Abstract

Regulation of cytoplasmic dynein and microtubule dynamics is crucial for both mitotic cell division and neuronal migration. NDEL1 was identified as a protein interacting with LIS1, the protein product of a gene mutated in the lissencephaly. To elucidate NDEL1 function in vivo, we generated null and hypomorphic alleles of Ndel1 in mice by targeted gene disruption. Ndel1−/− mice were embryonic lethal at the peri-implantation stage like null mutants of Lis1 and cytoplasmic dynein heavy chain. In addition, Ndel1−/− blastocysts failed to grow in culture and exhibited a cell proliferation defect in inner cell mass. Although Ndel1+/− mice displayed no obvious phenotypes, further reduction of NDEL1 by making null/hypomorph compound heterozygotes (Ndel1cko/−) resulted in histological defects consistent with mild neuronal migration defects. Double Lis1cko/+-Ndel1+/− mice or Lis1+/−-Ndel1+/− mice displayed more severe neuronal migration defects than Lis1cko/+-Ndel1+/+ mice or Lis1+/−-Ndel1+/+ mice, respectively. We demonstrated distinct abnormalities in microtubule organization and similar defects in the distribution of β-COP-positive vesicles (to assess dynein function) between Ndel1 or Lis1-null MEFs, as well as similar neuronal migration defects in Ndel1- or Lis1-null granule cells. Rescue of these defects in mouse embryonic fibroblasts and granule cells by overexpressing LIS1, NDEL1, or NDE1 suggest that NDEL1, LIS1, and NDE1 act in a common pathway to regulate dynein but each has distinct roles in the regulation of microtubule organization and neuronal migration.

The mammalian brain is assembled through a series of far-ranging migrations that result in the segregation of neurons with similar properties into discrete layers (32). Important clues for molecular mechanisms of neuronal migration were provided from the analysis of brain malformations in humans exhibiting neuronal migration defects (13). Lissencephaly is a cerebral cortical malformation characterized by a smooth cerebral surface and a disorganized cortex (3, 4) due to incomplete neuronal migration. In lissencephaly patients, mutation of two genes, LIS1 or DCX, account for the majority of classical lissencephaly (LIS) (31). LIS1 encodes a protein carrying seven WD repeats (33) that was first identified as a noncatalytic subunit of platelet activating factor-acetylhydrolase (Pafah1b1) (15). Consistent with an important role for this protein in neuronal migration, mice with decreased Lis1 exhibit disorganization of cortical layers, hippocampus, and olfactory bulb in a dose-dependent fashion and are a good model for the human disorder (10, 17). Lis1-null mice exhibit peri-implantation lethality and, in Lis1-null blastocysts, the inner cell mass degenerated soon after differentiation, suggesting that Lis1 has an essential role in cell division (17).

LIS1 protein is highly conserved from human to Aspergillus (26, 27). The LIS1 homologue in Aspergillus, nudF (44), was originally identified as a gene mutated in a series of hyphal mutants exhibiting defects in nuclear migration. In addition, nudF displayed strong genetic interaction with nudA and nudG, which encode a cytoplasmic dynein heavy chain (CDHC) and a dynein intermediate chain, respectively (47). CDHC is a microtubule-based minus-end-directed motor protein that plays an important role in mitotic cell division, neuronal migration, and organelle transport (12, 16, 45, 46). Genetic analysis of Lis1 function in Drosophila oogenesis has shown that Lis1, similar to cytoplasmic dynein (Dhc64C), is essential for germ line cell division and nuclear positioning, supporting the idea that Lis1 functions with the dynein complex and the microtubule cytoskeleton (20, 21, 40). NudE is an Aspergillus gene that genetically interacts with the nudF/Lis1 pathway (6). We and others previously reported that there are two mammalian homologues of Aspergillus NudE, NDE1 (8) and NDEL1 (29, 35, 36); the latter, a homologue of NudE from Aspergillus nidulans, is a LIS1 binding protein that participates with LIS1 in the regulation of CDHC function via phosphorylation by CDK5/p35 (8, 29, 35, 36), a complex known to be essential for neuronal migration (1, 7, 11, 13, 18, 30). We have also shown that phosphorylation of NDEL1 is protected by the serine-threonine binding protein 14-3-3ɛ and that 14-3-3ɛ is required for normal neuronal migration (42), providing further support that the phosphorylation of NDEL1 is required for proper neuronal migration. NDE1 has a similar function in cells but is expressed later in development than NDEL1. Recently, Nde1-null mice have been produced (9). These mice are viable and display microcephaly. They display defects in neurogenesis that result from reduced progenitor cell division and progenitor cell fate, as well as modest defects in neuronal migration. To date, targeted mutants of Ndel1 have not been generated, and the in vitro phenotype of null mutants of Ndel1 is unknown.

To understand the role of NDEL1 in vivo and to determine whether it plays a role in corticogenesis and cell division, we generated Ndel1-disrupted mice. We found that, similar to Lis1, Ndel1 mutant mice display a dosage-dependent neuronal migration phenotype, and complete loss of Ndel1 resulted in perinatal lethality. Examination of in vivo and in vitro phenotypes suggests that NDEL1, LIS1, and NDE1 act in a common pathway to regulate dynein, but each has distinct roles in the regulation of microtubule organization and neuronal migration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation and analysis of Ndel1 KO mice.

To understand the function of Ndel1 in vivo, we generated a first conditional knockout (KO) mouse to inactivate Ndel1 by Cre-mediated recombination. We assembled a targeting construct in which a PGK-neo gene flanked by a loxP site and an additional loxP site were inserted into intron III and intron II, respectively. The linearized targeting construct was introduced into TC1 embryonic stem (ES) cells (2) from a 129S6 background by electroporation. The targeted ES clones were screened by Southern blot and injected into blastocysts to create chimeric mice. Highly agouti chimeric males were mated to wild-type females to give rise to heterozygotes for the conditional allele [Ndel1cko(III)/+], which was identified by Southern blot analysis and PCR. These heterozygous mice were mated with EIIa-Cre germ line deleter transgenic mice (19). Offspring from the matings between an Ndel1cko(III)/+ line and an EIIa-Cre transgenic line were genotyped by Southern blot analysis and PCR. Southern blot analysis and PCR examination indicated efficient deletion of the fragment carrying exon III by CRE mediated recombination in vivo. Ndel1cko(III)/cko(III) mice exhibited embryonic lethality similar with Ndel1ko(III)/ko(III) mice, suggesting that the presence of the neo gene severely affects expression of Ndel1. It was not possible to remove neo gene by itself. For the second conditional KO strategy, we inserted a PGK-neo gene flanked by a loxP site and an additional loxP site into intron IV and intron III, respectively. Highly agouti chimeric males were mated to wild-type females to give rise to heterozygotes for the second conditional allele [Ndel1cko(IV)/+]. In contrast to the first line of conditional KO, homozygotes of the second conditional KO [Ndel1cko(IV)/cko(IV)] line was completely viable and fertile. CRE-mediated deletion of the second conditional KO mouse line was also confirmed by PCR with primers located flanking the site of the deleted region. We used Ndel1ko(III)/+ as Ndel1+/−, whereas Ndel1cko(IV)/+ was used as Ndel1cko/+ in this experiment. Expression of NDEL1 was examined by Western blotting with the C-6 NDEL1 specific antibody (36) and Northern blotting with a full-length Ndel1 cDNA fragment. All experiments with mouse models were performed based on the animal experiment guidelines of our universities.

BrdU birth dating study.

For bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) experiments, pregnant dams (embryonic day 15.5 [E15.5]) were injected with BrdU (50 μg/g, intraperitoneally). Subsequently, the distribution of BrdU-positive cells was determined at P0. The incorporation of BrdU in cells was detected with a mouse anti-BrdU monoclonal primary antibody (Roche), followed by an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibody (Boehringer Mannheim). We analyzed three independent mice for each genotype.

Histological examination and immunohistochemistry.

After perfusion with Bouin's or 4% paraformaldehyde fixative, tissues from wild-type and various mutant mice were subsequently embedded in paraffin and sectioned at 5-μm thickness. After deparaffination, endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by incubating the sections in 1.5% peroxide in methanol for 20 min. The sections were then boiled in 0.01 mol of citrate buffer (pH 6.0)/liter for 20 min and cooled slowly. Before staining, the sections were blocked with rodent block (LabVision) for 60 min. The sections were washed in phosphate-buffered saline and incubated with each antibody. Primary cultures of cerebellar granule cells were generated from 5-day-old C57BL/6 pups as described previously (36). Cells were plated at a density of 2.5 × 105 cells/cm2 and maintained in basal Eagle medium containing 10% fetal calf serum, 25 mM KCl, 2 mM glutamine, and 50 mg of gentamicin/ml. After 18 to 20 h, cytosine arabinoside (10 mM) was added to the culture media to halt non-neuronal cell proliferation. Blastocysts were collected by flushing the oviducts of female mice at 3.5 days postcoitum and cultured individually for 3 days on gelatinized coverslips in ES cell medium. Cultured blastocysts were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde-phosphate-buffered saline for 10 min at room temperature. Some samples were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde and 0.2% glutaraldehyde for 10 min at room temperature and blocked in 1 mg of NaBH4/ml for 30 min at 4°C. After primary culture from each tissue, cells were fixed in cold methanol (−20°C) and postfixed by 3% formaldehyde. Incubation with 0.15% Triton X-100 was used for cell permeabilization after fixation. Immunohistochemistry was performed based on the standard procedure. Apoptotic cells were detected by TUNEL (terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling) assay (Chemicon). Incorporated biotin was detected with an ABC kit and visualized with diaminobenzidene.

Primary cell culture, transfection, and immunofluorescence.

Establishment of mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) was performed as previously described (17, 36). A red fluorescent protein (RFP)-tagged Cre expression vector was introduced into these primary culture cells by using Lipofectamine 2000 reagents (Invitrogen). After CRE-mediated inactivation of Lis1 or Ndel1 gene, these cells were subjected to immunohistochemistry by using anti-β-tubulin antibody (Clone TUB 2.1; Sigma) or anti-β-COP antibody (Sigma). For rescue experiments, green fluorescent protein (GFP)-conjugated to LIS1, NDEL1, or NDE1 was simultaneously transfected with the CRE expression vector.

Reaggregate neuronal migration assay.

Cerebellar granule neurons were dissociated from postnatal 5-day-old mice (17, 41) and transfected with various vectors by using LipoTrust SR transfection reagents (Hokkaido System Science Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer's instructions with a small modification. Briefly, 2 × 106 cells were transfected with 3 μg of DNA vector in 4 μl of LipoTrust SR reagents in 100 μl of Dulbecco modified Eagle medium media without fetal bovine serum for 20 h, resulting in 30 to 40% transfection efficiency. Reaggregates were transferred to poly-l-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich)- and laminin (Sigma-Aldrich)-treated slides. After 15 h, the distance between cell bodies and the edge of reaggregates was measured. The details of the experimental procedure have been described (17, 41). An RFP-tagged Cre expression vector with or without GFP-tagged LIS1, NDEL1, or NDE1 vector were transfected as described above.

RESULTS

Targeted gene disruption of Ndel1.

To explore the in vivo role of NDEL1 and genetic interaction between Ndel1 and Lis1 during mitotic cell division and neuronal development, we generated two independent Ndel1 conditional KO lines (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2; see also Materials and Methods). We could not delete the PGK-neo gene used for selection in ES cells in the exon III floxed allele, and the undeleted allele with the neo insertion had a homozygous lethal phenotype identical to that of the null allele produced after deletion of the PGK-neo gene and exon III (see Materials and Methods). Therefore, we produced a conditional allele that floxed exon IV. We used mice in which exon III of Ndel1 was deleted as Ndel1+/−, whereas we used mice in which exon IV of Ndel1 was conditionally deleted as Ndel1cko/+.

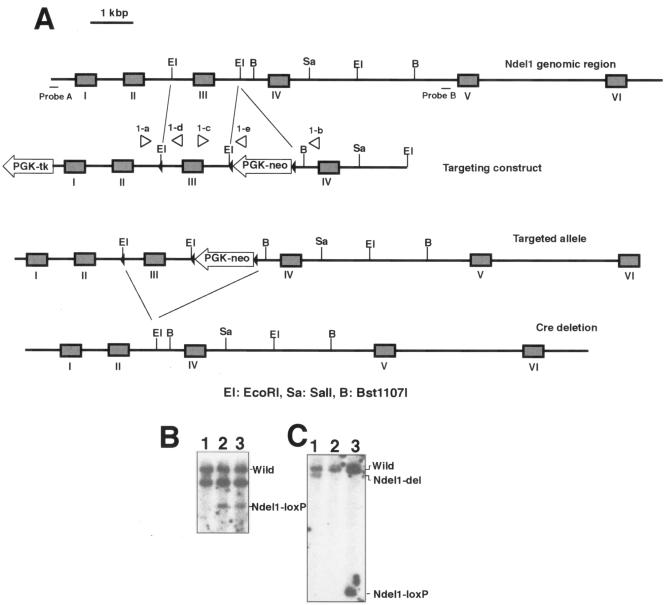

FIG. 1.

Generation of a gene-disrupted mouse of Ndel1 [Ndel1cko(III), Ndel1ko(III)]. (A) Summary of targeting strategy for the Ndel1 locus. A diagrammatic representation of the targeting vector and genomic loci of Ndel1 gene is shown. Exons are represented by gray boxes. In this gene targeting, Ndel1 function was expected to be intact (Ndel1cko(III)). Exon 3 was removed by CRE-mediated recombination to inactivate Ndel1 function [Ndel1ko(III)]. (B) Southern blot analysis of tail DNA from wild-type (+/+, lane 1) and heterozygous mutant (+/−, lanes 2 and 3) animals. (C) Southern blot analysis of tail DNA from deletion mutant (+/del, lane 1), wild-type (+/+, lane 2), and heterozygous mutant (+/loxP, lane 3) mice. CRE-mediated deletion of exon 3 was evaluated by Southern blotting. Note the difference in band sizes after deletion. We used Ndel1ko(III) as a Ndel1+/− in the all experiment.

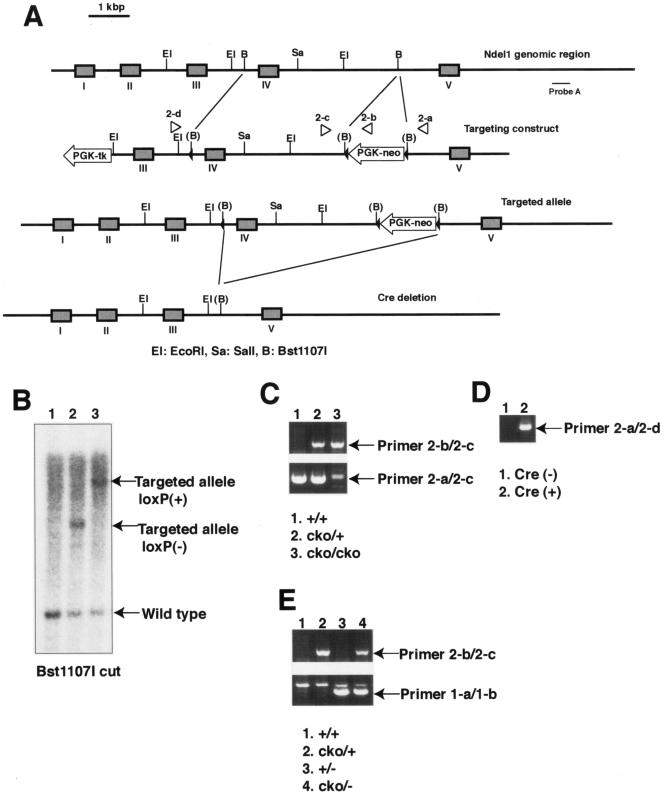

FIG. 2.

Generation of another gene disrupted mouse of Ndel1 [Ndel1cko(IV)]. (A) Summary of the second targeting strategy for the Ndel1 locus. A diagrammatic representation of the targeting vector and genomic loci of Ndel1 gene is shown. PGK-neo was inserted into intron IV, which was larger than intron III. Exon IV was removed by CRE-mediated recombination. (B) Southern blot analysis of ES cell DNA. By digestion with Bst1107I, the wild-type allele, the targeted allele that lost the loxP site, and the targeted allele that preserved the loxP site were discriminated (arrows). (C) Using this conditional KO line, we were able to make conditional homozygotes. Primers are shown on the right side (arrows). (D) CRE expression efficiently removed the DNA fragment that was demarcated by loxP sequence. (E) We mated new conditional KO mice and KO mice to make compound heterozygotes. Primers are shown on the right side. Compound heterozygotes were completely viable and fertile. We used Ndel1cko(IV) as Ndel1cko/+ in all experiments.

Mice heterozygous for the Ndel1 gene (Ndel1+/−) were outwardly normal, fertile born in appropriate Mendelian ratios. Ndel1+/− mice were bred to produce homozygous mutants (Ndel1−/−). An analysis of F2s from the mating of Ndel1+/− mice showed that the genotype ratios of +/+ to +/− to −/− animals were 70:154:0, suggesting that the complete loss of Ndel1 resulted in embryonic lethality (Table 1). Therefore, we examined embryos from heterozygous crosses at several developmental stages. Cumulative genotyping between E7.5 and E13.5 demonstrated that the ratios of +/+ to +/− to −/− mice were 26:54:0 (Table 1). We dissected embryos at between E5.5 and E13.5 and found degenerated embryos and empty deciduas only at the earliest postimplantation stages (Fig. 3A). We found 35 normal embryos (80%) and 10 empty decidua (20%) at E5.5 among 45 animals, and there were 5 +/+ (21%), 15 +/− (66%), and 3 −/− (13%) blastocyst cultures at E3.5 among 23 animals. These findings suggested that Ndel1−/− mice are lethal at very early stages of embryogenesis. This is in contrast to Nde1-null mice, which are viable and display microcephaly from defects in neurogenesis (9).

TABLE 1.

Embryos and mice used in this study

| Embryo (days p.c.) or mousea | No.b | Genotypec

|

No. resorbed | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +/+ | +/− | −/− | |||

| Embryos | |||||

| 7.5 | 10 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| 8.5 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| 9.5 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| 10.5 | 10 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| 11.5 | 12 | 3 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| 12.5 | 17 | 5 | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| 13.5 | 15 | 4 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 80 | 26 | 54 | 0 | 0 |

| Mice | |||||

| Newborn | 57 | 19 | 38 | 0 | |

| Weaning | 167 | 51 | 116 | 0 | |

| Total | 224 | 70 | 154 | 0 | |

Newborn mice were genotyped within 12 h of birth. Weaning mice were typically 4 weeks of age. p.c., postcoitus.

The number of embryos includes the number resorbed.

Genotypes for embryos were determined by PCR analysis of tissue lysate of blastocyte outgrowth for E3.5 and of yolk sac for E7.5 to E13.5. Genotypes for newborn and weaning mice were determined by PCR analysis of tail DNA.

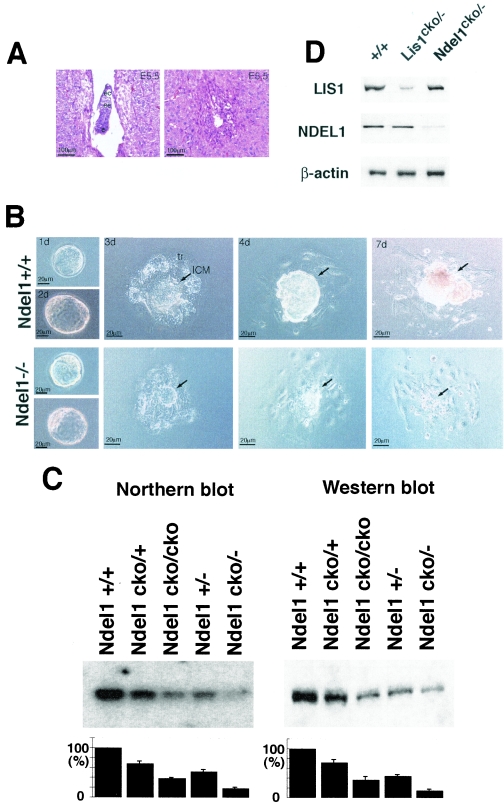

FIG. 3.

Embryonic lethality of Ndel1-null mutants. (A) Homozygous mutants of Ndel1 were not observed, suggesting that null mutants are embryonic lethal. Normal (left) and degenerated deciduas (right) resulting from the Ndel1+/− cross were sectioned at E5.5 and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. ec, ectoplacental cone; ee, extra-embryonic ectoderm; e, epiblast. (B) Wild-type (upper) and homozygous (lower) blastocysts were isolated from a heterozygous cross and cultured. Both blastocysts hatched and differentiated into trophoblast (tr) and inner cell mass (ICM). The inner cell mass of homozygotes exhibited poor growth and degenerated. (C) Quantitation of the amount of Ndel1 expression in the various genotypes. Northern blot (left side) and Western blot (right side) are shown. Expression was calculated by densitometry compared to the wild type. We repeated three independent experiments, and the results were highly reproducible. (D) Expression of LIS1 or NDEL1 in Ndel1 KO mice or Lis1 KO mice was examined. Total protein was extracted from a brain of E15.5 embryo and subjected to Western blotting. There was no obvious difference in LIS1 or NDEL1 expression in Ndel1 or Lis1 KO mice, respectively.

To define the role of NDEL1 in the early embryo, we examined the behavior of blastocyst explants isolated from Ndel1+/− crosses in culture. Genotypes of explants were performed by PCR at the end of the experiment. Wild-type, heterozygous (data not shown), and homozygous blastocysts attached to the substratum. Trophoblast cells from wild-type blastocyst explants flattened and expanded, while the inner cell mass grew on the top of the trophoblast cells (Fig. 3B). In contrast, the inner cell mass cells of Ndel1−/− blastocyst explants grew poorly after 3 days and degenerated soon thereafter. These phenotypes were previously observed in Lis1 or CDHC KO mice (14, 17).

We quantitated Ndel1 mRNA and protein expression by Northern (Fig. 3C, left) blotting and Western blotting (Fig. 3C, right), respectively. Insertion of the neo gene into intron IV partially suppressed Ndel1 expression (30%), demonstrating that the conditional allele which carries the neo gene acts as a hypomorphic mutant. To test whether either Lis1 or Ndel1 inactivation results in altered expression of NDEL1 or LIS protein, respectively, we examined LIS1 in Ndel1-disrupted mice or NDEL1 in Lis1-disrupted mice (Fig. 3D). There was no obvious effect on expression of NDEL1 or LIS1 protein by Lis1 or Ndel1 disruption, respectively.

Neuronal migration defect in Ndel1 disrupted mice and genetic interaction with Lis1.

In the adult brain (8W), Ndel1+/− mice displayed no obvious migration defects in either the neocortex or hippocampus (Fig. 4A). We further reduced the level of NDEL1 expression to ca. 20% of wild-type by making compound heterozygotes (Ndel1cko/−). Ndel1cko/− mice exhibited mild partial splitting and diffuse pyramidal cells in the CA3 and CA2 region of the hippocampus (Fig. 4A). To examine genetic interaction between Ndel1 and Lis1, we mated Ndel1+/− mice to Lis1cko/+ mice or Lis1+/− mice. Although Lis1+/− mice displayed their typical migration defect (17), Lis1cko/+ mice showed overall fairly normal brain morphology. In contrast to single heterozygotes, the pyramidal cells in the CA3 region of the hippocampus were partially split in Ndel1+/−/Lis1cko/+ double heterozygotes (Fig. 4A). Lis1+/− mice displayed severe migration defects in the hippocampus recognized by the splitting of pyramidal cells. These migration defects appeared to be slightly more severe in Ndel1+/−/Lis1+/− double heterozygotes. These results suggested that Ndel1 and Lis1 genetically interacted during neuronal migration. The abnormal layering in the hippocampus was also clearly visualized by NeuN staining, a marker for terminal differentiation of neurons (Fig. 4B) (28). We assessed defects in cortical architecture and fragmentation of the subplate by immunohistochemical analysis with MAP2, which specifically identifies dendritic extensions of postmitotic neurons. In wild-type and Lis1cko/+ embryos, MAP2-positive neuronal processes were arranged radially to form a tight, palisade-like pattern at the cortical plate (Fig. 4C, upper panels). MAP2 also stains the horizontal processes of subplate neurons (23) but not those in the intermediate zones (34). In contrast, radial and palisade staining of the cortical plate became irregular, and horizontal staining of the subplate was fragmented in Ndel1cko/−, Ndel1+/−/Lis1cko/+, and Ndel1+/−/Lis1+/− double heterozygotes compared to Ndel1+/− or Lis1cko/+ single heterozygotes. Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan is distributed in the marginal zone and the subplate (37). This marker also revealed fragmentation and abnormal organization of the subplate from Ndel1cko/− mice (Fig. 4C, lower panels). Consistent with the biochemical interaction of LIS1 and NDEL1 (36), these developmental studies further suggest that Lis1 and Ndel1 genetically interact and synergistically regulate neuronal migration.

FIG. 4.

Synergistic effects of Lis1 and Ndel1 mutations on brain morphogenesis. Genotypes are shown at the top of the panels. (A) Midsagittal sections of cerebral cortex (upper) and hippocampus (lower). Lis1cko/+ or Ndel1+/− samples were grossly normal. In contrast, mild cell dispersion of CA3 region was observed in Ndel1cko/− compound heterozygotes or Lis1cko/+ and Ndel1+/− double heterozygotes (arrowheads). (B) Loss of cell compaction (arrowheads) in CA3 region was clearly observed by NeuN staining. (C) Abnormal corticogenesis was characterized by fragmentation of the subplate layer (arrowheads) which was visualized by MAP2 staining (upper panels) and chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan staining (lower panels) at E15.5. MZ, marginal zone; CP, cortical plate; SP, subplate; IZ, intermediate zone.

BrdU birth dating analysis of Ndel1-disrupted mice and genetic interaction with Lis1.

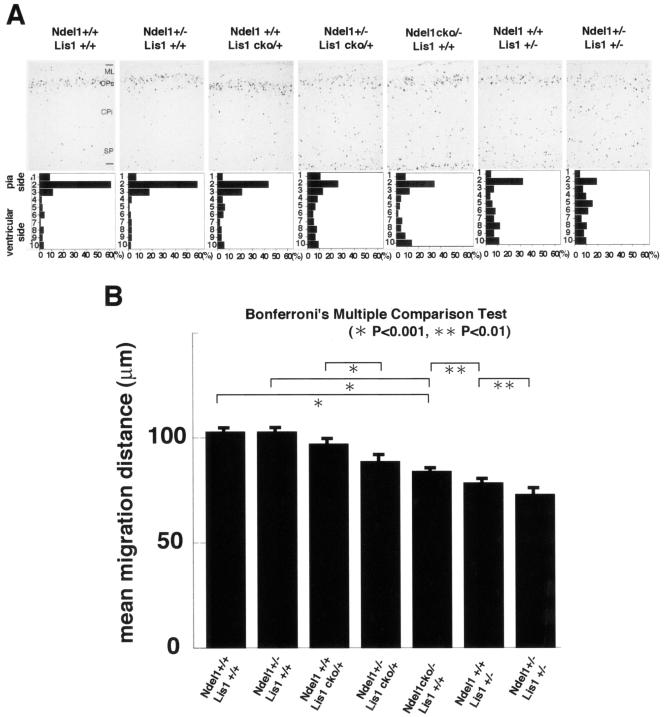

To confirm that the morphological defects observed in the several genetic combinations were due to abnormal neuronal migration, we performed quantitative BrdU birth dating analysis on each genetic combination. As the dose of NDEL1 was reduced, the distribution of labeled cells was shifted downward toward the ventricular zone in the cortex, and BrdU labeling was more diffusely localized (Fig. 5A, Ndel1cko/−/Lis1+/+). The migration defects associated with the reduction of NDEL1 became more severe in the presence of reduced levels of LIS1 (Fig. 5A, Ndel1+/−/Lis1cko/+) compared to Ndel1+/− or Lis1cko/+ mutants. Although Lis1+/− mutants displayed migration defects, additional heterozygous loss of NDEL1 significantly reduced the cell population that reached layer II (Fig. 5A, Ndel1+/−/Lis1+/−). Although heterozygous loss of NDEL1 was not sufficient for the creation of a clear migration defect as in the Lis1+/− mutants, combinatorial loss of Ndel1 and Lis1 clearly led to a migration defect (Fig. 5B), suggesting that LIS1 and NDEL1 cooperatively function during neuronal migration in the cortex, as well as in the hippocampus.

FIG. 5.

Examination of migration defects of Lis1 and Ndel1 mutants. (A) BrdU birth dating analysis reveals neuronal migration defects in the cross of Ndel1+/− and Ndel1cko/+, in the cross of Lis1cko/+ and Ndel1+/−, or in the cross of Lis1+/− and Ndel1+/−. Genotypes are described at the top of the panels. Mice were injected with BrdU at E15.5 and sacrificed at P0. Quantitative analysis was performed by measuring the distribution of BrdU-labeled cells in each bin which equally divided the cortex from the molecular layer (ML) to the subplate (SP). The staining patterns are representative of three different experiments. Note the shift downward toward the ventricular side as Lis1 or Ndel1 dosage was reduced. CPs, cortical plate surface; CPi, cortical plate inner. (B) Summary of mean migration distance of each genotype.

Apoptotic cell death in Ndel1-disrupted mice and Lis1 mutants.

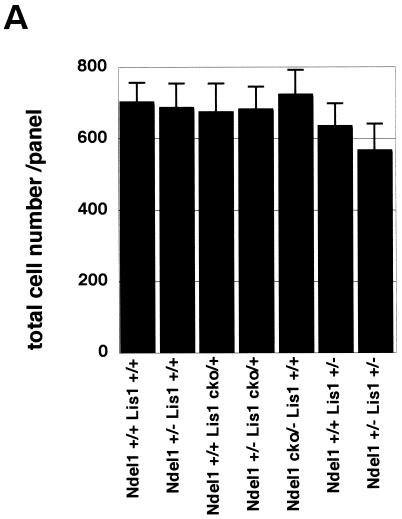

We observed mild reduction of the density of cells in the neocortex of the Ndel1+/+/Lis1+/− mice and the Ndel1+/−/Lis1+/− mice (Fig. 6A). To determine potential defects of corticogenesis due to reduction of LIS1 and/or NDEL1, we analyzed C-Neu immunoreactivity to label the large pyramidal neurons of layer 5 (43) and calbindin immunoreactivity to label the interneurons of layers 2 and 3 (24) in the adult cortex (8W) of these different crosses (Fig. 6B). C-Neu-positive cells that migrate at an early stage exhibited broader distribution in Ndel1cko/−/Lis1+/+, Ndel1+/+/Lis1+/−, and Ndel1+/−/Lis1+/− genotypes, whereas calbindin-positive cells which migrate at a later stage exhibited broader distribution in Ndel1+/−/Lis1cko/+, Ndel1cko/−/Lis1+/+, Ndel1+/+/Lis1+/−, and Ndel1+/−/Lis1+/− genotypes, suggesting that later migrating neurons are more sensitive to reduction of LIS1 and/or NDEL1. Quantitation of densities indicated mild reduction of calbindin-positive cells in the cortexes of the Ndel1+/+/Lis1+/− mice and the Ndel1+/−/Lis1+/− mice, whereas C-Neu positive cells did not display obvious genotype-dependent differences (Fig. 6C). These results prompted us to investigate apoptotic cell death during corticogenesis in various crosses by TUNEL (terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling) staining (Fig. 6D). At E11.5 when early migrating neurons are generated, significant differences of apoptotic cell death were not observed. In contrast, at E15.5 when later migrating neurons are generated, significant acceleration of apoptotic cell death in the ventricular zone were observed. In particular, cell death was correlated with the reduction of LIS1 amount, a finding in good agreement with the reduction of calbindin-positive cells in the cortexes of the Ndel1+/+ Lis1+/− mice and Ndel1+/− Lis1+/− mice (Fig. 6E).

FIG. 6.

Specific defect of corticogenesis and apoptotic cell death by Lis1 or Ndel1 disruption. (A) Quantitation of cell number of the cortex in various combination of Lis1 KO and/or Ndel1 KO mice. After hematoxylin and eosin staining of the sagittal sections of the cortexes of 8W adult mice, samples were subjected to cell counting. The cell counts of three corresponding sections in each genotype were determined. The histogram indicates the cell number. Mild reduction of cell number was observed in Lis1+/−/Ndel1+/+ and Lis1+/−/Ndel1+/− mutants. (B) Cortical phenotypes of Lis1 and/or Ndel1 mutants (adult, 8W) were examined by layer specific makers, calbindin (layer 2 and 3) and c-Neu (layer 5). We measured five independent sides from each genotype. Total number of calbindin-positive cells is shown at the bottom of each panel. Calbindin-positive cells were more dispersed in Ndel1+/−/Lis1cko/+, Ndel1cko/−/Lis1+/+, Ndel1+/+/Lis1+/−, and Ndel1+/−/Lis1+/− mice, whereas c-Neu-positive cells were more broadly distributed in Ndel1cko/−/Lis1+/+, Ndel1+/+/Lis1+/−, and Ndel1+/−/Lis1+/− mice. Although the distribution became more broad and overlapped, inversion of layering was not observed. Genotypes are noted at the top of the panel. (C) Histogram plots of the relative frequency of calbindin-positive cells and c-Neu-positive cells to the total cell number in each genotype. Notably, later-migrating neurons (calbindin-positive cells) were more sensitive to LIS1 and NDEL1 dosage. (D) Apoptotic cell death was examined by TUNEL stainong at E11.5 and E15.5. We measured five independent sides from each genotype. The total number of calbindin-positive cells is shown at the bottom of each panel. (E) Histogram plot of the relative frequency of TUNEL-positive cell to the total number of cells in each genotype. There was no obvious increase of cell death in early generated neurons. In contrast, significant enhancement of cell death was observed in neurons generated later, a finding consistent with loss of calbindin-positive cells, and cell death was highly correlated with the reduction of LIS1 dosage.

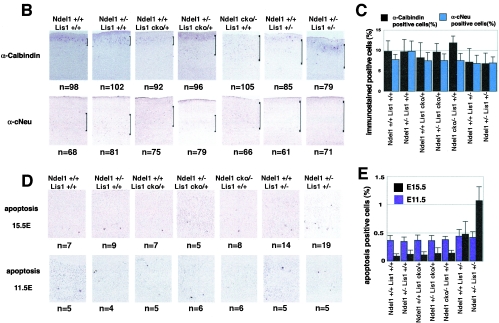

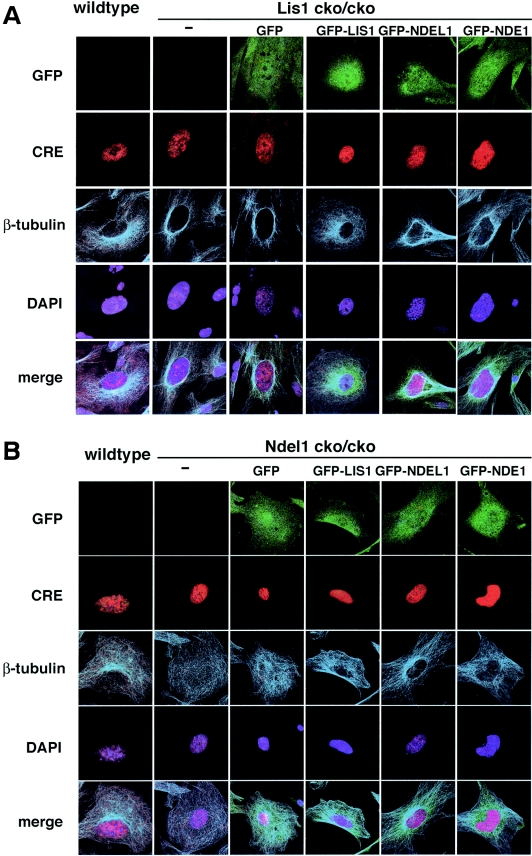

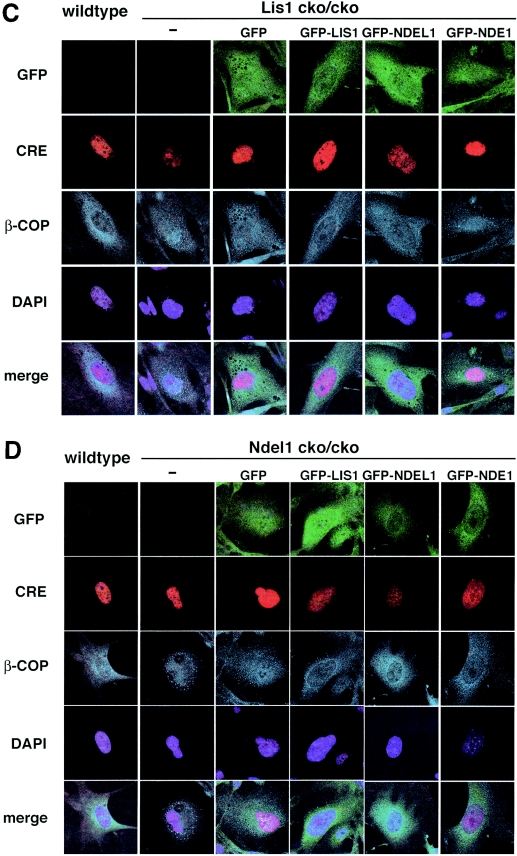

Abnormal organization of microtubules and distribution of β-COP-positive vesicles in Lis1- or Ndel1-null MEFs.

We next addressed LIS1 and NDEL1 functions on microtubule organization and dynein regulation. In wild-type MEFs, microtubule arrays were displayed throughout the cell from a clear focus that likely represented the centrosome (Fig, 7A). Loss of either Lis1 or Ndel1 caused profound changes in the organization of microtubules of MEFs. Microtubules exhibited a perinuclear concentration in Lis1-disrupted MEFs (39) (Fig. 7A). This aberrant distribution of microtubules in Lis1-null MEFs was only rescued by exogenous GFP-LIS1 expression (Fig. 7A) but not by GFP-NDEL1 or GFP-NDE1. In contrast, microtubules in Ndel1-disrupted MEFs displayed an amorphous and fragile pattern (Fig. 7B). Similarly, the microtubule organization defect in Ndel1-null MEFs was efficiently rescued by GFP-NDEL1 but not by either LIS1 or NDE1, which only slightly rescued the disorganization of microtubules (Fig. 7B). Based on the different phenotypes in Lis1- and Ndel1-null MEFs, these data suggest that NDEL1 plays a distinct role in the regulation of microtubule organization.

FIG.7.

Disruption of microtubule organization and distribution of β-COP-positive vesicles in Lis1- or Ndel1-null MEFs. Aberrant microtubule organization and abnormal distribution of β-COP-positive vesicles in Lis1 or Ndel1-null MEFs generated by CRE-mediated recombination. Cotransfected plasmids for rescue were shown on the top. (A and B) The loss of LIS1 causes a redistribution and an enrichment of microtubules near the nucleus (A), whereas loss of NDEL1 results in amorphous microtubules (B). Perinuclear accumulation of microtubules in Lis1-null MEFs was only rescued by GFP-LIS1 expression (see panel A). GFP-NDEL1 expression also rescued the amorphous microtubule organization in Ndel1-null MEFs, but GFP-LIS1 and GFP-NDE1 were less effective (see panel B). To address dynein regulation by LIS1 and NDEL1, we examined the distribution of β-COP-positive vesicles, which display juxtanuclear localization in a dynein-dependent fashion. (C and D) The predominant juxtanuclear staining pattern was disrupted in Lis1-null MEFs (C) and in Ndel1-null MEFs (D), resulting in a homogeneous distribution accompanied by punctuate accumulation. Loss of this Golgi pattern by Lis1 inactivation was only rescued by exogenous expression of GFP-LIS1 (see panel C). In contrast, loss of the Golgi pattern by Ndel1 inactivation was efficiently rescued by exogenous expression of GFP-LIS1, GFP-NDEL1, and GFP-NDE1 (see panel D).

We also examined the distribution of β-COP-positive vesicles. β-COP proteins are part of a coatomer complex that recruits some specific areas of the endomembrane system to the Golgi complex in a cytoplasmic dynein-dependent fashion (5). Immunofluorescence demonstrated that β-COP-positive vesicles displayed a predominantly juxtanuclear staining pattern in wild-type MEFs (Fig. 7C). Upon inactivation of Lis1 or Ndel1 by CRE recombinase, this clustering in the juxtanuclear region was disrupted, and β-COP was redistributed homogeneously within the cell accompanied by a punctuate accumulation (Fig. 7C and D). Aberrant distribution of β-COP positive vesicles in Lis1-null MEFs was only rescued by exogenous introduction of GFP-LIS1 (Fig. 7C). In contrast, disrupted organization of of β-COP-positive vesicles in Ndel1-null MEFs was efficiently rescued by GFP-NDE1, as well as GFP-NDEL1, and it was partially rescued by GFP-LIS1 (Fig. 7D). These data suggest that LIS1, NDEL1, and NDE1 share some overlapping and some distinct functions in the regulation of cytoplasmic dynein function.

Neuronal migration defects in Lis1 and Ndel1 mutant granule cells.

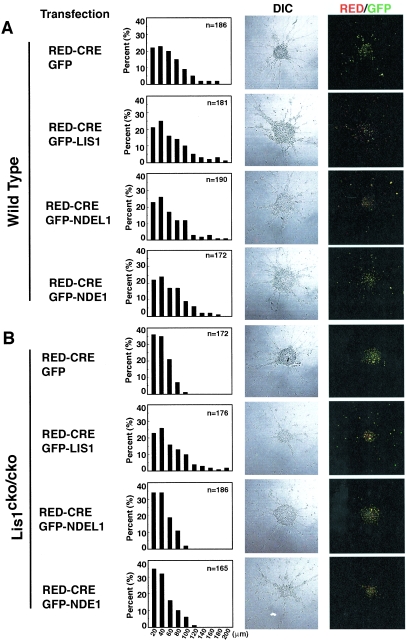

To define the mechanistic roles of NDEL1 and LIS1 in mammalian neuronal migration, we used mouse cerebellar granule neurons in an in vitro migration assay with wild-type or mutant neurons (17, 41). Migration distances in neurons transfected with RFP-CRE alone were positioned indistinguishably from untransfected neurons, suggesting that RFP-CRE transfection had no effect on migration (Fig. 8A and D). Overexpression of LIS1-GFP led to a mild increase in neuronal migration (Fig. 8A and D), as previously reported (41), whereas GFP-NDEL1 or GFP-NDE1 overexpression had no such effect (Fig. 8A,D). Lis1-null granule neurons displayed severe migration defects compared to wild-type neurons, characterized by a leftward shift of the bin distribution of migration distance, and the mean distance decreased by ∼60% from the WT level (Fig. 8B and D). This migration defect due to Lis1 inactivation was efficiently rescued by exogenous expression of GFP-LIS1 (Fig. 8B and D) but not by GFP-NDEL1 or GFP-NDE1.

FIG.8.

Migration distance in Lis1- or Ndel1-null neurons determined by reaggregation assay. Granular neurons were isolated from P3 neonatal pups and subjected to the neuronal migration reaggregation assay. Lis1 or Ndel1 was inactivated by CRE-mediated recombination. Cotransfected plasmids for rescue are shown on the left side. The migration distance of each neurons after 12 h was binned. (A) Wild-type neurons expressing RFP-CRE display normal migration distance compared to untransfected neurons. Cotransfection of GFP-LIS1 mildly enhanced migration, whereas GFP-NDEL1 or GFP-NDE1 did not have obvious effect. (B and C) Lis1 (B)- or Ndel1 (C)-null neurons display a shift in the distribution of bins toward the right. Migration defects in Lis1-null neurons were only rescued by exogenous expression of GFP-LIS1. Migration defects in Ndel1-null neurons were rescued by exogenous expression of GFP-LIS1, GFP-NDEL1, and GFP-NDE1, but GFP-LIS1 and GFP-NDE1 were less effective (see panel C). Mean migration distances are summarized at the bottom. n, Number of neurons measured for each examination. (D) Summary of mean migration distance of each genotype.

Similar migration defects were observed in Ndel1-null neurons (Fig. 8C and D). This migration defect due to loss of Ndel1 was rescued by exogenous expression of GFP-NDEL1 (Fig. 8C and D). GFP-LIS1 expression only moderately rescued the migration defect. More interestingly, GFP-NDE1 expression partially but incompletely rescued the migration defect derived from loss of Ndel1. The reduced magnitude of rescue suggests that NDEL1 and NDE1 have similar functions, but NDEL1 might have a more crucial and distinct function. These data are consistent with the early embryonic lethality displayed by Ndel1-null mice compared to the viable phenotype of Nde1-null mice, as well as the less-efficient recovery of disorganized microtubule network in Ndel1-null MEFs by GFP-NDE1 expression.

DISCUSSION

Ndel1 is one of the mouse homologues of Nude from Aspergillus, which was identified as a multicopy suppressors of a mutation in the nudF gene, the Aspergillus homologue of LIS1 (6). NudE is also a homologue of the nuclear distribution protein RO11 (24) of Neurospora crassa and mitotic phosphoprotein 43 of Xenopus laevis (6). LIS1 and NDEL act in the CDHC pathway, which is the large molecular motor that translocates to the minus (−) ends of microtubules. Dynein, whose motor domain comprises six AAA modules and two potential mechanical levers, generates movement by a mechanism that is fundamentally different than that which underlies the motion of myosin and kinesin. CDHC is involved in numerous functions, including microtubule organization, vesicle transport (especially from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi apparatus), chromosome separation, and nuclear distribution (12, 16, 45, 46).

To understand the in vivo role of NDEL1, we generated Ndel1-disrupted mice. Complete loss of NDEL1 caused embryonic lethality at the peri-implantation stage and a deficiency of cell proliferation in the inner cell mass. These data suggest that NDEL1-dependent regulation of CDHC is essential for proliferation and may play a role in important aspects of mitosis. Compared to Lis1+/− mice, which displayed clear neuronal migration defects (10, 17), Ndel1+/− mice did not exhibit obvious phenotypes. Further reduction of Ndel1 using a hypomorphic conditional allele resulted in mild neuronal migration defects. Double Lis1/Ndel1 mutants displayed more severe migration defect than single mutants, suggesting that Lis1 and Ndel1 genetically interact. Elevated apoptotic cell death during neurogenesis was observed in Lis1 mutants, whereas mutation of Ndel1 did not result in apoptosis. We also examined LIS1 and NDEL1 functions on dynein regulation and microtubule organization. Lis1- and Ndel1-null MEFs displayed similar disruption of the compact juxtanuclear Golgi complex of β-COP-positive vesicles. The aberrant distribution of β-COP-positive vesicles in Lis1-null MEFs was only rescued by exogenous introduction of GFP-LIS1, while the disrupted organization of β-COP-positive vesicles in Ndel1-null MEFs was efficiently rescued by GFP-NDE1, as well as GFP-NDEL1, and it was partially rescued by GFP-LIS1. Lis1 disruption resulted in pernuclear accumulation of microtubules, whereas Ndel1 inactivation displayed amorphous distribution of microtubules. We also demonstrated that the disorganized microtubule network in Ndel1-null cells was completely rescued by GFP-NDEL1 but only partially rescued by GFP-LIS1 and GFP-NDE1. These results were similar to those found for neuronal migration using cerebellar granule cell reaggregation assays. Neuronal migration defects displayed by Ndel1-null neurons were completely rescued by GFP-NDEL1 but only partially rescued by GFP-LIS1 or GFP-NDE1 exogenous expression. Our data suggest that NDEL1, LIS1, and NDE1 act in a common pathway to regulate dynein but that each has distinct roles in the regulation of microtubule organization and neuronal migration.

Neuronal migration is the critical cellular process which initiates corticogenesis of cerebral cortex. Upon becoming postmitotic after their final mitosis, neurons migrate from the ventricular zone toward the cortical plate and then establish neuronal lamina via an “inside-out” gradient of maturation. Mutations of genes involved in neuronal migration result in defects of corticogenesis. Lis1+/− mutants display recognizable neuronal migration defects. In contrast, Ndel1+/− mutants exhibited no obvious phenotypes, Ndel1cko/− mutants exhibited clear aberration of neuronal migration, although the phenotype was milder than the phenotype of Liscko/− mutants. We also demonstrated synergistic regulation of neuronal migration by LIS1 and NDEL1 using various crosses of Lis1 and Ndel1 mutants, suggesting that LIS1 and NDEL1 at least partially share the same pathway during neuronal migration. A recent report indicated that loss of function of Ndel1, Lis1, or dynein by RNA interference in the developing neocortex impairs neuronal positioning and causes the uncoupling of the centrosome and nucleus. These observations support our conclusion that LIS and NDEL1 share a common neuronal migration pathway (38).

In the developing central nervous system apoptosis plays an important role in the normal organization of the neuronal circuit. Roughly half of all of the neurons produced during neurogenesis die apoptotically before the nervous system matures (22). We have demonstrated that apoptotic cell death is significantly elevated in Lis1 mutants. Apoptotic cell death was restricted to the ventricular zone, suggesting that LIS1 is essential for cell division of neuronal stem cells. Interestingly, neurons generated later were more sensitive to the reduction of LIS1. Long-lasting reduction of LIS1 might cause deregulation of proliferation and/or accumulation of disorganized organellar distribution that might trigger apoptosis or increase sensitivity to apoptotic inducers. Although migration defects were observed in brains from Ndel1cko/− mice, apoptotic cell death was not observed.

Another recent report demonstrated that the targeted disruption of the second homologue of NudE, Nde1, resulted in viable mice with a small brain (microcephaly) phenotype, with the most dramatic reduction affecting the cerebral cortex (9). In Nde1 mutants (Nde1−/−), cortical lamination was mostly preserved, but the mutant cortex had fewer neurons and very thin superficial cortical layers (II to IV). The small cerebral cortex is thought to reflect both reduced progenitor cell division and altered neuronal cell fates. In contrast to Nde1, complete loss of Ndel1 resulted in perimplanation lethality, a phenotype similar to complete loss-of-function of Lis1 (17) and Cdhc (14). Ndel1 mutants more clearly displayed neuronal migration defect than Nde1 mutants. These phenotypic differences between two homologues could be attributed to differences in the pattern and levels of expression during development (8, 29, 35, 36). NDE1 is expressed mainly in neuronal stem cells and is downregulated in the postmitotic neurons. In contrast, NDEL1 is first expressed in first in the early embryo. Later, NDEL1 is expressed in neuronal stem cells, and its expression continues in postmitotic neurons, suggesting that NDEL1 plays a broader role during development than NDE1. Another nonexclusive possibility is that NDEL1 has distinct molecular targets from NDE1. This possibility is supported by our observations that the disorganized microtubule network seen in the NDEL1-null MEFs was not completely rescued by NDE1 expression. Partial rescue of neuronal migration defect in NDEL1-null neurons by NDE1 introduction also supports this possibility. Further experiments with mutant mice for each of these components, which are now all available, as well as further biochemical studies, will provide more detailed explanations to address the similarities and differences in the roles of LIS1, NDEL1, and NDE1 in the regulation of dynein function and microtubule organization, as well as their roles in proliferation, neurogenesis, and neuronal migration.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yoshihiko Funae, Hiroshi Iwao, Toshio Yamauch, Yoshitaka Nagai, and L. Robert Nussbaum for generous support and encouragement. We are grateful to Yuzuru Yamauchi, Shino Okumura, Michiyo Ishida, Katsumi Hagiwara, Nobuko Tominaga, Masami Suzuki, and Masashi Harada for mouse breeding and technical support. We thank Shin-ichi Hisanaga for providing a recombinant protein of cdk5/p35 and Francis J. MacNally for providing mutated kinesin.

This study was supported by NIH grant NS41030 to A.W.-B. and Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture of Japan to A.Y., K.T., and S.H. This study was also supported by Nissan Science Foundation grants to K.T. and a Sankyo Foundation of Life Science and Japan Brain Foundation grant to S.H.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chae, T., Y. T. Kwon, R. Bronson, P. Dikkes, E. Li, and L. H. Tsai. 1997. Mice lacking p35, a neuronal specific activator of Cdk5, display cortical lamination defects, seizures, and adult lethality. Neuron 18:29-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deng, C., A. Wynshaw-Boris, F. Zhou, A. Kuo, and P. Leder. 1996. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 is a negative regulator of bone growth. Cell 84:911-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dobyns, W. B. 1987. Developmental aspects of lissencephaly and the lissencephaly syndromes. Birth Defects 23:225-241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dobyns, W. B., O. Reiner, R. Carrozzo, and D. H. Ledbetter. 1993. Lissencephaly: a human brain malformation associated with deletion of the LIS1 gene located at chromosome 17p13. JAMA 23:2838-2842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donaldson, J. G., J. Lippincott-Schwartz, G. S. Bloom, T. E. Kreis, and R. D. Klausner. 1990. Dissociation of a 110-kD peripheral membrane protein from the Golgi apparatus is an early event in brefeldin A action. J. Cell Biol. 111:2295-2306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Efimov, V. P., and N. R. Morris. 2000. The LIS1-related NUDF protein of Aspergillus nidulans interacts with the coiled-coil domain of the NUDE/RO11 protein. J. Cell Biol. 150:681-688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faulkner, N. E., D. L. Dujardin, C. Y. Tai, K. T. Vaughan, C. B. O'Connell, Y. Wang, and R. B. Vallee. 2000. A role for the lissencephaly gene LIS1 in mitosis and cytoplasmic dynein function. Nat. Cell Biol. 2:784-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feng, Y., E. C. Olson, P. T. Stukenberg, L. A. Flanagan, M. W. Kirschner, and C. A. Walsh. 2000. Interactions between LIS1 and mNudE, a central component of the centrosome, are required for CNS lamination. Neuron 28:665-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feng, Y., and C. A. Walsh. 2004. Mitotic spindle regulation by nde1 controls cerebral cortical size. Neuron 44:279-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gambello, M. J., D. L. Darling, J. Yingling, T. Tanaka, J. G. Gleeson, and A. Wynshaw-Boris. 2003. Multiple dose-dependent effects of Lis1 on cerebral cortical development. J. Neurosci. 23:1719-1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilmore, E. C., T. Ohshima, A. M. Goffinet, A. B. Kulkarni, and K. Herrup. 1998. Cyclin-dependent kinase 5-deficient mice demonstrate novel developmental arrest in cerebral cortex. J. Neurosci. 18:6370-6377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gee, M. A., J. E. Heuser, and R. B. Vallee. 1997. An extended microtubule-binding structure within the dynein motor domain. Nature 390:636-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta, A., L. H. Tsai, and A. Wynshaw-Boris. 2002. Life is a journey: a genetic look at neocortical development. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3:342-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harada, A., Y. Takei, Y. Kanai, Y. Tanaka, S. Nonaka, and N. Hirokawa. 1998. Golgi vesiculation and lysosome dispersion in cells lacking cytoplasmic dynein. J. Cell Biol. 141:51-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hattori, M., H. Adachi, M. Tsujimoto, H. Arai, and K. Inoue. 1994. Miller-Dieker lissencephaly gene encodes a subunit of brain platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase. Nature 370:216-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Helfand, B. T., A. Mikami, R. B. Vallee, and R. D. Goldman. 2002. A requirement for cytoplasmic dynein and dynactin in intermediate filament network assembly and organization. J. Cell Biol. 157:795-806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirotsune, S., M. W. Fleck, M. J. Gambello, G. J. Bix, A. Chen, G. D., Clark, D. H. Ledbetter, C. J. McBain, and A. Wynshaw-Boris. 1998. Graded reduction of Pafah1b1 (Lis1) activity results in neuronal migration defects and early embryonic lethality. Nat. Genet. 19:333-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwon, Y. T., and L. H. Tsai. 2000. The role of the p35/cdk5 kinase in cortical development. Results Probl. Cell Differ. 30:241-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lakso, M., J. G. Pichel, J. R. Gorman, B. Sauer, Y. Okamoto, E. Lee, F. W. Alt, and H. Westphal. 1996. Efficient in vivo manipulation of mouse genomic sequences at the zygote stage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:5860-5865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu, Z., T. Xie, and R. Steward. 1999. Lis1, the Drosophila homologue of a human lissencephaly disease gene, is required for germline cell division and oocyte differentiation. Development 126:4477-4488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu, Z., R. Steward, and L. Luo. 2000. Drosophila Lis1 is required for neuroblast proliferation, dendritic elaboration and axonal transport. Nat. Cell Biol. 2:776-783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu, D. X., and L. A. Greene. 2001. Neuronal apoptosis at the G1/S cell cycle checkpoint. Cell Tissue Res. 305:217-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luskin, M. B., and C. J. Shatz. 1985. Studies of the earliest generated cells of the cat's visual cortex: cogeneration of subplate and marginal zones. J. Neurosci. 99:7881-7888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller, M. W., and F. A. Pitts. 2000. Neurotrophin receptors in the somatosensory cortex of the mature rat: colocalization of p75, trk, isoforms and c-Neu. Brain Res. 852:355-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Minke, P. F., I. H. Lee, J. H. Tinsley, K. S. Bruno, and M. Plamann. 1999. Neurospora crassa ro-10 and ro-11 genes encode novel proteins required for nuclear distribution. Mol. Microbiol. 32:1065-1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morris, R. N., V. P. Efimov, and X. Xiang. 1998. Nuclear migration, nucleokinesis, and lissencephaly. Trends Cell Biol. 8:467-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morris, R. N. 2000. Nuclear migration: from fungi to the mammalian brain. J. Cell Biol. 148:1097-1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mullen, R. J., C. R. Buck, and A. M. Smith. 1992. NeuN, a neuronal specific nuclear protein in vertebrates. Development 116:201-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niethammer, M., D. S. Smith, R. Ayala, J. Peng, J. Ko, M. Lee, M. Morabito, and L. Tsai. 2000. The Lis1 interacting protein Nude1 is a Cdk5 substrate that interacts with cytoplasmic dynein. Neuron 28:697-711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oshima, T., J. M. Ward, C. G. Huh, G. Longenecker, C. Veeranna, H. Pant, R. O. Brady, L. J. Martin, and A. B. Kulkarni. 1996. Targeted disruption of the cyclin-dependent kinase 5 gene results in abnormal corticogenesis, neuronal pathology and perinatal death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:11173-11178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pliz, D. T., N. Matsumoto, S. Minnerath, P. Mills, and J. G. Glesson. 1999. Lis1 and XLIS/doublecortin mutations cause most human classical lissencephaly, but different patterns if malformation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 7:2029-2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rakic, P. 1972. Model of cell migration to the superficial layers of fetal monkey neocortex. J. Comp. Neurol. 145:61-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reiner, O., R. Carrozzo, Y. Shen, M. Wehnert, F. Faustinella, W. B. Dobyns, T. Caskey, and D. H. Ledbetter. 1993. Isolation of a Miller-Dieker lissencephaly gene containing G protein b-subunit-like repeat. Nature 364:717-721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ringstedt, T., S. Linnarsson, J. Wagnoer, U. Lendahl, Z. Kokaia, E. Arenas, P. Ernfors, and C. F. Ibanez. 1998. BDNF regulates reelin expression and Cajal-Retzius cell development in the cerebral cortex. Neuron 21:305-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saito, T., R. Onuki, Y. Fujita, G. Kusakawa, K. Ishiguro, J. A. Bibb, T. Kishimoto, and S. Hisanaga. 2003. Developmental regulation of the proteolysis of the p35 cyclin-dependent kinase 5 activator by phosphorylation. J. Neurosci. 23:1189-1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sasaki, S., A. Shionoya, M. Ishida, M. J. Gambello, J. Yingling, A. Wynshaw-Boris, and S. Hirotsune. 2000. A LIS1/NUDEL/cytoplasmic dynein heavy chain complex in the developing and adult nervous system. Neuron 28:681-696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sheppard, A. M., and A. L. Pearlman. 1997. Abnormal organization of preplate neurons and their associated extracellular matrix: an early manifestation of altered neocortical development in the reeler mutant mouse. J. Comp. Neurol. 378:173-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shu, T., R. Ayala, M. D. Nguyen, Z. Xie, J. G. Gleeson, and L. H. Tsai. 2004. Ndel1 operates in a common pathway with LIS1 and cytoplasmic dynein to regulate cortical neuronal positioning. Neuron 44:263-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith, D. S., M. Niethammer, R. Ayala, Y. Zhou, M. J. Gambello, A. Wynshaw-Boris, and L.-H. Tsai. 2000. Regulation of cytoplasmic dynein behaviour and microtubule organization by mammalian Lis1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2:767-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Swan, A., T. Nguyen, and B. Suter. 1999. Drosophila lissencephaly-1 functions with Bic-D and dynein in oocyte determination and nuclear positioning. Nat. Cell Biol. 1:444-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanaka, T., Serneo, C. F. F. Higgins, M. J. Gambello, A. Wynshaw-Boris, and J. G. Gleeson. 2004. Lis1 and doublecortin function with dynein to mediate coupling of the nucleus to the centrosome in neuronal migration. J. Cell Biol. 165:709-721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Toyo-oka, K., A. Shionoya, M. J. Gambello, C. Cardoso, R. Leventer, H. L. Ward, R. Ayala, L. H. Tsai, W. Dobyns, D. Ledbetter, S. Hirotsune, and A. Wynshaw-Boris. 2003. 14-3-3epsilon is important for neuronal migration by binding to NUDEL: a molecular explanation for Miller-Dieker syndrome. Nat. Genet. 34:274-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trommsdorff, M., M. Gotthardt, T. Hiesberger, J. Shelton, W. Stockinger, J. Nimpf, R. E. Hammer, J. A. Richardson, and J. Herz. 1999. Reeler/Disabled-like disruption of neuronal migration in knockout mice lacking the VLDL receptor and ApoE receptor 2. Cell 97:689-701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xiang, X., A. H. Osmani, S. A. Osmani, M. Xin, and N. R. Morris. 1995. NudF, a nuclear migration gene in Aspergillus nidulans, is similar to the human LIS-1 gene required for neuronal migration. Mol. Biol. Cell 6:297-310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vallee, R. B., J. S. Wall, B. M. Paschal, and H. S. Shpetner. 1988. Microtubule-associated protein 1C from brain is a two-headed cytosolic dynein. Nature 332:561-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vallee, R. B., and M. P. Sheetz. 1996. Targeting of motor proteins. Science 271:1539-1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Willins, D. A., B. Liu, X. Xiang, and N. R. Morris. 1997. Mutations in the heavy chain of cytoplasmic dynein suppress the nudF nuclear migration mutation of Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Gen. Genet. 255:194-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]