Abstract

Loss of p53 function by mutation is common in cancer. However, most natural p53 mutations occur at a late stage in tumor development, and many clinically detectable cancers have reduced p53 expression but no p53 mutations. It remains to be fully determined what mechanisms disable p53 during malignant initiation and in cancers without mutations that directly affect p53. We show here that oncogenic signaling pathways inhibit the p53 gene transcription rate through a mechanism involving Stat3, which binds to the p53 promoter in vitro and in vivo. Site-specific mutation of a Stat3 DNA-binding site in the p53 promoter partially abrogates Stat3-induced inhibition. Stat3 activity also influences p53 response genes and affects UV-induced cell growth arrest in normal cells. Furthermore, blocking Stat3 in cancer cells up-regulates expression of p53, leading to p53-mediated tumor cell apoptosis. As a point of convergence for many oncogenic signaling pathways, Stat3 is constitutively activated at high frequency in a wide diversity of cancers and is a promising molecular target for cancer therapy. Thus, repression of p53 expression by Stat3 is likely to have an important role in development of tumors, and targeting Stat3 represents a novel therapeutic approach for p53 reactivation in many cancers lacking p53 mutations.

The p53 protein is a potent inhibitor of cell growth, arresting cell cycle progression at several points and inducing apoptosis of cells undergoing uncontrolled growth (23, 24). It has been well documented that the Ras and Myc oncogenes activate p53 by inhibiting degradation of p53 protein and that transformation by these oncogenes requires mutation of p53 itself or silencing of ARF expression in cultured cells and animal models (19, 22). The critical role of p53 as an important tumor suppressor is further underscored by the fact that p53 is the most commonly altered gene in cancer. However, p53 mutation is often a late event in malignant progression (2), and many clinically detectable cancers without p53 mutations exhibit reduced p53 expression (33, 36). In breast cancer, for example, 80% of the tumors do not have p53 mutations and a 5- to 10-fold reduction of the p53 mRNA level is found in tumor relative to normal breast cells and tissues (36). These observations indicate the importance of mechanisms to either block p53 activity or silence p53 expression during malignant initiation and progression. Indeed, it has been shown that the oncogenic potential of simian virus 40 (SV40) large T antigen depends on its ability to negatively regulate p53 activity, providing a mechanism by which oncoproteins inhibit p53 function in the absence of p53 mutations (3, 16, 34, 38). Moreover, lack of HOX5A, a p53 transcription activator, has been shown to contribute to the inhibition of p53 expression in breast cancer (36).

Several recent studies have reported that the c-Src tyrosine kinase opposes p53 activity during platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-induced mitogenesis (7, 18). Because the requirement for c-Src in PDGF receptor (PDGF-R) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGF-R) signaling has been well established (8) and dysregulation of these growth signaling pathways is commonly observed in a number of human cancers (12), we explored the role and mechanisms of oncoprotein and growth signaling in suppression of p53 activity. Our results demonstrate that both Src and PDGF-R activation lead to p53 expression inhibition. We report that p53 inhibition is mediated by activated Stat3, which binds to the p53 promoter both in vitro and in vivo. Mutation of certain Stat3-binding sites within the p53 promoter also partially restores p53 promoter activity in the presence of constitutively activated Stat3. Stat3 activation also inhibits endogenous p53 protein's ability to regulate p53-reponsive genes. Moreover, we show that blocking Stat3 induces p53 expression, leading to p53-mediated apoptosis and growth arrest in tumor cells. Our findings indicate a critical role of Stat3 in mediating suppression of p53 function by diverse growth and oncogenic signaling pathways and identify it as a molecular target for restoring p53 function in tumors that have a wild-type p53 gene.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines, mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), and retrovirus infection.

BALB/c 3T3 fibroblasts and v-Src 3T3 cells (49) were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% calf serum. A2058 human melanoma cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and maintained in RPMI supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. HCT116 p53+/+ and p53−/− cell lines were kind gifts from B. Vogelstein (Johns Hopkins University). Three retrovirus-producing cell lines (Stat3C, Stat3D, and MSCV [the control retrovirus vector]) were provided by D. Link (Washington University, Seattle) (29). Dominant-negative Stat3D contains mutations in the DNA-binding domain that prevents binding to DNA (30). 3T3 and v-Src 3T3 cells (49) were cultured in supernatant of retrovirus-producing cells supplemented with 8 μg/ml polybrene for 4 h. Primary MEFs were prepared from Stat3flox mice (a kind gift from S. Akira and K. Takeda of Osaka University, Japan), transduced with either a control empty retroviral vector or retroviral Cre vector, and selected with puromycin. Deletion of the Stat3 gene in a majority of the Cre-transduced cells was confirmed by PCR and Western blot analysis. In some experiments, MEFs were treated with PDGF-BB at 10 ng/ml for up to 8 h.

Expression vectors.

pRc/CMV-Stat3-Flag (wild-type Stat3) and pRc/CMV-Stat3C-Flag (constitutive activated Stat3) were generous gifts from J. Bromberg and J. Darnell (6). v-Src expression plasmid vector, pMvSrc, has been described previously (21). c-Src mutant 531 was provided by R. Irby and T. Yeatman of Moffitt Cancer Center. The p53 promoter/luciferase construct was a kind gift from D. Reisman (37). pCMV-DD (dominant-negative p53) and MDM2 expression vector have been described previously (40), and the BP100 promoter/luciferase construct was kindly provided by A. Levine (17). The construction and characterization of pIRES-Stat3β plasmid have been previously described (9).

Western blot analysis and electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA).

Equal amounts of total cellular proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis followed by immunoblotting with anti-murine p53 (catalog no. 9282; Cell Signaling Technology), anti-human p53 (catalog no. 554293; PharMingen), or anti-β-actin (catalog no. F3165; Sigma) antibodies. EMSA, supershift, and competition EMSAs were performed as previously described (9). The antibodies used in EMSA supershifts were Stat3 (catalog no. sc-482x; Santa Cruz) and Stat1 (catalog no. sc-346x; Santa Cruz). The oligonucleotide of hSIE is AGCTTCATTTCCCGTAAATCCCTA, and the oligonucleotide of FIRE is AGCGCCTCCCCGGCCGGGG. The oligonucleotides containing the putative Stat3-binding site at position −218 in the mouse p53 promoter and its mutant form used in EMSA are as follows: wild-type, 5′(−218)-GGTCCACTTACGATAAAAACT-3′; mutant, 5′(−218)-GGTCCACggcCGATAAAAACT-3′ (mutated nucleotides are in lowercase, and the consensus sequence of the Stat3 DNA-binding site is underlined).

Northern blot analysis and nuclear run-on assays.

For Northern blot analysis, 20 μg RNA was electrophoresed on 1% agarose-formaldehyde gel and transferred to nylon membrane. To detect the mouse p53 transcript, a 764-bp fragment of mouse p53 cDNA was labeled by All-in-One random primer DNA labeling mix (Sigma). Nuclear run-on assays were performed essentially as described previously (15). Both linearized p53 cDNA-containing plasmid and p53 cDNA fragment were used for detecting labeled, newly synthesized p53 RNA.

Stat3 and p53 small interfering RNA (siRNA).

The sequences for Stat3 siRNA and a negative control (scrambled sequence) were 5′-GATCCCGTCAGGTTGCTGGTCAAATTTCAAGAGAATTTGACCAGCAACCTGACTTTTTTGGAAA-3′ and 5′-GATCCACTACCGTTGTTATAGGTGTTCAAGAGACACCTATAACAACGGTAGTTTTTTGGAAA-3′, respectively. These two oligonucleotides were inserted into pSilencer hygro siRNA expression vectors (Ambion). After transfecting plasmids into A2058 tumor cells, cells were selected with 300 μg/ml hygromycin. In addition, siRNA oligonucleotides were obtained from Dharmacon RNA Technologies. Control and p53 siRNA oligonucleotides were siGENOME SMARTpool reagents. Each one contains four pooled siRNAs (control siRNA, catalog no. D-001206-13; mouse p53 siRNA, catalog no. M-040642-00; human p53 siRNA, catalog no. M-003329-01). The sense sequence of Stat3 siRNA was 5′-CCAACGACCUGCAGCAAUAUU (catalog no. D-001206-13-20). Transient transfection of siRNA oligonucleotides was performed at 10 nM with TransIT-TKO Transfection Reagent.

Deletion and site-specific mutagenesis.

The mouse p53 promoter reporter construct (pGL3-p53) consists of a 1.9-kb genomic DNA fragment containing the 5′ region of the p53 gene upstream of the transcription initiation site. pGL3-p53(−811/+345) was cloned by ligating the region containing −811 to +345 into the SmaI site of pGL3-basic construct. To generate pGL3-p53(−242/+345), the region containing −1547 to −243 was deleted from pGL3-p53 by digestion with restriction enzymes KpnI and SacI. There are three potential Stat3-binding sites, TT(N4)AA and TT(N5)AA (39), within the −243/+354 p53 sequence. The putative Stat3-binding site at −218 was specifically mutated in the context of the pGL3-p53(−242/+354) construct using the unique site elimination method (Clontech) (14). The Stat3 site was changed from 5′-TTACGATAA-3′ to 5′-ggcCGATAA-3′, while the selection primer changed a unique XbaI site 3′ of the luciferase gene to an NruI site. Mutations were confirmed by sequencing at the Molecular Biology Core Facility, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center.

Transfections and luciferase assays.

Transfections of promoter constructs in combination with various vectors for luciferase assays were carried out using Lipofectamine reagent according to the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen). Briefly, transfection mixture contained a total of 1 μg of DNA, including 0.1 μg of the indicated luciferase reporter construct, 10 ng β-galactosidase expression vector (internal control), 0.9 μg of the tested expression vectors, or control empty vectors. Cytosolic fractions were prepared 48 h posttransfection. Samples were analyzed with a luminometer and normalized to β-galactosidase activity by colorimetric assay at A570 as an internal control for transfection efficiency.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays, PCR, and real-time PCR.

Preparation of chromatin-DNA and ChIP assays were performed as described by the protocol supplied by Upstate Biotechnology. Stat1 (catalog no. sc-346), Stat3 (catalog no. sc-482 and sc-7179), Stat5 (catalog no. sc-835), and CD40 (catalog no. sc-977) antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used for ChIP assays. Purified DNA was subjected to PCR using primers specific for a 427-bp region (−387 to +40) spanning the Stat3-binding site (−218) in the p53 promoter. The sequences of the PCR primers used are as follows: p53 forward (+), 5′GGGCCCGTGTTGGTTCATCC-3′; and p53 reverse (−), 5′CCGCGAGACTCCTGGCACAA-3′; actin forward (+), 5′CAGGCCCTTCTTATCCAAGT-3′; and reverse (−), 5′CTAAGCCCTCAGAACAACTGCTTAA-3′. Primers were used for normalization. PCR was run for 30 cycles (94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, 72°C for 1 min), and final products were resolved on a 1.5% agarose gel.

Primers used for real-time PCRs are as follows: p53 forward (+), 5′CCGTGTTGGTTCATCCCTGTA-3′; and p53 reverse (−), 5′TTTTGGATTTTTAAGACAGAGTCTTTGTA-3′. The TaqMan p53 probe used was 5′CAGGAAGACGCCGCGAATTCCA-3′. Real-time PCR assays were performed by the Molecular Biology Core at the Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute.

[3H]thymidine ([3H]TdR) incorporation assays.

Transfected cells were plated at 1 × 104/well in a 96-well plate, followed by UV treatment (Stratagene UV Stratalinker) 24 h later. Four hours after UV treatment, 0.25 μCi 3H-TdR was added to label the cells. Four hours after adding 3H-TdR, cells were transferred to glass fiber filters by an automated cell harvester and 3H-TdR incorporation was determined with a liquid scintillation β-counter.

RESULTS

Oncogenic pathways that signal through Stat3 inhibit p53 expression.

Previous studies have reported that the c-Src tyrosine kinase opposes p53 activity during PDGF-induced mitogenesis (7, 18). Because the requirement for c-Src in PDGF-R signaling has been well established (8) and dysregulation of c-Src and PDGF-R is commonly observed in a number of human cancers (12), we explored their role in the suppression of p53 expression. We first determined whether Src tyrosine kinase, known to oppose p53 activity (7), might inhibit p53 expression. Both p53 mRNA and protein levels are lower in v-Src 3T3 cells when compared to their parental BALB/c 3T3 cells (Fig. 1A). To rule out the possibility that there might be mutations associated with long-term culturing of v-Src 3T3 cells, we performed transient transfection of a plasmid vector encoding v-Src into 3T3 cells. Northern blot analysis from these transient transfection experiments confirms that v-Src inhibits p53 gene expression (Fig. 1B). Stat3 is one of the critical downstream targets of active Src tyrosine kinase (5, 42, 49). We determined whether cotransfecting v-Src with an expression vector containing the wild-type Stat3 gene would further inhibit p53 expression. Results in Fig. 1B show that an increase in Stat3 activity correlates with inhibition of p53 expression. Our data further showed that PDGF, which activates Stat3, also inhibits p53 expression (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

FIG. 1.

p53 expression is inhibited at both RNA and protein levels in a Stat3-dependent manner. (A) p53 mRNA and protein levels in BALB/c 3T3 and v-Src 3T3 fibroblasts were compared by Northern blot and Western blot analyses. GAPDH and β-actin were used here to ensure that similar amounts of total RNAs and proteins were loaded in each lane. (B) Transient transfection of v-Src expression vector enhances Stat3 activity (EMSA, top panel) and inhibits p53 RNA levels (Northern blot analysis, lower panel). Cotransfecting v-Src expression vector with a Stat3 expression vector further inhibits p53 expression. (C) p53 expression is regulated by Stat3. Top gel, Stat3 DNA-binding activity in the indicated cells as measured by EMSA. Middle gel, Northern blot analysis. Bottom gel, Western blot analysis. 3T3, 3T3 BALB/c fibroblasts; v-Src, v-Src 3T3 fibroblasts; MEFs, mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Stat3D, 3T3 cells stably transduced with MSCV-Stat3D; Stat3C, MEFs transfected with Stat3C plasmid expression vector. wt, wild type.

To determine whether Stat3 mediates Src-induced p53 down-regulation, a dominant-negative mutant of Stat3, Stat3D, was introduced into v-Src 3T3 cells by retroviral transduction. Stat3D contains EE to AA mutations in the DNA-binding domain but is capable of forming heterodimers with endogenous wild-type Stat3, preventing its binding to DNA (29, 46). In the absence of Stat3 activity, v-Src-induced p53 mRNA and protein down-regulation was abrogated, leading to restoration of p53 expression (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, expression of Stat3C, which is constitutively activated without tyrosine phosphorylation (6), increases Stat3 activity and lowers levels of both p53 mRNA and protein expression in BALB/c 3T3 cells and MEFs (Fig. 1C). We also assessed p53 expression in Stat3−/− MEFs, which displayed an increased level of p53 RNA when compared to Stat3+/+ MEFs (Fig. 1C).

Stat3 inhibits p53 expression at the transcription level.

To determine whether inhibition of p53 expression by Stat3 occurs at the transcriptional level, p53 promoter activity in the presence of activated c-Src or activated Stat3 was assessed using luciferase reporter constructs in BALB/c 3T3 fibroblasts. An activated c-Src mutant was able to inhibit p53 promoter activity, especially when cotransfected with wild-type Stat3 (Fig. 2A). To determine whether Stat3 activity by itself was sufficient to inhibit p53 promoter activity, the constitutively activated Stat3 mutant, Stat3C, was used in this p53 promoter reporter assay. Cotransfection of the Stat3C expression vector into 3T3 cells had no influence on activity of the pGL3basic or pGL3SV40 reporters, as expected. By contrast, cotransfection of the Stat3C expression vector and the pGL3p53 reporter resulted in considerable inhibition of luciferase (Fig. 2B), suggesting that Stat3 activity inhibits p53 promoter activity.

FIG. 2.

Stat3 activity inhibits p53 transcription. (A) 3T3 fibroblasts were transfected with a p53 promoter/luciferase reporter construct in the presence of a control empty vector, pcDNA3, a wild-type Stat3 expression vector, a constitutively activated c-Src mutant, c-Src531, or both wild-type (WT) Stat3 and a c-Src mutant as indicated. Luciferase activity was normalized to transfection efficiency using β-galactosidase activity as an internal control. Luciferase activity of pcDNA3-transfected cells was assigned as 100%. Data represent means ± standard deviations; n = 3. (B) Constitutive Stat3 activity inhibits p53 promoter activity. 3T3 fibroblasts were transfected with either a control empty vector, pcDNA3, or a Stat3C expression vector in the presence of one of the promoter/luciferase reporter constructs as indicated. Luciferase activity was normalized to transfection efficiency using β-galactosidase activity as an internal control. (C and D) Nuclear run-on assays. 32P-labeled nuclear RNAs were hybridized to membranes containing p53 and GAPDH cDNA fragments. Stat3 activation was induced by either PDGF (10 ng/ml for 8 h) or v-Src. Stat3D was used to block Stat3 signaling in v-Src-transformed 3T3 cells. These experiments were repeated twice with similar results. The p53/GAPDH ratio was based on band intensities determined by phosphorimaging.

To further confirm that Stat3 inhibits p53 at the transcriptional level, nuclear run-on assays were performed. PDGF-R activation, which activates c-Src and Stat3, led to an inhibition of p53 transcription rate as shown by nuclear run-on assays (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, activated Src, which requires Stat3 for suppressing p53 promoter activity, inhibited p53 RNA synthesis, while blocking Stat3 in v-Src 3T3 cells with a dominant-negative Stat3 mutant, Stat3D, reverses this inhibition (Fig. 2D).

Stat3 protein interacts with the p53 promoter.

Because Stat3 signaling down-regulates p53 promoter activity, we next identified DNA sequences within the p53 promoter that might be involved in Stat3-mediated repression. Deletion of the 5′ sequence up to −242 had no detectable effect on Stat3-induced inhibition of p53 promoter activity (data not shown), suggesting that the target sequence of Stat3-mediated repression is located downstream of nucleotide −242. Three potential STAT-binding sites with the consensus sequence TT(N4)AA or TT(N5)AA (39) were identified in the −242/+345 region of the mouse p53 promoter (positions −218, −109, and +201). Examination of the human p53 promoter reveals that it also contains multiple potential STAT-binding sites, five of which are located within 70 bp of the analogous STAT-binding site (−218) in the mouse promoter. Next, we determined whether Stat3 protein interacts directly with the endogenous p53 promoter in vivo using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays. ChIP assays with different dilutions of input samples are shown in Fig. S2 in the supplemental material. As shown in Fig. 3A, immunoprecipitation of solubilized chromatin prepared from 3T3 and v-Src 3T3 cells with a Stat3 antibody, followed by PCR using oligonucleotide primers that amplify a 427-bp region spanning −387 to +40 in the p53 promoter, yielded the expected 427-bp band in v-Src 3T3 but not in 3T3 cells. In contrast, immunoprecipitation either in the absence of primary antibody or using CD40 (irrelevant control), Stat1, or Stat5 antibody, followed by PCR with the same oligonucleotide primers, did not yield an increase in the 427-bp band detected from v-Src 3T3 ChIP preparations. Further, activation of Stat1 by gamma interferon (IFN-γ) in 3T3 and v-Src 3T3 cells failed to generate a Stat1/p53 promoter complex in vivo (Fig. 3A). Treating 3T3 cells with PDGF also led to Stat3 binding to the p53 promoter as shown by the ChIP assays (Fig. 3B). The interaction between Stat3 and the p53 promoter was confirmed by ChIP assays followed by quantitative real-time PCR amplification of the chromatin immunoprecipitates (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 3.

Stat3 protein binds to the p53 promoter in vivo (ChIP assays). (A) Gel electrophoresis of PCR products using primers detecting the p53 promoter following ChIP with the indicated antibodies. Anti-CD40 rabbit polyclonal antibody was used as an irrelevant control antibody. In the case of the Stat1 antibody ChIP assay, IFN-γ (2 h at 100 U/ml) was used to stimulate Stat1 activity, which was detected by EMSA (data not shown). These experiments were repeated twice with similar results. (B) PDGF stimulation (10 ng/ml for 8 h), which activates Stat3, also leads to Stat3 binding to the p53 promoter region as shown by ChIP. (C) ChIP assays of chromatin prepared from 3T3 and v-Src 3T3 cells using the indicated antibodies followed by real-time PCR and normalized to the amount of nonspecifically precipitated β-actin promoter in the same samples. Ab, antibody; IgG, immunoglobulin G.

Stat3 binds to the p53 promoter in vitro as determined by EMSA.

To further determine whether Stat3 protein binds to the mouse p53 promoter fragment (−242 to +345), DNA-binding activity of the three putative STAT-binding sequences was measured by EMSA. Although oligonucleotides containing STAT-binding sequences at positions −109 and +201 were not able to form stable DNA/protein complexes with a STAT protein(s) under our experimental conditions (data not shown), the labeled putative STAT-binding site at position −218 of the p53 promoter STAT protein(s) was able to form a DNA/protein complex (Fig. 4A). Stat3 and Stat1 antibodies were used to confirm the identity of STAT proteins binding to the STAT-binding site (−218) in the p53 promoter. EMSA using Stat1 and Stat3 antibodies show that the DNA/protein complex indeed contained Stat3 protein. While an oligonucleotide containing the putative p53 STAT-binding site at position −218 effectively competed for the formation of this DNA/protein complex, an irrelevant oligonucleotide (FIRE) and the mutated p53 STAT-binding oligonucleotide at −218 failed to inhibit formation of the DNA/protein complex. In addition, hSIE, a high-affinity variant of the STAT-binding site in the c-fos promoter (45), also effectively competed for the protein in the DNA/protein complex.

FIG. 4.

Stat3 protein binds to the p53 promoter and contributes to repression of the p53 promoter transcription activity. (A) Stat3 protein and the putative Stat3 DNA-binding site in the p53 promoter form protein-DNA complexes (EMSA). Top panel, labeled wild-type p53(−218) was able to form a DNA/protein complex (shift), while the mutated p53(−218M) oligonucleotides could not in v-Src 3T3 cells. Stat3 antibody (α-Stat3) but not Stat1 antibody (α-Stat1) was able to supershift the complex. Both wild-type p53(−218) and hSIE oligonucleotides disrupted the DNA/protein complex (shift), but the p53(-218M) mutant and FIRE, a nonspecific oligonucleotide, failed. In addition, labeled p53(218M) (mutant) could not form a DNA/protein complex. Parallel EMSA experiments were performed with a labeled hSIE probe (lower panel), confirming that the p53(-218) Stat3 site can interact with Stat3 protein. (B) Stat3-induced repression of p53 is partially mediated by STAT DNA-binding site at −218. 3T3 fibroblasts were transfected with either pcDNA3 or a Stat3C expression vector in the presence of one of the promoter/luciferase reporter constructs as indicated. An SV40 promoter/luciferase reporter construct was used as a negative control. Data are presented as fold repression by Stat3C (value of luciferase activity in pcDNA3-transfected cells divided by value of luciferase activity in Stat3C-transfected cells; fold repression of SV40 promoter activity by Stat3C was designated as 1). Luciferase activity was normalized to transfection efficiency using β-galactosidase activity as an internal control. Data shown are means ± standard deviations (n = 3). M, mutant.

The binding of Stat3 to the p53 promoter as detected by the p53(-218) probe is relatively weak, which is not surprising as individual natural STAT-binding sites often have weak binding activity (32, 47, 48). We further performed EMSA using labeled hSIE as probe. Both the putative Stat3-binding site in the p53 promoter and the hSIE oligonucleotides effectively reduced formation of the hSIE DNA/protein complex (Fig. 4A, lower panel), while the p53(-218) mutant and an irrelevant oligonucleotide (FIRE) did not. The specificity of Stat3 binding to hSIE was also confirmed by Stat1 and Stat3 antibodies. The EMSA data generated by using both p53(-218) and hSIE probes show that Stat3 can bind to the p53 promoter.

Interaction between Stat3 protein and the p53 promoter contributes to Stat3-mediated inhibition.

To determine if Stat3-mediated p53 transcriptional inhibition involves Stat3 interaction with the p53 promoter, we investigated whether site-specific mutations at the Stat3-binding site would alleviate the inhibitory effect of Stat3 protein on p53 promoter activity. Site-specific mutations were introduced at the Stat3-binding site (position −218) of the pGL3-p53(−242/+345) construct. After transfecting the indicated promoter/reporter constructs with either pcDNA3 control empty vector or Stat3C expressing vector, luciferase activity was measured. As expected, cotransfection of Stat3C and the pGL3-SV40 reporter construct did not repress SV40 promoter activity (Fig. 4B). Although cotransfection of Stat3C with pGL3-p53(−242/+345) reduced p53 promoter activity, this inhibitory effect was considerably attenuated when the Stat3-binding site was mutated (Fig. 4B).

Stat3 activity inhibits the p53-responsive element and UV-induced p53-mediated growth arrest.

Because many p53-mediated effects depend on p53 transcriptional activity (35, 44), we assessed whether Src/Stat3-induced inhibition of p53 expression down-regulates the transcriptional activity of promoters containing p53-responsive elements. pGL2-BP100 is a luciferase reporter vector with a basal promoter driven by a p53-responsive element (11). When this vector was transfected into Stat3C 3T3 cells, p53-responsive luciferase expression was significantly reduced (Fig. 5A). In addition, transfection of a vector encoding MDM2 (10), which down-regulates endogenous p53 protein levels, resulted in inhibition of p53-responsive luciferase expression in both 3T3 and Stat3C 3T3 cells, as expected. The ability of Stat3C to repress p53-responsive elements was further confirmed by transient transfection of pGL2-BP100 with either a control vector, pcDNA3, or the Stat3C expression vector into 3T3 cells (data not shown). These findings demonstrate that constitutive activity of Stat3 can inhibit the expression of p53-responsive genes regulated by endogenous p53.

FIG. 5.

Stat3 activity inhibits p53-responsive promoter activity and UV-induced cell growth arrest. (A) Stat3C inhibits activity of the p53-responsive element mediated by endogenous p53 protein. pGL2-BP100 is a derivative of pGL2-basic promoter/luciferase reporter constructs driven by the p53-responsive element. An expression vector encoding MDM2 was cotransfected into 3T3MSCV and 3T3Stat3C expressing stable cell lines. (B) Constitutive Stat3 activity resists UV-induced growth arrest. For the top panel, 8 h after UV irradiation at indicated UV doses, 3H-TdR incorporation and Western blot analyses for p53 protein levels in the treated 3T3 cells were performed. These experiments were repeated at least twice with similar results. (C) Lack of Stat3 activity in Stat3−/− MEFs allows an increase in UV-induced p53 expression and enhanced growth inhibition compared to Stat3+/+ MEFs. (D) Stat3 blockade-mediated, UV-induced decrease in thymidine incorporation is p53 dependent. Stat3−/− MEFs used in panel C were transiently transfected with control or p53 siRNAs, followed by UV treatment at the indicated doses. The effectiveness of the siRNA was shown by Western blot analysis (lower panel). Data shown represents means ± standard deviations of four independent experiments. P < 0.01 (comparing Stat3−/− with Stat3+/+ MEFs as well as comparing control siRNA with p53 siRNA in Stat3−/− MEFs).

We next investigated whether Stat3 signaling might have a role in mediating resistance of UV-induced, p53-associated cell growth arrest. As shown in Fig. 5B, expression of constitutively activated Stat3, Stat3C, resulted in resistance to UV-induced growth arrest. Moreover, the expected increase in p53 protein levels following UV irradiation was consistently smaller in Stat3C 3T3 cells when compared to MSCV 3T3 control cells. Conversely, p53 protein levels after UV exposure were higher in Stat3−/− MEFs than in Stat3+/+ MEFs. In addition, UV could induce more growth inhibition in the Stat3−/− MEFs than in Stat3+/+ MEFs (Fig. 5C). While UV-induced growth arrest is not all p53 dependent, Stat3 blockade-mediated increase in UV-induced growth arrest involves p53 as shown by p53 siRNA (Fig. 5D). The effectiveness of the p53 siRNA is shown in Fig. 5D (lower panel). The ability of Stat3 activity to inhibit p53 expression and allow more proliferation of cells that may contain DNA damage or mutations is consistent with a potential role of Stat3 in promoting UV-induced tumorigenesis.

Blocking Stat3 activates p53 expression in human cancer cells.

In certain human cancers, mutation of p53 is uncommon, but p53 mRNA protein expression in tumor cell lines and tissues are often reduced compared to their normal counterparts (33, 36). To determine whether blocking Stat3 would restore p53 expression in cancer cells, we transiently transfected pIRES(EGFP)-Stat3β (9) (transfection efficiency of approximately 30% based on the percentage of cells that exhibit green fluorescence) into A2058 melanoma cells. Blocking Stat3 in these tumor cells led to increased p53 expression at both the mRNA and the protein levels (Fig. 6A, left panel). In addition, inhibiting Stat3 in the A2058 melanoma cells resulted in increased expression of p21, a downstream effector gene of p53 (Fig. 6A, middle panel). Because transient transfection does not allow Stat3 inhibition in the majority of cells, we generated A2058 stable clones that express Stat3 siRNA. While Stat3 expression was still detectable in these clones (which is probably why these clones survived), a reduction in Stat3 activity was expected to be in the majority of cells. An increase in p53 protein levels was found in the clones with reduced Stat3 protein (Fig. 6A, right panel). Further evidence that blocking Stat3 signaling in tumor cells may enhance p53 expression and activity came from the observation that interrupting Stat3 signaling in A2058 human melanoma cells led to increased activity of a p53-responsive element (data not shown).

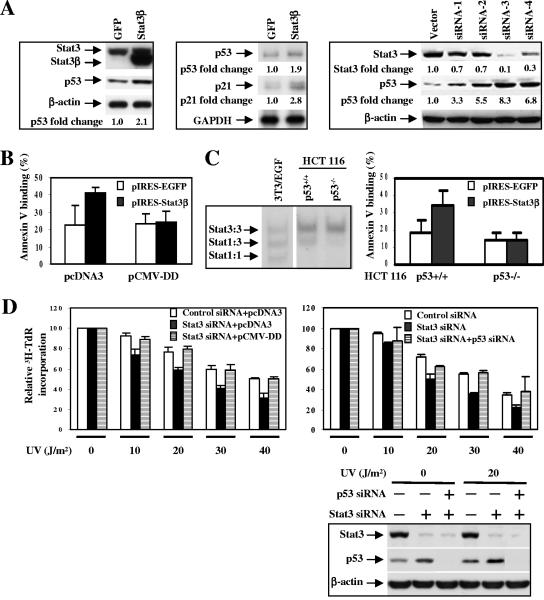

FIG. 6.

Blocking Stat3 in human tumor cells induces p53-dependent tumor cell apoptosis and UV-induced growth arrest. (A) Inhibiting Stat3 activity up-regulates p53 and p21 expression. In the left panel, Western blots show expression of dominant-negative Stat3, Stat3β, in the human melanoma cell line A2058. Overexpression of Stat3β is expected to inhibit wild-type Stat3 activity. The middle panel shows a RNase protection assay of A2058 human melanoma cells. The right panel shows Western blot analysis of stable clones of A2058 tumor cells transfected with either control vector or Stat3 siRNA expressing vector. Fold changes were based on band intensities quantified by phosphorimaging. (B) Blocking Stat3 in tumor cells induces p53-dependent apoptosis. pIRES-EGFP and pIRES-Stat3β were cotransfected with either pcDNA3 control empty vector or the p53 dominant-negative mutant, pCMV-DD. A2058 tumor cells positive for green fluorescent protein (GFP) (transfected cells) were assayed for annexin V binding by flow cytometry. (C) Targeting Stat3 induces apoptosis of p53+/+ but not p53−/− HCT116 colon cancer cells. Left panel, Stat3 EMSA indicates Stat3 is activated in HCT116 cells. Right panel, flow cytometry analyses of Annexin V binding of GFP-positive cells; n = 3. (D) Blocking Stat3 in A2058 human melanoma cells allows more UV-induced growth arrest, which is p53 dependent. Left panel, Stat3 siRNA A2058 tumor cells (same as in panel A) were transfected with a control empty vector or a p53 dominant-negative expression vector, pCMV-DD (n = 3). Right panel, Stat3 siRNA A2058 tumor cells (same as in panel A) were transfected with 10 nM of either a control siRNA or p53 siRNA. The effectiveness of the siRNA was shown by Western blot analysis (lower panel). The figure shown represents means ± standard deviations of four experiments. Comparing Stat3 siRNA with control siRNA in A2058, P is <0.01 for both panels.

Blocking Stat3 induces p53-mediated tumor cell apoptosis and facilitates UV-induced tumor cell growth inhibition.

We next determined whether Stat3 inhibition would result in p53-mediated tumor cell apoptosis. For this purpose, we performed transient transfection with Stat3β because Stat3β expression is linked to EGFP, allowing us to examine cells that are cotransfected with Stat3β and a vector encoding a dominant-negative mutant of p53. Results from these experiments showed that Stat3β-induced apoptosis was attenuated in the presence of a p53 dominant-negative mutant, pCMV-DD (40), suggesting a role for p53 in Stat3 blockade-induced tumor cell death (Fig. 6B). p53 up-regulation by targeting Stat3-induced, p53-mediated tumor cell apoptosis was also demonstrated in HCT116 colon cancer cells, since interrupting Stat3 signaling causes apoptosis in p53+/+ but not p53−/− HCT116 cells (Fig. 6C). We also examined whether Stat3 blockade could enhance UV-induced growth arrest in human tumor cells. A2058 tumor cells stably expressing Stat3 siRNA were subjected to UV treatment. Results shown in Fig. 6D indicate that blocking Stat3 with siRNA significantly enhances UV-induced tumor cell growth arrest (P < 0.01). However, transfecting either a dominant-negative p53 protein (pCMV-DD) or p53 siRNA overcame the Stat3 siRNA-mediated, UV-induced growth arrest in a dose-dependent manner. These results show that p53 mediates the Stat3-induced apoptosis and cell growth arrest.

DISCUSSION

Our findings demonstrate that activation of growth signaling pathways, many of which signal through Stat3 (13, 25, 41, 50, 51), inhibits p53 gene expression. This negative regulation of p53 expression is expected to facilitate short-term cell proliferation without p53 mutations under normal physiological conditions. Our findings also indicate that oncogenic transformation driven by deregulated growth signaling, which constitutively activates Stat3, can bypass the requirement for a mutation(s) affecting the p53 gene. Although increased degradation by mdm2 and/or loss of function mutations account for p53 inactivation in many cancers (1), inhibition of p53 gene expression may also play a critical role in malignant initiation and progression. Consistent with this possibility, HOXA5, a p53 transcription activator, is frequently inactivated in breast cancer (36). As a point of convergence for many growth and cytokine signaling pathways (13, 41) that are commonly overactive in tumor cells, Stat3 is constitutively activated with high frequency in diverse cancers (4, 12, 50), suggesting that repression of p53 expression by Stat3 is also likely to have a role in tumor development. Lack of HOXA5 (36) and a high frequency of activated Stat3 (50) provide potential mechanisms that may explain why p53 expression is commonly inhibited in breast cancer.

While our results show that Stat3 activity inversely correlates with p53 expression and that Stat3 protein interacts with the p53 promoter, the detailed molecular mechanism(s) by which Stat3 negatively regulates p53 expression remains to be elucidated. Lack of complete elimination of Stat3 inhibitory effects on p53 promoter activity may be due to the fact that there are multiple STAT-binding sites in the p53 promoter (three identified in the p53 −242/+345 fragment). Alternatively, mutation at the Stat3 site may affect another transcription factor(s) important for p53 gene expression. Nevertheless, in conjunction with the ChIP and EMSA data showing that Stat3 interacts with the p53 promoter, these results indicate that Stat3 at least partially exerts its activity through DNA binding.

Tumor cell growth and survival may require both elevation of Stat3 activity and down-regulation of wild-type p53 expression. Consistent with this notion are the findings that wild-type p53 down-regulates Stat3 phosphorylation and DNA-binding activity in breast and prostate cancer cells (26, 27). We demonstrate here that Stat3 activity represses wild-type p53 gene expression. Thus, activated Stat3 and wild-type p53 negatively regulate each other. One possible explanation for this reciprocal negative regulation is the opposing biological functions of activated Stat3 and wild-type p53. In particular, Stat3 signaling is usually proproliferative and antiapoptiotic (50), whereas wild-type p53 is typically antiproliferative and proapoptotic (35, 44). Based on these observations, we propose that Stat3 activation and wild-type p53 expression are incompatible with each other. Consequently, normal cells may have evolved mechanisms for reciprocal negative regulation of Stat3 and p53 in order to permit coordinated regulation of cell proliferation and survival under physiological conditions. Tumor cells may have used these reciprocal negative regulatory mechanisms to gain growth or survival advantages, especially during early tumor development, allowing Stat3-mediated growth or survival without mutation of the p53 gene. At the same time, mutation of the p53 gene can further promote Stat3-mediated tumor cell growth or survival. The abilities of Stat3 and p53 proteins to negatively regulate each other underscore the importance of impairing p53 function for malignant progression.

Numerous studies have shown that Stat3 activity promotes tumor cell survival by up-regulating antiapoptotic genes (50). While Stat3 inhibition-induced apoptosis is thought to be mediated primarily by down-regulation of antiapoptotic genes, our current data suggest that activating a proapoptotic gene can also be critical for tumor cell death. While the precise mechanisms by which Stat3 inhibit gene expression remain to be defined, up-regulation of other proapoptotic genes, which include Fas, TRAIL, IFN-β, and tumor necrosis factor alpha, by Stat3 inhibition has also been documented (20, 31, 46). Many studies have shown that tumor cells are more sensitive to Stat3 inhibitors than normal cells (50). This is likely due to an increased dependence of tumor cells on persistent Stat3 activity compared to normal cells. Thus, inhibition of Stat3 activity in tumor cells harboring wild-type p53 may provide a therapeutic advantage. Because transcription factors such as Stat3 can be inhibited specifically by small molecules (28, 43), our findings identify Stat3 as a novel therapeutic target for reactivating p53 expression and functions in diverse human cancers with wild-type p53.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Molecular Imaging Core at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, an ACS Institutional grant, and the Tsai-fan Yu Cancer Research Endowment.

Real-time PCR and flow cytometry analyses were performed by the Molecular Biology and Flow Cytometry Core Facilities at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this paper can be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baker, S. J., E. R. Fearon, J. M. Nigro, S. R. Hamilton, A. C. Preisinger, J. M. Jessup, P. van Tuinen, D. H. Ledbetter, D. F. Barker, Y. Nakamura, et al. 1989. Chromosome 17 deletions and p53 gene mutations in colorectal carcinomas. Science 244:217-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker, S. J., A. C. Preisinger, J. M. Jessup, C. Paraskeva, S. Markowitz, J. K. Wilson, S. Hamilton, and B. Vogelstein. 1990. p53 gene mutations occur in combination with 17p allelic deletions as late events in colorectal tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 50:7717-7722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bargonetti, J., I. Reynisdottir, P. Friedman, and C. Prives. 1992. Site-specific binding of wild-type p53 to cellular DNA is inhibited by SV40 T antigen and mutant P53. Genes Dev. 6:1886-1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bromberg, J., and J. E. Darnell, Jr. 2000. The role of STATs in transcriptional control and their impact on cellular function. Oncogene 19:2468-2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bromberg, J. F., C. M. Horvath, D. Besser, W. W. Lathem, and J. E. Darnell, Jr. 1998. Stat3 activation is required for cellular transformation by v-src. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:2553-2558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bromberg, J. F., M. H. Wrzeszczynska, G. Devgan, Y. Zhao, R. G. Pestell, C. Albanese, and J. E. Darnell, Jr. 1999. Stat3 as an oncogene. Cell 98:295-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Broome, M. A., and S. A. Courtneidge. 2000. No requirement for Src family kinases for PDGF signaling in fibroblasts expressing SV40 large T antigen. Oncogene 19:2867-2869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Broome, M. A., and T. Hunter. 1996. Requirement for c-Src catalytic activity and the SH3 domain in platelet-derived growth factor BB and epidermal growth factor mitogenic signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 271:16798-16806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Catlett-Falcone, R., T. H. Landowski, M. M. Oshiro, J. Turkson, A. Levitzki, R. Savino, G. Ciliberto, L. Moscinski, J. L. Fernandez-Luna, G. Nunez, W. S. Dalton, and R. Jove. 1999. Constitutive activation of Stat3 signaling confers resistance to apoptosis in human U266 myeloma cells. Immunity 10:105-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen, J., V. Marechal, and A. J. Levine. 1993. Mapping of the p53 and mdm-2 interaction domains. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:4107-4114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen, L., S. Agrawal, W. Zhou, R. Zhang, and J. Chen. 1998. Synergistic activation of p53 by inhibition of MDM2 expression and DNA damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:195-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darnell, J. E., Jr. 2002. Transcription factors as targets for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2:740-749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Darnell, J. E., Jr., I. M. Kerr, and G. R. Stark. 1994. Jak-STAT pathways and transcriptional activation in response to IFNs and other extracellular signaling proteins. Science 264:1415-1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deng, W. P., and J. A. Nickoloff. 1992. Site-directed mutagenesis of virtually any plasmid by eliminating a unique site. Anal. Biochem. 200:81-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Derman, E., K. Krauter, L. Walling, C. Weinberger, M. Ray, and J. E. Darnell, Jr. 1981. Transcriptional control in the production of liver-specific mRNAs. Cell 23:731-739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farmer, G., J. Bargonetti, H. Zhu, P. Friedman, R. Prywes, and C. Prives. 1992. Wild-type p53 activates transcription in vitro. Nature 358:83-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freedman, D. A., C. B. Epstein, J. C. Roth, and A. J. Levine. 1997. A genetic approach to mapping the p53 binding site in the MDM2 protein. Mol. Med. 3:248-259. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Furstoss, O., K. Dorey, V. Simon, D. Barila, G. Superti-Furga, and S. Roche. 2002. c-Abl is an effector of Src for growth factor-induced c-myc expression and DNA synthesis. EMBO J. 21:514-524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hahn, W. C., and R. A. Weinberg. 2002. Modelling the molecular circuitry of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2:331-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ivanov, V. N., A. Bhoumik, M. Krasilnikov, R. Raz, L. B. Owen-Schwaub, D. Levy, C. M. Horvath, and Z. Ronai. 2001. Cooperation between STAT3 and c-jun suppresses Fas transcription. Mol. Cell 7:517-528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson, P. J., P. M. Coussens, A. V. Danko, and D. Shalloway. 1985. Overexpressed pp60c-src can induce focus formation without complete transformation of NIH 3T3 cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 5:1073-1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kamijo, T., F. Zindy, M. F. Roussel, D. E. Quelle, J. R. Downing, R. A. Ashmun, G. Grosveld, and C. J. Sherr. 1997. Tumor suppression at the mouse INK4a locus mediated by the alternative reading frame product p19ARF. Cell 91:649-659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levine, A. J. 1997. p53, the cellular gatekeeper for growth and division. Cell 88:323-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levine, A. J., J. Momand, and C. A. Finlay. 1991. The p53 tumour suppressor gene. Nature 351:453-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levy, D. E., and J. E. J. Darnell. 2002. Stats: transcriptional control and biological impact. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 3:651-662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin, J., X. Jin, K. Rothman, H. J. Lin, H. Tang, and W. Burke. 2002. Modulation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 activities by p53 tumor suppressor in breast cancer cell. Cancer Res. 62:376-380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin, J., H. Tang, X. Jin, G. Jia, and J. T. Hsieh. 2002. p53 regulates Stat3 phosphorylation and DNA binding activity in human prostate cancer cells expressing constitutively active Stat3. Oncogene 21:3082-3088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu, C., B. M. Smith, K. Ajito, H. Komatsu, L. Gomez-Paloma, T. Li, E. A. Theodorakis, K. C. Nicolaou, and P. K. Vogt. 1996. Sequence-selective carbohydrate-DNA interaction: dimeric and monomeric forms of the calicheamicin oligosaccharide interfere with transcription factor function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:940-944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McLemore, M. L., S. Grewal, F. Liu, A. Archambault, J. Poursine-Laurent, J. Haug, and D. C. Link. 2001. STAT-3 activation is required for normal G-CSF-dependent proliferation and granulocytic differentiation. Immunity 14:193-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakajima, K., Y. Yamanaka, K. Nakae, H. Kojima, M. Ichiba, N. Kiuchi, T. Kitaoka, T. Fukada, M. Hibi, and T. Hirano. 1996. A central role for Stat3 in IL-6-induced regulation of growth and differentiation in M1 leukemia cells. EMBO J. 15:3651-3658. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Niu, G., K. H. Shain, M. Huang, R. Ravi, A. Bedi, W. S. Dalton, R. Jove, and H. Yu. 2001. Overexpression of a dominant-negative signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 variant in tumor cells leads to production of soluble factors that induce apoptosis and cell cycle arrest. Cancer Res. 61:3276-3280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Niu, G., K. L. Wright, M. Huang, L. Song, E. Haura, J. Turkson, S. Zhang, T. Wang, D. Sinibaldi, D. Coppola, R. Heller, L. M. Ellis, J. Karras, J. Bromberg, D. Pardoll, R. Jove, and H. Yu. 2002. Constitutive Stat3 activity up-regulates VEGF expression and tumor angiogenesis. Oncogene 21:2000-2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pharoah, P. D., N. E. Day, and C. Caldas. 1999. Somatic mutations in the p53 gene and prognosis in breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Br. J. Cancer 80:1968-1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pipas, J. M., and A. J. Levine. 2001. Role of T antigen interactions with p53 in tumorigenesis. Semin. Cancer Biol. 11:23-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prives, C., and P. A. Hall. 1999. The p53 Pathway. J. Pathol. 187:112-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raman, V., A. Martensen, D. Reisman, E. Evron, W. F. Odenwald, E. Jaffee, J. Marks, and S. Sukumar. 2000. Compromised HOXA5 function can limit p53 expression in human breast tumours. Nature 405:974-978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roy, B., and D. Reisman. 1996. Positive and negative regulatory elements in the murine p53 promoter. Oncogene 13:2359-2366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scheffner, M., B. A. Werness, J. M. Huibregtse, A. J. Levine, and P. M. Howley. 1990. The E6 oncoprotein encoded by human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 promotes the degradation of p53. Cell 63:1129-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seidel, H. M., L. H. Milocco, P. Lamb, J. E. Darnell, Jr., R. B. Stein, and J. Rosen. 1995. Spacing of palindromic half sites as a determinant of selective STAT (signal transducers and activators of transcription) DNA binding and transcriptional activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:3041-3045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shaulian, E., A. Zauberman, D. Ginsberg, and M. Oren. 1992. Identification of a minimal transforming domain of p53: negative dominance through abrogation of sequence-specific DNA binding. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12:5581-5592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stark, G. R., I. M. Kerr, B. R. Williams, R. H. Silverman, and R. D. Schreiber. 1998. How cells respond to interferons. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67:227-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Turkson, J., T. Bowman, R. Garcia, E. Caldenhoven, R. P. de Groot, and R. Jove. 1998. Stat3 activation by Src induces specific gene regulation and is required for cell transformation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:2545-2552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Turkson, J., D. Ryan, J. S. Kim, Y. Zhang, Z. Chen, E. Haura, A. Laudano, S. Sebti, A. D. Hamilton, and R. Jove. 2001. Phosphotyrosyl peptides block Stat3-mediated DNA-binding activity, gene regulation and cell transformation. J. Biol. Chem. 276:45443-45455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vogelstein, B., D. Lane, and A. J. Levine. 2000. Surfing the p53 network. Nature 408:307-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wagner, B. J., T. E. Hayes, C. J. Hoban, and B. H. Cochran. 1990. The SIF binding element confers sis/PDGF inducibility onto the c-fos promoter. EMBO J. 9:4477-4484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang, T., G. Niu, M. Kortylewski, L. Burdelya, K. Shain, S. Zhang, R. Bhattacharya, D. Gabrilovich, R. Heller, D. Coppola, W. Dalton, R. Jove, D. Pardoll, and H. Yu. 2004. Regulation of the innate and adaptive immune responses by Stat-3 signaling in tumor cells. Nat. Med. 10:48-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xie, T.-X., D. Wei, M. Liu, A. C. Gao, F. Ali-Osman, R. Sawaya, and S. Huang. 2004. Stat3 activation regulates the expression of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and tumor invasion and metastasis. Oncogene 23:3550-3560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu, X., Y. L. Sun, and T. Hoey. 1996. Cooperative DNA binding and sequence-selective recognition conferred by the STAT amino-terminal domain. Science 273:794-797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu, C. L., D. J. Meyer, G. S. Campbell, A. C. Larner, C. Carter-Su, J. Schwartz, and R. Jove. 1995. Enhanced DNA-binding activity of a Stat3-related protein in cells transformed by the Src oncoprotein. Science 269:81-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yu, H., and R. Jove. 2004. The STATs of cancer - new molecular targets come of age. Nat. Rev. Cancer 4:97-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang, Y. W., L. M. Wang, R. Jove, and G. F. Vande Woude. 2002. Requirement of Stat3 signaling for HGF/SF-Met mediated tumorigenesis. Oncogene 21:217-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.