KEYNOTE-407. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15(10):1657–1669. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karaboue A. Paris Saclay University; France: 2024. Role of the Circadian Timing System in the Control of Survival of Patients Receiving Immunotherapy for Cancer. Analysis of Relevant Mechanisms. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.