Abstract

Integrin-mediated cell adhesion and spreading enables cells to respond to extracellular stimuli for cellular functions. Using a gastric carcinoma cell line that is usually round in adhesion, we explored the mechanisms underlying the cell spreading process, separate from adhesion, and the biological consequences of the process. The cells exhibited spreading behavior through the collaboration of integrin-extracellular matrix interaction with a Smad-mediated transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1) pathway that is mediated by protein kinase Cδ (PKCδ). TGFβ1 treatment of the cells replated on extracellular matrix caused the expression and phosphorylation of PKCδ, which is required for expression and activation of integrins. Increased expression of integrins α2 and α3 correlated with the spreading, functioning in activation of focal adhesion molecules. Smad3, but not Smad2, overexpression enhanced the TGFβ1 effects. Furthermore, TGFβ1 treatment and PKCδ activity were required for increased motility on fibronectin and invasion through matrigel, indicating their correlation with the spreading behavior. Altogether, this study clearly evidenced that the signaling network, involving the Smad-dependent TGFβ pathway, PKCδ expression and phosphorylation, and integrin expression and activation, regulates cell spreading, motility, and invasion of the SNU16mAd gastric carcinoma cell variant.

Integrin-mediated adhesion to extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins allows cells to efficiently respond to extracellular stimuli for spreading, proliferation, migration, invasion, and gene transcription. This response is mediated by bidirectional signal transduction between extracellular and intracellular spaces that cross talks with other signal pathways (2, 3, 15, 22). Integrins, a family of cell adhesion receptors, are composed of an α and a β subunit. They transduce direct signaling via engagements with ECM proteins, leading to the regulation of downstream intracellular signaling molecules. They also function in collaborative (indirect) signaling, in which integrins cosignal with other membrane receptor-mediated signal pathways (e.g., growth factor receptors, G-protein coupled receptors, or the transforming growth factor β1 [TGFβ1] signaling pathway) (4, 8, 17, 25, 38, 43).

TGFβ1 is a multifunctional cytokine which inhibits cell growth and also mediates cell differentiation and metastasis. Activation of TGFβ1 receptor complex by TGFβ1 binding propagates intracellular signal transduction, involving Smad proteins, to regulate numerous developmental and homeostatic processes via regulations in gene induction (1). Smad7 is a major inhibitory Smad, which inhibits the TGFβ1-mediated phosphorylation of R-Smad2 and R-Smad3 through competition with Smad2/3 for binding to the TGFβ1 receptor (29). Recently, TGFβ1 was demonstrated to activate a variety of intracellular signaling molecules, including mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) (9, 12, 45) and small GTPases (28), either by Smad-dependent or -independent signaling pathways (7). TGFβ1 signaling modulates the expression of ECM proteins (14, 34) and integrins (27). Conversely, integrin-mediated signaling also regulates TGFβ1 expression levels (16, 21). Although this collaborative relationship between integrin- and TGFβ1-mediated signal pathways appears to be important for diverse cellular functions, mechanistic details underlying their collaboration and signaling network are largely unknown.

Protein kinase Cδ (PKCδ) is a member of a novel family of the PKC families and can be activated by either diacylglycerol or phorbol ester (44). PKCδ has been shown to exert antitumorigenic or tumorigenic effects, depending on the nature of cellular stimuli (37). Although PKCδ has been implicated in ECM synthesis, as shown in a couple of previous studies (13, 46), the evidence is not conclusive for its roles in TGFβ1-mediated regulation of cell functions.

So far, signaling networks consisting of integrins, TGFβ1, and PKC (especially PKCδ) have not been thoroughly investigated, especially for cell spreading and invasiveness. In this study, we have attempted to mechanistically explore the signaling networks which regulate the cell spreading process, separately from the adhesion process. A gastric carcinoma cell line that is usually round in adhesion was used, so that stimuli-induced spreading was investigated with regards to signal cross talks between TGFβ1, integrin, and PKC. We observed the signaling network in which Smad-dependent TGFβ1 signaling to integrin-mediated signaling is mediated by expression and activation of PKCδ, leading to cell spreading. Furthermore, we also investigated the biological consequences inherent in the signal network-mediated cell spreading.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

SNU16mAd cells, a variant cell line enriched with adherent cells, were obtained from subsequent cultures by collecting adherent cells among mostly anchorage-independent SNU16α5 cells (18). SNU16mAd cells were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2, in RPMI 1640 culture media containing 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum and 0.2 mg/ml G418.

Cell lysate preparation and Western blots.

Replating of SNU16mAd cells on diverse ECM-precoated dishes (10 μg/ml fibronectin [Fn], 10 μg/ml collagen type I, 10 μg/ml vitronectin, 10 μg/ml laminin I [Chemicon, Temecula, CA], or 10 μg/ml poly-l-lysine [PL; Sigma]) was done as explained previously (25). In certain cases, pharmacological inhibitors (12.5 μM GF-109203X or 10 μM rottlerin [10] [Calbiochem, San Diego, CA]) were pretreated, 30 min prior to the replating without or with TGFβ1 treatment. Upon replating, TGFβ1 (5 ng/ml; Chemicon) was added directly to the replating media, and the treatment lasted for 20 h or indicated periods. In cases of experiments with protein synthesis inhibition, 12 h after the replating, certain cells were treated with 10 μg/ml cycloheximide (Sigma), a protein synthesis inhibitor, with or without a concomitant 5 ng/ml TGFβ1, followed by additional incubation for 8 h (retreated every 4 h) for a total of 20 h of incubation on Fn. In certain cases, cells were premixed with 10 μg/ml anti-integrin α2 (P1E6), α3 (P1B5), or α5 (P1D6) antibodies (Chemicon), 30 min before the replating on Fn and a concomitant TGFβ1 treatment for 20 h. In cases in which adenovirus for either LacZ, FLAG-tagged Smad2, Smad3, Smad7 (25), PKCδ, or dominant-negative PKCα (K368R mutant) (kind gifts from J.-S. Chun, Gwangju Institute of Science and Technology, Gwangju, Korea) was separately infected, 24 h after the infection, cells were replated on ECM without or with TGFβ1 treatment for 20 h. In cases in which the TGFβ1 treatment periods were shorter (see Fig. 3A, 4C, and 6C), the indicated periods (x h) from the end of a total of 20 h of incubation were with TGFβ1, after certain incubations (20 − x h) without TGFβ1. In the case of PKCδ knockout via introduction of small interfering RNA (siRNA) (QIAGEN), siRNA against either PKCδ (to target AAG ATG AAG GAG GCG CTC AG; QIAGEN, catalog no. 1022453) or its negative control (AAT TCT CCG AAC GTG TCA CGT; QIAGEN, catalog no. 1022079) was separately transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), according to the manufacturer's protocols. The target sequence of PKCδ siRNA was unique for PKCδ according to NCBI BLAST searches. In cases of integrin α subunit overexpression, pSF2-human integrin α2, α3, or pcDMα5 (23) or pEF-PKCθ was separately transfected as above. Twenty-four hours after the transfection, cells were replated on either Fn-precoated dishes or cover glasses in the absence or presence of TGFβ1 treatment for 20 h. Cell lysates were prepared as described in the previous studies (24, 25). The lysates were used in Western blots using phospho-Y397FAK, phospho-Y925FAK, phospho-Y416Src, PKCα, PKCδ, c-Src (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), phospho-Y118paxillin, phospho-PKCs (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), FLAG (Sigma), integrins α2, α3, or α4, human laminin 5 (P3H9-2 clone) (Chemicon), focal adhesion kinase (FAK), paxillin, p130Cas, Nck, α-tubulin, α5 (BD Transduction Laboratories, San Jose, CA), or type I collagen (Biodesign, Saco, ME). In some cases, the membrane was stripped by incubation in a stripping buffer (62.5 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], and 100 mM β-mercaptoethanol) at 65°C for 30 min, washed for 1 h (3 times for 20 min) with Tris-based saline with 0.05% Tween-20 (TBST), reblocked with TBST containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) plus 1% skim milk proteins, and then reprobed with another primary antibody.

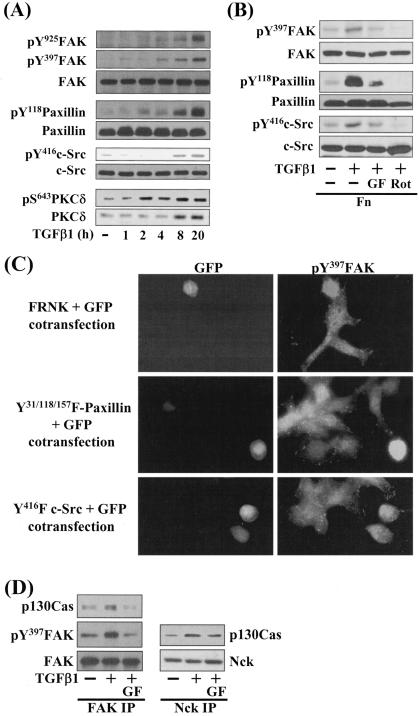

FIG. 3.

Integrin- and TGFβ1-mediated cell spreading on fibronectin involves phosphorylation of focal adhesion molecules. Manipulation of cells and preparation of cell lysates were done the same as for Fig. 2. Cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting or indirect immunofluorescent microscopy using primary antibodies against the indicated molecules. The data shown are representative of several experiments. (A) TGFβ1 treatment increased phosphorylation of the FA molecules and expression and Ser643 phosphorylation of PKCδ, in a time-dependent manner. Cells were treated with 5 ng/ml TGFβ1 for the indicated hours at the end of the 20-h incubation on fibronectin (i.e., 1 h indicates that TGFβ1 was directly added to the replating media after 19 h on Fn and the whole-cell extracts were prepared after one additional hour of incubation). (B) Integrin- and TGFβ1-mediated phosphorylation of the FA molecules was significantly reduced by PKC inhibition. Cells were pretreated with the indicated PKC inhibitors (12.5 μM GF-109203X [GF] or 10 μM rottlerin [Rot]), 30 min prior to the replating on Fn. (C) Expression of FRNK (dominant-negative FAK inhibitor), inactive c-Src (Y416F c-Src), or dominant-negative paxillin (Y31/118/157F paxillin) abolished the cell spreading. Cells were cotransfected with FRNK and GFP, Y416F c-Src and GFP, or Y31/118/157F paxillin and GFP. Two days later, cells were immunostained with rabbit anti-pY397FAK and then anti-rabbit IgG-conjugated TRITC. (D) FAK-p130Cas and p130Cas-Nck interactions correlated with the TGFβ1 effects. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with mouse monoclonal anti-FAK or Nck antibodies, and the immunoprecipitates were used in immunoblots using antibodies against the indicated molecules. The data shown were representative of three isolated experiments.

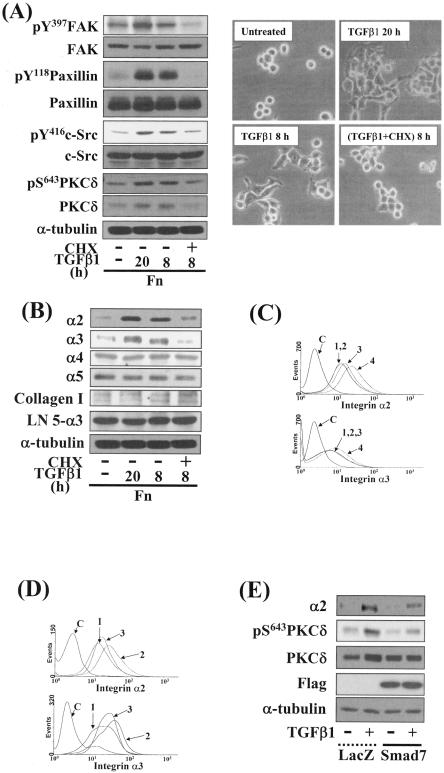

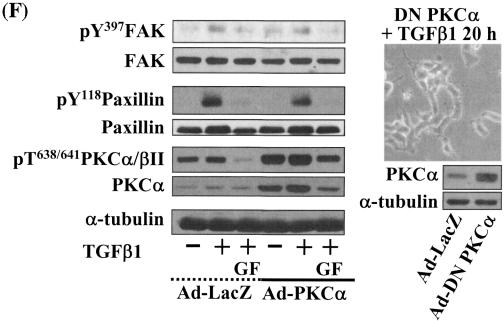

FIG. 4.

TGFβ1-, PKC-, and integrin-mediated cell spreading required new protein synthesis. (A) Inhibition of protein synthesis abolished phosphorylation of the FA molecules (left) and cell spreading (right) by TGFβ1 treatment. Cell replating and a concomitant TGFβ1 treatment were done, as described above. Twelve hours after the replating, certain cells were treated with 10 μg/ml cycloheximide every 4 h during an additional 8-h incubation with TGFβ1 treatment at 37°C. Cell images were taken using a phase-contrast microscope, and whole-cell lysates were prepared and used in Western blots as explained earlier. Data shown were representative of three independent experiments. (B) TGFβ1-mediated effects on integrins and ECM expression levels. Cell lysates were immunoblotted for antibodies against indicated integrins or collagen I or α3 chain of human laminin 5 (LN5-α3) (19, 35). Data shown were representative of three isolated experiments. (C) Increases in integrin α2 and α3 expression levels by TGFβ1 in a time-dependent manner. Cells from the indicated conditions were analyzed for integrin α2 or α3 expression by flow cytometry. Histograms are shown for controls with no primary antibody (C) and TGFβ1-treatment for 0 h (1), 8 h (2), 12 h (3), and 20 h (4). (D) Blockage of TGFβ1-induced integrin α2 or α3 expression by PKC inhibition. Histograms included are for no primary antibody control (C), no TGFβ1 treatment (1), TGFβ1 treatment for 20 h (2), and GF-109203X pretreatment 30 min prior to TGFβ1 treatment for 20 h (3). (E) The TGFβ1-mediated effects on integrin and PKCδ inductions were reduced by Smad7 overexpression. Twenty-four hours after the infection of cells with adenovirus encoding for β-galactosidase (LacZ) or Flag-Smad7, cells were replated on Fn in the absence or presence of TGFβ1 treatment for 20 h. Cell lysates were prepared and used in Western blots with antibodies against the indicated molecules. Data shown were representative of three independent experiments.

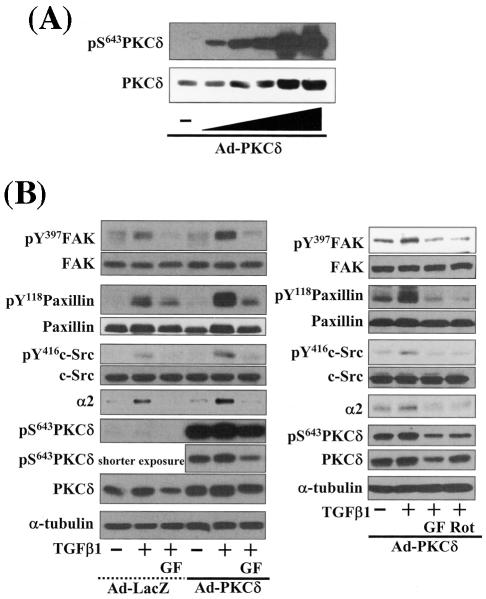

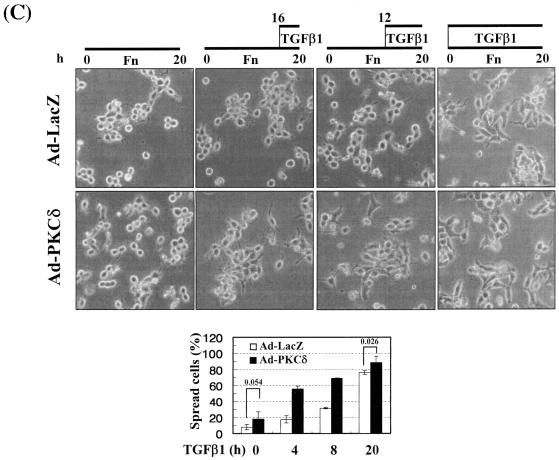

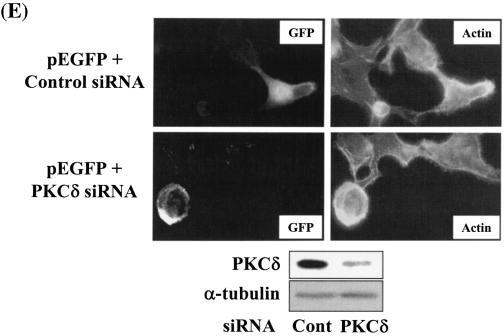

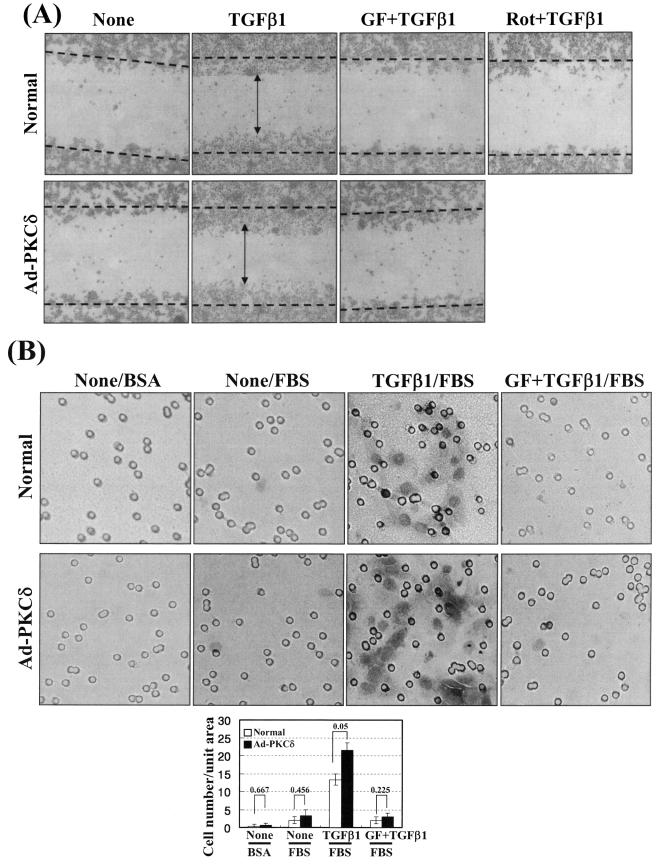

FIG. 6.

Integrin- and TGFβ1-mediated cell spreading requires PKCδ expression and activation. (A) Infection with adenovirus for PKCδ WT (Ad-PKCδ) increased the expression and Ser643 phosphorylation level of PKCδ. Cells were infected with various amounts of Ad-PKCδ. Two days later, cell lysates were prepared and used in Western blots for the indicated molecules. Data shown were representative of three independent experiments. (B) Increased activity and expression level of PKCδ by viral infection enhanced phosphorylation of the FA molecules. Cells were infected with a control adenoviral vector (Ad-LacZ) or Ad-PKCδ. Twenty-four hours later, cells were replated on Fn. Certain cells were pretreated with GF-109203X (GF) or Rottlerin (Rot), as described for Fig. 2. After the 20-h incubation on Fn, cell lysates were prepared and used in Western blots with antibodies against the indicated molecules. Data shown were representative of three different experiments. (C) Integrin- and TGFβ1-mediated cell spreading on Fn was accelerated by Ad-PKCδ infection. Cells infected with Ad-LacZ or Ad-PKCδ were replated on Fn with a concomitant TGFβ1 treatment for the indicated periods at the end of the 20-h incubation. Images were taken after the incubation on Fn. Quantitation of spread cells (cells with the longest distance from one end to the other end at least twice longer than the shortest distance) were counted from five isolated images of each experimental condition, and average values were graphed (mean ± standard deviation). A P value less than 0.05 from paired Student's t tests was considered significant. (D) Phosphorylation of the FA molecules was abolished by suppression of PKCδ protein. Cells were first transfected with siRNA to down-regulate PKCδ (PKCδ siRNA) or a control siRNA (Cont siRNA). Twenty-four hours after the transfection, cells were manipulated to be replated on Fn for the indicated experimental conditions. Cell lysates were then prepared and used for Western blots. Data shown represent three independent experiments. (E) Cell spreading was abolished by suppression of PKCδ protein. Cells were manipulated as explained for panel D, except that a part of the cells cotransfected with pcDNA3-GFP plus control siRNA or PKCδ siRNAwere replated on Fn-precoated cover glasses. Cells on cover glasses were processed for actin staining using phalloidin-conjugated TRITC. The other part of the cells was harvested after the 20-h incubation, and the lysates were immunoblotted using the indicated antibodies. Data shown were representative of three isolated experiments. (F) PKCα appeared not to be involved in the TGFβ1 effects. (Left) No enhancement of phosphorylation of the FA molecules upon PKCα overexpression. Cells were infected with either control virus (Ad-LacZ) or PKCα adenovirus (Ad-PKCα). One day after, cells were replated on Fn for the 20-h incubation under the indicated conditions. Lysates were prepared after the incubation and used in the immunoblots for the indicated molecules. (Right) Cells were infected with dominant-negative PKCα adenovirus (Ad-DN PKCα). Twenty-four hours later, cells were replated on Fn for the 20-h incubation in the presence of TGFβ1 treatment. After the incubation, the cell image was taken and then lysates were prepared for the immunoblots for the indicated molecules. Data shown were representative of 3 independent experiments.

Immunofluorescence microscopy.

Cells were first cotransfected with pcDNA3-GFP with either FAK-related nonkinase (FRNK, pBS-FRNK; a kind gift from Juliano L. Rudy, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC), pKH3-Y416F c-Src (18a), or pCMV-Y31/118/157F paxillin (31). Twenty-four hours later, cells were replated on 10 μg/ml Fn-precoated glass coverslips and incubated for 20 h at 37°C. After incubation, cells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS at room temperature, and washed three times with PBS. The cells were then incubated with anti-phospho-Y397FAK antibody for 1 h and washed three times with PBS (3 times for 10 min). Cells were then incubated with anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG)-conjugated TRITC (Chemicon) in a dark and humidified chamber for 1 h. In the case of actin staining, cells were cotransfected with pSF2-integrin α2, α3, or pcDMα5 (23), control siRNA (see above), or PKCδ siRNA and pcDNA3-GFP constructs, replated on Fn, fixed, and permeabilized as explained above. Cells were then stained with phalloidin-conjugated TRITC (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 1 h before washing three times with PBS and mounting with a mounting solution (DakoCytomation, Germany). Mounted samples were visualized by a fluorescent microscope.

Immunoprecipitation.

Cells were replated on Fn under diverse conditions as explained above. After the 20-h incubation, cells were washed with cold PBS and immediately lysed in an immunoprecipitation buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EGTA, 0.2 mM Na3VO4, 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1% Triton X-100, and 0.5% NP-40) on ice. The lysates were cleared by a centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C. An equal amount of anti-FAK or Nck antibody was added directly to the cell extracts with an equal amount of proteins and incubated for 2 h or overnight at 4°C with rotation. After incubation, 30 μl of 50% slurry of protein A/G Sepharose beads (Upstate, Waltham, MA) was added to each sample, and incubation for an additional 2 h at 4°C with rotation was done. Immunoprecipitates were collected by a centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 3 min at 4°C and washed twice with ice-cold lysis buffer and twice with cold PBS. The immunoprecipitates were then eluted with 2× SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) sample buffer, and proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and probed via standard Western blotting.

Flow cytometry.

Flow cytometric measurements of integrin subtypes on cells were performed as described previously (23). To study the TGFβ1 effects on integrin expression levels in a time-dependent manner, one set of cells was replated on Fn and concomitantly untreated or treated with 5 ng/ml TGFβ1 for 0, 8, 12, or 20 h at the end of a total of 20 h incubation, before harvesting for the measurements. To study the effects of PKC inhibition on integrin expression, cells were replated on Fn in the absence or presence of 5 ng/ml TGFβ1 treatment without or with pretreatment of 12.5 μM GF-109203X. The raw data were analyzed by using a software program (WinMDI 2.7; Scripps Institute, San Diego, CA).

Wound-healing assay.

Normal cells or PKCδ wild type (WT)-expressing adenovirus (Ad-PKCδ)-infected cells in the serum-free replating media were seeded at a high density on 60-mm culture dishes precoated with Fn (10 μg/ml). Twelve hours later, wounds were made by scraping through the cell monolayer with a pipette tip. Cells were washed twice with RPMI 1640 and then treated with 5 ng/ml TGFβ1 in the absence or presence of PKC inhibitors (GF-109203X or rottlerin). After 36 h of incubation at 37°C, several images around wounds in each condition were taken.

Invasion assay.

A thick layer of matrigel (90 μl of 2.84 mg/ml per well of a 24-well transwell chamber) (BD Biosciences, Oxford, United Kingdom) was prepared on an upper chamber 6 h prior to cell replating. Routinely, the thickness of the layer was 500 mm. Normal or Ad-PKCδ WT-infected cells in serum-free RPMI containing 1% BSA were then replated on top of the matrigel. The lower chamber was filled with RPMI 1640 containing 10% fetal bovine serum or 1% BSA. After incubation for 72 h, cells inside of the upper chamber were mopped up. Cells beneath the membrane filter were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS and stained with crystal violet, and images were taken with a phase-contrast microscope.

Statistical analysis.

Paired Student's t tests were performed for comparisons of mean values to see if the difference is significant. P values of ≤0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

TGFβ1-, integrin-, and PKCδ-mediated spreading of gastric carcinoma cells.

We have interests in studying the roles of collaborative signaling of integrins with the TGFβ1 pathway in regulation of cellular behaviors. Specifically, we observed that TGFβ1 treatment of normally round-shape SNU16mAd gastric carcinoma cells on Fn caused spreading (Fig. 1A). In order to determine if this TGFβ1-mediated cell spreading requires integrin-mediated engagements with ECMs, cells were replated on PL with a concomitant 5 ng/ml TGFβ1 treatment for 20 h. However, TGFβ1 treatment did not cause spreading in cells replated on PL (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, TGFβ1-induced cell spreading appeared to depend on Smad pathways, since cells infected with adenovirus encoding for the Smad7, an inhibitory Smad, blocked the spreading, whereas cells infected with adenovirus for β-galactosidase (Ad-LacZ) maintained spread (Fig. 1B). These data suggest that both integrin engagement to ECM and Smad-dependent TGFβ1 signaling are required for spreading of the gastric carcinoma cells.

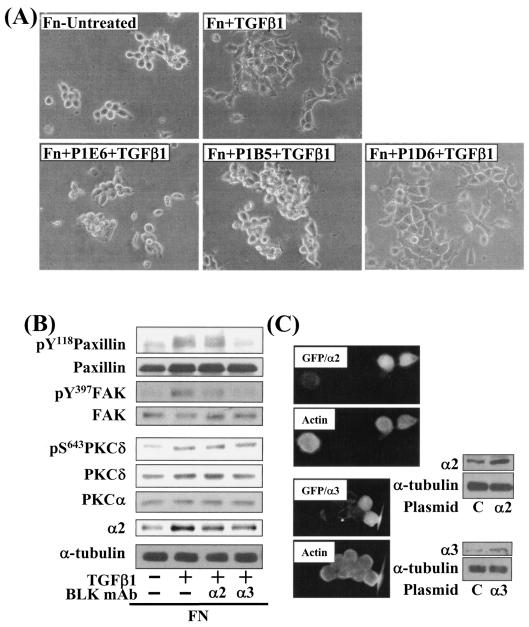

FIG. 1.

Integrin- and TGFβ1-mediated spreading of gastric carcinoma cells on fibronectin. (A) TGFβ1 and integrin signaling are required for spreading of gastric SNU16mAd carcinoma cells on fibronectin. The cells were trypsinized, collected, washed with RPMI 1640 containing 1% BSA, kept in suspension for 1 h at 37°C with rolling over, replated on Fn (10 μg/ml)- or PL (10 μg/ml)-precoated dishes, and incubated without or with 5 ng/ml TGFβ1 treatment for 20 h. Phase-contrast images were taken after the incubation. (B) Integrin- and TGFβ1-mediated cell spreading was blocked by Smad7 overexpression. Cells were infected with adenovirus encoding for β-galactosidase (LacZ) or Smad7, an inhibitory Smad. Twenty-four hours later, infected cells were manipulated, as explained above.

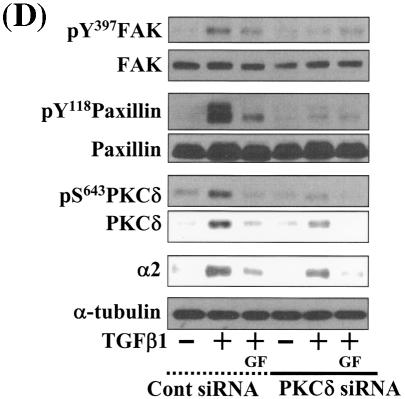

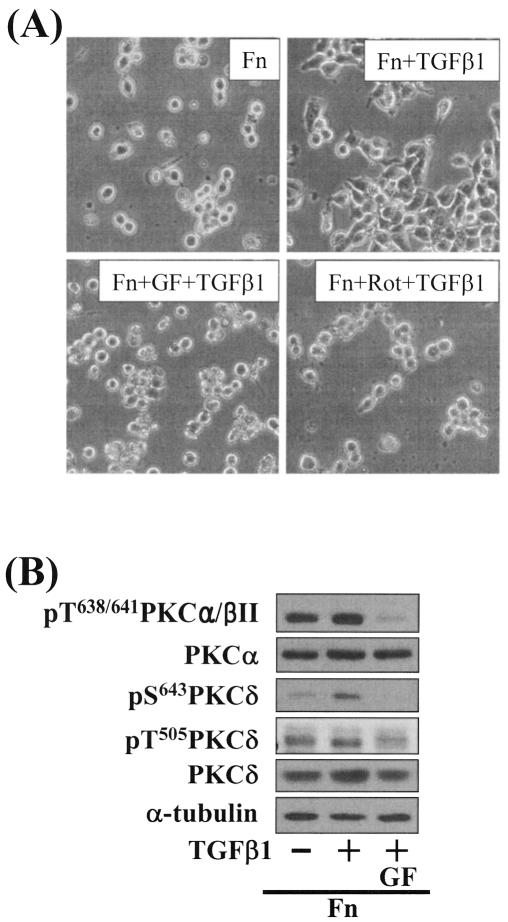

We next examined the effects of various pharmacological inhibitor treatments to determine which intracellular signaling molecules were responsible for the integrin- and TGFβ1-mediated spreading. In these tests, we found that the cell spreading was blocked by PKC inhibition using GF-109203X (a general inhibitor of PKCs) or rottlerin (Rot, an inhibitor of PKCδ) (Fig. 2A). These results indicate that SNU16mAd cell spreading depends on integrin, TGFβ1, and PKC signal transduction. To determine which PKC isoform(s) is involved in the cell spreading, we attempted to correlate phosphorylation of the isoforms with the spreading behaviors. Among the isoforms, Ser643 phosphorylation of PKCδ correlated closely with the spreading behaviors; cell spreading and Ser643 phosphorylation of PKCδ were minimal in the absence of TGFβ1 treatment on Fn but were induced by TGFβ1 in a GF treatment-dependent manner (Fig. 2B). However, PKCα/βII, PKCɛ, PKCζ/λ, and PKCθ appeared not to be involved in the spreading, since phosphorylation of PKCα/βII at Thr638/641 did not correlate with the spreading behaviors (Fig. 2B) and PKCɛ phosphorylation by using anti-phospho-pan PKC antibody and PKCζ/λ at Thr410/403 did not either (data not shown). PKCθ was not expressed in the cells (data not shown). Taken together, these observations suggest that integrin- and TGFβ1-mediated SNU16mAd cell spreading may involve PKCδ.

FIG. 2.

PKC pathway correlated with the integrin- and TGFβ1-mediated cell spreading. (A) Integrin- and TGFβ1-mediated cell spreading was abolished by PKC inhibition using GF-109203X (GF) and rottlerin (Rot). The cells were pretreated with GF-109203X (12.5 μM) or rottlerin (10 μM) 30 min prior to replating on Fn and TGFβ1 treatment for 20 h. (B) Phosphorylation of PKCδ serine 643 was increased by TGFβ1 treatment for 20 h and correlated with the integrin- and TGFβ1-mediated cell spreading. The cells were manipulated as in panel A. GF-109203X was treated as explained above. After the incubation for 20 h, cell lysates were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Data shown are representative of several independent experiments.

The cell spreading requires activation of focal adhesion molecules.

Because integrin-mediated cell adhesion and spreading activates focal adhesion (FA) molecules including FAK, paxillin, and c-Src, we analyzed phosphorylation of these molecules when TGFβ1 was used to treat cells on Fn for various periods (Fig. 3A). It was observed that the longer TGFβ1 was treated at the end of the total 20-h incubation, the higher the phosphorylations of FAK Tyr397, paxillin Tyr118, c-Src Tyr416, and PKCδ Ser643 (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, in addition to Ser643 phosphorylation, TGFβ1 treatment for longer than 4 h at the end of the 20-h incubation (e.g., 8 h) also enhanced PKCδ expression (Fig. 3A). In addition, blocking of PKCδ activity by pharmacological inhibitors (GF-109203X or rottlerin) decreased phosphorylation of the FA molecules (Fig. 3B). These data demonstrated that TGFβ1-, integrin-, and PKC-mediated cell spreading correlated with phosphorylation of the FA molecules. In order to verify the correlation of cell spreading with phosphorylation of the FA molecules, we examined the spreading of cells transiently cotransfected with the expression vectors of green fluorescent protein (GFP) and either dominant-negative or inactive forms of the FA molecules. Transfection of GFP alone did not block the TGFβ1-mediated spreading (see Fig. 6E). Cells transfected with FRNK (dominant negative), dominant-negative (Y31/118/157F) paxillin, or inactive (Y416F) c-Src did not spread by TGFβ1 treatment on Fn, whereas the surrounding untransfected cells did (Fig. 3C). Among GFP-positive cells, 90% (± 3.0%) of FRNK-transfected cells, 85% (± 4.5%) of Y31/118/157F paxillin-transfected cells, and 92% (± 3.2%) of Y416F c-Src-transfected cells showed round shapes [i.e., (the longest distance from one end to the other end of a cell)/(the shortest distance) < 2.0]. Previously it was shown that a complex formation of FAK with other adapter proteins including p130Cas was involved in cell spreading (5). In this study, formation of a protein complex including FAK, p130Cas, and Nck correlated with the cell spreading behaviors (Fig. 3D), supporting a previous suggestion that the complex might stabilize the active multiprotein complex at FAs (6). Therefore, these data suggest that the TGFβ1-, integrin-, and PKC-mediated cell spreading requires activation of the FA molecules and also involves formation of stable protein complexes at FAs.

The cell spreading requires new synthesis of PKCδ and integrins α2 and α3.

To determine whether the cell spreading depends on new protein synthesis, we examined the effects of cycloheximide treatment on the cell spreading. Inhibition of protein synthesis abolished phosphorylation of the FA molecules, expression and Ser643 phosphorylation of PKCδ (Fig. 4A, left), and cell spreading (Fig. 4A, right) by TGFβ1 treatment. In addition to increased expression of PKCδ by TGFβ1 (Fig. 3A and 4A), the cell spreading also correlated with increased expression of integrins α2 and α3, but not integrins α4 or α5, β1-conjugating integrins, α1(I) or α2(I) collagen I chains (a major integrin α2 binding partner), or α3 chain of laminin 5 (a major integrin α3 binding partner), in a cycloheximide treatment-dependent manner (Fig. 4B and data not shown). Flow cytometric analysis also revealed that TGFβ1 treatments with cells on Fn increased the expression of integrins α2 and α3 on the cell surface in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 4C); the expression was inhibited by PKC inhibition (Fig. 4D) or Smad7 overexpression (Fig. 4E). Taken together, these data suggest that the cell spreading mediated by TGFβ1, integrin, and PKC pathways involves Smad-dependent increases in PKCδ expression and Ser643 phosphorylation and expression of integrins α2 and α3.

Next, we investigated the significance of increased integrin expression with regard to the cell spreading. Cells were premixed with functional blocking integrin antibodies to preoccupy the integrins on the cell surface and then replated. Preincubation with anti-integrin α2 (clone P1E6) or α3 (clone P1B5), but not α5 (clone P1D6), antibody inhibited the cell spreading (Fig. 5A) and phosphorylation of the FA molecules (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, phosphorylation of the FA molecules was more effectively reduced by integrin α3 blockage than integrin α2 blockage, presumably indicating a specificity of signal transduction through integrin subtypes. However, the integrin blocking study did not reduce PKCδ expression or Ser643 phosphorylation, indicating that PKCδ acts upstream of the integrins (Fig. 5B). Meanwhile, the PKCα level was not changed by TGFβ1 treatment (Fig. 5B), indicating again that the TGFβ1-mediated effects did not involve PKCα (also as indicated in Fig. 2B and 6F). Therefore, we suggest that the cell spreading requires increased expression and activation of integrins α2 and α3, which function downstream of PKCδ. However, overexpression of human integrin α2 or α3 did not lead to cell spreading when TGFβ1 was not treated (Fig. 5C), indicating that additional TGFβ1-mediated signaling activity in addition to integrin expression is necessary for the cell spreading.

FIG. 5.

The TGFβ1 effects depend on expression and activation of integrins α2 or α3. The cells were pretreated with 10 μg/ml anti-integrin α2 (P1E6), α3 (P1B5), or α5 (P1D6) antibodies, 30 min prior to the replating on Fn and a concomitant TGFβ1 treatment for 20 h. After the incubation, cell images were taken, and lysates were prepared and used in immunoblots using antibodies against the indicated molecules. Data shown are representative of two isolated experiments. (A) Functional blocking anti-integrin α2 or α3, but not α5, antibodies abolished the cell spreading. (B) Functional blocking of the integrins inhibited phosphorylation of the FA molecules. (C) Cells were transiently cotransfected with a control plasmid (C) or pSF2-integrin α2 or α3 with pCDNA3-GFP. One day after the transfection, cells were replated onto Fn (10 μg/ml)-precoated cover glasses in the absence of TGFβ1 treatment. After incubation for 20 h at 37°C and 5% CO2, cells were processed for actin staining with phalloidin-conjugated TRITC. Another set of cells in 60-mm culture dishes were harvested for lysates prior to performing immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies. BLK mAb, functional blocking monoclonal antibody.

Regulation of PKCδ expression and activity affects the cell spreading.

Because PKCδ Ser643 phosphorylation correlated with the cell spreading during the inhibitor experiments, we investigated the significance of PKCδ in promoting cell spreading through regulation of PKCδ expression and phosphorylation. When cells were infected with various amounts of PKCδ WT-expressing adenovirus (Ad-PKCδ), Ser643 phosphorylation and the expression level of PKCδ dramatically increased (Fig. 6A). Thus, we could use the Ad-PKCδ to enable PKCδ overexpression and Ser643 phosphorylation. We next investigated whether PKCδ overexpression (and thus Ser643 overphosphorylation) could cause enhanced activation of the spreading-related FA molecules. PKCδ overexpression enhanced Ser643 phosphorylation of PKCδ, expression of integrin α2, and TGFβ1-mediated activation of the FA molecules, but GF-109203X or rottlerin treatment abolished the enhancements (Fig. 6B). Moreover, compared to cells infected with the control adenovirus (Ad-LacZ), spreading of PKCδ-overexpressing cells was minor in the absence of TGFβ1 and was much more enhanced by TGFβ treatment (Fig. 6C). Next, we tested if PKCδ down-regulation through its siRNA transfection affected the spreading. PKCδ suppression attenuated activation of the FA molecules and the integrin α2 expression level (Fig. 6D). PKCδ-suppressed cells did not spread, whereas normal neighbor cells spread (Fig. 6E). These data indicate that PKCδ indeed mediates TGFβ1-induced phosphorylation of the FA molecules, expression of the integrins, and cell spreading. Meanwhile, overexpression of PKCα using adenovirus with its cDNA did not cause additional enhancement of FA molecules phosphorylation, and dominant-negative PKCα could not abolish the TGFβ1-mediated spreading (Fig. 6F). These observations suggest that the cell spreading involves PKCδ, but not PKCα, signaling.

The more sufficiently the integrin-related signaling is activated, the better the cell spreading.

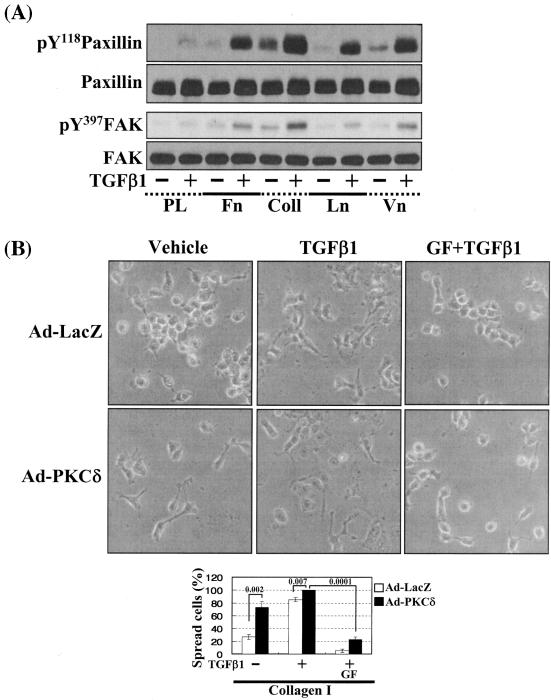

In this study, PKCδ overexpression alone did not cause significant activation of the FA molecules (Fig. 6B, left, lanes 1 and 4) and led to a minor spreading (Fig. 6C), although additional TGFβ1 treatment caused complete and accelerated spreading (Fig. 6C). Therefore, we hypothesized that a slight increase in either integrin signaling (Fig. 7A, B, and C) or TGFβ1 signaling (Fig. 7D and E) might facilitate the cell spreading. To test this possibility, we first examined the effects of cell replating on various ECM-precoated dishes on activation of the FA molecules and the cell spreading. Activation of the FA molecules was increased by TGFβ1 on the tested ECMs but not significantly on poly-l-lysine (Fig. 7A). Interestingly, basal (without TGFβ1 treatment) phosphorylation of the FA molecules was higher on collagen I than any of the other tested ECMs (Fig. 7A, lane 5). We thus examined the spreading behavior of cells overexpressing PKCδ on collagen I. PKCδ overexpression induced cell spreading (Fig. 7B) and consistently increased basal phosphorylation of the FA molecules and integrin α2 expression, compared to those in Ad-LacZ-infected cells (Fig. 7C, lanes 1 and 4) even without TGFβ1 treatment. It appeared that higher basal integrin signaling activity could cause the cell spreading even without TGFβ1 treatment. Furthermore, compared to the Ad-LacZ-infected cells, quantitatively (i.e., higher spreading rate) and qualitatively (i.e., wider spreading) enhanced cell spreading by TGFβ1 treatment was observed on collagen I (Fig. 7B). Interestingly, being consistent with the quantitatively and qualitatively enhanced spreading, the TGFβ1-increased phosphorylation of the FA molecules and expression level of integrin α2 were observed in PKCδ-overexpressing cells (Fig. 7B and C, lanes 2 and 5). In addition, this spreading was blocked by PKC inhibition (Fig. 7B), as decreased phosphorylation of the FA molecules and suppressed expression of integrins by PKC inhibition (Fig. 7C). We next investigated if an increased TGFβ1 signaling presumably through Smad2 or Smad3 overexpression would affect the spreading. The TGFβ1 effects were investigated using cells infected with adenovirus encoding for either β-galactosidase or FLAG-tagged Smad2 or Smad3 that still require TGFβ1 treatment for their activation (30). Interestingly, overexpression of Smad3, but not Smad2, enhanced the TGFβ1-mediated activation of the FA molecules, expression and Ser643 phosphorylation of PKCδ, expression of integrin α2 (Fig. 7D), and cell spreading (Fig. 7E) in a PKC activity-dependent manner. Therefore, these observations suggest the significance of the Smad3-dependent TGFβ1 signaling in expression and activation of PKCδ and integrins, activation of the FA molecules, and the spreading.

FIG. 7.

Cells under more efficient integrin-related signaling activities lead to enhanced cell spreading. (A) Phosphorylation of the FA molecules in cells replated on poly-l-lysine or diverse ECM proteins. Cells were replated on culture dishes precoated with various ECMs (10 μg/ml) (Coll, collagen I; Ln, laminin I; Vn, vitronectin), in the absence or presence of TGFβ1 treatment for 20 h. Cell lysates were then prepared and used for Western blots with antibodies against the indicated molecules. Data shown represent three independent experiments. (B) Spreading of PKCδ WT-overexpressing cells on collagen I even without TGFβ1 treatment. Twenty-four hours after infection with Ad-LacZ or Ad-PKCδ, cells were manipulated to be replated on collagen I-precoated dishes. Certain cells were pretreated with GF-109203X (GF), as described above. Twenty hours after the replating, images were taken. The rate of spread cells in percent graphed was determined as explained for Fig. 6C. A P value of ≤0.05 was considered significant. (C) Cells infected with Ad-PKCδ enhanced basal and TGFβ1-mediated expression of integrin α2 and phosphorylation of the FA molecules on collagen I. Cell manipulation and cell lysate preparation were performed, as explained above. Data shown were representative of three independent experiments. (D, E) Smad3 overexpression enhanced TGFβ1-mediated phosphorylation of the FA molecules (D) and cell spreading (E). Cells were infected with adenovirus encoding for either control (Ad-LacZ), Flag-Smad2 (Ad-Smad2), or Flag-Smad3 (Ad-Smad3). Twenty-four hours later, infected cells were replated on Fn. In certain cases, GF-109203X or Rottlerin (Rot) pretreatment was done as explained above. After 20 h of incubation at 37°C, cell lysates were prepared for Western blots, or cell images were taken. Quantitative determinations of the spread cells were done as explained for Fig. 6C. A P value of ≤0.05 was considered significant. Data shown were representative of three isolated experiments.

The cell spreading-related signaling network also increased migration and invasion through matrigel.

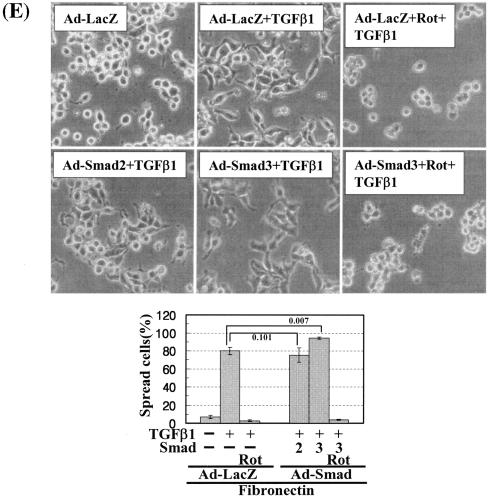

Cell spreading may enable a cell to respond to extracellular cues during migration and invasion. To investigate whether cell spreading and spreading-related biochemical activities correlate with cell motility and invasiveness, we performed wound-healing and invasion assays. Compared with the untreated cells, wound healing was significant in the TGFβ1-treated cells on Fn, in a PKCδ activity-dependent manner. This increased wound healing was not due to alteration in cell proliferation or apoptosis (data not shown) but presumably was due to migration of cells towards the wounds. When cells overexpress PKCδ, TGFβ1-induced wound healing was further enhanced, but slightly higher than that of TGFβ1-treated normal control cells (Fig. 8A). This increased motility by TGFβ1 treatment and PKCδ activity in cells on Fn indicate that the motility appears to correlate with the spreading behaviors. In addition, the TGFβ1-treated cells showed increased invasion through matrigel dependent on PKC activity, compared with the untreated cells. Furthermore, cells overexpressing PKCδ also showed more enhanced invasion, also depending on PKC activity (Fig. 8B). Therefore, the signaling network required for the cell spreading was also involved in the motility and invasion, indicating that the motility and invasion correlate with the spreading behaviors.

FIG.8.

Wound healing and invasion also depend on TGFβ1, PKCδ, and integrins. (A) TGFβ1- and PKCδ activity-mediated wound healing on Fn. Prior to making wounds, normal or Ad-PKCδ-infected cells were replated onto Fn-precoated six-well culture plates. Twelve hours later, wounds (marked as dotted lines) were created by scraping through the monolayer. Cells were then incubated in the absence or presence of TGFβ1 treatment without or with PKC inhibition (GF-109203X [GF] or rottlerin [Rot]) for 36 h at 37°C, prior to taking images. Note that TGFβ1-mediated healing in PKCδ-overexpressing cells is slightly enhanced, compared to that in normal control cells (i.e., compare healing around the vertical arrowheads). (B) TGFβ1- and PKCδ activity-mediated invasion of the cells through matrigel. Normal or Ad-PKCδ-infected cells in RPMI 1640 containing 1% BSA were replated onto matrigel, prepared as explained in Materials and Methods, and concomitantly treated with or without 5 ng/ml TGFβ1. Certain cells were pretreated with 12.5 μM GF-109203X, 30 min prior to the TGFβ1 treatment. Then the upper chambers were placed into 24-well culture dishes containing 0.6 ml of RPMI 1640 with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) or with 1% BSA. After incubation at 37°C for 72 h, invasive cells were fixed and stained with crystal violet, and then images were taken, as explained in Materials and Methods. The images shown are representative of three isolated experiments. Stained cells in three independent images for each condition were counted for the graphic presentation (mean ± standard deviation).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we explored the signaling mechanisms underlying the cell spreading process alone, separated from adhesion, using gastric carcinoma SNU16mAd cells. These cells are normally round but spread polygonally by TGFβ1 treatment in the absence or presence of serum. The TGFβ1-mediated spreading depends on integrin interaction with ECMs and signal transduction involving PKCδ. We found that this spreading of gastric carcinoma cells involved induction and Ser643 phosphorylation of PKCδ, expression and activation of integrins (α2 and α3), and activation of the FA molecules. Furthermore, the spreading-related signaling activities were involved in the wound healing and invasion. Observations from this study suggest that the signaling network involving TGFβ1, PKCδ, and integrins underlies spreading and migration and invasion of an adherent gastric carcinoma variant cell line, SNU16mAd.

SNU16mAd cells used in this study were obtained from subsequent cultures to collect adherent cells among mostly anchorage-independent SNU16α5 cells (18). A long period was required for adherence when the cells were replated on Fn-precoated dishes, and the cell shape appeared round even when fully adhered to the substrate. When cells replated on Fn were treated with TGFβ1 for a long period (e.g., 20 h), the cells became spread. Therefore, this cell line is a good model system to study cell spreading events by specific stimuli, separate from the adhesion process. This may be an important distinction, as many normally adherent cell types spread gradually and spontaneously after being replated.

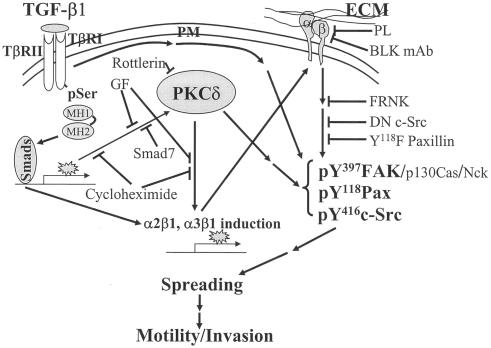

So far, signaling networks consisting of integrins, TGFβ1, and PKC (especially PKCδ) have not been thoroughly investigated, especially for cell spreading and invasiveness, although a previous report showed that general PKC activity preceded integrin-mediated cell adhesion on fibronectin (41). In this study, we demonstrated a complicated signaling network underlying a specific cellular behavior (i.e., cell spreading). Smad-dependent TGFβ1 signaling led to increased expression and Ser643 phosphorylation of PKCδ, which correlated with induction and activation of integrins, activation and stable complex formation of the FA molecules, and cell spreading. Although the effects of TGFβ1 and integrins on metastasis have been previously reported (11, 20, 42), the positive involvement of PKCδ in the migration and invasion has not been fully elucidated. The observations from this study suggest that the spreading correlates with increased motility and invasion, since TGFβ1-mediated wound healing and invasion also depended on PKCδ expression and activation and integrin-related signaling activation. The TGFβ1-mediated wound healing on Fn in PKCδ-overexpressing cells could be slightly enhanced, compared to that of TGFβ1-treated normal control cells, probably because this cell line is much less motile in the absence of serum. This observation was consistent with a slight (but statistically significant) increase in quantitative spreading rate that was accompanied by a qualitatively wider spread (Fig. 6C).

In addition to the PKC inhibitor studies, overexpression by PKCδ adenovirus and down-regulation by PKCδ siRNA showed the significance of PKCδ in the cell spreading, wound healing, and invasion. Among other PKC isoforms, PKCα/βII, PKCζ/λ, and -ɛ appeared not to be involved in the system because their phosphorylation status did not correlate well with the cell spreading patterns under the experimental conditions, and PKCθ was not expressed in our cells. In addition, PKCα and PKCθ overexpression did not result in spreading on fibronectin. More conclusively, cells infected with adenovirus with dominant-negative PKCα could still spread on fibronectin upon TGFβ1 treatment. Therefore, it is likely that the TGFβ1-mediated spreading involves PKCδ at least, but not PKCα and -θ, and that PKCδ is a mediator for TGFβ1 to integrin signaling pathways and acts upstream of integrins and the FA molecules (Fig. 9).

FIG. 9.

Schematic working model of the TGFβ1-, PKCδ-, and integrin-mediated cellular functions in gastric carcinoma cells. TGFβ1 treatments of cells on ECMs lead to increased expression and phosphorylation of PKCδ, cell surface levels of integrins α2 or α3, and activation of the focal adhesion molecules. This signaling network results in spreading, migration, and invasion of the SNU16mAd gastric carcinoma cell variant. In addition to a linear connection, presumably additional bypassing connections may contribute to the TGFβ1 effects.

On the other hand, the signaling network of TGFβ1, PKCδ, integrins, and integrin-related signaling molecules appeared to be complicated rather than in order. First, overexpression of PKCδ in the absence of TGFβ1 treatment did not result in a complete spreading, although TGFβ1 treatment facilitated the spreading of PKCδ-overexpressing cells, compared to control cells. Second, overexpression of integrins α2 or α3 did not cause spreading in the absence of TGFβ1. These observations indicate that just a linear connection from the Smad-dependent TGFβ1 pathway to integrin induction and activation via PKCδ induction and phosphorylation is not sufficient for the spreading and that probably different TGFβ1-mediated biochemical actions function to activate and/or assemble downstream effectors (complexes), such as the FA molecules (Fig. 9). Recently there has been diverse evidence that TGFβ1 activates diverse intracellular signaling molecules that are also regulated by integrin-mediated cell adhesion (7, 28).

In this study, incubation of the cells with TGFβ1 for 20 h in the absence of serum increased Ser643 phosphorylation as well as expression of PKCδ. However, it is currently a controversial assumption that Ser643 phosphorylation affects kinase activity of PKCδ. One previous study reported that a Ser643 to alanine mutation had no effect on the kinase activity of PKCδ (39), whereas another showed that Ser643 of PKCδ is an important autophosphorylation site for its enzymatic activity (26). Furthermore, we observed that TGFβ1 treatment for only 6 or ∼8 h caused Ser643 phosphorylation of PKCδ but not induction of PKCδ and integrins, phosphorylation of the FA molecules, and cell spreading (data not shown). We also found that 15-h TGFβ1-free incubation even after 5-h TGFβ1 treatment caused the TGFβ1 effects (data not shown), indicating that the TGFβ1 treatment alone for such a short period (e.g., for 6 or ∼8 h) was not enough to cause the TGF effects. Therefore, it is likely that the Ser643 phosphorylation of PKCδ is not critical for the cell spreading, although TGFβ1 treatment for 20 h resulted in the phosphorylation correlated with the spreading. Although the significance of the Ser643 phosphorylation for PKCδ activity is controversial, pharmacological inhibition of PKCδ activity abolished the spreading in this study. Therefore, it appears that the cell spreading importantly involves induction and activation of PKCδ and integrins and activation of integrin-related signaling.

There have been evidences for effects of TGFβ1 on integrins and/or ECMs, and vice versa (36). Although the increased integrins α2 or α3 bind collagen I or laminin 5, respectively (33), neither collagen I (α2 and α1 chains) nor laminin 5 (α3 chain) expression levels of the SNU16mAd cells were changed by TGFβ1 treatment upon immunoblotting with commercial antibodies against them (Fig. 4B). Although the TGFβ1 effect was shown in all ECMs we tested, we performed most experiments on fibronectin, just because the TGFβ1-mediated effect was more obvious with no basal signaling activity on fibronectin, compared to on collagen I or laminin 1, and because these integrins α2 or α3 also bind to fibronectin (32, 40). We cannot rule out the possibility that collagen I and/or laminin I might support the integrins α2 or α3 enhanced by TGFβ1, since the cells still expressed them, although their expressions were not enhanced by the TGFβ1 treatment. We did not see TGFβ1-mediated spreading on fibronectin when integrin α5 (a typical Fn receptor) was ectopically overexpressed (data not shown), being consistent with no change in integrin α5 by TGFβ1. Furthermore, the cell spreading was abolished by functional blocking of integrins α2 or α3, but not α5, using their inhibitory monoclonal antibodies. Therefore, we can conclude that the TGFβ1-, PKCδ-, and integrin-mediated spreading involves increases in specific integrin α2 or α3 expression, presumably, but not increases in ECM production. On the other hand, it may be likely that integrins α2 or α3 have specific and exclusive linkage(s) to the FA molecules, although both were shown to be involved in this spreading system. We observed that integrin α3 expression increased suddenly at a specific time point presumably after signal accumulations by TGFβ1 treatment surpassed a threshold (Fig. 4C). However, integrin α2 expression is increased gradually in a time-dependent manner after TGFβ1 treatment. This narrower window of TGFβ1-mediated integrin α3 increase rendered the changes in the integrin α3 expression level much more difficult to detect. Furthermore, phosphorylation of the pY118Paxillin was abrogated by integrin α3 blocking, using anti-integrin α3 monoclonal antibody, but not significantly by integrin α2 blocking, whereas pY397FAK was abrogated by both inhibitory antibodies. These observations may suggest a specific role(s) of each integrin subtype for the TGFβ1-mediated FA molecule activation.

We showed in Fig. 7A that basal (without TGFβ1 treatment) activation of the FA molecules was more prominent on collagen I and was much more enhanced by TGFβ1 treatment, compared to on Fn. This higher basal activation of the FA molecules correlated with cell spreading on collagen I with PKCδ overexpression alone even in the absence of TGFβ1 treatment, and TGFβ1-mediated activity might correlate with a wider spreading (Fig. 7B). Therefore, depending on the ECM, spreading of SNU16mAd cells may require different signaling activities for complete and sufficient spreading. On collagen I, integrin and PKCδ signal pathways were enough for the spreading, and additional TGFβ1 signaling activity correlated with (qualitatively) wider spreading. Meanwhile, the spreading on Fn appears to additionally require TGFβ1 signaling probably to support the PKCδ and integrin signaling, and the combined signaling output through complicated signal connections may lead to complete cell spreading (Fig. 9).

All together, in this study, the positive roles of PKCδ in the TGFβ1 and integrin effects on cellular functions were clearly suggested by the observations that PKCδ is required to mediate TGFβ1 treatment for integrin expression and activation, leading to spreading, migration, and invasion of human gastric carcinoma SNU16mAd cells.

Acknowledgments

We deeply thank Jang-Soo Chun (Gwangju Institute of Science and Technology, Gwangju, Korea) for adenovirus encoding for PKCδ or PKCα and Rudy L. Juliano (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC) for expression vectors such as pBS-FRNK and etc, respectively.

This work was supported by a Korea Research Foundation Grant (KRF-2004-015-C00445) to J. W. Lee.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akhurst, R. J., and R. Derynck. 2001. TGF-β signaling in cancer—a double-edged sword. Trends Cell Biol. 11:S44-S51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alahari, S. K., P. J. Reddig, and R. L. Juliano. 2002. Biological aspects of signal transduction by cell adhesion receptors. Int. Rev. Cytol. 220:145-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arthur, W. T., and K. Burridge. 2001. RhoA inactivation by p190RhoGAP regulates cell spreading and migration by promoting membrane protrusion and polarity. Mol. Biol. Cell 12:2711-2720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhowmick, N. A., R. Zent, M. Ghiassi, M. McDonnell, and H. L. Moses. 2001. Integrin β1 signaling is necessary for transforming growth factor-β activation of p38MAPK and epithelial plasticity. J. Biol. Chem. 276:46707-46713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruce-Staskal, P. J., and A. H. Bouton. 2001. PKC-dependent activation of FAK and Src induces tyrosine phosphorylation of Cas and formation of Cas-Crk complexes. Exp. Cell Res. 264:296-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buday, L., L. Wunderlich, and P. Tamas. 2002. The Nck family of adapter proteins: regulators of actin cytoskeleton. Cell. Signal. 14:723-731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Derynck, R., and Y. E. Zhang. 2003. Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways in TGF-β family signalling. Nature 425:577-584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eliceiri, B. P. 2001. Integrin and growth factor receptor crosstalk. Circ. Res. 89:1104-1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engel, M. E., M. A. McDonnell, B. K. Law, and H. L. Moses. 1999. Interdependent SMAD and JNK signaling in transforming growth factor-β-mediated transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 274:37413-37420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gschwendt, M., H. J. Muller, K. Kielbassa, R. Zang, W. Kittstein, G. Rincke, and F. Marks. 1994. Rottlerin, a novel protein kinase inhibitor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 199:93-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guo, W., and F. G. Giancotti. 2004. Integrin signalling during tumour progression. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5:816-826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hartsough, M. T., and K. M. Mulder. 1995. Transforming growth factor β activation of p44MAPK in proliferating cultures of epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 270:7117-7124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayashida, T., and H. W. Schnaper. 2004. High ambient glucose enhances sensitivity to TGF-β1 via extracellular signal-regulated kinase and protein kinase Cδ activities in human mesangial cells. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 15:2032-2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hocevar, B. A., T. L. Brown, and P. H. Howe. 1999. TGF-β induces fibronectin synthesis through a c-Jun N-terminal kinase-dependent, Smad4-independent pathway. EMBO J. 18:1345-1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hynes, R. O. 2002. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell 110:673-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ignotz, R. A., and J. Massague. 1987. Cell adhesion protein receptors as targets for transforming growth factor-β action. Cell 51:189-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Juliano, R. L. 2002. Signal transduction by cell adhesion receptors and the cytoskeleton: functions of integrins, cadherins, selectins, and immunoglobulin-superfamily members. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 42:283-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim, H. P., M. S. Lee, J. Yu, J. A. Park, H. S. Jong, T. Y. Kim, J. W. Lee, and Y. J. Bang. 2004. TGF-β1 (transforming growth factor-β1)-mediated adhesion of gastric carcinoma cells involves a decrease in Ras/ERKs (extracellular-signal-regulated kinases) cascade activity dependent on c-Src activity. Biochem. J. 379:141-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18a.Kim, H. P., T. Y. Kim, M. S Lee, H. S Jong, T. Y. Kim, J. W. Lee, and Y. J. Bang. 2005. TGF-β1-mediated activations of c-Src and Rac1 modulate levels of cyclins and p27Kip1 CDK inhibitor in hepatoma cells replated on fibronectin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1743:151-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim, M. G., G. Lee, S.-K. Lee, M. Lolkema, J. Yim, S. H. Hong, and R. H. Schwartz. 2000. Epithelial cell-specific laminin 5 is required for survival of early thymocytes. J. Immunol. 165:192-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koivunen, J., V. Aaltonen, S. Koskela, P. Lehenkari, M. Laato, and J. Peltonen. 2004. Protein kinase C α/β inhibitor Gö6976 promotes formation of cell junctions and inhibits invasion of urinary bladder carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 64:5693-5701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar, N. M., S. L. Sigurdson, D. Sheppard, and J. S. Lwebuga-Mukasa. 1995. Differential modulation of integrin receptors and extracellular matrix laminin by transforming growth factor-β1 in rat alveolar epithelial cells. Exp. Cell Res. 221:385-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee, J. W., and R. Juliano. 2004. Mitogenic signal transduction by integrin- and growth factor receptor-mediated pathways. Mol. Cells 17:188-202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee, J. W., and R. L. Juliano. 2000. α5β1 integrin protects intestinal epithelial cells from apoptosis through a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and protein kinase B-dependent pathway. Mol. Biol. Cell 11:1973-1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee, J. W., and R. L. Juliano. 2002. The α5β1 integrin selectively enhances epidermal growth factor signaling to the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/Akt pathway in intestinal epithelial cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1542:23-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee, M. S., S. G. Ko, H. P. Kim, Y. B. Kim, S. Y. Lee, S. G. Kim, H. S. Jong, T. Y. Kim, J. W. Lee, and Y. J. Bang. 2004. Smad2 mediates Erk1/2 activation by TGF-β1 in suspended, but not in adherent, gastric carcinoma cells. Int. J. Oncol. 24:1229-1234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li, W., J. Zhang, D. P. Bottaro, and J. H. Pierce. 1997. Identification of serine 643 of protein kinase C-δ as an important autophosphorylation site for its enzymatic activity. J. Biol. Chem. 272:24550-24555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mainiero, F., A. Gismondi, R. Strippoli, J. Jacobelli, A. Soriani, S. Morrone, and A. Santoni. 2000. Integrin-mediated regulation of cytokine and chemokine production by human natural killer cells. Eur. Cytokine Netw. 11:493-494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Massague, J. 2000. How cells read TGF-β signals. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 1:169-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Massague, J. 1998. TGF-β signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67:753-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakao, A., T. Imamura, S. Souchelnytskyi, M. Kawabata, A. Ishisaki, E. Oeda, K. Tamaki, J. Hanai, C. H. Heldin, K. Miyazono, and P. ten Dijke. 1997. TGF-β receptor-mediated signalling through Smad2, Smad3 and Smad4. EMBO J. 16:5353-5362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oktay, M., K. K. Wary, M. Dans, R. B. Birge, and F. G. Giancotti. 1999. Integrin-mediated activation of focal adhesion kinase is required for signaling to Jun NH2-terminal kinase and progression through the G1 phase of the cell cycle. J. Cell Biol. 145:1461-1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Plow, E. F., T. A. Haas, L. Zhang, J. Loftus, and J. W. Smith. 2000. Ligand binding to integrins. J. Biol. Chem. 275:21785-21788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reddy, K. V., and S. S. Mangale. 2003. Integrin receptors: the dynamic modulators of endometrial function. Tissue Cell 35:260-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodriguez-Barbero, A., J. Obreo, L. Yuste, J. C. Montero, A. Rodriguez-Pena, A. Pandiella, C. Bernabeu, and J. M. Lopez-Novoa. 2002. Transforming growth factor-β1 induces collagen synthesis and accumulation via p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway in cultured L6E9 myoblasts. FEBS Lett. 513:282-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Runyan, C. E., H. W. Schnaper, and A. C. Poncelet. 2003. Smad3 and PKCδ mediate TGF-β1-induced collagen I expression in human mesangial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 285:F413-F422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schneiderbauer, M. M., C. M. Dutton, and S. P. Scully. 2004. Signaling “cross-talk” between TGF-β1 and ECM signals in chondrocytic cells. Cell Signal. 16:1133-1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shirai, Y., and N. Saito. 2002. Activation mechanisms of protein kinase C: maturation, catalytic activation, and targeting. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 132:663-668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Short, S. M., J. L. Boyer, and R. L. Juliano. 2000. Integrins regulate the linkage between upstream and downstream events in G protein-coupled receptor signaling to mitogen-activated protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 275:12970-12977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stempka, L., M. Schnolzer, S. Radke, G. Rincke, F. Marks, and M. Gschwendt. 1999. Requirements of protein kinase cδ for catalytic function. Role of glutamic acid 500 and autophosphorylation on serine 643. J. Biol. Chem. 274:8886-8892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van der Flier, A., and A. Sonnenberg. 2001. Function and interactions of integrins. Cell Tissue Res. 305:285-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vuori, K., and E. Ruoslahti. 1993. Activation of protein kinase C precedes α5β1 integrin-mediated cell spreading on fibronectin. J. Biol. Chem. 268:21459-21462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang, H., W. Fu, J. H. Im, Z. Zhou, S. A. Santoro, V. Iyer, C. M. DiPersio, Q. C. Yu, V. Quaranta, A. Al-Mehdi, and R. J. Muschel. 2004. Tumor cell α3β1 integrin and vascular laminin-5 mediate pulmonary arrest and metastasis. J. Cell Biol. 164:935-941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamada, K. M., and S. Even-Ram. 2002. Integrin regulation of growth factor receptors. Nat. Cell Biol. 4:E75-E76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang, C., and M. G. Kazanietz. 2003. Divergence and complexities in DAG signaling: looking beyond PKC. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 24:602-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu, L., M. C. Hebert, and Y. E. Zhang. 2002. TGF-β receptor-activated p38 MAP kinase mediates Smad-independent TGF-β responses. EMBO J. 21:3749-3759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang, L., M. P. Keane, L. X. Zhu, S. Sharma, E. Rozengurt, R. M. Strieter, S. M. Dubinett, and M. Huang. 2004. Interleukin-7 and transforming growth factor-β play counter-regulatory roles in protein kinase C-δ-dependent control of fibroblast collagen synthesis in pulmonary fibrosis. J. Biol. Chem. 279:28315-28319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]