Abstract

The contribution of erythropoietin to the differentiation of the red blood cell lineage remains elusive, and the demonstration of a molecular link between erythropoietin and the transcription of genes associated with erythroid differentiation is lacking. In erythroid cells, expression of the tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase (TIMP-1) is strictly dependent on erythropoietin. We report here that erythropoietin regulates the transcription of the TIMP-1 gene upon binding to its receptor in erythroid cells by triggering the activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt. We found that Akt directly phosphorylates the transcription factor GATA-1 at serine 310 and that this site-specific phosphorylation is required for the transcriptional activation of the TIMP-1 promoter. This chain of events can be recapitulated in nonerythroid cells by transfection of the implicated molecular partners, resulting in the expression of the normally silent endogenous TIMP-1 gene. Conversely, TIMP-1 secretion is profoundly decreased in erythroid cells from fetal livers of transgenic knock-in mice homozygous for a GATAS310A gene, which encodes a GATA-1 mutant that cannot be phosphorylated at Ser310. Furthermore, retrovirus-mediated expression of GATAS310A into GATA-1null-derived embryonic stem cells decreases the rate of hemoglobinization by more than 50% compared to expressed wild-type GATA-1. These findings provide the first example of a chain of coupling mechanisms between the binding of erythropoietin to its receptor and GATA-1-dependent gene expression.

The study of the differentiation of hematopoietic cells toward the red blood cell lineage has proven very fertile to probe the fundamental questions of tissue-specific control of gene expression and signal transduction upon binding of a cytokine to its receptor. Yet, these two fields have largely progressed independently, and data documenting a molecular link between erythropoietin (Epo) signaling and regulation of erythroid gene expression are still lacking.

In hematopoietic cells, expression of GATA-1 is restricted to erythroid cells, megakaryocytes, eosinophils, and mast cells (3, 24, 33). All known erythroid genes are regulated by GATA-1 and contain GATA-binding motifs (17) in their promoters and/or enhancers (1). More recently, the direct involvement of GATA-1 in the regulation of the cell cycle has been reported. The latter effect does not depend upon GATA-1 transactivation but is triggered by the repression of genes involved in cell proliferation through occupancy of GATA-1 DNA binding sites (29). Thus, GATA-1 exerts different activities at various steps of the molecular program of erythroid differentiation. Although the underlying molecular mechanisms remain unknown, mice deficient in GATA-1 die in mid-embryonic gestation from severe anemia caused by blockage of erythroid maturation at the proerythroblast stage (32, 34).

Unanswered questions persist: what is the exact role played by Epo for the differentiation of cells toward the erythroid lineage and what are the relevant molecular mechanisms triggered upon binding of Epo to its receptor? Epo acts on committed erythroid progenitors at a stage between the earliest burst-forming unit (BFU-E) and the more mature CFU (CFU-E). Invalidation of either Epo or Epo-R genes induces embryonic lethality at day 13.5 by severe anemia (38). Although these murine models have demonstrated the major importance of Epo and its receptor for the proliferation and survival of erythroid progenitors, the instructive or supportive roles played by Epo-Epo-R interaction for the process of erythroid differentiation and related gene expression remain unsubstantiated (8, 35).

The aim of this paper was to investigate whether a molecular link between Epo signaling and GATA-1 transcriptional activity could be identified. Among the various genes whose expression is induced by Epo in the red blood cell lineage, we first established that transcription of the tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase (TIMP-1) is dependent upon both GATA-1 and Epo in erythroid cells. Moreover, we show that forced expression of both GATA-1 and Epo-R is sufficient to induce expression of the endogenous TIMP-1 gene in the presence of Epo in nonerythroid cells in which TIMP-1 is not normally expressed. We then demonstrate that phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt acts downstream of the Epo-R to phosphorylate directly GATA-1 at a specific serine residue, and that this latter event renders GATA-1 competent for transcription of the TIMP-1 gene. Retrovirus-mediated expression of a mutated form of GATA-1 that cannot be phosphorylated at Ser310 into the GATA-1null G1ER cell line results in delayed kinetics of erythroid differentiation. These results establish the first example of a gene for which the molecular link between Epo signaling and the transcriptional activity of GATA-1 could be identified.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction and mutagenesis.

The human genomic DNA containing the TIMP-1 promoter was kindly provided by I. Clark (2). pTIMP1-luc and pTIMP1M-luc reporter constructs were generated by cloning PCR-amplified DNA fragments of TIMP-1 promoter into pGL3-Basic vector (Promega). The TIMP-1 promoter sequence from 1395 to 1758 (GenBank accession no. HSY09720) was amplified by PCR. The TIMP-1 promoter containing a mutated GATA binding site at positions 1408 to 1411 was obtained by PCR using the mutated 5′ oligonucleotide (Prom3, 5′-ATGTGGGTGATTGGAAAGATTCTGGAGACTTT-3′; the mutated base is underlined); DNA fragments were then cloned into pGL3-Basic vector to generate pTIMP1-luc and pTIMP1M-luc constructs. GATA-1 and GATA-1 mutant cDNA constructs were subcloned into pRSVcDNA3, a modified pcDNA3 expression vector (Invitrogen) in which the Rous sarcoma virus promoter drives the expression of GATA-1 proteins, and into the retrovirus Migr (23). Ser310 mutant GATA-1 constructs were generated by PCR-mediated mutagenesis using oligonucleotides 5′-TTGAATTACGACTCGAAACCGCAAGGCAGCTGGAAAAGGGAAA-3′ (Ser310 to Ala) and 5′-TTGAATTACGACTCGAAACCGCAAGGCATATGGAAAAGGGAAA-3′ (Ser310 to Asp) to generate pGATA1S310/A, MigrGATA1S310/A, and pGATA1S310/D MigrGATA1S310/D. All of the PCR-based constructs were sequenced. Pmyr-Akt and pAkt-DN were given by T. F. Franke (9).

Transfection, luciferase assays, and retroviral infection.

Transient transfection was carried out in 10-cm dishes, and the total amount of DNA in each transfection was kept constant at 5 μg by adding the pUC19 plasmid as backbone. Lipofectamine (Gibco BRL) was used as previously described for COS-7 cells (20). For UT7 or FDC-P1/Epo-R, cells were washed with Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium, seeded at densities of 4 × 106 and 10 × 106 cells/well, respectively, in six-well plates and transfected with Lipofectamine according to manufacturer's instructions. Epo was then added to the culture medium for 24 h. Firefly luciferase activity was measured according to the manufacturer's instructions (Dual Luciferase Assay System; Gibco BRL), and individual transfections were normalized by measurement of Renilla luciferase activity (pRL-TK; Promega). Production of Migr retrovirus and cell infection were performed as described previously (23). Viral titers were normalized after transient production in 293EBNA cells following envelope pseudotyping with vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein G and ultracentrifugation.

Preparation of fetal liver erythroid cells from GATA-1S310/A mice and quantification of TIMP-1 secretion.

A gene knock-in approach was used to generate mice harboring a serine-to-alanine replacement at residue 310 of GATA-1 (GATA-1S310/A; H. M. Rooke and S. H. Orkin, unpublished). Single-cell suspensions were prepared from fetal livers 14.5 days postcoitum (dpc). Cells expressing B220, Gr1, or CD11b were depleted from the population with the mini-MACS cell separation system and recommended protocol (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Biotin-conjugated anti-mouse B220, Gr1, and CD11b antibodies (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA) were used in conjunction with the antibiotin microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Cells from embryos 14.5 dpc were processed independently and were cultured at 106 cells/ml in 2 ml serum-free medium (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancover, British Columbia, Canada), and supernatant was harvested after 24 and 48 h of culture for analysis of TIMP-1 expression. TIMP-1 secretion was quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) according to the manufacturer's instructions (TIMP-1, biotrak ELISA, 96 wells; Amersham Biosciences). Aminophenylmercuric acetate (APMA) treatment was performed to disrupt the TIMP-1/matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) complex and allow the quantification of total TIMP-1.

Preparation of nuclear extracts and oligonucleotide pull-down.

For nuclear extract preparation, cells were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated for 10 min at 4°C in buffer A (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.6, 3 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 5% glycerol, 0.5% NP-40) containing phosphotyrosine phosphatase inhibitors (1 mM Na2VO4), phosphoserine/threonine phosphatase inhibitors (20 mM NaF, 1 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 25 mM β-glycerophosphate), and proteinase inhibitors. After centrifugation, nuclear pellets were resuspended in buffer A containing 300 mM KCl. For oligonucleotide pull-down assays, GATA-1-containing complexes were precipitated from nuclear extracts by addition of 1 μg double-strand biotin-labeled oligonucleotide at 4°C for 1 h (GATA-1 binding sequence of the Epo-R promoter, 5′-262GCCAGGCACTTATCTCTACCCAGGC286-3′; GenBank reference no. HUMEPR; the GATA sequence is underlined). For control experiments, an oligonucleotide bearing a mutated GATA binding site was utilized (5′-262GCCAGGCACTTATTTCTACCCAGGC286-3′; the mutated sequence is underlined). DNA-protein complexes were then pelleted using streptavidin beads (Amersham Biosciences). Beads were then washed three times with lysis buffer and resuspended in 1× Laemmli buffer.

ChIP assay.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed following a modification of the procedure described previously (30). Briefly, protein and DNA were cross-linked in 1× PBS, 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at 4°C. Glycine (125 mM) was then added for 5 min, and after three washes in cold 1× PBS containing a cocktail of protease inhibitors, nuclei from 2 × 107 cells were lysed in 500 μl of 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 5 mM EDTA, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and protease inhibitors. Soluble chromatin was obtained after sonification (seven pulses of 10 s each) and centrifugation. Immunoprecipitation was performed as described previously (30) with TIMP-1 PCR oligonucleotides (forward primer, 5′-TCAGACATACAAAACAAGGGA-3′; reverse primer, 5′-CGTCAGTCACTATTCCTTCCA-3′). The amplified fragment is 222 bp long and corresponds to coordinates 1288 to 1499 of GenBank entry HSY09720.

Western blot analysis.

Samples were subjected to 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher & Schuell). Filters were then blocked overnight in 5% skim milk-Tris-buffered saline (TBS)-0.05% Tween 20 and incubated with either anti-GATA-1 rat monoclonal antibody N6 (Santa Cruz [1:1,000]), or anti-phospho-Akt substrate rabbit monoclonal antibody (New England Biolabs, Cambridge, MA; catalog no. 9611S [1:1,000]) or anti-TIMP-1 antibody (Oncogene catalog no. IM32L [1:100]). Membranes were washed four times in TBS-Tween 20 and incubated for 1 h with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (anti-rat sc-2006 from Santa Cruz [1:5,000], anti-rabbit 7071-1 from New England Biolabs, Cambridge, MA [1:8,000]; anti-goat 305-035-006 from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories [1:5,000]; and anti-mouse antibody from Amersham Biosciences).

Kinase assay.

Starved UT7 cells (10 × 106 cells per point) were stimulated for 10 min or not with Epo (10 U/ml). Nuclear extracts were then prepared and GATA-1-containing complexes were precipitated as previously described. After precipitation, proteins were incubated with or without a recombinant activated Akt (rAkt; Upstate catalog no. 14-276). Proteins were then resolved by SDS-PAGE, and blots were hybridized with anti-phospho-Akt substrate antibodies (anti-PS-Akt), stripped, and reprobed with anti-GATA-1 antibodies.

RESULTS

Erythropoietin induces transcription of the endogenous TIMP-1 gene in nonerythroid cells in the presence of ectopically expressed GATA-1 and Epo-R. TIMP-1 presents the particularity of being induced during erythroid differentiation (14) while acting, conversely, as a costimulator of erythroid differentiation: hence its other name, erythroid potentiating activity (EPA) (6, 11). Since we recently observed that the TIMP-1 gene is induced by Epo in a time- and dose-dependent manner (14), we first asked whether Epo is central to the reciprocal link between Timp-1 and erythroid differentiation. We analyzed TIMP-1null mice, whose hematopoiesis had not been previously examined. Although blood cell counts and subtype distribution were not significantly different from those of wild-type control mice, bone marrow cellularity was decreased by approximately 50% without changes in subtype composition. The observed responses to erythroid stress triggered by injections of Epo or phenylhydrazine were comparable for both TIMP-1null and normal control mice (data not shown). However, addition of TIMP-1 protein to TIMP-1null bone marrow cells cultured in the presence of 0.1 U Epo doubled the number of BFU-Es (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). This synergistic effect was not observed at higher Epo concentrations (1 U), and absence of Epo completely prevented erythroid colony formation (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). We ruled out that this result was caused by the known protease inhibitory activity of TIMP-1, by verifying that TIMP-1 did not stabilize Epo in the culture medium at various concentrations (data not shown). These data suggest a mutual relationship between TIMP-1 and Epo at the late stages of erythropoiesis and prompted us to focus on the TIMP-1 gene as a possible model of a putative Epo/GATA-1 cross talk.

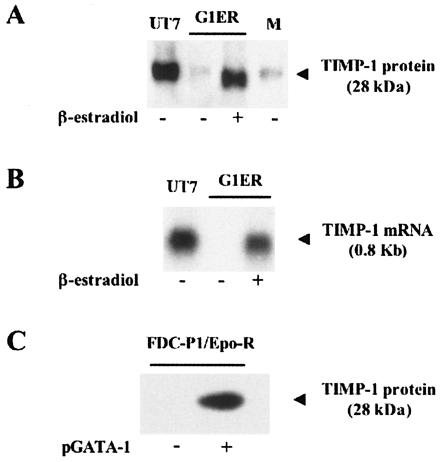

To assess whether expression of the TIMP-1 gene is dependent upon GATA-1 activity in erythroid cells, we turned to the G1ER cell line model. G1ER cells derive from GATA-1null embryonic stem cells. These cells are also Epo dependent for growth and survival and express a GATA-1/estradiol receptor fusion protein whose functionality is dependent on β-estradiol (37). In the presence of Epo and in the absence of β-estradiol, we found that G1ER cells do not secrete detectable amounts of TIMP-1 (Fig. 1A). However, in the presence of both Epo and β-estradiol, secretion of the TIMP-1 protein is strongly induced (Fig. 1A). This GATA-1-dependent secretion of TIMP-1 was further investigated by Northern blot analysis, which showed that TIMP-1 mRNA levels correlated with GATA-1 induction (Fig. 1B). These findings suggest that GATA-1 activity is required for expression of the TIMP-1 gene in erythroid cells.

FIG. 1.

Expression of the endogenous TIMP-1 gene depends upon GATA-1 expression in both erythroid and nonerythroid cells. (A) The erythroid cell line G1ER, grown in the presence of Epo, was stimulated or not by β-estradiol. TIMP-1 secretion was quantified from cell supernatants by Western blot analysis with a polyclonal anti-TIMP-1 antibody. The human erythroleukemia cell line UT7, induced by Epo for 48 h, was used as the positive control. The basal level of TIMP-1 present in the cell culture medium used for the G1ER cells was also quantified (lane M). Equal amounts of protein extracted from 2 × 105 cells were loaded in each well. Protein molecular weight markers (New England Biolabs, Cambridge, MA) were used as size controls. (B) Northern blot analysis of TIMP-1 mRNA expression in G1ER cells, grown in the presence of Epo, and stimulated or not by β-estradiol. UT7 cells induced by Epo for 48 h served as the positive control. Equal amounts of RNA extracted from 2 × 105 cells were loaded in each well. Evenness of RNA loading was established by examination of ribosomic RNAs. DNA ladder provided size identification. (C) Endogenous secretion of TIMP-1 in the nonerythroid cell line FDC-P1/Epo-R grown with Epo, in the presence or absence of transfected GATA-1-expressing plasmid (pGATA-1). Cell supernatants (from 2 × 105 cells per sample) were harvested, concentrated, and resolved by Western blot analysis using an anti-TIMP-1 polyclonal antibody. In the absence of Epo, no TIMP-1 secretion was detected with or without GATA-1 expression (data not shown). Protein molecular weight markers (New England Biolabs, Cambridge, MA) were used as size controls.

We then set out to investigate whether expression of the endogenous TIMP-1 gene could be induced by GATA-1 in an Epo-dependent manner in a myeloid but not erythroid cell line in which the endogenous TIMP-1 is not normally expressed. To this end, we made use of the FDC-P1 cell line, which constitutively expresses Epo-R after stable transfection of the encoding gene and is referred to as FDC-P1/EpoR (10). FDC-P1/EpoR cells do not express a detectable amount of TIMP-1, even in the presence of Epo. A plasmid expressing GATA-1 (pGATA-1) was transiently transfected into FDC-P1/EpoR cells. Cells were serum starved before being exposed or not to Epo. We found that TIMP-1 expression was induced only in the cells transfected with the GATA-1 vector and exposed to Epo (Fig. 1C). Concurrent induction of other erythroid-specific genes that include the endogenous globin genes was not observed (data not shown). Together, these data indicate that the TIMP-1 gene meets the various criteria set forth in our study to probe the molecular events that may link Epo-related signaling and GATA-1-mediated transcription.

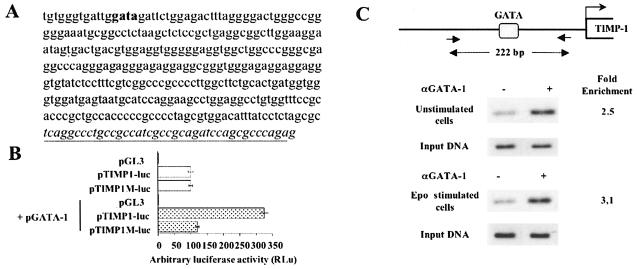

GATA-1 mediates transcriptional regulation of the TIMP-1 through a bona fide GATA binding site.

We then set out to investigate the molecular mechanism by which GATA-1 controls the expression of the TIMP-1 gene. We first determined the minimal GATA-1-dependent TIMP-1 promoter and found it to be located between coordinates 1395 and 1758 (GenBank accession no. HSY09720) (Fig. 2A). Sequence analysis of this minimal promoter revealed a unique putative GATA consensus sequence (5′-GGATTGGATAGATT-3′; the GATA sequence is underlined) at positions 1408 to 1411. To evaluate the importance of this sequence for GATA-1 transactivation of the minimal TIMP-1 promoter, we used a luciferase reporter construct in which this GATA sequence was either intact (pTIMP1-luc) or inactivated by mutation (pTIMP1M-luc). Both pTIMP1-luc and pTIMP1M-luc constructs had similar activity in COS-7 cells in the absence of GATA-1 expression, whereas only the pTIMP1-luc vector could be transactivated by GATA-1 (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, electrophoresis mobility shift assays confirmed the specific binding capacity of this DNA sequence for GATA-1 protein (data not shown). To establish the physical binding of GATA-1 in vivo to the GATA site present in the endogenous TIMP-1 promoter, we performed a ChIP assay in UT7 cells unstimulated or stimulated for 30 min with Epo. After chromatin cross-linking with formaldehyde, the DNA-GATA-1 complexes were immunoprecipitated with an antiserum against GATA-1. In three independent experiments, the immunoprecipitated chromatin was enriched for TIMP-1 promoter sequences by two- to threefold (Fig. 2C). Together with the transfection experiments, these results support a model where GATA-1 activates TIMP-1 gene expression by direct association with its promoter.

FIG. 2.

Transactivation of both endogenous and transfected TIMP-1 promoters requires GATA-1 expression together with PI3K/Akt signaling. (A) TIMP-1 promoter sequence (coordinates 1395 to 1758, GenBank accession no. HSY09720). The GATA consensus sequence is indicated in bold, and the beginning of exon 1 is underlined. (B) Dependence of the TIMP-1 promoter on GATA-1 transactivation. The human TIMP-1 promoter was subcloned in the luciferase reporter vector pGL3 (pTIMP1-luc). The GATA binding sequence at positions 1408 to 1411 (GenBank accession no. HSY09720) was inactivated by mutagenesis to yield the pTIMP1M-luc construct. These two promoter constructs were transiently transfected in the nonerythroid cell line COS-7, with or without cotransfection with the GATA-1 expression vector (pGATA-1). pUC19 plasmid DNA was used to adjust the total amount of transfected DNA in each cotransfection. Luciferase activity was determined 24 h after transfection. Data are expressed as arbitrary luciferase activity (RLu). Results are the means ± standard error of at least three independent experiments. (C) ChIP of GATA-1 bound to the TIMP-1 promoter. UT7 cells were either unstimulated or stimulated with Epo for 30 min. UT7 cell lysates were mock immunoprecipitated (no antibody lanes) or immunoprecipited (αGATA-1 lanes) with the N6 anti-GATA-1 antibody. DNA recovered by immunoprecipitation was amplified with specific PCR primers, as indicated in Materials and Methods, to yield a specific 222-bp DNA fragment. Enrichment in TIMP-1 promoter sequences was quantified by NIH Image (version 1.62) software. As a control, 1/800 of whole-lysate DNA (Input DNA) was amplified in parallel under the same conditions and with the same PCR primers.

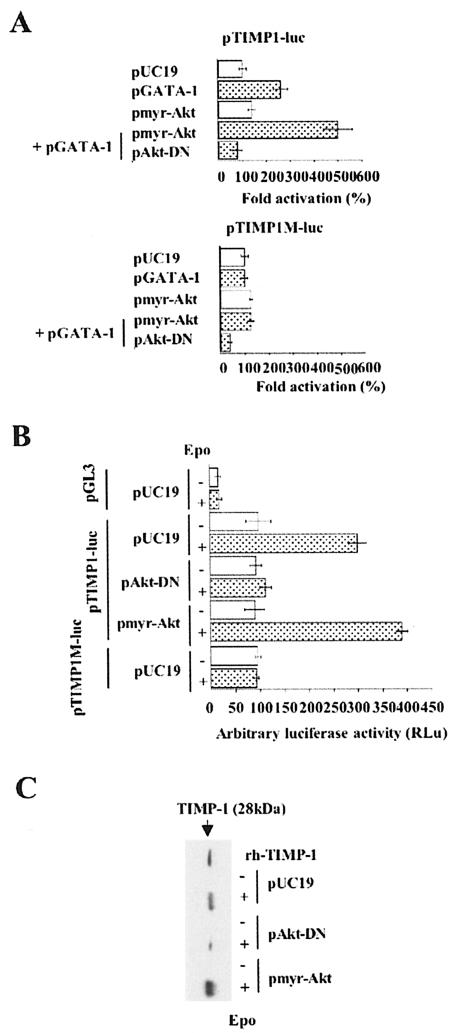

The Akt kinase mediates signaling between the Epo receptor and GATA-1.

We then set out to investigate how GATA-1 activation of the TIMP-1 gene is connected to Epo signaling. We first focused on PI3K/Akt. COS-7 cells were submitted to a triple cotransfection procedure with (i) pTIMP1-luc; (ii) in either the presence or absence of pGATA-1; and (iii) with either a vector encoding a constitutively active form of Akt, pmyr-Akt, or a vector encoding a dominant-negative form of Akt, pAkt-DN (9). Whereas Akt exerted only a small effect on the TIMP-1 promoter, transcription was strongly enhanced when pmyr-Akt and GATA-1 were coexpressed (Fig. 3A). In contrast, luciferase activity decreased to the basal level when GATA-1 was coexpressed with Akt-DN (Fig. 3A). As a control, the TIMP-1 promoter that lacks the GATA-1 binding site (pTIMP1M-luc) was not influenced by any of the above conditions. To extend these results to erythroid cells, we made use of the Epo-dependent erythroleukemia cell line UT7 in which we quantified the transcription of reporter genes, with or without Epo stimulation. In the absence of Epo, we found that both pTIMP-luc and pTIMP1M-luc are transcribed at similar levels (Fig. 3B). TIMP-1 promoter activity and endogenous TIMP-1 secretion were induced by Epo stimulation (Fig. 3B and C). In contrast, the TIMP-1 promoter in which the GATA-1 DNA binding site is mutated had the same activity with or without Epo stimulation. Cotransfection with pAkt-DN inhibited Epo-mediated activation of the TIMP-1 promoter and endogenous secretion of this protein, thus indicating that Akt is involved in the activation of the TIMP-1 promoter. We then asked whether the regulation of GATA-1 transcriptional activity by Akt is sufficient to induce TIMP-1 expression in the erythroid cell line UT7, even in the absence of Epo stimulation. Under serum starvation, expression of the constitutively active form of Akt, pmyr-Akt, failed to activate either the endogenous or a transfected TIMP-1 promoter (Fig. 3B, line 7). Thus, the Akt pathway is not sufficient to induce TIMP-1 gene expression in starved UT7 cells, and we now have evidence that both MEK/ERK and Akt pathways are necessary and sufficient to activate TIMP-1 gene expression under conditions of complete serum starvation (data not shown). We also found that endogenous GATA-1 was expressed at similar levels in the presence or absence of Epo, as assessed by Western blot analysis, and that the DNA binding activity of GATA-1 was not modified in the presence of Epo, as assessed by EMSAs (data not shown). Together, these data indicate that Akt acts downstream of the Epo-R to regulate GATA-1 activity. These studies led us the next stage of investigation: whether GATA-1 is a direct target of Akt phosphorylation.

FIG. 3.

Epo-dependent TIMP-1 gene expression requires the presence of GATA-1 and AKT signaling in both erythroid and nonerythroid cells. (A) Transcriptional effects of GATA-1 on a transfected TIMP-1 promoter in the context of forced activation or inhibition of the PI3K/Akt pathway in COS-7 cells were evaluated by cotransfection of plasmids expressing GATA-1 (pGATA-1) and either constitutively active (pmyr-Akt) or dominant-negative (pAkt-DN) forms of Akt together with the pTIMP1-luc (top) or pTIMP1M-luc (bottom) reporter plasmids. Data are expressed as fold induction above the control pTIMP1-luc or pTIMP1M-luc plasmids alone. Results are the means ± standard error of at least three independent experiments. (B) The experiments described in Fig. 3A were also performed in the erythroleukemic cell line UT7. After transfection of UT7 and culture in Epo for 24 h, cells were serum starved for 18 h and then stimulated or not by Epo (2 U/ml) during 48 h. Results are the means ± standard error of at least three independent experiments. (C) In parallel to transient transfection studies (Fig. 3B), endogenous TIMP-1 protein secretionwas evaluated by Western blot analysis of UT7 cell supernatants using a polyclonal anti-TIMP-1 antibody. Recombinant human TIMP-1 (rh-TIMP-1) was used as a control (10 ng).

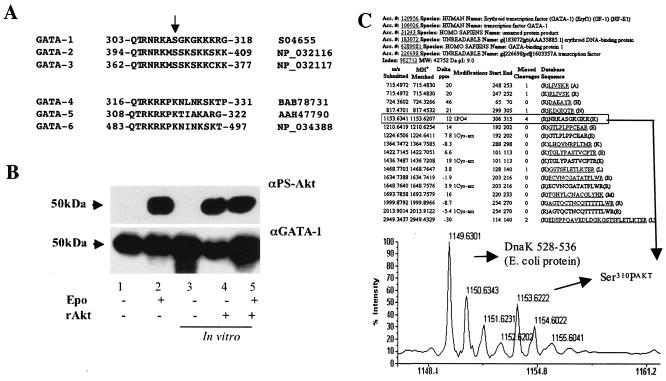

Akt activates GATA-1 posttranslationally by phosphorylation at serine 310.

By examining peptidic sequences of several proteins of the GATA family, we identified a conserved domain identical to the Akt-substrate consensus sequence RXRXXS/T (Fig. 4A). Within this consensus sequence, we identified a specific serine residue potentially phosphorylatable by Akt in all of the known mammalian GATA proteins expressed in hematopoietic cells: GATA-1 (Ser310), GATA-2 (Ser402), and GATA-3 (Ser369). In contrast, this residue is not present in the mammalian GATA-4, -5, and -6 proteins, which are not expressed in hematopoietic tissues (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

Akt phosphorylates GATA-1 on Ser310, and this phosphorylation is critical for GATA-1-mediated transactivation of the TIMP-1 promoter. (A) Comparison of primary amino acid sequences of mammalian GATA family members. GATA members expressed in hematopoietic cells have a serine residue (arrow) within an Akt consensus sequence (top), whereas GATA members not expressed in hematopoietic cells do not (bottom). The NCBI database protein accession numbers are indicated (right). (B) UT7 cells that have been starved for 18 h were incubated with or without Epo for 10 min. GATA-1 oligonucleotide pull-down of nuclear extracts was resolved by SDS-PAGE either directly (lanes 1 and 2) or after incubation in vitro with functional recombinant Akt protein (rAkt) (lanes 4 and 5). Blots were subsequently hybridized with an anti-phospho-Akt substrate (αPS-Akt) antibody (top), then dehybridized and reprobed with an anti-GATA-1 (αGATA-1) antibody (bottom). (C) Evidence of Akt-mediated Ser310 phosphorylation of GATA-1 by mass spectrometry. Recombinant GST-GATA-1 protein was incubated or not with Akt before separation by SDS-PAGE. Protein bands with an apparent molecular mass of 68 kDa were excised and digested. Resulting peptides were analyzed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. Peptide 306-315 was detected only in the Akt-phosphorylated sample, and its mass is compatible with the presence of a phosphate residue at Ser310. Notably, it was the only detected peptide whose mass is compatible with the addition of a phosphate residue.

To determine whether GATA-1 is a substrate of Akt phosphorylation in vivo, we made use of an antibody that specifically recognizes phosphorylated (Ser/Thr) residues found within the putative Akt-substrate consensus sequence RXRXXS/T (PS-Akt Ab). Because immunoglobulin heavy chains (molecular mass, ∼50 kDa) used for immunoprecipitation and GATA-1 (molecular mass, ∼50 kDa) comigrate in SDS-PAGE, making Western blot analysis of immunoprecipitation experiments impossible, we utilized a GATA-1 oligonucleotide “pull-down” strategy (20). GATA-1 was precipitated from the nuclear fraction of either starved or Epo-induced UT7 cells, and Akt-phosphorylated GATA-1 was only revealed in the preparation from Epo-stimulated cells (Fig. 4B).

We then asked two questions: (i) do the phosphorylated and the nonphosphorylated fractions of GATA-1 bind equally well to their DNA target, as assessed by this oligonucleotide “pull-down” experiment, and (ii) can we quantify the fraction of the molecules of GATA-1 phosphorylated by Akt in vivo? To answer these questions, we compared the intensity of the phosphorylated GATA-1 product revealed by the PS-Akt Ab in the aforementioned lane of the immunoblot to that of the equivalent product obtained with the other half of the preparations after they were incubated in vitro to saturation with recombinant activated Akt (rAkt). As the three observed products have the same intensity (Fig. 4B), we conclude that (i) both phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated forms of GATA-1 bind equally well to their DNA target and (ii) in vivo phosphorylation of GATA-1 in Epo-stimulated UT7 cells reaches saturation. The first point was corroborated by reprobing the immunoblot with an anti-GATA-1 Ab (Fig. 4B) (data not shown).

To verify that Ser310 of GATA-1 is a bona fide substrate of Akt, we incubated a glutathione S-transferase (GST)-GATA-1 fusion protein expressed in Escherichia coli with recombinant active Akt. After protease digestion, the resulting peptides were analyzed by mass spectrometry, revealing a peptide whose mass was consistent with the presence of a phosphate residue at Ser310 (Fig. 4C).

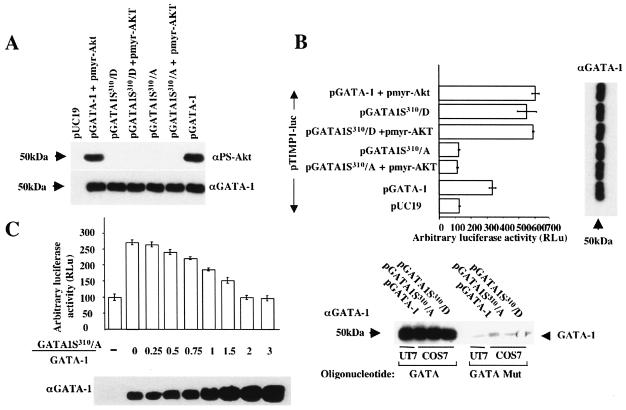

We then investigated whether Ser310 phosphorylation is important for GATA-1 activity. To probe this question, we have designed vectors that express different GATA-1 mutants. In the first GATA-1 mutant, Ser310 was substituted for by alanine (pGATA1S310/A) to destroy the possibility of phosphorylation at this site. Immunophosphorylation studies confirmed that the anti-PS-Akt Ab does not recognize the GATA-1S310/A protein mutant in presence or absence of a transfected vector expressing the constitutively activated form of Akt (Fig. 5A). In the second GATA-1 mutant, Ser310 was substituted for by aspartic acid (pGATA1S310/D). The latter modification is believed to mimic a state of constitutive phosphorylation by providing an additional negative charge. As expected, this mutant was not recognized either by the anti-PS-Akt Ab (Fig. 5A). The transcriptional activity of both mutants was evaluated by cotransfection in COS-7 cells together with pTIMP1-luc. Equivalency of expression of the various GATA-1 proteins was monitored by Western blot analysis with an anti-GATA-1 antibody (Fig. 5A, bottom). When the pGATA1S310/D vector was utilized, the TIMP-1 promoter was transactivated at the same level as that obtained by cotransfection of wild-type pGATA-1 together with pmyr-Akt. In contrast, ineffective transactivation was observed when the pGATA1S310/A vector was cotransfected. Furthermore, adding or not adding pmyr-Akt in the cotransfection mixture with either pGATA1S310/D or pGATA1S310/A did not cause any change in luciferase levels, thereby indicating that the sole target of Akt relevant to TIMP-1 promoter activation is Ser310 of GATA-1 (Fig. 5B). Dependency upon the exact GATA binding sequence was verified by an oligonucleotide “pull-down” assay performed with an oligonucleotide bearing either the wild-type GATA or a mutated sequence (one-point mutation) after transfection of COS-7 cells with pGATA-1, pGATA1S310/A, or pGATA1S310/D plasmids (Fig. 5B, bottom panel).

FIG. 5.

The mutant GATA-1 S310/A is unphosphorylatable by AKT and is unable to transactivate the TIMP-1 promoter. (A) GATA-1 phosphorylation and concurrent expression levels were evaluated by Western blot analysis with anti-phospho-Akt substrate (αPS-Akt) (top) and anti-GATA-1 (αGATA-1) (bottom) antibodies, respectively, after transient transfection of expression plasmids into COS-7. The various GATA-1 mutants tested include a substitution for serine 310 by alanine (pGATA1S310/A), making it unphosphorylatable, and a substitution for serine 310 by aspartic acid (pGATA1S310/D), thereby mimicking constitutive phosphorylation. Transfection experiments and data treatment are the same as in Fig. 3A. (B) To evaluate the importance of GATA-1 Ser310 phosphorylation in vivo, the GATA-1 mutant-expressing plasmids were tested for their capacity at transactivating a cotransfected TIMP-1 promoter (pTIMP1-luc) in COS-7 cells (top left). Transfection experiments and data treatment are the same as in Fig. 3A. Concurrent GATA-1 expression level was estimated for each data point by Western blot analysis of transfected COS-7 cells (top right). To control for GATA binding specificity of the different GATA-1 mutants, we performed an oligonucleotide pull-down assay with an oligonucleotide bearing a known GATA binding site (from the Epo-R promoter) or a single-point-mutated sequence of the same oligonucleotide, which does not bind GATA-1. Samples were analyzed by Western blotting with an anti-GATA-1 (αGATA-1) antibody (bottom). (C) To quantify the dominant-negative effect exerted by the GATA-1S310/A mutant on wild-type GATA-1, COS-7 cells were cotransfected with a constant amount of pGATA-1 and pTIMP1-luc plasmids together with variable quantities of pGATA1S310/A. GATA-1 protein levels obtained with both pGATA1S310/A and pGATA-1 expression plasmids were first standardized (data not shown). The ratio of GATA-1S310/A over total GATA-1 protein expression (GATA-1S310/A plus GATA-1) was quantified by Western blot analysis with an anti-GATA-1 (αGATA-1) antibody. Transfection experiments and data treatment are the same as in Fig. 3A.

To address specificity and stoichiometry of the inhibitory effect, a competition study was performed (Fig. 5C). We observed that a 2/1 ratio of GATA-1S310/A versus GATA-1 proteins or greater was capable of achieving complete inhibition of the transactivation of the TIMP-1 promoter.

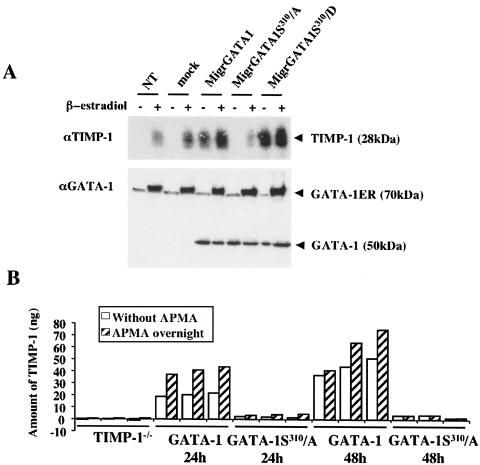

Finally, we turned again to the G1ER cell line to determine whether the Ser310-specific GATA-1 phosphorylation by an Epo-dependent Akt signaling pathway is necessary to induce expression of the endogenous TIMP-1 gene in an erythroid cell. To this aim, the retroviral vector Migr was utilized to express either wild-type GATA-1 (MigrGATA-1) or GATA-1 mutants (MigrGATA1S310/D and MigrGATA1S310/A). G1ER cells were independently transduced with each retroviral vector at identical multiplicities of infection and in the absence of β-estradiol. After 1 day, half of each culture was induced with β-estradiol for 2 days, while the other half was maintained without β-estradiol induction. On the third day, infected cells were tested for green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression, indicating an efficacy of transduction of approximately 60%. TIMP-1 and GATA-1 protein expression was then evaluated by Western blot analysis using specific antibodies (Fig. 6A). In the absence of β-estradiol induction, endogenous TIMP-1 secretion was only observed when cells had been transduced with either MigrGATA-1 or MigrGATA1S310/D retroviruses, with a stronger TIMP-1 level achieved with MigrGATA1S310/D (Fig. 6A). In contrast, endogenous TIMP-1 secretion was undetectable after transduction of G1ER cells with the MigrGATA1S310/A retrovirus (Fig. 6A).

FIG. 6.

Secretion of endogenous TIMP-1 in G1ER cells after retrovirus-mediated expression of GATA-1 or its variants and in erythroid cells of GATA-1S310/A knock-in transgenic mice. (A) G1ER cells, grown in the presence of Epo, were transduced with either MigrGATA-1, MigrGATA1S310/A, or MigrGATA1S310/D retroviral vectors. One day after infection, cells were incubated in the presence or absence of β-estradiol. Three days postinfection, cell supernatants were harvested for Western blot analysis with anti-TIMP-1 (αTMP-1) polyclonal antibodies (top). Concurrently, nuclear extracts were prepared for quantification of GATA-1 expression by Western blot analysis with an anti-GATA-1 (αGATA-1) antibody (bottom). GATA-1ER (70 kDa) corresponded to the GATA-1/estradiol receptor fusion protein whose functionality and GATA binding capacity are dependent upon β-estradiol binding. (B) Expression of TIMP-1 by fetal liver erythroid cell was decreased in GATA-1S310/A knock-in mice. Fetal liver cells from 14.5-dpc embryos, only expressing the GATA-1S310/A allele, were enriched for erythroid cells and cultured for 24 and 48 h. TIMP-1 secreted by these cells was quantified by ELISA before (white bars) and after APMA treatment (hatched bars). Livers from three mice from each genotype were analyzed separately; TIMP1−/− knockout mice were used as a negative control.

From these experiments, we can conclude that Ser310 is the sole site of Epo-dependent Akt-mediated phosphorylation involved in the posttranslational activation of GATA-1 with respect to its transactivating properties upon the TIMP-1 promoter, whether in erythroid or nonerythroid cells.

Profound impairment of TIMP-1 secretion by erythroid cells from knock-in transgenic mice only expressing the GATA-1S310/A mutant.

We next investigated TIMP-1 expression in erythroid cells from mice harboring a serine-to-alanine replacement at residue 310 of GATA-1 (H. M. Rooke and S. H. Orkin, unpublished). Further phenotypic analysis of this mouse will be described in detail elsewhere. We predicted that nonerythroid cells from these mice, such as macrophages or stromal cells, would express TIMP-1 but that GATA-1 phosphorylation would be essential for normal TIMP-1 expression in the erythroid compartment. To generate a highly purified population of erythroid cells, fetal liver cells of embryos 14.5 dpc genotyped for the presence of the GATA-1S310/A mutant allele and the absence of the wild-type GATA-1 gene, were depleted of nonerythroid cells by using antibodies directed to B220, Gr1, and Mac1 (see Materials and Methods). Cells were maintained in serum-free conditions, and supernatant was harvested after 24 and 48 h of culture. Half of each supernatant was treated with APMA to disrupt the interaction of TIMP-1 with MMP-9 and increase TIMP-1 available for antibody assay. Levels of TIMP-1 protein in the supernatants before and after treatment with APMA were determined by ELISA (Fig. 6B). The amount of TIMP-1 protein detected in the supernatants from cultured fetal liver erythroid cells from the GATA-1S310/A mice was greatly reduced compared with that in the wild type at both 24 and 48 h (Fig. 6B). This result indicates that phosphorylation of GATA-1 at serine 310 is critical for the in vivo induction of TIMP-1 expression in response to Epo signaling.

Dependency upon GATA-1 Ser310 phosphorylation may define a subset of erythroid genes.

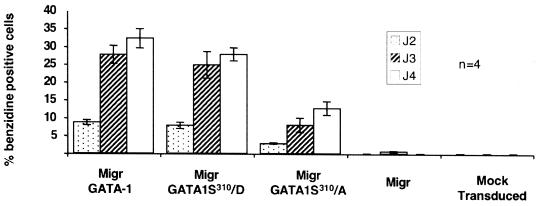

While we have now established the importance of the Epo/Epo-R-Akt-GATA-1S310 molecular chain of events for the transcriptional regulation of the TIMP-1 gene, what is the relevance of these mechanisms for other genes associated with erythroid differentiation? To answer this question, we evaluated the overall erythroid differentiation capacity of G1ER cells after retrovirus-mediated expression of the different GATA-1 mutants. A time course of hemoglobinization, as assessed by measuring the percentage of benzidine-positive cells, was performed as a function of time after infection. MigrGATA1S310/A did not completely block cell hemoglobinization, indicating that the phophorylation at Ser310 is not absolutely required for erythroid differentiation. However, the rate of hemoglobinization was reduced by approximately 50% comparatively to MigrGATA-1 and MigrGATA1S310/D (Fig. 7). Northern blot analysis of murine βmaj-globin RNA revealed a concurrent decrease in gene expression (data not shown). This decrease in the rate of hemoglobinization could be the result of either a down regulation of the globin genes and/or those involved in heme biosynthesis (direct effect) or the consequence of the inhibition of the TIMP-1 gene or others yet unidentified (indirect effect). We have tested several minimal promoters of erythroid-specific genes by luciferase assay in the transiently transfected COS-7 cells for their capacity to be transactivated by the GATA-1S310/A mutant in the presence of Epo. Whereas all the erythroid promoters tested were transactivated by wild-type GATA-1, the Epo-R minimal erythroid promoter (20) was not transactivated by the GATA-1S310/A mutant, in contrast to the glycophorin B (28) or Gfi-1B minimal erythroid promoters (13), which appear not to require GATA-1 phosphorylation to be transactivated (data not shown).

FIG. 7.

Rate of hemoglobinization of G1ER cells after retrovirus-mediated expression of GATA-1 and its variants. G1ER cells were transduced with a retroviral vector expressing either wild-type or mutated forms of GATA-1, together with enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP). Transduction efficiency was approximately 80%, as assessed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis for EGFP expression. Hemoglobinization was assessed at various time points by benzidine staining, and the percentage of benzidine-positive cells was scored. Results are the means ± standard error of at least four independent experiments.

Altogether, these data suggest the existence of two subsets of genes transactivated by GATA-1 in erythroid cells: one for which Akt-mediated GATA-1 phosphorylation is not absolutely required (major late erythroid genes) and another that is completely GATA-1 phosphorylation dependent and of which TIMP-1 is the first member. Although the identified pathway appears dispensable for the first subset, these genes may nevertheless partially depend, directly or indirectly, upon it, as the decreased hemoglobinization suggests.

DISCUSSION

The TIMP-1 gene represents an atypical case of transcription in erythroid cells that led us to uncover the first evidence of molecular coupling between Epo-R, intracellular signaling, and GATA-1-mediated transactivation. Activation of specific Epo-dependent intracellular pathways both in erythroid and, surprisingly, nonerythroid cells was sufficient to induce the transcription of the endogenous TIMP-1 gene. The fact that endogenous TIMP-1 gene expression was inducible in nonerythroid cells indicates a direct effect of the identified pathways converging on GATA-1-mediated activation of transcription rather than a mere indirect consequence of erythroid differentiation. Together, these results fill a gap in knowledge as to the role played by Epo on the induction of gene expression in the red blood cell lineage.

Our data demonstrate that Epo-Epo-R interaction triggers the phosphorylation of GATA-1 to saturation at Ser310 by the PI3K/Akt pathway in both erythroid and nonerythroid cells. GATA-1 phosphorylated on Ser310, in turn, activates the transcription of both the endogenous and a transiently transfected TIMP-1 promoter through a GATA-1 binding site. The requirement of the GATA-1 phosphorylation for the activation of the TIMP-1 gene in nonerythroid cells indicates that phosphorylation may modulate association of GATA-1 Ser310 with other proteins or that another type of control mechanism may be operating. Previous biochemical studies have shown that GATA-1 is phosphorylated at six serine residues in nondifferentiated murine erythroleukemia cells. Interestingly, it is the 7th serine residue, Ser310, identified in this study as a specific target of Akt, which becomes phosphorylated after induction of terminal erythroid differentiation by dimethyl sulfoxide (5). Interestingly, no transcriptional effect of the Ser310 phosphorylation of GATA-1 was obtained using synthetic promoters containing one or multiple GATA binding sites (5), while we reproducibly observed a major effect of GATA-1 Ser310 phosphorylation for the transcriptional activity of the TIMP-1 promoter. Such discrepancy between artificial and natural promoters has already been reported for numerous transcriptional activators (18).

Importantly, the relevance of these results was corroborated in vivo by the analysis of knock-in transgenic mice homozygous for the GATA-1S310/A gene, which encodes the GATA-1 mutant that cannot be phosphorylated at Ser310. We found that TIMP-1 secretion is profoundly decreased in erythroid cells from 14.5-dpc fetal livers of these mutant mice.

We have also shown that the minimal erythroid glycophorin B and Gfi-1B promoters are not dependent upon GATA-1 phosphorylation. These observations indicate that GATA-1 Ser310 phosphorylation is not essential for overall erythroid gene expression but point to a specific pathway that regulates a subset of erythroid genes. Classifying erythroid genes for their dependency upon GATA-1 Ser310 phosphorylation will be crucial for our understanding of the physiological impact of Epo-mediated Akt phosphorylation. The phosphorylation-dependent activation of GATA-1 may also apply to nonhematopoietic members of the GATA family. For instance, GATA-4 can be phosphorylated by ERK-2 at Ser105, and this triggers an increase in the proliferation of cardiomyocytes (19). GATA-4 can also be phosphorylated on a different serine residue by the glycogen synthase kinase 3β, itself inhibited by the PI3K/Akt pathway, resulting in increased contractility of the myocardium (25).

TIMP-1 is expressed by a variety of cell types and is present in most tissues and body fluids. In 1980, an EPA was discovered (11, 26) and the cDNA encoding the corresponding protein was cloned. Subsequent studies found that its main apparent property was that of an inhibitor of metalloproteinases, such as MMP-9, hence the given name of TIMP-1, for tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 (6). The connection between TIMP-1 and erythroid differentiation was then largely forgotten. We have reexamined the physiological importance of TIMP-1 in hematopoiesis by comparing TIMP-1null to wild-type mice. Since TIMP-1null mice are viable, indicating some degree of physiological redundancy, perhaps through other TIMP family members, hematopoietic stress and in vitro studies were performed.

Although steady-state and stress erythropoieses appear unimpaired in TIMP-1null mice, a stimulation of erythropoiesis was evidenced in BFU-E assays at low Epo concentrations, reminiscent of the known EPA activity of TIMP-1 (26). The potentializing effect of TIMP-1 on BFU-Es may again occur through MMP-9 inhibition of release of soluble stem cell factor (SCF) (12). Two observations further support this hypothesis. First, KitlSl-d/KitlSl-d (Steel Dickie) or Kitl17H/Kitl17H (Steel17H) mutant mice, which only express the soluble form of SCF, are anemic, and expression of a transmembrane form of SCF reverses this phenotype (16). Second, a transmembrane form of SCF that is cleavable by MMP-9 or an uncleavable transmembrane form of SCF both induce greater erythroid proliferation and cell cycle progression than soluble SCF (15).

An open question is the degree to which the identified mechanisms are unique to the transcriptional regulation of a subgroup of genes in erythroid cells or if they play a key role in the general process of erythroid-specific gene expression. Several lines of evidence suggest that the control of GATA-1 expression level is important to erythroid proliferation, survival, and differentiation: (i) abrogation of GATA-1 expression is lethal during embryogenesis because of apoptosis of mature erythroid cells (27, 34, 36), (ii) overexpression is also lethal by cell cycle interference (7), (iii) down-expression induces several abnormal phenotypes (21, 22, 31), and (iv) acquired mutation in GATA-1 may be a primary event in the megakaryocytic leukemia of children with Down syndrome (4). We have shown here that the posttranslational modification of GATA-1 is necessary to control the gene expression of specialized genes that include the TIMP-1 gene. The mechanism by which GATA-1 Ser310 activates transcription and the explanation for the reduction in hemoglobinization induced by a form of GATA-1 rendered unphosphorylatable at Ser310 are currently unknown. We have tested various hypotheses that include differential GATA-1 stability, DNA affinity, and acetylation levels of the Lys residue near Ser310 between wild-type GATA-1 and the GATA-1S310/A mutant, without conclusive findings, although this site-specific phosphorylation appeared to be required for the DNA-dependent association of GATA-1 with its cofactor FOG-1 by overexpression studies in the HEK 293 cell line (data not shown). GATA-1 protein complexes are specific for individual genes, and the state of GATA-1 Ser310 phosphorylation may have profound repercussions for the associative properties of the protein with consequences on transcriptional regulation of target genes. The impact of GATA-1 Ser310 phosphorylation was analyzed in in vitro differentiation assays of the GATA-1null murine embryonic stem cell line G1ER. The number of differentiated cells infected by MigrGATA1S310/A was severely decreased when compared to the number of MigrGATA1S310/D- or MigrGATA-1-transduced cells. Although the presence of benzidine cells indicates that GATA-1 Ser310 phosphorylation is qualitatively dispensable for terminal differentiation, it is likely to be necessary for the fine control of erythroid cell production or function. Establishing which erythroid genes are dependent upon Akt-mediated GATA-1 phosphorylation for their transcriptional activity will reveal how Epo regulates erythropoiesis through this pathway.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Dominique Dumenil for assistance with virus production and infection, Isabelle Dusanter-Fourt and Veronique Baud for advice on the ChIP assay, and Lamya Haddaoui and Amelia Vernochet for their excellent technical help, as well as the Service Commun de Sequençage de Cochin for DNA sequencing.

This work was supported by the Comité de Paris of the Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer (LNCC; Laboratoire associé no. 8). Z.K. was supported by grants from the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale and from the Fondation Contre la Leucémie. P.L. was supported by NIH grants.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cantor, A. B., and S. H. Orkin. 2002. Transcriptional regulation of erythropoiesis: an affair involving multiple partners. Oncogene 21:3368-3376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark, I. M., A. D. Rowan, D. R. Edwards, T. Bech-Hansen, D. A. Mann, M. J. Bahr, and T. E. Cawston. 1997. Transcriptional activity of the human tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 1 (TIMP-1) gene in fibroblasts involves elements in the promoter, exon 1 and intron 1. Biochem. J. 324:611-617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crispino, J. D. 2005. GATA1 in normal and malignant hematopoiesis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 16:137-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crispino, J. D. 2005. GATA1 mutations in Down Syndrome: implications for biology and diagnosis of children with transient myeloproliferative disorder and acute megakaryoblastic leukemia. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 44:40-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crossley, M., and S. H. Orkin. 1994. Phosphorylation of the erythroid transcription factor GATA-1. J. Biol. Chem. 269:16589-16596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Docherty, A. J., A. Lyons, B. J. Smith, E. M. Wright, P. E. Stephens, T. J. Harris, G. Murphy, and J. J. Reynolds. 1985. Sequence of human tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases and its identity to erythroid-potentiating activity. Nature 318:66-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dubart, A., P. H. Romeo, W. Vainchenker, and D. Dumenil. 1996. Constitutive expression of GATA-1 interferes with the cell-cycle regulation. Blood 87:3711-3721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fichelson, S., S. Chretien, M. Rokicka-Piotrowicz, S. Bouhanik, S. Gisselbrecht, P. Mayeux, and C. Lacombe. 1999. Tyrosine residues of the erythropoietin receptor are dispensable for erythroid differentiation of human CD34+ progenitors. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 256:685-691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franke, T. F., S. I. Yang, T. O. Chan, K. Datta, A. Kazlauskas, D. K. Morrison, D. R. Kaplan, and P. N. Tsichlis. 1995. The protein kinase encoded by the Akt proto-oncogene is a target of the PDGF-activated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Cell 81:727-736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gobert, S., S. Chretien, F. Gouilleux, O. Muller, C. Pallard, I. Dusanter-Fourt, B. Groner, C. Lacombe, S. Gisselbrecht, and P. Mayeux. 1996. Identification of tyrosine residues within the intracellular domain of the erythropoietin receptor crucial for STAT5 activation. EMBO J. 15:2434-2441. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golde, D. W., N. Bersch, S. G. Quan, and A. J. Lusis. 1980. Production of erythroid-potentiating activity by a human T-lymphoblast cell line. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 77:593-596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heissig, B., K. Hattori, S. Dias, M. Friedrich, B. Ferris, N. R. Hackett, R. G. Crystal, P. Besmer, D. Lyden, M. A. Moore, Z. Werb, and S. Rafii. 2002. Recruitment of stem and progenitor cells from the bone marrow niche requires MMP-9 mediated release of kit-ligand. Cell 109:625-637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang, D. Y., Y. Y. Kuo, J. S. Lai, Y. Suzuki, S. Sugano, and Z. F. Chang. 2004. GATA-1 and NF-Y cooperate to mediate erythroid-specific transcription of Gfi-1B gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:3935-3946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kadri, Z., E. Petitfrere, C. Boudot, J. M. Freyssinier, S. Fichelson, P. Mayeux, H. Emonard, W. Hornebeck, B. Haye, and C. Billat. 2000. Erythropoietin induction of tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase-1 expression and secretion is mediated by mitogen-activated protein kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathways. Cell Growth Differ. 11:573-580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kapur, R., S. Chandra, R. Cooper, J. McCarthy, and D. A. Williams. 2002. Role of p38 and ERK MAP kinase in proliferation of erythroid progenitors in response to stimulation by soluble and membrane isoforms of stem cell factor. Blood 100:1287-1293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kapur, R., R. Cooper, X. Xiao, M. J. Weiss, P. Donovan, and D. A. Williams. 1999. The presence of novel amino acids in the cytoplasmic domain of stem cell factor results in hematopoietic defects in Steel(17H) mice. Blood 94:1915-1925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ko, L. J., and J. D. Engel. 1993. DNA-binding specificities of the GATA transcription factor family. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:4011-4022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li, X., E. M. Eastman, R. J. Schwartz, and R. Draghia-Akli. 1999. Synthetic muscle promoters: activities exceeding naturally occurring regulatory sequences. Nat. Biotechnol. 17:241-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liang, Q., R. J. Wiese, O. F. Bueno, Y.-S. Dai, B. E. Markham, and J. D. Molkentin. 2001. The transcription factor GATA4 is activated by extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1- and 2-mediated phosphorylation of serine 105 in cardiomyocytes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:7460-7469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maouche, L., J. P. Cartron, and S. Chretien. 1994. Different domains regulate the human erythropoietin receptor gene transcription. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:338-346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDevitt, M. A., R. A. Shivdasani, Y. Fujiwara, H. Yang, and S. H. Orkin. 1997. A “knockdown” mutation created by cis-element gene targeting reveals the dependence of erythroid cell maturation on the level of transcription factor GATA-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:6781-6785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Migliaccio, A. R., R. A. Rana, M. Sanchez, R. Lorenzini, L. Centurione, L. Bianchi, A. M. Vannucchi, G. Migliaccio, and S. H. Orkin. 2003. GATA-1 as a regulator of mast cell differentiation revealed by the phenotype of the GATA-1low mouse mutant. J. Exp. Med. 197:281-296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Millot, G. A., F. Feger, L. Garcon, W. Vainchenker, D. Dumenil, and F. Svinarchuk. 2002. MplK, a natural variant of the thrombopoietin receptor with a truncated cytoplasmic domain, binds thrombopoietin but does not interfere with thrombopoietin-mediated cell growth. Exp. Hematol. 30:166-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morceau, F., M. Schnekenburger, M. Dicato, and M. Diederich. 2004. GATA-1: friends, brothers, and coworkers. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1030:537-554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morisco, C., K. Seta, S. E. Hardt, Y. Lee, S. F. Vatner, and J. Sadoshima. 2001. Glycogen synthase kinase 3beta regulates GATA4 in cardiac myocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 276:28586-28597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Niskanen, E., J. C. Gasson, J. Egrie, K. Wipf, and D. W. Golde. 1990. Recombinant human erythroid potentiating activity enhances the effect of erythropoietin in mice. Eur. J. Haematol. 45:267-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pevny, L., C. S. Lin, V. D'Agati, M. C. Simon, S. H. Orkin, and F. Costantini. 1995. Development of hematopoietic cells lacking transcription factor GATA-1. Development 121:163-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rahuel, C., M. A. Vinit, V. Lemarchandel, J. P. Cartron, and P. H. Romeo. 1992. Erythroid-specific activity of the glycophorin B promoter requires GATA-1 mediated displacement of a repressor. EMBO J. 11:4095-4102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rylski, M., J. J. Welch, Y.-Y. Chen, D. L. Letting, J. A. Diehl, L. A. Chodosh, G. A. Blobel, and M. J. Weiss. 2003. GATA-1-mediated proliferation arrest during erythroid maturation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:5031-5042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saccani, S., S. Pantano, and G. Natoli. 2002. p38-dependent marking of inflammatory genes for increased NF-kappa B recruitment. Nat. Immunol. 3:69-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shimizu, R., T. Kuroha, O. Ohneda, X. Pan, K. Ohneda, S. Takahashi, S. Philipsen, and M. Yamamoto. 2004. Leukemogenesis caused by incapacitated GATA-1 function. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:10814-10825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shimizu, R., S. Takahashi, K. Ohneda, J. D. Engel, and M. Yamamoto. 2001. In vivo requirements for GATA-1 functional domains during primitive and definitive erythropoiesis. EMBO J. 20:5250-5260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shimizu, R., and M. Yamamoto. 2005. Gene expression regulation and domain function of hematopoietic GATA factors. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 16:129-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simon, M. C., L. Pevny, M. V. Wiles, G. Keller, F. Costantini, and S. H. Orkin. 1992. Rescue of erythroid development in gene targeted GATA-1− mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat. Genet. 1:92-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Socolovsky, M., I. Dusanter-Fourt, and H. F. Lodish. 1997. The prolactin receptor and severely truncated erythropoietin receptors support differentiation of erythroid progenitors. J. Biol. Chem. 272:14009-14012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weiss, M. J., G. Keller, and S. H. Orkin. 1994. Novel insights into erythroid development revealed through in vitro differentiation of GATA-1 embryonic stem cells. Genes Dev. 8:1184-1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weiss, M. J., C. Yu, and S. H. Orkin. 1997. Erythroid-cell-specific properties of transcription factor GATA-1 revealed by phenotypic rescue of a gene-targeted cell line. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:1642-1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu, H., X. Liu, R. Jaenisch, and H. F. Lodish. 1995. Generation of committed erythroid BFU-E and CFU-E progenitors does not require erythropoietin or the erythropoietin receptor. Cell 83:59-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.