Abstract

The application of agrochemicals such as organophosphate pesticides (OPPs) has several benefits in agriculture but also poses great risks to the environment and human well-being. Thus, this study was conducted to determine the concentrations, distribution pattern, relationships, potential risks and sources of OPPs in agricultural soils and vegetables from Delta Central District (DCD) of Nigeria to provide useful information for pollution history, establishment of pollution control measures and risk management. Fourteen OPPs were determined in the soil and vegetables using a gas chromatograph-mass selective detector (GC-MSD). The ∑14 OPPs concentrations varied from 5.29 to 419 ng g−1 for soil and 0.69 to 130 ng g−1 for vegetables. On average, pirimiphos methyl (23.8 ng g−1) and diazinone (4.74 ng g−1) were the dominant OPPs in soils and vegetables respectively. The cumulative ecological risk assessed using the toxicity-exposure-ratio (TER) and risk quotient (RQ) approaches revealed that there was a high risk of OPPs to soil organisms. The increasing order of OPPs toxicity to the soil organisms was chlorpyriphos < fenitrothion < diazinone < pirimiphos methyl while the cumulative human health risk suggested there was adverse non-carcinogenic risk for children but not for adults exposed to OPPs in these agricultural soils and vegetables.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-83518-w.

Keywords: OPPs, Toxicity exposure ratio, Risk quotient, Hazard index, GC-MSD

Subject terms: Environmental sciences, Chemistry

Introduction

Pest control is essential to achieving food security since pests heavily contribute to crop losses. Pesticides are a family of chemicals that are widely employed to prevent and eliminate these pests1,2. A wide variety of undesirable pests, such as insects, rodents, fungi, and undesired plants, are encountered during agricultural activities. Globally, more than two million tonnes of pesticides—including herbicides (47.5%), fungicides (17.5%), insecticides (29.5%), and others (5.5%)—are used to control weeds, pests, and insects3–5. Based on their chemical makeup, pesticides are typically divided into four groups: organochlorine, organophosphate, carbamates, and pyrethroids6. Organophosphate pesticides (OPPs) are thiophosphate or esters derived from phosphoric acid which were first made available for purchase in the 1930s7. Organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) are gradually being replaced by OPPs because they are environmentally degradable, have a milder effect, are safer, and are less persistent8,9. OPPs are the most commonly used pesticides, making up for about 40% of the global pesticide market, even though demand for them is still rising due to their effectiveness, reliability, lack of pest resistance, broad range of applications, capacity for multi-pest control, low cost, and other recent economic advantages10,11.

OPPs have significant advantages, particularly in agriculture and public health, but their improper use has detrimental effects on the environment and human health12. OPP’s impact on specific beneficial soil species endangers the sustainability of the environment12,13. OPP exposure in humans may have both acute and chronic consequences. Chronic effects include impacts on reproduction, neurological damage, genetic diseases, endocrine disruption, and others. Acute effects include headaches, dizziness, panic attacks, poor vision, nausea, and other symptoms14,15. OPPs have a variety of toxicity and action mechanisms for both target and non-target organisms. The most prevalent mechanism is neurotoxic, and it involves phosphorylating the amino acid serine at the enzyme’s carboxyl-terminal residue in the active site to inhibit the activity of the acetylcholinesterase (AChE) enzyme2,16. The overstimulation of muscarinic and nicotinic receptors as a result of this inhibition results in an inability to hydrolyze the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh), raising its levels at the nerve synapse and potentially causing both neuronal and non-neuronal toxic effects as well as the death of exposed organisms16,17. The principal source of OPP contamination in the ecosystem is agricultural operations18. OPPs have been used incessantly and excessively, polluting environmental matrices and media as a result since studies have shown that more than 95% of applied pesticides reach other non-targeted organisms19–21. Agricultural soils received OPPs from direct application, polluted irrigation water and atmospheric deposition22. OPPs can change their chemical structure once released into the soil through biotic and abiotic processes, producing comparatively less toxic or more harmful chemicals23. OPPs in soil can travel through runoff, leaching and volatilization to surface water, groundwater and air, respectively; and undergo bioaccumulation and biomagnification along the food web resulting in negative effects on biota and humans24. Consequently, soil is an important sink and a secondary source of OPPs. However, a variety of factors, including biological, physical, and chemical factors, affect the mobility of OPPs in soil25,26.

OPPs in soil may be present in vegetables. Vegetables are the second food consumed mostly in West Africa aside from cereals and presently, there is a rise in the consumption of vegetables globally27–30. Vegetables are eaten cooked or raw. They supply supplementary minerals, vitamins and other nutrients31,32. It is generally believed that eating vegetable foods can defer senescence, decrease the risk of obesity and heart diseases and avert some kinds of cancers10,33. It is projected that adequate consumption of vegetables entails intake of not less than 400 g per day. However, eating vegetables contaminated with pesticides such as OPPs may be harmful for consumers, since farmers applied pesticides to manage pests during vegetable cultivation as well as to enhance yield. Thus there is a need to assess the levels and potential risks of OPPs in soils.

Several studies have evaluated the occurrence and risk assessment of OPPs in agricultural soils and vegetables around the world9,10,34–45. For instance, Yao et al.45 reported the occurrence, distribution, and risk of organophosphate pesticides and pyrethroids in agricultural soils from the Pearl River Delta (PRD), South China while Pan et al.9 reported the concentrations, distribution and risks of organophosphate pesticide in agricultural soils from the Yangtze River Delta of China. Moreover, Ssemugabo et al.44 reported the concentrations of OPPs residues in fruits and vegetables from farm-to-fork in the Kampala Metropolitan Area, Uganda while Hu et al.42 reported OPPs residues in vegetables in four regions of Jilin Province. However, these studies either focused only on soil or only on vegetables. None of these studies focused on the OPPs in both soil and vegetables from a given farmland in the same location or environment. Detailed investigation of the levels, compositional patterns, sources and risks of OPPs in agricultural soil and cultivated vegetables from a given sampling location is lacking around the globe in general and Nigeria in particular to the best of our knowledge. Thus, the present study aimed to determine the concentrations, distribution pattern, relationships, sources and potential risks of OPPs in agrarian soil and vegetables from the Delta Central District of Nigeria. This information is useful for pollution history, local environmental quality, risk management, establishment of pollution control measures and guidance for remediation/cleanup and environmental forensic studies.

Materials and methods

Description of area

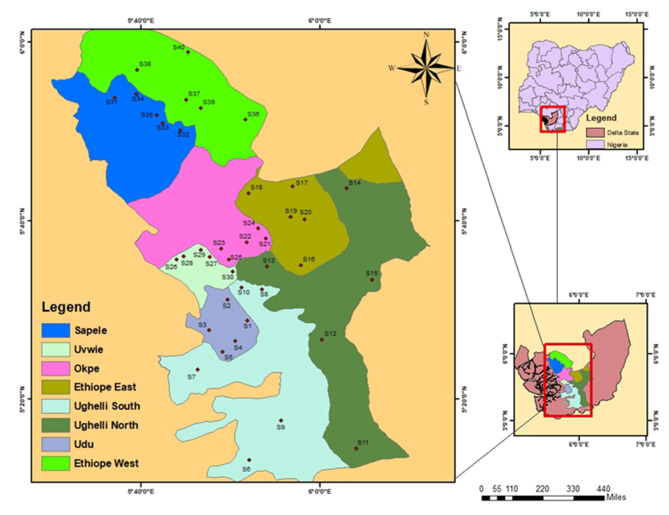

The study area lies between latitude 5o15’0’’ N and 5o30’0’’ N and longitude 5o45’0’’ E and 6o15’0’’ E (Fig. 1). The study area is characterized by intense agricultural operations using pesticides. Yam, cassava, potatoes and vegetables are the major food crops cultivated in the area. The area witnesses modest rains and is humid for most of the year with an equatorial climate.

Fig. 1.

Map of the study area. The map was created using the software ArcGIS version 10.8.2 https://desktop.arcgis.com/en/arcmap.

There are two seasons which are the dry and rainy seasons. The dry season starts and ends in November and March respectively. The rainy season starts in April and terminates in October; however, there is an ‘August break’ in between. Nevertheless, it rains at intervals during the dry season. The rainfall varies from 2,700 to 3,000 mm per annum24,46 while the mean daily temperature varies from 25 to 33oC.

Reagents

High purity (99.9%) analytical standards of fourteen (14) OPPs, including diazinone, isazophos, chlorpyriphos-methyl, pirimiphos methyl, fenitrithion, pirimiphos ethyl, quinalphos, chlorpyrifos, triphenyl phosphate, EPN, phosalone, pyrazophos, azinphos ethyl and pyraclofos were purchased from Accu Standard, New Haven Connecticut, T, USA. Deuterated labelled chrysene (chry) was utilized as a surrogate standard and was obtained from GFS Chemicals, Columbus, Ohio, USA. Acetone, petroleum ether, and hexane (99.9% pure) were purchased from Labtech Chemicals, Sorisole, Italy. Anhydrous sodium sulfate and Florisil were purchased from Merck, Darmstadt, Germany and activated before use. The physicochemical properties of the studied OPPs are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Physicochemical properties of investigated organophosphate pesticides.

| OPPs | Molecular Formula |

Molecular Weight |

Koc (cm3/g) | Solubility (20–25 oC) (mg/L) | Vapour Pressure (20–25 oC) (Pa) | Log Kow | GUS Leaching Potential Index |

Half-life (T1/2) (Days) |

Density (g/cm3) | Boiling Point (oC) | Melting Point (oC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diazinone | C12H21N2O3PS | 304.3 | 1000 | 60 | 1.20 × 10−2 | 3.3 | 1.51 | 40 | 1.12 | 83–84 | 306 |

| Isazophos | C9H17ClN3O3PS | 313.74 | 100 | 69 | 7.45 × 10−3 | 3.82 | 2.77 | 34 | 1.4 | 170 | < 25 |

| Chloropyriphos-methyl | C₇H₇Cl₃NO₃PS | 322.5 | 3000 | 4.0 | 3.00 × 10−3 | 4.31 | 0.08 | 7.0 | 1.642 | - | 46 |

| Pirimiphos Methyl | C11H20N3O3PS | 305.33 | 1000 | 9.0 | 1.5 × 10−2 | 4.12 | 1.53 | 10 | 1.17 | - | 15 |

| Fenitrothion | C9H12NO5PS | 277.24 | 2000 | 38.0 | 18 × 10−3 | 3.30 | 0.48 | 4 | 1.3 | 118 | 0.3 |

| Pirimiphos Ethyl | C₁₃H₂₄N₃O₃PS | 333.39 | 300 | 2.3 | 93 | 5.0 | 2.52 | 45 | 1.14 | - | 15–18 |

| Quinalphos | C12H15N2O3PS | 298.30 | 2260 | 17.8 | 3.46 × 10−5 | 3.53 | 1.10 | - | 1.30 | - | 31 |

| Chlorpyrifos | C9H11Cl3NO3PS | 350.6 | 6070 | 0.4 | 2.70 × 10−3 | 4.96 | 0.58 | 4.96 | 1.44 | - | 41–42 |

| Triphenyl Phosphate | C18H15O4P | 326.3 | > 2000 | 1.9 | 1.0 | 4.59 | - | - | 1.27 | - | 49–50 |

| EPN | C14H14NO4PS | 323.3 | 4000 | 0.5 | 4.1 × 10−4 | 3.85 | - | 15 | 1.3 | 371 | 36 |

| Phosalone | C12H15ClNO4PS2 | 367.8 | 1800 | 3.0 | Negligible | 4.38 | 0.21 | 21 | 1.4 | - | 46 |

| Pyrazophos | C14H20N3O5PS | 373.37 | 646 | 4.2 | 2.22 × 10−5 | 3.8 | 1.89 | - | 1.348 | - | 51.5 |

| Azinphos-ethyl | C₁₂H₁₆N₃O₃PS₂ | 345.38 | 1500 | 4.5 | 3.20 × 10−5 | 3.18 | 1.40 | - | - | 111 | 53 |

| Pyraclofos | C₁₄H₁₈ClN₂O₃PS | 360.8 | 2097 | 33 | 1.60 × 103 | 3.77 | 1.15 | - | 1.27 | 454 | - |

Sample Collection and determination of soil physicochemical properties

Forty (40) agricultural soil samples were collected from eight areas in the Delta Central District, Nigeria. These areas include Udu (S1-S5), Ughelli South (S6-S10), Ughelli North (S11-S15), Ethiope East (S16-S20), Okpe (S21-S25), Sapele (S26-S30), Sapele (S31-S35) and Ethiope West (S36-S40). Sampling was carried out between January and March 2023. In each farmland, about one kilogram of soil samples were collected with the aid of a soil corer at a depth of 0–20 cm from seven to ten different points and pooled together after foreign materials such as roots, gravel, pebbles, leaves and stones were removed. A single representative or composite sample was then collected by quartering and compartmentalization.

At each farmland where the soil was collected, standing vegetables cultivated there were also harvested. The vegetable seeds which were cultivated by the farmers were obtained from the National Agricultural Seed Council of Nigeria. About 0.5 kg of four different types of vegetables which are pumpkin leaves (Telfairia occidentalis), green leaves (Desmodium intortum cv), bitter leaves (Vernonia amygdalina) and water leaves (Talinum triangulare) were sampled. Soil and vegetable samples were kept in aluminium foil, labelled appropriately, stored in ice and taken to the laboratory. In the laboratory, they were frozen dried, crushed, sieved and kept at -4 oC before analysis. Sterile gloves were used to prevent contamination during the whole process. Furthermore, all the equipment used for sample collection, transportation, and preparation was free from organophosphate pesticide contamination. The pH and electrical conductivity (EC) of the soils were determined after appropriate treatments with a bench-top multi-parameter meter (XS-PC8 + DHS) while the soil total organic carbon (TOC) was determined by the Walkley-Black titration.

Chemical analysis

The extraction procedure of OPPs in the soil and vegetables was adopted from Pan et al.9. Five grams of the soil/vegetable was mixed with 20 ng of 2D-labelled chry and was extracted ultrasonically with 30 mL of 1:4 v/v petroleum ether/acetone for 60 min. The extract was removed into a flask, and the process was continued twice. The extract was concentrated and then the solvent was changed to hexane using a rotary evaporator. Thereafter, the extract was eluted from a column enclosing Na2SO4 and activated Florisil to eliminate impurities. The OPPs were recouped in 60 mL of 1:4 v/v acetone/hexane. The eluent was concentrated, the solvent was changed to hexane, and concentrated to 0.5 mL before analysis. The determination of OPPs was done on a gas chromatograph (Agilent 6890 N) coupled with a mass spectrometry (GC–MS). The temperature at injection was 250 oC, the temperature of the detector was 290 oC while the column was Agilent J&W DB-17 (30 m × 250 μm × 0.25 μm). Carrier gas was helium (99.9% purity) flowing steadily at 0.8 mL/min. A sample of 1 µL was introduced into the instrument in splitless mode. The initial temperature of the oven was 150 oC for 1.3 min, rising to 280 oC at 15 oC/min for 2mins and finally closing at 300 oC for 4 min at a run time of 17.67 min.

Quality control/assurance and method validation

In this study, blanks, spiked recovery, the limit of detection (LOD), the limit of quantification (LOQ), precision and linearity were used for quality control and method validation in accordance to the European Commission guidelines47. OPPs concentrations in blank samples were below their limit of quantifications. For spiked recovery, already analyzed soil and vegetable samples were spiked with standard solutions of the OPPs at three concentration levels (5, 10 and 20 ng mL−1) and the spiked samples were analyzed. Thereafter the percentage recoveries were computed. The percentage of OPPs recovered ranged between 83.8% and 98.6% for soil and 85.4% and 97.1% for vegetables. The recoveries were within the accepted range of 70–120%47–49. The linearity of the method was achieved with calibration curves of standard OPPs solutions at seven concentration levels. The LOD (limit of detection) was calculated from the OPPs concentration that produced a signal : noise = 3, whereas the LOQ (limit of quantification) was calculated from the OPPs concentration that produced a signal : noise = 10. The LOD and LOQ of the OPPs congeners ranged from 0.003 to 0.04 ng mL−1 and 0.01 to 0.12 ng mL−1 respectively for soil and 0.003 to 0.017 ng mL−1 and 0.01 to 0.05 ng mL−1 respectively for vegetables. The RSD for replicate analysis (n = 3) for both soil and vegetables was < 8%. The precision was within the acceptable range of ≤ 20% RSD47–49. The R2 values obtained from the calibration curves ranged from 0.9994 to 0.9999 for soil and 0.9993 to 0.9999 for vegetables. The detailed results for method validation and quality control such as values of LODs, LOQs, linearity, repeatability, R2 and percentage recoveries of the individual OPP congeners are shown in Tables SM1 and SM2 as well as Figures SM1-SM6.

Statistical analysis

The analysis of data was done with the IBM-SPSS software (version 23). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilks normality tests were performed on the data. With the data leaning toward non-normal, the Kruskal Wallis H test was used to determine the degree of variations in OPPs levels in the soils and vegetables concerning sampling areas and vegetable types using a 95% confidence limit. Pearson’s correlation analysis was employed to determine if there were significant relationships among the OPPs and between OPPs levels in soil and soil physicochemical properties. Furthermore, PCA was utilized to determine the OPPs sources while hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) was used to classify the variations in the OPPs concentrations.

Estimation of Bioconcentration factor

The bioconcentration factor (BCF) of OPPs in the vegetables was determined with the equation:

|

1 |

Ecological risk assessment (ERA)

The toxicity exposure ratio (TER) for four chosen species of soil organisms50 and the risk quotient (RQ) for each OPP43,51 were used to evaluate the ERA. The TER and RQ were determined to evaluate chronic ERA when the no observable effect concentration (NOEC) value for a given OPP was known from the literature review. The mean soil OPPs concentration (MSCmean) and the maximum soil OPPs concentration (MSCmax) obtained from the study were used. This provides a worst-case situation (TERmax or RQmax) in the latter and a general situation (TERmean or RQmean) in the former52. The TER and RQ for individual OPP was assessed using the Eqs. (2) and (3):

|

2 |

|

3 |

The pesticide properties database (PPDB), the EFSA draft assessment reports (DARs), and a literature review using Scopus and the Web of Science Core Collection databases served as the foundation for selecting toxicity data for the ERA. The NOEC, LC50 and EC50 for organisms such as the earthworm (E. fetida), the enchytraeid (E. crypticus), the springtail (F. candida) and the mite (H. aculifer) were examined to evaluate the ecological risk. Any study evaluating pesticides for approval by the European Union must take these organisms into account. For the current study, information from earlier research that complied with the established practices for the organisms developed by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) was taken into account. The current investigation was predicated on the known NOEC endpoints only. Only four (diazinone, pirimiphos methyl, fenitithion, and chlorpyrifos) of the fourteen OPPs have known NOECs for the examined species and these were used in the TER and RQ calculations. The predicted no-effect concentration (PNECmss) for the most vulnerable species was calculated with the NOEC value. The least long-term NOEC divided by the assessment factor (AF) was used to estimate the PNECmss value. The choice of the AF may be between 10 and 1000 based on the EU guiding document50. In our study, an AF of 10 was used. The data used for the ecological risk assessment are shown in Table SM3. A benchmark of 5 for chronic toxicity for soil organisms was set by EC50. A TER value > 5 thus indicates no risk while TER < 5 indicates risk43. An RQ < 0.01 = no risk, RQ > 0.01but < 0.1 = low risk, RQ > 0.1 but < 1 = medium risk and RQ ≥ 1 = high risk51,53.

Using the concentration addition (CA) approach54,55, the risk of OPP combinations was calculated by summing up all the different OPPs risks with the same mechanism of action56. The RQ of each OPP was added up to obtain the RQ of the OPPs mixture (RQmix). Additionally, using the CA and the presumption that all pesticides in a mixture have the same mechanism of action, the overall risk of numerous OPPs at a particular sampling site (RQSS) was calculated using the Eqs. (4) and (5):

|

4 |

The interpretation of ∑RQSS and ∑RQmix is the same as mentioned for the RQ above.

The contribution of each RQi to RQSS or RQmix was obtained using the equation:

|

5 |

Health risks evaluation of OPPs in the soils and vegetables

The health risks of OPPs in the soils and vegetables were evaluated using the 95% upper-class limit concentrations (CUCL95%) of the OPPs in each of the eight areas and four vegetables that give the “reasonable maximum exposure”57,58 and have been used extensively by several researchers59–61. The CUCL95% was used because the results of OPPs in the soils and vegetables leaned and skewed toward non-normal distribution27. The CUCL95% was computed using the Eq. (6)59,60;

|

6 |

where X = arithmetic mean;  = (1-

= (1- )th quantile of a normal data = 1.645 for 95% confidence limit, α = possibility of having Type 1 error, β = skewness, n = samples number, SD = standard deviation.

)th quantile of a normal data = 1.645 for 95% confidence limit, α = possibility of having Type 1 error, β = skewness, n = samples number, SD = standard deviation.

The non-carcinogenic risk of OPPs in the agrarian soils was evaluated as a hazard index (HI) based on the two major exposure routes of ingestion and dermal contact. However, only the dietary ingestion route was used for vegetables. The hazard index was obtained using Eqs. (7)–(10)62–65.

|

7 |

|

8 |

|

9 |

|

10 |

Where HQ is hazard quotient and CDI is chronic daily intake. RfD (in mg kg−1 day−1) is the oral reference dose which includes RfDIngestion for ingestion and RfDDermal for dermal contact. RfDDermal = GIABS × RfDIngestion. The RFDIngestion used were chlorpyrifos (1 × 10−3), chlorpyrifos methyl (1 × 10−2), diazinone (7 × 10−4), pirimiphos methyl (7.3 × 10−4), quinalphos (5 × 10−4), azinphos ethyl (3 × 10−3) and EPN (1 × 10−5)64. The definitions and values of other variables used in the above equations are given in Table SM4. Usually, an HI value above 1 shows that there is a potential non-cancer risk64.

Results and discussions

OPPs concentrations in the soils

The concentrations of OPPs in the agrarian soils are presented in Table 2 and Table SM5. The concentrations of the OPPs in the soils were based on dry weight (dw). The detection frequency of the individual OPPs congeners in the soils varied from 83 to 100%.

Table 2.

Summary statistics of OPPs concentrations (ng g−1) in agricultural soils.

| All Samples (n = 40) | Udu (n = 5) | Ughelli South (n = 5) | Ughelli North (n = 5) | Ethiope East (n = 5) | Okpe (n = 5) | Uvwie (n = 5) | Sapele (n = 5) | Ethiope West (n = 5) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DF | Mean ± SD (Range) | Mean ± SD (Range) | CUCL95% | Mean ± SD (Range) | CUCL95% | Mean ± SD (Range) | CUCL95% | Mean ± SD (Range) | CUCL95% | Mean ± SD (Range) | CUCL95% | Mean ± SD (Range) | CUCL95% | Mean ± SD (Range) | CUCL95% | Mean ± SD (Range) | CUCL95% | |

| pH | 100 | 5.81 ± 0.63 | 6.58 ± 0.24 | - | 5.93 ± 0.39 | - | 6.17 ± 0.55 | - | 5.68 ± 0.39 | - | 5.44 ± 0.22 | - | 5.59 ± 0.88 | - | 5.59 ± 0.84 | - | 5.46 ± 0.56 | - |

| (4.30–6.88) | (6.30–6.88) | (5.57–6.48) | (5.39–6.82) | (5.10–6.18) | (5.19–5.74) | (4.50–6.50) | (4.30–6.38) | (4.60–5.90) | ||||||||||

| EC (µS cm−1) | 100 | 21.6 ± 2.77 | 20.7 ± 0.57 | - | 20.5 ± 0.52 | - | 23.6 ± 2.89 | - | 20.2 ± 2.24 | - | 20.4 ± 2.66 | - | 22.0 ± 3.22 | - | 22.5 ± 3.84 | - | 23.2 ± 3.52 | - |

| (17.4–28.3) | (20.0-21.3) | (19.9–21.3) | (20.4–26.7) | (17.5–23.6) | (17.4–24.7) | (19.2–27.3) | (19.6–28.3) | (18.3–26.6) | ||||||||||

| TOC (%) | 100 | 1.02 ± 0.38 | 1.04 ± 0.17 | - | 1.12 ± 0.27 | - | 1.25 ± 0.43 | - | 1.01 ± 0.25 | - | 0.84 ± 0.12 | - | 1.01 ± 0.49 | - | 0.91 ± 0.47 | - | 1.02 ± 0.65 | - |

| (0.25–1.77) | (0.84–1.23) | (0.84–1.41) | (0.79–1.72) | (0.66–1.25) | (0.67–0.98) | (0.32–1.53) | (0.49–1.65) | (0.25–1.77) | ||||||||||

| Diazinone | 100 | 8.89 ± 31.6 | 3.56 ± 3.18 | 5.21 | 2.97 ± 1.15 | 4.61 | 3.90 ± 2.47 | 5.54 | 0.03 ± 0.04 | 1.68 | 50.4 ± 84.2 | 52.1 | 6.93 ± 7.18 | 8.58 | 3.15 ± 3.29 | 4.79 | 0.06 ± 0.04 | 1.71 |

| (0.01–201) | (0.71–8.69) | (1.41–4.58) | (0.07–6.07) | (0.01–0.10) | (5.51–201) | (1.57–14.9) | (0.03–7.80) | (0.03–0.12) | ||||||||||

| Isazophos | 83 | 5.38 ± 15.2 | 1.98 ± 3.93 | 3.63 | 2.12 ± 4.47 | 3.76 | 0.06 ± 0.05 | 1.71 | 0.001 ± 0.0 | 1.65 | 32.1 ± 34.2 | 33.8 | 3.00 ± 1.87 | 4.65 | 2.89 ± 3.63 | 4.54 | 0.86 ± 1.76 | 2.51 |

| (ND-83.7) | (0.05–9.01) | (ND-10.1) | (0.01–0.13) | (ND-0.01) | (0.13–83.7) | (1.17–6.09) | (0.01–8.40) | (ND-4.01) | ||||||||||

| Chloropyriphos-methyl | 100 | 12.1 ± 17.1 | 2.62 ± 2.51 | 4.27 | 3.97 ± 2.28 | 5.61 | 6.26 ± 3.49 | 7.91 | 0.22 ± 0.09 | 1.86 | 32.1 ± 13.2 | 33.7 | 39.2 ± 16.1 | 40.9 | 11.4 ± 20.6 | 13.1 | 1.13 ± 2.17 | 2.78 |

| (0.02–64.9) | (0.41–6.90) | (0.90–6.74) | (1.05–8.83) | (0.09–0.33) | (18.2–50.2) | (22.0-64.9) | (0.02-48.0) | (0.02–5.01) | ||||||||||

| Pirimiphos Methyl | 88 | 23.8 ± 65.6 | 4.46 ± 2.56 | 6.11 | 5.05 ± 5.93 | 6.70 | 3.14 ± 6.33 | 4.78 | 0.04 ± 0.06 | 1.68 | 56.6 ± 98.8 | 58.3 | 113 ± 132 | 115 | 6.85 ± 14.6 | 8.50 | 0.62 ± 1.34 | 2.26 |

| (ND-344) | (1.05–7.52) | (0.07–15.1) | (0.01–15.5) | (0.01–0.12) | (ND-228) | (28.0-344) | (0.11-33.0) | (ND-3.01) | ||||||||||

| Fenitrothion | 98 | 8.47 ± 16.3 | 12.5 ± 8.59 | 14.1 | 10.8 ± 6.24 | 12.4 | 8.69 ± 7.83 | 10.3 | 0.63 ± 0.19 | 2.27 | 26.7 ± 41.2 | 28.3 | 3.62 ± 6.77 | 5.27 | 4.65 ± 6.10 | 6.30 | 0.28 ± 0.33 | 1.93 |

| (ND-98.2) | (4.65–24.5) | (1.26-17.0) | (0.70–17.4) | (0.31–0.81) | (0.03–98.2) | (ND-15.7) | (0.36–15.2) | (0.01–0.74) | ||||||||||

| Pirimiphos Ethyl | 85 | 9.92 ± 13.2 | 18.8 ± 6.88 | 20.5 | 12.6 ± 4.15 | 14.3 | 13.5 ± 15.6 | 15.2 | 0.18 ± 0.06 | 1.82 | 0.57 ± 1.26 | 2.21 | 26.2 ± 19.6 | 27.8 | 7.35 ± 14.4 | 8.99 | 0.22 ± 0.27 | 1.87 |

| (ND-49.7) | (6.59–22.9) | (8.19–19.2) | (0.17–36.7) | (0.12–0.24) | (ND-2.83) | (0.04–49.7) | (0.03-33.0) | (0.01–0.57) | ||||||||||

| Quinalphos | 90 | 4.72 ± 10.3 | 9.80 ± 18.2 | 11.4 | 4.63 ± 8.68 | 6.28 | 3.74 ± 4.45 | 5.38 | 1.49 ± 0.41 | 3.13 | 5.10 ± 4.73 | 6.75 | 10.1 ± 21.5 | 11.7 | 2.53 ± 3.59 | 4.18 | 0.42 ± 0.58 | 2.07 |

| (ND-48.6) | (0.19–42.1) | (0.15–20.1) | (0.28–11.4) | (0.78–1.86) | (ND-11.7) | (ND-48.6) | (0.02–8.70) | (ND-1.34) | ||||||||||

| Chlorpyrifos | 98 | 15.7 ± 34.2 | 29.3 ± 13.9 | 30.9 | 17.9 ± 11.2 | 19.5 | 21.2 ± 20.7 | 22.8 | 0.28 ± 0.15 | 1.92 | 4.87 ± 3.13 | 6.51 | 9.92 ± 18.7 | 11.6 | 42.2 ± 91.8 | 43.8 | 0.25 ± 0.33 | 1.90 |

| (ND-206) | (10.9–43.3) | (8.01–35.4) | (0.36–42.8) | (0.11–0.48) | (0.43–8.49) | (0.04–43.2) | (0.04–206) | (ND-0.66) | ||||||||||

| Triphenyl Phosphate | 90 | 14.9 ± 25.7 | 34.3 ± 20.0 | 35.9 | 24.5 ± 16.3 | 26.1 | 18.2 ± 9.13 | 19.9 | 2.79 ± 1.00 | 4.44 | 2.03 ± 3.49 | 3.68 | 8.19 ± 17.8 | 9.83 | 28.5 ± 61.9 | 30.1 | 1.03 ± 0.59 | 2.68 |

| (ND-139) | (16.1–65.1) | (8.57–42.2) | (2.00-23.1) | (1.29–3.94) | (ND-8.06) | (ND-40.1) | (0.33–139) | (0.11–1.97) | ||||||||||

| EPN | 93 | 2.11 ± 3.38 | 1.85 ± 3.54 | 3.49 | 2.32 ± 4.94 | 3.97 | 1.79 ± 1.80 | 3.43 | 1.41 ± 1.50 | 3.05 | 0.91 ± 1.77 | 2.56 | 3.14 ± 5.07 | 4.79 | 1.63 ± 1.94 | 3.27 | 3.81 ± 5.35 | 5.46 |

| (ND-13.3) | (0.17–8.18) | (ND-11.2) | (0.03–4.42) | (0.55–4.07) | (ND-4.05) | (0.07–11.8) | (0.20–5.01) | (0.30–13.3) | ||||||||||

| Phosalone | 100 | 7.81 ± 8.10 | 18.1 ± 8.93 | 19.7 | 14.9 ± 9.39 | 16.6 | 12.5 ± 7.93 | 14.2 | 4.87 ± 1.53 | 6.52 | 3.55 ± 3.86 | 5.19 | 3.53 ± 4.67 | 5.17 | 1.00 ± 1.19 | 2.64 | 3.95 ± 3.35 | 5.59 |

| (0.01–28.5) | (7.77–28.5) | (2.67–24.3) | (3.83–24.3) | (2.32–6.40) | (0.09–10.1) | (0.07–9.42) | (0.03–2.59) | (0.01–8.16) | ||||||||||

| Pyrazophos | 98 | 9.55 ± 11.7 | 16.9 ± 6.73 | 18.6 | 14.2 ± 8.48 | 15.8 | 13.6 ± 10.1 | 15.2 | 7.20 ± 1.89 | 8.84 | 4.86 ± 8.10 | 6.51 | 0.31 ± 0.22 | 1.95 | 2.35 ± 4.00 | 3.99 | 17.0 ± 25.4 | 18.7 |

| (ND-61.7) | (11.8–26.6) | (2.91–22.5) | (6.35-31.0) | (4.68–9.07) | (ND-19.2) | (0.20–0.71) | (0.12–9.47) | (1.05–61.7) | ||||||||||

| Azinphos-ethyl | 90 | 6.31 ± 7.15 | 9.53 ± 4.33 | 11.2 | 8.91 ± 7.44 | 10.6 | 9.57 ± 5.07 | 11.2 | 8.28 ± 2.45 | 9.93 | 0.61 ± 1.01 | 2.26 | 10.2 ± 15.0 | 11.9 | 0.94 ± 1.11 | 2.59 | 2.36 ± 3.07 | 4.00 |

| (ND-34.2) | (3.93–15.8) | (3.24–21.5) | (5.47–17.8) | (4.10–10.5) | (ND-2.32) | (ND-34.2) | (0.10–2.86) | (0.02–7.68) | ||||||||||

| Pyraclofos | 88 | 7.64 ± 13.3 | 4.47 ± 2.12 | 6.11 | 2.99 ± 1.64 | 4.63 | 4.85 ± 2.13 | 6.49 | 8.92 ± 2.58 | 10.6 | ND | - | 35.9 ± 22.0 | 37.6 | 1.64 ± 1.98 | 3.28 | 2.35 ± 3.27 | 4.00 |

| (ND-53.7) | (1.33–6.66) | (1.91–5.82) | (2.97–8.03) | (4.56–10.8) | ND | (3.60–53.7) | (0.10–5.09) | (0.07–8.13) | ||||||||||

| Total | 100 | 137 ± 117 | 168 ± 53.5 | 170 | 128 ± 40.3 | 129 | 121 ± 52.7 | 123 | 36.2 ± 10.3 | 37.9 | 220 ± 131 | 222 | 274 ± 142 | 275 | 117 ± 164 | 119 | 34.3 ± 38.1 | 36.0 |

| (5.21–419) | (102–239) | (69.5–180) | (42.5–177) | (19.3–44.4) | (72.3–364) | (117–419) | (18.9–403) | (5.21–101) | ||||||||||

DF = Detection Frequency; EC = Electrical Conductivity; TOC = Total Organic Carbon; ND = Not detected.

This high detection rate of OPPs in these agricultural soils is an indication of ubiquitous pollution of the soils by OPPs which may be a result of intensive usage in agricultural activities. The ∑14 OPPs concentrations in the agricultural soils ranged from 5.29 to 419 ng g−1 with an average of 137 ng g−1. The maximum ∑14 OPPs concentration was found at location S28 in Uvwie while the minimum ∑14 OPPs concentration was found at location S39 in Ethiope West. Soil samples from S3, S22, S23, S25, S26, S27, S28 and S32 have elevated levels of OPPs relative to other sites. The OPPs concentrations in the soils varied significantly (p < 0.05) from one location to another. This could be due to the soil’s physicochemistry, variable OPPs sources, degree of pollution, rate of OPP mobility and degradation, as well as the frequency and style of OPPs application24,67. The average ∑14 OPPs concentrations in all the locations followed the order: Uvwie > Okpe > Udu > Ughelli South > Ughelli North > Sapele > Ethiope East > Ethiope West. Udu recorded the maximum mean levels of chlorpyrifos (29.3 ng g−1), triphenyl phosphate (34.3 ng g−1) and phosalone (18.1 ng g−1). Okpe recorded the maximum mean levels of diazinone (50.4 ng g−1), isazophos (32.1 ng g−1) and fenitrothion (26.7 ng g−1). The maximum mean levels of chlorpyriphos-methyl (39.2 ng g−1), pirimiphos-methyl (113 ng g−1), pirimiphos-ethyl (26.2 ng g−1), quinalphos (10.1 ng g−1), EPN (3.14 ng g−1), azinphos-ethyl (10.2 ng g−1) and pyraclofos (35.9 ng g−1) were found in Uvwie while Sapele and Ethiope west have the maximum mean levels of chlorpyrifos (42.2 ng g−1) and pyrazophos (17.0 ng g−1) respectively. On average, the concentrations of the OPPs in the soils were in the order pirimiphos methyl > chlorpyrifos > triphenyl phosphate > chlorpyrifos-methyl > pirimiphos-ethyl > pyrazophos > diazinone > fenitrithion > phosalone > pyraclofos > azinphos-ethyl > isazophos > quinalphos > EPN. The ∑14 OPPs concentrations obtained in this study were comparable to the range of < 3.0-521 ng g−1 documented by Pan et al.9. for agrarian soils of Yangtze River Delta (YRD), China; 1.23–239 ng g−1 reported for agrarian soils of Nepal41 and the range of < LOD to 991 ng g−1 reported for agricultural soils of the Pearl River Delta, China45.

Compositional pattern of OPPs in the soils

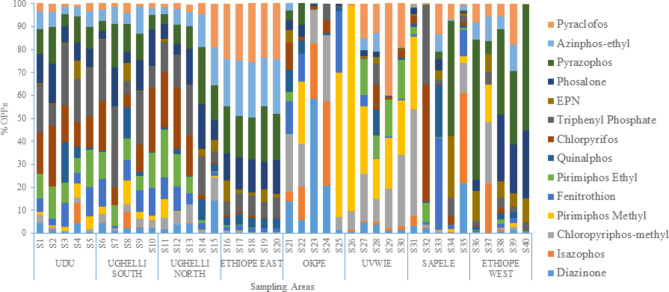

The compositional patterns of the OPPs in the agrarian soils are presented in Fig. 2. The diazinone levels varied between 0.01 and 201 ng g−1 constituting 0.02 to 58.4% of the ∑14 OPPs. The diazinone concentration range obtained in our study was lower than the 810–1180 ng g−1 found by Mahmud et al.68. in agrarian soils from Northern, Nigeria and the concentrations documented by Akan et al.69. in agrarian soils from northern Nigeria. The isazophos concentrations in 83% of the samples varied from 0.01 to 83.7 ng g−1 and accounted for 0.1 to 39.4% of the ∑14 OPPs. Isazophos was not detected in the soil of locations S7, S10, S16, S17, S18, S19 and S39. The concentrations of chloropyrifos-methyl in all the agricultural soils ranged from 0.02 to 64.9 ng g−1. Chloropyrifos-methyl constituted 0.11 to 46.2% of the ∑14 OPPs. The pirimiphos-methyl concentrations in 85% of the agricultural soils ranged from 0.01 to 344 ng g−1. Pirimiphos-methyl was not detected at S19, S21, S23, S24, S38 and S40. Pirimiphos-methyl constituted 0.1 to 89.4% of the ∑14 OPPs. The concentration ranges of pirimiphos-methyl obtained in our study were comparable to the 10–40 ng g−1 documented by Fosu-Mensah et al.34. in soils from Cocoa farms in Ghana but lower than the range of 2500 to 6050 ng g−1 reported for soil from farm settlement in Nigeria70. The fenitrothion levels in 98% of the soils varied from 0.01 to 98.2 ng g−1 and made up 0.1 to 40.0% of the ∑14 OPPs. The fenitrothion levels obtained in our study were below the concentration of 120 ng g−1 reported for agrarian soils from Pakistan71; 580–900 ng g−1 documented by Mahmud et al.68. and the concentrations reported by Akan et al.69.

Fig. 2.

Compositional pattern of OPPs in the soils based on concentration distribution.

The pirimiphos-ethyl content in 85% of soils ranged from 0.01 to 49.7 ng g−1 and constituted 0.1 to 17% of the ∑14 OPPs. The quinalphos levels in 90% of the soils ranged from 0.02 to 48.6 ng g−1 in the soils and constituted 0.1 to 22.9% of the ∑14 OPPs. The chlorpyrifos content in 98% of the agrarian soils ranged between 0.01 and 206 ng g−1 constituting 0.1 to 51.1% of the ∑14 OPPs. The chlorpyrifos content found in our study was lower than the 520–970 ng g−1 documented by Mahmud et al.68. , 28,600 ng g−1 and 32,200 ng g−1 reported for winter and summer respectively in vegetable-cultivated soils from Khon Kaen Province, Thailand72 and nd-6810 ng g−1 reported by Awe et al.70. but comparable to 10–40 ng g−1 reported by Fosu-Mensah et al.34. The chlorpyrifos concentrations obtained in our study were also lower than the values reported by Akan et al.69. The triphenyl phosphate concentrations in 90% of the agrarian soils ranged from 0.08 to 139 ng g−1 and constituted 0.1 to 34.5% of the ∑14 OPPs. The EPN contents in 93% of the soils ranged between 0.03 and 13.3 ng g−1 and constituting 0.1 to 26.5% of the ∑14 OPPs. The phosalone content in the agrarian soils ranged between 0.01 and 28.5 ng g−1 constituting 0.02 to 29.5% of the ∑14 OPPs. The pyrazophos content in 98% of the soils ranged between 0.12 and 61.7 ng g−1 constituting 0.1 to 61.1% of the ∑14 OPPs. The pyrazophos found in our study were lower than the range nd-18,100 ng g−1 reported by Awe et al.70. The azinphos-ethyl concentrations in 90% of the soils and pyraclofos concentrations in 88% of the soils varied between 0.02 and 34.2 ng g−1 and 0.07 to 53.7 ng g−1 respectively. Azinphos-ethyl and pyraclofos constituted 0.1 to 24.2% and 0.2 to 40.3% of the ∑14 OPPs respectively.

Organophosphate pesticides (OPPs) primarily enter the environment through agricultural applications73. These pesticides are highly hydrophilic, meaning they have a strong affinity for water, leading to significant absorption in soil and subsequent accumulation in agricultural runoff. The extent of their hydrophilicity is largely determined by their octanol-water partition coefficient (Kow), which also influences their volatility and lipophilicity in environmental media74. OPPs with lower Kow values are more water soluble and less prone to evaporation, whereas those with higher Kow values are more lipophilic and have a greater tendency to evaporate. The adsorption of OPPs in the soil is heavily influenced by the organic content of the soil; hydrophilic soils absorb lower amounts of OPPs compared to hydrophobic soils75. Additionally, the presence of OPPs in soil is influenced by their degradation, which can occur through photodegradation and chemical degradation. The former is more prevalent, triggered by sunlight exposure, particularly on soil surfaces, as well as in water and plants. This photolysis process can produce pesticide metabolites that may pose greater hazards than the original compounds76.

Relationship between soil characteristics and OPPs

Soil characteristics like pH, EC and TOC may influence the occurrence pattern, behaviour and the entire geochemistry of OPPs in soil. For instance, increasing the soil TOC content provides an additional carbon source for the breaking down of pesticides by micro-organisms24,77. The pH values of the agricultural soils ranged between 4.30 at S34 to 6.88 at S3 with a mean of 5.81. The pH values suggested that the agricultural soils were acidic. The soil EC ranged between 17.4 µS cm−1 at S21 and 28.3 µS cm−1 at S35 with an average of 21.6 µS cm−1 while The TOC of the soils ranged between 0.25% at S37 and 1.67% at S36 with an average of 1.02% (Table 2 and SM5). The values found for the soil characteristics were comparable to those documented24,78–80 for agricultural soils of southern Nigeria.

In our study, there was no significant relationship between Ʃ14 OPPs and the soil characteristics (Figure SM7 and Table SM6). This suggests that soil characteristics play no influential part in the OPPs geochemistry of the agrarian soils. Furthermore, there was no significant positive relationship between soil characteristics and the individual OPPs in the soil (Table SM6). This indicates that the soil characteristics do not influence the OPPs because the fate of OPPs in the agrarian soils could be linked to a variety of reasons comprising continuous input of new OPPs, disequilibrium due to agricultural activities, multiple sources, different mixing and/or transport mechanisms and degradation24,81. Pan et al.9. have previously reported that no significant relationship existed between ∑OPPs concentration and soil pH in agrarian soils from YRD, China whereas TOC was positively correlated with ∑OPPs. However, among the OPPs, a positive correlation was observed. The positive correlations found between these OPPs pairs indicate there is a similarity in their source input and distribution patterns. Their application in agriculture may perhaps be their entry route into the soils24,77.

Concentrations of OPPs in vegetables

The concentrations of OPPs in the vegetables are shown in Table 3 and Table SM7. The concentrations of the OPPs in the vegetables were also on a dry weight (dw) basis. The detection frequency of the individual OPPs congeners in the vegetables varied from 93 to 100%. The presence of OPPs in the studied vegetables could be because vegetables are extremely vulnerable to pests during cultivation and constant usage of pesticides is necessary to get rid of pests, which ultimately lead to their elevated levels82. The levels of OPPs in the vegetables were lower than those found in the corresponding soils. The OPPs concentrations in the vegetables varied considerably (p < 0.05) with vegetable type and among the different vegetables. This might be a result of the difference in bioaccumulation tendency of each vegetable, frequency and style of OPPs application among others.

Table 3.

Summary statistics of OPPs concentrations (ng g-1) in vegetables.

| All Samples (n = 40) | Pumpkin Leaves (n = 13) | Green Leaves (n = 11) | Bitter Leaves (n = 9) | Water Leaves (n = 7) | EU MRLs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DF | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | CUCL95% | Mean ± SD | CUCL95% | Mean ± SD | CUCL95% | Mean ± SD | CUCL95% | ||

| Diazinone | 100 | 4.74 ± 13.6 | 5.97 ± 11.4 | 10.5 | 0.98 ± 0.91 | 2.71 | 0.76 ± 1.31 | 2.86 | 13.5 ± 28.3 | 26.1 | 10 |

| (0.09–76.9) | (0.09–42.1) | (0.10–2.94) | (0.19–4.23) | (0.12–76.9) | |||||||

| Isazophos | 98 | 2.07 ± 3.17 | 2.48 ± 3.63 | 4.62 | 3.10 ± 4.01 | 5.38 | 0.54 ± 0.96 | 2.52 | 1.65 ± 2.26 | 4.00 | 10 |

| (ND-12.4) | (ND-11.3) | (0.01–12.4) | (0.14–3.08) | (0.03–6.47) | |||||||

| Chloropyriphos-methyl | 95 | 1.20 ± 2.69 | 1.99 ± 4.20 | 4.64 | 1.85 ± 1.95 | 3.62 | 0.04 ± 0.03 | 1.69 | 0.23 ± 0.21 | 1.89 | 10 |

| (ND-15.1) | (0.01–15.1) | (0.01–5.28) | (ND-0.11) | (ND-0.54) | |||||||

| Pirimiphos Methyl | 93 | 1.55 ± 3.00 | 2.64 ± 4.18 | 4.86 | 2.00 ± 2.97 | 4.17 | 0.48 ± 1.22 | 2.56 | 0.17 ± 0.22 | 1.86 | 10 |

| (ND-12.6) | (ND-12.6) | (0.01–9.40) | (ND-3.73) | (ND-0.58) | |||||||

| Fenitrothion | 100 | 1.41 ± 2.22 | 1.65 ± 2.52 | 3.79 | 2.08 ± 2.59 | 4.28 | 0.78 ± 1.85 | 3.09 | 0.75 ± 1.17 | 2.86 | 10 |

| (0.01–9.11) | (0.07–9.06) | (0.01–9.11) | (0.05–5.72) | (0.19–3.39) | |||||||

| Pirimiphos Ethyl | 100 | 1.43 ± 1.92 | 2.05 ± 2.69 | 4.03 | 1.62 ± 1.67 | 3.41 | 0.48 ± 0.66 | 2.31 | 1.21 ± 1.38 | 3.13 | 10 |

| (0.01–8.84) | (0.05–8.84) | (0.01–5.07) | (0.09–2.10) | (0.11–3.76) | |||||||

| Quinalphos | 98 | 1.38 ± 2.69 | 1.36 ± 2.38 | 3.54 | 2.97 ± 3.93 | 5.23 | 0.06 ± 0.05 | 1.71 | 0.61 ± 1.37 | 2.80 | 10 |

| (ND-12.3) | (0.02–8.61) | (0.01–12.3) | (0.01–0.18) | (ND-3.71) | |||||||

| Chlorpyrifos | 95 | 1.36 ± 2.22 | 1.51 ± 2.27 | 3.53 | 2.07 ± 2.77 | 4.10 | 0.75 ± 2.00 | 3.11 | 0.76 ± 1.31 | 2.90 | 10 |

| (ND-8.08) | (0.03–7.72) | (ND-8.08) | (0.04–6.08) | (ND-3.68) | |||||||

| Triphenyl Phosphate | 93 | 1.30 ± 2.47 | 0.88 ± 1.97 | 2.92 | 2.63 ± 3.19 | 4.56 | 0.90 ± 2.53 | 3.44 | 0.53 ± 1.31 | 2.71 | 10 |

| (ND-8.13) | (ND-6.42) | (ND-8.13) | (0.01–7.64) | (ND-3.51) | |||||||

| EPN | 100 | 1.74 ± 2.23 | 2.05 ± 2.50 | 3.99 | 2.23 ± 2.35 | 4.18 | 0.79 ± 1.67 | 3.02 | 1.64 ± 2.23 | 4.03 | 10 |

| (0.05–8.26) | (0.05–8.26) | (0.08–7.81) | (0.05–5.22) | (0.12–6.46) | |||||||

| Phosalone | 90 | 1.04 ± 1.96 | 0.80 ± 1.48 | 2.69 | 2.02 ± 2.99 | 4.14 | 0.31 ± 0.35 | 2.07 | 0.85 ± 1.63 | 3.14 | 10 |

| (ND-8.80) | (ND-4.36) | (0.01–8.80) | (0.11–1.22) | (ND-4.54) | |||||||

| Pyrazophos | 95 | 1.24 ± 1.83 | 1.28 ± 1.51 | 3.07 | 2.35 ± 2.59 | 4.19 | 0.26 ± 0.31 | 2.00 | 0.69 ± 1.37 | 2.88 | 10 |

| (ND-6.91) | (ND-4.01) | (0.02–5.91) | (0.05–1.06) | (ND-3.79) | |||||||

| Azinphos-ethyl | 98 | 1.61 ± 2.17 | 2.00 ± 2.50 | 3.87 | 2.09 ± 2.13 | 3.92 | 0.74 ± 1.60 | 2.94 | 1.26 ± 2.29 | 3.81 | 10 |

| (ND-7.52) | (0.04–7.52) | (ND-6.43) | (0.03–4.96) | (0.23–6.43) | |||||||

| Pyraclofos | 93 | 1.83 ± 2.88 | 1.87 ± 2.81 | 3.79 | 2.86 ± 3.35 | 4.80 | 1.05 ± 2.49 | 3.56 | 1.17 ± 2.82 | 3.95 | 10 |

| (ND-9.49) | (ND-7.69) | (ND-9.49) | (0.03–7.65) | (ND-7.55) | |||||||

| Total | 100 | 23.9 ± 31.5 | 28.5 ± 34.5 | 34.3 | 30.9 ± 25.1 | 32.1 | 7.93 ± 15.5 | 14.9 | 25.0 ± 46.6 | 45.0 | |

| (0.69–130) | (1.09–103) | (0.69-66.0) | (1.34–48.9) | (1.74–130) | |||||||

The ∑14 OPPs concentrations in the vegetables ranged from 1.09 to 103 ng g−1 with an average of 28.5 ng g−1 for pumpkin leaves, 0.69 to 66.0 ng g−1 with an average of 30.9 ng g−1 for green leaves, 1.34 to 48.9 ng g−1 with an average of 7.93 ng g−1 for bitter leaves and 1.74 to 130 ng g−1 with an average of 25.0 ng g−1 for water leaves. The average ∑14 OPPs concentrations in all the locations were in the order of Green leaves > Pumpkin leaves > Water leaves > Bitter leaves. Vegetables from sampling locations S1-S5, S7, S8, S10, S13, S14 and S27 have higher levels of OPPs relative to other sites. The maximum ∑14 OPPs concentration was found in a water leaf sample from Ughelli South (S8) while the minimum ∑14 OPPs concentration was found in a green leaf from Ethiope East (S20). On average, the concentrations of the OPPs in the vegetables were in the order diazinone > isazophos > pyraclofos > EPN > azinphos-ethyl > pirimiphos methyl > pirimiphos ethyl > fenitrothion > quinalphos > chlorpyrifos > triphenyl phosphate > pyrazophos > chloropyriphos methyl > phosalone. Water leaves recorded the highest mean level of diazinone (13.5 ng g−1) while green leaves recorded the highest mean levels of isazophos (3.10 ng g−1), fenitrothion (2.08 ng g−1), quinalphos (2.97 ng g−1), chlorpyrifos (2.07 ng g−1), triphenyl phosphate (2.63 ng g−1), EPN (2.23 ng g−1), phosalone (2.02 ng g−1), pyrazophos (2.35 ng g−1), azinphos-ethyl (2.09 ng g−1) and pyraclofos (2.86 ng g−1). However, the maximum mean levels of chlorpyrifos-methyl (1.99 ng g−1), pirimiphos-methyl (2.54 ng g−1) and pirimiphos-ethyl (2.05 ng g−1) were found in pumpkin leaves.

Compositional pattern of OPPs in the vegetables

The compositional patterns of the OPPs in the vegetables are presented in Fig. 3. The diazinone levels varied between 0.01 and 201 ng g−1 constituting 0.02 to 58.4% of the ∑14 OPPs. The diazinone concentrations were in the order of water leaves > pumpkin leaves > green leaves > bitter leaves. The diazinone concentration range obtained in our study was comparable to the range of 5.0–51.0 ng g−1 found in vegetables from Thailand10.

Fig. 3.

Compositional pattern of OPPs in the vegetables based on concentration distribution.

The isazophos concentrations in 98% of the samples ranged from 0.01 to 12.4 ng g−1 and accounted for 0.2 to 19.9% of the ∑14 OPPs. Isazophos was not detected in vegetables from location S12. The concentrations of isazophos were in the order of green leaves > pumpkin leaves > water leaves > bitter leaves. The concentrations of chloropyrifos-methyl in 95% of the vegetables ranged from 0.01 to 15.1 ng g−1. Chloropyrifos-methyl was not detected in vegetables from S6 and S8. Pumpkin leaf has the highest Chloropyrifos-methyl levels, followed by green leaf, then water leaf and bitter leaf the least. The Chloropyrifos-methyl constituted 0.02 to 21.3% of the ∑14 OPPs. The pirimiphos-methyl concentrations in 93% of the vegetables ranged from 0.01 to 12.6 ng g−1. Pirimiphos-methyl was not detected in vegetables from S8, S12 and S39. The levels of pirimiphos-methyl in the vegetables were in the order of pumpkin leaves > green leaves > bitter leaves > water leaves. Pirimiphos-methyl constituted 0.1 to 21.6% of the ∑14 OPPs. The concentration ranges of pirimiphos-methyl obtained in our study was lower than nd – 12,000 ng g−1 documented by70 in Bananas from Nigeria and also lower than the EU maximum residue limit (MRL) of 10 ng g−1. The fenitrothion levels of the vegetables varied from 0.01 to 9.11 ng g−1 and made up 0.5 to 22.4% of the ∑14 OPPs. Green and water leaves have the highest and least fenitrothion levels respectively. The fenitrothion levels obtained in our study were below the concentration of 15 ng g−1 reported for vegetables from Malaysia40. The pirimiphos-ethyl content ranged from 0.01 to 8.84 ng g−1 and constituted 0.5 to 35.2% of the ∑14 OPPs. The pirimiphos-ethyl was similar to 5 ng g−1 reported by10. The quinalphos levels in 98% of the vegetables ranged from 0.01 to 12.3 ng g−1 and constituted 0.02 to 36.6% of the ∑14 OPPs. The chlorpyrifos content in 95% of the vegetables ranged between 0.01 and 8.08 ng g−1 constituting 0.7 to 14.9% of the ∑14 OPPs. The chlorpyrifos content found in our study was lower than the nd–3330 ng g−1 documented by70; nd −1700 ng g−1 reported by83; 8.0–7785 ng g−1 reported by10 and 220–1830 ng g−1 reported by40. The triphenyl phosphate concentrations in 93% of the vegetables ranged from 0.01 to 8.13 ng g−1 and constituted 0.02 to 15.8% of the ∑14 OPPs. The EPN contents of the vegetables ranged between 0.05 and 8.26 ng g−1 constituting 0.5 to 37.2% of the ∑14 OPPs. The phosalone content in 90% of the vegetables ranged between 0.01 and 8.80 ng g−1 constituting 0.03 to 22.6% of the ∑14 OPPs. The pyrazophos content in 95% of the vegetables ranged between 0.02 and 6.91 ng g−1 constituting 0.1 to 26.6% of the ∑14 OPPs. The pyrazophos content recorded in this study was lower than the nd – 28,400 reported by71. The azinphos-ethyl and pyraclofos concentrations in the vegetables varied between 0.03 and 7.52 ng g−1 and 0.03 to 9.49 ng g−1 respectively. Azinphos-ethyl and pyraclofos constituted 0.8 to 45.9% and 0.4 to 20.6% of the ∑14 OPPs respectively. The amount of OPPs residues in vegetables depends on many factors including the biological properties of the plants and the physicochemical properties of OPPs. These factors may have synergistic or additive effects (negative or positive) on the half-lives of OPPs. Therefore, it can be concluded that under some conditions, some of the OPPs may degrade or be eliminated faster than the others from environment and be undetectable84. Furthermore, plant exudates which are comprised of various phytochemicals and lipids, play a crucial role in OPPs accumulation. These small molecules, released by plants, possess a strong affinity for soil organic content. As a result, they affect the mobility of pollutants such as OPPs, reducing their hydrophobic properties and aiding in their sequestration by plant tissues85,86.

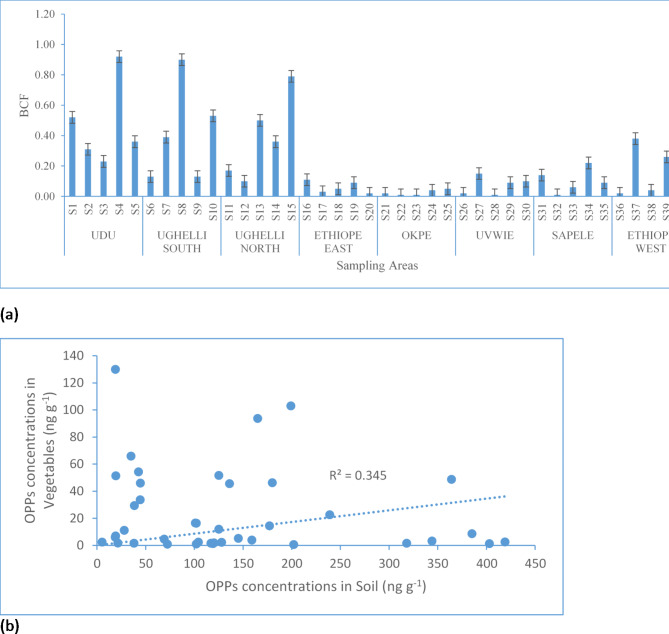

Bioconcentration factor and relationship between OPPs in soil and vegetables

The BCF values computed for the ∑14 OPPs from soils to vegetables are displayed in Fig. 4a. Plants with BCF values > 1 are usually considered as hyperaccumulators87. The maximum BCF value was found in pumpkin leaf from location S4. The lowest BCF value (0.01) was found in bitter leaves from S22 and S23, green leaves from S28 and bitter leaves from S32. The BCF values of the vegetables were generally < 1 (Fig. 4a). Nevertheless, the low BCF observed based on the ∑14 OPPs does not imply that the studied vegetables are not hyperaccumulators as higher BCF were observed for some individual congeners (Table SM8). Linear regression analysis was used to show the inter-relationship between the OPPs concentrations in the soil and the vegetables and the result indicated that there was a poor correlation between OPPs in the soil and vegetables (R2 = 0.345) (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

(a) BCF values of OPPs in the vegetables (b) Regression plot of OPPs in soil vs. vegetables.

Ecological risk evaluation of OPPs in the soils

The computed TER and RQ values are shown in Table 4. For TERmax and TERmean, there was no chronic risk for E. fetida and E. crypticus (TER > 5) but there was a risk for F. candida from chlorpyriphos However, there was a chronic risk for soil organisms from diazinone, pirimiphos methyl and fenitrothion (TER < 5) for the soil organisms. The RQmax and RQmean ranged from 31.7 to 43,000 and 2.42 to 2975 respectively for the OPPs. The RQ values of all the OPPs for both scenarios were > 1. This indicates that there is a potential risk to soil organisms in these agrarian soils. The increasing order of OPPs toxicity to the soil organisms was chlorpyriphos < diazinone < fenitrothion < pirimiphos methyl. Moreover, all the sampling sites represented high risk (∑RQSS or ∑RQmix > 1) as shown in Table SM9. The maximum and least risks were found in sampling sites S26 and S40. The contribution to the ∑RQSS or ∑RQmix ranged from 0.1 to 99.2%, 0.2 to 99.9%, 0.6 to 99.5% and 0.1 to 4.5% for diazinone, pirimiphos methyl, fenitrothion and chlorpyriphos respectively. The fact that different OPPs were found in a given site does not mean that they contributed equally to the overall risk. For instance, fenitrothion recorded the highest contribution in 63% of the sites, followed by pirimiphos methyl with 30% and diazinone with 7.5%. Chlorpyriphos contribution to the overall risk for each site was insignificant.

Table 4.

Toxicity exposure ratios (TERmax and TERmean) and risk quotients (RQmax and RQmean) for soil organisms.

| OPPs | MSCmax | MSCmean | E. fetida | E. crypticus | F. candida | RQmax | RQmean | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic | Chronic | Chronic | ||||||||

| TERmax | TERmean | TERmax | TERmean | TERmax | TERmean | |||||

| Chlorpyrifos | 206 | 15.7 | 61.7 | 809 | 24.3 | 318 | 0.32 | 4.14 | 31.7 | 2.42 |

| Diazinone | 201 | 8.89 | 0.003 | 0.06 | 0.003 | 0.06 | 0.003 | 0.06 | 3589 | 159 |

| Pirimiphos methyl | 344 | 23.8 | 0.0002 | 0.003 | 0.0002 | 0.003 | 0.0002 | 0.003 | 43,000 | 2975 |

| Fenitrothion | 98.2 | 8.47 | 0.0009 | 0.01 | 0.0009 | 0.01 | 0.0009 | 0.01 | 11,287 | 974 |

This observation is at variance with those of other studies which reported significant contribution to the overall risk from chlorpyriphos43,88,89. The variation could be due to the use of lower doses of chlorpyriphos in the study area.

Uncertainty analysis of ecological risks

In ERA, limitations and/or uncertainties are anticipated irrespective of the approach (deterministic or probabilistic) utilized. The erratic nature of environmental stressors, biota effect and exposure data, type of model used, and knowledge gap are all linked to ERA uncertainties90,91. For example, there is little information about OPPs in agricultural soils. One major area of difficulty in the assessment of exposure is the lack of comprehensive OPP data. To obtain more OPPs data at different spatiotemporal levels, more effort needs to be made. The spatiotemporal unpredictability of exposures as well as the likelihood and severity of ecological consequences are not taken into consideration by the RQ technique51. Numerous scholars have suggested and applied a probabilistic technique for a more thorough analysis to solve these constraints. The actual pollutant’s concentration known will vary based on the individual field circumstances, configuration technique adopted and equipment calibration. The level of ERA’s initial evaluation is where unrealistically high RQs are most common. When carrying out screening-level risk analysis, risk analysts frequently ignore the biological meaning of RQs as a benchmark multiple, which can lead to unrealistically high ERA results51,92.

Additionally, the inability of deterministic methodologies, such as TER and RQ, to be combined may prevent reliable comparisons between computed risk values in the initial risk analysis performed by various risk analysts. If different databases or models are used, the risk level could differ considerably. To address this issue, researchers and policymakers should work together to create integrated methodologies for assessing initial ecological risk. According to Wang et al.91. , ERA seeks to support decision-making aimed at effectively reducing risk levels. The inherent constraints of these initial ERA techniques may hurt how ERA results are used for risk management. However, they are helpful instruments that can provide an initial assessment of the type of pollution. Furthermore, the toxicity data employed in this study contributed to the uncertainty. The data on chronic and acute toxicity utilized for the ERA were obtained from laboratory-based studies. This introduced some level of uncertainty because it is assumed that the laboratory-observed terrestrial toxicity levels will also have negative impacts on organisms living in a natural terrestrial environment90. The RQ methodology is a point estimate approach; therefore, it cannot define a degree of risk or provide extensive information on the quality or extent of ecological risks. Thus, TER and RQ are valuable as screening tools that can assist in focusing on risk assessment. All the aforementioned factors indicated that the mathematical results obtained from the ERA in this and related research should be cautiously interpreted.

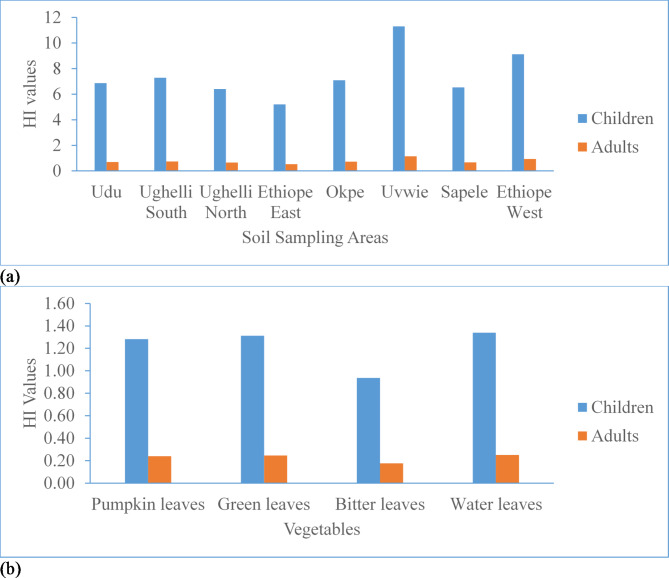

Health risk evaluation of OPPs in the soils and vegetables

The results of the non-carcinogenic risk computed as hazard index (HI) associated with the OPPs exposure to children and adult farmers through soil ingestion and dermal contacts in these agrarian soils are shown in Fig. 5 and Tables SM10 and SM11. The HQ from soil exposure for children and adults were in the order of HQIngestion > HQDermal. The HI values for children varied from 5.21 to 11.3 and 1.00 to 1.34 for soil and vegetables respectively. For adults, the HI ranged from 0.53 to 1.15 and 0.172 to 0.485 for soil and vegetables respectively. The HI for children exposures was ten times (for soil) and five times (for vegetables) higher than the HI for adults.

Fig. 5.

Hazard index of OPPs in (a) soil and (b) vegetables.

This implies that children are more susceptible to risk from OPPs exposure in the soils. This may be due to their high physical contact with soil, smaller body weight and pica behaviour9,80. The HI values for children were generally > 1. This implies that there is an adverse non-cancer risk for children from OPPs in the soils and vegetables. However, the HI values for adults were generally < 1 except for soil from the Ethiope East suggesting that there is no adverse non-cancer risk for adults from OPPs in the soils. The HI for soil regarding the locations followed the order: Uvwie > Ethiope West > Ughelli South > Okpe > Udu > Sapele > Ughelli North > Ethiope East while the input of each OPP compound to the HI was in the order of EPN > pirimiphos methyl > chloropyrifos > diazinone > quinalphos > chloropyrifos methyl. Whereas, for vegetables, the HI values were in the order of: bitter leaves < pumpkin leaves < green leaves < water leaves while the input of each OPPs congener to the HI was in the order of EPN > diazinone > quinalphos > pirimiphos methyl > chloropyrifos > chloropyrifos methyl. Based on the results of this study, policymakers should enforce routine monitoring of OPPs residues in soil and agricultural products to prevent, control and reduce environmental pollution. The farmers and the inhabitants of the study area should also be sensitized on the safe use and dangers of OPPs for pest control.

Uncertainty analysis of health risk

Various levels of uncertainty are present in all health risk assessment techniques. The concentrations of the pollutant assessed and the indistinctness of the exposed population are two major causes of uncertainty in assessing human exposure to a given pollutant90,93. Both of these had a significant impact on the outcome of the current study. Since the actual exposed population could not be studied, only hypothetical or assumed exposure scenarios were used to determine the health risk. As a result, there may be a lot of uncertainty in the outcomes. In addition, uncertainty regarding the dose-response of non-carcinogenic data also contributed.

The values of RfDs utilized in this study have uncertainty factors of magnitude 1–2 orders. The differences in the RfDs may be due to the method employed in assigning the RfDs and the size of the literature database90. The source of RfDs introduced considerable uncertainty. The multiple assumptions applied in the study, like the body weight, ingestion rate and lifetime elevated the uncertainties in the risk evaluation process. As such, the results obtained in this study are only a suggestion of the probable health risks related to potential exposure to OPPs in agricultural soil. These predicted risks may be an underestimation of the exact health risks as they only represent the risks associated with exposure to only six OPPs detected in this work that have RfDs. Therefore, the health risk may be higher than what is signified in this study if the other eight OPPs have RfDs and were included in the risk assessment.

Usually, the presumption of dose addition is a significant source of uncertainty when employing the HI. The fact that some toxicological investigations9,45 have shown proof of the combined effects of chronic exposure to OPPs in connection to adverse health consequences makes this less of an issue for OPPs than it is for many other classes of pollutants. Each of these investigations found that a dose-addition method was the most accurate at predicting health consequences, supporting the usage of the HI. The HQ and HI have the advantage of being simple to estimate and comprehend, but there are also uncertainties involved in using them. They offer just one number to designate health risks since only a single reference value is used. Describing the health risk of a population is an intricate process that should take into consideration the variance within the population65. Furthermore, the carcinogenic risk of OPPs could not be assessed due to the lack of oral slope factors for OPPs congeners which indeed is a limitation in this study.

Principal component analysis (PCA) of OPPs in the soils

The PCA result of the OPPs in the agrarian soils and vegetables is shown in Table SM12. Six components were extracted for soil and accounted for 85.316% of the data. Component 1 explained 16.579% with high loading of chlorpyrifos (0.963) and triphenyl phosphate (0.953); components 2 and 3 accounted for 15.860% and 15.800%. Component 1 has high loading of diazinone (0.951), isazophos (0.966) and moderate loading of chorpyriphos methyl (0.592). Component 4 explained 13.995% of the variance with high loading of phosalone (0.935), pyrazophos (0.703) and moderate loading of azinphos ethyl (0.609). Component 5 has a moderate loading of quinalphos (0.690) and high loading of (0.914) and accounted for 11.687% while component 6 which has a high loading of pirimiphos methyl (0.786) and fenitrothion (0.876) accounted for 11.395% of the variance. The presence of these OPPs together in a particular component suggests that they have similar source inputs, fate and behaviour.

Three components were extracted for the vegetables and accounted for 77.102% of the OPPs data set. Component 1 explained 33.669% of the total variance with high positive loading on isazophos (0.867), pirimiphos-methyl (0.902), pirimiphos-ethyl (0.867) and moderate positive loading on chloropyriphos-methyl (0.692), triphenyl phosphate (0.527), EPN (0.635) and pyrazophos (0.562). Component 2 accounted for 23.726% of the variance with high loading on fenitrothion (0.818), quilnaphos (0.704), chlorpyrifos (0.720) and moderate positive loading on phosalone (0.633). Component 3 explained 19.706% of the total variance with moderate positive loading on phosalone (0.610), pyrazophos (0.569), azinphos ethyl (0.681) and pyraclofos (0.626). The association of these OPPs congeners in a given component indicates a common source and characteristics. The PCA of the soil is somewhat similar to that of the vegetables. For instance, chlorpyrifos and triphenyl phosphate which were present together in component 1 in soil were also present together in component 2 in vegetables; diazinone, isazophos and chlorpyriphos methyl present in component 2 in soil were also seen together in component 1 in vegetables while phosalone, pyrazophos and azinphos ethyl present in component 4 in soil were also present together in component 3 in vegetables. This confirmed and agrees with the regression plot and thus indicates that the vegetables have the same OPPs source input as the soil which might be from OPPs application in agriculture in the study area.

Hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) of OPPs in the soils

HCA was used to categorize the variation in OPP concentrations in agrarian soils and vegetables. The rescaled distance cluster combination option and the average connectivity between groups were used for classification67,94. The HCA was performed using OPPs congeners (Figures SM8 and SM9) and sampling locations (Figures SM8 and SM9). For soil, the OPPs were divided into four groups (Figure SM8). Group 1 has pirimiphos methyl which has the highest average concentration in the soils. Group 2 contain diazinone and chlorpyriphos; group 3 contain pyrazophos, fenitrothion, isazophos and chlorpyriphos methyl while group 4 has phosalone, azinphos ethyl, EPN, quinalphos, pirimiphos ethyl, pyraclofos and triphenyl phosphate. The OPPs were divided into two categories for vegetables in Figure SM9. The first group contains diazinone, which has the highest average concentration in the vegetables, while the second group has the other OPP congeners, which have lower average concentrations.

The sampling locations were divided into eight subgroups for soil in Figure SM10. Location S26 in subgroup 1 had the highest concentration of pirimiphos methyl and location S25 in subgroup 2 had the highest concentration of fenitrothion. Subgroups 3, 4, 5 and 6 have locations S32, S23, S28 and S27 respectively. Subgroup 3 has the highest concentrations of chorpyrifos and triphenyl phosphate; subgroup 4 has the highest concentrations of diazinone and isazophos, subgroup 5 has the highest concentrations of quinalphos, azinphos ethyl and pyraclofos while subgroup 6 has highest concentrations of chorpyriphos methyl and pirimiphos ethyl. Locations S3, S8, S22, S24, S31 and S36 in Subgroup 7 have lower OPPs concentrations, while all other locations in Subgroup 8 have the lowest OPPs concentrations. The sampling locations were divided into five subgroups for vegetables in Figure SM11. Locations S4 and S8 in Subgroup 1 had the highest concentration of diazinone. Location AS1 in Subgroup 2 had the highest chloropyriphos-methyl content while S3 in Subgroup 3 had the highest fenitrothion concentration. Locations S10, S13 S15 and S27 in Subgroup 4 have lower OPPs concentrations, while locations while all other locations in Subgroup 5 have the lowest OPPs concentrations. Based on the summary of location clusters produced, there is no consistent pattern of OPPs contamination in soil and vegetables throughout the sampling locations. The distribution of OPPs in agrarian soils and vegetables may have resulted from numerous contamination sources, OPP transport behaviour, and soil attributes8,67,95.

Limitations

The limitations of this study were that authors could not perform matrix effect assay. Also, the authors were unable to provide the standard TIC as the chromatogram showing peak in standard could not be provided because authors could not obtain them from the laboratory where the analysis was done.

Conclusions

This study is the first to document a detailed analysis of OPPs occurrence, distribution and risks in the agricultural soils and vegetables of Delta Central District of Nigeria. It has provided very useful data for OPPs in soils and vegetables. From the study, fourteen OPPs were found in the soils and vegetables analyzed. Pirimiphos methyl and diazinone were the dominant OPPs congeners in the soils and vegetables respectively. The study revealed that OPPs were widely distributed in the soils and vegetables. The high detection rate of OPPs in the soils and vegetables is an indication of ubiquitous pollution of the soils and vegetables by OPPs as a result of intensive usage in agricultural activities. The OPPs in the soils were not influenced by the soil’s physicochemical properties. The results showed that the bioconcentration factors of the vegetables were < 1. The ERA revealed a high risk of OPPs to soil organisms in all these soils. The increasing order of OPPs toxicity to the soil organisms was chlorpyriphos < diazinone < fenitrothion < pirimiphos methyl. The health risk assessment evaluated as hazard index suggested there was an adverse non-carcinogenic risk for children but not for adults exposed to OPPs in these agricultural soils and vegetables with significant contribution from EPN. Since the levels of OPPs residue found in the soils and vegetables could pose health risks, it is hereby recommended that regulators enforce routine monitoring of OPPs in soil and agricultural products to reduce environmental pollution and also sensitize farmers on the safe use and dangers of OPPs for pest control.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This research was financially supported by Prince of Songkla University and Ministry of Higher Education, Science, Research and Innovation under the Reinventing University Project 2564-2565 (Grant Number REV65002).

Author contributions

GOT conceptualized the work; GOT and KEO curated the data and visualized the work; KT acquired funding; GOT and JNT carried out the investigation and formal analysis; KEO and IEA designed the methodology and provided the resources; JNT and KEO administered the project; IEA and KT supervised the work; KEO validated the work; GOT and JNT wrote the original draft of the manuscript; IEA and KT review & edit the manuscript.

Data availability

The data used and/or analyzed in this study are given in the work and supplementary materials.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics Declaration

The study was done in accordance with relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislations.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mohamed, A. O. & Paleologos, E. K. Chapter 2: sources and characteristics of wastes. In understanding soil, Water, and Pollutant Interaction and Transport. Fundamentals Geoenviron. Eng. 43–62 (2022).

- 2.Mdeni, N. L., Adeniji, A. O., Okoh, A. I. & Okoh, O. O. Analytical evaluation of carbamate and organophosphate pesticides in human and environmental matrices: a review. Molecules27, 618 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salem, D. M. S. A., El Sikaily, A. & El Nemr, A. Organochlorines and their risk in marine shellfish collected from the Mediterranean coast, Egypt. Egypt. J. Aquat. Res.40, 93–101 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hassaan, M. A. & El Nemr, A. Pesticides pollution: classifications, human health impact, extraction and treatment techniques. Egypt. J. Aquat. Res.46, 207–220 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Syafrudin, M. et al. A.M. Pesticides in drinking water—A review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18, 468 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yadav, I. C. & Devi, N. L. Pesticides classification and its impact on human and environment. In: (eds Kumar, A., Singhal, J. C., Techato, K. et al.) Environmental Science and Engineering Volume 6: Toxicology. Stadium Press LLC, USA. (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vale, A. & Lotti, M. Chapter 10 - Organophosphorus and Carbamate insecticide poisoning. Handb. Clin. Neurol.131, 149–168 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Montuori, P. et al. Estimates of Tiber River organophosphate pesticide loads to the Tyrrhenian Sea and ecological risk. Sci. Total Environ.559, 218–231 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pan, L. et al. Organophosphate pesticide in agricultural soils from the Yangtze River Delta of China: concentration, distribution, and risk assessment. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res.10.1007/s11356-016-7664-3 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sapbamrer, R. & Hongsibsong, S. Organophosphorus pesticide residues in vegetables from farms, markets, and a supermarket around Kwan Phayao Lake of northern Thailand. Arch. Environ. Con Tox. 67, 60–67 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Girard, J. Princípios Da química Ambiental (Rio de Janeiro, 2013).

- 12.Dar, M. A., Kaushik, G. & Chiu, J. F. V. Chapter 2 - Pollution status and biodegradation of organophosphate pesticides in the environment. In Abat. Environ. Pollutants: Trends Strategies2020, 25–66 (2020).

- 13.Maurya, P. K. & Malik, D. S. Bioaccumulation of xenobiotics compound of pesticides in riverine system and its control technique: a critical review. J. Ind. Pollut Control. 32, 580–594 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei, G. et al. Occurrence and risk assessment of currently used organophosphate pesticides in overlying water and surface sediments in Guangzhou urban waterways, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res.28, 48194–48206 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ore, O. T., Adeola, A. O., Bayode, A. A., Adedipe, D. T. & Nomngongo, P. N. Organophosphate pesticide residues in environmental and biological matrices: occurrence, distribution and potential remedial approaches. Environ. Chem. Ecotoxicol.5, 9–23 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernal-González, K. G. et al. Organophosphate pesticide-mediated immune response modulation in invertebrates and vertebrates. Int. J. Mol. Sci.24, 5360 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sánchez-Santed, F., Colomina, M. T. & Hernández, E. H. Organophosphate pesticide exposure and neurodegeneration. Cortex74, 417–426 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Babu, V., Unnikrishnan, P., Anu, G. & Nair, S. M. Distribution of organophosphorus pesticides in the bed sediments of a backwater system located in an agricultural watershed: influence of seasonal intrusion of seawater. Arch. Environ. Contam. Tox. 60, 597–609 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flaherty, R. J. et al. Cyclodextrins as complexation and extraction agents for pesticides from contaminated soil. Chemosphere91, 912–920 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mumtaz, M. et al. Human health risk assessment, congener specific analysis and spatial distribution pattern of organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) through rice crop from selected districts of Punjab Province, Pakistan. Sci. Total Environ.511, 354–361 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sruthi, S. N., Shyleshchandran, M. S., Mathew, S. P. & Ramasamy, E. V. Contamination from organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) in agricultural soils of Kuttanad agroecosystem in India and related potential health risk. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res.10.1007/s11356-016-7834-3 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calderon-Preciado, D., Jimenez-Cartagena, C., Matamoros, V. & Bayona, J. M. Screening of 47 organic microcontaminants in agricultural irrigation waters and their soil loading. Water Res.45, 221–231 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cembranel, A. S. et al. Residue analysis of organochlorine and organophosphorus pesticides in urban lake sediments. J. Brazilian Assoc. Agric. Eng.37, 1254–1267 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tesi, J. N., Tesi, G. O., Ossai, J. C. & Agbozu, I. E. Organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) in agricultural soils of southern Nigeria: spatial distribution, source identification, ecotoxicological and human health risks assessment. Environ. Forensics. 10.1080/15275922.2020.1850570 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geronimo, E. et al. Presence of pesticides in surface water from four sub-basins in Argentina. Chemosphere107, 423–431 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lupi, L., Bedmar, F., Wunderlin, D. A. & Miglioranza K.S.B. Organochlorine pesticides in agricultural soils and associated biota. Environ. Earth Sci.75, 519 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tesi, G. O., Iniaghe, P. O., Lari, B., Obi-Iyeke, G. & Ossai, J. C. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in leafy vegetables consumed in southern Nigeria: concentration, risk assessment and source apportionment. Environ. Monit. Assess.193 (7), 443. 10.1007/s10661-021-09217-5 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adetunde, O. T. et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon in vegetables grown on contaminated soils in a sub-saharan tropical environment – Lagos, Nigeria. Polycycl. Aromat. Comp.10.1080/10406638.2018.1517807 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stadlmayr, B., Charrondiere, U. R. & Burlingame, B. Development of a regional food composition table for West Africa. Food Chem.140, 443–446 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thompson, D. & Agbugba, I. K. Marketing of tropical vegetable in Aba area of Abia state Nigeria. J. Agric. Econ. Dev.2, 272–279 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adeleye, A. O., Sosan, M. B. & Oyekunle, A. O. Dietary exposure assessment of organochlorine pesticides in two commonly grown leafy vegetables in South-western Nigeria. Heliyon5, e01895. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01895 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bolor, V. K., Boadi, N. O., Borquaye, L. S. & Aful, S. Human risk assessment of organochlorine pesticide residues in vegetables from Kumasi, Ghana. J. Chem.10.1155/2018/3269065 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 33.FAO. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Promotion of Fruit and Vegetables for Health Report of the Pacific regional workshop, Rome. (2015).

- 34.FosuMensah, B. Y., Okoffo, E. D., Darko, G. & Gordon, C. Organophosphorus pesticide residues in soils and drinking water sources from cocoa producing areas in Ghana. Environ. Syst. Res.5, 10. 10.1186/s40068-016-0063-4 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mahugija, J. A., Khamis, F. A. & Lugwisha, E. H. Determination of levels of organochlorine, organophosphorus, and pyrethroid pesticide residues in vegetables from markets in Dar Es Salaam by GC-MS. Int. J. Anal. Chem.2017 (4676724). 10.1155/2017/4676724 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Ahoudi, H. et al. Assessment of pesticides residues contents in the vegetables cultivated in urban area of Lome (southern Togo) and their risks on public health and the environment, Togo. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci.12 (5), 2172–2185 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bai, Y., Zhou, L. & Wang, J. Organophosphorus pesticide residues in market foods in Shaanxi area, China. Food Chem.98 (2), 240–242 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sudarsono, J., Rahardjo, S. S. & Kisrini, S. S. Organophosphate pesticide residue in fruits and vegetables. KEMAS14 (2), 172–177 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jara, E. A. & Winter, C. K. Safety levels for organophosphate pesticide residues on fruits, vegetables, and nuts. Int. J. Food Contam.6 (6). 10.1186/s40550-019-0076-7 (2019).

- 40.Sapahin, H. A., Makahleh, A. & Saad, B. Determination of organophosphorus pesticide residues in vegetables using solid phase micro-extraction coupled with gas chromatography–flame photometric detector. Arab. J. Chem.12, 1934–1944 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bhandari, G., Atreya, K., Scheepers, P. T. J. & Geissen, V. Concentration and distribution of pesticide residues in soil: non-dietary human health risk assessment. Chemosphere253, 126594 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hu, D. et al. Pesticide residues in vegetables in four regions of Jilin Province. Int. J. Food Prop.23 (1), 1150–1157 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bhandari, G., Atreya, K., Vašíčková, J., Yang, X. & Geissen, V. Ecological risk assessment of pesticide residues in soils from vegetable production areas: a case study in S-Nepal. Sci. Total Environ.788, 147921 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ssemugabo, C., Bradman, A., Ssempebwa, J. C., Sill´e, F. & Guwatudde, D. Pesticide residues in fresh fruit and vegetables from farm to fork in the Kampala metropolitan area, Uganda. J. Environ. Health Insights. 16 (1), 1–17. 10.1177/11786302221111866 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]