Abstract

The increased prevalence of suicide among autistic people highlights the need for validated clinical suicide screening and assessment instruments that are accessible and meet the unique language and communication needs of this population. We describe the preliminary preregistered psychometric validation of the Suicide Assessment Kit-Modified Interview, in a sample of 98 autistic adults (58% women, 34% men, 7% nonbinary; MAGE = 41.65, SD = 12.96). A four-item negative affect score derived from the Suicide Assessment Kit-Modified Interview demonstrated adequate reliability (ω = 0.796, BCa 95% confidence interval = [0.706, 0.857]), as well as good convergent validity with related measures. Ordinal Suicide Assessment Kit-Modified Interview “categories” (1–5) demonstrated divergent validity (rs = −0.067 to 0.081) and good convergent validity, strongly correlating with mental health (rs = 0.446 to 0.744) and suicide assessment instruments (rs = 0.576 to 0.696). Suicide Assessment Kit-Modified Interview categories showed strong ability to predict participants identified by clinicians as “above low risk” of future suicide attempt (area under the curve = 0.887, posterior Mdn = 0.889, 95% credible interval = [0.810, 0.954], PAUC > 0.8 = 0.976). Suicide Assessment Kit-Modified Interview classifications > “Category 3” provided an observed sensitivity of 0.750 (Mdn = 0.810, [0.669, 0.948], PSe > 0.8 = 0.544) and an observed specificity of 0.895 (Mdn = 0.899, [0.833, 0.956], PSp > 0.8 = 0.995) for “above low risk” status. Our findings indicate that the Suicide Assessment Kit-Modified Interview is a psychometrically strong clinical assessment tool for suicidal behavior that can be validly administered to autistic adults without intellectual disability.

Lay Abstract

People with a diagnosis of autism are at increased risk of death by suicide. There is a need for clinical instruments that are adapted to the needs of autistic people. In this study, we modified and evaluated a clinical suicide interview (Suicide Assessment Kit-Modified Interview) for use with autistic people who do not have an intellectual disability. Autistic people helped us to modify the original version of the instrument by improving the questions, providing explanations for difficult terms or concepts, and recommending that we use different rating scales. Our results support the use of Suicide Assessment Kit-Modified Interview for assessing autistic adults without intellectual disability for suicidal thoughts and behavior. In the future, we will test how well Suicide Assessment Kit-Modified Interview works in clinical settings and with different clinical populations.

Keywords: adults, assessment, autism spectrum disorder, interview, measurement, risk, screening, suicidal behavior, suicidal ideation, suicide

Suicidal thoughts and behavior (STB) are common among people diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (henceforth “autism,” “autistic people”) (Bury et al., 2023), who are at significantly elevated risk of death by suicide when compared to the general population (Huntjens et al., 2024; Newell et al., 2023; O’Halloran et al., 2022; Mournet, Wilkinson, et al., 2023); for example, compared to Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 population data, the pooled relative risk for suicide in autistic people was around threefold that of the general population (RR = 2.86, 95% uncertainty interval = [2.06, 4.03]) (Santomauro et al., 2024). Autistic people experience a higher prevalence of co-occurring mental health conditions than in non-autistic populations (Lai et al., 2019; Uljarević, Hedley, Rose-Foley, et al., 2020), which may underpin the increased prevalence of STB (Jokiranta-Olkoniemi et al., 2021).

In addition to suicide risk factors shared with the general population, for example, mental health difficulties or unemployment, risk factors that may be particularly salient for autistic people include unmet support needs, loneliness, social support or connections, feeling a burden to others, life stress, and masking autistic traits (Brown et al., 2024; Cassidy, Bradley, Shaw et al., 2018; Cassidy et al., 2021; Hand et al., 2020; Hedley et al., 2018; Moseley et al., 2022, 2024). Unlike the general population, risk of suicide death in autistic females is similar or increased compared to autistic males (Kirby et al., 2024; Santomauro et al., 2024). Autistic people with certain intersectional identities, such as those who identify as transgender, may be at higher risk of STB (e.g. Strang et al., 2021), and the presence of additional co-occurring psychiatric conditions such as eating disorders and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) likely increases risk of STB among autistic people, but this has received limited attention in the literature thus far (Brown et al., 2024).

The presence of autism can complicate access to, and quality of mental health care (Camm-Crosbie et al., 2019), and may hinder the detection of both mental health conditions and STB. In non-autistic populations, nonsuicidal self-injurious behavior commonly precedes suicide attempts (Olfson et al., 2017, 2018) and, in both autistic and non-autistic populations, may act as a “gateway” for acquiring capability for lethal suicidal behavior (Moseley et al., 2020). In autism, self-injurious motor stereotypies (e.g. repetitive head-banging, biting, scratching) (Bodfish et al., 2000; Uljarević et al., 2023) are relatively common, and may be considered part of, or a symptom of the autism diagnosis. Hence, clinicians may not consider these behaviors a “red flag” for STB in the same way as they might in other (non-autistic) populations (Hedley et al., 2022). Other more “typical” self-injurious behaviors related to co-occurring psychopathology, such as cutting oneself, are also prevalent in the autistic population (Maddox et al., 2017; Moseley et al., 2020) and may be associated with STB (Cassidy, Bradley, Shaw, et al., 2018). This emphasizes the importance of assessing autistic people for presence of STB within healthcare settings.

The United States Joint Commission requires all people presenting at accredited hospitals and behavioral health care organizations to be assessed for STB using validated and evidence-based assessment tools (The Joint Commission, 2019). The increased prevalence of mental health conditions and suicide deaths among autistic people (Huntjens et al., 2024; Mournet, Wilkinson, et al., 2023; Newell et al., 2023; O’Halloran et al., 2022) highlights the need for the development and validation of effective and appropriate STB screening and assessment instruments that are accessible and meet the unique language and communication needs of this population (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Cassidy, Bradley, Bowen, et al., 2018; Hedley, Batterham, et al., 2023; Schiltz et al., 2023). Instruments not designed for use by autistic people may be less applicable and underestimate STB in this population due to complex vocabulary, sentence structure or grammar, confusing terms, imprecise response options, and language or concepts perceived to be ableist (Nicolaidis et al., 2020). Despite a call for adaptations to current STB assessment tools to improve the conceptualization and measurement of STB in autism (Cassidy, Bradley, Bowen et al., 2018), there are currently no structured clinical interview tools that have been adapted or validated for use within the autistic population. This is potentially problematic as autistic adults may not interpret test items in the way they are intended (Schiltz et al., 2023), leading to different functionality in autistic compared to non-autistic people (Cassidy, Bradley, Bowen et al., 2018). Although the gold-standard Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) (Posner et al., 2011) has been used with an autistic population, it was found to inadequately detect all autistic youth experiencing suicidal thoughts (Schwartzman et al., 2023).

The need for appropriate suicide screening and assessment instruments for autistic people is particularly acute in emergency departments. Although autistic youth are more likely to present at emergency departments for suicidal ideation and self-harm (Cervantes, Brown, & Horwitz, 2023) emergency department providers are not generally trained in assessing suicide risk in this population (Cervantes, Li, et al., 2023). The absence of validated risk assessment tools and evidence-based suicide risk management strategies specifically developed for use with autistic populations present significant barriers to provision of appropriate care within emergency department settings (Cervantes et al., 2024). Following discharge for STB, suicide risk screening can also be effective in identifying and potentially reducing subsequent suicide attempts (Miller et al., 2017), reinforcing the need for development of appropriate STB screening and assessment instruments for use in this population.

Although predicting future suicide attempts can be problematic, and patient safety should be prioritized over risk stratification (Saab et al., 2022), this does not obviate the importance of completing a thorough clinical assessment of STB, particularly in populations at high risk of suicide. Structured clinical assessments addressing STB directly are likely to be superior at identifying individuals at potential risk of suicide compared to routine or unstructured clinical assessments (Bongiovi-Garcia et al., 2009). To date, only three brief self-report questionnaires that screen and assess for suicidal ideation have been developed and validated for use by autistic people (Cassidy et al., 2021; Hedley, Batterham, et al., 2023; Williams et al., 2024). While the development of these tools represents an important step toward systematically assessing the presence and severity of suicidal ideation in autistic individuals, a comprehensive assessment of STB requires follow-up by a clinician using a purposively designed, structured clinical interview (The Joint Commission, 2019).

While psychometric properties of the Ask Suicide Screening Questions (ASQ) (Horowitz et al., 2012) and the two suicide related items from the Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview–Self Report (SITBI-SR) (Nock et al., 2007) have been examined for use with autistic adults (Mournet, Bal, et al., 2023), neither provide a comprehensive assessment of STB as outlined by the Joint Commission (2019). Of published clinical assessments for STB, the Systematic Tailored Assessment for Responding to Suicidality (STARS) is a licensed product requiring significant training provided by the authors (Hawgood & De-Leo, 2018; Hawgood et al., 2022). Although in widespread use, the C-SSRS (Posner et al., 2011) can be challenging to routinely administer in clinical settings due to its length, requiring patients to disclose significant detail concerning past suicide attempts. Possibly for these reasons, it is not uncommon in Australia for services to develop their own STB assessment scales or proformas (Department of Health, 2010), which are typically not validated or evidence based. Importantly, neither STARS nor C-SSRS have been adapted or validated for use within autistic populations.

The Suicide Assessment Kit Suicide Risk Screener (SAK-SRS) is a professionally administered, clinical interview developed to assess STB in clinical populations at elevated risk of suicide (Deady et al., 2015). The SAK-SRS offers several advantages over other available instruments: it does not require proprietary or costly training––administration instructions and videos are freely available on the Internet (Deady et al., 2015); it provides a comprehensive assessment of STB, risk and protective factors, presence of a plan, history of suicidal behavior; it demonstrates face validity being used clinically within the alcohol and other drug sector; it is brief, with clear questions and objective response criteria (i.e. predominantly Yes/No questions requiring minimal clinician interpretation); and it does not require respondents to disclose extensive details of past suicide attempts, instead focusing on current presentation. Importantly, the authors were amenable to modifying the instrument for use within the autistic population.

One potential limitation of the SAK-SRS is that it includes a template for risk stratification: respondents are classified as low-moderate-high risk of suicide based on a combination of their responses and clinician judgment. Given recommendations against overt risk stratification (i.e. due to poor reliability and predictive validity of risk categories) (Carter & Spittal, 2018; Franklin et al., 2017; Hawgood et al., 2022; O’Connor et al., 2013; Quinlivan et al., 2016) we revised the measure’s original coding guidelines, instead conceiving suicidality as a dimensional construct ranging from low-level ideation to active intent. Moreover, we acknowledge that all STB has potential to cause significant distress even in the absence of overt suicide attempts (van Spijker et al., 2011) and that patient safety must be prioritized (Saab et al., 2022). Therefore, in addition to making the tool suitable for use with autistic adults, we aimed to ensure that our dimensional coding scheme captured different levels of “STB severity” that could ostensibly predict greater chronicity and intensity of suicidal ideation, even in individuals who will never attempt suicide. Nevertheless, those categorized as “most suicidal” on the modified SAK-SRS are, by design, individuals who may be at imminent risk of suicide attempt (e.g. those who endorse a suicide plan, intent to follow through, and some preparatory steps taken, with few or no protective factors). Although we expected that presence of more severe STB would be positively associated with clinically identified suicide risk, we emphasize that wherever STB is present there is risk of suicide attempt; thus, clinical intervention is recommended to provide access to resources and supports, reduce distress, and ensure patient safety.

In this study we assessed preliminary evidence for the internal consistency, reliability, and the convergent, divergent and predictive validity of a modified version of SAK-SRS that was administered to autistic adults without intellectual disability, who are among the most at risk of STB (Huntjens et al., 2024; Mournet, Wilkinson, et al., 2023; Newell et al., 2023; O’Halloran et al., 2022), including premature death by suicide (Hirvikoski et al., 2016; Santomauro et al., 2024). Specifically, we compared the modified instrument (Suicide Assessment Kit-Modified Interview; SAK-MI) against existing, validated mental health and suicide screening and assessment instruments. Although we argue against risk stratification for clinical purposes, for this study we additionally assessed predictive validity for the SAK-MI against clinician-based assessment of suicide risk (i.e. as part of the ethics protocol the research team classified participants’ level of suicide risk according to questionnaire responses and, if required, interview by a registered psychologist). We formally involved autistic people when revising SAK-MI to maximize the likelihood that the new instrument would be accessible to autistic adults.

Method

This study’s design, hypotheses and analytic plan were preregistered on the open science framework (Hedley, Williams, et al., 2023). All data, analysis code, and research materials are available upon request from the first author. Data were analyzed using R version 4.3.0 (R Core Team, 2023).

Participants

Participants were 105 adults (women = 60%, men = 32.4%, nonbinary = 7.6%; Mage = 42.42, SD = 13.22 years, range = 20–71) who completed the SAK-MI. Participants were required to be 18 years of age, read and communicate in English, not have a current diagnosis of intellectual disability, be willing to nominate an emergency contact (required as part of the ethical procedure), and self-report a formal autism diagnosis from a qualified health professional (e.g. pediatrician, psychiatrist, psychologist, neurologist); to support their diagnosis, participants were also required to provide details of the year of diagnosis and the type (e.g. “autism spectrum disorder,” “Asperger’s syndrome”). No participants were excluded based on language requirements; one non-speaking participant elected to communicate with the research team via the message function in Zoom. Further details of the sample and processes for confirming diagnoses have been published elsewhere (Arnold et al., 2019; Hedley, Batterham, et al., 2023; Hedley et al., 2021; Richdale et al., 2022). Seven participants (women = 85.7%, nonbinary = 14.3%; Mage = 53.29, SD = 12.89 years, range = 28–67) were subsequently excluded from the present sample due to not reporting a formal diagnosis; the final sample included 98 autistic adults (women = 58.2%, men = 34.7%, nonbinary = 7.1%; Mage = 41.65, SD = 12.96 years, range = 20–71), none of whom reported a current diagnosis of co-occurring intellectual disability.

Procedure

The study was approved by La Trobe University Human Research Ethics Committee (HEC20235). Participants were recruited from one of two longitudinal studies conducted in Australia (Longitudinal Study of Australian School Leavers with Autism, SASLA, 15–25 years; Australian Longitudinal Study of Autism in Adulthood, ALSAA, 25+ years) (Arnold et al., 2019; Richdale et al., 2022) via an advertisement in a regular newsletter sent to all participants in these two studies. Interested individuals contacted the researchers for further information about the study and provided contact information. A member of the research team contacted the individual to explain the study, answer questions, and to confirm eligibility. Data were collected as part of a larger study with three data collection points. Upon completion, participants received AUD $100 in vouchers for completion of all datapoints.

Consistent with a multi-trait multi-method approach (Campbell & Fiske, 1959), we collected data using a variety of methods (e.g. self-report, interview using different interviewers) and different measures of the same construct (e.g. depression and STB were assessed with several different measures; see measures section below). Data for the present study were collected at two time points; Baseline (T1) data were collected via self-report online survey, follow-up (T2) data were collected approximately 3 months later (M = 111, SD = 25.28 days, range = 47–158) via (Zoom) interview, between October 2020 and July 2021 using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) tools hosted at La Trobe University (Harris et al., 2019). Demographic data were collected at T1. The presence of STB was managed through development of a protocol which included follow-up by a registered psychologist where there was any concern of possible suicidal behavior (Byme et al., 2021; Hedley, Batterham, et al., 2023; Hedley et al., 2021). Both SAK-MI and the C-SSRS were administered as a clinical interview by author D.H. or a master’s level psychology student at T2, with order counter-balanced between instruments.

Clinician determined suicide risk level was based on the study risk protocol (see Hedley, Batterham, et al., 2023; Hedley et al., 2021) and involved discussion with a registered psychologist on the team (authors S.M.B, M.A.S.) following review of scores on any instrument or interview. For any participant assessed as being above low-risk, the psychologist contacted the participant by telephone to conduct one or more follow-up risk-assessment interviews. Where there was any concern for possible self-harm, the psychologist stayed in contact with the participant and conducted repeated follow-up risk assessments until the participant was no longer deemed to be at-risk and/or was connected with an appropriate professional (e.g. local psychologist) or service. Where appropriate to do so, the psychologist made referrals to services on behalf of the participant. Participants who were not identified as requiring follow-up (i.e. low risk) would typically not have indicated any past or current STB or scored in the clinical range on any mental health instrument (e.g. Patient Health Questionnaire, PHQ-9; Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales; DASS-21). At completion of the study all case notes were reviewed by the research team and a final risk category (“low risk,” “above low risk”) was agreed on. The SAK-MI algorithm was developed and calculated by author Z.J.W. who was blinded to other participant data (e.g. risk status, clinical notes) until after scores were calculated.

Measures

Primary measure

Suicide Assessment Kit-Modified Interview (SAK-MI)

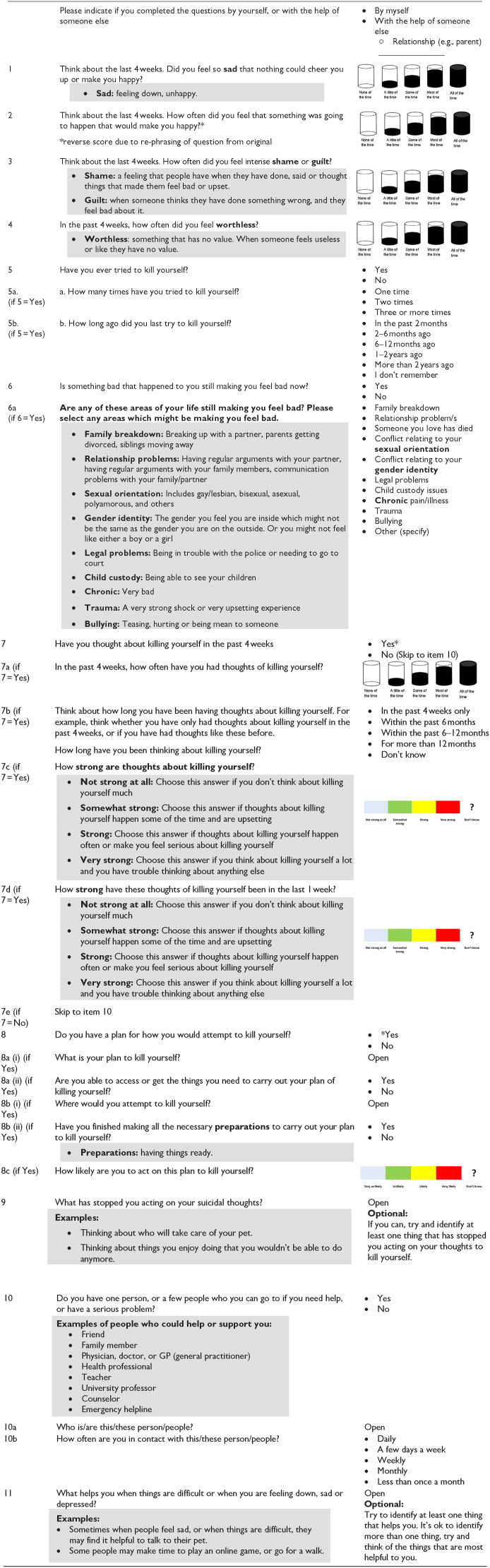

SAK-MI (T2; Appendix 1) is a revised version of the Suicide Assessment Kit Suicide Risk Screener (SAK-SRS) (Deady et al., 2015), which in the present study was administered as an interview by a member of the research team. The original SAK-SRS consists of 11 primary questions, with follow-up questions used to elicit more detail depending on participant responses. The SAK-MI assesses negative affect over the past 4 weeks (Q’s 1–4), current stressors (Q6), lifetime, last 4 weeks, and last one-week suicidal ideation, including the strength of ideation (Q7), and lifetime (Q5) and current (Q8) suicidal behavior, including details of any suicide plan. Protective factors are identified in the remaining items (Q9–11). In the present study we revised SAK-SRS so that questions would be suitable for use with autistic adults, as well as for individuals with other developmental or psychiatric concerns who would also potentially benefit from the modifications. These included changes to language/wording, provision of response exemplars and definitions, and visual analogue response scales (Appendix 2). Following guidelines for participatory research (Nicolaidis et al., 2019; Staniszewska et al., 2017), we engaged with people with lived experience as content experts and as peer researchers.

The revision of the instrument involved a process of consultation and engagement with one of the original authors of the instrument (author M.D.) and a panel of content experts including suicide prevention and developmental disability researchers (including with lived experience), medical professionals, registered psychologists and autistic peer researchers. Excepting autistic members who were members of the study advisory group (who were compensated for their contributions to the study), these individuals were not compensated financially. We additionally engaged a group of 10 autistic adults representing diversity in gender, cultural, mental health, suicidal behavior, and ability (“the Panel”). The Panel independently reviewed SAK-MI and provided a written report with specific recommendations which were incorporated into the final revision (see Supplementary Table S1 for specific recommendations and associated revisions). The Panel members were reimbursed at a professional rate.

A revised coding algorithm (Appendix 3) was developed for SAK-MI utilizing a categorical approach whereby responses are coded to arrive at one of five ordinal categories of STB (“Category 1” to “Category 5”), with Category 1 reflecting the most mild presentation (“history of suicidality absent, current stressors absent, ideation absent, support networks present, may have elevated negative affect score”) and Category 5 representing the most severe presentation (“presence of plan, preparations, maybe unwilling to disclose details of plan, absence of protective factors or support network, unable to identify any reason to live”). In addition to closed-ended questions, SAK-MI includes five possible open-ended questions. However, these questions are not included in the categorization algorithm for the measure and were not analyzed in the present study. A set of “suggested actions” were developed based on the clinical expertise of the research team and are provided with the coding algorithm. In addition, the first four items of the scale (each scored on 5-point pictorially enhanced Likert-type scale from 0 (“None of the time”) to 4 (“All of the time”)) are summed to derive a separate dimensional “Negative Affect” score. The specific algorithms used to assign individuals to severity categories were derived based on the collective clinical experience of the author team and were based loosely on the risk stratification levels of the SAK-SRS (Deady et al., 2015). Author Z.J.W., the team psychometrician, provided an initial operationalization of the scoring algorithm based on discussions with the senior author (D.H.) and his own clinical experience. All other authors provided iterative feedback on the preliminary SAK-MI algorithm until consensus was reached regarding its suitability for clinical use. The final SAK-MI categories 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 approximately correspond to “no (reported) suicidality,” “minimal suicidality,” “mild suicidality,” “moderate suicidality,” and “severe suicidality,” with higher categories representing both higher levels of acuity and chronicity/distress simultaneously.

Divergent validity

COVID-19 Impact Scale (CIS)

The CIS (T1) was administered to assess divergent validity (Stoddard & Kaufman, 2020; Stoddard et al., 2021 May 24. It contains 12 self-report items that assess the impact of COVID-19, with no set response period. In the present study we used the first eight items of the CIS (CIS-8; Cronbach’s α = 0.64–0.75); items are rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from zero (no change) to three (severe) on how much the pandemic has affected areas of their life, for example, routines, income/employment, health care, social supports, stress. Total scores range from 0 to 24. We have previously reported CIS with a sample overlapping with the present study (Hedley, Batterham, et al., 2023; Hedley et al., 2021). In the present study the CIS demonstrated good reliability, categorical ω = .825, 95% BCa bootstrap CI (.748, .875).

Convergent Validity

Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)

PHQ-9 (T1) consists of eight items that assess depressive symptoms and the final item that assesses the presence and duration of self-harm over the past 2 weeks (Kroenke & Spitzer, 2002). Items are rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). In the present study, items one to eight were used to assess depressive symptoms (PHQ-8, range 0–24; higher scores indicate greater depressive symptoms) and item-9 was used as an indicator of suicidal ideation (range, 0–3). The PHQ-9 has been found to be psychometrically adequate in autistic individuals using a sample that partially overlaps with the one in the current study (Arnold et al., 2020). In the present study, the PHQ-8 exhibited good reliability, categorical ω = 0.875, 95% BCa bootstrap CI = [0.815, 0.917].

Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS-21; T2)

DASS-21 (T2) consists of 21 items that assess depression, anxiety, and stress over the past week (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995). In the present study DASS-21 was administered at T2 as an interview. Responses are scored on a 4-point scale (never, sometimes, often, almost always) and relate to symptoms over the past week, with higher scores indicating greater severity. The measure has previously been psychometrically assessed in autistic adults, with support for its original factor structure (Park et al., 2020). In the present study, the Depression, ω = 0.907, 95% BCa bootstrap CI = [0.869, 0.932], Anxiety, ω = 0.833, [0.755, 0.879], and Stress, ω = 0.856, [0.793, 0.896], subscales all demonstrated strong reliabilities.

Suicidal Ideation Attributes Scale-Modified (SIDAS-M)

SIDAS-M (T1) is a five-item assessment of suicidal ideation which assesses frequency, controllability, closeness to attempt, distress, and interference with daily activities over the last 4 weeks (Hedley, Batterham, et al., 2023). Items are assessed on 10-point Likert-type scales, with total scores ranging from 0 to 50. The original version of the instrument (SIDAS) (van Spijker et al., 2014) was modified for use and validated with an autistic sample overlapping with the current study (Hedley, Batterham, et al., 2023). In the present sample, reliability was high, unidimensional ω = 0.933, 95% BCa bootstrap CI = [0.890, 0.958].

Suicidal Behavior Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R)

SBQ-R (T1) consists of four self-report items which assess STB (e.g. threat of suicide attempt, self-reported likelihood of future suicidal behavior), over the lifetime (“ever”) or in the past year. Higher scores indicate a greater number of suicidal behaviors (range, 3–18) (Osman et al., 2001). Although this measure has been found to lack measurement invariance between autistic and non-autistic individuals (Cassidy et al., 2020), it is structurally unidimensional and has been psychometrically validated for within-group use within the autistic population. The autism revision was not available when the present study was conducted; nevertheless, reliability was adequate in the present study, categorical ω = 0.773, 95% BCa bootstrap CI = [0.688, 0.839].

Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS, lifetime version)

C-SSRS (T2) is a semi-structured interview used to assess history (“whole life”) and recent (“most recent”) STB and has been used with autistic adolescents (Masi et al., 2020; Posner et al., 2011; Schwartzman et al., 2023). C-SSRS was administered by trained members of the research team. In all cases where suicidal behavior was reported on the C-SSRS, coding was reviewed by a medical doctor on the team (author M.U.), and any coding disagreements were resolved through discussion. C-SSRS provides two subscales assessing severity and intensity of ideation and five behavior scales (i.e. non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), suicide attempts, interrupted attempts, aborted attempts, and preparatory attempts). The severity subscale is comprised of five items ranging from zero (“no suicidal ideation”) to five (“suicidal intent with plan”), and the intensity subscale is derived from five Likert-type items (range, 0–5) which assess the frequency, duration, and controllability of suicidal thoughts, as well as the presence of deterrents and reasons for ideation. In the current study, the “reasons for ideation” item was excluded from the intensity subscale due to poor associations with the remainder of the scale, and items 3 (“Controllability”) and 4 (“Deterrents”) were re-coded such that the “Does not attempt to control thoughts” and “Does not apply” (i.e. no deterrents referenced) responses became scores of “6” (total score range for the re-coded intensity score: 0–22). A single suicidal behavior scale was created by summing four behavior scales, excluding NSSI. This score ranged from zero (no suicidal behavior) to four (all four behaviors were reported). In the current study reliability was good for both the Severity subscale, ω = 0.911, 95% BCa bootstrap CI = [0.854, 0.950]), as well as the intensity subscale, categorical ω = 0.807, [0.699, 0.873].

Sample size

As a follow-up study, we were constrained on sample size by the size of the initial longitudinal studies from which the sample was drawn from, and the maximum number of participants possible was recruited from the parent studies without an a priori target. Notably, a frequentist power analysis indicates that a sample of 98 individuals has power of 85.8% to detect a correlation of r = 0.3 at a two-sided p < 0.05 level. Though the Bayesian analyses used in the present study (described below) are not entirely equivalent to a frequentist correlation test, they behave similarly enough to indicate that when true correlations are moderate or larger in size (i.e. all substantive correlations we sought to test in our preregistered hypotheses), we are well-powered in the present sample to detect them.

Data analytic approach

Basic demographics and clinical data were examined descriptively. The internal consistency and reliability of the SAK-MI negative affect score (and convergent/divergent measures) was evaluated using McDonald’s coefficient omega (ω) (McDonald, 1999) and its categorical extension (Green & Yang, 2009), both based on a unidimensional confirmatory factor model. Convergent validity was assessed by examining robust (student-t based) Bayesian correlations (Kurz, 2022, December 11) between SAK-MI Negative Affect Score, PHQ-8 total score, and DASS-21 (depression, stress, anxiety) scales; as well as Bayesian polyserial correlations between SAK-MI category (1–5) and the SBQ-R, SIDAS-M (T1), DASS-21 subscales and C-SSRS indices (T2). Bayesian bootstrapped (polychoric and polyserial) correlations (Rodriguez & Williams, 2021) were also used to assess the associations between the SAK-MI and PHQ-8 total score, PHQ item-9, and the difference between them. Divergent validity was assessed by examining the correlations between SAK-MI and CIS-8 score. Predictive validity was assessed by examining relationships between SAK-MI category (1–5; T2) and C-SSRS lifetime suicidal behavior scores (T2) using Bayesian Gaussian rank correlations (based on Bayesian bootstrapping). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed to determine SAK-MI sensitivity and specificity for participants classified as low or above low suicide risk following T2 interviews. Area under the curve (AUC) was provided descriptively (with a 95% credible interval (CrI) based on Bayesian bootstrapping), and the sensitivity, specificity, positive/negative predictive values, and diagnostic likelihood ratios at each SAK-MI cutoff were also provided (95% CrIs also based on Bayesian bootstrapping). For the purposes of this study, a cut point was then determined based on a combination of both sensitivity and specificity (with a target of ⩾ 80% sensitivity and specificity simultaneously). There were no missing data on any of the variables (aside from data that were missing due to form skip-logic), and therefore complete-case analysis was used in the current study.

Bayesian methods were used, as they allowed us to formalize and test specific hypotheses about the distributions of effect sizes (e.g. falling within a null interval or being larger/smaller than a certain cutoff) with clear and operationalized criteria for “convergent” and “divergent” validity of our measure. We operationalized divergent validity as the SAK-MI demonstrating no significant correlation (a 95% highest-density CrI that overlaps zero) with the criterion scale (i.e. the CIS), as well as a Bayes factor for the region of practical equivalence (ROPE) [−0.1, 0.1] (BFROPE) less than 1 (Liao et al., 2021; Linde et al., 2023; Makowski et al., 2019). For linear (student-t based) and polyserial correlations in which a Bayes factor could be calculated, we operationalized convergent validity as a combination of (a) a significant ROPE Bayes factor for a ROPE of r = [−0.1, 0.1] (BFROPE > 3 for all but SIDAS-M and SBQ-R, which used BFROPE > 10) and (b) a high posterior probability that the true correlation lies outside of the ROPE (i.e. p(r > 0.1|data), denoted p > ROPE > 0.95). For correlations based on Bayesian bootstrapping, convergent validity was operationalized as p > ROPE > 0.95 (no Bayes factors could be calculated due to the lack of a prior). All convergent hypotheses testing correlations of any type with other suicide measures included additional posterior probability criteria in which there was at least a 50% posterior probability that the correlation was at least greater than a certain size (typically p(r > 0.5|data) > 0.5, with r > 0.4 used for the C-SSRS severity score and r > 0.3 used for the C-SSRS suicidal behavior score). These correlation magnitudes were preregistered, and their differential magnitudes reflected our prior beliefs regarding the “nomological net” of the dimensional suicidality construct captured by the SAK-MI categories (Cronbach’s & Meehl, 1955; Schimmack, 2021). We additionally tested whether the SAK-MI score would correlate more strongly with the PHQ-9 item-9 than the remaining items (PHQ-8 total score), as operationalized by ∆r > 0.1 (with the 95% CrI of the difference allowed to cross zero). Finally, for the ROC curve analysis, we hypothesized that at least one SAK-MI cutoff would be found which would simultaneously produce both ⩾80% sensitivity and specificity for detecting clinician-rated “above low risk” cases.

Model fitting for linear and polyserial correlations was performed in a Bayesian framework using the R package brms (Bürkner, 2017, 2018). We employed weakly informative priors for both models, with the linear correlation model (multivariate student-t likelihood) including a Lewandowski-Kurowicka-Joe (LKJ) (Lewandowski et al., 2009); prior (η = 2) on the correlation matrix of random effects, a t3(Mdn, MAD) prior on intercepts [brms default], a t3(0, MAD) [brms default] prior on log(σ), and a gamma (2,0.1) prior on the degree-of-freedom parameter ν [brms default]. The polyserial correlation model (cumulative likelihood with probit link) included a t3(0, 2.5) on intercepts [brms default], as well as a Normal (0, 1) prior on regression slopes, which were standardized before running the model. Parameters were estimated via Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) using the No U-turn Sampler (Hoffman & Gelman, 2014). Posterior distributions were generated using 40,000 post-warmup MCMC draws from 5 separate Markov chains. Bayesian bootstrapping was conducted using custom-written functions (Williams, 2020, 2024) based on the BBcor R package (Rodriguez & Williams, 2021), each using 5000 reweightings to calculate new posterior distributions. Posterior distributions were summarized using the median and 95% highest-density credible interval.

Community involvement statement

An autistic advisory group was consulted regarding the study design prior to commencement. Autistic people were involved in the codesign of the SAK-MI alongside the research team and the expert panel, specifically contributing to the development of the questions, response guide, and language use. An autistic advisory group reviewed early versions of the instrument and reviewed and approved all subsequent revisions. In addition, author Z.J.W. is an autistic clinician-scientist who served as the primary statistician/quantitative methodologist on the current project, leading the development of the SAK-MI scoring algorithm, formalizing the preregistered data analysis plan and hypotheses, serving as primary data analyst, and contributing to the writing and final approval of the manuscript.

Results

Demographics

Table 1 provides participant demographics and history of suicidal behavior (assessed with the C-SSRS). Participants were predominantly born in Australia (79%), had completed post-secondary education (85%), were living with someone (78%), and were employed (52%). Most common co-occurring diagnoses were anxiety (71%) and depression (69%). One participant reported being diagnosed with developmental delay and one reported an historical diagnosis of intellectual disability as a child but no longer met criteria as an adult (supported by completion of post-graduate qualifications). Overall, the C-SSRS revealed that history of suicidal ideation (91.8%) and suicide attempts (41.8%) were common among participants. The minimum age of first suicide attempt was 7 years and the oldest age of first attempt was 45 years (Mage = 19.39 years, SD = 9.28). Among those who had attempted suicide, the minimum number of suicide attempts by any participant was 1 attempt and the maximum was 26 (M = 3.36 attempts, SD = 4.43). In addition, NSSI was commonly reported by participants (63.3%).

Table 1.

Demographics and C-SSRS suicidal behavior (n = 98).

| Variable | Label | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Country of birth | Australia | 77 (78.6%) |

| Other | 21 (21.4%) | |

| Language at home | English | 92 (93.9%) |

| Other | 6 (6.1%) | |

| Education | Secondary school | 15 (15.3%) |

| Certificate/diploma | 24 (24.5%) | |

| Post-graduate degree | 59 (60.2%) | |

| Living | Spouse/partner | 38 (38.8%) |

| Alone | 22 (22.4%) | |

| Parents/relative | 19 (19.4%) | |

| Other | 19 (19.4%) | |

| Relationship a | Single | 43 (43.9%) |

| Partnered | 25 (25.5%) | |

| Same sex relationship | 6 (6.1%) | |

| Married/engaged | 24 (24.5%) | |

| Separated/divorced | 10 (10.2%) | |

| Other | 6 (6.1%) | |

| Employment | Full-time (35+ hours p/week) | 22 (22.4%) |

| Part-time | 29 (29.6%) | |

| Not working/retired | 47 (48%) | |

| Primary diagnosis | Autism spectrum disorder | 50 (51%) |

| Asperger’s syndrome | 43 (43.9%) | |

| Other b | 5 (5.1%) | |

| Other diagnoses a | Anxiety/depression | 69 (70.4%) |

| Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder | 31 (31.6%) | |

| Visual impairment | 8 (8.2%) | |

| Hearing impairment/deaf | 5 (5.1%) | |

| Speech/language delay | 3 (3.1%) | |

| Developmental delay | 1 (1%) | |

| Intellectual disability c | 1 (1%) | |

| Seizure disorder/epilepsy | 2 (2%) | |

| Suicidal thoughts and behavior | Wish to be dead | 90 (91.8%) |

| Suicide attempt | 41 (41.8%) | |

| Non-suicidal self-injury | 62 (63.3%) | |

| Interrupted suicide attempt | 16 (16.3%) | |

| Aborted suicide attempt | 20 (20.4%) | |

| Preparatory behavior | 26 (26.5%) |

Note. All values other than those in the “Suicidal thoughts and behavior” section (which were assessed using the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS)) were obtained from participants using a self-report demographics questionnaire.

Multiple selections possible.

Responses included Autistic Disorder, High Functioning Autism, Pervasive Developmental Disorder Not Otherwise Specified.

Historical diagnosis, not current.

Reliability

The reliability of the four-item SAK-MI negative affect scale was adequate, as demonstrated by the categorical omega coefficient (categorical ω = 0.796, BCa 95% CI = [0.706, 0.857]).

Convergent and divergent validity

Sample descriptive statistics for all outcome measures are presented in Table 2 and Supplementary Table S2 provides frequency counts for each of the SAK-MI items. A summary of convergent and divergent correlations for the SAK-MI is presented in Table 3. The CIS-8 total score was not significantly correlated with either the SAK-MI Negative Affect score (r = −0.067, 95% CrI = [−0.268, 0.131], BFROPE = 0.130, p > ROPE > 0.999) or SAK-MI category (rpoly = 0.081, 95% CrI = [−0.119, 0.280], BFROPE = 0.078, p > ROPE > 0.999), supporting the hypothesis of divergent validity for both indices. In contrast, the association between SAK-MI Negative Affect and the PHQ-8, the correlation was strong and positive (r = 0.548, 95% CrI = [0.398, 0.680], BFROPE = 2.73 × 105, p > ROPE > 0.999). Similar strong correlations were found between the SAK-MI negative affect score and all DASS-21 subscales, with the depression correlation notably stronger than the others (Depression: r = 0.744, 95% CrI = [0.647, 0.831], BFROPE = 2.60 × 1012, p > ROPE > 0.999; Anxiety: r = 0.507, 95% CrI = [0.345, 0.647], p > ROPE > 0.999, BFROPE = 7.02 × 103; Stress: r = 0.561, 95% CrI = [0.414, 0.692], BFROPE = 1.28 × 105, p > ROPE > 0.999). We also examined the associations between SAK-MI category and the two PHQ-based indices (PHQ-8 score and PHQ-9 item 9), finding large and significant correlations with both measures (PHQ-8: rpoly = 0.446, 95% CrI = [0.295, 0.604], p > ROPE > 0.999; PHQ-9 item 9: rpoly = 0.699, 95% CrI = [0.538, 0.834], p > ROPE > 0.999). Consistent with our hypothesis, we additionally found that the PHQ-9 suicidality item (item 9) correlated more strongly with the SAK-MI category than the remaining items tapping other depressive symptoms (∆r = 0.250, 95% CrI = [0.092, 0.395], Pd > 0.999).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for outcome variables used in present study.

| Variable | M (SD) [MIN–MAX] OR frequency table | Theoretical range |

|---|---|---|

| SAK-MI Negative Affect | 6.29 (3.42) [1.00–15.00] | 0–16 |

| SAK-MI Category | 27 / 14 / 39 / 13 / 5 | 1–5 |

| CIS-8 Total | 7.94 (4.99) [0.00–25.00] | 0–25 |

| PHQ-8 Total | 10.48 (6.00) [0.00–24.00] | 0–24 |

| PHQ-9 Item 9 | 61 / 22 / 7 / 8 | 0–3 |

| DASS-21 Depression | 15.57 (11.19) [0.00–42.00] | 0–42 |

| DASS-21 Anxiety | 9.96 (8.79) [0.00–34.00] | 0–42 |

| DASS-21 Stress | 19.88 (10.37) [0.00–42.00] | 0–42 |

| SIDAS-M | 7.43 (10.67) [0.00–45.00] | 0–50 |

| SBQ-R | 10.04 (3.76) [3.00–18.00] | 3–18 |

| C-SSRS Ideation Severity (Recoded) | 13.50 (5.39) [0.00–22.00] | 0–22 |

| C-SSRS Ideation Intensity | 7 / 2 / 8 / 12 / 12 / 57 | 0–5 |

| C-SSRS Suicidal Behavior | 24 / 26 / 21 / 14 / 10 / 3 | 0–5 |

Note. For the ordinal variables (SAK-MI Category, PHQ-9 item 9, C-SSRS ideation intensity and suicidal behavior), the middle column provides full frequency distributions in the sample (n = 98), ranging from lowest to highest value (e.g. “n Category 1” / “n Category 2” / “n Category 3” / “n Category 4” / “n Category 5” for SAK-MI Category). SAK-MI = Suicide Assessment Kit-Modified Interview; CIS-8 = COVID-19 Impact Scale; PHQ-8 = Patient Health Questionnaire–8 item composite; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire–9; DASS-21 = Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales; SIDAS-M = Suicidal Ideation Attributes Scale–Modified; SBQ-R = Suicidal Behavior Questionnaire–Revised; C-SSRS = Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale.

Table 3.

Convergent and divergent correlations between the SAK-MI and external variables.

| Variable | SAK-MI negative affect | SAK-MI category | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r [95% CrI] | BF ROPE | p > ROPE | r [95% CrI] | BF ROPE | p > ROPE | Magnitude test | |

| CIS-8 | -0.067 [-0.268, 0.131] | 0.130 | 0.376 | 0.081 [-0.119, 0.280] | 0.078 | 0.426 | — |

| PHQ-8 | 0.548 [0.398, 0.680] | 2.73 × 105 | >0.999 | 0.446 [0.295, 0.604] | — | >0.999 | — |

| DASS-21 Depression | 0.744 [0.647, 0.831] | 2.6 × 1012 | >0.999 | 0.484 [0.324, 0.627] | 864 | >0.999 | — |

| DASS-21 Anxiety | 0.507 [0.345, 0.647] | 7.02 × 103 | >0.999 | 0.473 [0.313, 0.618] | 672 | >0.999 | — |

| DASS-21 Stress | 0.561 [0.414, 0.692] | 1.28 × 105 | >0.999 | 0.387 [0.202, 0.545] | 36.4 | >0.999 | — |

| SIDAS-M | 0.426 [0.242, 0.595] | 184 | >0.999 | 0.633 [0.506, 0.741] | 1.56 × 106 | >0.999 | p(r > 0.5|data) = 0.971 |

| SBQ-R | 0.438 [0.268, 0.594] | 606 | >0.999 | 0.696 [0.587, 0.785] | 4.79 × 107 | >0.999 | p(r > 0.5|data) = 0.998 |

| C-SSRS Severity | 0.228 [0.013, 0.437] | 0.601 | 0.869 | 0.576 [0.393, 0.724] | — | >0.999 | p(r > 0.4|data) = 0.965 |

| C-SSRS Intensity | 0.246 [0.051, 0.432] | 2.13 | >0.999 | 0.623 [0.484, 0.736] | 1.33 × 106 | >0.999 | p(r > 0.5|data) = 0.951 |

| C-SSRS Suicidal Behavior | 0.217 [0.023, 0.402] | 0.615 | 0.875 | 0.647 [0.502, 0.763] | — | >0.999 | p(r > 0.3|data) > 0.999 |

Note. Correlations were conducted using a combination of robust Bayesian linear correlations and Bayesian polychoric/polyserial correlations. CIS-8 = COVID-19 Impact Scale; PHQ-8 = Patient Health Questionnaire–8 item composite; DASS-21 = Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales; SIDAS-M = Suicidal Ideation Attributes Scale–Modified; SBQ-R = Suicidal Behavior Questionnaire–Revised; C-SSRS = Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale; SAK-MI = Suicide Assessment Kit-Modified Interview; BFROPE = Bayes Factor for the Region of Practical Equivalence (ROPE, i.e. (−0.1, 0.1)); p > ROPE = posterior probability that the correlation parameter exceeds the ROPE.

SAK-MI category converged strongly with all other suicide-related variables examined. The new measure demonstrated strong convergent validity with both the SIDAS-M (rpoly = 0.633, 95% CrI = [0.506, 0.741], BFROPE = 1.56 × 106, p > ROPE > 0.999, p(r > 0.5|data) = 0.971) and the SBQ-R total score (rpoly = 0.696, 95% CrI = [0.587, 0.785], BFROPE = 4.79 × 107, p > ROPE > 0.999, p(r > 0.5|data) = 0.998). Scores from the C-SSRS also correlated strongly with the SAK-MI category, including the C-SSRS severity score (rpoly = 0.576, 95% CrI = [0.393, 0.724], p > ROPE > 0.999, p(r > 0.4|data) = 0.965), recoded C-SSRS intensity score (rpoly = 0.623, 95% CrI = [0.484, 0.736], BFROPE = 1.33 × 106, p > ROPE > 0.999, p(r > 0.5|data) = 0.951), and C-SSRS suicidal behavior score (rGR = 0.647, 95% CrI = [0.502, 0.763], p > ROPE > 0.999, p(r > 0.3|data) > 0.999).

ROC curve analysis

Based on ROC curve analyses, the SAK-MI category provided strong ability to predict individuals who were “above low risk” of future suicide attempt (n = 12 (12.2%)) requiring additional intervention from the study team (AUC = 0.887, posterior Mdn = 0.889, 95% CrI = [0.810, 0.954], PAUC > 0.8 = 0.976). Although no cut point was found at which both observed sensitivity and specificity were simultaneously ⩾ 0.8, the posterior median sensitivity and specificity (based on Bayesian bootstrapping) were both ⩾ 0.8 for SAK-MI > “Category 3” (i.e. scores of “Category 4” or “Category 5” being labeled as “above low risk”; Table 4), and thus this was chosen as the optimal cutoff for the measure. At this cutoff, observed sensitivity was 0.750 (posterior Mdn = 0.810, 95% CrI = [0.669, 0.948], PSe > 0.8 = 0.544) and observed specificity was 0.895 (posterior Mdn = 0.899, 95% CrI = [0.833, 0.956], PSp > 0.8 = 0.995). Although sensitivity could be improved to 100% by classifying “Category 3” or higher as “above low risk,” this came at a cost of a substantial amount of specificity (observed specificity = 0.477, posterior Mdn = 0.476, 95% CrI = [0.372, 0.579], PSp > 0.8 < 0.001).

Table 4.

Sensitivity, specificity, predictive values, and likelihood ratios for the SAK-MI.

| Cutoff | Sensitivity (Mdn) [95% CrI] |

Specificity (Mdn) [95% CrI] |

PPV (Mdn) [95% CrI] |

NPV (Mdn) [95% CrI] |

LR+ (Mdn) [95% CrI] |

LR− (Mdn) [95% CrI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >“Category 1” | 1.0 (1.0) [1.0, 1.0] |

0.314 (0.313) [0.220, 0.411] |

0.169 (0.169) [0.150, 0.190] |

1.0 (1.0) [1.0, 1.0] |

1.46 (1.46) [1.27, 1.68] |

0.0 (0.0) [0.0, 0.0] |

| >“Category 2” | 1.0 (1.0) [1.0, 1.0] |

0.477 (0.476) [0.372, 0.579] |

0.211 (0.210) [0.180, 0.247] |

1.0 (1.0) [1.0, 1.0] |

1.91 (1.91) [1.55, 2.32] |

0.0 (0.0) [0.0, 0.0] |

| >“Category 3” | 0.750 (0.810) [0.669, 0.948] |

0.895 (0.899) [0.833, 0.956] |

0.500 (0.580) [0.438, 0.730] |

0.963 (0.965) [0.930, 0.993] |

7.17 (7.94) [3.72, 14.76] |

0.279 (0.212) [0.058, 0.373] |

| >“Category 4” | 0.250 (0.567) [0.509, 0.659] |

0.977 (0.980) [0.946, 1.00] |

0.600 (0.876) [0.717, 0.992] |

0.903 (0.902) [0.880, 0.933] |

10.75 (28.92) [5.05, 137.3] |

0.768 (0.443) [0.345, 0.504] |

Note. Values based off 12 individuals who were classified by the team psychologist as “above low risk” for suicide in the current sample. All values are presented as observed (Posterior Mdn) [95% CrI], with the posterior values derived from 5000 (stratified) Bayesian bootstrap resamples. Cutoffs represent the category in question and all those below it being classified as “low risk” and all those above it being classified as “above low risk” (e.g. “>Category 3” indicates that categories 4 and 5 are “above low risk” whereas categories 1–3 are low risk). PPV = Positive Predictive Value; NPV = Negative Predictive Value; LR+ = Positive Likelihood Ratio [Sensitivity/(1 – Specificity)]; LR− = Negative Likelihood Ratio [(1 – Sensitivity)/Specificity].

Discussion

We provided preliminary psychometric validation of the Suicide Assessment Kit-Modified Interview (SAK-MI; based on the Suicide Assessment Kit Suicide Risk Screener) (Deady et al., 2015), in a sample of autistic adults without co-occurring intellectual disability. Internal consistency for the four-item negative effect score was adequate, and this dimensional scale correlated as expected with relevant constructs. Most importantly, we demonstrated divergent, convergent, and predictive validity (sensitivity, specificity) for our ordinal SAK-MI category variable, with established scales and clinician assessment of suicide risk serving as criterion variables. Our findings support the use of the revised scoring algorithm: SAK-MI category was strongly correlated with C-SSRS severity, intensity, and behavior scores. Categories greater than “Category 3” (i.e. “Category 4/5”) were effective indicators of clinician designated risk (“low risk” vs “above low risk”), returning sensitivity and specificity of 0.750 and 0.895, respectively.

The SAK-MI represents our co-development of an instrument aimed at improving accessibility of clinical assessment of STB to autistic people who are at significantly increased risk of suicide compared to the general population (Huntjens et al., 2024; Mournet, Wilkinson, et al., 2023; Newell et al., 2023; O’Halloran et al., 2022; Santomauro et al., 2024). In addition to being tailored to use in a specific vulnerable population, the SAK-MI addresses the Joint Commission’s (2019) call for the use of structured, validated STB assessment instruments within clinical healthcare settings. Furthermore, our revision of the coding algorithm better aligns SAK-MI with recommendations against risk stratification (Carter & Spittal, 2018; O’Connor et al., 2013; Quinlivan et al., 2014).

In practice, while SAK-MI category is likely to be associated with future suicide risk (indeed, for the purposes of validating the scale we assessed predictive validity against clinician determined suicide risk), it is not intended to be used for prediction but to assess current levels of need to support current clinical decision making, prioritizing patient safety (Saab et al., 2022). Thus, we developed several “suggested actions” for each SAK-MI category aimed at assisting clinicians in determining an appropriate response following administration. For example, for people who fall in “Category 1” and for whom no STB is present, we suggest that at minimum, the individual should be monitored and assessed for possible depression depending on their responses (e.g. where negative affect is elevated; negative affect cutoffs of > 5 (sensitive cutoff) or > 8 (specific cutoff) can be used to predict a PHQ-9 score of ⩾ 10 in the current sample). For subsequent categories, suggested actions include investigating whether the individual might require therapeutic intervention (e.g. if STB are causing distress), developing a safety plan, providing resources (including crisis resources), contacting a family member or other support person, ensuring safety (e.g. if being released home), and potentially admitting to hospital and restricting access to means. We suggest that any response or next steps should be determined by, or in consultation with an appropriate clinician with training and experience in mental health management, including suicide risk. We further expect that any actions taken will be aligned with any government guidelines, professional association or licensing requirements, and organizational policies. In work currently underway, we have partnered with autistic people and professionals to develop suicide prevention training and policy guidelines that are aligned with current research and best practice recommendations, which will support implementation of SAK-MI in clinical settings.

SAK-MI addresses an urgent need for the development and rigorous psychometric validation of clinical assessment of STB co-developed with, and for use by the autistic population (Cassidy, Bradley, Bowen, et al., 2018; Cassidy et al., 2020, 2021; Hedley, Batterham, et al., 2023). SAK-MI extends previous research with autistic adults that has primarily focused on co-developing brief screeners for suicidal ideation within this population (Cassidy et al., 2021; Hedley, Batterham, et al., 2023; Williams et al., 2024); it provides clinicians with a comprehensive structured clinical assessment interview that includes review of risk and protective factors, STB history, supports, and presence of suicide plans, preparations, and access to means.

This is the first study to provide support for a clinical assessment interview that included autistic people with lived experience of STB in its development, aligning it with best practice guidelines (Nicolaidis et al., 2019; Staniszewska et al., 2017). Furthermore, the revisions (e.g. clarifying instructions, providing response exemplars, definitions of terms, use of visual analogue scales, and use of unambiguous concrete language) are likely to make SAK-MI accessible to other diverse clinical populations that similarly experience communication challenges. Examples include literal interpretation of language seen in people with schizophrenia (Rossetti et al., 2018), or impaired cognition and communication that may be experienced by people in acute suicidal crisis (Schuck et al., 2019). Indeed, the presence of co-occurring conditions in autism is not uncommon (Lai et al., 2019; Uljarević, Hedley, Cai, et al., 2020); rates of co-occurring psychiatric diagnoses in the present sample (e.g. depression/anxiety = 70.4%, ADHD = 31.6%) provide some support for the utility of SAK-MI in clinically diverse populations with complex psychiatric presentations.

Future research is needed that examines the usefulness of SAK-MI with different clinical populations, considerations for implementation, and evaluation of the utility of the instrument and suggested actions within different clinical settings. Given likely over-representation of autistic people within emergency department settings coupled with lack of training of healthcare professionals for suicide risk assessment is this population (Cervantes et al., 2024; Cervantes, Brown, & Horwitz, 2023; Cervantes, Li, et al., 2023), implementation of the SAK-MI could potentially reduce time in the emergency department by routing patients who are not in need of crisis services more efficiently to discharge (with appropriate supports).

Although developed as a clinical rather than a research tool, future research should also examine associations between the instrument and variables identified by current theories of suicide (e.g. thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness; Joiner, 2005). As mentioned above, some of this work is currently underway. Nonetheless, and until this research is complete, caution is needed with regards the application of SAK-MI in clinical settings and with populations other than intellectually able autistic adults as described here. A particularly relevant future direction will be determination of whether the measure is appropriate for autistic (and non-autistic) individuals with mild intellectual disability, who were intentionally excluded from the present study despite ostensibly experiencing STB at a similar rate to the autistic adults in the present sample.

Notably, participants were followed up for several months and repeatedly risk-assessed for STB by the research team’s registered psychologist. The use of repeated risk-assessment over time, which was used as the criterion standard for SAK-MI (in the absence of a more proximal but rare indicator such as suicide attempts or completed suicides during the study period), is a particular strength of the study. Other strengths of the study include the application of C-SSRS by trained administrators, use of both interview and self-report measures (consistent with a multi-trait, multi-method approach; Campbell & Fiske, 1959), medical review of STB codes, and implementation of a rigorous study risk management protocol (Byme et al., 2021; Hedley, Batterham et al., 2023; Hedley et al., 2021).

Despite these strengths, our study also has several limitations. We did not collect additional follow-up data concerning suicide attempts, an aspect that will need to be addressed in future studies. We also acknowledge that the different measures used to assess convergent validity captured STB within discrete and previous timeframes. Our sample, recruited initially from existing longitudinal data sets (Arnold et al., 2019; Richdale et al., 2022), may reflect bias. Participants were highly educated (85.2% completing post-secondary education) with more females than males. In addition, given the age span of participants and specific diagnoses reported (e.g. Asperger’s Syndrome), some would likely have been diagnosed under DSM-IV and others under DSM-5 diagnostic criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), which may further bias the sample due to different diagnostic systems. Importantly, we must acknowledge that the autistic population is highly heterogenous. Given our relatively small sample size for this preliminary validation study, we did not have the statistical power to consider how the measure might work differently based on sex or gender. Our sample represented a relatively small sub-group of autistic people without a co-occurring intellectual disability which is not representative of the entire autism spectrum. Future research utilizing a larger, more diverse sample will provide the opportunity to conduct a more detailed psychometric investigation of SAK-MI. This will also enable us to examine how different individual characteristics, such as demographic variables (e.g. age, sex/gender, racial/ethnic background, education level), co-occurring conditions (e.g. ADHD, personality pathology, bipolar disorder, borderline/mild intellectual disability), or suicide-related clinical factors (e.g. mental/physical pain, hopelessness, interpersonal connectedness, and suicide capability) (Klonsky et al., 2021) might differentially influence how the measure functions. Furthermore, individuals with moderate-to-profound intellectual disability would likely require a different approach to assess STB.

There is a need to validate whether the suggested clinical actions associated with each SAK-MI category are appropriate and lead to better clinical outcomes than other approaches (e.g. risk stratification). It is notable that ROC analyses indicated that SAK-MI category was not in full accordance with clinical judgment. Thus, reliance on a cutoff based on SAK-MI category would potentially result in a proportion of people experiencing some level of suicidal distress being “missed.” Indeed, while we present SAK-MI as a clinical assessment instrument that can be used to guide decision making concerning patient safety, there remain limitations and concerns around any form of categorical thresholds associated with suicide. Consistent with the Joint Commission (2019) guidelines, we contend that a structured assessment of STB using validated instruments in conjunction with clinical judgment is likely to produce the best outcomes for patients. Future research examining the added value of SAK-MI to clinical judgment, independent of clinical judgment, and other clinical use case scenarios, is required. Finally, as manual coding for SAK-MI is currently quite involved, further development of the tool involving an automated scoring system is currently underway and will be useful to ensure efficient and accurate coding, particularly in clinical inpatient settings.

Conclusion

SAK-MI represents the second instrument developed by our team designed to improve the accessibility of structured screening and assessment instruments for STB developed for autistic adults without co-occurring intellectual disability (see Hedley, Batterham, et al., 2023). Both instruments are non-proprietary and freely accessible. Because the original SAK is in clinical use by trained healthcare professionals within Australia (Deady et al., 2015), our hope is that the revised version will be readily adopted within the sector. Specifically, our intention is that SAK-MI can be administered by professionals working in the healthcare sector, who have some training in mental health assessment, including for suicide. Ideally, assessment would involve level 1 screening with a brief screener (e.g. SBQ-ASC; SIDAS-M; STUQ) (Cassidy et al., 2021; Hedley, Batterham, et al., 2023; Williams et al., 2024) to identify individuals experiencing some level of STB, followed by level 2 assessment with SAK-MI as part of a comprehensive clinical assessment. Our goal is that the combined use of psychometrically validated screening and assessment of STB will prevent unnecessary suicide deaths through elimination of missed detection of STB within this population (Dueweke & Bridges, 2018; Rybczynski et al., 2022). It is important to acknowledge that no instrument can definitively identify or rule out the risk of a future suicide attempt. Like any psychological assessment for use by trained clinicians, the SAK-MI should be used to complement rather than replace one’s clinical experience and professional judgment in determining the most appropriate means to support someone experiencing suicidal distress. By enhancing the evaluation of STB in autistic individuals with a systematic and standardized evaluation, we are hopeful that the SAK-MI will help clinicians ensure the safety of their suicidal autistic patients through the provision of appropriate supports and intervention.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-aut-10.1177_13623613241289493 for The Suicide Assessment Kit-Modified Interview: Development and preliminary validation of a modified clinical interview for the assessment of suicidal thoughts and behavior in autistic adults by Darren Hedley, Zachary J. Williams, Mark Deady, Philip J. Batterham, Simon M. Bury, Claire M. Brown, Jo Robinson, Julian N. Trollor, Mirko Uljarević and Mark A. Stokes in Autism

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-aut-10.1177_13623613241289493 for The Suicide Assessment Kit-Modified Interview: Development and preliminary validation of a modified clinical interview for the assessment of suicidal thoughts and behavior in autistic adults by Darren Hedley, Zachary J. Williams, Mark Deady, Philip J. Batterham, Simon M. Bury, Claire M. Brown, Jo Robinson, Julian N. Trollor, Mirko Uljarević and Mark A. Stokes in Autism

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants in this study for willingly sharing their experiences with us and the members of our autistic advisory group who contributed to this study and our broader research program. We also thank Kathleen Denney and Ensu Sahin for assisting with data collection and curation, and Phoenix Fox, Emma Gallagher, and Dr Susan M. Hayward for their valuable insights and contributions to the development of the SAK-MI.

Appendix 1

The Suicide Assessment Kit-Modified Interview (SAK-MI).

|

Appendix 2

The Suicide Assessment Kit-Modified Interview (SAK-MI) visual anologue scales. Scales.

|

Administration notes: Scales are recommended to be provided to clients prior to administration. Scale 1: 1, 2, 3, 4, 7a; Scale 2: 7c, 7d; Scale 3: 8c.

Appendix 3

The Suicide Assessment Kit-Modified Interview (SAK-MI) coding algorithm.

| Category/description | Coding | Suggested action |

|---|---|---|

| NEGATIVE AFFECT | • Sum first four items (0–4 scale for each item, total of 16 points) • Scores between 6–9 indicate possible depression (high sensitivity), 10+ indicate likely depression (high specificity) |

Monitor, assess for possible depression |

| CATEGORY 1 | ||

| History of suicidality absent, current stressors absent, ideation absent, support networks present, may have elevated negative affect score. | • Item 5 (Lifetime attempts) = “No” AND • Item 6 (Current stressor) = “No” OR < 3 stressors on item 6a endorsed) AND • Item 7 (Current ideation) = “No” AND • Item 10 (Support network) = “Yes” AND • Item 11 (Coping skills) identified. |

Monitor, assess for possible depression |

| CATEGORY 2 | ||

| Current low-level Suicidal Ideation (SI) in the absence of plan, reason to live present, support network and coping skills identified. | • Item 5 (Lifetime attempts) = “No”* AND • Item 6 (Current stressor) = “No” OR < 3 stressors on item 6a endorsed) AND • Item 7 (Current ideation) = “Yes” AND • Item 7a = “None of the time,” or “A little of the time,” AND • Item 7c = “Not strong at all” or “Somewhat strong” AND • Item 7d = “Not strong at all” or “Somewhat strong” AND • Item 8 (Plan) = “No” AND • Item 9 (Reasons to Live) identified AND • Item 10 (Support network) = “Yes” AND • Item 11 (Coping skills) identified. *Also code here if respondent has a history of a remote attempt (⩾ 2 years prior) in the absence of current SI or other risk factors. |

Monitor, assess for possible depression. Investigate therapeutic intervention based on client preference and level of distress caused by ideation. |

| CATEGORY 3 | ||

| Presence of Suicidal Ideation (SI) with additional risk factors, some protective factors present, support network present. | • Item 7 (Current ideation) = “Yes” AND any of the following • Item 7a = “Some of the time” • Item 7c = “Strong” • Item 7d = “Strong” • 3 + stressors endorsed on item 6a, • Item 8 (Plan) must be “No” (if plan, automatically high risk), • Item 5 (Lifetime attempts) = “No” ○ or 1 attempt at least 1 year in the past allowed in this category; past-year attempt automatically Category 4 or Category 5, • Must still have 2/3 protective factors, • Item 9 (Reasons to Live) identified, • Item 10 (Support network) = “Yes” • Item 11 (Coping skills) identified. |

Monitor, assess for possible depression. Investigate therapeutic intervention based on client preference and level of distress caused by ideation. Discuss developing a safety plan and provide resources. |

| CATEGORY 4 | ||

| Presence of Suicidal Ideation (SI), history (HX) of attempts (maybe recent or multiple past attempts), presence of plan, few protective factors, support network not identified. | • Item 7 (Current ideation) = “Yes” AND any of the following: • Item 7a = “Most of the time” or “All of the time” • Item 7c = “Very strong” • Item 7d = “Very strong” • Recent attempt within past year (item 5b) and/or multiple past attempts (item 5a) • Item 8 (Plan) = “Yes” ○ includes detailed answers for items 8a (i) and/or 8b (i) (specific plan and location) and/or means that are accessible at some point in the future (item 8a (ii)) • 0 or 1 protective factors • Item 9 (Reasons to Live) not identified AND • Item 10 (Support network) = “No” AND • Item 11 (Coping skills) not identified. |

Develop a safety plan and provide crisis resources. Discuss safety if returned home, consider informing family member or other support person if there are any safety concerns. |

| CATEGORY 5 | ||

| Presence of plan, preparations, maybe unwilling to disclose details of plan, absence of protective factors or support network, unable to identify any reason to live. | • Item 8 (Plan) = “Yes” AND any of the following • Unwilling to disclose details of suicide plan (items 8a/b (i)) • Item 8b (finished making preparations) = “Yes” • No protective factors • Item 9 (Reasons to Live) not identified AND • Item 10 (Support network) = “No” AND • Item 11 (Coping skills) not identified |

Admit to hospital. Monitor and restrict access to means. |

Footnotes

Author contributions: Conceptualization: D.H., J.R., J.N.T., M.U., M.A.S.; Data curation: D.H.; Formal analysis: Z.J.W.; Funding acquisition: D.H., J.R., J.N.T., M.A.S.; Investigation: D.H., S.M.B., M.A.S.; Methodology: D.H., Z.J.W., M.D., P.J.B., J.R., J.N.T., M.U., M.A.S.; Project administration: D.H., M.A.S.; Writing––original draft: D.H., Z.J.W.; Writing––review and editing: D.H., Z.J.W., M.D., P.J.B., S.M.B., C.M.B., J.R., J.N.T., M.U., M.A.S.

Data Access: Requests for access to the data sample should be directed to Darren Hedley, PhD, Olga Tennison Autism Research Centre, School of Psychology and Public Health, La Trobe University, Melbourne 3086, VIC, Australia; e-mail: d.hedley@latrobe.edu.au.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by Untapped Holdings and Suicide Prevention Australia National Suicide Prevention Research Fellowships awarded to D.H. and C.M.B. M.U. was supported by a Discovery Early Career Researcher Award from the Australian Research Council (DE180100632). Z.J.W. is supported by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (grant F30-DC019510) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (grant T32-GM007347). J.R. is funded by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Investigator Grant (GNT2008460) and a University of Melbourne Dame Kate Campbell Fellowship. J.N.T. is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Investigator Grant (GNT2009771). We acknowledge Dr Joanne Ross and Professor Shane Darke for their roles in developing the original Suicide Assessment Kit Suicide Risk Screener, which was funded by the Australian Government Department of Health. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and final responsibility for the decision to submit the report for publication. Some of the data reported in this study have been published elsewhere (Hedley, Batterham, et al., 2023; Hedley et al., 2021). This study was preregistered with the Center for Open Science (Hedley, Williams, et al., 2023), see https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/K9BSG for full registration details.

Ethical approval: The research was approved by La Trobe University Human Research Ethics Committee HEC20235. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from participants after the nature of the study was explained.

Language Use: In this manuscript, we use identity-first language as it is the preference of the study advisory group as well as that of the study’s autistic authors. Research also reveals a preference for identity-first language (Bury et al., 2023; Kenny et al., 2016). We acknowledge that some people with lived experience of autism prefer person-first language.

ORCID iDs: Darren Hedley  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6256-7104

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6256-7104

Zachary J. Williams  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7646-423X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7646-423X

Simon M. Bury  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1273-9091

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1273-9091

Julian N. Trollor  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7685-2977

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7685-2977

Mark A. Stokes  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6488-4544

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6488-4544

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold S. R. C., Foley K.-R., Hwang Y. I., Richdale A. L., Uljarevic M., Lawson L. P., Cai R. Y., Falkmer T., Falkmer M., Lennox N. G., Urbanowicz A., Trollor J. (2019). Cohort profile: The Australian Longitudinal Study of Adults with Autism (ALSAA). BMJ Open, 9(12), Article e030798. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold S. R. C., Uljarević M., Hwang Y. I., Richdale A. L., Trollor J. N., Lawson L. P. (2020). Brief report: Psychometric Properties of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) in autistic adults. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(6), 2217–2225. 10.1007/s10803-019-03947-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodfish J. W., Symons F. J., Parker D. E., Lewis M. H. (2000). Varieties of repetitive behavior in autism: Comparisons to mental retardation. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30(3), 237–243. 10.1023/A:1005596502855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongiovi-Garcia M. E., Merville J., Almeida M. G., Burke A., Ellis S., Stanley B. H., Posner K., Mann J. J., Oquendo M. A. (2009). Comparison of clinical and research assessments of diagnosis, suicide attempt history and suicidal ideation in major depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 115(1–2), 183–188. 10.1016/j.jad.2008.07.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C. M., Newell V., Sahin E., Hedley D. (2024). Updated systematic review of suicide in autism: 2018-2024. Current Developmental Disorders Reports. Advance online publication. 10.1007/s40474-024-00308-9 [DOI]

- Bürkner P.-C. (2017). brms: An R package for Bayesian multilevel models using Stan. Journal of Statistical Software, 80(1), 1–28. 10.18637/jss.v080.i01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bürkner P.-C. (2018). Advanced Bayesian multilevel modeling with the R package BRMS. The R Journal, 10(1), 395–411. https://journal.r-project.org/archive/2018/RJ-2018-017/index.html [Google Scholar]

- Bury S. M., Jellett R., Spoor J. R., Hedley D. (2023). “It defines who I am” or “It’s something I have”: What language do [autistic] Australian adults [on the autism spectrum] prefer? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 53(2), 677–687. 10.1007/s10803-020-04425-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byme S. J. E. B., Lamblin M., Pirkis J., Mihalopoulos C., Spittal M. J., Rice S., Hetrick S., Hamilton M., Yuen H. P., Lee Y. Y., Boland A., Robinson J. (2021). Study protocol for the Multimodal Approach to Preventing Suicide in Schools (MAPSS) project: A regionally-based trial of an integrated response to suicide risk among secondary school students. Research Square. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-518233/v1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Camm-Crosbie L., Bradley L., Shaw R., Baron-Cohen S., Cassidy S. (2019). ‘People like me don’t get support’: Autistic adults’ experiences of support and treatment for mental health difficulties, self-injury and suicidality. Autism, 23(6), 1431–1441. 10.1177/1362361318816053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell D. T., Fiske D. W. (1959). Convergent and discriminant validation by the multi-trait-multimethod matrix. Psychological Bulletin, 56, 81–105. 10.1037/h0046016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter G., Spittal M. J. (2018). Suicide risk assessment. Crisis, 39(4), 229–234. 10.1027/0227-5910/a000558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy S., Bradley L., Bowen E., Wigham S., Rodgers J. (2018). Measurement properties of tools used to assess suicidality in autistic and general population adults: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 62, 56–70. 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]