Abstract

Sorafenib is currently the first‐line therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (aHCC) patients. However, the outcomes and prognostic factors of sorafenib therapy have not been well investigated. We aimed to investigate the pretreatment factors and outcomes among Taiwanese aHCC patients receiving sorafenib treatment. A total of 347 patients with aHCC and well‐compensated liver cirrhosis (Child‐Pugh A) status receiving sorafenib were consecutively enrolled from March 2013 through December 2016. Pre‐treatment clinical data and viral hepatitis markers were collected and analyzed with their outcomes. The primary endpoint of the study was overall survival. The factors associated with overall survival were also investigated. The median overall survival of all the patients was 238 days (range, 9‐1504 days) with a 1‐year overall survival of 43.2%. Positive hepatitis B surface antigen and absence of portal vein thrombosis (PVT) were independent factors associated with better overall survival. The median duration of sorafenib therapy was 93.0 days (range, 4‐1504 days). After stopping sorafenib, the median survival was 93.0 days (range, 1‐1254 days). The 1‐year survival after stopping sorafenib was 21.2%. In chronic hepatitis B patients, total bilirubin level was the only factor associated with overall survival. Hepatitis C antibody RNA negativity, tumor size, PVT, and white blood cell count were the independent factors associated with survival among those chronic hepatitis C patients. There were different prognostic factors stratified by viral etiologies in aHCC patients receiving sorafenib. Viral eradication increased survival in chronic hepatitis C patients.

Keywords: advance, hepatocellular carcinoma, sorafenib, survival

1. INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) remained the fifth most common cancer worldwide and the third most frequently cancer‐related death.1, 2 The patients received a diverse range of treatment strategies according to their different stages of HCC. For early‐stage HCC, curative therapies, including surgery, radiofrequency ablation, and liver transplantation, were all feasible with a survival benefit.3, 4 For the patients with unresectable HCC without macrovascular invasion or extrahepatic spreading, transarterial chemoembolization could also provide an increase of survival.5 Unfortunately, the standard of care for those patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (aHCC), mainly with macrovascular invasion or extrahepatic spreading, was somewhat limited. The appearance of sorafenib, an inhibitor of several intracellular tyrosine protein kinases, opened a wide window for the long‐term trap.6 Two well‐designed phase III registry studies conducted in Western and Asia‐Pacific regions demonstrated the survival and time to progression benefit of sorafenib in aHCC patients. The median overall survival was 6.5 months in patients treated with sorafenib, compared with 4.2 months in those who received placebo. The median time to progression extended from 1.4 months in the placebo group to 2.8 months in the sorafenib group.7, 8 Consequently, sorafenib therapy was recommended as the first‐line therapy for aHCC patients.9, 10, 11

Nonethelessness, the clinical efficacy and predictive factors of sorafenib remain elusive. A study of subsequent exploratory subgroup analyses showed that sorafenib consistently improved the median overall survival and disease control rate compared with placebo in patients with aHCC.12 However, the exploration of prognostic factors has rarely been investigated. Pretreatment liver function status, portal vein thrombosis (PVT), and alpha‐fetoprotein (AFP) level were demonstrated to be the potential factors of prognosis.13, 14 The radiological response and adverse effects during treatment have been shown to be associated with efficacy.15, 16, 17 However, a relatively small scale of patients were recruited into most of the studies and the majority of them were from Western countries. In addition, the scenario of viral etiologies leading to HCC was different in the Asia‐Pacific region. Therefore, the outcomes of sorafenib therapy between different viral etiologies deserve further elucidation.

The present study aimed to investigate the outcomes of sorafenib therapy in aHCC patients in Taiwan. We also aimed to investigate the factors for prognostic prediction in aHCC patients receiving sorafenib therapy.

2. PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients with aHCC and reserved liver function (Child‐Pugh A) who received sorafenib therapy were consecutively recruited at a medical center and two regional hospitals in Southern Taiwan from March 2013 through December 2016. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The present study was approved by the ethics committee of Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

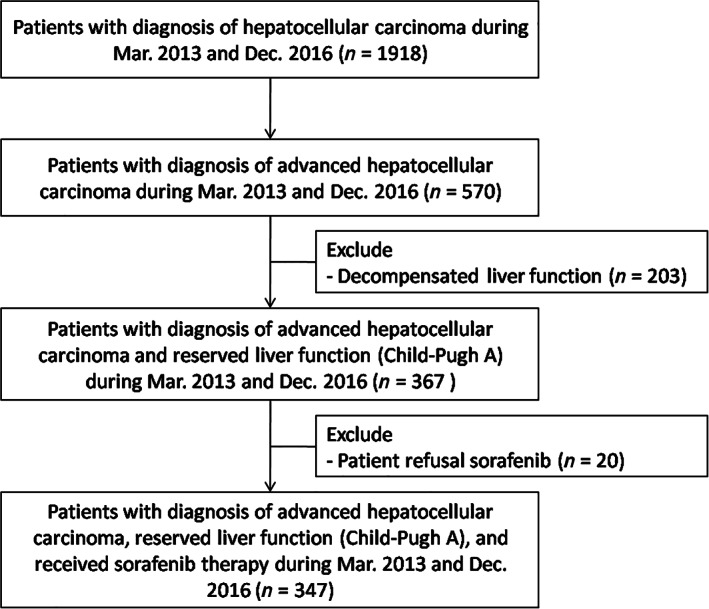

The inclusion criteria included (1) patients with a diagnosis of aHCC (HCC with either PVT, lymph node, or extrahepatic metastasis); (2) reserved liver function (Child‐Pugh score <7). The exclusion criteria were (1) decompensated liver function (Child‐Pugh score ≥7) and (2) refusal to receive sorafenib therapy. The study allocation flow chart is shown in Figure 1. The diagnosis and staging of HCC were confirmed by histopathological and/or imaging studies. Treatment modalities were then discussed and approved by a HCC consensus meeting based on current management guidelines.

Figure 1.

Patients' allocation flowchart

Baseline biochemical characteristics were examined prior to sorafenib therapy. These included hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA level, hepatitis C antibody (anti‐HCV), and hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA level. The tumor stages, the largest tumor size at initial HCC diagnosis, the presence of PVT, and lymph node or extrahepatic metastasis were recorded. The radiological tumor response and liver function were assessed in a 2‐month period basis upon the prescription of sorafenib. Once radiological tumor progression or decompensated liver function was identified, sorafenib therapy was no more prescribed after discussion with the patients.

The primary endpoint of the study was overall survival (the period after sorafenib therapy until death or loss of follow‐up). The secondary endpoints included survival after sorafenib discontinuation (the period after sorafenib discontinuation until death or loss to follow‐up) and the pre‐treatment factors associated with survival. The final follow‐up date for outcome assessment was August 2017. The patients were regarded as censored patients once they lost follow‐up or were unwilling for further visit. The patient status was further confirmed by the staff via phone call or email.

3. STATISTICS

Continuous variables are expressed as the median, 25th percentile, and 75th percentile, and the Mann‐Whitney U test was used to compare continuous variables. Numbers and percentages were used to describe the distribution of categorical variables. Chi‐squared and Fisher's exact tests were used to compare categorical variables. Survival and factors associated with survival were analyzed with the Kaplan‐Meier actuarial curve method with the log‐rank test and the Cox regression hazard model. Binary logistic regression analysis was used to identify the independent associated factor of 1‐year survival. All tests were two sided, and P < .05 was considered significant. All analyses were performed using the SPSS 17.0 statistical package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

4. RESULTS

A total of 347 patients were enrolled into the present study. The characteristics of all the patients at the initiation of sorafenib therapy are shown in Table 1. Two hundred and seventy‐seven (79.8%) of the patients were male and the median age was 63.0 years old. Nearly 64% of patients had liver cirrhosis, and hepatitis B (45.5%) was the major etiology of liver disease. At the initial diagnosis of HCC, only 45.1% of patients had aHCC and the medial largest tumor size was 5.8 cm. Prior to administration of sorafenib, PVT, lymph node, and extrahepatic metastasis were diagnosed in 189 (54.5%), 77 (22.2%), and 143 (41.2%) of the patients, respectively. The median AFP level was 228.1 ng/mL at the initiation of sorafenib. There were 148 (42.7%) of the patients who received concurrent other HCC therapy. Of them, 37 patients received concurrent transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), 26 patients received TACE plus radiotherapy (23) or surgery (3), 8 patients received surgery or radiofrequency ablation, 72 patients received radiotherapy, and the remaining 5 patients received hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy. A majority of the concurrent therapies were conducted at the time of sorafenib initiation.

Table 1.

Characteristics of all the patients at the initiation of sorafenib therapy

| N = 347 | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 63.0 (56.0, 71.0) |

| Male gender | 277 (79.8) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.3 (22.0, 27.2) |

| Liver cirrhosis | 221 (63.7) |

| Etiology | |

| Hepatitis B | 158 (45.5) |

| Hepatitis C | 90 (25.9) |

| Hepatitis B and C dual infection | 12 (3.5) |

| Nonhepatitis B or C | 87 (25.1) |

| Advanced stage at initial HCC diagnosis | 138/306 (45.1) |

| Largest tumor size at initial HCC diagnosis (cm) | 5.8 (3.0, 10.5) |

| Portal vein thrombosis | 189 (54.5) |

| Lymph node metastasis | 77 (22.2) |

| Distant metastasis | 143 (41.2) |

| Concurrent other HCC therapy | 148 (42.7) |

| White blood cell (×1000/mm3) | 6.4 (4.9, 8.7) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 12.2 (10.7, 13.3) |

| Platelet (×1000/mm3) | 162.0 (119.0, 244.0) |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 3.8 (3.3, 4.1) |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 1.0 (0.7, 1.4) |

| Prothrombin time (INR) | 1.07 (1.03, 1.13) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | 59.0 (38.0, 93.0) |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 42.0 (28.0, 68.3) |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.8 (0.7, 1.1) |

| Alpha‐fetoprotein (ng/ml) | 228.1 (10.2, 3451.0) |

| ALBI grade 1 | 264/333 (79.3) |

Notes: Continuous variables were presented with median (25th and 75th percentiles); categorical variables were presented with number (percentage).

Abbreviations: ALBI, albumin‐bilirubin; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; INR, international normalized ratio.

4.1. Overall survival and pretreatment prognostic factors

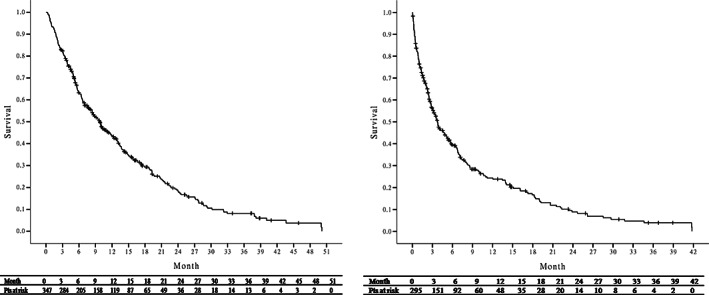

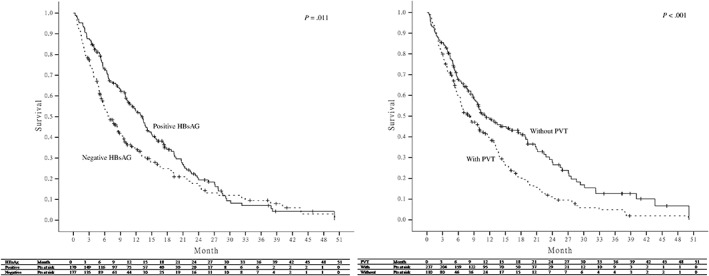

Eventually, 269 (77.5%) of the 347 patients died and the median overall survival of all the sorafenib‐treated patients was 238 days (range, 9‐1504 days). The 3‐, 6‐, 9‐, 12‐, and 24‐month overall survival rates were 82.4%, 63.3%, 54.2%, 43.2%, and 16.7%. (Figure 2A) We analyzed pretreatment factors associated with overall mortality using the Cox regression hazard model. The independent prognostic factors associated with overall mortality were positive HBsAg (HR 0.7, 95% CI 0.54‐0.94, P = .017) and PVT (HR 1.6, 95% CI 1.24‐2.17, P = .001) on adjusted analysis (Table 2). Those patients with positive HBsAg and the absence of PVT had a significantly higher overall survival than their counterparts (Figure 3). We further analyzed the factors associated with 1‐year overall survival. After exclusion of 43 patients, who were still alive but followed up less than 1 year, 119 (39.1%) of the 304 patients remained alive after 1 year of sorafenib therapy. Multivariate analysis also demonstrated that positive HBsAg (OR 2.7, 95% CI 1.51‐4.74, P = .001) was also an independent factor associated with 1‐year survival (data not shown here).

Figure 2.

A, Overall survival and B, survival after sorafenib discontinuation of all the sorafenib‐treated patients

Table 2.

Baseline factors associated with overall mortality in all sorafenib‐treated patients

| Crude | Adjusted | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Age (per 1 year increase) | 1.0 (0.99‐1.02) | .435 | ||

| Male gender | 0.9 (0.68‐1.24) | .583 | ||

| Body mass index (per 1 kg/m2 increase) | 1.0 (0.95‐1.01) | .228 | ||

| Liver cirrhosis | 1.1 (0.82‐1.35) | .701 | ||

| Positive hepatitis B surface antigen | 0.7 (0.58‐0.93) | .011 | 0.7 (0.54‐0.94) | .017 |

| Undetectable HBV DNA or HCV RNA | 0.7 (0.48‐1.03) | .067 | ||

| Advanced stage at initial HCC diagnosis | 1.4 (1.12‐1.87) | .005 | 1.1 (0.84‐1.56) | .400 |

| Largest tumor size at initial HCC diagnosis (per 1 cm increase) | 1.0 (1.02‐1.07) | .001 | 1.0 (0.99‐1.05) | .219 |

| Portal vein thrombosis | 1.5 (1.21‐1.97) | .001 | 1.6 (1.24‐2.17) | .001 |

| Lymph node metastasis | 1.0 (0.75‐1.32) | .957 | ||

| Distant metastasis | 0.8 (0.66‐1.08) | .185 | ||

| White blood cell (per 1000/mm3 increase) | 1.0 (1.01‐1.09) | .016 | 1.0 (0.99‐1.08) | .090 |

| Hemoglobin (per 1 mg/dL increase) | 1.0 (0.94‐1.07) | .966 | ||

| Platelet (per 1000/mm3 increase) | 1.0 (1.00‐1.00) | .597 | ||

| Albumin (per 1 g/dL increase) | 0.8 (0.62‐0.99) | .042 | 0.8 (0.64‐1.11) | .230 |

| Total bilirubin (per 1 mg/dL increase) | 1.1 (1.00‐1.12) | .072 | ||

| Prothrombin time (INR; per 1 increase) | 1.0 (0.88‐1.24) | .606 | ||

| Aspartate aminotransferase (per 10 U/L increase) | 1.0 (1.00‐1.01) | .330 | ||

| Alanine aminotransferase (per 10 U/L increase) | 1.0 (0.99‐1.02) | .577 | ||

| Creatinine (per 1 mg/dL increase) | 1.1 (0.97‐1.30) | .130 | ||

| Alpha‐fetoprotein (per 100 ng/mL increase) | 1.0 (1.00‐1.00) | .003 | 1.0 (1.00‐1.00) | .271 |

| ALBI grade 1 | 0.8 (0.63‐1.07) | .138 |

Note: Statistics with Cox regression hazard analysis.

Abbreviation: ALBI, albumin‐bilirubin; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HR, hazard ratio; INR, international normalized ratio.

Figure 3.

Comparison of overall survival of all the sorafenib‐treated patients according to hepatitis B surface antigen and portal vein thrombosis

4.2. Survival after sorafenib discontinuation

The median duration of sorafenib therapy for all the patients was 93.0 days (range, 4‐1504 days), and the median dosage of sorafenib was 440 (331, 643) mg/day. Sorafenib therapy was discontinued in 338 patients. Of them, the majority of 283 (83.7%) patients were due to HCC progression or related death, 22 (6.5%) patients were due to deterioration of liver function (Child A—>B/C), 18 (5.3%) was due to adverse effects, and the remaining 15 (4.4%) patients were due to transferring to other hospital or patient refusal. After discontinuation of sorafenib therapy, there were a total of 295 patients remained alive and the median survival after sorafenib discontinuation was 93.0 days (range, 1‐1254 days). The 1‐, 3‐, 6‐, and 12‐month survival rates were 76.4%, 56.3%, 39.5%, and 21.2%, respectively (Figure 2B).

Regarding the factors associated with overall mortality after sorafenib discontinuation, the results of crude analysis revealed Child‐Pugh A at stopping sorafenib (HR 0.5, 95% CI 0.40‐0.68, P < .001), and concurrent other HCC therapy after stopping sorafenib (HR 0.7, 95% CI 0.47‐0.92, P = .013) as factors associated with decreased overall mortality. However, an advanced stage at initial HCC diagnosis (HR 1.4, 95% CI 1.09‐1.87, P = .010), a larger tumor size at initial HCC diagnosis (HR 1.0, 95% CI 1.01‐1.07, P = .013), PVT (HR 1.6, 95% CI 1.22‐2.06, P = .001), and higher white blood cell (WBC) count (HR 1.1, 95% CI 1.02‐1.10, P = .004) were found to be associated with increased overall mortality. After being adjusted to the above factors, only Child‐Pugh A at stopping sorafenib (HR 0.6, 95% CI 0.46‐0.87, P = .005) was the independent positive prognostic factors and PVT (HR 1.4, 95% CI 1.02‐1.89, P = .035) was the only negative prognostic factor (Table 3).

Table 3.

Baseline factors associated with overall mortality after sorafenib discontinuation

| Crude | Adjust | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Age (per 1 year increase) | 1.0 (0.99‐1.01) | .617 | ||

| Male gender | 1.0 (0.72‐1.36) | .956 | ||

| Body mass index (per 1 kg/m2 increase) | 1.0 (0.94‐1.01) | .098 | ||

| Liver cirrhosis | 1.2 (0.89‐1.51) | .287 | ||

| Child‐Pugh A at stopping sorafenib | 0.5 (0.40‐0.68) | <.001 | 0.6 (0.46‐0.87) | .005 |

| Positive hepatitis B surface antigen | 0.9 (0.67‐1.12) | .274 | ||

| Undetectable HBV DNA or HCV RNA | 0.8 (0.53‐1.22) | .306 | ||

| Advanced stage at initial HCC diagnosis | 1.4 (1.09‐1.87) | .010 | 1.2 (0.87‐1.64) | .271 |

| Largest tumor size at initial HCC diagnosis (per 1 cm increase) | 1.0 (1.01‐1.07) | .013 | 1.0 (0.98‐1.05) | .526 |

| Portal vein thrombosis | 1.6 (1.22‐2.06) | .001 | 1.4 (1.02‐1.89) | .035 |

| Lymph node metastasis | 0.9 (0.63‐1.15) | .291 | ||

| Distant metastasis | 0.9 (0.66‐1.12) | .260 | ||

| Concurrent other HCC therapy after stopping sorafenib | 0.7 (0.47‐0.92) | .013 | 0.8 (0.54‐1.12) | .183 |

| White blood cell (×1000/mm3) | 1.1 (1.02‐1.10) | .004 | 1.0 (1.00‐1.09) | .069 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 1.0 (0.92‐1.06) | .745 | ||

| Platelet (×1000/mm3) | 1.0 (1.00‐1.00) | .354 | ||

| Albumin (g/dl) | 0.8 (0.61‐1.02) | .070 | ||

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 1.0 (0.96‐1.09) | .435 | ||

| Prothrombin time (INR) | 1.0 (0.86‐1.20) | .872 | ||

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | 1.0 (1.00‐1.01) | .781 | ||

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 1.0 (0.99‐1.02) | .720 | ||

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.0 (0.85‐1.22) | .829 | ||

| Alpha‐fetoprotein (ng/ml) | 1.0 (1.00‐1.00) | .382 | ||

| ALBI grade 1 | 0.8 (0.64‐1.09) | .176 |

Statistics with Cox regression hazard analysis.

Abbreviation: ALBI, albumin‐bilirubin; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HR, hazard ratio; INR, international normalized ratio.

4.3. The association between survival, viral hepatitis, and antiviral therapy

Comparing patients with negative HBsAg, patients with positive HBsAg were of younger age (P < .001), higher male gender (P = .001), and higher hemoglobin level (P = .037). Patients with positive HBsAg also had a higher rate of concurrent other HCC therapy although it did not reach a significant difference (P = .051). There were no significant differences in the largest HCC size, initial stage, PVT, and AFP levels (data not shown). Further Cox regression hazard analysis showed that male gender (HR 0.6, 95% CI 0.34‐0.99, P = .044), advanced stage at initial HCC diagnosis (HR 1.4, 95% CI 1.00‐2.04, P = .048), larger tumor size at initial HCC diagnosis (HR 1.0, 95% CI 1.01‐1.09, P = .017), PVT (HR 1.5, 95% CI 1.03‐2.10, P = .034), and total bilirubin level (HR 1.4, 95% CI 1.13‐1.71, P = .002) were factors associated with overall mortality in patients with positive HBsAg. After adjusting the above factors, the total bilirubin level (HR 1.3, 95% CI 1.06‐1.66, P = .015) was the only independent factor (data not shown).

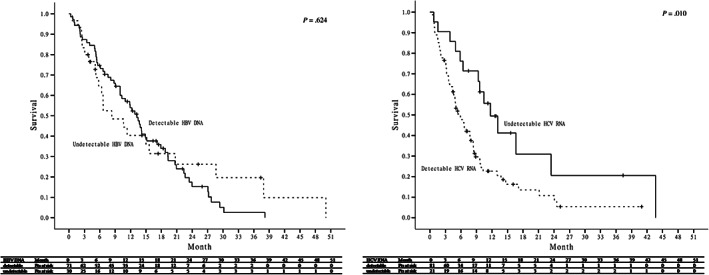

In the 158 HBV monoinfected patients, 71 (44.9%) patients had been treated or under HBV oral nucleot(s)ide analog therapy during sorafenib therapy and 34 of the 71 patients started HBV nucleot(s)ide analogue (NUC) at the initiation or within 1 month of sorafenib therapy. HBV DNA level was available in 94 of the 158 HBV monoinfected patients, and only 29 (30.9%) of the 94 patients were undetectable HBV DNA prior to sorafenib therapy. In the 90 HCV monoinfected patients, 31 (34.4%) patients have received HCV antiviral therapy (30 with pegylated interferon and the other one with direct‐acting antiviral therapy) before sorafenib therapy. Only 17 (18.9%) patients were undetectable HCV RNA prior to sorafenib therapy. In the 12 HBV and HCV dual‐infected patients, 1 (8.3%) and 4 (33.3%) patients were undetectable HBV DNA and HCV RNA prior to sorafenib therapy. As has been mentioned, viral suppression (undetectable HBV DNA or HCV RNA) prior to sorafenib therapy was not associated with overall survival in all the patients (P = .067). Further analysis showed that there was no significant difference in overall survival between patients with detectable and undetectable HBV DNA in patients with positive HBsAg, (P = .624). However, in patients with positive anti‐HCV, patients with undetectable HCV RNA had a significantly higher overall survival compared to patients with detectable HCV RNA (P = .010) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Comparison of overall survival between patients with and without viral suppression prior to sorafenib therapy

Undetectable HCV RNA was associated with overall survival and survival after sorafenib discontinuation. In patients with positive anti‐HCV, patients with undetectable HCV RNA had a significantly lower rate of advanced stage HCC at initial diagnosis (P = .010), higher albumin level (P < .001), and lower aspartate aminotransferase level (P = .001) (data not shown). There was no difference in tumor size, PVT, concurrent therapy, and AFP level. Further analysis of the factors associated with overall mortality in patients with positive anti‐HCV also demonstrated undetectable HCV RNA (HR 0.5, 95% CI 0.27‐0.99, P = .046), largest HCC size (HR 1.1, 95% CI 1.01‐1.17, P = .037), PVT (HR 1.9, 95% CI 1.12‐3.25, P = .017), and WBC count (HR 1.1, 95% CI 1.00‐1.13, P = .048) as independent associated factors (Table 4).

Table 4.

Baseline factors associated with overall mortality in patients with positive anti‐HCV

| Crude | Adjust | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Age (per 1 year increase) | 1.0 (1.00‐1.05) | .097 | ||

| Male gender | 1.0 (0.61‐1.56) | .910 | ||

| Body mass index (per 1 kg/m2 increase) | 0.9 (0.90‐1.00) | .050 | ||

| Liver cirrhosis | 0.9 (0.50‐1.45) | .552 | ||

| Undetectable HCV RNA | 0.5 (0.25‐0.84) | .012 | 0.5 (0.27–0.99) | .046 |

| Advanced stage at initial HCC diagnosis | 1.3 (0.81‐2.22) | .257 | ||

| Largest tumor size at initial HCC diagnosis (per 1 cm increase) | 1.1 (1.06‐1.22) | <.001 | 1.1 (1.01–1.17) | .037 |

| Portal vein thrombosis | 1.7 (1.05‐2.68) | .030 | 1.9 (1.12‐3.25) | .017 |

| Lymph node metastasis | 0.9 (0.51‐1.42) | .539 | ||

| Distant metastasis | 1.1 (0.66‐1.71) | .799 | ||

| White blood cell (per 1000/mm3 increase) | 1.1 (1.04‐1.16) | <.001 | 1.1 (1.00–1.13) | .048 |

| Hemoglobin, per 1 mg/dL increase | 1.0 (0.87‐1.13) | .884 | ||

| Platelet (per 1000/mm3 increase) | 1.0 (1.00‐1.00) | .177 | ||

| Albumin (per 1 g/dL increase) | 0.7 (0.49‐0.96) | .027 | 0.8 (0.52‐1.19) | .256 |

| Total bilirubin (per 1 mg/dL increase) | 1.3 (0.92‐1.78) | .151 | ||

| Prothrombin time (INR; per 1 increase) | 6.2 (0.46‐85.0) | .171 | ||

| Aspartate aminotransferase (per 10 U/L increase) | 1.0 (1.00‐1.01) | .113 | ||

| Alanine aminotransferase (per 10 U/L increase) | 1.0 (1.00‐1.00) | .260 | ||

| Creatinine (per 1 mg/dL increase) | 0.9 (0.72‐1.21) | .614 | ||

| Alpha‐fetoprotein (per 100 ng/mL increase) | 1.0 (1.00‐1.00) | .202 | ||

| ALBI grade 1 | 0.7 (0.43‐1.20) | .211 |

Statistics with Cox regression hazard analysis.

Abbreviation: ALBI, albumin‐bilirubin; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HR, hazard ratio; INR, international normalized ratio.

5. DISCUSSION

The outcome prediction of sorafenib treatment among those aHCCpatients remains a challenging task in clinical practice. The present study was the largest scale study investigating the prognosis of sorafenib therapy in the aspect. We demonstrate that the mean overall survival was 8 months and the mean survival was 3 months after sorafenib discontinuation in advanced HCC patients. The favorable prediction factors associated with survival were positive HBsAg and absence of PVT. There were different prognostic factors stratified by viral etiologies. In addition, viral eradication increased the survival rate in CHC patients. Our results thus provided the evidence for outcome prediction in those aHCC before sorafenib therapy.

Our results demonstrated that the median overall survival was 238 days with a 1‐year survival of 43.2%, which was longer than previous studies in aHCC patients receiving sorafenib treatment. In the initial phase 3 “SHARP” study, sorafenib‐treated patients demonstrated a median overall survival of 10.7 months with a 1‐year survival of 44%.7 However, the following phase 3 study conducted in the Asia‐Pacific region showed a decreased medial overall survival of 6.5 months in sorafenib‐treated patients with majority HBV infection.8 The discrepancy between the present and the two phase 3 studies might be due to the different characters of patients. Comparing to another real‐world study conducted in Korea, the present study also showed a better overall survival. (238 vs 91 days)14 The discrepancy might be due to the shorter duration of sorafenib treatment in the study.

In the exploratory analysis of the two phase 3 studies, the presence of macrovascular invasion, high AFP, and neutrophil‐to‐lymphocyte ratio demonstrated a poor prognosis of overall survival.18 A recent multicenter study from the United Kingdom also demonstrated Child‐Pugh class, performance status, and albumin‐bilirubin grade as prognostic factors in sorafenib‐treated patients.19 Other multicenter observational studies have recently demonstrated similar results of Child‐Pugh class as the main determining factor of overall survival.20, 21, 22 PVT was another frequently reported prognostic factor.13, 14 Consistent results were found in our study. Side effects to the sorafenib therapy were also reported as indicators of treatment response. In a small‐scale study from Japan, the appearance of hand‐foot syndrome during therapy was found to be an indicator for sorafenib response.23 Another study also demonstrated hand‐foot syndrome and diarrhea as indicators of better survival.16

The clarification of outcomes between different etiologies, mainly viral factors, is of important clinical implication because HCC was mostly progressed from viral hepatitis. The novel finding of our study was the association between positive HBsAg and better overall survival. The recent exploratory pooled analysis of the two phase 3 studies showed that the survival benefit of sorafenib might be greater in subjects with HCV infection.18 The explanation of the discrepancy between our study and the exploratory study was difficult. The mechanism of the greater survival benefit in subjects with positive HBsAg was still uncertain and need further investigation. Viral replication status might be the possible explanation. On the other side, in subjects with HCV infection, HCV viral replication had never been reported as a determining factor of survival. Our study first demonstrated that undetectable HCV RNA had a significant survival benefit either under or stopping sorafenib therapy. The reason might be due to the improving liver function after eradication of HCV. As previous studies, eradication of HCV helped improving the liver function and also the fibrosis regression.24, 25, 26, 27 Furthermore, our results reflected the indication of antiviral therapy, wherein the HCV antiviral therapy was not suggested due to the limited life.28

In the present study, we also demonstrated the survival of 3 months and 21% of 1‐year survival after sorafenib discontinuation, which had never been talked in previous studies. Recently, the new target therapy agent “regorafenib” had been shown to significantly prolong the survival of patients after failure of sorafenib29, 30 and had been recently approved by the US FDA as the second‐line therapy of advanced HCC patients. However, the new therapy was not yet approved in Taiwan. So, no further systemic therapy and only local‐regional therapy may be provided after sorafenib discontinuation in the present study. And we found that only Child‐Pugh class at stopping sorafenib and PVT were the independent factors associated with the survival after sorafenib discontinuation. A recent study also demonstrated that the Child‐Pugh class, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance, serum sodium, and AFP level are independent factors to predict survival after sorafenib discontinuation.31 In this study, the median survival was 3.9 months, which was similar to our study.

There were several limitations. First, the present study was retrospectively reviewed for medical records, and several parameters were lacking and not able to obtain. For example, a part of subjects with HBV or HCV infection lacked data of viral replication and it might also be a determining factor of the outcomes. Second, the on‐treatment adverse effect and radiological response were not analyzed. In the present study, we only focus on pre‐treatment prognostic factors and so the on‐treatment responses were not analyzed. Another limitation was that the PVT was not divided as branch or main PVT. The clinical outcomes might be different between main and branch PVT, and sorafenib might not be recommended for patients with main PVT. However, we did not have the data since our cancer registration database did not include information of branch or main PVT.

In conclusion, we demonstrated a compatible overall survival of sorafenib therapy in the real‐world practice. Live function and PVT remained the determining prognostic factors. Regarding viral factors, hepatitis B infection and hepatitis C infection with undetectable HCV RNA were also better prognostic factors.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank secretary and serum processing help from Taiwan Liver Research Foundation (TLRF). They did not influence how the study was conducted or the approval of the manuscript. The results of the study had been presented in a poster form during the 2018 Annual Meeting of the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

Yeh M‐L, Huang C‐F, Huang C‐I, et al. The prognostic factors between different viral etiologies among advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients receiving sorafenib treatment. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2019;35:624–632. 10.1002/kjm2.12105

Funding information Kaohsiung Medical University, Grant/Award Numbers: MOST104‐2314‐B‐037‐078‐MY3, S10606, KMUH105‐5R04, MOST105‐2628‐B‐037‐002‐MY2, KMUH105‐5R03, KMUH104‐4 T02

REFERENCES

- 1. Bosch FX, Ribes J, Diaz M, Cleries R. Primary liver cancer: Worldwide incidence and trends. Gastroenterology. 2004;127(5 Suppl 1):S5–S16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(2):69–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Llovet JM, Schwartz M, Mazzaferro V. Resection and liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2005;25(2):181–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shiina S, Teratani T, Obi S, Sato S, Tateishi R, Fujishima T, et al. A randomized controlled trial of radiofrequency ablation with ethanol injection for small hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(1):122–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Llovet JM, Real MI, Montana X, Planas R, Coll S, Aponte J, et al. Arterial embolisation or chemoembolisation versus symptomatic treatment in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359(9319):1734–1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Llovet JM, Bru C, Bruix J. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: The BCLC staging classification. Semin Liver Dis. 1999;19(3):329–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(4):378–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, Tsao CJ, Qin S, Kim JS, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia‐Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A phase III randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(1):25–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Forner A, Reig ME, de Lope CR, Bruix J. Current strategy for staging and treatment: The BCLC update and future prospects. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30(1):61–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Heimbach JK, Kulik LM, Finn R, Sirlin CB, Abecassis M, Roberts LR, et al. AASLD guidelines for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2018;67(1):358–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. European Association for the Study of the Liver, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer . EASL‐EORTC clinical practice guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56(4):908–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bruix J, Raoul JL, Sherman M, Mazzaferro V, Bolondi L, Craxi A, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: Subanalyses of a phase III trial. J Hepatol. 2012;57(4):821–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Inghilesi AL, Gallori D, Antonuzzo L, Forte P, Tomcikova D, Arena U, et al. Predictors of survival in patients with established cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sorafenib. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(3):786–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cho JY, Paik YH, Lim HY, Kim YG, Lim HK, Min YW, et al. Clinical parameters predictive of outcomes in sorafenib‐treated patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2013;33(6):950–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lencioni R, Montal R, Torres F, Park JW, Decaens T, Raoul JL, et al. Objective response by mRECIST as a predictor and potential surrogate end‐point of overall survival in advanced HCC. J Hepatol. 2017;66(6):1166–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Reig M, Torres F, Rodriguez‐Lope C, Forner A, N LL, Rimola J, et al. Early dermatologic adverse events predict better outcome in HCC patients treated with sorafenib. J Hepatol. 2014;61(2):318–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Branco F, Alencar RS, Volt F, Sartori G, Dode A, Kikuchi L, et al. The impact of early dermatologic events in the survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated with Sorafenib. Ann Hepatol. 2017;16(2):263–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bruix J, Cheng AL, Meinhardt G, Nakajima K, De Sanctis Y, Llovet J. Prognostic factors and predictors of sorafenib benefit in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: Analysis of two phase III studies. J Hepatol. 2017;67(5):999–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. King J, Palmer DH, Johnson P, Ross P, Hubner RA, Sumpter K, et al. Sorafenib for the treatment of advanced hepatocellular cancer—a UK Audit. Clin Oncol. 2017;29(4):256–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ganten TM, Stauber RE, Schott E, Malfertheiner P, Buder R, Galle PR, et al. Sorafenib in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma‐results of the observational INSIGHT study. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(19):5720–5728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hollebecque A, Cattan S, Romano O, Sergent G, Mourad A, Louvet A, et al. Safety and efficacy of sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma: The impact of the child‐Pugh score. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34(10):1193–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pinter M, Sieghart W, Hucke F, Graziadei I, Vogel W, Maieron A, et al. Prognostic factors in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sorafenib. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34(8):949–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yada M, Masumoto A, Motomura K, Tajiri H, Morita Y, Suzuki H, et al. Indicators of sorafenib efficacy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(35):12581–12587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. van der Meer AJ, Berenguer M. Reversion of disease manifestations after HCV eradication. J Hepatol. 2016;65(1 Suppl):S95–S108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chen Yi Mei SLG, Thompson AJ, Christensen B, Cunningham G, McDonald L, Bell S, et al. Sustained virological response halts fibrosis progression: A long‐term follow‐up study of people with chronic hepatitis C infection. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0185609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Persico M, Rosato V, Aglitti A, Precone D, Corrado M, De Luna A, et al. Sustained virological response by direct antiviral agents in HCV leads to an early and significant improvement of liver fibrosis. Antivir Ther. 2017;23:129–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tada T, Kumada T, Toyoda H, Mizuno K, Sone Y, Kataoka S, et al. Improvement of liver stiffness in patients with hepatitis C virus infection who received direct‐acting antiviral therapy and achieved sustained virological response. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32:1982–1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Panel AIHG. Hepatitis C guidance: AASLD‐IDSA recommendations for testing, managing, and treating adults infected with hepatitis C virus. Hepatology. 2015;62(3):932–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bruix J, Qin S, Merle P, Granito A, Huang YH, Bodoky G, et al. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): A randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10064):56–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Killock D. Liver cancer: Regorafenib ‐ a new RESORCE in HCC. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14(2):70–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lee HW, Kim HS, Kim SU, Kim DY, Kim BK, Park JY, et al. Survival estimates after stopping sorafenib in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: NEXT score development and validation. Gut Liver. 2017;11(5):693–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]