Abstract

Orally disintegrating tablets (ODTs) dissolve rapidly in contact with saliva and have been reported to facilitate oral administration of medications in swallowing difficulties. However, their clinical benefits remain unclear because no previous studies have examined whether ODTs facilitate medication adherence and clinical outcomes in patients with post-stroke dysphagia. This study evaluated the association between ODT prescriptions and clinical benefits using high-dimensional propensity score (hd-PS) matching to adjust for confounding factors. Using a large Japanese commercial medical and dental claims database, we identified patients aged ≥ 65 years with post-stroke dysphagia between April 2014 and March 2021. To compare 1-year outcomes of medication adherence, cardiovascular events, and aspiration pneumonia between patients taking ODTs and non-ODTs, we performed hd-PS matching. We identified 11,813 patients without ODTs and 3178 patients with ODTs. After hd-PS matching, 2246 pairs were generated. Medication adherence for 1 year, based on the proportion of days covered, was not significantly different between the non-ODT and ODT groups before (0.887 vs. 0.900, P = 0.999) and after hd-PS matching (0.889 vs. 0.902, P = 0.977). The proportion of cardiovascular events (0.898 vs. 0.893, P = 0.591) and aspiration pneumonia (0.380 vs. 0.372, P = 0.558) were also not significantly different between the groups. This study found no significant differences in medication adherence, cardiovascular diseases, or aspiration pneumonia between the non-ODT and ODT groups in patients with post-stroke dysphagia. Both groups achieved a proportion of days covered exceeding 80%. Clinicians may consider prescribing ODTs or non-ODTs based on patient preferences rather than solely on post-stroke conditions.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00455-024-10737-8.

Keywords: Deglutition disorders, Medication adherence, Propensity score, Stroke

Introduction

Orally disintegrating tablets (ODTs) disintegrate or dissolve rapidly in the oral cavity upon contact with saliva [1]. Patients do not need to chew or drink additional water when they take ODTs, and ODTs facilitate oral administration for those with difficulty swallowing [2–5]. Because ODTs can be easily taken by patients with difficulty swallowing, they are expected to improve medication adherence [1]. A previous review reported that at least 37–45% of post-stroke patients had dysphagia due to malfunction of the swallowing mechanism [6]. Therefore, ODTs may be a promising treatment option for patients with post-stroke dysphagia.

In a previous study, patients with dysphagia caused by stroke or cancer taking ODTs showed better swallowing performance than those taking non-ODTs, as evaluated by endoscopy and electromyography, compared to those taking non-ODTs [5]. Another study reported that 28% of diabetic patients improved their medication adherence after switching from non-ODTs to ODTs [7].

However, the benefits of ODTs in patients with post-stroke dysphagia remain unclear. A previous study reported no differences in residuals in the pharynx and larynx or in aspiration between ODTs and non-ODTs [5]. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have reported the clinical benefits of ODTs in patients with post-stroke dysphagia. Therefore, the present study aimed to evaluate the effect of ODTs on medication adherence and clinical outcomes in post-stroke patients with dysphagia compared with non-ODTs.

Materials and Methods

Data Source

This study utilized the DeSC database (DeSC Healthcare, Inc.), a large commercial medical and dental claims database in Japan. Studies using this database can be found elsewhere [8, 9]. This database contains health insurance claims data from multiple types of health insurers: (i) National Health Insurance for individual proprietors and unemployees (Kokuho), (ii) health insurance for employees of large companies (Kempo), and (iii) the Advanced Elderly Medical Service System for those aged 75 years and over (Koki Koreisha Iryo Seido). Thus, the DeSC database included young, middle-aged, and elderly individuals. Medical and dental claims data for outpatients and inpatients were anonymized at the individual level. The database includes the following information: (i) unique identifier, (ii) age and sex, (iii) diagnoses based on the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes, (iv) procedures, (v) drugs dispensed based on the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System, and (vi) dates of enrollment and disenrollment in insurance. The DeSC database contains information on approximately 12,000,000 individuals, and its age distribution of the DeSC database is comparable to the Japanese population estimates [9].

Study Design and Patient Selection

This retrospective cohort study used the data collected between April 2014 and March 2021. A new prevalent user design was used [10]. We included patients who (i) were diagnosed with stroke (ICD-10 I60–I63), (ii) underwent swallowing rehabilitation within a year from the diagnosis of stroke, (iii) were newly prescribed the target drugs listed in Online Resource 1 (initial pharmacotherapy for hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or hyperlipidemia), and (iv) had at least 1 year of any records in the DeSC database before cohort entry. We defined the patients’ age on the day of new use of the target drugs. We excluded patients who (i) were prescribed the target drugs within the previous year, (ii) were newly prescribed the target ODTs and non-ODTs at the same time, (iii) were under 65 years of age since those aged ≥ 65 years were reportedly more likely to experience dysphagia than the younger age groups [11], (iv) were prescribed the target drugs less than twice in the study period, and (v) had a gastrostomy before cohort entry. The patients were followed-up from the initiation of the target drugs to assess the outcomes.

Exposure of Interest

We compared patients who received targeted ODTs (ODT group) with those who received active comparators (non-ODT group). Target ODTs were defined as medications used for hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia (Online Resource 1). This is because the Japanese Guidelines for the Management of Stroke 2021 recommend medication to prevent recurrent strokes (grades A–C) [12]. Active comparators (non-ODTs) included all drugs with the same target disease as the ODTs.

Variables

We included the following variables in the model: age (65–74, ≥ 75 years), sex, diagnoses, procedures, and drug use history during the pre-prescription period. The variables included in the analyses were based on previous studies investigating aspiration, dysphagia, and salivary disorders [6, 13, 14]. Further details of these variables are provided in Online Resource 2. In this study, the pre-prescription period was defined as the period within 365 days of the initial use of ODTs or active comparators.

Outcome Measurements

The primary outcome was the target drug proportion of days covered (PDC) for 1 year as the patient’s medication adherence [15]. We defined the start date as the first fill date for each target drug and the end date as the date of the last fill. The evaluation period for PDC was set at 1 year, which is the minimum recommended evaluation period according to the guidelines of the National Association of Specialty Pharmacy Clinical Outcomes Committee Adherence Workgroup and the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists section of specialty pharmacy practitioner outcomes and value section advisory group [15]. If the follow-up period was less than 1 year, the PDC for the observed period was assumed to continue for 1 year. We defined the medication adherence threshold as a PDC of 80%, following a previous study of medication adherence [16]. The secondary outcomes were hospital admission for aspiration pneumonia (ICD-10: J69), cardiovascular events (i.e., heart failure (ICD-10: I50, I11), atrial fibrillation (ICD-10: I48), myocardial infarction (ICD-10: I21), angina pectoris (ICD-10: I20), stroke (ICD-10: I60–63), and composite event of cardiovascular diseases [17] within 1 year as a benefit of medication adherence.

Statistical Analysis

Hd-PS Estimation

In this study, we used a large claims database in Japan to obtain a large study sample. We conducted a high-dimensional propensity score (hd-PS) matching analysis to balance patient backgrounds and account for confounding factors. Hd-PS analysis was proposed for studies using administrative claims databases to improve the ability to control confounding factors in comparative effectiveness [18]. We performed hd-PS matching between ODT and non-ODT groups. The detailed methods for hd-PS estimation have been described previously [19]. Briefly, the following five processes were conducted: (i) definition of different data dimensions; (ii) identification of empirical candidate covariates in each data dimension during the pre-prescription period; (iii) assessment of the frequencies of candidate covariates; (iv) ranking of candidate covariates of all dimensions by their potential as confounding factors based on Bross’s formula [20], and (v) selection of the top n potential covariates for propensity score modeling.

We structured the following ten dimensions: medical outpatient diagnoses, medical inpatient diagnoses, dental outpatient diagnoses, dental inpatient diagnoses, medical outpatient procedures, medical inpatient procedures, dental outpatient procedures, dental inpatient procedures, and outpatient and inpatient drug use. We included the 500 highest potential covariates and variables described in Online Resource 2 in the logistic regression model for receiving the target ODTs to estimate hd-PS.

Propensity Score Matching

We performed 1:1 nearest-neighbor matching with the caliper width set at 20% of the standard deviation of the propensity score. The balancing properties of the matching covariates were examined using absolute standardized differences between the groups. An absolute standardized difference of > 10% was considered to indicate an imbalance. The chi-squared test was used for categorical variables and Student’s t-test was used for continuous variables to compare the outcomes between the ODT and non-ODT groups.

Subgroup Analysis

We conducted subgroup analyses stratified by treatment with ODTs (hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia) to compare medication adherence between the ODT and non-ODT groups. Subgroup analyses were also performed, stratified by the presence of polypharmacy (non-polypharmacy, polypharmacy, and hyperpolypharmacy). All prescriptions were identified to determine the number of drugs administered by each patient. Patients were considered to have taken prescribed medications within 60 days prior to cohort entry [10]. We calculated the number of drug classes taken by each patient from the 86 classes (Online Resource 3). Based on the number of prescribed drugs, we classified the patients into three groups [21]: no polypharmacy, polypharmacy (five to nine classes), and hyper-polypharmacy (ten or more classes).

The threshold for significance was set at P = 0.05. The hd-PS estimation was performed using R version 3. 6. 1. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The remaining statistical analyses were performed using Stata SE (version 17.0; StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

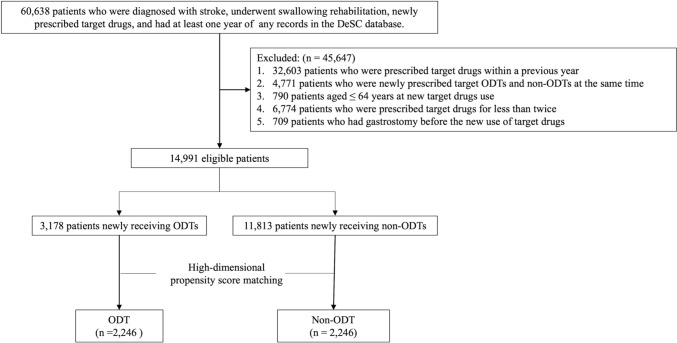

After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 14,991 patients were identified between April 2014 and March 2020 (Fig. 1). Of those, 10,376 (69%) received antihypertensive drugs, 1844 (12%) received antidiabetic drugs, and 2771 (18%) received antidyslipidemic drugs. Propensity score matching created 2246 pairs.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the selection of study participants. ODTs, orally disintegrating tablets

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics before and after propensity score matching. Before matching, the non-ODT group had a higher proportion of patients with diabetes, myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, asthma, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and renal failure but a lower proportion of patients with dementia, hypertension, and patients who underwent nasal feeding. Patient characteristics were balanced between the groups after propensity score matching.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics before and after 1:1 high-dimensional propensity score matching

| Unmatched groups | ASD | High-dimensional propensity score-matched groups | ASD | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-ODT | ODT | Non-ODT | ODT | |||||||

| n = 11,813 | (%) | n = 3178 | (%) | n = 2246 | (%) | n = 2246 | (%) | |||

| Age | ||||||||||

| 65–74 | 1546 | (13) | 368 | (12) | 4.6 | 279 | (12) | 271 | (12) | 1.1 |

| ≥ 75 | 10,267 | (87) | 2810 | (88) | 4.6 | 1967 | (88) | 1975 | (88) | 1.1 |

| Male | 6406 | (54) | 1564 | (49) | 10.0 | 1112 | (50) | 1137 | (51) | 2.2 |

| Human immunodeficiency virus | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | (0) | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Sarcoidosis | 26 | (0) | 1 | 0 | 6.3 | 1 | (0) | 1 | (0) | 0.0 |

| Diabetes | 6969 | (59) | 1333 | (42) | 34.7 | 973 | (43) | 986 | (44) | 1.2 |

| Hypoglycemia | 400 | (3) | 60 | (2) | 9.3 | 45 | (2) | 53 | (2) | 2.5 |

| Amyloidosis | 73 | (1) | 16 | (1) | 1.4 | 13 | (1) | 11 | (0) | 1.2 |

| Dementia | 3876 | (33) | 1210 | (38) | 11.1 | 819 | (36) | 819 | (36) | 0.0 |

| Parkinson’s disease or parkinsonian disorder | 1203 | (10) | 325 | (10) | 0.0 | 215 | (10) | 226 | (10) | 1.6 |

| Hypertension | 10,830 | (92) | 3021 | (95) | 13.7 | 2122 | (94) | 2112 | (94) | 1.9 |

| Myocardial infarction | 946 | (8) | 131 | (4) | 16.4 | 104 | (5) | 103 | (5) | 0.2 |

| Angina pectoris | 4938 | (42) | 910 | (29) | 27.9 | 679 | (30) | 691 | (31) | 1.2 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 4211 | (36) | 679 | (21) | 31.9 | 511 | (23) | 507 | (23) | 0.4 |

| Heart failure | 8423 | (71) | 1861 | (59) | 26.9 | 1328 | (59) | 1341 | (60) | 1.2 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 11,813 | (100) | 3178 | (100) | 0.0 | 2246 | (100) | 2246 | (100) | 0.0 |

| Aspiration pneumonia | 4580 | (39) | 1358 | (43) | 7.9 | 1043 | (46) | 1086 | (48) | 3.8 |

| Other pneumonia | 5880 | (50) | 1558 | (49) | 1.6 | 912 | (41) | 903 | (40) | 0.8 |

| COPD | 810 | (7) | 206 | (7) | 1.6 | 136 | (6) | 133 | (6) | 0.6 |

| Asthma | 2656 | (23) | 579 | (18) | 10.7 | 425 | (19) | 428 | (19) | 0.4 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 8779 | (74) | 2142 | (67) | 15.2 | 1527 | (68) | 1524 | (68) | 0.3 |

| Achalasia | 197 | (2) | 48 | (2) | 1.6 | 42 | (2) | 35 | (2) | 2.4 |

| Disorder after digestive system treatment | 164 | (1) | 48 | (2) | 0.8 | 30 | (1) | 33 | (1) | 1.1 |

| Scleroderma | 46 | (0) | 8 | (0) | 1.7 | 3 | (0) | 5 | (0) | 0.0 |

| Sjögren’s syndrome | 410 | (4) | 91 | (3) | 3.4 | 60 | (3) | 68 | (3) | 2.0 |

| Renal failure | 3103 | (26) | 618 | (19) | 16.5 | 505 | (22) | 469 | (21) | 3.9 |

| Other specified symptoms and signs involving the digestive system and abdomen | 2330 | (20) | 748 | (24) | 9.2 | 484 | (22) | 481 | (21) | 1.3 |

| Antiepileptic drugs | 3325 | (28) | 925 | (29) | 2.2 | 608 | (27) | 619 | (28) | 1.1 |

| Parkinson’s disease drugs | 174 | (2) | 45 | (1) | 0.8 | 29 | (1) | 30 | (1) | 0.4 |

| Hypnotic | 7857 | (67) | 1968 | (62) | 9.6 | 1417 | (63) | 1396 | (62) | 2.1 |

| Rehabilitation for cerebrovascular diseases | 7350 | (62) | 2101 | (66) | 8.1 | 1484 | (66) | 1462 | (65) | 2.1 |

| Nasal feeding | 2827 | (24) | 1005 | (32) | 17.3 | 616 | (27) | 601 | (27) | 1.5 |

| Tracheotomy | 160 | (1) | 51 | (2) | 1.6 | 32 | (1) | 33 | (1) | 4.3 |

| Oral care for preoperative periods | 439 | (4) | 119 | (4) | 0.0 | 82 | (4) | 75 | (3) | 1.7 |

ASD absolute standardized difference, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ODT orally disintegrating tablet

The primary outcomes before and after propensity score matching are shown in Table 2. The PDC exceeded 80% for the two groups before and after matching. There was no significant difference between the non-ODT and ODT group before (0.887 vs. 0.900, P = 0.999) or after (0.889 vs. 0.902, P = 0.977) propensity score.

Table 2.

The proportion of days covered for one year, and the proportion of admission for cardiovascular events and aspiration pneumonia between non-ODT and ODT groups before and after high-dimensional propensity score-matching

| Unmatched groups | P value | High-dimensional propensity score-matched groups | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-ODT | ODT | Non-ODT | ODT | |||

| Primary outcome | ||||||

| PDC for 1 year | 0.887 | 0.900 | 0.999 | 0.889 | 0.902 | 0.977 |

| Secondary outcome | ||||||

| Heart failure | 0.529 | 0.391 | < 0.001 | 0.409 | 0.403 | 0.715 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 0.312 | 0.180 | < 0.001 | 0.195 | 0.193 | 0.850 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0.045 | 0.025 | < 0.001 | 0.023 | 0.028 | 0.299 |

| Angina pectoris | 0.261 | 0.171 | < 0.001 | 0.183 | 0.183 | 0.969 |

| Stroke | 0.771 | 0.812 | < 0.001 | 0.810 | 0.798 | 0.310 |

| Composite event of cardiovascular diseases | 0.904 | 0.903 | 0.778 | 0.898 | 0.893 | 0.591 |

| Aspiration pneumonia | 0.363 | 0.400 | < 0.001 | 0.380 | 0.372 | 0.558 |

Composite event of cardiovascular diseases consists of heart failure, atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, and stroke

ODT orally disintegrating tablet, PDC proportion of days covered

The secondary outcomes are presented in Table 2. Before propensity score matching, the non-ODT group had a significantly higher proportion of heart failure, atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction, and angina pectoris than the ODT group, and a significantly lower proportion of stroke and aspiration pneumonia than the ODT group. However, no significant differences were observed between the non-ODT and ODT groups after propensity score matching.

Online Resource 4 shows the results of the subgroup analyses. None of the subgroups showed significant differences in primary outcomes between the two groups. Regarding secondary outcomes, none of the subgroups showed significant differences between the two groups, except for myocardial infarction in the antidyslipidemic drug subgroup.

Discussion/Conclusion

We compared medication adherence in patients with dysphagia who received non-ODTs and ODTs, using a large commercial medical and dental claims database. There was no significant difference between the non-ODT and ODT groups in terms of the PDC. In addition, there was no significant difference in the occurrence of cardiovascular events and aspiration pneumonia within 1 year between the two groups.

Previous studies have suggested that because patients with dysphagia can take ODTs more easily than non-ODTs, their PDC improves [1, 5, 7]. However, our results did not show a significant difference between the two groups in terms of the PDC. This may be because the Japanese patients adhered well to their medications. A previous study showed higher medication adherence among Japanese patients with ulcerative colitis than among their European counterparts [22]. This could be attributed to the tendency of Japanese patients to follow instructions diligently [23]. In addition, one-third of the patients with hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia in the United States were reported to be < 80% in terms of PDC [24]. However, this differs from the higher rates observed in this study. The current study showed a PDC comparable to that in previous Japanese studies on medication adherence in hypertension [25], diabetes [26], and dyslipidemia [27]. Specifically, medication adherence was good, with the majority of patients achieving a PDC > 80%. Although there was an overall trend toward lower medication adherence for polypharmacy, there was no significant difference in medication adherence between the ODT and non-ODT groups. There were also no significant differences in medication adherence for drug-targeted diseases. Given that ODTs are typically larger in size than non-ODTs and cause taste-related problems [28], clinicians may prescribe ODTs or non-ODTs based on patient preferences rather than only on post-stroke conditions.

No significant differences were observed in the incidence of aspiration pneumonia. The results of the current study are similar to those of a previous study, which showed no difference in the proportion of aspiration between ODTs and non-ODTs [5, 29]. Therefore, clinicians may not consider the increased risk of aspiration when prescribing non-ODTs.

This study has several limitations. First, this was a retrospective study that used a large commercial medical and dental claims database. Therefore, information and selection biases may have affected the results. To reduce this bias, we performed hd-PS matching. However, unmeasured confounding factors may have affected these results. Second, medication adherence was assessed using a claims database. However, it is unclear whether this accurately reflects actual medication adherence, as we were unable to observe when the patients took their medications. Nevertheless, this study followed the methods recommended by the National Association of Specialty Pharmacy Clinical Outcomes Committee Adherence Workgroup and the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists Section of Specialty Pharmacy Practitioners Outcomes and Value Section Advisory Group [15], which ensured the validity of our results.

In conclusion, there was no difference in medication adherence between the ODT and the non-ODT groups of patients with post-stroke dysphagia, and both groups had a good PDC exceeding 80%. Clinicians may consider prescribing ODTs or non-ODTs based on patient preferences rather than solely on post-stroke conditions. Therefore, further studies on other etiologies of dysphagia, such as sarcopenia, are warranted.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan (23AA2003).

Author Contributions

Study concept and design; So Sato, Yusuke Sasabuchi, Hideo Yasunaga. Acquisition of data: Hideo Yasunaga. Analysis and interpretation of data: So Sato, Yusuke Sasabuchi, Akira Okada. Drafting of the manuscript: So Sato. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: So Sato, Yusuke Sasabuchi, Akira Okada, Hideo Yasunaga. All the authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by The University of Tokyo. This work was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan (23AA2003).

Data Availability

The datasets analyzed in the current study are commercially available, DeSC Healthcare, Inc. providing the database.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Graduate School of Medicine at the University of Tokyo [approval number: 2021010NI (April 23, 2021)]. The requirement for written consent was waived due to data anonymity.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Quinn HL, Hughes CM, Donnelly RF. Novel methods of drug administration for the treatment and care of older patients. Int J Pharm. 2016;512(2):366–73. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slavkova M, Breitkreutz J. Orodispersible drug formulations for children and elderly. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2015;30(75):2–9. 10.1016/j.ejps.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wade AG, Crawford GM, Young D. A survey of patient preferences for a placebo orodispersible tablet. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:201–6. 10.2147/ppa.s28283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nausieda PA, Pfeiffer RF, Tagliati M, Kastenholz KV, DeRoche C, Slevin JT. A multicenter, open-label, sequential study comparing preferences for carbidopa-levodopa orally disintegrating tablets and conventional tablets in subjects with Parkinson’s disease. Clin Ther. 2005;27(1):58–63. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carnaby-Mann G, Crary M. Pill swallowing by adults with dysphagia. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;131(11):970–5. 10.1001/archotol.131.11.970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones CA, Colletti CM, Ding MC. Post-stroke Dysphagia: recent insights and unanswered questions. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2020;20(12):61. 10.1007/s11910-020-01081-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koh N, Sakamoto S, Chino F. Improvement in medication compliance and glycemic control with voglibose oral disintegrating tablet. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2008;216(3):249–57. 10.1620/tjem.216.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hashimoto Y, Okada A, Matsui H, Yasunaga H, Aihara M, Obata R. Recent trends in anti-vascular endothelial growth factor intravitreal injections: a large claims database study in Japan. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2023;67(1):109–18. 10.1007/s10384-022-00969-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okada A, Yasunaga H. Prevalence of noncommunicable diseases in Japan using a newly developed administrative claims database covering young, middle-aged, and elderly people. JMA J. 2022;5(2):190–8. 10.31662/jmaj.2021-0189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Filion KB, Lix LM, Yu OH, Dell’Aniello S, Douros A, Shah BR, St-Jean A, Fisher A, Tremblay E, Bugden SC, Alessi-Severini S, Ronksley PE, Hu N, Dormuth CR, Ernst P, Suissa S. Canadian network for observational drug effect studies (CNODES) investigators. Sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors and risk of major adverse cardiovascular events: multi-database retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020;370:3342. 10.1136/bmj.m3342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baijens LW, Clavé P, Cras P, Ekberg O, Forster A, Kolb GF, Leners JC, Masiero S, Mateos-Nozal J, Ortega O, Smithard DG, Speyer R, Walshe M. European Society for Swallowing Disorders–European Union Geriatric Medicine Society white paper: oropharyngeal dysphagia as a geriatric syndrome. Clin Interv Aging. 2016;11:1403–28. 10.2147/CIA.S107750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stroke Guideline Committee, Japan Stroke Association, Japanese Guidelines for the Management of Stroke 2021. pp. 6–13.

- 13.Marik PE. Aspiration pneumonitis and aspiration pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(9):665–71. 10.1056/nejm200103013440908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishimaru M, Ono S, Matsui H, Yasunaga H. Association between perioperative oral care and postoperative pneumonia after cancer resection: conventional versus high-dimensional propensity score matching analysis. Clin Oral Investig. 2019;23(9):3581–8. 10.1007/s00784-018-2783-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loucks J, Zuckerman AD, Berni A, Saulles A, Thomas G, Alonzo A. Proportion of days covered as a measure of medication adherence. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2022;79(6):492–6. 10.1093/ajhp/zxab392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rasmussen JN, Chong A, Alter DA. Relationship between adherence to evidence-based pharmacotherapy and long-term mortality after acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2007;297(2):177–86. 10.1001/jama.297.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaneko H, Yano Y, Itoh H, Morita K, Kiriyama H, Kamon T, Fujiu K, Michihata N, Jo T, Takeda N, Morita H, Node K, Carey RM, Lima JAC, Oparil S, Yasunaga H, Komuro I. Association of blood pressure classification using the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association blood pressure guideline with risk of heart failure and atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2021;143(23):2244–53. 10.1161/circulationaha.120.052624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Franklin JM, Eddings W, Glynn RJ, Schneeweiss S. Regularized regression versus the high-dimensional propensity score for confounding adjustment in secondary database analyses. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;182(7):651–9. 10.1093/aje/kwv108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schneeweiss S, Rassen JA, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Mogun H, Brookhart MA. High-dimensional propensity score adjustment in studies of treatment effects using health care claims data. Epidemiology. 2009;20(4):512–22. 10.1097/ede.0b013e3181a663cc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bross ID. Spurious effects from an extraneous variable. J Chronic Dis. 1966;19(6):637–47. 10.1016/0021-9681(66)90062-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hosoi T, Yamana H, Tamiya H, Matsui H, Fushimi K, Akishita M, Yasunaga H, Ogawa S. Association between comprehensive geriatric assessment and polypharmacy at discharge in patients with ischaemic stroke: a nationwide, retrospective, cohort study. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;25(50): 101528. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawakami A, Tanaka M, Choong LM, Kunisaki R, Maeda S, Bjarnason I, Hayee B. Self-reported medication adherence among patients with ulcerative colitis in Japan and the United Kingdom: a secondary analysis for cross-cultural comparison. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2022;16:671–8. 10.2147/PPA.S346309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Asai A, Kishino M, Tsuguya F, Sakai M, Yokota M, Nakata K, Sasakabe S, Sawada K, Kaiji F. A report from Japan: choices of Japanese patients in the face of disagreement. Bioethics. 1998;12:162–72. 10.1111/1467-8519.00102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leslie RS, Tirado B, Patel BV, Rein PJ. Evaluation of an integrated adherence program aimed to increase Medicare Part D star rating measures. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2014;20:1193–203. 10.18553/jmcp.2014.20.12.1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishimura S, Kumamaru H, Shoji S, Sawano M, Kohsaka S, Miyata H. Adherence to antihypertensive medication and its predictors among non-elderly adults in Japan. Hypertens Res. 2020;43(7):705–14. 10.1038/s41440-020-0440-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nishimura R, Kato H, Kisanuki K, Oh A, Hiroi S, Onishi Y, Guelfucci F, Shimasaki Y. Treatment patterns, persistence and adherence rates in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Japan: a claims-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(3): e025806. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Umeda T, Hayashi A, Fujimoto G, Piao Y, Matsui N, Tokita S. Medication adherence/persistence and demographics of Japanese dyslipidemia patients on statin-ezetimibe as a separate pill combination lipid-lowering therapy—an observational pharmacy claims database study. Circ J. 2019;83(8):1689–97. 10.1253/circj.CJ-18-1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haraguchi T, Miyazaki A, Yoshida M, Uchida T. Bitterness evaluation of intact and crushed Vesicare orally disintegrating tablets using taste sensors. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2013;65(7):980–7. 10.1111/jphp.12078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Umaki Y, Nozaki S, Sugishita S, Shiimoto K, Hashiguchi S, Inui T, Adachi K. Is an oral disintegrating tablets a formulation that is easy to ingest for patients experiencing difficulty with eating and swallowing? Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2009;49:90–5. 10.5692/clinicalneurol.49.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed in the current study are commercially available, DeSC Healthcare, Inc. providing the database.