Abstract

Purpose:

Identification of patients’ intended chemotherapy regimens is critical to most research questions conducted in the real-world setting of cancer care. Yet, these data are not routinely available in electronic health records (EHR) at the specificity required to address these questions. We developed a methodology to identify patients’ intended regimens from EHR data in the Optimal Breast Cancer Chemotherapy Dosing (OBCD) study.

Patients and Methods:

In women ages 18+y, diagnosed with primary stage I-IIIA breast cancer at Kaiser Permanente Northern California (2006–2019), we categorized participants into 24 drug combinations described in National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines for breast cancer treatment. Participants were categorized into 50 guideline chemotherapy administration schedules within these combinations using an iterative algorithm process, followed by chart abstraction where necessary. We also identified patients intended to receive non-guideline administration schedules within guideline drug combinations and non-guideline drug combinations. This process was adapted at Kaiser Permanente Washington using abstracted data (2004–2015).

Results:

In the OBCD cohort, 13,231 women received adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy, of whom 10,213 (77%) had their intended regimen identified via algorithm, 2,416 (18%) via abstraction, and 602 (4.5%) couldn’t be identified. Across guideline drug combinations, 111 non-guideline dosing schedules were used, alongside 61 non-guideline drug combinations. A number of factors were associated with requiring abstraction for regimen determination, including decreasing neighborhood household income, earlier diagnosis year, later stage, nodal status, and HER2+ status.

Conclusions:

We describe the challenges and approaches to operationalize complex, real-world data to identify intended chemotherapy regimens in large, observational studies. This methodology can improve efficiency of use of large-scale clinical data in real-world populations, helping answer critical questions to improve care delivery and patient outcomes.

Keywords: chemotherapy, real-world evidence, methodology, breast cancer, cancer care delivery

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The opportunity to use real-world data to generate evidence has expanded dramatically in recent years with the implementation of electronic health records (EHRs)1. Such data can be used to address many pressing questions related to cancer care, including questions pertaining to use and effectiveness of anticancer medications or adherence to guideline-concordant care. Comparing chemotherapy received to that intended is critical to answering such questions in real-world patient populations. EHR data on drugs, doses and dates administered, can be used to capture the chemotherapy received. However, determining the intended chemotherapy regimen is a complex endeavor, as often the required detailed data are not available on intended regimen at such specificity to capture intended dosages, as well cycle number and interval. For example, knowledge that a patient was intended to receive “dose-dense cyclophosphamide + doxorubicin, followed by paclitaxel” is insufficient to determine the specific administration schedule intended due to prescribing variations in intended dose per body surface area, number of intended cycles, and cycle interval.

We developed a process to identify the intended chemotherapy regimen using rich chemotherapy data in the Optimal Breast Cancer Chemotherapy Dosing (OBCD) study. We report the prevalence of regimen determination method (algorithm vs abstraction), overall and by drug combination. We report associated patient characteristics to ascertain the potential for bias if classification relied solely on algorithms.

This methodology enables determination of the intended regimen at an unprecedented level of specificity and scale, making it possible to conduct outcomes research in the real-world setting of cancer care. Our methodology, while used to support the OBCD study in a cohort of patients with early-stage breast cancer diagnosed and treated in an integrated healthcare delivery setting, can be modified for other populations, including those treated at different healthcare sites and undergoing chemotherapy for other cancers.

Methods

Population

The OBCD cohort consists of 36,646 women diagnosed with stage I-IIIA breast cancer at Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) and Kaiser Permanente Washington (KPWA) and was built to answer questions around chemotherapy dosing. This paper presents the methodology of how the chemotherapy data for this study were operationalized.

Both KPNC and KPWA are members of the Health Care Systems Research Network (HCSRN), a consortium of integrated health care delivery systems, each with its own Virtual Data Warehouse (VDW). The VDW is a virtual data model with standardized variable definitions and formats derived from clinical and administrative databases at each site2 and includes demographic and treatment data3–6.

Cancer registries were used to identify cases and obtain information on diagnostic characteristics. KPNC maintains its own internal cancer registry that reports to the Greater California and Greater Bay Area Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Registries that are supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI)7. KPWA links health plan enrollees with the Seattle-Puget Sound SEER Registry to identify cancers that occur in their membership. Treatment data at KPNC was obtained from the EHR, including drugs, doses and dates received; at KPWA this was obtained via abstraction.

Eligibility criteria included: diagnosis with primary breast cancer with no prior history or same day diagnosis of cancer (except non-melanoma skin cancer), enrolled at KPWA or KPNC at diagnosis, had available medical records, and did not opt out of research studies.

This analysis was restricted to 12,558 women diagnosed between 2006–2019 at KPNC and 2004–2015 at KPWA receiving chemotherapy for breast cancer (exclusive of sarcoma and carcinoid morphologies) and were not known to be enrolled in randomized-controlled trials. KPWA also included a subsample of women diagnosed with stage I-II breast cancer that were part of a previous study (COMBO, COmmonly used Medications and Breast Cancer Outcomes) with extensive abstracted treatment data that has been previously described8.

Analyses were conducted in Stata 17. IRB approval was obtained from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, KPNC, KPWA and Rutgers University, with a waiver of consent obtained at sites from which data were collected (KPNC and KPWA).

KPNC: Determining the intended regimen

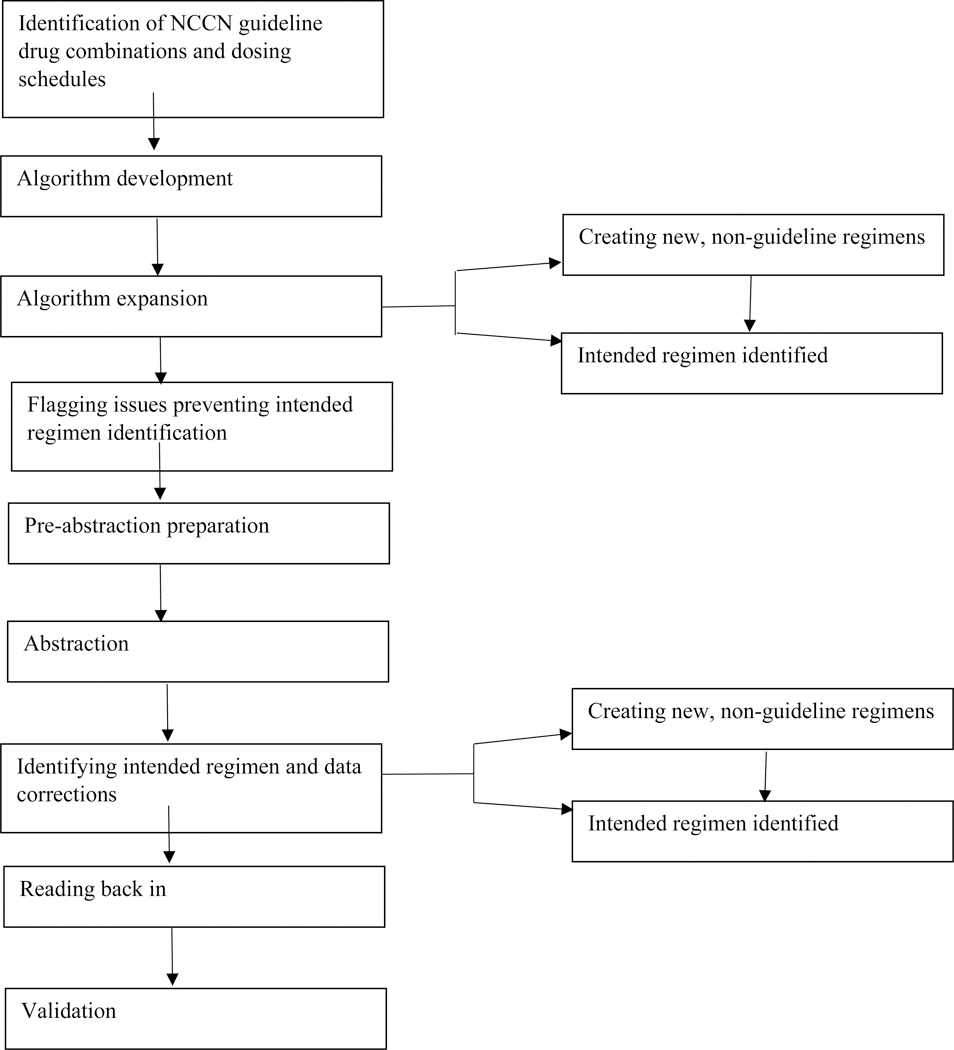

We developed an algorithmic approach to categorize drug data into intended regimens (Figure 1). Examples are available in the Supplemental Methods (eTable 1).

Figure 1:

Regimen identification process

Algorithm development

First, we identified the intended drug combination by categorizing participants into the 24 drug combinations described in NCCN guidelines for early-stage breast cancer treatment over the study period (2004–2019)9. Those not captured in these drug combinations were classified as receiving non-guideline drug combinations.

After categorization by drug combination, we classified participants into the specific drug administration schedules in the NCCN guidelines (of which there are 50 within the 24 NCCN-guideline drug combinations) by building an algorithm that categorized those receiving the exact treatment as described in the guidelines into the appropriate classification. Initially, participants were categorized by algorithm if they received chemotherapy exactly per guideline. As this population was treatment-naïve, only first chemotherapy was used. The algorithms were then expanded with clinical guidance, so chemotherapy closely aligned with the guideline schedule could still be classified, for example, if a participant had a slightly different than expected cycle length (e.g. 20 days, instead of 21), or 2 drugs in the same cycle administered a day apart. We expanded until the algorithm reached the maximum point of integrity; for example, if someone received all cycles 17 days apart, their intended regimen could not be assumed to have 14-day or 21-day intervals, and thus such participants were sent for abstraction. Patients were classified into NCCN regimens regardless of when received (to maximize the number of participants whose intended regimen could be defined). Chemotherapy gaps >90 days were sent for abstraction to determine if the latter treatment was a continuation of the first regimen or the result of disease progression. Chart abstraction was conducted by a medical chart abstractor at each site.

Non-guideline regimens (NGRs), including non-guideline drug combinations and non-guideline administration schedules were defined separately. For the purposes of identifying patients’ intended regimens, guideline regimens received before or after their inclusion in NCCN guidelines were considered guideline regimens.

During the algorithm development process, clear patterns emerged of substantial numbers of women treated with intended NGRs. These included variations such as 6 cycles instead of 4 (in the case of cyclophosphamide + docetaxel), treatment duration of 6 months instead of 12 (in the case of paclitaxel + trastuzumab) and use of intravenous instead of oral cyclophosphamide (in the case of cyclophosphamide, 5-fluroruracil and methotrexate). These were defined as NGRs.

Uncategorized participants were abstracted. Participants were also abstracted with missing infusion doses, missing height/weight variables necessary for dosing calculations and cycle intervals >90 days. This process was repeated across all drug combinations.

Medical Record Abstraction

For each participant, abstraction questions were informed by the reasons participants could not be algorithmically classified. Anyone identified as receiving non-guideline drug combinations or non-guideline dosing schedule via algorithm were also sent for manual chart abstraction to identify the intended regimen at the outset.

Responses to abstraction inquiries were used alongside EHR data to determine the intended regimen. For example, a question sent to the abstractor might be “what was the intended regimen at the start of chemotherapy?”. The response, taken from notes, could be “cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin and docetaxel dose dense.” Using these data and EHR data, we could identify the intended regimen as doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide every two weeks/4 cycles, followed by docetaxel every two weeks/4 cycles. To preserve the granularity of prescribing clinicians’ intentions (including NGRs), new regimens were defined as observed, with descriptors for intended doses, cycle length, intervals and drugs administered. We also used chart abstraction to resolve suspected data errors.

Variables were added to identify regimen change (including new regimen and date of change), drug discontinuation, those who completed treatment elsewhere (and whose treatment data required censoring), metastatic disease at presentation (and requiring exclusion), another indication for cytotoxic treatment (e.g., treatment of a subsequent malignancy or other chronic disease) and enrollment in randomized-controlled trials (RCTs). Re-abstraction was conducted if it was determined that additional review would clarify the intended regimen. An example of regimens can be seen in eFigure 1.

Additional Considerations

Some participants received cytotoxic agents not included at all in the NCCN drug combinations, including vinorelbine, ado-trastuzumab, protein-bound paclitaxel and oral drugs such as capecitabine and everolimus; they were categorized into new drug combinations. If drugs given were indicated for metastatic disease, medical chart abstraction was undertaken to confirm staging and thus study eligibility.

KPWA

Abstraction was conducted at KPWA to collect all data on chemotherapy drugs, doses and dates of administration. The algorithmic approach described above for KPNC was then applied to data on chemotherapy received at KPWA, and abstracted information was reviewed for remaining participants, aligning with the KPNC process as much as possible. Additional new NGRs were identified using KPWA’s abstracted data and were described using the same process as at KPNC.

Non-chemotherapy data

Clinical and sociodemographic data were collected from the EHR. Data on tumor characteristics and treatment variables were collected from the SEER tumor registry. Median household income was collected at neighborhood level. Participants were categorized as post-menopausal if they were ≥55 years, or <55 with evidence of bilateral oophorectomy.

Statistical Methods

Participants were described by regimen determination method: i) algorithm, ii) abstraction, and iii) unable to be determined, overall and by population characteristics: age at diagnosis, race/ethnicity, median neighborhood household income, body mass index (BMI), Charlson comorbidity index (CCI), menopausal status, diagnosis year, stage, grade, tumor size, number of nodes, hormone-receptor positivity, HER2-status, surgery, endocrine therapy, radiotherapy, and study site. Distributions of participants’ regimen determination (algorithm vs abstraction vs unable to be determined) by drug combination, as well as the distribution of regimens (NCCN vs algorithm-identified NGR vs abstraction-identified NGR) were also described. To evaluate the associations of patient factors with regimen determination method (algorithm vs abstraction), analyses were conducted to estimate prevalence ratios (PR) and associated 95% Confidence Intervals (95% CI) using Poisson regression with the log-link function and robust variance estimation. Minimally-adjusted models were adjusted for age, stage and study site (KPNC or KPWA). Multivariable models were further adjusted for all factors that were statistically significant when evaluated individually in minimally-adjusted models.

Validation

To validate the accuracy of the regimen categorization process using abstracted data, a second co-author re-categorized a sample of participants. Among those treated at KPNC, 5% of abstracted participants in each drug combination were randomly selected for validation.

We evaluated concordance on whether the regimen could be determined and, if so, the intended drug combination. Assuming agreement on the drug combination, we assessed concordance on the intended administration schedule and also on the presence of regimen change, and if so, the date of change and new regimen.

Only the original NCCN guidelines and algorithm-NGRs were made available to the validator. Where the validator identified the use of new NGRs, they defined them de novo, replicating what was done in the overall study.

Results

Of the 13,231 women receiving chemotherapy, 57.0% were non-Hispanic white, 15.4% Hispanic, 8.2% non-Hispanic black and 17.9% Asian (Table 1). Intended regimen was identified by algorithm for 10,213 (77%) women. Participants with ER- and PR- status and HER2+ status were over-represented in those whose regimen was determined via abstraction and those unable to be determined.

Table 1:

Population characteristics by method of regimen determination

| Among those receiving chemotherapy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Participants who received chemotherapy N,% | Participants whose regimen was determined via algorithm N, % | Participants whose regimen was determined via abstraction N,% | Regimen not determined N,% |

| TOTAL | 13,231 (100%) | 10,213 (77%) | 2,416 (18%) | 602 (4.5%) |

| Sociodemographics | ||||

| Age at diagnosis (years) | ||||

| 18–39 | 1,199 (9.1%) | 861 (8.4%) | 227 (10.7%) | 111 (12.5%) |

| 40–49 | 3,260 (24.6%) | 2,515 (24.6%) | 543 (25.5%) | 202 (22.8%) |

| 50–64 | 6,151 (46.5%) | 4,817 (47.2%) | 952 (44.7%) | 382 (43.1%) |

| 65–79 | 2,535 (19.2%) | 1,980 (19.4%) | 394 (18.5%) | 161 (18.2%) |

| 80+ | 86 (0.6%) | 40 (0.4%) | 15 (0.7%) | 31 (3.5%) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 7,545 (57.0%) | 5,788 (56.7%) | 1,246 (58.5%) | 511 (57.6%) |

| Hispanic | 2,036 (15.4%) | 1,574 (15.4%) | 312 (14.6%) | 150 (16.9%) |

| Non-Hispanic Black or African American | 1,079 (8.2%) | 848 (8.3%) | 162 (7.6%) | 69 (7.8%) |

| Asian | 2,362 (17.9%) | 1,844 (18.1%) | 372 (17.5%) | 146 (16.5%) |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 43 (0.3%) | 36 (0.4%) | 5 (0.2%) | 2 (0.2%) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 112 (0.8%) | 87 (0.9%) | 19 (0.9%) | 6 (0.7%) |

| More than once race | 24 (0.2%) | 16 (0.2%) | 7 (0.3%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| Unknown/missing | 30 (0.2%) | 20 (0.2%) | 8 (0.4%) | 2 (0.2%) |

| Site b | ||||

| KPNC | 12,301 (93.0%) | 9,648 (94.5%) | 1,834 (86.1%) | 819 (92.3%) |

| KPWA | 930 (7.0%) | 565 (5.5%) | 297 (13.9%) | 68 (7.7%) |

| Neighborhood level SES | ||||

| Median Neighbourhood Household Income a | ||||

| Q1: <66,275 | 3,241 (24.5%) | 2,418 (23.7%) | 583 (27.4%) | 240 (27.1%) |

| Q2: $66,275-<$89,072 | 3,237 (24.5%) | 2,491 (24.4%) | 521 (24.4%) | 225 (25.4%) |

| Q3: $89,072-<$116,923 | 3,388 (25.6%) | 2,598 (25.4%) | 572 (26.8%) | 218 (24.6%) |

| Q4: >$116,923 | 3,263 (24.7%) | 2,653 (26.0%) | 415 (19.5%) | 195 (22.0%) |

| Missing | 102 (0.8%) | 53 (0.5%) | 40 (1.9%) | 9 (1.0%) |

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| BMI at diagnosis(kg/m2) | ||||

| <18.5 | 137 (1.0%) | 100 (1.0%) | 19 (0.9%) | 18 (2.0%) |

| 18.5-<25 | 4,119 (31.1%) | 3,185 (31.2%) | 655 (30.7%) | 279 (31.5%) |

| 25-<30 | 4,111 (31.1%) | 3,199 (31.3%) | 635 (29.8%) | 277 (31.2%) |

| 30-<35 | 2,583 (19.5%) | 1,995 (19.5%) | 439 (20.6%) | 149 (16.8%) |

| 35+ | 2,177 (16.5%) | 1,679 (16.4%) | 358 (16.8%) | 140 (15.8%) |

| Missing | 104 (0.8%) | 55 (0.5%) | 25 (1.2%) | 24 (2.7%) |

| Charlson comorbidity index | ||||

| 0 | 10,028 (75.8%) | 7,772 (76.1%) | 1,599 (75.0%) | 657 (74.1%) |

| 1 | 2,093 (15.8%) | 1,612 (15.8%) | 354 (16.6%) | 127 (14.3%) |

| 2 | 619 (4.7%) | 478 (4.7%) | 88 (4.1%) | 53 (6.0%) |

| 3+ | 491 (3.7%) | 351 (3.4%) | 90 (4.2%) | 50 (5.6%) |

| Menopausal status | ||||

| Pre-menopausal | 6,491 (49.1%) | 4,978 (48.7%) | 1,086 (51.0%) | 427 (48.1%) |

| Post-menopausal | 6,740 (50.9%) | 5,235 (51.3%) | 1,045 (49.0%) | 460 (51.9%) |

| Tumor/cancer characteristics | ||||

| Year of diagnosis | ||||

| 2004–2007 | 1,933 (14.6%) | 1,271 (12.4%) | 432 (20.3%) | 230 (25.9%) |

| 2008–2011 | 3,719 (28.1%) | 2,831 (27.7%) | 603 (28.3%) | 285 (32.1%) |

| 2012–2015 | 3,872 (29.3%) | 3,137 (30.7%) | 508 (23.8%) | 227 (25.6%) |

| 2016–2019 | 3,707 (28.0%) | 2,974 (29.1%) | 588 (27.6%) | 145 (16.3%) |

| Stage | ||||

| Stage I | 4,258 (32.2%) | 3,428 (33.6%) | 616 (28.9%) | 214 (24.1%) |

| Stage II | 7,262 (54.9%) | 5,594 (54.8%) | 1,157 (54.3%) | 511 (57.6%) |

| Stage IIIA | 1,711 (12.9%) | 1,191 (11.7%) | 358 (16.8%) | 162 (18.3%) |

| Grade | ||||

| Grade I | 1,286 (9.7%) | 1,048 (10.3%) | 174 (8.2%) | 64 (7.2%) |

| Grade II | 5,422 (41.0%) | 4,321 (42.3%) | 798 (37.4%) | 303 (34.2%) |

| Grade III/IV | 6,150 (46.5%) | 4,573 (44.8%) | 1,083 (50.8%) | 494 (55.7%) |

| Grade unknown, not stated, or not applicable | 373 (2.8%) | 271 (2.7%) | 76 (3.6%) | 26 (2.9%) |

| Tumor size | ||||

| No mass or tumor found | 36 (0.3%) | 25 (0.2%) | 9 (0.4%) | 2 (0.2%) |

| Microinvasion | 24 (0.2%) | 13 (0.1%) | 8 (0.4%) | 3 (0.3%) |

| 0.1–0.5cm | 232 (1.8%) | 160 (1.6%) | 48 (2.3%) | 24 (2.7%) |

| 0.5->1cm | 1,056 (8.0%) | 838 (8.2%) | 166 (7.8%) | 52 (5.9%) |

| 1<−2cm | 4,798 (36.3%) | 3,793 (37.1%) | 709 (33.3%) | 296 (33.4%) |

| 2<−5cm | 6,153 (46.5%) | 4,738 (46.4%) | 1,000 (46.9%) | 415 (46.8%) |

| >5cm | 905 (6.8%) | 628 (6.1%) | 185 (8.7%) | 92 (10.4%) |

| Other/unknown | 27 (0.2%) | 18 (0.2%) | 6 (0.3%) | 3 (0.3%) |

| Number of nodes | ||||

| All nodes negative | 6,515 (49.2%) | 5,164 (50.6%) | 963 (45.2%) | 388 (43.7%) |

| 1–3 nodes | 4,806 (36.3%) | 3,728 (36.5%) | 767 (36.0%) | 311 (35.1%) |

| 4–9 nodes | 1,366 (10.3%) | 984 (9.6%) | 275 (12.9%) | 107 (12.1%) |

| 10+ nodes | 79 (0.6%) | 51 (0.5%) | 22 (1.0%) | 6 (0.7%) |

| Positive but number unknown | 268 (2.0%) | 166 (1.6%) | 72 (3.4%) | 30 (3.4%) |

| No nodes examined/unknown | 197 (1.5%) | 120 (1.2%) | 32 (1.5%) | 45 (5.1%) |

| Hormone-receptor positivity | ||||

| ER- and PR- | 3,765 (28.5%) | 2,759 (27.0%) | 664 (31.2%) | 342 (38.6%) |

| ER+ and/or PR+ | 9,446 (71.4%) | 7,440 (72.8%) | 1,462 (68.6%) | 544 (61.3%) |

| Borderline/not tested/unknown | 20 (0.2%) | 14 (0.1%) | 5 (0.2%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| HER2 positivity | ||||

| HER2- | 9,646 (72.9%) | 7,958 (77.9%) | 1,203 (56.5%) | 485 (54.7%) |

| HER2+ | 3,401 (25.7%) | 2,119 (20.7%) | 894 (42.0%) | 388 (43.7%) |

| Borderline | 102 (0.8%) | 80 (0.8%) | 16 (0.8%) | 6 (0.7%) |

| Not tested/unknown | 82 (0.6%) | 56 (0.5%) | 18 (0.8%) | 8 (0.9%) |

| Surgery | ||||

| No surgery | 276 (2.1%) | 165 (1.6%) | 62 (2.9%) | 49 (5.5%) |

| Mastectomy | 6,212 (47.0%) | 4,718 (46.2%) | 1,068 (50.1%) | 426 (48.0%) |

| Breast conserving surgery | 6,725 (50.8%) | 5,317 (52.1%) | 998 (46.8%) | 410 (46.2%) |

| Unknown type of surgery | 3 (0.0%) | 3 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Unknown if had surgery | 15 (0.1%) | 10 (0.1%) | 3 (0.1%) | 2 (0.2%) |

| Endocrine therapy | ||||

| No | 4,414 (33.4%) | 3,225 (31.6%) | 785 (36.8%) | 404 (45.5%) |

| Yes | 8,817 (66.6%) | 6,988 (68.4%) | 1,346 (63.2%) | 483 (54.5%) |

| Radiotherapy | ||||

| No | 7,414 (56.0%) | 5,583 (54.7%) | 1,243 (58.3%) | 588 (66.3%) |

| Yes | 5,379 (40.7%) | 4,300 (42.1%) | 808 (37.9%) | 271 (30.6%) |

| Missing | 438 (3.3%) | 330 (3.2%) | 80 (3.8%) | 28 (3.2%) |

Poverty-income ratio is a community level variable

Data for 2004–2006 only available for participants enrolled at KPWA and data for 2016– 2019 only available for participants enrolled at KPNC

NCCN guidelines describe 24 drug combinations for stage I-IIIA breast cancer, encompassing 50 dosing schedules (Table 2). During the algorithm development process, 21 additional NGRs were identified. A further 151 were identified during the abstraction process. Of the 172 NGRs, 111 were non-guideline administration schedules of guideline drug combinations, and 61 NGRs were non-guideline drug combinations (delivered to 300 women)., Among participants receiving doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide and paclitaxel and those receiving doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, paclitaxel and trastuzumab, 37 NGRs were identified. These drug combinations represent 52.8% of participants whose intended regimen could not be identified.

Table 2.

Chemotherapy regimens used for treatment of primary breast cancer

| Regimens | Study participants | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regimena | Number of regimens described in NCCN guidelinesb (number of regimens used) | Number of regimens additionally generated during algorithm development process | Number of regimens further generated during abstraction review process | Total regimens | Total number receiving each drug combination | Regimen determined via algorithm (n, %) | Regimen determined via abstraction (n, %) | Receiving drug combination but unable to be defined by intended subregimenc |

| Overall | 50 | 21 | 151 | 222 | 13,231 (100%) | 10,213 (77%) | 2,416 (18%) | 602 (4.5%) |

| AC | 2 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 756 (100%) | 669 (88%) | 77 (10%) | 10 (1.3%) |

| AC-T (DOC) | 2 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 347 (100%) | 256 (74%) | 68 (20%) | 23 (6.6%) |

| AC-T (DOC) - H | 1 | 1 | 9 | 11 | 23 (100%) | 15 (65%) | 7 (30%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| AC-T (DOC) - HP | 2 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 15 (100%) | 6 (40%) | 4 (27%) | 5 (33%) |

| FAC | 4 | 1 | 4 | 9 | 16 (100%) | 4 (25%) | 10 (63%) | 2 (13%) |

| ACMF | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AC-T (PAC) | 5 | 0 | 13 | 18 | 4,408 (100%) | 3,517 (80%) | 678 (15%) | 213 (4.8%) |

| AC- T (PAC)- H | 6 | 8 | 16 | 30 | 735 (100%) | 328 (45%) | 302 (41%) | 105 (14%) |

| AC- T (PAC) - HP | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 37 (100%) | 27 (73%) | 4 (11%) | 6 (16%) |

| FEC | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 37 (100%) | 28 (76%) | 1 (2.7%) | 8 (22%) |

| CMF | 1 | 4 | 7 | 12 | 192 (100%) | 86 (45%) | 97 (51%) | 9 (4.7%) |

| HER-TC | 2 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 127 (100%) | 83 (65%) | 36 (28%) | 8 (6.3%) |

| TCH | 2 | 0 | 4 | 6 | 1,274 (100%) | 1,003 (79%) | 255 (20%) | 16 (1.3%) |

| TCHP | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 566 (100%) | 329 (58%) | 205 (36%) | 32 (5.7%) |

| FAC-T(PAC) | 4 | 0 | 8 | 12 | 3 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| FEC-T(DOC) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 (100%) | 1 (25%) | 2 (50%) | 1 (25%) |

| FEC-T(PAC) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 5 (100%) | 1 (20%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (80%) |

| FEC-T(DOC)-HP | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 (100%) | 1 (50%) | 1 (50%) | 0 (0%) |

| FEC-T(PAC)-HP | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| TH | 2 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 542 (100%) | 414 (76%) | 115 (21%) | 13 (2.4%) |

| FEC-T(PAC)-H | 2 | 0 | 4 | 6 | 4 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (75%) | 1 (25%) |

| TC | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3,727 (100%) | 3,445 (92%) | 262 (7.0%) | 20 (0.5%) |

| EC | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ECMF | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Non-guideline drug combinationd | 0 | 0 | 61 | 61 | 300 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 300 (100%) |

| Unknown drug combination | NA | NA | NA | NA | 110 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 110 (100%) |

AC: doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide; AC + DOC: doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, docetaxel; AC-T (DOC) - H: doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, docetaxel, trastuzumab; AC-T (DOC) - HP: doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, docetaxel, trastuzumab, pertuzumab; FAC: 5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide; ACMF: doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, 5-fluorouracil, AC-T (PAC): doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, paclitaxel; AC- T (PAC)- H: doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, paclitaxel, trastuzumab; AC- T (PAC)- HP: doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, paclitaxel, trastuzumab, pertuzumab; FEC: 5-fluorouracil, epirubicin, cyclophosphamide; CMF: cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, 5-fluorouracil; HER-TC: cyclophosphamide, docetaxel, trastuzumab; TCH: docetaxel, carboplatin, trastuzumab; TCHP: docetaxel, carboplatin, trastuzumab, pertuzumab; FAC-T (PAC): 5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, paclitaxel; FEC-T (DOC): 5-fluorouracil, epirubicin, cyclophosphamide, docetaxel; FEC-T(PAC): 5-fluorouracil, epirubicin, cyclophosphamide, paclitaxel; FEC-T (DOC) -HP: 5-fluorouracil, epirubicin, cyclophosphamide, docetaxel, , trastuzumab, pertuzumab, FEC-T (PAC) -HP: 5-fluorouracil, epirubicin, cyclophosphamide, paclitaxel, , trastuzumab, pertuzumab; TH: paclitaxel, trastuzumab; FEC-T(PAC)-H: 5-fluorouracil, epirubicin, cyclophosphamide, paclitaxel, , trastuzumab; TC: cyclophosphamide, docetaxel

NCCN – National Comprehensive Cancer Network

Subregimen – describes the dosing schedule (including dose, cycle length and cycle interval) within a drug combination

Single agent regimens and drug combinations that were not described in the NCCN guidelines

NB: Those who underwent regimen change are grouped here in the drug combination they were initially intended to receive

In multivariable models, increasing age was associated with requiring abstraction for intended regimen identification, with individuals aged ≥80 years having a greater likelihood of requiring abstraction vs ages 18–39 years (PR:1.25; 95% CI:0.77–2.02)(p-trend=0.01)(Table 3). Higher median neighborhood household income was associated with a lower likelihood of requiring abstraction for regimen determination (PRQ4 vs Q1:0.76; 95% CI: 0.67–0.86; p-trend:<0.001). Higher stage was associated with a greater likelihood of requiring abstraction for regimen determination (PRstage IIIA vs Stage I:1.63; 95%CI:1.43–1.86; p-trend<0.001). Those with the smallest tumors (0.1–0.5cm) were more likely to require abstraction compared to those with tumors 0.5cm to 1cm (PR0.5–1cm: 0.94; 95%CI: 0.69–1.27). Those with 10+ positive nodes had an increased likelihood of requiring abstraction (PR:1.67; 95%CI:1.11–2.51) as compared to those with no positive nodes identified (p-value<0.001). Those with HER2+ disease were markedly more likely to require abstraction (PR:2.34; 95%CI:2.15–2.54). Patients diagnosed at KPWA had a higher likelihood of requiring use of abstracted information on intended regimen (PR:1.97; 95% CI:1.73–2.24). Participants diagnosed in later years were less likely to require abstraction (PR:0.73; 95% CI:0.63–0.84).

Table 3–

Adjusted prevalence ratios and 95% CI for regimen being determined via abstraction compared with being determined via algorithm, by population characteristic

| Characteristic | N = 10,613 (%) | Age, stage and site adjusted prevalence ratio (95% CI) | Multivariable adjusted prevalence ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (years) * | |||

| 18–39 | 932 (8.8) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| 40–49 | 2612 (24.6) | 0.80 (0.69, 0.93) | 0.86 (0.74, 0.99) |

| 50–64 | 4959 (46.7) | 0.72 (0.62, 0.82) | 0.77 (0.67, 0.88) |

| 65–79 | 2061 (19.4) | 0.74 (0.63, 0.87) | 0.80 (0.69, 0.94) |

| 80+ | 49 (0.5) | 1.35 (0.85, 2.15) | 1.25 (0.77, 2.02) |

| p-trend= 0.002 | p-trend = 0.01 | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 6029 (56.8) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| Hispanic | 1611 (15.2) | 0.93 (0.82, 1.06) | 0.92 (0.81, 1.04) |

| Non-Hispanic Black or African American | 890 (8.4) | 0.98 (0.84, 1.15) | 0.93 (0.80, 1.10) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 1934 (18.2) | 1.02 (0.90, 1.14) | 0.97 (0.86, 1.08) |

| Non-Hispanic Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 92 (0.9) | 0.99 (0.63, 1.56) | 0.98 (0.61, 1.57) |

| Non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaskan Native/More than one race/other | 57 (0.5) | 0.77 (0.47, 1.28) | 0.69 (0.44, 1.09) |

| p-value = 0.77 | p-value = 0.48 | ||

| Site * | |||

| KPNC | 9885 (93.1) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| KPWA | 728 (6.7) | 2.11 (1.88, 2.36) | 1.97 (1.73, 2.24) |

| p-value <0.001 | p-value < 0.001 | ||

| Median neighborhood household income a * | |||

| Q1: <$66,275 | 2652 (25.0) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| Q2: $66,275-<$89,072 | 2647 (24.9) | 0.92 (0.82, 1.03) | 0.93 (0.83, 1.04) |

| Q3: $89,072-<$116,923 | 2765 (26.1) | 1.03 (0.92, 1.15) | 0.99 (0.89, 1.11) |

| Q4: >$116,923 | 2549 (24.0) | 0.77 (0.68, 0.88) | 0.76 (0.67, 0.86) |

| p-trend = 0.002 | p-trend < 0.001 | ||

| BMI at diagnosis (kg/m2) | |||

| <18.5 | 108 (1.0) | 0.93 (0.60, 1.44) | 0.88 (0.58, 1.36) |

| 18.5-<25 | 3330 (31.4) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| 25-<30 | 3299 (31.1) | 0.95 (0.86, 1.06) | 0.98 (0.88, 1.09) |

| 30-<35 | 2125 (20.0) | 1.04 (0.92, 1.17) | 1.06 (0.94, 1.19) |

| 35+ | 1751 (16.5) | 1.00 (0.88, 1.14) | 1.04 (0.91, 1.18) |

| p-trend = 0.46 | p-trend = 0.29 | ||

| Charlson comorbidity index | |||

| 0 | 8015 (75.5) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| 1 | 1725 (16.3) | 1.11 (0.99, 1.24) | 1.10 (0.99, 1.23) |

| 2 | 490 (4.6) | 0.98 (0.78, 1.21) | 0.95 (0.77, 1.18) |

| 3+ | 383 (3.6) | 1.28 (1.03, 1.58) | 1.27 (1.03, 1.56) |

| p-trend = 0.04 | p-trend = 0.05 | ||

| Menopausal status | |||

| Pre-menopausal | 5197 (49.0) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| Post-menopausal | 5416 (51.0) | 0.95 (0.83, 1.08) | 0.96 (0.85, 1.09) |

| p-value = 0.40 | p-value = 0.56 | ||

| Year of diagnosis b * | |||

| 2004–2007 | 1306 (12.3) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| 2008–2011 | 2949 (27.8) | 0.73 (0.65, 0.83) | 0.74 (0.66, 0.83) |

| 2012–2015 | 3228 (30.4) | 0.60 (0.53, 0.68) | 0.59 (0.52, 0.66) |

| 2016–2019 | 3130 (24.5) | 0.73 (0.65, 0.83) | 0.73 (0.63, 0.84) |

| p-trend <0.001 | p-trend < 0.001 | ||

| Stage * | |||

| Stage I | 3516 (33.1) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| Stage II | 5796 (54.6) | 1.10 (0.99, 1.21) | 1.17 (1.06, 1.29) |

| Stage IIIA | 1301 (12.3) | 1.47 (1.29, 1.67) | 1.63 (1.43, 1.86) |

| p-trend <0.001 | p-trend < 0.001 | ||

| Grade * | |||

| Grade I | 1053 (9.9) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| Grade II | 4552 (42.9) | 1.14 (0.96, 1.34) | 0.98 (0.83, 1.15) |

| Grade III | 5008 (47.2) | 1.35 (1.15, 1.59) | 1.05 (0.89, 1.25) |

| p-trend <0.001 | p-trend = 0.19 | ||

| Tumor size * | |||

| 0.1–0.5cm | 176 (1.7) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| 0.5->1cm | 848 (8.0) | 0.75 (0.55, 1.01) | 0.94 (0.69, 1.27) |

| 1<−2cm | 3917 (36.9) | 0.69 (0.52, 0.90) | 0.91 (0.69, 1.20) |

| 2<−5cm | 4983 (47.0) | 0.68 (0.51, 0.90) | 0.85 (0.69, 1.20) |

| >5cm | 664 (6.3) | 0.70 (0.51, 0.97) | 0.96 (0.70, 1.32) |

| No mass or tumor found/microinvasion/other | 25 (0.2) | 2.02 (1.24, 3.29) | 2.25 (1.39, 3.64) |

| p-value <0.001 | p-value = 0.0003 | ||

| Number of nodes * | |||

| All nodes negative | 5316 (50.1) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| 1–3 nodes | 3883 (36.6) | 1.06 (0.96, 1.18) | 1.22 (1.10, 1.36) |

| 4–9 nodes | 1061 (10.0) | 1.19 (0.97, 1.47) | 1.34 (1.07, 1.66) |

| 10+ nodes | 64 (0.6) | 1.67 (1.11, 2.51) | 2.07 (1.42, 3.02) |

| Positive but number unknown | 187 (1.8) | 1.73 (1.35, 2.22) | 1.60 (1.25, 2.06) |

| No nodes examined | 102 (1.0) | 1.27 (0.85, 1.88) | 1.03 (0.66, 1.61) |

| p-value <0.001 | p-value < 0.001 | ||

| Hormone-receptor positivity * | |||

| ER- and PR- | 2951 (27.8) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| ER+ and/or PR+ | 7662 (72.2) | 0.84 (0.76, 0.91) | 0.93 (0.78, 1.10) |

| p-value <0.001 | p-value = 0.41 | ||

| HER2 positivity * | |||

| HER2- | 7905 (74.5) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| HER2+ | 2627 (24.8) | 2.35 (2.16, 2.56) | 2.34 (2.15, 2.54) |

| Borderline | 81 (0.8) | 1.11 (0.68, 1.80) | 1.20 (0.74, 1.95) |

| p-value <0.001 | p-value < 0.001 | ||

| Surgery Type * | |||

| No surgery | 150 (1.4) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| Mastectomy | 5057 (47.7) | 0.70 (0.53, 0.92) | 0.76 (0.59, 1.00) |

| Breast conserving surgery | 5406 (50.9) | 0.66 (0.50, 0.88) | 0.75 (0.57, 0.99) |

| p-value = 0.01 | p-value = 0.13 | ||

| Endocrine therapy * | |||

| No | 3432 (32.3) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| Yes | 7181 (67.7) | 0.84 (0.77, 0.92) | 0.98 (0.83, 1.15) |

| p-value <0.001 | p-value = 0.77 | ||

| Radiotherapy * | |||

| No | 6018 (56.7) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| Yes | 4595 (43.3) | 0.82 (0.75, 0.89) | 0.90 (0.80, 1.00) |

| p-value <0.001 | p-value = 0.06 |

Poverty-income ratio is a community level variable

Data for 2004–2006 only available for participants enrolled at KPWA and data for 2016– 2019 only available for participants enrolled at KPNC

Variables included in multivariable-adjusted analyses

The validation process was conducted on 180 KPNC participants. Results were concordant for 169 people of the 180 (93.9%) for regimen identification at drug combination level. Of the 139 receiving a guideline drug combination, 112 (81%) were concordant for administration schedule. Results were concordant on 82.3% of aspects of regimen change (including date, drug combination and administration schedule post-change. There were 2 common areas of discordance: 1) if a drug was stopped, there was ambiguity as to whether it was an early discontinuation or a regimen change to a combination with 1 fewer drug and 2) re-abstraction to err on the side of caution if intended regimen was ambiguous.

Discussion

The intended chemotherapy regimen could be determined via algorithm for over 75% of participants. Women over-represented in the group requiring abstraction for identification of the intended regimen included those at both ends of the age spectrum (18–39 years and ≥80 years), with the lowest neighborhood household income, greater comorbidity, and diagnosed with a higher stage and cancer grade. These factors point to women with additional considerations for chemotherapy prescribing, differences in risk status and concerns of more toxicity and adverse effects. Abstraction is an important aspect of determining intended regimen in this population.

The high prevalence of regimen determination via abstraction among HER2+ participants may reflect the variation seen in trastuzumab/pertuzumab administration, which are administered for up to 1 year, providing more opportunity for scheduling changes and a subsequent administration pattern that was not aligned with the algorithms. Prevalence of regimen determination via abstraction was substantially higher at KPWA as compared to KPNC, likely reflecting that algorithms were constructed around KPNC data. At KPWA, 60.8% were determined via algorithm however, showing these algorithms have the potential to save substantial abstraction time in novel settings. The algorithm also performed better in patients diagnosed in later years. Importantly, no variation was observed in by race/ethnicity.

NGRs were predominantly identified via abstraction. The majority of these were small deviations from NCCN-guideline recommendations, although some included drugs not typically used for early breast cancer.

We leveraged the size and granularity of the OBCD cohort to identify intended chemotherapy on a detailed level, which will enable large-scale, highly specific analyses in our cohort regarding dosing and other cohorts using this methodology, far beyond other studies which typically rely on claims data; this enables generation of much needed evidence for how variation in chemotherapy administration in real-world practice, reflective of populations under-represented in trials10, 11. Our process had involvement from team members with various disciplines (e.g., epidemiology, medical oncology, pharmacy, biostatistics), as well as familiarity with use of EHR data in cancer care delivery research. The validation process showed that manual regimen determination process was concordant between different persons.

Although our process was extremely comprehensive, due to complexity of the data, we encountered several limitations. If regimen was determined via algorithm alone, changes to intended regimen before treatment initiation, or an early discontinuation where chemotherapy received was indistinguishable from a guideline regimen, were unable to be captured. For drug combinations not in the NCCN guidelines, there was no blueprint to inform the regimen description (and subsequently define the intended doses and intervals); therefore, these regimens were described at the drug combination level without more granular information on the intended administration schedule. Our results reflect real-world data, and there is opportunity for measurement error. However, many steps were undertaken to ensure robust results; for example, we identified a very small number of individuals classified as HER2- who received trastuzumab and/or pertuzumab. HER2 status is obtained from cancer registries and largely extracted from diagnostic biopsy specimens; subsequent surgical specimens may result in reclassification. A sensitivity analysis (not shown) found no difference if HER2+ status was identified by biopsy or trastuzumab/pertuzumab receipt. As another example, we also performed validation of regimen determination using abstracted data; validating this process in other settings with a different cohort would be an important next step for this work. Although chemotherapy administered is described via a protocol code in Epic (the KP EHR system) in the Beacon oncology module rolled out midway through the study period, actual drugs, dosages, and cycle interval intended may not correspond exactly to the protocol selected. However, this may offer a potential avenue of further research to further reduce abstraction moving forward. Regimen determination was a time-intensive process, particularly at KPWA where abstraction was required to obtain data on chemotherapy received. This study is most applicable where granular chemotherapy data can be obtained via EHR, with abstraction reserved for clarification around intended regimen. We examine patients diagnosed and treated with primary stage I-IIIA breast cancer and no prior history of cancer to study a treatment-naïve population; this methodology would be best suited to treatment-naïve populations receiving chemotherapy where EHR data is available on drugs and doses delivered.

In summary, this study describes a comprehensive methodology to identify the intended chemotherapy for women with early-stage breast cancer, enabling large-scale real-world evidence generation. This methodology is widely applicable and can be applied to other data sources and primary cancer sites. Our work highlights the challenges of relying solely on computational methods to determine intended chemotherapy, as participants of higher stage and age and lowest income were more likely to require medical chart abstraction to determine intended treatment, suggesting the use of algorithms alone would exclude some of the most vulnerable study participants from analyses comparing chemotherapy intended to received, and introduce bias to our understanding of real-world chemotherapy administration and outcomes.

Future research on methods to operationalize chemotherapy data is required, to both reduce the burden of chart abstraction necessary, and to apply these principles in new populations. Establishing objective and realistic standards for the granularity of data that can be obtained through automated and structured data will be imperative in reducing the time spent operationalizing chemotherapy data in future studies.

This study demonstrates the effort required to develop a robust methodology to identify intended regimens in large, comprehensive datasets to inform chemotherapy research in the real-world setting.

Supplementary Material

eFigure 1: Visual depiction of intended regimens used to aid intended regimen identification for the drug combination doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and docetaxel

Context summary.

Key objective:

To describe a novel methodology for determining the intended chemotherapy regimen in stage I-IIIA breast cancer using algorithms and medical chart abstraction.

Knowledge generated:

This methodology allowed us to determine the intended regimen for 95.5% of patients receiving chemotherapy, 77% using algorithms and 18% using chart abstraction. We found that certain patient demographics were more likely to require chart abstraction to determine the intended regimen.

Relevance (written by Dr. Lin):

A comprehensive strategy that combines both iterative algorithm and chart abstraction can improve the quality of extracting chemotherapy regimens from electronic medical records. This methodology can facilitate the generation of quality real-world evidence at scale, for assessing process of care and treatment outcomes of cancer patients.

Acknowledgement of research support:

This work was supported by grants R37CA222793, U24CA171524, U01CA195565 and P30CA008748 from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health, as well as the Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Erin Bowles’s time was supported by the National Cancer Institute (R50CA211115).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: Dr. Bandera served as member of Pfizer’s Advisory Board to enhance minority participation in clinical trials (7/2021-8/2023). Dr. Liu served as member of Pfizer’s think tank think tank on real-world evidence sponsored by Pfizer on 11/28/23. Dr. Liu’s research funding (inst) unrelated to this current work: Genentech, AstraZeneca, Exact Sciences, Biotheranostics, and Beigene. Other authors have no COI to declare.

References

- 1.Rivera DR, Henk HJ, Garrett-Mayer E, et al. : The Friends of Cancer Research Real-World Data Collaboration Pilot 2.0: Methodological Recommendations from Oncology Case Studies. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 111:283, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ross TR, Ng D, Brown JS, et al. : The HMO Research Network Virtual Data Warehouse: A Public Data Model to Support Collaboration. EGEMS (Wash DC) 2:1049, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ritzwoller DP, Carroll NM, Delate T, et al. : Patterns and predictors of first-line chemotherapy use among adults with advanced non-small cell lung cancer in the cancer research network. Lung Cancer 78:245–252, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ritzwoller DP, Carroll NM, Delate T, et al. : Comparative Effectiveness of Adjunctive Bevacizumab for Advanced Lung Cancer: The Cancer Research Network Experience. J Thorac Oncol 9:692–701, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geiger AM, Buist DSM, Greene SM, et al. : Survivorship research based in integrated healthcare delivery systems: the Cancer Research Network. Cancer 112:2617–2626, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowles EJA, Wellman R, Feigelson HS, et al. : Risk of Heart Failure in Breast Cancer Patients After Anthracycline and Trastuzumab Treatment: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J Natl Cancer Inst 104:1293–1305, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Institutes of Health: About the SEER Program. Surveillance, Epidemiolgoy and End Results Program (SEER) https://seer.cancer.gov/indexhtml

- 8.Boudreau DM, Yu O, Chubak J, et al. : Comparative safety of cardiovascular medication use and breast cancer outcomes among women with early stage breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 144:405–416, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Detail Guidelines [Internet]. NCCN [cited 2023 Mar 15] Available from: https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh H, Kanapuru B, Smith C, et al. : FDA analysis of enrollment of older adults in clinical trials for cancer drug registration: A 10-year experience by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. JCO 35:10009–10009, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gray E, Marti J, Wyatt JC, et al. : Chemotherapy effectiveness in trial-underrepresented groups with early breast cancer: A retrospective cohort study. PLOS Medicine 16:e1003006, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1: Visual depiction of intended regimens used to aid intended regimen identification for the drug combination doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and docetaxel