Abstract

This phase II, randomized, double blinded, multi-center study aims to explore whether intravenous edaravone dexborneol (ED) could improve clinical outcomes in patients with anterior circulation stroke with successful endovascular reperfusion (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04667637). Eligible patients were randomly (1:1) assigned into ED, which received intravenous ED (37.5 mg, 2/day, for 12 days) or control group, which received placebo. The primary endpoint was favorable functional outcome (a modified Rankin Scale [mRS] of 0–2 at 90 days). Two hundred patients were enrolled, including 97 in ED group and 103 in control group. The proportion of patients with 90-day mRS (0–2) was 58.7% (54/92) in ED group and 52.1% (49/94) in control group (unadjusted odds ratio 1.37, [95% CI 0.76-2.44], P = 0.29). This work suggests that intravenous ED is safe, but do not statistically improve 90-day functional outcomes in patients with anterior circulation stroke with successful endovascular reperfusion.

Subject terms: Stroke, Randomized controlled trials

Endovascular thrombectomy (EVT) achieves high recanalization rates in acute stroke, but many patients still experience poor outcomes. Here, the authors show that intravenous edaravone dexborneol (ED) is safe and reduces early hemorrhage but does not significantly improve 90-day functional outcomes in stroke patients after EVT.

Introduction

Acute ischemic stroke (AIS) is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide1. Based on several randomized controlled trials, endovascular treatment (EVT) has been recommended as the most effective therapy for anterior circulation AIS patients with large vessel occlusion (LVO) by current guidelines2,3. However, despite the high rate of recanalization after EVT, 46% to 51% of patients with successful reperfusion achieve functional independence at 90 days4,5. Improving outcomes in patients who achieve reperfusion without regaining functional independence is an unmet need5. Given the involvement of the inflammatory response and oxidative stress in acute stroke, anti-inflammation and anti-oxidative pathways have been attractive targets to improve the outcomes of patients with LVO-AIS after EVT6,7.

To date, no drug has been shown to be effective in AIS although many were found to be neuroprotective in animal stroke models8. Subgroup analysis of the ESCAPE-NA1 trial showed that nerinetide may improve clinical outcome in AIS-LVO patients who do not receive alteplase, which offers hope for neuroprotection in AIS9. Furthermore, recent BAST (Butylphthalide for Acute Ischemic Stroke Patients Receiving Intravenous Thrombolysis or Endovascular Treatment) provided the evidence for the cerebroprotective effect of Butylphthalide in patients who received intravenous thrombolysis or EVT10. These studies further support the cerebroprotective strategy to improve reperfusion injury in patients who received reperfusion treatments11–13. Reperfusion injury may result in clinically ineffective reperfusion after EVT by generation of harmful free radicals such as the superoxide, hydroxyl, and peroxynitrite radicals11, which may lead to apoptosis or programmed cell death14, disruption of neurovascular unit15, endothelial injury16, and aggravation of inflammation and immune dysregulation12,17. Edaravone dexborneol (ED), a compound composed of edaravone and dexborneol with both antioxidative and anti-inflammatory properties, was found to exert multiple neuroprotective effects in pre-clinical studies9,18. Edaravone has been recommended for AIS therapy with the ability of scavenging free radical, preventing neuronal and endothelial cell injury by excessive Ca2+ influx reactive oxygen species19–21. Dexborneol was reported to exert neuroprotective effects through inhibiting nitric oxide (NO) and NO synthase pathways, reducing ROS generation, restraining inflammatory process and caspase-related apoptosis22,23. Furthermore, the TASTE (Treatment of Acute Ischemic Stroke with Edaravone Dexborneol) trial showed that a 14-day infusion of ED produced better 90-day functional outcomes (mRS 0–1) compared to the edaravone group in AIS patients who did not received thrombolysis or EVT presenting within 48 h of symptom onset24. The recent TASTE–SL (TASTE sublingual) phase 3 trial showed in patients with AIS presenting within 48 h and not candidate for EVT, patients who received sublingual ED had higher rates of 90-day good functional outcome (mRS 0–1) compared to those who received placebo25.

Given the multiple cerebroprotective effects of ED, we hypothesized that intravenous ED could improve clinical outcomes in anterior circulation LVO-AIS patients who achieve successful recanalization after EVT.

Results

Trial population

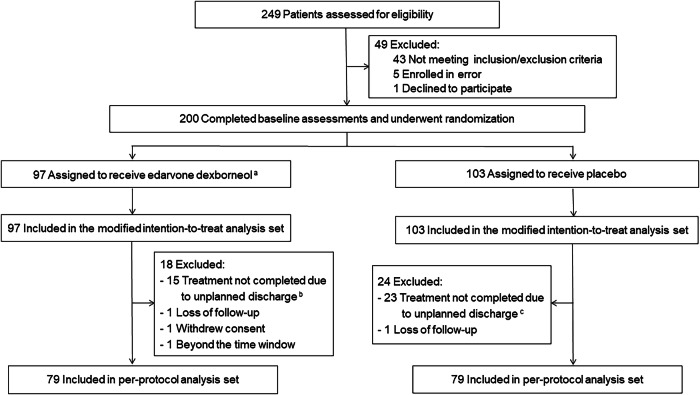

Between February 23, 2021, and July 9, 2022, 200 patients were enrolled and randomly assigned to the ED group (97 patients) or control group (103 patients), and were included in the modified intention-to-treat (mITT) population (Fig. 1). A total of 42 patients (21.0%) were excluded were excluded from the per-protocol population (38 due to incomplete treatment, 2 due to loss of follow-up, 1 withdrew consent, 1 treated beyond 9 h of symptom onset) leading to 158 patients who completed the study according to trial protocol (79 [81.4%] in the ED group and 79 [76.7%] in the control group). Reasons for incomplete procedure are shown in Fig. 1. The trial was completed in October 2022.

Fig. 1. Screening, randomization, and follow-up of the patients.

aAfter randomization, 101 patients assigned into ED group and 103 patients assigned into Control group. In ED group, 4 patients were excluded due to decline to participate (n = 1) and error enrollment after randomization (n = 3). bIncluded giving up treatment due to clinical deterioration (n = 6) and economic reasons (n = 6), and transferring to other hospitals (n = 3). cincluded giving up treatment due to clinical deterioration (n = 8) and economic reasons (n = 7), and transferring to other hospitals (n = 8).

The baseline characteristics were well balanced between the two groups in mITT analysis (Table 1) and per-protocol analysis (Supplementary Table 1 in Supplementary information). The median NIHSS score at baseline was 14 in both the ED group and the control group. The median time from onset to recanalization was 383 min in the ED group and 386 min in the control group, respectively. A total of 24 and 28 patients received intravenous alteplase before EVT in ED group (24.7%) and control group (27.2%), respectively. All patients were treated with mechanical thrombectomy under local anesthesia.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics in intention-to-treat analysis set

| Characteristics | ED group (n = 97) | Control group (n = 103) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), years | 63.61 (10.75) | 63.31 (10.84) |

| Gender, No. (%) | ||

| Male | 71 (73.2) | 74 (71.8) |

| Female | 26 (26.8) | 29 (28.2) |

| Weight, mean (SD), kga | 71.05 (10.81) | 71.12 (12.32) |

| BMI, mean (SD), kg/m2a | 24.64 (2.81) | 25.12 (3.77) |

| Medical History, n (%)b | ||

| Previous ischemic stroke | 18 (18.6) | 21 (20.4) |

| Hypertension | 43 (44.3) | 56 (54.4) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 2 (2.1) | 1 (1.0) |

| Diabetes | 18 (18.6) | 17 (16.5) |

| Cardiac disease | 14 (14.4) | 18 (17.5) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 24 (24.7) | 19 (18.4) |

| Medications, n (%) | ||

| Antihypertensive drugs | 31 (32.0) | 30 (29.1) |

| Statin or other lipid-lowering drug | 7 (7.2) | 4 (3.9) |

| Aspirin or other antiplatelet drug | 7 (7.2) | 9 (8.7) |

| Anticoagulation drug | 10 (10.3) | 7 (6.8) |

| Current smoker, No./total (%) | 37/96 (38.5) | 30/103 (29.1) |

| Current drinker, No./total (%)c | 20/97 (20.6) | 19/102 (18.6) |

| Baseline breath, median (IQR), /min | 18 (18−18) | 18 (18−18) |

| Baseline HR, median (IQR), /min | 70 (61–86) | 73 (61–82) |

| Blood pressure at baseline, mean (SD), mm Hg | ||

| Systolic | 141.8 (23.) | 143.1 (25.1) |

| Diastolic | 83.2 (14.0) | 82.9 (15.6) |

| Baseline blood glucose, median (IQR)d | 7.30 (6.07–8.64) | 7.37 (6.12–8.83) |

| Baseline ASPECTS score, median (IQR)e | 8 (7–9) | 8 (7–9) |

| Baseline NIHSS score, median (IQR)f | 14 (10−17) | 14 (11−18) |

| Pre-stroke score on the modified Rankin Scale (mRS), n (%)g | ||

| mRS 0 | 89 (91.8) | 90 (87.4) |

| mRS 1 | 8 (8.2) | 13 (12.6) |

| Median duration, median (IQR), min | ||

| Onset to punctureh | 312 (242–386) | 319 (246–395) |

| Onset to recanalization | 383 (282–458) | 386 (324–460) |

| Groin puncture to recanalizationh | 56 (40–87) | 65 (44–99) |

| Onset to randomization | 421 (317–499) | 422 (360–500) |

| Cause of large-vessel occlusion, n (%) | ||

| Intracranial atherosclerosis | 32 (33.0) | 30 (29.1) |

| Extracranial atherosclerosis | 23 (23.7) | 31 (30.1) |

| Cardioembolism | 36 (37.1) | 36 (35.0) |

| Other cause | 6 (6.2) | 6 (5.8) |

| Intravenous alteplase, n (%)i | 24 (24.7) | 28 (27.2) |

| mTICI score at the end of the procedure, n (%) | ||

| 2b | 15 (15.5) | 24 (23.3) |

| 2c | 2 (2.1) | 5 (4.9) |

| 3 | 80 (82.5) | 74 (71.8) |

| Location of responsible vessel, n (%) | ||

| MCA-M1 | 47 (48.5) | 51 (49.5) |

| MCA-M2 | 3 (3.1) | 2 (1.9) |

| ICA | 41 (42.3) | 31 (32.0) |

| MCA-M1 + ICA | 16 (16.5) | 9 (8.7) |

| Cerebral collateral circulation grade, n (%)j | ||

| 0 | 21 (24.1) | 27 (27.8) |

| 1 | 19 (21.8) | 15 (15.5) |

| 2 | 25 (28.7) | 24 (24.7) |

| 3 | 13 (14.9) | 20 (20.6) |

| 4 | 9 (10.3) | 11 (11.3) |

| Recanalization during day time, n (%)k | 71 (73.2) | 77 (74.8) |

Data are No. (%) or No./total (%), mean (SD), or median (IQR).

ED edaravone dexborneol, BMI body mass index, HR heart rate, NIHSS National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale, ASPECTS Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score, mTICI modified thrombolysis in cerebral infarction, ICA internal carotid artery, MCA middle cerebral artery.

aData missing for 3 participants for weight and BMI.

bComorbidities based on family or patient report.

cCurrently drinks alcohol means consuming alcohol at least once a week within 1 year prior to the onset of the disease.

dData missing for 5 participants for blood-glucose at baseline.

eASPECTS scores determine extent of ischemic tissue based on CT imaging. Scores range from 0 to 10 with higher scores indicating less infarct volume. Data missing for 5 participants for ASPECTS score at baseline.

fScores on National Institutes of Health Scale (NIHSS) range from 0 to 42, with higher scores indicating more severe neurologic deficit; A mean NIHSS of 8–9 means moderate neurological deficit.

gScores on the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) of functional disability range from 0 (no symptoms) to 6 (death).

hData missing for 2 participants for time from onset to puncture and groin puncture to recanalization.

iDefined as half or more than standard alteplase dose (0.9 mg/kg).

jThe ASITN/SIR collateral circulation assessment system based on DSA examination. Grades range from 0 to 4 with higher grades indicating better collateral circulation. Grade 0−1 indicates poor collateral circulation; Grade 2 indicates moderate collateral circulation; and Grade 3–4 indicates better collateral circulation. Data missing for 10 participants for cerebral collateral circulation grade.

kDay time referred to the time from 7 AM to 10 PM31.

Primary outcome

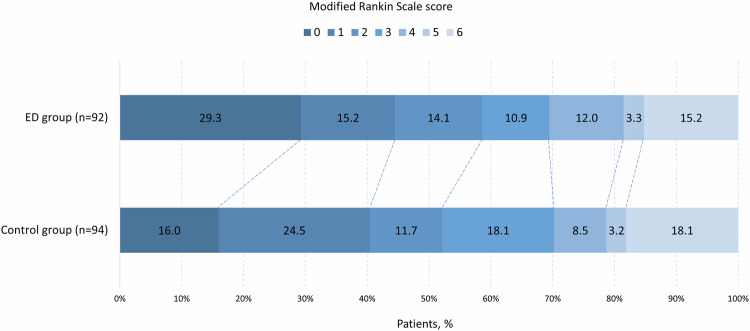

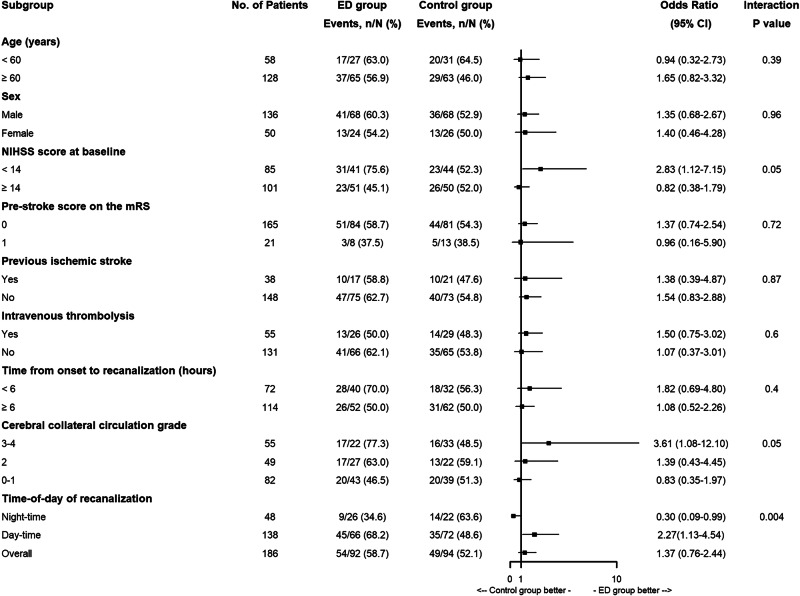

For the primary outcome, the proportion of patients with mRS 0–2 at 90 days was 58.7% (54/92) in the ED group and 52.1% (49/94) in the control group in the mITT population (unadjusted odds ratio, OR, 1.37, 95% CI 0.76–2.44; P = 0.29; adjusted OR, aOR, 1.36, 95% CI 0.71–2.58; P = 0.35; Table 2, Fig. 2). Similar results were observed in the PP analysis (unadjusted OR 1.39, 95% CI, 0.73–2.66; P = 0.32; aOR 1.30, 95% CI, 0.64–2.67; P = 0.47; Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 2 in Supplementary information). The exploratory analyses for primary outcome by prespecified subgroups in the mITT and the PP set are shown in Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 2 (Supplementary information). Similar OR results were observed in the last observation carried forward, worst-case scenario, and best-case scenario sensitivity analyses (Supplementary Table 3 in Supplementary information). A significant interaction between the time-of-day of recanalization and treatment with regard to the primary outcome was observed (Fig. 3, P = 0.004; Supplementary Fig. 2, P = 0.001), suggesting the benefit of ED treatment during day-time of recanalization, compared with night-time of recanalization. Exploratory Tipping point analysis indicated that the proportion of patients with mRS (0–2) at 90 days was 60.8% (54/97) in the ED group and 56.3% (58/103) in the control group (unadjusted odds ratio, OR, 0.97, 95% CI 0.56–1.7; P = 0.93; adjusted OR 0.88, 95% CI 0.48–1.61; P = 0.68; Supplementary Fig. 3 in Supplementary information).

Table 2.

Primary and secondary outcomes in the modified intention-to-treat analysis set

| Outcome | ED Group (n = 97) | Control Group (n = 103) | Treatment Effect Metric | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment Difference (95% CI) | P Value | Treatment Difference (95% CI) | P Value | ||||

| Primary outcome | |||||||

| mRS score 0–2 at 90 ± 7 days, No. (%)b | 54/92 (58.7) | 49/94 (52.1) | OR | 1.37 (0.76–2.44) | 0.29 | 1.36 (0.71–2.58) | 0.35 |

| Secondary outcomes | |||||||

| mRS score 0−1 at 90 ± 7 days, No. (%)b | 41/92 (44.6) | 38/94 (40.4) | OR | 1.19 (0.66–2.12) | 0.57 | 1.11 (0.59–2.09) | 0.74 |

| mRS score distribution at 90 ± 7 daysb | OR c | 0.74 (0.44−1.22) | 0.24 | 0.79 (0.47–1.34) | 0.38 | ||

| Change in NIHSS score from baseline, GM (GMSD)d | |||||||

| at 24 h | 0.651 (1.85) | 0.709 (1.81) | GMRe | −0.02 (−0.11 to 0.08) | 0.70 | 0.00 (−0.09 to 0.09) | 0.97 |

| at 48 h | 0.508 (2.05) | 0.598 (1.89) | GMRe | −0.07 (−0.16 to 0.01) | 0.09 | −0.06 (−0.14 to 0.03) | 0.20 |

| at 12 ± 2 days | 0.297 (2.56) | 0.384 (2.24) | GMRe | −0.11 (−0.23 to 0.00) | 0.06 | -0.09 (−0.20 to 0.03) | 0.14 |

| Infarct volume at 1 week, GM (GMSD)f | 1.170 (2.00) | 1.291 (1.58) | GMRe | 0.12 (−0.07 to 0.31) | 0.22 | 0.09 (−0.09 to 0.26) | 0.34 |

| All-cause mortality within 90 ± 7 days, No. (%) | 14 (14.4) | 17 (16.5) | HRg | 0.84 (0.41−1.70) | 0.62 | 0.95 (0.45−1.99) | 0.89 |

ED edaravone dexborneol, CI confidence interval, mRS modified Rankin Scale, OR odds ratio, NIHSS National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale, GM geometric mean, GMSD geometric mean standard deviation, GMR geometric mean ratio, HR hazard ratio.

aAdjusted for key prognostic covariates (age, sex, pre-stroke score on the modified Rankin Scale, NIHSS score at baseline, previous ischemic stroke, time from onset to recanalization, cerebral collateral circulation grade, number of thrombectomy device passes, and Intravenous thrombolysis).

bmRS scores range from 0 to 6: 0, no symptoms, 1 = symptoms without clinically significant disability, 2 = slight disability, 3 = moderate disability, 4 = moderately severe disability, 5 = severe disability; and 6 = death. Data missing for 14 participants for mRS score at 90 ± 7 days.

cCalculated with ordinal regression analysis.

dNIHSS scores range 0–42, with higher scores indicating greater stroke severity. The log (NIHSS + 1) was analyzed using a geometric mean ratio by generalized linear model. Data missing for 10 participants for NIHSS score at 24 h, 23 participants at 48 h, and 34 participants at 12 ± 2 days.

eGMR was used because normality assumption was assessed graphically and residual histogram showed serious violation of normality assumption.

fDetermined by brain CT or MRI. The log (Infarct volume +1) was analyzed using a geometric mean by generalized linear model. Data missing for 11 participants for infarct volume at 1 week. Data eliminating for 1 participant due to excessive deviation.

gCalculated with Cox regression model.

Fig. 2. Distribution of modified Rankin Scale Scores at 90 days in the intention-to-treatment set.

Scores range from 0 to 6 (0 = no symptoms, 1 = symptoms without clinically significant disability, 2 = slight disability, 3 = moderate disability, 4 = moderately severe disability, 5 = severe disability, and 6 = death). The odds ratio was 0.66(95% CI, 0.40−1.08), and the P value was 0.10; the adjusted odds ratio was 0.79 (95% CI, 0.48−1.30), and the P value was 0.35. Percentages may not total 100 because of rounding. Abbreviations: ED edaravone dexborneol. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Fig. 3. ED treatment effect by prespecified subgroups.

The primary outcome was the proportion of patients with mRS (0–2) at 90 ± 7 days. For subcategories, black squares represent point estimates (with the area of the square proportional to the number of events) and horizontal lines represent the 95% CI. NIHSS scores range from 0 to 42, with higher scores indicating more severe neurological deficits. For the NIHSS score, subgroups were dichotomized according to the median value. Abbreviations: ED edaravone dexborneol, mRS modified Rankin scale, NIHSS National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Secondary outcomes

For the secondary outcomes, no significant differences between the two groups were observed in both the unadjusted and the adjusted mITT sets, including the proportion of patients with mRS 0–1 at 90 days; an ordinal shift of the mRS scores at 90 days; change in NIHSS score compared with baseline at 24 h, 48 h and 12 ± 2 days; infarct volume at 1 week; occurrence of all-cause mortality at 90 ± 7 days. However, a numerically higher probability of mRS 0–1 (44.6% vs 40.4%) and numerically smaller median infarct volume at 1 week (16.00 vs 23.49 ml) were observed in ED vs control group (Table 2). The same results were found in the PP analysis (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 2 in Supplementary information).

Safety outcomes

As an exploratory analysis, no significant differences in the safety outcomes were observed in both the unadjusted and adjusted analysis, including sICH, PH-2, HI-1, HI-2, and SAE in the mITT (Table 3), and PP population (Supplementary Table 2 in Supplementary information). A significant decrease in PH-1 at 48 h was observed in the ED vs control group (unadjusted OR 0.27, 95% CI, 0.07–1.00; P = 0.05; aOR 0.21, 95% CI, 0.05–0.89; P = 0.03; Table 3), and PP analysis (Supplementary Table 2 in Supplementary information). In subgroup analysis, the point estimates favored patients with lower baseline NIHSS and patients who presented in the early 0–6 h window; there was no treatment interaction in patients who received IVT (Fig. 3)

Table 3.

Safety Outcomes in the Safety Population

| Outcome | ED Group (n = 97)a | Control Group (n = 103)a | Treatment Effect Metric | Unadjusted | Adjustedb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment Difference (95% CI) | P Value | Treatment Difference (95% CI) | P Value | ||||

| sICH at 48 h, No. (%)c | 5/94 (5.3) | 11/101 (10.9) | OR | 0.46 (0.15–1.37) | 0.17 | 0.39 (0.11 to 1.35) | 0.14 |

| Intracerebral hemorrhage at 48 h, No. (%)c | |||||||

| PH−1 | 3/94 (3.2) | 11/101 (10.9) | OR | 0.27 (0.07−1.00) | 0.05 | 0.21 (0.05–0.89) | 0.03 |

| PH-2 | 5/94 (5.3) | 4/101 (4.0) | OR | 1.36 (0.36–5.23) | 0.65 | 1.08 (0.25–4.73) | 0.92 |

| HI−1 | 3/94 (3.2) | 1/101 (1.0) | OR | 3.30 (0.34–32.26) | 0.31 | 4.01 (0.21–76.58) | 0.36 |

| HI-2 | 4/94 (4.3) | 13/101 (12.9) | OR | 0.30 (0.09–0.96) | 0.04 | 0.27 (0.08–0.95) | 0.04 |

| SAE within 90 days, No. (%)d | 21 (21.6) | 30 (29.1) | HRe | 0.75 (0.43−1.30) | 0.30 | 0.90 (0.50−1.60) | 0.72 |

sICH symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage, PH parenchymal hemorrhage, HI hemorrhagic infarct, SAE serious adverse events.

aFive patients lacked safety outcomes due to discharging within 48 h after receiving the treatment (3 in ED group and 2 in Control group).

bAdjusted for key prognostic covariates (age, sex, pre-stroke score on the modified Rankin Scale, NIHSS score at baseline, previous ischemic stroke, time from onset to recanalization, cerebral collateral circulation grade, number of thrombectomy device passes, and intravenous thrombolysis).

cDefined according to European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study (ECASS).

dSAE included parenchymal hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage, cerebral hernia, respiratory failure, acute ischemic stroke, cerebral edema, sudden cardiac death, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, liver dysfunction, etc. Two patients occurred SAE presented with liver dysfunction possibly related to ED.

eCalculated with Cox regression model.

Discussion

This phase 2, investigator-initiated, multicenter, randomized trial investigated the effect of intravenous ED administered within 9 h of symptom onset in anterior circulation LVO-AIS patients who achieved successful recanalization after EVT. This trial showed that intravenous ED did not improve clinical outcome, although showed a numerically higher probability of favorable outcome and numerically lower risk of intracranial hemorrhage, compared with the placebo.

Many pharmacologic agents have been demonstrated to be effective in animal stroke studies, but, to date, they failed in phase II/III clinical trials6,7,26. A cerebroprotective strategy targeted to patients who achieve successful recanalization may offer promising results12,13. Another reason of translational failure may be attributed to single mechanism target of the tested drugs given the complex processes underlying brain ischemia including their interaction and overlap with each other6,7,27. Therefore, the ideal candidate should be a drug with multiple protective targets on the neurovascular unit covering the neuronal, glial and vascular compartment27. INSIST-ED was designed with these considerations in mind. First, intravenous ED was given to AIS-LVO patients with successful reperfusion after EVT. Reperfusion injury may lead to clinically ine ffective reperfusion after EVT due to multiple mechanisms including generation of harmful free radicals, aggravation of inflammation and immune dysregulation. Second, ED harbors multiple protective mechanisms involving anti-oxidative stress, anti-excitotoxicity, anti-neuroinflammation, anti-neuron apoptosis, and microglial pyroptosis, which can cover multiple targets such as the neuronal, glial and endothelial cells18,23.

In the current study, no difference in functional outcome was observed, but an absolute 6.6% increase in favorable outcome in ED vs control was found, which was comparable to the effect size observed in the subgroup of patients who received no alteplase in ESCAPE-NA19. The higher probability of favorable outcome was in parallel with the decrease of median 7.49 ml of infarct volume in the ED vs control group. Furthermore, a 50% decrease of sICH was observed in the ED vs control group, which may suggest a potential safety profile of ED. These findings seem plausible given the design of INSIST-ED: ED can reach ischemic brain tissue after successful reperfusion to exert its multiple cerebroprotective effects. It is worthy to note that ED treatment may be favored if recanalization occurs during day-time. The results of our phase II trial may inform the sample size and clinical design of a future phase III trial. Collectively, these results suggest ED may be a promising candidate as a cerebroprotective drug, which warrants further investigation in larger trials.

Limitations

The present study had limitations. As a phase II study, the small sample size renders our findings inconclusive. The failure to detect a difference in the primary outcome between the two groups can be attributed to the absence of sample size calculation due to the lack of reference data from previous trials given this is a phase II study. Another limitation was that some serum biomarkers of NO synthase pathways, ROS generation, inflammatory factors, and oxidative stress were not measured, which can be helpful to understand the cerebroprotective effect of ED. In addition, shorter time from groin puncture to reperfusion occurred in the ED group, however there was balanced time from onset to recanalization between groups, which was set as covariate adjustment given its importance over time from groin puncture to reperfusion in clinical outcome as well as their collinearity. Furthermore, given that some clinically imbalance baseline characteristics including hypertension and mTICI score may influence the results, we further adjusted them and found that the results were consistent. Finally, the treatment length in this study was 12 ± 2 days, which was obviously longer than previous studies, for example, the DEFUSE 3 trial (6.5 days of median length)28. This treatment length time was chosen based on two considerations: (1) the practical length of hospital stay in this population was usually 10–14 days in China10,29; (2) TASTE trial suggested that a14-day infusion of ED improved clinical outcome in AIS24. Whether or not a shorter course of ED could be as effective in improving clinical outcomes is unknown.

In conclusion, the results of this study indicates that among anterior circulation LVO-AIS patients with successful recanalization after EVT, intravenous ED administration was safe and feasible, but did not improve 90-day good functional outcomes. A numerically higher probability of favorable outcome and numerically lower risk of sICH may suggest ED as a promising cerebroprotective drug.

Methods

Study design and patients

The INSIST-ED study was a phase 2, randomized, double blinded, placebo-controlled, multi-center trial conducted at 18 centers (Study Protocol) in China. The trial was approved by the ethics committees of the General Hospital of Northern Theatre Command and other participating centers. All patients or legally acceptable surrogates provided written informed consent before inclusion into the trial. An independent data monitoring committee (listed in Clinical Trial information) monitored the progress of the trial every 6 months. An independent clinical research organization (Nanjing Service Pharmaceutical Technology Co.) monitored the trial for quality control. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was registered with https://www.clinicaltrials.gov (unique identifier: NCT04667637).

Eligible patients were adults aged 18–80 years with anterior circulation LVO-AIS and who achieved sufficient recanalization (modified Thrombolysis In Cerebral Infarction [mTICI] 2b-3) within 9 h of stroke onset after EVT (baseline NIHSS score ≥ 6, range from 0 to 42, with higher scores indicating greater stroke severity), who had been functioning independently in the community (modified Rankin Scale [mRS] score ≤1; range from 0 [no symptoms] to 6 [death]) before the index stroke. Key exclusion criteria were as follows: if a patient was older than 80 years given potentially increased risk of renal dysfunction and death in this population; had hemorrhagic transformation (PH2) as indicated by NCCT performed immediately after the procedure; had severe hepatic or renal dysfunction, had severe uncontrolled hypertension (systolic blood pressure over 200 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure over 110 mmHg); had malignant tumor with estimated lifetime less than 3 months or pregnancy. A full list of inclusion and exclusion criteria is available in the Study Protocol.

Randomization and masking

In the trial, patients were randomly assigned into the experiment or control group using a randomization (1:1) method with block randomization (block size: 4) through a computer-generated sequence that was centrally administered via a password-protected, web-based program at https://www.91trial.com (ShangHai Ashermed healthcare communications co., Ltd). The investigators were blinded to treatment allocation due to the double blinded design.

Procedures

Patients were randomly assigned to the ED group (intravenous ED [37.5 mg, dissolved in 100 ml saline] twice a day for 12 days), or control group (intravenous placebo [dissolved in 100 ml saline] twice a day for 12 days). Intravenous ED or placebo was administered within 60 min after successful recanalization. Neurological status, measured with the NIHSS, was assessed at baseline, 24 h, 48 h, 7 days, and 12 days after randomization. Demographic and clinical details were obtained at randomization. Follow-up data were collected at 24 h, 48 h, 7 days, 12 days (or at hospital discharge if earlier), and 90 days after randomization. Remote and on-site quality control monitoring and data verification were performed throughout the study. All patients received standard medical management according to national stroke guidelines2,3.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint was favorable functional outcome, defined as a mRS of 0–2 at 90 days after randomization.

The secondary endpoints were excellent functional outcome (mRS 0–1) at 90 days after randomization; an ordinal shift of the full range of mRS scores at 90 days; change in NIHSS score compared with baseline at 24 h, 48 h and 12 ± 2 days; infarct volume at 1 week; all-cause mortality at 90 ± 7 days.

The safety outcomes included symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage (sICH) within 48 h, defined as an increase in the NIHSS score of ≥4 points as a result of the intracranial hemorrhage30, parenchymal hemorrhage at 48 h30, and serious adverse events (SAE).

Statistical analysis

Given that this was a phase 2 study, no formal sample size calculation was performed due to the absence of relevant data availability from previous trials. A total of 200 patients (100 patients per group) was set based on the recommendation of the Steering Committee. According to our recent unpublished data, the proportion of expected favorable functional outcome (mRS 0–2) at 90 days in control group is estimated to be about 50%. Using power = 80% and α = 0.05 to carry out the two-side test, the 200 size will test the superiority hypothesis with about 19% difference, namely the proportion of expected favorable functional outcome at 90 days is about 69%.

Statistical analyses were performed on the mITT analysis principle. All data were analyzed with SPSS 26 Software or R software. The mean ± standard deviation (SD) was used if continuous data were normally distributed; the median and interquartile range (IQR) were used if continuous data were non-normally distributed. Categorical data were expressed as a number (percentage). Differences of the primary endpoint and secondary endpoints such as mRS (0–1) at 90 days, proportion of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage at 48 h, and proportion of intraparenchymal hemorrhage at 48 h were compared using binary logistic regression and adjusted a priori by key prognostic covariates (age, sex, pre-stroke score on the mRS, NIHSS score at baseline, previous ischemic stroke, time from onset to recanalization, cerebral collateral circulation grade, number of thrombectomy device passes, and intravenous thrombolysis). According to previous studies4,31–37, these covariates were associated with outcomes after endovascular therapy in AIS. The 90-day mRS score was compared using ordinal logistic regression. Changes in NIHSS score or infarct volume between the two groups were compared using a geometric mean ratio by generalized linear model. Time-to-events of stroke recurrence and other vascular events, as well as occurrence of all-cause mortality at 90-days were compared using the Cox regression model. Proportional hazard assumption was tested by including an interaction between time and trial group in the model. The missing data in mRS score was imputed in sensitivity analyses using the last observation carried forward method, worst-case scenario, and best-case scenario. The last observation carried forward method was defined as that the missing mRS score at 90 days was imputed using the value of NIHSS measured at 24 h-12 days using the following relationship: NIHSS 0–3 at 24 h, or NIHSS 0–5 at 7–12 days will correspond to mRS 0–1 at 90 days, while others correspond to mRS 2–6 at 90 days. Given that different approaches for the missing outcome would affect the result, exploratory Tipping point analysis was also performed. Detailed statistical analyses are described in the statistical analysis plan (SAP). The SAP was revised at 28/05/2024, but the statistical methods were not changed, and the data was analyzed in accordance with the original SAP (shown in Clinical Trial information file). The multivariable models and imputation of missing of mRS score were performed as post-hoc analyses given that they were not described in SAP. Statistical tests were considered significant when the two-sided P value was less than 0.05.

The per-protocol population was defined as a sub-population of the mITT population whereby participants were excluded if they were lost to follow-up, withdrew consent, or did not adhere to study treatment (e.g., treated with incomplete ED treatment, or unplanned discharge). Statistical methods of the per-protocol population were the same as in the mITT analysis.

Stratification: The primary endpoint in the INSIST-ED study was further stratified by age (<60 vs. ≥60), sex (male vs female), pre-stroke mRS (0 vs. 1), NIHSS score at baseline (6–14 vs. ≥14), previous ischemic stroke, time from onset to recanalization (0–6 h vs. 6–9 h), cerebral collateral circulation grade (poor vs good), intravenous alteplase (yes vs no), and time-of-day of recanalization (day vs night). Differences of primary endpoint in the above specific stratifications were assessed by testing for interaction of the pre-set baseline variable with the primary endpoint.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Source data

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by grants from the Science and Technology Project Plan of Liao Ning Province (2022JH2/101500020). We thank the investigators and research staff (listed in Clinical Trial information) at the participating sites, members of the trial steering and data monitoring committees (listed in Clinical Trial information). We thank the participants, their families and friends.

Author contributions

Z.A.Z. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. H.S.C. designed the study and critically revised the manuscript. All authors participated in data collection. X.Y.S., S.Q.Q., and Y.C. analyzed the data. H.S.C., Z.A.Z., X.Y.S., S.Q.Q., Y.C., J.Q., W.L., H.Z., W.H.C., L.H.W., D.H.Z., Y.C., Y.T.M., Z.E.G., S.C.W., D.L., H.L., and T.N. vouch for the data and analysis, contributed to writing the paper. H.S.C. and Y.C. have full access to the data or verified the underlying raw data. H.S.C. has final responsibility for the decision to submit the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Ivy Cheung, Steffen Tiedt, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings described in this manuscript are available in the article, in the Supplementary Information, and from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with the paper. De-identified data collected for the study, including age, sex, baseline NIHSS score, treatment allocation, and functional outcome, will be shared following publication by requesting the corresponding author (Hui-Sheng Chen, email: chszh@aliyun.com) for academic purposes. The corresponding author will reply to the request within 2 months, subject to the approval of the ethics committees of the General Hospital of Northern Theater Command. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-025-57774-x.

References

- 1.Hankey, G. J. Stroke. Lancet389, 641–654 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Powers, W. J. et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: 2019 update to the 2018 guidelines for the early management of acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke50, e344–e418 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Liu, L. et al. Chinese Stroke Association guidelines for clinical management of cerebrovascular disorders: executive summary and 2019 update of clinical management of ischaemic cerebrovascular diseases. Stroke Vasc. Neurol.5, 159–176 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goyal, M. et al. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Lancet387, 1723–1731 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seker, F. et al. Reperfusion without functional independence in late presentation of stroke with large vessel occlusion. Stroke53, 3594–3604 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Chamorro, A., Dirnagl, U., Urra, X. & Planas, A. M. Neuroprotection in acute stroke: targeting excitotoxicity, oxidative and nitrosative stress, and inflammation. Lancet Neurol.15, 869–881 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chamorro, A., Lo, E. H., Renu, A., van Leyen, K. & Lyden, P. D. The future of neuroprotection in stroke. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry92, 129–135 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Collins, V. E. et al. 1,026 experimental treatments in acute stroke. Ann. Neurol.59, 467–477 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hill, M. D. et al. Efficacy and safety of nerinetide for the treatment of acute ischaemic stroke (ESCAPE-NA1): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet395, 878–887 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang, A. et al. Efficacy and safety of butylphthalide in patients with acute ischemic stroke: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol.80, 851–859 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Savitz, S. I., Baron, J. C., Yenari, M. A., Sanossian, N. & Fisher, M. Reconsidering neuroprotection in the reperfusion era. Stroke48, 3413–3419 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mizuma, A., You, J. S. & Yenari, M. A. Targeting reperfusion injury in the age of mechanical thrombectomy. Stroke49, 1796–1802 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schneider, A. M. et al. Cerebroprotection in the endovascular era: an update. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry94, 267–271 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Radak, D. et al. Apoptosis and acute brain ischemia in ischemic stroke. Curr. Vasc. Pharm.15, 115–122 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schaeffer, S. & Iadecola, C. Revisiting the neurovascular unit. Nat. Neurosci.24, 1198–1209 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuhn, A. L. et al. Biomechanics and hemodynamics of stent-retrievers. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab.40, 2350–2365 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nie, X., Leng, X., Miao, Z., Fisher, M. & Liu, L. Clinically ineffective reperfusion after endovascular therapy in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke54, 873–881 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu, R. et al. Edaravone dexborneol provides neuroprotective benefits by suppressing NLRP3 inflammasome-induced microglial pyroptosis in experimental ischemic stroke. Int Immunopharmacol.113, 109315 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng, B. et al. Edaravone protected PC12 cells against MPP(+)-cytoxicity via inhibiting oxidative stress and up-regulating heme oxygenase−1 expression. J. Neurol. Sci.343, 115–119 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang, N. et al. Edaravone reduces early accumulation of oxidative products and sequential inflammatory responses after transient focal ischemia in mice brain. Stroke36, 2220–2225 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mizuno, A., Umemura, K. & Nakashima, M. Inhibitory effect of MCI−186, a free radical scavenger, on cerebral ischemia following rat middle cerebral artery occlusion. Gen. Pharm.30, 575–578 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Almeida, J. R. et al. Borneol, a bicyclic monoterpene alcohol, reduces nociceptive behavior and inflammatory response in mice. ScientificWorldJournal2013, 808460 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu, H. Y. et al. The synergetic effect of edaravone and borneol in the rat model of ischemic stroke. Eur. J. Pharm.740, 522–531 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu, J. et al. Edaravone dexborneol versus edaravone alone for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke: a phase III, randomized, double-blind, comparative trial. Stroke52, 772–780 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fu, Y. et al. Sublingual edaravone dexborneol for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke: the TASTE-SL randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol.81, 319–326 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Desai, S. M., Jha, R. M. & Linfante, I. Collateral circulation augmentation and neuroprotection as adjuvant to mechanical thrombectomy in acute ischemic stroke. Neurology97, S178–S184 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lyden, P., Buchan, A., Boltze, J., Fisher, M. & STAIR XI Consortium*. Top priorities for cerebroprotective studies—a paradigm shift: report from STAIR XI. Stroke52, 3063–3071 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tate, W. J. et al. Thrombectomy results in reduced hospital stay, more home-time, and more favorable living situations in DEFUSE 3. Stroke50, 2578–2581 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tu, W. J. & Wang, L. D. Special Writing Group of China Stroke Surveillance R. China stroke surveillance report 2021. Mil. Med. Res.10, 33 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hacke, W. et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N. Engl. J. Med.359, 1317–1329 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Horn, N. et al. Predictors of poor clinical outcome despite complete reperfusion in acute ischemic stroke patients. J. Neurointerv. Surg.13, 14–18 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khatri, P. et al. Good clinical outcome after ischemic stroke with successful revascularization is time-dependent. Neurology73, 1066–1072 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lemmens, R. et al. Effect of endovascular reperfusion in relation to site of arterial occlusion. Neurology86, 762–770 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marto, J. P. et al. Twenty-four-hour reocclusion after successful mechanical thrombectomy: associated factors and long-term prognosis. Stroke50, 2960–2963 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zaidat, O. O. et al. First pass effect: a new measure for stroke thrombectomy devices. Stroke49, 660–666 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brugnara, G. et al. Multimodal predictive modeling of endovascular treatment outcome for acute ischemic stroke using machine-learning. Stroke51, 3541–3551 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoon, W., Kim, S. K., Park, M. S., Baek, B. H. & Lee, Y. Y. Predictive factors for good outcome and mortality after stent-retriever thrombectomy in patients with acute anterior circulation stroke. J. Stroke19, 97–103 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings described in this manuscript are available in the article, in the Supplementary Information, and from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with the paper. De-identified data collected for the study, including age, sex, baseline NIHSS score, treatment allocation, and functional outcome, will be shared following publication by requesting the corresponding author (Hui-Sheng Chen, email: chszh@aliyun.com) for academic purposes. The corresponding author will reply to the request within 2 months, subject to the approval of the ethics committees of the General Hospital of Northern Theater Command. Source data are provided with this paper.