Abstract

Autophagy is a natural process in which the cell degrades substances through the lysosomal pathway. One of the most studied mechanisms for regulating autophagy is the mTOR signaling pathway. Recent research has shown that the 5-HT6 receptor is linked to the mTOR pathway and can affect cognition in various neurodevelopmental models. Therefore, developing 5-HT6 receptor antagonists could improve cognition by inducing autophagy through the inhibition of the mTOR pathway. Our study reports two in-house-designed 5-HT6R antagonists, PUC-10 and its indazole analogue PUC-55, that induce mTOR-dependent autophagy. PUC-10, an indole-based 5-HT6 receptor antagonist with high binding affinity (Ki = 14.6 nM) and antagonist potency (IC50 = 32 nM), demonstrated more than 90% at 25 µM cellular viability and a high capacity to induce autophagy in the neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cell line. Similarly, its indazole analogue, PUC-55 (Ki = 37.5 nM), exhibited high cellular viability and potent autophagy-inducing activity. Both compounds induced overexpression of the 5-HT6 receptor after 24 h of stimulation, contrasting with the effects observed with Rapamycin (100 nM), a well-known mTOR inhibitor. Additionally, the signaling pathway was characterized, showing that both PUC-10 and PUC-55 induce autophagy by inhibiting the mTOR pathway, suggesting their potential therapeutic applications for neurological disorders.

Keywords: 5-HT6R, Modulators, mTOR, Autophagy

Subject terms: Drug discovery, Neurology

Introduction

The human serotonin receptor subtype 6 (5-HT6R) belongs to the class A family of G protein-coupled transmembrane receptors1,2. The 5-HT6 receptor has emerged as a key player in neural development, regulating various steps involved in neural circuit assembly including neuronal migration, neurite outgrowth, and neuronal differentiation3. Expression of the 5-HT6 receptor is primarily confined to the limbic and cortical regions within the central nervous system. The regions with the highest receptor densities are associated with mnemonic functions, including the striatum, olfactory tubercle, nucleus accumbens, hippocampus, and cerebral cortex4–6. In these regions, the receptor is predominantly, but not exclusively, situated on the primary cilium of neurons.

An important feature of the 5-HT6 receptor is its high level of constitutive activity, which has been established not only for recombinant receptors expressed in transfected cells, but also for native receptors present in cultured neurons and mouse brains7,8. 5-HT6R is positively coupled to Gαs subunits, thereby stimulating adenylate cyclase and increasing cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) production, which results in the depolarization of neurons9,10. This G protein-coupled pathway is recognized as its primary canonical signal transduction pathway2. Moreover, the 5-HT6 receptor is also associated with alternative signaling pathways, which partially explain some of the effects and functions in which it has been implicated3. For example, 5-HT6 receptor stimulation induces the activation of the Erk1/2 MAP kinase pathway11,12. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that among the novel transduction pathways engaged by the 5-HT6 receptor C-terminal domain, Cdk5 binds to 5-HT6 receptors in an agonist-independent manner to promote neurite growth, but this interaction is effectively disrupted upon treatment with a 5-HT6 receptor antagonist13. Furthermore, the characterization of the 5-HT6R interactome reveals that this receptor interacts with several proteins within the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway14,15. mTOR serves as a central regulator for a wide range of cellular processes, including autophagy, where it acts as a negative master regulator16–18. Autophagy is a highly conserved physiological process of cellular degradation and recycling in eukaryotic cells. Cells degrade damaged organelles, macromolecular aggregates, and pathogens, collectively referred to as autophagic cargo, via the lysosomal pathway to maintain energy, metabolic, and protein homeostasis19–21. These autophagy functions appear to be linked to a range of human diseases, including cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and infections among others22,23. In this regard, the mTORC1 pathway plays a critical role in processes such as neuronal migration, dendritic tree formation, and dendritic spine morphogenesis. Moreover, this non-canonical pathway has been linked to cognitive deficits in rodent models for schizophrenia, which can be reversed by using the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin and 5-HT6R antagonists24. Non-physiological activation of mTOR can lead to various neurodevelopmental disorders25–27. For instance, excessive activation of mTORC1 in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) results in increased spine density, impaired developmental spine pruning in pyramidal neurons, overproduction of synaptic proteins, and reduced autophagy. Available evidence strongly suggests that mTOR-regulated autophagy is essential for developmental spine pruning28,29, and activation of neuronal autophagy has been shown to ameliorate synaptic pathology and improve social behavior deficits in neurodevelopmental disease models characterized by hyperactivated mTOR. Thus, the inhibition of the mTOR signaling pathway through 5-HT6R antagonism holds promise as a potential therapeutic intervention30–32. Herein, we describe two novel in-house designed and synthesized 5-HT6R antagonists that induce potent autophagy by inhibiting mTOR signaling through the non-canonical pathway.

Materials and methods

Shape and electrostatic based design

2-(4-(2-methoxyphenyl)piperazin-1-yl)-1-(1-(naphthalen-1-ylsulfonyl)-1H-indazol-3-yl)ethan-1-ol (PUC-55) was identified through a shape and electrostatic similarity search of our in-house compound database. The search was conducted using the ROCS and EON protocols33,34, based on our predicted binding mode of 2-(4-(2-methoxyphenyl)piperazin-1-yl)-1-(1-(naphthalen-1-ylsulfonyl)-1 H-indol-3-yl)ethan-1-ol (PUC-10) on the 5-HT6 receptor35. OMEGA v4.2.2.1 was used to generate a conformational ensemble for PUC-55, and the AM1BCC charges were assigned using QUACPAC v2.2.2.136,37. For the ROCS screening, we selected the PUC-10 binding mode at the 5-HT6 receptor to generate the ROCS model. We used TanimotoCombo as a scoring parameter, which considers both ShapeTanimoto (molecular shape overlay) and ColorTanimoto (chemical functionality overlaps). We then analyzed the aligned conformation of PUC-55 for electrostatic similarity with the EON v2.2.0.2 program38. We used the ET_Comb score, which is a combination of ShapeTanimoto (ST) and PB Electrostatic Tanimoto (ET_pb) score, to calculate the similarity of PUC-55 with PUC-10. Molecular properties (pKa, logP, logD and Polarizability) were calculated using MarvinSketch v23.17 (ChemAxon Ltd., www.chemaxon.com). ADME/Tox predictionS were computed using the SwissADME server39.

Syntheses and characterization procedures

All organic solvents used in the synthesis were of analytical grade. All reagents used were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), Merck (Kenilworth, NJ, USA) or AK Scientific (Union City, CA, USA) and were used as received. NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker APC-200 at 200.0 MHz for 1H and 50.0 MHz for 13C-NMR or on a Bruker Avance III HD 400 (Billerica, MA, USA) at 400.1 MHz for 1H and 100.6 MHz for 13C-NMR using the solvent signal (CDCl3 or DMSO-d6) as reference. The chemical shifts are expressed in ppm (δ scale) downfield from tetramethyl silane (TMS). Multiplicity is given as follows: s, singlet; bs, broad singlet; d, doublet; t, triplet; td, triplet of doublets; m, multiplet. Coupling constants values (J) are given in Hertz. The 1H and 13C NMR spectra of compound 7 are available in the ESI. For compound 7 high resolution mass spectra was obtained on high resolution mass spectrometer Exactive™ Plus Orbitrap (ThermoFisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) using electron impact ionization (available in the ESI). For compounds 2–6 high resolution mass spectra were obtained on high resolution mass spectrometer Bruker Compact QTOF (Billerica, MA, USA) using electron impact ionization. Measurements were performed in positive or negative ion mode, as indicated in each case. Column chromatography was performed on Merck silica gel 60 (70–230 mesh). Thin layer chromatographic (TLC) separations were performed on Merck silica gel 60 (70–230 mesh) chromatofoils.

1H-indazole-3-carboxylic acid (2): A solution of indazole (0.35 g, 3 mmol), 3,4-dihydropyran (DHP) (0.8 mL, 9 mmol), and pyridinium p-toluenesulfonate (PPTS) (0.22 g, 0.9 mmol) in 50 mL of dichloromethane (DCM) was stirred at room temperature (rt) until complete consumption of the starting material (progress was monitored by TLC). The reaction was quenched by the addition of 50 mL of a saturated NaHCO3 solution and then extracted using 3 × 20 mL DCM. The organics were dried with anhydrous MgSO4 and concentrated. The resulting white solid was placed in a round bottom flask, flushed by argon, and diluted with 40 mL of anhydrous tetrahydrofuran (THF). The system was then cooled to -80 °C using a mixture of liquid nitrogen and ethyl acetate, followed by the dropwise addition of n-Butyllithium (n-BuLi) (1.28 mL, 2.5 M in hexane). After 1 h of stirring (the solution turned from white to dark pink, indicating complete lithiation), CO2 was bubbled into the reaction for 1 h, maintaining the temperature below − 78 °C. The reaction was quenched by adding 40 mL of water, and the organic phase was extracted using ethyl acetate (3 × 15 mL). The aqueous phase was then acidified to pH 3 by adding 1 N HCl, and the resulting solid was filtered and dried under vacuum, yielding compound 2 as a white solid (0.43 g, 88%).

1H-NMR (200 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 13.87 (s, 1H); 8.08 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H); 7.64 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H); 7.42 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H); 7.27 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H). 13C-NMR (200 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 163.94, 141.17, 136.00, 126.62, 122.70, 122.43, 121.32, 11.16.

HRMS calculated for [C8H7N2O2]+ [M + H+]: 163.0502; Found: 163.0505.

N-methoxy-N-methyl-1H-indazole-3-carboxamide (3): 1H-indazole-3-carboxylic acid (1 g, 6.17 mmol) and a magnetic stirrer were placed in a round bottom flask. The system was sealed with a septum and placed under an argon atmosphere. Anhydrous dimethylformamide (DMF) (10 mL) was injected, and the system was stirred until complete dissolution was achieved. Then, 1,1’-carbonyldiimidazol (CDI) (1.1 g, 6.78 mmol) was added in one portion, and after 15 min, the system was allowed to stir at 65 °C for 2 h. Subsequently, N, O-dimethylhydroxylamine hydrochloride (1.05 g, 10.8 mmol) was added, dissolved in a minimal quantity of anhydrous DMF, and the system was allowed to stir at 65 °C overnight. The reaction was quenched by adding 50 mL of ice water and extracted with DCM (3 × 20 mL). The organic layers were dried and concentrated, and the resulting oil was poured into ice water, leading to the formation of an abundant white precipitate. The solid was filtered, washed with cold water, and dried in a vacuum oven to afford compound 3 (Scheme 1) as a white solid (1.2 g, 95%).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of Compound PUC-55 (7) Reagents and conditions: (i) (a) DHP, PPTS, DCM, rt, 12 h; (b) n-BuLi, THF(anh), -78 °C; (c) CO2; (ii) N,O-dimethylhydroxylamine hydrochloride, CDI, DMF(anh), 65 °C, overnight; (iii) CH3MgBr, THF (anh), -78 °C, 2 h; (iv) CuBr2, ethyl acetate, reflux, 2 h; (v) 1-(2-methoxyphenyl)piperazine, K2CO3, acetone, rt, 1 h; (vi) (a) naphthalene-1-sulfonyl chloride, TEA, DMAP, DCM, rt, 2 h; (b) NaBH4, EtOH, 1 h, rt.

1H-NMR (200 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 13.65 (s, 1H, ); 7.99 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H); 7.64 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H); 7.41 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, ); 7.28 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H); 3.75 (s, 3 H); 3.45 (s, 3 H). 13C-NMR (200 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 163.50, 140.85, 137.89, 127.29, 123.12, 122.71, 121.78, 111.18, 61.63, 35.29. HRMS calculated for [C10H12N3O2]+ [M + H+]: 206.0924; Found: 206.0932.

1-(1H-indazol-3-yl)ethan-1-one (4): N-methoxy-N-methyl-1H-indazole-3-carboxamide (1 g, 4.87 mmol) and a magnetic stirrer were placed in a round bottom flask. The system was sealed and flushed with argon, followed by the addition of anhydrous THF (10 mL). Subsequently, the system was cooled to -80 °C using a mixture of liquid nitrogen and ethyl acetate, followed by the dropwise addition of a 3 M solution of methyl magnesium bromide in THF (24.35 mmol). The mixture was stirred for 1 h at -80 °C and then allowed to reach rt. The reaction was quenched with a saturated solution of ammonium chloride (10 mL) and extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 10 mL). The organic layers were dried and concentrated to afford compound 4 (Scheme 1) as a white solid (0.78 g, 100%).

1H-NMR (200 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 13.84 (s, 1H); 8.18 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H); 7.66 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H); 7.43 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H); 7.30 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H); 2.63 (s, 3 H). 13C-NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 194.53, 142.88, 141.31, 126.88, 123.42, 121.59, 121.09, 111.04, 26.63. HRMS calculated for [C9H7N2O]− [M - H+]: 159.0553; Found: 159.0566.

2-bromo-1-(1H-indazol-3-yl) ethan-1-one (5): 1-(1H-indazol-3-yl) ethan-1-one (0.2 g, 1.25 mmol), copper dibromide (0.64 g, 2.75 mmol) and ethyl acetate (40 mL) were placed in a round bottom flask. The system was allowed to stir at reflux for 2 h and then cooled to rt. Subsequently, the crude mixture was filtered over a celite pad, washing with ethyl acetate, and the filtrate was treated with 30 mL of a saturated sodium sulfite solution. The mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 20 mL), and the organic layers were dried and concentrated. The crude product was then purified by column chromatography (DCM/n-hexane/acetone 4:2:0.2), affording compound 5 (Scheme 1) as a white solid (0.18 g, 60%).

1H-NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 14.08 (s, 1H); 8.16 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H); 7.71 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H); 7.49 (ddd, J = 8.3; 6.9; 1.2 Hz, 1H); 7.36 (ddd, J = 8.3; 6.9; 1.2 Hz, 1H); 4.90 (s, 2 H). 13C-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 187.44; 141.21; 140.17; 127.17; 123.87; 121.39; 121.13; 111.29; 33.00. HRMS calculated for [C9H8BrN2O]+ [M + H+]: 238.9815; Found: 238.9828.

1-(1H-indazol-3-yl)-2-(4-(2-methoxyphenyl)piperazin-1-yl)ethan-1-one (6): 2-bromo-1-(1H-indazol-3-yl)ethan-1-one (0.5 g, 2.09 mmol), 1-(2-methoxyphenyl)piperazine (0.4 gr, 2.09 mmol), potassium carbonate (0.87 g, 6.27 mmol), and acetone (50 mL) were placed in a round bottom flask. The mixture was stirred at rt for 1 h and then the crude product was concentrated and re-dissolved in a 50% mixture of ethyl acetate and water (50 mL). The organic layers were extracted with ethyl acetate (2 × 30 mL), dried, and concentrated, yielding compound 6 (Scheme1) as a white solid (0.75 g, 100%).

1H-NMR (200 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 13.89 (s, 1H); 8.19 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H); 7.68 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H, ); 7.46 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H); 7.33 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H); 6.96–6.84 (m, 4 H); 4.07 (s, 2 H); 3.76 (s, 3 H); 2.99 (bs, 4 H); 2.75 (bs, 4 H). 13C-NMR (200 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 193.26; 152.09; 141.89; 141.38; 141.10; 126.99; 123.52; 122.48; 121.46; 121.31; 120.93; 118.05; 111.97; 111.13; 62.67; 55.39; 53.16 (2 C); 50.18 (2 C). HRMS calculated for [C20H23N4O2]+ [M + H+]: 351.1816; Found: 351.1821.

2-(4-(2-methoxyphenyl)piperazin-1-yl)-1-(1-(naphthalen-1-ylsulfonyl)-1 H-indazol-3-yl)ethan-1-ol (7): In a round bottom flask, 1-(1 H-indazol-3-yl)-2-(4-(2-methoxyphenyl)piperazin-1-yl)ethan-1-one (0.1 g, 0.28 mmol), naphthalene-1-sulfonyl chloride (0.07 g, 0.3 mmol), triethylamine (TEA) (0.09 mL, 0.64 mmol), 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) (0.017 g, 0.14 mmol) and DCM (25 mL) were placed. The mixture was stirred at rt for 2 h, and then quenched by the addition of 25 mL of water. Subsequently, the organics were extracted with DCM (2 × 25 mL), dried, and quickly concentrated (the ketone intermediate is highly unstable). The resultant crude product was quickly dissolved in a 22 mL mixture of ethanol/DCM 10:1, and once complete dissolution was achieved, sodium borohydride (0.02 g, 0.56 mmol) was added portion-wise. The mixture was stirred for 1 h and then quenched by the addition of 20 mL of water. After that, ethanol was evaporated, and the resultant residue was extracted with DCM (3 × 20 mL), dried, and concentrated. The crude product was then purified by column chromatography eluting with n-hexane/ethyl acetate 3:2, yielding compound 7 as a white solid (0.14 g, 88%).

1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 8.90 (dd, J = 8.6 and 1.0 Hz, 1H); 8.36 (dd, J = 7.5; 1.3 Hz, 1H); 8.08 (d, J = 8.6 and 0.9 Hz, 1H); 7.95 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H); 7.90 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H); 7.75 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H); 7.51 (ddd, J = 8.6, 6.9 and 1.5 Hz, 1H); 7.47–7.40 (m, 3 H); 7.22–7.16 (m, 1H); 6.94 (ddd, J = 8.0; 6.2; 2.8 Hz, 1H); 6.88–6.82 (m, 2 H); 6,79 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H); 5.08 (dd, J = 10.1; 4.0 Hz, 1H); 3.79 (s, 3 H); 2.99 (bs, 4 H); 2.85–2.77 (m, 2 H); 2.78–2.66 (m, 2 H); 2.58–2.51 (m, 2 H). 13C-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 152.82; 152.26; 141.08; 141.03; 135.94; 134.17; 133.19; 130.46; 129.25; 128.83; 128.52; 128.40; 127.22; 125.16; 124.35; 124.07; 123.96; 123.18; 122.58; 121.00; 118.23; 113.14; 111.20; 65.00; 62.39; 55.42; 53.22 (2 C); 50.70 (2 C). HRMS calculated for [C30H31N4O4S]+ [M + H+]: 543.2061; Found: 543.2095.

Radioligand binding assays

The affinity of PUC-55 for the 5-HT6 receptor was evaluated using membranes from HEK-293 cells expressing human 5-HT6 receptors and [125I]-SB-258,585 as the iodinated specific radioligand (Kd = 1.3 nM; 2200 Ci/mmol). A competitive inhibition assay was performed according to standard procedures as previously reported35,40. Briefly, 45 µL fractions of diluted 5-HT6 membrane preparation were incubated at 27 ºC for 180 min with 25 µL of [125I]-SB-258,585 (0.2 nM) and 25 µL of WGA-coated polyvinyltoluene (PVT) scintillation proximity assay (SPA) beads (4 mg/mL) in the presence of increasing concentrations (10− 11 to 10− 4M) of the competing drug (5 µL) or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), in a final volume of 100 µL of assay buffer (50 mM Tris, 120 mM NaCl, pH 7.4). Nonspecific binding was determined by radioligand binding in the presence of a saturating concentration of 100 µM of clozapine. The binding of [125I]-SB-258,585 to 5-HT6 receptors directly correlated with an increase in the signal read on a Perkin Elmer Topcount NXT HTS. The compound was tested at eight concentrations in triplicate. Clozapine was used as an internal standard for comparison. The data generated were analyzed using Prism software (GraphPad Inc). A linear regression line of data points was plotted, from which the IC50 value was determined, and the Ki value was calculated based on the Cheng–Prusoff equation. In this assay, the IC50 value of Clozapine (Clz) was 9.47 nM; Ki = 9.12 nM.

Cell culture and stimulation

The human neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y was maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 0.37% sodium bicarbonate, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. All cell cultures were maintained at 37ºC in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator and handled under sterile conditions. PUC-10 and PUC-55 were dissolved in DMSO at a concentration of 5 mM for stock solutions. Rapamycin (Sigma-Aldrich, #553210) was also dissolved in DMSO at a concentration of 2 mM for a stock solution. For treatments, cells were seeded in sterile cell culture plates and allowed to grow for 24 h as described above. After 24 h, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then exposed to the stimuli for 24 h, with PUC-10, PUC-55, and Rapamycin diluted in culture medium in the appropriate concentrations (5 µM, 10 µM and 25 µM for PUC-10 and PUC-55, and 100 nM for Rapamycin). All experiments included plates with no treatment, containing only culture medium (as a control group), and a positive control for autophagy induction using Rapamycin.

Cell viability

Cell viability was assessed using the colorimetric MTT reduction assay. Cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 5 × 103 cells/well and allowed to grow for 24 h. Following the incubation period, cells were treated with three concentrations of PUC-10 and PUC-55 in triplicate for additional 24 h. One hour before concluding the treatment, a positive control for cell death was performed by adding 100 µL of a 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) solution to the cells. After completing the treatments, 100 µL of a 0.5 mg/mL MTT solution (ThermoFisher #M6494) were added to each well and incubated at 37 °C for four hours. Following the incubation, 100 µL of a 10% SDS solution in 0.1 M HCl was added to each well and incubated overnight at 37 °C. The absorbance of each well was measured using the EPOCH microplate reader (Biotek, USA) at a wavelength of 570 nm.

Results are expressed as the percentage of MTT reduction, with the absorbance of the negative control for cell death set as 100%.

Evaluation of autophagy induction by Immunofluorescence

To assess the formation of autophagosomes through LC3-II expression detection, cells were seeded onto coverslips placed in 12-well plates and allowed to grow for 24 h, maintaining confluences between 20 and 40% once adhered. After the 24 h, cells were treated with PUC-10 and PUC-55 at a concentration of 25 µM for an additional 24 h. Following the treatment period, cells were fixed and stained with a solution containing 4% paraformaldehyde and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (1:1000) for 20 min in the dark at rt. The cells were then washed with 2 mM PBS-Glycine, permeabilized with 0.1% PBS-Triton X-100 for 10 min, and blocked with 3% PBS-Bovine serum albumin (BSA) for one hour at rt. After blockage, cells were incubated with the LC3A/B primary antibody (1:400, Cell Signaling #CS4108) in a closed and humid container overnight at 4 °C. Following incubation with the primary antibody, cells were incubated with the Alexa Fluor™ 488 secondary antibody (1:600, Life Technologies #A11034) for one hour at rt in a closed and humid container. Then, slides were prepared with one drop of mounting medium (Dako, S3023) and left to dry at rt while protected from light. Once dry, coverslips were sealed onto the slides with clear nail lacquer. Fluorescence microscopy images were captured using the Cytation™ 5 equipment (Biotek, USA), utilizing DAPI and green fluorescent protein (GFP) filters at a magnification of 20x. For subsequent image analysis, cells presenting fluorescent dots representing autophagosomes (green dots-GFP-LC3) were considered positive for autophagy induction and counted. Additionally, the total number of cells with nuclear DAPI staining was determined by counting the number of nuclei. The presence and number of autophagosomes per cell were analyzed using the 3D Object Counter accessory in ImageJ software (NIH).

Protein levels determination by Western blot

Whole-cell lysates were obtained by scraping the cells with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. The total volume of cell lysate was collected and centrifuged at 12,500 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C to remove insoluble material. The resultant supernatant was recovered, and the micro-bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (ThermoFisher, USA) was used for protein quantification by measuring absorbance in the EPOCH microplate reader (Biotek, USA) at a wavelength of 562 nm. Subsequently, equal amounts of lysate protein were loaded and separated on 6% and 12% SDS-PAGE gels. Proteins then were electro transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane, and the membrane was blocked in 3% BSA in tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBS-T) for one hour. After blockage, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with the following primary antibodies: LC3A/B, mTOR, p-mTORSer2448, ULK1, p-ULK1Ser757, BECN1, p-BECN1Ser30, SQSTM1/p62, GAPDH from Cell Signaling, and 5-HT6 from Origene. The membranes were then washed with 0.1% TBS-T, and secondary antibody was added and incubated for one hour at rt. Signals were detected with the EZ-ECL kit (Sartorius AG, Germany) and quantified by densitometry using the C-Digit Blot Scanner (LI-COR, USA).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 9 software (GraphPad Software, Inc, San Diego, USA). Quantified data are expressed as the mean ± SEM of three or more independent experiments. The data were first subjected to a ROUT outliers test (Q = 1%), and then statistically assessed for differences between the means of all groups using a one-way ANOVA test, followed by Tukey’s post-test. Statistically significant differences were considered when the p-value < 0.05. A 95% CI of difference, F-values, R-squared values, and degrees of freedom (DF) are presented for each analysis.

Results

Shape and electrostatic-based design

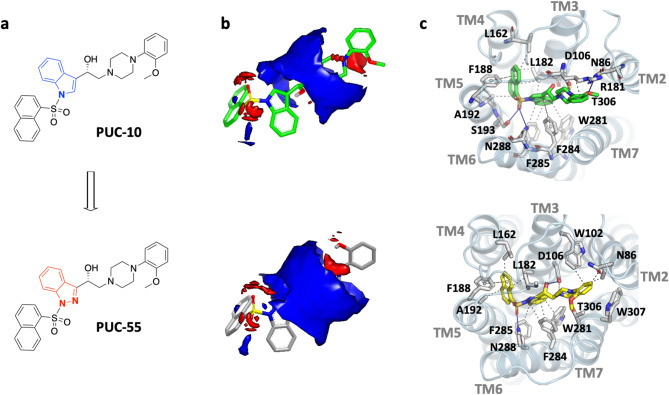

We have previously reported a series of ligands for the 5-HT6 receptor belonging to the extended pharmacophore of general structure N-arylsulfonylindole. These ligands showed moderate to high binding affinity at the receptor35,40. Among these ligands, PUC-10 was found to be the most potent, with a Ki of 14.6 nM. We used shape-based and electrostatic similarity search to screen an in-house library of indazole analogs of PUC-10 (Fig. 1). As a result, PUC-55 was identified with a TanimotoComboScore of 1.616, which included a ShapeTanimoto (shape) similarity of 0.909 and a ColorTanimoto (chemical features) similarity of 0.707. An ElectrostaticTanimoto score of 0.833 was estimated using an outer dielectric of 80. Comparative docking indicates that PUC-55 has a predicted affinity similar to that of PUC-10. The FRED ChemGauss Score for PUC-10 was − 17.271, while that for PUC-55 was − 16.478. In both cases, the naphthalene ring occupied the hydrophobic groove delimited by transmembrane helices (TMH) 3 to 6, forming aliphatic interactions with residues L162, L182, F188, and A192. The sulfonyl group formed hydrogen bonds with S193 and N288. The indole and indazole nuclei were flanked by aromatic residues W281, F284, and F285, while the β-amino alcohol moiety formed hydrogen bonds and electrostatic interactions with residue D106. The 2-methoxyphenyl group interacted with N86 and T306 through hydrogen bond interactions or aliphatic interactions with the side chains of residues W102, W307, or R181. No significant differences were found in the estimated molecular properties between PUC-55 and PUC-10. For instance, the pKa values were 7.62 and 7.95, the logP values were 4.34 and 4.88, the logD values were 3.91 and 4.22, and the polarizability values were 58.95 and 59.4, respectively. All predicted properties indicate that PUC-55 may have a similar biological activity as compared to PUC-10, with potentially better pharmacokinetic properties.

Fig. 1.

Computer-Aided Design of PUC-55. (a) Structure of 5-HT6 ligands PUC-10 and PUC-55. The modification introduced to the indole nucleus of PUC-10 is shown in red, resulting in the indazole derivative PUC-55. (b) The Electrostatic Similarity Potentials of PUC-10 and PUC-55 were compared. Red areas indicate electronegative regions, while blue areas indicate electropositive regions. (c) The predicted binding modes of PUC-10 and PUC-55 at the 5-HT6 receptor were analyzed. PUC-55 displayed a high degree of shape and electrostatic similarity, as well as similar binding modes and interactions to PUC-10.

Synthesis

The synthesis of the indazole analog 7 (PUC-55, Scheme 1), began with the commercially available indazole 1, which was regioselectively protected using DHP in mild acidic conditions to achieve 100% of the kinetic isomer N2 protected. The N2 tetrahydropyran (THP) intermediate was then metalated in a regioselective manner at the C-3 position using n-BuLi in dry THF, followed by the bubbling of CO2 gas to produce compound 2 in excellent yield. Subsequently, the carboxylic acid contained in compound 2 was activated using CDI and converted to the respective Weinreb amide 3 by the insertion of dimethylhydroxylamine hydrochloride.

The intermediate 3 was smoothly converted into ketone 4 by treating it with an excess of methyl magnesium bromide in dry THF. In the next step, alpha bromination of the ketone 4 using cooper dibromide in ethyl acetate yielded brominated compound 5 in moderate yield. This compound was then used in the subsequent step to incorporate the methoxyphenyl piperazine moiety through nucleophilic substitution, promoted by a potassium carbonate-acetone system, yielding compound 6 quantitatively. Finally, analog 7 was synthesized through a one pot, two step sequence. This involved the regioselective N1 protection of intermediate 6 using naphthalene-1-sulfonyl chloride, TEA, and a catalytic amount of DMAP in DCM, followed by the immediate reduction of the highly unstable ketone using sodium borohydride in ethanol (Scheme 1).

Radioligand binding assay

Afterwards, the indazole PUC-55 (7) underwent radioligand displacement binding studies to determine whether the structural change influenced receptor binding compared to the indole compound PUC-10. We utilized [125I]-SB-258,585, an iodinated piperazinyl benzene sulphonamide compound with a Kd of 1.3 nM, as a selective radioligand for 5-HT6 receptors. PUC-55 was tested as a free base at eight concentrations in triplicate, spanning a concentration range from 10− 4 M to 10− 11 M, to obtain the dose-response curve, determine the half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) value, and calculate the inhibitory constant (Ki) value. Under these experimental conditions, PUC-55 exhibited an IC50 of 39 nM (Ki = 37.5 nM), indicating a high affinity for the receptor. In fact, the Ki value of PUC-55 indicates a slightly higher affinity for the receptor 5-HT6 than that reported for the endogenous ligand 5-HT (Ki = 75 nM)41.

Cytotoxicity Evaluation of Novel PUC-10 and PUC-55 in SH-SY5Y Cell Lines.

To assess the potential cytotoxicity of the compounds, we conducted a screening to determine the survival of SH-SY5Y cells against three concentrations of each compound: 5 µM, 10 µM and 25 µM for 24 h. A control group was also included to evaluate cell survival against the solvent. Upon stimulation with the compounds at different concentrations, no significant differences in cell survival were found compared to the control group (Fig. 2). Therefore, none of the proposed compounds are cytotoxic at 5 µM, 10 µM, or 25 µM, as cells displayed survival rates exceeding 90% after being treated with the compounds for 24 h at all the concentrations tested. No significant differences in cell viability were observed when substituting indole with indazole across the concentrations and administration schedule employed in this study. In silico ADME/Tox predictions suggest that PUC-10 and its indazole analogue PUC-55 demonstrate moderate oral bioavailability, high gastrointestinal absorption, and the ability to penetrate the blood–brain barrier, which are essential characteristics for CNS-targeted 5-HT6 receptor antagonists. Despite both compounds having borderline molecular weights (> 500 g/mol), their consensus logP values (~ 3.8–4.3) indicate adequate membrane permeability for brain penetration. Preliminary assays in zebrafish larvae exposed to 2–50 µM of PUC-10 for 48 h demonstrated approximately 85% viability, indicating low acute toxicity (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

PUC-10 and PUC-55 do not induce cytotoxicity in SH-SY5Y cell lines at micromolar concentrations. An MTT assay was performed to assess the effects of PUC-10 and PUC-55 at three concentrations: 5 µM, 10 µM, and 25 µM, over a 24-hour period. Graphs are the quantification of 3 different experiments. Statistical analysis was conducted using one-way ANOVA.

Autophagosome formation in SH-SY5Y cells after PUC-10 and PUC-55 treatment

In the context of autophagy, the LC3 protein is one of the most widely used markers. The phosphatidylethanolamine (PE)-conjugated LC3-II form is associated with the autophagosome membrane from its formation to its maturation with lysosomes and subsequent degradation in autolysosomes, making it one of the most abundant structural components42. Immunofluorescence microphotographs against LC3-II of cells treated with PUC-10 and PUC-55 at a concentration of 25 µM, compared to untreated cells and cells treated with Rapamycin at a concentration of 100 nM, are shown in Fig. 3. The analysis of LC3-positive cells displaying a punctate pattern indicates that PUC-10 and PUC-55 compounds significantly differ from the control group in terms of the percentage of cells with autophagosomes (Fig. 3A). Particularly, an increase in the number of cells presenting autophagosomes was evident after treatment with PUC-10 or PUC-55, with a significantly higher percentage compared to the control (Fig. 3B). Moreover, no significant differences were found when comparing the compounds to Rapamycin, a positive control for autophagy induction through mTOR inhibition.

Fig. 3.

PUC-10 and PUC-55 induce autophagosome formation in SH-SY5Y cell line. SH-SY5Y cells were stimulated with PUC-10 or PUC-55 at 25 µM for 24 h. Positive and negative controls for autophagy were included, corresponding to Rapamycin (100 nM) and untreated cells, respectively. Each condition is presented with GFP and DAPI staining, as well as an overlay of both for autophagosome analysis. N = 4. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA, with the following results (A) F-Value 10.23, R-square 0.7932, DF = 8; (B) F-Value 53.77, R-square 0.9527, DF = 8.

For a more thorough analysis of the induction of autophagy, the total number of autophagosomes per cell was analyzed. Notably, upon treatment with PUC-10 and PUC-55 a significant increase in the number of autophagosomes per cell compared with their respective control groups was observed (Fig. 3A). These findings suggest that cells treated with PUC-10 and PUC-55, at a concentration of 25 µM for 24 h, exhibit an increased number of autophagosomes per cell together with the increase in the number of cells undergoing autophagy, as Rapamycin did.

Autophagy induction by PUC-10 and PUC-55 is dependent on 5-HT6R-mTOR signaling

To study the induction of autophagy through antagonism of the 5-HT6 receptor, we verified the presence of this receptor, both at basal levels (control group) and after treatment with Rapamycin, PUC-10, and PUC-55, in the SH-SY5Y cell line. Figure 4 shows a representative results of protein levels, where a band of approximately 50 kDa, corresponding to 5-HT6R is observed after the incubation with the anti-5-HT6R (OriGene TA326141) antibody. Through densitometric analysis, we determined that the expression levels of 5-HT6R increases significantly when treated with PUC-10 and PUC-55, in contrast to the treatment with Rapamycin, which did not modify the expression levels of 5-HT6R (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Protein levels of the 5-HT6 receptor in SH-SY5Y cell line increase in the presence of PUC-10 and PUC-55. Cells were treated with PUC-10, PUC-55, and Rapamycin for 24 h, and protein levels of the 5-HT6R were assessed. The increase in 5-HT6R levels after treatment with PUC-10 and PUC-55 supports the antagonism of both the indole and indazole compounds. Graph is the quantification of 3 different experiments. ns = non-significant. One-way ANOVA, F-Value 9.562, R-square 0.7819, DF = 8. Exact p-values are shown.

Once the expression levels of 5-HT6R were determined under different conditions, we proceeded to quantify the effects of 5-HT6R antagonism on the levels of the main proteins involved in the autophagic process (LC3 and p62) (Fig. 5A-B) and specifically in the mTOR-dependent pathway (mTOR, p-mTOR, ULK1, p-ULK1, BECN1, and p-BECN1) (Fig. 6A). Regarding LC3 levels, treatment with Rapamycin, PUC-10, and PUC-55 significantly increased total LC3-II levels compared to the control (Fig. 5C). Additionally, these same groups demonstrated a significant increase in the LC3-II/LC3-I ratio (Fig. 5D), indicating an increase in the conversion of LC3-I to LC3-II. Conversely, p62 levels were significantly decreased in these groups (Fig. 5E), serving as an indicator of autophagic activity.

Fig. 5.

Protein levels in the common autophagy pathway. Cells were treated with PUC-10, PUC-55, and Rapamycin for 24 h. Representative images showing the modification of protein levels involved in the autophagy pathways are presented. Quantification and analysis were performed using Graphpad Prism. The graphs presented are the quantification of 3 different experiments. One-way ANOVA results are as follows: (C) F-Value 9.701, R-squared 0.7844, DF = 8; (D) F-Value 14.71, R-squared 0.8465, DF = 8; (E) F-Value 8.751, R-squared 0.7664, DF = 8. Exact p-values are shown.

Fig. 6.

mTOR-Dependent Autophagy Induction After PUC-10 and PUC-55 Treatment. Cells were treated with PUC-10, PUC-55, and Rapamycin for 24 h. Protein levels and phosphorylation involved in mTOR autophagy pathways were determined by Western Blot, and representative images are shown in (A). Graphs are the quantification of 3 different experiments. Quantification by densitometry was performed. Both PUC-10 and PUC-55 treated cells showed similar levels of mTOR inhibitor when compared to Rapamycin-treated cells (B–G). One-way ANOVA results are as follows: (B) F-Value 12.39, R-squared 0.8229, DF = 8; (C) F-Value 10.25, R-squared 0.7934, DF = 8; (D) F-Value 8.067, R-squared 0.7516, DF = 8.

On the other hand, regarding changes in protein phosphorylation involved in the mTOR pathway, treatment with Rapamycin, PUC-10, and PUC-55 significantly decreases phosphorylated levels of mTOR (Ser2448) (Fig. 6B) and ULK1 (Ser757) (Fig. 6C) compared to the control. In contrast, phosphorylated levels of BECN1 (Ser30) were significantly increased in these groups (Fig. 6D). Moreover, an induction in the phosphorylation of mTOR downstream protein 4EBP, can also be determined after PUC-10 and PUC-55 incubation (available in the ESI). Given the above, our overall results suggests that the 5-HT6R antagonists of N-arylsulfonylindole/indazole structures presented in this work induce autophagy through the inhibition of the mTOR transduction pathway where this effect could be mediated by the non-canonical signaling of 5HT6R and its constitutive activity.

Discussion

In the context of developing new molecules for neurological disorders, 5-HT6R is a significant pharmacological target due to its involvement in various physiological processes. Given its distribution in both the CNS and at the neuronal level, as well as its role in modulating different neurotransmissions, it has been suggested that this receptor could be implicated in the regulation of higher-order cognitive processes, mood, motivated behaviors, and even in neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric diseases. This makes 5-HT6R an appealing therapeutic target for treating CNS disorders, with a low likelihood of peripheral adverse effects43,44. In relation to this, multiple preclinical and clinical studies have shown that the administration of 5-HT6 receptor antagonists improves cognition in models of depression, schizophrenia, and even dementia associated with Alzheimer’s disease, positioning these antagonists as promising drugs for treating cognitive impairment. Furthermore, multiple preclinical studies have also indicated that other pathologies, such as other types of progressive dementing disorders, obesity, and epilepsy, could also be susceptible to treatment with 5-HT6R ligands1,45.

Recently, studies based on in silico analysis of various compounds, including natural ones, have shown that their potential may be involved in the antagonism of this receptor for its therapeutic effect46. Our previous results indicate that the N-aryl sulfonamide structure present in PUC-10 represents a privileged structural framework with an extended pharmacophore, where the aryl portion attached to the piperazine ring can occupy a second hydrophobic pocket not previously described. In this context, the central indole ring would act as a hinge between the pharmacophoric elements most relevant to the activity. This leads us to propose modifying this central nucleus to optimize certain properties without negatively affecting the receptor binding exhibited by PUC-10. To this end, we aimed to introduce a more polar heterocyclic central ring than the indole system, such as indazole. The calculations performed suggest that the biological activity should remain with this change. The binding results show that although the change from the indole ring to the indazole slightly reduces affinity for the receptor, the Ki values fall within the same order of magnitude (Ki PUC-55 = 37.5 nM vs. Ki PUC-10 = 14.6 nM). Therefore, the structural change made can be considered tolerable. This observation can be partially attributed to the remaining structural characteristics of the ligand, specifically the naphthylsulfonyl group and the 2-methoxyphenylpiperazinyl moiety. Both structural motifs have proven to be the most effective among those we have employed in the design of 5-HT6 ligands within this structural framework, as previously reported. Our results indicate that PUC-10 and its indazole derivative PUC-55 are two potential 5-HT6 receptor antagonists containing an arylsulfonyl structural moiety that do not cause toxicity in cell lines even at high concentrations. Despite promising CNS drug-like properties, in silico alerts for PUC-10 and PUC-55 highlight potential CYP2C9/3A4 inhibition and limited aqueous solubility, each of which may require formulation adjustments or lead-optimization strategies to mitigate drug–drug interaction risks. Other 5-HT6 antagonists from the arylsulfonyl family or bearing the indole/indazole moieties, similar to PUC-10 and PUC-55, have been described as potent ligands47–50. However, to the best of our knowledge, none of them have been described as autophagy inducers, making our ligands the first series of compounds with indole/indazole groups to be proven as such. Notably, both modulators demonstrate the ability to induce mTOR-dependent autophagy in neuronal cells, suggesting potential utility in neurological disorders linked to dysregulated mTOR signaling.

Normally, G protein-coupled receptors are regulated by various mechanisms, and their expression can be influenced by ligands, both agonists and antagonists. Drugs recognized as GPCR antagonists are capable of inhibiting responses stimulated by agonists by binding to orthosteric or allosteric sites. Our results show that treatment with PUC-10 and PUC-55 significantly increased the expression of the 5-HT6 receptor compared to the control condition. Meanwhile, treatment with Rapamycin did not produce significant changes in the levels of the receptor, suggesting that only PUC-10 and PUC-55 binds the 5-HT6R.

Characterization of the 5-HT6R interactome revealed that the receptor interacts with proteins involved in the mTOR pathway. Furthermore, 5-HT6R-induced mTOR activation in the prefrontal cortex underlies cognitive deficits in rodent neurodevelopmental models of schizophrenia, which are reversed by Rapamycin and by 5HT6R antagonists24. Notably, GPCRs can also be activated in the absence of ligands, a phenomenon known as constitutive activity7,8. The mechanism of action of several ligands relies on their ability to abolish the constitutive, serotonin-independent activity of 5-HT6 receptors, which is abnormally enhanced in pathological situations14,51,52. Therefore, treatment with 5-HT6 receptor antagonists would be able to decrease the constitutive activity of the receptor, inactivating the non-canonical mTOR pathway and inducing the autophagic process.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by grants ANID FONDECYT N° 1230428 to ADC and Programa de Inserción Académica 2019, Vicerrectoría Académica y Prorrectoría, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile (ADC), ANID FONDECYT N° 1241192 (GRG) and BASAL/ANID FB210008 (CFL). ADC and GR acknowledges FONDEQUIP EQM170172 and EQM 160042. CFL acknowledges OpenEye-Cadence Molecular Sciences and ChemAxon for academic licenses.

Author contributions

JM A: perform autophagy experiments, writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Investigation, Formal analysis. GV: Perform the synthesis, Visualization, Validation, Investigation, Formal analysis. G A: perform new western blots experiments, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. C F. L: Molecular modeling and design, Visualization, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing.C A. T: Resources, Investigation. Ad C: Visualization, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision and Conceptualization.G R-G: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Conceptualization. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

• All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Biosafety Committee of Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile (Approval No. 220615003).

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

José Miguel Alcaíno and Gonzalo Vera contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Andrea del Campo, Email: andrea.delcampo@uc.cl.

Gonzalo Recabarren-Gajardo, Email: grecabarren@uc.cl.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-92755-6.

References

- 1.Nichols, D. E. & Nichols, C. D. Serotonin receptors. Chem. Rev.108 (5), 1614–1641. 10.1021/cr078224o (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCorvy, J. D. & Roth, B. L. Structure and function of serotonin G protein-coupled receptors. Pharmacol. Ther.150, 129–142. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2015.01.009 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dayer, A. G., Jacobshagen, M., Chaumont-Dubel, S. & Marin, P. 5-HT6 receptor: A new player controlling the development of neural circuits. ACS Chem. Neurosci.6 (7), 951–960. 10.1021/cn500326z (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoyer, D., Hannon, J. P. & Martin, G. R. Molecular, Pharmacological and functional diversity of 5-HT receptors. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav.71 (4), 533–554. 10.1016/S0091-3057(01)00746-8 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Celada, P., Puig, M. V. & Artigas, F. Serotonin modulation of cortical neurons and networks. Front. Integr. Nuerosci.710.1021/cr078224o (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Berumen, L. C., Rodríguez, A., Miledi, R. & García-Alcocer, G. Serotonin receptors in Hippocampus. Sci. World J.2012, 823493. 10.1100/2012/823493 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Deurwaerdère, P., Bharatiya, R., Chagraoui, A. & Di Giovanni, G. Constitutive activity of 5-HT receptors: factual analysis. Neuropharmacology168, 107967. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2020.107967 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang, Q. et al. Constitutive activity of serotonin receptor 6 regulates human cerebral organoids formation and Depression-like behaviors. Stem Cell. Rep.16 (1), 75–88. 10.1016/j.stemcr.2020.11.015 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang, S. et al. GPCRs steer Gi and Gs selectivity via TM5-TM6 switches as revealed by structures of serotonin receptors. Mol. Cell. 82 (14), 2681–95e6. 10.1016/j.molcel.2022.05.031 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manglik, A. & Kruse, A. C. Structural basis for G Protein-Coupled receptor activation. Biochemistry56 (42), 5628–5634. 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00747 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yun, H. M. & Rhim, H. 5-HT6 receptor ligands, EMD386088 and SB258585, differentially regulate 5-HT6 receptor-independent events. Toxicol. Vitro. 25 (8), 2035–2040. 10.1016/j.tiv.2011.08.004 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riccioni, T. et al. ST1936 stimulates cAMP, Ca2+, ERK1/2 and Fyn kinase through a full activation of cloned human 5-HT6 receptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol.661 (1–3), 8–14. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.04.028 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duhr, F. et al. Cdk5 induces constitutive activation of 5-HT6 receptors to promote neurite growth. Nat. Chem. Biol.10 (7), 590–597. 10.1038/nchembio.1547 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chaumont-Dubel, S., Dupuy, V., Bockaert, J., Bécamel, C. & Marin, P. The 5-HT6 receptor interactome: new insight in receptor signaling and its impact on brain physiology and pathologies. Neuropharmacology172, 107839. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.107839 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pujol, C. N. et al. Dynamic interactions of the 5-HT6 receptor with protein partners control dendritic tree morphogenesis. Sci. Signal.13 (618), eaax9520. 10.1126/scisignal.aax9520 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.LewerissaEI, Nadif KasriN & K. Linda Epigenetic regulation of autophagy-related genes: implications for neurodevelopmental disorders. Autophagy20 (1), 15–28. https://doi.org/th10.1080/15548627.2023.2250217 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas, S. D., Jha, N. K., Ojha, S. & Sadek, B. mTOR signaling disruption and its association with the development of autism spectrum disorder. Molecules28 (4). 10.3390/molecules28041889 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Lieberman, O. J. et al. mTOR suppresses macroautophagy during striatal postnatal development and is hyperactive in mouse models of autism spectrum disorders. Front. Cell. Neurosci.14, 70. https://doi.org/d10.3389/fncel.2020.00070 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deneubourg, C. et al. The spectrum of neurodevelopmental, neuromuscular and neurodegenerative disorders due to defective autophagy. Autophagy18 (3), 496–517. 10.1080/15548627.2021.1943177 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deng, Z., Zhou, X., Lu, J. H. & Yue, Z. Autophagy deficiency in neurodevelopmental disorders. Cell. Biosci.11 (1), 214. 10.1186/s13578-021-00726-x (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee, K. M., Hwang, S. K. & Lee, J. A. Neuronal autophagy and neurodevelopmental disorders. Exp. Neurobiol.22 (3), 133–142. 10.5607/en.2013.22.3.133 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levine, B. & Kroemer, G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell132 (1), 27–42. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.018 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saha, S., Panigrahi, D. P., Patil, S. & Bhutia, S. K. Autophagy in health and disease: A comprehensive review. Biomed. Pharmacother.104, 485–495. 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.05.007 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meffre, J. et al. 5-HT(6) receptor recruitment of mTOR as a mechanism for perturbed cognition in schizophrenia. EMBO Mol. Med.4 (10), 1043–1056. 10.1002/emmm.201201410 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tarkowski, B., Kuchcinska, K., Blazejczyk, M. & Jaworski, J. Pathological mTOR mutations impact cortical development. Hum. Mol. Genet.28 (13), 2107–2119. 10.1093/hmg/ddz042 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bockaert, J. & Marin, P. mTOR in brain physiology and pathologies. Physiol. Rev.95 (4), 1157–1187. 10.1152/physrev.00038.2014 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takei, N. & Nawa, H. mTOR signaling and its roles in normal and abnormal brain development. Front. Mol. Neurosci.7, 28. 10.3389/fnmol.2014.00028 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang, G. et al. Loss of mTOR-dependent macroautophagy causes autistic-like synaptic pruning deficits. Neuron83 (5), 1131–1143. 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.07.040 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pascual, M. et al. Role of mTOR-regulated autophagy in spine pruning defects and memory impairments induced by binge-like ethanol treatment in adolescent mice. Brain Pathol.31 (1), 174–188. 10.1111/bpa.12896 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Djajadikerta, A. et al. Autophagy induction as a therapeutic strategy for neurodegenerative diseases. J. Mol. Biol.432 (8), 2799–2821. 10.1016/j.jmb.2019.12.035 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Papandreou, M-E. & Tavernarakis, N. Selective autophagy as a potential therapeutic target in Age-Associated pathologies. Metabolites10.3390/metabo11090588 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee, A., Choo, H. & Jeon, B. Serotonin receptors as therapeutic targets for autism spectrum disorder treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci.10.3390/ijms23126515 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.ROCS. v3601. OpenEye, Cadence Molecular Sciences, Santa Fe, NM http://wwweyesopencom.

- 34.Hawkins, P. C., Skillman, A. G. & Nicholls, A. Comparison of shape-matching and Docking as virtual screening tools. J. Med. Chem.50 (1), 74–82. 10.1021/jm0603365 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vera, G. et al. Extended N-Arylsulfonylindoles as 5-HT6 receptor antagonists: design, synthesis and biological evaluation. Molecules21 (8). 10.3390/molecules21081070 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.OMEGA. v4221. OpenEye, Cadence Molecular Sciences, Santa Fe, NM http://wwweyesopencom.

- 37.QUACPAC. v2221. OpenEye, Cadence Molecular Sciences, Santa Fe, NM http://wwweyesopencomvvv.

- 38.EON. v2411. OpenEye, Cadence Molecular Sciences, Santa Fe, NM http://wwweyesopencom.

- 39.Daina, A., Michielin, O. & Zoete, V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep.7 (1), 42717. 10.1038/srep42717 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arrieta-Rodríguez, L. et al. Novel N-Arylsulfonylindoles targeted as ligands of the 5-HT6 receptor. Insights on the influence of C-5 substitution on ligand affinity. Pharmaceuticals14 (6). 10.3390/ph14060528 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Glennon, R. A., Bondarev, M. & Roth, B. 5-HT6 serotonin receptor binding of indolealkylamines: A preliminary structure-affinity investigation. Med. Chem. Res.9 (2), 108–117 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seranova, E., Ward, C., Chipara, M., Rosenstock, T. R. & Sarkar, S. In vitro screening platforms for identifying autophagy modulators in mammalian cells. In: (eds Ktistakis, N. & Florey, O.) Autophagy: Methods and Protocols. New York, NY: Springer New York; 389–428. (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Woolley, M. L., Marsden, C. A. & Fone, K. C. 5-ht6 receptors. Curr. Drug Targets CNS Neurol. Disord. 3 (1), 59–79. 10.2174/1568007043482561 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marazziti, D. et al. Serotonin receptors of type 6 (5-HT6): from neuroscience to clinical Pharmacology. Curr. Med. Chem.20 (3), 371–377. 10.2174/0929867311320030008 (2013). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barnes, N. M. et al. International union of basic and clinical pharmacology. CX. Classification of receptors for 5-hydroxytryptamine; pharmacology.and function. Pharmacol. Rev.73 (1), 310–520. 10.1124/pr.118.015552 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bojić, T., Sencanski, M., Perovic, V., Milicevic, J. & Glisic, S. In Silico Screening of Natural Compounds for Candidates 5HT6 Receptor Antagonists against Alzheimer’s Disease. Molecules27 (9). 10.3390/molecules27092626 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Canale, V. et al. 1-(Arylsulfonyl-isoindol-2-yl)piperazines as 5-HT(6)R antagonists: mechanochemical synthesis, in vitro Pharmacological properties and glioprotective activity. Biomolecules13 (1). 10.3390/biom13010012 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Haydar, S. N. et al. 5-Cyclic amine-3-arylsulfonylindazoles as novel 5-HT6 receptor antagonists. J. Med. Chem.53 (6), 2521–2527. 10.1021/jm901674f (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu, K. G. et al. 1-Sulfonylindazoles as potent and selective 5-HT6 ligands. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.19 (9), 2413–2415. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.03.071 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu, K. G. et al. Identification of a novel series of 3-piperidinyl-5-sulfonylindazoles as potent 5-HT6 ligands. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.19 (12), 3214–3216. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.04.108 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mokhtar, N. et al. The constitutive activity of spinal 5-HT(6) receptors contributes to diabetic neuropathic pain in rats. Biomolecules13 (2). 10.3390/biom13020364 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Drop, M. et al. Neuropathic pain-alleviating activity of novel 5-HT6 receptor inverse agonists derived from 2-aryl-1H-pyrrole-3-carboxamide. Bioorg. Chem.115, 105218. 10.1016/j.bioorg.2021.105218 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

• All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.