Achievement of hemostasis is associated with significant coagulation, transfusion volumes and mortality benefits. Early whole blood resuscitation is associated with a greater independent odds of achieving hemostasis and at an earlier time point over the first 4 hours.

KEY WORDS: Hemostasis, whole blood, low titer, shock

Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Whole blood resuscitation is associated with survival benefits in observational cohort studies. The mechanisms responsible for outcome benefits have not been adequately determined. We sought to characterize the achievement of hemostasis across patients receiving early whole blood versus component resuscitation. We hypothesized that achieving hemostasis would be associated with outcome benefits and patients receiving whole blood would be more likely to achieve hemostasis.

METHODS

We performed a post hoc retrospective secondary analysis of data from a recent prospective observational cohort study comparing early whole blood and component resuscitation in patients at risk of hemorrhagic shock. Achievement of hemostasis was defined by receiving a single unit of blood or less, including whole blood or red cells, in any 60-minute period, over the first 4 hours from the time of arrival. Time-to-event analysis with log-rank comparison and regression modeling were used to determine the independent benefits of achieving hemostasis and whether achieving hemostasis was associated with whole blood resuscitation.

RESULTS

For the current analysis, 1,047 patients met the inclusion criteria for the study. When we compared patients who achieved hemostasis versus those who did not, achievement of hemostasis had significantly more hemostatic coagulation parameters, had lower transfusion requirements, and was independently associated with 4-hour, 24-hour and 28-day survival. Whole blood patients were significantly more likely to achieve hemostasis (88.9% vs. 81.1%, p < 0.001). Whole blood patients achieved hemostasis earlier (log-rank χ2 = 8.2, p < 0.01) and were independently associated with over twofold greater odds of achieving hemostasis (odds ratio, 2.4; 95% confidence interval, 1.6–3.7; p < 0.001).

CONCLUSION

Achievement of hemostasis is associated with significant outcome benefits. Early whole blood resuscitation is associated with a greater independent odds of achieving hemostasis and at an earlier time point. Reaching a nadir transfusion rate early following injury represents a possible mechanism of whole blood resuscitation and its attributable outcome benefits.

LEVEL OF EVIDENCE

Therapeutic/Care Management; Level III.

Management practices for the severely injured patient population have evolved over the last two decades.1–5 Early interventions in both the prehospital phase of care and soon after arrival to definitive trauma care have driven a significant portion of these outcome improvements.6–12 Whole blood resuscitation has returned to prominence13 and has been demonstrated to be associated with survival benefits in multiple recent observational cohort studies.14–21 Although whole blood has been hypothesized to reduce overall transfusion requirements and may simplify the logistics of early large volume resuscitation, the underlying mechanisms responsible for attributable outcome benefits have not been adequately characterized.4,15,22

Shock, endotheliopathy, and resultant coagulopathy contribute to ongoing blood loss and the need for persistent blood transfusion. Damage-control resuscitation improves outcomes postinjury through balanced blood component resuscitation, minimization of crystalloid, prevention of coagulopathy, and potential mitigation of downstream effects of shock and endothelial injury.5,23,24 Early low-titer type O whole blood (LTOWB) resuscitation, considered the definitive damage-control resuscitation product, may reduce the sequelae of hemorrhage and promote the achievement of hemostasis.5,15,23–25 Achieving early hemostasis based upon a nadir transfusion velocity in those requiring surgical intervention affords the patient a chance to progress beyond the operating theater and transfer their care to the intensive care unit environment where ongoing monitoring and organ dysfunction treatment can continue.16,23,26

We sought to characterize the achievement of hemostasis via a post hoc retrospective secondary analysis of data derived from a prospective observational cohort analysis of patients who received either early LTOWB resuscitation or component resuscitation alone who were at risk of hemorrhagic shock. We hypothesized that patients achieving early hemostasis defined by a nadir transfusion velocity would be associated with outcome benefits and patients receiving early LTOWB transfusion would be more likely to achieve hemostasis relative to receiving component resuscitation alone.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

We performed a secondary analysis of data derived from a recently completed prospective observational cohort study that compared early LTOWB resuscitation to component resuscitation in patients with hemorrhagic shock.16 The primary study was performed using seven level 1 trauma centers participating in the Linking Investigations in Trauma and Emergency Services (LITES; www.litesnetwork.org) clinical trials network. The STROBE checklist and guidelines were followed for observational studies (Supplementary Digital Content, Supplementary Data 1, http://links.lww.com/TA/E230). Ethical approval for the primary study and any secondary analyses were obtained using single institutional review board approval from the University of Pittsburgh and the Human Research Protection Office of the Department of Defense.

Inclusion criteria for the cohort study were injured patients at risk of massive transfusion who met the Assessment of Blood Consumption criteria27,28 (two or more of the following: 1, hypotension (systolic blood pressure, ≤90 mm Hg); 2, penetrating mechanism of injury; 3, positive Focused Assessment for the Sonography of Trauma examination; 4, heart rate, ≥120) and who, within 60 minutes of arrival, required both blood/blood component transfusion and required hemorrhage control procedures in the operating room or interventional radiology suite. Patients with qualifying vital signs and/or blood product transfusion, which occurred in the prehospital phase of care, also met the inclusion criteria. A Focused Assessment for the Sonography of Trauma examination, which was deferred because of the expedient transport to the operating room, was considered as meeting one of the Assessment of Blood Consumption criteria.27 Exclusion criteria included age younger than 15 years, penetrating brain injury, greater than 5 minutes of consecutive cardiopulmonary resuscitation, death prior to initiation of transfer to the operating room/interventional radiology for hemorrhage control procedures, known prisoners, and known pregnancy. Massive transfusion was defined as the need for at least 3 U or more of any red cell containing product within a 60-minute time period over the first 4 hours from arrival.29–32 Traumatic brain injury (TBI) definition required computed tomography–based diagnosis.

An LTOWB patient had to have received at least a single unit of whole blood during the prehospital or early in-hospital phase of care. Component patients received only component blood products during their early resuscitation. Transfusion volume of any resuscitation type was based upon patient need and the local site-specific transfusion practice. The use of LTOWB evolved over the time of the study and sites initially relying on component resuscitation switched to whole blood resuscitation. Whether a patient receives LTOWB or component at a particular site was based upon site-specific protocols and practice.

For the current secondary analysis, we focused on the initial 4-hour resuscitation period and the attainment of clinical hemostasis. Achievement of hemostasis based upon a nadir transfusion velocity was defined by receiving a single unit of blood or less, including whole blood or red cells, in any 60-minute period over the first 4 hours from the time of arrival.5,16,23,24,30 Time to hemostasis was defined in minutes, and patients were unable to reach hemostasis until 60 minutes into their resuscitation, based upon the definition used. Those patients who did not reach this nadir transfusion threshold or died within the initial 4 hours were considered to have not reached hemostasis.

The primary outcome for the current secondary analysis was the achievement of hemostasis defined by a nadir transfusion velocity over the initial 4 hours of resuscitation. Additional secondary outcomes included 4-hour mortality, 24-hour mortality, 28-day mortality, initial and 24-hour coagulation measurements, and 24-hour blood component transfusion requirements. Achievement of hemostasis and the timing of the event were compared across LTOWB and component resuscitation groups.

To assist in risk adjustment of the study cohort, we used regression modeling adjusting for those differences found across enrolled LTOWB and component patients including demographics, shock and injury severity, transfer origin, and prehospital injury characteristics/procedures. We further stratified the cohort based upon the individual patient prehospital predicted risk of in-hospital mortality using prehospital vital signs, prehospital interventions/procedures, and injury severity characteristics to see if the magnitude of effect varied based upon predicted mortality.16 For this subgroup where the probability of mortality was able to be calculated (n = 986), we assessed the regression model's predictive capabilities via receiver operating characteristic curve analysis.

Patients achieving hemostasis were first compared with those patients not achieving hemostasis in the initial 4 hours. This comparison was performed to characterize the outcome and its relevance to a severely injured cohort and risk of hemorrhagic shock. Coagulation measurements, transfusion requirements, and independent mortality risks at 4 hours, 24 hours, and 28 days were then characterized across those achieving hemostasis versus those who did not. Next, we compared enrolled patients who received early LTOWB and compared with those patients who received component resuscitation alone. Time-to-event analysis with log-rank comparison was then performed to determine if differences in the time to hemostasis across LTOWB and component groups existed. Logistic regression modeling was used to verify the independent associations across LTOWB and component resuscitation groups and the achievement of hemostasis after controlling for differences across the LTOWB and component groups. Models were then further stratified by the prehospital predicted mortality risk.16

Categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages and tested using Pearson's χ2 test. Continuous variables are expressed a medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) and tested using Mann-Whitney or Kruskal-Wallis testing, as appropriate. Statistical significance was determined at the probability (p) <0.05 level.

RESULTS

For the overall study, 1,051 patients at risk of hemorrhagic shock were enrolled with 1,047 patients having all data necessary for inclusion into the current secondary analysis (Supplementary Digital Content, Supplementary Fig. e1, http://links.lww.com/TA/E231). The study cohort had a median Injury Severity Score of 22 (IQR, 13–30) and were injured via a penetrating mechanism of injury 63% of the time. The enrolled cohort had a 4-hour, 24-hour, and 28-day mortality of 8%, 13%, and 17%, respectively, with over 70% of patients requiring massive transfusion as defined in the primary paper. The LTOWB patients had a higher incidence of severe injury (ISS >15, 73% vs. 67%, p = 0.4) and were more likely to require massive transfusion (74.4% vs. 64.8%, p < 0.01). Patients in the LTOWB transfusion group, for the primary study, received a median (IQR) of 2.0 (1.0–3.5) U of whole blood.16

When patients who achieved hemostasis were compared relative to those who did not, patients were similar in demographics and mechanisms of injury (achieved hemostasis vs. no achievement of hemostasis, n = 898 vs. n = 149; Table 1). Patients achieving hemostasis were more likely transferred from the scene of injury, had lower overall injury severity scores with less severe chest Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) scores and more severe extremity AIS scores. In addition, they were more likely to have documented TBI and corresponding higher head/neck AIS severity. Despite higher head/neck AIS severity, patients achieving hemostasis had higher Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) scores as compared with those who did not achieve hemostasis. Patients who did not achieve hemostasis were more likely to require prehospital intubation and receive prehospital blood product transfusion.

TABLE 1.

Demographics and Injury Characteristics Across Achieving Hemostasis Based Upon a Nadir Transfusion Velocity Versus Not Achieving Hemostasis

| Achieved Hemostasis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | All (N = 1,047) | Yes (n = 898) | No (n = 149) | p |

| Age, y | 35.0 [26.0–49.0] | 35.0 [26.0–50.0] | 32.0 [25.0–42.0] | 0.11 |

| Sex, male | 840 (80.2) | 713 (79.4) | 127 (85.2) | 0.10 |

| Race | 0.27 | |||

| White | 511 (48.8) | 440 (49.0) | 71 (47.7) | |

| Black | 364 (34.8) | 317 (35.3) | 47 (31.5) | |

| Other | 172 (16.4) | 141 (15.7) | 31 (20.8) | |

| Injury mechanism | ||||

| Blunt | 413 (39.4) | 358 (39.9) | 55 (36.9) | 0.49 |

| Fall | 50 (4.8) | 44 (4.9) | 6 (4.0) | 0.64 |

| Machinery | 3 (0.3) | 3 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.48 |

| MVC occupant ejected | 29 (2.8) | 28 (3.1) | 1 (0.7) | 0.09 |

| MVC occupant not ejected | 156 (14.9) | 139 (15.5) | 17 (11.4) | 0.20 |

| MVC motorcyclist | 72 (6.9) | 64 (7.1) | 8 (5.4) | 0.43 |

| MVC cyclist | 6 (0.6) | 5 (0.6) | 1 (0.7) | 0.86 |

| MVC pedestrian | 49 (4.7) | 33 (3.7) | 16 (10.7) | <0.01 |

| MVC ATV | 9 (0.9) | 8 (0.9) | 1 (0.7) | 0.79 |

| MVC not otherwise specified | 9 (0.9) | 7 (0.8) | 2 (1.3) | 0.49 |

| Struck by or against | 22 (2.1) | 18 (2.0) | 4 (2.7) | 0.59 |

| Other | 24 (2.3) | 22 (2.4) | 2 (1.3) | 0.40 |

| Penetrating | 655 (62.6) | 559 (62.2) | 96 (64.4) | 0.61 |

| Firearm | 472 (45.1) | 399 (44.4) | 73 (49.0) | 0.30 |

| Impalement | 8 (0.8) | 8 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0.25 |

| Stabbing | 123 (11.7) | 107 (11.9) | 16 (10.7) | 0.68 |

| Other | 57 (5.4) | 50 (5.6) | 7 (4.7) | 0.66 |

| Transfer origin | <0.01 | |||

| Scene | 849 (81.1) | 741 (82.5) | 108 (72.5) | |

| Outside ED | 198 (18.9) | 157 (17.5) | 41 (27.5) | |

| ISS | 22.0 [13.0–33.0] | 21.0 [13.0–32.0] | 26.0 [10.0–36.0] | 0.047 |

| >15 | 721 (70.2) | 616 (70.2) | 105 (70.5) | 0.94 |

| TBI (CT diagnosed) | 142 (13.6) | 131 (14.6) | 11 (7.4) | 0.02 |

| Head AIS | 0.00 [0.00–1.00] | 0.00 [0.00–2.00] | 0.00 [0.00–0.00] | 0.04 |

| >2 | 208 (20.3) | 187 (21.3) | 21 (14.1) | 0.04 |

| Chest AIS | 2.00 [0.00–3.00] | 2.00 [0.00–3.00] | 3.00 [0.00–4.00] | 0.01 |

| >2 | 458 (44.6) | 379 (43.2) | 79 (53.0) | 0.02 |

| Abdomen AIS | 3.00 [0.00–4.00] | 3.00 [0.00–4.00] | 3.00 [0.00–4.00] | 0.02 |

| >2 | 549 (53.5) | 463 (52.7) | 86 (57.7) | 0.3 |

| Extremity AIS | 2.00 [0.00–3.00] | 2.00 [0.00–3.00] | 0.00 [0.00–3.00] | <0.01 |

| >2 | 369 (36.0) | 328 (37.4) | 41 (27.7) | 0.02 |

| GCS | 14.0 [3.00–15.0] | 14.0 [6.00–15.0] | 10.0 [3.00–15.0] | <0.01 |

| <9 | 319 (30.8) | 250 (28.1) | 69 (47.6) | <0.01 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 100 [80.0–120] | 100 [82.0–119] | 110 [70.0–137] | 0.78 |

| <90 mm Hg | 356 (34.5) | 300 (33.6) | 56 (39.7) | 0.16 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 110 [89.0–128] | 110 [89.0–128] | 109 [87.0–130] | 0.72 |

| >100 bpm | 633 (60.7) | 545 (61.0) | 88 (59.1) | 0.65 |

| Shock index | 1.07 [0.82–1.37] | 1.08 [0.83–1.37] | 0.97 [0.72–1.38] | 0.11 |

| Any prehospital blood product | 348 (33.2) | 285 (31.7) | 63 (42.3) | 0.01 |

| Red blood cells | 248 (23.7) | 200 (22.3) | 48 (32.2) | <0.01 |

| Plasma | 67 (6.4) | 56 (6.2) | 11 (7.4) | 0.60 |

| Platelets | 28 (2.7) | 22 (2.4) | 6 (4.0) | 0.27 |

| Whole blood | 117 (11.2) | 98 (10.9) | 19 (12.8) | 0.51 |

| Any prehospital tranexamic acid | 50 (4.8) | 43 (4.8) | 7 (4.7) | 0.96 |

| Any prehospital crystalloid | 534 (51.0) | 462 (51.4) | 72 (48.3) | 0.48 |

| Prehospital/ED intubation | 401 (39.0) | 321 (36.4) | 80 (54.4) | <0.001 |

| Prehospital/ED CPR | 86 (8.4) | 55 (6.2) | 31 (21.5) | <0.001 |

| Prehospital pelvic binder | 78 (7.4) | 69 (7.7) | 9 (6.0) | 0.48 |

Data are presented as n (%) or median [Q1–Q3].

ATV, all terrain vehicle; bpm, beats per minute; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; CT, computed tomography; ED, emergency department; MVC, motor vehicle crash.

When we compared coagulation measurements and 4-hour and 24-hour transfusion requirements across patients who achieved hemostasis versus those who did not, achievement of hemostasis patients had significantly more hemostatic coagulation parameters via thromboelastography and lower overall transfusion requirements at both 4 hours and 24 hours (Table 2). When we independently analyzed 4-hour, 24-hour, and 28-day mortality, achieving hemostasis was independently associated with a significant lower risk of death at each time point including those with TBI at 24 hours (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Coagulation and Transfusion Measures by Achieving Hemostasis

| Achieved Hemostasis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | All (N = 1,047) | Yes (n = 898) | No (n = 149) | p |

| Coagulation parameter | ||||

| Within 4 h of arrival | ||||

| Prothrombin time, s | 15.1 [13.6–16.6] | 15.1 [13.6–16.6] | 14.6 [12.7–16.5] | 0.19 |

| International normalized ratio | 1.23 [1.15–1.40] | 1.24 [1.15–1.40] | 1.20 [1.10–1.40] | 0.17 |

| Rapid thromboelastography | ||||

| Kinetic time, m | 1.90 [1.50–2.70] | 1.90 [1.50–2.60] | 1.95 [1.70–3.30] | 0.05 |

| >2.5 | 200 (27.7) | 176 (26.6) | 24 (40.0) | 0.03 |

| α Angle, ° | 69.3 [63.9–73.0] | 69.4 [64.1–73.2] | 68.4 [57.0–72.4] | 0.04 |

| <60 | 113 (15.5) | 95 (14.3) | 18 (28.6) | <0.01 |

| Maximum amplitude, mm | 57.0 [51.6–61.6] | 57.0 [52.1–61.6] | 54.6 [42.6–60.7] | <0.01 |

| <55 | 289 (39.5) | 256 (38.3) | 33 (52.4) | 0.03 |

| Clot lysis at 30 m, % | 0.00 [0.00–0.40] | 0.00 [0.00–0.30] | 0.00 [0.00–0.90] | 0.01 |

| >3 | 16 (2.4) | 12 (1.9) | 4 (6.6) | 0.02 |

| Activated clotting time, s | 113 [105–128] | 113 [105–128] | 113 [105–128] | 0.67 |

| >128 | 117 (17.9) | 107 (18.0) | 10 (17.5) | 0.93 |

| Within 24 h of arrival | ||||

| Prothrombin time, s | 15.7 [14.3–17.0] | 15.8 [14.4–17.1] | 14.7 [13.8–16.0] | 0.02 |

| International normalized ratio | 1.30 [1.20–1.46] | 1.30 [1.20–1.46] | 1.23 [1.16–1.31] | 0.04 |

| Rapid thromboelastography | ||||

| Kinetic time, m | 1.30 [1.10–1.70] | 1.30 [1.10–1.70] | 1.20 [1.00–1.70] | 0.53 |

| >2.5 | 40 (6.1) | 36 (5.9) | 4 (9.5) | 0.34 |

| α Angle, ° | 74.4 [71.2–76.8] | 74.4 [71.3–76.8] | 74.4 [70.8–77.1] | 0.98 |

| <60 | 14 (2.1) | 11 (1.8) | 3 (7.1) | 0.02 |

| Maximum amplitude, mm | 63.9 [59.7–68.0] | 63.9 [59.6–67.9] | 64.1 [60.2–68.5] | 0.63 |

| <55 | 57 (8.6) | 53 (8.6) | 4 (9.5) | 0.83 |

| Clot lysis at 30 m, % | 0.20 [0.00–1.00] | 0.20 [0.00–0.90] | 0.65 [0.00–1.90] | <0.01 |

| >3 | 19 (3.0) | 16 (2.7) | 3 (7.1) | 0.10 |

| Activated clotting time, s | 113 [105–128] | 113 [105–128] | 105 [97.0–128] | 0.16 |

| >128 | 103 (16.7) | 97 (16.8) | 6 (15.4) | 0.82 |

| Transfusion requirement | ||||

| Within 4 h of arrival | ||||

| Whole, U | 1.00 [0.00–2.00] | 1.00 [0.00–2.00] | 0.00 [0.00–2.00] | 0.13 |

| Red cells, U | 4.00 [2.00–10.0] | 4.00 [1.00–9.00] | 12.0 [2.00–30.0] | <0.001 |

| Plasma, U | 3.00 [0.00–8.50] | 3.00 [0.00–8.00] | 10.0 [0.00–22.0] | <0.001 |

| Platelets, U | 0.00 [0.00–1.00] | 0.00 [0.00–1.00] | 1.00 [0.00–3.00] | <0.001 |

| Total, U | 9.00 [4.00–22.0] | 9.00 [4.00–19.0] | 26.5 [2.00–56.0] | <0.001 |

| Total, mL | 3,180 [1,330–6,880] | 2,990 [1,330–5,815] | 8,925 [990–18 k] | <0.001 |

| Within 24 h of arrival | ||||

| Whole, U | 1.00 [0.00–2.00] | 1.00 [0.00–2.00] | 0.00 [0.00–2.00] | 0.17 |

| Red cells, U | 5.00 [2.00–12.0] | 4.00 [2.00–10.0] | 12.0 [2.00–39.0] | <0.001 |

| Plasma, U | 4.00 [0.00–10.0] | 3.00 [0.00–9.00] | 10.0 [0.00–25.0] | <0.001 |

| Platelets, U | 1.00 [0.00–2.00] | 0.00 [0.00–2.00] | 1.00 [0.00–4.00] | <0.001 |

| Total, U | 11.0 [4.00–25.0] | 10.0 [4.00–22.0] | 26.5 [2.00–67.0] | <0.001 |

| Total, mL | 3,605 [1,500–8,090] | 3,225 [1,540–7,075] | 8,925 [990–21 k] | <0.001 |

Data are presented as n (%), mean ± SD, or median [Q1–Q3].

TABLE 3.

Mortality Measures by Achieving Hemostasis and Results of Logistic Regression Models Overall Cohort and Subgroup of Patients With Documented TBI

| Achieved Hemostasis | Logistic Model Results | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Unadjusted | Adjusted* | |||||||

| Measure | N | n (%) | N | n (%) | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p |

| Died within | ||||||||||

| 4 h | 887 | 14 (1.6) | 148 | 68 (45.9) | 0.02 | 0.01–0.04 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.01–0.04 | <0.01 |

| TBI subgroup | 126 | 5 (4.0) | 11 | 3 (27.3) | 0.11 | 0.02–0.55 | 0.007 | 0.14 | 0.01–2.37 | 0.18 |

| 24 h | 887 | 41 (4.6) | 148 | 90 (60.8) | 0.03 | 0.02–0.05 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.01–0.03 | <0.01 |

| TBI subgroup | 126 | 19 (15.1) | 11 | 6 (54.5) | 0.15 | 0.04–0.53 | 0.004 | 0.13 | 0.02–0.85 | 0.03 |

| 28 d | 887 | 83 (9.4) | 148 | 93 (62.8) | 0.06 | 0.04–0.09 | <0.001 | 0.04 | 0.02–0.07 | <0.001 |

| TBI subgroup | 126 | 30 (23.8) | 11 | 6 (54.5) | 0.26 | 0.07–0.91 | 0.036 | 0.24 | 0.04–1.41 | 0.11 |

*Adjusted for age, sex, Injury Severity Score, transfer origin, GCS, shock index, and intubation.

OR, odds ratio.

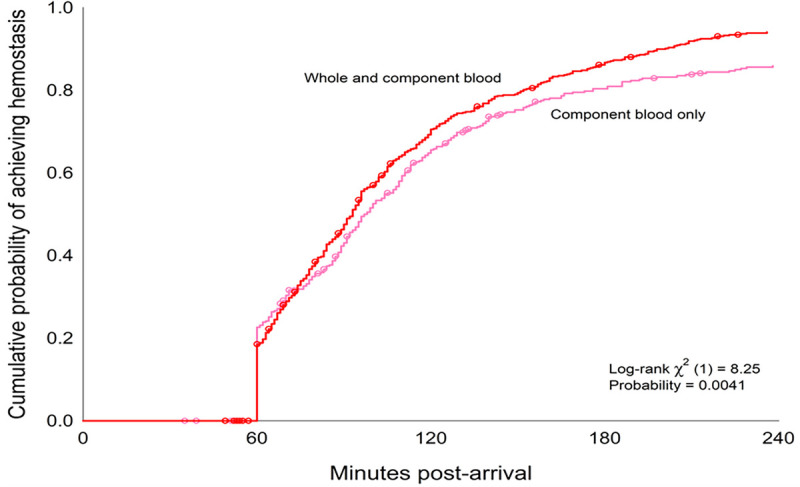

When LTOWB and component patients were compared, patients who received LTOWB were different across demographics, had higher injury severity, were more likely transferred from the scene, had lower GCS scores, and were more likely to receive prehospital blood and require intubation (Table 4). When the incidence of achieving hemostasis was compared across LTOWB (n = 623) and component (n = 424) transfusion groups, LTOWB patients were significantly more likely to achieve hemostasis (88.9% vs. 81.1%, p < 0.001). When time-to-event analysis was performed using Kaplan-Meier and log-rank comparison, LTOWB patients achieved hemostasis significantly earlier demonstrated by a shift to the left (log-rank χ2 = 8.2, p < 0.01, Fig. 1). Regression analyses verified, after adjusting for demographics, injury and shock severity, GCS, and transfer origin, that LTOWB resuscitation was independently associated with over twofold greater odds of achieving hemostasis as compared with component group patients (odds ratio, 2.4; 95% confidence interval, 1.6–3.7; p < 0.001).

TABLE 4.

Demographic and Injury Measures by Resuscitation Type

| Measure | LTOWB (n = 623) | Component (n = 424) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 35.0 [26.0–51.0] | 35.0 [24.0–47.0] | 0.14 |

| Sex, male | 545 (87.5) | 295 (69.6) | <0.001 |

| Race | <0.01 | ||

| White | 279 (44.8) | 232 (54.7) | |

| Black | 225 (36.1) | 139 (32.8) | |

| Other | 119 (19.1) | 53 (12.5) | |

| Injury mechanism | |||

| Blunt | 253 (40.6) | 160 (37.7) | 0.35 |

| Fall | 29 (4.7) | 21 (5.0) | 0.82 |

| Machinery | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) | 0.80 |

| MVC occupant ejected | 14 (2.2) | 15 (3.5) | 0.21 |

| MVC occupant not ejected | 94 (15.1) | 62 (14.6) | 0.84 |

| MVC motorcyclist | 53 (8.5) | 19 (4.5) | 0.01 |

| MVC cyclist | 4 (0.6) | 2 (0.5) | 0.72 |

| MVC pedestrian | 26 (4.2) | 23 (5.4) | 0.35 |

| MVC ATV | 5 (0.8) | 4 (0.9) | 0.81 |

| MVC not otherwise specified | 6 (1.0) | 3 (0.7) | 0.66 |

| Struck by or against | 14 (2.2) | 8 (1.9) | 0.69 |

| Other | 16 (2.6) | 8 (1.9) | 0.47 |

| Penetrating | 386 (62.0) | 269 (63.4) | 0.63 |

| Firearm | 281 (45.1) | 191 (45.0) | 0.99 |

| Impalement | 6 (1.0) | 2 (0.5) | 0.37 |

| Stabbing | 71 (11.4) | 52 (12.3) | 0.67 |

| Other | 31 (5.0) | 26 (6.1) | 0.42 |

| Transfer origin | <0.01 | ||

| Scene | 528 (84.8) | 321 (75.7) | |

| Outside ED | 95 (15.2) | 103 (24.3) | |

| ISS | 22.0 [14.0–33.0] | 21.0 [10.0–34.0] | 0.18 |

| >15 | 443 (72.7) | 278 (66.5) | 0.03 |

| TBI (CT diagnosed) | 99 (15.9) | 43 (10.1) | <0.01 |

| Head AIS | 0.00 [0.00–2.00] | 0.00 [0.00–0.00] | 0.19 |

| >2 | 133 (21.8) | 75 (17.9) | 0.13 |

| Chest AIS | 2.00 [0.00–3.00] | 2.00 [0.00–3.00] | 0.05 |

| >2 | 283 (46.5) | 175 (41.9) | 0.14 |

| Abdomen AIS | 3.00 [0.00–4.00] | 3.00 [0.00–4.00] | 0.24 |

| >2 | 320 (52.5) | 229 (54.8) | 0.48 |

| Extremity AIS | 2.00 [0.00–3.00] | 2.00 [0.00–3.00] | 0.73 |

| >2 | 220 (36.2) | 149 (35.6) | 0.84 |

| GCS | 14.0 [3.00–15.0] | 15.0 [7.00–15.0] | <0.01 |

| <9 | 210 (34.3) | 109 (25.7) | <0.01 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 98.0 [80.0–118] | 104 [82.0–122] | 0.16 |

| <90 mm Hg | 218 (35.6) | 138 (32.9) | 0.37 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 110 [89.5–130] | 108 [88.0–126] | 0.37 |

| >100 bpm | 373 (60.2) | 260 (61.6) | 0.64 |

| Shock index | 1.09 [0.84–1.40] | 1.01 [0.80–1.33] | 0.01 |

| Any prehospital blood product | 224 (36.0) | 124 (29.2) | 0.02 |

| Red blood cells | 127 (20.4) | 121 (28.5) | <0.01 |

| Plasma | 35 (5.6) | 32 (7.5) | 0.21 |

| Platelets | 12 (1.9) | 16 (3.8) | 0.07 |

| Any prehospital tranexamic acid | 35 (5.6) | 15 (3.5) | 0.12 |

| Any prehospital crystalloid | 309 (49.6) | 225 (53.1) | 0.27 |

| Prehospital/ED intubation | 259 (42.6) | 142 (33.7) | <0.01 |

| Prehospital/ED CPR | 54 (9.0) | 32 (7.6) | 0.44 |

| Prehospital pelvic binder | 47 (7.5) | 31 (7.3) | 0.89 |

Data are presented as n (%) or median [Q1–Q3].

ATV, all terrain vehicle; MVC, motor vehicle crash.

bpm, beats per minute; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; CT, computed tomography; ED, emergency department.

Figure 1.

Time-to-event analysis for achievement of hemostasis comparing LTOWB and component resuscitation patients.

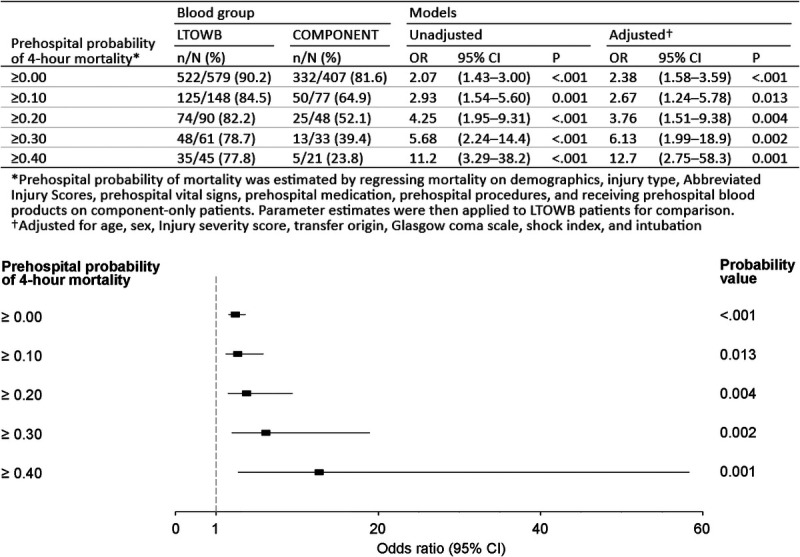

We then further stratified the cohort by the individual patients predicted prehospital probability of mortality estimated by using all relevant prehospital vital signs, prehospital interventions/procedures, and injury severity characteristics.16 This stratified analysis verified that, as the predicted prehospital mortality increased, the magnitude of the independent benefit attributable to whole blood and the achievement of hemostasis similarly increased (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Rates of achieving hemostasis and corresponding independent regression odds ratios for the achievement of hemostasis across LTOWB and component resuscitation groups stratified by patients predicted probability of mortality.

DISCUSSION

Appropriate characterization of the underlying mechanisms responsible for any of the beneficial effects of early whole blood resuscitation is essential, having the potential to promote advances and novel understanding, ultimately improving our management of hemorrhagic shock and its attributable morbidity and mortality.1,2,6,12,23,24,26,33–36

The results of the current analyses demonstrate an early hemostatic benefit associated with the use of LTOWB for hemorrhagic shock. Despite only a relatively low number of units of whole blood being transfused in the LTOWB resuscitation group, this difference in achieving hemostasis is robust and demonstrates an increasing independent magnitude of benefit as the patients predicted risk of mortality increased.16,23

In the primary cohort study, the LTOWB cohort had a greater rate of massive transfusion and was more commonly severely injured (ISS >15).16 Prior studies have demonstrated similar findings regarding whole blood patients and their injury severity.14,15,17 Despite these differences, the current analysis demonstrated that LTOWB resuscitation was independently associated with significantly greater odds of achieving hemostasis. Achievement of hemostasis was independently associated with improved mortality outcomes, improved coagulation measurements, and lower overall transfusion requirements at 24 hours.

Whole blood resuscitation is increasingly common across at trauma centers across the United States and internationally.1,14,22 A growing number of observational studies have documented a survival and transfusion benefit.14,15,17 Whole blood is also being used in the prehospital arena, prior to patients reaching definitive trauma care.14,16,37 As with other treatments in patients with hemorrhagic shock, the earlier and closer to the time of injury an intervention is provided, the significance and magnitude of benefit may increase. Randomized trials are ongoing, which may provide definitive outcome benefit estimates, data regarding the most appropriate environment for whole blood resuscitation to be initiated, and verification of safety across the storage age of the whole blood product.37,38

The current analysis does have limitations. First, it is a post hoc secondary analysis of a prospective cohort study with different aims and objectives that were not prespecified when the primary study was being planned and the data were being collected. The data are observational, and LTOWB and component groups were not randomized. The potential for unknown or unmeasured confounders exists and represents a major limitation in any observational study. The underlying reasons why patients received either LTOWB versus component remains a potential confounder. Patients who received LTOWB were more severely injured and had a higher rate of massive transfusion as defined in the primary study.16 There was a relatively high percentage of penetrating mechanism of injury enrolled, and despite attempting to adjust for all important cofounders, there may be differences in the response to LTOWB versus component resuscitation based upon mechanism of injury.39 Transfer origin, whether from the scene or outside emergency department, may alter the associations presented and requires further characterization.40,41 Although the definition for achieving hemostasis was defined initially in the primary study at 4 hours, the current analysis characterized the outcome via more complex analyses on a minute-to-minute basis and appropriately characterized the differences across LTOWB and component resuscitation groups and achievement of hemostasis. Achieving hemostasis as defined in the current analysis may be affected by injury characteristics including TBI and mechanism of injury. The definition used for achieving hemostasis in the current article requires validation in additional datasets and future studies. Hemostasis as defined may allow patients to get to the next stage of care, out of the operating theater, but may not alter long-term outcomes. Patients in the LTOWB resuscitation group received whole blood early in their in-hospital phase trauma center resuscitation. There are patients who received early red cell or outside emergency department component transfusion but received whole blood transfusion upon arrival to definitive trauma care and were deemed LTOWB patients. The laboratory measurements are associated with missingness, because of the logistics of care management for severely injured patients.42 Despite clinical outcome differences, there was a paucity of laboratory/coagulation measurement differences across the groups. Although the missingness did not differ across comparison groups and was relatively small, this could lead to outcome differences and represents a significant limitation.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, achievement of hemostasis is associated with significant coagulation, transfusion volumes, and mortality benefits. Early whole blood resuscitation, as compared with component resuscitation, was associated with achievement of hemostasis more commonly and at an earlier time over the first 4 hours. These relationships remain robust after controlling for differences in injury and shock severity and may be most relevant in those patients with the highest predicted risk of mortality based upon prehospital predictors. Reaching a nadir transfusion rate early following injury represents a possible mechanism of whole blood resuscitation and its attributable outcome benefits. Whole blood resuscitation is becoming incorporated into standard care following injury, and further characterization of its outcome benefits and underlying mechanisms of action can only benefit reducing the sequelae of hemorrhagic shock in those severely injured.

AUTHORSHIP

A.M.C., J.F.L. F.X.G., S.R.W., and J.L.S. had full access to all data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the analysis. All authors contributed to the writing and critical review of the article.

This primary study was funded by the Department of Defense, US Army Medical Research, and Development Command Grant number W81XWH-16-D-0024-0002.

DISCLOSURE

Conflicts of Interest: Author Disclosure forms have been supplied and are provided as Supplemental Digital Content (http://links.lww.com/TA/E232).

Footnotes

Published online: January 27, 2025.

This study was presented at the 83rd annual meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma and Clinical Congress of Acute Care Surgery, September 11–14, 2024, in Las Vegas, Nevada.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text, and links to the digital files are provided in the HTML text of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.jtrauma.com).

Contributor Information

Amanda M. Chipman, Email: chipmanam3@upmc.edu.

James F. Luther, Email: jim.luther@pitt.edu.

Francis X. Guyette, Email: guyefx@upmc.edu.

Bryan A. Cotton, Email: bryan.a.cotton@uth.tmc.edu.

Jeremy W. Cannon, Email: jeremy.cannon@pennmedicine.upenn.edu.

Martin A. Schreiber, Email: schreibm32@yahoo.com.

Ernest E. Moore, Email: ernest.moore@dhha.org.

Nicholas Namias, Email: nnamias@med.miami.edu.

Joseph P. Minei, Email: joseph.minei@utsouthwestern.edu.

Mark H. Yazer, Email: yazermh@upmc.edu.

Laura Vincent, Email: vincentl3@upmc.edu.

Abigail L. Cotton, Email: cottonal@upmc.edu.

Vikas Agarwal, Email: agarwalv@upmc.edu.

Joshua B. Brown, Email: brownjb@upmc.edu.

Christine M. Leeper, Email: leepercm@upmc.edu.

Matthew D. Neal, Email: nealm2@upmc.edu.

Raquel M. Forsythe, Email: forsytherm@upmc.edu.

Stephen R. Wisniewski, Email: stevewis@pitt.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cannon JW. Hemorrhagic shock. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(19):1852–1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deeb AP Guyette FX Daley BJ, et al. Time to early resuscitative intervention association with mortality in trauma patients at risk for hemorrhage. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2023;94(4):504–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gruen DS Guyette FX Brown JB, et al. Characterization of unexpected survivors following a prehospital plasma randomized trial. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020;89(5):908–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guyette FX, Sperry JL. Prehosptial low titer group O whole blood is feasible and safe: results of a prospective randomized pilot trial. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2022;93(5):e175–e176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holcomb JB Tilley BC Baraniuk S, et al. Transfusion of plasma, platelets, and red blood cells in a 1:1:1 vs a 1:1:2 ratio and mortality in patients with severe trauma: the PROPPR randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313(5):471–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gruen DS Guyette FX Brown JB, et al. Association of prehospital plasma with survival in patients with traumatic brain injury: a secondary analysis of the PAMPer cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2016869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Investigators PA-T, the ACTG, Gruen RL, et al. Prehospital tranexamic acid for severe trauma. N Engl J Med 2023;389(2):127–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rowell SE Meier EN McKnight B, et al. Effect of out-of-hospital tranexamic acid vs placebo on 6-month functional neurologic outcomes in patients with moderate or severe traumatic brain injury. JAMA. 2020;324(10):961–974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sperry JL Guyette FX Brown JB, et al. Prehospital plasma during air medical transport in trauma patients at risk for hemorrhagic shock. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(4):315–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guyette FX Brown JB Zenati MS, et al. Tranexamic acid during prehospital transport in patients at risk for hemorrhage after injury: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2020;156(1):11–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazzei M Donohue JK Schreiber M, et al. Prehospital tranexamic acid is associated with a survival benefit without an increase in complications: results of two harmonized randomized clinical trials. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2024;97:697–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li SR Guyette F Brown J, et al. Early prehospital tranexamic acid following injury is associated with a 30-day survival benefit: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2021;274(3):419–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morgan KM Abou Khalil E Feeney EV, et al. The efficacy of low-titer group O whole blood compared with component therapy in civilian trauma patients: a Meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2024;52(7):e390–e404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brill JB Tang B Hatton G, et al. Impact of incorporating whole blood into hemorrhagic shock resuscitation: analysis of 1,377 consecutive trauma patients receiving emergency-release uncrossmatched blood products. J Am Coll Surg. 2022;234(4):408–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hazelton JP Ssentongo AE Oh JS, et al. Use of cold-stored whole blood is associated with improved mortality in hemostatic resuscitation of major bleeding: a multicenter study. Ann Surg. 2022;276(4):579–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sperry JL Cotton BA Luther JF, et al. Whole blood resuscitation and association with survival in injured patients with an elevated probability of mortality. J Am Coll Surg. 2023;237(2):206–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Torres CM, Kent A, Scantling D, Joseph B, Haut ER, Sakran JV. Association of whole blood with survival among patients presenting with severe hemorrhage in US and Canadian adult civilian trauma centers. JAMA Surg. 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seheult JN Bahr M Anto V, et al. Safety profile of uncrossmatched, cold-stored, low-titer, group O+ whole blood in civilian trauma patients. Transfusion. 2018;58(10):2280–2288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guyette FX Zenati M Triulzi DJ, et al. Prehospital low titer group O whole blood is feasible and safe: results of a prospective randomized pilot trial. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2022;92(5):839–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaines BA Yazer MH Triulzi DJ, et al. Low titer group O whole blood in injured children requiring massive transfusion. Ann Surg. 2021;277:e919–e924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lammers D Hu P Rokayak O, et al. Preferential whole blood transfusion during the early resuscitation period is associated with decreased mortality and transfusion requirements in traumatically injured patients. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2024;9(1):e001358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leeper CM, Yazer MH, Neal MD. Whole-blood resuscitation of injured patients: innovating from the past. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(8):771–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang R Kerby JD Kalkwarf KJ, et al. Earlier time to hemostasis is associated with decreased mortality and rate of complications: results from the pragmatic randomized optimal platelet and plasma ratio trial. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019;87(2):342–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cardenas JC Zhang X Fox EE, et al. Platelet transfusions improve hemostasis and survival in a substudy of the prospective, randomized PROPPR trial. Blood Adv. 2018;2(14):1696–1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sperry JL, Brown JB. Whole-blood resuscitation following traumatic injury and hemorrhagic shock-should it be standard care? JAMA Surg. 2023;158(5):540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holcomb JB Moore EE Sperry JL, et al. Evidence-based and clinically relevant outcomes for hemorrhage control trauma trials. Ann Surg. 2021;273(3):395–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cotton BA Dossett LA Haut ER, et al. Multicenter validation of a simplified score to predict massive transfusion in trauma. J Trauma. 2010;69(Suppl 1):S33–S39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nunez TC, Voskresensky IV, Dossett LA, Shinall R, Dutton WD, Cotton BA. Early prediction of massive transfusion in trauma: simple as ABC (assessment of blood consumption)? J Trauma. 2009;66(2):346–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sim ES Guyette FX Brown JB, et al. Massive transfusion and the response to prehospital plasma: it is all in how you define it. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020;89(1):43–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Savage SA, Sumislawski JJ, Zarzaur BL, Dutton WP, Croce MA, Fabian TC. The new metric to define large-volume hemorrhage: results of a prospective study of the critical administration threshold. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78(2):224–229; discussion 229–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Savage SA, Zarzaur BL, Croce MA, Fabian TC. Time matters in 1:1 resuscitations: concurrent administration of blood: plasma and risk of death. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;77(6):833–837; discussion 837–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Savage SA, Zarzaur BL, Croce MA, Fabian TC. Redefining massive transfusion when every second counts. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74(2):396–400; discussion 400–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fox EE, Holcomb JB, Wade CE, Bulger EM, Tilley BC, Group PS. Earlier endpoints are required for hemorrhagic shock trials among severely injured patients. Shock. 2017;47(5):567–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gruen DS Brown JB Guyette FX, et al. Prehospital plasma is associated with distinct biomarker expression following injury. JCI Insight. 2020;5(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gruen DS Brown JB Guyette FX, et al. Prehospital tranexamic acid is associated with a dose-dependent decrease in syndecan-1 after trauma: a secondary analysis of a prospective randomized trial. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2023;95(5):642–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu J Moheimani H Li S, et al. High dimensional multiomics reveals unique characteristics of early plasma administration in polytrauma patients with TBI. Ann Surg. 2022;276(4):673–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sperry J, Type O. Whole Blood and Assessment of Age During Prehospital Resuscitation Trial (TOWAR). Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04684719. Accessed October 13, 2022.

- 38.Jansen JO, Holcomb JB, He W. Trauma Resuscitation with Group O Whole Blood Or Products (TROOP) Trial. Available at: https://reporter.nih.gov/search/8r9mHDG4ykCrl8NrnCHFAA/project-details/10449760. Accessed October 13, 2022.

- 39.Donohue JK Gruen DS Iyanna N, et al. Mechanism matters: mortality and endothelial cell damage marker differences between blunt and penetrating traumatic injuries across three prehospital clinical trials. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):2747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holena DN Wiebe DJ Carr BG, et al. Lead-time bias and interhospital transfer after injury: trauma center admission vital signs underpredict mortality in transferred trauma patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;224(3):255–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lewis RE Muluk SL Reitz KM, et al. Prehospital plasma is associated with survival principally in patients transferred from the scene of injury: a secondary analysis of the PAMPer trial. Surgery. 2022;172(4):1278–1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Donohue JK Iyanna N Lorence JM, et al. Missingness matters: a secondary analysis of thromboelastography measurements from a recent prehospital randomized tranexamic acid clinical trial. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2024;9(1):e001346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]