Abstract

Recent studies suggest that the human microbiome influence tumor development. Endometrial carcinoma (EC) is the sixth most common malignancy in women. Recent research has demonstrated the microbes play a critical role in the development and metastasis of EC. However, it remains unclear whether intratumoral microbes are associated with tumor microenvironment (TME) and prognosis of EC. In this study, we collected the EC microbiome data from cBioPortal and constructed a prognostic model based on Resident Microbiome of Endometrium (RME). We then examined the relationship between the RME score, immune cell infiltration, immunotherapy-related signature, and prognosis. The findings demonstrated the independent prognostic value of the RME score for EC. The group with low RME scores had higher enrichment of immune cells. Drug sensitivity analysis revealed that the RME score may serve as a potential predictor of chemotherapy efficacy. In conclusion, our research offers new perspectives on the relationships between tumor immunity and microbes.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12672-025-02038-9.

Keywords: Microbiome, Endometrial cancer, Prognostic biomarkers, Tumor immune microenvironment

Introduction

Endometrial cancer (EC) is the sixth most common cancer among women, with a global incidence of 417,000 cases and a mortality rate of 97,000 in 2020 [1]. It is also the second most prevalent gynecological malignancy in China [2]. While most patients with EC are diagnosed at an early stage and benefit from effective treatment, those with advanced EC often cannot be cured [3, 4]. Therefore, it is critical to identify novel molecular factors that can serve as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for EC, as well as potential therapeutic targets.

Microbiota has emerged as novel regulators of tumorigenesis and biomarkers for many cancers [5]. Microorganisms can contribute to tumor progression by increasing mutations, regulating oncogenes or carcinogenic mutations, or regulating the host immune system [6–9]. For example, Wang et al. demonstrated that Fusobacterium nucleatum induces chemoresistance in colorectal cancer by inhibiting pyroptosis though the Hippo pathway [10]. Fusobacterium nucleatum could bind to the inhibitory receptor TIGIT on T cells and human natural killer (NK) cells, thereby promoting immune evasion in colon cancer [11]. Additionally, some invasive Campylobacter species could promote tumor progression by inducing an IL18-driven pro-inflammatory response [12, 13].

For a long time, it was thought that the uterus was a sterile organ. With the development of sequencing technology, it has been shown that the uterus has its own microbial composition. Sola-Leyva et al. described the presence of a variety of active microorganisms in addition to bacteria in the endometrium, such as fungi, viruses, and archaea [14]. Walther-Antonio et al. found that specific bacteria, such as Firmicutes, Spirochaetes, Actinobacteria, and Proteobacteria, were found in women with EC, suggesting that different microbiota may play a role in carcinogenic conditions in the uterus [15]. However, microbiome signatures and EC prognosis, as well as the mechanism by which they may affect the tumor immune microenvironment, still require further investigation.

In this study, our propose was to develop a comprehensive and novel prognostic model based on Resident Microbiome of Endometrium (RME) to explore the relationship between the microbiome and tumor immunity, as well as to predict the prognosis of patients with endometrial cancer and the effectiveness of immunotherapy and chemotherapy, which can provide a new sight to understand the disease progression of and interventions for patients with endometrial cancer.

Materials and methods

Datasets and data preprocessing

Clinical information and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data for EC samples were acquired from the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database. Microorganism quantification data was obtained from the cBioPortal database. 502 EC samples with an overall survival (OS) of over 1 month were retained for this research.

Construction of microbial abundance prognostic scoring model

Candidate microbial signatures that were substantially related to the OS of patients were chosen by univariate Cox regression analysis (p < 0.01). Multivariate Cox regression analysis was later applied to screen for microbial prognostic signatures that independently impact OS (p < 0.05). Ultimately, each patient's RME score was determined through a linear combination of the multivariate Cox regression coefficient and the abundance of OS-associated microbes [16]. All patients were divided into the group with low RME scores and group with high RME scores based on the median of the RME scores. ROC was utilized to evaluate the performance of prognostic RME model for predicting survival.

Immune infiltration analysis

To characterize the landscape of tumor microenvironment in patients with the group with low RME scores and group with high RME scores, we introduced matched tumor RNA-seq data for the two groups. The “xcell” approach in the “immunedeconv” package was utilized for calculating the enrichment scores of infiltrating immune cells. Immune-related signatures were gathered from previously released research [17], and the ssGSEA was employed to calculate the enrichment scores for immune function.

Construction of TF-IRG networks

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the two groups were identified by “DESeq2” package. Differentially expressed transcription factors (DETFs) and immune-related genes (DEIRGs) were extracted from lists acquired from the ImmPort along with Cistrome Cancer databases and the correlation between them was calculated (Supplementary Tables S1, S2). Correlation coefficients greater than 0.3 (or less than − 0.3) and adjusted p < 0.01 were regarded as significantly correlated.

Evaluation of the therapeutic efficacy

Tumor mutation burden (TMB) was evaluated through R package “maftools”. The MSI data of EC patients was obtained from previously published study [18]. We downloaded the immunophenotype score (IPS) of patients with EC from the TCIA database for predicting immunotherapy sensitivity. The “pRRophetic” R package was applied to perform drug sensitivity prediction analysis and determine the IC50 value for common chemotherapeutic drugs.

Statistical and computational analysis

All of the analysis was performed using R (version 4.1). The Wilcoxon test was employed to determine the significant differences between the two groups for continuous variables. When comparing more than two groups, the Kruskal–Wallis test was employed for comparison. The Kaplan–Meier method with log-rank tests was utilized to compare the survival curves for the prognostic analysis. Spearman's correlation analysis was applied to calculate correlation coefficients, and differences were deemed statistically significant when p < 0.05.

Results

Microbiome signatures were associated with EC prognosis

To investigate the prognostic value of microbiome signature of patients with EC, we downloaded the complete abundance data for all 1406 genera from cBioPortal. First, utilizing univariate Cox regression analysis, we found 130 genera significantly associated with overall survival (OS) in EC patients (Fig. 1A). The majority of these microorganisms were considered as favorable factors (HR < 1; p < 0.05). Then, with the multivariate Cox regression to identify 9 OS-related genera that independently affect OS (Fig. 1B). Among them, 7 genera, namely Zooshikella, Caldimonas, Candidatus_Accumulibacter, Nonlabens, Roseiflexus, Streptosporangium, Zavarzinella were associated with favorable OS, while Derxia and Shigella were associated with poorer survival. Furthermore, we constructed a prognostic model based on Resident Microbiome of Endometrium (RME) to evaluate patient mortality risk based on a linear combination of the multivariate Cox regression coefficients and the abundance of the aforementioned 9 microbial genera. Patients were categorized into the group with low RME scores and group with high RME scores according to the median of the RME scores and survival comparison were conducted. As shown in Fig. 1C, group with high RME scores had shorter overall survival (OS) compared to those with low RME scores. The AUCs of 1-, 3- and 5-year OS predicted by the RME scores were 0.741, 0.709, and 0.694, respectively (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

Construction of the prognostic RME model for prognosis of EC patients. A Volcano plot of the candidate microbial signatures that significantly associated with OS by univariate Cox regression. B Forest plot of the microbial prognostic signatures that independently impact OS by multivariate Cox regression. C Kaplan–Meier OS curve of the prognostic RME model. D ROC illustrated the performance of the prognostic RME model for predicting the 1-, 3- and 5-year OS rate

The prognostic RME model was an independent prognostic indicator of EC patients

To assess the independent prognostic value of the prognostic RME model, we conducted univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses, incorporating additional clinical characteristics such as stage and age. The results indicated that the RME model was an independent predictor of survival in patients with EC (Fig. 2A, B). We also examined the relationship between the RME score and clinical features. The analysis showed that there was no statistically significant difference in age and stage (Fig. 2C, D). We combined clinical factors and the RME score to develop a nomogram survival model for predicting the survival of EC patients at 1, 3, and 5 years (Fig. 2E). The nomogram model's C-index value was 0.796. Simultaneously, the calibration curves for the probabilities of 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS exhibited that the observed OS and the nomogram-predicted OS agreed well (Fig. 2F).

Fig. 2.

Relationship between the RME score and clinical features of EC patients. A Univariate Cox regression analyses to verify the prognostic values of various clinicopathological factors and the RME score. B Multivariate Cox regression analyses to verify the prognostic values of various clinicopathological factors and the RME score. C Boxplots showed the correlation between the RME score and age. D Boxplots showed the correlation between the RME score and stage. E Nomogram models based on clinical factors with the RME score to predict the 1-, 3- and 5-year OS probability of EC patients. F The calibration curve of the model to evaluate prediction accuracy for OS of EC patients

Joint analysis revealed potential immune-microbe interactions

We also investigated the interactions between microbes and the human immune system. Using the ImmPort database, we identified 70 immune-related differentially expressed genes (DEIRGs) between the group with low RME scores and group with high RME scores (Fig. 3A). KEGG and GO enrichment analyses revealed that these DEGs are involved in the hormone signaling, cytokine-cytokine receptor interactions, and other related pathways (Fig. 3B, C). To investigate potential upstream regulatory mechanisms of DEIRGs, we identified 31 differentially expressed transcription factors (DETFs). Based on the correlation between the expression of DEIRGs and DETFs, we constructed a TF-IRG network (Fig. 3D). We found that two TF genes, SP7 and PROX1, were significantly elevated in the group with high RME scores. The expression of SP7 and PROX1 genes has been reported to promote tumor progression and play a negative role in immune cell regulation. Therefore, the regulatory network centered on SP7 and PROX1 may play an important role in immune infiltration and immune escape in the group with high RME scores [19, 20]. Immune cell infiltration analysis showed that T cells and NK cells were significantly enriched in the group with low RME scores (Fig. 3E). T cells and NK cells mediate anti-tumor immunity [21], which may explain the better survival of the group with low RME scores. Moreover, most immune-related pathway scores were significantly higher in the group with low RME scores, including cytotoxic activity and interferon response (Fig. 3F). These findings suggest that patients with low RME scores may exhibit higher immune infiltration. Due to the relatively low enrichment fraction of immune cells and immune-related pathway scores in the group with high RME scores, it shows that the group with high RME scores may be “cold tumor”.

Fig. 3.

Immune characteristics of different groups. A Volcano plot of the immune-related DEGs in tumors between the group with low RME scores and group with high RME scores. B GO enrichment analysis based on the immune-related DEGs. C KEGG enrichment analysis based on the immune-related DEGs. D A TF-IRG network in TCGA cohort. The pink line is the positive correlation between differentially expressed transcription factors (DETFs) and differentially expressed immune-related genes (DEIRGs). E Differences in xCell scores of immune cells between the group with low RME scores and group with high RME scores. F Relative enrichment score of 12 immune-related signatures in the group with low RME scores and group with high RME scores. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001

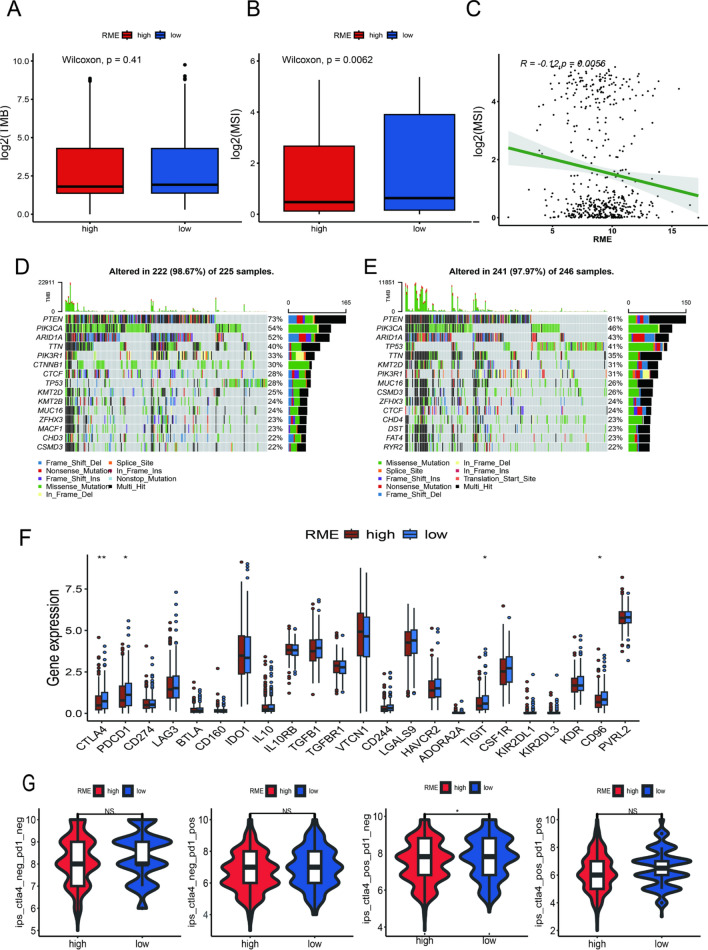

Mutation and immunotherapeutic responses of the two groups

Immunotherapy is an increasingly prevalent clinical strategy for treating cancer [22]. We aimed to explore the relationship between the RME scores and response to immunotherapy. TMB and MSI, genomic biomarkers, are reliable biomarkers of immunotherapy [23]. Our findings indicated that there was no statistically significant difference in TMB between the two groups. However, the group with low RME scores exhibited higher MSI (Fig. 4A, B). Subsequent correlation analysis revealed that MSI was negatively correlated with the RME scores (Fig. 4C). Somatic mutation analysis demonstrated that the group with low RME scores had a higher overall gene mutation load compared to the group with high RME scores (Fig. 4D, E). Given the critical role of immune checkpoints in tumor immunity, we also analyzed the differences in the immune checkpoint molecules expression and observed that PD-1, CD96, CD244 and CTLA-4 showed distinct expression level between the two groups (Fig. 4F). Additionally, we utilized the IPS file downloaded from the TCIA database to investigate the association between IPS and the RME scores, revealing that patients with low RME scores had higher IPS scores than those with high RME scores (Fig. 4G). The findings revealed that patients in the group with low RME scores may be appropriate candidates for immunotherapy.

Fig. 4.

Immunotherapeutic responses of the RME score. A, B TMB and MSI between the group with low RME scores and group with high RME scores. C The correlation between the MSI and RME score. D, E Waterfall plot of tumor somatic mutation in the group with low RME scores and group with high RME scores. F Comparison of immune checkpoints expression levels between the group with low RME scores and group with high RME scores. G Comparison of the immunophenoscore (IPS) between the group with low RME scores and group with high RME scores. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001

Chemotherapy response prediction

We utilized the “oncopredict” package to predict the IC50 value of each drug in patients with EC for investigating the association between chemotherapeutic drug sensitivity and the RME score. Our analysis revealed that the IC50 values of several drugs, including AZD1332 and JAK_8517 in the group with high RME scores were remarkably higher in comparison with those in the group with low RME scores, indicating that endometrial tumors with high RME scores were more resistant to these chemotherapy drugs (Fig. 5A, B). Conversely, the IC50 values for WEHI-539 and ULK1_4989 were notably higher in the group with low RME scores, indicating that these drugs may be more effective in the endometrial tumors with high RME scores (Fig. 5C, D). Additionally, we found that Roseiflexus was associated with the effect of Foretinib, and Dabrafenib, which could help personalize chemotherapy predictions (Fig. 5E, F).

Fig. 5.

Drug sensitivity. A–D Boxplots and correlation plots of the comparison in IC50 values of AZD1332 (A), JAK_8517 (B), WEHI-539 (C), ULK1_4989 (D) between the group with low RME scores and group with high RME scores. ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05. E, F Boxplots and correlation plots of the comparison in IC50 values of Foretinib (E), Dabrafenib (F) between the roseiflexus -high and roseiflexus -low groups

Discussion

Recent findings suggest that the intratumor microbiota is widely present in a variety of tumor types and can influence tumor progression to some extent. For instance, intra-tumor microbial communities have been shown to promote metastasis and colonization in breast cancer [24]. The intratumor microbiota plays an immunomodulatory role within TME, influencing tumor outcome by promoting inflammatory responses or modulating anti-tumor activity [25]. Moreover, the intratumor microbiota significantly impacts therapeutic outcomes, offering new insights for cancer treatment, diagnosis, prognosis assessment, and potential therapeutic targets.

Traditionally, the uterus was thought to be sterile. However, advances in detection technology have revealed that the endometrium hosts its own resident microbiota community [26, 27]. Endometrial carcinoma represents a significant global health issue for women, making the study of the microbiota within this context crucial. Currently, there are limited studies on the characteristics of the endometrial carcinoma microbiome and its relationship with the immune microenvironment. In this study, we developed a prognostic RME model by identifying 9 OS-related microbes and assessed its independent prognostic value in EC patients. Among the 9 microbes identified, shigella is strongly associated with cancer in women [28], while the role of other microorganisms in the development of cancer remain unreported yet. Furthermore, we explored the correlation between the tumor microenvironment and the RME score. Lastly, we proposed that the RME score might serve as a potential biomarker for sensitivity to immunotherapy and chemotherapy in EC patients. Our findings provide a new insight into relationship between intratumor microbiota, tumor prognosis, and the immune microenvironment.

It is highly interesting to characterize the microbiome and the underlying mechanism in cancer patients. In our study, we found that T and NK cells were enriched in the group with low RME scores. These immune cells are known to kill tumor cells through antibody-dependent cytotoxicity, perforin release, and granzyme [29, 30].The TF-IRG regulatory network also indicates some potential mechanism by which microbial signature influence tumor immune cell infiltration. SP7 and PROX1 play a key role in regulating tumor growth and treatment resistance in the tumor microenvironment (TME) by regulating cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) [19, 20]. Although no significant enrichment of CAFs in the group with high RME scores was found in this paper, the potential mechanism by which the two transcription factors regulate the tumor microenvironment is still worthy of further investigation in future studies. Previous reports have shown that BPIFB2 gene, which is highly expressed in “cold tumors”, can inhibit the expression of CCL5 by activating STAT3, thereby inhibiting tumor cells’ chemotactic immune molecules to T cells [31]. In addition, we found that most genes were highly expressed in the group with low RME scores. It has been reported that CDH5 can promote the immune response of CD8 + T cells in TME, and may play an important role in anti-tumor immunity [32, 33]. In conclusion, the construction of the TF-IRG network reveals some insights into the interaction between TME and the RME scores in EC.

Immunotherapy has transformed the treatment landscape for EC, especially for patients with mismatch repair abnormalities [34]. Increasing evidence supports the use of immunotherapy in combination with chemotherapy as a first-line treatment approach. However, not all patients benefit from these therapies, highlighting the urgent need to identify new prognostic biomarkers. We investigated whether the prognostic scores identified in this study could help predict sensitivity to chemotherapy or immunotherapy. Our findings indicate the group with low RME scores had higher MSI and PD1 expression, which may indicate that this group may respond better to immunotherapy. In addition, we identified several promising small molecule compounds. WEHI-539 binds to the BH3 domain of BCL2L1 and trigger BAK-dependent apoptosis in BCL2L1-dependent cancer cells [35]. Foretinib inhibits cancer stemness by decreasing CD44 and c-MET signaling [36]. Dihydrorotenone inhibits Twist1 expression in cancer-associated fibroblasts, thereby inactivating them and reducing tumor development [37]. Dabrafenib is a potent tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKIs) of the BRAF V600E kinase, targeting the treatment of BRAF mutated cancer patient populations [38]. These results suggest that these potential drugs may provide new insights into the treatment of patients with EC.

Despite the good performance of the prognostic RME model in prognostic prediction of EC patients, this study still has some limitations. First, additional prospective studies are needed to validate the clinical cohort derived from public databases. Furthermore, while our study briefly examined the relationship between the microbiome features of EC, the tumor microenvironment, and prognosis, further research is necessary to establish causation and explore the potential mechanisms involved.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

YY and YM drafted the manuscript. YY and ZX contributed to the data collection and analysis. YZ and LX designed and supervised this study. QZ and ML participated in the modification of the article pictures. FK and SZ participated in the revision of the article. Authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was funded by Shanghai Municipal Health Commission, 20214Y0226, Sunshine Clinical Research Incubator Program, 2024CRTS045, 2024CRTS017, 2024CRTS015, Kangda College, Nanjing Medical University (KD2021KYJJZD094,KD2022KYCXTD008).

Data availability

All data are available in a public, open access repository. The data collected and analysed in this study are available in the cBioPortal database and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yuting Yang and Yuchen Meng have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Xinling Li, Email: ntlxl@163.com.

Yihua Zhu, Email: 11507039@zju.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–49. 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zheng RS, Zhang SW, Sun KX, et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2016. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2023;45:212–20. 10.3760/cma.j.cn112152-20220922-00647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anker MS, Holcomb R, Muscaritoli M, et al. Orphan disease status of cancer cachexia in the USA and in the European Union: a systematic review. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2019;10:22. 10.1002/jcsm.12402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Makker V, Rasco D, Vogelzang NJ, et al. Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab in patients with advanced endometrial cancer: an interim analysis of a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:711–8. 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30020-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matson V, Chervin CS, Gajewski TF. Cancer and the microbiome—influence of the commensal microbiota on cancer, immune responses, and immunotherapy. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:600–13. 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.11.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dzutsev A, Badger JH, Perez-Chanona E, et al. Microbes and cancer. Annu Rev Immunol. 2017;35:199–228. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-051116-052133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garrett WS. Cancer and the microbiota. Science. 2015;348:80. 10.1126/science.aaa4972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramírez-Labrada AG, Isla D, Artal A, et al. The influence of lung microbiota on lung carcinogenesis, immunity, and immunotherapy. Trends Cancer. 2020;6:86–97. 10.1016/j.trecan.2019.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong-Rolle A, Wei HK, Zhao C, Jin C. Unexpected guests in the tumor microenvironment: microbiome in cancer. Protein Cell. 2020;12:426. 10.1007/s13238-020-00813-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang N, Zhang L, Leng X-X, et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum induces chemoresistance in colorectal cancer by inhibiting pyroptosis via the Hippo pathway. Gut Microb. 2024;16:2333790. 10.1080/19490976.2024.2333790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gur C, Ibrahim Y, Isaacson B, et al. Binding of the Fap2 protein of Fusobacterium nucleatum to human inhibitory receptor TIGIT protects tumors from immune cell attack. Immunity. 2015;42:344–55. 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaakoush NO, Castaño-Rodríguez N, Man SM, Mitchell HM. Is Campylobacter to esophageal adenocarcinoma as Helicobacter is to gastric adenocarcinoma? Trends Microbiol. 2015;23:455–62. 10.1016/j.tim.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaakoush NO, Deshpande NP, Man SM, et al. Transcriptomic and proteomic analyses reveal key innate immune signatures in the host response to the gastrointestinal pathogen Campylobacter concisus. Infect Immun. 2015;83:832–45. 10.1128/IAI.03012-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sola-Leyva A, Andrés-León E, Molina NM, et al. Mapping the entire functionally active endometrial microbiota. Hum Reprod Oxf Engl. 2021;36:1021–31. 10.1093/humrep/deaa372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walther-António MRS, Chen J, Multinu F, et al. Potential contribution of the uterine microbiome in the development of endometrial cancer. Genome Med. 2016;8:122. 10.1186/s13073-016-0368-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deng X, Chen X, Luo Y, et al. Intratumor microbiome derived glycolysis-lactate signatures depicts immune heterogeneity in lung adenocarcinoma by integration of microbiomic, transcriptomic, proteomic and single-cell data. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1202454. 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1202454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bindea G, Mlecnik B, Tosolini M, et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of intratumoral immune cells reveal the immune landscape in human cancer. Immunity. 2013;39:782–95. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thorsson V, Gibbs DL, Brown SD, et al. The immune landscape of cancer. Immunity. 2018;48:812. 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ricci B, Tycksen E, Celik H, et al. Osterix-Cre marks distinct subsets of CD45- and CD45+ stromal populations in extra-skeletal tumors with pro-tumorigenic characteristics. Elife. 2020;9: e54659. 10.7554/eLife.54659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lai S-W, Cheng Y-C, Kiu K-T, et al. PROX1 interaction with α-SMA-rich cancer-associated fibroblasts facilitates colorectal cancer progression and correlates with poor clinical outcomes and therapeutic resistance. Aging (Albany NY). 2024;16:1620–39. 10.18632/aging.205447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paijens ST, Vledder A, de Bruyn M, Nijman HW. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in the immunotherapy era. Cell Mol Immunol. 2021;18:842–59. 10.1038/s41423-020-00565-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y, Zhang Z. The history and advances in cancer immunotherapy: understanding the characteristics of tumor-infiltrating immune cells and their therapeutic implications. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020. 10.1038/s41423-020-0488-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palmeri M, Mehnert J, Silk AW, et al. Real-world application of tumor mutational burden-high (TMB-high) and microsatellite instability (MSI) confirms their utility as immunotherapy biomarkers. ESMO Open. 2022;7:100336. 10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fu A, Yao B, Dong T, et al. Tumor-resident intracellular microbiota promotes metastatic colonization in breast cancer. Cell. 2022;185:1356-1372.e26. 10.1016/j.cell.2022.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu J, Zhang P, Mei W, Zeng C. Intratumoral microbiota: implications for cancer onset, progression, and therapy. Front Immunol. 2024;14:1301506. 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1301506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koedooder R, Mackens S, Budding A, et al. Identification and evaluation of the microbiome in the female and male reproductive tracts. Hum Reprod Update. 2019;25:298–325. 10.1093/humupd/dmy048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heinonen PK, Teisala K, Punnonen R, et al. Anatomic sites of upper genital tract infection. Obstet Gynecol. 1985;66:384–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Siddiqui R, Makhlouf Z, Alharbi AM, et al. The gut microbiome and female health. Biology. 2022;11:1683. 10.3390/biology11111683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.St Paul M, Ohashi PS. The roles of CD8+ T cell subsets in antitumor immunity. Trends Cell Biol. 2020;30:695–704. 10.1016/j.tcb.2020.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma S, Caligiuri MA, Yu J. Harnessing IL-15 signaling to potentiate NK cell-mediated cancer immunotherapy. Trends Immunol. 2022;43:833–47. 10.1016/j.it.2022.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang J, Ping Y, Zhao Q, et al. BPIFB2 is highly expressed in “cold” lung adenocarcinoma and decreases T cell chemotaxis via activation of the STAT3 pathway. Mol Cell Probes. 2022;62:101804. 10.1016/j.mcp.2022.101804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Y, Wu Q, Lv J, Gu J. A comprehensive pan-cancer analysis of CDH5 in immunological response. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1239875. 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1239875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu L, Shao F, Luo T, et al. Pan-cancer analysis identifies CHD5 as a potential biomarker for glioma. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:8489. 10.3390/ijms23158489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bogani G, Monk BJ, Powell MA, et al. Adding immunotherapy to first-line treatment of advanced and metastatic endometrial cancer. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2024;35:414–28. 10.1016/j.annonc.2024.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chiou J-T, Lee Y-C, Wang L-J, Chang L-S. BCL2 inhibitor ABT-199 and BCL2L1 inhibitor WEHI-539 coordinately promote NOXA-mediated degradation of MCL1 in human leukemia cells. Chem Biol Interact. 2022;361:109978. 10.1016/j.cbi.2022.109978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sohn S-H, Kim B, Sul HJ, et al. Foretinib inhibits cancer stemness and gastric cancer cell proliferation by decreasing CD44 and c-MET signaling. OncoTargets Ther. 2020;13:1027–35. 10.2147/OTT.S226951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee E, Yeo S-Y, Lee K-W, et al. New screening system using Twist1 promoter activity identifies dihydrorotenone as a potent drug targeting cancer-associated fibroblasts. Sci Rep. 2020;10:7058. 10.1038/s41598-020-63996-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hanrahan AJ, Chen Z, Rosen N, Solit DB. BRAF—a tumour-agnostic drug target with lineage-specific dependencies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2024;21:224–47. 10.1038/s41571-023-00852-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in a public, open access repository. The data collected and analysed in this study are available in the cBioPortal database and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.